Abstract

This paper proposes that the dissemination of marginal archival resources can be informed by forms of socioeconomic precarity experienced by their creators and primary subjects. To account for these modes of circulation, the author proposes the notion of a precarious archive. The concept is developed with reference to the Kewpie Collection, an official though marginal archival resource containing photographs as well as recordings and transcripts of interviews with the photographs’ collector, Kewpie. The Collection depicts a group of self-described gays and girls living in District Six, a multicultural, inner-city area of apartheid Cape Town, before and during the District’s physical destruction by the Nationalist government. By the early 1980s, the girls were among the sixty thousand residents forcibly removed from the District because they were legally classified ‘Coloured’. The circulation of materials constituting the Kewpie Collection is characterised as precarious in two senses. First, the materials have been available to diverse uses incorporating a range of identificatory claims, often in terms in which Kewpie does not describe herself. Second, Kewpie’s account of the girls’ experiences of precarity has been de-emphasised and her photographs celebrated as evidence of the ability of gay lives to flourish in the lost District. The author instead reads these photographs as one example of the girls’ efforts to imagine new forms of social existence in the absence of sustaining infrastructure and thereby enable liveability.

Introduction

This paper suggests that the dissemination of an archival resource continues to be informed by the forms of precarity experienced by its creators and primary subjects: a group of racially minoritised, gender and sexually diverse people living in apartheid South Africa. In particular, the circulation of materials constituting this resource is characterised as precarious in the sense that, even as the materials have been available to diverse uses incorporating a range of identificatory claims, specific aspects of what they depict have been generally de-emphasised in favour of others. To account for these forms of circulation, I propose the notion of a precarious archive. This concept is developed with reference to the Kewpie Collection, an official though marginal archival resource containing 720 photographs, taken from the mid 1950s to the late 1980s, and recordings and transcripts of three interviews conducted in the 1990s with the photographs’ collector, Kewpie. These images and recollections offer a uniquely detailed depiction of a group of self-described gays and girls who lived in District Six, a bustling, multicultural residential area of twentieth-century Cape Town, before it was demolished by the Nationalist government.

The primary reasons explored herein for the Kewpie Collection’s availability to diverse uses and for the de-emphasis of certain of its depictions are twofold. First, the Collection is not corroborated by a wealth of what might count as reliable evidence. Although there are other relevant archival sources, which word limits prevent me from detailing here (see, e.g., Chetty [Citation1994] 2012), the Kewpie Collection is by far the most substantial publicly archived representation of the girls of District Six created by the girls themselves. The lack of self-authored archived materials featuring the girls is linked to the socioeconomic conditions that render certain populations relatively less likely to retain materials commonly understood as archivable or granted what Achille Mbembe (Citation2002) calls the ‘status’ of archive, in the sense of being incorporated into a physical archive and the ‘imaginary’ it ‘seeks to disseminate’ (20). Second, I argue, materials constituting the Collection represent their creators’ efforts to reimagine their conditions of precarity to enable what Kewpie calls ‘hav[ing] a life to live’, which I understand as analogous to what Judith Butler (Citation2004b) terms a liveable life (39). Asked how apartheid ‘affect[ed her] life’, Kewpie (Citation1998) says: ‘as a teenager … I realised that I’m human and I’ve got to have a life to live’. Using photography, I argue, Kewpie brings into visibility a world in which this life is possible.

The inclusion of uses of photography among gays and girls’ efforts to enable liveability acts as a reminder that, as Butler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b) explains, liveability is constituted not only by physical conditions – access to safe shelter and food, for example – but also by conditions of intelligibility that inform who can be recognised as able to live a worthwhile life. My argument draws on understandings of precarity developed by queer and feminist scholars concerned with liveability, including, primarily, Butler (Citation2009a), for whom precarity ‘designates that politically induced condition in which certain populations suffer from failing social and economic networks of support and become differentially exposed to injury, violence and death’ (ii). To these understandings, Kewpie contributes articulations of agency as an intersubjective phenomenon and attendant expressions of its limits and possibilities.

The precarious archive is understood to have three features, each explored in a section of this paper. First, its materials were created by and depict people who experienced precarity, further understandings of which these materials enable. Describing the Kewpie Collection as an archive of the precarious for this reason, the following section sketches interrelated notions of precariousness legible in the Collection and their resonances with more recent critical theorisations. The precarious archive’s second feature is that it represents strategies used to contest conditions of precarity thus described. As an example, I discuss two photographs whose creation aims to disrupt experiences recounted by Kewpie ( and ). The first two features thus outlined are then posited as key reasons for the precarious archive’s third feature: the materials constituting this archival resource themselves circulate precariously.

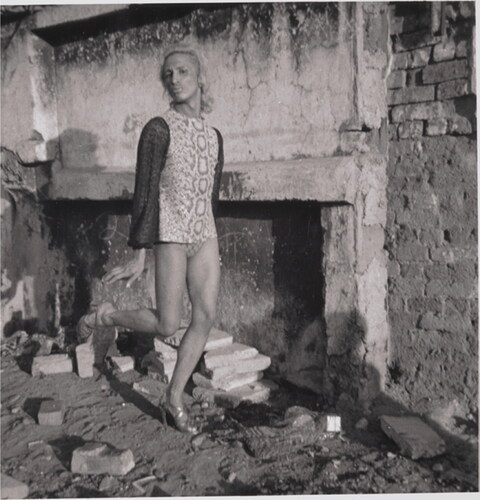

Figure 1. Kewpie. AM2886/126. The Kewpie Collection. GALA, Johannesburg. All photographs from the Kewpie Collection are reproduced with permission of the GALA Queer Archive and hereafter referenced by catalogue number only.

Butler’s (Citation2004a, Citation2004b) definition of social life as inherently precarious, with precarity differentially distributed, alludes to the use of precarious, ‘especially of a right, tenancy, etc.’, to mean ‘held or enjoyed by the favour of and at the pleasure of another person; vulnerable to the will or decision of others’. My description of the Kewpie Collection as a precarious archive is intended to capture that the outcome of actions it depicts, with which the girls seek to enable liveable lives, are especially ‘dependent on chance or circumstance; uncertain; liable to fail; exposed to risk, hazardous; insecure, unstable’ (OED Online, s.v. ‘precarious, adj.,’ June 2021).

