Abstract

This article examines the factors that have contributed to the recent divestment of three ‘flagship’ Nordic investors from the Russian agricultural sector. These factors include corruption, pressure from regional administrations and the economic downswing arising from geopolitical tensions related to the Russian annexation of Crimea. The companies all sought to project calm as geopolitical tensions rose. This calm, however, belied a concern for the impact of the crisis on corporate operations. While the companies were affected by the geopolitical crisis, they had all been experiencing prior difficulties, and it is argued here that the Crimean crisis was only one factor, among others, leading to the divestments.

Building upon the work of Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 213) on foreign agroholdings (large-scale corporate farm operations) in Russia and Ukraine, this article identifies the external factors that influenced the decisions of three ‘flagship’ foreign agroholdings—Agrokultura, Agromino and Black Earth Farming (BEF)—to partially or wholly divest. Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 213) have previously analysed the consequences of what are essentially internal factors, in particular the role of stock market finance in shaping corporate strategies. The aim of this study is to draw attention to external factors that have influenced company strategy in unexpected ways.

The external factors under study are: corruption and theft, regional governmental pressure and the crisis arising from Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Of interest is the corruption that the companies under study claim to have experienced and the environment—formal or informal—to which the corruption relates. Given that corruption is more common in emerging economies because of weaknesses in institutional infrastructures (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 95), exposure to this phenomenon would be expected in Russia and Ukraine. Regional governmental pressure—a factor identified by smaller foreign investors in Russia (Lander Citation2017, p. 12) and known to exist in Ukrainian local administration (Allina-Pisano Citation2007)—is also under examination. Lastly, since the research of Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 200) predates the tensions surrounding the ongoing conflict and accompanying economic crisis in Russia and Ukraine, this article maps the responses of the three companies to the developing turmoil, and highlights how the turmoil affected corporate performance.

In line with Taylor (Citation2010), Pallot and Katz (Citation2017), and Lander (Citation2017), this article is not primarily interested in documenting company opinion as a true reflection of the situation, especially concerning issues of culture and governmental authorities. Rather, this article is interested in both critically examining corporate narratives and in identifying the focus of company concern. In effect, this study represents a qualitative undertaking to understand company decisions within their perceived operating environments.

This article is organised as follows. Firstly, the nature of the three ‘flagship’ companies is discussed, along with the problems they have experienced, followed by an overview of methodology, detailing the multi-sited approach. The findings are presented under the three sub-headings, covering each of the external factors. Lastly, the role and cost implications of these factors in ‘sinking the armada’ of these ‘flagships’ is discussed and the conclusions argued.

The problems of the ‘flagships’: historical background

More detailed information on the early history of these companies and their corporate strategies can be found in Kuns et al. (Citation2016). For the purposes of necessary background information, the present article will repeat only the most essential aspects of this story. While BEF’s operations were located in western Russia, Agrokultura and Agromino had operations in both Russia and Ukraine. To understand these companies’ strategies, it is important to understand that Russia has allowed farmland sales since 2002, while Ukraine has not allowed sales during the period of study (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 204); in Ukraine, agroholdings lease land from land owners, who are primarily former collective farm workers (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 204).

The companies all initially sought (albeit in slightly different ways and involving different geographies) to combine two main investment strategies: ‘asset-play’ and ‘yield-play’ (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 205). Whereas yield-play seeks to generate profits by improving agricultural production, the companies believed that under asset-play, the value of purchased Russian land would quickly climb beyond its initial purchase price, which, in turn, would push share prices upwards and lead to an increase in shareholder value. An emphasis on the asset-play had an important role in shaping the companies’ early strategy, with much focus given to land accumulation (Kuns et al. Citation2016).

The asset-play strategy initially appeared successful as increasing global food prices in 2007 and 2008 led to an increase in share value of the two companies, BEF and Agromino, that were publicly traded at the time (Agrokultura’s stock listing occurred in 2009). However, food prices collapsed later in 2008, which led to drastic declines in the two companies’ share values; as a result, the companies’ strategy shifted significantly in favour of yield-play. This shift proved difficult to accomplish in the short-term, not least because the asset-play had led companies to accumulate dispersed land banks, creating logistical problems for agricultural production. Thus, the companies consolidated operations, and whilst area cultivated and agricultural production improved significantly for all three companies, profitability remained elusive. Further, despite the shift in strategy, investors to the companies remained vocal of their primary preference for the asset-play (Kuns et al. Citation2016).

As is described in more detail below, the three companies’ Russian operations were largely sold to Russian businesses in the period from 2014 to 2018. In early 2017, BEF announced that it was being bought by Volgo-DonSelkhozInvest (Potter Citation2017), a company owned by the Kukura family, which is linked to the oil and gas giant Lukoil (Verdin Citation2017). The new entity, Volga-Don Agroinvest, is, according to a recent survey, the fifth largest agroholding in Russia (Burlakova Citation2018). Agrokultura was bought out in 2014 by Prodimex: a privately held sugar refiner that, according to the company website,Footnote1 is the largest privately owned Russian agroholding today. After acquiring Agrokultura, Prodimex then instigated a land swap deal with the Ukrainian agroholding, Myronivsky Hliboproduct (MHP): in exchange for all of Prodimex’s Ukrainian land, MHP swapped all of its Russian land (Zibrova et al. Citation2015). As a result, the original land assets of Agrokultura were split between two companies, across the two countries.

Agromino (then known as Trigon Agri) sold its 71,000-hectare Rostov cluster in late 2015, retaining only its dairy operation in the Pskov Oblast’, close to, and serving, the St Petersburg market. Although the company still owns land in Russia, it classified this dairy farm as a non-core operation and has since tried to sell it. Of the three ‘flagship’ companies, only Agromino remains today, albeit at a reduced size. Whilst the company achieved slight profits in 2017 and 2019 (Agromino Citation2018b, Citation2020), the combined profit of these two years was eclipsed by the loss that it made in 2018 (Agromino Citation2019). It changed its entire management in spring of 2018 citing ‘irregularities’ (Agromino Citation2018a); the second such management turnover in two years. In 2020, the company announced its attention to delist from the Stockholm stock exchange, thus signalling the death knell of the original business plan for which stock market finance was integral.Footnote2 The purchaser of Agromino’s large Rostov cluster was a Cypriot company that was impossible to identify beyond the name of ‘Ellania Business Inc.’ (Kunle & Skrynnik Citation2015). Kunle and Skrynnik (Citation2015) state that nothing is known about the company, and that there was no such company in the Commercial Register of Cyprus at the time of the purchase. Although Ellania Business Inc. appears Cypriot, conjecture can be made that it is Russian, given the large amounts of Russian money in Cypriot bank accounts, and the significant amounts of money—estimated by ratings agency Moody’s at $40 billion in 2013—that has re-entered Russian companies through Cypriot loans (Young Citation2013). As Dmitrii Rylko, General Director of the Institute for Agricultural Market Studies (IKAR), in an interview with AgroPortal, stated on Cypriot investment in general: ‘we don’t consider them [Cypriot-registered investors] foreign. They are of course Russian citizens. Otherwise, half of the agroholdings would be foreign’.Footnote3

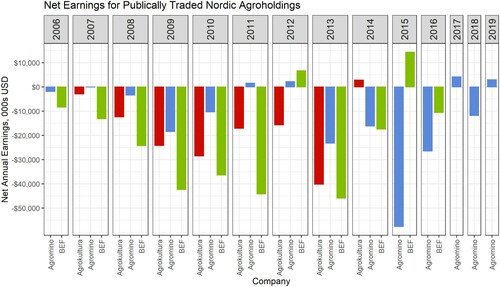

In general, the performance of the ‘flagship’ companies has disappointed investors, with far more annual losses incurred than profits (see ). Dividends—considered a sign of a financially healthy company—have been largely unpaid, with only Agromino distributing dividends to its shareholders in 2011 and 2012 (Trigon Agri Citation2013, p. 44). Whilst 2012 was a profitable year for all of the ‘flagships’, it should be noted that this period experienced relatively high agricultural commodity prices, and with many other farming businesses in the region also turning a profit that year (see Figure 1 in Kuns & Visser Citation2016), these accomplishments were unexceptional. The only striking performances were Agrokultura’s profit in 2014 and BEF’s in 2015, as both years experienced low commodity prices and geopolitical tensions. This notwithstanding, whilst BEF’s 2015 profit appeared to reflect the company’s cost efficiencies, its genesis also lay within a (pre-tax) $9.1 million land sale that boosted the company’s overall net earnings (BEF Citation2016). Also, both Agrokultura’s 2014 profit and BEF’s 2015 profit disappear after accounting for currency translation effects, though BEF’s 2016 loss would instead be a profit if taking currency into account (not shown in the figure).

