Abstract

In this article we develop the theoretical premise that platform companies are in the business of making markets from a gender perspective. We do so in relation to Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms which have emerged in a context of changing gender regimes. Concerns about women’s safety in public transport and recognition of women as a sizeable market-share has led one platform to build gender into its digital interface. For the other platform, gender is indirectly written into its digital design. The neat representation of gender as a bounded category at the level of the platforms’ digital interface obfuscates gender as a situated practice on and off the back of the motorbike. Analysing the placed performance of the platforms illuminates ways of doing gender necessary for (re)producing ride-sharing as a flexible and gendered good in a way that does not negatively affect women’s honour in Nepal’s conservative gender regime. We also flag potential gender based violence if actors’ main interests are different from or go beyond realising ridesharing as a gendered product.

When it comes to women, we are aware of how vulnerable it can be while using public transportation in Nepal. Tootle became a story of hope when we had about 50% of female clients in Tootle by 2018 (Excerpt from personal blog by one of Tootle’s founders: Koirala Citation2018)

Introduction

This article contributes to a growing body of scholarship on the gig economy in the Global South (Wood et al. Citation2019; Ford and Honan Citation2019; Pollio Citation2019). This work acknowledges that there are general features shared by platform companies comprising the global gig economy, but emphasises that such shared features can only tell part of the story of how the gig economy works. This has led to a call for an “interrogation of the “placed” performances of the platform” (Richardson Citation2020, 634).

In this article we respond to this call with a focus on gender in relation to Kathmandu’s motorbike and scooter-based ride-sharing platforms. A gender focus is important because for the current generation of young Nepali women in particular, these platforms offer the prospect of moving independently through the city and constitute an affordable alternative to a public transport system in which women especially feel unsafe (World Bank and AusAid Citation2013). The opening quote illustrates that the Kathmandu ride-sharing platforms engage with this reality. In line with feminist geographies, we complicate the platform’s account of ‘hope’ by bringing to the foreground women’s own stories about their experiences in Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms. Analytically we do so by teasing out the various ways in which platforms make ride-sharing markets gendered and how gender matters in the placed performance of ride-sharing as an everyday practice situated in Kathmandu’s shifting gender regime.

A focus on motorbike- and scooter based forms of ride-sharing is important. In the congested cities of the Global South and also in rural areas that are not serviced by public transport, it is motorbike transport rather than taxis that is the most common and most accessible form of commercial transport (Jenkins et al. Citation2020; Sopranzetti Citation2018; Truitt Citation2008; Yuana et al. Citation2019, 1155). Consequentially, over recent years so-called ‘ride-sharing’ or ‘ride-hailing’ platforms offering commercial motorbike transport have emerged, especially in the Asian region (e.g. Ford and Honan Citation2019; Turner and Hạnh Citation2019).

In the following section we describe Kathmandu’s gender regime and how it has changed over recent years. Next, we present a brief theoretical discussion of platform companies before we lay out the methodology underpinning this article. The analytical section follows a brief overview of the Kathmandu ride-sharing sector, focusing on how gender is an integral component in the making of markets of Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms. We then draw out the implications this has for ride-sharing as a gendered practice, including how it may render women vulnerable to potential gender-based violence.

Situating mobility in Kathmandu’s shifting gender regime

Nepal is a relatively small country in South Asia. Nonetheless, its social landscape is extremely varied in terms of ethnic, caste and class differences. Hence, there is substantial variation in how, precisely, gender relations shape the lived experiences of different groups of women (and men) in contemporary Nepal. Moreover, in urban areas of Nepal gender is increasingly shaped by generationed dynamics (Snellinger Citation2013, 80-82). Ethnographic studies conducted in Pokhara and Kathmandu have documented how young women are reworking dominant gender norms, for example, by taking up jobs in the formal economy, through mobility, and through consumption (Grossman-Thompson Citation2017; Brunson Citation2014; Liechty Citation2003).

Barbara Grossman-Thompson (Citation2017, 487) observes that “high-caste Hindu gender norms have remained culturally dominant” in post-revolutionary Nepal; “ideally a woman should practice relatively strict domestic seclusion through her life”. These conservative gender norms stand in friction with the aspirations of many young Nepali women who have come of age during and after the People Movement’s pro-democracy demonstrations and the Maoist insurgency of 1990s and 2000s. During this era, public space became a “legitimate place of social and political protest”, tangible achievements in terms of gender equality and women’s rights were realized, and democracy, freedom and rights became omni-present political discourses (Grossman-Thompson Citation2017, 487-8). In urban areas, the current generation of young women are often the first women in their families to have taken up formal employment. Consequentially, in contemporary urban Nepal young women navigate contradictory discourses: discourses of development and modernization urge young women to be mobile and to participate fully in various dimensions of public life, while the continued influence of high-caste Hindu gender norms mean that doing so too freely puts their ijaat (social honor) at risk (Grossman-Thompson Citation2017, 495, 502).

The interplay between changing gender regimes and broader social dynamics such as urbanization, globalization and the marketization of the economy is also analysed in Jan Brunson’s (Citation2014) work on Kathmandu’s “scooty girls”. Prior to the arrival of scooters, “Nepali women (of the class that could afford a motorcycle but not a car) could be seen on the backs of motorcycles driven by husbands, brothers, boyfriends, and male classmates and friends” (Brunson Citation2014, 610). Motorcycles are hard to operate in a dress or skirt, rendering driving one improper for Nepali women. The scooter’s design (especially its footrest) tackled this and aggressive marketing campaigns combined with young women’s desire for mobility independent of a male driver did the rest (Brunson Citation2014). The advent of the scooter in the Kathmandu valley allowed unmarried women to frequent sites of relative anonymity well-beyond the surveillance of their neighbourhoods (Brunson Citation2014, 626). Yet, similar to the women trekking guides studied by Grossman-Thompson (Citation2017), also Brunson’s scooty girls embraced these new-won freedoms with a concern about the reputational damage this might trigger by seeking “private moments of intimacy”, but exclusively in public spaces such a parks and nearby forests where others can stumble upon them at any time (Brunson Citation2014, 626).