As queer and feminist scholars show, those whose survival is imperilled by ‘the terms of social existence’ labour to transform these conditions (Hartman Citation2019, 228). This involves constructing sustaining infrastructure where it is absent and doing the necessarily collaborative labour of wedging open constraints on appearance and on what lives are therefore liveable. Various aesthetic forms this labour can take have been explored elsewhere, including in path-breaking work by Saidiya Hartman (Citation2019), madison moore (Citation2018), Martin Manalansan (Citation2015) and Tavia Nyong’o (Citation2018). Seeking to contribute to this scholarship, I posit the girls’ use of photography as one such form and suggest that, because they aim to be transformative, such aesthetic strategies can make themselves available as evidence of what they aim to create. This availability has implications for those of us who engage with archives of the precarious.

The Kewpie Collection as an archive of the precarious

Most photographs in the Kewpie Collection were taken in and near to District Six, a residential area of Cape Town, South Africa that stretched from the port to the city centre and across the lower slopes of Devil’s Peak until the mid-1980s. By this time, the majority of the District had been physically demolished by the Nationalist government and the entirety of its predominantly ‘non-White’ population subjected to the violent re-zoning through which apartheid was geographically entrenched. These photographs are currently held 1,400km North-West from the streets on which they were taken, in the Johannesburg-based GALA Queer Archive, founded in 1997 as the Gay and Lesbian Archives of South Africa and later known as Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action. They are among over 600 originals acquired in 1998 by GALA’s founder and director, the anthropologist and activist Graeme Reid, from their collector, Kewpie, who was born and raised in District Six and can be seen in .

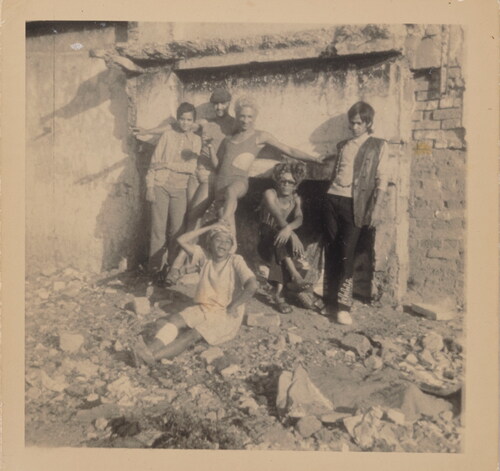

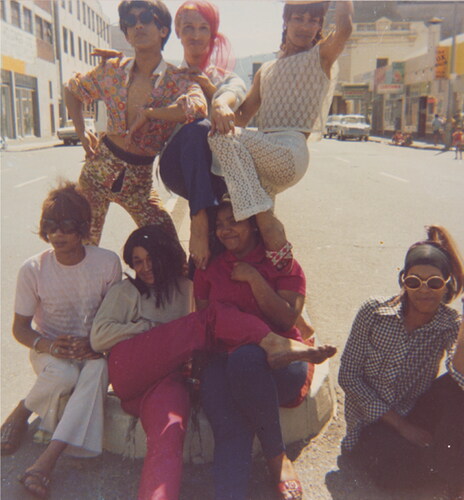

The Kewpie Collection depicts Kewpie and her friends, some of whom can be seen in and . Like Kewpie herself, many of these friends described themselves as gays and girls and using she/her pronouns after being assigned male at birth. They worked as hairdressers and onstage performers and organised fabulous parties in local nightclubs and residences (Kewpie Citation1996, Citation1998, Citation1999; Chetty [Citation1994] 2012; Corrigall and Marsden Citation2020).

Figure 3. Olivia, Kewpie and Patti, at the back, with Sue Thompson, Brigitte, Gaya and Mitzi, in the front, in Sir Lowry Road. AM2886/129.10.

District Six was home to a predominantly working-class community including artisans, laborers and merchants, immigrants and descendants of enslaved people (Jeppie and Soudien Citation1990; Rassool and Prosalendis Citation2001). Shortly after the Nationalist government began to further legally consolidate the hierarchies established at the Dutch then Cape Colony, many District Sixers, including Kewpie and her friends, were classified by the term that was given both liminal and residual functions in the 1950 Population Registration Act: Coloured. Historically, those classified ‘Coloured’ have been allocated an intermediary position in the South African race hierarchy, distinct from the socioeconomically dominant white minority and the majority of the population classified ‘African’. This position has not, however, been uniformly occupied. These manifold and often-marginalised communities’ complex histories, and those histories’ fraught relationship to the lost District, continue to be told and explored (Erasmus Citation2001; Adhikari Citation2005, Citation2013).

In 1966, the government declared District Six ‘Whites Only’ under the 1950 Group Areas Act, through which spatial apartheid was enforced from the mid to late twentieth century. This followed decades’ concerted effort to prevent any development in or upkeep of the area while fostering its reputation among the white electorate as a ‘degenerate slum’ unfit for rehabilitation (Hart Citation1988, 607). Between 1966 and 1982, approximately sixty-thousand residents were forcibly removed – as were millions across the country, many of them several times over – as the built landscape of the District was almost completely destroyed.

As well as illustrating how precarity is ‘politically induced’, District Six’s history underlines the inverse relation that exposure to ‘injury, violence and death’ has to the grievability of life (Butler Citation2009a, ii). In testimonies and memoirs, District Sixers often refer to forced removals as a sort of death. One remembers the day they were made to leave: it ‘was like a funeral … the kiefayat of District Six’ (February Citation2016, 252). Siona O’Connell (Citation2012) comments that many who have been displaced are unable to articulate, let alone overcome, the loss because the nature of the loss denied them a subject position from which to be able to mourn: the violence of apartheid ‘could only be exercised on those … not considered human’ (26; see also Baderoon Citation2004, 261).

