Abstract

It is no secret that the modernisation process in Russia via state-owned companies has run into a dead end. A full understanding of this stagnation requires an investigation of the governance systems and the changes going on behind them. Using the example of the two most important state-owned companies of the aviation sector, the JSC United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) and the non-profit organisation (state corporation—Gosudarstvennaya Korporatsiya) Rostec, this article shows the main differences in state corporate governance systems, identifying a presidential and a governmental governance system. In the context of this work, the term governmental is limited only to the federal cabinet and its administrations, thereby creating an awareness that different executive state bodies can exercise different forms of state governance. Overall, the sector is characterised by growing informalisation and industrial incorporation.

Are the attempts of Russia to modernise its economy through qualitative growth and ensure global competitiveness running into a dead end? The economy seems to be stuck in long-term stagnation and the Global Innovation Index shows a continuous decline in the country’s innovative capability.Footnote1

Under Putin’s state capitalism, the responsibility for modernisation has, over the last 15 years, been in the hands of organisations that the Russian media often calls ‘state corporations’ (Gosudarstvennaya Korporatsiya). In the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the vertical governance mechanisms of the centrally administered economy, most assets were transferred to private companies. At the same time, comparative cost and price systems were reversed and innovation and value chains disintegrated. A sharp decline in the output of the manufacturing sector, in particular its high-tech branches, was the result. When calls for diversification and modernisation of the Russian economy became louder in 2008, the Kremlin moved the issue to the top of the political agenda, as seen in its launch of ‘Strategy 2020’, the manifesto ‘Go Russia’ and, later, the concept of ‘Russia’s 4th industrial revolution’ (4IR). Thereby, state and state-owned companies were to play a leading role. State integration of enterprises along innovation and value chains is easy to comprehend, especially after the experiences during the 1990s. Over time, however, it became apparent that state companies were hardly capable of implementing these federally mandated modernisation concepts.

Against this background, it is all the more surprising to observe a constant process of concentration in which state enterprises are merged into ever greater conglomerates. In 2018, the aviation conglomerate United Aircraft Corporation (Ob’edinennaya Aviastroitel’naya Korporatsiya—UAC) was integrated into the state corporation Rostec (State Corporation for Assistance to Development, Production and Export of Advanced Technology Industrial Product; Gosudarstvennaya korporatsiya po sodeistviyu razrabotke, proizvodstvu i eksportu vysokotekhnologichnoi promyshlennoy produktsii ‘Rostekh’).Footnote2 This step was celebrated by the media as the formation of a ‘Russian Airbus PLC’ and as heralding the rebirth of the Russian aerospace industry.Footnote3 In fact, this rebirth had already been announced 12 years previously, with the founding of UAC. Today Rostec comprises hundreds of companies from the defence, engineering and pharmaceutical industries. In terms of size, it overshadows not only Airbus, Boeing and large multinational groups such as General Electric and Samsung but also the Soviet-era Ministry of Medium Machine Building (Ministerstvo srednogo mashinostroeniya). Interestingly, while the Russian media customarily uses the term state corporation to refer to all state-owned companies, Rostec is one of the ‘real’ state corporations according to the federal law, forming a new type of state-owned company. Like all companies in the legal form of a state corporation, Rostec is a non-profit organisation (NPO) based on the Federal Law No. 7 ‘On Non-Profit Organisations’Footnote4 and its amendments. Each state corporation is created by a separate federal law with the character of ‘bespoke legislation’, tailoring the rules of the legal framework to its specific needs. The state corporations differ from other state-owned companies regarding their regulations and requirements (for example, in the context of transparency and disclosure, bankruptcy or procurement procedures). The extent to which these regulations influence state corporate governance is the subject of this article.

A closer look at the similarities and differences between state-owned companies and their formal and informal regulations is needed. What form of state corporate governance has emerged in recent years? Why are some state corporations constantly growing while others fail? Above all, how efficient are different state-owned companies and how do they influence the modernisation process? In other words, is state-led modernisation predisposed to stagnation?

This article approaches these questions empirically by concentrating on the aircraft industry, one of Russia’s leading high-tech, globally competitive industries. On the basis of case studies, I compare the two most important state corporations in the sector, looking at their differences and the impact they have on the implementation of the state mandated modernisation targets. I then focus on how state corporate governance influences the behaviour of state and corporate actors through incentives and sanctions. For a more complete picture of the incentives and sanction constellation, the article suggests that, along with formal factors such as the legal framework and ownership structure, informal factors should also be considered. This is all the more important as informal interactions have always determined the social behaviour of Russian society substantially (Grossmann Citation1977; Willerton Citation1992; Kononenko & Moshes Citation2011; Ledeneva & Barsukova Citation2018). Informal institutions should hence not be understood as a peripheral phenomenon but as a basic component of social behaviour and can be understood as a methodological tool. The article sheds light on the question of the role played by personal networks in the process and how they work. Because of the ambivalent characteristicsFootnote5 of such networks (Ledeneva Citation2004, Citation2013; Krome Citation2015), a closer look at their effects is advisable.

The article presents the hypothesis that the informal incentive and sanction systems develop anti-modern, adverse dynamics in the medium-to-long term, and that they dominate formal interaction systems, thus undermining official modernisation targets.

When determining the key factors of successful state corporate governance, it has to be acknowledged that the literature is rather sparse, especially for the Russian aircraft industry. A comprehensive overview of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in regard to their legal characteristics and governance problems is given by Sprenger (Citation2010). Important scholarly contributions have also been made in the context of mixed public–private ownership, looking at state minority or majority stakes in relation to a corporation’s performance (Grosman et al. Citation2016; Grosman & Leiponen Citation2018). Although state ownership is an important criterion, it is necessary to look beyond the formal factors at indirect forms of state control, such as state officials in board positions and shareholding structures within conglomerates, as discussed in Iwasaki (Citation2008), Frye and Iwasaki (Citation2011), Abramov et al. (Citation2017), and more informal mechanisms of state control (Chernykh Citation2008; Yakovlev Citation2009; Radygin et al. Citation2015; Abramov et al. Citation2017; Grosman & Leiponen Citation2018). There is a consensus that while a quantitative criterion of corporate ownership may suggest a decrease of state influence, since 2008 the qualitative influence of the state has been increasing, as apparent in its expansion of control over economic agents and in new areas of state regulation. State involvement in corporate structures is judged positively in the short term for a more systematic strategic approach and financial support, but rather critically in reference to market capitalisation and productivity (Abramov et al. Citation2017). Fundamental problems are a lack of transparency, low external control and adverse incentives (Sprenger Citation2010; Radygin et al. Citation2015).

Concerning informal factors and their impact on state corporate governance, important findings have been made in the context of Russia’s authoritarian post-Soviet regime and its top-down governance. While analysing factors exacerbating the implementation of reforms, the focus has been on informal elements such as rent-seeking, principal–agent problems, rivalry between subgroups and manual control within the power vertical. Following the academic discussion, the most crucial characteristics for successful implementation revolve around the ‘ability to act’ (Gel’man & Starodubtsev Citation2016; Libman & Burkhardt Citation2018; Treisman Citation2018) and ‘target orientation’ (Helmke & Levitsky Citation2004; Ledeneva Citation2013; Sakwa Citation2015, Citation2020; Libman & Burkhardt Citation2018; Treisman Citation2018) of the relevant players. Although these studies focus on the political processes of vertical state governance of regional territories rather than on corporate governance and economic performance, the criteria can be adapted to study state corporate governance. Therefore, I compare the two state-owned corporations in terms of their ability to act and their target orientation.

In doing so, I first draw up a list of formal and informal factors influencing the ability to act and the target orientation. After considering the specific challenges of the industry, I analyse two state-owned corporations using the above factors. I then look at the similarities and differences of the formal and informal interaction systems and their impact on incentives and sanction stimuli. In the last part, I compare forms of state corporate governance, while answering the question of why one corporation dominates and what this means for the modernisation process.

