Abstract

As a way to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist geography, the journal sought to highlight the status of feminist geography across the globe. This special issue gives an overview of feminist geography as a praxis and an intellectual field across 39 countries. This process has highlighted the contemporary nature of feminist geographical knowledge construction across multiple scales and diverse contexts. What is evident is that with feminist geography spreading beyond Anglo-American countries, what and who defines the field has drastically changed. We suggest that this means paying much closer attention to the unequal plains of knowledge construction while engaging with transnational dialogue that fosters networks of solidarity. The plurality of feminist geographies that exist today enriches the field in ways that are just becoming apparent, we hope that this special issue will contribute to a fruitful and ongoing discussion towards this aim.

An unequally represented world

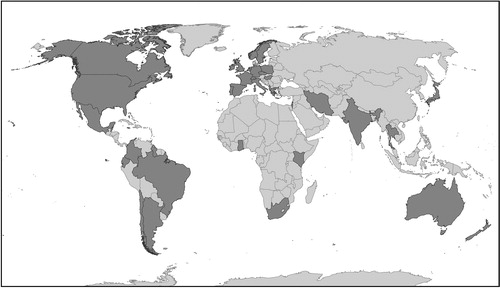

The map below indicates the countries examined by the authors included in this special issue celebrating the 25th anniversary of the journal Gender, Place and Culture (). The issue gives an overview of the breadth and diversity of feminist geography and the geography of gender around the world, though it is in no way exhaustive. Thirty years after the special issue of the Journal of Geography in Higher Education entitled ‘The challenge of feminist geography’ (Peake Citation1989), this issue offers an unprecedented panorama, with a total of 39 contributions from Asia (8), Africa (3), Europe (16), North America (3), Oceania (2), and South America and the Caribbean (7). The map of the countries examined reveals the shifting boundaries of a vast community who, despite the inequality and difficulty of access to legitimate, valued intellectual resources such as journals, colloquia, and academic positions, have been able to create and make available feminist and gender geographies in various languages (Garcia-Ramon Citation2003; Aalbers Citation2004; Johnson Citation2008; Huang et al. Citation2017). It reveals areas of influence and knowledge transmission pathways that have emerged through researchers’ physical locations, research programmes, and travels as they develop collaborations, carry out their teaching, or simply interact with colleagues; it also represents individual projects that have arisen out of indigenous knowledge and decolonializing struggles (Garcia-Ramon and Luna-Garcia Citation2007; Panelli Citation2008; Ulloa this volume; Zaragocin this volume). By implication, what the collection also reveals are the absences, difficulties, and fragility of this area of geographical knowledges in Africa, Asia, and Central Europe, as well as the hierarchies and power relations which persist within geography as a whole (Huang Citation2014; Browne Citation2015). What the above map occludes are the unequal plains of knowledge construction across geographies, and the persistent dominance of certain spaces over others within Feminist Geography knowledge production, especially that of Anglo-centric feminist geography (Zaragocin, forthcoming). These difficulties, along with the persistence of hierarchies of subject-matter within the discipline, should stimulate us to exercise greater vigilance and solidarity with isolated colleagues who are struggling to make their voices heard, to be recognized, and to develop their feminist teaching and research in sometimes hostile situations, as several contributions to this special issue demonstrate. Dina Vaiou uses the metaphor of navigation when she remembers: ‘This experience has been accumulated as a hard exercise in navigating through the denial and reluctant consent of various levels of administration, students’ changing acceptance, some women’s valuable active support, in the university and beyond, and other colleagues’ opposition or indifference’. On the other hand, Anindita Datta from India describes ‘the constant misogyny in the patriarchal institutional contexts’ as ‘the elephant in the room’.

Figure 1. Map of contributing author’s countries (cartographer: Trina King, Wilfrid Laurier University).

