Abstract

In this article, we analyse two parallel processes taking place in the Swiss healthcare sector, namely differentiation and standardisation: On one hand, the health sector is increasingly characterised by differentiation that originates from the specialisation of training, the differentiation and academisation of nursing, the feminisation of medicine, the migration of healthcare personnel, and the entry of men into nursing professions. In addition, a new generation joining the health sector labour force is challenging taken-for-granted notions about health professions. On the other hand, healthcare organisations such as hospitals need to ensure they are functioning well by increasingly relying on standardisation processes such as checklists, standardised protocols, or ethical guidelines. For this paper, we have conducted an institutional ethnography of a Swiss acute hospital by employing an intersectional analysis. Based on interviews and shadowing, we argue that the social differences between and among nurses and physicians are constantly negotiated every day. We demonstrate that those differences lead to power imbalances along the intersectional axes of age, gender, place of education, and professional position. Our findings have implications for general debates in health-related fields; for management and organizational studies more in general; and in particular for feminist labour geographies, as they place debates on work-relations, power, hierarchy, and intersectional social differences into a specific organizational and spatial context.

Introduction

I spent one year in Germany as an assistant physician. As the anaesthesia nurses do not support the physicians as strongly as in Switzerland, it was incredibly challenging. In the surgery room in Germany, I had sole responsibility; the nurses do not scrutinise the physicians’ decisions. Twice, the anaesthesia process almost went wrong; we had been very close to reanimation. The nurses did not dissuade me from the incorrect path I had taken. Here in Switzerland, I know that the anaesthesia nurses not only have a plan A, but a plan B and a plan C. That is why it is more relaxing working as a senior anaesthesiologist in Switzerland than as an assistant physician in Germany. Here, I can fully rely on the nurses’ competence, and I really appreciate that.

A few minutes before we had this conversation with Leo, a male senior physician in his early thirties, we witnessed an exchange between Leo and Patrick, an expert male anaesthesia nurse in his late forties. They discussed the intubation of a patient. On even ground, the two of them pondered the different possibilities and what consequences they each had on the corresponding medication. (Shadowing 2018)

These shadowing field notes in an anaesthesia ward of a Swiss acute hospital challenge the typical image we have of interactions between nurses and physicians. The common idea is still that an elderly male physician – a ‘demigod in white’, as German-speaking people used to say – has the sole responsibility and decision-making power regarding his patients, while a young female nurse submissively executes his commands. However, in the last two decades, the collaboration between nurses and physicians in Swiss hospitals has undergone major transformations similar to those in other countries of the Global North.

Still, the daily collaboration between nurses and physicians does not go without difficulties. Nurses often complain about the lack of respect they face within and outside the hospitals. This paper demonstrates that this, for example, is mirrored in major wage disparities, in discussions about the nurses’ responsibilities, in limited promotion prospects, and in scarce exit options for nurses. Even though nurses compose the backbone of every health institution, a hospital’s reputation is not built on its nurses but on its physicians. Nurses are not deployed to attract patients, contrary to physicians, as the hospital’s CEO and two members of the senior management explained. This is exemplified on the researched hospital’s home page, where every ward is represented by names and pictures of all its senior and chief physicians. The nurses, in contrast, are only represented by the head nurse – if at all.

Next to differences between nurses and physicians, we also encountered important negotiations within both professional groups. In this paper, therefore, we examine how social differences between nurses and physicians as well as within both groups intersect and how they are negotiated in everyday working life within hospital settings. We further ask where and why social differences lead to power imbalances. Overall, we demonstrate that age, gender, position, educational background, and place of education are the most obvious social differences among and between nurses and physicians and that, generally, social differences are increasing. We argue that this increase in social differences is linked to general trends within the Swiss healthcare sector: First, the increasing specialisation of physicians requires more interdisciplinary and interprofessional collaborations. Second, the specialisation and partial academisation of nursing results in highly trained nurses, specifically in anaesthesia, emergency, and intensive care. Third, many women and generally a new generation have been entering medicine. These groups aim for a more equal balance between work, family, and leisure by working part-time and demanding new working models. Fourth, hospitals are trying to adopt flatter hierarchies. Finally, many healthcare personnel working in Switzerland gained their diplomas in other, mostly European countries.

To approach the everyday negotiations of difference and to understand how they are framed by institutional as well as societal practices, norms, and discourses, we conducted an institutional ethnography (Smith Citation1987, Citation2005) in a Swiss acute hospital by employing an intersectional analysis (Crenshaw Citation1991; Valentine Citation2007). From the qualitative data we gained through interviews and shadowing in the anaesthesia, cardiology, and emergency wards, two dynamics emerged that seem at first sight to contradict each other but proved to converge into a coherent picture: standardisation and differentiation. By differentiation we refer to an increase of social differences in terms of age, place of education, and gender among the professionals. We use the term differentiation instead of others such as fragmentation to underline that the differentiation is also linked to power geometries along social differences captured in the concept of intersectionality. The differentiation is met institutionally by standardisation procedures and measures to insure coherent functioning of health treatments; this is partly due to safeguarding and transparency requirements. Leaning on Timmermans and Epstein (Citation2010, 71), we understand standardisation as ‘a process of constructing uniformities across time and space, through the generation of agreed-upon rules’. In the researched hospital, procedural standards can, for example, be observed in recruiting practices, in initial training plans, or in checklists. We argue that the processes between standardisation and differentiation are balancing acts that are constantly negotiated by different actors within the space of hospitals.

The applied ethnographic approach enriches debates from mostly quantitative management studies with a deep insight into power relations that are not static, but rather constantly negotiated and shifting. Our intersectional analysis unpacks generic definitions and formal categories such as qualification, shows differentiation not only between but also within professional groups, and addresses broader discussions about gender as well as generational change in the healthcare sector.

Our argument starts with explaining our conceptual approach, which searches for intersectional negotiations of differentiation and standardisation through an institutional ethnography. We then provide the necessary background on the Swiss healthcare sector and the specific hospital we conducted research in. Finally, we pry social differences apart by discussing differences among nurses, among physicians, and between nurses and physicians, respectively, to analyse the intricate co-functioning of differentiation and standardisation.

Studying intersectionality through an institutional ethnography

Most of the literature on inequalities in healthcare has analysed the access to healthcare institutions (for an intersectional analysis in this regard, see Gkiouleka et al. Citation2018) or the interactions between clinicians and patients. Recently, scholars also examined how communication and cooperation among medical staff as well as their education impacts safety and mortality rates among patients (Aiken et al. Citation2011; Weaver, Dy, and Rosen Citation2014). In contrast, social differences among and within professional groups of the healthcare workforce have rarely been researched (Long, Hunter, and van der Geest Citation2008, 73).