Kewpie’s account signals the importance of ‘reintroduc[ing] difference’ into such discussions of precarity (Nyong’o Citation2013, 159). Particularly relevant is the relation of precarity to gender performativity through which certain lives are rendered illegible, therefore unliveable and therefore ungrievable (Butler Citation2009a, ii). Kewpie (Citation1996) suggests that forms of social acceptance were attainable to the extent that gays conformed to norms conferring recognition on women as subjects. However, while describing being accepted as ‘that normal woman’, Kewpie (Citation1998) suggests this is a misrecognition, most prominently defining herself as unintelligible according to prevailing social norms – stating, for example, ‘people can’t say I’m a man, they can’t say I’m a woman’ (Ramsden-Karelse Citation2022, 211). Moreover, Kewpie (Citation1996, Citation1998) implies that this form of acceptance made gays vulnerable to forms of violence – domestic violence, sexual coercion – understood as ways ‘guys’ might assert their authority over ‘headstrong’ women. Being moved into intelligibility, for gays, involved being ‘pushed about and pushed around’.

The senses of precariousness evoked in the Kewpie Collection that are linked with this unintelligibility are multiple. Kewpie attests to realities of rental precarity comparable to those discussed in present-day London, England by another author in this themed section (Taylor, forthcoming). Although Kewpie (Citation1996) recalls that she and the girls tried to establish sustaining infrastructure in the form of ‘a place to stay for [Kewpie’s] other gay friends to stay with [her]’, this ‘place’ could only exist precariously even before forced removals. Kewpie remembers arguments with the owner of the first property in which they lived; they had to move from the second because a man ‘interfered’ with one of them.

Relatedly, gays sought to carve out a ‘niche’ for themselves in which they could prove their ‘waarde’ (worth) as gatekeepers of a valued mode of feminine glamour (Chetty [Citation1994] 2012, 123; Lewis 2000). The girls’ uses of photography and naming practices to construct their own celebrity, in what I term the District Six Star System (Ramsden-Karelse Citation2020, 412–421), seem intended to insulate against the labour precarity they experienced as service and cultural workers legally barred from professional training as ‘Non-Whites’. Undertaking the sort of labour that has since become increasingly prevalent under neoliberalism, the girls’ work as often casually employed hairdressers and onstage performers anticipates a terrain of zero-hour, platform and gig employment with low or unstable income, in which labour and production are increasingly affective or immaterial (Hardt and Negri Citation2004, 108–113). This terrain induces entrepreneurial self-commodification while persistently deferring its promised rewards. There are therefore troubling limits to the transformative potential of the girls’ efforts to convert into financial capital what moore, drawing on Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1984), terms the ‘symbolic capital’ of fabulousness (moore Citation2018, 26).

Because they aim to disrupt all, these efforts indicate the interrelation of the labour precarity, rental precarity and differentially distributed social precariousness experienced by the girls. Kewpie’s account emphasises the importance to these efforts of forming collectives as protection against the exposure to ‘injury, violence and death’ to which these experiences amounted (Butler Citation2009a, ii). Kewpie (Citation1996, Citation1998, Citation1999) recounts violence as a fact of life for the girls of District Six, who were ‘bungle[d] around[,] smash[ed] … up’, ‘taken advantage’ of because they ‘[were] gay’ and ‘kidnapped around’, which Kewpie says ‘was almost like being killed around, too’.

This haunting phrase – ‘it was almost like being killed around, too’ – captures the proximity to death in which gays worked to construct liveable lives. Kewpie mentions death remarkably often in two of the three interviews in which she is featured. GALA holds a transcript of the third interview, conducted in 1998 by author and journalist Mark Gevisser, and audio recordings of the two under present consideration. First, the 1996 interview conducted by activist and filmmaker Jack Lewis, who facilitated GALA’s acquisition of Kewpie’s photographs in 1998 while directing and producing a documentary film featuring Kewpie and these photographs, released non-commercially two years later (Lewis 2000). Second, the 1999 interview conducted by Reid with Lewis intermittently offering comments and questions from the background.

In both interviews, Kewpie, who is in her mid to late fifties, sounds notably frail. Her usually slow, hoarse speech is punctuated by pauses to light cigarettes and episodes of coughing that foreshadow her death from throat cancer in 2012. Augmented by her apparent difficulty remembering detail, these vocal qualities evoke a sense of exhaustion exacerbated by frequent mentions of friends’ and acquaintances’ deaths. The cumulative effect is perhaps referenced by another scholar’s description of Kewpie as ‘maudlin’ (Chetty [Citation1994] 2012, 123). They act as markers of what research shows: biological age rapidly overtakes chronological age due to socioeconomic deprivation and for people with minoritised identities, partly as a direct result of everyday experiences of discrimination that generate meaningful psychosocial stress and thus impact on health (Williams, Lawrence and Davis Citation2019). Most often, Kewpie (Citation1999, Citation1996) mentions numerous deaths of her gay friends, many of her own generation and younger. Two were ‘discovered … dead on the field’. One was ‘killed’. Another ‘died through a car accident’. Of the hairdressers Kewpie trained herself, there were ‘eight, nine of them that died’ as well as Kewpie’s then boyfriend Brian, who worked in the salon ‘as a cashier’.

Kewpie attests to the reality of being constantly reminded that one’s life is in the hands of others: a heightened awareness that all lives ‘can be expunged at will or by accident; their persistence is in no sense guaranteed’ (Butler Citation2009b, 25). Kewpie bears witness to the toll taken by lives of precarious labour – friends ‘started out’ as ‘kid[s]’ working as ‘householder[s]’, cleaners and cooks before working on their feet all day in hairdressing salons – and to ‘the material toll that a burning queer incandescence takes’ (Muñoz Citation2009, 155). She describes gay friends living ‘fast’ or not being able to ‘rest’. Two friends died from heart attacks in the salon itself, the site at which fabulousness was produced and capitalised upon as insulation against labour precarity.

