Abstract

The study describes a pedagogic adaptation of the matched guise technique with the aim to raise linguistic self-awareness of L2 accentedness stereotyping effects among Swedish pre-service teachers. In the experiment, 290 students attending teacher training programs were exposed to one of two matched guises, representing either L1 accented Swedish, or L2 accented Swedish. Both guises were based on the same recording, but the L2 accented version had been digitally manipulated using cut-and-paste techniques in order to replicate certain vowel sounds (the [u:]-sound in particular) associated with low-prestige Swedish L2 accentedness. The findings from this experiment were then used as starting point for language awareness raising activities. Our overall results show that the L2 accented manipulated recording was evaluated more favourably than the original L1 accented recording on all investigated variables. One proposed explanation is that respondents were inadvertently influenced by so-called shifting standards effects, i.e. lower standards/expectations are being used as reference points when evaluating the L2 accented recording. This tendency, however, seemed to be less apparent among respondents with bi/multilingual linguistic identities. Following debriefing discussions based on the experiment findings, there were clear indications that respondents did become more aware of inadvertent linguistic stereotyping by participating in the activities.

Introduction

The Swedish Education Act and governing documents, such as curricula, state that education in Swedish schools should be ‘equivalent’,Footnote1 and that all students should have the right to a high-quality education (Education Act, Citation2010, chapter 1, section 9). National goals specify the norms for this equivalence: an equivalent education refers to one where students’ opportunities to succeed should not in any systematic way depend on their gender, their background, where they live or which school they attend. Another central aspect of the Swedish schools’ equivalence task is that education must be adapted to students’ prerequisites and needs. More specifically, this means that teaching should promote learning “based on pupils’ backgrounds, earlier experience, language and knowledge” (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, p. 6).

The realisation of an equivalent education is also closely linked to teachers’ expectations of students’ abilities and achievements, and these expectations are in turn a central factor for students’ school success (Hattie, Citation2009). Such expectations most likely influence qualitative and quantitative aspects of teaching and support efforts, and to what extent teachers feel they can challenge students to develop in their learning (cf. Watson et al., Citation2019). Low expectations can lead to a maintenance, or even an increase, of existing inequalities between different groups, as less advantaged pupils are less likely to have external expectational structures that support academic success than pupils from more privileged backgrounds (cf. Turner et al., Citation2015). Too high expectations, on the other hand, can also be problematic when individual prerequisites are not taken into account.

Just as for the population at large, teachers’ different expectations are often influenced by conscious or unconscious stereotypes. Stereotypes, here defined as traits, characteristics and/or behaviours attributed to a person on the virtue of shared and overgeneralized beliefs regarding the social groups she/he belongs to (cf. Locksley et al., Citation1982, p. 270; Puddifoot, Citation2019, p. 71), typically include groupings such as gender, social class and/or ethnicity (cf. Gillborn et al., Citation2012). Here language can act as an important trigger for stereotyping (see Talbot, Citation2003, p. 468), and our way of speaking is oftentimes an important cue for how we are perceived and judged. Boyd (Citation2003), for example, shows that L2 accentedness can lead not only to unmotivated negative judgements of general language abilities, but also to negative judgements of trait characteristics, such as professional competence in comparison to how speakers with L1 standard accentedness are judged. Translated to an educational context, findings such as these highlight the harsh reality of the importance of pronunciation for societal inclusion (cf. Thorén, Citation2008).

Such findings also show how stereotyping can skew our perceptions. We argue that awareness of such effects is particularly important for teachers who have to foster strategies for how to listen objectively, and how to distinguish what they actually hear from what they think they think hear (cf. Bijvoet, Citation2019). Such awareness is decisive in determining how to approach pupils in everyday communication in general, and for assessments of students’ achievements in particular. Developing and evaluating methods for raising such language awareness is the topic of this study.

The current study is part of the project A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Raising of Awareness through Virtual Experiencing (Deutschmann & Steinvall, Citation2020), with the aim to develop methods for raising awareness of linguistic stereotyping (LS). The project also seeks to highlight culturally contextualised aspects of such phenomena. This study focuses on an experiment conducted with Swedish pre-service teachers about stereotypes and attitudes linked to L2/migration-related linguistic variation, and how this in turn may affect expectations and perception of speakers’ overall language performance. More specifically, we investigate whether and how minimal variation in linguistic output, such as the pronunciation of a single phoneme, can trigger “wider social connotations” (cf. Stæhr & Madsen, Citation2015, p. 70). While the results generated by the empirical data from this experiment are of interest, we also want to describe and discuss how the experimental design was used as a method for raising pre-service teachers’ language awareness of issues related to linguistic stereotyping (LS).

Teachers’ potential as agents of social change puts pre-service coursework aiming at raising teachers’ language awareness at the very centre of Language Awareness as a field (cf. Gage, Citation2020). In the literature, a variety of pedagogical/methodological alternatives that approach the question of linguistic tolerance have been put forth and researched, such as interactive collaboration-exercises aiming at developing reflexive and inclusive interactional practices (Gage, Citation2020); experience-based workshops held in a language in which the participants have limited knowledge of (Ruiz Fajardo & Torres-Guzmán, Citation2016); and training programmes aiming at changing language ideologies of teachers through knowledge of multilingualism and translanguaging methodologies (Putjata, Citation2018). However, the pedagogical potential of adaptations of the matched-guise technique (MGT), the method that has inspired this study, as a means of raising pre-service teachers’ awareness of language stereotyping effects is – to our knowledge – yet to be explored.

MGT was originally developed to investigate people’s attitudes toward social, geographical, or ethnic language varieties (Lambert et al., Citation1960). Broadly speaking, the method involves asking respondents to evaluate the personal qualities of what they think are several speakers in voice samples, but where in fact it is the same speaker who has produced the linguistic varieties under investigation. In this study, we have been inspired by the MGT design, but applied it for a slightly different purpose, namely as a pedagogical tool for language awareness raising. The strength of this design is that it is the group’s own response patterns in the MGT-inspired experiment that are the starting point for discussions aimed at raising linguistic self-awareness, something that we argue adds to the relevance of the exercise and encourages much needed self-reflections.

Literature review

In most Western contexts, the idea of the ‘standard form’ seems to carry with its language ideological positions that lead to inadvertent linguistic stereotyping (LS) favouring L1 speakers in general, and the L1 standard accented speaker in particular, while disfavouring the non-standard accented speaker in general, and the L2 accented speaker in particular (Lippi-Green, Citation2012; Monfared & Khatib, Citation2018, p. 59). In educational contexts, an area of interest for this study, numerous MGT studies have explored teachers’ and learners’ general attitudes towards L2 accented and L1 accented speakers of a target language, primarily English, but also Swedish (see Bijvoet, Citation2019; Boyd, Citation2003; Subtirelu, Citation2013). Most of these studies suggest that L1 accentedness is valued higher and is considered more ‘linguistically correct’ than L2 accentedness, and that LS effects spill over on judgements of speaker status and competence characteristics (see Subtirelu, Citation2013, p. 274, for an overview summary).