This situation leads, for example, to the exile of Italian gender geographers who go abroad to pursue a career and find more opportunities, as Marcella Schmidt di Friedberg and Valeria Pecorelli reminds us. Global connections and feminist solidarities are still very much needed in order to promote and extend feminist geography; we hope this special issue will inspire such transnational and intercultural alliances. In spite of policies supporting gender equality and the growing integration of gender perspectives into public policy, a great deal of progress is still yet to be achieved globally. Even in contexts where feminist geography has had a historically strong presence, changing dynamics toward feminist theory and gender studies generate obstacles to their development and dissemination. For example, vigilance is still required in the global North insofar as integration is sometimes synonymous with erasure. Monk and Hanson (Citation1982) outline two different strategies to incorporate feminist perspectives into the discipline of geography: ‘a strategy in which feminist geography develops as a specialization with separate feminist geography elective courses in teaching and separate feminist geography research programs, and a strategy in which feminist perspectives are integrated in core geography teaching and mainstream geographical research’. As Joos Droogleever Fortuijn points out, in the Netherlands, ‘However, gender issues and perspectives are not a structural part of curricula and research programs. Integration is highly dependent on the feminist commitment of individual lecturers and researchers. The danger is lurking that gender perspectives disappear from the teaching and research programs’.

This situation is aggravated by political and economic transformations that affect the organization of the academic world. Mireia Baylina and Maria Rodó-de-Zárate observe that:

The current situation of feminist geography in the Spanish context must firstly be situated within the framework of the financial crisis of the last few years and the dismantling of the public university. The cuts in higher education, the reduced budgets for both research projects and grants for pre- and post-doctoral training, combined with the lack of job offers in public universities, has had a strong impact on fields of research that were already experiencing difficulties in sustaining themselves. These policies have created obstacles against the inflow of the aforementioned new generations (whose doctoral theses are contributing fresh perspectives and interests to feminist geography) and against workplace stability for researchers with precarious jobs.

Meanwhile in the global South, an emerging feminist geography is taking place. In Ecuador, feminist geography will be a requisite in the first undergraduate degree on Human Geography at the Central University of Ecuador. And in Colombia, Brazil and Mexico, with more established critical geography intellectual traditions, alliances between existing gender departments have been key to sustaining feminist perspectives in geography departments.

This special issue arrives at a pivotal time when feminist geographies are still emerging, readjusting and in some cases consolidating as an intellectual tradition.

Giving a voice to both unique and shared experiences

This special issue is the product of the journal´s existing networks, but also of recommendations we received, of publications accessible in English and online through which we could identify potential contributors, and above all of the (positive or negative) responses to our requests for contributions from scholars in specific countries. Reports from several other countries, particularly in Africa, South America, and Asia, were to have been included in this issue; unfortunately either they were not ready for publication or the potential contributors pulled out, afraid that they would have nothing to contribute since they saw feminist geography as an incipient field in their country in both gender and critical geography studies. For example, this was true of Russia: where one of the specialists we contacted replied, ‘I am afraid that feminist geographies have not really penetrated Russia yet though gender studies more generally have’. Other countries like Ecuador and Colombia, engaged with the nascent nature of feminist geography and the geography of gender in each country respectively, highlighting the diverse levels of epistemic comfort with the field of feminist geography. Nevertheless, what was evident across scale and context was a complicit relationship between gender studies and critical geography studies. An already established or incipient gender studies field opened up the possibility of feminist geography or geographies of gender taking hold.

Most of the contributors come from and live in the country they write about, but this is not always the case; researchers who studied feminist geography in a different academic environment from the one they describe provide a different perspective. The paper on Sweden was written by Srilata Sircar and the one on Switzerland by Karine Duplan. Similarly, we chose to contact researchers at different stages of their careers, with varying levels of academic rank. Some of the contributors have just completed their doctoral dissertations and are looking for academic positions, while others have retired or are close to the end of their careers. Although a majority of those concerned with gender issues and feminist geography are women, there is an increasing presence of diverse gender identities leading these efforts. The degree to which feminist geography focuses solely on women varies across the globe, and in some countries, feminist geography still means a geography that encompasses primarily the experiences of women. In some countries it is clear that feminist geography has engaged more deeply with masculinities, sexuality and trans studies, and queer theory, as well as decolonial and intersectional research questions and approaches. For example, Levi Gahman and Tivia Collins (Anglo-Caribbean countries), Kamila Klingorová and Michal Pitonák (Czechia), Joseli Silva (Brasil), LaToya E. Eaves (Unites States) and Pablo Astudilo (Chile) have written on sexuality, trans and masculinity studies. Moreover, specialists of queer geographies such as Kath Brown (Ireland), Tiffany Muller (English speaking Canada) or Andrew Gorman-Murray and Louise Johnson (Australia) have written some papers. However, this possibility is not available to all. Thus, in Iran, Nazgol Bagheri notes that:

