Abstract

From 2009 to 2018, social attitudes towards gender in the UK and other western countries significantly shifted, with greater awareness of gender stereotyping and the objectification of women’s bodies in the media due to popular social media campaigns. Arguably, postfeminism has provided a channel in which tropes traditionally critiqued by feminism, such as the objectification or stereotyping of the female body, are appropriated by consumption, and reconceptualised as empowering forms of femininity. In two phases, this study explores if and how this social shift has been translated into how men and women’s bodies are presented to male and female audiences, respectively, by magazines that claim to represent and reflect them. Firstly, content of the front covers from six popular men’s and women’s magazines was analysed to identify the framing, clothing, and staging of the body. A second phase adds further novelty to this study by employing a cultural analytics approach to explore the relationship between gender and hue by analysing the brightness, saturation and hue values of each image. The findings show some continuities in how men and women are presented, despite significant changes in which magazines presented these continuities. Furthermore, the colour attributes of the images underlined significant differences in how men and women are presented for viewing. It is argued that these continuities and changes represent a reinforcement of patriarchal gendered relations (including gendered associations with specific colours) re-imagined through a postfeminist logic.

Introduction

In 2009, The Sun, the best-selling newspaper in the UK, printed a near-naked photo of a woman, usually in her late teens or early twenties, on its page 3 on a near-daily basis. This was a ‘tradition’ of the paper for over 40 years until 2015. There was no equivalent male body imaged in this way, and the photo would be captioned with a regular ‘News in Briefs’ speech bubble, in which the model’s view on a topical news story would be reduced to a short, superficial sentence, ironically acknowledging the perceived incongruity between a mostly-naked model and intelligent opinion. Fast-forward to 2018 and this casualisation of female nudity already seems archaic and wholly inappropriate for a top-selling newspaper. This paper investigates the presentation of gender in the media, specifically men’s and women’s magazines published between 2009 and 2018. The paper draws on a visual content analysis of the front covers of women’s magazines (Cosmopolitan, Glamour and Marie Claire) and men’s magazines (FHM, Esquire and GQ) to investigate the presentation of bodies (male and female) in terms of clothing and framing. It also draws on a cultural analytics (Manovich Citation2009) approach to explore relationships between the publication’s audience, gender and the hue, brightness and saturation of the images. The findings demonstrate a significant shift in men’s magazines away from presenting (and objectifying) female models for a male audience but additionally a converse shift in women’s magazines towards more scantily clad female models. There are also correlations in the use of specific hues in line with gendered stereotypes.

#Metoo, #EverydaySexism, No More Page 3, Let toys be toys. The 2010s have seen numerous different campaigns, often with social media resources, call attention to how women and their bodies are objectified, marginalised and harassed in a misogynistic society. During the same period, public attitudes in the UK have increasingly become influenced by these critical voices with the British Social Attitudes survey evidencing noticeable shifts in rejection of traditional gender roles and gendered comments on appearance (Attler Taylor and Scott Citation2018). From having negative associations a decade or so ago, ‘feminism’ has become not just acceptable but even celebrated in popular culture and consumption with celebrities, film stars, high profile corporate executives and neoliberal women and branded events promoting themselves with this movement (Chidgey Citation2020; Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020; Windels et al. Citation2020). After a lengthy campaign from ‘No More Page 3’, early 2015 saw the final topless model on Page 3. By 2016, men’s magazines or ‘lads’ magz’ such as FHM, Loaded, Zoo and Nuts, that regularly featured semi-naked women on the front cover also collapsed. As well as wider shifts in public attitudes, the cessation of semi-nude female models in men’s magazines is also possibly due to the availability of free, nude and pornographic images, as well as other content (for example, sports news or sexist humour), on websites typically targeted at male heterosexual audience.

Since the mid-1990s, it is argued that feminism can incorporate sexualisation of the female body, including that which takes place for heterosexual male visual consumption, as a mechanism to reclaim the body from the objectification of the male gaze. In this postfeminist ‘sensibility’ (Gill Citation2007) popularised by female pop groups, models and celebrities, women’s bodies can both be presented as ‘sexy’ and ‘empowered’. Yet there is debate whether this is a practice of resistance to the objectification of women or a neoliberal appropriation of feminist ‘empowerment’ discourse for commercial purposes that regardless fulfils the ‘male gaze’ (Gill Citation2012). Along with these shifts, colour has often been re-appropriated to perform gender through this postfeminist movement in more both implicit and explicit ways.

This paper’s findings reflect an increasing articulation of what Gill (Citation2007; Citation2012) conceptualises as ‘postfeminism’ in UK public discourse. It is this field of gender and feminist studies which is discussed next to contextualise the argument, before an outline of previous studies of magazines and discussion of hue and gender roles. Methods are then presented before a discussion of the findings. In line with the emerging field of ‘geographies of colour’ (Edensor Citation2019), this paper will also demonstrate the value of thinking about colours as an affective agent of structural power in gender.

The (visual) performance of gender and postfeminism

Geographers have long focussed on the relationship between gender and embodiment with particular attention paid to the somewhat contradictory attitudes towards the female body, its materiality and ‘messiness’ (Rose Citation1993; Longhurst Citation2005; Gill Citation2007; Longhurst and Johnston Citation2014). The construction of hierarchical male-female binaries and associations of gender, particularly of male with the mind, the rational and transcendent, and female with the body, the irrational and material have similarly been critically engaged with by geographers (Rose Citation1993; Longhurst Citation2005). Butler (Citation1993) draws on Foucault’s (Citation1977) notion of regulatory practice and disciplining the docile body to produce or ‘perform’ gendered roles. Gender is re-produced through embodied practices, from gestures to the way people walk to the clothes people wear as they align themselves with established codes of conduct which invite discipline upon their transgression. Gendered performance is inherently political, being complexified by entanglements with race, sexuality, class, (dis)ability and age. While identity is often seen as a self-defined set of conditions and characteristics, its definition is discursive and socially constructed, underpinned by structural, ideological apparatuses (Hopkins Citation2018). This framework renders gender a messy category, within which some bodies are ‘unmarked’ – positioned as the standard, neutral (Haraway Citation1988) – in opposition to ‘marked’ bodies, thus unequally positioned – marginalised.

The past decade has seen an increased interest in feminism, either as a political and philosophical standpoint or as a fashionable identity label. This increase, arguably fuelled by the surge in internet connectivity and social media access rates, is often understood as the break of a fourth wave in feminism (Rampton Citation2008). The fourth wave inherits third wave’s battles for intersectional inclusion and reclaiming of female sexuality while expanding those topics with the help of new information and communication technologies. From the early 1990s, second wave feminism was increasingly viewed as restricting the capacity of women to be seen by men and themselves as glamorous or exciting (McRobbie Citation2004; Windels et al. Citation2020). In this context, postfeminism emerged as a (nevertheless disputed – see McRobbie Citation2004; Householder Citation2015; Gill Citation2016; Rivers Citation2017) critique to a certain unidimensional approach to perceived feminist cultural trends that are unequivocally entangled with enduring inequalities related to other identity markers, and strengthened (if not employed) by dominant structures such as neoliberalism (Gill Citation2016).

