Abstract

In this paper, we build on southern and decolonial theories of multilingualism and invite a south-north conversation through a concept we propose as ‘reciprocal multilingual awareness’. Reciprocity is a core value of southern societies that balance pluralities of episteme, language, and communality. Central features of southern multilingualisms, including transknowledging (reciprocal exchanges and translation of knowledge), and linguistic citizenship (the exercise of linguistic agency and choice), are usual moves that people make every day. Here, we lift forward southern reciprocities and linguistic citizenship together in conversation with northern conceptualisations of ‘multilingual awareness’. We draw attention to the longue durée of expertise and knowledge of multilingualism in post-colonial societies to invite conversation with critical multilingual language awareness (CMLA) as a contribution to this special issue. In this frame, we recognise the potential in ‘multilingual awareness’ for a dynamic and reciprocal process situated within specific place, time and ideology. We offer eirical experiences of multilingual reciprocities from Australia and Brazil in which community, student and teacher agency are foregrounded to illustrate and amplify southern theorisation of multilingualisms and linguistic citizenship. In conceptualising reciprocal multilingual awareness as a practice of linguistic citizenship our primary concern is to offer a contribution to teacher education that can more fully engage with organic, community and student-generated language ideologies.

RESUMO

Neste artigo, baseamo-nos nas teorias do sul e decoloniais do multilinguismo e convidamos a uma conversa sul-norte através de um conceito que chamamos de ‘consciência multilíngue recíproca’. A reciprocidade é um valor central das sociedades do sul que equilibram pluralidades de epistemologia, linguagem e comunidade. As características centrais dos multilinguismos do sul, incluindo o transconhecimento (trocas recíprocas e tradução de conhecimentos) e a cidadania linguística (o exercício da agência e da escolha linguística), são movimentos habituais que as pessoas fazem todos os dias. Aqui, promovemos as reciprocidades do sul e a cidadania linguística em conjunto, em conversa com as conceptualizações do norte global de ‘consciência multilíngue’. Chamamos a atenção para a longue durée da experiência e do conhecimento do multilinguismo nas sociedades pós-coloniais e convidamos ao diálogo com a consciência crítica de língua multilíngue (CCLM) como uma contribuição para esse dossiê. Neste quadro, reconhecemos o potencial da ‘consciência multilíngue’ para um processo dinâmico e recíproco situado num lugar, teo e ideologia específicos. Oferecemos experiências eíricas de reciprocidades multilíngues da Austrália e do Brasil, nas quais a atuação da comunidade, dos alunos e dos professores é colocada em primeiro plano, para ilustrar e aliar a teorização do sul dos multilinguismos e da cidadania linguística. Ao conceptualizar a consciência multilíngue recíproca como uma prática de cidadania linguística, a nossa principal preocupação é oferecer uma contribuição para a formação de professores que possa envolver-se mais plenamente com ideologias linguísticas orgânicas, comunitárias e geradas pelos alunos.

PLAIN LANGUAGE STATEMENT

This article shows how different communities view their own multilingual practices, including use of multiple languages for different purposes in relation to education. Our research data point to ways in which community members and students can teach educators about the variable nature and contextual functions of multilingualism. Over the last two decades, knowledge about multilingualism and how to promote awareness of multilingualism in schools has focused on North America and Europe. Here, we look at how multilingualisms in two different national settings, Australia and Brazil, are distinctive and pluridimensional. Our research indicates that teachers, teacher educators, and even linguists may need to listen more carefully to local communities and students - we use the term reciprocal multilingual awareness to describe this process.

Introduction

In the present paper we contribute to work seeking to provide greater recognition to historically marginalised or minoritised groups in multilingual education aimed at social justice (García, Citation2017; Prasad & Lory, Citation2020; Shepard-Carey & Gopalakrishnan, Citation2023). We extend the conceptual and empirical base of Critical Multilingual Language Awareness (García, Citation2017) through engagement with parallel conversations of multilingualisms in southern settings. We also offer illustrations of research that draws attention to reciprocity and linguistic citizenship. Reciprocity is a core value in southern societies that balance pluralities of episteme, language, and communality. Two central features of a decolonial and southern tributary of sociolinguistics, ‘southern multilingualisms’, are reciprocal exchanges of information and translation of knowledge, referred to by Heugh as ‘transknowledging’ Heugh, Citation2021), and the exercise of linguistic agency and choice (‘linguistic citizenship’, Stroud, Citation2001; Stroud & Heugh, Citation2004) in multiple multilingual moves that people make every day (Heugh & Stroud, Citation2019).

Conceptualisations of ‘southern multilingualisms’ (Heugh, Citation2017) and ‘linguistic citizenship’ (Stroud, Citation2001; Stroud & Heugh, Citation2004) have their genesis in critiques of colonial and postcolonial language education policies in Africa, alongside parallel south-south discourses of decolonisation and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS). These discourses were considered necessary to move beyond neo-and-post-colonial worldviews and systems that sustained the structures of coloniality in Africa (Odora Hoppers, Citation2002); Australia (Nakata, Citation2007); Brazil (Andreotti & de Souza, Citation2008); and India (Agnihotri, Citation1995; Devy et al., Citation2015). Common among these debates, and central to decolonial and southern theory, is recognition of pluriversal world views that include epistemologies, ontologies and cosmologies, and the complexities of local, regional and wider histories, geographies, languages, and socio-political contexts. It is these complexities, together with decades of fieldwork and dialogical conversations with remote, rural and urban communities and scholars, that has slowly brought forth a recognition of human agency and voice, conceptualised as ‘linguistic citizenship’ (Stroud, Citation2001), alongside multidimensionality and plurality in ‘southern multilingualisms’ (Heugh, Citation2017). Conceptualisation of linguistic citizenship has subsequently expanded in several ways, including as multilingual citizenship (Lim et al., Citation2018), and as a dialogic process in individual and community policy-making construction (Phyak et al., Citation2021). The ethos and characteristics of southern multilingualisms and linguistic citizenship are further evident in methodological and pedagogical developments (Armitage, Citation2021; Daniels et al., Citation2021; De Costa, Citation2021; French & Armitage, Citation2020; Heugh, Citation2021; Osborne, Citation2021).