Ability to act, target congruency and factors of influence

Following the academic discussions on state governance, the ability to act (Gel’man Citation2016; Treisman Citation2018) and target orientation (Ledeneva Citation2013; Sakwa Citation2015; Libman & Vasileva Citation2018; Treisman Citation2018) are among the key criteria for the successful implementation of state modernisation projects. With regard to sectoral governance systems and state corporations, it is necessary to determine the factors which influence these two criteria. Therefore, we will look at the different formal and informal features and the incentive and sanction stimuli they induce. Informal network systems can support or subvert formal institutions.

Ability to act

The article analyses how a state-owned company acts, and how efficiently and effectively it can follow its goals. In Russia the level of autarchy plays a decisive role in determining the ability to act, and this applies not only to political agencies (Gel’man Citation2016) but also to economic organisations like state-owned companies. Autarchy can be high, low or moderate. A corporation’s level of autarchy corresponds to its access to resources as well as the extent to which it is influenced by state agencies (like the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service or sectoral ministries, Account Chambers) and other interest groups. The ability to act is determined by formal features of the legal form of state companies. SOEs, for example, can exist as public or closed joint stock companies; they can have a state minority or majority shareholding. State corporations generally belong to the Russian state completely. The legal form of state companies affects transparency and disclosure requirements, but also to whom the management of the corporation is accountable. Whether the management is responsible to public shareholders or state agencies can have a bearing on corporate governance; the same is true regarding the applicability of the law on bankruptcy, which varies depending on the legal form of SOEs. At the core of the discussion on corporate governance in Russian state corporations are also indirect factors like the number of state officials on company boards or requirements for the presence of independent directors, as these influence decision-making processes and the formation of majorities. Thereby state control can be strengthened or mitigated (Iwasaki Citation2008; Frye & Iwasaki Citation2011).

Formal autarchy can be supported or subverted by informal factors such as personal networks. The impact of networks depends on their power and competences, which are determined not so much by the network’s size as by its diversification (meaning the scope of representation of network members in different institutions and the influence they have there). Besides the position of network members within the company as members of the board of directors (BOD) and the board of management (BOM), it is their external relations to financial, administrative and political institutions or the security services that can influence a state corporation’s ability to act. In analysing forms of state corporate governance this article will concentrate on the interaction between state agencies and corporations.

In general, strong personal relations between network members with representatives within state bodies can improve a company’s access to resources and reduce external corporate control by official bodies (with regard to auditing, for example) as well as offset market competition (Manozzi et al. Citation2012); all those factors thus extend the ability to act. The informal use of administrative resources to influence decision-making processes is often discussed in the context of state capture (Yakovlev & Zhuravskaya Citation2006). The last two decades have shed more light on hidden forms of business capture. Increasingly, de jure independent private corporations are often de facto state-controlled enterprises (Radygin et al. Citation2015; Abramov et al. Citation2017). Therefore, to judge the level of autarchy critically, it is essential to also look at the informal power symmetry in the state–SOE relationship and analyse whether bottom-up or top-down influence mechanisms dominate (Libman & Burkhardt Citation2018). Given the nature of informality, gaining insight into informal hierarchical linkages is rather difficult and will be based on career progression data. Personal relational factors will be restricted to obvious personal interactions, such as family relationships or long-term friendships. Sometimes it is possible to retrace non-professional relations on the basis of mutual support of appointments to important positions in companies or authorities, or joint lobbying on behalf of business projects.

Beside autarchy, the degree of fragmentation within and between institutions (inter- and intra-institutional fragmentation) can seriously influence a company’s ability to act (Sakwa Citation2015, Citation2020; Gel’man & Starodubtsev Citation2016). An examination of factors such as board composition, as well as the organisation of industrial integration or administrative subordination to one or more state agencies, can help to locate the dividing lines along which subgroups may develop. To moderate different interests, formal coordination procedures play a crucial role. As these regulations are considered weak by state corporation management (Radygin et al. Citation2015), informal network systems play a crucial role: they can support formal structures or further deepen conflicts and thus subvert formal institutions.

The impact of personal networks will depend on the position its members hold within the corporation and their external connections, and also on the network’s own capacity to act. It can be assumed that the more divided a network, the less capable it is of acting. The article therefore investigates the centrality of personal networks (Granovetter Citation1973; Burt Citation1992) and relational factors such as trust, loyalty and clear rules of interaction (Ledeneva Citation2004).

In the end, whether a well-connected network with the ability to act will support the efficiency and effectiveness of a given corporation depends on the network’s target orientation. As there is no academic consensus on whether the main focus of state organisations is the implementation of official targets, the containment of social consequences (Treisman Citation2018) or private rent-seeking (Ledeneva Citation1998, Citation2013; Sakwa Citation2015; Gel’man & Starodubtsev Citation2016; Libman & Burkhardt Citation2018), we have to acknowledge that formal targets and informal private interests may diverge.

Target congruency

Target congruency describes the extent to which the private goals of the key players overlap with the official modernisation targets. Whether target congruency is low or high depends on the degree to which actors can benefit from following the official targets set in the modernisation programmes like the development and production of new engines or civil aircraft variants in comparison with the possibilities for generating rents on top of those targets. It can be assumed that the more difficult the implementation of formal tasks and the lower the chances of punishment, the higher the likelihood that players will pursue informal interests. Therefore, a closer look at the incentive and sanction interplay of formal and informal frameworks is helpful.

Beside the technical feasibility of developing new aviation technology, I consider the economic scope of action and the extent of political support for certain modernisation projects by different political actors, looking at their hierarchical position and competences. Having informal, personal contacts to relevant state authorities can also be seen as a supportive incentive. However, owing to the ambiguous character of informal networks (Ledeneva Citation2013), such connections can lead from target congruency to target conflict when experience shows that competitive advantages can be achieved more easily through network ties than through more innovative products or lower production costs. While economic factors can be accessed through annual reports, in order to judge the political and administrative potential of networks, the article examines whether network members sit in relevant state agencies and to what extent they can influence decision-making processes.

Influence on target congruency can be exerted through the informal rewards systems. Besides non-material incentives, such as social recognition and a sense of cultural belonging (Ledeneva Citation2013), networks often function on the basis of material rewards with high rent-granting, allowing for extortion and kickbacks, the diversion of cash flows through private channels and the siphoning of artificial trading margins (Osipian Citation2018). Informal incentives do not only emerge from active rent-granting but may also arise from hidden principal–agent problems inducing opportunistic behaviour, a characteristic that can increase as an organisation reaches a certain size.

To what extent non-compliance with the official targets can be contained also depends on sanction tools. The problem is that the formal legal system in Russia is considered weak (Ledeneva Citation2018). Furthermore, legal sanctions can be circumvented by using informal relations with relevant agencies; thus, punishments can be suspended and legal vacuums created (Ledeneva Citation1998). Informal sanction tools, on the contrary, can be quite powerful. Often, exclusion from networks, entailing the loss of network protection and access to privileges, is sufficient to keep members compliant with the network’s goals (Ledeneva Citation1998, Citation2013).

There is a danger that informal incentive and sanction stimuli are stronger than formal ones (Sakwa Citation2015, Citation2020), which highlights the importance of the target congruency of formal and informal goals. An imbalance in favour of informal stimuli is expected to increase with the omission of market mechanisms, sanctioning bad governance. Studies have shown that the threats of bankruptcy, takeover or market competition leave less room for private extraction (Guadalupe & Perez-Gonzalez Citation2010; Sprenger Citation2010). Differences in the legal form of the SOE may allow conclusions about the relevance of market control mechanisms.Footnote6

In the following, the state-owned enterprises will be compared on the basis of the elaborated factors influencing the ability to act and target congruency. Before doing so, I will discuss the formal modernisation targets and the challenges for the aviation industry.

