Abstract

This paper uses a feminist approach to geography to critique the theory of ‘open city’ proposed by Richard Sennett in his 2018 book, Building and Dwelling, which suggests a series of design interventions that when applied to cities can lead to an increase in sociability, complexity and tolerance of difference. Tehran is employed as a case study to examine whether open city theory is yet another Western formulation that is only applicable in democratic contexts. Considering Tehran’s top-down, oppressive, and authoritarian setting, it is seen here as a context in which the closedness and lack of active urban life in its streets and other public places are not only the result of architectural and planning schemes inherited from the ‘functional city’, as open city theory suggests, but instead are the result of rigid, top-down control mechanisms applied by the authorities. Therefore, based on feminist critical approaches such as meaning-in-context, and considering the discriminatory politics faced by women in their use of and access to public spaces in Iran, I challenge open city theory by suggesting that closedness, and its opposite, openness, are terms too charged with a Western sense of urbanisation. Instead, by examining the meaning, practicality and temporality of some of Sennett’s design interventions in Tehran, I suggest other potential ways that openness might occur; not through design, however, but among people and the solutions they find to overcome closedness in this city.

Introduction

Since the 1970s, with the rise of feminist critiques of urban theory and planning, [bourgeois] urban planners have been accused of creating gender-blind environments. Under the influence of post-colonial, feminist and subaltern studies of urbanisation, the heteropatriarchal norms of urbanisation that originated in the western countries have been challenged and urban planners have begun to encounter the urban trajectories of places and spaces beyond the European cities of the north hemisphere (see Massey Citation1994; Derickson Citation2015; Brenner and Schmid Citation2015). Massey (Citation1994) for instance, argues that European male theorists’ attempt to construct an urban knowledge from a positivist encounter with urban places is insufficient on its own, as other places and spaces beyond European cities come into existence with their own social meanings, identities and political economies. Critiquing planetary urbanisation, Derickson (Citation2015) contests the category of the urban in the ‘ideological totalisations of urban age discourse’ (see Brenner and Schmid Citation2015, 160) to address a broader tradition of reflexive theorising of the urban. Feminist geographers then have begun to offer normative frameworks for imagining space as gendered, claiming that such gendering has profound consequences for women (see McDowell Citation1983; Wolf Citation1985; Fraser Citation2005). Through the lens of feminist urban studies, Wolf (Citation1985, 38–40), for instance, challenged the ‘careless patriarchal use of language’ in theories that revolve around the binaries of public/private, culture/nature and masculine/feminine, and identified new patterns of experience and behaviour in the contemporary city and society. McDowell (Citation1997, 382) has also investigated ‘the actions and meanings of gendered people… their histories, personalities and biographies… the meaning of places to them… the different ways in which spaces are gendered and how this affects people’s understandings of themselves as women or men’.

However, this challenge was not limited to western feminist geographers. Post-colonial feminist geographers, such as Mahmood (Citation2001, Citation2005) and Abaza (Citation2014, 2016) also draw attention to the unexpected ways in which women use public spaces in Muslim countries, saying that they need a new way of interpreting social and urban investigations. By exploring the ‘women’s mosque movement’ in Cairo, for instance, Mahmood (Citation2001) has attained a new understanding of women’s agency in the public spaces of Muslim countries that goes beyond the simplistic registers of submission and patriarchy that appear constantly in Western literature, inspired by Janice Boddy’s ethnographic account of Sudanese women’s zar cult, which serves as a counter-hegemonic, feminine response to the hegemonic praxis that sets limits on male domination (in Mahmood Citation2001, 206). Abaza (Citation2014) also points out that when it comes to the Islamic urban context, gender and the study of the visibility and experience of women matter in a quite significant way, as women are in ‘constant competition for public visibility and conquering public space’.

But it is also important to note that the geography, history, culture and politics of Muslim cities are so different from one another that it would not be sufficient to categorise all of them under a single umbrella of Muslim-ness. Many scholars argue that ‘Islam is not a simple religious phenomenon but different social and cultural constructions in different countries, that cannot be forced into a simple category of ‘the Muslim world’ and therefore ‘Muslim societies and their modern histories are as diverse and multiple as any other’ (Kamali Citation2007, 378). Iranian scholars have also tried to remove its cities from the general category of ‘Islamic cities’ that appeared in the works of Western scholars such as Hugh Roberts and Blake and Lawless in the late 1970s (see Keddie Citation2007; Milani Citation1992; Amin Citation2002; Najmabadi Citation2005; Miraftab Citation2007; Khatam Citation2009). Milani (Citation1992), for instance, has analysed the different layers of meaning that Iranian women attach to every word, gesture and action, while Keddie (Citation2007, 17) points out the greater ‘freedoms of Iranian women as compared to the women in several other Middle Eastern countries’. Amin (Citation2002) has also shed light on the history and emergence of the modern Iranian woman in mid-Victorian times by documenting the first women’s movement there in the nineteenth century, while Najmabadi (Citation2005) has reflected on the Iranian Constitutional Revolution in the early twentieth century to measure the social progress of women’s participation in public life. This was at a time when some other Iranian scholars began to reflect on geographical location and gender identity in Iran, beyond the question of the traditional separation of private and public spheres (Miraftab Citation2007), and identified the everyday struggle and resistance of Iranian women in the oppressive political climate of the country (Khatam Citation2009).

Nonetheless, in general, urban planning schemes had begun to shift by the 1980s and 90 s, as the globalisation of labour and capital flows, the transformation of production and political economy, and shifts in the modes of ownership and land control, all changed cities into a forum in which people could learn to live with strangers, develop multiple images of their own identities, and experience a condition of alterity. The biggest barrier to achieving this ideal, however, was modern capitalism and the idea of a ‘healthy society’, which filled cities with gated communities, walls, fences and ubiquitous CCTVs. Although largely limited to theoretical assumptions, urban planning in the twenty-first century found solutions to overcome these problems. By distancing themselves from a set of practices that exclude citizens’ voices in the planning process, new approaches are moving towards participatory collaboration and engagement between citizens, communities, architects, planners and other decision makers (see Amin Citation2008; Sendra Citation2015; Sennett Citation2018). Instead of examining their work, this paper focuses on the theoretical assumptions of open city theory suggested by Richard Sennett. The theory revolves around the themes of inclusion, complexity and social interaction in cities that, according to Sennett (Citation2018), can be achieved through a set of design interventions. It is a theory that tackles the issues of public division, segregation, gating, exclusion and lack of tolerance of the ‘other’. Although the discourse of social inclusion and mixity in cities began in post-WWII urbanism – mainly in European cities as a response to the post-war housing shortage (see Minton Citation2012) – it was not until 2006 that Richard Sennett, alongside Ricky Burdett, Joan Clos and Saskia Sassen, offered a picture of a designable open city to the Urban Age conference in Berlin.

