Abstract

Focusing on the institutional aspects of the Kurdish women’s movement in Turkey since the 1990s the article shows how it established a consciousness within the Kurdish national movement that gender equality is a cornerstone of democracy and ethnic rights. We frame this through theories of enacting intersectional multilayered citizenship and identify three key interventions: autonomous women’s assemblies, women’s quotas in pro-Kurdish rights parties and the co-chair system where all elected positions within the pro-Kurdish parties are jointly occupied by a male and female. These have achieved a better representation of women in formal politics, rendered gender equality and sexual violence legitimate subjects of politics and contributed to establishing an aspiration for a more dialogic political ethos. While the women’s movement’s close affiliation with the Kurdish national movement has been highly effective, it also in part circumscribes gender roles to fit its agendas.

Introduction

In the recent conflict with extremist Islamist groups in the Middle East, the image of the Kurdish woman fighter has become iconic, symbolising a secular, self-confident Middle Eastern femininity, opposed to Islamization. Yet, few beyond the Kurdish community and area studies specialists, are aware of the long history of Kurdish women’s activism, without which these recent interventions of Kurdish women as fighters and organizers against Islamist violence would not have been possible.

While Kurdish women have been politically active for a long time, in the mobilizations for democratic and ethnic rights since the 1990s they came to form a mass movement challenging not only ethnic, but also gender oppression. The article begins by providing some background on Kurds in Turkey, to then present the methods, moving on to theorize enacting intersectional multilayered citizenship. We then examine how the Kurdish women’s movement established institutions and processes of increasing women’s participation and representation in formal politics, focusing on three enactments of citizenship: women’s assemblies, quotas and the co-chair system. While acknowledging that the Kurdish national movement has played an ambivalent role, both instrumentalising and promoting women’s rights, the article concludes that the Kurdish women’s movement has enacted intersectional multilayered citizenship by challenging gendered, ethnic and class oppressions on the levels of family, locality, the Kurdish national movement, as well as the Turkish state, in the process transforming understandings of who can become a political subject, which topics can legitimately become part of public political deliberation, and who can claim rights.

Background

Kurds are a ‘non-state nation’ (Mojab Citation2001), spanning territories in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, where they have been variously subjected to genocide in a long history of denial of their Kurdish identity (Ayata and Hakyemez Citation2013; Skutnabb-Kangas and Fernandes Citation2008). Kurdish identity in Turkey, or what many Kurds claim as North Kurdistan (Keles Citation2015), has been highly contested, making it difficult or even illegal to claim Kurdish identity throughout long periods of the republic’s history (McDowall Citation2007; Keles Citation2015). From the inception of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the Kurds had a problematic relationship with the state, as Kurdish ethnic identity has not been recognized, and subjected to assimilationist policies. This included the criminalization of the language and Kurdish names, the violent suppression of revolts in the 1920s and 30s and forced deportations to the west of the country.

Since the 1980s, there has been an armed conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), during which 40,000 people have been killed and more than 1 million Kurds been subjected to forced internal displacement (ECRI Citation2011). Furthermore, pro-Kurdish political parties, journalists and intellectuals have been subjected to prosecution and extra-judicial killings, especially during the 1990s (Zeydanlıoğlu Citation2008). Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the PKK, the most prominent but outlawed Kurdish party involved in armed struggle against the Turkish state, was captured in 1999 and has been in solitary confinement since. In the meantime, a number of initiatives, most recently the ‘Kurdish opening’ in 2009, aimed at improving cultural and linguistic rights such as the decriminalization of Kurdish language in public and the introduction of Kurdish broadcasting (Güneş Citation2012; Keles Citation2015). Yet, many key issues such as mother tongue teaching and a systematic democratization and adherence to human rights have not been realized. Kurdish political projects range from independence, the creation of a Kurdish state spanning territories in contemporary Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, to demands for federation and political and cultural rights within the existing borders of Turkey, or a form of regional autonomy within a projected new federal structure of Turkey (Akkaya and Jongerden Citation2014). Indeed, the Kurdish national movement in Turkey has evolved from beginnings in the 1970s in communist and anti-colonial ideologies, through to a stronger emphasis on nationalism which de-emphasised some communist principles (such as anti-religiosity) and instead aimed to bring all social and political sections of Kurdish society into a national liberation struggle in the 1990s and since the 2000s has emphasised Democratic Confederalism (Güneş Citation2012). Each of these ideological, organizational and political shifts impacted the conceptualisation of gender relations and their centrality to Kurdish nationalist politics (Çağlayan Citation2012). Currently, the Kurdish national movement in Rojava (Syria) while embroiled in a conflict with Islamist groups, is realizing a social revolution. While Western media mostly engage with the perceived novelty of Kurdish women fighters, this social revolution addresses all areas of social life, including environmental, political and economic changes. One of the key aims is to overcome patriarchal social organization. While beyond the scope of this article, many of the gender politics discussed here are also realized in Rojava (Tank Citation2017). Developing from the 1970s, the Kurdish women’s movement’s aims, organizational structures and ideologies evolved; key moments were the entry of women into the guerrilla, where they proved their significance for the wider Kurdish national movement, and developed ideologically through women’s academies and consciousness-raising (Açık Citation2003, Citation2013; Bozgan Citation2011). The most recent innovative ideological intervention has been the framework of ‘Jineolojȋ’, aiming to understand the historical roots of women’s oppression from a Kurdish point of view (rather than drawing on Western feminisms) and developing a future-oriented political project of a world beyond hierarchies and oppression within the wider project of Democratic Federalism (DÖKH and DWAA Citation2013; Öcalan Citation2013). While women-only spaces facilitated these developments, the Kurdish women’s movement also engaged the Kurdish national movement’s mixed-gender political structures, contributing to, and at times leading its political campaigns (Çağlayan Citation2007; Bozgan Citation2011).

Although engaging with these different political projects is beyond the scope of this article, it is important to underline that the Kurdish national movement is not monolithic. The turbulent nature of the politics of Kurdish rights means that the situation on the ground is fast changing. While recognizing the important roles of the Diaspora, contributions of women in highly visible leadership positions and in the armed struggle for a fuller understanding of the Kurdish women’s movement, because of limited space, here we focus on the process of institutionalization of the Kurdish women’s movement, an aspect neglected in academic publications so far. This speaks to a number of concerns in women’s activism in the region and transnationally. While most recently, the Arab Spring has resulted in a backlash against women’s public activism (Esfandari Citation2012), state sponsored institutionalized women’s movements in the Middle East have often appropriated women’s rights agendas to prove that the governments they have been affiliated with profess modern values of gender relations to the West, rather than genuine interventions into gendered power relations (e.g. al-Ali and Pratt Citation2011; Hatem Citation1994; Kandiyoti Citation1989). Different tensions between institutionalized and grassroots women’s activism are also evident in Western countries (Outshoorn Citation1994). On the other hand, we are currently witnessing how rightwing discourses argue that women’s rights are a particularly Western achievement, incompatible with non-Western cultural values to justify racism, particularly directed against (migrants from) Muslim majority countries, of which Kurds are part (Farris Citation2017). Against this backdrop, the Kurdish women’s movement’s experiences of combining institutionalization with grassroots activism, while also critically interrogating intersectional power relations of class, ethnicity, sexuality and the relationship with the environment can provide insights into alternative configurations of women’s activism. The Kurdish women’s movement’s decolonial project for gender equality also challenges the idea that women’s rights constitute a Western value.

