Abstract

Among committed readers of romantic fiction in Malaysia, constructed ideals of intimacy are mobilised as a matter of personal moral enterprise and a panacea for emotional asymmetry between the sexes. Yet, such ideals are as much an outcome of collective meaning-making as an individual one. As this article will show, the affective rewards of mediated romance are relational and have a distributive, contagious, transformative as well as spatial effect crossing spaces both ‘private’ and ‘public’, work and leisure, personal and community. I argue that aspirations for marital success and personal self-actualisation motivate a range of affective creative labour for sustaining ethical relationships with the self, significant others, family, and community in what I call the counterpublics of care, which refer to social assemblages committed to the revaluation of intimacy, emotion work, and love.

Introduction

Among committed readers of romantic fiction in Malaysia, constructed ideals of intimacy are mobilised as a matter of personal moral enterprise and a solution to the problem of emotional asymmetry delimited by religious bureaucracy and cultural formations. Yet such ideals are as much an outcome of collective meaning-making as an individual one. As this article will show, the affective rewards of mediated romance are relational and have a distributive, contagious, transformative as well as spatial effect, crossing spaces both ‘private’ and ‘public’, work and leisure, personal and community. I argue that aspirations for marital success and personal self-actualisation among readers and producers of romantic fiction motivate a range of affective creative labour for sustaining ethical relationships with the self, significant others, family, and community in what I call counterpublics of care, which refer to social assemblages committed to the revaluation of intimacy, emotion work, and love. Counterpublics are emergent, self-organised collectives (Asen Citation2000) that come into being through the structures of ‘alternative dispositions or protocols’ (Warner Citation2002, 56–7). They typically presume a subversive character, one defined by a response to exclusion and shaped by contest and oppositional politics (Fraser Citation1992; Asen Citation2000; Warner Citation2002). In this article, however, such emergent collectives occupy superimposed or ‘nested’ (Taylor Citation1995) publics, whereby the circulation of care and romance discourse overlays structures that consolidate ethnic and religious preeminence and exclusivity in a society where race takes institutionalised precedence over all other social categories. It demonstrates that the ‘concatenation of texts’ generated by counterpublics (Warner Citation2002, 90) is dependent on, though unequal to, dominant publics rather than operating in the state of complete exclusion.

The transformative and healing effect of mediated romance is illustrated in the life and media habits of a woman I spoke with during my research. Murni was a participant in a focus group discussion I organised in 2018 in Kuala Lumpur for married and formerly married romance fiction readers. Expressive and articulate, Murni wears the hijab, works full-time and has a university degree. She is divorced with two young children and single at the time of our meeting. She accepted my invitation to the participate in the focus group discussion because she was very keen to share the pivotal role popular romantic fiction played in her recovering from the emotional aftermath of a marital betrayal and breakdown. After her divorce, Murni plunged headlong into her place of solace, Malay romantic fiction, and proceeded to display signs of ‘reading badly’ (Millner Citation2012); reading became an indulgence and escape. The immersive engagement with the genre led to the re-evaluation of her self-identification as a wife, mother, sister, and woman. She turned to love stories about forced marriage and female suffering, re-reading ones about female characters who had reinvented themselves after a divorce and emulating them to regain a sense of strength (kekuatan) after an extended period of turmoil. When asked why stories of coerced relationships appealed to her, Murni revealed that she too, like the fictional characters she reads, was once a victim of forced marriage.

Shortly after graduating from university, Murni’s mother had arranged for her to marry a male friend without having discussed with her first. She was initially offended by the arrangement but she felt coerced to acquiesce due to filial piety. Her father had passed away and she felt duty-bound to be a good daughter to her surviving parent. Sadly, the marriage was a struggle. Although love gradually developed, Murni stated it ‘ended’ after the birth of their second child during which time her husband began engaging in extramarital affairs with other women, infidelities she chose to forgive. But Murni’s marriage finally broke down following her husband’s attempt to rape her younger sister. It took her three years to finalise their divorce. Her ex-husband had quickly remarried since but she remained single to focus on her work and children when her immersion into romantic fiction became more pronounced, involving three novels a month. On weekends, reading could take over her entire day. So engrossed was she that she would forget to eat and only took breaks from reading to use the toilet. The recuperative engagement with romantic fiction later unleashed a desire in Murni to write her own novel, which she provisionally calls Another Husband for Polyandrous Mama (Madu untuk Mama). She intends to give the novel a ‘light’ romantic touch, implying that there is humour in the story. The title and subject matter of her creative attempts, however, are subversive and in conflict with orthodox interpretations of Islam. Only men are allowed to marry more than one woman and up to four at a time. By upending the conventional terms of Muslim polygamy in her fictive vision, Murni takes her ‘revenge’ on the culture of ‘silence’ that women like herself must endure when Malay men tell jokes about their ability to take on multiple wives (Sloane-White Citation2017).

Murni’s creative and restorative endeavours are embedded in the ever-moving parts of gender, ethnic and religious formations in multicultural Malaysia. Female sexuality, marriage and the family have been the direct and indirect target and effect of postcolonial nation-building transformations. Women’s bodies became the site of such transformations where they are disciplined to be docile workers, wives, and mothers in the service of state-directed nationalist-capitalist agendas (Ong Citation1987; Stivens Citation2006). Female subjectivity is further redefined along an even narrower remit of sharia law reforms that began in the 1980s in government efforts to remake the ‘modern’ Muslim family. The reforms have had a zero-sum effect: they facilitate polygyny for men but weakened the protection of a woman’s financial interests from her polygamous husband’s legal claim to their shared matrimonial assets for the purpose of supporting his other wives. Muslim gender relations in Malaysia, however, are not always so bleak. Unlike the strictly-regulated gender segregation and limits placed on women’s (social) mobility in some Muslim-majority societies, women in Malaysia benefit from state-sponsored mass education and enjoy access to paid employment opportunities and financial independence without much hindrance. There are, however, limits imposed by corporate-bureaucratic standards of sharia compliance in workplaces that effectively create a gendered hierarchy of labour and the glass ceiling (Sloane-White Citation2017). At this nexus of work and intimacy, emotional distress and discontent at discrimination are often pushed aside by the widespread acceptance that women’s subordination is ‘Islamic’ (Basarudin Citation2016).