Sweden, the geographical context for this study, is no exception. In fact, Sweden has, until the last few decades, been described as a relatively homogeneous society, embracing a “majority-centred monolingualist ideology” (Wingstedt, Citation1998, p. 343), and there are several studies that highlight how L2 speakers are increasingly disfavoured. For example, Torstensson (Citation2010) was able to show how some immigrant groups (those with Arabic as L1, for example) in Sweden were at a legal disadvantage in court because interpreters most frequently speak stigmatised L2 accented Swedish, the (negative) perception and evaluation of which might have affected court outcomes. Similarly, in Boyd’s (Citation2003) MGT study, L2 speakers were ranked low for teacher suitability by both headmasters and pupils on the basis of their accentedness, although they were highly competent on other linguistic variables, and had good track records with many years of teaching experience. Boyd concludes that “judgements of accentedness and of language proficiency play an important role in the exclusion of foreigners from qualified employment” (p. 294). In a similar vein, Bijvoet (Citation2019) found that professional gatekeepers such as employment recruiters, career and study counsellor, and teachers, as well as pre-service teachers, tended to link migration-related linguistic variation to low status occupations. Despite their expressed explicit intentions to act in unprejudiced manners, these gatekeeper groups seemed to have internalised a negative discourse around multilingual suburbs according to the results of the MGT study.

There are, however, recent indications that increased globalisation and exposure to multilingual contexts are leading to greater linguistic tolerance towards divergence from the native monolingual hegemonic standard norms. From another Nordic context, this time Denmark, Jørgensen and Quist (Citation2001, p. 56) conclude that “the younger native Danish speakers are, the more they tolerate variation.” The authors attribute this to the fact that the younger generation in cities are likely to “interact with several non-native speakers every day” (p. 43). This finding is replicated in Bijvoet and Fraurud’s (Citation2016) Swedish study, which suggests that young speakers with experience of linguistic diversity embrace an “expanded” and more inclusive view of what constitutes ‘good’ Swedish (pp. 33–34).

Aims and research questions

Using a MGT-inspired design,Footnote2 the study explores the effects of slight variations in the pronunciation of a key phonological marker of ethnic identity signalling L1 accentedness vs. L2 accentedness on respondents’ impressions of a speaker (i.e. linguistic stereotyping/LS). We also explore how this subtle variation in the pronunciation of a vowel sound may spill over on the respondents’ impressions of the general language performance, so-called reverse linguistic stereotyping (RLS),Footnote3 i.e. when “attributions of a speaker’s group membership trigger distorted evaluations of that person’s speech” ( Kang & Rubin, Citation2009, p. 441; see also Hu & Su, Citation2015). Furthermore, we want to see whether, and how, experience of linguistic diversity may affect the perceptions of the L2 accented manipulation (cf. Bijvoet & Fraurud, Citation2016). The final aim is to critically evaluate the design as a method for raising language awareness. More specifically these aims can be translated into five specific research questions:

-

How does a vowel manipulation aimed at simulating L2 accentedness affect respondents’ evaluations of the general language performance of the speaker?

-

How does a vowel manipulation aimed at signalling L2 accentedness affect respondents’ evaluations of the speaker?

-

Are there any differences in the evaluation patterns between those who identify themselves as Swedish monolingual vs. bi/multilingual speakers?

-

Do the activities lead to increased self-awareness of the effects of inadvertent linguistic stereotyping?

-

If so, what aspects of this phenomenon in particular do teacher trainees feel that they have become aware of?

Method

The data that forms the basis for the current study was gathered from nine workshops with Swedish pre-service language teachers conducted between autumn 2018 and autumn 2020.

Manipulations and scriptFootnote4

Decisions concerning what aspects of the original recording were to be manipulated were based on a number of considerations aimed at maximising pedagogic intentions of the exercise. Firstly, it was important to ascertain the controlled nature of the design, i.e. that the two versions of the recording were identical (wording, voice quality, timing, intonation, prosody etc.) except for the manipulated features. Without this control, there was a risk that the credibility of the results would be questioned and that participants would point to uncontrolled background variables affecting their interpretations rather than stereotyping effects.

Secondly, we wanted to minimise the number of linguistic features manipulated in order to keep things clear and simple; the aim was to show how almost identical output can be interpreted very differently due to stereotype indexing based on very subtle linguistic differences (cf. Stæhr & Madsen, Citation2015).

Thirdly, we wanted to target manipulations to “phonological markers of ethnic identity” (Graff et al., Citation1986) that particularly signalled accentedness of non-European L1 influence from languages of Middle Eastern and North African origin, such as Arabic, Persian and, Somali, all very low status in the social hierarchy of languages in contemporary Sweden (see Josephson, Citation2018; Torstensson, Citation2010, for example). Given the above considerations of simplicity and control, we chose to start piloting manipulations of vowel sounds stereotypically associated with the target L2 accentedness. Note that this type of manipulation of isolated phonological markers has previously been shown to be enough to trigger stereotypic social perceptions related to ethnic identity (see for example Campbell-Kibler, Citation2007, Citation2008, Citation2009; Fridland et al., Citation2004; Graff et al., Citation1986; Labov et al., Citation2011).

After various practical considerations, variants of the Swedish U-phoneme were chosen. This sound is particularly challenging for many non-native speakers (see Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2018, for example) and also stereotypically indexed in popular culture (e.g. in the novel “Kalla det vad fan du vill”, Bakhtiari, Citation2005). The vowel is often reproduced more rounded and further back as an [u:]-sound by non-European immigrants with L1 influences from Arabic and Persian (see Thorén, Citation2014; Torstensson, Citation2010, for example). There were other difficult vowel sounds we could have chosen, most notably the [y:]-sound, but this is not as common (a proximate is given by letter frequencies for Swedish language, see Dahlqvist, Citation1997) and was difficult to work into the script. In the manipulated version, all [ʉ:]-sounds were changed to rounded [u:] using cut-and-paste method in Praat (cf. methods used by Labov et al., Citation2011, p. 437). Note that we deliberately worded the script for the recording so that it should contain many instances of the chosen phoneme, and all in all, 44 changes to this vowel sound were made in the 3 mins and 16 seconds long recording.

The script of the input stimulus was constructed to represent fairly typical informal teenage language: hesitant, frequent discourse markers such as you know (“du vet” in Swedish, which also is overrepresented in L2 accentedness according to Svensson, Citation2011), ain’t it (“eller hur” in Swedish), incomplete sentences, and some grammatical mistakes motivated by false starts (see Palacios Martínez Citation2015, for example).

We piloted the recording prior to the workshops with a group of 20 teacher trainees. Respondents were randomly assigned the original or the manipulated version of the recording and were asked to determine where they thought the speaker came from. Of the ten respondents who listened to the original recording, all answered that they thought the speaker came from Sweden and eight respondents also specified the geographic region (north). The other group of ten respondents who listened to the manipulated version gave answers ranging from the Middle East (2), Somalia (1), second generation immigrant (2), from the ‘suburb’ (Sw. förorten) (2), a foreigner who has lived in Sweden for a long time (2) and finally one specific reference to the pronunciation of the letter u making the respondent think the speaker was a non-native Swede who had lived there for a long time. Worth noting here is that in the Swedish context, a common implicit meaning of the term förorten (‘the suburb’) refers to segregated, marginalised and often stigmatised suburbs where immigrants and refugees and second generation immigrants are overrepresented (Tunström et al., Citation2016). The term thus has clear multiethnic connotations (see Bijvoet & Fraurud, Citation2016, p. 36).

