Abstract

This essay examines how the Ukrainian and Russian government-owned newspapers, Uriadovyi Kurier and Rossiiskaya Gazeta, represent people displaced by the war in Donbas, analysing the political goals revealed by these publications’ attitudes towards the displaced. While the Ukrainian publication delimits the nation by distinguishing ‘real’ internally displaced people (IDPs) deserving help and ‘fake’ IDPs guilty of siphoning Ukrainian taxpayers’ money to rebel-held areas, the Russian paper foregrounds the Russian state's competence in managing displacement while silencing the displaced themselves.

‘A whole scheme of fraudsters posing as internally displaced people and receiving millions of hryvnias from the state budget has been revealed’, claimed Arsenii Yatseniuk in February 2016, at that time the prime minister of Ukraine, justifying the halting of the payment of social benefits to 150,000 people.Footnote1 In the same month, in a meeting held in Minsk, the secretary of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Nikolai Bordyuzha, stated:

the 1.5 million refugees from Ukraine in Russia, and the thousands of refugees from Ukraine in Belarus, are employed, do not organise demonstrations, do not ask for social guarantees or excessive attention to themselves … . This is the result of the work of the authorities, who have done everything possible to prevent tensions. (Bogdanov Citation2016)

These two quotes illustrate how migration emerges as an issue through which other political dilemmas are discussed in the public sphere. In these discourses, migrants are often used as pawns of various political forces in the process of negotiating, among other things, the future of the welfare state and the relationship between the state and the nation. Despite being nearly invisible in the Western press, the displacement caused by the war in Donbas (portmanteau for ‘Donetsk basin’) region of Ukraine is hardly an exception to this pattern. To date, the military conflict between Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed rebels has prompted millions of people to flee to other regions of Ukraine or abroad. The war has thus created a type of person with whom Ukraine had only had fleeting experience prior to 2014: the internally displaced person (IDP). The Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986 forced some 350,000 people from their homes; the scale of displacement following the armed clashes in Donbas is wholly different: by April 2018, there were about 1.8 million IDPs in Ukraine (Petryna Citation2013, p. 124; UNHCR Citation2018a). The challenges of managing such a large-scale displacement are a test for an impoverished state, especially one experiencing conditions of war and institutional change following the Euromaidan revolution. In addition to the strain on resources, I argue that managing and discussing the displacement has played an important role in Ukraine's nation-building project after the Euromaidan and the war in Donbas. A host of exclusionary discourses and practices towards IDPs, exemplified by Yatsenyuk's quote above, have contributed to the formulation of a more unitary conception of the nation in Ukraine at the expense of the IDPs as an ‘other’.

The conflict has also caused external displacement to neighbouring countries and some movement towards European Union countries. The majority of those fleeing abroad from Donbas went to Russia, with Belarus and Poland being the next most popular destinations. In late 2017, there were about 400,000 Ukrainian asylum seekers in Russia, but the total figure of forcibly displaced former Donbas residents there may be higher, as most have not claimed refugee status or asylum but prefer to pursue other forms of legal residence, or stay in Russia undocumented (UNHCR Citation2017). The large number of labour migrants from Ukraine already in the country at the start of the conflict also makes estimating exact numbers of Ukrainian refugees or asylum seekers in Russia difficult. In April 2016, UNHCR had counted over a million Ukrainian citizens seeking asylum or other status in Russia (UNHCR Citation2016). In the early phases of the conflict, in the summer of 2014, hundreds of thousands of people arrived in the border oblasti (regions) of Belgorod, Voronezh, Rostov and Krasnodar krai. While some have since returned to Donbas or received Russian citizenship, Ukrainian citizens are still the largest group of asylum seekers in Russia (UNHCR Citation2018b).Footnote2 However, as both the Ukrainian and Russian governments have an interest in exaggerating the numbers of displaced people, the figures quoted above should not be taken unproblematically (Düvell & Lapshyna Citation2015, p. 7).

This situation opens up the interesting possibility of observing the processing of acute political concerns in the public discourse in both countries. Research regarding forced migration has shown that displacement in general is intimately connected to nation-building processes and questions of ‘stateness’ (Soguk Citation1999; Turton Citation2002; Mylonas Citation2012). As will be argued below, displacement, far from being simply a technical problem, poses deeper challenges for the state: it draws attention to the state's inability to control its territory and protect its citizens. At the same time, the management of displacement may offer opportunities for ethnonationalist entrepreneurs, especially in states with an ambiguous or complex ethnic and regional composition. This case of displacement is especially interesting, as post-Soviet nation-building processes have been problematic in both Ukraine and Russia. For most of its period of independence, Ukraine has struggled to find a commonly accepted conception of the nation, with a population deeply divided on issues such as the country's geopolitical orientation, constitutional character (a unitary state or a form of regional autonomy) and state language laws (Wilson Citation2014). Political actors have exploited these divisions for electoral gains but have proven unwilling to tackle these questions decisively once in office, thereby deliberately avoiding the potential for conflict. While the conception of the nation in Russia has been somewhat clearer for political elites, the Russian authorities have nevertheless been unable to formulate a coherent policy determining where exactly the nation's borders lie (Shevel Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Laruelle Citation2015; Laine Citation2017). Despite popular and populist pressures for a more ethnically bounded conception of the nation in Russia, the political necessity of maintaining ties to Russian-speaking ‘compatriots’ abroad, as well as a commitment to a multi-ethnic citizenry and federalism, make defining the nation in more exclusivist terms difficult. The Euromaidan events and the war in Donbas have polarised public discussion in both countries and, especially in the case of Ukraine, have contributed to the emergence of a clearer vision of the nation, both among the political elites and the population (Uehling Citation2017).

In this essay, I investigate how the Ukrainian and Russian governments relate to displaced people from Donbas and analyse what these attitudes might reveal through a reading of selected articles from the government-owned newspapers Uriadovyi Kurier (published in Ukraine) and Rossiiskaya Gazeta (published in Russia). My analysis of these publications shows that the theme of displacement is used to address different but interconnected political themes in the two countries. In Ukraine, I argue, the figure of the IDP is used to delimit Ukrainian national unity by excluding ‘fake IDPs’ residing in the non-government-controlled areas (NGCAs) by associating them with Russian occupiers, separatists and corrupt officials. Additionally, managing displacement is presented as an opportunity for Ukraine to engage foreign partners, especially EU countries. Meanwhile, the Russian publication uses the topic of displacement mainly to advance claims about Russia's superior state capacity to manage such a large-scale societal event successfully, in implicit or explicit comparison with Ukraine and EU countries. The displaced people themselves remain largely silent in Rossiiskaya Gazeta's reporting, where the executive appears as the main actor in solving the issues of regional authorities and displaced people alike. While displaced people are directly interviewed in Uriadovyi Kurier, their voice is often presented in a way that lends support to the government's actions. In the following sections, I will briefly present the context of the displacement from Donbas and discuss the observations of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working with the forcibly displaced. I will then move on to discuss the connection between displacement and nation-building, present my data and methods and, finally, describe the findings of my analysis in more detail. I argue that the Ukrainian publication instrumentalises displacement to address concerns with nation-building, whereas Rossiiskaya Gazeta mainly discusses state capacity, even though, judging by the public discourses in both countries, the situation could just as well be reversed.

Political and societal reactions to Donbas displacement

It is important to consider the wider context of discussions around displacement in Ukraine and Russia in order to evaluate reporting on the topic in governmental newspapers. The sudden migration has brought about societal reactions, both positive and negative, as well as specific policy responses in Ukraine and Russia. In particular, Ukraine's shortcomings in dealing with the displacement attracted some scholarly attention. For example, despite being citizens of Ukraine and thus entitled to all the same social support and benefits as before their displacement, IDPs in Ukraine have been forced to take extra steps to access welfare. IDP registration was introduced as a necessary precondition for receiving targeted support in October 2014 (Mamutov et al. Citation2015, p. 9). A government decision harshly criticised by NGOs in 2014 was the introduction of resolutions 505 and 637, which stipulate that the payment of any kind of state benefits, including pensions, be conditional on registration and residence in government-controlled areas (Mamutov et al. Citation2015, p. 12). The implementation of these resolutions has forced some pensioners and other benefit recipients, unable or unwilling to relocate permanently to such areas, to travel back and forth across the contact line to receive their benefits, sometimes using the services of semi-legal middlemen to acquire registration documents in government-controlled areas. According to both Ukraine's own pension legislation and international agreements signed by Ukraine, claiming benefits should not be dependent on place of residence.Footnote3 Ironically, these resolutions became the necessary preconditions to the widely circulated accusations of benefit fraud, as some IDPs living in NGCAs began travelling to GCAs to collect benefits, which the new resolutions disqualified them from receiving, as residents of occupied territories. It also caused a wave of internal displacement from the rebel-held areas, as elderly people in particular were forced to leave their homes in order to receive their pensions (Woroniecka-Krzyzanowska & Palaguta Citation2017, p. 7). These developments created the conditions for the discourse concerning ‘fake IDPs’, discussed below.