In bringing together reciprocity and linguistic citizenship (see also Oostendorp, ftc), our intention is three-fold. First, it is to widen an understanding of how voicing and linguistic agency multilingually is part of a process of finding and asserting one’s linguistic citizenship. This includes multidimensional ways of deploying one’s multilinguality (sometimes for horizontal conviviality, at other times for specific vertical purposes of exclusion) (French et al., n.d.). Second, we seek to widen an understanding of the ethos of reciprocity in consensual conversation, whether this is for exchange of information, translation of knowledge, maintaining conviviality, or expressing care and hope - it is a demonstration of generosity and communality (Bock & Stroud, Citation2021; Heugh et al., Citation2021; Oostendorp, Citation2022). Third, we seek to lay out principles of reciprocal multilingual awareness (RMA) as a practice of linguistic citizenship in a format that is useful to teachers and researchers, and which extends understandings embedded in Critical Multilingual Language Awareness.

‘Southern’ approaches to multilingual awareness and linguistic citizenship

Taking linguistic citizenship as an overarching goal of multilingual language awareness, we are concerned primarily with the agency exercised by multilingual subjects. Linguistic citizenship,

signals an opportunity to listen, with respect, to what it is that people in the post-colonies have to say about the languages they use, how they use them, and their views of how best to use them for different purposes as they go about their lives and livelihoods (Heugh, Citation2022, p 35).

Hence, linguistic citizenship (also ‘multilingual citizenship’ in Lim et al., Citation2018) points to pathways for listening (Heugh & Stroud, Citation2019). If teachers assume unilateral responsibility for raising language awareness of all students, they risk overwriting or subalternising students’ already heightened multilingual awareness of the dynamics of linguistic hierarchies, inclusions and exclusions - what Veronelli (Citation2016) refers to as the coloniality of language.

Southern linguists have long recognised that multilingualism in one setting and community is not the same as in another (Heugh, Citation2017)Footnote1. This is evident in the work on multilingual fluidity of Srivastava (Citation1990) and both horizontal and vertical multilingual fluidity (see Agnihotri, Citation1995; Westcott, Citation2004). These run through the work of many South Asian scholars, including those of the Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysore (e.g. Agnihotri, Citation1995, Citation2007; Dua, Citation2008; Pattanayak, Citation1990; Mohanty, Citation2010), and linguists from Africa (e.g. Bamgbose, Citation1987; Letele, Citation1945; Obanya, Citation1999). Importantly, they predate claims of ‘new’ insights into multilingualism that have burgeoned since 2010 (e.g. Oostendorp, Citation2022).

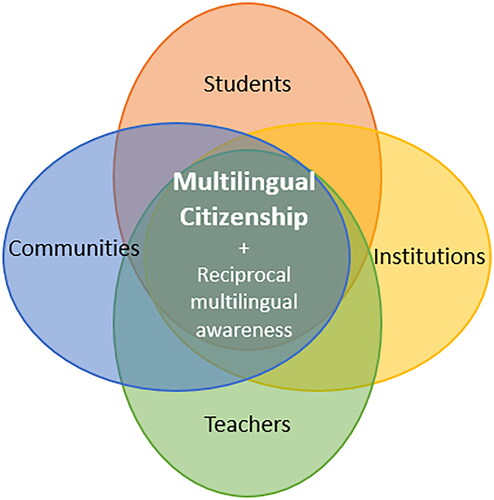

The notion of reciprocal multilingual awareness (RMA) can be of use to teacher education by supporting teachers to reflect on the multiple positionalities that need to be considered when the ultimate purpose is linguistic citizenship (). Just as multilingualism must be thought of as plural from a southern epistemic stance, so too must we consider the complexity and situatedness of language awareness. Awareness of how multilingualism is implicated in and operationalised through hierarchical post-colonial technologies of power, and how and under which circumstances these require compliance or permit artful resistance and linguistic agency is learned from an early age in familial and community settings (e.g. multilingual children in border communities in NW Uganda, Wolff, Citation2000). Resistance towards and compliance with (post-)colonial language regimes carry both risk and reward for individuals and communities. Navigating and deploying one’s multilinguality to achieve conviviality and to circumvent socio-political and economic risk is learned outside formal educational structures. However, it is expected that formal education will open doors to fulfil aspirations through one or more languages of power.

Dimensions of reciprocal multilingual awareness

We theorise reciprocal multilingual awareness as a stance that teachers might seek to develop alongside other actors as a way of co-constructing linguistic citizenship, involving four key dimensions (see ). In the first instance, shown in the first line of , the directionality of multilingual awareness is multiplied, so rather than knowledge embedded in linguistic theory or policy providing the lens through which teachers and linguists interpret student and community multilingualism, teachers, teacher educators and linguists listen attentively to students, multilingual teachers and community, before responding. Treading carefully to understand how the threads of multilingualisms are woven through individuals’ linguistic repertoires and capabilities requires listening to what differently positioned subjects say about and what they do with language and the explicit linguistic choices they make. This is in keeping with proposals for multilingual awareness in accounts of organic, locally developed programs that emphasise the multiple directions in which awareness can flow (see, for example, Bock & Stroud, Citation2021; Hedman & Fisher, Citation2022; Mary & Young, Citation2017; Melo-Pfeifer, Citation2015; Prasad & Lory, Citation2020;).

Table 1. Dimensions of reciprocal multilingual awareness (RMA).

RMA is not merely functional but evaluative, being fashioned and purposed in multiple ways through individual choice, often embedded in collective political engagements in response to voluntary collaborations, resistance, or surveillance. Within awareness, we therefore highlight multilingual sensibility - which we use here to refer to the ability to appreciate and situate the ideological weight of particular multilingual practices within linguistic, institutional and metapragmatic regimes. For example, this sensibility comes into play when multilingual students judge when to use the primary language of school assessment and when to draw on other linguistic repertoires in completing an assignment.

RMA, as a practice through which teachers and students might seek or strive towards decoloniality, pays attention to how multilingual sensibilities are organised by axes of solidarity and hierarchy, or what has been referred to as horizontal and vertical uses (Heugh, Citation2021). Horizontal multilingualism refers to relatively unmonitored and open communicative contexts, whereas vertical multilingualism refers to more tightly regulated and monitored contexts, in which language contributes to gatekeeping - as in school examinations, legal proceedings, for scientific and technical precision, and specific career paths. Awareness of the ways in which these axes are constructed, reinforced, appropriated, subverted and redefined, is the task we see for teacher education informed by southern theorisation of multilingual awareness. RMA seeks to open pathways for local and wider societal power relations, including of coloniality, to be challenged by transformative pedagogical actions. The relative positioning of practices as horizontal or vertical is reflective of coloniality, but also unstable and open to challenges by local strategies which shift the locus agency from external definitions to internal resignifications that meet the needs of multilingual subjects.