The aviation industry: targets and challenges

From a macroeconomic point of view, the significance of this industry, comprising only around 100Footnote7 companies and 400,000 employees, is relatively small. It nevertheless plays an important role in the high-tech sector. Apart from space technology, aviation is the only high-tech sector in which Russia is internationally competitive. Expectations of modernisation are accordingly high. As declared by the federal target programmes for modernisation in the aviation industry for 2005–2015 and 2015–2025, Russia is to establish itself in line with the US and Europe as the third global centre for aviation. Accordingly, the civilian share of aviation technology should increase to over 50%.Footnote8 In order to reach these targets, the responsible actors have to deal with the particular challenges of the industry, as described below.

The first is the high armament orientation of the sector. Traditionally the aviation industry is responsible for at least 40–50% of Russia’s entire defence exports, oscillating around US$15 billion since 2012 (Malmlöf Citation2017).Footnote9 Accordingly, manufacturing military aircraft dominates the domestic aviation industry and makes up 70–80% of turnover. The demilitarisation of the industry overall is therefore among the most important goals of modernisation.

Second, as is well known, Russia has large technological potential, in particular, with regard to pure research. The challenges still lie in industrial application and the commercialisation of these technologies (Graham Citation2013).

Third, the aviation industry is characterised by long-term, capital-intensive and complex innovation-and-value-added processes compared to the extractive and close-to-the-market sectors such as agriculture, the petrochemical sector and parts of the IT industry.Footnote10 Accordingly, aviation companies require high financial support, long amortisation times and high sales numbers. Besides infrastructural issues, the size of the Russian market for aviation, which is very small in comparison to that of the US, China and the EU, is a problem.

The fourth challenge is that of integration into the global division of labour. From an economic point of view and also for technological reasons, access to global markets and integration into global value chains and know-how networks are crucial in order to generate and preserve competitive advantages. The international market for aviation is highly competitive and politicised; its penetration demands advanced management skills, international marketing expertise and in-depth knowledge of best international practices. As Russian management often lacks these skills, international cooperation is therefore seen as an important factor of success (Lozano & Eriksson Citation2015).

Fifth is the reorganisation of the division of labour and the coordination of companies along the value and innovation chain. For integration into the global market, a highly differentiated division of labour and high degree of specialisation within the sector is necessary. As a legacy of the Soviet Union, however, the division of labour among enterprises is less focused on specialising within separate value-added stages and more on different types of aircraft as a whole. Therefore, individual large enterprises usually operate a complete value-creation cycle of one aircraft model, beginning with metal processing down to the final assembly, with consequences for quality and manufacturing costs (Krome Citation2014).

After the collapse of the value-added-and-innovation systems in the 1990s, all these problems were supposed to be solved by state corporations. Yet, by the early 2000s it became apparent that state corporations were able to fulfil neither the structural tasks nor the modernisation demands of the federal target programmes. An examination of the two leading state corporations reveals why this has been the case, as well as the role played by formal and informal interaction systems. However, it should be noted that the efforts of these two state-owned companies to meet modernisation targets, in particular, the development of commercial aircraft, have been seriously hampered by Western sanctions (Sinergiev et al. Citation2019). Detailed research is needed to judge whether the sanctions are the source of problems in themselves or, rather, whether they have accelerated fundamental systemic problems (Yevtodyeva & Danilin Citation2018). In the framework of this article the focus is on the domestic and systemic challenges of the aviation industry.

Rostec: the presidential NPO model

High level of formal legal independence and economic autarchy

The state corporation Rostec under the leadership of CEO Sergey Chemezov, plays a central role in the governance of the aviation industry. The corporation was founded under Presidential Decree No. 270, dated 23 November 2007.Footnote11 Its growth figures suggest that Rostec has developed into a true national champion. Since 2015 the state corporation’s turnover has broken through the barrier of R1 trillion (US$19 billion) (Rostec Citation2015a). This growth mainly derives from the corporation’s arms exports, hovering around US$13 billion, thus making up nearly as much as 70% of Rostec’s revenue. This division is managed by the export agency Rosoboroneksport, which is part of Rostec. The agency handles a good 85% of the country’s military equipment exports, of which the aviation sector, with its fighter jets and helicopters, represents the majority share (Rostec Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2019a, Citation2019b).Footnote12 In the period 2007–2017, growth was mainly generated by government contracts. In 2017 these made up US$5–6 billion of Rostec’s revenue, which had thus tripled since Rostec’s foundation in 2007 (Rostec Citation2014; Simirnov Citation2017).Footnote13 During the same period, more than 300 large enterprises were integrated into Rostec.Footnote14

Looking at qualitative growth development, we can see a different picture. During the presidency of Dmitri Medvedev, the Accounting Chambers (Schetnaya Palata Rossiyskoi Federatsii) was twice commissioned to monitor the large state corporations. In its reports (2009 and 2014) the Chamber complained—along with their failure to meet the modernisation programme and their inefficient use of state funds—about the poor external oversight of state corporations by government agencies such as the Ministry of Justice, Tax and Customer Service, the Audit Chamber. This in particular applied to state corporations including Rostec (Safronov Citation2014), as government bodies are not entitled to interfere with the activities of the state corporations.Footnote15 An analysis of the formal and informal governance systems shows us why.

Formal governance systems

As of 2020 the state corporation Rostec comprised more than 800 of the most important enterprises in Russia’s medium- and high-tech industry (Rostec Citation2020b),Footnote16 mainly working for the military sector. These enterprises are managed by 14 subordinate industrial holdings.Footnote17 One of them deals with the aviation industry.

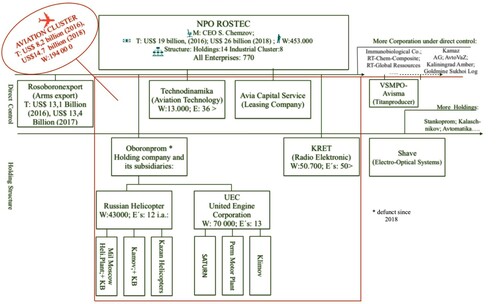

shows its organisational structures. The most important enterprises of the industry are grouped together as the Rostec Aviation Cluster. Among those companies are the helicopter holding Russian Helicopters (Vertolety Rossii), as well as the most important suppliers for aircraft manufacturing, such as the industry holding for jet engines, United Engine Corporation (Ob’edinennaya Dvigatelestroitel’naya Korporatsya—UEC), and the electronics manufacturer Kret.Footnote18

FIGURE 1. Holding Structures of the Rostec Aviation Cluster

Sources: Rostec (Citation2015a, Citation2016a, Citation2017).

Notes: M: management; T: turnover; W: workforce; E: entities (designers, manufacturers, joint ventures).

Rostec—using the ‘bespoke legislation’ of state corporations—has contributed to a creeping disempowerment of the relevant state bodies by simply withdrawing the leading conglomerates from governmental jurisdiction. In contrast to the industry holding UAC, Rostec was not founded as an open joint-stock company with a majority state share but was established as a non-profit organisation (NPO).Footnote19 According to Federal Law No. 270, paragraph 6, Rostec is under the direct administrative subordination of the president of the Russian Federation. The president has the right to determine the framework of the corporation’s powers. He appoints and dismisses the CEO of the state corporation and all members of the supervisory board.Footnote20

At the same time, the corporation is owned directly by the Russian Federation and therefore is not controlled by the federal governmental agency, Rosiumushchestvo, as other state corporations are. As an NPO, Rostec has to present an annual report but is subject to much lower disclosure requirements than state-owned joint stock companies. In particular, with regard to sources of funding and usage of resources, there remains—according to paragraphs 5 and 6 of the law—significant room for autonomy of action. It is a paradox that, according to Russian law, only NPOs such as Rostec (and also Rosatom, Roskosmos, VEB) are called state corporations. Regardless of whether they have NPO status or not, no distinction is made in public and all new state-owned companies are called state corporations.