feminist contributions to the discipline including intersectionality, diversity, activism, and social change were not truly embraced in research projects under gender and geography category. For example, due to the rejection of homosexuality in Islam, it would be almost impossible for Iranian scholars to include sexual orientation while exploring intersectionality in human geography. Many of the above-mentioned concepts are political – therefore related to the national security – in Iran and may result in the isolation/imprisonment of scholars interested in working with such concepts.

In coordinating this issue, we chose to leave the contributors a great deal of freedom in their contributions, and selected not to impose a structure of any kind on the writing-up process. This was all the more important when the majority of contributors did not have English as their first language and were used to different rules around publishing academic work. Many texts that make up this special issue were not originally written in English, and so some of the final texts are translations from the authors’ original languages (including this introduction). Thinking and writing in another language, with similar but different academic norms, concepts and points of reference, makes geography even a more central part of the process. Where we write, think and do feminist geography still makes a difference in 2019. Feminist processes of translocation are necessary if we are to strengthen global networks of feminist geography (Zaragocin, forthcoming). We have therefore intervened only minimally in the form and content of the texts in order to let a multiplicity of approaches, perspectives and voices be heard. The texts collected in this issue, which make no claim to be exhaustive, not only reflect very different trajectories and contexts but also very different ways of approaching the exercise of writing a report on feminist geography. This is what makes the issue intellectually timely and rich, while at times embracing uncomfortable feminist translations across different spaces and scales. Most of the contributors have chosen to write individually, but some have preferred to collaborate with a co-author or write collectively in a group, thus turning the writing of the report into an active example of feminist practice. Some contributors have looked at the state of the geography of gender and feminist geography in their countries through the prism of their personal trajectories. Their trials and tribulations are inspirational for each one of us, and act as a reminder of the challenges that feminist geography and feminist geographers still face across the globe. We think particularly of Mary Njeri Kinyanjui from Kenya, who tells us her personal story and the challenges she has faced. Her courage is a source of inspiration for all.

Others have preferred to adopt a more impersonal chronological or thematic approach, such as the New Zealand writers’ collective that focused on the highlights of the study of geography in that country (Gail Adams-Hutcheson, Ann E. Bartos, Kelly Dombroski, Erena Le Heron and Yvonne Underhill-Sem with the help of Sophie Bond, Gradon Diprose, Karen Fisher, Lynda Johnston, Sara Kindon, Naomi Simmonds, Amanda Thomas and other WGGRN members who offered useful suggestions). Some have conducted a kind of archaeological or genealogical project, with an overview of existing feminist geography scholarship and teaching in their country. In the case of Norway, for example, Ragnhild Lund, Nina Gunnerud Berg, Michael Jones, and Gunhild Setten ‘identify relevant feminist and gender research, indicated by publications of feminist geographers, including PhD theses with a gender perspective’. The same is true for Argentina, where Mónica Colombara, also highlights how contemporary feminist debates such as the decriminalization of abortion, is putting feminist geography on the map of feminist politics in that country. Lastly, others have used this space as an opportunity to reflect on their specific local political situation, which is a cause for concern in many countries and highlights the major threats and attacks on gender studies and researchers who work in this field. LaToya E. Eaves rightly reminds us that:

Feminist and gender geographies have the opportunity – and truly the responsibility – to be responsive to the present political climate of the United States and to the nation’s geopolitical impacts on the world. Though the Trump campaign, election, and presidency have been considered the vehicles through which the alt-right, white supremacist uprising found its entry, it has actually been the mode through which the underbelly of the United States, and the West more broadly, to public consciousness. The issues that have surfaced more explicitly – couched in the impacts of racism-sexism, capitalism, and patriarchy – are relics of American and global history that never been addressed in spite of well-intentioned political maneuvers. The national undercurrent is structured on white supremacy, rooted in the rise of colonialism and capitalist exploitation and further demarcated by the global rise of nationalism.