New representation of female role models emerged that combined social and career success with traditional tropes of femininity. In this sense, postfeminism is not opposed to the waves model, neither is it a position or perspective in itself, but rather a ‘critical object’ (Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020) for interrogation of the contradictions at the heart of cultural products and movements. In this context, postfeminist critiques of the so-called fourth wave point out to the weakening (or outright distortion) of foundational feminist theories by the neoliberal power structuring cultural production and consumption (Householder Citation2015; Chidgey Citation2020). Being ‘sexy’ and ‘glamourous’ are also possible under this new postfeminist logic, as sites of female exploitation (men’s magazines photoshoots) become reinterpreted as career-enhancing opportunities.

The female body continued to be at the centre of postfeminism, no less so than in visual cultures (Gill Citation2007, Citation2012), but the subjective celebration of sexuality and gender is presented often conforms to objective standards or regulations of beauty and (often male-orientated) desire. Media images and representations situate women in ‘girly’ or sexualised roles, but with a degree of control in their situation. Such depictions, Gill asserts, are not passively consumed by a docile audience but critically engaged with by a socially aware user-base. Arguing postfeminism in the media as a ‘sensibility’, Gill argues, the ‘sexy’ female body is celebrated as empowered in a more sexualised culture where images of the undressed female body are widely available for consumption. The male gaze of the sexualised culture is internalised; women become the consumers or owners and responsible for their own sexually liberated bodies (Gill Citation2007, Citation2012; Martin Citation2016; Windels et al. Citation2020). Postfeminism in this reading is a co-location of traditionally feminist and anti-feminist discourse, and Jackson, Vares, and Gill (Citation2013, 145) draw scepticism to this notion, arguing that:

[…] feminist arguments for choice, independence and agency have been appropriated and commodified in the marketing of goods to women. Within this consumer discourse, women and girls are positioned as powerful citizens where shopping for girlie products such as clothes and shoes assumes status as an expression of empowered choice.

The sexualisation or degree of nudity of women in the media is thus reinterpreted as a movement within feminism of re-claiming and expression of the self, rather than presented for male visual consumption. Yet the presentation of ‘postfeminist’ consumables and the models often deployed to sell them, for the most part conform to a narrow set of bodily ideals that are thin, white, young and heterosexual without the messiness of real bodies and neglect intersectional or structural challenges by framing feminism as neo-liberal, individualist journey of transformation rather than of societal change (Baer Citation2016; Martin Citation2016; Windels et al. Citation2020).

Even body positive movements of the last 10–15 years that have pushed for media and marketing to reflect more diverse body types are underpinned by postfeminist sensibilities. Notably the idea of an individual ‘empowerment’ being attainable through self-love and consumption of products that can lead to self-transformation (Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020; Darwin and Miller Citation2020; Windels et al. Citation2020). However, the body positive movement also draws specific modes of acceptability (Sastre Citation2014) which prescribe new, overarching normativities where it pledged to dismantle normativity (Darwin Citation2017). In this sense, the changes propelled by the body positive movement cannot be seen as simply emancipatory, for they are as regulated and regulatory (through neoliberal ideals) as the cultures preceding them. The next section will discuss how the sexualisation of women and their self-expression in the media is translated in preceding studies of magazines and gender.

New lads and cosmo girls: gender in magazines

There are numerous studies of how gender and the body are presented in magazines. Whether focused on fashion, health or general lifestyle, magazines provide some indication of what is expected of gender roles for the audience, as to buy the magazine is to show some level of empathy for those people and lifestyles featured within their pages. Yet, this project did not find any studies that focused on the presentation of gender, during what is arguably one of the most significant shifts in social attitudes towards gender as observed over the last ten years.

It is important to note that mainstream lifestyle magazines (as does mass media) play several roles in capitalism, one of them being the assertion and reinforcement of the gender roles and relations sustaining it (McDowell Citation2004; R. W. Connell Citation2008; Farías Citation2016; Savage Citation2017; Lachover Citation2020; Kam Citation2020). Significantly the cultural logic of the 1990s brought a new visual culture in men’s magazines. Rebelling against the ‘new man’ culture of the 1980s, the ‘new lad’ culture magazines such as FHM, Loaded, Zoo and Nuts of the 1990s signalled an emphasis on stereotypically male or ‘lad’ interests: football, violence as entertainment, political incorrectness and pictures of semi-naked female models and celebrities wrapped up in an irony-laden discourse that deflected accusations of sexism (Gill Citation2007; Stevenson, Jackson, and Brooks Citation2000; Evans Citation2015). This trend was noted in the US market as well, with Lambiase and Reichert (Citation2005) arguing that the appearance of Maxim magazine in 1996, forced its American competitors Esquire and GQ into increasing the deployment of female models on the front cover. Whilst men featured on 75% of these covers in 1996, by 2000 this share had reduced to 44%.

Analysing the content of men and women’s health magazines published between 2006 and 2011, Bazzini et al. (Citation2015) find that the images and captions conform with a notion of self-discipline and self-objectification of the body. Significantly both sets of magazines promoted particular types of bodies as desirable to both genders. For men, this was a muscular body whereas for women this was thinner body, with the female models usually featuring less clothing in the images than their male counterparts (Bazzini et al. Citation2015; see also Lambiase and Reichert Citation2005). A more recent study of ‘adultification’ and ‘youthfication’ of girls and women in US lifestyle magazines found a trend of ‘imposing’ sexuality on younger female models by dressing them to appear older (Gerding Speno and Aubrey Citation2018). Although they found little evidence that adult women are sexualised by making them appear younger, when this does occur it appears of a more niche, or in the authors’ words ‘fetishistic’, avenue of visual culture (Gerding Speno and Aubrey Citation2018).

These issues resonate with Gill’s notion of postfeminism whereby the body is re-claimed and becomes an object of empowerment rather than marginalisation. Sypeck, Gray, and Ahrens (Citation2004) take a more critical view of their findings from a content analysis of the front covers of women’s magazines in the USA from 1959 to 1999. Their study shows a trend towards thinner and thinner models – and a gradual change of shot frame from close-ups, emphasising the importance of a ‘pretty face’ to a thin, desirable body. Saraceno and Tambling (Citation2013) in their study of Cosmopolitan images from 2009, similarly find women being portrayed in a way that implies idealised beauty and objectification. Additionally, they find that male models tend to conform to ‘hegemonic masculine’ (Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005) ideals and roles as part of an overall heteronormative discourse.