Illustrating reciprocal multilingual awareness

We illustrate the dimensions of RMA with examples from research conducted in different ‘southern’ contexts (summarised in ). These examples have been developed through convivial and dialogical discussions, involving reflective and analytical reciprocities among the authors. They draw on field-notes and excerpts from projects described in greater length elsewhere. Each author engaged in reciprocal conversations with interlocutors that include more than one community member, student or teacher. In the spirit of conviviality and communality, participants in the original studies drew on their multilingual repertoires to serve as multilingual brokers (interpreters) to ensure reciprocity in meaning-making. Our examples are presented here in short form that include references to more detailed accounts, as our purpose is to offer breadth of contextual coverage in support of our conceptual work. Pseudonyms are used for all participants.

Table 2. Illustrations of RMA across research settings.

The first three examples draw on ethnographic and longitudinal research conducted in different South Australian settings. The first places the lens on ethnographic research focussing on Anangu literacies with members of a remote community in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara Lands (Armitage, Citation2021, Citation2023). Field-notes taken over several long-term and shorter visits in 1991 and again between 2011 and 2022 inform the discussion in which we recognise multilingual reciprocity and citizenship. The second example focuses on a suburban school where teachers and students negotiate the standing and value of multilingual practices as part of learning strategies. It draws from interview records of an ethnographic study conducted with multilingual secondary school students over a period of three years and in which the lens is directed to students’ agency in constructing multilingual approaches to learning and classroom culture (Davy & French, Citation2018; French, Citation2016, Citation2019). The third example, drawing from a longitudinal series of studies in a higher education institution, shows how multilingual students’ use their expertise in translation, transknowledging (reciprocal knowledge exchange) and multilingual agency (citizenship) in meaning-making. They use their linguistic citizenship to resist institutional anglonormativity (Chang, n.d.; Heugh et al., Citation2022). The final example is from a teacher education course in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, involving a study of student responses to a range of approaches to critical literacy (Windle, Citation2020), drawing here on student-teacher journals.

Redirecting multilingual awareness through community agency

My granddaughter’s a good girl. That’s why she learns. Paluru kulini. Uwa, wangka kutjupa. My granddaughter ninti pulka. Nganana wangka kutjupa. Uwa, ngayulu wangkapai telling stories kulilpai. Paluru tjitji palya good way. (Field notes, Debra, July 2015).

[Translation: My granddaughter’s a good girl. That’s why she learns. She listens and understands. Yes, I speak different languages. My granddaughter is really smart. We speak different languages. I talk to her and tell her stories. Yes, this child is alright.]

The Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands of central Australia comprise a remote region with an almost entirely Anangu population, but schools in which most teachers are Piranpa or non-Indigenous outsiders. Piranpa teachers arrive with little insight into community language practices and ideologies, and few resources through which to construct such insight (Schulz, Citation2007). Teachers often bring a salvationist attitude to language and literacy at school (Schulz, Citation2017), with sometimes clumsy attempts at multilingual inclusivity such as ‘cheat sheets’ of translations of classroom commands from English to Pitjantjatjara. Against this backdrop the multilingual knowledge and experiences of Anangu children and their families risk falling into a ‘lingua nullius’ (Arnold, Citation2016; French et al., n.d.) of invisibility.

Piranpa teachers moving to the APY Lands are likely to find themselves in cultural contexts for which the anglonormative system of education has not provided training (Schulz, Citation2007). To recognise the linguistic landscape in which the EMI school is set, teachers must be able to observe, recognise and understand the multilingual capabilities of Anangu students at school and the multilingual ecologies of the communities in which these schools are located. It is more likely that Piranpa teachers will perpetuate an imposed ‘lingua nullius’ approach to Aboriginal languages where these are not acknowledged as assets. Significant meaning making is controlled through the content and instructional language of English while local languages and knowledges are eclipsed (Armitage, Citation2023). In some instances, Aboriginal learners of English are at risk of being mis-identified by teachers and speech therapists as having simple language skills because of their lack of training and awareness of local languages and learners’ levels of English (Gould, Citation2008). First Nations children internationally are more readily falsely identified as having special needs or learning difficulties than as being in the process of acquiring another language. The reasons for this blindness stems from prejudicial historical colonial understandings and are evidence of the ongoing racism that has stemmed from northern thinking (Gould, Citation2008, Citation2009). Along with blindness towards the multilingual sensibilities of Anangu families necessarily goes an inability to understand the connections between land, heritage and language (Tankosić et al., Citation2022).

Armitage’s experiences as a curriculum consultant and researcher on the APY lands have brought her into conversation with local community members who provide valuable insights into the dynamics of horizontal and vertical multilingual practices across the different spaces through which individuals and family groups move. In the APY Lands, incommensurate multilingualisms exist inside and outside of schools, in response to quite distinctive norms and knowledges. Within school, the curriculum is English-language and many teachers speak only English. Multilingualism is not ‘intentionally valued or fostered’ (Oliver et al., Citation2021, p. 10) and translanguaging is not a key classroom strategy for navigating differences or understandings. Rather, skillful interpreting by Aboriginal Education Workers, (locally called Anangu Educators), who conduct their pedagogy almost entirely in local languages, generates some of the most productive spaces for learning. By contrast, outside of school English is minimally present, and looked upon as out of place.