The frequency with which Kewpie (Citation1999) recounts deaths prompts Lewis to comment, ‘so this whole generation is dying out…’ Three years previously, Kewpie (Citation1996) had said to him: ‘We used to be a gang … And we were a gang … They’ve all parted… I’m still left alone. Still around’. Still, here, indicates that Kewpie remains, alone, after the others have ‘all parted’. Simultaneously, her softly spoken formulation evokes another sense of still, as in not moving, gesturing to the implication of Kewpie’s life, ‘still’, in the conditions producing the many deaths she recounts. In this way, ‘still around’ can be understood as an inversion that signifies the impossibility of moving around because of the persistence of death. I am drawing on Kewpie’s (Citation1996) recollection of sneaking out of home at night, as a teenager, to seek out spaces in which she could ‘move around’ – nightclubs and parties where she could dance, wear the ‘beautiful clothes’ she desired and ‘meet up with other gays’ – to use ‘moving around’, here, as a phrase illustrative of freedom from constraints on Kewpie’s (Citation1998) movement in and through life: freedom from being ‘pushed about and pushed around’ (Ramsden-Karelse Citation2020, 411–413). Kewpie, though alive, is left ‘still’ by the many deaths of her friends, in which she is implicated because they foretell the likelihood of her own and because they leave her alone (and therefore) still, her ability to ‘move around’ constrained by these losses, by the loss of the collective.

Kewpie bears witness to conditions of life and death for gays living within and against the constraints imposed by the entangled histories of the category ‘Coloured’. Yet her photographs remind us that there is the possibility of contesting any reality, even those violently enforced – and that this work is necessarily collective. Detailing exposure to ‘injury, violence and death’ (Butler Citation2009a, ii), describing her search for spaces in which she could ‘move around’, Kewpie conveys intimate awareness that agency is intersubjective and therefore fundamentally undermined by social inequality. Moreover, the girls use agency’s non-sovereign character to create photographs that reimagine parameters on their ability to ‘have … li[ves] to live’ (Kewpie Citation1996). The following section offers a close reading of two such photographs.

Using photography to contest precarity

Kewpie pouts from a black and white photograph, eyes locked on the lens and face tilted slightly away from the afternoon sun (). Sunlight catches her hair tumbling towards her shoulders in golden wisps, her sequinned top and the one strappy metallic heel on which she balances, her back to the graffitied and weather-beaten wall against which her long shadow is thrown. Leaning against the same wall on a different day are Kewpie and her friends () – one of whom perhaps casts the photographer’s shadow printed like a signature across the bottom right-hand corner of the first image. The five smile and shade their eyes from the sun beating down on what was once an indoor fireplace and now partly lies in the broken bricks amid which the friends gather to exude variously defiant registers of apparently effortless chic.

Striking poses amid half torn-down buildings and piles of rubble on semi-abandoned streets, with various limbs outstretched and bodies propped against the one still-standing formerly interior wall, these photographic subjects re-inhabit spaces made less private and less habitable to collaboratively perform belonging in the landscape from which they are under threat of legal removal. As Sara Ahmed (Citation2010) shows, attributing ‘good feelings’ to certain bodies means denying them to others. This is demonstrated by the material space depicted: an inner-city area being cleared out to establish the ‘correct relationship between whiteness and urbanisation’ (McEachern Citation1998, 501). As well as dictating who was merely allowed to travel for the purpose of work to urban spaces where they were granted limited rights, legal-apartheid-era forced removals dictated who was allowed to feel pleasure and experience belonging and safety, for example, within those spaces. In these photographs, however, the subjects enact dis-alignment with such policy and with the implied ‘affective geography of happiness’ (Ahmed Citation2010, 97). Through gesture, facial expression and style of dress, they convey joy in a space that they are told should not, for them, carry positive affective value: a space that should only signify joy for those for whom it is being cleared out.

The photographs’ setting recalls Lauren Berlant’s (Citation2011) reminder that precarity is ‘at root … a condition of dependency’. In a legal sense, Berlant explains, precarious ‘describes the situation wherein your tenancy on your land is in someone else’s hands’ (192). The South African government’s attempts to legally seize for 19.3% of the population classified ‘White’ all desirable land on which ‘Non-White’ individuals still lived involved the displacement of approximately three and a half million who, between 1960 and 1983, were forced further into varying degrees of socioeconomic precarity (Union of South Africa Office of Census and Statistics Citation1960; Platzky and Walker Citation1985, 9–12). Many were unable to produce the legal documentary evidence of tenancy or ownership that the Nationalist government deemed requisite for receipt of any form of compensation. This segregationist project remains alarmingly successful and this success remains visually apparent in present-day Cape Town. Enacting a symbolic reclamation of some of this seized land, however, the two photographs in question suggest an alternate geography.

The photographs articulate their subjects’ right to freedom of movement – while reminding us that a crucial aspect of freedom of movement is the freedom to stay and to enjoy staying – and they do the work of articulating that right precisely by exercising it. As Butler (Citation2009a) emphasises, turning to Hannah Arendt to consider how rights are exercised ‘even when, precisely when, those rights are nowhere guaranteed or protected by positive law’: ‘there is no freedom that is not its exercise; freedom is not a potential that waits for its exercise’ (vi). It is because freedom can only exist between people, as Arendt ([Citation1958] 1998) suggests, that agency is fundamentally undermined by social inequality. Butler (Citation2015) elsewhere paraphrases Arendt: ‘freedom does not come from me or from you; it can and does happen as a relation between us, or, indeed, among us’; together, ‘through their action’, bodies ‘bring the space of appearance into being’ (88–89).

Kewpie captures the Arendtian understanding that to be deprived of the possibility of appearance before others is to be deprived of reality because the reality of the world is guaranteed by the presence of others; its appearance to all within it. The prospect of what can appear (and thus the extent to which lives are liveable) is therefore dependent on a world created in public action. Likewise, the outcomes of action (through which individuals disclose who rather than what they are) cannot be designed nor predicted since what is disclosed is taken up and responded to – contested or consented to, for example – by others. The outcomes are, in this sense, infinite (Arendt [Citation1958] 1998, 234–235).

In my understanding, the socially-distributed character of agency is why Kewpie’s agency is constrained by conditions producing persistent, premature death as a reality for the girls: why she is left ‘still’. This is a sense of ‘still[ness]’ captured by Audre Lorde (Citation2017) when she asks ‘how many other deaths … we live through daily/pretending/we are alive’ (218; see also Bickford Citation1995, 327). In my understanding, the socially-distributed character of agency is why Kewpie searches for and creates spaces in which she can appear and act (‘move around’).