Introduced by Connell (Citation1995), ‘hegemonic masculinity’ draws on Gramsci’s notion of hegemony to identify the structural and cultural apparatus that emphasises a particular set of values attributed to masculinity. Primarily the masculine hegemony normalised, culturally rather than statistically, as white, heterosexual, strong and dominant amongst other ‘masculine’ ideals (Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005). Much of this masculine stereotype is exemplified in the ‘New Lad’ and men’s magazines of the 1990s and 2000s, which regularly featured semi-naked female models, stories of violence, drinking and cars presented with a deliberate use of irony that enabled some deflection of these masculine attributes as sexist (Stevenson, Jackson, and Brooks Citation2000). The more upmarket varieties, such as Esquire and GQ featured in this research, mixed these masculine elements (most often, semi-naked female models) with more traditionally ‘feminine’ elements such as fashion and health. Boni (Citation2002) notes that with the growth of titles such as Men’s Health in the late 1990s and early 2000s, male bodies became increasingly medicalised and consumed by a male audience and, inferring Foucault’s docile body concept, becoming ‘feminised’ as men become the target of advertisers for health and beauty products. This feminisation occurs in the sense that the male body becomes objectified and open to manipulation. However, according to Boni (Citation2002) these advertisers must ‘legitimise’ their products by relating them to traditional male stereotypes – such as muscular male torsos or emotionally impenetrable eyes.

Notably, gendered magazines have drawn upon traditional social constructions of men and women. Some studies have identified developments in how these constructions are re-calibrated through the postfeminist lens or resisting certain aspects of hegemonic masculinity. The net result, however, often looks similar to the original starting point: men are strong and dominant; women are objectified and ‘girly’. Contrasting with the ubiquity of models of hegemonic masculinity and emphasised femininity, the invisibility of queer and non-conforming bodies in the magazine covers is both a symptom and a tool for fulfilling patriarchal and neoliberal constructions of gender and sexuality (Hasinoff Citation2009; Leopeng and Langa Citation2020). The covers, and the narratives and languages attached to them are binary because this is how these products were designed in the first place. The studies above were often undertaken in a relatively stabilised period regarding social attitudes to gender. Departing from these studies, the research in this paper investigates if the construction of gendered visual performances has shifted during a period (2009–2018) in which gender norms have been challenged and increasingly subject to re-evaluation in wider public discourse. As well as the presentation of models, the current research also considers the extent to which colour, a typically neglected but affectual component of imagery in this context contributes to the social construction of gender in the visual culture of these magazines.

Colour and gender

The association between gender stereotyping and hue or colour is firmly established and can be seen regularly in everyday life, most notably in the deployment of blue to signify boys/men and pink for girls/women. Whilst colour has clear spatial consequences and is a key element of landscape, it has been largely overlooked in geography. A barrier to further interrogation are the limitations of language to describe colour, despite the human eye being able to discern between almost limitless different shades and hues (Gage Citation1993). According to Kandinsky ((1977) cited in Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2002), colour has both a direct value (the capacity to affect the viewer physically) and an associative value (a symbolic value).

At a session (Mobilising Colour in Geographical Research) at the Institute of Australian Geographers Conference 2019, Edensor (Citation2019) brought together a series of discussions of the affective qualities, place-associations and cultural values of colours. This may be the beginning of a new strand that addresses an overall neglected focus of colour within geographical literature. Of the few geographers who have engaged with colour, Tuan (Citation1974) draws on psychological and anthropological work (including that of Turner (Citation1967)) to discuss the symbolism of colour across a selection of different cultural contexts. In a Western context (as well as other contexts), there is a foundational division between white and black or light and dark. White symbolising purity, transcendence, divinity and life (the substances of milk or semen being representative of the generative power of white), whilst black can represent defilement, earthliness and death (Tuan Citation1974). Reds can represent energy (such as the vital substance of blood), the erotic, and danger. Colours take on textual couplings within descriptive terms such as ‘warm red’, ‘aqua frost’ or ‘earthy green’ (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2002).

Of course and as noted above, colour also becomes a distinctive identity marker of gender and sexuality. Pink is consistently linked to femininity and exposed to girls from an early age, as products such as toys and clothes marketed to girls, continuing through adulthood (e.g. underwear brands, and women-focused charities and events drawing heavily on pink) (Koller Citation2008; Hughes and Wyatt Citation2015; Martin Citation2016; Jonauskaite et al. Citation2019). Yet the association of pink and femininity is relatively recent; pink was also a colour for boys in the West until the 1920s (Koller Citation2008; Jonauskaite et al. Citation2019). In recent decades, blue has come to symbolise masculinity, partially through its employment by traditionally male-dominated professions such as policing and the Navy (Koller Citation2008; Jonauskaite et al. Citation2019) and corporate brands (eg. the blues of Facebook or IBM logos). These gendered binaries of colour become so strong in the 20th century that the combination of male and pink came to signify homosexuality and gay movements or associations. Nevertheless, although normative, the binary use of colour is far from the only model; colour use is constantly questioned and stretched by queer people, who have historically disused and reused colours (among other symbols) to challenge oppression (Ahmed Citation2018; Kotlarczyk Citation2019). Within a postfeminist context (Koller Citation2008; Gill Citation2007, Citation2012; Hughes and Wyatt Citation2015), pink becomes a more complicated symbol as both a quality which can be patronising (such as the marketing of traditionally masculine products such as cars or DIY power tools) or empowering as a marker of female and feminist identity. The use of colour by the individual and organisations, consciously or unconsciously, can, therefore, be a performance in identity, as Butler (Citation1993) conceptualises; the user employs specific colours to promote or hide certain aspects of their identity.

Colour or hue become further complicated with the addition of brightness, modulation and saturation that can have distinct affect and effects on the power and consumption of colour. Koller (Citation2008) notes that lighter, or whiter, shades of pink add to the innocence and femininity of the colour, whilst the darker shades of red or blue employed by Rothko have a distinct haunting affect on the viewer. Going further than thinking of colour as a signifier in flattened terms, Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2006) create a sophisticated framework for the analysis of colour as a key component of images. This framework comprises domains of value (brightness); saturation (intensity of colour); purity (range of colours); modulation (texture of colour from ‘flat’ to use of different shades); differentiation (of colours within the image) and; hue. These domains work together to add realness (or a sense of the hyper-real via oversaturation, for example) and distribute authority to different parts of the image or invest authority into the image as a whole. They can add or remove energy and movement from the picture via purity, differentiation or modulation as well as add symbolic associative value. This paper draws on these understandings of colour to investigate if the traditional deployments of hue in relation to gender and the presentation of gender continue through the period from 2009 to 2018, when awareness of such tropes was raised in public consciousness.