FIGURE 1. Net Annual Profit/Loss, Translated to USD, from Consolidated Income Statements for Nordic Agroholdings, 2006–2019

Note: The figure shows profit/loss from continuing operations (this figure does not show the effect of currency translation on comprehensive income) for every year that data were available. All earnings figures have been converted into USD using the relevant central bank exchange rate for the last day of each year.

Though challenging ventures, there are examples of successful agroholdings. Many successful companies primarily focus on value-added lines of production—in particular, sunflower oil and sugar refinement—with crop production acting as a less important, yet still visible, segment of their business model (Kuns & Visser Citation2016). As well, there are a few successful agroholdings without value-added lines of production that—like the ‘flagships’—generate revenues chiefly from arable production.

Whilst there are multiple reasons behind corporate success and failure amongst arable agroholdings in the region, it is indicative that more consistently profitable publicly traded arable agroholdings tend to be concentrated in Ukraine, where agricultural conditions are usually more favourable compared to Russia (Kuns & Visser Citation2016; Kuns et al. Citation2016). Successful agroholdings are often owned or operated by Russian or Ukrainian nationals, rather than being under foreign ownership and management (Kuns & Visser Citation2016; Kuns et al. Citation2016), and are, importantly, older. This latter point—as argued by both Luyt (Citation2013) and the interviewee respondents of this article—suggests that for corporate arable ventures to be profitable, long-term time horizons are significant.

Methodology

The companies possess attributes that distinguish them from other forms of foreign agricultural investment in Russia and Ukraine. All are, or have been, publicly traded, and as a result, have been required to consistently publish corporate information—detailing financial and operational details—in the form of publicly available reports. Each company originally had in place a management agreement with its respective main investor, such that their highest ranking manager—the chief executive officer (CEO)—was provided by the main investor; these CEOs have been expatriates and are not of Russian ethnicity. The companies’ core focus has been on non-vertically integrated arable production and all operate on vast amounts of land.

The three companies come from a group of nine publicly listed firms that all share(d) these characteristics, and have invested in the Russian and Ukrainian agricultural sectors; today, only six of these firms are still in operation, with four having either been liquidated and/or sold, or absorbed by other members of the group as a result of corporate takeovers. As such, the three companies that we researched for this article represent a mix of former and current organisations. As Kuns et al. state, ‘this is a dynamic sector with companies regularly appearing, merging and disappearing’ (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 203).

This article is a collaboration between two research efforts on agricultural foreign investment, with the first author focusing on a range of foreign investors in Russia, and the second author focusing on publicly funded agricultural companies in both Russia and Ukraine. The combined efforts of both authors thus consist of a series of interviews between 2014 and 2016 with representatives of BEF, both inside and outside of Russia; and a series of interviews between 2014 and 2015 with representatives of the other two companies. We compare these interviews to the discourse in each of the companies’ publicly available corporate documents, transcripts of quarterly results presentations and audio recordings of investor telephone conferences. Additionally, we interviewed the heads of two Russian consultancy firms who were employed by the three companies and advised on issues of the operating environment and the effects of the crisis surrounding the annexation of Crimea. We also attended shareholder meetings of the three companies, held in Stockholm and Copenhagen, first in 2009, then more regularly between 2013 and 2017. Lastly, we used newspapers and other digital news sources to report the divestments and takeovers of the companies. We have, thus, taken an expansive, multi-sited approach (Marcus Citation1995, Citation1999) that has combined information from extensive primary and secondary sources, and used multiple methods (Philip Citation1998).

Together we interviewed six members of the senior management teams of the three companies to provide insight into corporate operations and experiences. The interviewees comprised of one former senior manager of Agromino, one current and one former senior manager of BEF, and one current and one former senior manager, and one former board member of Agrokultura. These six senior managers were European or North American, that is, of non-Russian ethnicity. Their job titles were current at the time of the research and, by virtue of their positions, the interviewees were appropriately qualified and had the deep operational knowledge to be able to speak on behalf of each of their respective companies. Following Rose (Citation1997, p. 305) and Kitchin and Tate (Citation2000, p. 213), we undertook a qualitative approach to the research by interviewing the participants in an in-depth, semi-structured format. These interviews yielded over 16 hours of audio recorded data that were coded to reveal the principal strands in the interviewees’ discourses.

As conditions set by stock markets require publicly traded companies to reveal and publish certain aspects of their businesses, which results in greater (financial) transparency than that found with private companies, corporate documents of the public companies constitute an underutilised source of information about large-scale agriculture in the former Soviet Union, as indicated in previous research (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 202). Likewise, research that was conducted by the second author at eight shareholder meetings between 2009 and 2017 was also an important source and, whilst the information divulged there did not differ from the publicly available corporate documents, it did allow for ethnographic observation and opportunities to approach potential interviewees. To gain access to these shareholder meetings for research purposes, it was necessary to acquire a minimal number of shares in each company; the second author still owns a small number of shares in Agromino, with the Agrokultura and BEF shares sold upon each company’s divestment. These shares are by no means a significant quantity that would present a conflict of interest to the research.

Though qualitative techniques have been applied with success to previous research on foreign investors in Russia and Ukraine,Footnote4 we must note caution with both the interview and corporate document sources; reality can be altered by interviewees, and corporate documents can ‘contain sources of error and discursive blind spots’ (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 202). As such, we do not seek to substantiate in detail the veracity of various claims and comments made both by interviewees and corporate documentation, but rather look to situate where these companies place their concern. Further, with respect to analysing the effect of the crisis in Crimea, we compare the narrative strands of the interviews and corporate documents to identify whether there are, indeed, discursive blind spots, and to highlight whether differing reporting environments can result in variance amongst the comments of the companies; that is to say, to highlight possible differences in how a company chooses to comment ‘officially’ to the public, and ‘off the record’ or anonymously to us as researchers.

Given the tough and complex business environment in these regions, we have chosen to anonymise the identities of the interviewees. Further, although we have used quotes from shareholder meetings in the analysis, we have, in these very few cases, anonymised the identity of the relevant companies; shareholder meetings are semi-public gatherings, where even journalists are often in attendance, but since those present were not aware that they were being observed, we felt it correct and proper to refrain from identifying them in the research.

Lastly, it is important to consider the representativeness of the researched companies; although three companies seem to constitute a relatively small sample size, there are, in fact, only six public arable farm companies remaining from an original nine. Though our research findings cannot be broadly applied to all foreign investors of this nature in Russia and Ukraine, they are an indication of the challenges that foreign investment faces in the region, and the adaptive processes that companies may choose to employ.