Method

This article is based on qualitative research, including extensive documentary analysis, in-depth semi-structured interviews and observations. In-depth interviews with eight women’s rights activists in Kurdish-populated Diyarbakir were conducted between January 2014 and May 2015, in participants’ organizations, homes, and in cafes, ranging 45–130 minutes. Interviews were transcribed, coded, analysed, identifying key themes through a grounded theorizing approach (Hammersley Citation2010). Most interviewees held leading positions in a range of women’s organizations, but we also included two grassroots activists. In addition, informal interviews and observations were undertaken at eight Kurdish women’s organizations of diverse political and social orientation in Diyarbakir.

Document analysis of primary and secondary data provided ‘background and context, additional questions to be asked, supplementary data, a means of tracking change and development, and verification of findings’ from interviews (Bowen Citation2009, 30). We analysed public organizational statements, newsletters and pamphlets of women’s groups and organizations from the 1990s to present and newspaper articles on specific themes: the history, organizational practices and structures of the Kurdish women’s movement, the relationship of the Kurdish and other women’s movements and feminism, in particular to Turkish women’s movement, sexual and domestic violence and resistance to this. The analysis used ‘directed content analysis’, combining categories emerging from prior research with categories emerging from the data (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). Concepts identified in prior research draw on publications on the Kurdish women’s movement (cf. Çağlayan Citation2007, Citation2012; Bozgan Citation2011) and Açık’s (2003, 2013) extensive discourse analysis of publications of the Kurdish national and women’s movement. We employed the Popular Memory Group’s (1982) analytic notion of structural and cultural readings. Structural readings can provide factual data that are not – or only partially – recorded otherwise, elucidating the challenges of realizing new political and organizational structures (see below our interviewee Avşȋn’s comments on challenges to the co-chair system). These structural readings intertwine with cultural readings attentive to how Kurdish women give meaning to these experiences. For example, analysing the introduction of women’s quotas combines cultural and structural readings: we show how this change in political representational structure was closely intertwined with challenging gendered, ethnic stereotypes of Kurdish women as tribal, backward, and uneducated.

Bringing Kurdish women’s struggles to feminist debates beyond area studies is important to learn empirically about a group long rendered invisible and contributes to a decolonial project bringing knowledges from the South to international theorizing (Mignolo Citation2012). Requiring a critical, self-reflexive effort of translation (Gutiérrez-Rodríguez Citation2010), the research draws on multilingual primary sources in Kurdish (Kurmanji), Turkish, German and English. While acknowledging the diversity of Kurdish women’s groups this article focuses on those affiliated with the mainstream Kurdish national movement close to the PKK and legal pro-Kurdish rights parties. We refer to pro-Kurdish rights parties in the plural; since the 1990s pro-Kurdish rights parties were frequently outlawed but reorganized under different names, to effectively continue their political work. Each successor party emerged with a reformed party programme. These parties are the main legal actors representing the Kurdish movement, including: HEP (People’s Work Party, 1990–1993), DEP (Democracy Party, 1991/1993–1994), HADEP (People’s Democracy Party, 1994–2003), DEHAP (Democratic People’s Party established in 1997 but active only after HADEP was banned in 2003), DTP (Democratic Society Party, 2005–2009), BDP (Peace and Democracy Party, 2008–2014), DBP (Democratic Regions Party, 2014 –to date) and HDP (Peoples' Democratic Party, 2012-to date). While this limits the range of practices we attend to, it is justified by the numerical significance of this part of the Kurdish women’s movement. Nonetheless, some of the limitations of the mainstream Kurdish national movement, such as a conditional willingness to enter transversal politics with other Kurdish political parties, hierarchical structures and strict party discipline also characterise the Kurdish women’s movement (cf. Özgökçe Citation2011). More research on the diverse parts of the Kurdish women’s movement is needed for a fuller picture.

Multilayered intersectional citizenship: theoretically framing the Kurdish women’s movement

We conceptualize citizenship as a struggle for rights, representation, belonging and participation, where those social and political actors, challenging existing injustices are central to transforming exclusionary practices and conceptions of citizenship (Abraham et al. Citation2010; Erel Citation2016; Lister Citation2008). Furthermore, we draw on theoretical work on ‘acts of citizenship’, disrupting normative notions of who counts as a citizen and what constitutes legitimate rights, bringing about new understandings of the political, new subjects of citizenship and new forms of doing politics (Isin Citation2012). This is in contrast and opposition to how the Turkish state has defined citizenship closely based on national belonging; where Kurds, and other ethnic and religious others, have only been included on condition they assimilate while denying Kurdishness, victimising those refusing assimilation. Kurdish claims to ethnic identity have long been criminalized as undermining Turkish citizenship (Yeğen Citation2009).

We draw on Yuval-Davis’s (Citation1999) argument that citizenship is a multilayered construct:

in which one’s citizenship in collectivities in the different layers – local, ethnic, national, state, cross- or trans-state and supra-state – is affected and often at least partly constructed by the relationships and positionings of each layer in specific historical context. This is of particular importance if we want to examine citizenship in a gendered non-westocentric way (1999, 119).

Paying attention to the multilayeredness of citizenship challenges westocentric notions that the nation-state’s relationship to individuals determines the meaning of citizenship. Instead, participation, belonging, power relations and boundary-making in each layer are recognized as important aspects of citizenship. This is significant in non-Western contexts where the nation-state may be challenged both by traditional social structures, as well as multi-nationals, and international organizations. The notion of multilayered citizenship acknowledges that for those from minority national groupings, citizenship relates ‘as much to membership in their own community or the neighbouring nations as to the states where they live’ (Yuval-Davis Citation1999, 124). The state of struggle between the national minority and majority is key for understanding the citizenship of collectivities such as Kurds engaged in minority national projects (1999:127). A multilayered understanding also recognizes the role of transnational citizenship, which is relevant for the Kurdish context, where Diasporas were important in realizing cultural rights such as the standardization and teaching of Kurdish language to migrants in Sweden, or the development of Kurdish media in Belgium (Keles Citation2015). Diasporas also played an important role in gender equality struggles (Siqueira de Miranda Citation2015). Multilayered citizenship helps theorize the Kurdish women’s movement’s struggle for new forms of community beyond the nation-state, encompassing the Kurdish national community, not represented by a state, and also local multi-ethnic communities. In particular since the 2000s multi-ethnic and multi-cultural local autonomy and governance have become a focus of Kurdish politics, contradicting the Turkish nation-state’s claims to ethnic homogeneity. In addition, as a non-state nation spread across the territory of four nation-states, Kurds also have significant trans-border attachments and socio-political relationships (van Bruinessen Citation2000), e.g. the strong mutual influence of gender politics of Kurds in Turkey and Syria.