Methods

Millions of images of bodies are available online so why study magazines? The editorial control involved with magazine publications regarding who is featured and how they are presented demonstrates intentionality as well as the expectation of what the target audience will respond to and resonate with. The front cover of a magazine is arguably the most significant image a magazine can publish as it has to target a specific and core audience of regular readers – reflecting something that resonates with this audience – as well as compete on the front line for more casual readers whose loyalty – and money – may be tempted by rival publications. The front cover must also be acceptable to non-readers, other people who may be passing by the magazine rack or browsing for other images. The values of the magazine – and how these are communicated – must be compatible with the cultural environment in which the image is likely to be displayed. Therefore, how bodies are presented on the front cover of a magazine reflects the values, the attitudes of a society – or its potential to accept new values and change its attitudes – and included in this culture are the expectations of gender.

The selection of magazines was straightforward – six of the most popularly circulated ‘lifestyle’ magazines in the UK. provides a snapshot overview of the magazines, their circulation figures (for both print and digital editions) and images from 2014 – the most recent year when all six magazines featured due to FHM’s demise in 2016. The front covers were sourced from a variety of websites with the majority of images coming from the magazine’s own websites or various magazine subscription websites. With some images from the 2009–2018 dataset missing from these sources, some searching and retrieving of specific front covers was made using Google Images. Despite these efforts, there were still 19 front cover images that proved impossible to track down; however, with 657 images in the total dataset, this constitutes less than 3% of the issues published during the 2009–2018 period.

Table 1. Magazine circulation figures and available images in dataset. Source: Press Gazette (Ponsford, 2014).

Content coding

Eleven different coding categories were created (although not all appear in this paper), ranging from categories based on demographics such as the number, gender, visible race and estimated age of the models in the cover, to categories based on characteristics such as dress and emotion. The demographic categories relied on some interpretation. Visible race, for instance, was necessarily broad in its codes due to the difficulties of identifying heritage, particularly due to well-known instances of using airbrushing software to make models with darker skin appear lighter in tone.

‘Dress’ was both significant and difficult to codify in certain images. Coverage and clothing of the body is important to investigate its presentation, but this on occasion can be a grey area. Two separate codes were set up: ‘dress – cover’ and ‘dress – style’ (e.g. a model may be wearing a swimsuit, and due to the framing be mostly covered). Alternatively, the model might be wearing a casual, oversized jumper but nothing underneath, she (and this was invariably ‘she’) would be classified as wearing ‘casual’ clothing but also ‘partially dressed’. The two codes allowed for these issues to be registered; other codes explore how the body is being framed and presented physically for the viewer. For instance, is the body being fully shown (a full shot) or just the face being shown (close-up).

A final note on coding here is to discuss the researcher positionality. In this study, the coders were a white-British male and a black-Latina female, which enabled a variety of perspectives and gazes. The combination of backgrounds enabled different aspects of body and identity to be recognised and discussed during pre- and post-coding discussion.

Cultural analytics

Before the mass-availability of internet access, keeping track of cultural change was relatively easier due to the centralisation (and perceived authoritative sources) of cultural objects in museums, art galleries, studios and publishers that were concentrated in major cities such as London, New York, Paris, Mumbai or São Paulo. With developments in Web 2.0, vast amounts of data are uploaded every minute on to websites and social media sites such as YouTube, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Such dizzying developments led some to question and explore how cultural change could be tracked using computing technology to process large datasets (Manovich Citation2009).

Cultural analytics draws together a wide range of approaches and research interests to interrogate digitally encoded or stored datasets, exploring how societal changes are evidenced and reflected in cultural products: media, art, literature, graphics, music or archival data. The Software Studies Initiative has utilised computing power to trace changes in visual cultures of magazine publications, expressionist and modern art, ‘selfies’, videogames, political broadcasts and more (see Software Studies Initiative (2016) for a full list of projects). The value of this approach is that it helps to understand the construction of the image as a cultural product of distribution and consumption. As Manovich explains:

When we look at images normally, we experience all their visual dimensions at once. When we separate these dimensions using digital image analysis and visualization, we break this gestalt experience. (Manovich Citation2012, 276)

Further work following Manovich has analysed the visuality of smart cities, with Rose and Willis (Citation2019) drawing attention to the trends of their sample of images posted on Twitter that use strongly blue or orange hues, reflecting cultural values of images claiming to represent ‘smart cities’. As well as analysis of visual content of our dataset of magazine covers, cultural analytics approach also informs the second phase of this paper and it is an ideal vehicle for exploring the relationship between colour and gender presented here. Whilst our dataset is smaller than that used by many of the Software Studies Initiative projects, the analysis here uses the tools (notably ImageJ and PlotImage programmes) to analyse the image values of brightness, saturation and hue to interrogate the data for divergences in how male and female models are visualised.

Findings

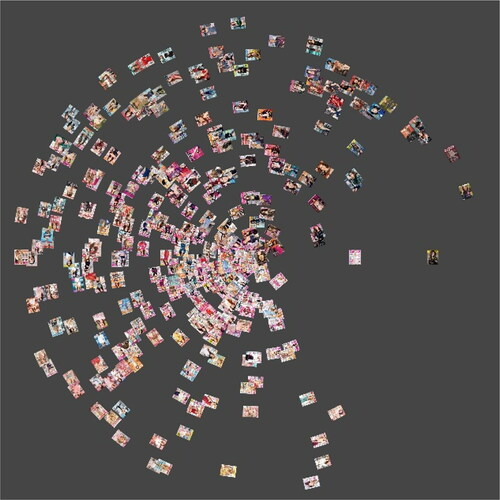

display the initial breakdown, by gender, of the sample. The most significant shift here is of the decline of using female models for the covers of men’s magazines. Esquire and GQ both begin in 2009 using female models for a significant proportion of their covers, but from 2012 onwards there is a distinct downward trend and shift towards using male models. FHM provides an exception here with only a few male models through its entire run. The women’s magazines almost exclusively feature female models only. As seen in the figures, unlike FHM (which only begins to diversify from female-only models and incorporate male celebrities late in its lifecycle), both Esquire and GQ increasingly deploy male front covers. Although it is important to highlight that queerness is not always visible, since they do not necessarily add to visual representations of gender, queer bodies seem entirely absent in the analysed period.

Figure 1. (a) Percentage of front covers who are female by year and publication. (b) Percentage of front covers who are male by year and publication.