Based on the pilot investigations, we felt reasonably confident that the unmanipulated version was perceived as ‘Swedish’ L1 while the manipulated version seemed to conjure the stereotypic L2 associations we were looking for. Finally, the sound recordings were ‘packaged’ in youtube videos with the same background silhouette images depicting an interview situation where a youth in a baseball cap and hoodie was having a conversation with a young woman. It should be noted that the function of the silhouette image was merely to further contextualise the dialogue. In order to keep the design controlled (see above), we thus chose not to include images that may have signalled different ethnicities. These videos could then easily be embedded in the response questionnaires (SurveyMonkey).

Response survey and response phase

The response survey contained nine affirmative statements related to the language production of the teenager in the recording, which respondents were then asked to agree or disagree with on a seven-point semantic differential Likert scale of the kind frequently used in language attitude studies (see Garrett, Citation2010). The labels used included ‘strongly disagree’, ‘somewhat disagree’, ‘neither disagree nor agree’, ‘somewhat agree’, and ‘strongly agree’. The statements covered several aspects of language performance specifically listed as important under the Swedish National Agency for Education’s (Skolverket) recommendations for evaluations of oral proficiency including understandability, language variability, language structure, adaptability to context, vocabulary, fluency, grammar, pronunciation and general linguistic impression.Footnote5 Specific examples of the statements include “The speaker has a rich and varied vocabulary” and “The speaker fully masters Swedish grammar”. Note that this first set of statements were primarily aimed at measuring reversed linguistic stereotyping effects, i.e. how pronunciation of the manipulated vowel sound signalling L2 accentedness affected the impressions of other aspects of the language production, which were not manipulated.

Further, the survey contained four more general statements evaluating the speaker (as opposed to the language). These were: X is verbal and linguistically gifted, X is good at presenting his opinions, X has sensible and intelligent opinions and X will do well in school. These statements were included in order to highlight aspects of the phenomenon of linguistic stereotyping, i.e. how the nature of language output may affect judgements of the speaker, a fundamental aspect of all matched-guise designs. More specifically, the choice of statements was primarily motivated by their potential to stimulate fruitful pedagogical discussions on how accentedness may influence how teachers judge individuals’ academic attributes. Also note that the choice of statements builds on experiences from previous pedagogic designs conducted under the project (see Lindvall-Östling et al., Citation2020).

The survey also contained questions geared at extracting the metadata of the respondents (age, gender, linguistic identity etc. – see ). Linguistic identity was defined as either Monolingual or Multilingual based on multiple answer choice alternatives to the question “How would you define your linguistic identity”, where respondents could choose between the answers “Swedish” or “Swedish and other”. In the question instruction it was made clear that the category ‘other’ could include any other language/s. Also, it should be noted that the survey contained a statement informing the participants that their quantitative data would be included in our research database, and that they would have the opportunity to withdraw their responses at a later date when they had been informed of the exact nature of the study.

Table 1. Respondent metadata. Note that percentages represent within-cohort values.

Because the MGT-inspired design required that participants should be unaware of the real purpose of the exercise prior to giving their responses, our participants were informed that they would listen to a reconstruction of an interview with a teenage male that was to be evaluated, and that this dialogue would later be the starting point for a discussion seminar on the subject of teenage language.Footnote6 While the exercise had clear relevance to grading and evaluation, it was not specifically contextualised as a controlled grading exercise. The participants were then given a link to the recording and the accompanying response survey. What the respondents did not know, at this stage, was the fact that the survey tool contained a ‘randomiser’ function whereby half of the respondents were directed to an unmanipulated original recording while the other half of the respondent group were directed to the manipulated version of the same recording.

Debriefing and post-survey

After the response phase, we analysed and summarised the data before gathering each respondent group for a debriefing and discussion seminar. During this seminar, we explained the true purpose of the activity they had just participated in and revealed the design of the exercise. After this this we played up the full length recording of the two versions, and presented the specific results for each group, showing differences in response patterns between those who had listened to the original unmanipulated version, and those who had listened to the manipulated version. Armed with this information, the group was then split into smaller focus groups, where they discussed the results and reflected on the general and specific relevance of what they had learnt to their future professional practice. Finally, the classes were reassembled and each group was given an opportunity to present a summary of their discussions and reflections. After the debriefing seminar, we distributed a post-survey, which included a quantitative self-estimation of stereotyping awareness as well as questions related to the qualitative experiences of the exercise.

In order to evaluate research question 4, i.e. whether the activities lead to increased self-awareness of the effects of inadvertent LS or not, we included the following question in the initial part of the response survey (i.e. before the respondents had partaken in the activities) and in the post-survey (i.e. after the debriefing):

“To what extent do you think that you are influenced by stereotypical preconceptions (conscious or unconscious) in your expectations and judgements of others?” (0-100 scale, where 0 = not at all, and 100 = very much so)

Qualitative data related to research question 5, i.e. what aspects of stereotyping awareness had been raised, was also primarily gathered from the post-survey, but also during the classroom discussions of the debriefing seminars. Most aspects discussed in the seminars were touched upon in the open-ended response questions of the post-survey. We asked respondents to reflect on how the experiment and subsequent discussions had raised awareness on issues related to:

-

General aspects of stereotyping and how it affects us

-

Specific aspects of stereotyping related to professional practice

-

Preventive measures of stereotyping

Finally, we also invited participants to comment on design issues and to give consent (or not) that their responses be included in the research database. In total, 136 informants responded to this open-ended part of the post survey.

Participants

All in all, 290 respondents from nine different classes of Swedish taught under primary and secondary teacher training programs partook in the activities. A total of 148 respondents listened to the manipulated version and 142 respondents listened to the original version. The demographics of these respondent groups are summarised in below.

Data analysis

Research questions 1–3 were analyzed using a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) model. The responses were simultaneously analyzed using MANOVA with factors ‘Manipulations’ (manipulated, original), ‘Gender’ (male, female), ‘Linguistic Identity’ (Monolingual/Multilingual), ‘Program Group’ (Primary/Subject teachers), and interactions Manipulation*Gender, Manipulation*Linguistic Identity, and Manipulation*Program Group. Wilks’ lambda was used to evaluate overall statistical significance for factors and interactions. Subsequent ANOVAs were then evaluated. Residual analyses were carried out to check model assumptions. Individual factor level effects were analyzed by estimating marginal means. Four individuals with gender ‘other’ were deemed as too small a grouping to motivate their own category and removed from the quantitative analysis. Their responses were however included in the qualitative analysis.