Supportive informal interaction system

Since no formal institutional framework is strong enough to secure government control over state corporations, state governance relies on informal and personal ties between the representatives of large state corporations and the Kremlin. In the case of Rostec, this is the personal relationship between President Vladimir Putin and the Rostec CEO, Sergey Chemezov, who belongs to Putin’s inner circle (Bekbulatova Citation2016).Footnote21

Chemezov’s personal network: stable monocentric network

Chemezov oversees his extensive informal personal network system with stable monocentric characteristics. It is often built on strong personal relationships. These relationships are based on a high degree of loyalty and often have a patrimonial character, whereby the actors involved are in a relation of dependence to the head of Rostec due to long friendships, as well as usage of all kinds of favours, for example in the context of subcontracting, appointment to management position or protection from criminal prosecutions.

Groups of old friends

At the top are longstanding friends, many of whom go back to school days. These friends often exercise strategic functions within the corporation, companies of interest and relevant state institutions. Among them are Aleksei Federov, installed by Chemezov as UAC president from 2007 until 2011 (Safronov Citation2013), and Vitalii Mashchitsky, considered to be Chemezov’s personal financier, a childhood friend from Irkut (Bekbulatova Citation2016). In recent years he has been busy building up monopoly structures in the pharmaceutical sector for Rostec. Mashchitsky is the chairman of the Rostec subsidiary Nacimbo (Nacimbo Immunobiological Company) and holds shares in a number of pharmaceutical manufacturers (Sagdiev & Lyauv Citation2014). Mashchitsky maintains a very trusting relationship with Ilya Gubin, with whom he entrusted the governance of Novikombank. This bank specialises in dealings with the defence industry companies and Rostec projects. In 2016 the bank was integrated into Rostec structures. In the inner circle is Anatoliy Isaykin, who succeeded Chemezov as head of the state monopoly Rosoboroneksport in 2007 and stayed with that company. Isaykin remained in the top management of the export giant as Chairman of the Board from 2011 to 2016. Rosoboroneksport functions as Rostec’s ‘cash-cow’, providing a source of steady revenue for the state corporation and thus constituting its hub.

The longstanding friend network also extends to the family members of the group. Looking at the aircraft industry we do not have to go far to find such familial connections. To give one example, the current president of the UAC, Yury Slyusar worked in the music business before joining Denis Manturov, when Manturov was appointed Chairman of the Board of the Rostec-Holding Oboronprom. Slyusar was assigned the position of Director of Commerce at Russian Helicopter, a subsidiary of Oboronprom. Later Slyusar followed Manturov to the Ministry of Industry and Trade, as Director of the Aviation Industry department. Manturov himself, in his position as acting Minister of Industry and Trade has been one of Chemezov’s closest allies since 2011. A few years later, in January 2015, Slyusar was entrusted with leading the UAC, the most important corporation of the Russian aviation industry. His father, Boris Slyusar, is known to be a close friend of Chemezov (Bekbulatova Citation2016).

Group of professional associates

Chemezov’s personal networks also include former employees and colleagues: men who had formerly worked under his leadership in the predecessor organisations of Rostec (Promeksport, Oboronprom, Rosoboroneksport, Prominvest) and had helped to integrate further enterprises into Rostec structures. He has a long history with Vladimir Artyakov, who was his deputy, both when Chemezov headed Promeksport from 1998 until 2000 and then when he headed the new arms export monopoly, Rosoboroneksport, from 2000 until 2007. When Rosoboroneksport was transformed from a trading company to an industrial holding, Artyakov was entrusted with a variety of strategic functions to ensure the incorporation of leading Russian manufacturers. This included the governorship of the Samara Oblast’ (2007–2012), home of the car manufacturer AvtoVAZ, which had just been incorporated into Rostec by Artyakov himself. He was its president and chairman from 2005 until 2007. Since 2012, Artyakov has controlled the business processes of Rostec as vice president and chairman of its most important subordinate holdings.Footnote22 Nearly all people from earlier incarnations of RosoboroneksportFootnote23 have been and are still in key positions of Rostec. This group includes Aleksey Aleshin, though his function as a qualified lawyer is mainly in legal services. He was also responsible for drafting the ‘bespoke legislation’ for Rostec, and acted as the corporation’s first vice president from 2007 to 2014.

Denis Manturov plays a key role in the aviation sector. As chairman of the helicopter factory Mil’ (2005) and as president of the Rostec subsidiary Oboronprom (2003–2007), he was responsible for the integration of Russia’s major helicopter factories into the structures of Rostec. These plants were merged under the name Vertolety Rossii as a subsidiary of the Rostec Holding Oboronprom (Starikov Citation2005). A similar function was performed by the president of UEC, Vladislav Masalov. After becoming president of the most important engine producers, Saturn (2009–2012) and Salut (2012), he integrated both companies into the Rostec holding UEC (United Engine Corporation; Obedinennaya Dvigatelestroitel’naya Korporatsiya—ODK) and became ODK’s general director (2012–2017).Footnote24

The group of backbenchers

Apart from active members of the network, Chemezov can fall back on an extensive group of confidants and advisers, who assume a more passive role and are hardly noticed in public. They often hold positions on the board of management of Rostec and its subsidiaries and mainly exercise control functions (Rostec Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2015a, Citation2015c, Citation2016a, Citation2017, Citation2018; OAK Citation2019a). Some, like Dmitriy Lelikov, have been on the board of directors of up to 30 companies in the group.Footnote25 This group of backbenchers also includes members who once played an active role but then stepped back. This applies for example to Yuri Koptev in his capacity as head of the Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos). In the early 2000s Koptev politically supported Chemezov’s plan to found the industrial corporation ‘Oboronprom’, integrating various companies of the defence sector (Krome Citation2014). When, in 2004, the then Russian government—and with it Roscosmos—was dissolved, he joined Rostec as an adviser of Chemezov and was appointed to the board of directors of the radio electronic company Kret, among others. Even now, at the age of 80, he has been elected to the supervisory board of UAC. Chemezov has a similar relationship with Boris Aleshin,Footnote26 who, as head of the Federal Industrial Agency and later as deputy prime minister (2003–2004), gave him political backing to integrate the car manufacturer AvtoVAZ and the metal giant VSMPO Avisma into Rosoboroneksport. Aleshin also moved from government structures to Rostec, holding various board positions within Rostec (AvtoVAZ) (Karulina Citation2007; Myasnikov Citation2007; Nepomnyatchiy Citation2010) and, since 2012, at UAC. Chemezov’s long-time friend Eduard Vaino has also exercised a supervisory function as a board member at AvtoVAZ (Bekbulatova Citation2016).Footnote27

Apart from the integration and controlling of enterprises, Chemezov has also been very successful in securing entry points for political-administrative influence. He is known for having personal relations with the upper echelon of the Kremlin: first, there is the personal link between President Putin and Chemezov;Footnote28 however, there is also a direct bottom-up influence on government structures. Thanks to his personal network, Chemezov has installed members of his group in state agencies like the Ministry of Industry and Trade, Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Health, and also in the FSB (Bekbulatova Citation2016; Stanovaya Citation2018).Footnote29 In the exercise of their official duties these network members are responsible for the distribution of state resources as well as for state control over SOEs. This means that, ex officio, the entrusted network members sit on Rostec’s supervisory boards with the mission of safeguarding the state’s interests. This is most obvious in connection with the Ministry of Industry and Trade, headed by Manturov, who at the same time is chairman of the supervisory board of Rostec. High positions in the ministry are also held by other members of the network, such as Vice Minister Yury Slyusar (2012–2015). Since 2015, Yury Slyusar has been president of the UAC. It speaks for the close interaction of this group with regard to UAC that Manturov was appointed chairman of the UAC at the same time.