The empirical entry point of this article hints to the fact that a person’s position and place of education are crucial when researching social differences in hospitals. Thus, the typical triad of race, class, and gender is not sufficient in an intersectional analysis of such institutions. Further social differences, such as qualification, position, generation, work experiences, language skills, or place of education, intersect in complicated ways and open a field for power geometries. Research on the healthcare sector has typically focused on single categories of difference, such as the migration of health workers (Bradby Citation2014; Connell Citation2010; Kingma Citation2006; Prescott and Nichter Citation2014) or the feminisation of medicine and the masculinisation of nursing (Cottingham Citation2017; Cottingham, Erickson, and Diefendorff Citation2015; Hendrix, Mauer, and Niegel Citation2019; Lindsay Citation2005; Riska Citation2008). We argue that the analysis of such single categories is insufficient and follow McDowell’s (Citation2008) claim for more intersectional analysis in labour geography. Until now, few studies have researched how complex power geometries impact intersecting social differences in workplaces (see also Lee Citation2019). While critical feminist research has developed a strong gender lens, other social differences have been rather neglected (Bonds Citation2013) or, in the case of race, reduced to a territorial fix (Bonnet and Nayak Citation2003).

Clearly, we must understand intersectionality in an open way to go beyond the initial distinctions of race, class, and gender. While race also matters for the case of Swiss hospitals, it is virtually erased from our data due to the lens inherent to our data collection strategy. Focusing on Swiss nursing staff and physicians leads to a mostly white sample, while racialized personnel can be found in other professions such as cleaning, cooking, logistics, etc. If we do not discuss race any further, it is not because it does not matter in the institution itself, but because it does not serve as a differentiating factor in the observed power geometries among nurses and physicians in the hospital wards studied.

Finally, to understand the power relations at play and their constant negotiation, we need an in-depth appraisal of the institutional setting, which is framed by what Dorothy Smith (Citation1987, Citation2005) called an ‘institutional ethnography’. This conceptual approach also implies a methodological stance, namely the notion that institutions function the way they do because powerful relationships are constantly built and negotiated; relationships organise people’s actions in these institutions. Analysing an organisation in action means examining how a specific apparatus of management arises, how it is controlled and developed (DeVault 2006, 295; Smith Citation1990, Citation2005), and how (oppressive) ruling relations intersect institutional and cultural boundaries (Smith Citation1987, 244). Ruling relations are therefore ‘actual people’s doing under definite material conditions’ (Smith Citation2005, 70). The term ‘ruling relations’ implies that a powerful order is embedded in relationships. Relations are always based on interactions and negotiations. They include more than one person and possibly objects or, as in our case, bodies and technologies.

Institutional ethnography is about understanding institutions from the points of view of the people within them. It relates to the feminist idea that powerful structures and relations can best be understood from the perspectives of those subjected to them in their everyday lives and work (Smith Citation2005, Citation2006). Institutional ethnography is about ‘how everyday experience is socially organised’ and focuses on the role of power (Wright Citation2003, 243) by ‘making visible how ruling relations are transported through knowledge, experience, discourse, and institutions’ (Wright Citation2003, 244). The emphasis thus lies on the processual aspect of these relations instead of on fixed power structures (Nadai Citation2012). Geographers researching institutions have used this method by paying special attention to spatial aspects (for an overview, see Billo and Mountz Citation2016). An institutional ethnography shows the hospital not as a monolithic space, but as a collection of spaces such as surgery rooms, reception areas, visitors’ rooms, and staff rooms.

We conduct the institutional ethnography by focusing on intersectional power relations. Various scholars have criticized the overuse and mainstreaming of intersectionality (Bilge Citation2013; Davis Citation2008; Salem Citation2018) – a concept originally based in an activist, anti-racist, feminist setting, and made popular by Crenshaw (Citation1991). Ever since the seminal article by Valentine (Citation2007) that demonstrates that space, time, and identities are intrinsically connected, social and cultural geographers have widely used intersectionality to provide fruitful insights into questions of power, inequality, and discrimination (Hopkins Citation2019, Citation2018; Johnston Citation2018; Rodó-de-Zárate and Baylina Citation2018; Vaiou Citation2018). Intersectionality is not about simply adding up single categories; intersectional analysis rather ‘helps reveal how power works in diffuse and differentiated ways through the creation and deployment of overlapping identity categories’ (Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall Citation2013, 797). In short, social differences are constructed and reconstructed through power relations – or power geometries, as Massey (Citation1999) called them. Intersectionality, while initially developed to understand the lives of black American women, has travelled (Collins Citation2015; Salem Citation2018) and has become a concept used to understand how powers of segregation, exclusion, and discrimination operate around the globe, although the concrete articulations of these powers often differ locally (Mollett and Faria Citation2018).

Conducting an institutional ethnography by employing an intersectional analysis offers deep insights into how social inequalities reproduce and reinforce multiple social categories, and how these categories are negotiated in relation to space and time (Billo and Mountz Citation2016, 215; Rodó-de-Zárate and Baylina Citation2018, 549). As Gkiouleka et al. (Citation2018, 92) aptly state, the combination of both approaches accounts for ‘the complexity of the intertwined influence of both individual social positioning and institutional stratification’, not least within the healthcare sector.

Methodological approach

This article is based on data collected in a Swiss acute hospital. We conducted 15 interviews with members of the middle and senior management and collected documents, such as the hospital’s magazine, regulations, and guidelines, that informed us about ongoing discussions and standardisation processes within that institution. Additionally, we conducted 34 shadowing units between August 2018 and February 2019; each consisted of following one healthcare professional within the institution for half a day.

Shadowing is an ethnographic method often used in organisational and management studies (Czarniawska Citation2012, Citation2014; McDonald and Simpson Citation2014) to research hospitals as institutions (Gill, Barbour, and Dean Citation2014; Gilliat-Ray Citation2011). This method is extremely appropriate when conducting an institutional ethnography (Gilliat-Ray Citation2011; Quinlan Citation2009). Exactly what shadowing entails is contradictorily discussed (Gill, Barbour, and Dean Citation2014, 90). Generally, it consists of following a person during his or her everyday working life within an institution, receiving their explanations and insights (Czarniawska Citation2012). During shadowing, we observed interactions among the healthcare personnel as well as with the patients. The latter were not part of our study, however, and would open a myriad of additional questions worth studying (Ammann, Richter, and Thieme Citation2020).

We conducted shadowing in the anaesthesia, cardiology, and emergency wards. All three studied wards are special compared to more general wards. First, the physicians and nurses there closely collaborate in their daily work. Second, the anaesthesia and emergency nurses have gained specialised diplomas, for which they studied 2 years in addition to their nursing education. As we will further discuss below, in these wards, the percentage of male nurses is much higher than in the general wards. Third, only a minority of the caring professionals in the cardiology ward possess a nursing degree; the majority has undergone vocational training as medical-technical assistants. The researched institution is a medium-sized Swiss acute hospital that offers a broad spectrum of medical services. All names are pseudonyms to ensure the research participants’ anonymity.