Research question 4 was analyzed by using a paired t-test for responses before and after the session. We have made interval data level approximations of the measured scales. We used partial Eta Square to measure effect size. All t-tests were two-sided and a significance level of 5% was used. The data was statistically evaluated in SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The response rates for these parts of the surveys were relatively low. Although all respondents included in the dataset completed the post-survey, many of our participants skipped this question in the pre-survey and/or the post-survey, which prevented pre- and post-experiment matching. This data set thus constitutes 145 complete matchable pre-survey and post-survey responses. We assume that the missing observations are Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) since there is no reason to suspect otherwise.

Regarding research question 5, respondents’ written responses to open-ended questions in the post-survey were analyzed using a stepwise, thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Through a full individual reading and re-reading of all responses, a tentative set of themes were identified by two separate researchers in our team. These were then compared and analysed and new theme categories were constructed. In the next stage, the resultant themes were reviewed by assembling all relevant data to each theme, and by re-checking the accuracy and relevancy of each theme. After refining the themes, a final categorization of the whole data set was conducted, which was used to summarize and describe the respondents’’ answers. Finally, we selected examples which gave representative illustrations of the views of the respondents that were revealed in the data. Selected responses were translated to English, with slight changes made to adjust language correctness, but with care not to change the content and nuances conveyed.

Results

Research question 1: How does a vowel manipulation aimed at simulating L2 accentedness affect respondents’ evaluations of the general language performance of the speaker?

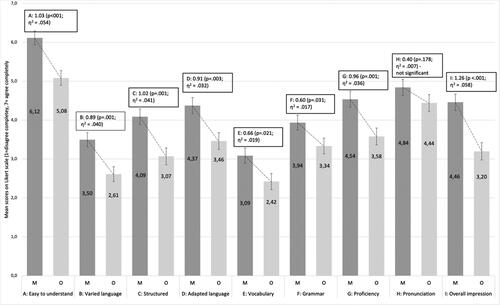

Overall, the respondents evaluated the manipulated L2 accented version significantly more favourably on all but one of the linguistic variables – ‘Pronunciation’, which was the only variable that was not evaluated significantly differently in the two treatments (see below). Other observations from statistical analyses were that the variable gender did not have any significant effect on the response variables. The variable ‘Program Group’ did have an effect on the outcomes – pre-service upper secondary teachers overall produced lower evaluations of both the original and manipulated versions of the recording than did the pre-service primary teachers. However, there were no significant interactions, and the manipulated L2 accented version was evaluated more favourably than the original L1 accented version in both groups.

Figure 1. Differences in evaluation of linguistic variables: manipulated L2 (M) vs original L1 recording (O). The dotted lines mark out the difference in Likert points between M and O. The information in the boxes represents: 1. difference M-O in Likert points; 2. p-values, where >0.05 is deemed as significant; and 3. the partial eta squared effect size value (η2), where the suggested norms for partial eta-squared are small = 0.01; medium = 0.06; large = 0.14. N = 290. Also note that the data above represents differences in factor levels analyzed by estimating marginal means.

Research question 2: How does a vowel manipulation aimed at signalling L2 accentedness affect respondents’ evaluations of the speaker?

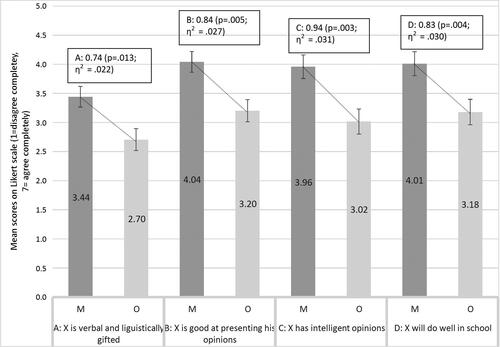

The L2 accented manipulation was evaluated significantly more positively on all of the investigated traits (see ). The greatest difference between the two evaluations was seen for the variable “X has intelligent opinions”. The variables Gender and ‘Program Group’ did not have any significant effect on the response variables.

Figure 2. Differences in evaluation of speaker traits: manipulated (M) vs original recording (O). The dotted lines mark out the difference in Likert points between M and O. The information in the boxes represents 1. difference M-O in Likert points; 2. p-values, where >0.05 is deemed as significant; and 3. the partial eta squared effect size value (η2), where the suggested norms for partial eta-squared are small = 0.01; medium = 0.06; large = 0.14. N = 290. Also note that the data above represents differences in factor levels analyzed by estimating marginal means.

Research question 3: Are there any differences in the evaluation patterns between those who identify themselves as swedish monolingual vs. bi/multilingual speakers?

summarises the response patterns of those who identified themselves as having primarily monolingual Swedish identities and those that identified themselves as bi/multilingual identities. Mean differences in responses are calculated by subtracting mean Likert scale ratings in response to the original version (L1 accented) from the mean Likert scale ratings given in response to the manipulated version (L2 accented). A positive figure thus indicates that the manipulated (L2 accented) version was evaluated more favourably than the original (L1 accented) version.

Table 2. Differences in evaluations of the manipulated L2 accented version (M) and the original L1 accented version (O) of Multilingual vs. Monolingual sub-groups. Numbers in brackets represent p-values, where >0.05 is deemed as significant; and the partial eta squared effect size value (η2), where the suggested norms for partial eta-squared are small = 0.01; medium = 0.06; large = 0.14.

For both groups (Mono- and Multilingual), the general trend was that the manipulated L2 accented version was evaluated more favourably. This difference was however greater for the monolingual Swedish respondent group, where differences on the whole were highly significant except for the variable ‘Pronunciation’. The greatest observed differences between the original and manipulated versions in this group were for the variables ‘Overall impression’ (1.45 Likert points), ‘Adapted language’ (1.38 Likert points) and ‘Structured language’ (1.35 Likert points). In the personal traits category, the greatest difference between the manipulated and original version was for the variable ‘Intelligent opinions’ (1.34 Likert points).

The response patterns in the Multilingual group were somewhat different. On the whole, and just as in the Monolingual group, the manipulated L2 accented version was evaluated more favourably than the L1 accented version. However, the differences between these evaluations were much smaller, and were only significant in two cases: for the variables ‘Easy to understand’ and ‘Overall impression’. While the lack of significant differences can partly be attributed to the smaller sample size (54 vs. 236), it is noteworthy that differences also were much smaller and only exceeded one Likert point for one variable (Overall impression). This is also reflected in the effect sizes which were generally very small for the Multilingual group, but small-medium for the Monolingual group. In the Monolingual group the differences exceeded one Likert point in ten of the thirteen variables (see ). It should be noted, however, that we only found significant interaction effects for the variable ‘Vocabulary’ in the ANOVA analysis.

In summary, our results suggest that respondents with multilingual backgrounds judged the two versions more equally than did the monolingual Swedish group, who almost invariably gave the manipulated L2 accented version significantly higher scores than the L1 accented version.

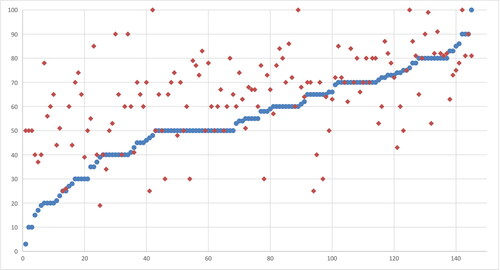

Research question 4: Do the activities lead to increased self-awareness of the effects of inadvertent linguistic stereotyping?