Although pushback against gender-based discrimination exists, such as the persistent efforts of the Muslim feminist organisation Sisters in Islam, women’s media practices can shed light on the everyday means of critical engagement with discourses of institutional power. They also raise questions about the transformative potential of mediated intimacy such as: what kinds of work can intimacy and romance do in different spaces and places? In what ways can romantic fiction as a creative exchange of ideals and ideas be used as the basis for collective bonding and care? What kinds of structural resistances and complicities are negotiated in attempts to establish and maintain collective bonding and care relations? In this article, romantic fiction’s mission as a moral and affective enterprise, its emphasis on relations, and implicit cultural critique of women’s status in a patriarchal society is consistent with Carol Gilligan’s ethic of care, in which ‘the relationship becomes the figure, defining self and others. Within the context of a relationship, the self as a moral agent perceives and responds to the perception of need’ (Citation1987, 23). Gilligan’s ethic of care is concerned less with the placement of the autonomous individual at the centre of justice than with providing care for others, preventing harm, and maintaining relationships. An ethic of care that corresponds with Gilligan’s definition is mediated through romantic texts and the collaborative interactions between readers, authors and booksellers that take place and are suffused in the material infrastructures that make counterpublics of care possible. The association of reading with care is made especially explicit when Kuala Lumpur became the host of the annual UNESCO World Book Capital in Citation2020. Under its twin slogans, ‘Caring through reading’ and ‘A city that reads is a city that cares’, notions of care were instrumentalised in the event’s mission to pursue accessibility and inclusiveness through reading ‘in all its forms’ and supporting the local publishing industry (UNESCO website). Its mission to expand inclusivity, however, is limited to improving access for disabled groups and those living in socioeconomically deprived areas. While Malay romance may be influenced by these global-corporate constructions of ‘care’, it could also be shaped by the local politics of care (prihatin, jaga Tan Citation2020) that springs from an ethics of communitarian welfare (gotong-royong).

The annual bookfair and bookshop in Malaysia create opportunities for fulfilling previously unmet affective needs and bringing together new relations, practices, and subjectivities centred around romance and care, forming ‘intimate publics’ (Berlant Citation2008). But their material locations – ones marked by ethnic nationalism and exclusivity, which I will discuss in more detail below – produce gendered complicities of racialised space. The exclusion of non-Malay ethnic minorities from these intimate publics mirrors the racialisation of space elsewhere in the country. Space in Malaysia is produced by the ‘overwhelming prominence’ of race, its urban spaces by racialised ‘surveillance, unease, and anxiety’ (King Citation2008, 56–57). Multicultural since its inception as a postcolonial nation in 1957, Malaysian society is comprised of the Malays (60%) of whom all are Muslim, ethnic Chinese (30%), ethnic Indians (9%), and other ethnic minorities belonging to different religious groups. The Malay majority, whose constitutionally-defined ethnicity is fiercely defended by ethno-nationalist politics, enjoy preferential treatment in education and socioeconomic opportunities (Mohamad and Aljunied Citation2013).

I began my field research on the social and commercial practices that underpin the Malay romance industry in February 2017. A series of focus group discussions was organised with readers between ages 19 and 29 and with those aged 30 to 50 who were either married or divorced, and were parents, married and/or single. They were segregated into the two age groups to anticipate different media habits and thematic interests. Although the invitation to participate was not gender-specific, all focus group participants who attended the sessions identified as Malay-Muslim women and committed readers of the Malay romance genre. I also met with five popular and emerging authors, several publishers, booksellers, editors, and individual readers of romance novels for audio recorded in-depth interviews. All throughout the course of the field research, I also undertook repeated participant observation and ‘deep hanging out’ (Geertz Citation1998) at bookshops and bookfairs around Selangor and Kuala Lumpur between October 2017 and April 2019. Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted in the Malay language (Bahasa Melayu) and occasionally in English. The names of all research participants have been changed for this article.

As I will discuss in subsequent sections, women’s emotion work lies at the foundation of Malay romance and conservative ideas about romantic love. As a resource it often goes unappreciated and uncompensated in domestic relationships, but the Malay romance industry taps on it. Stories repurpose cultural ideas of women as emotional creatures responsible for the delicate management of peacekeeping in the household to produce a social text and a version of care. Social spaces of the romance industry provide opportunities for women to become a source of emotional support and validation for each other in ways both direct and indirect. These become counterpublics of care where relations and practices formed around the mediated intimacy of romantic text are cultivated and reappraised for their value to the self and others, but they are also contingent on spatialised ethnic and religious preeminence.