Most young women in the Kathmandu valley are not part of households that can afford a scooter, or would need to share such a vehicle with other household members. Prior to the emergence of ride-sharing platforms, these less privileged young women relied on public transport to realise a degree of independent mobility. However, as the case in many other countries Nepal’s public transportation problems are for a good part gendered problems (Neupane and Chesney-Lind Citation2014). A survey conducted by the World Bank and AusAid (Citation2013) showed that overcrowding was experienced as the main problem among both men (70%) and women (80%). Overcrowded buses led women respondents to mention “personal insecurity” nearly twice as often as men (30% vs 16%) as one of “the main problems in taking public transport” (World Bank and AusAid Citation2013, 12). The survey breaks down the theme of personal insecurity into fear of pickpocketing, personal abuse and sexual harassment (i.e. inappropriate touching). With regard to the latter, the gender differences were stark: “43% of women aged 19-25 years noted insecurity as a problem…entirely due to fear and experience of inappropriate touching” (World Bank and AusAid Citation2013, 13).

Platforms and the making of markets

Nick Srnicek (Citation2017, 254) describes platform companies as “economic actors operating within a capitalist economy” using a business model that is “premised upon bringing different groups together”. For the Kathmandu ride-sharing platforms these groups are drivers and passengers. Alex Wood et al. (Citation2019, 57) further distinguish between platforms that transact and deliver work remotely (such as Amazon Mechanical Turk), and platforms in which work is transacted digitally but delivered locally such as food delivery platforms, couriering, and transport platforms.

Another analytical point emerging from recent work on the gig economy is that platform companies “are in the business of making markets” (Barratt, Goods, and Veen Citation2020, 1644). In contrast with temporary staffing firms, platform companies not just make labour markets they simultaneously make product markets (Barratt, Goods, and Veen Citation2020; Richardson Citation2020, 634; Wu et al. Citation2019). The making of these markets is realised through the coordination of heterogeneous actors (Barratt, Goods, and Veen Citation2020, 1644).

On the basis of research on the food delivery platform company Deliveroo in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom, Lizzie Richardson (Citation2020, 633) argues that we can approach the making of markets from two angles. There is the digital interface of the platform; “the on-screen representation of the perfect meeting of supply and demand through the platform” (Richardson Citation2020, 620). This representation of the market is an algorithmic realisation. Demand and supply are neatly bracketed; roles of actors as buyers and sellers are predetermined and the interface representation removes the “uncertainty of their coordination” (Richardson Citation2020, 620). Yet, there are “contingencies inherent to the algorithmic calculation” that need to be resolved through actual social interaction in order to realise the product as a “flexible arrangement” (Richardson Citation2020, 633). This latter approach to the making of markets requires “interrogation of the “placed” performances of the platform” (Richardson Citation2020, 634). This perspective is especially relevant for those platforms that transact work digitally but deliver it locally.

Studying the placed performance of platforms, means rejecting the idea of “straightforward notion of algorithmic control” and expanding the scope of study beyond a focus on the platform worker (Richardson Citation2020, 620). For Richardson (ibid), this meant studying contingent interactions between the various actors assembled in the flexible product of the delivered meal, and accounting for the differing degrees of choice they have about their participation. We take this theoretical exercise further by situating the actors (drivers, customers, platform representatives) and the contingent interactions studied within Kathmandu’s changing gender regime (Brunson Citation2014), and by illuminating the particular gendered anxieties this produces (Grossman-Thompson Citation2017).

In their making of markets, Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms seek to bend gender norms in a transport landscape that is already gendered in particular ways. At the level of the interface this objective appears accomplished in an unproblematic way. Yet, this leaves out of sight how gender is accomplished on and off the back of the motorbike as part and parcel of ridesharing as a situated, gendered practice including the vulnerabilities produced by making markets gendered.

Studying Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms

The primary research for this article was conducted for a thesis project carried out in the context of an MA in Development Studies by the first author (Hamal Citation2019). The first author is a Nepali national and based in Kathmandu. Since she was not born in the Kathmandu valley, the main language spoken in the Kathmandu valley (Newari) is not her mother tongue. Therefore, the interviews were conducted in Nepali and/or English. Not speaking Newari fluently did not appear a drawback. Field research took place in July and August 2019 taking the form of a mobile ethnography in two senses of the term. First, since ride-sharing is a mobile phenomenon fully comprehending it required getting out on the road and participate in the very practices that define it (see also Sopranzetti Citation2018; Truitt Citation2008; Hansen Citation2018). For this reason, the first author registered as a driver with the two ride-sharing platforms operating in Kathmandu (Tootle and Pathao) and also regularly used them as a paying customer. The second dimension of the mobile ethnography is that we studied carefully the digital architecture and the virtual interactions that comprise an important part of the sociality of these platforms (Postill and Pink Citation2012). This also allowed theorizing across the digital and material dimension of the platforms.

Since most drivers on ride-sharing platforms are men, the first author as a female Nepali national stood out among the drivers. This positionality brought to the foreground various gender dimensions of ride-sharing. For example, when the first author visited the Pathao office to complete her driver’s registration process, the (male) security guard was pleasantly surprised to see a young woman coming in and remarked: “You come to the office next time, I will introduce you to another female driver.” (fieldnotes, 11 July 2019). Similarly, a young woman (26 years) and her child who were among the first customers when the first author started riding for Tootle was also positively surprised to be picked up by a woman driver. This led her to ask many questions while she was seated on the back of the motorbike, such as: “How old are you, where do you live, do you have own house in Kathmandu, who do you live with, what do you do?” The first author managed to take the mother and child across a busy intersection that was in poor condition without asking the two to get off her scooter and walk. The woman customer was impressed and appreciative, and when the first author revealed her student-researcher identity the passenger shared that she, too, dreamt of doing a Master degree abroad. She said, it would be difficult to realise this dream because of her marital status. She also volunteered lots of information about her own and her mother-in-law’s experience with using the ride-sharing platforms and invited the first author to visit her and her mother-in-law to discuss things in more detail (fieldnotes 19 July 2019).

