Abstract

In this paper I present my methodological approach to researching the sex practices of trans people developed during my PhD project How we Fuck. Using my body as both a fertile site of knowledge production (Bain and Nash, Citation2006), and an instrument for intimate analysis, I articulate an approach to ‘intimacy-as-method’ within an assemblage framework (Deleuze and Guattari, Citation1987) to provide new ways of engaging in empirical sex research. Intimacy-as-method draws attention to how senses, bodies, affects, human and more-than-human agents (‘things’) coalesce to produce both trans sex, and trans sex research(ers) (Fox and Alldred, Citation2015). If ontologically unstable ‘things’ gain their stability by assembling relationally, then how can we create the conditions that liberate both trans sex from dominant narratives of suffering, and (trans) sex research from its conventions of squeamishness? I argue that considering the dynamic and mutable ways in which trans sex (and trans sex research) is produced expands the capacities and limitations of what trans bodies can ‘do’, making space for novel assemblages, new embodied knowledges, and expansive possibilities of How we Fuck.

Prelude

I keep putting off starting this paper. When I sit down to write, I’m immediately clouded by abstract thought-feelings of being judged by half-imagined authority figures. Before I even begin typing, semi-fictional anonymous critics are tearing me apart. Despite my awareness that I’ve invented this booing audience, I’m incapable of quietening them. I think: ‘maybe I can start from there?’, then immediately ‘of course that’s a stupid idea, who wants to read the insecure ramblings of the monster we call imposter?’. But it is from here I start. I start here because I want to do academia differently, and I hold intimacy as a value. I believe that connection creates the conditions necessary for knowledge sharing, and I believe that without love, we’re fucked.

So, in this prelude to what I presume will eventually become a pretty robust academic paper about my research on trans sex, I invite you (yes, you!) to come as you are. To show up with your values. To arrive. Before we go on, could we both, now, in our disparate times and places, connect in a shared intention to take really good care of ourselves and each other? In this out-of-sync dialogue, I invite us both to prioritise comfort (dare we even seek pleasure?), breathe deeply, stop and start when we want, and proceed with love.

‘Founding itself upon love, humility, and faith, dialogue becomes a horizontal relationship of which mutual trust between the dialogues is the logical consequence. It would be a contradiction in terms if dialogue—loving, humble, and full of faith—did not produce this climate of mutual trust, which leads the dialoguers into ever closer partnership in the naming of the world.’

Friere 1972, 89

Introducing intimacy-as-method and the research-assemblage

The methods-driven doctoral training I received in the neo-liberal and erotophobic university (Bell Citation2007) was a lesson in detachment. What I valued most in my work with trans folks prior to entering the academy held no value here; not only was there an expectation of emotional and bodily detachment during the research itself, but also a kind of meta-detachment which separated ‘the research’ from the body that produced it and the context it got produced in.

Intimacy-as-method is an approach that refuses detachment; I have refused the position of cold, sterile observer during research encounters, instead prioritising connection and intimacy; and I have refused the position of disembodied, undesiring academic as I report on that research (De Craene Citation2017), instead welcoming vulnerability and connection within this paper, and beyond. The skills and embodied knowledges I learnt from a decade spent as a sex worker, porn performer, and sexual somatic facilitator with queer and trans folks are as integral to this method as my doctoral training. I follow Stryker (Citation2008) in claiming this as a ‘pornosophical’ approach to research which insists on ‘an epistemic parity between the disparate knowledges of the scientist, the philosopher, and the whore’. Rather than deny my experience as a trans person engaged in sex worlds, I see it as central, and ‘as a refusal to discredit what our own carnality can teach us’ (Stryker Citation2008, 39).

Intimacy is a value that weaves throughout the entire project, as: a site of inquiry; a tool for ‘data collection’ (Bain and Nash Citation2006), an embodied approach to analysis, and intimate dissemination (Moss and Donovan Citation2017). Intimacy as method refuses the separation of the research practice (the intimate encounters I held with participants, the ‘data’ that got generated, and what knowledge got produced as a consequence), and the research process (the production of trans sex research and the trans sex researcher); which is what Fox and Alldred might call a ‘research-assemblage’ (2015). Making both process and practice explicit is an ethical intervention that refuses ‘the (emotional) distance between researcher and researched’ (Di Feliciantonio Citation2021); and disrupts ‘the highly ritualised conventions of academic research’ (Fox and Alldred Citation2015, 12), where intimacy acts as a ‘line of flight’, deterritorialising research itself ‘to produce genuinely new ways of being in the world’ (Renold & Ivinson, 2014, cited in Fox and Alldred Citation2015, 12). This paper, then, becomes an assemblage of intimate encounters: between myself and the people who participated in the project; between us and our human, nonhuman and more-than-human companions; between supervisors, lovers, and thinkers; between the technologies, institutions, and global catastrophes that shape us so profoundly; between me and you, the reader.

I next contextualise this work, briefly noting trans research, sex research, and embodied methodologies. I then introduce the philosophy of New Materialism(s) - which underpins assemblage thinking - and show how it can help us think about the expansive capacities of what a trans body can ‘do’. I then detail intimacy-as-method, and consider the ethics of this approach. In the coda to this paper, I consider the ways the academy (de)legitimises certain forms of knowledge and reflect on how this happened within the current research-assemblage.

The dearth of trans sex research & the need for intimate methods

Research on the material act of sex sits at the fringes of sexuality studies - a field already marginalized by the ‘squeamish university’ (Bell 1995; Citation2007) - whilst trans research sits at the periphery of LGBT studies (Pfeffer Citation2014), a double stigma. The majority of trans sex research has focused on the ‘acceptable’ topics of sexual health/risk and whether ‘sexual function’ is preserved following medical intervention (eg. Klein and Gorzalka). Inquiry into trans intimacies tends to investigate orientations and relationships as affected by transition (eg. Hines, 2006; Brown, 2010), eschewing the materiality of sex practices.