Romantic love and emotional asymmetry in Malay society

Desire for love and companionate marriage may seem like a universal phenomenon, but its specific elaboration in meaning and practice is highly varied and culturally specific (Hirsch and Wardlow Citation2006; Padilla et al. Citation2007). Such cultural specificities become especially salient in Muslim communities where romantic love is not a religious obligation for husband or wife as each is contracted to fulfill different responsibilities in their respective roles in the marital union. Informed by different competing discourses, romantic love can still prevail as an emotional bond between Muslim couples even in the face of religious orthodoxy (see Inhorn, et al. Citation2007). Through the lens of culture, constructions of Malay intimacy and emotions are understood as a question of gendered difference, asymmetry, excess and lack, which presume a division of emotion work between women and men. Management of Malay women’s ‘natural’ emotional excesses and passions is a state-religious and community imperative to produce (re)productive bearers of communal identity. The Malay word ‘nafsu’, from the Arabic nafs to mean ‘self’ or ‘soul’, refers to desire and naked sexual passion that need to be curbed through moral means, either by marital bond or prayer. Both women and men have nafsu but women are thought to possess more of it while also being the temptress of men’s nafsu, placing the moral responsibility on women to maintain their modesty (Peletz Citation1996). Needless to say, Malay women’s culturally informed predisposition to be more ‘passionate’ and emotional than men mirrors essentialist gender binaries elsewhere. Far from being inherent to ‘tradition’ and ‘culture’, emotional asymmetry in Malay society is further entrenched by the multiple reforms to sharia legal provisions since the 1980s that formalise the terms of marriage and divorce for couples. These reforms have had the effect of expanding a man’s privilege to facilitate the initiation of divorce (at one point as easy as sending a phone text message), to contract polygamous marriages without the explicit consent or even knowledge of his other spouse(s) and claim his matrimonial assets from other wives to support another wife (Mohamad Citation2011). Such unequal terms are accepted with pious stoicism (pasrah) by many women as a reflection of the Qur’anic gender order, but not without ‘deep’ and ‘surface acting’ (Hochschild Citation2012). Overt discontent would otherwise be interpreted as a perilous lack of faith.

Marriage preparation courses, compulsory for Muslim couples who register to marry in Malaysia, lay the institutional terms of intimacy. The courses guide couples in ways to accomplish marital success and the fulfillment of Islamic obligations within the bond of marriage. Cultural specificity is built into the bureaucratic management of Muslim marriage in Southeast Asia, particularly in its emphasis on romantic love or lack thereof. In neighbouring Singapore, Muslim couples who attend the preparatory course are introduced to the importance of everlasting love (cinta abadi) and equal companionship (Suratnam Citation2021). Under the aegis of the Singaporean ministry of community development, the Muslim marriage registry serves the minority Muslim population in alignment with the state’s secular cosmopolitan vision and its emphasis on mutuality and shared responsibility. But in Malaysia, couples are reminded of the husband’s sexual entitlement and wifely obedience to him, with little talk of love (Mohamad Citation2020).

The lack of emphasis on love as the connective emotion in marriage in the Malaysian Muslim marriage preparation course is rubberstamped by a bureaucracy positioned within the ministry of religious development whose mission is the advancement of sharia law in the land. Under its guidelines, marital rights and responsibility divided along gendered lines reflect the patriarchal breadwinner-provider and spousal dependence dynamic. The architecture of this dynamic is mapped onto other areas of everyday life, which suggests its wider implications, such as health and economic ramifications in the workplace for married couples. For instance, a provision of healthcare benefits exists for the spouse(s) of male employees in the sharia-compliant workplace but not for married female employees whose spouse is assumed to be the main financial provider of the family and for that reason requires no assistance (Sloane-White Citation2017). Under these circumstances where inequality structures the domains of intimacy, mediated expressions of romantic love can be difficult for women. But romance can be a site to address the emotional deficit in intimacy and performed as part of an ethical agenda. The etymological origin of ‘love’ in the Malay language, ‘cinta’, may redeem the lowbrow reputation of Malay romance by associating it with care. Cinta is derived from the Sanskrit word for ‘thought’ or ‘care’, suggesting a link between the act of reflecting on something or someone and the act of love. From its semantic roots, ‘love’ could be edifying even though the titles and content of some novels of the genre imply otherwise. In other words, cinta is good to think with especially in relation to problematising the assumptions of its apparent universality.

The priority for thought and reflection in romantic love over physical intimacy is evidenced in Wazir Jahan Karim’s groundbreaking research on the discourse of emotions in traditional Malay society (Citation1990). Romantic feeling during courtship is traditionally mediated through verse (pantun) and song. Because the overt expression of love and desire is subject to moral censure, courting couples send each other lines of verse to convey their innermost feelings (see also Abu Lughod (Citation1986) for the similar mediating functions of poetry in Bedouin society). However, her study found patterns of male agency and female passivity in the poetic expression of emotions during courtship. This raises questions about the opportunities made accessible by global socioeconomic transformations with regard to the creation of new desires, expressions, practices, and subjectivities for women. As research by Lila Abu Lughod (Citation2005) shows, media practices have helped to reconfigure gender roles and the romantic expectations of women who belong to generations that have undergone rapid processes of modernisation and increased access to higher education, white-collar employment, and migration to urban centres. The pantun may be conterminous with the newer genres of romantic textual culture in their shared reliance on mediated intimacy. But unlike the pantun, the circulation of romantic fiction is elevated to a systematic and commercial arena with its own material and multi-mediatised spaces discussed below.

The articulation of emotion facilitated by cultural forms and story-telling media coheres with Michelle Rosaldo’s reflection that ‘feelings are not substances to be discovered in our blood, but [in the] social practices organised by stories that we both enact and tell’ (Citation1984, 143). Echoing Rosaldo, the notion of ‘mediated intimacy’ is important for understanding how media texts, practices, and relations interweave and embed deeply in lived realities. Coined by Rosalind Gill (Citation2009), ‘mediated intimacy’ describes ‘the ways in which our understandings and experiences of a whole range of intimate relationships are increasingly mediated by constructions’ from media culture. I would suggest that ‘mediated intimacy’ becomes a resource for practicing romantic ideals in a socially conservative society where divulging openly about female desire is circumscribed. Media narratives have increasingly become the primary source of instruction as the moral authority of traditional guardians – parents and other family members – is diminished by the inter-generational attitudinal gap created by weakening bonds of kinship relations and rural-urban migration (see Masquelier Citation2009). In situations where their authority looms large, the consumption and circulation of such narratives, seen by some as illicit for its portrayal of active female sexuality, are sequestered away from surveillance and scrutiny.