We combine Yuval-Davis’ concept of multilayered citizenship with her approach to situated intersectionality (2015) to theorize how different social divisions mutually constitute each other. The situated intersectionality perspective acknowledges the role of context and particular social and historical configurations to examine complex social relations, enabling comprehensive analysis of social inequalities: we explore unequal participation and belonging along the social divisions of gender, ethnicity, class, rural-urban origin, religious identity, though the focus is on gender and ethnicity, enabling analysis of inequalities within and between women. While

in concrete situations the different social divisions constitute each other, they are irreducible to each other – each of them has a different ontological discourse of particular dynamics of power relations of exclusion and/or exploitation, using a variety of legitimate and illegitimate technologies of inferiorizations, intimidations and sometimes actual violence to achieve this. (2015:94).

While gendered social divisions are defined ontologically through relations of sexuality and reproduction, ethnic social divisions are constructed by particular cultural boundaries (Yuval-Davis Citation2015). This approach acknowledges that particular social divisions, such as gender, ethnicity, class or education, can have different meanings in different spaces and contexts: the social position of ‘Kurdish woman’ can have conflicting meanings, such as in some Kurdish rights contexts, as guardian of Kurdish culture, or, from the perspective of Turkish state intervention as lacking education or cultural capital. A situated intersectional analysis is also attentive to the pluriversal epistemologies of ‘situated gazes of particular people in relation to their own social locations and social well-being’ (Yuval-Davis Citation2015, 97). The intersection of gender and ethnicity is an important arena of domination and resistance for national liberation movements. This situated intersectional approach has been chosen to analyse the multiple layers of belonging and participation constitutive of the citizenship practices of ethnically marginalized women; from the intimate sphere of the family, to the local, the national, transnational and the supra-national, different sites and relationships are involved in conferring – or withholding – recognition, rights and entitlements (Erel Citation2016). Yet, beyond formal notions of citizenship, we propose that ethnically marginalized women are not simply passive objects of states, communities or families, but contest forms of exclusion, struggle for participation and negotiate over who counts as a legitimate political subject. In these processes they become political subjects, despite and against their economic, cultural, and political gendered and ethnic marginalization and oppression (Erel Citation2013, Citation2016). As members of a marginalized ethnic minority, Kurdish women in Turkey experience a devaluation of their cultural resources, as their gendered experience of educational and economic deprivation does not equip them with the cultural capital that legitimises them as competent citizens. Furthermore, the hardships of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict have reified women’s already difficult access to the public sphere. For decades, state policy has rendered Kurdish women increasingly vulnerable to gendered ethnic violence, viewed their language as illegal - more recently, illegitimate - in public. As a consequence of the conflict, families have lost their livelihoods, many fleeing into cities in the Kurdish regions or other parts of Turkey and into the Diaspora (Keles Citation2015). The conflict and consequent economic deprivations have also made the reproductive tasks with which women have traditionally been charged, more difficult to fulfil (IFWF Citation2007). In the following we explore how the Kurdish women’s movement produced new forms of intersectional multilayered citizenship for Kurdish women.

Women’s representation in formal politics

The intensified political and military conflict of the 1990s affected the everyday lives of Kurdish women in a myriad of ways. The repressions of that period had a contradictory effect, on one hand criminalising and rendering high-risk any form of pro-Kurdish rights political activism, on the other, contributing to a mass politicisation of women personally affected (Bozgan Citation2011). During the 1990s and 2000s pro-Kurdish rights parties were regularly criminalised, and closed down, however Kurdish activists quickly responded by establishing new successor political parties. We argue that each time a new party was formed, women activists used this to institutionalize more far-reaching gender equality policies. In the early 2000s, when the political climate in Turkey allowed for an expansion of civil society organizations, the Kurdish women’s movement entered a new stage. Kurdish women's organizations were able to operate legally and became part of an expanding representation of pro-Kurdish rights parties in local and national government.

The grassroots mobilisation of the pro-Kurdish rights parties was to a great extent carried out by women activists. They initially formed informal ‘women’s commissions’, which subsequently became women’s branches of the pro-Kurdish rights parties. At the November 2000 HADEP party conference, the women’s branches established autonomous structures within the party and introduced “positive support” measures to improve women’s representation in formal politics. Discursively, emphasis shifted from the 1990s framing of “women’s rights” to “gender inequality” as exemplified by the DEHAP (Citation2003) party programme which defined gender inequality as a key concern of contemporary societies, making its elimination a key party objective with equal priority to the solution of the Kurdish issues.

As pro-Kurdish parties’ representation in the Turkish parliament increased and many municipalities and local and regional governments in the Kurdish areas are run by them, the gender composition of politics in Turkey has changed (cf. Güneş Citation2012, Çağlayan Citation2006). Their multilayered citizenship activism has changed the relationship between Kurdish women and the Turkish state, where they have claimed recognition as ethnically distinctive political subjects. However, this activism has also changed Kurdish women’s citizenship with respect to establishing the Kurdish women’s movement as an important political actor within the Kurdish national movement (cf. Çağlayan Citation2007). As a consequence, they have been able to consolidate recognition of injustice of women’s oppression within the level of the kin group and family as well. This shows how Kurdish women’s citizenship is ‘affected and (…) at least partly constructed by the relationships and positionings of each layer in specific historical context.’ (Yuval-Davis Citation1999, 94). From an intersectional perspective this also shows how women’s highly visible involvement in claiming ethnic rights vis-à-vis the state, has strengthened their ability to realize their gendered rights vis-à-vis the Kurdish community, on the level of formal politics, within the local community and the family. In the following we explore in-depth three rights-claiming activities significant for developing Kurdish women’s intersectional, multilayered citizenship acts; autonomous women’s assemblies, a woman’s quota and the co-chair system.

Autonomous women’s assemblies

Women’s informal activism in the early 1990s became more institutionalized through women’s assemblies with a nested structure from village or neighbourhood, town, region, to national level. Membership of women’s assemblies is open to all women. They work bottom-up, with neighbourhoods electing representatives to the district who in turn elect representatives to regional women’s assemblies. Representatives from regional women’s assemblies meet annually at the nationwide women’s conference. The effectiveness of these women’s assemblies can be understood through a framework of intersectional multilayered citizenship.

The neighbourhood women’s assemblies work independently from the regional assemblies, responding to local issues and events, for example, this might be to intervene in a domestic violence case by suspending the male perpetrator from the party. The district and regional women’s assemblies cannot intervene into local work, but the neighbourhood women’s assembly can call upon them to support their work e.g. through setting up a special commission.