Analysis

Navigating corruption and theft

Definitions of corruption in academia often speak of the ‘use’ (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 93) or ‘abuse’ (Branco & Delgado Citation2012, p. 359) of power and public trust to the advantage of the private sector; however, it is widely recognised that corruption can also be ‘experienced, observed, or perceived … in the day-to-day lives of ordinary citizens’ (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 93). Unsurprisingly, academic opinion of corruption is negative, with a vast literature highlighting its evolution under the umbrellas of globalisation, and trade and investment (Osuji Citation2011, p. 43), and how it ‘undermines business success but also contributes to poverty, inequality, crime, and insecurity’ (Branco & Delgado Citation2012, p. 363). However, its foregrounding at the centre of business concerns, especially with respect to Western investment in developing countries, has been a relatively new development: Branco and Delgado (Citation2012, p. 357) highlight an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report in the early 2000s that claims that only 23% of corporate codes of conduct discussed bribery and corruption, and further show how the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the UN Global Compact (UNGC) and the FTSE4Good criteria guidelines aimed at tackling the phenomenon only began to appear in the same decade. This slowness to foreground corruption could, in part, be a result of ‘some kind of ethical justification for corrupt actions’ on the part of Western companies in developing countries, which does appear in some spheres of academia and contradicts the status quo: here, morality and corruption can be detached from one another, especially in, for instance, countries where corruption is widespread and considered the norm, thus rendering corruption as a form of ‘competitive requirement’ (Branco & Delgado Citation2012, p. 357).

There is a distinct difference between formal and informal corruption, with the former usually being enacted by individuals in positions of power within both the public and private sectors—for example, within governmental and corporate organisations—and the latter occurring ‘within the everyday experiences, observations, and perceptions of individual citizens’ outside of these official levels (Keig et al. Citation2015, pp. 94–6). The formal corruption environment, thus, involves corrupt actions ‘that originate from powerful high-level individuals within formal institutions’ (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 94), and the informal corruption environment consists of the ‘socio-cultural nature of corruption … [with the] essence of corruption … [being] found in its social and cultural foundations’ (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 96). It is interesting to note that firms functioning in either, or both, of these two corruption environments are not only more likely to encounter corruption, but are also more likely to participate in corrupt conduct (Keig et al. Citation2015, pp. 94–7). It is important to note that the formal and informal corruption environments may not necessarily be disconnected from one another, due to ‘grey area[s]’ that render differentiation challenging; examples of this include formal corruption environments within companies that have been fashioned as a result of informal, everyday corruption amongst employees, who themselves have ‘become socialized into the corruption to the point where they do not necessarily object to participating in it in business contexts’ (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 97).

Attention must be paid to research on smaller foreign investors in the Russian agricultural sector that acknowledges the overlapping nature of culture, corruption, gift-giving and blat (Lander Citation2017, p. 1). Modern-day corruption in Russia is believed to originate from informal practices under the Soviet system—thus also relevant to the Ukrainian environment—in which corruption was a crucial mechanism for the continuing functioning of the economy (Clark Citation1993, p. 260; Cheloukhine & King Citation2007, p. 108). These practices, condensed under the term blat, include favours, agreements, connections and exchanges (Ledeneva Citation2008, p. 119). Lander’s study showed that smaller foreign investors had issues of trust surrounding employee theft, and that fear of theft drove investors to adopt ‘near-paranoid levels of … excessive monitoring of their own workforce[s], … even if there had been no experience of theft before’ (Lander Citation2017, p. 16). With regard to the formal corruption environment, investors claimed that they had experienced ‘discrimination … [in] the business and legal environment, hampering the investors’ effectiveness of using regulatory systems’, including the court systems (Lander Citation2017, p. 13). Lastly, as the conduct of the smaller foreign investors was revealed, in some cases, to have resembled blat (Lander Citation2017, p. 15), a consideration of the behaviour of this nature amongst employees in the companies studied for this article—larger, corporate and more formal entities—is, thus, important and will help to fill the gap present in the academic literature that has formed as a result of a propensity to overlook the links between the two corruption environments (Keig et al. Citation2015, p. 109).

Interviewees alluded to both formal and informal corruption environments in discussing corruption in their immediate operating environments. One stated that they had ‘experienced a fair bit’ of corruption from ‘high-ranking political servants’, and how ‘a lot of the stuff they ask you to do … is not to serve public office’.Footnote5 This was thought to include the informal environment: ‘There was corruption everywhere … there was corruption at every step unfortunately … from the kolkhoz director and tractor driver, all the way up to the governor’.Footnote6 Indeed, corruption and illegal activity had been a concern for the companies from the outset; for example, Lindstedt writes how investors had quizzed BEF for ‘several hours asking about the Russian mafia’ (Lindstedt Citation2008, p. 64). Nevertheless, the corporate documents show that this was only considered on a formal level, whilst the possibility of informal corruption was ignored.

Specific examples of the formal corruption environment were varied. A BEF interviewee spoke of having ‘problems in the early days getting railcars reliably’, stating that ‘there was something more at play … [and] there were people [in politics] who agreed to try and keep … [BEF] out of that particular aspect of business’. This, apparently, was not uncommon: ‘There are quite a lot of situations like that in Russia’.Footnote7 An Agrokultura interviewee explained that the company had been the subject of a hostile takeover attempt by another company with a ‘Ukrainian crook’ in charge; this individual, it was thought, ‘had political ties … and he tried to buy off the authorities to steal everything’.Footnote8 Further, in 2014, one company representative discussed corruption in Russian and Ukrainian ports in a shareholder meeting, adding that it complicated grain exports.

During its third quarter telephone conference of 2015, an Agromino representative discussed how shortly after the completion of a land swap transaction, in which the company was divesting its land in the Rostov region, a ‘legal dispute … was drawn up against’ the company by ‘local operatives’ (Trigon Agri Citation2015a). The company felt that it had a ‘very strong legal case’, but because taking the dispute through the legal system would have ‘meant a drawn-out process’, the company decided to settle (Trigon Agri Citation2015a). During the telephone conference, a company representative explained:

I guess that it just shows that Russia is a difficult market … . The reason for it is partly related to how, overall, the environment in Russia has changed, which causes … local operatives to review all possible transactions. They’ve been part of [that] historically, and [they] see what they can squeeze out [of] something, or push for … extra from any other counterparties. (Trigon Agri Citation2015a)

Various instances demonstrated the close interaction of the formal and informal corruption environments. For example, a BEF interviewee believed that it was ‘much more of a daily war to do business out here than … in the West’:

We’ve had instances where we’ve had semi-criminal groups trying to put pressure on us as a company. We’ve had people putting their own people into our organisation and trying to get in control of things like sales and marketing, or trying to sabotage aspects of our business.Footnote9

Despite these court battles, the opinion of the companies interviewed—BEF in particular—was that the judicial process was ‘quite flawed’.Footnote10 One interviewee claimed that land ownership disputes were especially problematic at the local level because the legal system was undermined by blat behaviour and family links:

We’ve had situations where people were trying to challenge the land ownership, or some aspect to the process, and it had been set up very carefully with people inside our company with family links in the local land registration office, family links to the local court judge.Footnote11

when I was trying to straighten the company out, we spent over a million dollars in legal fees … . I took the view that we would absolutely defend our interests legitimately, and we would kick out any of these bastards that thought they were going to make money out of us.Footnote13

Every day; it’s absolutely crazy what these people steal, and there’s so much of it going on, and you don’t see it … . They’re very clever about it … . It’s fuel, it’s fertilizer, it’s herbicides, it’s seeds, it’s part of the harvest; and then you’ve got the outside people—the local villagers—coming into your fields, and stealing the corn, the wheat … . Our security people last year caught ten people out in the fields stealing corn.Footnote16

In response, the three companies employed an array of preventative measures to tackle theft. As well as traditional methods of protecting their assets, such as hiring security guards with dogs and building secure facilities, described as ‘fort[s] where we locked all our equipment behind high walls, and barbed wire’,Footnote20 companies also resorted to prosecution to deter other potential thieves, to ‘get that word around’ that the companies would use the legal systems available.Footnote21 Combined with these tactics, interestingly, companies additionally resorted to more technological approaches of theft prevention: GPS monitoring was used to track any unauthorised use of machinery, especially machinery movements that indicated the transfer of crops, seeds and fertiliser from warehouses to offsite locations, and fuel monitors were installed on machinery to measure any illegal draining from the tanks.Footnote22 In 2014, Agromino (then Trigon Agri) was presented with a Border Breaker Award by the Estonian Association of Information Technology and Telecommunications for ‘successfully integrating IT solutions (Telematics) with its business processes’. Amongst other benefits, the telematics system provided the company with ‘transparency of production process … [and] security of fieldwork and transportation processes’, gave a ‘continuous overview of machinery usage, completed work and results’, and allowed for the ‘optimization of inputs (fuel, seeds, fertilizers, workforce, etc.)’.Footnote23 While this GPS system, on the surface, appears as an example of ‘precision agriculture’—a farming management concept of using satellite technology to optimise crop yields—its main purpose has, in fact, been to monitor the labour force.