Different conceptions of the geography of gender

This special issue reveals some very diverse conceptions of feminist geography and the geography of gender, its subject-matter, methods, epistemological foundations, and theoretical points of reference. As editors of this special issue, we were conscious of not determining what is and what is not feminist geography, and we see this as an exercise in decolonial feminist geography that queries the dominance of Anglophone literature. Contemporary understandings of gender or feminist geography must be heterogeneous. The definition and boundaries of ‘gender’ and ‘feminism’ vary, even though we all use these words. Thus some people understand ‘gender’ to refer only to women, while others include masculinities and LGBTQI studies. Mario Liong and Petula Sik-Ying Ho devoted their paper to the issues of masculinity in Hong Kong. Sexuality is sometimes included in work on gender, and sometimes treated as a distinct field of study. Tovi Fenster and Chen Misgav show how:

A focus on Israel’s Middle Eastern location entails a subtle use of homonationalism as a local cultural prism, revealing the ways in which some situated bodies and spatial politics are negotiable, limited, and occasionally disciplined. The Israeli LGBT and queer community and activists reveals politics that acknowledges the value of civil rights granted by the state and, at the same time, resists state politics and pink-washing manipulations.

However, in many countries sexuality is a social taboo, unthinkable and difficult to study from a critical perspective or in isolation, except in the context of demographics or public health. For his part, Pablo Astudillo Lizama is exploring the possibility of bringing geographies of homosexuality into existence in the Chilean academic context.

The very subject of feminist geography is sometimes dictated by international norms that define research topics via international and national funding. In Kenya, for example, Mary Njeri Kinyanjui observes that ‘gender and feminism concerns were largely supported by international donor aid’. This also helps to reinforce gender as a Western construct and import, and thus this type of geographical inquiry might reproduce colonial processes and approaches. As a result, one strategy employed is not to label these donor funded studies with the word ‘feminist’. Thus, Levi Gahman and Tivia Collins note that ‘Although ‘feminist geography’ as a key term may not appear as frequently as one would hope across the Anglophone Caribbean, the critical and caring ethics, as well as political edge, advocated by practitioners of feminist geography certainly are evident. The methods adopted are also heterogeneous. In some countries spatial analysis, cartography, and statistical analysis are seen as the hallmarks of academic work in the field. Complying with these orthodox norms in order to prove the legitimacy of research conducted in an unconventional heterodox field is an effective strategy for the development of feminist research. In other countries, influenced by the postmodern critique of the sciences, more qualitative approaches and ethnographic methods are favoured (Domosh Citation2002), although GIS and quantitative methods can and are being re-appropriated by feminist geographers.

The various contributions collected in this issue demonstrate not only the attractive force and massive predominance of Anglophone research, which serves as a model and point of reference with respect to the works cited, but also the appropriations, creations, and unique pathways which draw especially on the work of indigenous feminists and formulate specific political and academic agendas. Colombia (Astrid Ulloa) and Ecuador (Sofia Zaragocin) are connecting indigenous feminisms and territorial feminist perspectives with emerging feminist geography literatures stemming from South America. They are engaging with decolonial discussions on geographical knowledge construction and a plurality of ontological notions of space and territory.

Working collectively

One of the features shared by most of the contributions is the role of places and collectives which enable feminist geographers to think, publish, and conduct their research. Cross-generational, transnational forms of solidarity are an essential bulwark against the attacks, frustrations, and obstacles to their career progression frequently faced by feminist geographers. As Joseli Maria Silva observes:

The international alliances, through the support given to the participation in events and publications, empower local feminist geographers who did not depend on the approval of national research centers to legitimate their studies. In a context in which the country has valued the internationalization of the scientific production, the relations established contributed definitely to empower local actors in the national academic nets, building the visibility of the feminist geographies in Brazil.