The geographies of sexualities literature has largely focused on cis gay and lesbian spaces (March Citation2021), privileging sexual subjectivities (Johnston Citation2016). Expanding frameworks used in LGB geographical research to study trans lives obfuscates specificity and diversity by presuming a ‘universality of queer experiences’ which erases ‘trans voices within a wider LGBTQIA + nexus’ (Todd Citation2021, 6). Geographical work that does attend to trans specificities covers such topics as exclusions from queer spaces (Nash Citation2010; Browne and Lim Citation2010); the ‘gender tyranny’ of public and private space (Doan Citation2010); subjectivities in the workspace (Hines Citation2010); the navigation of gendered practices by young people (Rooke Citation2010); navigation of prison by incarcerated trans women (Rosenberg and Oswin Citation2015); trans men’s inclusion in rural communities (Abelson Citation2016); how sexed bodies are socially constructed through time and space (Longhurst and Johnston, Citation2010); and how space and place are transformed by gender variant folks, and vice versa (Johnston Citation2018).

Demonstrating attentiveness to the specificity and materiality of the lived body and answering the call for work on ‘dirty topics/messy bodies’ (Longhurst Citation2001, 25), Misgav and Johnston (Citation2014) attend to visceral geographies of the night club to think through tensions between spatial, gendered, and sexual dimensions of sweat, space, and subjectivity; whilst Brown’s (Citation2008) ethnography into cruising uses both participation and observation to investigate public homo-sex. Embodied methods that challenge representational thought and critique restrictive methodological protocols, such as ‘performative research’ (Dewsbury Citation2010), extends its ethos of disruption to every stage of research from design to dissemination, with the scholar body as an ‘instrument of research’ (Longhurst, Ho, and Johnston Citation2008). Creative, embodied, performative methods (eg. Duffy et al. Citation2011; Cain Citation2011) allow participants and researchers to engage in the activities under investigation together, in the places and spaces they occur in.

When the activity under investigation is sex, ‘ethical modes of generating data’ can present ‘a significant challenge’ (Bhairannavar Citation2021, 142) - particularly at postgraduate level - but there is precedent for sexual participation in research. Most notable is Brown’s (Citation2008) active participation and thick description of sex acts and encounters during fieldwork in cottaging sites and public toilets. Unlike Bain and Nash (Citation2006) who observed from within the queer bathhouse but did not engage as participants, Brown (Citation2008) insists on his pleasure and desire, exposing the practices and techniques of public homo-sex. These methods are sensorial, intuitive, embodied, and the resultant knowledge produced goes far beyond traditional methods. The rising call for embodied and performative methods meets the mounting demand for trans-specific research, spurred on by the push to liberate sex research from the squeamish tendencies of the university (Bell Citation2007). The culmination speaks to an urgent need for intimate research into the visceral, fleshy, fluid functions of the ‘messy materiality’ of the trans sexed body (Binnie Citation1997), and how it fucks. Intimacy-as-method - with its attentiveness to New Materialist tenets which I describe next - answers this need.

Theory

New materialism(s) and trans sex assemblages

Variously known as New Materialism (Fox and Alldred Citation2017), Material Feminism (Aranda Citation2019), or Feminist New Materialisms (Truman Citation2019), a shared feature is a relational and flat ontology which ‘draws supposedly separate realms… into one plane’ (Fox and Alldred Citation2017, 26). This flattening cuts across the impasse of essentialism and constructionism (where gender and sexuality theory flounders) by theorizing the material/natural and the discursive/social as always-already entangled, drawing together the realms of the private/micro/personal/local and public/macro/political/global (Fox and Alldred Citation2017). Things, events, or phenomena have no prior essence in this view, but are dynamic, fleeting ‘assemblages’ whereby ‘anything participating in the act of constitution can be considered part of its assemblage – including bodies, matter, environments, policies and discourses’ (Nash and Gorman-Murray Citation2017, 1524). Assemblage-thinking, with its roots in Deleuze and Guattari, is an approach that grants things their ‘ontological status and integrity only through their relationship to other similarly contingent and ephemeral bodies, things, and ideas’ (Fox and Bale, 2017, 21).

Applying assemblage thinking to sex, gender, and sexuality moves us from construction to production. Here, the ‘sexuality assemblage’ (Fox and Alldred Citation2015) produces all aspects of sexuality: it creates the conditions that give rise to desire, sexual responses, eroticism, sexual codes and customs, sexual orientations and identities, and capacities for bodies to ‘do and feel’ (ibid). Conceiving of trans sex as an ‘emergent, relationally generated phenomena’ produced by ‘socio-material relations’ in ‘culturally, politically, and historically specific contexts’ (Aranda Citation2019, 7) challenges dominant (biomedical or socially constructed) trans theorizations. It provides a ‘way in’ to show how relations such as body parts, places, sex toys, dysphoria, cisnormativity, (in)access to healthcare, racism, ableism, etc., assemble to enable or constrain trans possibilities.

This shift, Fullagar (Citation2017) notes, ‘reorients thinking around relational questions about the material-discursive forces co-implicated in what bodies can ‘do’ and how matter ‘acts’, rather than a concern with what ‘is’ a body or the agentic meaning of experience’ (2017, 247). If ‘things’ (body parts, genital configurations, sex acts, identities) become meaningful only through their connection with other human and non-human ‘things’, then we can begin to see how the form (the specific material topography or fleshy configuration) and function (what, how and who might interact with that form) of a body, or body part, or sex toy may vary greatly ‘according to the types of connections it makes with other bodies or parts of bodies (organs)’ (Holmes, O'Byrne, and Murray, Citation2010, 253). If ‘a body’s function, potential, or ‘meaning’ is entirely dependent on which other bodies or ‘machines’ it forms assemblages with’ (Malins Citation2004, 85), then we can begin to imagine ways of altering that meaning or function by tweaking various components, and their relations, within the assemblage, to see what new meanings might be created. Assemblage thinking makes visible the dynamic and mutable ways in which sex materialises, exposing what interventions, powers, and resistances might expand what a trans (researching/fucking) body can do, and how we might create the conditions for it to do these things differently.