The desire for feeling and development of a new language for romantic love and intimacy previously alien to a culture are indicative of a neoliberal moment that harnesses emotion in the project of self-making (Freeman Citation2020). Such desires have particular resonance in Southeast Asia as the site of global manufacturing and post-industrial economies that profit from the ‘immaterial’ labour generated by the care, service, and knowledge-based industries. Aihwa Ong (Citation1987) captures a vivid image of a Southeast Asian society in transition, pulled in different directions by the state and global manufacturing. At the heart of that image are the Malay factory women who, as the engines of local and global economy, become the objects of manufacturing industries. Although they are disciplined by global capitalism and male surveillance on the factory floor, the factory operators found ways to gain new understandings of themselves as financially independent women liberated from male guardianship in their hometowns. Their new subjectivities accessed consumption-oriented intimacies and femininities previously unavailable to sheltered village women which created, rather unsurprisingly, anxiety among community and national moral stakeholders. The foregoing image is turned on its head when we focus on the Malay women who are subjects of a different kind of material and immaterial industry that manufactures, consumes and disseminates popular media texts. As emotional subjects hailed by the new orders of post-industrialisation, they seek a reconstituted set of desires by turning to the creative inter-subjective relations, practices, and space-making of romantic fiction, demonstrating the world-making powers of text and the imagination.

Meeting affective needs

Although now the preserve of female authors, the modern origins of Malaysian romantic fiction can be traced to the birth of the first Malay novel, The Story of Faridah Hanum [Hikayat Faridah Hanum], written by the male author Syed Sheikh al-Hadi. Published in 1925, it tells the story of thwarted love and the titular character’s struggle to liberate herself from a forced marriage. The novel was inspired by the early 20th century Arab-Muslim reformist movement and its calls for women’s emancipation from illiteracy and the shackles of traditional customs. Forced marriage has persisted as a melodramatic trope through many historical milestones of social change since the publication of al-Hadi’s landmark novel. The first Malay woman novelist, Rafiah Yusuf, also published her first book on the subject in 1941. The trope recaptured the public imagination in 2002 with the bestselling success of Fauziah Ashari’s Waves of Longing [Ombak Rindu]. Its enduring popularity, as seen in the various film, stage, and television adaptations in the subsequent years since its publication, has redefined local popular fiction into a genre that is preoccupied mainly with romance (Izharuddin Citation2021a). But it is the novel’s narrative crux that draws the most controversy. Like its progenitor, it is concerned with the turmoil of forced marriage. The protagonist, a young woman from a village, falls victim to a wealthy man who sexually assaults her. She is coerced into marrying him before eventually learning to develop pious acceptance (pasrah) and surrender to God’s will. Her spiritual revelation provides her with the strength to forgive and even fall in love with him.

In its contemporary iteration, the romance fiction publishing industry derives its commercial success from the circulation of ‘emotional capital’ or the ‘capacity to connect, involving acts, intentions, and sentiments’ with others the ‘moral thinking about personal connections and intimate life, related to the self and to others’ (Silva Citation2016, 145). The circulation of emotional capital in turn becomes a locus for meeting affective needs that are deemed excessive or transgressive. An exchange of affective resources occurs between the arbiters of romantic taste – authors, publishers and booksellers – and the emotionally deprived party – women who feel unfulfilled, who seek solutions to their personal problems and have a strong desire for emotional thrill. The item of exchange – romantic fiction – is much more than mere commodity. Romantic text activates emotions in the reader; the thicker the book, the more enjoyment the reader will feel. The quantity of books read also correlates with the enhancement of ‘feeling’ as avid readers can finish nearly ten novels a month to maintain their emotional ‘high’.

A focus on emotional capital and the social co-production of meaning between authors, readers, and publishers problematises simplistic questions often raised about romance writing: whether it is ‘empowering’, ‘feminist’, or simply ‘good’ for women. Critical opinion is split between recognising romance authors and readers ‘on their own terms’ (Radway Citation1984) and those that reject ‘postfeminist’ reflections on the appeal of the genre (Modleski Citation2008). Despite their undervalued status as ‘trashy’ and ‘domestic’, love stories play a significant role as ‘a less visible shock absorber’ of socioeconomic changes taking place in Southeast Asian society (Jones Citation2004, 510). The desire for emotions and ‘feeling’ closely mirrors individual articulations in Barbados where the neoliberal capitalist restructuring of society creates new affective possibilities (Freeman Citation2020). The appeal of locally-produced romantic fiction in Malaysia can be attributed to a rejection of western-style romance, a genre stereotypically conceived as overtly permissive in its depiction of pre-marital intimacy (Izharuddin Citation2020). Despite its oppositional orientation, however, it shares with western love stories similar cultural assumptions. The romance genre is generally disrespected as lowbrow and stigmatised for its idealistic preoccupation with love and its ambivalent construction of female sexuality (Lois and Gregson Citation2015). But those working within the genre see things differently. As Laura Struve (Citation2011) argues, no other literary genre requires as much defence from writers, readers, and sympathetic critics as romance fiction. In the relationship between author and readers, the author is the moral gatekeeper of romance and desire. Some regard their published work as tomes of wisdom and advice. Romance fiction, as the example in Nigeria shows (Larkin Citation2002), offers moral guidance to overcoming conflict in love and family life. Authors draw clear moral boundaries of respectability and propriety between women and men, which readers and fans may endorse as didactic material. For instance, a new lexical repertoire of intimacy is introduced in Malay romance consisting of Arabic words like ikhtilat that refer to mixed-gender associations and the Islamic imperative to regulate them (jaga ikhtilat).