One of the essential sites of the production of transnational feminist geography solidarity occurs around scholarly meetings (Robic and Rössler Citation1996). Annual conferences (the AAG, RGS-IBG, and IGU meetings, to name only the best known), workshops and seminars (the Seminário Latino-Americano de Geografia, Gênero e Sexualidades in Brazil, and the Doreen Massey Reading Weekend in German-speaking countries, for example) are essential meeting places where stimulating interactions as well as opportunities for mentoring and collaboration can occur. Charlotte Wrigley-Asante and Elizabeth Ardayfio-Schandorf showed the impact on the discipline of the conference organizing by the Geographic Union’s Commission on Gender and Geography at the University of Ghana, Legon, in 1995. In the same way in Japan, the Nara Pre-Conference of the Gender and Geography Commission, in August 2013 brought together Western and Asian researchers to learn about the current status and issues of gender research in geography. As noted by Yoko Yoshida; ‘The steady efforts of the groups have advanced gender research in geography in Japan’. Likewise, transnational feminist and critical geography collectives in Latin America are pushing forward a feminist geography agenda (Colectivo de Geografía Crítica del Ecuador, Geobrujas and Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo).

These serve as a reference points for future collaborations. Anindita Datta and Ragnhild Lund (Citation2018) used the term ‘inspiring spaces’ to name these spaces of collaboration, cooperation and co-writing. However, access to these spaces is often made very difficult because of austerity budgetary policies in many universities and the very high cost of conference registration fees, not to mention accommodation and living costs in the major cities which host these events. Restrictions on travel related to visa issuance policies add to these difficulties for many of our colleagues from the Global South. Establishing scholarships or adopting more videoconference opportunities may diversify and increase international collaboration.

Local and national networks also bring feminist geography into existence through interaction, and collective support. This is true of numerous commissions and research groups that have developed either within professional associations or independently of them. They include, for example, the Women and Gender Geographies Research Network of Aotearoa New Zealand and Canadian Women and Geography (CWAG). Some of these networks have mailing lists which can help broaden their reach and serve as an effective means of disseminating information about publications, announcements of scholarly meetings and funding and employment opportunities. This also makes it possible to connect with networks of feminist or queer activists.

Lastly, publications are essential spaces for bringing the geography of gender and feminist geography into existence and dialogue with one another. We hope this special issue contributes to this, following the role that Gender, Place and Culture has already played in the development of the field for the last quarter century (Bondi and Domosh Citation2014). However, access to these journals, usually via paid subscription, is sometimes very difficult for colleagues working in universities who do not subscribe to them. The Revista Latino-Americana de Geografia e Gênero is an example of a multilingual, freely accessible, journal which stimulates the growth of Portuguese- and Spanish-language research. Seeking more opportunities to openly disseminate feminist geographical research remains an important goal for feminist geographers collectively. With that goal in mind, we are grateful to Taylor and Francis, the publisher of Gender, Place and Culture, for making this themed issue freely available.

Acknowledgements

We would like express our profound thanks to Pamela Moss for the trust and freedom she has given us in the production of this special issue. She was responsible for initiating our fruitful collaboration, which has been a great experience and an implementation of our feminist commitment. We would like to extend warm thanks to all the contributors who agreed with enthusiasm and generosity to respond positively to our requests and to participate in this exciting project, although it added more work to their often-busy schedules. Finally, we would like to acknowledge those who agreed to review and edit the initial versions of these texts, most of which were written by non-English-speaking authors. This is a difficult, tedious, often thankless and generally invisible job, for which they deserve warm thanks. To finish, we want to thank to Margaret Walton-Roberts and Pamela Moss to their comments and suggestions on this introduction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianne Blidon

Marianne Blidon is Associate Professor at Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne University. She is a feminist geographer, working on gender and sexualities. She was the first French geographer to complete a PhD on the geography of sexualities. She has organized several seminars and symposia on gender and queer geographies, helping to legitimize these topics in France. She founded, with other social researchers, a free open-access journal, Genre, sexualité & société, which she directed for eight years. She is a member of the IGU Gender and Geography commission. She has published several special issues on gender geography and the geography of sexualities in journals such as L’Espace Politique, Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine and Echogéo.

