Abstract

Chinese campuses have been remarkably calm since the post-1989 repression. Yet, the absence of contention masks profound changes in the party-state’s campus management tactics, exemplifying the different approaches authoritarian regimes employ to regiment students. Based on fieldwork before and after Xi Jinping’s rise to power (2012), we analyse the party-state’s move from a ‘corporatist’ to a ‘partification’ strategy on campus. Contrary to the literature that sees apathy and depoliticisation as the goal of the party-state’s management of campuses, we argue that these changes reveal the regime’s apprehension about student alienation from official political channels and constitute an effort to reverse it.

In the summer of 2018, a labour dispute at Shenzhen Jasic Technology attracted high-level political attention. The mobilised workers were accused of creating ‘an unregistered illegal organisation’ and engaging in ‘radical actions’. This collective action case was particularly consequential since university students throughout China voiced their solidarity with the workers and established a support group, organising signature collections and fund-raising campaigns. Among these students, the Marxist Studies Association at Peking University, one of the country’s elite institutions, was very active in supporting the Jasic workers. The support group was eventually labelled illegal and dismantled, while the police took away several of its members, including students from Peking University. The Marxist Studies Association was restructured at the end of 2018 by the university’s authorities to ensure it toed the party line (Chan Citation2020).

This anecdote encapsulates the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) fears regarding student political activities, especially students organising themselves outside officially sanctioned channels and building coalitions with other social groups. Student mobilisations have been particularly important in China, from the 1919 demonstrations against the Treaty of Versailles, which led to the emergence of a new generation of politicised students, to the democratic movement of 1989 (Wasserstrom & Liu Citation1995; Lanza Citation2010). Despite this potential for collective action, the People’s Republic of China has been expanding its educational sector as part of its technocratic modernisation drive, counting today close to 3,000 higher education institutions, from just 392 in 1976, and 37 million students (Ministry of Education Citation2017a). The Chinese government has also been investing heavily in the education sector to compete in the global knowledge economy and develop ‘world-class universities’.Footnote1 This essay investigates how the Chinese regime and non-democratic systems more broadly deal with this tension between their willingness to develop a competitive educational sector and the political risk it creates.

University students are a source of anxiety for authoritarian regimes, which fear the growth of a critical intelligentsia (Bueno de Mesquita & Downs Citation2005; Bunce & Wolchik Citation2011; Perry Citation2019). Contributions in this special collection of essays highlight the subversive potential of the student body (see Nikolayenko, this issue) and the impact of transnational links in a globalised context that may prompt young people to rethink the legitimacy of their political institutions (see Krawatzek & Sasse, this issue). Authoritarian regimes develop a variety of control mechanisms to limit student dissent: creating an educational system with clear winners and losers to limit incentives for coalitions (Forrat Citation2015), spreading socially and politically conservative values supporting the political status quo (Perry Citation2017; Schwenck, this issue) or relying on state-led political organisations to mobilise their support (Weiss Citation2014; Silvan Citation2019; Ekiert et al. Citation2020; Nizhnikau & Silvan, this issue). In the Chinese case, since 1989 campuses have appeared exceptionally tranquil and stable, and students have been portrayed as ‘apathetic’ (Yan Citation2014). Far from being a threat to the regime, higher education institutions appear to be a nexus of state support (Perry Citation2019).

How exactly has the Chinese party-state maintained a balance between knowledge production and student autonomy on the one side and state supervision on the other? Is it satisfied with student apathy, or is it looking for a more active engagement? While several studies have stressed the evolution of Chinese higher education’s structure and content, including its internationalisation (Hayhoe Citation1993; Jain Citation2019), only a few have analysed the control apparatus on campus (Yan Citation2014; Perry Citation2019). These analyses have greatly enriched our understanding of on-campus controls yet, focusing mainly on the period between the Tiananmen student mobilisations and Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012, they cannot account for recent changes in student management that counter the idea that students’ political apathy is the party-state’s primary goal. This essay focuses on changes to the management of student societies to study the mechanisms of control developed by authoritarian regimes to limit dissent, and how these mechanisms change over time. While only one facet of political activities and control on campus, student societies are, in essence, potential coordination platforms and hence exemplify the danger of higher education for authoritarian regimes.

Contrary to the view that political apathy is the intended outcome of the regime’s strategy to discourage dissent through a mix of incentives and controls (Yan Citation2014), we find that in recent years the Chinese leadership has become increasingly anxious about students’ disassociation from official politics. It fears that, instead of depoliticisation, apathy might translate into ‘alienation’ from official channels of political participation and increased informal participation, as shown by the example of the Jasic support group. Jeffrey Wasserstrom has shared a characteristic anecdote on how analytical explanations concentrating on ‘apathetic youth’ can be misleading. While in China to research the emerging youth movement just a couple of years before the mass student protests of 1989, he was repeatedly told that it was ‘a dull time for that topic’, since university students ‘were too focused on frivolous things and concerned with getting ahead to engage in any sort of idealist collective action’ (Wasserstrom Citation2015). Journalistic accounts of the Hong Kong protests have also highlighted the rapid transition from ‘apathy’ to activism among university students (Steger Citation2014). The distinction between depoliticisation and alienation is also in line with recent research on political participation in democratic contexts (Cammaerts et al. Citation2014; Dahl et al. Citation2018).

Unveiling the Chinese regime’s anxiety and frustration over students’ apparent apathy, we show that authoritarian states’ tactics to deal with youth evolve not only as a response to collective action, as after 1989, but also due to changes in the perceived risk of student alienation from official politics among different leaders. In times of actual or perceived threat, the regime moves away from expecting passive compliance and conformity from students, and increasingly asks ‘voluntaristic’ loyalty from students (Walder Citation1985), echoing the ‘participation-oriented’ approach to student control of the Mao era (Yan Citation2014).

In building our argument, we highlight the sometimes subtle yet significant changes in the party-state’s strategies to manage students. In line with the political science literature on authoritarian regimes, we stress the importance of the penetration of society by party organisations for the maintenance of political stability (Magaloni Citation2006; Koss Citation2018). However, we find that the Chinese party-state’s Leninist penetration and control over society evolves, alternating between ‘corporatism’ and ‘partification’. Following the paralysis of the student control system in the 1980s, and the 1989 mobilisations, we have seen an evolution to a corporatist control framework in the 1990s under Jiang Zemin, giving a key role to party-led youth organisations in regimenting student activity. This framework was further institutionalised in the 2000s under Hu Jintao. We now witness a drastic turn towards more direct party control over student activities under Xi Jinping. Similar changes have been recorded in many socialist regimes during the Cold War as these regimes faced the dilemma of having to choose between close control over student activities, which resulted in apathetic attitudes among students, or sacrificing control to allow more bottom-up input and voluntary participation (McDougall Citation2004, pp. 185–201; Spaskovska Citation2017, p. 28). In the Chinese case, we stress that the tendency towards the partification of campuses may cause the long-term alienation of an entire generation of students from official channels of participation.

This essay starts with a discussion of ‘corporatism’ and ‘partification’ as distinctive CCP societal management strategies and a brief presentation of our methodology. We then analyse changes in the CCP’s strategy, looking first at the campus management system developed in the aftermath of 1989, and then at the changes introduced by the Xi Jinping administration after 2012. We conclude with an appraisal of the evolution of the party’s student management and its implication for our understanding of student politics in the People’s Republic of China.

Analytical framework and methodology

The comparative and communist politics literature stresses the institutional penetration and regimentation of society by communist party-controlled organisations (Jowitt Citation1993; Ware Citation1996), whose purpose is to act as a reliable channel for top-down propaganda, political control and mobilisation. In the Chinese context, in parallel to the state bureaucracy, lower-level control organisations are mainly grassroots party committees and branches, as well as party-led mass organisations, that is, specialised organisations for social or occupational groups, the most prominent being the Federation of Trade Unions (zonggonghui), the Women’s Federation (funü lianhehui) and the Communist Youth League (gongchan zhuyi qingnian tuan—CYL) (Hershatter Citation2004; Pringle Citation2011).