It is important to note that unlike feminist, queer, or other counterpublics and their alignment with resistance, Malay romance does not necessarily create alternative discourses that challenge dominant ideological assumptions but fosters instead a space for the revaluation of under-appreciated cultural ideas about women’s predisposition to emotion and care. There is an acceptance, among readers and authors, that the burden of emotion work falls on women and that pious suffering is a sine qua non of moral Muslim femininity (Izharuddin Citation2021a, Citation2021b). In lieu of dissent and opposition to the cultural frameworks of gender and emotions, Malay romance makes visible the often invisible relations and practices of care and intimacy. At its most dramatic, it transmutes pious suffering into catharsis and pleasure. For women who feel a deficit of intimacy in their marriage, romance novels can supply them with emotional self-sufficiency. A fiction editor interviewed for this study, Juliana, agrees: ‘I have this belief that many Malay women are secretly unhappy in their marriage. Therefore, they find solace in these novels, because I notice in some of the novels, there is always a knight in shining armour, someone who would rescue them and love them, and then they will live happily ever after together.’ She comments that romance novels function like self-help guidebooks that ‘portray different ideas of how a [Muslim] marriage works.’ The genre is peppered with Islamic messages directed to the female reader who is expected to manage her emotions, at times suppressing them, when faced with challenging marital situations: ‘There’s also some not so subtle religious “preaching” in most Malay novels, where women are reminded to must submit themselves to their husband no matter what.’

Another reader, Siti, whom I interviewed in a focus group discussion, agrees with Juliana. Romance fiction provides her with an accessible and sustainable resource for emotional fulfilment that supplements and competes with bureaucratic discourses on marriage. Informed by a new lexicon of intimacy, it compels her to take personal responsibility to revive the feeling of love that might have waned in her marriage. She says to me, ‘We want to re-establish that love, don’t we? Love for our husband, that is. [Through reading] we get to feel that [romantic] emotion, that returns on its own.’ Her husband, however, refuses to participate in mediated intimacy for the benefit of their marriage: ‘He doesn’t like reading. Typical men. He was never interested in these kinds of novels. For him, he’d say, “Hah, why would I tire myself reading novels?”’ Romantic fiction offers more than just emotional supplement. In the next section, I demonstrate how friendship and sociality are forged through the co-manufactured ideals of romantic love in the counterpublics of care. The metaphor of co-production builds on Struve’s framing of the social reader (Citation2011) and ‘the way romance readers talk about their reading, the way they talk to each other, their connections to writers and publishers, [and] the way they use technology’ (Citation2011, 1289–1290). Similar to findings by Struve (Citation2011) and Krentz (Citation1996), the romance genre is developed through the overlapping roles of readers, authors, publishers, and booksellers. Authors and publishers tend to begin their careers in the romance industry as readers who later turn to penning, publishing and selling novels themselves. The outcomes of contributing to the development of the genre can be much more profound for some who turn to it for self-making and healing.

Space-making and self-making in the material counterpublics of care

Social practices of romantic fiction re-distribute gendered and racialised space in ways that generate comforting emotions and intimacy. Contemporary reformulations of emotions identify their social and relational character, whereby emotions belong not to individuals nor reside within them but are distributed between bodies. Emotions are oriented and move towards some bodies and away from others (Ahmed Citation2004). In this dynamic conceptualisation, emotions have the capacity to fill and spread within and across social spaces. These reformulations in turn create new possibilities, diversions, and lexicons for romantic attachments, care, and intimacy that exceed the individual and the confines of the couple dyad. Emotional states defined by an orientation and attachments to objects within and across spaces illuminate the status of bodies that occupy them depending on their gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, age, (dis)ability and class. Differences within space determine whether or not love and emotional intimacy are possible and viable (Morrison, Johnston, and Longhurst Citation2013). These considerations displace values that get attached to simplistic divisions of ‘public’ and ‘private’ space, calling into question taken-for-granted assumptions that all individuals and groups would only feel comfort, cared for, and safe ‘at home.’ Furthermore, the spatialisation of romantic intimacy within material public spaces renders certain emotions more directly observable, ‘real’, and even tangible for individuals and groups who previously found them elusive.

Every year in April for two weeks up until the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, thousands throng to the capital city to attend the Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair. Within, most of the books sold are in the Malay language, making it less international than its name. Moreover, they are limited mainly to romantic fiction, Islamic texts and children’s books. But the bookfair has a carnival-like energy nonetheless, made palpable by the enthusiasm and excitement of its visitors, mainly women, who can be seen in this space dragging their suitcases to fill them with newly-purchased books. Their presence reconfigures the space, and so does their determination within it, which is to meet their favourite authors and seek out as many romance novels as possible, so much so that men can feel out of place in such a space ().

Figure 1. Readers queuing to purchase romance novels at the 2018 Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair. Photograph by the author.