Increasing differentiation in the Swiss healthcare sector

The tendency towards differentiation that emerged from our data is coupled with more general developments in the healthcare sector. Similar to other countries in the Global North, the Swiss healthcare sector is transforming towards privatisation, commercialisation, and professionalisation, as well as management principles of economic efficiency and quality assurance. These trends are combined with the employment of foreign-trained healthcare personnel due to an acute staff shortage (Aluttis, Bishaw, and Frank Citation2014; Labonté and Stuckler Citation2016). More than a third of the physicians working in Switzerland possess a foreign diploma, usually from Germany (Hostettler and Kraft Citation2018, 414). Two out of five nurses working in Switzerland have a foreign diploma, most of them stemming from neighbouring France and Germany (Merçay and Grünig Citation2016, 2). Furthermore, nursing education partly differs between French and German speaking parts of Switzerland. Thus, educational, regional, and linguistic differences add additional layers to these differentiations.

The historical roots of the care profession in Switzerland go back to care work done by nuns, monks, or private caregivers at home. Run by social, economic, and medical changes, nursing turned from a ‘serving position’ into an independent and highly specialised profession (Braunschweig and Francillon Citation2010). Today, one can become a nurse by completing a vocational training of two to three years, by earning a nursing diploma at specialised schools, or by gaining a bachelor and masters in nursing science at a university of applied science or at a university (including a PhD). These various training opportunities bring new differentiations of skills and grades into the nursing teams in hospitals and nursing homes (Horisberger Citation2013). This international trend (Dubois and Singh Citation2009; Freund et al. Citation2015) requires negotiation processes related to skills and competences among nurses (van Eckert, Gaidys, and Martin Citation2012, 903), but also within the broader political context. Issues regarding appropriate wages or financing care services according to actual expenditure are presently debated on the national level by an initiative for a popular vote to strengthen the position of the nursing profession.

The strong presence of women is characteristic of healthcare personnel. In 2014, women represented 85% of nurses in Switzerland. The percentage of men is highest among the medical-technical nurses, at 32% (Merçay, Burla, and Widmer Citation2016, 35). Fewer than 10% of nurses with vocational training are male, more than 10% of certified nurses are men, and of the certified nurses with a 2-year additional specialisation, over 20% are male (Bundesamt für Statistik Citation2015). This is comparable to the researched hospital where, for instance, in 2018, half of the anaesthesia nurses and one-fifth of all nurses in the emergency ward were male. Overall, the few men in the ‘female profession’ of care are better trained and often occupy the executive positions: Although there is no official data about the percentage of male nurses in leading positions, one indicator is that male nurses represent 29% in the Swiss Nurse Leaders organisation but nationally constitute only 15% of nurses.

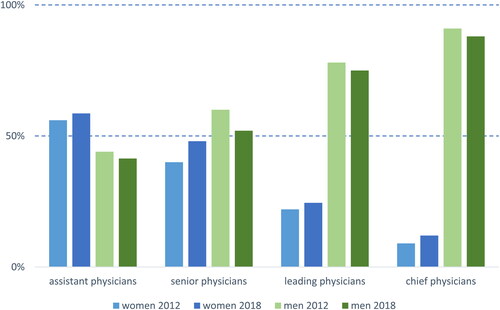

Simultaneously, we can observe a feminisation of the medical profession: Since 2005, more women than men have finished their medical studies in Switzerland. Women below the age of 45 already constitute the majority of physicians. However, time does not lead necessarily to an automatic increase in the proportion of female physicians in higher hierarchical levels (see ), and the increase of women in leading positions remains small (Hostettler and Kraft Citation2013, 455; Hostettler and Kraft Citation2018, 414). There is also a remarkable difference between the disciplines. The highest percentage of female physicians work in children’s and youth psychiatry (64.7%) and in gynaecology (62.9%); men are highly overrepresented in thoracic surgery (94.3%) and in facial surgery (92.3%). Additionally, a discrepancy exists regarding the level of employment. In hospitals, female physicians typically work more often part time than their male colleagues (Hostettler and Kraft Citation2018, 413–414). Swiss statistics demonstrate that, overall, mothers invest more time in childcare while fathers invest more time in education to advance their careers (Bundesamt für Statistik Citation2016). Furthermore, no paternity leave has been existing in Switzerland so far. A popular vote has accepted two weeks of paternity leave only in autumn 2020.

The researched hospital generally matches this picture: Fewer female than male physicians are employed at the top of the hierarchy; however, the number of female chief physicians in the researched hospital is still twice as high as the Swiss average. Furthermore, women constitute 89% of the hospital’s nurses, which is slightly higher than the Swiss average. The researched hospital has a turnover rate of 11% (similar to other Swiss hospitals) which results in the need to constantly train and integrate new staff. The following sections therefore explore the everyday negotiations that develop around the abovementioned forms of differentiation and how they are met by institutional standardisation practices.

Everyday negotiations among nurses: differentiation within a professional group

In the researched institution, the current changes in relation to their professional training seem to divide the nurses into two groups: The younger generation, which is up-to-date about the latest scientific findings and adheres to the learned standards and protocols, encounters an older generation which relies more on intuition and long-term working experience. As education in nursing underwent a thorough transformation during the last two decades, both groups only have limited insight into the other group’s professional training, concepts, standards, and procedures. A female nurse in her fifties explained,

We have more of a gut feeling and work with the aid of all our senses compared to the younger generation. They work very much according to a fixed scheme. The young nurses have been trained completely differently. Both sides can profit from each other, but respect and appreciation are necessary. I ask myself how it will be when we from the older generation become fewer and fewer and more younger persons are stepping in. (Shadowing 2018)

Although thorough expert knowledge and training are required as a basis for medical and nursing decisions, intuition and work experience are equally important for nurses’ and physicians’ work routines. Differences in procedure between older and younger nurses are seen as both enriching and tense. However, next to differences in terms of experiences and approach, there is an additional difference regarding the understanding of the care profession and its value in a nurse’s life. This relates ultimately to their identities as workers (McDowell Citation2009), as the following example demonstrates:

The understanding of work between the generations in relation to teamwork is different. For the younger generation, work is not everything in life. They are less willing to fill the gap in case of staff shortages, such as when someone is absent due to sickness. Actually, they are right. If we help out all the time, nothing changes on the institutional level. At the same time, the situation gets worse for those who are on duty if they do not help out. (Female expert nurse in her late forties, shadowing 2018)

Although it was (and partly still is) normal for the older generations to sacrifice themselves for their patients and workplace, the younger generation hesitates less to say ‘no’ to long hours or to take the fall for staffing shortages rather than work at the expense of their own health or life balance. This demand of an ideal life balance, characteristic for the so-called Generation Y (Jamieson, Kirk, and Andrew Citation2013), conforms to societal changes and training schools’ curricula. In these curricula, a new self-confidence and new work identities in the care profession are being forged, as two nursing teachers confirmed (informal conversations 2019).

The responsibilities of the care profession are often physically and psychologically demanding. Therefore, the ageing process influences the power geometries of a workplace such as a hospital. Older nurses struggle with fast-paced work and day-to-night shifts (shadowing 2018). New regulations, such as standardisation procedures for assessing the gravity of a health problem in the emergency ward, the handling of new medical equipment, as well as digitalisation in general, can enhance safety but at the same time might pose challenges for senior nurses. The generational divide based on education and work identity is therefore intensified by changes and developments introduced by the institution.