The first author’s participant observation on the two ride-sharing platforms provided a grounded basis for developing a loosely structured interview guide. A sample of interviewees were recruited through the first author’s presence on the platform. For this purpose, the first author carried business cards containing a brief description of the research project and her contact details. These business cards she would hand out at the end of a ride asking drivers or passengers whether they would be available for an interview to discuss their experiences in more detail. This way a total of 18 passengers were interviewed (9 men, 9 women), and a total of 20 drivers (18 men, 2 women). For the two women drivers the first author only succeeded in interviewing them through the chat function of Facebook messenger. The research ethics related to this project were discussed as part of a compulsory research design seminar part of the MA programme. The principle of ‘do no harm’ guided all stages of the research and translated in measures such as: ensuring informed consent, guaranteeing anonymity, respecting respondents’ wishes of not participating in the research, but also road-safety measures such as wearing good-quality helmets, driving safely and pausing the research on days when the road conditions of monsoon season Kathmandu demanded so (for further details on research ethics see: Hamal Citation2019).

The interviews ranged from in-depth discussions in cafes or restaurants to more casual and fleeting conversations on the back of the motorbike, depending on what was possible and appropriate. In some cases, respondents were interviewed multiple times, in other instances just once. This depended on respondents’ availability and interest in the topic. In most cases, drivers and passengers responded positively to an interview request but there were some declines too – which were respected. For example, the 26 year old woman passenger referred to above who had invited the first author for an in-depth interview with her and her mother-in-law cancelled this later without giving a clear reason. In all likelihood her mother-in-law had objected as the young woman herself had been very forthcoming with information and had insisted on the first author visiting their place for more discussion. A similar experience with a 29 year old male Tootle driver is worth recalling. The first author invited him for an interview at the end of a ride-share she had booked herself. The driver explained he had been driving for Tootle together with some friends since its start. He proposed the first author would meet them all for a group interview and he suggested a date. When the first author called him to confirm things he postponed the plan saying that “I am busy with driving, please call me later”. The first author received similar responses when she contacted the driver later before he eventually said that his friends weren’t comfortable with an interview because “they don’t want to share information with anyone” (fieldnotes 28 July 2019).

The primary data analysis is complemented with an analysis of secondary material comprising of reports from Nepali media about Tootle and Pathao from across the period that the platforms have been in operation in Nepal. Such material sheds light on the intentions and motivations behind the technological designs and social interactions we have studied.

Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms: a descriptive overview

In Nepal, the gig economy is a relatively new phenomenon and largely limited to urban locations. The meal delivery platform Foodmandu was launched in 2010 making it the oldest still operating platform. Foodmandu paved the way for various other platforms, including, Khalti, iPay and Esewa (platforms for online payment services), Aayoexpress (a platform for on-demand delivery), Chamkilo (a platform for laundry services) and the two ride-sharing platforms on which we focus in this article: Tootle and Pathao.

Tootle, a Nepali owned business, was launched in early 2017 and soon after, in 2018, the Bangladeshi owned company Pathao started operating services in Kathmandu too. Tootle and Pathao provided us with some basic data showing that as of mid-2019 Tootle had a pool of 31,813 registered drivers out of which less than four per cent (1,115) were women drivers. Pathao, had a pool of 25,000 drivers and even fewer women drivers (150). The underrepresentation of women drivers was reflected in our sample (only two women drivers), too, and in our data (various passengers expressed surprise when meeting the first author in her role as a woman driver). Grossman-Thompson (Citation2020, 875) work puts this in perspective by explaining that “taxis, hired cars, buses and microbuses are still overwhelming driven by men” in the Kathmandu context. The only exception to this pattern is the electric tempo, “small, open-backed vehicles that usually fit up to 10 passengers and complete loops around the city [Kathmandu] on various heavily trafficked routes” (ibid, 878). Women first started driving tempos in the 1990s and by now predominate (Grossman-Thompson Citation2020, 875). Grossman-Thompson (Citation2020, 878) explains that this gendered shift in Kathmandu’s tempo driving sector was realized with support (and large subsidies) of international NGOs, among other things, through sponsoring “driver training that explicitly recruited women drivers as part of women’s empowerment programmes”.

Grossman-Thompson (Citation2020, 878) further observed that the women tempo drivers she worked with were “socio-culturally diverse, [yet] they all had a low socio-economic status in common”, reflecting the sociological fact that “driving a tempo is a lower-end working class occupation”. In contrast, the Tootle and Pathao drivers we worked with varied in socio-economic terms. This can be explained by the fact that unlike tempo driving Tootle and Pathao driving is not necessarily a full-time occupation. In addition, whereas tempos are typically rented, Tootle and Pathao drivers must use their own motorbikes and smartphones. The majority of drivers we interviewed were between 20 and 34 years of age (14 out of 20). Two were older than 35 (43 and 44 respectively) and in the remaining four cases we did not know the precise age. Out of our 20 drivers, only six were doing the work full-time as their only job (which includes one of the women drivers) and out of these six two were doing so while waiting for an international migration project to commence. The majority of the drivers combined their work on the ride-sharing platform with other activities, such as university education (3), working in the IT sector (2), working as a magician (1), a job as Japanese language instructor (1), etc. (compare with Turner and Hạnh Citation2019, 12-3).

Full-time drivers would work up to 10 to 12 hours per day, whereas part-time drivers would do as little as 1-2 hours per day sometimes just using the platform to earn some money by taking on passengers on their way to/from work. For this latter category, the ride-sharing platform was experienced largely positively. For example, a 43 year old male driver who worked for Tootle a few hours per day remarked “despite people saying there is no earning and such, only by picking up customers twice a day while I commute to my office and return to home from office I am earning enough to cover my fuel, communication and tea costs on a daily basis.” (fieldnotes, 1 august 2019). For those relying fully on ride-sharing as a source of income the story was different (see also: Attoh, Wells, and Cullen Citation2019; Wu et al. Citation2019). The first author just did a couple of rides a day and would on this basis earn up to 1000 Nepali rupees a day (about 9 USD) but little of this remained after subtracting expenses made for fuel, mobile data bundles, a meal and refreshments. On this basis, it seems that driving full-time only gets profitable if one succeeds in getting a large number of rides a day and economises on personal expenses (drinks, foods, etc) while on the road. However, the more one drives the tougher it gets physically given the poor state of Kathmandu’s road network particularly during the monsoon season. In addition, doing more rides a day and especially in evening hours increases the chances of getting an accident with all costs involved the responsibility of the driver.