The bookfair has become a pilgrimage site of sorts – for pilgrims of romance from all around the country. Having travelled from afar the annual bookfair is one occasion where they can meet in person to bond over a shared love for romantic fiction, a community connection maintained on social media platforms and official publicity websites of popular authors. After standing in long queues, readers meet and pay their respects to their favourite authors for whom they come bearing gifts, and with whom they take photos, kiss, and embrace. In these encounters, readers take the opportunity to speak to their idols in person, thanking them for their books. Dedicated followers of their work would volunteer at the bookfair in a coordinated fashion, dressed in matching-coloured tunics and hijab in their roles as booksellers and unofficial spokespersons to the public. These volunteers are mostly young women who developed their discernment as readers of the genre through their allegiance to particular authors.

The venue of the bookfair in question is the Putra World Trade Centre (PWTC), a place of cultural and political prestige. It is structurally fused to the towering headquarters of the United Malay National Organisation (UMNO), the dominant political party defined by its ethnic-based membership and agenda. Another instance of racialised space-making takes place in the location of Readers Heaven and Coffee, a bookshop visited by readers of romantic fiction (). It is located in Bandar Baru Bangi, Selangor, a pioneering ‘Islamic’ township located 30 km away from Kuala Lumpur and was developed in the 1970s for the residence of middle-class Malay professionals and their families. More recently, the township has become a site of Islamic consumption, frequented by consumers seeking luxury hijab and expensive prayer garments.

Figure 2. Readers Heaven and Coffee, a romance café and bookshop in Bandar Baru Bangi. Photograph by the author.

The bookshop is also where its co-owners, two sisters in their fifties, manage their romantic fiction imprint, Kaseh Aries. In their publishing enterprise are close friends who join them as company partners, sales promoters, reviewers, and editors, all of whom are pious middle-aged Malay women who wear the hijab. Eloquent and animated in speech, they are university-educated and keen readers of romance novels themselves who, after years of enjoying Mills & Boon paperbacks in their youth, discovered that their readers preferred stories that more closely reflected their cultural contexts. As independent publishers, they manage the vertical production of romance novels from the soliciting, reviewing, editing, and publishing of manuscripts, book cover design to the marketing of books in shops and annual bookfairs, including the Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair. The marketing consists of the creation of the novel’s title and cover design, and very importantly, the blurb on the back cover of the books – all of which are negotiated with the author. Rather than a synopsis, the blurb is typically an excerpted scene which functions as a teaser containing only a dramatic dialogue between the main characters. Under their company motto: ‘Kaseh … It’s all about love’, their publishing practices are carefully refined to serve as a conduit to romantic escape for readers with whom they cultivate a close transactional relationship. Their readers in turn maintain the relationship through frequent calls and text messages to the sales promoter, sometimes late into the night, to enquire about new additions to their catalogue.

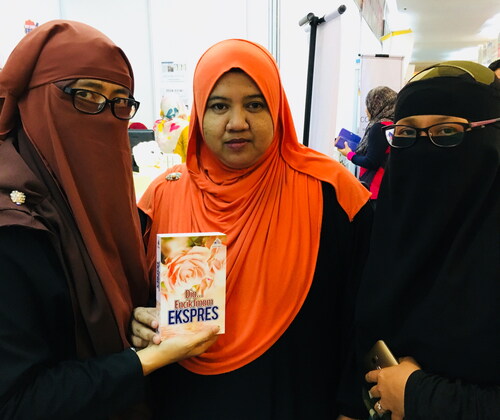

A programme highlight of Kaseh Aries’s stall at the annual bookfair is the book-signing session with their bestselling authors. Among them is the young author Cik Tet. On one occasion, Cik Tet offers her autograph to her fans, two women who wear the niqab (). They have enjoyed the author’s novel, He’s Mr. Imam Express [Dia Imam Ekspres], a breezy yet moral take on romantic love. The women were also drawn to the author’s down-to-earth persona and self-made success. Her success and fame, which have been amplified by popular television and film adaptations, are made more remarkable by her humble working-class background. Cik Tet began her writing career during her time as a homemaker after a brief employment as a supermarket cashier and factory worker. Her rise as a popular author suggests a degree of socioeconomic mobility available to women with literary aspirations. She stands apart, however, from other more highly-educated authors like Melur Jelita whose readership appreciate the elaborate world-building of her fiction informed by extensive research and her professional expertise in Islamic Studies.

Figure 3. Cik Tet (centre), a bestselling romance author, seen here flanked by her fans at the 2018 Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair. Photograph by the author.

The mediated intimacy of romantic fiction can be a template for the care of the self and self-making. A young woman I met at the bookfair, Hamizah, embodied the fully immersive, participatory attractions of romantic fiction through her performative mirroring and emulation which resonates to a degree with participants of fan and cosplay subcultures (Peirson-Smith Citation2013). She had been volunteering at a publisher’s stall with selling Melur Jelita’s novels and came dressed in a light blue tunic and hijab like her fellow volunteers. Her efforts at the bookfair were her expression of gratitude to the author for writing a novel that played a role in determining the course of her life. As a 15-year-old, Hamizah became so inspired by the adventures of a police cadet in a novel by Melur Jelita that she later enrolled in the Malaysian Royal Police Force training college and became one of the best-performing students in her graduating class, excelling in marching and the handling of weapons. More than 1,000 pages long, the novel follows the life and loves of Iris who volunteers as a teacher in a Cham-Malay village in Cambodia after attending police training college. Iris’s volunteering assignment becomes a journey of cultural and self (re)discovery as she establishes an Islamic and ethnic-Malay kinship with the Cham people. Read by the tens of thousands, the novel is not just a moral and aesthetic reference for self-making for a reader like Hamizah but it maps the relationship between text and reader onto the larger narrative of nationhood through ethnicity, religion, and the uniformed service. The care of the self, as defined by Foucault (Citation1986), constitutes ‘those intentional and voluntary actions by which men [sic] not only set themselves rules of conduct, but also seek to transform themselves, to change themselves in their singular being, and to make their life into an oeuvre’ (10). Believing that the novel gave her the permission to be a free agent, Hamizah had followed a path of self-making and care of the self based on the discourse of romance, one that carries the legitimacy of ethnic kinship and affective nationhood.