For the interviewees, family and local links were entangled within the problem of theft. This factor led to companies’ use of external security; for example, Agrokultura ‘had to hire a security company from other oblasts … because [it] could not have local security companies that guard against the local population’.Footnote24 These local and familial connections were deemed to fall under the description of blat behaviour:

There’s all kinds of relationships, and friendships, and alliances with the whole law-enforcing authorities, and with other local businesses; so the opportunity is rife for theft, and fraud, and collusion on a vast level.Footnote25

Navigating governmental issues

Control

One interviewee explained that the regional governments and local administration could be ‘more of a challenge than [a] support’, and that this held ‘probably less in Ukraine but more in Russia’.Footnote31 The ‘challenge’ seemed centred on regional government taking a controlling position:

‘What are you doing in terms of your operations? How?’ … . They would come in, they would ask … ‘Why are you planting this and that?’ And then they will tell you that you should really plant something differently, and they would also tell you how many people you should employ, and they would tell you what you should pay as a salary … .Footnote32

Interviewees seemed to accept that these were the prevailing market conditions of Ukraine and Russia, and assigned a historico-cultural aspect to the behaviour of the regional governments: ‘these are the things which are the leftovers from the Soviet period’. Moreover, continued the same interviewee, ‘unfortunately … especially in Russia, local administration[s] ha[ve] a lot of power’ and appear to follow ‘their own agenda’.Footnote37 The reasons given for this by the interviewees varied; regional governments were accused of attempting to create ‘political popularity’ through ‘trying to push [companies] … to pay more salaries to people’,Footnote38 whilst other examples pointed to more corrupt behaviour. One company representative claimed during a shareholder meeting in 2016 that the local government was trying to ‘leverage, or find some way to get a leg up [on the company]’, further saying that such behaviour was part of the Russian business landscape.

Like Agromino, BEF also became embroiled in a legal dispute in 2015, with the regional authorities. The senior manager of one of its daughter companies, Sosnovka-Agro-Invest, was entangled in an investigation of a fraudulent VAT reimbursement scheme (Korneyko Citation2015; Nespeshnii Citation2015; Larionova Citation2016). The CEO of BEF, quoted by the business news website Abireg (Larionova Citation2016), explained that the transport company that was supplying a service to Sosnovka-Agro-Invest ‘went bankrupt and didn’t pay its taxes’, which triggered the tax investigation. One consultant interviewee explained that the local tax authorities wanted to recover the debt owed by the transport company and so ‘went after’ its clients, including BEF.Footnote39 The senior manager was eventually fully acquitted, and BEF later sued Abireg for inaccurately reporting in 2015 that executives and top managers of the parent company were implicated in the investigation (Poltaev Citation2016). Abireg was ultimately forced to delete portions of the offending article (Nespeshnii Citation2015). The legal case, though, caused a reactionary response: BEF were vilified in the press as an example of foreign failures in the sector (Nespeshnii Citation2015; Kruglov Citation2016; Nikanorov Citation2016; Poltaev Citation2016), and the Chairman of the Duma Committee on Agrarian Policy, Mykola Gaponenko, when talking about BEF’s Russian subsidiary Agro-Invest during an interview in the regional newspaper Vremya Voronezha, threatened that the authorities would ‘find out … who uses land ineffectively, or does not use it at all … ’. Gaponenko continued that ‘[ineffectively used] land will be seized and sold on a competitive basis’ (Poltaev Citation2016). Around this time, Alexei Zhuravlev, Deputy of the State Duma of the Voronezh region, pushed for new federal legislation to limit the rights of foreign land ownership and leasing, though this was not necessarily prompted by the BEF case in particular (Kunle Citation2016; Nikanorov Citation2016).

Livestock pressure

Though post-Soviet Russia has become both self-sufficient in grain production and a global exporter of grain, it has failed to reach the same heights in its meat and dairy sectors (Lander Citation2017, p. 12). In 2010, the federal government produced the ‘Food Security Doctrine of the Russian Federation’, largely viewed as a political yearning for self-sufficiency that ignores competitor advantage (Vassilieva & Smith Citation2010, p. 2). The doctrine sets ‘minimum production targets as the share of domestic production: 95% for grain, 85% for meat, and 90% for milk and dairy products’ (Lander Citation2017, p. 12). It does not detail a time frame or means for achieving these targets, and instead instructs ‘public authorities … [to] pursue a common national economic policy … taking into consideration regional specifics’ (Vassilieva & Smith Citation2010, p. 11). The Russian Ministry of Agriculture budget supported this doctrine, with 60% of 2010 subsidies (roughly R163 billion, $5.8 billion) supporting the meat sector, and only less than 20% of 2011 subsidies (roughly R30 billion, $1 billion) supporting the grain sector (Welton Citation2011, p. 11). In 2012, the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine announced that it too aimed to increase the meat production target to 3.1 million tonnes by 2020 (Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine Citation2012).

Previous research on smaller, individual foreign investors in Russia has shown that arable farm businesses can feel pressure from regional authorities to diversify into livestock and dairy production, with the authorities themselves believed to be under pressure from the federal level above (Lander Citation2017, p. 12). The smaller investors claimed that the ‘pressure was not in the legal form, … applied ex post facto after land purchases had been agreed and ratified, and without any consideration of … economic viability’ (Lander Citation2017, p. 12). As a result, the foreign investors clashed with the regional authorities, especially over cultural understandings of land ownership.

As with Lander’s (Citation2017) research, a recurring theme highlighted in this article by the interviewees and corporate documentation was that regional governments were keen for the ‘flagships’ to maintain, or invest in, livestock or milk production assets: ‘the biggest part that we always have to deal with is the animal husbandry; … for the [Russian and Ukrainian] politicians, of course, it is a big thing’.Footnote40 Interviewees felt that this diversification was a poor business strategy across both countries: ‘The livestock industry is a real loser … due to the high grain prices; … it never ma[kes] a profit, … and you’re just losing money on that’.Footnote41 One interviewee explained that ‘it’s widely known that we [BEF] don’t like beef and dairy, [and] there’s been quite a lot of [Russian] government pressure on us to do that [invest in beef and dairy]’, and that developing a sector based on ‘self-sufficiency [as the Russian government wanted] rather than competitive advantage’ was challenging. The interviewee continued:

Now, for me, with a Western background—free-trade economics—that doesn’t sound too clever. One of the issues it throws up is that the Russian government is trying to encourage investment in things that you don’t have a competitor advantage in. We can’t grow a lot of grass over here compared with New Zealand, and South America, which is why it’s not easy for Russia to have global competitor advantage in beef and dairy … . I don’t think that’s too wise as a federal strategy.Footnote42

It is important to note that the example of Agromino’s greenfield milk operation near St Petersburg shows that there is some potential for milk production in Russia near the major cities. An Agromino representative stated during a conference call in 2012 that milk production near St Petersburg and in Estonia was ‘consistently and increasingly profitable’ (Trigon Agri Citation2012). Nevertheless, the company identified its milk operations in Russia and Estonia as ‘non-core’ (Trigon Agri Citation2013, pp. 5, 10). Also, Agromino was referring to the potential of new, expensive greenfield milk production operations in close proximity to cities, not to the maintenance of existing—and in many cases unproductive—herds accumulated through the purchase of land, which was often the focus of regional governmental pressure.