This paper looks at Sennett’s open city theory from a feminist perspective to argue that it is limited. The question is whether the terms open and closed are a set of concepts, phenomena, or metaphors that, like a common language among Western scholars, describe – or more accurately, contest – only the neoliberal, privatised and capitalist model of urbanisation developed in the West. The question here is how cities governed by undemocratic powers – in which a specific model of space is [re]produced and limited ways of using spaces are dictated from above – can fit into this Western rhetoric? Do we have a language for this yet, or can we instead look at this theory from different sociopolitical perspectives? This is to suggest that by focusing only on Western [urban] problems – namely the neoliberal and private ownership of public lands, gated communities, CCTV surveillance and so on – urban actors, decision makers, and planners in the West are prevented from seeing alternative relations, narratives, and new possibilities in spatial and institutional systems developed in cities like Tehran, which are governed by a specific type of political Islam (for a detailed analysis of the wide spectrum of Iranian models of political Islam see Mozaffari (2007) on totalitarianism/clerical fascism, Chehabi (Citation2001) on authoritarianism, Arjomand (1988) on revolutionary traditionalism, Schirazi (Citation1992) on clerical totalitarianism, and so on). This is not, however, the first time that the notion of open city has been criticised. Kees Christiaanse (an architect and urban planner from the Netherlands) has to some extent raised the same question. He emphasises that ‘if open city is only a good city for all, then there is no possibility to see its values in the totalitarian cities where people have to deal with the city according to what totalitarian authorities want’. ‘On the contrary’, he continues, ‘the open city is a volatile situation that can create balance between the forces of integration and disintegration’ (Christiaanse Citation2011). He reminds us that totalitarian cities are vivid and active as a result of the underground networks that allow the development of a subculture that makes for productive urban districts. Brenner (Citation2013) and Harvey (Citation2012) also made critique of the open city by indicating that ‘open city’, in general, is ‘an ideology which masks, or perhaps merely softens, the forms of top-down planning, market-dominated governance, sociospatial exclusion and displacement’ (Brenner Citation2013, 44). For both Brenner and Harvey, it is in fact, Lefebvre’s right to the city that ‘powerfully resonates with contemporary debates among designers on the open city, because’, as Brenner (Citation2013, 45) suggests, ‘it likewise envisions a city that is appropriated by and accessible to all inhabitants’.

In elaborating these sorts of point of views, this paper takes Tehran, the capital of Iran, as a case study, and examines the meaning, practicality and temporality of open city theory in its socio-political context. The aim is to show that in shedding light mostly on the architectural and planning dimensions of the use of public spaces, open city theory does not pay enough attention to other dimensions of discrimination, segregation and lack of interaction in public spaces that affects marginalised groups in such cities. It is worth considering that due to the high level of sensitivity, censorship and lack of accurate data on non-binary gender identities in the context of Iran, ‘marginalised groups’ in this paper refers only to women and young people. This is because non-binary gender identities, including gays, lesbians, and bi-sexuals, are usually subjected to compulsory therapeutic, hormonal or surgical procedures to change their gender identity both mentally and physically, or else to ‘Honour Killing’, which performs under the banner of Femicide in Iran to target wives and female family members who are perceived by male family members to have brought dishonour upon the family. Fatemeh Hassani, a women’s rights activist, in a France 24 report published last year, said that ‘there are between 375 and 450 honour killings in Iran every year’ which according to the Iranian official statistics forms some 20% of all homicides. ‘However’, she continues, ‘we are convinced that the real number of honour killings is higher, because many of these murders are counted as suicides or accidents. Other crimes are even forgotten because no one files a complaint or follows up with the case’ (Ershad Citation2022). Nevertheless, this study suggests other potential ways in which openness can be experienced that might not necessarily fit open city theory, even though they have the same result of increasing the presence and interaction of those who face limitations and discrimination in public spaces. The first part of the argument looks at gender-segregated spaces in Tehran, such as women-only parks and bra shops, offering a critical view of the rigid, top-down mechanisms of control over the female body in Iranian cities. The aim is to re-configure the ‘meaning-in-context’, as Lips (Citation2003) would argue, and to offer alternative perspectives through which porosity (one design intervention of open city theory) is achieved, not by design but by people. From there, I examine the temporality of multiple-seed planning which, when applied, brings the rich to poorer areas and therefore increases the possibility of interaction among different sorts of people. Through an exploration of the Bahman Cultural Centre in south Tehran, I show how the expansion of public transport and the mushrooming of shopping malls in the city has led to the Centre becoming less popular among Tehrani citizens, with the result that it has ceased to be the motor of social mobility from north to south Tehran.

Open city theory

Open city was an experiment that played out in practice for the first time in WWII, designating a city that remained neutral in the war and therefore abandoned all attempts to defend itself against invasion by an occupying army, as in Roberto Rossellini’s 1945 film Rome, Open City. Later, by the 1960s, activists and leaders including Martin Luther King Jr, and the Chicago Freedom Movement, became more interested in this concept and used it to promote equality in American society (Mogilevich Citation2012). It could be said that the 1970s somehow mark the emergence of the open city in urban planning, as a challenge to modernist urbanism and urban renewal and in reaction to an ever-expanding suburban lifestyle that brought with it the spectre of undemocratic conformity, homogeneity, and exclusivity. The activists’ aim was to revive the city as the locus of a freedom that provides a form of public life that is elective, yet still founded in relations of co-presence (Mogilevich Citation2012, 20); to create a city with a public life in which people were free to step outside their own concerns and acknowledge the presence and needs of others. And of course, all western societies with long histories of democracy were able to promote this vision of cities, which was taken from American planners and scholars including Jane Jacobs, John V. Lindsay and Richard Sennett, as well as European architects and planners such as Kees Christiaanse, Tim Rieniets, Angelelus Eisinger, and Dieter Läpple. In his book Building and Dwelling; Ethics for the City (2018), Sennett discusses five interventions designed to tackle the issues of segregation, lack of interaction between different types of people and lack of complexity and experiments in cities. His five design strategies – known as synchronous form, punctuated-monumental markers, porosity, incomplete form, and seed-planning – value the potential of urban design, disorder, porosity, informality and experience.