Gender is another major social difference among nurses. A female nurse in her early fifties explained that women who have children typically reduce their employment but men work full time, gaining more experience and consequently achieving leading positions (shadowing 2018). This example shows the implicit assumption that women remain predominantly responsible for childcare. The workers’ identity of male versus female nurses not only differs according to training and career expectations, but also current discourses on masculinities (Hopkins and Noble Citation2009), rarely questioning disparities in wages.

We did not have many men in our team. But the few men we had were lucky because every team is happy to have a man. But male nurses only come if they receive a good wage. That is the difference with men: They only come if the wage is fair, otherwise they say, ‘no, thank you’. (Elderly former nurse, interview 2018)

Furthermore, re-entry after maternity leave can be challenging due to the fast pace of nursing work, innovations, and specialisation. For example, one of the research participants wanted to return to the emergency ward after a longer childcare break but was scared to do so, because so much had changed since she had left. Gender, especially when linked to maternity and the prevailing roles regarding care, interlinks with the specialized positions in nursing, resulting in more men in specialized nursing and in leading positions.

As mentioned, the lack of healthcare specialists in Switzerland has led to an increase in foreign, mostly European-trained staff. This adds another layer of social difference to the nursing profession. Even though research participants rather stressed the positive effects of working with people who gained their diplomas outside Switzerland and framed it as ‘intercultural collaboration’, some resentments were detectable. In an interview, Eva, a head nurse, preferred not to have too many nurses from the same ‘cultural background’ or specific region in her team due to earlier negative experiences. At the same time, she stressed that everyone enjoyed a particular young nurse trained in a neighbouring country (interview 2018).

Depending on the country of training, the competences attributed to care in practice may differ, as the initial example demonstrates. Generally, hierarchies seem to be flatter in Swiss hospitals compared to neighbouring countries. Foreign-trained nurses must therefore adapt to the local working culture. Our research further hinted to different ways of care training in German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland. Here, the place of education and the language differences within Switzerland (but also between Switzerland and other countries of training) impact the negotiation of hierarchies whereby ‘the local’ is taken as the norm to which foreign-trained nurses must adapt.

Everyday negotiations among physicians: Gendered life cycles and careers

There is also a generational gap among physicians. Working up to 90 hours per week was quite common for physicians one or two generations ago. Being a physician was a calling associated with the highest societal recognition and prestige. Some of the elderly people living in rural Switzerland still call male physicians Mr Doctor, which has a connotation of admiration and awe. The term Mrs Doctor, however, was not used for a female physician, but the physician’s wife. Until 2005, the working hours of physicians adhered to and depended on the needs of the hospital. Since then, the nationally valid Swiss Working Hours Act set a maximum working week of 50 hours for assistant physicians. Although still working overtime, the overall working hours are steadily reducing (Pöhner Citation2018). Generally, a trend in executive positions towards new working models, such as job- or top-sharing, is evolving because of two factors. First, the younger generation does not define themselves solely by their work or prestige anymore. Second, since 2005, more women than men have finished their medical studies, leading to the feminisation of medicine (Kraft and Hersperger Citation2009, 1823).

The field of physicians has been male-dominated for a long time, and the entry of women has brought a gender divide into the field. While some young male physicians aim to work part-time, for many career-oriented male physicians, this is not an option. The latter concentrate on working in highly prestigious and competitive fields such as surgery or cardiology and are likely to reinforce and reproduce their working patterns and expectations with others when entering leading positions. Accordingly, there are differences concerning the acceptance of part-time work by discipline. Disciplines such as gynaecology or paediatrics, which women entered long ago and where they now constitute the majority, seem to be more open in this regard. A female cardiologist in her late thirties called her prestigious but also highly competitive discipline a ‘shark pool’ (shadowing 2018). Gender and age or generation intersect to form male-dominated specialisations where the career-oriented model prevails, while other female-dominated disciplines offer more balanced work-life models.

The moment when many women (and men) become parents often coincides with the time of being an assistant physician – the so-called ‘rush hour of life’. When they reduce their level of employment after becoming parents, their training period drags on, which the leading physicians we spoke to disliked. They further stressed that an assistant physician who obtains her (or seldom his) specialist exam after 8 years of working a job at 50% is less valued than a person with a 4 years and 100% job record. The institutional challenges female physicians face to pursue academic careers are numerous (Edmunds et al. Citation2016; Reimann and Alfermann Citation2018; for Switzerland, see Hendrix, Mauer, and Niegel Citation2019). Sometimes they are subtle, such as when two senior male physicians rolled their eyes when talking about ‘another pregnant (assistant) physician’ (shadowing 2019). Sometimes they have far-reaching consequences, such as for this female physician in her mid-thirties:

When I applied as an assistant physician in a surgery ward of a university hospital, I did not put my two children in the CV, and I did not say anything in the interview. During the first four months, no one knew that I had children. I wanted them to judge me based on my work. If you have kids, you do not get the same chances to do interesting operations. People think that you are stupid because you have children. (Shadowing 2018)

This statement shows that women as mothers must find strategies and that they are poised to take a lot on to avoid being discriminated against. Sometimes, this means keeping quiet about their own children. Societal conditions problematize motherhood and in the capitalistic logic of the labour market, a woman is always a risky candidate: Either she already has children – and they can get sick at any time – or she could become pregnant. While a man can be a doctor or nurse who stands in for the universal figure of the healthcare provider, a woman is always also particularized by her gender and the social role she is prescribed. When persisting phenomena such as the glass ceiling are debated, a broadly accepted rationale seeks to find the answer to the problem in an individual woman’s behaviour instead of questioning structural conditions (Schueller-Weidekamm and Kautzky-Willer Citation2012). The entry of women and of a younger generation into the profession of physicians does not alter the system as such; rather, specific health institutions and specialities facilitate part-time, more equitable, and different career models while the majority does not (yet) provide these possibilities.

Everyday negotiations between nurses and physicians: between collaboration on equal footing and power imbalances

Collaboration and communication between nurses and physicians have been recurring issues in research (Casanova et al. Citation2007; Lindeke and Sieckert Citation2005; for Switzerland, see Brown and Holderegger Citation2017). Many older research participants vividly remember how ward rounds used to be some decades ago when they dreaded the chief physicians and did not dare say a word. As the quote at the beginning of this article has demonstrated, the collaboration between physicians and nurses has changed significantly. However, implicit conventions affecting their relationship and impacting power geometries still remain (Thomas, Sexton, and Helmreich Citation2003).