A solution oriented commission, a mediating commission. There will be members of the women’s assembly on the commission, but depending on the circumstances, there may be a specialist lawyer, or a psychologist (…) that commission will carry out its work and report back to the regional women’s assembly. But the neighbourhood women’s assembly will be the one to address the problem. (Avşȋn)

This responsiveness to local issues characterises the enacting of citizenship as embedded in multiple layers of the family, the local community, the Kurdish national movement and also their relationship with the Turkish state, so that the nested structure of women’s assemblies has become an effective vehicle for Kurdish women’s citizenship. Women’s assemblies have helped to bring personal relations, such as within the family, to a public arena where they can be challenged politically. This challenged the boundaries of public and private, thereby enacting citizenship; they challenged gendered allocation of women’s experiences of oppression within the family as ‘non-political’ by posing the problem of domestic violence as a public question of oppression, challenging a narrow conception of what counts as political and where women’s citizenship is expressed. The women’s assemblies constitute an important resource for women to address gender based violence and gender-specific concerns in the locality. It has also affected the conduct of politics in mixed-gender Kurdish organizations and pro-Kurdish rights parties. A striking point demonstrating the strength of women’s assemblies within the pro-Kurdish parties is that decisions taken at meetings and committees in which women were not present, are not binding for women, to ensure that women are involved in all key decision-making, while decisions taken by women’s assemblies cannot be reversed by mixed-gender political structures (see for example: https://bdpblog.wordpress.com/kadin-meclisi). This far-reaching autonomy has helped address gender discriminatory practices and allowed women’s assemblies to negotiate political outcomes to their own advantage. An intersectional multilayered citizenship analysis highlights how the strengthening of Kurdish women’s citizenship on the local level of participation in women’s assemblies enabled them to participate more effectively in mixed-gender political fora by giving women representatives effective decision-making power within these. The multilayered nature of the nested women’s assemblies (local, regional, national) constitutes a communication channel between local grassroots women activists and their regional and national representation, providing a feedback-loop and accountability between these layers of citizenship.

The women’s quota

A woman’s quota for elected positions within the party was first introduced in 2000 during the HADEP era, at 25%. While initially its implementation was not very sucessful, quotas were reinscribed into succeeding pro-Kurdish political parties’ programmes and the women’s quota increased with each re-grouping; reaching 35% during the DEHAP period (2003–2005), 40% during the Democratic Society Party (DTP) period (2005–2009), increasing to 50% in 2011 when the BDP formed an electoral block with left wing groups. The women argued that the quota was needed to allow women to participate in decision-making bodies, to reflect the level of their grassroots activism: ‘The women have won this right…. because women are fighting on their own behalf’ (Dȋlan). Initially, this policy encountered scepticism from some male party members and activists who argued that, there were ‘not enough qualified female candidates’ (Avşȋn). It was also suggested that especially in socially conservative places, the electorate would not support female candidates. Yet, after gaining seats in parliament the new female MPs became popular for their careful accountability to local electorates, legitimising the fielding of female candidates in subsequent elections.

It was not until the 2007 general elections that the quota’s full effects became evident as the pro-Kurdish rights party gained more seats. Eight of the 21 (38%) pro-Kurdish DTP MPs were women. This was a significant achievement as the overall female representation in the parliament of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) was only 9% (Çağlayan Citation2013).

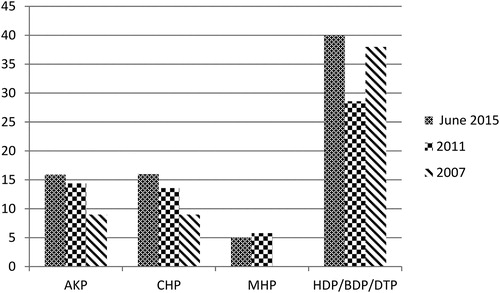

shows that all parties increased their share of female MPs in the last three national elections. Yet, the pro-Kurdish parties HDP/BDP/DTP had by far the highest representation of female MPs reaching 40% in the June 2015 elections. Out of 550 MPs, 96 were women, 31 of which were from the pro-Kurdish rights HDP (Nardelli Citation2015).

Figure 1. Percentage of elected women parliamentarians by party in general elections 2007, 2011, 2015. Source: Kadɪn Adaylarɪ Destekleme Derneği, KA.DER İstatistikleri. AKP (Justice and Development Party), CHP (Republican People’s Party), MHP (Nationalist Movement Party), HDP (Peoples' Democratic Party 2015), BDP (Peace and Democracy Party, 2011), DTP (Democratic Society Party, 2009).

Similar trends can be observed for the local elections; in 2009, out of 98 elected pro-Kurdish rights DTP mayors, 14 were women (13.7%). Although, much lower than the female representation among the party’s MPs, this proportion is much higher than the national average of female mayors, which in 2009 was 0.9% (i.e. only 27 out of 2,948 mayors were female, of which almost half were from the DTP) (Çağlayan Citation2013). In the local elections in March 2014 the number of women mayors and councillors peaked at 37, of whom 23 (60%) were from the pro-Kurdish rights BDP (KA.DER).

While the first women MPs for the pro-Kurdish rights parties tended to be affiliated with well-known male political dissidents’ cases (Çağlayan Citation2007), they increasingly represented a wider range of social and political backgrounds. In 2011 the elected women MPs, ranged from MPs with a farming background, to lawyers. This is an instance, where an intersectional analysis reveals the importance of gendered political participation in relation to other social divisions, such as class, educational background and the rural-urban divide. By widening the range of women in parliament, the pro-Kurdish rights parties have been able to extend their reach and credibility, contrasting with earlier periods, where mainly young educated Kurdish women were able to participate in the national movement.

As a result of the 50% quota and pro-Kurdish parties’ electoral gains, the number of women in formal politics increased considerably and the cohort of female candidates for the June 2015 elections continued to show this diversity, since among the HDP’s 550 candidates 268 were women, resulting in 31 (39%) of its 80 elected MPs being female (Lyons Citation2015). The HDP female candidates were more diverse in terms of age, political, social, ethnic, and religious backgrounds. As the HDP explicitly fosters collaboration between Turkish left-wing, feminist, pro-democracy and pro-Kurdish rights activists, the candidates encompassed Turkish feminists as well as MPs who wear a headscarf and are arguably from a more socially conservative Muslim milieu.

The increasing visibility of women in formal politics strengthened women’s confidence not only in their ability to act politically, but also to raise women’s rights as legitimate subjects of politics:

Well, if someone else makes decisions about you, whoever it may be, they may be your comrades, they may protect your rights, they may think of your best interests,…. But when … you are able to express your own demands that gives great confidence. … I have been to parliament frequently, … the women express a different joy, and enthusiasm when [a female] leader speaks…she sees herself there, she says ‘I am here’. That has made women more active, … more politically involved …. ‘I can do this’. (Dȋlan).