This shift away from depicting the sexualised female body was not without some controversy. García-Favaro and Gill (Citation2016) report in their discourse analysis of comments from mainstream news websites responding to the Co-Operative Supermarket’s decision to censor female models on ‘lads magz’. Their analysis showed a perceived threat to male (hetero)sexuality by the removal of this viewing pleasure. The pattern evidenced in though, along with FHM’s subsequent demise in 2016, suggests that Co-Op was aligned with popular opinion in this debate. This controversy illustrates the ongoing antagonism between a symbolic power shift entailed by perceived progressive feminist practices and the defence of the patriarchal structures of (hetero)sexism in the shape of the use of women’s bodies for the male gaze.

Age and ethnicity

Although not the central focus of this study, ethnicity is central to identity. Visible ethnicity was a more difficult category to code, especially as the authors detected some lightening of skin tones on occasion which served to confuse identification from the visual material alone. Given this, it is estimated as shows that the vast majority (nearly four-fifths) of models featured were identified as white, with models of mixed heritage, black or other ethnicities making up 19.5%. Although a much larger proportion of the models were classified here as white, this figure (78.4%) roughly corresponds with the overall population of England and Wales (Office for National Statistics Citation2018); the distribution of Black and Ethnic Minority categories do deviate, most notably with an over-representation of mixed heritage models.

Table 2. Visible ethnicity of models by gender.

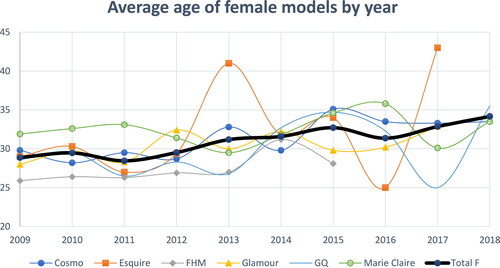

For the most part, the dominance of white-ethnicity models limits meaningful interrogations of intersectional identities, with the exception of ‘Framing’ discussed below, as the coded variables were often similar in pattern. The publications are targeted at younger readers, typically between 18 and 40 years in age. It is therefore not too surprising that most of the models fall within this age range, as the reader should identify with the model in order to be interested in purchasing the magazine. Yet as detailed below, there were some older models. The results in demonstrate this but additionally evidence a much wider age range of male models in men’s magazines.

Table 3. Average age of cover model by publication, gender and year. Please note Cosmopolitan did not feature any covers with only male models. Glamour and Marie Claire featured a maximum one male model per year.

This is further evidenced by the Standard Deviation measurement for all years combined that is larger, identifying greater variation in the data range of age, for men than for women. The dataset of male models features much older cover stars such as Michael Caine and Clint Eastwood (both famous for acting particularly masculine character roles), who at time of publication were 81 and 79 years old respectively. Indeed, whilst there were 19 male cover models 60 years or older recorded, the oldest female cover star was actor Julianne Moore who was 55 years old at the time of her Marie Claire appearance in March 2016. Finally, out of the 79 models over the age of 45, just 17 are female.

Despite the overall tendency for younger female models with less age diversity than is the case with male models, also identifies a general trend amongst all publications for older female models by 2018. FHM notably has both the youngest mean age for female models and one of the least varied range of ages. As a men’s magazine linked with the ‘New Lad’ culture of the 1990s, this lack of variety and convergence in picturing younger female models typifies the male gaze of these magazines and re-produces a desired body type for its readership.

Framing

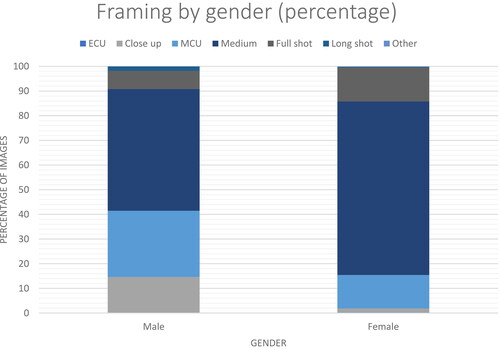

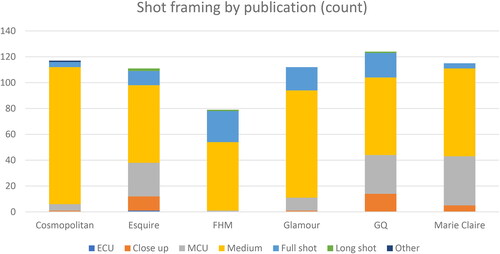

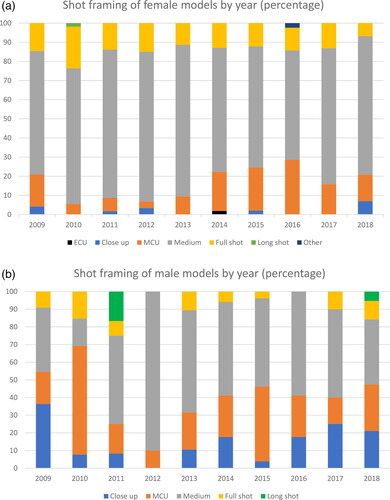

The framing of the body or how much of the body was presented also revealed significant differences in how men and women were pictured. The inference being that bodies are more central to a woman’s visibility and identity, whereas close-up of men’s faces emphasis their intellectual quality; a reproduction of gendered associations of men and women more widely (see Rose Citation1993 for discussion of gendered binaries). As can be seen in , 85% of images with female models were presented in full shot, ¾ (from the knees or mid-thigh upwards) or medium shot (from the waist upwards). In comparison, 56% of male models were presented in full, ¾ or medium shots framing, whilst 41% of their images were either close-up (of the face) or extreme close-up (part of the face). 15% of female models were pictured in close-up or extreme close-up. When ethnicity was cross-tabulated, the findings suggested a slightly greater tendency for models from a black or ethnic minority background being framed with a full, ¾ or medium shot (84%) than for models of white ethnicity (77%).

suggests that the female body is regularly presented for a male audience or ‘gaze’; however, reveals a more nuanced picture. FHM, which almost exclusively featured female models on the front cover does indeed solely rely on ¾/medium or full shots (with a few long shots) that display the full body of the (usually scantily-clad) model, and this is true for the majority of images featuring women in Esquire and GQ. A trend which is also apparent in Lambiase and Reichert (Citation2005) study of Esquire and GQ in the late 1990s. Yet this is also the case for Glamour, Marie Claire and particularly Cosmopolitan, all of which employ female models for the vast majority of their front covers. In presenting women’s body to an expected female readership, these publications reinforce gendered associations of women with the material, the body and a sexuality performed for the male gaze (as elaborated on in the following section). Furthermore, the female body here performs a femininity in its full presentation yet this also resonates with postfeminist arguments (Gill Citation2007, Citation2012) that the body is reclaimed for a female readership, particularly as we see a decline of female models being employed by men’s magazines in this period.