Mobility and multilingualism have been confirmed as essential to Aboriginal people, including Anangu, (Mühlhäusler & Rose, Citation1997; Oliver et al., Citation2021) and are key to understanding the language ecologies of Anangu children and families. The directionality of multilingual awareness in an Anangu community arises from long and complex histories of language ecologies and is at the centre of the stories shared by Western Desert woman Debra and recorded in Armitage’s field notes. Debra recounted stories from her infancy spent on her father’s Country in Western Australia and lamented that no one hears his language, Wajarri, spoken any more. Guided conversations were held on the APY Lands between 2011 and 2020 and Debra’s collaboration focussed on the schools attended by her grandchildren, in South Australia (SA), Western Australia (WA) and Northern Territory (NT). Debra’s grandchildren communicate in Pitjantjatjara, Kriol, Kaytetye, Ngaanyatjarra, Aboriginal English and Standard Australian English. Debra’s adult daughter, Sarah, is also fluent in these languages, and she and her children move between several homes during the course of the year, homes in which family members have their own preferences and habits of language. She commented on the linguistic experiences of her grandchildren in the local English Medium of Instruction (EMI) government school in South Australia with mainly monolingual Piranpa teachers, comparing this with the children’s experiences in a bilingual school in Northern Territory and in Anangu community settings.

Debra describes her grandchildren as knowing ‘lots of languages’ because of their father’s home in the NT. Her son-in-law lives in Tara community where his extended family participated in the development of the Kaytetye (alternative spelling ‘Kaytej’) dictionary project and where this formal work on multilingual awareness encourages children’s agency in their learning through development of their multilingual identities. Sarah reports that her children are happy when they go to the NT school because English is not the main language spoken and written there and members of their extended family work at the school, making communication easier for the family. She considers her children to be smart and successful in English schooling, which is helpful to them when on the APY Lands where English is the main language used at school. Debra adds that, should there be issues with the APY school that Sarah cannot resolve, her grandchildren can always go to other places. The assertion of agency of Debra’s family comes through their mobility and multilingualism, permitting a potential conflict with Piranpa teachers to be dealt with by removing themselves through family mobility and returning to a place that promotes multilingual identities, provides opportunities for children to reclaim ‘voices that have been silenced by a curriculum and teaching practices that have not been acknowledged for what they have to offer’ (Oliver et al., Citation2021, p. 12).

Reciprocal language awareness, in this context, means directing recognition and priority to the language choices and definitions proffered by the First Nations peoples who are engaging with formal and informal education across overlapping multilingual regimes of settler-state and local community.

Recognising high school students’ multilingual sensibilities

Students don’t have to speak only English at school. They can use other languages beside their mother language, an example which I have is that I grew in Pakistan but my nationality is Afghanistan. Although the language of these two countries are not the same but I can understand and can speak both of them. I have never been to Urdu school but I learnt it by watching cartoons in Urdu language. Apparently Urdu is similar or close to the same as Hindi. So, sometimes I speak in Hindi with my Indian friends which helps me to improve my Urdu. (Faria)

This statement comes from a student attending an urban Australian girls’ secondary school community where over 40 languages and cultures are represented, and almost half the students speak languages different from English at home (French, Citation2016). With peers, students strategically apply horizontal multilingual practices for cooperative interpersonal purposes, drawing from shared repertoires across multiple named languages. Accustomed to multilingual communication in southern contexts from which they have travelled or migrated, these students identify and make use of the shared linguistic resources that will bring to their interaction optimal meaning, status, rapport and ease. Rather than the politically and institutionally endorsed language of English, the shared linguistic resources between students included Urdu-Hindi, Cantonese and isiXhosa. These languages support learning and social inclusion amongst students. In the quotation opening this section, Faria, a Year 10 student, explained the dynamism and strategic potential of her multilingual repertoire. Similar to Faria, flexible shared use of Urdu-Hindi became a medium of communication for students with home languages as diverse as Hazaragi, Pashto, Tamil or Gujarati.

However, despite the multilingual richness in evidence in this setting, promotion of multilingualism in the classroom, by teachers who are less attuned to the subtleties of unequal language regimes in a given institutional location, may enter into conflict with students’ more sophisticated multilingual awareness. French (Citation2016, Citation2019), a teacher and researcher at the school, through supportive discussions of classroom plurilingualism with students found a keen appreciation for the interaction of individual agency with power at an institutional level. Students in this setting make judgements (develop a multilingual sensibility) ‘in collaboration with or resistance to’ language policy at the school level and within the educational system more broadly (Heugh, Citation2018, p. 175). Here, the distinction between horizontal and vertical languaging practices is important to the judgements that students form. In this case, a distinction between multilingual learning practices (horizontal) and academic English textual production for assessment (vertical).

Students develop their multilingual sensibilities through experiences outside of school, some of which demonstrate a sharp demarcation between different registers of home languages, the dominant language, and lingua francas, based on social situations and hierarchical relationships. They make use of multilingual resources in navigating situations in which vertical protocols and use of language occurs, such as brokering high-stakes institutional interactions in which they often play roles as interpreters (e.g. with medical professionals).

Vertical language practices associated with social hierarchies also apply across named languages in the school setting. Originally from Vietnam, student Hana explained the connection between status and language choices. She said, ‘I speak with Ms [teacher name] in Vietnamese. … Because she speak in Vietnamese. … So I guess that we just pay respect by doing the same thing.’ The value placed on academic registers of language extends beyond English to varieties of students’ home languages. In their focus group interview, Afghan Hazara student Selena distinguished between her home language and the language taught in after-school classes. She explained, ‘The language here we do is Persian, it’s like really formal language. Whereas I speak like. … Hazaragi.’ She suggested Hazaragi is seen from this perspective as ‘a made up language.’ Connected multilingual repertoires provide important resources for socialising and learning within the school context, but students also consider a range of complex factors when making decisions to acquire and deploy vertical proficiencies related to each of their named languages.

Students are equally strategic in choosing the linguistic resources that will give them the academic outcomes they seek. Teachers’ promotion of multilingualism in the classroom could be most productively informed by reciprocal multilingual awareness in this scenario. Appreciation for student linguistic decision-making was evident in the reflections of a teacher who offered his drama students the chance to perform their Shakespearean roles in any language. One student, Victoria, chose to perform in her home language of Dinka, while another student, Molly, declined her teacher’s suggestion of performing in her home language of Cantonese. The teacher noted ‘each person wants to acquire something different. Maybe Victoria wanted to acquire the opportunity to act, and Molly wanted the opportunity to … learn Shakespeare and acquire Shakespeare as Shakespeare, not Shakespeare as acting.’ Victoria and Molly’s language choices supported different goals for learning. When focused on the high stakes of academically demanding and assessed tasks, students such as Molly make a strategic choice to focus on the vertical hierarchies of English understood to be valued, and rewarded, in the education system.