In terms of customer base, as of mid-2019 Pathao was the larger of the two platforms with 350,000 customers compared to Tootle (266,519 customers). Press statements indicate that women comprise about half of the registered customers using the platforms (Koirala Citation2018), and indeed, it proved not difficult to arrive at a gender-balanced sample for ride-sharing customers. Also, among the customers young people pre-dominated (13 out of 18 were between 20 and 34 years). One customer was 62 years old and in four instances we did not know the precise age. Passengers varied in terms of occupational background. A number were working in start-ups (4, including 2 women), others were working for an IT company (2 men), there were students (2 women), a consultant (1 woman), someone working in a bar (1 man), etc.

Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms: glocalised origin stories

Tootle and Pathao share some features that characterize companies operating in the gig economy the world over. Firstly, the platforms eschew employment relations with their drivers and work with them as independent contractors. Tootle consistently refers to their drivers as ‘Tootle partners’ while Pathao calls them ‘riders’. Van Doorn (Citation2017) describes this as a strategy of ‘immunity’. By avoiding an employment relation, platforms protect themselves and the customers buying the services “from the obligations that commonly pertain to an employment relation” (2017, 902). This strategy is illustrated in this excerpt about the terms and conditions (section 3) of the agreement Pathao drivers needed to comply with:

“THE COMPANY IS A TECHNOLOGY COMPANY THAT DOES NOT PROVIDE OR ENGAGE IN TRANSPORTATION SERVICES AND THE COMPANY IS NOT A TRANSPORTATION PROVIDER. THE SOFTWARE AND THE APPLICATION ARE INTENDED TO BE USED FOR FACILITATING YOU (AS A TRANSPORTATION PROVIDER) TO OFFER YOUR TRANSPORTATION SERVICES TO YOUR PASSENGER OR CUSTOMER. THE COMPANY IS NOT RESPONSIBLE OR LIABLE FOR THE ACTS AND/OR OMISSION WITH REGARD TO ANY SERVICES YOU PROVIDED TO YOUR PASSENGERS, AND FOR ANY ILLEGAL ACTIONS COMMITTED BY YOU. YOU SHALL, AT ALL TIME, NOT CLAIM OR CAUSE ANY PERSON TO MISUNDERSTAND THAT YOU ARE AN AGENT, EMPLOYEE OR STAFF OF THE COMPANY, AND THE SERVICES YOU PROVIDED BY YOU IS NOT, IN ANYWAY, BE DEEMED AS SERVICE OF THE COMPANY.” (original capitalisation).

In contexts in which informal employment is the norm, as is true for Nepal, such a strategy cannot necessarily be termed a deregularisation of labour - a point often made in critiques of the gig economy in the Global North. Moreover, when ride-sharing is done as a side-job next to employment in the formal economy as was the case for some of our driver respondents they still benefit from social protection through their formal sector employment.

A further feature that characterizes platform companies more broadly (see: Wood et al. Citation2019; Wu et al. Citation2019) is that Pathao and Tootle, too, use digital forms of control, for example by having customers rate the drivers upon completion of the service and suspending accounts could be done without first hearing drivers (Awale Citation2017). Thirdly, taking a closer look at the various interviews with Tootle and Pathao founders it is evident that their business ideas were sourced from global level examples. Interviews were replete with references to well-known international examples such as Ola Cabs, Gojek, Uber and Lyft. The global dimension of Tootle and Pathao is also underscored by mention the representatives make of the importance of foreign investment (venture capital) in their start-ups and by the overseas (tech) education several of these young entrepreneurs have enjoyed (e.g. Adhikari Citation2018).

Despite these global features and references in Tootle and Pathao’s origin stories, these two-ridesharing platforms are localised in distinct ways (see also Huijsmans and Lan Citation2015, 213; Yuana et al. Citation2019). First, both Tootle and Pathao present their platforms as a solution to a specific local problem: Kathmandu’s transport problems (Adhikari Citation2018). Public transport provisioning is limited and the conditions are often less than welcoming especially for the emerging middle classes and for women. Taxis on the other hand are too expensive for many Kathmandu residents and generally have a bad image because of taxi drivers cheating customers, their refusal to use meters, etc. Second, the owners of Tootle and Pathao also localise the narratives about the platforms by framing its emergence in relation to the 2015 Kathmandu earthquake and the 2015-16 economic blockade imposed by India on Nepal (leading to fuel shortages in Nepal). These events worsened the already existing transport problems. Kathmandu citizens addressed this by creating Facebook pages for carpooling and forms of ridesharing to make most of limited resources and challenging conditions. The ridesharing platforms of Tootle and Pathao are presented as a logical continuation and scale-up of these original and local citizen-led responses to crises. Take for example this excerpt from an interview with Asheem Man Singh Basnyat, Pathao’s regional director and responsible for setting up Pathao in Nepal:

The idea behind starting a ride-sharing app came to Basnyat during the Indian economic blockade of 2015/16. He said he helped a lot of people by giving carpool rides. Everything limped back to normal after the end of the blockade. However, the idea of ride-hailing company kept coming to his mind. (Baral Citation2019)

Similarly, Sixit Battha, one of the co-founders of Tootle is also said to be “in part inspired by what they saw during an Indian embargo in 2015…Then, Nepalese pooled resources and shared rides” (Adhikari Citation2018). Third, the Tootle origin story is also localised by its founders’ claim that the application was developed only after an initial app they designed to track buses of the Nepali company Sajha was met with no interest of the bus company. Apparently, it was “out of sheer boredom” that the Tootle founders then developed this technology further which led to the design of the Tootle app (Awale Citation2017). Fourth, practices of localisation also include platforms linking commercial strategies to Nepali national events. For example, on the occasions of the Dashain festival in 2019 (October), Tootle announced it would not take commission from any of its drivers (Dahal Citation2019). Finally, as we discuss in the next section gender is perhaps the most prominent manner in which the Kathmandu ride-sharing platforms localise their business.

