Abstract

This article examines Soviet approaches to sexual health in the Brezhnev era (1964–1982), specifically venereal diseases (VD). After the death of Stalin, the Soviet leadership adopted new methods for regulating the behaviour of Soviet citizens based on collective adherence to specific moral codes. State ministries took tentative steps towards mass sex education. In the 1960s, the Soviet leadership relaunched the ‘struggle with VD’, a state-led campaign to drastically reduce rates of infection. This article explores the enactment of this campaign in the Latvian SSR, where VD cases exceeded all-union averages and where Party leadership adopted a stringent approach to perceived sexual misconduct.

In 1974, Ligai, a 23-year-old sailor in the Soviet Navy, was sailing off the coast of South Africa when the captain of the ship received a message from a medical facility in Arkhangel’sk, a city located just outside the Arctic Circle.Footnote1 Ligai had been identified as a contact of a syphilis patient in the city, which meant that he had either had sex with, or been in very close contact with, the infected individual. As Ligai was thousands of miles away from the USSR on the other side of the world, it was not possible to send him to a Soviet port for treatment, so the medical facility sent a treatment plan to the ship’s doctor via radio telegram. As this case indicates, venereal diseases (VD) generated significant anxiety for the Soviet authorities. Beginning in the early 1960s, the Soviet leadership launched a campaign to address rising levels of venereal infection across the USSR. This campaign, known as the ‘struggle with VD’ (bor’ba s venericheskimi zabolevanyami), combined welfare and repression. Plans for the improvement of diagnostic and therapeutic methods were developed alongside the classification of those who became infected as immoral and antisocial, as well as the criminalisation of VD transmission. This article examines how this campaign played out in the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) during the premiership of Leonid Brezhnev (1964–1982), focusing on two key tools that the Soviet leadership used to prevent VD transmission: criminal law and sex education. Soviet VD policy offers a lens to explore broader developments in criminal prosecution, state control, and attitudes to morality and sexuality. Brezhnev-era approaches to VD laid the groundwork for official responses to HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s, as stereotypes about the type of people who became infected and calls for their criminalisation took on a new significance amid the global epidemic.

Latvia was forcibly absorbed into the USSR at the end of World War II following occupation by both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany during wartime. After annexation, the Latvian republic formed part of the Soviet Union’s western borderlands. Located at the country’s western periphery, this region had stronger connections with the capitalist West than other parts of the Soviet Union, which contributed to its reputation as a centre of illicit, criminal and anti-Soviet activity (Leps Citation1991, p. 81; Risch Citation2015, pp. 73–5; Cohn Citation2018, p. 774). This reputation perhaps motivated the Soviet leadership in Latvia to implement particularly stringent measures to address perceived sexual misconduct. In the 1960s, while legal experts questioned whether consensual sodomy ought to be decriminalised in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the Rīga police authorities proposed the criminalisation of female same-sex relations, although this idea was rejected by the authorities in Moscow (Alexander Citation2018a, p. 35). The maximum prison sentence for sodomy was also higher in the Latvian SSR than in other Baltic republics (Healey Citation2018, p. 171; Lipša Citation2019, p. 100, n. 20). In 1977, the Supreme Court of the Latvian SSR unsuccessfully advocated for the criminalisation of ‘perverted’ sex, including the ‘disgusting’ practices of coercive oral and anal sex (Alexander Citation2018a, p. 49). The Latvian capital of Rīga was also home to the first-ever Soviet vice squad, which was established in the city in 1987 (Hazanov Citation2016, p. 214).

The Latvian SSR reported higher incidence of VD than other regions of the Soviet Union in the early 1970s, which caused great concern and embarrassment for Latvian Party leaders.Footnote2 In May 1973, at a meeting of the Bureau of the Communist Party of the Latvian SSR, Viktors Krūmiņš, the deputy chairman of Latvia’s Council of Ministers, claimed that because of increasing infection rates, ‘outside the republic, people are saying that Rīga and Ventspils are the seediest places in the entire Soviet Union’.Footnote3 He was keen to shake this reputation, and vowed to make the Latvian SSR the antithesis of the United States, which he defined as the ‘root of all moral promiscuity and debauchery’.Footnote4 The perceived scale of the problem and its potential to bring about reputational damage, coupled with attempts at the republican level to criminalise ‘problematic’ sexualities, meant that the ‘struggle with VD’ was waged enthusiastically in the Latvian SSR.

The Soviet Union’s first criminal code of 1922 made knowingly infecting another person with VD a criminal offence carrying a three-year prison sentence.Footnote5 The USSR was not alone in criminalising the transmission of VD in the interwar period. Health became an important component of citizenship across Europe in the twentieth century, as concerns regarding public health eclipsed individual rights in a variety of different international contexts. VD transmission was criminalised in Denmark from the late nineteenth century (Blom Citation2006), in Sweden from 1919 (Lunderberg Citation2008), in Weimar Germany in 1927 (Roos Citation2010, p. 2) and in Poland from 1932 (Barański Citation2012). After the end of World War II, anti-VD legislation was introduced in Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and East Germany (Timm Citation2010, pp. 197–98; Wahl Citation2019).Footnote6 Discourses of morality permeated discussions of VD in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, as the moral judgement of people infected with syphilis, gonorrhoea and, more recently, HIV has a long trajectory, stretching across a variety of different chronological and geographical parameters. However, the moral component took on a greater significance in the USSR because of the official socialist code of behaviour and participation, as well as the rigidity of public discourse. Soviet socialism was a culture that demanded total participation and regarded passivity as active dissent and was therefore particularly responsive to phenomena that deviated from the normative framework (Fürst Citation2017, p. 13). Given the inconsistently enforced but ever-present state control over public discourse, discussions of the ‘struggle with VD’ could not dwell on the exacerbating issues of poor facilities and material shortages, so instead reverted to the ‘familiar Soviet discourse of blame’ which prioritised individual moral failings over systemic problems (Field Citation2007, p. 63).

Adherence to socialist codes of behaviour became especially important in the decades following Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, as the Soviet regime looked to new technologies of power in its efforts to move away from the excesses of Stalinist repression. Under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev (1956–1964), Soviet officialdom developed new methods for disciplining Soviet citizens based on mutual surveillance and collective adherence to specific standards of behaviour (Field Citation2007; Cohn Citation2015). Social control pivoted towards ‘the mundane, the ordinary and the everyday’, as new legislation introduced in the late 1950s and early 1960s expanded definitions of antisocial behaviour to include a wide range of activities committed in both the public and domestic spheres (Fitzpatrick Citation2006; LaPierre Citation2006, p. 352; Citation2012). After the decriminalisation of abortion across the Soviet Union in 1955, medical intervention and public health campaigns replaced prohibition and force as methods for regulating gender and sexuality (Randall Citation2011). The campaign to ‘struggle with VD’ stood at the intersection of these new trends of governance. VD transmission was redefined as antisocial behaviour in the early 1960s and calls for ‘malicious’ transmitters to feel the full force of criminal law grew ever more insistent. Anti-VD public health campaigns delineated norms of sexual behaviour in medicalised language, classifying casual and extramarital sex as potent health risks. Rather than being a period of liberalisation, de-Stalinisation and cultural ‘thaw’, the Khrushchev era laid the groundwork for increased interventionalist VD policy in later decades (Dobson Citation2009; Hornsby Citation2013; Healey Citation2018; Ilič et al. Citation2004).

This article builds upon recent histories that challenge the categorisation of the Brezhnev era as a period of stagnation during which political, social and cultural change ground to a halt (Fainberg & Kalinovsky Citation2016, pp. vii–xxii). Until recently, scholars argued that although the sexual behaviour of Soviet citizens underwent transformation in the long postwar era in line with trends observed in other industrialised countries, little changed in state approaches to sex and sexuality. For example, Kon (Citation1995) and Rotkirch (Citation2005) largely regard the Brezhnev era as a period of the ‘domestication’ of sexuality, where only minor changes were made to sexual policy. However, in recent years, scholars have turned their attention towards the significant shifts in official and expert discourses on sex and state approaches to ‘problematic’ sexualities that began under Khrushchev and continued under Brezhnev. In the early 1960s, the Soviet Medical Publishing House brought out a number of sex education manuals, some of which were produced by experts from across the Eastern bloc and translated into Russian and the other languages of the USSR, including Latvian (Zelče Citation2003, pp. 112–14; Alexander Citation2018c, pp. 351–55). Medical, sociological and legal discourse was far from monolithic: extensive debate about sex education reverberated in the Soviet press throughout the 1960s and 1970s and experts discussed changing state policy towards gay men and lesbians (Healey Citation2014, pp. 240–42; Alexander Citation2018a, Citation2019). In 1972, Latvian surgeon Viktors Kalnbērzs performed the first successful sex reassignment surgery in the USSR, although this was not publicised in the Soviet media at the time.Footnote7 Sexualised and nude images appeared in regional journals and magazines with increasing frequency due to the slight relaxation of censorship beginning under the conditions of Khrushchev’s thaw and the development of amateur photography (Vikulina Citation2011; Vaiseta Citation2019; Werneke Citation2019). At the same time, new policing practices resulted in a surge in convictions for sodomy in various Soviet republics throughout the 1960s–1980s (Veispak Citation1991; Valodzin Citation2016, pp. 23–6; Healey Citation2018, pp. 170–74).