The complex, dynamic and responsive practice of these students illustrates organic multilingual awareness in the particular context of this Australian secondary school. In their enactment of linguistic citizenship, these young women demonstrate linguistic and sociolinguistic expertise, strategic decision making and agency in their application of different linguistic resources, sometimes translingual and at other times monolingual, to particular situations and outcomes. Rather than subscribing to the colonial fantasy of a single unifying national language, these students make strategic choices to communicate using shared multilingual resources that simultaneously support understanding and interpersonal connection. In drawing differentially on horizontal and vertical linguistic practices, these students demonstrate sharp multilingual sensibility in interpreting the teachers’ and school’s positioning within educational language regimes.

Transforming pedagogical relations through higher education institution students’ multilingual awareness

If you gonna say no to online translations, you have to say no to international students. What is the point of letting them come here and make it hard for them? (Multilingual student)

Attentiveness to community and student accounts of their multilingual sensibilities can offer valuable insights for teachers and there is scope for such conversations to result in institutional change. Here we draw from a longitudinal series of studies on Higher Education Institution (HEI) students’ multilingual capabilities in translation and transknowledging (Heugh et al., Citation2022), and research of students’ use of machine translation and the metacognitive processes involved in post-editing machine translated texts (Chang, Citation2022, n.d.). This research occurs on the margins of English(-only) medium instruction (EMI) teaching and assessment regimes in globalised HEIs. The researchers and their research collaborators seek to use insights from dialogue with multilingual students to generate changed pedagogical relations that acknowledge and value strategic use of multilingualism that includes human and machine translation (Chang, Citation2022; Heugh et al., Citation2022).

In anglophone Australian institutions somewhat ambivalent towards multilingual students’ use of language technologies, multilingual students are typically viewed as language deficient or labelled ‘English second language learners’ or ‘international students’ (a term often used in Australian HEIs as a code for ‘non-native speakers’ of English). Consequently, students frequently attest to lack of confidence and a sense of isolation or marginality. Yet, learning about student uses, views, and agency in human and machine translation provides rich insights for classroom pedagogy, including peer-learning. When curriculum, pedagogy and assessment design deliberatively encourage students’ multilingual and epistemological capabilities, voices and pluralities, students demonstrate a keenness to exercise linguistic citizenship. At the institutional level, they challenge regimes of language and universalist epistemes (such as a singular ‘northern’ definition of multilingualism, or ‘western’ source of knowledge) that invisibilise those beyond the anglonormative world, particularly in assessment. More than challenge, they bring innovations for teaching and learning of languages and disciplines across higher education with implications for schools and HEIs. These include shifting deficit framings of multilingual students to knowledge brokers upon whom monolingual English-speaking students become dependent (Heugh et al., Citation2022).

Even with overt endorsement of artificial intelligence and digital technologies, teaching staff in this EMI institution are unsure of how to navigate assessment criteria and protocols in relation to translation technology. This is despite a longitudinal study of students (cited below) in which students’ recognition, development and use of bi-/multilingual and translation capabilities has rendered substantial evidence of the value of multilingual pedagogies and translation for both international and domestic students. For example, undergraduate bi-/multilingual students demonstrate linguistic (or multilingual) citizenship in mentoring monolingual peers in linguistics courses on how to access and use translation technology to access information beyond English. In defiance of regimes that attempt to stigmatise its use, students vocalise their agency in the use of translation technologies: ‘If you gonna say no to online translations, you have to say no to international students…?’ (Multilingual student, Heugh et al., Citation2022, p. 113). Student views such as these, noted by their lecturers, circulate among academic integrity officers in several local HEIs and in international platforms in an effort to alter deficit views of international or multilingual students and the use of both human and machine translation. As Mundt and Groves (Citation2016) have found elsewhere, it behoves HEIs to act proactively rather than reactively, because: ‘… [S]students just ignore what the university says…. students will still just do whatever they want because they’ve been doing it for a long time’ (HEI teacher-researcher, Heugh et al., Citation2022, p. 113).

Xiang, a bilingual graduate student having to grapple with multiple complex academic texts in English at the same institution argues, ‘…as long as you know how to cite the resource [source] of information correctly. It doesn’t matter whether you translate the information by using your own language knowledge or MT [machine translation]’ (Chang, Citationn.d.).

Yun, another graduate student, signalling frustration at the monolingual habitus and lack of academic staff and institutional understanding of bilingual students’ cognitive linguistic processes involved in post-editing of machine translated text argues, ‘… we don’t just copy and paste…we still double check if that [MT output] is what we want to express and [then we] modify our own writing, hence it’s still our own work’ (Chang, Citationn.d.).

Chang’s data uncovers and draws particular attention to how students explain their expert use of machine translation followed by a process of post-editing of the machine translated text. This complex metalinguistic and metacognitive process indicates high level multilingual expertise of the kind entirely invisible or unknown to most academics and is misunderstood by the institution’s academic integrity officers.

In our data we regularly see students using their horizontal multilingualism in spoken discourse inside and outside of the classroom, and then engaging in processes in which they recognise, collaborate with, and find resources (translation technology) to ‘get around’ or conform to academic assessment regimes (‘academic’ or vertical use of English). When confronted with the surveillance of academic integrity regimes and insensitivity to the affordances of equal access to and delivery of knowledge that language technology offers, multilingual students employ linguistic agency subversively (see also Mundt & Groves, Citation2016). However, when invited to voice their views without punitive consequences, students indicate clarity of purpose (i.e. to produce the most viable outcome in academic or vertical use of English) and how their multilingual resources and expertise (in human and machine translation) can be deployed. Multilingual students in contexts such as this HEI encounter multiple points at which vertical language regimes have to be navigated each day. It is a risk they take. Access to and participation in opportunities to acquire expertise in ‘academic use of English’ for future careers requires deft deployment of their multilingual capabilities and expertise to move between horizontal and vertical dimensions of language and regimes of language. The depth of multilingual capability and discernment acquired and honed by students such as these is beyond the reach of most teaching staff, and it is students who share this expertise in reciprocal and transformative pedagogical moves with peers and with teachers who care to listen. These data problematise monolingual regimes in education immune to the metalinguistic cognitive complexities involved in both human and machine translation. The data unsettle anglonormative assumptions in the institution, and offer transformative pedagogical insight to student linguistic agency, resistance and the metalinguistic processes of translation and knowledge exchange that have value for CMLA and HEIs located in the south (see also, Bock & Stroud, Citation2021).