Within this apparently static framework, the party-state’s strategies to control and manipulate societal actors have changed over time. We look in particular at two competing tendencies in how the state deals with society: ‘corporatism’ and ‘partification’. Since the economic reforms of the 1980s, the institutional set-up regulating the registration and licensing of Chinese social organisations is corporatist in nature (Saich Citation2000; Ma Citation2002). Yet, going beyond classic conceptualisations of state corporatism (Schmitter Citation1974; Lu Citation2009), this framework of state–society relations has allowed the development of the associational sphere and the emergence of diverse grassroots organisations in post-Mao China (Saich Citation2000; Spires Citation2011). Notably, the rapid growth of this associational sphere was essentially an unintended consequence of Chinese corporatism and its lax implementation. The porous regulatory framework prompted social organisations to find ways to bypass it, often with the active assistance of local officials who preferred subverting the corporatist structure to gain the benefits of collaborating with non-state actors (Teets Citation2014, pp. 156–58). In practice, the corporatist framework allowed social organisations and local governments to negotiate their relationship and choose between formal or informal types of registration and cooperation (Hildebrandt Citation2011).

To remain relevant to their social constituencies, CCP-controlled mass organisations have developed significant autonomy in the post-Mao social context. In the 1980s, for instance, the burgeoning of study groups and associations focused on gender issues. It forced the All-China Women’s Federation to develop its own issue-oriented sub-organisations, creating, for example, the Women’s Studies Institute, and engage in pro-women advocacy and institution-building within the government. The Women’s Federation, therefore, found a subtle way to engage with the government on specific issues without challenging party-state domination (Judd Citation2002; Hershatter Citation2004; Angeloff & Liebe Citation2010). As the state’s role as social services provider decreased with market reforms, mass organisations, while maintaining their corporatist ties to the party, expanded their social reach and sources of funding through affiliated organisations over which they have varying degrees of control, a model that has been described as ‘low-cost corporatism’ (Doyon Citation2019). As a result, mass organisations became intermediaries between the party, social groups and organisations. Chinese corporatism is in part the product of expediency, that is, a pragmatic response to a rapidly changing economic and social environment that has challenged the CCP’s capacity to directly control and regiment society.

Despite this transition to a system with corporatist characteristics, direct party control has remained part of the CCP’s discourse and organisational toolkit, retaining its appeal to CCP leaders as an ‘ideal type’ of state–society relations. Under Xi Jinping, this appeal has been translated into an organisational remedy to the laxity of corporatism in controlling the development of China’s social environment, fuelling a move towards ‘partification’ characterised by party penetration of various social spheres, including universities, private companies and social organisations (Gore & Zheng Citation2019). Thus, whereas corporatism created a layered system of indirect control, with mass organisations as intermediate organisations, partification under Xi prescribes the strengthening of the party’s direct control over social actors. The alternation between corporatist tendencies and partification since the late 1970s recalls the description of the implementation of the 1980s–1990s market reforms as cyclical, moving between periods of ‘loosening’ (fang) and ‘tightening’ (shou) state control over the economy (Baum Citation1996). Yet, while the balancing effect of the competing fang/shou tendencies has arguably allowed for a gradual and relatively stable move from a planned to a market economy, we argue that similar changes in the realm of student management may cause alienation among students.

These different trends in state–society relations have not yet been studied systematically. This essay aims at partially filling this gap, exploring these changes through the microcosm of political control in university campuses, and control over student societies more specifically. Since the early twentieth century, student societies have been a cradle for the political evolution of China: from the mobilisations of 1919, which turned such associations into building blocks for political organisations, in particular communist ones (Graziani Citation2014), to the role they played in facilitating the 1989 demonstrations (Wasserstrom & Liu Citation1995; Zhao Citation2004). Yet, as Perry puts it, ‘ironically, the increased associational activity among Chinese students today is working to underpin, rather than to undermine, the authority of the Communist party-state’ (Perry Citation2014, p. 213). This essay focuses on this paradox to illuminate the methods and limits of the party-state’s control over society.

We record the CCP’s evolving strategy by comparing two transition periods centred around two key turning points: the student-led protests of 1989 and Xi’s rise to power in 2012. First, the Chinese party-state moved from a quite loose corporatist framework of control over student societies in the 1980s to increased party control after the 1989 democratic movement and the government’s brutal crackdown. In the following decades, corporatist control over student societies was normalised, leading to increased student apathy from the party’s perspective. This first transition has been well examined in both contemporary and retrospective accounts. We rely on that significant body of literature to flesh out the CCP’s short-term response based on increased direct party control and the longer-term corporatist strategy, comparing it with broader changes on and outside the campus. Second, fearing that rising apathy may lead to alienation, the Xi administration has partly remodelled the control apparatus on campus towards partification. Our analysis of this second period draws from fieldwork conducted during the years preceding and immediately following Xi’s rise to power (2009–2010 and 2012–2015), as well as from a close investigation of the CCP’s student policies ever since. During fieldwork, we covered five universities in three provinces (see ). We interviewed officials and students affiliated with political and non-political organisations and societies. To examine the rationale behind the partification strategy, we also rely on the findings of a survey conducted in Beijing in 2010 by one of the authors.Footnote2 The survey asked students to evaluate the work of campus-based organisations, notably the Communist Youth League and student societies (Tsimonis Citation2018). Our analysis is supplemented by organisational and policy documents, including party directives and guidelines, as well as speeches by CCP and CYL leaders. All locations and interviewees are presented in a coded form to ensure anonymity.Footnote3

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Universities Explored in this Study

Post-Tiananmen tightening: regimenting the campus

The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and the launch of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms accelerated the process of dissociating university students from official politics that had already started in the second phase of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). With the promise of an egalitarian society and perpetual revolution broken, Chinese students found themselves either in remote rural areas being ‘re-educated’ by peasants, as per Mao’s instructions, or back tied to the same party-led organisations on campus that they had attacked and dismantled only a few years before, in particular the Communist Youth League (Montaperto Citation1977; Healy Citation1982). Throughout the 1970s, the traumas of the Cultural Revolution fuelled societal disappointment, especially among the urban and educated classes and students (Heberer Citation2009). As the revolutionary idealism of the late 1960s faded away, the launch of economic reforms opened up a social space that was susceptible to foreign influences and accelerated students’ ideological and associational distancing from the regime.

In the first decade of the reform era, the loosening of social controls and the freer social environment that emerged contributed to what educators and officials in China have described as an ‘ideological crisis’ among youth (Kwong Citation1994, p. 247): essentially, the creation of a wide range of youth subcultures that defied party orthodoxy and discourse. In that regard, China resembled other industrialising societies that experienced waves of generational, political, ideological and cultural clashes with young people rejecting established norms (Jones Citation2009, pp. 15–8). In the Chinese context, the students’ iconoclasm of the 1980s mainly took three political forms: a profound distancing from official ideology; a widespread disassociation from the party’s organisational apparatus on campus; and an active search for alternative, bottom-up forms of organisation (Rosen Citation1992; Wasserstrom & Liu Citation1995).

In the early 1980s, CYL officials complained that their work was becoming harder due to the increasing influence of ‘Western concepts’ over young people (Chiang Citation1988). Different studies recorded students’ distancing from official ideology. For instance, inquiring about the low CCP membership admission rates among young intellectuals, a survey recorded that 70% had never read the essential works of China’s communist canon (Rosen Citation1987). A survey carried out in 29 universities in Jiangxi in 1988 recorded that only 2% of students considered Lei Feng, the CCP’s role model for youth, worthy of emulation (Rosen Citation1993, p. 321). Another 1988 survey carried out by the Beijing party committee showed that only 6.1% and 5% of university students chose ‘communism’ and ‘socialism’ respectively as ‘ideals that university students should establish’ (Rosen Citation1993, p. 324). The ideological decline of Chinese communism among students also affected attitudes to party membership. Reviewing the results of official party surveys conducted in the 1980s, Rosen (Citation1992, pp. 63–5) noted that only 14% of students believed that their peers joined the party out of altruistic or pure motives. Also, with the opening of new channels of social mobility, only 5.5% chose the ‘red’ career path of becoming CCP members and climbing in the party-state hierarchy.