There’s nothing ‘new’ here

Thinking this way about theory (a flat and relational onto-epistemology), method (intimacy), and gender (non-essentialised and multiplicitous) may seem novel within the academy, but these concepts are not new, nor neutral. Histories of colonialism and white supremacy underpin the very concepts of gender and sexuality (Nay and Steinbock Citation2021), as they do the western project of knowledge production, which has created and perpetuated the myth of positivism; the violent absurdity of a detached, objective and rational method; and an ahistorical, essential and naturalised binary sex-gender system. Trans as a category is rooted in racist histories of sexology (Gill-Peterson Citation2018; Snorton Citation2017), with the invention of medical transsexuality centering whiteness and interfering ‘with the intelligibility and material viability of black, brown, indigenous, and other trans of color and nonbinary lives’ (Gill-Peterson Citation2018, 615). Trans people have existed across all cultures and at all times in human history (Heyam Citation2022); Whilst not wishing to romanticise or homogenous indigenous concepts of gender, Houria Bouteldja (Citation2016) states that we cannot ignore that ‘before the great colonial night, there was an extreme diversity’ of gender and sex relations that were ‘not necessarily hetero-sexist’ (93).

Regarding so-called ‘new’ materialism; seeing phenomena as relational and matter as vital and agentic is not a new way of thinking, but one rooted in indigenous thought (Todd Citation2016). The appropriation of indigenous philosophy by new materialist scholars who present these concepts as though they are the latest ‘turn’ in academia perpetuates ‘pervasive racism and eurocentrism within the academy’ (Rosiek, Snyder, and Pratt Citation2020, 332). Similarly, regarding intimacy as a method has long been pivotal within Black feminist thought: understanding love, as bell hooks reminds us, as a verb - an action which automatically ‘assumes accountability and responsibility’ (Hooks Citation2000, 13, 2003); and recognising the power of the erotic (Lorde Citation1984), interdependency, and ‘real connection’ (Lorde Citation1984, 111) as essential to sharing knowledge.

Thinking relationally and centering intimacy is not a novel, contemporary, innovative, or hip ‘research methodology’, but a return to what we are always-already: relational beings that come into existence only in our connection with other humans, non-humans, and more-than-humans. Working in this way is simply a refusal to adopt ‘traditional taken-for-granted knowledge-making practices rooted in hierarchical mindsets’ (Kayumova, Zhang, and Scantlebury Citation2018, 257) that reify binaries, sever us from connection, and perpetuate the very systems we wish to dismantle. It is not the addition of something – intimacy is not an inert tool you can pick up and ‘use’ in research – rather it is a desire to rid ourselves of the false beliefs inherited from an academic culture that tells us love has no place here. It is an orientation that seeks to ‘extract all of our bodies from the coloniality of gender, untether ourselves from the racializing biopolitical assemblages that fasten on the flesh of us all in different ways, and heal from the wounded attachments to identity categories through which we live but that can thwart our collective work’ (Stryker Citation2020, 366).

Method

Interval

I knew it wasn’t really ‘interview’ but that was the name of the thing that most closely resembled what I was already doing on the daily: talking about sex. And so, however reluctantly, it was the word I used on the form.

After reading my first transcript, my supervisor seemed surprised, maybe amused, possibly incredulous? She said she’d never read an interview transcript where the researcher and participant meditated together before. She told me I said things she would never say in an interview. ‘Like what?’ I asked. Laughing, she told me how in response to someone detailing the kinky sex he’d had, I respond ‘Unghhh! That’s so hot!’

I explained why. It was true, for one – I felt it in my twitching cunt. I refused to excise my authentic, embodied reaction, and I trusted that they could feel my congruence. By doing this, we created the conditions, the container, for everything that followed.

There are other idiosyncrasies that never make it onto the tape-recording; things I do that don’t get captured by the term ‘interview’, but that are, never-the-less, important. Things like how I bring food to share, with great intention. That if I’m well enough, I bake beforehand. I pay attention to the smell of the room, the temperature. When someone is telling me something that gives me an affective response, I breathe deep into where I feel it in my body, I imagine myself with roots deep into the ground, with branches strong and wide, like I could weather anything. I do this instinctively. It’s a skill I learnt as a whore. It’s simply holding space. I know that this ineffable quality is felt by both parties.

So much of what happens between us is unspoken. So much gets left off the transcripts. How do I explain the way I feel in my belly the pull to ask the next question? The way I can feel when to leave a long pause and when to just breathe? The way the energy in the room changes like static before a storm when one of us is recalling something painful, or ecstatic? I know we are capable of reading these changes – its’ not magic, quite the opposite, it’s mundane, human, animal – and we can respond in a way that fosters deep connection and understanding.

Is it possible to explain in an academic context that my method is connection? My method is intimacy? I don’t know. But I have to try.

Intimacy as method

Intimacy as method is a ‘research assemblage’ (Fox and Alldred Citation2015) comprising two ways of generating ‘data’: Intimate encounters with others, and intimate encounters with self. Another way of thinking about intimacy as method is to think of the research at two different scales: The first scale is the zoomed-in scale and covers the practices of research. The focus is the research question (how do trans people fuck) and includes all the things one would normally find in social science inquiry – literature review, the research design, methods for data collection and analysis, and so forth. I centered intimacy during the research practice. I held one-to-one meetings between me and six participants. These encounters were designed to be intimate, warm, and safe, centering around connection, creativity and consent. The sessions included intimate in-depth conversation alongside artistic and embodied activities such as meditating together, sharing objects and items pertinent to our sex lives, and using arts and craft materials. The data that got produced included audio-recorded transcripts and photos of creative outputs and bought objects.