Shifting the locus of agency in local appropriations of ‘global’ theories in Initial Teacher Education

With the many accents present across the large extent of our country, it is no surprise that a ‘Brazilian English’ accent and its variations exist, and speakers should not be forced to follow almost imperialist standards on how their pronunciation of a foreign language is supposed to be. (Luan)

So far we have focused on ways in which the directionality of multilingual awareness may be expanded by careful listening to and observing community and student agency and voices, particularly as these attend to horizontal and vertical linguistic regimes that bear the markings of coloniality. However, it is worth emphasising again that multilingual awareness is situated, contingent and evolving, including amongst pre-service teachers themselves, including in the ways that ‘global’ theories are appropriated. Reciprocity can also be thought about in terms of local appropriations of models of multilingual awareness that come from ‘outside’.

In the context of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) in Brazil, where Windle (Citation2020) has undertaken research into his own practice as a teacher educator, this is clear in how students take up and subvert hegemonic linguistic regimes indexed by English, engaging with ‘northern’ framings that provide an opening for them to exploit. In Brazilian higher education, the expectation from teacher educators, and the academy in general, is that linguistic knowledge generated in North America and Europe arrives in the form of academic theories that are applied in undergraduate courses and are frequently mediated by teacher educators’ own direct contact with the primary centres of northern knowledge production through postgraduate studies they have undertaken (Almeida, Citation2021; Moita-Lopes, Citation1996). This includes close connections to French and US linguistics, as well as theories of language education, such as the audio-lingual and communicative approaches, English for Specific Purposes, and English as a Lingua Franca.

In a university topic taught by Windle, students used reflective journals to respond to the ideas of English as a Lingua Franca presented by canonical northern authors, such as Jennifer Jenkins. In doing so, they showed a reciprocal stance of speaking back by using ELF precepts to identify coloniality in the ways in which English has been present in their own lives as students and English language instructors in commercial coursesFootnote2. They emphasised a multilingual sensibility in ELF and recontextualized it as part of multilingual and polyphonic identities grounded in local political struggles involving the colonial legacies of Portuguese - that is, debates over the imposition of a pseudo-European norm (sometimes termed the Educated Urban Norm) versus the acceptability of rural, regional and Afro-Brazilian registers of Portuguese. Students linked ELF and debates over language ideologies in Portuguese through a critique of cultural imperialism (see, also, Cogo & Siqueira, Citation2017). Such a critique incorporates students’ broader political awareness, which emerges from Brazil’s turbulent political history and students’ positionality as part of the recent mass expansion of higher education to include a broader spectrum of society, and which has placed pressure on elitist linguistic norms promoted by universities.

The following journal excerpt by a pre-service teacher illustrates connections made between ELF and the embrace of cultural diversity and linguistic diversity within Brazil:

I believe that the ELF [English as a Lingua Franca] method is the best way to help students learn English pronunciation without discriminating between accents. It helps to deconstruct the idea that good English is only the American one while promoting the valorization of cultural diversity. Talking about Brazil, the discrimination against accents is also a concern. In Brazilian Portuguese, in my view, the most valued accents are those of the cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The other modalities, mainly further north of Brazil, in the interior, are often linked to a lack of intelligence and school education. Besides, in various situations, speakers might find it difficult to be taken seriously. (Anna).

As multilinguals we can be proud of our culture reflected in our speech and in our ability to communicate in more than one language, without being ashamed of it. (Eliane)

Oppression is profit, therefore, by raising the image of a nation and its language above others, you create a kind of longing, for people who live in the least favoured countries, to belong to the dominating nation… So instead of practising such horrible methods, why don’t those courses choose to start preaching the varied use of language, celebrate the thousands of origins of the speakers? For that would not generate profit and would put a brake on the wheel of oppression that keeps capitalism active and projecting itself into the future. That is why I see the teaching of English as a Lingua Franca as a revolutionary attitude. In doing so, we will break a system that restricts the global use of language. In addition, we will also humanize the image of the student who until now has only been inferiorized by the hierarchical view of languages. (Sandra)

Nowadays, as an English-speaking language consumer, I am learning to unlearn in order to acquire other ways to speak the English language, such as Jamaican, South African English and the like, which, in turn, are some among other variations that are invisible due to this industry that regulates to the detriment of other possibilities of expressing oneself. (Natan)

Conclusion

In this paper we have illustrated reciprocal multilingual awareness (RMA) as an orientation to learning that responds to southern theory of linguistic citizenship and multilingualisms. This orientation is sensitive to local orders of relevance and value. At times we see horizontal flows of expertise in multilingualism, at other times complicity with, or resistance to, vertical regimes of language and multilingual dynamics. Our analysis rests upon a longue durée of research and south-south collaborative theoretical conversations in the spaces in which southern multilingualisms thrive, and with agents who, with heightened awareness, purpose and sensibility, employ these multilingualisms from below.

In each example, dialogue with local actors offers the potential of more nuanced understandings of multilingualism awareness through attention to directionality, multilingual sensibilities, pedagogical transformation, and locus of agency. Language awareness that focuses on these dimensions, offers a purchase for teachers and students to challenge unjust institutional and societal linguistic norms, without prescribing a single, pre-ordained, vision of multilingual harmony.

The example s presented in this paper point to the importance of reciprocal multilingual awareness that is defined by provisionality, shaped by centre and periphery (Windle et al., Citation2020), and tensions between horizontal and vertical dynamics of language practices and regimes. In particular, we have drawn attention to the navigation of intersecting and overlaid multilingual regimes as they operate in different spaces (school, amongst peers, in curriculum policy) and in different relationships (amongst kin, peers, with outsiders). The ways in which languages are named, mobilised, and judged are subject to the identities and relationships invoked in proximal scales of interpersonal interaction, and in institutional and historical scales of coloniality. For these reasons, we invite south-north conversations of pluralities, while also rejecting grand narratives that lean towards prescriptive and narrow doxa. However unintentional, universalist assumptions that speak to and overwrite the voices of agents often assumed to be subaltern, fail to recognise the multilingual agency and citizenship held and exercised in community, and by students, and often, also teachers (Armitage, Citation2023; French, Citation2016; Osborne, Citation2021; Oostendorp, Citationn.d.).