Five design strategies

Sennett (Citation2018) outlines his five design strategies as follows:

The synchronous form is a way to plan activities in cities, inviting people to gather and mix by creating spaces in which many different social activities can go on at once. Punctuated-monumental markers are ways of creating distinctiveness and inviting people to pause and reflect on synchronic spaces in the city. Markers can be obelisks or can be created by changing the scale of and activities in streets at their crossroads, or through ‘quote marks’ such as benches in front of an ordinary building that give people opportunity to sit, pause and reflect. Sennett uses porosity – the idea of a membrane (2018, 218) as a metaphor to indicate that a building can be porous like a sponge ‘when there is an open flow between inside and outside while yet the structure retains the shape of its function and form’. He also refers to the distinction between border and boundary in natural ecology, in which a boundary is an edge where things end, whereas a border is an active edge where different groups interact. In the modern city, boundaries are created either by zoning regulations or by different forms of residential development such as gated communities. The idea of incomplete form is in fact a strategy for not imposing a predesigned agenda. The Chilean architect, Alejandro Aravena, for example, creates in Iquique a project of incomplete forms; a row of two storey houses, as if ‘half the first and second storey of buildings are walled in’, allowing the maximum flexibility in filling in the space. Multiple-seed planning refers to the creation of public spaces in poor areas that have a distinctive character, including schools, libraries, shops or parks, as a way to open up communities, to create a complex image or add value and encourage others to come.

For Sennett (Citation2018) open city is a city that contests modernism’s functionality and neoliberalism’s ‘closed system’ which both aim to integrate, control and order. But Sennett does not say whether his ideas are practical in the harsh political climate of authoritarian/totalitarian cities. And even if one considers his design interventions as apolitical strategies that can be applied everywhere, does that mean that they will increase inclusion, complexity, diversity and social interaction in the way Sennett predicts? Taking Tehran as an example, this study shows that even if some architectural and planning strategies create open physical environments, public spaces such as urban squares, parks, galleries, libraries, and so on, cannot be designated for democratic use (or what open city theory refers to as ‘inclusion’), because city dwellers, particularly women, have to follow certain codes dictated by the authorities. While the nature of these codes is restrictive, this study shows how women re-define these discriminatory codes and temporarily open up the closed city through their actions, behaviours and bodily gestures.

A feminist critique of Sennett

Since the 1970s, drawing upon cultural, post-structural, postcolonial, and psychoanalytic theories, the feminist critique of urban theory and planning has begun to pay attention to the everyday life and multiple spatial tactics of marginalised city dwellers (Haraway Citation1991; McDowell Citation1997; Massey Citation1994, 2005; Kwan Citation2002; Fraser Citation1990). Feminist geographers have recognised ‘the importance of critical reflections on one’s subject position relative to research participants, the research process, and the knowledge produced (reflexivity)’ (Kwan Citation2002). Instead of assuming that all knowledge must be acquired through knowers who are situated in particular subject positions and social contexts (Haraway Citation1991), feminist geographers argued for the partiality and situatedness of all knowledge (Kwan Citation2002). This means that by focusing on the individual and on social groups of gendered people on the one hand, and on the institutional and legal framework of a society on the other, it becomes possible to see the different ways in which the production of urban spaces becomes gendered, and how these affect the meanings of places to gendered people. McDowell (Citation1997, 382) argues that ‘doing feminist geography means looking at the actions and meanings of gendered people, at their histories, personalities and biographies, at the meaning of places to them, at the different ways in which spaces are gendered and how this affects people’s understating of themselves as women or men’. Needless to say, many male western scholars, among them Sennett, have been criticised in particular for their careless use of language in presenting the public person as obviously male. The most well-known instance was Janet Wolf, whose 1985 work The Invisible Flaneus targeted Sennett’s (Citation1976) The Fall of Public Man for its concept of the public domain and failure to consider gender differences. Another powerful argument is that of Nancy Fraser, who reflects on the appearance and visibility of members of subordinate social groups in urban public space, which she believes are synonymous with rejection and resistance.

Referring to what she calls ‘subaltern, multiple counterpublics’ (1990, 136), Fraser argues that in stratified societies – ‘societies whose basic institutional framework generates unequal social groups in structural relations of dominance and subordination’ (Fraser Citation1990, 66) – ‘arrangements that accommodate contestation among a plurality of competing publics better promote the ideal of participatory parity than does a single, comprehensive, overarching public’ (Fraser Citation1990, 136). She believes that in the ideal comprehensive public spaces [of democratic settings], members of subordinate groups have no arenas for deliberating among themselves about their needs, objectives and strategies, although ‘members of subordinated social groups have repeatedly found it advantageous to constitute alternative publics’ in stratified societies (Fraser Citation1990, 137). This approach to alternative publics brings into question Sennett’s suggestion for designing synchronic space as an intense, mixed and complex spot in the city in which all classes, races and religions can mix with each other. Sennett’s suggestion can be questioned, in particular, when the context is an authoritarian city like Tehran where public and private spaces are under the top-down mechanisms of religious discipline and control. Perhaps therefore, instead of understanding openness and closedness as merely design-related urban conditions, scholars need to pay attention to other discriminatory and lawful forces against women and other marginalised groups in order to understand the alternative and innovative ways created by these groups to access, stay in and use public and private spaces.