With regard to state agencies in the defence industry sector, bottom-up influence is exercised directly by Chemezov, who is a member of the Military Industrial Commission (Voenno-promyshlennaya kommissiya—VPK) and the Commission for Military-Technical Cooperation with Foreign Countries (Federal’naya sluzhba po voenno-tekhnicheskomu sotrudnishestvu—FSVTS). In addition, he introduced his network affiliate Aleksandr Fomin to the Commission,Footnote30 who quickly advanced to become its director. Well-established connections exist to the Ministry of Defence through the support of Yuri Borisov, who previously worked with Manturov in the Ministry of Industry. As Vice Minister of Defence (2012–2018) he was responsible for defence procurement. When he advanced to the position of vice-prime minister, the defence industrial sector as a whole fell under his governance. At the same time Aleksandr Fomin moved up to the Ministry of Defence, while his position at the VPK was filled by another Rostec manager and close associate of Chemezov, Dmitriy Shugaev (Safronov Citation2018).Footnote31 The only critical voice speaking out against Rostec was Borisov’s predecessor, Dmitri Rogozin; he was responsible for the defence industrial sector until May 2018 and was critical of Rostec’s growing influence on the defence industry and complained about its lack of innovation (Kokorin Citation2018).

It is difficult to capture the extent and structure of the networks, which are continuously developing. Especially in the beginning, close personal interactions can hardly be differentiated from effective cooperation. Sometimes the character of network relations can be discerned by studying the representation of network members on company boards or looking at joint lobbying activities and investment projects (Volkov Citation2016).Footnote32 At the same time the composition of the network continuously changes, as existing members are excluded and new ones included. This makes a clear identification of network structures difficult. This particularly affects passive members from the group of ‘backbenchers’ or members from peripheral areas with whom there are only loose indirect relations. In addition, to make the picture even more blurry, individual members of the network have their own informal interaction systems too.Footnote33 Among their affiliates we find family members as well as friends and business partners. These affiliates are involved in Rostec business, through supplier and utility companies as well as financial institutions. It is a tribute to the high degree of mutual assistance and social transitivityFootnote34 within the network, that even indirect members closely cooperate and participate in national and foreign enterprises and investment projects.Footnote35

The new generation

There is also a new generation emerging, most notably within the Ministry of Industry under Manturov. This group of young technocrats are being groomed as the leadership of the future. Some have been appointed as new regional governors; some are also on the boards of SOEs.Footnote36

Compared to other state corporations, the informal interaction system of Rostec, with its authoritarian mono-centric integration and coordination mechanisms, has a relatively high capacity to act. There are fewer fragmentation dynamics, meaning that different interests can be coordinated before they lead to the formation of rival subgroups, and clear majorities, which facilitate quick decision-making processes within the different boards of the conglomerate. At the same time, given the high degree of external networking, political and economic advantages for the corporation can be enforced. However, the question arises as to what extent this ability to act is used in order to implement modernisation tasks. Here it is necessary to take a closer look at the constellation of formal and informal systems unique to Rostec and the behaviour they encourage.

Subversive incentives and sanctions

When informal relationships are ‘used’, the line between trust-building and misuse of these relationships is thin and easily crossed. This is particularly problematic when the incentives for creating non-official rents are higher than those for compliance with modernisation tasks, which are complex and long-term in nature.

In the case of Rostec, this distortion of incentives starts with the access to, and scale of, resources the corporation has at its disposal. Every year the corporation receives funds of an estimated US$21–25 billion,Footnote37 generated by government contracts, military equipment exports, the sale of raw materials and state subsidies (Rostec Citation2015b, Citation2016a, Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2019b, Citation2020b). The close relationship of the Rostec leadership to the Ministry of Industry via the Chemezov–Manturov connection means that influence can be exerted not only on the design of federal programmes but also over the initiation of new ones. Billions have been generated through programmes for import substitution, for the modernisation of the military industry and even through the reanimation of old projects from the 1990s such as the conversion of military products to civilian use (Simirnov Citation2017).Footnote38 Not included in the state support figures are state funds spent on new share issues from Rostec subsidiaries, which are joint-stock companies.

It is Rostec’s NPO status and presidential protection that hinders state authorities from controlling to what extent these funds have been efficiently used for their designated purpose. Moreover, the ongoing process of integrating new enterprises makes external control nearly impossible. Over the last years, more than 300 large enterprises have been integrated into the corporation, which earned CEO Chemezov the nickname ‘(Ros-)vaccum cleaner’ (‘Rospolysos’) (Voronov Citation2016). Taking over more and more new enterprises ensures that the turnover figures increase and, at the same time, gives access to additional government contracts and lines of credit. In other words: growth and even productivity increases can be put on the balance sheet for which no actual restructuring or modernisation measures exist.

At the same time, the operational and strategic business processes offer extensive possibilities for the privatisation of state resources and externalisation of losses. This also applies to the purchase and sale of shares of integrated companies. This has been observed in the takeover of private companies into the Rostec subsidiary, Oboronprom. The shares of the companies to be integrated were not bought directly by Oboronprom but by a private company, which obtained the shares at very low prices, some even at half the market price. These stakes were then later sold to Oboronprom for a higher value. The share purchase was financed by money from the national budget (Rafadovitch Citation2009; Kokorin Citation2017, Citation2018). Since the ‘purchased’ companies had not experienced any increase in value, this deal was a loss-making operation for Oboronprom. At the beginning of 2018, Rostec prematurely liquidated the holding due to financial problems. This practice means the state bore the liabilities, while the core assets of the helicopter industry and engine manufacturing were incorporated into Rostec (Safronov & Dzhordzhevich Citation2018).Footnote39

In summary, it can be concluded that the existing regulation system of state governance of Rostec supports quantitative growth through company acquisitions and government contracts rather than through qualitative growth generated by restructuring and modernisation. This tendency to compensate for inefficiencies of management by expansion strategies has also been observed in state-owned companies in the public sector (Radygin et al. Citation2015).

There is a danger that an uncontrollable self-serving system emerges, not only in the administrative system (Sakwa Citation2015, Citation2020) but also within the state corporation. In that process, core institutions responsible for the modernisation of Russia will steadily turn into ‘self-serving bodies’. This again leads to high implementation costs and principal–agent problems and thus weakens the governance of state corporations.

Suspended punishment

This distortion of incentives is increased through weak sanctions on target misconduct and criminal behaviour. It is possible to conceal non-compliance with modernisation tasks by methods such as virtual projects and fake contracts. The infiltration of corporate networks into the state controlling structures means that these techniques are seldom punished (Safronov Citation2014).Footnote40 Only the sporadic emergence of scandals shows the misuse of state funds. One strategy to generate state funds is the push-through of projects, which correspond with Federal Programmes. The extent to which federal funds are then used in a purpose-oriented manner (or state officials are just presented with Potemkin villages) is difficult to determine. This can be demonstrated using the example of the Science and Technology Center Leninets (since 2014 OAO Zaslon) and its managing director Alexander Gorbunov. This research institution was supposed to develop a Russian radar system for military helicopters. For this they received a R600 million advance payment from the government. The money was transferred to shell companies by Leninets and then vanished (Kashina Citation2015). But even if investigative journalists or the Accounting Chamber are able to present proof, enforcement action is very slow and often runs into a dead end. The above-mentioned case of Aleksandr Gorbunov can also serve as an example of the extent to which formal institutions can be instrumentalised. Mr Gorbunov, who stood under the protection of Chemezov, managed to escape criminal prosecution and was able to find shelter in the supervisory board of a Rostec subsidiary, despite being found guilty by the General Prosecutor of embezzlement of public funds through fake military orders.Footnote41

The distortion of incentives and sanctions results in a fundamental misdirection of the entire system, as it leads not only to a low target congruency—and therefore low modernisation and high agency costs—but also entails an ever-growing necessity for compensation and expansion. The governmental control of modernisation processes through the state industry corporation UAC has also faltered, as will be discussed below. In this case, however, other problems of state corporate governance are predominant.