Meanwhile, several legal projects have been initiated in Russia for facilitating registration and granting of residence permits to citizens of Ukraine. Significantly, only 688 Ukrainian citizens were granted refugee status between 2014 and 2016 (Kuznetsova Citation2017, p. 10). Most Ukrainians initially applied for ‘temporary asylum’ and subsequently for residence or work permits, or for Russian citizenship (Kuznetsova Citation2017, p. 9). Granting refugee status to forced migrants from Donbas is not a strategy favoured by the state, as recognised refugees are not allowed to work but are eligible for state support; in this sense, granting refugee status to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians would have constituted a significant economic burden. Moreover, displaced people from Donbas have encountered restrictions on movement, with which other migrants in Russia have become all too familiar. As the authorities began organising transfers of Ukrainian refugees to other regions away from the border areas, ‘a ban on accommodating refugees in the near-border regions, Moscow, Saint Petersburg and some other areas was imposed’ (Mukomel Citation2017, p. 109). Strict quotas on work permits and registrations issued in Moscow and St Petersburg mean that formalising one's stay in these cities is difficult if not impossible for forced migrants, who are attracted there by higher levels of employment.

While this mass displacement has been virtually invisible to audiences in West European countries, it was a salient topic in Ukrainian and Russian public discussions in the initial phases of the conflict. A general attitudinal shift has been observed in Ukrainian society from charitable solidarity with IDPs to an increasingly suspicious and critical posture (Bulakh Citation2017, p. 51). Media narratives on IDPs in Ukraine at the beginning of the crisis typically featured positive interpretations of those displaced. Later, negative perceptions of IDPs, influenced by stereotypes and rumours, have appeared in the societal imagination (Bulakh Citation2017). While explicit discrimination and negative attitudes towards IDPs are still relatively rare in Ukraine, IDPs from the east are sometimes portrayed as bringing criminality and instability to other regions of the country. Furthermore, IDPs have received particular attention in the Ukrainian regional media because of the visibility of the issue in regions hosting large numbers of displaced people. The increasing volume of the displaced was seen as problematic and unsettling, especially by local residents in Kyiv (Ivashchenko-Stadnik Citation2017, pp. 31–2). Ukrainian researchers and NGOs working with displacement observed that negative representations of IDPs had already appeared in the Ukrainian media in 2014 (Andreyuk Citation2015, p. 3). Typical negative media tropes include suspicions of IDPs abusing social benefits and exhibiting anti-Ukrainian sympathies. After it became evident that the conflict in the eastern regions was ongoing and that displacement was to be a long-term issue, ‘the overall decreasing quality of life and well-being in Ukraine became more frequently blamed on IDPs. Thus, a so-called “return of the 90s” is now often framed as IDPs’ fault’ (Bulakh Citation2017, p. 55). It should be noted that positive representations of IDPs may have been present in the media as well but were less noteworthy for the above-mentioned researchers.

In the Russian media, the discourse on Ukrainian refugees takes place in the context of a nation-building project that has intensified under President Vladimir Putin (Hutchings & Szostek Citation2015, p. 188). This project has manifested itself in the domestic media sphere as anti-Westernism, particularly in relation to the crisis in Ukraine. A common argument in this discourse has been that Ukraine's Western partners are not really interested in helping the country but simply use it as a pawn in their attempt to undermine Russia. The discourse on displacement has been coloured by this assertion. One important theme in the Russian media regarding the Ukraine conflict is a concern for vaguely defined Russian compatriots (sootechestvenniki) (Hutchings & Szostek Citation2015, p. 190). The fighting in Donbas, often dubbed a civil war in Russian media, is interpreted as a struggle for the self-determination and autonomy of the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine's southeast regions against the allegedly oppressive government in Kyiv (Mukomel Citation2017, p. 107). In official contexts, such as public statements by President Vladimir Putin or his former chief of staff Sergei Ivanov, the necessity to help Ukrainian refugees as a ‘fraternal people’ (bratskii narod) is emphasised (Kuznetsova Citation2017, p. 11). Mukomel argues that the discourse on Ukrainian refugees in Russia has been solely a utilitarian one, subordinate to the media wars surrounding the Ukraine conflict (Mukomel Citation2017, p. 108). According to Mukomel, media discourses on Ukrainian refugees in Russia have been split between demonising the Kyiv government as an enemy of the Ukrainian people on the one hand and demonstrating Russian success in accommodating the forced migrants on the other (Mukomel Citation2017). Attention to this issue has mirrored military dynamics, and after positions at the front became entrenched, the topic was largely abandoned.

Furthermore, a media monitoring project led by Mukomel found that both civil activist groups involved in helping forced migrants from Ukraine and those vocally opposing Ukrainian refugees have appeared in Russian social networks (Mukomel Citation2017). The groups opposed to Ukrainian refugees accuse them of welfare parasitism and scamming, similar to the Ukrainian media. These sentiments have not, however, found much support in the wider public discourse in Russia. Despite the Donbas conflict remaining unresolved, the topic of Ukrainian refugees in Russia was already disappearing from the headlines in 2015. According to Mukomel, this was connected to a change in state policy towards the forced migrants: ‘special privileges [for Ukrainian refugees] were abandoned and the requirements to legalise a refugee's stay in the territory of Russia were made more stringent. As a result, the continuation of a propaganda campaign was no longer needed’ (Mukomel Citation2017, p. 108).

Displacement and the nation-state: a chicken and egg problem

The problems encountered by displaced people from Donbas, such as the inability to claim their benefits in Ukraine, or restrictions on their movement in Russia, would appear in essence to be technical issues that the respective governments simply lacked the experience or ability to solve; as time passes, such problems should disappear as the state machinery becomes more competent in dealing with displacement. However, I argue that the question is somewhat trickier since the treatment of displaced people goes much deeper and touches upon the very justification of the state and its limits. Scholarly discussion on forced migration suggests that displaced people, instead of being essentially marginal to states, as they are often portrayed, in fact occupy a central place in relation to the state (Soguk Citation1999; Turton Citation2002; Fassin Citation2015). Soguk proposes that the figure of the refugee is ‘essential to statecraft, particularly at the intergovernmental level’ (Soguk Citation1999, p. 244). Refugees are so significant to statecraft because the international system divides the surface of the earth into discrete nation-states (typically) in full control of their territories, assuming a relationship of representation between states and their citizens. Persons outside their state or without state protection are an abnormality in urgent need of regimenting and controlling, so that the system of nation-states itself can be protected. Forced displacement is thus, according to Turton, ‘both a threat to, and a product of, the international system of nation-states’ (Turton Citation2002, p. 20). Migration and citizenship are the last bastions of state authority: if the state cannot protect its territory from outsiders, it does not have a reason to exist (Turton Citation2002, p. 70).

Because of the perceived challenges displaced people pose to the state's authority, states are anxious to limit the danger of displacement by subjecting forced migrants to policies regulating their movement and settlement. The range of actions available to states to protect themselves from displacement include integration, adaptation and deportation of forced migrants. Unfortunately for Ukraine, the IDPs cannot be deported because they are citizens of the country. A further complication in this specific situation relates to political unwillingness to give up Donbas: for example, actively organising mass evacuations of civilians could be interpreted as abandoning the region. This situation limits the scope of actions available for the Ukrainian state, in comparison with, for example, the Russian state, which could technically mandate deportation for unruly migrants (whether such orders would actually be carried out is another question). Since the inconvenient IDPs cannot be removed from Ukraine, the state needs to find other strategies to cope with displacement if it is unable to easily integrate and socially normalise the IDPs.