Certain of Kewpie’s photographs, such as the rubble photographs ( and ), depict one such space. They represent a mode of direct action, in the sense of members of the governed articulating their rights to what is prohibited or otherwise unavailable by claiming it in public. The girls’ continued presence on this land is criminalised, as is their style of dress: this photographic articulation of rights troubles anxieties evident in the Nationalist government’s various attempts to assert control over the performance of gender as an aspect of the development of apartheid (see, e.g., Camminga Citation2019, 41; Gevisser [Citation1994] 2012, 30; Hoad Citation2005, 17). The implication of resultant anti-‘disguise’ legislation and legislation facilitating spatial apartheid is that the girls are not allowed to experience joy in the space depicted, especially looking the way they do in the photographs. The photographs articulate their subjects’ right to ‘hav[ing] a life to live’ in a context in which their lives were being persistently curtailed (Kewpie Citation1996). The mode of direct action is therefore also political action, as theorised by Arendt (1961, [Citation1958] 1998), in a context in which apartheid aimed to foreclose the possibility, for the majority of the governed, of political participation via discussion and debate as well as voting and representation.

The photographs shown in and capture broken open homes lying in piles of brick and stone, the ‘very site of respectability’ attacked by the government (McEachern Citation1998, 515). They bring to mind Ariella Azoulay’s (Citation2015) argument that violent ruptures created by so-called house demolitions in Palestine are met with ‘efforts to reclaim public space, for however limited duration, as an open space of movement and freedom’. Azoulay suggests that ‘textures of destruction’ can come to constitute an ‘intimate and highly familiar environment’ for the targeted section of the governed, who constitute a world, in an Arendtian sense (153).

The actions depicted in the rubble photographs involve forms of interaction, such as cooperation, negotiation, concession and persuasion, that Arendt understands such spaces of appearance to be constituted by and enabling of: they break out of causal relations to bring something new into the world ( and ; Arendt 1961, 151). As Azoulay’s example indicates, however, the constitution of these spaces can be contingent and ephemeral. These photographs articulate their subjects’ right to certain freedoms – freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation as it is currently Constitutionally defined, for instance – rather than historically evidencing them. As sketched previously, Kewpie attests to the often-inhospitable environment in which these spaces were created.

Other such photographs, two of which are shown in and , depict what Kewpie (Citation1996) calls ‘the isle’ or perhaps, more befittingly of a commandeered fashion runway, ‘the aisle’. The girls repurpose as a stage this traffic island in the road that still runs through Woodstock, District Six’s neighbouring suburb. They appropriate and re-signify this in-between space by appearing, suspended mid-motion: standing, perching and reclining with legs extended and arms flung back, while onlookers at the edges of the frame signal witness to their sartorial and corporeal collaborative gesture. These photographs offer a literalised illustration of my argument that outdoor group photographs of the girls depict actualised public space, operating as ‘islands’ of freedom (Arendt [Citation1963] 2006, 618).

Photography is perhaps especially suited to facilitating the construction of such spaces. Since the kind of frame photographic representation involves can occlude social vulnerabilities or differential distributions of precarity, photography offers a means of reimagining the organisation of social relations and resultant parameters on liveability. Moreover, photography’s collaborative nature – as theorised by Azoulay (Citation2016) with Susan Meiselas and Wendy Ewald – lends itself to facilitating new shared perceptions. Like Joshua Chambers-Letson (Citation2018) argues of the ‘common sense’ that live performance can produce, non-hegemonic alliances or ‘commons’ might be enabled as photographs are created or even circulated (22; Muñoz Citation2013, 112–114). The format’s collaborative nature means that actions depicted can be understood as consented to by the various people who have allowed or enabled the photographs’ existence. The photographs imply that the girls’ right to appear in public and be recognised as both gay and worthy of protection, for instance, is consented to by a collective that is at least comprised of subjects, photographer, developer and spectators of the scenes of the photographs’ creation.

Because of photography’s ‘truth claim’ (Gunning Citation2008, 24), Kewpie’s photographs continue to conjure worlds suggested by the spaces of appearance contingently constituted in these scenes of creation. The outcomes of actions the photographs depict – the articulation of rights, for instance – therefore continue to unfold as the photographs themselves are circulated and engaged with. As noted, Arendt reminds us that the outcome of action is infinite. With regards to the Kewpie Collection, the following section suggests that these continued outcomes are informed by forms of precarity that Kewpie recounts and contests.

The Kewpie Collection as a precarious archive

While volunteering at GALA in 2017, archivist Jenny Marsden approached the District Six Museum to propose the first public exhibition of photographs from the Kewpie Collection and the first collaboration between the two institutions. Kewpie: Daughter of District Six (Citation2018) was curated by Marsden, who also acted as project manager, and the District Six Museum’s Tina Smith. After an extended run at the District Six Museum, in Cape Town, a second run – for which GALA’s Karin Tan acted as a third curator – opened at the Photo Market Workshop in Johannesburg (Kewpie Citation2019). The content, popularity and sociopolitical significance of both the exhibition’s iterations are detailed elsewhere (Smith and Marsden Citation2020). Particularly relevant to the current paper is the increase they precipitated in the Collection’s digital circulation, receiving substantial media coverage and giving rise to much increased online accessibility of certain photographs (e.g., Digital Transgender Archive Citation2018; @daughter_of_d6).

The Collection’s dissemination has since become increasingly diverse and diffuse. In early 2017, a Google search for ‘“Kewpie” “District Six”’ led to fewer than a dozen mentions; in September 2021, the same search yielded at least eighty-two relevant results, most discussing or depicting the Collection (often via the exhibition) at length. Profiles of Kewpie have appeared on popular crowd-sourced websites (SA History Citation2019; Wikipedia Citation2020). Kewpie has been introduced and her photographs shared by multiple Instagram accounts. Her images have been used to promote parties and have inspired a graduate fashion collection (Bantom Citation2021). One of Kewpie’s photographs, depicting her friend ‘the famous Miss Piper Laurie’ (Kewpie Citation1996), has graced the cover of a collection of queer poetry and essays (Windvogel and Koopman Citation2019). Kewpie has adorned T-shirts promoted on social media and sold during the Covid-19 pandemic to raise vital funds for the work of the District Six Museum. A New Frame article about ‘Queer Ancestor Kewpie’ captures the feeling shared by many, that Kewpie belongs to them in some way (Senne Citation2019). Multiple claims have been staked on Kewpie’s image and story and certain conflicts have arisen, particularly as she has been received by audiences beyond South Africa and described as ‘transgender’ and ‘white passing’, for instance (Paul Citation2021; @sexworkhistory Citation2020; Wikipedia Citation2020).