The second scale expands its view, zooming-out to include the process of research, such as: how university ethics procedures enable and constrain research possibilities; how fears around reputational damage constrain what can be published; how memories shape what we do in the present; how things like climate crisis, transphobia, the pandemic, all seep in and assemble with the research, opening up and closing down what this research can be, what it can do. This ‘more radical approach’ shifts the purpose of a journal article or thesis ‘from a supposedly ‘neutral’ presentation of outputs of a research study to an audience, to a critical and reflexive assessment of research study micropolitics’ (Fox and Allred, 2017, 173). In Deleuzian terms this concern in process is not so much an attempt at progression or revelation, or even ‘an attempt to create a whole or unity’ (Augustine Citation2010, 16) but a ‘becoming’. The research assemblage is ‘a coalescing of different forces at work… [that] converge and mingle through a variety of forms that I recognize as present relationships to memories, places, smells, colors, sounds, expectations, institutions, and possibilities’ (Augustine Citation2010, 27).

A process-ontology, or research assemblage, simply exposes ‘the constant movement and interrelationships among all material things… [and] illustrates the on-going change, movement, and creation that is always becoming in the world’ (ibid, 16). In Baradian terms, this is a ‘cut’ (Barad Citation2007), which refers to ‘processes of inclusion and exclusion in the research process: they are boundary-drawing processes that come to matter through what they reveal or conceal’ (Lahti and Kolehmainen Citation2020, 615). I make an ethical, political, and methodological choice to make a cut that incorporates the intimate knowledge of research-as-process in the becoming of the trans sex research, and the trans sex researcher becoming.

To do this, I use creative writing and drawing to ‘problematize the highly ritualized conventions of academic research writing and publishing that transform multi-register event-assemblages into the unidimensional medium of written text’ (Fox and Allred, 2017, 173). By making the ‘cut’ beyond the ethical, spatial and temporal constraints of more traditional methods of ‘data generation’, I draw in: my trans sex experiences which emerge in the intimate encounters with others (where I refuse to ‘cut’ my own experiences out, instead insisting on ‘self-disclosure’ to participants); my embodied and sensorial responses and reactions (such as crying, naming when I have goosebumps, etc); my personal accounts and reflections of the process of becoming a doctoral researcher (self-disclosure to the academy and readers of this work such as in the prelude, interval and coda in this paper); my history and background by including diary entries, medical notes, and the skills I learnt from sex work and sex workers; the wider political context that this research took place in (including a global pandemic, threat of nuclear war, a cost of living crisis); and creative outputs produced during intimate and embodied analysis where I ‘try out’ tools and practices of trans sex (an example of which was included in a previous version of this paper, the revision of which I discuss in the coda). In this way, intimacy as method turns an inquisitive eye towards what enables and constrains trans folks and our fucking, whilst simultaneously zooming-out to observe and expose the often-invisible apparatus that shape research and enable and constrain what knowledge can be produced (for a visual representation please see ).

Figure 1. Intimacy as method and the research-assemblage.

A central figure stands midway along a path facing the vanishing point, a PhD thesis. Between the figure and the thesis are depictions of an ethics lecture, the university code of practice, a meeting with supervisors, the intimate encounters inside the cabin, transcripts, analysis software, books on trans studies and new materialism, patient notes from the gender identity clinic, sex toys and prosthetics, and symbols and diagrams from the thesis. The figure has a walking stick, emotional support dog, sunflower lanyard, and their backpack has a trans flag, sex worker rights symbol, and anarchy patch. In the foreground, behind the figure, planet earth is on fire, a huge corona virus molecule partially obscures someone reading a newspaper with transphobic headlines, the UK and EU flags are torn, the university building and symbol looms, and the government paper for the consultation to reform the Gender Recognition Act lays open.

The intimate encounters with others

Being based in Brighton, the UK ‘Trans Capital’ (Smith Citation2022), I was able to publicize the project by flyering haunts like my local trans barbers and queer pub. I posted videos of myself talking about the work so that prospective participants could get a ‘feel’ for my approach. I spoke with interested folks to further share information with each other, manage expectations, and build trust.

I invited people who’d expressed interest in the project for one-to-one intimate encounters in a log cabin, nestled in the South Downs of East Sussex. Each initial encounter lasted on average two hours, with the option for two follow-ups. I met with six people between 2017–2019, holding a total of 11 intimate encounters. Participants were invited to bring anything that made them feel comfortable in the space, and anything that might assist them in sharing their sex stories such as photos or personal ephemera, sex toys, safer sex supplies, prosthetics, or outfits.

The space was an important part of the assemblage. It included different options for sitting or lying, with beanbags, mattresses, armchairs, floor mats and cushions; there was a log fire which, on most occasions, we tended; one half of the cabin was filled with art supplies and huge floor canvases where we could use paint, clay, pens, and plasticine with wanton abandon to mess; the snack table at the far end had tea and coffee, plus food I’d baked for the occasion (see ). On two occasions, when access needs precluded use of the cabin, the intimate encounters took place elsewhere; one in my living room, and another on Zoom. In the latter, we discussed beforehand how to connect meaningfully across spatial distance and decided to share the same food and drink and to call from our respective beds, intentionally inviting intimacy.

The ethical values/‘ethical’ constraints of the intimate encounters

In my earliest dreams of the project, I had envisaged research that resembled the workshops and events I’d been involved with in the years prior to study. However, a rejection of my initial ethics application - and what I later came to reflect on as a public shaming during doctoral training on research ethics - resulted in a research design that foreclosed anything considered ‘too sexual’, such as attending trans sex events as field work, or conducting research alongside trans sex workshops. Instead, I held one-to-one encounters with other trans people to talk about sex. It was my intention for these meetings to be as far removed as possible from the clinical interview (which many trans folks are all too familiar with) by intentionally fostering warmth and intimacy, and championing the values of creativity, connection, and consent. I eventually achieved ethical approval for the project after making it explicit that I was not using intimacy as a euphemism for sex, and that everyone would keep their clothes on and their hands to themselves. After such a thorough ethical process to get the project approved, it seemed strange to me that the process expected of me for gaining participant’s consent was a one-off signed information sheet.