UAC: the governmental SOE model

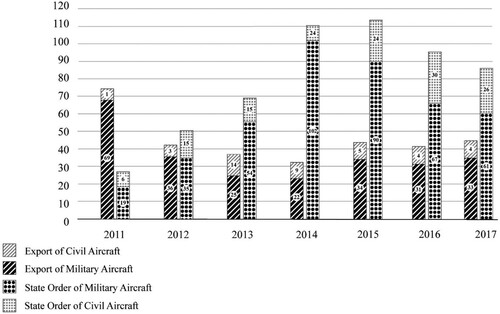

In 2006 the state corporation UAC was established by presidential decree to be analogous to the European Corporation EADS (now known as Airbus).Footnote42 Similar to the economic development of Rostec, we see here too a positive picture as far as production and turnover figures are concerned, as shown in .

TABLE 1 UAC Corporate Indebtedness and State Capitalisation

Upon closer inspection, the first impression must be revised: in fact, UAC’s economic ability to act is low and its dependence on government support high. This is reflected in the weak implementation of the modernisation targets, particularly in the civil sector, which are far from being accomplished. What is more problematic than non-compliance with absolute target figures for output, turnover or earnings is the fact that the aviation industry has degenerated structurally from an export-oriented to a state-oriented sector. While Rostec was able to sustain its economic autarchy mainly through military equipment exports, the growth of UAC was only sustained through government contracts, as shown in . The share of exports dropped from 68% in 2011 to 29% in 2016. In particular, civil aviation constituted about 11% of total UAC exports, with an output of not more than four aircraft.

FIGURE 2. Share of Export and Government Contracts

Sources: Own figure based on OAK Annual Report 2017, available at: https://www.uacrussia.ru/upload/iblock/af2/af2d72c8b7ed1bb8d76cae232dd1f87c.pdf, accessed 12 July 2021; Russianplanes.net, available at: https://russianplanes.net/planelist/Tupolev/Tu-204/214; https://russianplanes.net/planelist/Antonov/An-124; https://russianplanes.net/planelist/Sukhoi/SuperJet-100; https://russianplanes.net/planelist/Ilushin/Il-96, accessed 12 July 2021.

Neither general structural problems, such as the sectoral reorganisation of the division of labour, nor the specific problems of restructuring the enterprises of the aviation industry could be resolved. This had a direct impact on economic factors such as cost development.

As turnover also lagged behind the official targets, despite the governmental contracts, losses were inevitable, as is shown in . These losses have been manifested in a growing indebtedness. By 2014 debts had reached US$16.4 billion;Footnote43 since when they have stagnated at around US$6–7 billion (OAK Citation2019a). Without financial support from the state, this indebtedness would have been much higher.

Since 2007 the corporation has been recapitalised with more than US$15.5 billion. These funds were, above all, used for bailout measures.Footnote44 Furthermore, the corporation has been propped up with funds of US$1–2 billion every year from the federal target programmes for the development of the civil aviation and defence industries.Footnote45

These economic problems have an impact on the incentive structures insofar as they reduce the potential to generate success and profits through achieving formal modernisation targets. This makes it all the more important to understand how the stimuli for non-official rents operate and where the sources of disruptive factors lie. I will start with the formal regulation systems.

The formal interaction system

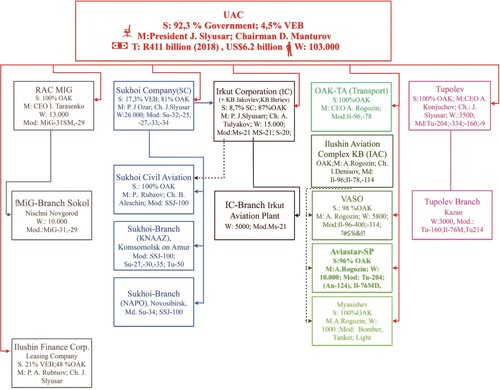

Unlike Rostec, which comprises companies from various branches, UAC is purely an industrial corporation. Thirty of the most important design bureaux (DB) developing and designing advanced technology products, including the manufacturing of prototypes, and production enterprises of the sector were integrated into the aviation corporation UAC, except for the helicopter and jet engine industries. The construction and the production sites were thereby merged into one organisation, improving UAC’s innovation potential. As shows, these enterprises were integrated into five holdings, of which each is grouped around one of the leading DB. By 2017 the UAC was able to increase its share capital in all its holdings to over 80%. The Russian state in turn holds more than 90% of the corporation (OAK Citation2007, Citation2017a).

FIGURE 3. UAC Organisation Chart 2017

Source: Own figure based on OAK (Citation2017a).

Notes: S: stakeholder; M: management; W: workforce; Mod: model of aircraft; Ch: chairholder; P: president.

Although both UAC and Rostec are formally subject to vertical corporate governance, there are significant differences in their legal status, in particular their legal independence. In short, UAC has far less legal autonomy than Rostec. This is above all due to the fact that the UAC was founded as a public joint stock company and not, like Rostec, in the legal form of an NPO. It therefore is subject to higher disclosure requirements and more external control. This control is mainly executed by the governmental agency Rosimuschestvo, which holds 93% of UAC shares. As a result, government representatives of four ministries dominate the supervisory board. Accordingly, the corporate governance of the UAC is—in contrast to Rostec—directly integrated in the structures of the Russian government. Thus, we will speak of UAC’s governmental governance in contrast to the presidential governance of Rostec.

A subversive informal interaction system: inter- and intra-organisational fragmentation

The formal regulatory framework for corporate governance proved to be too weak for the informal structures of UAC. While the formal structure of Rostec is strongly supported through the stable monocentric network of its CEO, UAC is highly fragmented due to the existence of different, rival groups in its subordinate hierarchies. These groups emerged mainly around the chief designers and general directors of the leading DB. Traditionally DBs play an important role in maintaining their respective value chains and innovation systems. Within the UAC they hold important positions in the board of management and in the board of directors.Footnote46 Fundamental conflicts arise as the DBs offer similar types of airplanes. In the field of combat aircraft, the competition between Sukhoi and MiG is well known. But also in commercial aviation the design bureaux offer competing models of the same type of aircraft.Footnote47 Accordingly, there is a high requirement for horizontal coordination between the players within the corporate bodies.

The UAC corporate board responsible for coordination and control is dominated by leading representatives from the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economic Development, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Defence and the Armaments Commission. Direct government control over the UAC is exercised by the deputy prime minister responsible for the defence industry. Until 2018 this was Dmitry Rogozin, who was followed by former Deputy Defence Minister Yuri Borisov. The fundamental problem here is that the government itself is too fragmented to take on the task of coordinating, in particular the different interests of the ministries involved. Government officials are involved in different interest constellations and often support competing models.Footnote48 The politicisation of decisions in UAC is demonstrated by the fact that the construction of the new passenger aircraft SSJ-100 (2000–2009) was the responsibility of the DB Sukhoi, which specialises in fighter jets, and not under the lead of the Tupolevtsy whose core competences lay in the development of passenger aircraft.

Since members of the different interest groups also have seats on the supervisory boards of subsidiary enterprises, some of them in up to five different enterprises, fragmentation lines run from the government level all the way down to the enterprise level.Footnote49 Thus, some officials preside over so-called ‘sobstvennye vertikaly’ (‘personal power verticals’).Footnote50

Along with government officials, Rostec was always represented in UAC’s corporate bodies.Footnote51 Rostec could therefore directly influence UAC decisions, particularly as Rostec managers are able to generate majorities through their personal relationships with government and bank representatives within the UAC.