This is not, however, the first time that the discussion of women’s visibility/invisibility in the public spaces of Middle-Eastern societies has been debated. For instance, Cairo has witnessed different levels of intervention, manipulation, and re-definition of public and private spaces by women and other marginalized groups, including the LGBTQ community. Abaza (Citation2014) shows how, similar to the Green Movement in Tehran in 2009, women and youth in Cairo unexpectedly changed the models and codes of public, private and social life during the Arab Spring, re-claiming public spaces through non-violent protests including circulating information on the internet and illustrating their messages with graffiti on the walls of the city. Billaud (Citation2009) also reflects on the creative strategies of dissimulation used by Afghan women in Kabul to get public recognition, become visible under their veils, and challenge the gender hierarchies that underlie the appearance of compliance and conformity. Mahmood’s ethnography of an urban women’s mosque movement in Cairo is another powerful account, in which so-called ‘religious’ women’s behavioural codes, agency and embodied actions were articulated against the hegemonic, patriarchal, religious traditions and expressed their political and moral autonomy in the face of power (Mahmood Citation2001, 203).

This, in turn, offers a novel perspective on the relationships people make with their environment in cities under oppressive and restrictive forces, in the sense that public space – instead of offering citizens a platform, a stage to come together, debate and protest for their political and social needs – becomes a space of resistance and contestation full of quiet tactics to transgress, manipulate, and re-define the codes and use of public and private spaces.

One of these tactics, for instance, emerged in Tehran in 1997, when a new movement, led by Mohammad Khatami (Iran’s president between 1997 and 2005), known as the Reformist movement, put an end, however temporarily, to an era of extreme post-revolutionary suppression. The latter era had begun in 1979, when the Islamic Revolution imposed harsh and discriminatory policies of gender segregation in public spaces, and resulted in widening the male/female distinction. From the early 1980s, for instance, hijab became mandatory, mixed schools were suspended, and public offices and later public transport became gender segregated. The hegemonic disciplinary programme of Amr-e be Ma’ruf va Nahy-e az Monkar (which literally means ‘commanding what is just and forbidding what is wrong’) began to create social order and enforce corporeal regulations both in public and in the private sphere of homes. Reading the post-revolutionary climate of Iran in the light of Foucault’s account of biopower (2008) helps one to understand how the new Islamic state saw both physical bodies, and their non-physical entities, as subjects to be disciplined and transformed – from westernised bodies and minds (trained in the previous regime of a dictatorship) to Islamic bodies and minds with higher Islamic capabilities. They achieved this by increasing the docility of the body and integrating it into the Islamic system of control. Tehran and its streets became the first place to practice and manifest all these mechanisms of inclusion/exclusion, inside/outside, open/closed. In every corner of the post-revolutionary city, in the streets and squares, in front of schools or in cafés, especially in the better off neighbourhoods of north Tehran in which the supposedly more westernised and secular population was settled, were individuals whose role was to place limits on the people’s rights, especially the rights of women and young people. Called Pasdaran and Basij, they were trained in sophisticated riot-control techniques, organised to work with the secret police, and equipped with the latest weapons to spy, control, and repress the dissenting urban population for its improper behaviours and appearance. As the central power, Khomeini (the leader of the Islamic Revolution), wanted to regulate post-revolutionary space in line with Islamic ideology, in which only a certain dress code, manner, and type of bodily movement was acceptable. Consequently, the female body was compelled to be veiled, to become as invisible as possible in public spaces. Not only could women not wear obvious colours, make-up or perfume, or indeed anything that could attract attention to them (Amir-Ebrahimi Citation2006), there were also minor incidents in which men were caught wearing short-sleeved shirts (Afary Citation2009).

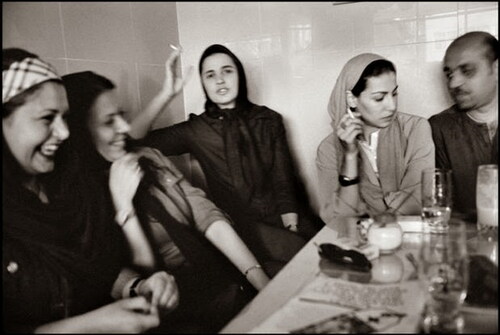

However, since the reformation era, women and young people have turned the rather less-extreme political climate of that period into an opportunity to increase their presence in physical and virtual spaces through the subtle or ‘velvet’ form of resistance and transgression of civil disobedience (nafarmani-ye madani) (Amir-Ebrahimi Citation2008, 94). This refers to women’s discovery of different ways to become more educated, active, and stylish, so that they began to re-define the definition of an ordinary Islamic woman. In the public spaces of Tehran, women began to subvert the force of compulsory hijab with something in between full-hijab (black chador) and no-hijab (see Amir-Ebrahimi Citation2006). The new-hijab that emerged during the reformation era was women’s new interpretation of covering themselves to re-signify and re-materialise the ideal Islamic dress code in different private, public, and semi-public/semi-private spaces. For instance, fashionable religious girls turned to new ‘Islamic chador’ in the streets and universities; a non-conventional veil, with two holes for their hands, that leaves the front loose and open. Non-religious, middle- and upper-class women in the streets and at universities also began to pull back their scarves and maqnaes (Islamic scarves), wear makeup, and polish their nails in bright colours (). In response, the authorities created new mechanisms of control to tackle these innovatory tactics, which have therefore been successful only to some extent. The morality police, created in 2005 when the conservative president Mahmood Ahmadinejad (who was in power between 2005 and 2013) took over from Khatami, is one such mechanism. This force consists of identical green and white vans full of male and female police that appear in the main squares and at the entrances of shopping malls. As soon as they appear, all [bad-hijab] women must fix their hijab, girls and boys must distance themselves, and laughter and loud voices must be controlled (Amir-Ebrahimi Citation2006, 4). Needless to say, the morality police are mostly installed in the most modern parts of the city, as all the disciplinary and controlling measures are already implemented by families and neighbourhoods in the more traditional districts of Tehran (Amir-Ebrahimi Citation2006). This alone is another image contradictory to the western context. In her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, Jane Jacob advocates ‘neighbourliness’ as a kind of DNA of street life, arguing that ‘local control’ or ‘the eyes on the street’ in West Village New York creates safe streets. In the context of Tehran, however, and in the small-scale traditional neighbourhoods where most people are known by others, local control and the eyes on the street of neighbours and family members remove ‘the space of anonymity’ and ‘freedom’ by controlling and judging every movement of women and youth (Amir-Ebrahimi Citation2006, 4).

Figure 1. ‘Hidden City’, photograph taken by Hoda Rostami (Citation2014).