In order to answer this question we asked the question below before and after the exercise:

“To what extent do you think that you are influenced by stereotypical preconceptions (conscious or unconscious) in your expectations and judgements of others?” (0-100 scale, where 0 = not at all, and 100 = very much so).

Figure 3. Response distributions of pre-survey values (blue round dots) with matching post-survey values (red square dots) for the 145 respondents. Note that the mean score for the pre-treatment evaluations is 55.01 (standard deviation 19.32) and 64.5 (standard deviation 17.6) for the post-treatment evaluations.

Research question 5: What aspects of linguistic stereotyping in particular do teacher trainees feel they have become aware of?

In the respondents’ qualitative written responses, three different aspects of language awareness and inadvertent LS are particularly salient: a) (inter)personal implications, b) professional implications, and c) the relation between linguistic features and stereotypes.

The first aspect – (inter)personal implications – is the most striking one in the respondents’ responses. It relates to the respondents’ personal experience of taking part in the experiment. An important insight seems to be that of being a “part of the problem.” Not only have stereotypes in general been “made visible” and “tangible”; pronouns such as I/me/mine and we/our are frequent, stressing a troubling ownership of the prejudices and biases revealed. Some respondents describe nearly enlightening, or even revelatory experiences, which can be exemplified by the following excerpts:

“This has helped me realize the extent to which we’re affected by our expectations and our prejudices”

“It has helped me understand that we all carry our prejudices, regardless if we are aware of them or not.”

As in the excerpts above, respondents frequently make reference to the experiment (“This”, “It”) as a point of departure for their own reflection. In their responses, respondents also stress the perennial nature of stereotyping. Stereotyping is not easily overcome by means of some quick fix. This becomes clear in expressions stating the importance of “trying to overlook your prejudices”, and to “continuously be aware of” and to “always work with oneself”, but that it is “probably difficult” to completely eliminate stereotypes.

The second aspect of awareness in the respondents’ responses – professional implications – primarily regards consequences of stereotyping for equality in education as illustrated below:

“I believe that [stereotypes] might affect me in the sense that my expectations differ, regarding levels of knowledge and abilities.”

“I guess every human carries one’s prejudices of others, but they usually fade if one takes the time to get to know one another a little better.”

“It was valuable to see the tendencies [shown by the experiment]. Do I assess the student’s actual performance or based on preconceptions about the student?”

“Anonymous assessments may reduce prejudiced thoughts, but how one writes can in itself create prejudiced thoughts and expectations”.

The third aspect – the relation between linguistic features and stereotypes – includes answers that explicitly relate invoked stereotypes to the linguistic features functioning as triggers in the experiment. Overall, answers of this kind show how the experiment has made the participants aware of how specific linguistic features can influence judgements of different aspects of the speakers’ proficiency. This awareness is typically expressed in general terms, through formulations such as the following:

“An eye opener that one focuses on HOW people talk and not WHAT they say”.

“Try to overlook the pronunciation”

“Good to see the tendencies to assess students differently depending on whether or not they speak with a specific accent”.

A few answers are more elaborated by linking back to previously mentioned aspects (i.e. consequences for assessment). This can be illustrated by the following example:

“Makes you aware of how you unconsciously assess and categorize students based on mere pronunciation. This can in turn can lead to teachers making more fair assessments.”

“I think it [the experiment] was interesting, but I found some questions inappropriate and I felt uncomfortable to answer. It felt very judgmental.”

“It is completely illogical to answer questions about academic performance based on pronunciation, but I was forced.”

These are, of course, both legitimate and important objections. The experiment, by design, pushes the participants to make inferences (i.e. predictions about a person’s future) that by far exceeds what the data (a short interview) holds for. In this sense, the setup itself evokes stereotypes and biased judgements, and this general critique of MGT has been raised by several researchers (see for example Bradac et al., Citation2001; Laur, Citation1994; Ryan et al.,Citation1988). One student suggests a possibility to opt out on certain questions:

“A third alternative, where one could refrain or give an explanation, would add nuance to the study, instead of reproducing ideas about foreigners as less smart”.

“I liked how we didn’t have any information in advance. If we had known you wouldn’t have got so honest results.”

“It was interesting how blinded we were towards the purpose of the experiment. That probably made the result more plausible and truthful.”

To sum up, the informants were generally positive towards the experiment and the debriefing sessions. They describe it as an aha-moment and a valuable learning experience, both in general terms and in more professional terms. It is important to note, however, that despite their positive attitudes towards the methodology, no student expresses a view of the experiment or the methodology as a real solution to the problem. Rather they see it as a kind of awakening, whilst the real hard work of professionally harnessing one’s biases lies ahead.

Discussion

Research questions 1 and 2

With reference to research questions 1 and 2, it was evident that all of our respondent groups evaluated the manipulated L2 accented simulation more favourably than the L1 accented version. Our results thus suggest that the L2 accented simulation led to positive RLS effects, resulting in more positive overall language evaluations, but also positive LS effects leading to more favourable evaluations of the person speaking in the L2 accented simulation.

These results are interesting and – at least at first glance – very surprising, given the results from previous studies, such as Bijvoet (Citation2019), Boyd (Citation2003) and Torstensson (Citation2010), which all suggest that L2 accented Swedish leads to negative RLS and LS. However, it is important to note how the contextualization of the assessment situation in our study differs from the aforementioned studies. The participants in Boyd (Citation2003) were asked to judge foreign born-teachers’ suitability for teaching in Swedish schools. Similarly, the participants in Bijvoet’s (Citation2019) study were also asked to assess work life-related qualities. In our study, on the other hand, the participants were teacher trainees, who were told that the voice in the recording was from an interview with a student in junior high school. In our experiment, the respondents thus had a markedly different social position in relation to the one being assessed, and accordingly power relations were different. This aspect was also a frequent topic of discussion in the debriefing sessions, i.e. the responsibilities that came with being a teacher and the potential power that one had over learners’ futures. Arguably, this aspect may have contributed to overcompensation effects resulting from anxiety in assessing a potentially vulnerable and relatively powerless group unfairly.

The seminar discussions and the qualitative answers we received lead us to believe that respondents inadvertently were influenced by so-called shifting standards effects (Biernat, Citation2012). Shifting standards is a well-documented phenomenon whereby members of negatively stereotyped groups may be described relatively favourably because lower standards/expectations are being used as reference points. Applying this effect to the present context, the results would suggest that many of our respondents may have evaluated the L2 accented version against prototypes of L2 speakers, rather than making an objective absolute evaluation of the language competence and the traits we asked about. Put more simply, respondents may have been “impressed” by the fact that there were only minimal deviations from standard norm pronunciation (one vowel only) and this may have led to overly positive evaluations of other aspects of the output.

These are, we argue, important experiences to make and issues to discuss in low stakes environments during teacher education. The exercise was on the one hand realistic and relevant enough to engage the participants, raising difficult questions related to their future roles as teachers (e.g. implications of bias in grading, double standards in formative assessment). On the other hand, the experimental situation was distanced enough from the real teacher role, which we believe facilitated an open minded and explorative tone.