Gender: from localisation to making ride-sharing markets gendered

The Tootle app was developed to give everyone the freedom of movement, especially those living with disabilities, women who face harassment in crowded public transport and those without personal vehicles (Awale Citation2019, emphasis added)

As the quote above illustrates, in their media presence Tootle and Pathao often relate their general slogans of inclusive mobility and freedom of movement to women in particular (Prasain Citation2018; Awale Citation2019). Next to women, differently abled people are also often referred to specifically (examples of partially sighted customers are especially common). However, as we proceed to argue a concern with women as a special target population is followed through much more firmly in the technological design of the platform and in its media campaigns than is true for differently abled passengers.

We do not question whether the concerns about gender-based violence in Kathmandu’s transport sector expressed by Tootle officials and to a lesser extent by Pathao representatives are genuine. Our argument is that it must also be recognised as a business strategy. After all, women constitute a large potential market share because they comprise half of the population, yet are less likely than men to own their own means of transport and they are more affected by gender problems in the public transport sector (Brunson Citation2014). Therefore, we argue that the measures implemented by Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms presented as aiming to make ride-sharing more women friendly (e.g. Baral Citation2019; ICT Frame n.d.) are more than just that. Since platform companies are in the business of making markets (Barratt, Goods, and Veen Citation2020; Richardson Citation2020, 634; Wu et al. Citation2019), these are efforts to create a market for ride-sharing in particular gendered ways.

A concern with women customers in the making of ride-sharing as a product has been there from Tootle’s early days. This is evident from Deepak Adhikari (Citation2018) contribution to the Nikkei Asian Review in 2018 in which he noted that “The Tootle app gives users the option to choose between male and female drivers, even though it currently has only male drivers” (emphasis added). In 2019, there were some women drivers on the road. However, each time the first author opted for “female driver” her ride-request was left unanswered (even after waiting for up to 30 to 45 minutes). On one occasion (28 July 2019), she then called the Tootle customer office to follow up on the matter. The customer office promised to check whether there were any female drivers available and call her back. After waiting for a while without a response the first author called again and this time she learnt that there were no female drivers in her proximity and that her request for a female driver could not be met.

Next to the button enabling customers to request for a woman driver, Tootle has also enhanced its ride-sharing product in the following ways: customers can enable a real-time monitoring of the ride and the option to send out an emergency SMS, for example, to friends or family (ICT Frame n.d.). Although these features may be used by any customer regardless of gender, given the mistreatment that often befalls women in public transport these technologies are likely to the enhance the sense of security for women customers more so than men. Therefore, these are further ways in which Tootle has created its ride-share product in particular gendered ways.

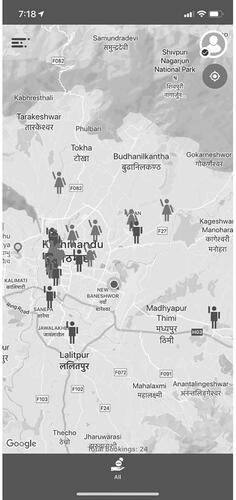

The gendered aspects of the drivers’ side of the Tootle application has received much less media attention. Yet, as illustrates, ride requests are mapped out electronically with clear symbols indicating whether the request comes from someone registered as male or female customer. Hence, the digital interface of Tootle’s drivers’ application represents the demand for Tootle ride-shares in pre-determined gendered ways; customers are either male or female. However, the certainty of coordination thus implied is not necessarily there in practice. It is not uncommon that a ride request made by a female registered customer (and thus showing on the interface as woman customer) is in fact for a male passenger and vice versa. This uncertainty of coordination needs to be resolved outside of the application through a phone call between the passenger and the driver. When drivers accept a ride-request, they receive the contact details of the customer and make a phone call to confirm the ride. So, when the first author on one of her first days accepted a request from what showed as a woman customer on the app’s interface, she was surprised to hear a man’s voice when she called to confirm the ride. The customer (a 33 year old development worker) later explained that it was his sister who had booked a ride for him. Although, not observed in our study the binary representation of gender is likely to complicate matters too for trans-gender or non-binary customers.

Another uncertainty of coordination underneath the app’s neat representation of the market of ride-requests is that customers always appear in the singular whereas in practice drivers may realise, sometimes as late as at the point of pick-up, that they have to carry more than one person (e.g. mother and child).

Pathao’s drivers’ interface lacks a gendered representation of the current demand for ride-requests. Yet, also here the product of ride-sharing quickly becomes a gendered product. Once drivers accept a ride request that has popped up on their screen through a push notification, drivers get to see the name of the customer. In most cases drivers will have no difficulty in knowing whether a name belongs to a male or female customer thereby rendering the product a gendered one which may have implications as we explain below.

Creating ride-sharing as a product in particular gendered ways appears to be a strategy that has paid off commercially. By May 2019, Tootle claimed that about fifty per cent of its customers were women (Awale Citation2019). Yet, both Tootle and Pathao struggled to attract more women to its fleet of drivers. In May 2019, Tootle claimed that only about 10 per cent of the drivers were women (Awale Citation2019).

A more gender-balanced fleet of drivers is arguably the most effective way to enhance women customers’ sense of security and thereby attract even more women customers. This is evidenced by research on commercial motorbike transport in rural Sierra Leone and Liberia where in a context in which most drivers are men, many women “indicated that they would prefer to ride with a female operator” had this been an option (Jenkins et al. Citation2020 138). The platforms seek to achieve this in the following ways. First, both Pathao and Tootle seek to normalise the idea of women as drivers through visual representation in their advertisement (see and ). Second, success stories about women drivers are often emphasised in interviews by the platform founders or directors. These stories illustrate that it is possible for women to become drivers without compromising on their traditional gendered roles (see the first quote below). Other stories stress the transformative potential that becoming a female driver holds (see the second quote below). All stories stress the economic promise the job holds for women drivers.