So the question is, if open city is only a good city, if it is good for everyone, can we simply come to the conclusion that Tehran is a closed city because of all the laws and regulations that discriminate against women and marginalised groups? Can we not, instead, suggest that the idea of openness is too charged with a Western sense of urbanisation, because of which there is a need to look into other potential ways used by people to overcome closedness? These sorts of arguments, in fact, can be linked to the critical feminism of the 1980s, which pointed to the importance of exploring the social construction of meaning-in-context, and negotiated the meanings associated with a range of linguistic framings (Lips Citation2003). This, in turn, helps any research to reflect on the socially accepted or sanctioned codes for men and women in the city, based on the cultural characteristics and value system of societies (Lips Citation2003). This approach has been taken here to examine the meaning-in-context of some of Sennett’s design interventions in Tehran. Starting with porosity, some gender-segregated sites or boundaries in Tehran, such as a women-only park and a bra-shop, are used as examples to see how interactions that happen at the edges of these spaces are not the result of design interventions. From there, a café, as a semi-public/semi-private space, and taxi, as a public space, are used to illustrate different ways in which porosity happens in Tehran.

The women-only parks in Tehran and other Iranian cities have a low intensity gendered boundary at their edges. Created almost two decades ago in 2002, these women-only boundaries consist of three or four metre high solid walls, and usually one entrance controlled by guards, in order to limit both the male gaze and access to the inside. Considering that it is prohibited for women to exercise without covering their heads and bodies fully in mixed-gender parks, these enclosed spaces provided them with opportunities to exercise and rest, to improve their physical and mental health, enhance their social interactions and sunbathe without a hijab (Shahrokni Citation2014). Reading this phenomenon in the light of Foucault’s (Citation1999) account of biopolitics can also open further discussion on the control and discipline of female bodies in Iranian cities. This is because the authorities’ initial discourse regarding the urgency of opening these enclosed spaces revolved around issues of health and wellbeing, in the sense that ‘unhealthy’ female bodies were used as justification for building a high, solid wall around a piece of land and earmarking it for women only, to enable them to exercise and expose their skin to the sun without being seen by men (see Shahrokni Citation2014, 96). Other justifications included issues of women’s ‘safety’ in mixed public parks, as well as protecting them against ‘Western cultural invasion’. With reference to feminists’ meaning-in-context, the argument is that when it comes to gender-segregated women-only parks in Iran, porosity as a design intervention cannot retain its Western meaning and function. This is because under current rules and regulations in Iran, it is impossible to apply this design intervention and turn the solid wall of the park into a permeable edge at which men and women can interact with each other. Even locating different activities at the edges of the park is against the law. Arguably, however, porosity can be found in those temporary moments at which people turn the edges of the park into an active zone through unexpected, prohibited, and unofficial activities, such as meeting, walking, kissing and talking with the opposite sex outside the wall, or even in climbing up on the wall to get a glimpse of the women’s unveiled bodies inside.

It is the same with other women-only spaces in Tehran and other Iranian cities, such as bra-shops. The intensity and energy produced inside these women-only places leads to particular actions taking place inside and outside, which range from temporary homosexual intimacy among women inside to talking and interacting with men outside – ‘homosexual intimacy’ in the context of bra shops in Iran, as Aghdasifar (Citation2020, 3) explains, exists outside the limits of Western understandings of ‘homosexuality’ and stands ambiguously somewhere in-between current understandings of homosociality and homosexuality. This, in turn, challenges both the authorities’ production of homogeneous Islamic space and disciplined bodies, or space as a container of homogeneous and synchronous relations. It is because all these top-down, segregated spaces still contain a ‘complexity of networks, links, exchanges, connections from the intimate level of our daily lives’ (see Massey Citation2008, 17).

Like the women-only park, the initial aim of creating women-only bra shops was the creation of a bounded space for women so that they could try on products freely in the absence of the male gaze. However, these spaces are full of social rules and customary ways of interacting and relaxing. Bra shops are usually located on one floor of a shopping mall, such as Qaem Passage in Tajrish Square, or in the street. In all cases, the edges between inside and outside are rigidly defined so as not to allow men to enter. But this rigidity follows a seasonal rhythm, as in the hot days of summer, instead of a door, the main barrier becomes nothing more than a curtain between inside and outside. Reading this through the lens of open city theory, it can be said that the edges between the two states, inside/outside, becomes blurred. Even when rigidly marked in other seasons, the edges between the women-only space of the shop and the mixed-gender public space outside can be blurred easily and become permeable and porous enough ‘to expose the improperly dressed women to those on the street’ (Aghdasifar Citation2020, 5). This is due to the constant opening and closing of the front door at times when it is busy inside, allowing supposedly invisible female bodies to be seen momentarily from the outside. Especially at busy weekends, as Aghdasifar (Citation2020) argues, this contradicts the master image of the disciplined female body in the Islamic space of Tehran, as women feel free to unbutton manteaus, and remove chadors and headscarves, at the same time as an informal reciprocal arrangement between the occupants of each side of the bra-shop’s boundary has been made. This can refer to instances in which men wait outside, either to get a glimpse of what is happening inside or to engage in conversations with their partner inside, to choose their favourite lingerie, and even to discuss the price. In this way, exploring the unnoticed aspects of everyday interpersonal interactions inside women-only spaces in Tehran shows how fragile and flexible the edges of these gendered spaces can be, in the sense that while the authorities create gendered spaces behind segregated boundaries associated with a set of prefigured activities inside and outside, the combined flow of bodies, talk, energy, physical objects, mise en scènes, smells, touch and homosexual gestures, creates different spatial arrangements inside, at the edges, and outside.