The ideological distancing from the CCP was mirrored in students’ disassociation from party-led organisations on campus. A survey conducted at Wuhan University in 1987 revealed that 80% of students did not trust their student union, while 90% considered its work irrelevant to their interests and demands (Rosen Citation1990, p. 65). A 1988 report on CYL work noted that it was ‘unable to represent the specific interests of young people’ (Rosen Citation1990, p. 65). That same year, the CYL Secretary Song Defu claimed that the league had undergone a ‘divorce’ from Chinese youth (Chiang Citation1988, p. 36).

The yawning ideological and associational vacuum of the 1980s prompted students to create their own unofficial groups, serving not only academic, recreational and social purposes but also as nexus of political mobilisation (Wasserstrom & Liu Citation1995). The creation of independent student groups corresponded to the emergence of social organisations more broadly, as part of the rapid social development taking place in parallel to economic reform (Goldman Citation2006, p. 429). Defying prohibitions for unauthorised political organisation and taking advantage of widespread laxity in political control, students created ‘salons’ for political discussions and action committees, which served as the organisational basis for the 1986–1987 student protests, and then in 1989 (Schwarcz Citation1994; Guthrie Citation1995; Zhao Citation1997). Students involved with the student union and the CYL often spearheaded these developments. According to Zhao, they ‘not only resisted cooperation with the state, but also captured student control institutions to spread nonconformist ideologies’ (Zhao Citation2004, p. 114).

As a response to students’ alienation from official politics, reform-minded cadres saw the loosening of party control as essential for engaging youth (Ceng et al. Citation1980; Rosen Citation1985) and pushed, in 1988, to reform the CYL, giving it more autonomy from the CCP. However, this was a short-lived development, since the 1989 protests put students and the state on a collision course, prompting a change of strategy by the regime. In December 1989, the CCP called for a strengthening of party control over its three major mass organisations (Central Office of the Chinese Communist Party Citation1989), effectively cancelling the little autonomy student organisations had achieved in the 1980s.

Strengthening corporatism after 1989

Following the 1989 crackdown, Chinese campuses became the focus of the CCP’s efforts to regiment youth, since many party leaders viewed the relaxation of student control in the 1980s as one of the main contributing factors to the 1989 uprising (Zhao Citation2004; Yan Citation2014; Perry Citation2017). Measures aimed at strengthening direct political control over students were put forward in the following years. First, the political education curriculum was wholly rebuilt around the study of party theory (Hayhoe Citation1993). Since the 1990s, university students have been required to follow compulsory hours of political education according to the ‘two courses’ system: mandatory courses in Marxist ideology and morals, including regular classes on the current party line (Yan Citation2014, p. 501). Second, student salons and independent groups promoting Western political and social theory were forbidden (Hayhoe Citation1993). Moreover, all new students had to undertake military training, known as junxun, consisting of basic military drills as well as nationalist and pro-party propaganda (Rosen Citation1993). These drills have since been standardised, and short-term military training of a few weeks is now the norm in most universities across the country (Perry Citation2014).

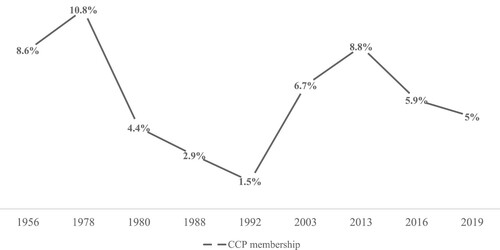

The 1989 events also triggered a long-term reflection on how to improve party control over university students and how better to co-opt them. Party membership was seen as a key means of ensuring that students had a stake in regime survival. CCP recruitment on campuses was particularly low in the 1980s and, after 1989, the party pushed for an increase in the recruitment of university students (Rosen Citation2004). As a result, recruitments on campuses quickly increased (see ). As we discuss later in the essay, the recent decrease in CCP membership among students reflects, by contrast, the party’s focus on members’ quality and activism.

FIGURE 1. Ratio of CCP Members Among Regular Higher Education Students

Sources: Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (Citation1993, Citation2003, Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2019).

Beyond the increase in ideological education and CCP recruitment, a significant change brought by the aftermath of the 1989 uprising has been the standardisation of a corporatist system of control over student societies led by the CCP with the support of its leading youth organisation, the Communist Youth League. From the 1990s onwards, the party-led control apparatus on campus was fully reinstated, and the overall structure remains the same today: student management is supervised at the top by the university’s CCP committee, which directly controls the university-level CYL committee as well as the faculty-level CCP committees. The CYL is, in turn, in charge of managing student organisations (Yan Citation2014). The most important of these organisations, the student union, is formally under the ‘leadership’ of the university’s party committee and the ‘supervision’ of the university CYL (Peking University Student Union Citation2010). The CYL has the key role in practice, since it controls its funds, most of its appointments, and must approve its activities.Footnote4 As a university CYL official put it in an interview:

The youth league’s function is to serve as a bridge between the CCP and young people. On campus, it plays the role of a ‘pre-party school’, teaching potential future party members about ideology as well as the history of the CCP. It prepares them to enter the CCP and helps with selection in order to unburden the party. Similarly, with the student union, the CYL is in charge of the daily management since the party does not have the resources to do this directly. In practice, it has an important role as an intermediary: it discusses the activities with the students, rejects those that are inappropriate and links with the university’s finances.Footnote5

The CYL’s central role in managing student activities results from a progressive standardisation of its functions on campus post-1989. As early as August 1989, the central CYL administration published ‘Opinions Regarding CYL Work in Universities in the Current Period’ (guanyu dangqian gaodeng xuexiao gongqingtuan gongzuo de ji dian yijian) (Communist Youth League Central Committee Citation1989). The various universities then translated into practice this document’s broad recommendations about increased political control. In the case of Peking University, direct elections for the chair of the student union—which had been the case in the 1980s and could lead to unwanted results from the party’s perspective—were replaced by indirect election by student representatives, with the CYL preselecting the candidates. Also, clearer rules and procedures were established in 1998 regarding the creation and funding of student societies under CYL management (Peking University Youth League Committee Citation2004). In 2005 the Ministry of Education and the Communist Youth League Central Committee issued two ‘Opinions’ on strengthening political control on campus and standardising the management of student societies. These documents further established the CYL’s function as the critical organisation for the day-to-day management of student societies, with a designated budget and staff (Ministry of Education Citation2005a, Citation2005b). The establishment and management of student societies were hence standardised: they had to be registered with the CYL and have an academic sponsor as well as a supervisory unit. This practice mirrors the countrywide regulations for the registration and management of social organisations (Ma Citation2002).

As long as they remained under the supervision of the CYL, student societies were allowed to multiply. To take Peking University as an example, there were 97 registered student societies in 1996 and over 300 in 2013 (Peking University Youth League Committee Citation2004, p. 153).Footnote6 Through its control over student societies, however, the CYL ensures that no independent organisation can develop and contest its hegemonic control over extracurricular student life.

Beyond its control over student societies, since the 1990s the CYL has also aimed to diversify its activities to attract students. In addition to its core ideological function, such as delivering party theory training for future CCP candidates, the CYL, together with the student union, has organised significant cultural events such as singing, sports and poetry competitions.Footnote7 For instance, since 1989 the CYL has organised a national competition of student scientific projects called the Challenge Cup, which became very popular and various universities later developed their own competition for their students (Peking University Youth League Committee Citation2004, p. 143). This trend intensified after 2003, when President Hu Jintao instructed the league to ‘keep youth satisfied’ by expanding service and recreational activities (Tsimonis Citation2021). The league became involved in graduate employment, for example, organising job fairs and seminars on CV writing and interview skills.