This article contributes to this literature by examining the increasingly interventionalist nature of state approaches to VD in the Brezhnev era. Despite substantial investment in health and welfare, many indexes of health declined in the 1970s and 1980s, much to the concern of Soviet officialdom (Bernstein et al. Citation2010, p. 5). For the very first time, medical authorities harnessed the power of broadcast media as a method for preventing VD transmission. The increasing availability of radios and televisions in the 1960s and 1970s meant that information about VD and the boundaries of appropriate sexual behaviour entered the homes of Soviet citizens more frequently than ever before. At the same time, Soviet leadership adopted a zero-tolerance approach to individuals perceived to be spreading VD. Criminal law became the preferred solution for preventing infection, and legal definitions of who could be constituted a ‘malicious’ spreader of infection expanded significantly. The USSR’s sexual revolution followed a different trajectory to simultaneous revolutions in the West, but the Brezhnev era was characterised by significant shifts in discussions of, and state policies towards, sex and sexuality.

The beginning of the Soviet ‘struggle with VD’ in Latvia

In June 1940, Soviet troops invaded Latvia (as well as Lithuania and Estonia) and began rapid and brutal Sovietisation. This process was interrupted by the invasion of the USSR by Nazi Germany in June 1941, but Sovietisation resumed once again when Latvia was forcibly absorbed into the USSR following the eastward advance of the Red Army. All aspects of Latvian political, economic, social and cultural life were reorganised according to the Soviet model (Swain Citation2003; Zubkova Citation2008, pp. 128–90). The immediate postwar years were characterised by large waves of Slavic migration, as workers, specialists and administrators moved to Latvia from other regions of the USSR. By the mid-1950s, Russian was the dominant language of communication in various ministries, the police, medical institutions, state farms and the industrial sector (Loader Citation2017, pp. 1083–84).

The Soviet ‘struggle with VD’ quickly began in Latvia following its absorption into the USSR, at a time when the top rungs of government began to take stock of the impact of the colossal destruction and endemic dislocation of total war on public health. The incidence of syphilis and gonorrhoea, like other infectious diseases, had skyrocketed during the war years (Nakachi Citation2011, p. 5).Footnote8 The USSR’s People’s Commissariat of Health (Narodnyi komissariat zdravookhraneniya SSSR) blamed the dramatic increase on the ‘arrival of German-fascist invaders’, but in reality the reasons were primarily a result of domestic factors and the destruction of total war (Galmarini-Kabala Citation2016, pp. 180–84).Footnote9 Civilians struggled to access treatment in wartime because the civilian medical apparatus had shrunk dramatically, as hospitals, clinics and laboratories were handed over to the military and medical staff were drafted into the army (Filtzer Citation2017, p. 78). The production of anti-VD medications essentially ground to a halt because of prewar problems with the production and supply of pharmaceuticals, the redirection of industrial production to serve the defence industry, and the hasty evacuation of chemical and pharmaceutical factories eastwards after the invasion of the USSR in 1941 (Conroy Citation2004a; Citation2008, pp. 17–38; Harrison Citation2005). The manufacture of hydrosulphite (essential for anti-syphilis treatments such as novarsenol and osarsol) ceased because the necessary equipment for its production was removed from dedicated chemical factories and moved to eastern factories directly serving the war effort.Footnote10 Condom manufacturing was also suspended, as industrial production during wartime was redirected at Kiev’s Red Rubber Worker Factory (Krasnyi rezinshchik zavod) and the Bakovskii Factory just outside Moscow.Footnote11

In August 1945, the highest executive authority in the Soviet Union, the Council of People’s Commissars (Sovet narodnykh komissarov, hereafter Sovnarkom), issued an order calling for a union-wide re-intensification of the ‘struggle with VD’. The People’s Commissariat of the Rubber Industry (Narodnyi komissariat rezinovoi promyshlennosti) and the People’s Commissariat of Local Industry of the RSFSR (Narodnyi komissariat mestnoi promyshlennosti RSFSR) were instructed to recommence the production of condoms from 1 January 1946 at a rate of 30 million per quarter.Footnote12 The People’s Commissariat of the Chemical Industry (Narodnyi komissariat khimicheskoi promyshlennosti) was obliged to restore the production of hydrosulphite and para-aminophenol so that the manufacture of anti-syphilis medications could be resumed in autumn 1945. Essential materials that could not be easily procured within the USSR, such as latex and the arsenic product mafarsen, were to be imported by the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Trade (Narodnyi komissariat vneshnei torgovli). Sovnarkom’s order instructed the republican and regional commissariats of health to dismiss venereological specialists from evacuation hospitals and send them to work in urban and rural venereal clinics, while also finding the money within their budgets to build hundreds of new treatment facilities and train hundreds of new specialist medical personnel.Footnote13

Sovnarkom instructed republican governments to develop action plans for reducing rates of venereal infection, and they were given targets to expand and improve their VD treatment facilities. The newly annexed Baltic republics were ordered to send reports on their existing venereological networks to Moscow so that expansion could be centrally planned.Footnote14 The Latvian SSR was given ambitious targets. By 1 January 1946, Latvia was to open eight new treatment centres, make 40 new hospital beds available for VD patients, and train 25 new venereological specialists and an additional 50 rural medical workers.Footnote15 New targets for the expansion of the network of venereological treatment and research centres and the training of venereological specialists also featured in the Latvian SSR’s first Five Year Plan, which was launched in 1946.Footnote16 The Soviet Criminal Code replaced the Latvian republic’s penal laws immediately following annexation. The transmission of VD had been legislated against in interwar Latvia, but this law was replaced with the Soviet alternative (Lipša Citation2014, pp. 435–41).

The arrival of the ‘struggle with VD’ in Latvia was used as propaganda to champion the apparent superiority of the Soviet healthcare system and the benefits of Latvia’s forced absorption into the USSR. In 1948, Latvia’s health commissariat claimed that ‘in the republic of Latvia before Soviet power, medical care for VD patients was far from satisfactory’ and that the annexation had apparently brought ‘reliable and free treatment’.Footnote17 This statement is difficult to verify given the lack of comparative studies of healthcare in interwar and Soviet Latvia, as well as Soviet officialdom’s tendency to overstate success in the fields of venereological treatment and research (Hearne Citation2017, pp. 183–89).Footnote18 Soviet annexation posed obstacles for monolingual Latvians seeking VD treatment. Latvia’s prewar medical profession was decimated due to the mass emigration of Baltic Germans in 1939, the devastation of the Holocaust, and the exodus of over half of doctors fearing Soviet repression in the final stages of the war.Footnote19 In the early 1950s, just over one quarter of venereological specialists in the Latvian SSR were identified as Latvian, whereas 65% were from other Union republics, mostly ethnic Russians.Footnote20 Most specialists had completed their medical training outside Latvia (a trend that continued throughout the entire Soviet period) so likely used Russian as their primary language for communicating with patients (Loader Citation2015, p. 118).Footnote21

These issues aside, Ineta Lipša’s research indicates that the incidence of VD was higher in interwar Latvia than after Latvia’s absorption into the USSR (Lipša Citation2019, p. 95). The republican health authorities reported a significant decrease in incidence of syphilis and gonorrhoea between 1946 and 1952 across the Latvian SSR.Footnote22 Similar declining rates of infection were also observed in the Estonian, Karelian, Turkmen and Armenian SSRs, as well as in 25 other regions and cities.Footnote23 This union-wide trend was likely an inevitable decline brought about by improvements in living conditions, nutrition and public health following the transition from wartime to peacetime. The increasing availability of the ‘wonder drug’ penicillin, a highly effective anti-syphilis treatment, may have also had an impact. Soviet microbiologist Zinaida Ermoleva first synthesised penicillin for the military during World War II. Although there were problems with the organisation of mass production during the war years, by 1948 penicillin was produced at factories in Moscow, Rīga and Minsk at an increased capacity (Conroy Citation2004b, pp. 158–59).