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the reviewers for their valuable suggestions that have shaped the paper in important ways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Northern, here, refers to the epistemological and ontological claims of modernity, rather than a set geopolitical space. By contrast southern theory (Connell, Citation2007) or southern epistemologies (e.g., de Sousa Santos, Citation2018; Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018), refer to knowledge that has been marginalised by the intellectual project of modernity, or which centres the experiences and claims of populations marginalised by coloniality.

2 Many pre-service teachers are employed as instructors from the time that they are teenagers. Pre-service teachers are often successful graduates of such courses (Almeida, Citation2021).

References

- Agnihotri, R. K. (1995). Multilingualism as a classroom resource. In K. Heugh, A. Siegrühn, and P. Plüddemann (Eds.), Multilingual education for South Africa (pp. 3–7). Heinemann.

- Agnihotri, R. K. (2007). Towards a pedagogical paradigm rooted in multilinguality. International Multilingual Research Journal, 1(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313150701489689

- Almeida, R. L. T. (2021). Language education in English as an additional language in Brazil: Overcoming the colonial practices of teaching English as a foreign language. Gragoatá, 26(56), 935–961.

- Andreotti, V., & de Souza, L. M. (2008). Translating theory into practice and walking minefields: Lessons from the project ‘Through Other Eyes. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 1(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.01.1.03

- Armitage, J. (2021). Desert participants guide the research in central Australia. In K. Heugh, C. Stroud, K. Taylor-Leech, & P. De Costa (Eds.), A sociolinguistics of the south (pp. 214–232). Routledge.

- Armitage, J. (2023). Anangu literacy practices unsettle northern models of literacy. In S. Makoni (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and the Global South (pp. 397–411). Routledge.

- Arnold, L. (2016). Lingua nullius: A retrospective and prospect about Australia’s first languages [Paper presentation]. 2016 Lowitja O’Donoghue Oration, Don Dunstan Foundation, University of Adelaide.

- Bamgbose, A. (1987). When is language planning not planning? Journal of West African Languages, 7(1), 6–14.

- Bock, Z., & Stroud, C. (Eds.). (2021). Language and decoloniality in higher education: Reclaiming voices from the south. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Chang, L. C. (2022). Chinese language learners evaluating machine translation accuracy. The JALT CALL Journal, 18(1), 110–136. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v18n1.592

- Chang, L. C. (n.d.). Investigation of post-editing of machine translation (PEMT) in advancing reading and writing capability of English and Chinese language learners in higher education [PhD Thesis]. University of South Australia.

- Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science. Polity Press.

- Cogo, A., & Siqueira, S. (2017). Emancipating myself, the students and the language: Brazilian teachers’ attitudes towards ELF and the diversity of English. Englishes in Practice, 4(3), 50–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/eip-2017-0003

- Daniels, B., Sterzuk, A., Turner, P., Cook, W. R., Thunder, D., & Morin, R. (2021). ē-ka-pimohteyāhk nīkānehk ōte nīkān: Nēhiyawēwin (Cree Language) Revitalization and Indigenous Knowledge (Re) generation. In A sociolinguistics of the south (pp. 199–213). Routledge.

- Davy, B., & French, M. (2018). The Plurilingual Life: A tale of high school students in two cities. In J. Choi & S. Ollerhead (Eds.), Plurililingualism in Teaching and Learning (pp. 165–181). Routledge.

- De Costa, P. I. (2021). Framing ‘Sociolinguistic Methods of the South’. In K. Heugh, C. Stroud, K. Taylor-Leech, & P. I. De Costa (Eds.), A sociolinguistics of the south (pp. 191–198). Routledge.

- de Sousa Santos, B. (2018). The end of the cognitive empire: The coming of age of epistemologies of the South. Duke University Press.

- Devy, G. N., Davis, G. V., & Chakravarty, K. K. (Eds.) (2015). Knowing differently: The challenge of the indigenous. Routledge.

- Dua, H. (2008). Ecology of multilingualism, language, culture and society. Yashoda Publications.

- French, M. (2016). Students’ multilingual resources and policy-in-action: An Australian case study. Language and Education, 30(4), 298–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2015.1114628

- French, M. (2019). Multilingual pedagogies in practice. TESOL in Context, 28(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.21153/tesol2019vol28no1art869

- French, M., & Armitage, J. (2020). Eroding the monolingual monolith. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 91–114. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v3n1.302

- French, M., Stanford-Billinghurst, N., & Armitage, J. (n.d.). Multilingualism, masking and multitasking - spaces of hopefulness. In S. Dovchin, L. Wei (Eds.), Translinguistics and precarity. Cambridge University Press.

- García, O. (2017). Critical multilingual language awareness and teacher education. In J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, & S. May (Eds.), Language awareness and multilingualism, Encyclopedia of Language and Education (pp. 263–280). Springer International.

- Gould, J. (2008). Language difference or language disorder: Discourse sampling in speech pathology assessments for Indigenous children. In J. Simpson, & G. Wigglesworth (Eds.), Children’s language and multiculturalism: Indigenous language use at school and at home (pp. 194–215). Continuum Press.

- Gould, J. (2009). There is more to communication than tongue placement and ‘show and tell’: discussing communication from a speech pathology perspective. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 29(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268600802516384

- Hedman, C., & Fisher, L. (2022). Critical multilingual language awareness among migrant students: cultivating curiosity and a linguistics of participation. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, August, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2022.2078722

- Heugh, K. (2017). Re-placing and re-centring Southern multilingualisms. A de-colonial project. In C. Kerfoot & K. Hyltenstam (Eds.), Entangled discourses. South-North orders of visibility., (pp. 209–220). Routledge.

- Heugh, K. (2018). Commentary - Linguistic citizenship: Who decides whose languages, ideologies and vocabulary matter?. In L. Lim, C. Stroud, & L. Wee (Eds.), The Multilingual Citizen: Towards a Politics of Language for Agency and Change (pp. 174–192). Multilingual Matters.

- Heugh, K. (2021). Southern multilingualisms, translanguaging and transknowledging in inclusive and sustainable education. In P. Harding-Esch & H. Coleman, Language and the Sustainable Development Goals., (pp. 33–43) British Council.

- Heugh, K. (2022). Linguistic citizenship as a decolonial lens on southern multilingualisms and epistemologies. In Q. Williams, A. Deumert, & T. Milani (Eds.), Struggles for multilingualism and linguistic citizenship., (pp. 35–38). Multilingual Matters.