The prime embodiment of the CYL’s efforts to present itself in a more modern and attractive light for students is the Young Volunteers Operation launched in 1993.Footnote8 This operation aims to recruit young volunteers for a variety of projects on poverty alleviation, education assistance and environmental protection (Palmer & Ning Citation2020). Volunteers are also recruited for disaster relief operations and major international events. The Wenchuan earthquake of 2008 mobilised more than four million volunteers, and 1.7 million volunteers participated in the Olympic Games that same year (Chong Citation2011). Between 2001, when a formalised registration system for volunteers was established, and 2013, more than 40 million registered, including many university students.Footnote9 While these activities appear apolitical in content, they retain a clear political objective. The Young Volunteers Operation was launched to regain control over young people after the mobilisations of the 1980s and Tiananmen (Rosen Citation1992). More broadly, the diversification of their activities is a way for youth organisations to keep attracting students and maintain their monopoly over students’ extracurricular activities.

In sum, the framework for the post-1989 political control of the campus contains three elements: intensified indoctrination through military training, political education and party recruitment; a corporatist network of student organisations and societies; and a broad range of student-oriented and volunteer activities aimed at keeping students engaged with the CCP’s discourse and organisations. Although under the party’s leadership, the implementation and day-to-day management of this corporatist framework depended on its student organisations, mainly the CYL.

The end of corporatist laxity under Xi Jinping

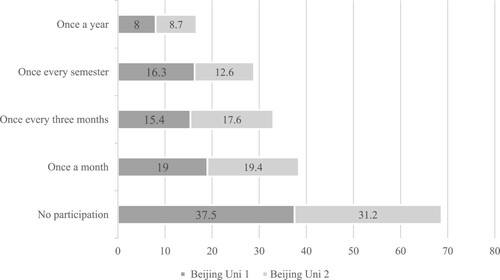

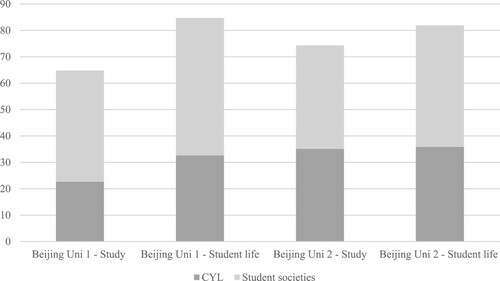

The combination of corporatist control and emphasis on student-oriented activities that characterised the post-1989 decades did not produce the intended results. Although there has been a noticeable expansion in the number of student societies and their activities, as well as of league and party membership, our research on student political attitudes and participation on campus reveals a picture of veiled distancing and token participation, especially in the case of the ‘reddest’ youth organisation on campus: the Communist Youth League. In the two Beijing-based elite universities surveyed during fieldwork in 2010, students either rejected the CYL outright or chose to participate as little as possible, with only two in ten students reporting participation in the CYL's monthly events (see ).

As part of the same survey, students were asked to compare the CYL with student societies in providing support for ‘study’ and ‘student life’, with respondents clearly favouring the latter (see ). This finding highlights how the CYL, despite being involved in the provision of student services as part of Hu Jintao’s call to ‘keep youth satisfied’ (Tsimonis Citation2021, p. 19), was viewed by students as a bureaucratic entity distant from their daily lives. In contrast, student societies, due to their bottom-up and voluntary nature, were perceived as more ‘useful’ for students.

FIGURE 3. 2010 Survey—Usefulness of Campus-based Organisations for Students: very/somewhat useful (%)

The corporatist framework described above led to a certain level of autonomy for student societies. While they had to conform to specific requirements and draft annual reports regarding their activities and membership, the CCP and CYL only scrutinised their daily activities from afar.Footnote10 Laxity in implementation was even more apparent in less prestigious schools. A technical university visited in Zhejiang province in 2010, for instance, allowed the establishment of student societies without the CYL’s involvement and supervision.Footnote11 Student societies also had quite a lot of leeway in seeking funds from organisations and companies outside the campus, under the supervision of the CYL.Footnote12 Some universities went further in experimenting with the autonomy of student organisations. In 2008, for example, Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou organised direct elections for the leadership of its student union, something that no other university had tried since 1989. Students conducted an active election campaign via the online and print student media outlets. Even though the CYL still preselected the candidates, the experience was judged as potentially disturbing to campus life and not pursued further. This example shows both the limits of student society autonomy and the students’ desire for political participation (He Citation2008).

These findings are in line with surveys on youth and student political participation carried out in the late Hu Jintao and early Xi Jinping periods, demonstrating a trend of youth distancing from official political processes and organisations. Investigating the frequency of participation in CYL activities, a survey organised by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the Beijing CYL Committee between 2013 and 2015 demonstrated that young people (defined as 16–35 years of age), university students among them, remained minimally engaged (17.4% ‘never participated’; 47.9% ‘occasionally participated’). Although university students were more likely to participate in CYL events than other respondents, the vast majority chose either to participate occasionally or not at all (Chang Citation2016, pp. 475–77). Moreover, another survey on political participation carried out by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2014 showed that adults between 18 and 45 years of age were the least likely to participate in elections for county- and township-level people’s congresses in comparison to other age groups. Participation rate in elections among this group only reached 22.25% and 24.5% at the county and township level respectively, compared to 27% and 30.75% for ages 46–60 and 33.75% and 30% for those over 60 (Fang et al. Citation2015, pp. 63, 273).

In the view of the party-state, this distancing from official channels of political participation was the result of lax control on campus and of student societies not paying sufficient attention to ‘ideological safety’, thus enabling an increase in individualism, materialism and Western cultural influences (Rosen Citation2010). This discourse echoes the one of party elites in the 1980s mentioned above and highlights the potential dangers of student apathy from the party-state’s viewpoint.

Bringing the party back in

During his first years in power, Xi Jinping repeatedly expressed his concern over the political socialisation of young people. In a series of speeches, he unveiled his vision for a holistic approach to political education, beginning at primary school, emphasising self-discipline and involving teachers, parents and school authorities. In particular, Xi noted, ‘it is the responsibility of the family, the school, the Young Pioneers [the CCP’s main children’s organisation], and the whole society to nurture the core values of socialism among children’. Schools had to strengthen political education in order to ‘let the seeds of socialist core values take root in the students’ hearts’.Footnote13

The current Chinese leadership is concerned with the level of student engagement with official politics and the ability of CCP-led organisations to foster loyalty. In December 2016, Xi Jinping chaired a National Meeting on Political Thought Work in Universities bringing together key officials in charge of political work in universities. During the meeting, Xi detailed his vision for the country’s higher education institutions, emphasising the training of ‘socialist successors’ as their core component.Footnote14 In particular, Xi called for the party to focus on specific groups that could become a ‘negative force’ if not appropriately managed, including actors of the new economy (such as the high-tech and communication sectors), young migrant workers, artists and unemployed university graduates (Xi Citation2017). From the party-state’s perspective, strengthening ideological education is seen as a way to canalise these groups—and youth more broadly—in a positive direction. Against this background, the government’s 2017 ‘Mid- to Long-Term Plan for the Development of Youth’, prioritised the ideological and moral training of young people over the improvement of their economic situation or health (State Council Citation2017b).

Xi’s renewed attention to young people’s loyalty to the party was translated into a new strategy regarding university students, concentrating on political thought work and changes in the curriculum, the role of mass organisations as a ‘second classroom’ for political education and the partification of student control through the enhanced role of party branches on campus.