The push for criminalisation

In the early 1960s, VD became an extremely concerning public health matter once again. The planned expansion and improvement of the USSR’s venereological treatment facilities outlined in the late 1940s had stalled by the mid-1950s, perhaps unsurprisingly given that republican health commissariats had not been granted any additional funding to construct large numbers of new VD clinics and train hundreds of new specialists. In 1963, the USSR’s Ministry of Health (Ministerstvo zdravookhraneniya SSSR) issued an order chastising regional and republican health authorities for the sharp increase in VD in the early 1960s.Footnote24 The order emphasised the need for health education programmes, new specialists and improved facilities, and also instructed health authorities to collaborate closely with the police and prosecutors to prosecute transmitters under the anti-VD law. This section explores how the call by the Party leadership in Moscow for greater use of criminal law to prevent VD transmission was answered by the republican authorities in Latvia.

Moscow’s call for the criminalisation of those who transmitted VD was part of the broader official response to the social consequences of World War II and the immediate postwar years. First of all, war ravaged the Soviet population, as an estimated 27 million lost their lives, approximately three-quarters of whom were men. This demographic catastrophe tore families apart, severely destabilised the sex ratio, and generated enormous concern about the possibilities for social and economic postwar reconstruction. Legislative changes in the early 1940s were introduced with the explicit aim of increasing the birth rate through providing financial incentives to women to bear more children, removing the financial responsibility of alimony from men, and taxing individuals and couples who either chose, or were not able, to have children of their own (Nakachi Citation2006; Ironside Citation2017). Nevertheless, the legacy of wartime population depletion, coupled with increased urbanisation, the rising age of marriage, and increased infertility and mortality rates, meant that union-wide population growth continued to decline throughout the 1950s and 1960s (Anderson & Silver Citation2000). The impact of VD on the reproductive capabilities of Soviet citizens (especially women) would have been especially concerning in this climate.

Secondly, popular and official anxiety about manifestations of immoral and criminal behaviour proliferated in the decade after the death of Stalin in 1953. The Gulag system was significantly scaled back from the mid-1950s onwards and millions of camp prisoners were amnestied with the hope of their rehabilitation and reintegration within society. The mass return of former prisoners into civilian society provoked moral panic across the Soviet Union, and the crime waves that followed were a matter of grave concern for the Soviet government (Dobson Citation2009). In 1956, Citationa petty hooligan decree was implemented across the USSR which unveiled a new zero-tolerance approach to antisocial behaviour, including insolence, drunkenness, the use of obscenity, noise disruption and ‘other indecent acts’, committed in either public or domestic spheres (LaPierre Citation2006). ‘Anti-parasite’ laws were enacted across the Soviet republics from the late 1950s onwards, which targeted individuals who made a living from the informal economy, refused to work or socialised with foreigners (Fitzpatrick Citation2006). The Soviet leadership also worried deeply about penal sexual culture seeping into and infecting the wider society following the scaling back of the Gulag system. VD was reportedly widespread in the camps, most likely because of cramped living quarters and unhygienic conditions, so the push to criminalise VD transmitters was likely linked to state ambitions to limit the spread of diseases outside places of confinement (Bell Citation2015, pp. 204–5; Healey Citation2018, p. 33). In 1958, the Ministry of Internal Affairs instructed police to make greater efforts to crack down on male homosexuality, driven by concern regarding the prevalence of sodomy in the camps and the ‘contagion’ of homosexuality seeping into wider society following the mass release of prisoners (Healey Citation2018, p. 170). In 1959, the Gulag’s medical director claimed that VD was spread ‘almost exclusively as a result of sodomy’, so it is highly likely that the crackdown on transmitters of VD in the 1960s and 1970s was suffused with state-sponsored homophobia (Alexander Citation2018b, pp. 38–9; Healey Citation2018, p. 41). In the Latvian SSR, the Ministry for Health identified homosexual men as a special category to be targeted in the ‘struggle with VD’ in the early 1960s (Lipša Citation2019, p. 101).

Finally, issues related to morality and sexuality were reframed under the social and political conditions of the Khrushchev era. After Stalin’s death, the Party leadership publicly rejected Stalinist wide-scale terror and searched for new methods of governance based on mutual surveillance and the collective adherence to state-approved standards of behaviour. From the late 1950s, thousands of ‘comrades’ courts’ (tovarishcheskii sud), which were voluntary organisations charged with keeping order within workplaces and apartment buildings, were established throughout the country. Comrades’ courts could hear cases on antisocial behaviour that did not technically contravene written law, including poor work discipline, drunkenness, neglect of children or damage to public property, and could apply sanctions, including public warnings or fines, and even initiate eviction proceedings (Field Citation2007, p. 30). At the 22nd Party Congress in 1961, Khrushchev issued the ‘Moral Code of the Builder of Communism’: a set of 12 vaguely worded tenets articulating the code of ‘communist morality’, an ideology that was to govern all aspects of both public and private life. The inclusion of moral principles within an official party programme illustrates a shift towards ‘instilling ethics and regulating conduct’ as a method of social control (Field Citation2007, p. 12; Cohn Citation2009). Relatedly, Soviet policy towards sex education shifted from Stalinist-era silence to the thorough examination of issues related to sex. Throughout the early 1960s, the Soviet State Medical Publishing House published several brochures on sex education in Russian and other languages of the Soviet Union aimed at preventing young people from engaging in specific sexual behaviours, such as homosexuality, premarital sex and extramarital sexual relations (Zelče Citation2003, pp. 112–14; Alexander Citation2018c). At the same time, the sexual behaviour of Soviet citizens was changing in line with broader trends observed in other industrialised countries, such as a greater tolerance of extramarital sex, smaller families, a higher number of divorces and the earlier onset of sexual life (Kon Citation1995, pp. 88–9; Rotkirch Citation2005, p. 94).

The USSR’s Ministry of Health’s 1963 order to intensify the ‘struggle with VD’ was set against this backdrop of fervent discussions of sexuality, morality and antisocial behaviour. The call was enthusiastically answered in Latvia. In 1964, the Latvian Ministry for Health (Latvijas PSR veselības aizsardzības ministrija/ Ministerstvo zdravookhraneniya Latviiskoi SSR) asked the Latvian Council of Ministers (Latvijas PSR Ministru Padome/Soviet ministrov Latviiskoi SSR) to pass a resolution permitting the forced medical examination and treatment of individuals suspected to have VD (Lipša Citation2019, p. 106). In 1966, the Latvian Council of Ministers submitted a draft decree for consideration by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR proposing that ‘people leading amoral lifestyles’ who were infected with VD ought to be forced to undergo treatment and labour re-education for between six months and one year.Footnote25 Soviet health authorities already had the right to forcefully examine and treat people suspected to have VD from 1927 (Bernstein Citation2011, p. 180), but the Latvian Council of Ministers proposed that ‘amoral’ (amoral’nyi) infected individuals be identified by the police, advocating a closer working relationship between law enforcement and health organs. Their proposal also formalised forced treatment as a method of punishment, as sentences were to be decided at an open session in a people’s court and would not be subject to appeal.Footnote26 Forced treatment and re-education was to take place at labour-treatment dispensaries (lechebno-trudovoi profilaktorii), which were opened for alcoholics who resisted treatment for alcoholism, relapsed following treatment or who ‘disrupted labour discipline, social order or the rules of socialist communal life’ from 1967 (Raikhel Citation2016, pp. 65–6). Labour-treatment dispensaries were essentially places of incarceration, as individuals who escaped from these institutions could be prosecuted under the republic’s criminal code. Unlike other forms of treatment in the Soviet healthcare system, a stay at the dispensary would not be free. Instead, deductions were made from the salaries of those sentenced to forced treatment to cover the costs of their food, clothing, shoes and medicine.Footnote27

The Latvian Council of Ministers justified their draft decree on the basis that providing medical treatment for the sick was expensive for the state. Although the treatment of VD amongst ‘people leading amoral lifestyles’ was effective, these individuals were apparently not always adequately re-educated, which resulted in repeated courses of treatment and continued ‘amoral offences’.Footnote28 The Council of Ministers claimed to be in a difficult situation as most ‘amoral’ people were engaged in state-sanctioned labour and had not actually committed any crimes, so they could not be prosecuted as parasites or receive criminal sentences. Incarceration within a labour-treatment dispensary would reduce treatment costs and bring ‘amoral’ citizens more directly under the gaze of the Soviet authorities. The insistence that ‘amoral’ people would not receive the free medical treatment to which other Soviet citizens were entitled reflected the broader currents of the Soviet welfare system. The right and duty to work remained the pillar of social policy throughout the entire Soviet period and insurance coverage was conditional on adherence to specific behavioural principles (Galmarini-Kabala Citation2016, pp. 222–23). Representatives of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR broadly agreed with the Latvian Council of Minister’s proposals, but they did not approve the draft decree on the basis that the issue needed to be resolved at a union-wide level, rather than within just one specific republic.Footnote29