- Heugh, K., French, M., Arya, V., Pham, M., Tudini, V., Billinghurst, N., Tippett, N., Chang, L.-C., Nichols, J., & Viljoen, J.-M. (2022). Multilingualism, translanguaging and transknowledging: Translation technology in EMI higher education. AILA Review, 35(1), 89–127. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.22011.heu

- Heugh, K., & Stroud, C. (2019). Diversities, affinities and diasporas: A southern lens and methodology for understanding multilingualisms. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2018.1507543

- Heugh, K., Stroud, C., Taylor-Leech, K., & De Costa, P. I. (Eds.) (2021). A Sociolinguistics of the South. Routledge.

- Letele, G. L. (1945). A preliminary study of the lexicological influence of the Nguni languages on Southern Sotho. (No. 12). University of Cape Town.

- Lim, L., Stroud, C., & Wee, L. (2018). (Eds) The Multilingual Citizen: Towards a Politics of Language for Agency and Change. Multilingual Matters.

- Mary, L., & Young, A. S. (2017). Engaging with emergent bilinguals and their families in the pre-primary classroom to foster well-being, learning and inclusion. Language and Intercultural Communication, 17(4), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1368147

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2015). Multilingual awareness and heritage language education: Children’s multimodal representations of their multilingualism. Language Awareness, 24(3), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1072208

- Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press.

- Mohanty, A. K. (2010). Languages, inequality and marginalization: Implications of the double divide in Indian multilingualism. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2010(205), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2010.042

- Moita-Lopes, L. P. d. (1996). Yes, nós temos bananas” ou “Paraíba não é Chicago não. Um estudo sobre a alienação e o ensino de inglês como língua estrangeira no Brasil. Oficina de Lingüística Aplicada. Mercado de Letras. 37–62.

- Mühlhäusler, P., & Rose, D. (1997). The linguistic ecology of Anangu Pitjantjatjara communities. In Desert Schools research report, Vol. 2 An investigation of English language and literacy among young Aboriginal people in seven communities (pp. 179–215. National Children’s Literacy project, University of Adelaide.

- Mundt, K., & Groves, M. (2016). A double-edged sword: The merits and the policy implications of Google Translate in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2016.1172248

- Nakata, M. (2007). Disciplining the savages, savaging the disciplines. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Obanya, P. (1999). Popular fallacies on the use of African languages in education. Social Dynamics, 25(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533959908458663

- Odora Hoppers, C. A. (Ed.). (2002). Indigenous Knowledge and the Integration of Knowledge Systems: Towards a philosophy of articulation. New Africa Books.

- Oliver, R., Wigglesworth, G., Angelo, D., & Steele, C. (2021). Translating translanguaging into our classrooms: Possibilities and challenges. Language Teaching Research, 25(1), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820938822

- Oostendorp, M. (2022). Linguistic repertoire: South/North trajectories and entanglements. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 17(4), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2023.2207071

- Oostendorp, M. (n.d.). Undoing competence – a challenge from the South: A commentary on “Undoing Competence: Coloniality, homogeneity, and the overrepresentation of whiteness in applied linguistics”. Language Learning, https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12536

- Osborne, S. (2021). Aboriginal Agency, Knowledge, and Voice: Centring Kulintja Southern Methodologies. In K. Heugh, C. Stroud, K. Taylor-Leech, & P. De Costa (Eds.), A sociolinguistics of the south., (pp. 233–248). Routledge.

- Pattanayak, D. P. (Ed.). (1990). Multilingualism in India (No. 61). Multilingual Matters.

- Phyak, P., Rawal, H., & De Costa, P. I. (2021). Dialogue as a decolonial effort: Nepali youth transforming monolingual ideologies and reclaiming multilingual citizenship. In K. Heugh, C. Stroud, K. Taylor-Leech, & P. I. De Costa (Eds.), A sociolinguistics of the south (pp. 155–170). Routledge.

- Prasad, G., & Lory, M. P. (2020). Linguistic and cultural collaboration in schools: reconciling majority and minoritized language users. TESOL Quarterly, 54(4), 797–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.560

- Schulz, S. (2007). Inside the contract zone: White teachers in Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. ‘ International Education Journal, 8(2), 270–283.

- Schulz, S. (2017). Desire for the desert: Racialising white teachers’ motives for working in remote schools in the Australian desert. Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2015.1110296

- Shepard-Carey, L., & Gopalakrishnan, A. (2023). Developing critical language awareness in future English language educators across institutions and courses. Language Awareness, 32(1), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2021.2002881

- Srivastava, A. K. (1990). Multilingualism and school education in India: Special features, problems and prospects. In D. P. Pattanayak (Ed.), Multilingualism in India (pp. 37–53). Multilingual Matters.

- Stroud, C. (2001). African mother-tongue programmes and the politics of language: Linguistic citizenship versus linguistic human rights. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 22(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630108666440

- Stroud, C., & Heugh, K. (2004). Language rights and linguistic citizenship. In Freeland, J. & Patrick, D. (Eds.), Language rights and language survival: Sociolinguistic and sociocultural perspectives (pp. 191–218). St. Jerome Publishing.

- Tankosić, A., Dovchin, S., Oliver, R., & Excel, M. (2022). The mundanity of translanguaging and Aboriginal identity in Australia. Applied Linguistics Review, https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0064

- Veronelli, G. A. (2016). About the coloniality of language. Universitas Humanística, 81, 33–58.

- Westcott, N. (2004). Sink or Swim: Navigating language in the classroom [Video]. PRAESA, Cape Town. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bJt5FVJYis

- Windle, J. (2020). Human rights as a performative context for transnationalism: Working with difference in Brazilian teacher education. In TESOL Teacher Education in a Transnational World (pp. 225–237). Routledge.

- Windle, J., Souza, A. L. S., Silva, D. D. N., Zaidan, J. M., Maia, J. D. O., Muniz, K., & Lorenso, S. (2020). Towards a transperipheral paradigm: An agenda for socially engaged research. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 59(2), 1563–1576. https://doi.org/10.1590/01031813749651220200706

- Wolff, H. E. (2000). Pre-school child multilingualism and its educational implications in the African context. PRAESA Occasional Papers. PRAESA.