At GALA, the photographs’ frail materiality emphasises the relative ease of their creation and one sense in which materials in the Kewpie Collection exist precariously. Online, proliferating descriptions of Kewpie, often in terms in which she does not describe herself, demonstrate another sense in which these materials exist precariously. As suggested by Kewpie’s self-defined unintelligibility according to prevailing social norms, and her emphasis on the collective as opposed to the couple, the Collection does not fit easily within the set of terms currently animating popular discourses on lives that might be claimed as gay or queer. Relatedly, as the most substantial archival resource of its kind, its depictions are not corroborated by similar materials. This is perhaps a defining feature of archives of the precarious: the materials constituting these archives themselves exist and circulate precariously.

As with the Kewpie Collection’s recent dissemination, scholarship published prior to the exhibition features varying descriptions of Kewpie in terms in which she does not describe herself (see Ramsden-Karelse Citation2020, 411). This variance is linked to the girls’ unintelligibility according to social norms and risks complicity in reinscribing the precarity of non-hegemonic gender and sexual diversities (see Ramsden-Karelse Citation2022, 209–210, 213). However, scholarship published before 2018 usually mentions Kewpie in passing. The first studies with a primary focus on the Collection have been published since 2020. Two co-authored by the curators importantly depart from previous scholarship by making efforts to stay faithful to language the girls use to describe themselves (Smith and Marsden Citation2020; Corrigall and Marsden Citation2020).

Notably, the authors emphasise the ‘individual and collective agency’ seen in the girls’ use of photography to ‘def[y] and transcend … limits placed upon oppressed people during apartheid’ (Corrigall and Marsden Citation2020, 26). Ultimately, however, the Collection is presented as in the exhibition: as evidence of a ‘thriving queer community’ that was ‘highly visible’ and ‘integrated’ into the ‘broader [District Six] community’, ‘supporting historical narratives of District Six as a place where diversity and tolerance was valued’ (Smith and Marsden Citation2020, 163; Corrigall and Marsden Citation2020, 10). In spite of the varying identificatory claims staked on Kewpie, this understanding of what the materials represent continues to be established in the Collection’s public dissemination. As can be verified with the quick Google search mentioned above, what might be termed common-sense by now is that the Kewpie Collection evidences the ability of ‘gay’ or ‘queer’ lives to flourish in the District.

Such counterhistories are undoubtedly crucial. They are driven by desires, like I have suggested are legible in the Collection itself, to make life more liveable for the marginalised and oppressed. To this end, the Collection is celebrated as a blueprint for just futures (see Ramsden-Karelse Citation2020, 429, Citation2022, 209), and used in forms of advocacy that contest the experience of precarity as ‘life lived in relation to a future that cannot be propped securely upon the past’ (Ridout and Schneider Citation2012, 6). Yet the counterhistories also exemplify how the Collection’s dissemination is informed by the girls’ experiences of precarity, including their efforts to imagine otherwise.

As the Collection has been presented in film, scholarship, print and online media and museum and gallery exhibitions, Kewpie’s account of the girls’ experiences of precarity has been deemphasised in relation to its representation of freedom and flourishing. This occlusion, in the Collection’s dissemination, seems informed both by desires of the disseminators and by the girls’ uses of photography, for instance, to transform their conditions of precarity. Meanwhile, the lack of similar archival resources means the Collection is typically read in the context of the popular narrative of District Six as an inherently inclusive space, which has largely been constructed from the perspective of the District’s straight majority (Soudien Citation2001; Soudien and Meltzer Citation2001; Trotter Citation2013).

Among other things, Kewpie’s account of the proximity to death in which the girls of District Six lived and endeavoured to sustain life offers a theory of the limitations and possibilities of collective agency: a form of theory ‘constructed,’ as Pumla Dineo Gqola (Citation2001) puts it, ‘in sites which are … under white supremacist capitalist patriarchal logic, assumed to be outside the terrain of knowledge-making’ (11). This understanding of agency as a socially distributed phenomenon also represents a legacy of worldmaking, since it illuminates the girls’ use of photography, an inherently collaborative format (Azoulay Citation2016), to claim certain rights by articulating them. This produces what has been registered in the photographs as the ability of gay lives to flourish in District Six, suggesting that gays actively produced the values of diversity, freedom and acceptance that have come to be associated with the lost District.

Conclusion

This paper has offered just two examples of ways that an archival resource’s dissemination can be informed by the precarity experienced by its creators and subjects. In the case of the Kewpie Collection, proliferating descriptions of Kewpie in terms in which she does not describe herself are linked to operations through which people with ‘identities that do not fit into a single pre-established archive of evidence’ are ‘locked out of official histories and, for that matter, “material reality”’ (Muñoz Citation1996, 9). The general de-emphasis of Kewpie’s account of precarity as the Collection is circulated is due to myriad complex factors, including the scarcity within official archives of self-authored representations of the girls of District Six and the girls’ efforts to enable liveability.

The photographs are transformative. They depict actions that are consented to within a collective that Kewpie indicates could only exist precariously within District Six. Yet, because of photography’s ‘truth claim’ (Gunning Citation2008, 24), the photographs represent a world in which what these actions disclose is consented to, even though the actions were criminalised at the time and even though Kewpie indicates that the girls were targeted with violence specifically because of what the actions are seen to disclose. This world enables the appearance of what Buter (Citation2004b) calls liveable lives, or what Kewpie (Citation1996) calls ‘hav[ing]’ (not just a life but) ‘a life to live’. At the very least, this appearance is photographic. However, by exercising it, the photographs articulate the girls’ right to participate in the making of a common world in which what the photographs make legible can appear. They help wedge open conceptions of what might yet be possible, not by acting as historical evidence but by articulating certain demands.