In the 1970s, a series of all-union legislative changes expanded the activities for which an individual could be punished under the anti-VD law. In October 1971, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR instructed republican presidiums to change the wording of their anti-VD laws to increase criminal liability for those who contributed to the spread of VD.Footnote30 The evasion of VD treatment became a criminal offence punishable by a one-year prison sentence or a fine of 100 rubles. Evasion included a wide range of activities, from non-attendance at the hospital to any violation of hospital rules, such as the consumption of alcohol or narcotics on hospital premises. The police were given the power to forcibly deliver those who evaded treatment to VD clinics and hospitals. The sentence for deliberately infecting another person remained three years but was extended to five years for infecting more than two people. Two years later, in 1973, the USSR’s Supreme Court issued a new set of instructions regarding judicial practice in the case of VD transmission. They confirmed that in order to prosecute somebody, the court had to prove that the person had deliberately transmitted their infection, but mere awareness of infection was enough proof of motive. Individuals could be prosecuted for a wide range of activities that led to infection, as any violation of the ‘hygienic rules of behaviour in the family, at home, and at work’ which put people in danger of contracting VD was punishable by law.Footnote31

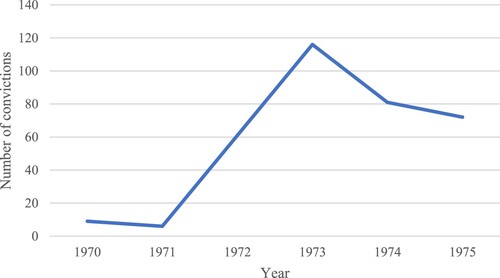

Prosecutors in the Latvian republic took these calls for the increased prosecution of those who transmitted VD extremely seriously. Incidence of VD had been steadily increasing in the Latvian SSR: between 1967 and 1973, incidence of gonorrhoea doubled and syphilis increased 36 times over, and by 1973 incidence of syphilis was almost four times higher than the all-union average.Footnote32 Between 1970 and 1975, the number of people convicted under the republic’s anti-VD law (Article 112 of the Latvian SSR’s Criminal Code) increased by over 2,000%, as can be seen in .Footnote33

FIGURE 1. Number of Convictions under the Latvian SSR’s Anti-VD Law, 1970–1975

Note: Report compiled by L. V. Sazanova, senior researcher at the Central Institute of Skin and Venereal Diseases. Sazanova was instructed to assess the work of dermato-venereological institutions in the Latvian SSR in ‘implementing legislation with the aim of struggling with VD’.

Source: GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, ll. 27–9.

VD clinics across the Latvian SSR were encouraged to collaborate closely with law enforcement to help increase the number of individuals prosecuted under the anti-VD law. These institutions regularly held seminars, conferences and open days for physicians and nurses to share best practice in the fields of dermatology and venereology, as well as to discuss the organisation of the ‘struggle with VD’ at a local level. At the Liepāja skin and VD dispensary open day in October 1978, there was a specific seminar on the application of Article 112 for individuals who evaded treatment or were likely to infect others.Footnote34 The seminar plan revealed a blueprint for dealing with individuals who evaded treatment. First, the suspected transmitter was summoned by the clinic, after which they submitted a written account, along with the victim. A doctor had to confirm that the individual was evading treatment before they could be sent to the police.Footnote35 To make an example of those who evaded treatment, a ‘demonstration court’ was then supposed to be held at the hospital, after which their name was added to a blackboard entitled ‘They are convicted’. In order for a clinic to be awarded the highly coveted title of a ‘school of excellence’ (shkola peredovogo opyta) from the Latvian Ministry of Health, all these steps had to be taken.Footnote36 Between 1974 and 1975, the Latvian republic’s main VD treatment facility held eight demonstration trials.Footnote37 The use of public shaming as a deterrent for disease transmission reveals the centrality of social control to efforts to prevent the spread of venereal infection.

This push for greater criminal liability for transmitters of VD across the USSR fits with wider patterns of criminal procedure under Khrushchev and Brezhnev. After gaining power, Khrushchev initiated legal reform, including diminishing the role of party officials in courts, abolishing the courts of the secret police, and improving the work of prosecutors, judges and lawyers (Moyal Citation2010). This rejection of Stalinist-era terror in favour of ‘socialist legality’ was a key tenet of the process of moving away from Stalinist arbitrary justice. The ambitious premise of socialist legality rested on the assumption that more thorough investigations would prevent the unjust arrest of innocent citizens and simultaneously ensure the conviction of each person brought to trial (Moyal Citation2010, pp. 111–12). Following Khrushchev’s removal as leader and replacement by Brezhnev in 1964, state priorities were reoriented more directly towards retribution. The police and the courts were under pressure from the Party to open more criminal cases, secure more convictions, and mete out harsh sentences (Shelley Citation1996, p. 160; Alexander Citation2019, pp. 14–5). At a meeting of the Bureau of the Communist Party of the Latvian SSR held on 4 March 1973, the republic’s Chief Prosecutor and Ministry of Justice were accused of lacking patriotism for not convicting enough people under the anti-VD law.Footnote38 In the mid-1970s, the All-Union Criminal Investigative Department (Upravlenie ugolovnogo rozyska SSSR) championed the increase in the number of people sentenced for transmitting VD across the USSR but continued to insist on the need for more convictions.Footnote39

Article 112 inscribed the right of medical professionals to forcefully examine individuals suspected to have transmitted VD, as well as suspected sources of infection or people believed to have been in close contact with an infected person, known simply as ‘contacts’ (kontakty). Medical staff were under enormous pressure to identify and eliminate sources of infection and contacts and faced verbal abuse by representatives of the Ministry for Health if they failed to do so (Lipša Citation2019, pp. 98–9). In 1979, one of the targets (known as ‘collective socialist obligations’) of the Latvian republic’s main VD clinic was to identify at least three contacts for each gonorrhoea and syphilis patient.Footnote40 Police and medical workers collaborated to conduct compulsory examinations of individuals found at sobering-up stations (vytrezviteli, medical facilities controlled by the police where people found to be drunk in public would be sent), receiver-distribution centres (temporary places of detention for juvenile offenders) and during brothel raids, in order to root out sources of infection and contacts.Footnote41 In 1975, the police delivered 184 people from such locations to the Latvian SSR’s main VD clinic for observation.Footnote42 The decision to conduct medical examinations in sobering-up stations, correctional facilities and suspected brothels reveals prejudices regarding the kind of people who contracted VD, largely presumed by the authorities to be the antithesis of the ideal Soviet person: drunks, criminals, sex workers and juvenile delinquents.

Venereal diseases as antisocial illnesses

The push for the criminalisation of transmitters underlined the official perception that VD was spread primarily by individuals engaged in antisocial or ‘аmoral’ activities. In audits of judicial procedure across the USSR, the crime of infecting another person with VD was grouped together with other sexual offences, including sodomy and committing ‘depraved acts with a minor’.Footnote43 In March 1973, the Latvian Ministry of Internal Affairs claimed in a secret letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Latvia that the main reason for the increase of VD was the ‘moral promiscuity of individual citizens and prostitution’.Footnote44 The Latvian republic was apparently a magnet for ‘аmoral’ individuals as it was a popular destination for labour migration and tourism. The Ministry of Internal Affairs claimed that a ‘substantial number’ of migrant workers from Moldova and Ukraine who had arrived in Latvia to clear windfall timber from forests between 1967 and 1969 were infected with VD and had received previous convictions for ‘leading аmoral lifestyles’.Footnote45 The seaside town of Jūrmala, a popular tourist centre from the late 1950s, was also plagued with ‘loose women’ (zhenshchiny legkogo povedeniya, a synonym for sex workers) and homosexual men who allegedly moved there en masse each summer from Rīga to take advantage of holidaymakers.Footnote46 Police superintendents in Rīga compiled a photographic register of known sex workers, pimps, brothel keepers and homosexual men for the purpose of ‘identifying sources of VD and solving crimes’.Footnote47 Those on the social margins, such as migrant workers, sex workers and gay men, were convenient scapegoats for officials seeking to assign blame for the spread of VD outside respectable Soviet society, or even outside the republic.