Bhimmaya Sunuwar…a mother of two from Dharan works as a Tootle driver from 9AM-3PM, when she is free from her duties as a mother and homemaker. She makes Rs30,000 a month. (Awale Citation2019)

Ganga Chhantyal is one good example of female Pathao driver. Chhantyal is differently-abled driver who earns about Rs 35,000 every month. She now feels respected and regular income has boosted her confidence. (Baral Citation2019)

Third, Tootle also intervenes directly in the labour market dimension of ride-sharing in gendered ways. It does so through a policy of not taking a commission from women drivers (Awale Citation2019). From other drivers, Tootle took a 4 per cent commission provided they did more than five rides a day (as of October 2019 Tootle stopped charging commission from all its drivers). Pathao charged a 20 per cent commission at the time of research.

Gender in the placed performance of Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms

“Doing gender” on and off the back of the motorbike

High-caste gender ideology continues to structure how women understand their role in modern Nepal, and norms of domestic seclusion and chastity have especially shaped how women who participate in the public sphere through waged labor are perceived and how they perceive themselves. (Grossman-Thompson Citation2017, 488)

Kathmandu’s young working women enact their middle-class aspirations (see also: Brunson Citation2014) and on this basis have come to embrace the relative freedom of movement provided by the newly emerging ride-sharing platforms. Yet, similar to Grossman-Thompson (Citation2017) women trekking guides, using a ride-sharing platform creates a degree of anxiety among at least some young women as they are aware how gossip may damage their social honour:

When I started using the ride-sharing platform, I was very cautious that nobody sees me. Thus, I would ask the [man] driver to drop me off nearby my home [but out of sight]. Later, I realised I am paying the person. So, I must be dropped off at my destination and I started taking them until the main gate of my house. But somehow, I would make sure that every time I take ride through the platform my nosey neighbour sees me paying the driver. So, he knows that there is some kind of transaction happening – not a relationship. (26 years, woman customer, 31 July 2019).

Whereas gender is built into the platform’s interface as an individual and bounded property, the excerpt above shows that in the placed performance of ride-sharing gender is a relational matter and embedded in Kathmandu’s changing gender regime. In the Kathmandu valley women’s independent mobility has become increasingly common (Brunson Citation2014) and ride-sharing platforms can be said to have contributed to this - especially for young women who have their own income but not their own means of transport. Despite these changes, conservative gender norms still matter (Grossman-Thompson Citation2017). As a result, gendered contingencies emerge as part of the placed performance of ride-sharing. Conservative gender norms task women customers with resolving these contingencies in order to (re)produce ridesharing not only as a flexible but also as a gendered good. In this excerpt it takes the form of the young woman’s active management of her neighbour’s impressions which can be understood as a form of “doing gender”; a gendered performance “undertaken by women and men whose competence as members of society is hostage to its production” (West and Zimmerman Citation1987, 126).

Gendered contingencies also emerge on the back-of-the-motorbike. Here too, women are tasked with resolving them by doing gender in a particular way. The case in point is the common practice of women placing their backpack or handbag firmly between themselves and the male driver (compare with Truitt Citation2008, 6). This act is as much public as it is private. It serves to mark publicly a woman’s journey on the back of a man’s motorbike as commercial ride-share, not to be mistaken for any romantic relation. In addition, at a private level it is an effective measure against any unwanted body contact between a man driver and woman customer.

In her analysis of the UK food delivery platform Deliveroo, Richardson (Citation2020, 631) draws on Ekbia and Nardi’s concept of “heteromation”. Heteromation emphasises that “technical systems function through heterogeneous actors” and illuminates “how human labour fills gaps in the computer system”. For our purposes we need to engender the concept of heteromation. “Gendered heteromation” requires situating the different actors (drivers, customers), technologies (the technical design of the application) and places (from the back-of-the-motorbike, one’s neighbourhood, to public roads) that are assembled in ride-share as a gendered good in the broader, and shifting gender landscape of urban Nepal. Gendered heteromation acknowledges that gender is built into the digital infrastructure but emphasises that it is ultimately in the placed performance of the platform that gender needs to be done in order to realise ride-sharing as a gendered product. In the case of the Kathmandu ride-sharing platforms it further illuminates that in this work men and women are held accountable very differently for keeping up gender norms.

Gender-based violence

The previous section has emphasised the gender work that falls on the shoulders of women in order to (re)produce ridesharing as a gendered product. In this section we shift focus to men and turn to instances in which the actors involved have interests different from, or beyond reproducing the ride-share as a flexible and gendered arrangement.

The first author became aware of such possibilities through first-hand experiences:

Before I was able to reveal my student-researcher identity to a 30 year old male passenger, he had already started making conversation with me while on the back of my scooter. He was an engineer and normally based at a hydropower plant outside of the valley, but he told me “I am here in Kathmandu for two weeks, I will have to commute frequently. Since you are sharing ride, I will call you tomorrow when I need a ride”. From a driver’s point of view, it is attractive to get rides outside of the platform because no commission will be cut, however, I started feeling uncomfortable when he asked me whether I had a Facebook account and when he said that he really liked me. I made clear I had no interest in him beyond my professional duty of completing the ride and nothing problematic happened. However, my suspicions were confirmed when the passenger rang me the very same evening, and again the day after. I realized how vulnerable women are as both drivers and customers because the ride-sharing platform makes visible one’s contact details as part of the arrangement. (Fieldnotes, 8 August 2019 about driving for Tootle).

Experiences like these we shared with a former female staff member (and driver) of Tootle. She explained that the company was aware of gender issues. Yet, the freelance model in which drivers are in principle free to accept or decline the orders coming their way makes intervening difficult she claimed:

We strictly monitor our driver’s activity…We have found that certain male drivers have tendency of only giving ride to female customers. We as a platform cannot tell them you have done wrong or right, because ultimately it is the whole point of platform – freedom of work. Thus, we intentionally assign them to pick nearby male customer’s request by calling them. Even after this they frequently reject to share ride with male customer we then enquire them what is going on by again calling and enquiring them why did they refuse male customer’s request? (Former platform staff member and driver, 30 year old woman, 23 July 2019).

Similarly, the description below from a compulsory onboarding session for newly registered Pathao drivers suggests that on the Pathao platform, too, gender problems have taken place:

The Pathao training staff told all new drivers (all men accept the first author) not to tease women customers, or even give them feedback that may reflect as sexual comments. They also told new drivers things like “Do not ask female customers to sit closer, don’t touch them, don’t use the brakes unnecessarily while sharing ride with female customers which forces their frontal body part to touch you” (Notes from Pathao orientation class for new drivers, 11 July 2019).