Firstly, as part of this strategy, the curriculum of compulsory ideological education, which was standardised in the 1990s, was expanded. Student attendance in these courses is now monitored much more closely than in the past and students are also required to take online courses, such as ‘Young People Study Xi’, using official smartphone apps (Wang Citation2020). Beyond the expansion of political education itself, universities were required to revise their curricula in order to ensure the knowledge delivered was in line with the party-state’s ideological perspective and with a ‘Chinese approach to social sciences’ (State Council Citation2017a). This corresponds to the ‘Seven Don’t Speaks’ campaign launched in 2013 against the influence of Western values, which lists several topics not to be raised in public discussions, such as universal values and press freedom. In 2017 a State Textbook Committee was set up within the Ministry of Education to censor and supervise the curricula at all levels of education. This committee launched, in 2019, a countrywide inquiry into how the Chinese Constitution is taught in institutions of higher education, with the goal to erase from textbooks content that ‘promotes Western thought and advocates Western systems’ (Shen Citation2019).

Secondly, Xi’s strategy involved that student organisations and the CYL were tasked to refocus their efforts on ideological mobilisation (Ministry of Education Citation2016). The party accused the CYL of ‘becoming more and more bureaucratic, administrative, aristocratic and entertainment-oriented’, and therefore increasingly remote from the vanguard ideological organisation it is supposed to be (Central Commission for Discipline Inspection Citation2016). In a book compiling his comments on youth issues, Xi Jinping warned the CYL against ‘empty slogans’ and the risk of becoming an ‘empty shell’. He also called for a transformation of youth work and the strengthening of party control over the CYL (Xi Citation2017). In universities, the CYL is supposed to be more involved in academic matters, with its officials taking part in committees on the reform of the curriculum. It is supposed to fulfil the role as a ‘second classroom’, providing ideological education to students, as well as real-life experiences through volunteering. These activities can take the form of poverty alleviation efforts, environment protection campaigns, cultural events (sometimes abroad, in connection with the Belt and Road Initiative) and military training programmes. The goal is to ‘boost patriotism’ and ‘affirm [students’] ideological beliefs’ (Ministry of Education Citation2016). Such ‘social work’ activities make up an increasing part of students’ experience on campus: at least 15% of their study time for social sciences and humanities students, 25% for natural sciences students (Ministry of Education Citation2017b).

Thirdly, as part of the Xi administration’s partification drive, the party-state has been pushing to strengthen party organisations on campuses.Footnote15 After a months-long inquiry in 29 universities, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the party’s main disciplinary body, published ‘rectification reports’ criticising the underdevelopment of the party’s presence on campus. It described party branches as mostly idle and called for more supervision of the universities’ party leadership over lower-level party branches (Central Commission for Discipline Inspection Citation2017). To tackle these issues, all universities are tasked to further develop party grassroots organisations in departments and faculties. Criteria for recruiting students into the CCP has also refocused on political activism and the demonstration of ‘correct thinking’, reversing the tendency to select members based on their academic achievements. The goal is no longer to expand CCP membership among university students at all costs. The party now focuses on the quality and activism of members; it discourages token participation and attempts to ensure that student CCP members are active and form party branches to coordinate their activities. Coming back to , we can see that the ratio of CCP members among students has decreased in recent years, reaching a two-decade low in 2019.Footnote16

Against this background, the local party branch emerged as the focal point of student management. Party branches were required to provide improved party history and policy training for recruits, who were to be evaluated twice a year by their branch, and for senior party members, who had to complete at least 32 hours of training a year (Ministry of Education Citation2017c). CCP members interviewed before this policy change widely acknowledged that they had mostly stopped participating in political training once they had been admitted to the party.Footnote17 Party members were also to be monitored more closely and to take part in self-criticism sessions called Democratic Life Meetings. Information on CCP members studying abroad, in particular, was to be collected systematically. All these party-building efforts were to be regularly audited: at least once a year by the university party leadership, and once a term by the departments (Ministry of Education Citation2017c).

Party branches are becoming more active in academic matters, monitoring the behaviour of academics to ensure their ‘morality’ and ‘political correctness’. A ‘veto system’ has been introduced, and any infraction can directly affect an academic’s career (State Council Citation2017a). Scholars now report to the party branches in their departments, as since 2018 party branches’ heads have become ‘leaders on two fronts’, in charge of both political and academic matters (Ministry of Education Citation2018). As an interviewed academic put it: ‘We are now under a lot of pressure. Between the monitoring of the party organisation and the students who report on what we teach, we must be careful with what we say in the classroom.’Footnote18

The ‘partification’ of campus management was further codified in a set of party regulations issued in April 2021 (CCP Central Committee Citation2021). These regulations continue in the same direction as the aforementioned documents, expanding the powers (supervision over academics, students and all campus-based organisations) and responsibilities of party branches (setting up a discipline inspection commission and a party school), and providing more detailed instructions on operational matters (tenure of cadres, size of standing committee, ratio of students per full-time cadre). In effect, party organisations on campus are now expected to revamp their operation in the traditional fields of propaganda and political work while also micromanaging academic and student life on an unprecedented scale.

Accordingly, the party has also expanded its control over student societies. While the CYL is still in charge of supervising the registration and daily management of student groups, CCP control is now more direct (CCP Central Committee Citation2021). compares two versions of the regulations for student societies managements introduced at Peking University in 2006 and 2019 respectively, with a view to demonstrate that the management framework has become both more formalised and more party-led. While the party was never mentioned in the 2006 document, the 2019 version repeatedly stresses the leadership of the university’s party committee and states that every student society should now be headed by a student who is either a CYL or CCP member. This student is responsible for the group’s functioning in accordance with school rules and party-state policies (Peking University Citation2019). In some universities the rules go further towards partification and only CCP members can now create student societies.Footnote19 Peking University regulations also highlight the importance given to the management of student societies’ online activities, which have to be in accordance with existing laws on online activities and the party line (Peking University Citation2019). As Xi Jinping put it, the internet is a ‘battlefield’ that cannot be ignored (Xi Citation2017).

TABLE 2 Changes to the Management of Student Societies at Peking University (Citation2006, Citation2019)

This ‘partification’ of Chinese universities goes against the loose corporatist structure implemented in the 1990s. Direct party control is strengthened and, while it still plays a key role on campus, the CYL’s monopolistic position as a broker between the party and student societies has been challenged. The emphasis is now on the development of party branches and activities, and the CYL is barely mentioned in recent policy documents about political work on campus (State Council Citation2017a; CCP Central Committee Citation2021). At the same time, CYL-specific documents stress increased party control over the organisation, requiring that university-level party committees review the work of CYL branches’ activities at least once a year (Central Communist Youth League Citation2017). The 2021 Regulations further reassign the league’s responsibility to supervise student activities and societies to party branches (CCP Central Committee Citation2021).

These changes are part of a broader tendency to decrease the CYL’s autonomy. A reform of the organisation adopted in 2016 reduced its central leadership and increased party control over it (Central Communist Youth League Citation2016a). The central CYL’s budget was also cut by half (a reduction of 50.93% or approximately RMB318 million) between 2015 and 2016 when the league lost part of its control over major volunteer projects and the associated funding (Central Communist Youth League Citation2016b). Hence, the Youth League has been progressively losing its monopolistic grip over volunteering and student-oriented activities, which in the past two decades has been a central part of its function on campus.Footnote20 In addition, the China Youth University of Political Studies, a higher education institution directly managed by the CYL, has been stripped of most of its programmes, which have been absorbed into the newly founded University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.Footnote21

While analysts have described this weakening of the Communist Youth League as an attack on the former president, Hu Jintao, and current premier, Li Keqiang, viewed as heads of a faction made up of former youth league leaders (Li Citation2016), we stress that these changes have taken place in the context of a broader move towards partification. This move is the result of the Xi Jinping administration blaming student alienation from official political channels on the laxity of the corporatist arrangement in place since the 1990s. Apart from the renewed emphasis on a regimented and ideologically exclusive curriculum, a new range of guidelines and regulations issued post-2013 envision a partified system of control with intensified ideological indoctrination in and outside the classroom. The move from indirect to direct control of the campus is well captured by changes in the management of student societies. New and more rigid controls have been imposed to regulate the establishment and operation of student societies and to bring them in line with the party organisationally and politically. Yet, this move towards partification is not limited to universities. Party penetration of society is intensifying both quantitatively, as the number of grassroots party cells increases, and qualitatively, as the power of party units within privately owned companies, public firms and administrations is strengthened (Grünberg & Drinhausen Citation2019; Doyon Citation2021).