The next section examines the incentives and restrictions that arise from formal and informal institutions and their impact on action strategies. As with Rostec, a distortion of the incentive and sanction in favour of rent-seeking can also be observed in the case of the UAC (Safronov Citation2014). The report of the General Prosecution Office refers to the creation of informal incomes, for example, by passing government funds to dependent subsidiaries at excessive interest rates or claiming high dividend payments irrespective of profits. Practices include selective and disproportionately high salary payments and the placing of orders according to patron–client relations as well as a large number of corruption cases. At the same time, the report criticises the fact that half of the authorised state funds (R36 trillion out of R84 trillion) sit in commercial bank accounts at safe interest rates instead of being invested into restructuring and modernisation projects (Safronov Citation2014; OAK Citation2019a).Footnote52

The real problem of UAC, however, lies not in rent-seeking but rather in the consequences of a lack of governance, in particular with regard to intra-corporative rivalries. Like the tip of an iceberg these are noticeable through mutual blockages and drawn-out decision-making processes. Therefore, important sectoral tasks, such as the reorganisation of the division of labour, cannot be resolved, and innovation and value-added processes have in fact come to a standstill. To give one example, ‘three years of cruel combat’Footnote53 between UAC subsidiaries Irkut Corporation and Sukhoi Civil Aviation over a general agreement on the division of labour regarding the manufacturing of two civilian aircraft ended with a very low degree of specialisation, according to the CEO of Irkut Corporation.Footnote54

Fragmentation between the corporations of the aviation industry is further aggravated by the interests of Rostec. In order to increase its influence over UAC, Rostec makes use of its representatives within UAC through their function as board members as well as UAC’s industrial dependence on supplies from Rostec subsidiaries. Over the last years, 70% of all components used by UAC were sourced from Rostec. In order to boost its influence on the demand side as well—that is to say, from airlines buying aircraft from UAC—in 2011 Rostec created its own leasing company, Aviation Capital Service, and its own financial institution, Novikombank (Pesotskiy Citation2021).Footnote55

Would Rostec use its strong position also for delaying tactics and blockage strategies? The state corporation did not hesitate in attempting to import foreign analogues to federally funded aircraft models, or to build up its own aircraft production structures. Thus, the Q-400 was played off against the domestic SSJ-100 and the Boeing 737NG against the modernised Tu-204-300.Footnote56 These projects were funded by the Ministry of Industry under the management of Chemezov network member Manturov, as previously discussed. This intra- and inter-corporation fragmentation leads not only to high agency costs but also to low or moderate qualitative growth.

The consequence of state corporate governance via the UAC can be seen by analysing the business processes of the eight large UAC manufacturers. Focusing on Aviastar-SP,Footnote57 one of the most modern aviation factories in the Russian Federation, the weak governmental governance allowed rivalries to grow into uncontrollable blockade strategies (Gusarov & Striganova Citation2014) at the expense of the manufacturer. The case of Aviastar-SP shows a large governance gap between what some government official planned, what the state corporations wanted to implement and what the manufacturer was able to produce (while the latter was primarily concerned with its own survival). The coordination problem appears in all fields of the value-creation process. In particular, after-sales service suffered, as inter-firm cooperation was not strong enough to set up an elementary network for the delivery of spare parts or to provide a repair service for already existing models such as the new Tu-204-300 and Tu-2014 SM (Dmitriev Citation2010). In the last 10–15 years under state corporate governance, Aviastar-SP has not been allowed to use its ‘existing’ core competences in the field of building passenger aircraft, nor have new alternative projects, with sufficient value-creation, been introduced. Due to the lack of specialisation within the division of labour in the Russian aviation industry, the aircraft manufacturer could hardly profit from new prestige projects (MS-21 or SSJ-100). What additionally restricted the factory management were the contradictory modernisation targets laid down by the government such as ‘preservation of the collective’ and ‘increase in productivity’ (Vasina & Skvorzova Citation2016). In 2018, after ten years of state corporate governance, no coherent restructuring measures had been undertaken and hardly any workers were laid off despite the empty order books (Dmitriev Citation2010; Pekhtereva Citation2010; Vasina & Skvorzova Citation2016).Footnote58

As a consequence, about 10,500 Aviastar-SP employees assembled two to three new airplanes per year (OAK Citation2019a). This is a fraction of the productivity of large international competitors (Boeing and Airbus). Plants of comparable manufacturers such as Airbus (A320 family) or Boeing (B-737), produce 25–47 short- and medium-distance aircraft every month.Footnote59 Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the Russian plant has been generating losses for years, and the company has become increasingly encumbered with debts, even though the plant was supported with sums amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars in the form of new issues of shares and bonds by state institutions every year.Footnote60 The debts fluctuated between US$11 billion and US$16 billion from 2014 to 2018.

To sum up, in spite of the formal integration of the most important aircraft enterprises and the leading DB, the state industry corporation UAC has been unable to fulfil government-mandated modernisation programmes. At the same time, its dependency on state bailouts has grown continuously. Sanctions, due to low state control, have proved to be weak. In the long term, the UAC will pay a high price: that of losing its formal independence.

The Kremlin’s response to the shortfalls of vertical corporate governance via state-owned corporations after 2016–2017 was similar to the one it adopted in the case of vertical territorial governance: when, after 2007–2008, the power vertical for territorial governance started to weaken and subnational regimes emerged again, the Kremlin reacted by imposing further restrictions on the freedom of action of regional and local officials (Gel’man & Ryzhenkov Citation2011; Zubarevitch Citation2017). In the case of vertical or state corporate governance in the aviation industry, though, this has been done not by strengthening the power vertical of the state structure but by strengthening the corporate power vertical of Rostec, even though Rostec’s modernisation performance could hardly have been judged a success.

Comparison of different forms of state corporate governance

shows that both models of state corporate governance generate low innovation and high agency costs. Responsibility for this lies, to a large extent, with the subversive informal systems.

TABLE 2 Forms of State Corporate Governance in the Aviation Industry (dominant characteristics)

The governmental SOE model cannot use its high innovation potential and higher target congruency because of its extensive informal intra- and interorganisational fragmentation, meaning the rivalry between the different DBs within the corporation as well as the weak coordination between the SOE and external organisations like Rostec and different state agencies. In particular, the fragmentation of supervisory governmental bodies itself undermines coherent state governance. These difficulties have a negative impact on sales figures and production costs, which then increase indebtedness and dependence on state support.

In comparison, the presidential NPO model is an autarchic form, operating outside the control of the formal external structures of the government and market forces. This autarchy is supported by its informal systems, which, in contrast to the governmental model, are consistent with the formal structure of the corporation; the influence of individual interest groups or personalities within the Rostec conglomerate is too weak and their dependence on Rostec and Chemezov too strong. At the same time, due to its strong personal bottom-up channels to key persons in the relevant state agencies who exert a strong influence on the distribution of resources and privilege, this model can secure a high degree of self-sufficiency (economic autarchy) which, in combination with its suspension of punishment, allows a high level of freedom of action. But although the Chemezov network as an autarchic regime has a higher ability to act, it does not generate greater reform success, as it does not use this ability for the implementation of modernisation targets. This misuse of freedom is encouraged by its informal network system, which results in counterproductive incentives and sanction stimuli. Thus, the incentive and sanction system of the state corporation promotes private extraction and avoidance of punishment. This leads to a growing gap between official and private targets as well as uncontrollable agency costs.

Looking at the mechanism to avoid sanctions for inefficient and ineffective behaviour, the two corporations have developed different ‘modes of survival’. The survival of the ‘governmental model’ of the UAC is based on the ‘indebtedness option’. Here losses are financed by debts, the debts are paid off via new issues of shares and these shares are then bought by the state. The NPO-model, in contrast, relies more on an expansion strategy, securing access to further resources via mergers and acquisitions, new state orders, bespoke federal projects and monopoly rights. Formally, this expansion strategy is explained by its role as the ‘saviour’ of troubled industries, a function Rostec also fulfils. Thus, the boundaries between help and the misuse of competences are blurred.