Our data confirm that at least some male drivers prefer women passengers over men, and the technical design of the platform allows them doing so. For example, women customers rarely had to wait very long for their ride requests to be accepted:

I never had to wait more than 10 minutes of a ride request sent (29 year old woman customer (mostly using Tootle), 28th July, 2019)

This was different for some male customers:

It will be a pleasant surprise if I ever get a ride without waiting for more than 30 minutes (28 year old man customer (mostly using Tootle), 31 July 2019)

The man cited above then asked his male Tootle driver why he had been waiting so long before his ride request was accepted. He got the following response:

You should feel lucky, because you are my first male customer [today]. I never give ride to male but only to female, why would I become driver otherwise – it’s fun having a female on the back of my motorbike.

Instances like the above are problematic because women are objectified. Yet, we also came across examples in which the platforms’ technological design, that makes names and contact details visible as part of the ride-sharing procedure, lead to other potential forms of gender-based violence. For example, a woman customer shared the following screenshot in the Facebook group Pathao/Tootle Sarana Nepal Support group (13 September 2019) (see ).

Cases like the above in which male drivers (or customers) contact their female counterparts in the ride-share unwantedly and inappropriately are entirely avoidable if the platforms were designed in such a way that private telephone numbers would remain invisible to those providing and seeking the platform services. Further, the necessary flexibility of ride-sharing as a product is not compromised if drivers and passengers can only contact each other in an anonymized manner. Finally, the concept of gendered heteromation highlights that in instances like these it is not only that technical systems function in and through gender regimes, but also that gender regimes, which includes potential gender-based violence, may function through the placed performance of platforms.

Conclusions

In this article we have contributed to feminist geographies by bringing into dialogue literature on the emerging platform economy in the Global South with recent work on changing gender norms in urban Nepal. On this basis, we have furthered the theoretical premise that platform companies are in the business of making markets from a gender perspective. We have argued that gender is key to the localisation strategies employed by the Kathmandu ride-sharing platforms studied. This way, concerns with women’s safety in Kathmandu’s public transport are merged with commercial interests in women as a market-share.

We have demonstrated that at the level of the interface market, gender is built into the design of the platform as an individual, bounded property. We contrasted this with an analysis of the placed performance of the ride-sharing platforms. With regard to the latter, we have proposed the concept of gendered heteromation. Gendered heteromation acknowledges that gender is built into the digital infrastructure but emphasises that it is ultimately in the placed performance of platforms that gender needs to be done in order to realise ride-sharing as an appropriately gendered product. In the case of the Kathmandu ride-sharing platforms it further illuminated that in this work men and women are held accountable very differently for keeping up gender norms. More problematically, our data also showed that the actors involved may have interests different from, or beyond reproducing the ride-share as a flexible and gendered arrangement. In such cases, the way gender is written into the design of the platforms may lead to potential gender-based violence.

Picture 2. Normalising the idea of women drivers, Tootle (source: (Shrestha Citation2016)).

Picture 3. Normalising the idea of women drivers, Pathao (source: (Pathao Citation2021)).

Picture 4. Male drivers seeking unwanted contact with a women (Tootle) customers following a ride-share.

Overall we acknowledge that Kathmandu’s ride-sharing platforms contribute to expanding further conservative gender boundaries (Brunson Citation2014) by enabling women’s independent mobility – especially for those who have their own income but not their own means of transport. Our examples of doing gender, however, have shown that progress is not a linear path and that simultaneously more conservative gender norms are reproduced in the situated practice of ride-sharing. While such “doing gender” may be necessary for reproducing ridesharing as a gendered product in a socially acceptable way, making visible the contact details of drivers and customers as part of the ride-share is not. We have shown how this can lead to potential gender-based violence. In March 2021, the platforms have made a first step in remedying this situation. Private telephone numbers were no longer visible on the platforms’ interface as part of the arrangement, but when drivers or customers make a call through the app to the other party the actual number remains stored in the telephone’s call log. We urge platform companies to address, too, this remaining issue. Finally, the data we have presented also show that the users of ride-sharing platforms actively publicise the gendered problems they have encountered through social media. Platform companies often do not fit existing legal categories, rendering the state’s ability to intervene in the gig economy limited – and the case of Nepal is no exception. Therefore, such citizen-led social media action by women offers some scope for realising change in the gig economy and is something that would merit further research within feminist geographies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits for her invaluable input in the Masters’ thesis project underpinning this article. Our thanks also go out to the various platform drivers and customers who have participated in the research as well as to Tootle and Pathao for answering some research queries. Finally, we are grateful to the four anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for having made the peer review process such a pleasant and constructive journey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pritee Hamal

Pritee Hamal is an independent researcher based in Kathmandu, Nepal. She holds an MA in Development Studies and Gender Studies.

Roy Huijsmans

Roy Huijsmans is associate professor Childhood and Youth studies at the International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam (Netherlands).

References

- Adhikari, Deepak. 2018. “Motorbike-sharing App Helps Tackle Nepal’s Transport Woes.” Nikkei Asian Review. Accessed 28 February 2020. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-trends/Motorbike-sharing-app-helps-tackle-Nepal-s-transport-woes.

- Attoh, Kafui, Katie Wells, and Declan Cullen. 2019. “We’re Building Their Data”: Labor, Alienation, and Idiocy in the Smart City.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (6): 1007–1024. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819856626.

- Awale, Sonia. 2017. “Kathmandu’s Silicon Alley and the Law.” Nepali Times. Kathmandu. Accessed 29 February 2020. https://archive.nepalitimes.com/article/Nepali-Times-Buzz/outdated-laws-limited-ecommerce-hold-back-tech-industry%20,3547.