Seeing women parliamentarians in action has drawn the attention of pro-Kurdish rights activists, but also those affiliated with other or no political parties:

My [female] neighbour…. was a supporter of the CHP, however when she saw MP Gultan Kisanak’s talk on Uludere [the Roboski massacre on 28 December 2011 when Turkish military aircraft killed 34 civilians] in parliament…. she said “I admire the HDP women, both the neighbourhood activists and the MPs … because as a CHP supporter I haven’t seen a woman MP stand up and talk with so much courage” (Lorȋn).

The entry of Kurdish women politicians into parliament and local governments challenged gendered ethnic stereotypes about Kurdish women. While public opinion routinely questioned the suitability and capacity of women politicians from all parties, for Kurdish women, this has been exacerbated. Due to gendered effects of the Kurdish conflict and longterm underdevelopment of Kurdish regions, Kurdish women are the group with the highest level of illiteracy (Yüksel Citation2006). Widely circulated gendered and racist stereotypes cast them as more backward, marginalized and limited to family concerns, rather than legitimate participants in public deliberation. These representations devalued Kurdish women’s ability to act politically and take public office, questioning whether they could ‘speak publicly? What could [a Kurdish woman] possibly say beyond the Kurdish issue?’ Despite these assumptions, Kurdish women politicians developed a distinct style of doing politics. When becoming MPs, women voiced feminist demands in parliament, giving these issues a wider audience:

Law proposals about violence against women were made. Many law proposals were made to bring about the opportunity for women to become subjects of politics. But beyond this, women MPs raised issues around refugee women, fighting AIDS, seasonal workers and many other problems. (Avşȋn)

When women MPs raised topics beyond narrowly conceived notions of ‘Kurdish women’s issues’, they furthermore enacted citizenship by bringing about a new understanding of what can properly be treated as a subject of politics. For example, a motion condemning the murders of trans-women, put forward by an MP of ‘tribal background’, contributed to constituting new subjects of rights and a widening of what can be conceived as political within the arena of formal politics. It furthermore challenged the idea that, as Kurdish women, these MPs would be either too traditional to address issues such as sexuality or violence against trans people or too bound up in narrowly conceived identity politics. A situated intersectional analysis demonstrates how Kurdish women from a range of social locations of class, rural-urban divisions, and educational hierarchies, were able to challenge the gendered, ethnic stereotypes of Kurdish women as unsuitable subjects of formal politics. By raising a wide range of political issues, they also challenged the idea that, as ethnically and gender oppressed political subjects their remit was limited to only those issues. As Yuval-Davis (Citation2015, 94) points out, such an idea is based on the normalisation of a ‘hegemonic masculinist ‘positivistic’ positioning.’ Instead, while acknowledging that Kurdish women’s knowledge and political imagination is situated in their social positionings, it is important to analytically differentiate between three aspects; their positionings along socio-economic grids of power; their identifications, and their normative value systems. While these are related to each other, normative value systems cannot be automatically read off social positionings or identifications.

The entry of female pro-Kurdish rights MPs to parliament in sizeable numbers, became a lever for other women MPs to negotiate increased female representation in their political parties (cf. Çelik Citation2014). Within the parliamentary all-party ‘Women and Men Equality Commission’ (KEFEK), many women MPs of other political parties welcomed the impetus of the pro-Kurdish rights parties’ women’s policies. This illustrates the significance of an intersectional multilayered citizenship analysis: Initially, Kurdish women enacted their citizenship by gaining recognition as capable of entering formal politics against the resistance firstly of the Kurdish national movement, challenging the intersection of ethnic, gendered and rural-urban as well as class stereotypes that Kurdish women are too traditional. This enacted their rights vis-à-vis the Kurdish ethnic community. Consequently, however, their entrance to the formal political arena also affected the layer of women’s citizenship vis-à-vis the Turkish state. This, in turn, gave impetus to women’s greater visibility and participation in parliament more generally, affecting also Turkish women. In this sense, the enactment of citizenship on the layer of Kurdish community affected that in the layer of citizenship of the nation-state.

The woman’s quota has significantly encouraged other political parties to improve women’s representation. Among the major political parties only the CHP has included a woman’s quota in their party programme, increasing it to 33% in 2012. The ruling AKP, while recognising that the party’ success owes much to their female grassroots activists, in the run up to the 2015 elections rejected a woman’s quota as discriminatory (Elçik Citation2015). By increasing the representation of women in parliament and local government, the quota for women in pro-Kurdish rights parties has become an important instrument to strengthen Kurdish women’s capacity to enact citizenship. As parliamentarians and local government politicians, Kurdish women have become subjects with political agency, contradicting the stereotyping of Kurdish women as limited to the familial realm. They have introduced new topics to the arena of formal politics, and thereby enacted new subjects of what and who can count as legitimately political in the public sphere. In their legislative work, they have furthermore claimed rights for subjects which had not been hitherto recognised.

The co-chair system

In 2006 the pro-Kurdish rights party DTP for the first time implemented a policy of appointing two chairs to the party, representing men and women, with equal responsibilities (Tuğluk Citation2006). The introduction of a co-chair system aimed at creating a more gender equal, but also more cooperative, less hierarchical political culture (Çelik Citation2014; Tuğluk Citation2006). Drawing on the German Green Party’s example who elect a male and female co-chair to the national party leadership, the women’s movement campaigned to introduce the co-chair system first at national, subsequently at all levels of the pro-Kurdish rights party. When initially the co-chair system was ruled illegal, then DTP co-chair Aysel Tuğluk officially stood down in 2007. However, informally the party continued to practice the co-chair system and widened it to all levels of leadership. While the co-chair system has now been ruled legal for political parties as part of the ‘Democratisation Package’ in 2013 (İçişler Bakanlığı Citation2013), it is not legally recognised within local government or civil society organizations. A formal proposal to amend existing laws to recognise the co-chair system put forward by Sebahat Tuncel MP in 2013, argues that it can improve gendered representation at local and regional government levels which address environmental, transport, health services, of particular relevance to women, emphasising that ‘there is no other country practicing the co-chair system at local government level. In that sense, Turkey has the opportunity to introduce a change of global significance’ (Tuncel Citation2013).