One example is the object that symbolises the gap between nurses and physicians unlike any other: the stethoscope. Some have even named this the ‘stethoscope gap’. The stethoscope is the physician’s identifying feature. However, based on the ongoing trend towards the specialisation and academisation of the care profession, some nurses-to-be are trained to use stethoscopes, too. In the researched anaesthesia ward, nurses are obliged to carry one with them. Some nurses see the trend that nurses increasingly make clinical assessments and make decisions critically because this increases their responsibilities but not their status or their wages. Furthermore, physicians officially still hold the responsibility; nurses who are involved in clinical assessment and decision-making act without a corresponding legal framework (female nursing teacher, informal conversation 2019). As a male emergency nurse told us, he and his peers would not wear a stethoscope around their necks like the physicians, but they put them in the side pockets of their work clothes instead, signalling that they compete neither with the physicians nor other nurses who are not trained with stethoscopes (shadowing 2018).

The stethoscope gap has not only professional but also personal effects. An assistant physician in his late thirties noticed that his physician colleagues saw having nurses as friends as unusual (Interview 2018). In the anaesthesia and emergency wards we researched, nurses and physicians have common events twice a year. In contrast to the care wards, they also share a break room – an institutional marker to promote collaboration across professions.

Mutual personal and professional respect between nurses and physicians is highly important in the collaboration between the two professions (Tang et al. Citation2013, 298–299); respect is an issue of daily negotiation for both sides. A senior female physician in her late thirties explained that in her time as an assistant, she had to hold her ground vis-à-vis the older nurses, at least at the beginning. The more familiar she became with her nurse colleagues, the more they respected and appreciated each other’s work (interview 2018). A female nurse in her mid-thirties stated,

Of course, new assistant physicians do not yet know certain things. Sometimes, they have no clue what the nurses are doing. But if we have good arguments, we can convince them by insisting on our point. Basically, we are in power, even if they write the prescriptions. In the end, we can refuse to execute their orders if they are illogical. (Interview 2018)

Hierarchy serves as one of the main standardisation procedures in the hospital. Physicians are hierarchically superior to nurses and take the responsibility for treatments. But as the nurse above explains, new assistant physicians who have just finished their university studies need the support of the nurses, as they are not trained enough in practical work. The standardisation processes of hierarchy are therefore also altered where necessary by differentiation.

The collaboration of physicians and nurses is further challenged by the rotating systems for assistant physicians. In the researched anaesthesia ward, the nurses train new assistant physicians in operating the machines during the first two months. After that time of go-along, the assistant physicians immediately become in charge, such as when it comes to prescribing medication. This can lead to tension between mostly older nurses and mostly younger assistant physicians, especially when new assistants cause delays in the workflow due to their lack of experience. These frequent rotations are especially high in the researched emergency ward, where job training increases the overall workload and takes away time at the patient’s bedside. Those results also bring to light that what are understood as formal qualifications do not necessarily capture daily working realities. General indicators must be unpacked in order to understand what ‘expert knowledge’ really consists of (see also Landolt and Thieme Citation2018).

For assistant physicians, the shift between being a medical student and working as an assistant physician is tough; they are often thrown into the deep end. Nevertheless, with increasing work routine and deepening medical knowledge, the hierarchies evolve, and they take on the lead. In this potential area of conflict tactfulness, sensitivity, patience, and social skills are required from the nurses and the physicians as negotiation skills – not an easy task in the hectic hospital routine.

Furthermore, although nurses take a lot of responsibility for patients and physicians-in-training, systemically inherent inequalities concerning wage, prestige, and promotion prospects persist. The physicians often follow the given path from assistant physician to different levels of senior physician, but the opportunities for nurses to advance their careers are scarce with the possibility to become an expert nurse, an instructor for nurses in training, or a ward manager, but decreasing interaction with the patients.

The relationship between nurses and physicians is in the process of shifting towards collaboration on more equal footing and mutual respect – not least a result of the trend to flatten the hierarchies within hospitals – but some struggle with and oppose those changes (Tang et al. Citation2013, 299–300). In the researched institution, the competences and importance of the nurses’ work are widely acknowledged. However, some physicians still consider the nurses to be in a serving role. A senior, foreign-trained physician, for example, told a nurse to translate his words for a patient, even though an assistant physician who spoke the patient’s language was also present. The involved nurse later heavily complained to her colleague, asking why the senior physician did not ask the assistant physician for translation, but rather degraded her as a nurse once again in a ‘serving role’ as translator (shadowing 2018).

This example shows the general tendency of a specific prospect of the care profession that still seems to pop up from time to time. Generally, we spotted a lack of appreciation towards the responsible care profession manifested in lower wages, but also in the invisibility of the nursing profession and its agents in the public and within institutions. Although the image of the physician as a clearly male, omniscient demigod in white with a stethoscope and of the nurse as the clearly female subservient person are criticised as outdated and stereotyped, they are sometimes ironically but also insistently used in everyday work exchanges. As a result, they assert assumed and implicit ascriptions of status and prestige and how they are socially legitimised through wages.

Bruno, a male senior physician in his late thirties, and Barbara, a female anaesthesia nurse in her late twenties, work hand in hand. Bruno uses Barbara’s pink stethoscope to check on the patient, as he does not have his stethoscope at hand. ‘Is it contagious?’ he jokingly asks her, hinting to the stethoscope’s colour. Later, Bruno is unable to fix a small tube at the female patient’s cheek due to the make-up on her face. ‘I cannot remove her make-up. I am not responsible for such things. Can you do that?’ Bruno asks his female colleague. (Shadowing 2018)

While the differentiation we discuss points towards changes in the system, within and between the professions, there remain hard-to-change images and stereotypes that underpin these negotiations constantly. Unthinkingly, jokes such as the ones in this example point to fundamental inequality structures and reflect how the nurse–physician collaboration is still powerfully influenced by gender, position, and age (Hughes and Fitzpatrick Citation2010).

At the same time, the institution aims for differentiation to achieve a highly specialized work force. In addition, differentiation in the training of nurses also ensures that specialized training which also results in higher wages is only requested for specialized units, thereby reducing costs. Hospitals counter this increasing differentiation by various strategies of standardization. We discussed the strategy of hierarchy as defining decision-making power. Other strategies are the definition of procedures or checklists such as ‘team time-outs’ before an operation, when a printed list of necessary clarifications is checked point by point in the team to ensure all necessary information is available and procedures are completed before the beginning of an operation.

Concluding remarks

We started our argument by describing the interrelatedness of two processes, namely differentiation – as the process of increasing social differences that characterize the health labour force – and standardisation – as the process the hospital implements to ensure safe, stable treatment procedures. With regard to differentiation, we state first that while research on the healthcare sector has so far mainly focussed on single categories of difference such as gender, education, or migration, an intersectional analysis is necessary. Second, we show that these axes of difference intersect in manifold and complex ways, resulting in powerful negotiations. Third, insights into the daily working routines of physicians and nurses revealed that generic definitions and formal categories such as qualification must be unpacked. For example, day-to-day routines demonstrate the many roles and responsibilities senior nurses take on, such as the training of assistant physicians, by relying on long-term work experiences and gut feelings.