Understandings of District Six as a place where gay or queer lives could flourish risk devaluing the work done by gays themselves, who appear in the Kewpie Collection as producers rather than beneficiaries – or products – of what have come to be understood as the District’s defining qualities, including creativity, freedom and caring inclusivity. The prominence of these understandings in the Collection’s dissemination suggests that such work – the work of transforming conditions of labour and social and political life – can make itself available as evidence of what it aims to create as opposed to the efforts necessary to do so. Transformative work can thus be understood as precarious: by making itself available as evidence of what it aims to produce, it can risk making the producing itself seem unnecessary or irrelevant. As Faith MacNeil Taylor (Citation2020) notes, ‘unvalued labour is still value producing’.

This seems to be especially the case with efforts made by those who experience precarity. Although the precarious have always done the work of imagining and living otherwise, their precarity means their work gets easily erased. There are few archived accounts such as Kewpie’s, of life for the girls of District Six, which remains crucial for understanding the set of conditions they contested and reimagined and how these might continue to repeat and be disrupted in the present. Yet these repetitions inform readings and circulations of Kewpie’s photographs as documentary evidence as opposed to politically important interventions.

These dynamics mean that the precarious archive is a site from which operations of precarity as a politically induced condition might be better understood. Since queer and feminist politics aim to enable liveable lives, it seems necessary for queer and feminist scholarship to guard against reproducing operations through which the inherent precariousness of social life is differentially distributed. As discussed in this paper, these operations include the non-recognition of non-hegemonic gender and sexual diversities and the devaluation of transformative labour.

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to the teams at GALA and the District Six Museum, who make work such as this possible, and to B Camminga for their encouragement of an early draft of this paper. I would also like to thank the anonymous readers for their engagement and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ruth Ramsden-Karelse

Ruth Ramsden-Karelse is a Fellow at the ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry. In 2022, she completed her DPhil in English at the University of Oxford.

References

- Adhikari, Mohamed. 2005. Not White Enough, Not Black Enough: Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Adhikari, Mohamed, editor. 2013. Burdened by Race: Coloured Identities in Southern Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

- Arendt, Hannah. 1951. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. London: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Arendt, Hannah. 1958. 1998. The Human Condition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Arendt, Hannah. 1963. 2006. On Revolution. New York: Penguin Books. Apple Books.

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2015. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. London: Verso.

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2016. “Photography Consists of Collaboration: Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald and Ariella Azoulay.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 31 (1): 187–201. doi:10.1215/02705346-3454496.

- Baderoon, Gabeba. 2004. “The Underside to the Picturesque: Meanings of Muslim Burials in Cape Town, South Africa.” Arab World Geographer 7 (4): 261–275.

- Bantom, Kalylynne. 2021. ‘Inspired by “Vibrant” D6’. People’s Post, 9 March 2021. https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/local/peoples-post/inspired-by-vibrant-d6-20210308

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bickford, Susan. 1995. “In the Presence of Others: Arendt and Anzaldúa on the Paradox of Public Appearance.” In Feminist Interpretations of Hannah Arendt, edited by Bonnie Honig, 313–336. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Butler, Judith. 2004a. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso.

- Butler, Judith. 2004b. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, Judith. 2009a. “Performativity, Precarity and Sexual Politics.” AIBR, Revista de Antropologia Iberoamericana 04 (03): i–xiii. doi:10.11156/aibr.040303e.

- Butler, Judith. 2009b. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? London: Verso.

- Butler, Judith. 2015. Notes toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Camminga, B. 2019. Transgender Refugees and the Imagined South Africa: Bodies over Borders and Borders over Bodies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chambers-Letson, Joshua. 2018. After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Colour Life. New York: New York University Press.

- Chetty, Dhianaraj. 1994. 2012 “A Drag at Madame Costello’s: Cape Moffie Life and the Popular Press in the 1950s and 1960s.” Defiant Desire: Gay and Lesbian Lives in South Africa, edited by Mark Gevisser and Edwin Cameron, 115–127. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- O’Connell, Siona. 2012. Tonal Landscapes: Re-Membering the Interiority of Lives of Apartheid through the Family Album of the Oppressed. University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

- Corrigall, Malcolm, and Jenny Marsden. 2020. “District Six is Really My Gay Vicinity”: the Kewpie Photographic Collection.” African Arts 53 (2): 10–27. doi:10.1162/afar_a_00525.

- Digital, Transgender Archive. 2018. ‘Kewpie Photographs’. https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/col/b5644r52v

- Erasmus, Zimitri, editor. 2001. “Coloured by History, Shaped by Place: New Perspectives on Coloured Identities in Cape Town.” Cape Town and Maroelana: Kwela Books and South African History Online.

- February, Fatima. 2016. “Fatima February.” Huis Kombuis: The Food of District Six, edited by Tina Smith, 250–255. Cape Town: Quivertree Publications.

- Gevisser, Mark. 1994. 2012 “A Different Fight for Freedom.” In Defiant Desire: Gay and Lesbian Lives in South Africa, edited by Mark Gevisser and Edwin Cameron, 14–86. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Gqola, Pumla Dineo. 2001. “Ufanele Uqavile: Blackwomen, Feminisms, and Postcoloniality in Africa.” Agenda: Empowering Women or Gender Equity 50: 11–22.

- Gunning, Tom. 2008. “What’s the Point of an Index? or, Faking Photographs.” In Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography, edited by Karen Beckman and Jean Ma, 23–40. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2004. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin.

- Hart, Deborah M. 1988. “Political Manipulation of Urban Space: The Razing of District Six, Cape Town.” Urban Geography 9 (6): 603–628. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.9.6.603.

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2019. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. London: Serpent’s Tail.

- Hoad, Neville. 2005. “Introduction.” In Sex & Politics in South Africa, edited by Neville Hoad, Karen Martin and Grame Reid, 14–27. Cape Town: Double Storey Books.