Not only in women-only spaces, but even in semi-public/semi-private spaces in Tehran, such as cafés, people have learned how to create a space free from top-down forces, and to interact with each other without design interventions. And this is the case even though an Islamic and moral message regarding dress code and behaviour appears right at the entrance to cafés. The message is: ‘Observing Islamic Hijab Is Mandatory in This Place’. All cafés are obliged to put this Islamic order on an aluminium stand, piece of paper or any other medium, and install it at the entrance to warn people that Islamic rules are in force inside (). However, instead of working as a top-down force, these papers work usually like a clue, connoting that it is safer inside than outside from the presence of the morality police and that users can feel free inside. Within the enclosed spaces of cafés – where loud western music is usually played and various smells, from coffee to perfume to cigarettes, fill the [usually] dark and dim interior space – the feel and patterning of bodily movements are conveyed differently from those in the street. There is a level of freedom for ‘performance of the self’ (Susman Citation1979, 221) that is related to how people present themselves through their appearance, gestures and bodily demeanour – in their clothing, tone of voice, manner, posture, and the decoration of their bodies (see Featherstone Citation2010). Either in same-sex groups or among the opposite sex, it is mostly [upper] middle class men and women who occupy cafés. Their appearance – and especially that of women, with heavy makeup, loose scarves, colourful open manteaus, adornments, tattoos and piercings – creates a body image that in combination with their movements, control of their bodies, face-to-face interactions, presentation of self and ‘management of impression’ (in Featherstone Citation1991, 171), re-formulate the quality of Islamic/non-Islamic moral codes inside. The range of different actions (from office work to business meetings, to educational workshops, to music rehearsals, to chatting with the opposite sex), alongside ‘non-verbal communications’ (from facial expressions that suggest flirtation to different tones of voice, laughter, whispering and specific [male/female] bodily gestures in different sitting positions) all indicate a greater bodily consciousness and self-scrutiny in public life (see Featherstone Citation1991, 189) (). Nevertheless, this bodily consciousness and self-scrutiny can also be seen in the mobile and enclosed public spaces such as taxi, buses, or metro. Like many other cities, moving around by taxi, bus and metro develops the communicative and visual senses of both drivers and passengers. But in Tehran it goes beyond this, to also consist of a highly corporeal engagement of passengers with each other. Shared taxis for instance, are at all times subject to filling up with passengers regardless of gender, age or ethnicity, and up to 2005 two people were allowed to share the front passenger seat in taxis (Mehrnews Citation2005). New commuters replace those who get out of the taxi, either immediately or according to the driver’s will. This in turn increases the possibility of bodily contact among the passengers and is especially important in developing women’s consciousness as their bodies are usually kept alert when sitting next to a man. A small space shared with other four strangers makes for a highly sensory attachment to the inside. While some don Simmel’s blasé mask (everyday inexpressive blank faces), others (and especially women) react by marking a temporary boundary. When men sit so close that women can smell and feel their body odour, sweat and heat, or if men perform some specific bodily gesture, such as sitting with their legs open wide or rubbing their legs against a woman’s, women put either their bags or their shopping between the two bodies, so that a temporary boundary is made within the public space of the shared taxi. It can therefore be said that the enclosed space of shared taxis in Tehran is the opposite of Sennett’s porosity in which making a boundary reduces uninvited and unwelcome interactions (). It is worth noting that the act of temporary boundary-making is not a phenomenon limited to women using public transport. In fact, as Amir-Ebrahimi (Citation2016, 194) indicates, there is a long cultural tradition among Iranian families dating back to the emergence of modern architecture in the Pahlavi era, when courtyards were replaced by high-rise apartments. In the absent of private boundaries confined by walls, parks become places in which families could gather on different occasions, such as lunch in a Friday afternoon, or dinner on warm summer’s night. However, while sitting close to another family group [of strangers], there is no longer a wall, but only the ‘family picnic blanket’ to make a private boundary from which everyone else must distance themselves, respecting other families’ privacy by not looking at or talking to them. Thus, contra Sennett’s indication of porosity as a kind of positive solution that increases sociability and interaction by removing boundaries, here in Tehran and in other Iranian cities, the very opposite act of temporary boundary-making, enables women and families to feel better and comfortably access the city.A further point relates to the temporality and sustainability of some open city design interventions, such as multiple-seed planning, which refers to giving public spaces such as schools, libraries, shops or parks a distinctive architectural character in poor areas, in order to open up communities, create a complex image or add value, and to encourage others to visit. Although not under the banner of making the city open, this approach was practiced in Tehran back in the 1990s, when Tehran’s then mayor, Gholamhossein Karbaschi, began to prepare a strategic plan for the city (for the period 1996–2001) known as Tehran 80, which ‘marked a turning point in the history of the governance of Tehran’ (Vaghefi Citation2017, 242). He introduced a bold program of urban renewal and proposed policies to simultaneously integrate ‘Tehran’s fragmented and disillusioned population’ (Ehsani Citation1999, 22). To do this, he built new parks, shopping malls, department stores, cultural and sports centres, all of which relied on the ‘huge privatisation of services and, more importantly, selling the space of Tehran to private hands’ (Vaghefi Citation2017, 242).

Figure 3. Tehran Café, photograph taken by Abbas Attar (Citation2001).

Within four years, 138 cultural facilities and 27 sports cent res opened, and 1,300 vacant plots of land became neighbourhood sports fields, and more than half of these were in the deprived areas of south Tehran (Ehsani Citation1999, 25). Redistributing resources across the city’s fragmented geography, Karbaschi managed, to some extent, to disturb the historical polarisation of the city, known as the north/south binary, through projects such as the Bahman and Khavaran Cultural Complexes (see also Amir-Ebrahimi Citation1995). Offering classes in computer skills, calligraphy, musical instruction, aerobics and religion – which often were taught voluntarily by famous artists and craftsmen from north Tehran – Bahman Cultural Complex became very popular, especially for women, immediately after its construction in 1992, on the site of a former slaughterhouse in one of the poorest neighborhoods of the city. As a result, the north-south binary became less tangible since Karbaschi tripled the length of the highway system and doubled the amount of public transport through mega projects, such as Navab Project, that linked the two parts of the city by a major north-south commercial-administrative residential corridor (Ehsani Citation1999, 24–25). But, while this cultural center is still praised for its wider social impact in south Tehran, it is important to ask to what degree and in what ways Tehran municipality initiated such projects in the first place. This relates, according to Brenner (Citation2013), to the investment flows, property ownership structures and political decisions in the process of urban design. In the making of the Navab highway – that facilitated access to the Bahman complex from any point in the city – the mayor, in fact, bent the zoning laws to allow commercial land use in previously forbidden areas and issued construction permits for the subdivision of large plots and the construction of high-rises. Constructing Navab Project was not a simple attempt to link the geographically fragmented city. It torn apart the old fabric of the city that had coherent family and social ties and incorporated some 20 traditional mahallehs (see Vaghefi Citation2017, 252). Not to mention the displacement of the locals after its construction (Shirazi and Falahat Citation2019, 38). And this is where Sennett’s seed-planning design intervention falls short. Overemphasising, merely, the social impacts of these sorts of projects, which are highly rational and top down per se, shows that Sennett neglects the political and economic complexities behind the construction of such projects.