Importantly, differentiation does not only take place between professional groups but also within. Specifically, we have seen that among nurses, age, education, and, to an extent, gender and place of education are currently the most important social differences. Hospitals must thus ensure a balanced mix of age distribution, qualifications, and work experiences across teams and deal with questions of how to retain, for example, more senior employees and guarantee their job-related well-being – especially in times of a severe staff shortage. As hospitals heavily rely on staff from different generations and with various educational paths, hospitals must integrate staff with different qualifications, work experiences, and attitudes.

For physicians who are more hierarchically organised than nurses, gender, position, and, in part, place of education heavily impact their daily interactions. In collaboration between nurses and physicians, major inequalities persist, although recent changes counteract those tendencies – especially in Switzerland, where the hierarchies tend to be flatter than in neighbouring countries. One important difference between the professions is their promotion prospects. While the potential to climb the hierarchical ladder is inherent for physicians working in hospitals, nurses who occupy leadership positions generally do not do much bedside work. Thus, their promotions entail giving up at least parts of their original profession. Physicians in chief positions, in contrast, still regularly interact with patients, even getting the most interesting cases.

Hospital management and chief physicians argue that physicians can hardly work less than 80% (i.e. part-time) because of patient continuity, contrary to nursing, in which part-time work has always prevailed due to the high proportion of women. Even though the professions are less segmented in terms of gender (more men are becoming nurses, and many more women are becoming physicians), the stereotypical gender arguments still prevail. The nursing profession is still read as female, family-oriented, and therefore compatible with part-time work, while male nurses represent an exception. Female physicians, while standing for a new working identity in the profession, represent an exception to a profession read as male, career-oriented, and therefore linked to an even more than full-time commitment.

These differences are not only socially translated into power geometries but have a functional reason, as tasks must be distributed and responsibility assumed, because in a hospital, human lives are always at stake. The standardisation principles we describe do not only counter differentiation in the labour force, but rather use the resulting profit for the efficient and stable functioning of a hospital. Differences in power translate into a hierarchy of responsibility, distribution of tasks, and wage differentials that are relevant for individuals as well as the hospital’s budgeting. At the same time, certain elements bridge these differences: Nurses and physicians are able to talk on equal standing about imminent anaesthesia, and there exist checklists for many procedures that need to be carried out in a standardised and secure manner – independently from an individual’s knowledge, skills, and experiences. The hospital’s staff skillfully juggles the divergent processes of differentiation and standardisation to combine their advantages and ensure the institution functions well. Finally, power geometries are always experienced and reinforce various social differences and their interplay. In short, we argue for more research along the methodological premises of institutional ethnography with a focus on the complex and intertwined intersectionality of social differences.

Of great interest in our research was the motivation of hospital management to let us be part of their daily work. We have presented the results to the hospital management as well as staff of the three researched wards in separate meetings, and we were invited to publish our findings in the hospital’s newsletter. While potential practical applications of these findings remain, the hospital’s interest in our research indicates an interest in reflecting on inequalities and increasing their understanding of complexities and power relations.

Our findings show the persistence of power geometries based on various intersecting social differences. Despite changes and shifts in numbers, the main hierarchical problems still prevail: There are increasing numbers of women entering medicine, but the leading positions are still mostly male-dominated, and the percentage is not really changing. While there are slowly more men entering nursing, they support the female-oriented caring and serving stereotype of nurses in terms of ascending to leading positions and taking over management tasks that distance them from daily interaction at the patient’s bedside. These differences are not based solely on gender, but the intersectional analysis has shown that alliances and separations can build along various differences. A shift in numbers and percentages does not suffice to change the socially founded powerful structures. Differentiation also leads to a fragmented staff in which diverse interests in terms of generation, gender, place of education, or work identity have to be integrated into an institution like a hospital.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the foundation Homo Liberalis for the financing of the research project ‘Employment and Social Differences in the Swiss Health Care Sector’. We thank Luisa Genovese and Rosa Felicitas Philipp for transcribing the interviews. We are grateful for the helpful comments of four anonymous reviewers on earlier versions of this article. Special thanks go to the hospital’s CEO and the participating employees for providing us access and participating in our research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carole Ammann

Carole Ammann is a social anthropologist and currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Amsterdam Institute of Social Science Research (AISSR) at the University of Amsterdam. She researches and has published on gender, intersectionality, anthropological methods, everyday life, and agency in West Africa, Switzerland, and in the Netherlands.

Julia Mall

Julia Mall holds an MA in psychology from the University of Basel. She has been involved in this project as an assistant at the Institute of Geography at the University of Bern.

Marina Richter

Marina Richter (geographer and sociologist) is an assistant professor for Social Space and Social Work at the University of Applied Sciences, HES-SO, Valais, in Switzerland. She has extensively worked on social difference and inequality, social space, institutional approaches to social problems, transnationalism and prison studies.

Susan Thieme

Susan Thieme is professor for Geography and Critical Sustainability Studies at the Institute of Geography at the University of Bern. She has researched on a variety of topics, such as sustainability, globalisation im/mobility, migration, media related methods, employment, education, and youth in Nepal, India, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Switzerland.

References

- Aiken, Linda H., Jeannie P. Cimiotti, Douglas M. Sloane, Herbert L. Smith, Linda Flynn, and Donna F. Neff. 2011. “The Effects of Nurse Staffing and Nurse Education on Patient Deaths in Hospitals with Different Nurse Work Environments.” Medical Care 49 (12): 1047–1053. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NNA.0000420390.87789.67.

- Aluttis, Christoph, Tewabech Bishaw, and Martina W. Frank. 2014. “The Workforce for Health in a Globalized Context-Global Shortages and International Migration.” Global Health Action 7 (1): 23611. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23611.

- Ammann, Carole, Marina Richter, and Susan Thieme. 2020. “Analytical and Methodological Disruptions: Implication of an Institutional Ethnography in a Swiss Acute Hospita.” ZDfm – Zeitschrift Für Diversitätsforschung Und -Management 5 (1-2020): 71–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.3224/zdfm.v5i1.08.

- Bilge, Sirma. 2013. “Intersectionality Undone: Saving Intersectionality from Feminist Intersectionality Studies.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 10 (2): 405–424.

- Billo, Emily, and Alison Mountz. 2016. “For Institutional Ethnography: Geographical Approaches to Institutions and the Everyday.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (2): 199–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515572269.

- Bonds, Anne. 2013. “Racing Economic Geography: The Place of Race in Economic Geography.” Geography Compass 7 (6): 398–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12049.

- Bonnet, Alastair, and Anoop Nayak. 2003. “Cultural Geographies of Racialization – the Territory of Race.” In Handbook of Cultural Geography, edited by Kay Anderson, Mona Domosh, Steve Pile, and Nigel Thrift, 300–312. London, UK: Sage.

- Bradby, Hannah. 2014. “International Medical Migration: A Critical Conceptual Review of the Global Movements of Doctors and Nurses.” Health (London, England: 1997) 18 (6): 580–596. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459314524803.

- Braunschweig, Sabine, and Denise Francillon. 2010. Professionelle Werte pflegen. 100 Jahre SBK [Caring for Professional Values. 100 Years SBK]. Zürich: Chronos Verlag.