This trend may be slowly changing as the year by year story in reveals that, after an initial slide in favour of fuller shot frames, there is a slight shift towards Medium Close-Ups (MCU) of female models. Marie Claire and Glamour, especially, move more towards MCUs and Close-Ups of their models from the mid-2010s whilst conversely in this dataset Cosmopolitan, initially begins with predominantly Close-Ups but from mid-2010s onwards uses mostly ¾ shots that display the body from the knees upwards as standard.

Meanwhile, due to the overall smaller sample of front covers with male models, a pattern is less apparent in . Shot framing is more varied for these covers with a much greater likelihood of Close-Ups or MCUs being employed in these photographs, particularly from 2013 onwards.

Clothing and coverage

illustrates the discrepancy between how male and female bodies are presented in the images. Notably, women regularly appear in much more revealing or tighter clothing than men. Although a significant factor is that the men’s magazines predominantly feature women in underwear or swimwear, it should also be noted that several of the women’s magazines additionally present women in swimwear or revealing outfits.

Table 4. Dress coverage of models by gender.

Again, this trend reinforces traditional notions of performance of gender with female models wearing more revealing clothes, in both men’s and women’s magazines (Butler Citation1993; Gill Citation2012). That there is such a strong continuation of this trend reinforces the argument that such images are constituted to draw attention to, and sexualise, the female body (either as empowered or powerless). Although the majority of female models conformed to ‘traditional’ bodily standards and characteristics, Cosmopolitan’s (October 2018) inclusion of plus size model Tess Holliday is an exception that resonates with the ‘body positive’ movements.

Hue and gendered bodies

A simple visual comparison of (showing all magazine covers featuring female models) and (all covers featuring male models) reveals a different aesthetic trend in hue for each gender.

Whilst there are three times as many images featuring females than those with males, the two Figures still demonstrate a significantly wider distribution of female images around the hue wheel (a standardised method of presenting colour and lightness in a 360-degree circular chart). Noticeably the gravity of the images in is weighted towards brighter, whiter images. The cause of the whiter visual effect are the lighter shades of hue deployed across the three women’s magazines, a significant proportion of these covers feature white backgrounds against which the model stands. Lighter shades here signify the innocent and feminine (Koller Citation2008). Indeed, on one particular front cover (March 2014) of FHM, a ‘youthified’ model is pictured against a light pink is background to create a garish and creepy scene. Even when the background is not white, the hue employed is usually a lighter (or brighter), pastel shade. When women are featured on the front cover of men’s magazines (as in ), darker and more saturated hues are employed. Notably red becomes a more apparent colour feature.

Figure 7. (a) Female models on the front covers of men’s magazines. (b) Male models on the front covers of men’s magazines.

Equally, displays the front covers of men’s magazines from this sample that feature male models. These covers are altogether darker, as also evidenced when looking at the brightness median of all images in . In this reading where 0 is completely black or dark, and 255 is completely white or maximum brightness, images with male models have a brightness median value of 145 compared with 199 for females.

Table 5. Hue, brightness, saturation and RGB values.

This can be observed in and , where these images are darker and occupy a much cooler area of the hue wheel. Images featuring male models are 53 degrees earlier on the hue wheel than images depicting females. This in percentage terms represents a 25% increase between the genders which is enough to differentiate between the cyan-blue hue mean of male images and blue/violet-magenta hue mean of female images. In visual terms, this means that generally, images featuring men are more likely to appear blue, greyer or duller than the images featuring women. The images of male models, often featuring darker, cooler and bluer hues, present a more serious tone and association to the cover stars - a signal of the authority of the cover star to the reader.

When looking at how women appear on the front covers of women’s magazine (), there is a similar range as to when women are featured on men’s magazines. However, the visual weighting draws on the lighter and more pastel shades of the backgrounds. Women’s magazines present female models with a more traditionally ‘feminine’ colour range of whiter and lighter shades, that promote a more ‘innocent’ or ‘pure’ form of femininity.

The backgrounds of women’s magazine covers, therefore, help to perform a particular version of femininity in these images across the sample. The men’s magazine covers that feature female models have a stronger trend towards darker and more heavily saturated images. The higher the saturation value, the more it is associated with a state of hyper-reality (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2006), where the image takes on a greater or deeper level of reality as the colours begin to bleed out from the image. The reds become more apparent (along with a more diverse spread of hue used throughout this subsample), which along with the saturation emphasises the sensuality and sexuality of the images. The front covers of men’s magazines in this sample are inviting the reader to view the female model as a sexualised body.

Yet there is also a slow but steady shift in the women’s magazine subsample. As this subsample progresses through the years, the covers become darker and more saturated reflecting a transition towards a more self-conscious presentation of female models towards an expected female audience. This is significant because it resonates with the shift towards postfeminism that Gill (Citation2007, Citation2012) describes, as women in these magazines become more open towards sexualisation as part of an empowerment exercise. The innocence, the immature pastel shades and whites are replaced by the vibrant and saturated hues of maturity.

Conclusion

This study has revealed significant shifts in the presentation of gender during the period from 2009 to 2018, yet also continuities in the outcomes of these shifts. Most visible has been amongst the men’s magazines. Whilst all three titles sampled here regularly (and in the case of FHM, solely) depicted the female body sexualised by the style (or lack) of clothing and the posing of the body in 2009, by 2018 this had become greatly reduced in frequency. Indeed, the inability of FHM to move away from its diet of scantily-clad women as a core component of its brand identity is cited as one of several factors sealing its demise in the mid-2010s (J. Jackson Citation2015). Yet during this period, women’s magazines begin to employ lesser clothed female models for their covers (albeit with less overt sexualisation present). The ‘celebration of white male heterosexuality’ (Stevenson, Jackson, and Brooks Citation2000, 371) in ‘lads magz’ becomes a celebration of white female sexuality in women’s magazines. Overall, the magazines of this sample demonstrated a continuation of tropes in how men and women are presented for visual consumption. Although the average age of female models did increase across most publications, the gap between the average ages of women and men who featured on the front covers was substantial. Furthermore, female models were much more likely to be only partially clothed with their bodies pictured nearly fully.

Significantly, however, this paper has drawn attention – and calls for further geographic investigation – into the relationship between gender and colour or hue. The study here has explored the overall visual effect of hue as well as the digital analysis in terms of hue, saturation and lightness values. Much of the results are predictable with female models associated with lighter, traditionally ‘feminine’ hues such as white, pinks, magentas as well as eroticised colours such as reds. Male models, by contrast, were associated with cooler, darker and bluer hues suggestive of more serious and authoritative tones. This conformation to established gender norms (pink for female, blue for male) evidences a subtle yet stubborn refusal for change in attitudes and associations, even in the wake of an increasing visibility of queer questionings and reclamations of colour in the recent years. On this point, it should be noted a more recent issue of Cosmopolitan (January 2020) that falls just outside of the sample, featured cover model Jonathan Van Ness. Significantly, Van Ness, a star of the TV series Queer Eye and the first non-female cover model, combines the masculinity of facial hair with the feminine dress of peach-coloured ballgown that demonstrates the magazine’s engagement with more complex gender categorisations.