Feminist and queer sexuality researchers have questioned the efficacy of standard ethics procedures which deploy strategies that are ‘normalised through liberal notions of ‘consent’’ (Detamore Citation2010, 169), (eg. Di Feliciantonio Citation2021; Brooks Citation2019; Detamore Citation2010). A signed consent sheet frames consent as a one-off piece of bureaucracy mediated by a disembodied document, which fails to capture the complex ‘ethical or moral base of the relationship between researcher and researched [which] cannot be adequately captured by the language of contractual consent or care’ (Pérez-Y-Pérez and Stanley Citation2011, 4.3). Critically engaging with the formal practices of ethical committees by shifting the focus to practices which ‘best serve the interests of the communities and individual involved in or impacted by the research’ (165) produces a more ‘trans ethical research’ (Humphrey, Fox, and Easpaig Citation2019). Brooks (Citation2019) describes how we can ‘feel’ into what is ethical with our bodies which ‘have the power to enter encounters and determine together the ethics (what is right and what is wrong for them in that encounter)’ (2019, 28, italics in original). Together, my participants and I designed and implemented ethical practices which we judged were appropriate and meaningful.

Instead of using the kinds of ethical principles that govern biomedical research, Barker (Citation2018) and Brooks (Citation2019) look to the ethical principles that we apply to sex to inform our sex research. The academy is uncomfortable drawing parallels between sex and research because it assumes this makes research less safe (De Craene Citation2017), but what if the opposite is true? What if the values and protocols that underpin ethical sex could teach us how to be more ethical researchers? Continually centering creativity, connection and consent created the conditions for intimate encounters with an ethics of care as their cornerstone. It is to these practices I now turn.

Creativity: We made use of art materials to help us share with each other the ineffable, embodied, experience of sex. Making art together is a connecting, vulnerable, and playful experience. We made maps of our genitals, comic-strips depicting BDSM scenes, clay models of how masturbation feels, and photographs of our bodies - to name a few. Creative methods helped disrupt the repetition of dominant narratives of suffering that surface when purely discursive methods are used; allowed for complex, incoherent, or contradictory experiences; and conveyed something of the immediacy and sensuousness of sexual experience (Barker, Richards, and Bowes-Catton Citation2012).

Connection: rather than attempt any kind of cool, detached, observer type role, my intention was to show up to the intimate encounters available for loving, authentic, ethical connection. This ‘haptic human connection’, ‘closeness’ and shared vulnerability (Rooke Citation2010, 31) helped to create a safe-enough container for us to be able to talk freely about sex, sexuality, gender, desire, sexual practice, and bodily experience. In responding to De Craene (Citation2017) call to resist the homophobic and erotophobic ‘squeamishness’ of academia (451), I allowed desire, the erotic, and arousal to be both noticed and named (De Craene Citation2017), as well as tears, fears, joys and giggles. Detamore (Citation2010) suggests deploying the emerging intimacies of the researcher/researched entanglements as a method itself for producing intimate knowledges, where the mutual desires and investments between parties enact a ‘politics of intimacy’ (168). This was evident in the encounters as each party transparently disclosed resonant intimate details and vulnerabilities, responding to each other in a helix-like motion, we encouraged each other to feel more deeply, speak more openly, and attend more closely to our senses.

Consent: at the very heart of the intimate encounters was ongoing, informed, and embodied consent, and it was this consent practice that created the conditions for connection and creativity to flow. I adopted Barker’s (Citation2018) principles of consent in the intimate encounters: Firstly, having an ethos of self-consent for both researcher and participant where we each ‘tune into what excites and engages us rather than doing things in certain ways because we feel we should, forcing our bodies and ourselves into non-consensual practices’; an intention to seek ongoing consent as ‘an ethics of care’ by continually checking in with each other throughout the process; and in order to achieve these aims, an invitation to be ‘present to ourselves and each other’ as opposed to being focused on a particular outcome or activity (Barker Citation2018, xiv). To achieve these aims, I started each intimate encounter with an invitation into an ‘embodied consent meditation’ (see ) which I developed from my trainings with sex educators like Dossie Easton and Janet Hardy (Citation2005), and Barbara Carellas (Citation2007). The exercise rests on the notion that we each have interoceptive feedback that helps us know what it is we want and don’t want. If we can give ourselves and each other permission to both tune into - and value acting upon - this knowledge, we can be that bit closer to consensual practice. By attending to the relational space through connection, we shift liberal notions of individualised consent (which are all too frequently poorly disguised, disingenuous attempts to absolve responsibility should litigation take place; Detamore Citation2010) towards a relational and embodied practice for which we are collectively responsible.

Figure 3. Embodied consent meditation.

Two hand-drawn figures sit in meditative pose, responding to the question ‘does your body know the difference between a yes and as no?'. The orange figure on the left has a yellow swirl emanating from their belly. The green figure on the right has spiky pink stars erupting from their head and palms.

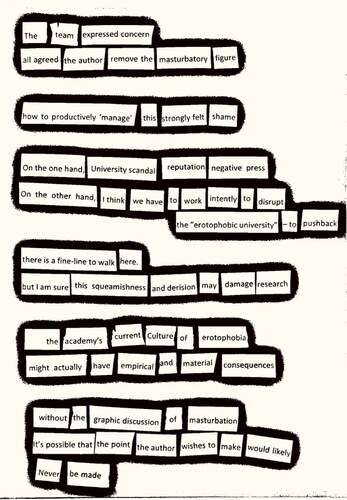

Figure 4. A found poem made by printing out and cutting up the editorial email.

Torn out words and phrases are arranged and photocopied to read ‘The team expressed concern - all agreed the author remove the masturbatory figure - how to productively manage this strongly felt shame - On the one hand, University scandal, reputation, negative press - On the other hand, I think we have to work intently to disrupt the "erotophobic university", to pushback - There is a fine-line to walk here - But I am sure this squeamishness and derision may damage research - The academy’s current Culture of erotophobia might actually have empirical and material consequences - without the graphic discussion of masturbation - It’s possible that the point the author wishes to make would likely never be made’.