In the March 2014 local elections the co-chair system was applied systematically, so that of the 101 elected pro-Kurdish rights BDP mayors and councillors of provinces, districts, and sub-districts, 98 had a co-chair in place. While lacking legal recognition the co-chair system is being applied despite and, to an extent, against the state, while satisfying the requirements of legality, politicians and local governments strive to strengthen their gendered politics. Ground rules for its implementation had to be agreed within the pro-Kurdish rights party, so that co-chairs currently hold the official position of being elected as councillors or mayors and are therefore members of the city council. While it is party policy and practice that both co-chairs have to agree on decisions, legally the elected mayor or councillor’s signature of remains binding. The pro-Kurdish rights parties underlined that co-chairs should not be confused with assistant or deputy-chair, and since 2014, it has been established practice that the official salaries of the mayor and the councillors are equally split between both co-chairs (İlkehaber Citation2014). Analysed through an intersectional multilayered citizenship approach, the practice of co-chairs shows a commitment to increasing women’s participation in leadership positions at all layers of citizenship and in a range of political structures. It also demonstrates the tensions between different layers of citizenship; while the co-chair system has been established within the Kurdish national movement, including in political parties, as well as other political organizations, it has met with resistance at the layers of the state which has not recognised co-chairs as legitimate within the realm of local government or civil society organizations. A fuller analysis of the limitations of Kurdish women’s politics through the tension between identity and recognition is beyond the scope of this article, nevertheless this contradiction between the national and local layers of citizenship exemplifies the issue to some extent. It is clearest in the way that co-mayors at local government level had to find an informal way of splitting salaries, and are not able to sign legally binding documents, which are regulated by the national state. This discrepancy between local government, Kurdish community and the nation-state is a case in point that the enacting of Kurdish women’s citizenship rights is subject to struggles between political actors at these multiple layers of citizenship. By claiming that the enactment of a co-chair system would constitute an opportunity for the Turkish nation-state to set a global example, Sebahat Tuncel MP strives to influence the national level of citizenship through invoking a supra-national community of governance.

As the co-chair system is so far a unique policy, local governments and pro-Kurdish parties addressed problems as and when they encountered them, refining the application of the co-chair system in the process. Thus, it was decided that co-chairs should share an office wherever physically possible:

The [established political] system leans towards according leadership to males. (…) For example, in the regional government buildings… we experienced many problems. The larger office was given to the male and the smaller office to the female co-chair. And naturally that led to the fact that all visitors to the office were brought to the male co-chair’s office and that this oriented the centre towards the male co-chair’s office. When the women noticed this, we immediately intervened and said that it needs to be one office with two desks opposite of each other. (Avşȋn)

After the March 2014 local elections, the Turkish mainstream press acknowledged that the co-chair system encouraged women to engage with formal politics. For example, co-mayor Berivan Elif Kılıç of Kocaköy, Diyarbakir, argued that women were encouraged to approach local institutions (Tabu and Ceylan Citation2014), while Hatice Çoban, co-mayor of Van, highlighted ‘greater feelings of trust and cooperation’ (Çiftçi Citation2014).

Yet this had not always been the case. The extent to which the co-chair system challenged deep-seated gendered expectations is palpable in the initial confusion among parts of the electorate, who associated masculinity with the ‘somatic norm’ (Puwar Citation2004) of politicians:

The people were used to the male ego, the male norm. When all of a sudden they saw women in the status of chair, people with a feudal culture began to be puzzled. I am talking of the early times, nowadays there is no such thing. For example … a female candidate co-chair to the local government told me “We were visiting villages, and they thought I am the wife of my co-chair … we didn’t have time to do our election campaign as it took up all our time to explain the co-chair system. (Dȋlan).

The challenges of explaining the co-chair system during election campaigns elucidate the necessitaty of understanding politics intersectionally: while campaigning for general elections, the pro-Kurdish rights party instead had to validate their commitment to gender equality by explaining this policy to their potential electorate.

The co-chair system impacted beyond the Kurdish movement, as progressive organizations such as the education trade union Eğitim Sen and the public service trade union KESK have also introduced it (Evrensel Citation2014) and other civil society organizations are considering its implementation. However, the system is only legally recognised with respect to political parties, so that the co-chair system’s widening implementation in civil society organizations indicates the Kurdish women’s movement’s influence on changing normative understandings of justice and participation despite the state. Through the co-chair system Kurdish women enact citizenship, bringing into being new forms of doing politics. This requires engagement with the micropolitics of who is seen as legitimately embodying a political representative; challenging automatic alignment of leadership with male bodies; and facilitating increased participation of women in formal party-politics. The blurring of boundaries between formal and informal politics meant women claimed more representation in formal party politics, and articulated their concerns as legitimate topics of politics. An intersectional, multilayered analysis of the co-chair system shows the Kurdish women’s movement’s achievemement of institutionalizing the increased participation of women in leadership positions on all levels of citizenship. The tension between the realization of the co-chair system in the Kurdish national movement and the Turkish nation-state which does not accept it as legally binding, is a case in point that Kurdish women’s rights-claiming highlights contradictions between different levels of citzenship. Nonetheless, the co-chair system’s effect on other civil society organizations, shows how different layers of citizenship mutually influence each other, by establishing new standards of gender justice.

Conclusion

Through the three-fold measures of women’s assemblies, quotas and the original development of a co-chair system, the Kurdish women’s movement has challenged established gender roles in politics and society, creating a new understanding of Kurdish women as political subjects capable of leadership and strengthening the voice of the Kurdish women’s movement within the national movement. This emergent political culture of gender equality, is setting new standards of women’s representation in grassroots and formal politics in Turkey more widely. Yet, the Kurdish question in Turkey remains unresolved posing a key obstacle to democracy, including gender rights.

The Kurdish women’s movement has developed primarily within a wider national movement involved in challenging the Turkish state’s policies towards the Kurds, and is highly critical of Turkish state institutions more generally. This raises awareness of intersecting social power relations beyond gender. The Kurdish women’s movement highlights and challenges the oppressions and inequalities around ethnic identity and class, as they affect women and men. It has transformed existing modes and forms of citizenship on multiple layers, within the family and the neighbourhood scandalizing issues such as violence against women, domestic violence and intra-familial power relations. It has also struggled against ethno-national oppression through its involvement as grassroots activists, guerrilla fighters and key organizers of a mass movement. By claiming decision-making positions, and legitimising the focus on gender inequality and women’s rights, it has transformed understandings of justice and freedom within the Kurdish national movement. The three key measures of women’s assemblies, quotas and the co-chair system effectively transformed and co-constituted the Kurdish national movement into one where gender inequality has been recognized as a key dimension of social and ethno-national oppression. Yet, the close connection of the Kurdish women’s movement with Kurdish national politics has also had consequences that have limited their effectiveness, as they are part of a hierarchical party structure, which can also circumscribe women’s choices. Women’s role as transmitters of Kurdish language and culture is celebrated, often foregrounding their role as mothers nurturing their community (cf. DÖÇ Citation2015). Whilst such roles for women differ from traditional gender roles, at the same time, the Kurdish national movement defines new versions – and potentially limits – of proper femininity, circumscribing women’s ability to reach their full potential as multifaceted complex human beings, an issue critiqued by Kurdish feminists not affiliated with the Kurdish national movement (e.g. Çağlayan Citation2012).