In general, it is often in the state's interest to maintain legal ambiguities regarding the status of migrants, because this ambiguity gives the state room to manoeuvre vis-à-vis migration policies and practices (Reeves Citation2013, Citation2014). The restrictions imposed on mobility by some Russian cities, such as quotas for work permits and registrations in Moscow and St Petersburg, in reality do not decrease undocumented migration to these cities, but simply push migrants beyond the margins of legality (Light Citation2010; Davé Citation2014). Deprived of the opportunity to formalise their residence legally, undocumented migrants have to rely on the services of semi-legal middlemen and corrupt police officers, who extract their own benefit from the migrants’ precarious situation. Undocumented migrants constitute a disposable workforce on whom the Russian economy essentially relies, as their labour is cheap and it is easy to get rid of them if they create problems (Reeves Citation2013; Davé Citation2014). It is not likely that Ukrainian refugees, despite being ‘brotherly’ Slavs, can avoid this conundrum, as restrictive migration policies appear to be driven by a concern for protecting resources rather than ethnicity (Light Citation2010).

Furthermore, it has been argued that the contemporary state can be best captured and comprehended at its margins, that is, in terms of population, territory and policy (Fassin Citation2015, p. 3). The state arguably becomes most visible in the way it treats its marginal populations, including refugees and other migrants, because in policing populations at its perceived borders, the state constructs those exact borders (Fassin Citation2015). These observations mean, first, that there is no forced displacement without the system of nation-states; also, that forced migration may be constitutive of the nation-state itself. In many cases, it is impossible to say which comes first. Because of this causal ambiguity, concentrating on discourses about forced displacement in Ukraine and Russia may reveal the authorities’ expectations regarding the state and the nation. More broadly, these cases also speak to the question of identity construction during conflict. The literature on conflict has only partially tackled this theme, as it tends to emphasise identity construction as a cause rather than an effect of war. However, in the case of Ukraine in particular, there are already signs that the conflict has contributed to the strengthening of the national idea: Uehling argues that ‘after the conflict with Russia in the east and the occupation of Crimea in the south, there is a clearer sense of what it means to be Ukrainian emerging’ (Uehling Citation2017, p. 70). Indeed, as Brubaker argues, high levels of group consciousness may be the result of ethnic conflict, rather than the other way around (Brubaker Citation2004, p. 19).

My research questions are therefore: how are displaced people from Donbas represented in government-owned media in Ukraine and Russia? What kind of attitudes and assumptions become evident in the way displaced people are represented in government media? What kind of identities are created by narratives about displaced people? What do the governments’ attitudes towards displaced people reveal about their ideology regarding the state or the nation?

Because of the connections explored above, I expect that the governments’ attitudes towards displaced persons from Donbas can offer insights into the politics of state- or nation-building in Ukraine and Russia. That is, looking at how forced migration is framed in government media can bring us closer to understanding the conceptions of these governments regarding the state, the nation and their borders. I also expect some degree of overlap between government representations of displacement and public discourse in both countries. For example, it could be expected that in Russia the displacement would be, at least to some degree, framed in terms of nationality, such as the fraternal nations trope. The situation could also be used to showcase Russians’ tolerance towards newcomers, as in the Russian media migration has often been framed in terms of societal harmony (Hutchings & Tolz Citation2015). In Ukraine, the typical media discourses would lead us to expect social othering of the displaced people. However, the displacement could also be framed as a strain on resources in Ukraine, as the country struggles with the economic consequences of the war and the collapse of its gross domestic product.

Data and methods

To answer my research questions, I collected articles discussing displacement from Donbas from the web archives of Uriadovyi Kurier and Rossiiskaya Gazeta across a two-year time period from 2014 to 2016. I conducted qualitative data analysis through the data analysis programme NVivo to recognise and quantify the distribution of main topics and tone in the publications, and also ideological discourse analysis to expose deeper ideological undercurrents in their reporting. The dataset analysed here contains 177 articles, 86 from Uriadovyi Kurier and 91 from Rossiiskaya Gazeta. Articles with displacement from Donbas as their main topic were collected from the newspapers’ online archives and stored directly in NVivo. The time frame for the collection of articles was from April 2014 until April 2016, so that in addition to comparison of the two newspapers, any changes in their reporting over time could be observed. After mid-2015, the number of articles discussing displacement began to decrease sharply, and by early 2016, articles on displacement were becoming few and far between. The opposite problem, a massive quantity of articles, presented itself, most of all in the beginning of the collection period, when the total number of relevant articles numbered in the thousands. For qualitative data analysis, this is too large a sample, as every article needs to be read and coded manually. For this reason, a number of shorter data collection points were selected for scrutiny; articles outside of these collection points were not included into the dataset. The critical time periods selected included the three months directly following the onset of fighting in Donbas in 2014, the months preceding and following the first ceasefire in September 2014 (Minsk I), the months around the second Minsk agreement in February 2015, and the early months of 2016. Because of this selection process, the dataset cannot be treated as a representative sample. However, as the task of this study is not to make statistically robust conclusions but to illustrate and compare the development of reporting in these publications, the selection of articles is considered appropriate.

Uriadovyi Kurier and Rossiiskaya Gazeta were selected as the data sources because as official government publications they represent types of discourse the governments of Ukraine and Russia want to promote, both to the domestic publics and abroad, and can therefore offer insights into the views of the authorities. Government-owned newspapers are less likely to reflect conflicting interests in society the way commercial publications might do and are readily comparable with each other. Still, while these government papers frame an official discourse, it is likely one at least partially shaped by societal views and concerns. It should be noted that Uriadovyi Kurier and Rossiiskaya Gazeta are not publications primarily meant for consumption by the general public but, rather, function as sources of information about government policy for the national media and regional-level authorities, therefore reinforcing government discourse at the sub-national level. Even if the papers could be dismissed as technocratic information leaflets or pure propaganda, I would argue that these functions do not dictate the specific forms that the narratives on displacement take; these forms are conditioned by ideological choices, the main interest of this essay.

Following a coding methodology used by Hutchings and Tolz (Citation2015), the main topic of the collected articles was identified from the headline and content and coded into a main topic category in NVivo. When an article contained several themes, the more prominent one was selected so that each article was coded only once into this parent category. Before data collection, I developed a deductive set of codes based on my research questions, in addition to themes recognised as salient in previous research on displacement, and proceeded with identifying further codes from the text. The main deductive codes included the tone of the article towards displaced persons (positive, neutral, or negative) and the presence of themes in the category ‘society–migrant relations’ (for example, employment and education). While reading the articles, I developed new codes and ways to group previously appointed codes. Grouping codes together finally produced three parent categories for the article topics: ‘crisis management’, ‘politicisation of migration’ and ‘society–migrant relations’ (and the category ‘other’ for articles that did not neatly fit with any of the main categories). These code categories allowed for the comparison of the tone and content of the articles in the two publications and across time in a systematic way. It should be noted that the codingFootnote4 was conducted by a single person, which necessarily affects the objectivity of the coding method.

After qualitative content analysis, the data were further analysed using the tools of ideological discourse analysis (IDA). The added value of conducting both qualitative content analysis and ideological discourse analysis with the same data is that while the first approach identifies salient themes in the publications, the latter shows how exactly these discourses work, and what is being achieved through them. Ideological discourse analysis is a theory of identity construction in politics; ‘politics’ in this case is understood, in a very broad sense, as any practice concerned with dynamics of power throughout human societies, not just parliamentary politics or the operation of political institutions. While conducting the ideological discourse analysis, I concentrated on the kinds of political identities the newspapers are attempting to construct, rather than the referential content of the political messages they produce.