Another question is that, does Bahman Cultural Complex still create a reverse spatial mobility in the city, from north to south? The answer is no. It was an effective solution only so long as the expansion of freeways, expressways, public transport (both the metro and the bus) and the emergence of new luxury shopping malls and mega malls in the north and west of Tehran, weakened the north to south spatial mobility. It is estimated, according to Amir-Ebrahimi and Kazemi (Citation2019, 18), that there were 359 commercial complexes in Tehran by 2019. Of these, 11 were built before the revolution, 18 were built between 1979 and 1990, 82 between 1991 and 2005 under Karbaschi’s mayorship, and 163 since Ghalibaf became mayor of Tehran in 2005. Furthermore, there are 250 shopping centres (including small passages, shopping centres, malls, and mega malls) in north Tehran, 51 in the central districts, 42 in southern districts, and 17 in the new western districts known as Districts 21 and 22. As Amir-Ebrahimi and Kazemi (Citation2019, 29) have pointed out, most shopping centres are located in the northern districts 1, 2, and 3. This phenomenon – mushrooming malls and mega-malls in Tehran – is the result of various tactics, tools and innovations used by Tehran municipality to generate income: from changing land-use for a fee, to selling municipal land, to increasing property taxes and privatising some services and sectors of municipalities (Karampour Citation2018, 117). Nevertheless, similar phenomenon has happened in many other parts of the world, including Cairo (see Abaza Citation2014) and Japan (see Tamari Citation2006), where people (and especially women) pour into shopping centres, not to shop, but simply to stroll, to see, and to be seen. Because in the absense of interactive street life, women have learned how to transform the consumer spirit of the shopping malls into social spaces. In Tehran, the expansion of public transport made this process easier, so instead of going to the poorest area of town to use cultural facilities, women and young people prefer to travel to districts that offer different public places – including shopping centres, cafés and other semi-public/semi-private spaces such as galleries and so on – in which to socialise.

Conclusion

To this end, it is important to notice that even though some architectural and planning interventions can be applied in authoritarian and totalitarian contexts like Tehran, these public spaces cannot said to be for democratic use, because people (and especially marginalised groups, such as women, youth and LGBTQ communities), have to follow certain codes in public spaces. This is because when public space is a manifestation of top-down, forceful and discriminatory rules, the accessibility of and visibility in those spaces should also be analysed accordingly. In the case of Tehran and other Iranian cities in general, the city is under the absolute authority of the religious establishment and its apparatuses. The argument is that without taking into consideration the power relations and political contexts of cities, no set of design proposals can easily transform them into a complex place of free and dynamic social interactions among different people. This argument goes further, however, to strip from the concepts of openness and closedness the overcharged meanings they currently have in the West. By considering how women in Iranian cities face discriminatory forces that compel them to hide all their hair and body parts behind hijab and to remain segregated from men in order to be able to appear in public spaces, this paper has demonstrated a sort of alternative openness related to gender politics and women’s everyday lives, as well as the tactics and innovations they use to get access to and remain in public spaces, through resistance, subversion and embodied actions. Thus, while open city theory sets out to create informal ways to mix and interact in the city, this paper has shed light on different kinds of temporary social interactions that happen informally and even ‘unlawfully’ in Tehran, which in turn create opportunities for accessibility, interaction, visibility and complexity that also need to be considered.

Acknowledgment

I would like to show my gratitude and appreciation to the anonymous reviewers of my paper. I have learned a great deal from their insightful comments, critiques and points.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mahsa Alami Fariman

Mahsa Alami Fariman is a PhD researcher, educator and architect. Studying PhD in urban sociology at Goldsmiths College, she holds MA in architecture (Cultural Identity and Globalisation) from University of Westminster in the UK and BA in architecture from Islamic Azad University in Iran. Her research focuses on gender, power relations, architecture, urban planning and social life in the cities. She is a Fellow of the British Higher Education Academy and previously, has taught at Goldsmiths, University of London (as Associate Lecturer) and Coventry University (as Visiting Critic and Guest Lecturer). She has also worked in a number of multidisciplinary architecture and design practices in Iran.

References

- Abaza, Mona. 2014. “Post January Revolution Cairo: Urban Wars and the Reshaping of Public Space.” Theory, Culture and Society 31 (7/8): 16–183.

- Afary, Janet. 2009. Sexual Politics in Modern Iran. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Aghdasifar, Tahereh. 2020. “Rhythms of the Banal: Tracing Homosociality in Iranian Bra Shops.” Women & Performance 30 (2): 195–213. doi:10.1080/0740770X.2020.1869417.

- Amin, Ash. 2008. “Collective Culture and Urban Public Space.” City 12 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1080/13604810801933495.

- Amin, Camron Michael. 2002. The Making of the Modern Iranian Woman: Gender, State Policy, and Popular Culture, 1865–1946. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

- Amir-Ebrahimi, Masserat. 1995. “Influence of Bahman Cultural Center in the Social and Cultural Life of Women and Youth of Tehran.” Tehran, Goftogu 9: 13–23.

- Amir-Ebrahimi, Masserat. 2006 “Conquering Enclosed Public Spaces.” Cities 23 (6): 455–461. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2006.08.001.

- Amir-Ebrahimi, Masserat. 2008. “Transgression in Narration: The Lives of Iranian Women in Cyberspace.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 4 (3): 89–115. doi:10.2979/MEW.2008.4.3.89.

- Amir-Ebrahimi, Masserat. 2016. “Reflections on the Relationship between Space, Home and Family.” Ravayat 10: 184–195.

- Amir-Ebrahimi, Masserat, and Abbas Kazemi. 2019. “Typology of Tehran’s Commercial Complexes.” Quarterly Journal of the Iranian Association for Cultural Studies and Communication 15 (56): 12–43.

- Attar, Abbas. 2001. “Tehran Café.” Abbas, [Photograph] [Online] http://www.abbas.site/#the-return

- Billaud, Julie. 2009. “Visible under the Veil: Dissimulation, Performance and Agency in an Islamic Public Space.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 11 (1): 120–135.