Another potential explanation for the observed differences in evaluation patterns between the L2 and L1 versions is that the more positive ratings of the L2 accented manipulation reflects the participants’ understanding of, and wishes to comply with, the concept of ‘equivalence’ within educational discourse. Equivalence is closely linked to differentiation, which refers to the management of education and teaching in ways that meet individual backgrounds, prerequisites and needs (Education Act, Citation2010; Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011). In other words, the results may reflect the teacher trainees’ attempts to live up to an educational and pedagogical ideal. Adapting answers to so-called ‘expectancy factors’ – where respondents self-report in a manner that mirrors societal values rather than what they actually feel – has been shown to be a problematic source of error in self reports in trait studies (see Feingold, Citation1994). This type of social desirability bias has been widely reported in surveys that deal with potentially sensitive matters (Krumpal, Citation2013).

Research question 3

Results from research question 3 showed that respondents with multilingual linguistic identities did not differ significantly in their responses to the L1-accented and L2-accented versions on the whole. Although rather inconclusive, due to the relatively small number of respondents in this group, our results partly corroborate Boyd’s study (2003), where it was noted that “[t]he classes which were clearly dominated by monolingual Swedish students were those who were most accepting of teachers who spoke Swedish with a foreign accent” (p.293). The same study also observed that it was non-native speakers of Swedish who emphasised the importance of teachers’ Swedish language skills the most. An important difference with Boyd’s findings, however, is that in our study, the respondents of multilingual linguistic identity did not actually judge the L2-accented version harsher; instead they made no difference between the L1 and L2 versions. This tendency, i.e. that the L2-simulated vowel manipulation did not seem to spill over to influence the judgement of other linguistic variables and traits, may be an effect of increased linguistic tolerance. This would support Bijvoet and Fraurud’s (Citation2016) claim that young speakers with experience of linguistic diversity embrace an “expanded” view of what acceptable Swedish is (pp. 33–34). Further studies with much larger datasets are, however, needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Research questions 4 and 5

With reference to research questions 4 and 5, the results from the pre- and post-surveys suggest that the respondents did become more aware of inadvertent linguistic stereotyping by participating in the project. As to the quantitative data, respondents on average reported a significantly increased awareness that they were affected by stereotyping after having participated in the project. As to the qualitative data, the most important finding is that the participants by no means view this topic as played out by the activity. Rather, they see it as a new beginning of an ongoing and long process.

Regarding this process, the different aspects of awareness identified in the participants’ written responses may, at least hypothetically, be interpreted as suggesting a progression, from basic towards a more comprehensive and manifested reasoning on linguistic stereotyping as a phenomenon. The immediate reactions tended to involve the realization of being part of (re)creating stereotypes, sometimes accompanied by affective reactions towards this realization. A second layer seemed to include reflections on how this can have consequences for one’s own actions in the professional role as a teacher (i.e. double standards). A somewhat more comprehensive reasoning occurred when respondents explicitly described the processes leading up to the double standards, that is how certain linguistic traits (in this case [ʉ:]vs[u:]) may trigger stereotypes (i.e. “immigrant student”), and how this risks influencing one’s judgements of other aspects of the speakers’ proficiency. The most comprehensive awareness expressed by participants in our data involved the problematizing of the experimental setup. These respondents may be said to display a meta-awareness of how context interplays in stereotyping processes.

The above strengthens our conclusion that this kind of exercise is both feasible and rewarding as an introduction to courses in, for example, sociolinguistics, educational linguistics, etc. It could, for example, be argued that many of the participants’ call for anonymous assessments actually illustrates an oversimplified view of potential solutions to a very complex problem, and thereby a need for further instructional activities and discussions surrounding issues related to objective assessment. In the general discourse on equity in assessment, anonymity is a recurring solution, but in this case it is safe to say that it would not have made a difference. After all, the recordings in the experiment were completely anonymous already. It was not the identity of the student, i.e. the name, ethnic background, place of domicile etc. (none of which were disclosed), but rather the linguistic features inherent in the performance per se that triggered any stereotyping effects.

Limitations and conclusion

One aim in this study has been to increase awareness of the prevalence of linguistic stereotyping, as part of their professional development. While the current design seems to have been successful in raising awareness and in initiating discussions about stereotyping, we are also able to identify several flaws. Firstly, as pointed out by others (Bradac et al., Citation2001; Laur, Citation1994), the juxtaposed binary nature of matched-guise inspired set-ups creates a very artificial situation. Paradoxically, the binary design of the experiment can thus contribute to maintaining and reproducing already existing stereotypes, something which obviously undermines desired effects. Moreover, we cannot overemphasize the fact that our findings are based on an artificial scenario (cf. the general critique of MGT raised by Ryan et al., Citation1988), and are in no way a reflection of real structural differences in evaluation patterns in Swedish schools. In a real evaluation situation, teachers would base their judgements on several aspects, and would have tools available to help them in objective evaluation. Again it is also worth noting that our accented simulation only differed in one vowel sound, which of course does not reflect the complexity of real L2 accented speech. Further, teachers in the field would most likely discuss and compare their grading with colleagues to prevent unwanted bias. The results from this study must therefore not be seen as evidence that non-native pupils get “better-than-deserved grades”. However, we are well aware of the risks that such interpretations may be made to suit xenophobic political interests. Similar concerns, as we have seen, were also raised by a few of the participants in their responses to the post-survey.

Another general limitation with MGT-like designs, also pointed out by Laur (Citation1994), is that asking respondents to take a stance on predetermined aspects decided by the researchers may force points of focus and interpretations that bear limited relevance to real life situations. In this way, we may be uncovering false language triggers and stereotype effects, or falsely assign a disproportionate importance to relatively unimportant factors. In our experiment, for example, an obvious shortcoming was that the only manipulation to the original recording was that of one vowel, and it is questionable if we can make generalizations about the effect of accentedness in general based on this stimulus. This was actually noted by one student, who pointed to the weakness that the activities described risk being party in strengthening, rather than dismantling existing stereotypes, or even creating new stereotypes.

Arguably, it would have been more true to life to have the same script read by an L1 speaker and then read by an L2 speaker, including segmental, suprasegmental and other linguistic elements (e.g. grammar, pragmatics). In this way one would represent the target L2 group’s speech more fully, and responses may have been of greater relevance to real life situations. However, this would also have meant compromising the controlled nature of the design, thereby risking the pedagogic impact of the exercise.

In our debriefings, but also in this context (i.e. academic publications), it is further important to emphasise that the presented results in tables and figures are averages compiled from a range of data. Although variance and 95% confidence may be included in the data, it is still easy to forget that a difference of one point on a Likert scale between two data sets, for example, still often implies a great deal of overlap. Consequently, we are looking at differential tendencies, rather than differences per se, since a number of respondents in the group that listened to the manipulated version in fact responded no differently than those who listened to the original version. Of course we try to highlight this issue in the debriefing seminars by explaining the complexity of the data presented, but the question is if the lasting impression still is not one of difference rather than similarity. Thus, we may inadvertently contribute to creating stereotypes about stereotypical behaviour. It is also important to note that not all observed differential tendencies necessarily are a result of stereotyping. As Cargile (Citation2002, p. 179) points out, listener evaluations are likely to be the product of individually-specific knowledge, the listeners’ motivation/capacity to engage in information processing, as well as several evoked language attitudes.