Navigating geopolitical crisis

In November 2013, the then president of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych, refused to sign an association agreement with the EU, which set in motion a complex chain of events: significant protests in Ukraine; Yanukovych’s eventual exile in Russia; the installation of a pro-EU government in Kyiv; the reinforcement of Russian troops in Crimea to enforce a snap election that led to the absorption of Crimea into the Russian Federation; and, finally, a weaponised conflict in eastern Ukraine between Russian and Ukrainian forces.

Following the annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the United States, European Union and other Western countries imposed economic sanctions on Russia, targeting the ‘energy, banking, and defence sectors’ (Liefert & Liefert Citation2015, p. 508); Russia responded by issuing import bans on food and agricultural goods on 7 August 2014 (dairy, most meat products, fruit and vegetables, fish products), targeting imports originating from the EU, US, Norway, Canada and Australia (Kutlina-Dimitrova Citation2015, p. 2). The ban was originally imposed for one year, initially affecting EU exports totalling €5.2 billion (Kutlina-Dimitrova Citation2015, p. 4), but has been extended and is now set to end on 31 December 2020 (European Commission Citation2020). As a result of the geopolitical turmoil, Russia suffered ‘falling oil prices, … recession, active involvement in various geo-political conflicts and overall deteriorating trade relations’ (Fedoseeva Citation2016, p. 11). The devaluation of the ruble was another consequence (Fedoseeva Citation2016; Meyers & Schroeder Citation2016; Shagaida Citation2016).

Ukraine also experienced severe economic effects as the hryvnia depreciated further than the ruble (Dabrowki Citation2016, pp. 312–13), becoming one of the worst performing currencies of 2015 (Bershidsky Citation2015). This prompted the Ukrainian Central Bank to institute capital controls to curb hard currency losses from the country (Serkin et al. Citation2015; Bizyaev et al. Citation2016). These controls have been relaxed somewhat over time, though their effects were still being felt in 2017: Agromino, for example, citing the strict currency controls, was forced to agree a credit facility with its new majority shareholders to ensure working capital for the 2017 agricultural season.Footnote49 Further, some Ukrainian agricultural producers were caught between expanded though ultimately still ungenerous (from a Ukrainian standpoint) agricultural quotas under the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement with Europe (DCFTA)—agreed as a part of the Association Agreement with the EU (Kramer Citation2016)—and the Russian import ban on Ukrainian agricultural produce implemented in 2015.Footnote50 Arable farm companies—including the ‘flagships’—that focus on international exports have been less affected by these simultaneous adjustments in trade regimes.

This article supports Wegren’s notion that ‘the food ban announced by President Putin in August 2014 flows from the 2010 food security doctrine … [and] also brings into focus the importance of food as a political weapon’ (Wegren Citation2015, p. 1). Petrick writes that as a response to Western sanctions, ‘it was not by accident that the Russian administration chose the agricultural sector as an arena for import restrictions, … [and that] self-sufficiency in food has become a key political goal of the Russian government’ (Petrick Citation2015, p. 1). The geopolitical turmoil with the West was ‘possibly welcome[d]’ by Russia, as it allowed for progress to be made on the 2010 Food Security Doctrine through a policy of import substitution (Petrick Citation2015, p. 1).

BEF reports contained an equal amount of optimism and concern regarding the crisis. When it broke, the company noted that international markets had remained ‘relatively bearish’ (BEF Citation2014a, p. 6), and that the crisis, coupled with ‘dry conditions in the US plains’ had increased international and domestic crop prices, to the benefit of the company (BEF Citation2014b, p. 1); however, the company later explained that it was facing a ‘challenging price environment’ (BEF Citation2015a), and that ‘risks and uncertainty factors … in the Company’s business environment’ were predicted to increase (BEF Citation2014c, p. 11). This was a consequence of Russia’s economic recession—itself a result of low oil prices, political tension and international sanctions—and the subsequent decline in Russia’s GDP (BEF Citation2017, p. 19), and the downgrading of its credit rating (BEF Citation2015c, p. 20). The depreciation of the ruble in 2014, however, was not necessarily a disadvantage for the ‘flagships’; for example, whilst BEF described how the depreciation had affected the value of its assets in hard currency terms (BEF Citation2015b, p. 8), the company declared in 2015 that the weaker ruble contributed to making the company ‘more operationally competitive’ (BEF Citation2016, p. 8).

Ultimately, during the crisis, BEF’s reports indicated an inability to decide whether the crisis was a positive or negative development (BEF Citation2014a, Citation2015b). Whilst these reports recognised problems such as the company’s reduced access to credit for agricultural inputs from Russian state banks (BEF Citation2014a, p. 18; Citation2014d, p. 10), a more ‘difficult environment for investors’ in Russia (BEF Citation2014e), and ‘impact[s] … to free trade principles’ in Russia (BEF Citation2014a, p. 37), they also stated that Russian import bans would be ‘generally positive’ for the company ‘as import replacement drives demand for company products’ (BEF Citation2016, p. 40), and spoke of a ‘more favourable commercial environment in terms of our cost base’ that had convinced the company to alter its strategy by ‘preparing for a more rapid expansion of … [its] irrigation root crop enterprise’ (BEF Citation2015d). The indecision of the company is typified by such examples of describing Russian retaliation to international sanctions as having the potential to ‘affect the Company’s supply and marketing strategy both negatively and perhaps positively in the medium term’ (BEF Citation2014f, p. 3), and asking investors to ignore what the company called the ‘wider picture’: ‘If you just consider, in terms of the import ban and not the wider picture, [there are] potentially some positives in the medium term’ (BEF Citation2014d).

Unlike BEF, Agromino moved clearly from early optimism to later concerns, expressing at the outset that the ‘the Ukrainian situation’ was ‘a very positive development’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014a). There was, however, some initial apprehension surrounding the potential for conflict near the company’s large Kharkiv cluster. Whilst Agromino expressed uncertainty in its 2013 annual report (released in 2014) over the extent of Russia’s ambitions in Ukraine (Trigon Agri Citation2014b, p. 64), this was followed in 2014 by the confident declaration that company activities on the ground had not been affected by military operations in Ukraine (Trigon Agri Citation2014c, p. 2). This somewhat startling positive assessment was based on the depreciation of the hryvnia: as the company’s running costs were fixed in the hryvnia, costs were anticipated to drop in dollar or euro terms, as were the legal costs of fighting authorities who had been imposing ‘made-up taxes’ on businesses in Ukraine (Trigon Agri Citation2014a). More importantly, a ‘more transparent form of governance’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014a), and the expected result of the association agreement with the EU, were seen as positive developments for the company: ‘an association treaty with the EU would … be highly beneficial to the Ukrainian agricultural and food processing industries and could have a significantly positive impact on the general price environment for soft commodities in Ukraine’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014a). The company believed that there was a ‘strong probability … [that the crisis would] lead to a better business environment than the one … [it] had to operate in during recent years’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014d, p. 2). A 2014 interim report stated that, as access to working capital for agricultural producers had been affected by the political, economic and financial situation, this ‘should be [considered a] positive’, as the company had already secured its working capital for the 2015 season, and stood to benefit from ‘likely price developments’ across Russia and Ukraine (Trigon Agri Citation2015b, p. 2), expectations which, it should be said, ultimately did not pan out.Footnote51

Throughout 2014, though, Agromino reports increasingly showed more negative opinions. The company was concerned about the ‘impact on … [its] operations and financial position’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014d, p. 36), and the crisis was recognised as having a ‘negative effect on supplies and export’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014c, p. 20). Interestingly, at the beginning of 2014, Agromino stated that:

the sharp drop in the value of the Hrivna [sic] will not impact our operating results in a major way as our income is dollar denominated … [and] about a third of our operating expenses are paid in Hrivna [sic] but they are likely to adjust fairly rapidly towards pre-crisis dollar equivalent levels. (Trigon Agri Citation2014e, p. 2)

However, in its financial reporting for the fourth quarter, Agromino admitted to a net loss of €13.3 million (Trigon Agri Citation2015b). This net loss included ‘EUR 12.3 million of non-cash currency translation losses due to the dramatic depreciation of the Rouble [sic] and Hryvna [sic]’, that affected the value of its assets as stated in Euro (Trigon Agri Citation2015b, p. 2). Furthermore, Agromino reported that the ‘deterioration of the political and economic situation in Russia lead [sic] to losses in the amount of EUR 3.6 million’, a result of ‘receivable write offs, land revaluation loss’, and losses in the divestment of Penza that was sold below its expected valuation (Trigon Agri Citation2015b, p. 9).