Laboratories of sexual experimentation

These intimate and creative encounters in the cabin were not a space to discover some extant ‘truth’ about trans sex that resided inside me or inside the person I was with but were instead a ‘place as process’ (Stryker Citation2008). Through creativity, connection, and consent we co-created ‘a generative space, one facilitative of the materialization of creatively grasped virtualities’ (38). During the encounters we attended to ‘intensities of emotions, affective cultural practices, bodily sensation’ and the resonances between us and the ‘non-human entities and non-living things’ (Moss and Donovan Citation2017, 228). The cabin, the people in it, the art created, the sex toys and photographs shared, then become an assemblage or event that ‘knot themselves up together for a length of time’ (Stryker Citation2008, 38 citing Massey, 1993).

After the encounters, the lived space of my body became the scale of analysis; I tried any sex tip, idea, or practice that appealed or piqued my curiosity. In this way the intimate encounters became ‘laboratories of sexual experimentation’ (Stryker Citation2008, citing Foucault, 1982) which transcended the spatial and temporal constraints of the encounters themselves. Following Bain and Nash (Citation2006), I deployed my body as a tool of research. Like Brown (Citation2008) and Thomas and Williams (Citation2016), ‘disclosing’ how desire, pleasure, and embodied sex practices are experienced in and through my body is a critical reorientation that turns ‘the research gaze back upon ourselves’(94).

The deliberate centering of ‘the weighty materiality of flesh and fluid’ of my body breaks the ‘masculinist illusion’ of a boundaried, genitalless body that has for so long sanitised research and limited embodied knowledges (Longhurst Citation2001, 135). Making the body in the laboratory explicit in this way, as Longhurst (Citation1997) reminds us, profoundly reorients knowledge production towards ‘the concerns of a variety of marginalised groups’ (496). In her call to deepen research into the specific sexual and bodily differences among those oppressed by sex-gender-sexuality, Longhurst cites Grosz (1992), evoking an assemblage analytic framework which acknowledges that bodies are produced by their environment and vice versa. The space of the intimate encounters, the bodies of the participants, and my body as a site of intimate analysis assembled to produce intimate embodied knowledges, demonstrating how the psychic, social, sexual, discursive, sociocultural and environmental realms dynamically co-produce bodies with ‘certain desires and capacities’ (496, ibid).

Conclusion

Intimacy as method has the potential to expand the possibilities of what research can ‘do’ beyond this project. Centering creativity, connection and consent in our research practices is an ethical intervention with methodological utility, particularly pertinent to those conducting research with folks who have a shared marginalisation, and those inquiring into embodied, intimate, messy, sensorial subjects. But greater than the merits of intimacy as a tool of research, is the potential for intimacy as a value. What might happen if we refused the stifling norms of academia and instead imbued everything we did with intimacy? What might get produced differently if our meetings, emails, procedures, lectures, collegial relationships, university buildings, academic papers and impact assessments centered connection, creativity, and consent? Who might show up when we destabilise the research assemblage by expanding the capacities of what both research and researchers can do?

Thinking intimately with assemblages provides an entry point to how we - as collectives invested in change - can alter assemblages to make them work differently. The interventions at our disposal span the material and discursive, the micro and macro, the natural and cultural, the personal and political. As a pleasure-focused sex educator and an activist-scholar invested in collective and personal liberation, my impetus for thinking intimately with assemblages is to re-frame both sex and scholarship as something which is always unfolding and can therefore expand to meet our revolutionary aims (Feely Citation2020). This is the liberatory potential of intimate assemblage thinking, both for trans people and our capacities for pleasureful sex, and for research, research cultures, and researchers (us!) and our capacities for pleasureful research.

Coda

I open the email. The editorial team has requested I remove the empirical example of a trans sex practice. My shoulders curl inwards, towards each other. My chin retreats into my hot neck. Shame. Shame. Shame.

Have I done something wrong? Have I been naughty? Disgusting? I revisit the call. We were supposed to be pushing back against the increasing disembodiment of queer and feminist epistemologies by engaging with the material practices of sex. Even if I agree with the justification that the paper can adequately describe intimacy as method without the empirical example – which I’m not sure I do – why must it? Who is this redaction for? What are we afraid of? Are we saying that sex (as in fucking) should be off-limits in research? If not, how are we supposed to report on that research when our findings are considered too graphic, too inappropriate, too sexual?

I did what I always do when I’m reeling. I made art. I can think of few better examples of what I mean by intimacy-as-method as a research assemblage than cutting up the email that says I must remove the poem about masturbation to make a poem about being asked to remove the poem about masturbation. And so, in the absence of an empirical example of zoomed-in data about trans sex, I leave you with an empirical example of zoomed-out data about the enabling and constraining forces in the trans sex research assemblage:

Acknowledgments

Immense gratitude to all the reviewers, the feedback on this paper was both kind and extremely helpful. Special thank you to the guest editors Cesare and Valerie for some of the most nourishing conversations I’ve had in academia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

H Howitt

H Howitt is a disabled creator, activist and somatic sex educator who researches the sexual practices of trans people in the School of Applied Social Sciences at the University of Brighton. Their past work includes designing and delivering Fuck Gender: A Queer Sex Workshop in multiple European and Australian cities, supporting Kate Bornstein’s UK tour of My Gender Workshops, providing trans awareness training for general practitioners, and presenting their research at the Trans Pride conference in Brighton in 2017. They have also written for numerous publications including a trans issue of Context magazine for systemic therapists, the anthology Non-Binary Lives, and the forthcoming book Letter to My Little Queer Self. Their current PhD project uses intimacy as method, creativity, and vulnerability, through an assemblage theory framework, to make visible the diverse and complex ways trans people engage with the materiality of fucking.