In summary, we can conclude that in spite of the shortcomings discussed above, the method described in this article is very promising and does indeed lead to increased self-awareness of the effects of inadvertent linguistic stereotyping. The ambition of our method, i.e. raising awareness of how stereotyping inadvertently affects us all, is however only a first step and one part in the pursuit of combatting discriminatory behaviours. Looking forward, we see the need to further explore some of the tendencies seen in this study using larger data sets. It would indeed be interesting to further explore whether/how exposure to language variation leads to greater linguistic tolerance and the effects that this may have on reverse/linguistic stereotyping. Moreover, it would be fruitful to develop more comprehensive and carefully controlled MGT-inspired designs aimed at reproducing realistic grading and assessment scenarios. Given the important role teachers have in shaping children and young adults, we argue that questions of equivalence and equity in relation to stereotyping should be central in all teacher training, and here we hope our method can contribute. We do, however, recognise the fact that a single session of the type described in this paper is not enough. We rather see it as one of several targeted workshops or talks throughout the teacher program that will help in maintaining a high level of awareness.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (60.6 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mats Deutschmann

Mats Deutschmann PhD is professor of English at the School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro University, Sweden. He has a diverse multidisciplinary research focus which includes sociolinguistics, the status of minority languages in post-colonial educational contexts, language didactics and learning designs with special focus on e-learning and digital humanities. He has just finalised two projects on language and stereotyping funded by the Swedish Research Council and Wallenberg Foundation. Both projects approached the challenge of finding ways to increase sociolinguistic awareness of issues related to language and stereotyping.

Eric Borgström

Eric Borgström PhD is senior lecturer in Swedish language at the School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro University. His main research interests are in the field of writing - the teaching and assessment of writing, as well as policy issues related to writing. Questions include what ideas about writing are expressed in different policy documents, and what notions of writing and writing development motivate different teaching and assessment practices. How students are positioned and position themselves in relation to these practices is also of interest. As a writing researcher, Eric is interested in the entire education system - from preschool class to university.

Daroon Yassin Falk

Daroon Yassin Falk PhD is senior lecturer in Swedish language at the School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro university. Her main research interests concern writing and writing development in educational contexts. In recent years her research focus has been on writing development and writing instruction in primary school and language ideologies in lower secondary Swedish teachers’ instructional practice.

Anders Steinvall

Anders Steinvall, PhD, is Senior Lecturer in English Linguistics at the Department of Language Studies, Umeå University, Sweden. An experienced teacher of English language courses and Linguistics courses in teacher education, he has worked with computer-assisted language learning (CALL) tools for more than 20 years in Higher Education. Steinvall uses ICT as a support tool for students, but also as tool for stimulating discussions and debriefings whose goals are that students reach new heights of learning. His teaching experiences include language and gender, and language and stereotypes. He is an active researcher in the Swedish Research Council project RAVE – Raising Awareness through Virtual Experiencing.

Johan Svensson

Johan Svensson has a PhD in mathematical statistics from Chalmers University of Technology (CTH). His thesis was focused towards the field of survival analyses and reliability theory. After his Ph.D. Johan moved to Umeå where he works as a lecturer in the department of statistics. In Umeå, Johan’s research interest changed to biostatistics, mainly because of the close vicinity to the hospital. Johan likes to apply statistics to solve a wide range of problems that occur in both social and medical sciences. Johan has strong interest for teaching and is working in projects related to teaching research. in cooperation with several departments.

Notes

1 Note that we use the term ‘equivalent’ rather than ‘equal’ to translate the Swedish term ‘likvärdig’. ‘Likvärdig’ does not necessarily imply equality but rather equity.

2 Note that we refer to this study as ‘MGT-inspired’. In order to maximise the pedagogic impact (see Method below), we decided to keep the design as simple as possible. We have thus not followed the typical MGT design of including a number of ‘fillers’ designed to camouflage the samples under investigation. Neither have we presented the listeners with both samples as this would uncover the covert nature of the design given the complex nature of the script (cf. Stefanowitsch, Citation2005). For a more thorough discussion of the design see Lindvall-Östling et al. (Citation2019).

3 Note that RLS is normally associated with non-linguistic attributes signalling ethnicity triggering distorted evaluations of a person’s linguistic output. Here, however, it is instead a single phonological marker of ethnicity, a shibboleth, that is used as a trigger. However, since this is all that is manipulated, we argue that potential differences in evaluations between the language performance in the original and manipulated recording other than that related to pronunciation are examples of RLS.

4 See https://www.stereotyping.se/youth-language-case.html for the recordings.

5 See evaluation templates on the ‘assessment portal’: https://bp.skolverket.se/web/bs_gy_svesve01/information and https://www.natprov.nordiska.uu.se/digitalAssets/529/c_529434-l_3-k_kp3-exempel-delprov-b-bedomning.pdf

6 The project design has been approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2016/75-31Ö).

References

- Bakhtiari, M. (2005). Kalla det vad fan du vill. Ordfront.

- Biernat, M. (2012). Stereotypes and shifting standards: Forming, communicating, and translating person impressions. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology: Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 45, pp. 1–59). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00001-9

- Bijvoet, E. (2019). Förortssvenska i grindvakters öron: Perceptioner av migrationsrelaterad språklig variation bortom inlärarspråk och förortsslang. Språk Och Stil, NF 28 (2018), 142–175. https://doi.org/10.33063/diva-376238

- Bijvoet, E., & Fraurud, K. (2016). What’s the target? A folk linguistic study of young Stockholmers’ constructions of linguistic norm and variation. Language Awareness, 25(1–2), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1122021

- Boyd, S. (2003). Foreign-born teachers in the multilingual classroom in Sweden: The role of attitudes to foreign accent. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 6(3–4), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050308667786

- Bradac, J., Castelan Cargile, A., & Hallett, J. S. (2001). Language attitudes: Retrospect, conspect and prospect. In W. P. Robinson & H. Giles (Eds.), The new handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 137–155). John Wiley and Sons.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Campbell-Kibler, K. (2007). Accent, (ING), and the social logic of listener perceptions. American Speech, 82(1), 32–64. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-2007-002

- Campbell-Kibler, K. (2008). I’ll be the judge of that: Diversity in social perceptions of (ING). Language in Society, 37(5), 637–659. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404508080974

- Campbell-Kibler, K. (2009). The nature of sociolinguistic perception. Language Variation and Change, 21(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394509000052

- Cargile, A. C. (2002). Speaker evaluation measures of language attitudes: Evidence of information-processing effects. Language Awareness, 11(3), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410208667055

- Dahlqvist, B. (1997). The distribution of characters, bi- and trigrams in the Uppsala 79 million words Swedish newspaper corpus. Uppsala University: Department of Linguistics. https://www2.lingfil.uu.se/ling/wp/wp6b.pdf

- Deutschmann, M., & Steinvall, A. (2020). Combatting linguistic stereotyping and prejudice by evoking stereotypes. Open Linguistics, 6(1), 651–671. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2020-0036

- Education Act. (2010). SFS 2010:800. Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

- Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 429–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429

- Fridland, V., Bartlett, K., & Kreuz, R. (2004). Do you hear what I hear? Experimental measurement of the perceptual salience of acoustically manipulated vowel variants by Southern speakers in Memphis, TN. Language Variation and Change, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394504161012

- Gage, O. (2020). Urgently needed: A praxis of language awareness among pre-service primary teachers. Language Awareness, 29(3–4), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1786102

- Garrett, P. (2010). Attitudes to language. Cambridge University Press.