Another financial impact for Agromino was that, for certain periods of time, it was unable to repatriate capital that had been invested in its Ukrainian subsidiaries due to temporary capital controls imposed by the Ukrainian government (Trigon Agri Citation2015c, p. 59). The company was also concerned that this risk could arise in Russia too (Trigon Agri Citation2014b, p. 62). The company stated that it was unable to sell some of its assets in Russia, in particular, the Pskov dairy operation, about which it had been in ‘detailed discussion’ during 2014, due to concerns about sanctions (Trigon Agri Citation2014c, p. 2). The company blamed the crisis for the ‘economic contraction … [that] made it extremely challenging to find buyers interested in the assets’ (Trigon Agri Citation2016, p. 2).

By 2015, the company had divested its Rostov cluster and stated that ‘the rapidly deteriorating economic and financial environment in both Ukraine and Russia had a material negative impact on the Company’ (Trigon Agri Citation2016, p. 2). During its third-quarter telephone conference, the company described how before the economic sanctions were imposed, the largest investment bank—a subsidiary of Sberbank, the largest Russian bank—had taken on the task of looking for investors for the Rostov land. Sberbank’s efforts had generated ‘significant interest … with one of the buyers’ coming close to an agreement; however, the ‘price levels … that Sberbank was working on were totally different’ to the price that Agromino eventually divested the asset for, and the company placed the blame for this change in price levels on the geopolitical crisis (Trigon Agri Citation2015a).

Agrokultura detailed the effects of the crisis in Crimea far less than the other two companies. Initially, Agrokultura stated that the crisis did not have ‘any material disruption to the Group’s operations’, although it admitted that the devaluation of the hryvnia ‘reduced the Group’s ability to draw down short term working capital bank debt’ (Agrokultura Citation2014a, p. 22). To overcome this issue of access to credit, the company moved to ‘reduc[e] planting and redeploy resources from other areas’ (Agrokultura Citation2014a, p. 22), the latter of which meant securing both a ‘$12 million of short term working capital loan’ and ‘shareholder loans’ (Agrokultura Citation2015, pp. 19–20). Despite this need for short-term capital, the company stated that the ‘currency weakness in Ukraine and Russia [was] generally positive for operations despite increased financing rates’ (Agrokultura Citation2015, p. 2). Agrokultura also, at one point, controlled land in Crimea, but disposed of this in 2013 before the crisis started (Agrokultura Citation2014b, p. 20); during 2013, the company was looking to sell the ‘entire business for a sum in excess of book value but political events put those discussions on hold prior to completion’ (Agrokultura Citation2014a, p. 2).

Despite the mixed opinions contained within the reports, the interviewees focused solely on the negative impacts of the crisis. One BEF interviewee explained how, prior to Crimea, ‘Russia had a bad press’, but that this had changed with the increase in political risk.Footnote52 This reflected the company’s 2014 concerns over the depreciation of the ruble—‘we immediately have a problem there’—but the interviewee did state that it could ‘long term, make the company more competitive, because a lot of international commodities re-price straight away’, although ‘not all of the contracts work[ed] like that’.Footnote53 The company changed its financial strategy in an attempt to minimise this risk and ‘began converting a lot of rubles into hard currency because we felt the downside was so big’.Footnote54 Also, concern was expressed at the ‘hopeless … steady slowing down of all processes’ surrounding credit access, as certain Russian banks were ‘almost frozen in terms of activity’.Footnote55 An interviewee from Agrokultura similarly reflected that ‘the war situation’ meant that the company had difficulty securing loans in Ukraine, in part due to the freezing up of the banking sector.Footnote56

Apprehension was also expressed by the interviewees, as ‘things start[ed] to weigh down’.Footnote57 Despite the 2013 BEF Annual Report stating that ‘Russia’s entry to the World Trade Organization could reduce the probability of trade distortions’ (BEF Citation2014a, p. 37), one of the company’s interviewees, prior to the report’s publication, declared, ‘Do I expect Russia to behave impeccably as a WTO member? No’.Footnote58 This anxiety continued to grow as interviewees admitted to panicking: ‘Then you might start to think, “What else might happen, might we get banking restrictions? Etcetera, etcetera”’.Footnote59

BEF embarked on a process of ‘financial repatriation’ after the eventual banking restrictions faced the company with the choice of keeping its capital in Russia or moving it to ‘Jersey or Cyprus’.Footnote60 This was a potentially sensitive topic as Russian President Vladimir Putin had previously targeted capital flight as a priority, although this political focus was more motivated by Russian corporate tax evasion as part of a ‘crackdown on corruption’ (Busvine Citation2012). According to a BEF interviewee, the company ‘moved quite a bit of cash out to protect … [its] own interests’, and admitted that this information was ‘not in the market’.Footnote61 This calls into question a methodological issue concerning the transparency of the corporate literature; although BEF can be, in many respects, praised for its transparency, the crisis forced the company to protect its own interests whilst projecting a calmer exterior, choosing not to include the information in its financial reports so as not to scare investors or draw negative attention from the media. This is not to say that the company was engaged in secretive behaviour; it would certainly have been surprising if the main shareholders were not informed, and the company would have had to follow Russian laws by reporting the repatriation to the relevant authorities. Nevertheless, the company’s behaviour was indicative of sufficient concern.

Whilst the risk disclosure statements in the company prospectuses do indicate some appreciation of the potential for political instability, it can be argued that the fully developed geopolitical crisis was not anticipated by the companies, as, indeed, it had not been by most European policymakers and other experts.

The sinking of the armada

As mentioned above, Agrokultura was bought by the sugar refiner, Prodimex, in 2014 (Kunle Citation2014). The founders of Agrokultura, Björn Lindström and Peter Geijerman, had expressed unhappiness with the company’s performance as far back as September 2013 and, indeed, had called for the liquidation of the business, with Lindström stating:

if we can’t get a profit from the company’s assets today that are the basis for a stock market value which is around the book-keeping value of our own capital, then we think that it is obvious that that [liquidation] is the best option.Footnote62

In answering the question of why these companies divested—either completely from Russia and Ukraine in the cases of Agrokultura and BEF, and from Russia alone in the case of Agromino—attention must be paid to both internal and external factors that have collectively affected the companies, and the extent to which these factors have hampered company success, or influenced their decision to exit from the market. Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 200) posed the question, ‘Why have these investments not been more successful?’, and drew attention to internal factors. Following a developing literature detailing a mismatch between financial investment and the agricultural sector (see Magnan Citation2015), reasons for the discordant performance included a ‘lack of balance and synergy between land speculation and production strategies’ (as discussed above through the movement from ‘asset-play’ to ‘yield-play’) and a scaling-up of operations that moved too quickly, all guided by pressurised investor short-termism that demanded quick returns on investments (Kuns et al. Citation2016, pp. 200–13). Investors in these three companies, working on the basis of short-time horizons, thus had the option of divesting from their share ownership once the companies showed signs of operational and financial struggles. Many investors did exactly that when, in 2008, plummeting grain prices negatively affected prospects for an appreciation in land values (Kuns et al. Citation2016, pp. 205–8).