References

- Abelson, Mirium. 2016. “Trans Men Engaging, Reforming, and Resisting Feminisms.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 3 (1–2): 15–21. doi:10.1215/23289252-3334139.

- Aranda, Kay. 2019. “The Political Matters: Exploring Material Feminist Theories for Understanding the Political in Health, Inequalities and Nursing.” Nursing Philosophy: An International Journal for Healthcare Professionals 20 (4): e12278. doi:10.1111/nup.12278.

- Augustine, Sharon Murphy. 2010. “Reading as Assemblage: Intensive Reading Practices of Academics.” (Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia).

- Bain, Alison L., and Catherine J. Nash. 2006. “Undressing the Researcher: feminism, Embodiment and Sexuality at a Queer Bathhouse Event.” Area 38 (1): 99–106. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2006.00663.x.

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Barker, Meg-John. 2018. Researching Sex and Sexualities. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Barker, Meg-John, Christina Richards, and Helen Bowes-Catton. 2012. “Visualizing Experience: Using Creative Research Methods with Members of Sexual and Gender Communities.” In Researching Non-Heterosexual Sexualities , edited by Phellas, Constantinos N., 57–80. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Bell, David. 2007. “Fucking Geography, Again.” In Geographies of Sexualities: Theory, Practices and Politics, edited by K. Browne, J. Lim and G. Brown, 264. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Bhairannavar, Kiran. 2021. “Ethics in Geographical Research: Studying Male Homosexual Cruising Sites.” International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences 6 (2): 202.

- Binnie, Jon. 1997. “Coming out of Geography: Towards a Queer Epistemology?” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 15 (2): 223–237. doi:10.1068/d150223.

- Bouteldja, Houria. 2016. Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Brooks, Victoria. 2019. Fucking Law: The Search for Her Sexual Ethics. London: Zero books.

- Brown, Gavin. 2008. “Ceramics, Clothing and Other Bodies: affective Geographies of Homoerotic Cruising Encounters.” Social & Cultural Geography 9 (8): 915–932. doi:10.1080/14649360802441457.

- Browne, Kath, and Jason Lim. 2010. “Trans Lives in the ‘Gay Capital of the UK.” Gender, Place & Culture 17 (5): 615–633. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2010.503118.

- Cain, Trudie M. 2011. “Bounded Bodies: The Larger Everyday Clothing Practices of Larger Women.” PhD thesis, Massey University, Albany, New Zealand.

- Carellas, Barbara. 2007. Urban Tantra. New York: Celestial Arts.

- De Craene, Valerie. 2017. “Fucking Geographers! or the Epistemological Consequences of Neglecting the Lusty Researcher’s Body.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (3): 449–464. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2017.1314944.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Detamore, Mathias. 2010. “Queer (y) Ing the Ethics of Research Methods: Toward a Politics of Intimacy in Researcher/Researched Relations.” In Queer Methods and Methodologies, edited by K. Browne, and C. Nash, 167–182. London: Ashgate.

- Dewsbury, J. D. 2010. “Performative, Non-representational, and Affect-based Research: Seven Injunctions.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Geography, edited by Dydia DeLyser, 321–334. London: Sage.

- Di Feliciantonio, Cesare. 2021. “(Un)Ethical Boundaries: Critical Reflections on What We Are (Not) Supposed to Do.” The Professional Geographer 73 (3): 496–503. doi:10.1080/00330124.2021.1883447.

- Doan, Petra. 2010. “The Tyranny of Gendered Spaces–Reflections from beyond the Gender Dichotomy.” Gender, Place & Culture 17 (5): 635–654. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2010.503121.

- Duffy, Michelle., Waitt, Gordon., Gorman-Murray, Andrew. and Gibson, Chris. (2011) ‘Bodily Rhythms: Corporeal Capacities to Engage with Festival Spaces’, Emotion, Space and Society, 4: 17–24. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(1): 664–79. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2010.03.004.

- Easton, Dossie, and Janet W. Hardy. 2005. Radical Ecstasy: S/M Journeys in Transcendence. Emeryville, California: SCB Distributors.

- Feely, Michael. 2020. “Assemblage Analysis: An Experimental New-Materialist Method for Analysing Narrative Data.” Qualitative Research 20 (2): 174–193. doi:10.1177/1468794119830641.

- Fox, Nick J., and Pam Alldred. 2015. “Inside the Research-Assemblage: New Materialism and the Micropolitics of Social Inquiry.” Sociological Research Online 20 (2): 122–140. doi:10.5153/sro.3578.

- Fox, Nick J., and C. Bale. 2018. “Bodies, Pornography and the Circumscription of Sexuality: A New Materialist Study of Young People’s Sexual Practices.” Sexualities 21 (3): 393–409. doi:10.1177/1363460717699769.

- Fox, Nick, and Pam Alldred. 2013. “The Sexuality-Assemblage: Desire, Affect, anti-Humanism.” The Sociological Review 61 (4): 769–789. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12075.

- Fox, Nick, and Pam Alldred. 2017. J. Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action. Great Britain: Sage.

- Freire, Paulo. 1972. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

- Fullagar, Sara. 2017. “Post-Qualitative Inquiry and the New Materialist Turn: Implications for Sport, Health and Physical Culture Research.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 9 (2): 247–257. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2016.1273896.

- Gill-Peterson, Jules. 2018. Histories of the Transgender Child. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press.

- Heyam, Kit. 2022. Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender. London, UK: Hachette.

- Hines, Sally. 2010. “Queerly Situated? Exploring Negotiations of Trans Queer Subjectivities at Work and within Community Spaces in the UK. Gender.” Place & Culture 17 (5): 597–613. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2010.503116.

- Holmes, David, Patrick O'Byrne, and Stuart J. Murray. 2010. “Faceless Sex: glory Holes and Sexual Assemblages.” Nursing Philosophy 11 (4): 250–259. doi:10.1111/j.1466-769X.2010.00452.x.