- Brown, Stefanie, and Daniela Holderegger. 2017. “Neue Rollen, neue Fertigkeiten, neue Perspektiven” [New Roles, New Skills, New Perspectives].” Clinicum 17 (1): 88–91. Accessed 2 November 2020. https://www.clinicum.ch/images/getFile?t=ausgabe_artikel&f=dokument&id=1481.

- Bundesamt für Statistik. 2015. Spitalpersonal 2013 [Hospital Personnel 2013]. Accessed 4 September 2020. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/gesundheitswesen/spitaeler/infrastruktur-beschaeftigung-finanzen.assetdetail.350276.html.

- Bundesamt für Statistik. 2016. Unbezahlte Arbeit 2016 [Unpaid Work 2016]. Accessed 4 September 2020. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken/medienmitteilungen.assetdetail.2967878.html.

- Casanova, James, Ken Day, Denice Dorpat, Bryan Hendricks, Luann Theis, and Shirley Wiesmann. 2007. “Nurse-Physician Work Relations and Role Expectations.” JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 37 (2): 68–70.

- Cho, Sumi, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, and Leslie McCall. 2013. “Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38 (4): 785–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/669608.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Sociology 41 (1): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142.

- Connell, John. 2010. Migration and the Globalisation of Health Care. The Health Worker Exodus? Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Cottingham, Marci D. 2017. “Caring Moments and Their Men: Masculine Emotion Practice in Nursing.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies, 12 (3–4): 270–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2017.1312954.

- Cottingham, Marci D., Rebecca J. Erickson, and James M. Diefendorff. 2015. “Examining Men’s Status Shield and Status Bonus: How Gender Frames the Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction of Nurses.” Sex Roles 72 (7–8): 377–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0419-z.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence against Women of Colour.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299.

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2012. “Organization Theory Meets Anthropology: A Story of an Encounter.” Journal of Business Anthropology 1 (1): 118–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.22439/jba.v1i1.3549.

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2014. “Why I Think Shadowing is the Best Field Technique in Management and Organization Studies.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 9 (1): 90–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-02-2014-1198.

- Davis, Kathy. 2008. “Intersectionality as Buzzword. A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful.” Feminist Theory 9 (1): 67–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700108086364.

- Devault, Marjorie L. 2006. “Introduction: What is Institutional Ethnography?” Social Problems 53 (3): 294–298.

- Dubois, Carl-Ardy, and Debbie Singh. 2009. “From Staff-Mix to Skill-Mix and beyond: Towards a Systemic Approach to Health Workforce Management.” Human Resources for Health 7 (87): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-87.

- Edmunds, Laurel D., Pavel V. Ovseiko, Sasha Shepperd, Trisha Greenhalgh, Peggy Frith, Nia W. Roberts, Linda H. Pololi, and Alastair M. Buchan. 2016. “Why Do Women Choose or Reject Careers in Academic Medicine? A Narrative Review of Empirical Evidence.” Lancet (London, England) 388 (10062): 2948–2958. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736. (15)01091-0.

- Freund, Tobias, Christine Everett, Peter Griffiths, Catherine Hudon, Lucio Naccarella, and Miranda Laurant. 2015. “Skill Mix, Roles and Remuneration in the Primary Care Workforce: Who Are the Healthcare Professionals in the Primary Care Teams across the World?” International Journal of Nursing Studies 52 (3): 727–743. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.014.

- Gill, Rebecca, Joshua Barbour, and Marleah Dean. 2014. “Shadowing in/as Work: Ten Recommendations for Shadowing Fieldwork Practice.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 9 (1): 69–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-09-2012-1100.

- Gilliat-Ray, Sophie. 2011. “‘Being There’: The Experience of Shadowing a British Muslim Hospital Chaplain.” Qualitative Research 11 (5): 469–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111413223.

- Gkiouleka, Anna, Tim Huijts, Jason Beckfield, and Clare Bambra. 2018. “Understanding the Micro and Macro Politics of Health: Inequalities, Intersectionality & Institutions - A Research Agenda.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 200: 92–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.025.

- Hendrix, Ulla, Heike Mauer, and Jennifer Niegel. 2019. “Karrierehindernis Geschlecht? Zum Verbleib von Frauen in der Hochschulmedizin.” [Career Obstacle Gender? On the Retention of Women in University Medicine] GENDER – Zeitschrift Für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesellschaft 11 (1-2019): 47–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.3224/gender.v11i1.04.

- Hopkins, Peter. 2019. “Social Geography I: Intersectionality.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (5): 937–947. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517743677.

- Hopkins, Peter. 2018. “Feminist Geographies and Intersectionality.” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (4): 585–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1460331.

- Hopkins, Peter, and Greg Noble. 2009. “Masculinities in Place: Situated Identities, Relations and Intersectionality.” Social & Cultural Geography 10 (8): 811–819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360903305817.

- Horisberger, Kathy. 2013. “‘Das Management muss Funktionen und Leistungsauftrag klar definieren’: Interview mit Monika Schäfer” [‘Management Must Clearly Define Functions and Performance Mandate’: Interview with Monika Schäfer].” Competence 77 (4): 10–11. Accessed 4 September 2020. https://www.careum-bildungszentrum.ch/files/media/files/839a5c670b6bac7782c091c6a89518d2/Das_Management_muss_Funktionen_und_Leistungsauftrag_klar_definieren.pdf.

- Hostettler, Stefanie, and Esther Kraft. 2013. “FMH-Ärztestatistik 2013. 31858 Ärztinnen und Ärzte garantieren die ärztliche Versorgung” [FMH Physicians’ Statistics 2013. 31858 Physicians Guarantee Medical Care].” Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 94 (12): 453–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/saez.2013.01467.

- Hostettler, Stefanie, and Esther Kraft. 2018. “FMH-Ärztestatistik 2018. Wenig Frauen in Kaderpositionen” [FMH Physicians’ Statistics 2013. Few Women in Management Positions.] Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 100 (12): 411–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/saez.2019.17687.

- Hughes, Barbara, and Joyce J. Fitzpatrick. 2010. “Nurse-Physician Collaboration in an Acute Care Community Hospital.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 24 (6): 625–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903550804.

- Jamieson, Isabel, Ray Kirk, and Cathy Andrew. 2013. “Work-Life Balance: What Generation Y Nurses Want.” Nurse Leader 11 (3): 36–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2013.01.010.

- Johnston, Lynda. 2018. “Intersectional Feminist and Queer Geographies: A View from ‘Down-Under’.” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (4): 554–564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1460329.

- Kingma, Mireille. 2006. Nurses on the Move: Migration and the Global Health Care Economy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Universiy Press.

- Kraft, Esther, and Martina Hersperger. 2009. “Ärzteschaft in der Schweiz – Die Feminisierung der Medizin.” [Medical Profession in Switzerland - The Feminisation of Medicine] Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 90 (47): 1823–1825.