Beyond crushed expectations of appreciation in land values, the media has commented on the financial losses that the companies made through their ventures. In 2013, the Swedish business newspaper, Dagens industri pointed out that ‘Kinnevik ha[d] ploughed in 790 million kr in the Russian soil’, resulting in a loss of ‘about half a billion kr if one compares to the value of Kinnevik’s shares in BEF’ (Leijonhufvud Citation2013). Furthermore, the BEF chairman, Per Åhlgren, had commented on unforeseen financial losses: ‘one day of pouring rain meant that we lost US$8 million. It’s then that one starts to wonder if there are not better ways to make money’ (Lindstedt Citation2017). In the end, Kinnevek lost over SEK 400 million (approximately $45.3 million) through the sale of BEF in 2017, with Alecta Försäkring, a large Swedish insurance company, also losing SEK 200 million (approximately $22.7 million) (Lindstedt Citation2017). Investors who divested earlier tended to break even, though they too expressed disappointment at the gains that never appeared (Lindstedt Citation2017).

The question, then, concerns to what extent the external factors—discussed in this article—entail cost implications, and whether they were exacerbating forces on the three companies’ decisions to divest; that is not to say, though, that these factors were the only reasons behind the decisions to exit the markets. The interviews with the consultants sometimes pointed to much simpler reasoning behind the divestments: poor yields were to blame; the companies ‘had an attitude of, and were hoping for, that it could be easy … and it didn’t work out that way’;Footnote63 and the companies were too reliant on the belief that more money invested into management teams would create better results.Footnote64 In line with our research, the consultants who were interviewed as part of this research were firm in their belief that the companies ‘were, in many cases, not prepared to deal with … [the perceived] post-Soviet mentality’.Footnote65 Certainly, as detailed above, the companies were often reactive in their response to the formal and informal corruption environments; there were apparent oversights in the companies’ expectations, with inadequate preventative measures from the outset. These errors of judgment, ultimately, had cost implications for the companies.

As discussed above, Lindstedt (Citation2008, p. 64) reported how BEF’s investors were expecting problematic interactions with the Russia mafia. This indicates a focus on highly organised, formal forms of corruption—a popular view of post-Soviet corruption—and inadequate consideration of the everyday, informal manifestations of corruption that can be more difficult to identify and resolve. Indeed, this was reflected in the corporate prospectuses of the companies (issued before stock listing): all briefly mentioned, in generic terms, ‘crime and corruption’, but none referred to internal theft, nor ways to manage or prevent the risks that had been identified (BEF Citation2007, p. 4; Trigon Agri Citation2007, p. 18; Alpcot Agro Citation2009, p. 9). Moreover, the companies’ generic approach to considering these risk factors is very clear through the cross-company regurgitation of exactly the same (or very similar) passages. To give the example of Agrokultura and Black Earth Farming: ‘It is important to call attention to the fact that the Company operates in an environment subject to corruption, where government officials at all levels often have interests which collide with their role as government officials’.Footnote66 In reality, however, interviewees stated that they had not dealt with the mafia, with a BEF interviewee explaining that, at most, the company had only experienced ‘semi-criminal groups’.Footnote67 Meanwhile, the issue of theft seemed to take the companies by surprise, and steps were only taken to tackle the problem once the implications became tangible. Further, the companies did not seem prepared to deal with, what one interviewee called, the ‘time-consuming process’ of using the judicial system as this represented ‘time you start to waste when you should be working on the business’.Footnote68

It is impossible to quantify the full extent that corruption had on the business costs of the three companies, and to what degree it affected their profits. BEF had, apparently, ‘only’ spent over a million dollars in legal fees fighting corruption,Footnote69 an amount that does not seem operationally significant, relative to the large quantities of money that the companies have lost in total. The financial implications of theft, however, are clouded by the fact that matters of theft and corruption were rarely commented on in corporate documents. However, the Swedish business magazine, Affärsvärlden, tells of how BEF allocated a great deal of resources on ‘monitoring and security’ in attempts to protect its ‘expensive foreign made machines … [that were] worth millions’ (Lindstedt Citation2017). As discussed above, this notion is also supported by the interviewees of this article, who indicated that theft, as well as being a loss in itself, led to losses in other areas; for example, the theft of fertilisers resulted in lower yields, a smaller harvest and, therefore, a reduced profit. Further, the comparison of theft to a drop in profits ‘from twenty percent … to maybe ten percent’, or to the creation of ‘a tax on [top of] the tax’ to the value of an additional ‘twenty five percent to thirty percent’, is also a clear divergence from the official corporate line.Footnote70 When one considers the cost implications of hiring security guards with dogs, building virtual ‘forts’,Footnote71 prosecuting thieves in court and employing—or, indeed, designing and developing—advanced technological GPS monitoring systems, then the scale of theft as an exacerbating factor can begin to be comprehended.

The role of interactions with regional government in the companies’ decisions to divest is also difficult to quantify; however, it would have undoubtedly increased pressure on the companies’ operations, especially, in the case of BEF, given the ‘very bad relation[s]’ it had with some local governmentsFootnote72 that developed as a result of resisting regional governmental pressure to diversify into bovine livestock production. As noted above, interviewees have made the costs of governmental pressure apparent—fines, impacts on the operations of the businesses and the legal fees involved in challenging the regional governments in court—and these costs would have affected overall corporate profits. In 2014, BEF re-balanced its holdings away from Voronezh ‘towards the northern part of its production area’, and although this had the appearance of moving from a ‘relatively drier’ region to one ‘where rainfall is somewhat better’ (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 211), the company’s poor relations with the Voronezh regional government cannot be ignored as a possible aggravating factor. It would be interesting to know the full extent of this factor in corporate decisions to divest, but as the companies do not detail disputes of this nature in their corporate material, nor, in most cases, break down costs by region in their financial statements, it, unfortunately, continues to remain a subject of conjecture and supposition.

Lastly, the role of the geopolitical crisis in the companies’ decisions to divest raises some interesting arguments. Whilst BEF officially seemed indecisive as to whether the crisis was positive or negative for the company’s business, and Agrokultura also expressed a mixed opinion, the distinct shift of Agromino from early optimism to later concerns is curious. By the time the company was in the advanced stages of divesting from its Russian operations, it was largely using the crisis as the ostensible reason; however, there is evidence that the real motivation may have stemmed from problems experienced by the company before the crisis. In fact, the company had been concerned about its indebtedness for some time: the 2013 fourth quarter telephone conference detailed the pressing need to resolve the ‘total debt burden’ of the company, at the same time stating that the crisis had ‘not impacted … [the company] so far’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014d, p. 3). Moreover, this telephone conference was held on 28 February 2014, just one day after soldiers in unmarked uniforms appeared in Crimea and, certainly, before the peak of the geopolitical turmoil. This debt burden had been caused by SEK350 million-worth of bonds with an annual interest rate of 11% (Trigon Agri Citation2016, p. 6) that the company had issued in 2011 to aid in its ‘asset-play’ land accumulation strategy and had been unable to pay back, due to its disappointing corporate performance and poor farmland values in Russia (Verdin Citation2017).

The company’s 2013 annual report stated that ‘covenants [we]re attached to the bonds … [requiring] that the ratio of financial indebtedness to shareholders’ equity will never exceed 75%’; as of 31 December 2013, however, it was ‘71%’ (Trigon Agri Citation2014b, pp. 61, 64). The report, released on 31 March 2014, declared that if the situation in Ukraine worsened, then the company could be pushed beyond this 75% threshold and made to repay the bond early, which would set off ‘a fire sale of non-core assets’ and, if necessary, core assets (Trigon Agri Citation2014b, p. 64). Ultimately, Agromino was able to renegotiate with the bondholders to extend the maturity of the bonds from 2015 to 2017 in order to give it time to sell assets,Footnote73 and Agromino’s corporate reports from 2014 began discussing the effect of the crisis on its operations in much more detail than the other companies. The question, thus, needs to be asked if Agromino was attempting to deflect attention from operational mistakes made before the crisis. This is an interesting issue, as it questions how much blame can be placed on the crisis; after all, the company was already operating close to the 75% level of financial indebtedness to shareholder’s equity before the crisis unfolded. In the end, the company did exceed the 75% limit, confirming this in its 2014 Annual Report (Trigon Agri Citation2015c, p. 55), and so the crisis can only likely be considered an exacerbating factor.