A central concept for the creation of political identities in ideological discourse analysis is the ‘empty signifier’ (Laclau Citation2007, pp. 70–1). The operating logic of this concept is based on de Saussure's assertion that language, and in Laclau's view, any signifying system, is fundamentally a system of differences. Linguistic identities, or values, are purely relational, and the totality of language is involved in each single act of signification (Laclau Citation1996). In a system like this, the only possible relations between items of a signifying system are equivalence or difference, which are mutually exclusive relationships. Either two items are different and separate, or they are equivalent and essentially the same. Each element of the system has an identity only as far as it is different from the others. Herein lies a dilemma, however; there can only be a coherent system of elements if there is something that is outside of that system, that is, if something is excluded. In human interactions, limitless systems of relations, as exemplified by the concept of an infinite universe in physics, are impossible. This is where empty signifiers come in: as markers of the ‘outside’, they reveal the unity of the system. The exclusion of an element grounds the system as such (Laclau Citation1996, p. 38). This necessary distinction between the in-group and out-group can be articulated with the help of empty signifiers (Laclau Citation1996).

The main requirement for an empty signifier is, as the concept suggests, notional emptiness. An empty signifier lacks a signified. According to Howarth and Stavrakakis, ‘the articulation of [any] political discourse can only take place around an empty signifier that functions as a nodal point. In other words, emptiness is now revealed as an essential quality of the nodal point, as an important condition of possibility for its hegemonic success’ (Howarth & Stavrakakis Citation2000, p. 13). For example, the notion of ‘the people’ is a commonly used empty signifier, especially among populist movements: political actors often make extensive reference to ‘the people’, but never define or interpret the concept. It can mean whatever the audience wants it to mean, which can be as many things as there are people in the audience. Because the notion is emptied of all particular meaning, it can function as a unifying node, as the success of various populist movements attests. However, populist movements do not have a monopoly on using empty signifiers, as political identity projects of all kinds are necessarily built around empty signifiers (Norval Citation2000, p. 220). Further, it should be noted that populism, the practice of creating political identities around empty signifiers, is the very act of constituting the unity of a group, not simply the mobilisation of an already existing group (Laclau Citation2007, p. 73). Empty signifiers do not summon pre-existing social groups, they create them. In this case, both newspapers might be engaged in such group-building via concepts like ‘the enemy’. Especially in conditions of war, empty signifiers can be used to unite people against a common enemy, who is presented as the ultimate evil and a polar opposite to everything that the in-group represents.

Further, the construction of social divisions, or ‘othering’, is crucial for the stabilisation of the discursive system. Such social antagonism shows itself through the production of ‘political frontiers’: political division lines built between a united inside and an excluded outside, articulated with the help of the empty signifier. In this process, ‘social antagonism involves the exclusion of a series of identities and meanings that are articulated as part of a chain of equivalence, which emphasize the “sameness” of the excluded elements’ (Torfing Citation2005, p. 15). The concepts of the empty signifier and political frontier are specifically useful for the Ukrainian case, as they expose the way political identities are constructed through equation and exclusion. Ukrainian authorities are in a difficult position because, on the one hand, alienating the residents of Donbas from the Ukrainian nation would pre-empt the war effort but, on the other hand, the situation offers the perfect opportunity for nation-building through exclusion of the problematic regions and social othering of their residents. I am also interested in exploring whether any kind of identity construction vis-à-vis the displaced people is detectable in Rossiiskaya Gazeta in the conditions of an increasing nationalist trend in both public and state-level discourses, visible for example in the way that the Crimea campaign has been framed in Russia.

Representations of Donbas displacement: national unity or state capacity?

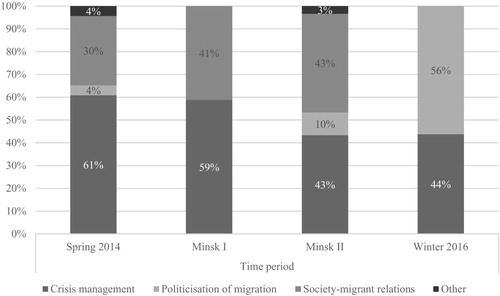

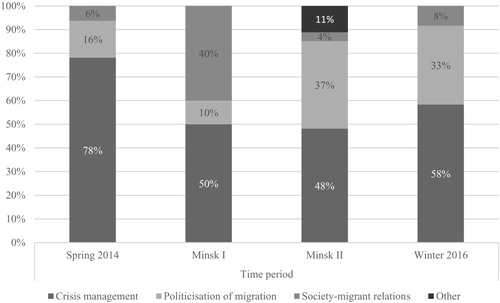

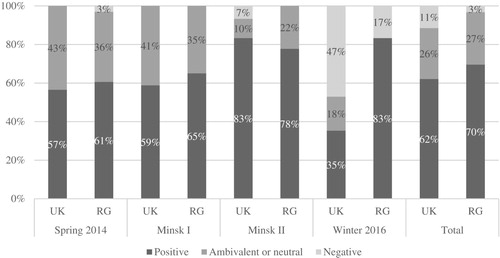

My analysis of Uriadovyi Kurier and Rossiiskaya Gazeta found both differences and similarities in the newspapers’ reporting about displacement and the transformation of their discourses over time. The main differences between the publications concerned the tone of the articles towards displaced people and the distribution of different main topics. The qualitative content analysis revealed, first of all, that the overall tone of the Russian newspaper was more positive than the Ukrainian one (see Appendix 3). The number of explicitly negative articles was low in both publications, with positive or neutral ones dominating. In the last observation period (early 2016), the prevalence of articles about ‘fake IDPs’ in Uriadovyi Kurier turned the paper's tone more negative, thus suggesting a shift to a more polarised take on displacement. As articles about foreign donors often represented their assistance as a relief or an opportunity for Ukraine, I coded them as positive. Second, the publications addressed different themes when discussing displacement (see Appendix 2). The Russian paper discussed crisis management measures more than the Ukrainian one, despite my assumption that Ukraine's budget shortfalls and problems with institutional design would make the questions of state capacity more salient for Uriadovyi Kurier. Correspondingly, the Ukrainian paper was more concerned with stories about the relations between migrants and society; this topic was almost absent in the Russian paper. This finding is surprising, since research on representation of migration in Russian media has shown that stories about social harmony tend to be an important trope (Hutchings & Tolz Citation2015). More reporting would, therefore, be expected about the way Russian society receives and integrates the migrants, in an attempt to show its tolerance and flexibility. Also, the main actors mentioned in the articles were different for the two publications: in the Ukrainian publication, volunteers, civil society actors and foreign partners feature prominently, whereas in the Russian paper, the central state and the executive remain the most important actors throughout the observation periods.

Third, the tone and the themes discussed changed over time, especially in the Ukrainian paper. As already mentioned, the tone of the articles towards displaced people became more polarised in Uriadovyi Kurier over time, with negatively coloured stories about fake IDPs increasingly contrasted with positive reporting about foreign donors helping Ukrainian regions deal with displacement. Meanwhile, the tone towards displaced people was mainly positive in the Russian publication throughout. In both publications, a multiplicity of themes in the beginning of the displacement was reduced to a couple of salient topics by 2016. In 2014, active crisis measures such as publishing information for displaced persons and reporting from the regions close to the active combat zones, as well as articles about employment dominate Uriadovyi Kurier's reporting on displacement. By 2016, international cooperation and fake IDPs were the main story types in Uriadovyi Kurier. For the Russian paper, crisis management measures remain the most important theme throughout the two-year period. By 2016, the themes discussed in the newspaper boil down to crisis management and a few politically motivated stories; for example, about draft dodging as motivation for moving or highly visible evacuations of individual children.

After applying ideological discourse analysis methods to the articles, I found that, despite my expectations, discourse about displacement did not centre very strongly around questions of nationhood or nationality in both publications. Instead, the Russian paper seemed to discuss another aspect of the state: its capacity to manage mass-scale displacement, demonstrated by the proliferation of crisis management stories. However, I argue that Uriadovyi Kurier does attempt to construct Ukrainian national unity by drawing a political frontier between ‘real’ and ‘fake’ IDPs, that is, IDPs who relocated to government-controlled areas, and those who did not. In the newspaper's reporting, Ukrainian national unity is delimited with the figure of the ‘fake’ IDP, acting as an empty signifier. The ‘fake’ IDP is juxtaposed with ‘honest’ IDPs (who are entitled to benefits), and is equated with terrorists, corruption and separatists backed by Russia. This act of social othering is not articulated in the language of ethnicity or religion, for instance, but is determined by political loyalties manifested through the ‘right’ kind of movement. The choice to flee westwards to government-controlled areas or to stay put in the NGCAs justifies civilians’ inclusion in, or exclusion from, the national community. This conclusion emerges only gradually: Uriadovyi Kurier's representation of IDPs changes over time from moderately positive to a more polarised picture with both extremely positive and extremely negative representations. For example, in summer 2014, articles describing life in displacement portray the IDPs largely in a positive manner and often mention how their political outlook has changed from political agnosticism to active support of the Ukrainian state as a result of the conflict. For example, an article dated 27 June 2014 recounts the story of ‘Mrs Tetiana’ from Kramatorsk, whose family was forced to leave their house after the referendum on the Donetsk People's Republic's (DNR) status the previous May, as Tetiana's husband was a member of the well-known Dnipro battalion in the Ukrainian army. Tetiana said her family did not realise they were pro-Ukrainian until the recent events (Bilovytska Citation2014). A long article profiling a family that moved to Rivne from Luhansk describes how the family began speaking Ukrainian out of respect for their hosts. Halyna, the head of the family, praises Rivne as a more civilised, hospitable and kind environment than Luhansk (Omelianchuk Citation2014).