By returning to Murni once again, who relies on romance novels to recover from the trials of a forced marriage and divorce, we find the significance of love narratives as a practical resource of care. The practice of reading and writing weaves into her intertextual self-making that involves comparing, emulating, and contrasting herself with fictional characters while at the same time recognising both the limits and agency she has as a woman. But it is the ‘curative’ properties of the novel that are crucial to her reparative self-making:

Murni: We cannot fight fate. But we try nonetheless to be like the characters in novels. Like me, I try to be like the protagonist in Finding Azizah [by Khadijah Hashim]. I want to attempt the ways she regains her strength, and how in the end she attains what she wants. […] We find strength through novels. For me, novels have an impact on me, for me to move on in life. The ‘cure’ comes from the novel. The novel is like a medicine. The best medicine is reading.

As medicine, fiction offers succour for readers who have battled with personal pain. But in Murni’s case reading constitutes a passionate attachment to narratives that could lead to accusations of female excess; of feeling ‘too much’ from ‘too many’ books that are ‘too big’, ultimately derailing her from domestic responsibilities. Despite its potential excesses, the cultural work of reading Malay romance fiction, which can involve comparing, emulating, and contrasting oneself in relation to textual material, and its injunction to readers to be ‘good’ and self-abnegating Muslim women can be productively and compatibly juxtaposed with the sacred place of reading or iqra in Islam.

Bookfairs and bookshops are spaces of self-making and sociality committed to Malay romance. However, their location in places associated with racialised politics and socioeconomic progress to the direct and indirect exclusion of other ethnic minorities indicate a gendered complicity in the geography of racial difference. This is not to say that the meanings and power attached to such places are forever fixed. Rather, the social operations of Malay romance rely and benefit from the geography of racial difference and have the potential to remake the meaning of those spaces. A community-building ethos and structural laterality lend themselves well to the romance industry’s mission and formation as a counterpublic that addresses its participants as Muslims, students, workers, mothers, and wives. In addition to the wellspring of relief, solidarity and hope the genre offers, it enables possibilities for decentering and subverting male protectionism as the source of care in Islam. Put another way, the social spaces and textual culture of the romance industry provide opportunities for women to become other women’s guardians and providers of emotional care.

Conclusion

This article pays attention to the multiple ways idealised meanings of romantic love and intimacy are co-produced and circulated through the emergent desires, practices, spaces and selves capitalised by the Malay romance industry. It acknowledges the truism that love alone isn’t enough, owing to the fact that the socio-literary relations of romance fiction are sustained by entrepreneurial selves, collectives, and spaces that accommodate and push against religious bureaucracy and cultural formations that delimit emotional subjectivity. Murni and other women discussed in this article articulate a desire for feeling, care and romantic fulfillment in their lives. They speak to an emergent moment whereby the post-industrial restructuring of economies hails new gendered neoliberal subjectivities to the fore. The attractions and success of the genre also complicate the gendered neoliberal experience. On the one hand it hails the newly desiring subject to take personal responsibility for the management of their own emotions. But on the other hand, these new desires for feeling have necessitated inter-subjective and co-productive communal affective experiences without which the rewards of romance might be unimaginable. Care, pleasure, and other recuperative emotions found in spaces marked by ethnic and religious preeminence demonstrate the way in which counterpublics are not reducible to place or identity nor are they necessarily mobilised for oppositional politics. Rather, counterpublics of care are created through the enmeshment of alternative publics within dominant ones where strangers come together equipped with a set of cultural competencies to meet their affective needs. It is a testament to the dynamic, distributive, and contagious potential of romantic fiction across different spaces.

Acknowledgements

Sections of this article were presented at the International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS) in Leiden and the European Association for Southeast Asian Studies conference in Berlin, both in 2019, the Harvard Divinity School public lecture in October 2019, and the Gatty Lecture at Cornell University in December 2019. The author would like to express her deepest appreciation to her colleagues at the Women’s Studies in Religion Program at the Harvard Divinity School and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alicia Izharuddin

Alicia Izharuddin is a Research Fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies at Leiden University. She has published in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Indonesia and the Malay World, Asian Cinema, Feminist Media Studies, among other journals. Her first book is Gender and Islam in Indonesian Cinema and she is currently writing her second book on the print culture of romance.

References

- Abu Lughod, Lila. 1986. Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in a Bedouin Society. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Abu Lughod, Lila. 2005. Dramas of Nationhood: The Politics of Television in Egypt. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press.

- Asen, Robert. 2000. “Seeking the “Counter” in Counterpublics.” Communication Theory 10 (4): 424–446. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2000.tb00201.x.

- Basarudin, Azza. 2016. Humanizing the Sacred: Sisters in Islam and the Struggle for Gender Justice in Malaysia. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2008. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 1986. The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure. New York: Vintage.

- Fraser, Nancy. 1992. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” In Habermas and the Public Sphere, edited by Craig Calhoun, 109–142. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Freeman, Carla. 2020. “Feeling Neoliberal.” Feminist Anthropology 1 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1002/fea2.12010.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1998. “Deep Hanging Out.” The New York Review of Books 45 (16): 69–72.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2009. “Lad Lit as Mediated Intimacy: A Postfeminist Tale of Female Power, Male Vulnerability and Roast.” Working Papers on the Web, 1–19.