More obvious differences between the presentation of men and women (notably revealing photos of the latter in men’s magazines) have been challenged, modified or complicated through postfeminist shifts, yet the less explicit, ambient structures of colour remain. This is important for two reasons. Firstly, such colour schemas play upon social constructions of gender with men in authoritative, more serious and less emotionally-stimulating associations whereas as women remain within a problematic mess of sexualisation and innocence which attends to and reinforces core attributes of emphasised femininity (Connell Citation1987) which are central to patriarchal gendered relations. Secondly, certain colours (especially pink) might be employed in self-aware, assertive reclamation or otherwise ironic renderings in a postfeminist context, however for the person quickly browsing or passing by the newsstand (or its digital equivalent), these colours are likely to only reinforce pre-existing patriarchal associations of gender.

There are many different ways of seeing colour and expressing its role and impact in producing social life. By addressing mainstream uses of hue as a communication device in popular media, this paper has contributed towards filling a gap in geographical studies of colour and its crucial role in the production of place. This paper demonstrated that, when looked from a gendered perspective, geographies of colour contribute to wider discussions of normativity and defiance – thus of power relations – and the nuanced ways these are expressed visually through fashion and mainstream media. Moreover, the added sensitivity of a postfeminist analysis places normativity within the wider context of late capitalism. In this sense colour or hue is another tool for co-opting as well as responding to agendas and advancements of the association of gender with particular characteristics such as the cooler blues or greys to signal authority or whites and pinks to suggest innocence and purity. When these colours or hues are used (often as background ambience) in relation with gender, they create social and cultural meanings and invitations to which their audiences respond. Colour is employed in the process of assertion or defiance of gendered norms, overflowing the senses and immediately impacting how space is produced and lived across the gender spectrum.

Much of our findings suggest a postfeminist shift in the presentation of gender, particularly as women’s magazines depict female models more scantily clad, alongside non-normative bodies (e.g. overweight), as well as drawing on some of the bluer tones traditionally associated with masculinity. The postfeminist turn is not, therefore, totalising but has developed through specific patterns shaped by pre-existing trends the construction of gender for a consumer marketplace. The emphasis on the female body throughout the sample, as well as the greater range of age and framing given to male models, demonstrate that traditional values apply. Throughout this paper, the images sampled have demonstrated a complicated, gradually and non-uniform emergence of postfeminism in the visual culture of mainstream men’s and women’s magazines.

Acknowledgements

This project benefitted from funding for research assistance provided by the School of Archaeology, Geography and Environmental Science at the University of Reading. The authors would like to thank the editor and peer reviewers for their very helpful and constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Edward Wigley

Edward Wigley is a Staff Tutor in the Geography department at the Open University. After graduating with a PhD from UWE Bristol, he was a Post-Doctoral Research Associate on the ESRC-funded Smart Cities in the Making project based at the Open University. He has published research on religion and spirituality, urban geographies, teaching practice and folklore and heritage.

Vevila R. C. Dornelles

Vevila Dornelles was awarded a PhD in Human Geography by the University of Reading, UK, where she is currently a Postdoctoral Research Assistant. Her research addresses the dynamics of social exclusion, inclusion, and agency, with special focus on gendered relations, and their role in the production of digital spaces and spaces of the digital.

References

- Ahmed, Sarah. 2018. ‘Queer Use’. Blog. Feministkilljoys (blog). 8 November 2018. https://feministkilljoys.com/2018/11/08/queer-use/

- Attler Taylor, Eleanor, and Jacqueline Scott. 2018. “Gender.” In British Social Attitudes Survey 35, edited by Roger Harding. London: National Centre for Social Research. http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/latest-report/british-social-attitudes-35/gender.aspx

- Baer, Hester. 2016. “Redoing Feminism: Digital Activism, Body Politics, and Neoliberalism.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (1): 17–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1093070.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2020. “Postfeminism, Popular Feminism and Neoliberal Feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in Conversation.” Feminist Theory 21 (1): 3–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119842555.

- Bazzini, Doris, Amanda Pepper, Rebecca Swofford, and Karly Cochran. 2015. “How Healthy Are Health Magazines? A Comparative Content Analysis of Cover Captions and Images of Women’s and Men’s Health Magazine.” Sex Roles 72 (5-6): 198–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0456-2.

- Boni, Federico. 2002. “Framing Media Masculinities: Men’s Lifestyle Magazines and the Biopolitics of the Male Body.” European Journal of Communication 17 (4): 465–478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231020170040401.

- Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Chidgey, Red. 2020. “PostfeminismTM: Celebrity Feminism, Branding and the Performance of Activist Capital.” Feminist Media Studies, 1–17.

- Connell, Raewyn W., and Pearse, Rebecca, (2009), Gender, Cambridge, Polity.

- Connell, Raewyn W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19 (6): 829–859. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639.

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons.

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1995. Masculinities. Berkley and Los Angeles CA: University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520246980/masculinities

- Darwin, Helana. 2017. “The Pariah Femininity Hierarchy: Comparing White Women’s Body Hair and Fat Stigmas in the United States.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (1): 135–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1276889.

- Darwin, Helana, and Amara Miller. 2020. “Factions, Frames, and Postfeminism(s) in the Body Positive Movement.” Feminist Media Studies, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1736118.

- Edensor, Tim. 2019. ‘Considering a geography of colour’, paper presented at Institute of Australian Geographers Conference, Wrest Point Tasmania, 9th - 13th July.

- Evans, Adrienne. 2015. “Diversity in Gender and Visual Representation: A Commentary.” Journal of Gender Studies 24 (4): 473–479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2015.1047628.

- Farías, Mónica. 2016. “Women’s Magazines and Socioeconomic Change: Para Ti, Identity and Politics in Urban Argentina.” Gender, Place & Culture 23 (5): 607–623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2015.1034244.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punishment. London: Penguin.

- Gage, John. 1993. Colour and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. London: Thames and Hudson.

- García-Favaro, Laura, and Rosalind Gill. 2016. ““Emasculation Nation Has Arrived”: Sexism Rearticulated in Online Responses to Lose the Lads’ Mags Campaign.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (3): 379–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1105840.

- Gerding Speno, Ashton, and Jennifer Stevens Aubrey. 2018. “Sexualization, Youthification, and Adultification: A Content Analysis of Images of Girls and Women in Popular Magazines.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95 (3): 625–646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699017728918.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 147–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549407075898.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2012. “Media, Empowerment and the “Sexualization of Culture” Debate.” Sex Roles 66 (11-12): 736–745. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0107-1.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2016. “Postfeminism and the New Cultural Life of Feminism.” Diffraction (6): 8.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- Hasinoff, Amy Adele. 2009. “It’s Sociobiology.” Feminist Media Studies 9 (3): 267–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680770903068233.