Further, many articles published in Uriadovyi Kurier in 2014 feature explicit calls to strengthen national unity. One article, commenting on university admission procedures for IDP students in September 2014, ends with a moralistic lecture about national unity and the inadmissibility of giving in to enemy propaganda among students:

[The problem] is about dividing [people] into one's own and strangers [podil na svoikh ta chuzhykh]. … We must remember that … we are all one people [odyn narod]. Newcomers from the east sometimes face a prejudiced attitude from people in other regions, laid down on the soil prepared by propaganda. Usually they are blamed for what happened, or for an atrophied sense of patriotism. There is only one solution here—do not play into the hands of the enemy, do not give in to provocations. (Ivanchenko Citation2014)

This concern with ensuring a sense of national unity by urging IDPs and those encountering them to surpass the false notion of an internal division in Ukrainian society, created by Russian propaganda, amounts to a hegemonic struggle for identity (Torfing Citation2005). The division between east and west, traditionally seen as one of the major fault lines of political opinion in Ukraine, is rejected in exchange for the idea of a unified nation, including the right kind of IDPs. The author argues that newcomers from the east need to be patiently informed how volunteers are helping at the front, so that the IDPs too can understand the importance of unity in the face of adversity (Ivanchenko Citation2014).

Over time, these mainly positive representations of IDPs as politically loyal to the Ukrainian state slowly give way to more negative and ambivalent representations in Uriadovyi Kurier. The themes of IDP employment and adaptation issues were often discussed in Uriadovyi Kurier in 2015. These topics evoked both sympathy and suspicion in how Uriadovyi Kurier portrayed the IDPs, who were seen, in alternation, as victims of unfair stereotypes or as dishonest about their professional qualifications, claiming to have lost their diplomas or work books during military operations, and prone to blame others for their problems. By 2016, the trope of ‘fake’ IDPs as funders of terrorism emerges as a dominant theme in the newspaper's reporting, mainly because articles on other topics related to the conflict became so scarce. The main suspects in these articles were people residing in NGCAs and fraudulently claiming benefits through registration in the government-controlled areas.Footnote5 Around the same time, the rest of the articles discussed international cooperation with Western countries. In 2015, several articles reported about a modular town built for displaced people in Kharkiv with German assistance (Halaur Citation2015; Matsehora Citation2015). Other articles addressing this theme discuss, for example, humanitarian aid and financial assistance promised or delivered from Europe. Exact sums of foreign assistance are often mentioned, as well as the targets or conditions set by the donor, for example to incentivise decentralisation (Bilovytska Citation2015; Lohanov Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2016c).

As mentioned earlier, the Ukrainian government suspended the payment of social benefits to 150,000 people and implemented a verification procedure for IDP registration documents as a condition for continuing any kind of payments to IDPs in February 2016.Footnote6 These measures were enthusiastically discussed in Uriadovyi Kurier during early 2016. Ukraine's difficulties with the state budget, drained by the conflict, were often mentioned as justification for these measures. The alleged fake IDPs themselves are never interviewed in Uriadovyi Kurier, nor are their motivations discussed or interpreted. Articles on the topic discuss the clever methods of misappropriation used by the fraudsters, who appear as nothing short of hardened criminals. According to the then-Minister of Labour and Social Policy, Pavlo Rozenko, who is quoted in several articles, huge criminal schemes have been built on distributing assistance to IDPs, with multi-billion sums in circulation.Footnote7 Rozenko claims that some of these funds from the Ukrainian budget and Ukrainian taxpayers flow into the pockets of corrupt officials, terrorists and Russian ‘invaders’ (Iurchenko Citation2016). A representative from the state security service of Ukraine (SBU), commenting on the investigations into alleged benefit fraud, stated in February 2016: ‘now that Ukraine is at war with an aggressor, in our state budget every penny is important. I responsibly emphasize: we do not threaten decent people [poriadni liudy] who migrated from the occupied territories to safe areas and actually live there’ (Koval Citation2016). The implications of this statement are evident: IDPs who conform to the state definition are honest, decent people, who can be included in the national unity of Ukraine, while so-called false IDPs staying in rebel-held areas are not. It is reported that the fraudsters cooperate with corrupt officials in regional branches of state institutions (Koval Citation2016).

I argue that the figure of the ‘fake’ IDP can be seen as a constitutive myth in the ‘hegemonic struggle’ (Torfing Citation2005) to build a political identity in Uriadovyi Kurier's discursive system. As argued above, no coherent identity can exist without the exclusion of something else, which thus articulates the limits of that identity. For a national unity to exist in Ukraine, and for the IDPs to be included in that unity, some elements have to be excluded. In the drive to exclude some elements from the whole is where the empty signifier of ‘fake’ IDPs comes in handy: the category of the ‘fake’ IDP absorbs all politically suspicious migrants from the combat zone. Furthermore, a chain of equivalence is constructed between ‘fake’ IDPs, professional criminals involved in organising the benefit fraud schemes, corrupt officials and, finally, the ‘terrorists’ directly or indirectly benefiting from the money flows to NGCAs. Ivashchenko-Stadnik is correct in her assessment that ‘in a state-sponsored war, civilians living in the enemy camp, even if they are not engaged in hostilities, are conceived by the other side as “failed citizens”’ (Ivashchenko-Stadnik Citation2017, p. 27).

In conclusion, the above analysis shows that Uriadovyi Kurier's portrayal of IDPs plays a specific role in consolidating Ukraine's nation-building project. If, in the beginning of the crisis, people fleeing Crimea and Donbas are primarily portrayed positively as victims of oppression who made the conscious decision to align themselves with the Ukrainian state, later reporting by Uriadovyi Kurier concentrates solely on ‘fake’ IDPs and foreign help in dealing with displacement. A political frontier is constructed between Ukrainian national unity, exemplified by ‘honest, hard-working’ IDPs who fled to GCAs (and stayed there) on the one hand, and the thieving ‘fake’ IDPs residing in NGCAs, corrupt officials and Russian occupiers, on the other. Unfortunately for the IDPs living in NGCAs, they are the constitutive ‘outside’ of the political identity that Uriadovyi Kurier constructs. These findings testify how struggles with state-building become acutely visible through displacement and what goals the social othering of displaced people may serve. Less attention is given to the Ukrainian state-building project in Uriadovyi Kurier, although the articles about engaging foreign donors in IDP assistance could be interpreted as an attempt to address this topic. As in Dunn's research on IDPs in Georgia (Citation2012), managing internal displacement can be tied to geopolitical orientation: by involving Western states as partners and donors in IDP assistance programmes, Ukraine can tie itself more tightly to the West, its preferred reference group.