Conclusion

Analysing the evolution of student policies around two turning points, the student-led protests of 1989 and Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012, this essay stresses the CCP’s ongoing effort to find a balance between encouraging political engagement by students but retaining control over the nature and consequences of this engagement, a common issue for authoritarian regimes (Tsimonis Citation2021). While the existing literature treats the depoliticisation of campuses and student apathy as the main goals of post-1989 student management efforts (Rosen Citation2010; Yan Citation2014), we highlight that the goal of the Xi Jinping administration is active student engagement with the party’s political activities. After all, student disengagement from official organisations in the 1980s was one of the few signs of the impending rapid shift from passivity to anti-government mobilisation. More recently, university students have challenged, albeit subtly, the party-state’s post-1989 regimentation of universities, as illustrated in the young Marxists support for labour movements mentioned in the introduction as well as #MeToo online campaigns (Lin & Yang Citation2019).

Moving away from the corporatist framework of the 1990s and 2000s, the Xi Jinping administration developed, from 2012 onwards, a new strategy that relied on the partification of student management. Party committees and branches become the primary control tool while mass organisations lost their autonomy in dealing with student activities. This change has gone together with an emphasis on the quality and intensity of participation over quantity, as evidenced by a drop in party membership among students over the last decade. The previous logic of equating passive membership with political participation has been abandoned for now. Still, it is not clear if the new approach will motivate students to engage with official politics.

The party-state’s efforts to control the associational sphere in the microcosm of Chinese campuses reflect evolving dynamics in China’s state–society relations. New regulations and policies facilitate the organisational penetration of civil society, including the requirement to establish party groups within private companies, NGOs, charities and other organisations. This move, from the party as a regulator under corporatism, to direct controller under partification, fuels the image of the CCP as an aspiring omnipresent authoritarian entity. These evolutions highlight the diversity of the means of control authoritarian states have at their disposal in controlling social forces, and that they may alternate between strategies, depending on how concerned they are about potential mobilisations (Bueno de Mesquita & Downs Citation2005), and hence the form of loyalty they expect from their citizenry: encouraging depoliticisation and passive compliance or voluntaristic commitment (Walder, Citation1985; Wedeen Citation1999; LaPorte Citation2015).

Enriching the literature on state-mobilised movements (Silvan Citation2019; Ekiert et al. Citation2020; Nizhnikau & Silvan, this issue), we stress that in times of crisis, actual or perceived, authoritarian states may hence move away from a depoliticising strategy and take risks to limit apathy through the party’s direct involvement in student affairs. However, these efforts may alienate individuals and groups. Whereas the lax corporatist model under Jiang and Hu offered the space necessary for social organisations to negotiate their proximity to the party-state, the partified model limits this space. By further restricting the autonomy of social organisations in general, and student societies in particular, the regime may well push young people towards other channels of political participation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jérôme Doyon

Jérôme Doyon, Harvard Kennedy School, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 79 John F. Kennedy Street, Mailbox 74, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. Email: [email protected]

Konstantinos Tsimonis

Konstantinos Tsimonis, Lau China Institute. King’s College London, Room 5.03 Bush House North East Wing, 40 Aldwych, London, WC2B 4PX, UK. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 ‘Xi Jinping’s Speech for Students and Academics at Peking University’, Xinhua, 4 May 2014, available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2014-05/05/content_2671258.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

2 This was the Beijing leg of a survey conducted in three universities in the Chinese capital and in a city in Zhejiang province. In total, the authors collected 1,705 self-administered questionnaires (Beijing University 1: 662; Beijing University 2: 495).

3 See the Appendix for a full list of interviews.

4 Interview 1, university CYL official, Jiangsu Province, 26 June 2012; Interview 2, university CYL official, Beijing, 3 July 2012.

5 Interview 3, university CYL official, Jiangsu Province, 2 February 2015.

6 Interview 4, university CYL official, Beijing, 10 July 2013.

7 Interview 5, university CYL official, Jiangsu Province, 9 June 2013; Interview 6, university CYL official, Beijing, 10 July 2013; Interview 7, university CYL official, Jiangsu Province, 8 February 2015.

8 Interview 8, Beijing Volunteers Federation official, Beijing, January 2010; Interview 9, central CYL official, Beijing, 18 March 2015.

9 ‘Report on the 20 Years of the China Young Volunteers Operation’, China Youth Daily, 5 December 2013.

10 Interview 10, student society volunteer, Jiangsu Province, 10 June 2013; Interview 11, student society volunteer, Jiangsu Province, 12 November 2014; Interview 12, student society volunteer, Beijing, 29 October 2009.

11 Interview 13, university CYL Secretary, Zhejiang Province, 19 May 2010.

12 Interview 10, student society volunteer, Jiangsu Province, 10 June 2013; Interview 14, student society volunteer, Jiangsu Province, 15 June 2013.

13 ‘Xi Jinping’s Speech at a Symposium in the Ethnic Primary School in Haidian District, Beijing’, People’s Daily, 30 May 2014, available at: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/0531/c64094-25088947.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

14 ‘Xi Jinping, Political Thought Work Should Run Through the Entire Education Process’, Xinhua, 8 December 2016, available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-12/08/c_1120082577.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

15 ‘Xi Jinping, Political Thought Work Should Run Through the Entire Education Process’, Xinhua, 8 December 2016, available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-12/08/c_1120082577.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

16 See also, ‘Party Rules: China’s Communist Party Goes for Quality Over Quantity: Annual Tally of Shortlisted Party Applicants Declined by 5% from 2013 to 2015’, Wall Street Journal, 5 January 2017, available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-CJB-29703, accessed 3 September 2020.

17 Interview 1, university CYL official, Jiangsu Province, 26 June 2012; Interview 2, university CYL official, Beijing, 3 July 2012.

18 Interview 15, university professor, Jiangsu Province, 15 July 2018.

19 ‘Provisional Solution for the Management of Student Societies’, North China Institute of Science and Technology, 30 October 2019, available at: http://dw.ncist.edu.cn/article/2019-12-23/art33055.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

20 Interview 15, local CYL official, Beijing, 28 July 2017.

21 ‘The Bachelor Degrees of the China Youth University of Political Science to be Transferred to the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’, Xinhua, 19 May 2017, available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/2017-05/19/c_1121003341.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

References

- Angeloff, T. & Lieber, M. (2010) ‘Equality, Did You Say? Chinese Feminism After 30 Years of Reforms’, China Perspectives, 4.

- Baum, R. (1996) Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping (Princeton, NJ & Chichester, Princeton University Press).

- Bueno de Mesquita, B. & Downs, G. W. (2005) ‘Development and Democracy’, Foreign Affairs, 84, 5.

- Bunce, V. & Wolchik, S. (2011) Defeating Authoritarian Leaders in Postcommunist Countries (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Cammaerts, B., Bruter, M., Banaji, S., Harrison, S. & Anstead, N. (2014) ‘The Myth of Youth Apathy: Young Europeans’ Critical Attitudes Toward Democratic Life’, American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 5.

- CCP Central Committee (2021) ‘Zhongguo gongchandang putong gaodeng xuexiao jiceng zuzhi gongzuo tiaoli’, Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, 23 April 2021, available at: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2021-04/23/nw.D110000renmrb_20210423_1-03.htm# accessed 24 April 2021.

- Ceng, T., Zhu, H. & Zhang, B. (1980) ‘Do You Know the Characteristics of the 1980s Youth?’, China Youth, 24 July.

- Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (2016) ‘Zhongyang di er xunshi zu xiang gongqingtuan zhongyang fankui shi teding xunshi qingkuang’, 4 February, available at: https://www.ccdi.gov.cn/special/zyxszt/2015dsl_zyxs/fgqg_2015dsl_zyxs/201602/t20160219_74595.html, accessed 12 May 2022.

- Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (2017) ‘Shiba jie zhongyang di shi’er lun xunshi gongbu shisi suo zhong guan gaoxiao xunshi fankui qingkuang’, 16 June, available at: http://www.ccdi.gov.cn/toutiao/201706/t20170615_125706.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Central Communist Youth League (2016a) ‘Gongqingtuan zhongyang gaige fang’an’, 2 August, available at: http://www.ccyl.org.cn/notice/201608/P020160809382774540571.pdf, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Central Communist Youth League (2016b) ‘Gongqingtuan zhongyang 2016 nian bumen yusuan’, 15 April, available at: http://www.ccyl.org.cn/notice/201604/t20160415_757233.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Central Communist Youth League (2017) ‘Gongqingtuan zhongyang jiaoyu bu guanyu yinfa “guanyu jiaqiang he gaijin xin xingshi xia gaoxiao gongqingtuan sixiang zhengzhi gongzuo de yijian” de tongzhi’, 27 February, available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/moe_1777/moe_1779/201709/t20170914_314466.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Central Office of the Chinese Communist Party (1989) ‘Zhonggong zhongyang guanyu jiaqiang he gaishan dang dui gonghui, gongqingtuan, fulian gongzuo lingdao de tongzhi’, 12 December, available at: http://www.reformdata.org/1989/1221/4083.shtml, accessed 15 May 2022.

- Communist Youth League Central Committee (1989) ‘Guanyu dangqian gaodeng xuexiao gongqingtuan gongzuo de ji dian yijian’, 13 August, available at: http://law767.infoeach.com/view-NzY3fDgxNDg4.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Chan, J. (2020) ‘A Precarious Worker–Student Alliance in Xi’s China’, China Review, 20, 1.

- Chang, Y. (2016) The Changes in the Social Structure of the Youth and Reform of the Communist Youth League in Beijing (Beijing, Social Sciences Academic Press).

- Chiang, C. (1988) ‘The CYL’s 12th National Congress: An Analysis’, Issues and Studies, 24, 7.

- Chong, G. (2011) ‘Volunteers as the “New” Model Citizens: Governing Citizens Through Soft Power’, China Information, 25, 1.

- Dahl, V., Amnå, E., Banaji, S., Landberg, M., Šerek, J., Ribeiro, N., Beilmann, M., Pavlopoulos, V. & Zani, B. (2018) ‘Apathy or Alienation? Political Passivity among Youths Across Eight European Union Countries’, European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15, 3.

- Doyon, J. (2019) ‘Low-Cost Corporatism? The Chinese Communist Youth League and its Sub-Organisations in Post-Mao China’, China Perspectives, 2019.

- Doyon, J. (2021) ‘Influence without Ownership: The Chinese Communist Party Targets the Private Sector’, Institute Montaigne, available at: https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/influence-without-ownership-chinese-communist-party-targets-private-sector?_wrapper_format=html, accessed 20 March 2021.

- Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (1993) (Beijing, People’s Education Press).

- Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (2003) (Beijing, People’s Education Press).

- Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (2013) (Beijing, People’s Education Press).

- Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (2016) (Beijing, People’s Education Press).

- Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (2017) (Beijing, People’s Education Press).

- Educational Statistics Yearbook of China (2019) (Beijing, People’s Education Press).

- Ekiert, G., Perry, E. J. & Yan, X. (2020) Ruling by Other Means State-Mobilized Movements (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Fang, N., Yang, H., Shi, W. & Zhou, Q. (2015) Zhongguo zhengzhi canyu lanpishu (Beijing, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences).

- Forrat, N. (2015) ‘The Political Economy of Russian Higher Education: Why Does Putin Support Research Universities?’, Post-Soviet Affairs, 32, 4.

- Goldman, M. (2006) ‘The Post-Mao Reform Era’, in Goldman, M. & Fairbank, J. K. (eds) China: A New History (2nd enlarged edn) (Cambridge, MA, & London, Harvard University Press).

- Gore, L. & Zheng, Y. (eds) (2019) The Chinese Communist Party in Action (London, Routledge).

- Graziani, S. (2014) ‘Youth and the Making of Modern China: A Study of the Communist Youth League’s Organisation and Strategies in Times of Revolution (1920–1937)’, European Journal of East Asian Studies, 13, 1.

- Grünberg, N. & Drinhausen, K. (2019) ‘The Party Leads on Everything: China’s Changing Governance in Xi Jinping’s New Era’, MERICS, 24 September, available at: https://merics.org/en/report/party-leads-everything accessed 20 March 2021.

- Guthrie, D. J. (1995) ‘Political Theater and Student Organisations in the 1989 Chinese Movement: A Multivariate Analysis of Tiananmen’, Sociological Forum, 10, 3.

- Hayhoe, R. (1993) ‘China’s Universities Since Tiananmen: A Critical Assessment’, China Quarterly, 134.

- He, H. (2008) ‘Full Record of the Student Union Chairman Direct Election’, Southern Weekend, 13 November.

- Healy, P. M. (1982) The Chinese Communist Youth League, 1949–1979 (Nathan, QLD, Griffith University).

- Heberer, T. (2009) ‘The “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”: China’s Modern Trauma’, Journal of Modern Chinese History, 3, 2.

- Hershatter, G. (2004) ‘State of the Field: Women in China’s Long Twentieth Century’, Journal of Asian Studies, 63, 4.

- Hildebrandt, T. (2011) ‘The Political Economy of Social Organization Registration in China’, China Quarterly, 208.

- Jain, R. (2019) ‘The Tightening Ideational Regimentation of China’s Higher Education System’, Economic & Political Weekly, 54, 30.

- Jones, G. (2009) Youth (Cambridge, Polity).

- Jowitt, K. (1993) New World Disorder: The Leninist Extinction (Berkeley, CA, University of California Press).

- Judd, E. R. (2002) The Chinese Women’s Movement Between State and Market (Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press).

- Koss, D. (2018) Where the Party Rules: The Rank and File of China’s Communist State (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Kwong, J. (1994) ‘Ideological Crisis among China’s Youths: Values and Official Ideology’, British Journal of Sociology, 45, 2.

- Lanza, F. (2010) Behind the Gate: Inventing Students in Beijing (New York, NY, Columbia University Press).

- LaPorte, J. (2015) ‘Hidden in Plain Sight: Political Opposition and Hegemonic Authoritarianism in Azerbaijan’, Post-Soviet Affairs, 31, 4.

- Li, C. (2016) Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press).

- Lin, Z. & Yang, L. (2019) ‘Individual and Collective Empowerment: Women’s Voices in the #MeToo Movement in China’, Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 25, 1.

- Lu, Y. (2009) Non-Governmental Organisations in China: The Rise of Dependent Autonomy (London & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Ma, Q. (2002) ‘The Governance of NGOs in China Since 1978: How Much Autonomy?’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31, 3.

- Magaloni, B. (2006) Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and Its Demise in Mexico (Cambridge & New York, NY, Cambridge University Press).

- McDougall, A. (2004) Youth Politics in East Germany: The Free German Youth Movement, 1946–1968 (Oxford, Clarendon).

- Ministry of Education (2005a) ‘Gongqingtuan zhongyang jiaoyu bu guanyu jinyibu jiaqiang he gaijin gaodeng xuexiao gongqingtuan jiansha de yijian’, Document 15, 8 April, available at: http://xgc.hbzyy.org/News_View.asp?NewsID = 11906, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Ministry of Education (2005b) ‘Guanyu jiaqiang he gaijin daxuesheng shetuan gongzuo de yijian’, Document 5, 13 January, available at: https://baike.baidu.com/item/关于加强和改进大学生社团工作的意见/6390717, accessed 12 May 2022.