- Brenner, Neil. 2013. “Open City or the Right to the City?” TOPOS: The International Review of Landscape Architecture and Urban Design 85: 42–45.

- Brenner, Neil, and Christian Schmid. 2015. “Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban?” City 19 (2-3): 151–182. doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1014712.

- Chehabi, Houchang E. 2001. “The Political Regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Comparative Perspective.” Government and Opposition 36 (1): 48–70. doi:10.1111/1477-7053.00053.

- Christiaanse, Kees. 2011. “Kees Christiaanse on Open Cities.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m4B1RI-6NDc

- Derickson, Kate D. 2015. “Urban Geography I: Locating Urban Theory in the ‘Urban Age’.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (5): 647–657. doi:10.1177/0309132514560961.

- Ehsani, Kaveh. 1999. “Municipal Matters: The Urbanization of Consciousness and Political Change in Tehran.” Middle East Report 29 (212): 22–27. doi:10.2307/3012909.

- Ershad, Alijani. 2022. “Iran: Wife Killer’s ‘Walk of Fame’ Highlights Horror of ‘Honour Killings’.” France 24. https://observers.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20220216-femicide-iran-honour-killing-beheading

- Featherstone, Mike. 1991. “The Body in Consumer Culture.” In The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory, edited by M. Featherstone, M. Hepworth, and B. S. Turner, 170–196. London: SAGE Publication Ltd.

- Featherstone, Mike. 2010. “Image and Affect in Consumer Culture.” Body & Society 16 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1177/1357034X09354357.

- Foucault, Michel. 1999. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Edited by Paul Rabinow. Vol. II, Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984. London: Allen Lane.

- Foucault, Michel. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics, Michel Foucault: Lectures at the College De France. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fraser, Nancy. 1990. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” Social Text 25–26 (25/26): 56–80. doi:10.2307/466240.

- Fraser, Nancy. 2005. “Mapping the Feminist Imagination: From Redistribution to Recognition to Representation.” Constellations 12 (3): 295–307. doi:10.1111/j.1351-0487.2005.00418.x.

- Harvey, David. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso Books.

- Haraway, Donna J. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs and Women. New York: Routledge.

- Kamali, Masoud. 2007. Multiple Modernities, Civil Society, and Islam: The Case of Iran and Turkey. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Karampour, Katayoun. 2018. “Municipal Funding Mechanism and Development Process a Case Study of Tehran.” PhD thes., The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL.

- Keddie, Nikki. 2007. Women in the Middle East: Past and Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Khatam, Azam. 2009. “The Islamic Republic Failed Quest for the Spotless City.” Middle East Research and Information Project 250: 44–50.

- Kwan, Mei-Po. 2002. “Introduction: Feminist Geography and GIS.” Gender, Place and Culture 9 (3): 261–262. doi:10.1080/0966369022000003860.

- Lips, Hilary M. 2003. A New Psychology of Women, Gender, Culture and Ethnicity. Illinois: Waveland Press Inc.

- Mahmood, Saba. 2001. “Feminist Theory, Embodiment, and the Docile Agent: Some Reflections on the Egyptian Islamic Revival.” Cultural Anthropology 16 (2): 202–236. doi:10.1525/can.2001.16.2.202.

- Mahmood, Saba. 2005. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Massey, Doreen. 2008. For Space. London: SAGE Publication.

- McDowell, Linda. 1983. “Towards an Understanding of the Gender Division of Urban Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 1 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1068/d010059.

- McDowell, Linda. 1997. “Women/Gender/Feminisms: Doing Feminist Geography.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 21 (3): 381–400. doi:10.1080/03098269708725444.

- Mehrnews. 2005. “Prohibition of Two Occupants Sitting in Front Seat of the Car/Fine for Not Wearing Seat Belt in the City; From Tomorrow.” Mehrnews. https://www.mehrnews.com/news/249031/

- Minton, Anna. 2012. Ground Control; Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First Century City, Clays Ltd, St Ives plc. London: Penguin Books.

- Milani, Farzaneh. 1992. Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Miraftab, Faranak. 2007. “Planning and Gender as Seen from the Global South.” Journal of the American Planning Association 73 (1): 115–116.

- Mogilevich, Mariana. 2012. “Designing the Urban: Space and Politics in Lindsay’s New York.” PhD thes., Harvard University.

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh. 2005. Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rostami. Hoda. 2014. “Hidden City.” Iranian Photography. [Photograph] [Online] https://bedide.wordpress.com/2014/11/29/hoda-rostami-hidden-city/

- Schirazi, Asghar. 1992. Constitution of Iran: Politics and the State in the Islamic Republic. London: I. B. Tauris/St. Martin’s Press.

- Sendra, Pablo. 2015. “Rethinking Urban Public Space: Assemblage Thinking and the Uses of Disorder.” City 19 (6): 820–828. doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1090184.

- Sennett, Richard. 1976. The Fall of Public Man. New York: Penguin Books.

- Sennett, Richard. 2018. Building and Dwelling, Ethics for the City. London: Penguin Books.

- Shahrokni, Nazanin. 2014. “The Mothers’ Paradise: Women-Only Parks and the Dynamics of State Power in the Islamic Republic Of Iran.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 10 (3): 87–108. doi:10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.10.3.87.

- Shirazi, Reza M., and Somaiyeh. Falahat. 2019. “The Making of Tehran: The Incremental Encroachment of Modernity.” In Routledge Handbook on Middle East Cities, edited by Hami Yacobi and Mansour Nasasra. London: Routledge, 29–44.

- Susman, Warren I. 1979. “Personality’ and the Making of Twentieth Century Culture.” In New Directions in American Intellectual History, edited by J. Higham and P. K. Conkon. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 274–289.

- Tamari, Tomoko. 2006. “Reflections on the Development of Cultural Studies in Japan.” Theory Culture & Society 23 (7-8): 293–304. doi:10.1177/0263276406073231.

- Vaghefi, Iman. 2017. “The Production of Post-Revolutionary Tehran: A study of transformation of contemporary Tehran through a Lefebvrian Perspective.” PhD thes., Durham University.

- Wolf, Janet. 1985. “The Invisible Flâneuse. Women and the Literature of Modernity.” Theory, Culture & Society 2 (3): 37–46.