Meanwhile in Rossiiskaya Gazeta, the Russian state's capacity to deal with the sudden displacement is brought to the fore. This capacity is explicitly and implicitly contrasted with the Ukrainian state and its Western partners. However, applying the analytical tools of ideological discourse analysis on the Russian data proved quite difficult; it appears that Rossiiskaya Gazeta does not use the topic of displacement to engage in a national identity construction project in the same way as Uriadovyi Kurier. Most of the articles in Rossiiskaya Gazeta are factual news reports and feature few interviews with displaced people themselves. The main actors in Rossiiskaya Gazeta's reporting on Donbas displacement are the Russian state and regional authorities in their capacity in executing policies. As mentioned earlier, crisis management remains the main topic of articles throughout the data collection periods. While articles in Uriadovyi Kurier suddenly become politicised, with dramatic stories about fake IDPs in 2016, articles in Rossiiskaya Gazeta, by contrast, seem to become more bureaucratic and technical towards the end of the observation period. The involuntary migrants themselves figure little in Rossiiskaya Gazeta's reporting about displacement, and the relations between the displaced people and their host communities are discussed less than in the Ukrainian paper. Instead, the articles emphasise the Russian state's consummate capacity both to secure societal peace and stability, despite sudden and large-scale immigration, and to provide for the refugees. Applying the concepts of ideological discourse analysis to the Rossiiskaya Gazeta data thus seems tendentious. No apparent empty signifiers were detectable in the data, and the refugees themselves figure very little in the discussion about displacement, except when their experience had direct political import, as in the case of draft evasion discussed especially in early 2015 in connection with a military mobilisation campaign in Ukraine. This topic was used in Rossiiskaya Gazeta to emphasise the interpretation of the conflict as a civil war.

Although several salient themes, for example, the trope of fraternal nations, are available in Russian public discourse for interpreting the Donbas displacement in terms of identity, Rossiiskaya Gazeta makes very little use of them. Even when the fraternal nations trope does appear, it is subordinate to emphasising Russian state capacity. For example, in a June 2014 report about the speaker of the Federation Council Valentina Matvienko's visit to the city of Vladimir, where some Ukrainian refugees were settled, Matvienko is quoted as saying that Russians and Ukrainians living in Ukraine are ‘our kindred’ (rodnye nam lyudi). Matvienko takes the chance to express solidarity with the residents of Luhansk and Donetsk, and to accuse Ukraine of using anti-Russian propaganda to hide the fact the Ukrainian state is not coping with the situation. Russia, on the other hand, is capable of receiving all Ukrainians in need of help, according to Matvienko (Petrov Citation2014).

Similarly, compatriot resettlement programmes, which could potentially be used to evoke identity-based interpretations of the crisis, are mainly discussed as solutions to economic problems in Russian regions. As an educated, Russian-speaking refugee with useful skills, the compatriot from Donbas is characterised as a welcome figure, especially at the beginning of the conflict. However, the compatriots from Donbas themselves remain silent in the articles. In 2016, a few articles comment on the numbers of Ukrainians who have received Russian citizenship through the resettlement programmes, from a rather technocratic viewpoint. An article from April 2016 reports that more than one million Ukrainian citizens have arrived in Russia following the events in Donbas and mentions that about 120,000 Ukrainians have applied for participation in the resettlement programmes: it is emphasised that the overwhelming majority of the compatriot resettlement programme participants are of working age (Zamakhina Citation2016). In a similar vein, the head of the presidential administration Sergei Ivanov, quoted in 2015, urges the leaders of Russian regions to alleviate the burden of refugee flows on the Rostov region, saying, ‘these are our brotherly Slavs with good professions, they will help us both with the demographic situation and with improving the situation in the labour market’ (Sadchikov Citation2015). In this way, even if some of the Rossiiskaya Gazeta articles make explicit reference to ‘brotherly Slavs’ or Russian-speaking compatriots, it is in connection with their potential to reverse negative population trends and provide the Russian labour market with a capable workforce. Comments about their possible co-ethnicity with Russians are thus subordinate to their instrumental role in the economy.

In Rossiiskaya Gazeta, the ability to handle large-scale immigration is also related to questions of geopolitical orientation. Russian state capacity to deal with the influx of displaced people from Donbas is often contrasted with Ukraine and its Western partners. In a long interview following news reports about unprecedented numbers of asylum-seekers arriving to Europe, the head of the Federal Migration Service (FMS), Kontantin Romodanovskii, fantasises about streams of Europeans, disappointed with their states’ multicultural policies, moving en masse to Russia. He mentions the nearly ‘2 million Ukrainian refugees in Russia’ as a demonstration of Russia's ability to receive and integrate migrants. According to him, most of those who have arrived from Ukraine have received legal status, work and accommodation, and Russians have not been bothered by them in the least (Zhandarova Citation2016). The quote from CSTO's Nikolai Bordyuzha, cited in the beginning of this essay, echoes a similar viewpoint.

A political frontier of sorts is thus drawn in Rossiiskaya Gazeta between Ukraine together with its Western partners on the one hand, and the Russian state on the other. The actors portrayed most negatively in the Rossiiskaya Gazeta articles are the Ukrainian government and military. For example, an analytical piece reflecting on the year since the Maidan revolution quotes a refugee from Mariupol: ‘it was hell there. The degree of people's hatred toward the authorities in Kyiv has grown a lot. Those who were against the authorities were repressed. … They caught people and tortured them, like in the movies’ (Ionova Citation2015). The article questions whether the government and authorities of Ukraine truly represent the will of the people. Instead of using the topic of displacement to advance nation-building goals, Rossiiskaya Gazeta thus takes the opportunity to make geopolitical claims about Ukraine and its emerging Western partners, and to possibly advance a project focused on a strong state identity. Of course, the ideal of a strong state has already been recognised as a defining feature of the Putin-era political thought.Footnote8 Further, taking into account the problematic nature of any efforts to define the Russian nation in more ethnic terms, my findings seem less surprising.

Conclusion: statecraft or statehood

To summarise, I found that both governmental publications, Uryadovyi Kurier in Ukraine and Rossiiskaya Gazeta in Russia, use the theme of displacement to discuss other politically pressing matters. Uriadovyi Kurier attempts to construct Ukrainian national unity by drawing a political frontier between ‘real’ and ‘fake’ IDPs from the occupied territories. I argue that the moral panic about ‘fake’ IDPs as terrorist collaborators is not just a matter of protecting scarce resources, but an attempt to stake out the national community by delimiting its margins. The IDP question in Ukraine thus brings to the fore the way in which the state attempts to negotiate its relationship with its citizens. Looking at the Uryadovyi Kurier articles across the two-year observation period, it is evident that the Donbas crisis expedites the discursive process of Ukrainian nation-building: the initially fuzzy categories slowly change into an increasingly solid political division separating the Ukrainian national community from its enemies. Indeed, my analysis gives support to Uehling's assertion that the conflict has contributed to the emergence of a stronger national identity in Ukraine (Citation2017). The Ukrainian paper also presents managing displacement as an opportunity to engage Western donors as partners, which would both relieve pressures on regional budgets and assert Ukraine's preferred geopolitical reference group. Rossiiskaya Gazeta also refers to geopolitics, but mainly to discredit Ukraine's new leadership, to emphasise Russia's superior preparedness to manage displacement, and to distance itself from Ukraine and the West. The paper seems more preoccupied with proving Russian state capacity in connection with the displacement crisis than the Ukrainian paper. The figure of the displaced person thus serves mainly a geopolitical function, or one highlighting the strong Russian state.

My expectation that the issue of displacement would bring to the fore questions about the limits of the state or nation is confirmed, but the discourses in Ukrainian and Russian governmental publications are not mirror images of each other. The discourse about displacement in both publications does relate to the state, but from different angles. Namely, my analysis matches Jansen's argument for analytically distinguishing between two aspects of the state, statehood and statecraft (Citation2015). According to Jansen, questions of statehood relate to what the state is, claims to be and should be: they explore the ‘legitimacy of a polity’ and its ‘administrative-territorial anatomy’, for example, questions of sovereignty and representation in terms of identity (Jansen Citation2015, p. 12). Statecraft, in turn, is concerned with what the state does, claims to do and should do; in a word, state capacity. Key concerns of statecraft are the ‘provision of material conditions and temporal structures for the unfolding of “normal lives”’ (Jansen Citation2015, p. 12). Against this analytical background, it is quite clear that Uriadovyi Kurier's articles on IDPs from Donbas primarily deal with questions of statehood, while those in Rossiiskaya Gazeta essentially discuss statecraft.