Kurdish women’s activism has co-created the Kurdish national movement, establishing institutions and forms of doing politics anchoring a consciousness that gender equality and women’s issues are intimately connected to democratic ethnic and civil rights. In this sense, the Kurdish women’s movement has contributed a gendered vision to an intersectional multilayered politics of democratising citizenship. Notwithstanding problematic aspects mentioned above, the Kurdish women’s movement also testifies to the importance of gender equality struggles from the global South, their experiences, knowledges and achievements, challenging simplified dichotomies of West versus Middle East, and the assumption that it is religious identities rather than complex socio-political factors which affect gender politics.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our interview partners for sharing their important insights, and Jessica Jacobs, Janroj Yilmaz Keles, Leah Bassel, Ulrike Fladder and the anonymous referees for very helpful comments which have helped to strengthen the paper. The article was written while holding ESRC/IAA grant 1710-KEA-322.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Dr. Umut Erel is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the Open University, UK. Her research interests are in gender, migration, racism, citizenship and participatory creative methods.

Dr Necla Acik is a Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Centre for Criminology and Criminal Justice (CCCJ), School of Law, University of Manchester. Her research interests are in counter-terrorism, youth studies, migration, ethnic inequalities and the Kurdish women’s movement.

References

- Abraham, Margaret, Esther Ngan-Ling Chow, Laura Maratou-Alipranti, and Evangelia Tastsoglou. 2010. “Rethinking Citizenship with Women in Focus.” In Contours of citizenship: Women, Diversity and Practices of Citizenship, edited by Laura Maratou-Alipranti, Esther Ngan-ling Chow, Evangelia Tastsoglou, Margaret Abraham, 1–22. Oxon: Ashgate.

- Açık, Necla. 2013. “Re-defining the Role of Women within the Kurdish National Movement in Turkey in the 1990s.” In The Kurdish Question in Turkey: New Perspectives on Conflict, Representation and Reconciliation, edited by Welat Zeydanlıoğlu and Cengiz Güneş, 114–136. London: Routledge.

- Açık, Necla. 2003. “Die Kurdische Frauenbewegung in der Türkei.” In Kurden heute: Hintergründe, aspekte und entwicklungen, NAVEND-Zentrum für Kurdische Studien e.V. Navend Schriftenreihe Bd. 13, 131–152. Bonn: Navend.

- Akkaya, Ahmet H., and Joost Jongerden. 2014. “Reassembling the Political: The PKK and the Project of Radical Democracy.” European Journal of Turkish Studies 12: 2–16.

- Al-Ali, Nadje, and Nicola Pratt. 2011. “Between Nationalism and Women’s Rights: The Kurdish Women’s Movement in Iraq.” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 4: 337–353.

- Ayata, Bilgin, and Serra Hakyemez. 2013. “The AKP’s Engagement with Turkey’s past Crimes: An Analysis of PM Erdoğan’s ‘Dersim Apology.” Dialectical Anthropology 37 (1): 131–143. doi:10.1007/s10624-013-9304-3.

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.”Qualitative Research Journal 9(2): 27–40. doi:10.3316/QRJ0902027.

- Bozgan, Özgen D. 2011. “Kürt Kadın Hareketi Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme.” In Birkaç arpa boyu… 21. Yüzyıla girerken türkiye'de feminist çalışmalar. Prof. Dr. Nermin abadan unat'a armağan., edited by Serpil Sancar, 757–799. İstanbul: Koç Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Çağlayan, Handan. 2013. Kürt kadınların penceresinden: Resmi kimlik politikaları, milliyetçilik, barış mücadelesi. İstanbul: İletişim.

- Çağlayan, Handan. 2012. “From Kawa the Blacksmith to Ishtar the Goddess: Gender Constructions in the Ideological-Political Discourses of the Kurdish Movement in Post-1980.” Turkey. European Journal of Turkish Studies 14: 2–23.

- Çağlayan, Handan. 2007. Analar, yoldaşlar, tanrıçalar; kürt hareketinde kadınlar Ve kadın kimliğinin oluşumu. İstanbul: İletişim.

- Çağlayan, Handan. 2006. HEPten DEHAPa Pozitif Ayrımcılık. Bianet, Nisan 3. https://m.bianet.org/bianet/kadin/77078-hepten-dehapa-pozitif-ayrimcilik

- Çelik, Ayşe Betül. 2014. “A Holistic Approach to Violence: Women Parliamentarians' Understanding of Violence against Women and Violence in the Kurdish Issue in Turkey.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 23: 76–92.

- Çelik, Betül. 2014. BDP'de Eşbaşkanlık Nasıl Uygulanacak? Al Jazeera, Nisan 8. http://www.aljazeera.com.tr/al-jazeera-ozel/bdpde-esbaskanlik-nasil-uygulanacak

- Çiftçi, Hicret. 2014. Eşbaşkanlık Bir Devrimdir. Özgür Gündem, Nisan 4. http://www.ozgur-gundem.com/index.php?haberID=103015&haberBaslik=Eşbaşkanlık%20bir%20devrimdi&categoryName=Kadın&categoryID=9&authorName=Hicret%20%20ÇİFTÇİ&authorID=486&action=haber_detay&module=nuce

- DEHAP 2003. Demokratik Halk Partisi: Program ve Tüzük. Accessed 25 November 2015. www.tbmm.gov.uk. https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/eyayin/GAZETELER/WEB/KUTUPHANEDE%20BULUNAN%20DIJITAL%20KAYNAKLAR/KITAPLAR/SIYASI%20PARTI%20YAYINLARI/200707309%20DEHAP%20PROGRAM%20VE%20TUZUK%202003/200707309%20DEHAP%20PROGRAM%20VE%20TUZUK%202003.pdf

- DÖKH and DWAA (Diyarbakir Women’s Academy Association). 2013. Gyneology. Diyarbakir: In house publication.

- DÖÇ (Demokratik Özerklik Çaliştayi). 2015. DÖÇ – Demokratik Özerklikte Kadın. 12 Ağustos. Accessed 01 November 2018. http://www.kcd-dtk.org/doc-demokratik-ozerklikte-kadin.html/

- ECRI. 2011. ECRI Report on Turkey (Fourth Monitoring Cycle). European Commission against Racism and Intolerance. Strasbourg. Accessed 01 November 2018. http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/ecri/Country-by-country/Turkey/TUR-CBC-IV-2011-005-ENG.pdf

- Erel, Umut. 2013. “Kurdish Migrant Mothers in London Enacting Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 17 (8): 970–984. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.851146.

- Erel, Umut. 2016. Migrant Women Transforming Citizenship: Life-stories from Britain and Germany. London: Routledge.