- Ministry of Education (2016) ‘Gaoxiao xuesheng shetuan guanli zhanxing banfa chutai’, 13 January, available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/201601/t20160113_227746.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Ministry of Education (2017a) ‘Quanguo gaodeng xuexiao mingdan’, 31 May, available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A03/moe_634/201706/t20170614_306900.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Ministry of Education (2017b) ‘Zhonggong jiaoyu bu dangzu guanyu yinfa “gaoxiao sixiang zhengzhi gongzuo zhiliang tisheng gongcheng shishi gangyao” de tongzhi’, 5 December, available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A12/s7060/201712/t20171206_320698.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Ministry of Education (2017c) ‘Zhonggong jiaoyu bu dangzu guanyu yinfa “putong gaodeng xuexiao xuesheng dangjian gongzuo biaozhun” de tongzhi’, 1 March, available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A12/moe_1416/moe_1417/201703/t20170310_298978.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Ministry of Education (2018) ‘Zhonggong jiaoyu bu dangzu guanyu gaoxiao jiaoshi dang zhibu shuji “shuang daitou ren” peiyu gongcheng de shishi yijian’, 23 May, available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A12/moe_1416/s255/201805/t20180524_337021.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Montaperto, R. N. (1977) The Chinese Communist Youth League and the Political Socialization of Chinese Youth, PhD thesis (Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan).

- Palmer, D. & Ning, R. (2020) ‘The Resurrection of Lei Feng: Rebuilding the Chinese Party-State’s Infrastructure of Volunteer Mobilization’, in Perry, E., Yan, X. & Ekiert, G. (eds) Ruling by Other Means: State-Mobilized Social Movements (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Peking University (2006) ‘Beijing daxue xuesheng shetuan guanli tiaoli’, 4 April, available at: https://baike.baidu.com/item/北京大学学生社团管理条例/9344827, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Peking University (2019) ‘Beijing daxue xuesheng shetuan guanli banfa’, 8 May, available at: https://tfzx.pku.edu.cn/rules/98231.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Peking University Student Union (2010) ‘Beijing daxue xueshenghui zhangcheng’, May, available at: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/41c7e77d27284b73f24250eb.html, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Peking University Youth League Committee (2004) The Communist Youth League in Peking University (Beijing, People’s Press).

- Perry, E. (2014) ‘Citizen Contention and Campus Calm: The Paradox of Chinese Civil Society’, Current History, 113, 764.

- Perry, E. (2017) ‘Cultural Governance in Contemporary China: “Re-Orienting” Party Propaganda’, in Shue, V. & Thornton, P. M. (eds) To Govern China: Evolving Practices of Power (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Perry, E. (2019) ‘Educated Acquiescence: How Academia Sustains Authoritarianism in China’, Theory & Society, 49, 1.

- Pringle, T. (2011) Trade Unions in China: The Challenge of Labour Unrest (Abingdon & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Rosen, S. (1985) ‘Prosperity, Privatisation, and China’s Youth’, Problems of Communism, 34.

- Rosen, S. (1987) ‘Youth Socialization and Political Recruitment in Post-Mao China’, Chinese Law & Government, 20, 2.

- Rosen, S. (1990) ‘The Chinese Communist Party and Chinese Society: Popular Attitudes Toward Party Membership and the Party’s Image’, Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, 24.

- Rosen, S. (1992) ‘Students and the State in China: The Crisis in Ideology and Organization’, in Rosenbaum, A. L. & Lee, C. (eds) State and Society in China: The Consequences of Reform (Oxford, Westview).

- Rosen, S. (1993) ‘The Effect of Post-4 June Re-Education Campaigns on Chinese Students’, China Quarterly, 134.

- Rosen, S. (2004) ‘The Victory of Materialism: Aspirations to Join China's Urban Moneyed Classes and the Commercialization of Education’, The China Journal, 51.

- Rosen, S. (2010) ‘Chinese Youth and State–Society Relations’, in Gries, P. & Rosen, S. (eds) Chinese Politics: State, Society and the Market (Abingdon & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Saich, T. (2000) ‘Negotiating the State: The Development of Social Organizations in China’, China Quarterly, 161.

- Schmitter, P. (1974) ‘Still the Century of Corporatism?’, Review of Politics, 36, 1.

- Schwarcz, V. (1994) ‘Memory and Commemoration: The Chinese Search for a Livable Past’, in Wasserstrom, J. & Perry, E. J. (eds) Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China (New York, NY, Routledge).

- Shen, X. (2019) ‘China Continues to Spread Communism across College Campuses’, Bitter Winter, 25 March, available at: https://bitterwinter.org/china-continues-to-spread-communism-across-college-campuses/, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Silvan, K. (2019) ‘(Dis)Engaging Youth in Contemporary Belarus Through a Pro-Presidential Youth League’, Demokratizatsiya, 27, 3.

- Spaskovska, L. (2017) The Last Yugoslav Generation: The Rethinking of Youth Politics and Cultures in Late Socialism (Manchester, Manchester University Press).

- Spires, A. (2011) ‘Contingent Symbiosis and Civil Society in an Authoritarian State: Understanding the Survival of China’s Grassroots NGOs’, American Journal of Sociology, 117, 1.

- State Council (2017a) ‘Zhonggong zhongyang guowuyuan yinfa “guanyu jiaqiang he gaijin xin xingshi xia gaoxiao sixiang zhengzhe gongzuo de yijian”’, 27 February, available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2017-02/27/c_1120538762.htm, accessed 3 September 2020.

- State Council (2017b) ‘Zhongchangqi qingnian fazhan guihua 2016–2015 nian’, 13 April, available at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2017-04/13/content_5185555.htm#1, accessed 30 June 2021.

- Steger, I. (2014) ‘Political Generation Rises in Hong Kong: Legacy of Protests Lies not in Legislation but in Students’ Political Awakening’, Wall Street Journal, 11 December, available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/political-generation-rises-in-hong-kong-1418234231, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Teets, J. (2014) Civil Society Under Authoritarianism: The China Model (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Tsimonis, K. (2018) ‘Keep the Party Assured and the Youth [Not] Satisfied: The Communist Youth League and Chinese University Students’, Modern China, 44, 2.

- Tsimonis, K. (2021) The Chinese Communist Youth League: Juniority and Responsiveness in a Party Youth Organization (Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press).

- Walder, A. (1985) ‘The Political Dimension of Social Mobility in Communist States: China and the Soviet Union’, Research in Political Sociology, 1.

- Wang, Y. (2020) ‘Ideological Education Pushes Out Other University Courses’, Bitter Winter, 1 May, available at: https://bitterwinter.org/ideological-education-pushes-out-other-university-courses/, accessed 3 September 2020.

- Ware, A. (1996) Political Parties and Party Systems (Oxford & New York, NY, Oxford University Press).

- Wasserstrom, J. (2015) ‘The Kids are Alright’, The Wall Street Journal, 18 August.

- Wasserstrom, J. & Liu, X. (1995) ‘Student Associations and Mass Movements’, in Davis, D., Perry, E., Kraus, R. & Naughton, B. (eds) Urban Spaces in Contemporary China: The Potential for Autonomy and Community in Post-Mao China (Cambridge & New York, NY, Woodrow Wilson Center Press & Cambridge University Press).

- Wedeen, L. (1999) Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria (Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press).

- Weiss, J. C. (2014) Powerful Patriots: Nationalist Protest in China’s Foreign Relations (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Xi, J. (2017) Compilation of Xi Jinping’s Remarks on Youth and the Work of the Communist Youth League (Beijing, Central Party Literature Press).

- Yan, X. (2014) ‘Engineering Stability: Authoritarian Political Control Over University Students in Post-Deng China’, The China Quarterly, 218.

- Zhao, D. (2004) The Power of Tiananmen: State–Society Relations and the 1989 Beijing Student Movement (Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press).

- Zhao, D. (1997) ‘Decline of Political Control in Chinese Universities and the Rise of the 1989 Chinese Student Movement’, Sociological Perspectives, 40, 2.