Sofia Zaragocin

Sofia Zaragocin is an Assistant Professor at the International Relations Department of Universidad San Francisco de Quito, with research interests on decolonial feminist geography and processes of racialization of space. She has written on geographies of settler colonialism along Latin American Borderlands, decolonial feminist geography and mapping gender-based violence in Ecuador. She has been active in developing feminist geography in Ecuador as part of the Critical Geography Collective of Ecuador, an autonomous interdisciplinary group that seeks territorial resistance through a wide range of socio- spatial geographical methodologies. She is also part of a team of three women human geographers in Ecuador that are putting together the first undergraduate degree solely focused on Human Geography in that country.

References

- Aalbers, Manuel B. 2004. “Creative Destruction through the Anglo-American Hegemony: A non-Anglo-American View on Publications, Referees and Language.” Area 36 (3): 319–322.

- Bondi, Liz, and Mona Domosh. 2014. “Remembering the Making of Gender, Place and Culture.” Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 21 (9): 1063–1070.

- Browne, Kath. 2015. “Contesting Anglo-American Privilege in the Production of Knowledge in Geographies of Sexualities and Genders.” Revista Latino-Americana de Geografia e Gênero 6 (2): 250–270.

- Datta, Anindita, and Ragnhild Lund. 2018. “Mothering, Mentoring and Journeys Towards Inspiring Spaces.” Emotion, Space and Society 26: 64–71.

- Domosh, Mona. 2002. “Toward a More Fully Reciprocal Feminist Inquiry.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 2 (1): 107–111.

- Garcia-Ramon, Maria Dolores. 2003. “Globalization and International Geography: The Questions of Languages and Scholarly Traditions.” Progress in Human Geography 27 (1): 1–5. doi: 10.1191/0309132503ph409xx.

- Garcia-Ramon, Maria Dolores, and Tony Luna-Garcia. 2007. “Challenging Hegemonies through Connecting Places, People and Ideas: Jan Monk’s Contribution to International Gender Geography (with Particular Reference to Spain).” Gender, Place and Culture 14 (1): 35–41. doi: 10.1080/09663690601122200.

- Huang, Shirlena, Janice Monk, Joos Droogleever Fortuijn, Maria Dolores Garcia-Ramon, and Janet H. Momsen. 2017. “A Continuing Agenda for Gender: The Role of the IGU Commission on Gender and Geography.” Gender, Place and Culture 24 (7): 919–938. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2017.1343283.

- Huang, Shirlena. 2014. “Developing a View from within: Researching Women’s Mobilities in/out of Asia.” Asian Journal of Women's Studies 20 (1): 8–30. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2014.11666171.

- Johnson, Louise C. 2008. “Re-Placing Gender? Reflections on 15 Years of Gender, Place and Culture.” Gender, Place and Culture 15 (6): 561–574. doi: 10.1080/09663690802518412.

- Monk, Janice, and Susan Hanson. 1982. “On Not excluding Half of the Human in Human Geography.” The Professional Geographer 34 (1): 11–23. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1982.00011.x.

- Panelli, Ruth. 2008. “Social Geographies: Encounters with Indigenous and More-Than-White/Anglo Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 32 (6): 801–811. doi: 10.1177/0309132507088031.

- Peake, Linda. 1989. “An Overview of Feminist Geography in the 1980s: Introduction to Theme Papers on the Challenge of Feminist Geography.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 13 (1): 85–121. doi: 10.1080/03098268908709063.

- Robic, Marie-Claire, and Mechtild Rössler. 1996. “Sirens Within the IGU. An Analysis of the Role of Women at International Geographical Congresses (1871–1996).” Cybergeo, 14. http://cybergeo.revues.org/5257.

- Zaragocin, Sofia. Forthcoming. Challenging Anglophone Feminist Geography from Latin American Debates on Territory. In Feminist Geography Unbound: Intimacy, Territory and Embodied Power Virginia, edited by Banu Gokariskel, Michael Hawkins, Christopher Neubert, and Sara Smith. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.