For Agromino, ultimately, speculation was left to the media. The company was named by the Swedish agricultural newspaper, ATL, as the only company divesting from Russia as a result of the crisis and its economic effects: ‘Swedish listed company disposes of 154,000 hectares of arable land … following Russia’s annexation of Crimea almost two years ago’ (Nilsson Citation2016). The company sold its Rostov cluster in late 2015 (Kunle & Skrynnik Citation2015), but made a large loss, and was not able to pay the bond holders in full; as a result, the bond holders were given a stake in the company, becoming major shareholders (Trigon Agri Citation2017, p. 3). The chairman of the board, Joachim Helenius, considered the founder, was replaced;Footnote74 and Trigon Capital sold off all shares in the company, coincidentally triggering the company’s rebranding from Trigon Agri to Agromino. As noted above, the management turmoil continued, with the then-new 2016 management being replaced in 2018 (Agromino Citation2018a). With new managers, and a continuing effort to improve performance, Agromino may yet become consistently profitable in the future, though, as discussed above, as a privately held company.

Conclusions

Building on previous work on internal factors by Kuns et al. (Citation2016), this article has discussed the impact of three external factors on the performance, and the decisions to divest, of three foreign ‘flagship’ agroholdings in Russia and Ukraine: corruption and theft, regional governmental pressure, and the crisis surrounding Russia’s annexation of Crimea. As has been shown, navigating the operating environment had been challenging for the companies, and whilst it is difficult to reveal the exact impact of the external factors in terms of cost implications, nevertheless, the corporate literature and interviews have revealed that they were significant. Some of these external factors were beyond prediction, such as the geopolitical crisis and resulting economic turbulence; yet, companies were also guilty of oversight in certain areas, especially concerning regional governmental interactions, theft and the well-documented pervasiveness of blat behaviour. That aside, the companies did demonstrate that they were able to adapt to these problems—for instance by using domestic legal systems and developing GPS monitoring technology—however, this adaptation came too late to save the companies from their financial and operational struggles.

In this respect, the context matters: for investors, misjudging or ignoring the local context comes with its own perilous consequences. In line with the results of Kuns et al. (Citation2016), who demonstrated how ignorance, or downplaying, of the local agro-ecological context hurt these same companies, this article has detailed the difficult navigation of the ‘flagships’ through the socio-political environment of Russia and Ukraine. Whilst more research is needed to ascertain why some agroholdings were successful, it is noted above that many of the more successful agroholdings are locally owned and managed, rather than being foreign in origin. The question, therefore, is posed as to whether local ownership and management allows a company to avoid, be better equipped for, or even nullify the challenges of the local operating environment.

This article has shown that the geopolitical crisis did have an effect on the companies, and resulted in, amongst other events, a challenging price environment, currency depreciation that affected the value of assets, currency translation losses, difficulty in repatriating capital, credit access issues, the reduced expansion potential of operations, lowered buyer interest in company assets that affected companies’ consolidation strategies and financial losses. Despite the balancing of these negative consequences against more positive sentiments in the corporate statements, the ‘flagship’ company interviewees focused solely on negative concerns and displayed a higher level of anxiety. This is important to consider, as it shows variance between the experienced ‘reality’ of the operating environment and the official corporate line that companies conveyed to their investors and shareholders; certainly, it is a point that other areas of academia relying heavily on corporate documents as a main source of primary empirical material should consider.

The performance problems that the companies experienced had their roots in issues that pre-dated the crisis, with Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 200) detailing the significant losses that the companies had made since their investment in Russia and Ukraine. It is for this reason that the role of the crisis in the divestment decisions of the companies should be considered in context; indeed, it was only with respect to Agromino that there was the suggestion that the crisis was a factor in its decision to divest.

Following from this, it is important to consider the methodological implications of using corporate literature for research. The transparency that the companies displayed in revealing their documents and audio recordings online, and through employees meeting for interviews, can be praised; however, this transparency obviously has its limits. Whilst it is legitimate for the companies—given the tense geopolitical situation—to try to make the best of the crisis situation in their public statements, on the other hand, this public face was, to a certain extent, a façade, as the interviewees were quite clearly concerned by events. With the effects of theft on the performance of the companies, again, this was officially downplayed, but struggled with behind the scenes. Ironically, even whilst downplaying the effects of corruption and theft in the corporate literature, the companies have displayed a willingness to fight for the rule of law in Russia, often spending considerable financial and time resources. BEF’s court case win, discussed above, is notable, and shows—at least in business disputes—that the Russian legal system can work; thus, although Russia is a tough environment to operate in, it is not impossible. For effective research, though, corporate documents can only go so far, and this article has highlighted the existence of ‘sources of error and discursive blind spots’ (Kuns et al. Citation2016, p. 202).

Another observation is that all the companies have divested from Russia, with only Agromino continuing to operate in Ukraine. In this regard, while Agromino has only achieved net profitability four times over the last 13 years (2006–2019), its annual reports show consistently better agricultural performance—in terms of financial metrics—in its Ukrainian clusters compared to its Russian clusters.Footnote75 Amongst other reasons, this is probably a result of Ukraine’s more favourable agricultural conditions compared to Russia. It is, in any case, noted that the most consistently profitable public arable farming agroholdings are located in Ukraine (Kuns et al. Citation2016). Beyond agricultural conditions, this may also reflect the regulatory environment, as Ukraine’s soon-to-end prohibition (Sorokin Citation2020) on the sale of agricultural land has forced investors to pursue production-oriented strategies, as opposed to strategies orientated towards land speculation (Kuns et al. Citation2016).

Through the sales of Agrokultura to Prodimex, BEF to Volgo-DonSelkhozInvest, and the divestment of Agromino’s Russian assets to Ellania Business Inc., Russian assets that were once owned by foreign investors have now re-entered Russian hands. These Russian buyers have inherited not only agroholdings that are largely operational and now consolidated into operative clusters, but assets of machinery, irrigation and a trained labour force. Though these agroholdings may not be profitable, they were in the process of improving (Kuns & Visser Citation2016), and their assets were purchased at a cheap price; in the cases of BEF and Agromino, this low price was further dampened by the crisis and the economic recession. As such, the return of these lands to Russian companies would appear to aid the Putin administration’s desire for self-sufficiency in food production.

The foreign companies resisted advances from regional governments and used the legal system to challenge—as well as flatly refuse—the perceived exerted pressure and control. As there appears to be a historico-cultural aspect to the behaviour of the regional governments, then Russian ownership of the agroholdings may dissolve that apparent ‘cultural clash’ and make it easier for the government to achieve its aims. However, for these clashes to end, then they do, indeed, have to have been cultural in nature; the livestock sector was identified as a ‘real loser’ in terms of financeFootnote76 and challenging to run on ‘self-sufficiency rather than competitor advantage’,Footnote77 and it is not certain that Russian business would agree with a loss-making project just to appease regional government. Likewise, it is not certain that Russian ownership of the agroholdings will necessarily bring about a large change in fortunes on the operational and financial side; this is an area of research that must continue, and that will help frame the failures of the foreign ventures within the larger picture.

What is clear from this research is that this armada of foreign ‘flagship’ agroholdings—due to a combination of internal (Kuns et al. Citation2016) and external complicating factors have, essentially, sunk in their maiden voyage to the post-Soviet region. Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 213) explain the problem as ‘how investors relate to agronomical best practices and their naïve belief that it can be deployed all over the world’; this article seeks to add to that by indicating a further problem in the way that foreign investors viewed the ‘new world’ of the post-Soviet space, especially Russia. The companies misjudged the operating environment in certain respects, and the culmination of the internal and external burdens did much to hamper their progress. Potential problems were considered only in stereotyped terms, such as taking into account only highly organised, formal corruption, whilst actual problems were not sufficiently anticipated. Why this was the case is difficult to discern; possibly, as Kuns et al. (Citation2016, p. 208) report, due to the lack of non-executives with agricultural experience initially present in each company’s boardroom.