- Esfandari, Haleh. 2012. “Are Women the Losers of the Arab Spring?” In Women after the Arab Awakening. Middle East Program Occasional Paper Series, 5–7. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson. Accessed 12 September 2018. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/women_after_the_arab_awakening_0.pdf

- Elçik, Gülnur. 2015. Seçim Beyannamelerindeki Cinsiyet Eşitliği Yapısal Dönüşüm Mü "Etkinlik" Mi? Bianet, 05 Mayıs. http://bianet.org/bianet/siyaset/164226-secim-beyannamelerindeki-cinsiyet-esitligi-yapisal-donusum-mu-etkinlik-mi

- Evrensel. 2014. KESK'te Eş Başkanlık Dönemi. 06 Temmuz. https://www.evrensel.net/haber/87728/keskte-es-baskanlik-donemi

- Farris, Sara R. 2017. In the name of women’s rights: the rise of femonationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Encarnacion. 2010. Migration, Domestic Work and Affect: A Decolonial Approach on Value and the Feminization of Labour. New York: Routledge.

- Güneş, Cengiz. 2012. The Kurdish National Movement in Turkey: From Protest to Resistance. London: Routledge.

- Hammersley, Martyn. 2010. “A Historical and Comparative Note on the Relationship between Analytic Induction and Grounded Theorising [22 Paragraphs].”Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 11 (2). http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100243.

- Hatem, Mervat. 1994. “The Paradoxes of State Feminism.” In Women and Politics Worldwide, edited by Barbara. J. Nelson and Najma Chowdhury, 226–242. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- International Free Women’s Foundation (IFWF). 2007. Psychological consequences of trauma experiences on the development of Kurdish migrant women in the European Union: Final results and background of a survey in five European countries and Turkey. Rotterdam: Aletta.

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- İlkehaber. 2014. BDP'li Başkanlar Maaşı Paylaşacak. Nisan 3. http://www.ilkehaber.com/haber/bdpli-baskanlar-maasi-paylasacak-29214.htm

- Isin, Engin. 2012. Citizens without frontiers. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- KA.DER. 2015. Kadɪn Adaylarɪ Destekleme Derneği, KA.DER İstatistikleri. Accessed 15 October 2015. http://www.ka-der.org.tr/tr-TR/Page/Show/400/kader-istatistikleri.html

- Keles, Janroj Yilmaz. 2015. Media, diaspora and conflict: Nationalism and identity amongst kurdish and turkish migrants in Europe. London: I. B.Tauris.

- Kandiyoti, Deniz. 1989. “Women and the Turkish State: Political Actors or Symbolic Pawns.” In Woman-Nation-State, edited by Nira Yuval-Davis and Floya Anthias, 126–149. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lister, Ruth. 2008. “Inclusive Citizenship: Realizing the Potential.” In Citizenship Between Past and Future, edited by Engin Isin, Peter Nyers, Bryan Turner, 48–60. London: Routledge.

- Lyons, Kate. 2015. “Record Number of Women Elected to Turkish Parliament.” The Guardian, June 8.

- McDowall, David. 2007. A modern History of the Kurds. London: I.B. Tauris

- Mignolo, Walter. 2012. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Borderthinking. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Mojab, Shahrzad. 2001. Women of a Non-State Nation: The Kurds. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda.

- Nardelli, Alberto. 2015. “Turkey election results: what you need to know.” The Guardian, June 8.

- Öcalan, Abdullah. 2013. Liberating Life: Woman’s Revolution. International initiative edition. Cologne: Mesopotamian Publishers.

- Outshoorn, Joyce. 1994. “Between Movement and Governance: Femocrats in the Netherlands.” In Yearbook of Swiss Political Science, edited by H. Kriesi, 141–165. Bern: Paul Haupt Verlag.

- Özgökçe, Zozan. 2011. “Önderliğin Feminizimle İmtihanı.” Qijika Reş, Mayıs-Haziran: 40-43. http://www.arsivakurd.org/images/arsiva_kurd/kovar/qijika_res/qijika_res_04.pdf

- Puwar, Nirmal. 2004. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies out of Place. Oxford: Berg.

- Popular Memory Group. 1982. “Popular Memory: Theory, Politics, Method.” In Making Histories: Studies in History-Writing and Politics, edited by R. Johnson, G. McLennan, B. Schwarz, and D. Sutton, 205–252. London: Hutchinson.

- Siqueira de Miranda, Sarah. 2015. “Women, Life, Freedom: The Struggle of Kurdish Women to Promote Human Rights.” MA diss. London: University of London. Accessed 12 October 2018. http://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6284/7/DISSERTATION%20SARAH%20MIRANDA%20-%20UPDATED%20VERSION.pdf

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Desmond Fernandes. 2008. “Kurds in Turkey and in (Iraqi) Kurdistan: A Comparison of Kurdish Educational Language Policy in Two Situations of Occupation.” Genocide Studies and Prevention 3 (1): 43–73. doi:10.3138/gsp.3.1.43.

- Tabu, Mizgin, and Derya Ceylan. 2014. Belediyelerde Kadın Sayısı Artmalı. Özgür Gündem, 12 Nisan. http://www.ozgur-gundem.com/haber/103900/belediyelerde-kadin-sayisi-artmali

- Tank, Pinar. 2017. “Kurdish Women in Rojava: From Resistance to Reconstruction.” Die Welt Des Islams 57 (3–4): 404–428. doi:10.1163/15700607-05734p07.

- İçişler Bakanlığı, T. C. 2013. Demokratikleşme Paketi. Başbakanlık Kamu Duzeni ve Guvenliği Musteşarlığı, Eylül 30. http://www.kdgm.gov.tr

- Tuğluk, Aysel. 2006. Bir Pozitif Ayrımcılık Örneği: Eşbaşkanlık. Bianet, Nisan 7, http://bianet.org/bianet/kadin/77385-bir-pozitif-ayrimcilik-ornegi-esbaskanlik,

- Tuncel, Sebahat. 2013. Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi Başkanlığına Şunuş, Kasım 4, https://www2.tbmm.gov.tr/d24/2/2-1828.pdf, (accessed 20.10.2015)

- van Bruinessen, Martin. 2000. Transnational Aspects of the Kurdish Question. Working Paper. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. European University Institute: Florence.

- Zeydanlıoğlu, Welat. 2008. “The White Turkish Man’s Burden: Orientalism, Kemalism and the Kurds in Turkey.” In Neo-colonial Mentalities in Contemporary Europe? Language and Discourse in the Construction of Identities, edited by G. Rings and A. Ife, 155–174. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Yeğen, Mesut. 2009. “Prospective-Turks’ or ‘Pseudo-Citizens’: Kurds in Turkey.” Middle East Journal 63 (4): 597–615.

- Yüksel, Metin. 2006. “The Encounter of Kurdish Women with Nationalism in Turkey.”Middle Eastern Studies 42 (5): 777–802. doi:10.1080/00263200600828022.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 1999. “The 'Multilayered Citizen.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 1 (1): 119–136. doi:10.1080/146167499360068.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2015. “Situated Intersectionality and Social Inequality.” Raisons Politiques 2: 91–100. doi:10.3917/rai.058.0091.