- Hooks, bell. 2000. All about Love: New Visions. New York City: William Morrow.

- Humphrey, Rhi., Rachel Fox, and Bróna Nic Giolla Easpaig. 2019. “Co-Producing Trans Ethical Research.” The Emergence of Trans: Cultures, Politics and Everyday Lives. Oxfordshire: Routledge. 165–178.

- Johnston, Lynda. 2016. “Gender and Sexuality I: Genderqueer Geographies?” Progress in Human Geography 40 (5): 668–678. doi:10.1177/0309132515592109.

- Johnston, Lynda. 2018. Transforming Gender, Sex, and Place: Gender Variant Geographies. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Johnston, Lynda, and Robyn Longhurst. 2010. Space, Place, and Sex: Geographies of Sexualities. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kayumova, Shakhnoza, Wenbo Zhang, and Kathryn Scantlebury. 2018. “Displacing and Disrupting Colonizing Knowledge-Making-Practices in Science Education: Power of Graphic-Textual Illustrations.” Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 18 (3): 257–270. doi:10.1007/s42330-018-0030-3.

- Klein, Carolin, and Boris B. Gorzalka. 2009. “Continuing Medical Education: Sexual Functioning in Transsexuals following Hormone Therapy and Genital Surgery: A Review (CME).” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 6 (11): 2922–2939. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01370.x.

- Lahti, Annukka, and Marjo Kolehmainen. 2020. “LGBTIQ + Break-up Assemblages: At the End of the Rainbow.” Journal of Sociology 56 (4): 608–628. doi:10.1177/1440783320964545.

- Longhurst, Robyn. 1997. (“Dis) Embodied Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 21 (4): 486–501. doi:10.1191/030913297668704177.

- Longhurst, Robyn. 2001. “Geography and Gender: looking Back, Looking Forward.” Progress in Human Geography 25 (4): 641–648. doi:10.1191/030913201682688995.

- Longhurst, Robyn, Elsie Ho, and Lynda Johnston. 2008. “Using “the Body” as an “Instrument of Research”: Kimch’i and Pavlova.” Area 40 (2): 208–217. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00805.x.

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider. Trumansburg. NY: Crossing.

- Malins, Peta. 2004. “Body–Space Assemblages and Folds: theorizing the Relationship between Injecting Drug User Bodies and Urban Space.” Continuum 18 (4): 483–495. doi:10.1080/1030431042000297617.

- March, Loren. 2021. “Queer and Trans* Geographies of Liminality: A Literature Review.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (3): 455–471. doi:10.1177/0309132520913111.

- Misgav, Chen, and Lynda Johnston. 2014. “Dirty Dancing: The (Non)Fluid Embodied Geographies of a Queer Nightclub in Tel Aviv.” Social & Cultural Geography 15 (7): 730–746. doi:10.1080/14649365.2014.916744.

- Moss, Pamela, & Donovan, Coutrney. (Eds.) 2017. Writing Intimacy into Feminist Geography. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Nash, Catherine J. 2010. “Trans Geographies, Embodiment and Experience.” Gender, Place & Culture 17 (5): 579–595. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2010.503112.

- Nash, Catherine J., and Andrew Gorman-Murray. 2017. “Sexualities, Subjectivities and Urban Spaces: A Case for Assemblage Thinking.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (11): 1521–1529. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2017.1372388.

- Nay, Yv., and Eliza Steinbock. 2021. “Critical Trans Studies in and beyond Europe.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 8 (2): 145–157. doi:10.1215/23289252-8890509.

- Pérez-Y-Pérez, Maria, and Tony Stanley. 2011. “Ethnographic Intimacy: Thinking through the Ethics of Social Research in Sex Worlds.” Sociological Research Online 16 (2): 39–48. doi:10.5153/sro.2310.

- Pfeffer, Carla A. 2014. “Making Space for Trans Sexualities.” Journal of Homosexuality 61 (5): 597–604. doi:10.1080/00918369.2014.903108.

- Rooke, Alison. 2010. Queer in the Field: On Emotions Temporality and Performativity in Ethnography (p 25–41). London: Ashgate.

- Rosenberg, Rae, and Natalie Oswin. 2015. “Trans Embodiment in Carceral Space: hypermasculinity and the US Prison Industrial Complex.” Gender, Place & Culture 22 (9): 1269–1286. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2014.969685.

- Rosiek, Jerry L., Jimmy Snyder, and Scott L. Pratt. 2020. “The New Materialisms and Indigenous Theories of Non-Human Agency: Making the Case for Respectful anti-Colonial Engagement.” Qualitative Inquiry 26 (3-4): 331–346. doi:10.1177/1077800419830135.

- Smith, Matthew C. 2022. “Mapping Planning Policy and Trans Experiences.” Paper Presented at: LGBT Housing Conference, Brighton

- Snorton, C. Riley. 2017. Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press.

- Stryker, Susan. 2008. “Dungeon Intimacies: The Poetics of Transsexual Sadomasochism.” Parallax 14 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1080/13534640701781362.

- Stryker, Susan. 2020. “Introduction: Trans* Studies Now.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 7 (3): 299–305. doi:10.1215/23289252-8552908.

- Thomas, Jeremy N., and D. J. Williams. 2016. “Getting off on Sex Research: A Methodological Commentary on the Sexual Desires of Sex Researchers.” Sexualities 19 (1-2): 83–97. doi:10.1177/1363460715583610.

- Todd, James D. 2021. “Exploring Trans People’s Lives in Britain, Trans Studies, Geography and beyond: A Review of Research Progress.” Geography Compass 15 (4): e12556. doi:10.1111/gec3.12556.

- Todd, Zoe. 2016. “An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on the Ontological Turn:‘Ontology’is Just Another Word for Colonialism.” Journal of Historical Sociology 29 (1): 4–22. doi:10.1111/johs.12124.

- Truman, Sarah E. 2019. “Feminist New Materialisms.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of Research Methods. London, UK: Sage, 11.