It is intriguing that the Ukrainian and Russian government newspapers would in this context emphasise contrasting aspects of the state. Media analyses from Russia and Ukraine indicate that the public discourses about the war in Donbas have involved, among other issues, questions of state capacity in Ukraine and the nation-building agenda in Russia (Andreyuk Citation2015; Mukomel Citation2016, Citation2017; Ivashchenko-Stadnik Citation2017). In the case of these governmental newspapers, the situation appears to be reversed, which is noteworthy because the issue of state capacity, especially in relation to corruption, constitutes a persistent topic of political discussion in Ukraine. Euromaidan, the ‘revolution of dignity’, started out as a protest against corruption, clearly a question of statecraft (Sakwa Citation2015). However, it has been claimed that the Maidan protests eventually became radicalised along the lines of Ukrainian nationalism (Sakwa Citation2015), demonstrating how nationalist rhetoric can mobilise people and demobilise alternative politics (Jansen Citation2015, p. 10; Sakwa Citation2015). Like the 2004 Orange Revolution, which had similar motivations, the Euromaidan eventually failed to deliver on its participants’ expectations, such as putting an end to corruption. Instead, group or identity based concerns with, for example, the state language and calls for national unity, dominate the executive's discourse. While reporting about displacement from Donbas, Uriadovyi Kurier attempts to make even the question of corruption into an issue of nationhood by equating corrupt officials with the separatists and excluding them from the Ukrainian national community. Of course, it may not be that surprising that Uriadovyi Kurier would not want to draw explicit attention to the thorny problems of state capacity in connection with managing the displacement, in order to avoid criticism. It could also be argued that the paper occasionally does evince concern for state capacity, since the IDPs are represented as a strain on resources in some articles, and the newspaper discusses ways to engage foreign donors in solving problems related to managing displacement. However, in the newspaper's reporting, the solution to problems caused by displacement is either exclusion of IDPs of the wrong kind or increasing state capacity by involving foreign states and civil society. That is, instead of reforming the state machinery, the government wishes to show that the solution can be outsourced.

It is possible that the Russian government newspaper avoids the topic of nationhood in connection with displacement because it is not currently politically expedient to discuss the relationship between the state and nation. Taking an explicitly ethnicised stance on Donbas displacement would be problematic, because it would push the interpretation of the ‘Russian nation’ towards a more ethnic ground and close some policy avenues that the Kremlin wishes to keep open (Shevel Citation2011b; Laine Citation2017). At the same time, questions of state capacity and the distribution of resources become obviously important in the context of an economic downturn and the sanctions imposed by Western countries in response to Russia's involvement in Ukraine. These developments may threaten the well-known Putin-era social contract based on economic stability. Also, my findings fit the narrative of emphasising the image of a strong Russian state, which was important even before these more recent concerns.

Ultimately, it seems that both government papers are less interested in portraying the lived experiences of the displaced. While some identity polarisation among current and former Donbas residents has been observed as a result of the conflict, many displaced people still do not see a discrepancy between a commitment to Ukraine and mixed or bilingual identities (Sasse & Lackner Citation2018). Also, the absolute majority (71.5%) of Ukrainians polled in a recent survey opined that most IDPs (pereselentsi) from Donbas consider themselves Ukrainian citizens, with the same rights and obligations as everyone else.Footnote9 Only 8% of the respondents disagreed with the statement, showing that there may not be much societal support for the government's campaign of social othering. The government representations described in this essay thus do not necessarily reflect the reality in which both the displaced people and their receiving communities live, making the states vulnerable to unforeseen societal reactions. More work is especially needed to research former Donbas residents now living in Russia, whose attitudes are so far quite understudied.Footnote10 As a social group with shared origins, their political influence, especially in the near-border regions, may prove significant.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emma Rimpiläinen

Emma Rimpiläinen, School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography and Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford, 51/53 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 6PE, UK. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 ‘Yatseniuk: 150 tys. pereselentsiv bilshe ne otrymaiut sotni milioniv’, Ukrainska Pravda, 21 February 2016, available at: http://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2016/02/21/7099812/, accessed 5 September 2018.

2 There is anecdotal evidence of people returning to Donbas or other parts of Ukraine, but little systematic research has been conducted about return migration so far. See, for example, Kuprianova (Citation2016).

3 Ukraine: Translating IDPs’ Protection into Legislative Action (Geneva, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2016), p. 5, available at: http://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/ukraine-translating-idps-protection-into-legislative-action, accessed 2 August 2018.

4 An overview of the coding scheme for main topics is offered in Appendix 1.

5 In general, when discussing IDPs, Uriadovyi Kurier seems to exclusively refer to people displaced from the non-government controlled areas, never IDPs from the government-controlled areas, although this is never explicitly mentioned.

6 Ukraine: Translating IDPs’ Protection into Legislative Action (Geneva, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2016), available at: http://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/ukraine-translating-idps-protection-into-legislative-action, accessed 2 August 2018.

7 The currency is not mentioned in the citation.

8 See, for example, Tsygankov (Citation2014).

9 Ukrainske Suspilstvo: Monitorinh Sotsialnykh Zmin (Kyiv, Natsionalna Akademiia Nauk Ukrainy Institut Sotsiolohii, 2018).

10 See, for example, Kuznetsova (Citation2017), Sasse and Lackner (Citation2018).

References

- Andreyuk, E. (2015) Relationship Between Host Communities and Internally Displaced Persons in Ukraine, available at: http://krymsos.com/files/5/9/59137aa--------------------eng.pdf, accessed 2 August 2018.

- Bilovytska, N. (2014) ‘Tymchasovi pereselentsi: “Holovne, shcho zhyvi”’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 27 June, available at: http://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/articles/timchasovi-pereselenci-golovne-sho-zhivi/, accessed 3 August 2018.

- Bilovytska, N. (2015) ‘Yevropa zbilshyt dopomohu na 15 milioniv yevro’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 29 January, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/news/yevropa-zbilshit-dopomogu-na-15-miljoniv-yevro/, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Bogdanov, V. (2016) ‘ODKB provedet spetsoperatsii po presecheniyu nelegal’noi migratsii’, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 5 February, available at: https://rg.ru/2016/02/05/strany-odkb-provedut-specoperacii-po-presecheniiu-nelegalnoj-migracii.html, accessed 5 September 2018.

- Brubaker, R. (2004) Ethnicity Without Groups (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

- Bulakh, T. (2017) ‘“Strangers Among Ours”: State and Civil Responses to the Phenomenon of Internal Displacement in Ukraine’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Uehling, G. (eds) Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective (Bristol, E-International Relations).

- Davé, B. (2014) ‘Becoming “Legal” through “Illegal” Procedures: The Precarious Status of Migrant Workers in Russia’, Russian Analytical Digest, 159.

- Dunn, E. C. (2012) ‘The Chaos of Humanitarian Aid: Adhocracy in the Republic of Georgia’, Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 3, 1. doi: 10.1353/hum.2012.0005

- Düvell, F. & Lapshyna, I. (2015) ‘The EuroMaidan Protests, Corruption, and War in Ukraine: Migration Trends and Ambitions’, Migration Information Source, 15 July, available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/euromaidan-protests-corruption-and-war-ukraine-migration-trends-and-ambitions, accessed 23 September 2019.

- Fassin, D. (ed.) (2015) At the Heart of the State: The Moral World of Institutions (London, Pluto Press).

- Halaur, S. (2015) ‘Mistechko z modulnykh budynochkiv dlia pereselentsiv z Donbasu vidkrylosia u Kharkovi’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 28 January, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/articles/mistechko-z-modulnih-budinochkiv-dlya-pereselenciv/, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Howarth, D. & Stavrakakis, Y. (2000) ‘Introducing Discourse Theory and Political Analysis’, in Howarth, D. R. & Norval, A. J. (eds) Discourse Theory and Political Analysis (Manchester, Manchester University Press).

- Hutchings, S. & Szostek, J. (2015) ‘Dominant Narratives in Russian Political and Media Discourse During the Ukraine Crisis’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Sakwa, R. (eds) Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives (Bristol, E-International Relations).

- Hutchings, S. & Tolz, V. (2015) Nation, Ethnicity and Race on Russian Television: Mediating Post-Soviet Difference (London, Routledge).