- Awale, Sonia. 2019. “Three Toots for Tootle.” Nepali Times. Kathmandu. Accessed 29 February 2020. https://www.nepalitimes.com/here-now/three-toots-for-tootle/

- Baral, Adita. 2019. “How a Startup Became Nepal’s Leading Ride-hailing Firm.” MyRepublica. Kathmandu: Nepal Republic Media Pvt. Accessed 28 February 2020. https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/how-a-startup-became-nepal-s-leading-ride-hailing-firm/

- Barratt, Tom, Caleb Goods, Alex Veen. 2020. “I’m my Own Boss…’: Active Intermediation and ‘Entrepreneurial’ Worker Agency in the Australian Gig-Economy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (8): 1643–1661. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20914346.

- Brunson, Jan. 2014. “Scooty Girls’: Mobility and Intimacy at the Margins of Kathmandu.” Ethnos 79 (5): 610–629. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2013.813056.

- Dahal, Florena. 2019. “Nepali Ride-Sharing App Tootle Starts 24 × 7 Service.” Accessed 26 March 2020. https://techsathi.com/tootle-starts-24x7-service>

- Ford, Michele, and Vivian Honan. 2019. “The Limits of Mutual Aid: Emerging Forms of Collectivity among App-Based Transport Workers in Indonesia.” Journal of Industrial Relations 61 (4): 528–548. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185619839428.

- Grossman-Thompson, Barbara. 2017. “My Honor Will Be Erased”: Working-Class Women, Purchasing Power, and the Perils of Modernity in Urban Nepal.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 42 (2): 485–507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/688187.

- Grossman-Thompson, Barbara. 2020. “In This Profession We Eat Dust’: Informal and Formal Solidarity among Women Urban Transportation Workers in Nepal.” Development and Change 51 (3): 874–894. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12580.

- Hamal, Pritee. 2019. Renegotiating Social Identities on Ride-Sharing Platform: A Mobile Ethnographic Study of Pathao and Tootle in Kathmandu, Nepal. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

- Hansen, Arve. 2018. “Doing Urban Development Fieldwork: Motorbike Ethnography in Hanoi.” SAGE Research Methods Cases in Sociology. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526429384.

- Huijsmans, Roy, and Trần Thị Hà Lan. 2015. “Enacting Nationalism through Youthful Mobilities? Youth, Mobile Phones and Digital Capitalism in a Lao-Vietnamese Borderland.” Nations and Nationalism 21 (2): 209–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12095.

- ICT Frame. n.d. “The Rise of Tootle in Nepalese Market.” ICT Frame. Accessed 29 February 2020. https://ictframe.com/the-rise-of-tootle-in-nepalese-market/

- Jenkins, Jack, Esther Yei Mokuwa, Krijn Peters, and Paul Richards. 2020. “Changing Women’s Lives and Livelihoods: Motorcycle Taxis in Rural Liberia and Sierra Leone.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Transport 173 (2): 132–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1680/jtran.18.00162.

- Liechty, Mark. 2003. Suitably Modern: Making Middle-Class Culture in a New Consumer Society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Neupane, Gita, and Meda Chesney-Lind. 2014. “Violence against Women on Public Transport in Nepal: Sexual Harassment and the Spatial Expression of Male Privilege.” International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 38 (1): 23–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2013.794556.

- Pathao. 2021. “Pathao Blog.” Accessed 15 April 2021. https://pathao.com/blog/category/npl/

- Pollio, Andrea. 2019. “Forefronts of the Sharing Economy: Uber in Cape Town.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (4): 760–775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12788.

- Postill, John, and Sarah Pink. 2012. “Social Media Ethnography: The Digital Researcher in a Messy Web.” Media International Australia 145 (1): 123–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1214500114.

- Prasain, Krishana. 2018. “Hopping On.” Kathmandu Post.

- Koirala, Princi. 2018. Wishing Tootle Happy Birthday and Goodbye. Blog by Princi Koirala. Accessed 29 February 2020. https://princikoirala.com/2018/12/31/wishing-tootle-happy-birthday-and-goodbye/.

- Richardson, Lizzie. 2020. “Platforms, Markets, and Contingent Calculation: The Flexible Arrangement of the Delivered Meal.” Antipode 52 (3): 619–636. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12546.

- Shrestha, Bnay. 2016. “Tootle: Ride-Sharing in Nepal.” Accessed 15 April 2021. https://www.viewyourchoice.org/2016/10/tootle-ride-sharing-in-nepal.html

- Snellinger, Amanda. 2013. “Shaping a Livable Present and Future: A Review of Youth Studies in Nepal.” European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 42: 75–103.

- Sopranzetti, Claudio. 2018. Owners of the Map: Motorcycle Taxi Drivers, Mobility, and Politics in Bangkok. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Srnicek, Nick. 2017. “The Challenges of Platform Capitalism: Understanding the Logic of a New Business Model.” Juncture 23 (4): 254–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/newe.12023.

- Truitt, Allison. 2008. “On the Back of a Motorbike: Middle-Class Mobility in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.” American Ethnologist 35 (1): 3–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2008.00002.x.

- Turner, Sarah, and Ngô Thúy Hạnh. 2019. “Contesting Socialist State Visions of Modern Mobilities: Informal Motorbike Taxi Drivers’ Struggles and Strategies on Hanoi’s Streets, Vietnam.” International Development Planning Review 41 (1): 43–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2018.10.

- van Doorn, Niels. 2017. “Platform Labor: On the Gendered and Racialized Exploitation of Low-Income Service Work in the ‘on-Demand’ Economy.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (6): 898–914. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1294194.

- West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society 1 (2): 125–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002.

- Wood, Alex J., Mark Graham, Vili Lehdonvirta, and Isis Hjorth. 2019. “Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy.” Work, Employment & Society : A Journal of the British Sociological Association 33 (1): 56–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018785616.

- World Bank and AusAid. 2013. Gender and Public Transport: Kathmandu, Nepal. Kathmandu: The World Bank Group, Australian AID.

- Wu, Qingjun, Hao Zhang, Zhen Li, and Kai Liu. 2019. “Labor Control in the Gig Economy: Evidence from Uber in China.” Journal of Industrial Relations 61 (4): 574–596. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185619854472.

- Yuana, Suci Lestari, Frans Sengers, Wouter Boon, and Rob Raven. 2019. “Framing the Sharing Economy: A Media Analysis of Ridesharing Platforms in Indonesia and the Philippines.” Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 1154–1165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.073.