- Labonté, Ronald, and David Stuckler. 2016. “The Rise of Neoliberalism: How Bad Economics Imperils Health and What to Do about It.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 70 (3): 312–318. https://jech.bmj.com/content/70/3/312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206295.

- Landolt, Sara, and Susan Thieme. 2018. “Highly Skilled Migrants Entering the Labour Market: Experiences and Strategies in the Contested Field of Overqualification and Skills Mismatch.” Geoforum 90: 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.01.009.

- Lee, Sandy. 2019. “Power, Performance and Place: A Feminist Analysis of Encounters in the Professional Workplace.” Gender, Place & Culture 26 (5): 762–766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1552123.

- Lindeke, Linda L., and Ann M. Sieckert. 2005. “Nurse-Physician Workplace Collaboration.” Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 10 (1): 5. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/499268.

- Lindsay, Sally. 2005. “The Feminization of the Physician Assistant Profession.” Women & Health 41 (4): 37–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v41n04_03.

- Long, Debbi, Cynthia Hunter, and Sjaak van der Geest. 2008. “When the Field is a Ward or a Clinic: Hospital Ethnography.” Anthropology & Medicine 15 (2): 71–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470802121844.

- Massey, Doreen. 1999. “Power-Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place.” In Mapping the Futures. Local Cultures, Global Change, edited by Jon Bird, Barry Curtis, Tim Putnam, George Roberson, and Lisa Tickner, 59–69. London, UK: Routledge.

- McDonald, Seonaidh, and Barbara Simpson. 2014. “Shadowing Research in Organizations: The Methodological Debates.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 9 (1): 3–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-02-2014-1204.

- McDowell, Linda. 2008. “Thinking through Work: Complex Inequalities, Constructions, of Difference and Trans-National Migrants.” Progress in Human Geography 32 (4): 491–507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507088116.

- McDowell, Linda. 2009. Working Bodies: Interactive Service Employment and Workplace Identities. Malden, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Merçay, Clémence, Laila Burla, and Marcel Widmer. 2016. “Gesundheitspersonal in der Schweiz. Bestandesaufnahme und Prognosen bis 2030” [Healthcare Personnel in Switzerland. Stocktaking and Forecasts Until 2030]. Obsan Bericht (71): 1–97. Accessed 4 September 2020 https://www.obsan.admin.ch/sites/default/files/publications/2017/obsan_71_bericht_korr.pdf.

- Merçay, Clémence, and Annette Grünig. 2016. “Pflegepersonal in der Schweiz − Zukünftiger Bedarf bis 2030 und die Folgen für den Nachwuchsbedarf” [Nursing Staff in Switzerland − Future Needs up to 2030 and the Consequences for the Demand for Young Professionals]. Obsan Bulletin (12): 1–4. Accessed 4 September 2020. https://www.obsan.admin.ch/sites/default/files/publications/2016/obsan_bulletin_2016-12_d.pdf.

- Mollett, Sharlene, and Caroline Faria. 2018. “The Spatialities of Intersectional Thinking: Fashioning Feminist Geographic Future.” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (4): 565–577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1454404.

- Nadai, Eva. 2012. “Von Fällen und Formularen: Ethnographie von Sozialarbeitspraxis im institutionellen Kontext” [Of Cases and Forms: Ethnography of Social Work Practice in an Institutional Context]. In Kritisches Forschen in Der Sozialen Arbeit, edited by Elke Schimpf and Johannes Stehr, 149–163. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-94022-9_9.

- Pöhner, Ralph. 2018. “Ärzte: Wie war das mit der 50-Stunden-Woche?” [Physicians: What was that about the 50-hour Week?]. In Medinside, January 8. https://www.medinside.ch/de/post/aerzte-wie-war-das-mit-der-50-stunden-woche.

- Prescott, Megan, and Mark Nichter. 2014. “Transnational Nurse Migration: Future Directions for Medical Anthropological Research.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) (107): 113–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.026.

- Quinlan, Elizabeth. 2009. “The ‘Actualities’ of Knowledge Work: An Institutional Ethnography of Multi-Disciplinary Primary Health Care Teams.” Sociology of Health & Illness 31 (5): 625–641. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01167.x.

- Reimann, Swantje, and Dorothee Alfermann. 2018. “Female Doctors in Conflict: How Gendering Processes in German Hospitals Influence Female Physicians’ Careers.” Gender Issues 35 (1): 52–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-017-9186-9.

- Riska, Elianne. 2008. “The Feminization Thesis: Discourses on Gender and Medicine.” NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 16 (1): 3–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740701885691.

- Rodó-de-Zárate, Maria, and Mireia Baylina. 2018. “Intersectionality in Feminist Geographies.” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (4): 547–553. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1453489.

- Salem, Sara. 2018. “Intersectionality and Its Discontents: Intersectionality as Traveling Theory.” European Journal of Women's Studies 25 (4): 403–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506816643999.

- Schueller-Weidekamm, Claudia, and Alexandra Kautzky-Willer. 2012. “Challenges of Work-Life Balance for Women Physicians/Mothers Working in Leadership Positions.” Gender Medicine. Official Journal of the Partnership for Gender-Specific Medicine at Columbia University 9 (4): 244–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genm.2012.04.002.

- Smith, Dorothy E. 1987. The Everyday World as Problematic: A Feminist Sociology. Boston, NY: Northeastern University Press.

- Smith, Dorothy E. 1990. The Conceptual Practices of Power: A Feminist Sociology of Knowledge. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Smith, Dorothy E. 2005. Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Smith, Dorothy E., ed. 2006. Institutional Ethnography as Practice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Tang, C. J., S. W. Chan, W. T. Zhou, and S. Y. Liaw. 2013. “Collaboration between Hospital Physicians and Nurses: An Integrated Literature Review.” International Nursing Review 60 (3): 291–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12034.

- Thomas, Eric J., J. Bryan Sexton, and Robert L. Helmreich. 2003. “Discrepant Attitudes about Teamwork among Critical Care Nurses and Physicians.” Critical Care Medicine 31 (3): 956–959. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000056183.89175.76.

- Timmermans, Stefan, and Steven Epstein. 2010. “A World of Standards but Not a Standard World: Toward a Sociology of Standards and Standardization.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 69–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102629.

- Vaiou, Dina. 2018. “Intersectionality: Old and New Endeavours?” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (4): 578–584. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1460330.

- Valentine, Gill. 2007. “Theorizing and Researching Intersectionality: A Challenge for Feminist Geography.” The Professional Geographer 59 (1): 10–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00587.x.

- van Eckert, S., U. Gaidys, and C. R. Martin. 2012. “Self-Esteem among German Nurses: Does Academic Education Make a Difference?” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 19 (10): 903–910. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01862.x.

- Weaver, Sallie J., Sydney M. Dy, and Michael A. Rosen. 2014. “Team-Training in Healthcare: A Narrative Synthesis of the Literature.” BMJ Quality & Safety 23 (5): 359–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001848.

- Wright, Ursula T. 2003. “Institutional Ethnography: A Tool for Merging Research and Practice.” Paper presented at the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, Columbus, Ohio, October 243–249.