The takeover and dominance of the presidential NPO model

Against this background, the integration of the aviation industry into the state corporation Rostec in 2019 turns out to have been a logical step. It became obvious in 2015 that the UAC faced incorporation into Rostec as a growing number of Chemezov’s associates were placed in leading positions within the UAC bodies,Footnote61 before the integration of UAC into Rostec was finalised in 2019 (see ).Footnote62 The takeover process was accompanied by a further concentration within the UAC. In 2017 the integration of MIG enterprises into the Aviation Holding Company Sukhoi was decided,Footnote63 as well as the takeover of Sukhoi Civil Aircraft (SCA), the civilian arm of the Sukhoi Company by Irkut Corporation. Furthermore, a number of production enterprises were placed under the administration of the conglomerate Ilyushin Aviation Complex.Footnote64 In the course of this concentration process, the CEOs of the manufacturing companies were downgraded to department manager status, with UAC alone acting as the executive body (OAK Citation2020a). There is a risk that the described measures will lead not to improved coordination or greater saving in administrative costs but to further bureaucratisation, whereby ever larger organisational units are led by fewer actors with executive responsibility, which in turn can entail the rise of principal–agent problems.

TABLE 3 UAC Board of Directors 2019–2020

The merger process is far from over and will at least take two to three years (Kostinskiy & Vedeneeva Citation2019). There will be exchanges of assets between the UAC and Rostec, such as Russian Helicopters merging with UAC structures.Footnote65 At the same time we will see further integration of new external companies (Afanasyev Citation2020). Figures such as Viktor Grigorev, owner of NK Bank and various defence companies (Dzhordzhevich Citation2017), Vladimir Yevtuchenko, the owner of the investment group AFK Sistema, and new investment funds like the Marathon Group may play an important role in building new monopolies for Rostec not only in the pharmaceutical industry but also in microelectronics and aviation technology.

Looking at the board of directors for 2019–2020 (OAK Citation2020b), we see that the UAC is under the leadership of Chemezov’s associates, with Slyusar as CEO and Serdyukov as chairman of the supervisory board. The sub-holdings are all chaired by Yury Slyusar, with the exception of the DB Yakovlev, chaired by Ravil Khakimov. Khakimov is deputy to Manturov and known for being close to Chemezov. He is also president of Irkut Corporation and, after the integration of Sukhoi Civil Aircraft Company, thus head of the commercial aviation of UAC. Since 2017 we have not only witnessed a further consolidation of the group around the Rostec head Chemezov, with representatives from the old interest groups like Oleg Demchenko and Mikhail Pogosyan gradually marginalised,Footnote66 but also diminished influence from government agencies.Footnote67 This should not come as a surprise, since the candidates are no longer proposed by the government but by Rostec.

After the integration of the aviation industry into the state corporation Rostec the issue of ‘informality’ will become even more important. So far, the process of integration has had an impact on disclosure and transparency. Apart from the fact that the annual reports are no longer published in English, the information given is reduced.Footnote68 The key performance indicators of the affiliated companies, which hitherto could be monitored in UAC’s annual reports, are no longer accessible (OAK Citation2017b, Citation2018, Citation2019b, Citation2020b).

Conclusion: dominance of the presidential NPO model

This article has shown why sector governance through state corporations had led modernisation processes in the Russian aviation industry into a dead end. This applies to both state corporate governance forms, the public governmental SOE model as seen in the UAC and the presidential NPO model of Rostec. So why did the Kremlin try to solve the sector’s modernisation lag through the integration of the UAC in 2019 into one of the biggest state corporations? What is the comparative advantage? What can be expected in the future?

The comparative advantage of the presidential NPO model, as the article has shown, lies in its strong informal network, its higher autarchy and the protection of the president. This will, in the short term, improve access to resources also for the UAC and its subsidiaries. Governance through Rostec may also become quicker and more coordinated, at least at the higher levels of the hierarchy between Chemezov, the president and the heads of the involved ministries. In the medium-to-long term, however, there is the danger that integration into the NPO Rostec will lead to a further politicisation of the UAC subsidiaries and thus a further decrease in the relevance of economic restrictions as well as a further informalisation of the modernisation processes in the aviation industry. Attention should be paid to the sector’s innovation ability. The hierarchical downgrading of managers from CEO- to department manager-status as part of the integration and reorganisation process encourages an administrative mentality rather than risk-taking and innovation-driven entrepreneurship. The effects of the reduced role of the general constructors on the innovation and production process remain to be seen, in particular as the heads of the DBs have been considered to have an important integrating function in the aviation sector. Time will show whether the rivalry between the leading DBs can be better coordinated within the Rostec conglomerate or whether conflict will be simply transferred to the lower levels of the hierarchy, leading to new forms of micro-fragmentation.

The other comparative advantages of the NPO model lie in its higher opacity as well as its many options to compensate for any mismanagement by camouflaging inefficiencies and non-compliance with official targets. At the same time, the model includes an extensive rent-granting system for everyone who plays by its rules. To keep this system going, the state corporation relies on its expansion strategy, needing more resources generated via mergers and acquisitions, new state orders, bespoke federal projects and monopoly rights. This strategy not only increases agency costs and distorts incentives and sanction stimuli but develops its own momentum, which should not be underestimated: the lower the efficiency and effectiveness of a state corporation, the more it relies on its expansion mechanisms, dragging more parts of the economy into its sphere of influence.

More research is needed on how the integration of the aviation conglomerate UAC into the state corporation Rostec affects the modernisation process. Empirical research and case studies of affiliated companies provide insights beyond the official announcements and annual reports. Beyond that, questions arise as to how the growing dominance of the NPO model affects other industrial branches of the Russian economy; the similarities and differences between state corporations; and where corporate expansion ends. Changes are most likely in connection with the need for further capital. Will we see stronger involvement by real independent investors, entailing a better enforcement of corporate governance control, or will we witness the consolidation of a new variant of state capitalism under the president, whereby most important companies of the Russian economy paradoxically exist outside the control of state and society?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicole Krome

Nicole Krome, Independent researcher. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 The Global Innovation Index, 2014, available at: https://www.wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=3254&plang=EN, accessed 9 July 2020; The Global Innovation Index, 2019, available at: https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/gii-2019-report#, accessed 9 July 2020. Russia improved its position in the Global Innovation Index in the 2000s but has been stagnating at 45th or 46th place for some years now. Its resource efficiency is declining, as more resources have to be used to achieve innovations. In terms of output factors such as patent applications per capita, Russia has fallen back to the level of 2001 (see, ‘The Global Economy, Russia: Patent Application by Residents, 1992–2019’, The Global Economy, available at: www.theglobaleconomy.com/Russia/Patent_applications_by_residents, accessed 9 July 2020).

2 Ukaz Prezidenta Rossiiskoi Federatsii No. 596, ‘Ob imushchestvennom vznose Rossiiskoi Federatsii v Gosudarstvennuyu korporatsiyu po sodeistviyu razrabotke, proizvodstvu i eksportu vysokotekhnologichnoi promyshlennoy produktsii “Rostekh”’, Ofitsial’nyi internet-portal pravovoi informatsii, 24 October 2018, available at: http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201810240026?index=2&rangeSize=1, accessed 30 August 2019.

3 ‘Airbus ot chemezova’, RBK, 19 July 2018, available at: https://www.rbc.ru/society/19/07/2018/5b4f3c889a79475bf5f58f32, accessed 9 July 2020.

4 Federal`nyy zakon ot 12.01.1996 No. 7 ‘O nekommercheskikh organizatsiyakh’, stat’ya 7.1, Zakony, kodeksy i normativno-pravovye akty Rossiyskoi Federatsii’, 11 June 2021, available at: https://legalacts.ru/doc/FZ-o-nekommercheskih-organizacijah/, accessed 8 July 2021.

5 Networks allow for quick and pragmatic governance on the one hand but on the other produce lock-in effects and high transition costs.

6 Other factors, such as stock exchange listing, the use of international accounting rules, and transparency and information disclosure, can be seen as indicators of functioning external corporate control.

7 The UAC’s 2007 annual report mentions 106 companies, which is the most reliable figure to date. Occasionally, 248 companies are mentioned, but reliable sources are lacking; available at: https://www.uacrussia.ru/upload/iblock/a7f/a7f20ee194dd3a47539bf2a81fc22616.pdf, accessed 7 September 2021.