- Ionova, L. (2015) ‘Ukrainskie bezhentsy: Sobytiya na Maidane stali nachalom vsekh bed’, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 21 February, available at: https://rg.ru/2015/02/21/reg-ufo/bezhentsy.html, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Iurchenko, M. (2016) ‘Derzhava navodit lad sered pereselentsiv’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 19 April, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/news/derzhava-navodit-lad-sered-pereselenciv/, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Ivanchenko, M. (2014) ‘Ya znaiu, shcho vy robyly tsioho lita!’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 3 September, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/articles/ya-znayu-sho-vi-robili-cogo-litaya-znayu-sho-vi-ro/, accessed 3 August 2018.

- Ivashchenko-Stadnik, K. (2017) ‘The Social Challenge of Internal Displacement in Ukraine: The Host Community’s Perspective’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Uehling, G. (eds).

- Jansen, S. (2015) Yearnings in the Meantime: ‘Normal Lives’ and the State in a Sarajevo Apartment Complex (Oxford, Berghahn Books).

- Koval, L. (2016) ‘Realnym pereselentsiam nichoho boiatysia’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 27 February, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/articles/realnim-pereselencyam-nichogo-boyatisya/, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Kuprianova, I. (2016) ‘Donbass Refugees Leave Russia for Home’, Deutsche Welle, 21 January, available at: https://www.dw.com/en/donbass-refugees-leave-russia-for-home/a-18996846, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Kuznetsova, I. (2017) ‘One way ticket oder vorübergehende Zuflucht? Flüchtlinge aus der Ukraine in Russland’, Russland-Analysen, 331, 3 March.

- Laclau, E. (1996) Emancipation(s) (London, Verso).

- Laclau, E. (2007) On Populist Reason (London, Verso).

- Laine, V. (2017) ‘Contemporary Russian Nationalisms: The State, Nationalist Movements, and the Shared Space in Between’, Nationalities Papers, 45, 2. doi: 10.1080/00905992.2016.1272562

- Laruelle, M. (2015) ‘Russia as a “Divided Nation,” from Compatriots to Crimea: A Contribution to the Discussion on Nationalism and Foreign Policy’, Problems of Post-Communism, 62, 2. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1010902

- Light, M. (2010) ‘Policing Migration in Soviet and Post Soviet Moscow’, Post-Soviet Affairs, 26, 4. doi: 10.2747/1060-586X.26.4.275

- Lohanov, Ye. (2016a) ‘Pereselentsiam dopomohaiut nimtsi’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 6 January, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/news/pereselencyam-dopomagayut-nimci/, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Lohanov, Ye. (2016b) ‘Nove zhytlo dlia vymushenykh pereselentsiv’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 3 March, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/news/nove-zhitlo-dlya-vimushenih-pereselenciv/, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Lohanov, Ye. (2016c) ‘Frantsuzka bilyzna dlia vnutrishnikh pereselentsiv’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 15 March, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/news/francuzka-bilizna-dlya-vnutrishnih-pereselenciv/, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Mamutov, S., Moroz, K., Vynogradova, O. & Ferris, E. (2015) Off to a Shaky Start: Ukrainian Government Responses To Internally Displaced Persons (Washington, DC, Brookings Institution), available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/off-to-a-shaky-start-ukrainian-government-responses-to-internally-displaced-persons/, accessed 2 August 2018.

- Matsehora, K. (2015) ‘Nimechchyna pikluietsia pro pereselentsiv’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 17 January, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/news/nimechchina-pikluyetsya-pro-pereselenciv/, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Mukomel, V. (2016) ‘Adaptatsiya i Integratsiya Migrantov: Metodologicheskie podkhody k otsenke rezultativnosti i rol’ prinimayushchego obshchestva’, in Gorshkov, M. K. (ed.) Rossiya Reformiruyushchaya: Ezhegodnik Institut Sotsiologii RAN (Moscow, Novyi Khronograf).

- Mukomel, V. (2017) ‘Migration of Ukrainians to Russia in 2014–2015. Discourses and Perceptions of the Local Population’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Uehling, G. (eds) Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective (Bristol, E-International Relations).

- Mylonas, H. (2012) The Politics of Nation-Building: Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Norval, A. J. (2000) ‘Trajectories of Future Research in Discourse Theory’, in Howarth, D. R., Norval, A. J. & Stavrakakis, Y. (eds) Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Identities, Hegemonies, and Social Change (Manchester, Manchester University Press).

- Omelianchuk, I. (2014) ‘U Rivnomu nasha druha domivka’, Uriadovyi Kurier, 23 August, available at: https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/articles/u-rivnomu-nasha-druga-domivka/, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Petrov, V. (2014) ‘Matvienko: Rossiya smozhet prinyat vsekh bezhentsev s yugo-vostoka Ukrainy’, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 20 June, available at: https://rg.ru/2014/06/20/matvienko-site-anons.html, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Petryna, A. (2013) Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press).

- Reeves, M. (2013) ‘Clean Fake: Authenticating Documents and Persons in Migrant Moscow’, American Ethnologist, 40, 3. doi: 10.1111/amet.12036

- Reeves, M. (2014) Border Work: Spatial Lives of the State in Rural Central Asia (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Sadchikov, A. (2015) ‘Sergei Ivanov: SShA pytayutsya rassorit’ Rossiyu i Evrosoyuz’, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 29 January, available at: https://rg.ru/2015/01/29/ivanov-ukraina-site.html, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Sakwa, R. (2015) Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands (London, I.B. Tauris).

- Sasse, G. & Lackner, A. (2018) ‘War and Identity: The Case of the Donbas in Ukraine’, Post-Soviet Affairs, 34, 2–3. doi: 10.1080/1060586X.2018.1452209

- Shevel, O. (2011a) Migration, Refugee Policy, and State Building in Postcommunist Europe (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Shevel, O. (2011b) ‘Russian Nation-Building from Yel’tsin to Medvedev: Ethnic, Civic or Purposefully Ambiguous?’, Europe-Asia Studies, 63, 2. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2011.547693

- Soguk, N. (1999) States and Strangers: Refugees and Displacements of Statecraft (Minneapolis, MI, University of Minnesota Press).

- Torfing, J. (2005) ‘Discourse Theory: Achievements, Arguments, and Challenges’, in Howarth, D. & Torfing, J. (eds) Discourse Theory in European Politics (Basingstoke, Palgrave MacMillan).

- Tsygankov, A. (2014) The Strong State in Russia: Development and Crisis (New York, NY, Oxford University Press).

- Turton, D. (2002) ‘Forced Displacement and the Nation-State’, in Robinson, J. (ed.) Development and Displacement (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Uehling, G. (2017) ‘A Hybrid Deportation: Internally Displaced from Crimea in Ukraine’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Uehling, G. (eds) Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective (Bristol, E-International Relations).

- UNHCR (2016) UNHCR Ukraine Factsheet April 2016, available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/ukraine-situation-unhcr-operational-update-2-22-april-2016, accessed 25 May 2019.

- UNHCR (2017) Ukraine: Operational Update November 2017, available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/ukraine-unhcr-operational-update-01-30-november-2017, accessed 2 August 2018.

- UNHCR (2018a) Ukraine Fact Sheet, available at: http://www.unhcr.org/ua/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2018/05/2018-04-UNHCR-UKRAINE-Fact-Sheet-FINAL-EN.pdf, accessed 2 August 2018.

- UNHCR (2018b) UNHCR Submission on Russian Federation: 30th UPR session, available at: http://www.refworld.org/country,,UNHCR,,RUS,,5b082dbf4,0.html, accessed 28 July 2018.

- Wilson, A. (2014) Ukraine Crisis: What it Means for the West (New Haven, CT, Yale University Press).

- Woroniecka-Krzyzanowska, D. & Palaguta, N. (2017) ‘Internally Displaced Persons and Elections under Military Conflict in Ukraine’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 30, 1.

- Zamakhina, T. (2016) ‘Bezhentsam iz Ukrainy uprostili vid na zhitel’stvo’, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 22 April, available at: https://rg.ru/2016/04/22/bezhencam-iz-ukrainy-uprostili-vid-na-zhitelstvo.html, accessed 4 September 2018.

- Zhandarova, I. (2016) ‘Vstrechaem rabotoi’, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 28 February, available at: https://rg.ru/2016/02/28/glava-fms-ne-iskliuchil-uvelicheniia-chisla-migrantov-iz-evropy.html, accessed 4 September 2018.