Health authorities also tended to place blame for VD transmission on ‘аmoral’ or antisocial individuals. In 1972, the Latvian republic’s Ministry of Health established four operational groups in Rīga, Liepāja, Daugavpils and Valmiera for the rapid identification of sources of VD and their prompt delivery at clinics for treatment. Each group was comprised of a venereologist, two paramedics or epidemiological specialists, and one driver. Operational groups were instructed to bring people known to be living ‘an аmoral parasitic way of life’, as well as those who had been detained during brothel raids or found in sobering-up centres, directly to observational departments at VD treatment centres.Footnote48 Between 1973 and 1975, 9,333 people were brought into the observational department at a Rīga treatment facility and just under 46% were found to be actually infected.Footnote49 The fact that most suspected sources turned out to be healthy suggests that individuals were targeted because of their engagement in ‘аmoral’ or antisocial behaviour rather than evidence that they were actually infected. Statistics on individuals delivered to a Rīga treatment facility included information about whether the person in question suffered from chronic alcoholism, whether they had a ‘psychological disease’, or if they had a previous criminal conviction.Footnote50 The gathering of this information further illustrates deep-rooted assumptions about the type of people who became infected and spread VD, as well as the connections between perceived sexual misconduct and other forms of social danger in the official imagination (Healey Citation2001, pp. 184–90; Stella Citation2015, pp. 34–5).

Medical workers at Latvia’s largest treatment facility (the Republican VD Dispensary at 70 Pērnavas iela, Rīga) claimed that every single VD patient had a large number of sexual partners, sometimes more than 25, which made it difficult to conduct contact tracing. We do not know whether this figure was exaggerated by medical workers to fit with official narratives that cast casual sex and ‘аmoral behaviour’ as key causes of venereal infection, or to explain their failure to locate sources of infection or contacts. In 1974–1975, sources of infection were identified for just 70% of syphilis patients and only 39% of gonorrhoea patients across Latvia.Footnote51 Similarly low success rates for tracing sources of infection and contacts were observed in other regions of the USSR, such as Leningrad, Saratov and Voronezh, as well as the Estonian and Lithuanian SSRs.Footnote52 Perhaps VD patients gave the names of multiple sexual partners to clinic staff to prevent contact tracing, as they recognised that the health authorities did not have the facilities, personnel or even the strong desire to search for dozens of people. Gay men and sex workers may have used aliases or remained anonymous to sexual partners in order to prevent themselves from being traced, as exposure had the potential to lead to criminal prosecution for sodomy or parasitism.

Records from the Republican VD Dispensary in Rīga challenge stereotypes about VD patients as antisocial ‘types’. In 1974, just 37% of suspected sources of infection delivered to the facility by the police were classified as unemployed and without a permanent place of residence, and just 27% in 1975.Footnote53 Of the 1975 group, only 7% were identified as ‘chronic alcoholics’ and a quarter had previous criminal convictions. In other cities of the Soviet Union, almost all VD patients were engaged in ‘socially useful labour’ within a state-owned industry.Footnote54 Indeed, just under half of the people convicted under the anti-VD law in the RSFSR in 1973 were engaged in state-sanctioned labour.Footnote55 Research conducted by the Latvian Ministry for Health and Internal Affairs in the mid-1970s also found that VD was not primarily spread by people living ‘аmoral and parasitic lifestyles’ but through ordinary people engaging in extramarital affairs and casual sexual encounters (Lipša Citation2019, p. 114).

Stereotypes about antisocial and аmoral transmitters of infection were repeated in sex education. As in other international contexts, Soviet sex education both served to educate citizens about how to avoid catching an infection and to delineate the boundaries of socially acceptable sexual behaviour (Sauerteig & Davidson Citation2009). As noted earlier, Stalinist-era silence on issues related to sex and sexuality was broken in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and sex became ‘subject to communist morality and thus a matter of official and expert discussion’ (Field Citation2007, pp. 51–4; Alexander Citation2018c). In the 1960s and 1970s, the Soviet leadership embraced mass media as a method for communicating ideas about sexual hygiene and behaviour. Medical professionals in Latvia prepared articles for publication in local Latvian- and Russian-language newspapers.Footnote56 In the early 1970s, the Latvian Minister for Health took advantage of the surge in television and radio ownership and organised regular radio broadcasts on the dangers of VD and monthly screenings of sexual health films on television.Footnote57 These developments made information about symptoms of VD and sexual morality available in the homes of Soviet citizens with increasing frequency.

Soviet sex education was saturated in the ethos of communist morality and expressed strong opposition to sexual acts, such as masturbation, homosexual sex and sex outside marriage, that allegedly endangered the collective by reducing labour reserves, encouraging irresponsibility, fracturing family relationships and impeding procreation (Alexander Citation2018c). In anti-VD materials, casual sex in particular was demonised as an activity infused with potent danger. Newspaper articles prepared for publication included case studies of VD patients (either real or fictitious, there is no way of knowing) whose engagement in casual sex ruined their entire lives. There was Leonid V., a promising athlete on his way to becoming a record holder who cut his career short by engaging in casual sex with one of his ‘admirers’, catching gonorrhoea and leaving it untreated for several months.Footnote58 Darisa T., ‘succumbed to a fleeting desire’ with an acquaintance while her husband was out of town, which resulted in gonorrhoea, syphilis, infertility and divorce.Footnote59 A Latvian-language radio broadcast from 20 August 1974 insisted that abstaining from casual sex, alcohol and drugs was ‘the only safe way’ to avoid contracting syphilis and gonorrhoea.Footnote60 Unlike the stereotypes of the antisocial ‘bad apples’ discussed earlier, these VD patients were ordinary Soviet citizens who let their morals slip and suffered the consequences. By using relatable characters, these stories emphasised the danger posed to even ‘respectable’ Soviet citizens by any deviations from communist morality.

Sex education materials stressed the importance of receiving treatment only from a medical professional employed within a state facility, a message that would presumably aid the state in its efforts to trace contacts and sources of infection. Those who self-medicated or received private treatment avoided the gaze of the authorities and sidestepped potentially awkward conversations with physicians about their number of sexual partners and the importance of adhering to standards of communist morality. Public lectures and newspaper articles warned that individuals who bought antibiotics from unofficial channels risked contracting multiple other venereal infections or even death.Footnote61 Despite this, some sex education materials disincentivised seeking treatment by presenting a trip to a VD clinic as an unpleasant encounter. The film Reportage without Heroes (Reportazh bez geroev), screened first in 1973, began with a candid camera being installed within a VD dispensary, a device employed to lead viewers to believe that they were observing genuine patients in conversation with a doctor. True to the ethos of community morality, patients in the film had engaged in casual or extramarital sex with disastrous consequences. Doctors explained the law on VD transmission to insolent young people who dismissed the severity of their infections and even presented them with images of adults and babies with syphilitic lesions. Patients were asked to name the sources of their infection and contacts, to which one man replied, ‘My wife will never forgive me’. The final patient in the film was a married man accused of infecting women across the Soviet Union while away on business trips. The man began to tell the doctor that his ‘intimate life’ was none of her business when she interrupted him: ‘No, you listen. You are socially dangerous. You are the source of infection for many women … . What fate awaits your unborn child?’. Patients were informed of the apparent common misconception that VD treatment was straightforward, and moralising language permeated the doctor–patient consultation. Rather than encouraging people to go to their local VD dispensary when they noticed signs of infection, films like this reinforced the stigma and shame associated with VD and likely acted as a disincentive to seeking treatment through official channels.

As well as disincentivising treatment, there were other crucial issues that had an impact on rising rates of VD infection. Throughout the early 1970s, serological laboratories across the Latvian SSR were unable to adequately conduct the Wassermann reaction (a blood test for the detection of syphilis) as they did not have access to the required antigens.Footnote62 There were also chronic shortages in the number of beds for VD patients across the Soviet Union, and the Latvian republic was no exception.Footnote63 At a 1973 meeting of the Bureau of the Communist Party of the Latvian SSR, the Minister of Internal Affairs claimed that VD clinics across the republic had been sending patients away due to lack of space.Footnote64 The chairman of Rīga’s Central Executive Committee and the Secretary of the Central Committee explained that the number of beds available for VD patients was not sufficient for the republic’s population. Plans to rectify this problem focused exclusively on increasing capacity at the Republican VD Dispensary in Rīga.Footnote65 This treatment facility had over 200 beds for VD patients, but the majority of people receiving treatment there were not Rīga residents, which suggests that people either had to travel to the republic’s capital in order to receive treatment or preferred to do so as their local treatment facilities were inadequate. Between 1978 and 1982, an average of 84% of patients at the Republican Dispensary had travelled from outside Rīga.Footnote66 Even if a patient was able to travel to Rīga, treatment for VD was slow. In 1975, the average stay for a gonorrhoea patient in a Rīga venereal clinic was 38.4 days, and penicillin treatment for syphilis patients was between 50 and 450 days, depending on the stage of the infection.Footnote67 Here, the duration of VD treatment was much longer than in other international contexts. The length of hospital stays decreased for VD patients in the United States and East Germany after the end of World War II due to the introduction of penicillin and the development of new treatment procedures (Brandt Citation1987, p. 170; Schochow Citation2019, pp. 148–49). In contrast, prolonged hospitalisation appears to have been the preferred treatment in Rīga, arguably driven by the desire to ensure patient compliance with treatment regimes and the more general fetishisation of hospital stays within the Soviet healthcare system (Feshbach Citation1988, p. 128; Rowland & Telyukov Citation1991, pp. 82–3). Prolonged hospitalisation, plus the need to travel to receive adequate care and the criminalisation of disease transmission, would have likely acted as disincentives to seeking treatment through the state healthcare system, which likely caused increased levels of infection.