- Jeppie, Shamil and Crain Soudien, editors 1990. The Struggle for District Six: Past and Present. Cape Town: Buchu Books.

- Kewpie 1996. Interview by Jack Lewis. Achmat-Lewis Collection, AM2790, GALA. 12 January 1996

- Kewpie 1998. Interview by Mark Gevisser. Oral Histories Collection, AM2709, GALA. 4 December 1998

- Kewpie 1999. Interview by Graeme Reid and Jack Lewis. Achmat-Lewis Collection, AM2790, GALA. 4 December 1999.

- Kewpie: Daughter of District Six 2018. Exhibition curated by Tina Smith and Jenny Marsden. Cape Town: District Six Museum.

- Kewpie: Daughter of District Six 2019. Exhibition curated by Tina Smith, Jenny Marsden and Karin Tan. Johannesburg: Market Photo Workshop.

- Lorde, Audre. 2017. Your Silence Will Not Protect You. London: Silverpress.

- Manalansan, Martin. 2015. “Fabulosity: Messy Narratives of Queer Pathos and Exuberance.” Lecture, University of Columbia, New York, 21 October 2015.

- Mbembe, Achille. 2002. “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits.” In Refiguring the Archive, edited by Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, Jane Taylor, Michele Pickover, Graeme Reid and Razia Saleh, 19–26. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

- McEachern, Charmaine. 1998. “Mapping the Memories: Politics, Place and Identity in the District Six Museum, Cape Town.” Social Identities 4 (3): 499–521. doi:10.1080/13504639851744.

- moore, madison. 2018. Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 1996. “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts.” Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory 8 (2): 5–16. doi:10.1080/07407709608571228.

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2013. “Race, Sex, and the Incommensurate: Gary Fisher with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.” In Queer Futures: Reconsidering Ethics, Activism and the Political, edited by Elahe Hascheme Yekani, Eveline Kilian and Beatrice Michaelis, 103–116. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company.

- Nyong’o, Tavia. 2013. “Situating Precarity between the Body and the Commons.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 23 (2): 157–161.

- Nyong’o, Tavia. 2018. Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life. New York: New York University Press.

- Paul, Cecile. 2021. “Cape Town’s Lost District, through the Eyes of Its Transgender Darling.” Messy Nessy: Cabinet of Chic Curiosities. 27 April. https://www.messynessychic.com/2021/04/27/cape-towns-lost-district-through-the-eyes-of-its-transgender-darling/

- Platzky, Laurine, and Cherryl Walker. 1985. The Surplus People: Forced Removals in South Africa. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- Ramsden-Karelse, Ruth. 2020. “Moving and Moved: Reading Kewpie’s District Six.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 26 (3): 405–438. doi:10.1215/10642684-8311772.

- Ramsden-Karelse, Ruth. 2022. “People Can’t Say I’m a Man, They Can’t Say I’m a Woman”: Reality Expansion in the Kewpie Collection.” Routledge Handbook of Queer Rhetoric, edited by Jacqueline Rhodes and Jonathan Alexander, 207–214. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Rassool, Ciraj and Sandra Prosalendis, editors. 2001. Recalling Community in Cape Town: Creating and Curating the District Six Museum. Cape Town: District Six Museum.

- Ridout, Nicholas, and Rebecca Schneider. 2012. “Precarity and Performance: An Introduction.” TDR/the Drama Review 56 (4): 5–9. doi:10.1162/DRAM_a_00210.

- SA History 2019. “Kewpie”. 2 September 2019. Last updated 3 November 2020. https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/kewpie

- Senne, Tshegofatso. ‘Bringing you Kewpie for your #tbt…’ Instagram 2019. ‘Queer Ancestor Kewpie Created Her Own Freedom’. New Frame, 4 June 2019. https://www.newframe.com/queer-ancestor-kewpie-created-her-own-freedom/

- @sexworkhistory 2020. ‘Bringing you Kewpie for your #tbt…’ Instagram, 15 October https://www.instagram.com/p/CGX-WR6pIzH/

- Smith, Tina and Jenny Marsden. 2020. “Photographs and Memory Making: Curating Kewpie: Daughter of District Six.” In Women and Photography in Africa: Creative Practices and Feminist Challenges, edited by Darren Newbury, Lorena Rizzo, and Kylie Thomas, 163–189. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Soudien, Crain. 2001. “District Six and Its Uses in the Discussion about Non-Racialism.” In Coloured by History, Shaped by Place: New Perspectives on Coloured Identities in Cape Town, edited by Zimitri Erasmus, 114–130. Cape Town and Maroelana: Kwela Books and South African History Online.

- Soudien, Crain and Lalou Meltzer. 2001. “District Six: Representation and Struggle.” In Recalling Community in Cape Town: Creating and Curating the District Six Museum, edited by Ciraj Rassool and Sandra Prosalendis, 66–73. Cape Town: District Six Museum Foundation.

- Taylor, Faith MacNeil. 2020. “Queer Social Reproduction and the Precarious City: Rent, Capital and Share-Ability.” Paper presented at The Queer Precarities Workshop, Oxford, May 15.

- Taylor, Faith MacNeil. Forthcoming. “Queer Social Reproduction in the Precarious City: Replenishing LGBTQ Households in London.” Gender, Place & Culture.

- Trotter, Henry. 2013. “Trauma and Memory: The Impact of Apartheid-Era Forced Removals on Coloured Identity on Cape Town.” In Burdened by Race: Coloured Identities in Southern Africa, edited by Mohamed Adhikari, 49–78. Cape Town: UCT Press.

- Union of South Africa Office of Census and Statistics 1960. “South African Census 1960 Version 1.” 1. Distributed by DataFirst, Cape Town. 2012. doi:10.25828/vpag-je19.

- Windvogel, Kim and Kelly-Eve Koopman, compilers. 2019. They Called Me Queer. Cape Town: Kwela Books.

- Wikipedia 2020. “Kewpie (drag artist)”. Last modified 9 August 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kewpie_(drag_artist)

- Williams, David R., Jourdyn A. Lawrence and Brigette A. Davis. 2019. “Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research.” Annual Review of Public Health 40: 105–125. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750.