- Gillborn, D., Rollock, N., Vincent, C., & Ball, S. J. (2012). You got a pass, so what more do you want?”: Race, class and gender intersections in the educational experiences of the Black middle class. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.638869

- Graff, D., Labov, W., & Harris, W. A. (1986). Testing listeners’ reactions to phonological markers of ethnic identity: a new method for sociolinguistic research. In D. Sankoff (Ed.), Diversity and diachrony (pp. 45–58). John Benjamins.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 metaanalyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Hu, G., & Su, J. (2015). The effect of native/non-native information on non-native listeners’ comprehension. Language Awareness, 24(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1077853

- Jørgensen, J. N., & Quist, P. (2001). Native speakers’ judgements of second language Danish. Language Awareness, 10(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410108667024

- Josephson, O. (2018). Språkpolitik. Morfem.

- Kang, O., & Rubin, D. L. (2009). Reverse linguistic stereotyping: Measuring the effect of listener expectations on speech evaluation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 28(4), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X09341950

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Labov, W., Ash, S., Ravindranath, M., Weldon, T., Baranowski, M., & Nagy, N. (2011). Properties of the sociolinguistic monitor. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15(4), 431–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2011.00504.x

- Lambert, W. E., Hodgson, R. C., Gardner, R. C., & Fillenbaum, S. (1960). Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 60(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044430

- Laur, E. (1994). À la recherche d’une notion perdue: Les attitudes linguistiques à la Québécoise. Culture, 14(2), 73–84.

- Lindvall-Östling, M., Deutschmann, M., & Steinvall, A. (2019). Oh it was a woman! Had I known I would have reacted otherwise!”: Developing digital methods to switch identity-related properties in order to reveal linguistic stereotyping. In S. Bagga-Gupta, G. Messina Dahlberg, & Y. Lindberg (Eds.), Virtual sites as learning spaces: Critical issues on languaging research in changing eduscapes (pp. 207–239). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26929-6_8

- Lindvall-Östling, M. J., Deutschmann, M., Steinvall, A., & Patel, S. (2020). “That’s not proper English!”: Using cross-cultural matched-guise experiments to raise teacher/teacher-trainees’ awareness of attitudes surrounding inner and outer circle English accents. Educare - Vetenskapliga Skrifter, 7(3), 109–141. https://doi.org/10.24834/educare.2020.3.4

- Lippi-Green, R. (2012). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Locksley, A., Hepburn, C., & Ortiz, V. (1982). On the effects of social stereotypes on judgments of individuals: A comment on Grant and Holmes’s “The integration of implicit personality theory schemas and stereotypic images. Social Psychology Quarterly, 45(4), 270–273. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033923

- Monfared, A., & Khatib, M. (2018). English or Englishes? Outer and expanding circle teachers’ awareness of and attitudes towards their own variants of English in ESL/EFL teaching contexts. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n2.4

- Palacios Martínez, I. (2015). Variation, development and pragmatic uses of innit in the language of British adults and teenagers. English Language and Linguistics, 19(3), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674314000288

- Puddifoot, K. (2019). Stereotyping patients. Journal of Social Philosophy, 50(1), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12269

- Putjata, G. (2018). Multilingualism for life – language awareness as key element in educational training: Insights from an intervention study in Germany. Language Awareness, 27(3), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2018.1492583

- Ruiz Fajardo, G., & Torres-Guzmán, M. E. (2016). Now I see how my students feel”: Expansive learning in a language awareness workshop. Language Awareness, 25(3), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2016.1179745

- Ryan, E. B., Giles, H., & Hewstone, M. (1988). The measurement of language attitudes. In U. Ammon, N. Dittmar & K. J. Mattheier (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: An international handbook of language and society (vol. II, pp. 1068–1081). Walter de Gruyter.

- Stæhr, A., & Madsen, L. M. (2015). Standard language in urban rap – Social media, linguistic practice and ethnographic context. Language & Communication, 40, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2015.01.002

- Stefanowitsch, A. (2005). Empirical methods in linguistics: the matched guise technique. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from http://socialperspectives.pbworks.com/f/exp_matchedguise.pdf.

- Subtirelu, N. (2013). What (do) learners want (?): A re-examination of the issue of learner preferences regarding the use of “native” speaker norms in English language teaching. Language Awareness, 22(3), 270–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2012.713967

- Svensson, G. (2011). Discourse particles in Swedish youth talk in multilingual settings in Malmö. In R. Källström & I. Lindberg (Eds.), Young urban Swedish: Variation and change in multilingual settings (pp. 219–235). Department of Swedish Language, University of Gothenburg. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-33253

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare. (rev. 2018). Skolverket. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/styrdokument/2018/curriculum-for-the-compulsory-school-preschool-class-and-school-age-educare-revised-2018?id=3984

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2018). Stödmaterial: Grundläggande litteracitet för vuxna med svenska som andraspråk. Skolverket. https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6bfaca41169863e6a65cfd5/1553967741481/pdf3887.pdf

- Talbot, M. (2003). Gender stereotypes. Reproduction and challenge. In J. Holmes & M. Meyerhof (Eds.), The handbook of language and gender (pp. 468–486). Blackwell.

- Thorén, B. (2014). Svensk fonetik för andraspråksundervisningen. Vulkan.

- Thorén, B. (2008). The priority of temporal aspects in L2-Swedish prosody: Studies in perception and production. [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University.

- Torstensson, N. (2010). Judging the immigrant: Accents and attitudes. [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Language Studies.

- Tunström, M., Anderson, T., & Perjo, L. (2016). Segregated cities and planning for social sustainability – a Nordic perspective. Nordregio.

- Turner, H., Rubie-Davies, C. M., & Webber, M. (2015). Teacher expectations, ethnicity and the achievement gap. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0004-1

- Watson, P. W. S. J., Rubie-Davies, C. M., Meissel, K., Peterson, E. R., Flint, A., Garrett, L., & McDonald, L. (2019). Teacher gender, and expectation of reading achievement in New Zealand elementary school students: essentially a barrier? Gender and Education, 31(8), 1000–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1410108

- Wingstedt, M. (1998). Language ideologies and minority language policies in Sweden: Historical and contemporary perspectives. [Doctoral dissertation]. Center for Research on Bilingualism.