Structural issues also impeded official attempts to enforce the treatment of ‘аmoral’ individuals and ‘malicious’ transmitters of VD. The Republican VD Dispensary in Rīga had a special section that was guarded by two police officers who were responsible for dealing with people who ‘maliciously evade[d] VD treatment’ and ensuring order within the hospital.Footnote68 Despite this, staff at the dispensary complained that patients within this section drank alcohol and took drugs smuggled in through holes sawn in the wire fences surrounding the treatment centre.Footnote69 Male patients also damaged medical equipment, electrical wiring and the dispensary’s broadcasting radio network, and even broke into the women’s wards. The memoir of one physician working at the dispensary detailed a riot in the women’s wards, in which female patients attacked and sexually assaulted the chief physician on night duty (Lipša Citation2019, p. 102). Patients were not the only problem. One doctor at the Republican Dispensary was repeatedly disciplined for being drunk at work and turning a blind eye to patients’ alcohol consumption.Footnote70 The same doctor was also part of a ring of medical personnel within the dispensary who issued fraudulent incapacity to work certificates to former patients so that they could receive state benefits.Footnote71

Staffing issues were not unique to the Latvian republic. In the RSFSR throughout the 1970s, many regional ‘closed’ VD treatment centres (institutions where individuals would undergo forced treatment) were not guarded by law enforcement because the local authorities were unable to provide accommodation for police officers, or merely because the facilities lacked external fences.Footnote72 Similar problems persisted into the 1980s, when many closed centres still did not have fences, telephones, outdoor lighting or adequate accommodation for police officers.Footnote73 Medical personnel in Arkhangel’sk complained that patients escaped from the closed centre, insulted and abused the staff, forged keys and even smuggled in knives.Footnote74 In 1984, the USSR’s Ministry of Health acknowledged that they struggled to find police officers who would guard closed venereal centres because so many despised working in these facilities, and vowed to petition the USSR’s Council of Ministers to request higher salaries for officers who were willing to provide security.Footnote75

Finally, a chronic lack of adequate barrier contraception impeded official efforts to reduce rates of venereal infection. Throughout the Brezhnev era, there were widespread condom (and diaphragm) shortages and abortion remained one of the most common methods of birth control (Field Citation2007, pp. 61–5; Denisova Citation2013, pp. 181–82; Nakachi Citation2016). In the mid-1970s, data from the Ministry of Health revealed that the supply of condoms available in the USSR did not satisfy the needs of the majority of the population (Popov et al. Citation1993, pp. 231–32). This trend continued into the next decade. For example, in February 1989, the Estonian SSR’s People’s Control Committee reported that the Estonian republic’s condom supply could only provide each adult man with 2.5 condoms per year.Footnote76 The most commonly used contraceptive methods for married couples in the Soviet Union (induced abortion, the withdrawal method, the use of a menstrual calendar and vaginal douching) may have terminated or prevented pregnancy in some cases, but they did not offer any protection against VD (Popov et al. Citation1993, p. 229; Remennick Citation1993, pp. 45–6).Footnote77 The quality of barrier methods such as condoms available in the USSR was also poor and usage remained low throughout the entire Soviet period (Rankin-Williams Citation2001, p. 700; Hilevych & Sato Citation2018).

Conclusion

In the long postwar era, state approaches to preventing the spread of VD shifted in line with broader renegotiations of the relationship between the Soviet regime and its citizens. A series of policy shifts initiated under Khrushchev blurred the boundaries between public and private, which meant that the sexual lives and sexual health of Soviet citizens were subject to increased state intervention. VD transmission was reinterpreted as antisocial and immoral behaviour amid rising concern about morality and deviance following the scaling back of the Gulag system from the mid-1950s onwards.

The Brezhnev era was characterised by significant shifts in state policies towards sex and sexuality, especially in the arena of VD control. The category of a ‘malicious’ transmitter of VD expanded significantly and criminal law became the preferred solution for preventing the spread of infection. The more decisive focus on the criminalisation of disease transmission throughout the 1970s reflected the reorientation of state priorities towards retributive punishment. At the same time, the idea that VD was spread exclusively through engagement in antisocial or ‘amoral’ activities was pushed in sex education materials. A surge in television and radio ownership in the late 1960s and early 1970s meant that these ideas were beamed into the homes of Soviet citizens with increasing frequency.

The potent combination of the criminalisation of infection, the moral judgement of those who became infected with VD, the poor quality of barrier contraceptives and the promotion of abstinence or sex within marriage as methods for preventing infection likely contributed to widespread VD in the Soviet Union. In spite of this, Soviet leadership at the union-wide and republican levels largely ignored the inadequacy of treatment facilities and prioritised the use of coercive measures to prevent the transmission of VD. The government claimed that even the loftiest official goals, such as the complete eradication of VD, were attainable through following complex, ‘scientific’, interdepartmental plans to the letter. In the case of failure, apathetic or antisocial individuals were to blame rather than structural problems. When Soviet politicians discussed transmitters of infection, they spoke in the language of antisocial behaviour, immorality and parasitism that had become popularised in the Khrushchev era. Speaking the ‘familiar Soviet discourse of blame, which ascribed systematic failures to individual inadequacies’, politicians claimed that VD was predominantly spread by people on the fringes of Soviet society, meaning those who refused to participate in so-called ‘socially useful labour’ or adhere to norms of communist morality (Field Citation2007, p. 63).

The trends that began in the 1960s and 1970s continued throughout the remaining years of the USSR and beyond. The classification of VD transmission as antisocial behaviour in the early 1960s significantly influenced state approaches to HIV during the global epidemic of the late 1980s. The first case of HIV was reported in the Soviet Union in 1987 and the disease was immediately classified as one spread exclusively through promiscuous sex and ‘deviant’ behaviour. In 1987, 16 young physicians wrote to the Soviet AIDS Research Group claiming that AIDS was a useful tool for cleansing society of ‘unsavoury’ individuals, such as drug users and sex workers, and insisting that AIDS patients ought to be refused treatment (Feshbach Citation2007, p. 8). Much like their approach to VD, the Soviet leadership’s methods for preventing the spread of HIV were characterised by surveillance and social control. An August 1987 decree included HIV in the Soviet Union’s anti-VD law, with a maximum of eight years’ imprisonment for deliberate infection. HIV patients who refused to follow strict regulations or who were deemed a public health danger could be kept in quarantine within medical institutions for an unspecified period of time (Pape Citation2014, pp. 72–3).

The stigmatisation of individuals with HIV, combined with fear of being accused of deliberately infecting another person, likely acted as a significant disincentive for seeking treatment. To make matters worse, barrier contraceptives remained in short supply throughout the 1980s. Deficiencies within the Soviet healthcare system and the failure of the government to allocate sufficient funds for medical equipment and supplies also undoubtedly contributed to widespread infection (Feshbach Citation2007, pp. 20–5; Pape Citation2014, p. 72). Despite this, no lessons have been learnt about the impact of stigmatisation and criminalisation on the spread of infection. In the present day, as the HIV epidemic continues to worsen in the Russian Federation, both VD and HIV transmission remain criminalised (Sizov & Zavalishina Citation2015; Hurley Citation2018) and experts agree that official figures grossly underreport the true number of infections in both cases (Vladimirova et al. Citation2019; Gómez & Kucheryavenko Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siobhán Hearne

Siobhán Hearne, School of Modern Languages & Cultures, Durham University, Durham, UK. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (hereafter GARF), f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4265, l. 160.

2 Latvijas Nacionālais arhīvs, Latvijas Valsts arhīvs (hereafter LVA), f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 77–8. In the period 1970–1973, rates of syphilis in the Latvian SSR were double those of the RSFSR and rates of gonorrhoea were almost 1.5 times higher. GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 24; GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 4715, ll. 61–2.

3 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 111.

4 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 111.