- Gilligan, Carol. 1987. In A Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hirsch, Jennifer, and Holly Wardlow. 2006. Modern Loves: The Anthropology of Romantic Courtship and Companionate Marriage. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Hochschild, Arlie R. 2012. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Inhorn, Marcia, et al. 2007. “Loving Your Infertile Muslim Spouse: Notes on the Globalization of IVF and Its Romantic Commitments in Sunni Egypt and Shia Lebanon.” In Love and Globalization: Transformations of Intimacy in the Contemporary World, edited by Jennifer Hirsch, 139–160. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Izharuddin, Alicia. 2020. “Sweet Surrender: The Ethno-Religious Spaces of Malay Romance.” In Paper & Text: The Trials and Trade of Malaysian Literature, edited by William Tham Wai Liang, 33–50. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Gerakbudaya Enterprise.

- Izharuddin, Alicia. 2021a. “Redha Tu Ikhlas”: The Social-Textual Significance of Islamic Virtue in Malay Forced Marriage Narratives.” Religions 12 (5): 310–382. doi:10.3390/rel12050310.

- Izharuddin, Alicia. 2021b. “Reading the Digital Muslim Romance.” CyberOrient 15 (1): 146–171. doi:10.1002/cyo2.10.

- Jones, Carla. 2004. “Whose Stress? Emotion Work in Middle-Class Javanese Homes.” Ethnos 69 (4): 509–528. doi:10.1080/0014184042000302326.

- Karim, Wazir Jahan. 1990. Emotions of Culture: A Malay Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- King, Ross. 2008. Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya: Negotiating Urban Space in Malaysia. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

- Krentz, Jayne Ann. 1996. Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women: Romance Writers on the Appeal of Romance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Larkin, Brian. 2002. “Indian Films and Nigerian Lovers: Media and the Creation of Parallel Modernities.” In Readings in African Popular Fiction, edited by Stephanie Newell, 18–32. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Lois, Jennifer, and Joanna Gregson. 2015. “Sneers and Leers: Romance Writers and Gendered Sexual Stigma.” Gender & Society 29 (4): 459–483. doi:10.1177/0891243215584603.

- Masquelier, Adeline. 2009. Women and Islamic Revival in a West African Town. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Millner, Michael. 2012. Fever Reading: Affect and Reading Badly in the Early American Public Sphere. Durham: University of New Hampshire Press.

- Modleski, Tania. 2008. Loving with a Vengeance: Mass-Produced Fantasies for Women. 2nd ed. New York and London: Routledge.

- Mohamad, Maznah. 2011. “Malaysian Shariah Reforms in Flux: The Changeable National Character of Islamic Marriage.” International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 25 (1): 46–70. doi:10.1093/lawfam/ebq016.

- Mohamad, Maznah. 2020. The Divine Bureaucracy and Disenchantment of Social Life: A Study of Bureaucratic Islam in Malaysia. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mohamad, Maznah, and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied. 2013. “Introduction.” In Melayu: The Politics, Poetics, and Paradoxes of Malayness, edited by Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

- Morrison, Carey-Ann, Lynda Johnston, and Robyn Longhurst. 2013. “Critical Geographies of Love as Spatial, Relational and Political.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (4): 505–521. doi:10.1177/0309132512462513.

- Ong, Aihwa. 1987. Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory Women in Malaysia. Albany: State University of New York.

- Padilla, Mark B., Jennifer S. Hirsch, Miguel Muñoz-Laboy, Robert E. Sember, and Richard G. Parker. 2007. Love and Globalization: Transformations of Intimacy in the Contemporary World. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Peirson-Smith, Anne. 2013. “Fashioning the Fantastical Self: An Examination of the Cosplay Dress-up Phenomenon in Southeast Asia.” Fashion Theory 17 (1): 77–111.

- Peletz, Michael G. 1996. Reason and Passion: Representations of Gender in a Malay Society. Berkeley and Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

- Radway, Janice. 1984. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy and Popular Culture. Durham, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Rosaldo, Michelle. 1984. “Towards an Anthropology of Self and Feeling.” In Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion, edited by Richard A. Shweder, Robert Alan Le Vine, and Robert A. Le Vine, 137–157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Silva, Elizabeth B. 2016. “Gender, Class, Emotional Capital and Consumption in Family Life.” In Gender and Consumption: Domestic Cultures and the Commercialisation of Everyday Life, edited by Lydia Martens and Emma Casey, 141–159. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sloane-White, Patricia. 2017. Corporate Islam: Sharia and the Modern Workplace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stivens, Maila. 2006. “Family Values’ and Islamic Revival: Gender, Rights, and State Moral Projects in Malaysia.” Women’s Studies International Forum 29 (4): 354–367. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2006.05.007.

- Struve, Laura. 2011. “Sisters of Sorts: Reading Romantic Fiction and the Bonds among Female Readers.” The Journal of Popular Culture 44 (6): 1289–1306. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5931.2011.00901.x.

- Suratnam, Suriani. 2021. “Skills for “Marriage of a Lifetime”: an Examination of Muslim Marriage Preparation Handbooks in Singapore, 1974 to 2018.” Religions 12 (7): 473.

- Tan, Zi Hao. 2020. “Xenophobic Malaysia, Truly Asia: Metonym for the Invisible.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 21 (4): 601–613. doi:10.1080/14649373.2020.1835101.

- Taylor, Charles. 1995. Philosophical Arguments. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- UNESCO. 2020. “Kuala Lumpur named World Book Capital 2020.” Accessed 6 October 2021. https://en.unesco.org/world-book-capital-city-2020.

- Warner, Michael. 2002. “Publics and Counterpublics.” Public Culture 14 (1): 49–90. doi:10.1215/08992363-14-1-49.