- Hopkins, Peter. 2018. “Feminist Geographies and Intersectionality.” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (4): 585–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1460331.

- Householder, April Kalogeropoulos. 2015. “Girls, Grrrls, Girls: Lena Dunham, Girls, and the Contradictions of Fourth Wave Feminism.” In Feminist Theory and Pop Culture, edited by Adrienne Trier-Bieniek, 19–33. Springer.

- Hughes, Kate, and Donna Wyatt. 2015. “The Rise and Sprawl of Breast Cancer Pink: An Analysis.” Visual Studies 30 (3): 280–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2015.1017351.

- Jackson, Jasper. 2015. “FHM and Zoo Closures Mark End of Lads’ Mag Era.” The Guardian, 17 November 2015, sec. Media. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/nov/17/fhm-zoo-magazines-suspend-publication

- Jackson, Sue, T. Vares, and Rosalind Gill. 2013. ““The Whole Playboy Mansion Image”: Girls’ Fashioning and Fashioned Selves within a Postfeminist Culture.” Feminism & Psychology 23 (2): 143–162. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353511433790.

- Jonauskaite, Domicele, Nele Dael, Laetitia Chèvre, Betty Althaus, Alessandro Tremea, Laetitia Charalambides, and Christine Mohr. 2019. “Pink for Girls, Red for Boys, and Blue for Both Genders: Colour Preferences in Children and Adults.” Sex Roles 80 (9-10): 630–642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0955-z.

- Kam, Iris Chui Ping. 2020. “Being Bitchy and Feminine: Unfolding the Postfeminist Account in Hong Kong’s CosmoGirl!” Journal of Gender Studies 29 (4): 431–442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2019.1707075.

- Koller, Veronika. 2008. “‘Not Just a Colour’: Pink as a Gender and Sexuality Marker in Visual Communication.” Visual Communication 7 (4): 395–423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357208096209.

- Kotlarczyk, Abbra. 2019. ‘Queer Uses of Colour: A Tinted Hermeneutics’. Artlink Magazine, 1 March 2019. https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4740/queer-uses-of-colour-a-tinted-hermeneutics/

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2002. “Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour.” Visual Communication 1 (3): 343–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/147035720200100306.

- Kress, Gunther R., and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lachover, Einat. 2020. “Multiplicity of Feminisms: Discourse on Women’s Paid Work in the Popular Israeli Women’s Magazine La’isha during Second-Wave Feminism.” Feminist Media Studies, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1713839.

- Lambiase, Jacqueline, and Tom Reichert. 2005. “Sex and the Marketing of Contemporary Consumer Magazines: How Men’s Magazines Sexualized Their Covers to Compete with Maxim.” In Sex in Consumer Culture : The Erotic Content of Media and Marketing, edited by Tom Reichert and Jacqueline Lambiase, 67–86. New York: Routledge.

- Leopeng, Bertrand, and Malose Langa. 2020. “Destiny Overshadowed: Masculine Representations and Feminist Implications in a South African Men’s Magazine.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (5): 672–691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1599037.

- Longhurst, Robyn. 2005. “Situating Bodies.” In A Companion to Feminist Geography, edited by Lise Nelson and Joni Seager, 337–349. Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Longhurst, Robyn, and Lynda Johnston. 2014. “Bodies, Gender, Place and Culture: 21 Years On.” Gender, Place & Culture 21 (3): 267–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.897220.

- Manovich, Lev. 2009. Cultural Analytics: Visualizing Cultural Patterns in the Era of ‘More Media’ [online], Los Angeles CA, California Institute for Telecommunication and Information (Calit2). Available at http://manovich.net/content/04-projects/063-cultural-analytics-visualizing-cultural-patterns/60_article_2009.pdf (Accessed 24th February 2021).

- Manovich, Lev. 2012. “How to Compare One Million Images?.” In Understanding Digital Humanities, edited by David Berry, 249–278. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Martin, Amber. 2016. “Plastic Fantastic? Problematising Postfeminism in Erotic Retailing in England.” Gender, Place & Culture 23 (10): 1420–1431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1204994.

- McDowell, Linda. 2004. Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies. 1st ed. (Reprint). Minneapolis: John Wiley & Sons.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2004. “Post‐Feminism and Popular Culture.” Feminist Media Studies 4 (3): 255–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1468077042000309937.

- Office for National Statistics. 2018. “Population of England and Wales.” Office for National Statistics. 1 August 2018. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest

- Rampton, Martha. 2008. “Four Waves of Feminism.” Pacific Magazine. http://www.pacificu.edu/about-us/news-events/four-waves-feminism

- Rivers, Nicola. 2017. Postfeminism(s) and the Arrival of the Fourth Wave: Turning Tides. Cheltenham: Springer.

- Rose, Gillian. 1993. Feminism and Geography. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Rose, Gillian, and Alistair Willis. 2019. “Seeing the Smart City on Twitter: Colour and the Affective Territories of Becoming Smart.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (3): 411–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818771080.

- Saraceno, Michael J., and Tambling Rachel B. 2013. “The Sexy Issue: Visual Expressions of Heteronormativity and Gender Identities in Cosmopolitan Magazine.” Qualitative Report 18 (40): 1–18.

- Sastre, Alexandra. 2014. “Towards a Radical Body Positive: Reading the Online “Body Positive Movement”.” Feminist Media Studies 14 (6): 929–943. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2014.883420.

- Savage, Ann M. 2017. “Making Feminist Media: Third-Wave Magazines on the Cusp of the Digital Age.” Feminist Media Studies 17 (6): 1123–1125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1380435.

- Stevenson, Nick, Peter Jackson, and Kate Brooks. 2000. “The Politics of “New” Men’s Lifestyle Magazines.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 3 (3): 366–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/136754940000300301.

- Sypeck, Mia Foley, James J. Gray, and Anthony H. Ahrens. 2004. “No Longer Just a Pretty Face: Fashion Magazines' Depictions of Ideal Female Beauty from 1959 to 1999.” The International Journal of Eating Disorders 36 (3): 342–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20039.

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1974. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perceptions, Attitudes, and Values. Eaglewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Turner, Victor. 1967. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of the Ndembu Ritual. London: Cornell University Press.

- Windels, Kasey, Sara Champlin, Summer Shelton, Yvette Sterbenk, and Maddison Poteet. 2020. “Selling Feminism: How Female Empowerment Campaigns Employ Postfeminist Discourses.” Journal of Advertising 49 (1): 18–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1681035.