5 Ugolovnyi kodeks RSFSR (Moscow, Izdanie voennoi kollegii verkhovnogo tribunala VTsIK, 1922, p. 18).

6 VD transmission was criminalised in Yugoslavia in the 1951 Criminal Code, ‘Krivični zakonik’, Službeni list Federativne Narodne Republike Jugoslavije, no. 13, 9 March 1951. With thanks to Ivan Simić for providing me with this reference.

7 Kalnbērzs was born in Moscow but completed his medical training in the Latvian SSR. His memoir has been published in Latvian: Mans laiks (Rīga, Mеdicīnas apgāds, 2013) and Russian: Moe vremya (Rīga, Mеdicīnas apgāds, 2015).

8 For statistics for 1940, 1943 and the first half of 1945 in major cities of the USSR, see GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 23.

9 GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 36.

10 GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 6.

11 GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 7.

12 GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 46.

13 GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 47.

14 Vilnius sent such a report to Moscow by telegram in September 1945, GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, l. 20.

15 GARF, f. R5446, op. 47, d. 2102, ll. 30, 32.

16 LVA, f. 1022, apr. 7, l. 34, lp. 52.

17 LVA, f. 1022, apr. 7, l. 34, lp. 52–3.

18 The only comparative study on interwar and Soviet Latvia is Lūse (Citation2010). Research has been conducted on specific aspects of the Latvian healthcare system and healthcare policies in the 1920s and 1930s (Felder Citation2013; Lipša Citation2014, pp. 457–68).

19 Jewish students made up a sizeable minority of the University of Latvia’s medical faculty in the 1920s (Bolin Citation2012, pp. 137–40). Ninety-one percent of Latvia’s Jewish population were killed during the Holocaust (Ezergailis Citation1996, p. 203). On the emigration of medical professionals, see Pabriks and Purs (Citation2001, p. 32) and Lauze et al. (Citation2018, pp. 182–84).

20 LVA, f. 1022, apr. 7, l. 116, lp. 1–3.

21 Advanced training for dermato-venereologists only became possible within the Latvian republic in 1982. The most prominent positions within the Latvian SSR’s dermato-venereological service were occupied by doctors who had completed their training in the major cities of the USSR (Miltiņš Citation1933, pp. 96–8).

22 LVA, f. 1022, apr. 7, l. 90, lp. 11–2, 14.

23 LVA, f. 1022, apr. 7, l. 116, lp. 32.

24 Prikaz Ministerstvo Zdravookhraneniya SSSR ot 27/02/1963 ‘O meropriyatiyakh po likvidatsii zabolevaemosti sifilisom i rezkomu snizheniyu gonorei v sssr’.

25 GARF, f. R7523, op. 83, d. 1298, l. 1.

26 GARF, f. R7523, op. 83, d. 1298, l. 2.

27 GARF, f. R7523, op. 83, d. 1298, ll. 2–3.

28 GARF, f. R7523, op. 83, d. 1298, l. 8.

29 GARF, f. R7523, op. 83, d. 1298, l. 8.

30 GARF, f. R7523, op. 106, d. 922, l. 1.

31 Postanovlenie plenuma verkhovnogo suda SSSR 8/10/1973, ‘O sudebnoi praktike po delam o zarazhenii venericheskoi bolezn’yu’.

32 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 79; GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 30.

33 On the relationship between federal laws and republican criminal articles in the USSR, see Nikiforov (Citation1960). Article 112, the Latvian SSR’s anti-VD law, can be found in Latvijas Padomju Sociālistiskās Republikas Kriminālkodekss (Rīga, Latvijas valsts izdevniecība, 1961, p. 43).

34 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 23, lp. 67.

35 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 23, lp. 70.

36 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 23, lp. 42.

37 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 18.

38 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 101.

39 GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 5795, l. 2; GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 4715, l. 40.

40 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 8, lp. 24.

41 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 89; GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 7.

42 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 16.

43 For example, see the 1969 audit for the RSFSR in 1969 (GARF, f. A461, op. 12, d. 131) and the union-wide 1975 audit (GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4265).

44 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 80.

45 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 80.

46 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 88.

47 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 87.

48 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 17.

49 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 20.

50 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 17.

51 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4937, l. 71.

52 GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 4716, l. 90; GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 5795, ll. 67–8; GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4937, ll. 52, 146–47; Rahvusarhiiv (hereafter ERAF), 1.20.17, lk. 5.

53 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 17.

54 GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 4716, ll. 8, 70–1, 41. In Moscow, just 19% of syphilis patients were unemployed in 1975; Tsentral'nyi Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Moskovskoi Oblasti (hereafter TsGAMO), f. 7062, op. 7, tom. 1, d. 1024, l. 1.

55 GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 4716, l. 5.

56 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 22, lp. 17, 97.

57 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 22, lp. 69–71, 95, 109, 143. From 1965 to 1970, the number of televisions per Soviet family doubled, from roughly one set per four families to one set per two families (Evans Citation2016, p. 4). On the surge in radio ownership see Lovell (Citation2015, pp. 135–60).

58 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 22, lp. 122.

59 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 22, lp. 124.

60 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 22, lp. 69–71.

61 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 22, lp. 49.

62 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4937, l. 73.

63 In 1974, the target number of beds for VD patients was 3.5 per 10,000 people, yet on average there were only 2.5 per 10,000 across the RSFSR. Even in the Moscow region, there were only 2.0 per 10,000; GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 4716, ll. 4–5, 88; TsGAMO, f. 7062, op. 7, tom. 1, d. 1024, l. 51.

64 LVA, f. PA-101, apr. 37, l. 47, lp. 103.

65 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 1, lp. 1.

66 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 21, lp. 15, 57, 111.

67 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 18.

68 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 16.

69 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4931, l. 18.

70 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 1, lp. 6, 104.

71 LVA, f. 2141, apr. 3, l. 1, lp. 96.

72 This was the case in Izhevsk, Sverdlovsk, Cheliabinsk, Khabarovsk territory, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskii and Rostov-on-Don; GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 5795, l. 38.

73 GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 5795, ll. 40–2.

74 GARF, f. R8009, op. 50, d. 4265, ll. 131–32.

75 GARF, f. A259, op. 46, d. 5795, l. 40.

76 ERAF, R-2158.13.1325, lk. 7.

77 It is important to note that surveys on contraceptive use predominantly refer to married couples.

References

- Alexander, R. (2018a) ‘Soviet Legal and Criminological Debates on the Decriminalization of Homosexuality (1965–75)’, Slavic Review, 77, 1.

- Alexander, R. (2018b) Homosexuality in the USSR (1956–82), PhD thesis (Melbourne, University of Melbourne).

- Alexander, R. (2018c) ‘Sex Education and the Depiction of Homosexuality Under Khrushchev’, in Ilič, M. (ed.) The Palgrave Handbook of Women and Gender in Twentieth-Century Russia and the Soviet Union (London, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Alexander, R. (2019) ‘New Light on the Prosecution of Soviet Homosexuals Under Brezhnev’, Russian History, 46, 1.

- Anderson, B. A. & Silver, B. D. (2000) ‘Growth and Diversity of the Population of the Soviet Union’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 511.

- Barański, P. (2012) ‘Walka z chorobami wenerycznymi w Polsce w latach 1948–1949’, in Kula, M. (ed.) Kłopoty z seksem w PRL. Rodzenie nie całkiem po ludzku, aborcja, choroby, odmienności (Warsaw, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego).

- Bell, W. T. (2015) ‘Sex, Pregnancy, and Power in the Late Stalinist Gulag’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, 24, 2.

- Bernstein, F. (2011) The Dictatorship of Sex: Lifestyle Advice for the Soviet Masses (DeKalb, IL, Northern Illinois University Press).

- Bernstein, F., Burton, C. & Healey, D. (2010) ‘Introduction’, in Bernstein, F., Burton, C. & Healey, D. (eds) Soviet Medicine: Culture, Practice and Science (DeKalb, IL, Northern Illinois University Press).

- Blom, I. (2006) ‘Fighting Venereal Diseases: Scandinavian Legislation c. 1800 to c. 1950’, Medical History, 50, 2.

- Bolin, P. (2012) Between National and Academic Agendas: Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 (Huddinge, Södertörns högskola).

- Brandt, A. M. (1987) No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880 (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Cohn, E. (2009) ‘Sex and the Married Communist: Family Troubles, Marital Infidelity, and Party Discipline in the Postwar USSR, 1945–1964’, Russian Review, 68, 3.

- Cohn, E. (2015) The High Title of a Communist: Postwar Party Discipline and the Values of the Soviet Regime (DeKalb, IL, Northern Illinois University Press).

- Cohn, E. (2018) ‘A Soviet Theory of Broken Windows: Prophylactic Policing and the KGB’s Struggle with Political Unrest in the Baltic Republics’, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 19, 4.

- Conroy, M. S. (2004a) ‘The Soviet Pharmaceutical Industry and Dispensing, 1945–1953’, Europe-Asia Studies, 56, 7.

- Conroy, M. S. (2004b) ‘Russian–American Pharmaceutical Relations, 1900–1945’, Pharmacy in History, 46, 4.

- Conroy, M. S. (2008) Medicine for the Soviet Masses During World War II (Lanham, MD, University Press of America).

- Denisova, L. (2013) Rural Women in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Russia (London & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Dobson, M. (2009) Khrushchev’s Cold Summer: Gulag Returnees, Crime, and the Fate of Reform after Stalin (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Evans, C. E. (2016) Between Truth and Time: A History of Soviet Central Television (New Haven, CT, Yale University Press).

- Ezergailis, A. (1996) The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941–1944: The Missing Centre (Rīga, Historical Institute of Latvia).

- Fainberg, D. & Kalinovsky, A. M. (2016) ‘Stagnation and its Discontents: The Creation of a Political and Historical Paradigm’, in Fainberg, D. & Kalinovsky, A. M. (eds) Reconsidering Stagnation in the Brezhnev Era: Ideology and Exchange (Lanham, MD, Lexington Books).

- Felder, B. M. (2013) ‘“God Forgives—But Nature Never Will”: Racial Identity, Racial Anthropology, and Eugenics in Latvia, 1918–1940’, in Felder, B. M. & Weindling, P. J. (eds) Baltic Eugenics: Bio-Politics, Race and Nation in Interwar Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (Amsterdam, Rodopi).

- Feshbach, M. (1988) ‘Health in the U.S.S.R.: Organization, Trends, and Ethics’, in Sass, H. M. & Massey, R. U. (eds) Health Care Systems: Moral Conflicts in European and American Public Policy (Dordecht, Springer).

- Feshbach, M. (2007) ‘The Early Days of the AIDS Epidemic in the Former Soviet Union’, in Twigg, J. L. (ed.) HIV/AIDS in Russia and Eurasia, vol 1 (New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Field, D. A. (2007) Private Life and Communist Morality in Khrushchev’s Russia (New York, NY, Peter Lang).

- Filtzer, D. (2017) ‘Factory Medicine in the Soviet Defence Industry During World War II’, in Grant, S. (ed.) Russian and Soviet Health Care from an International Perspective: Comparing Professions, Practice, and Gender, 1880–1960 (London, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Fitzpatrick, S. (2006) ‘Social Parasites: How Tramps, Idle Youth, and Busy Entrepreneurs Impeded the Soviet March to Communism’, Cahiers du monde russe, 47, 1–2.

- Fürst, J. (2017) ‘Introduction: To Drop or Not to Drop?’, in Fürst, J. & McLellan, J. (eds) Dropping Out of Socialism: The Creation of Alternative Spheres in the Soviet Bloc (Lanham, MD, & London, Lexington Books).

- Galmarini-Kabala, M. C. (2016) The Right to Be Helped: Deviance, Entitlement, and the Soviet Moral Order (DeKalb, IL, Northern Illinois University Press).

- Gómez, E. J. & Kucheryavenko, O. (2021) ‘Explaining Russia’s Struggle to Eradicate HIV/AIDS: Institutions, Agenda Setting, and the Limits to Multiple-Streams Processes’, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 23, 3.

- Harrison, M. (2005) ‘Why Didn’t the Soviet Economy Collapse in 1942?’, in Chickering, R., Förster, S. & Greiner, B. (eds) A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1939–1945 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Hazanov, A. (2016) Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors and the Post-Stalin Soviet State, PhD thesis (Philadelphia, PA, University of Pennsylvania).

- Healey, D. (2001) Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago, IL, Chicago University Press).

- Healey, D. (2014) ‘The Sexual Revolution in the USSR: Dynamics Beneath the Ice’, in Hekma, G. & Giami, A. (eds) Sexual Revolutions (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Healey, D. (2018) Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London, Bloomsbury).

- Hearne, S. (2017) ‘The “Black Spot” on Crimea: Venereal Diseases in the Black Sea Fleet in the 1920s’, Social History, 42, 2.

- Hilevych, Y. & Sato, C. (2018) ‘Popular Medical Discourses on Birth Control in the Soviet Union during the Cold War: Shifting Responsibilities and Relational Values’, in Gembries, A., Theuke, T. & Heinemann, I. (eds) Children by Choice? Changing Values, Reproduction, and Family Planning in the 20th Century (Berlin, De Gruyter).

- Hornsby, R. (2013) Protest, Reform and Repression in Khrushchev’s Soviet Union (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Hurley, R. (2018) ‘Criminalising HIV Transmission is Counterproductive and Should Stop, Experts Say’, British Medical Journal, 362, 3261.

- Ilič, M., Reid, S. E. & Attwood, L. (eds) (2004) Women in the Khrushchev Era (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Ironside, K. (2017) ‘Between Fiscal, Ideological, and Social Dilemmas: The Soviet “Bachelor Tax” and Post-War Tax Reform, 1941–1962’, Europe-Asia Studies, 69, 6.

- Kon, I. S. (1995) The Sexual Revolution in Russia: From the Age of the Czars to Today (New York, NY, The Free Press).

- LaPierre, B. (2006) ‘Making Hooliganism on a Mass Scale: The Campaign Against Petty Hooliganism in the Soviet Union, 1956–1964’, Cahiers du monde russe, 47, 1–2.

- LaPierre, B. (2012) Hooligans in Khrushchev’s Russia: Defining, Policing, and Producing Deviance During the Thaw (Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Press).

- Lauze, S., Maurina, B. & Sidlovska, V. (2018) ‘The Impact of the Baltic Germans’ Emigration on the Pharmaceutical Sector in Latvia’, Pharmazie, 73.

- Leps, A. (1991) ‘Comparative Analysis of Crime: Estonia, the Other Baltic Republics, and the Soviet Union’, International Criminal Justice Review, 1, 1.

- Lipša, I. (2014) Seksualitāte un sociālā kontrole Latvijā, 1914–1939 (Rīga, Zinātne).

- Lipša, I. (2019) ‘Categorised Soviet Citizens in the Context of the Policy of Fighting Venereal Disease in the Soviet Latvia from Khrushchev to Gorbachev (1955–1985)’, Acta medico-historica Rigensia, 12.

- Loader, M. (2015) The Thaw in Soviet Latvia: National Politics 1953–1959, PhD thesis (London, Kings College London).

- Loader, M. (2017) ‘Restricting Russians: Language and Immigration Laws in Soviet Latvia, 1956–1959’, Nationalities Papers, 45, 6.

- Lovell, S. (2015) Russia in the Microphone Age: A History of Soviet Radio, 1919–1970 (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Lunderberg, A. (2008) ‘Paying the Price of Citizenship: Gender and Social Policy on Venereal Disease in Sweden, 1919–1944’, Social Science History, 32, 2.

- Lūse, A. (2010) ‘From Social Pathologies to Individual Psyches: Psychiatry Navigating Socio-Political Currents in 20th-Century Latvia’, History of Psychiatry, 22, 1.

- Miltiņš, A. P. (1993) ‘Vliyanie vostoka i zapada na razvitie dermatovenerologii Latvii’, in 17th Baltic Conference on the History of Science: Baltic Science Between the West and the East, Tartu, 4–6 October.

- Moyal, D. (2010) Did Law Matter? Law, State, and Individual in the USSR, 1953–1982, PhD thesis (Stanford, CA, Stanford University).

- Nakachi, M. (2006) ‘N. S. Khrushchev and the 1944 Soviet Family Law: Politics, Reproduction, and Language’, East European Politics and Societies, 20, 1.

- Nakachi, M. (2011) ‘A Postwar Sexual Liberation? The Gendered Experience of the Soviet Union’s Great Patriotic War’, Cahiers du monde russe, 52, 2–3.

- Nakachi, M. (2016) ‘Liberation without Contraception: The Rise of the Abortion Empire and Pronatalism in Socialist/Post Socialist Russia’, in Solinger, R. & Nakachi, M. (eds) Reproductive States: Global Perspectives on the Invention and Implementation of Population Policy (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Nikiforov, B. S. (1960) ‘Fundamental Principles of Soviet Criminal Law’, Modern Law Review, 23, 1.

- Pabriks, A. & Purs, A. (2001) Latvia: The Challenges of Change (London, Routledge).

- Pape, U. (2014) The Politics of HIV/AIDS in Russia (London, Routledge).