Abstract

Political attitudes are generally analysed within the context of a given nation-state, even if they reflect responses to regional or global developments. Little attention has been paid to the potentially moderating role of personal transnational experiences (travel, migration, remittances) on individual attitudes. Based on two cross-sectional online surveys conducted in 15 cities across Russia in 2018 and 2019, this essay assesses the extent to which personal transnational experiences play a role in the domestic and foreign policy preferences of young Russians. Our analysis finds a consistent relationship between transnational experiences and the attitudes of young Russians.

Migration reshapes the political and social realities of those who leave a country, but also of those who stay. Since the Soviet Union’s breakup, the Russian Federation has seen significant emigration, contributing to concerns in the country about a brain drain of young talent. Russia is the third largest country of origin of migrants globallyFootnote1 and an increasing number of young and educated Russians have leftFootnote2 or express a desire to leave the country.Footnote3 Young people consider migrating more frequently than adults and have the capacity to realise this ambition through access to internationalised educational programmes and increased labour mobility that is less feasible for older generations. The share of young people in today’s migration flows is considerably larger than that of adultsFootnote4 and young people are consequently more likely to be connected to cross-border networks.

In this essay, we focus on young people in Russia and their transnational exposure through contacts to friends and family members who have left the country and personal travel experience. We aim to understand how people with a range of personal connections beyond Russia differ from those who do not have these links. We extend the research on migrant political attitudes and transnational engagement by focusing on the receiving end of such influences in the country of origin. We hypothesise that those with access to transnational contexts and networks differ from other citizens with regard to their political attitudes and behaviour, their social values and their trust in key state institutions in their home country.

In addition to the disruptive impact that emigration may have on the demographic and social structure of the locality that people leave, migrants may also continue to influence friends and family members in these places through the financial, social and political transfers they make from abroad. The ways in which mobility impacts on migrants’ countries of origin have recently received more academic attention, thereby extending the traditional focus on the migrants’ impact on their destination localities (Délano & Gamlen Citation2014; Meseguer & Burgess Citation2014; Zahra Citation2016; Koinova & Tsourapas Citation2018). It is particularly the mobility of young people that reshapes societies in their countries of departure and arrival. It has the potential to result in brain drain in the home country and reduce pressure for social and political change (Castles Citation2000). As this essay investigates, young people who have left their country remain relevant to the social and political orientation of those they leave behind.

Over the past decade, such transnational circulation of norms and ideas has become the focus of academic study (Burgess Citation2014; Kapur Citation2014). Research on international economic remittances has begun to address the socio-economic and political consequences of migrants supporting their families and friends financially in their countries of origin (Adida & Girod Citation2011; Ahmed Citation2012; Gallo Citation2013; Mata-Codesal Citation2013; Doyle Citation2015). However, research on the political effects of these transfers remains inconclusive: on the one hand, such remittances may provide the resources required for electoral and non-electoral political action in the country of origin, including protests (Barry et al. Citation2014; Miller & Ritter Citation2014; Regan & Frank Citation2014). On the other, greater independence from the state due to these remittances may foster political acquiescence and regime stability (Doyle Citation2015).

The analysis of the impact that remittances may have has been broadened in response to a new line of enquiry into the ideas, know-how, norms, values and behaviours that migrants ‘send home’ alongside or instead of financial contributions. These are defined as a distinctive phenomenon under the broad umbrella category of ‘social remittances’ (Glick Schiller et al. Citation1992; Levitt Citation1998; Goldring Citation2004; Levitt & Lamba-Nieves Citation2011). Research from across various disciplines has demonstrated that multidirectional flows of political principles, vocabulary and practices have the potential to influence political behaviour, mobilisation, organisation and narratives of belonging in the countries of departure and arrival (Krawatzek & Müller-Funk Citation2020).

In this essay, we will first locate our research on transnational influences on young people in Russia within the existing scholarship on transnational networks and remittances before presenting our data, our methodology and the findings of our analyses. We show that the transnational links of young Russians correlate with their domestic and foreign policy preferences, trust in political institutions and perceptions of the legitimacy of protest. We elucidate how these trends vary across issues and institutions, and how the regions these young people are connected to correlate with their political attitudes. While our data do not allow us to substantiate a direct causal effect for transnational links, we expand the research agenda on transnational linkages by highlighting consistent patterns in the attitudes and practices of Russian youth who maintain active links to their families and friends abroad or travel beyond Russia.

The political relevance of transnational contacts

Transnational social networks

Social networks function as trusted channels of information, particularly in transnational contexts as they provide seemingly authentic information (Farré & Fasani Citation2013; Bakewell et al. Citation2016). The ties anchored in these social networks have been found to significantly influence an individual’s decision to mobilise, protest or migrate (McKenzie & Rapoport Citation2007; Diani Citation2013). Academics researching migration distinguish between migration networks that facilitate migration through information exchange as well as financial and social support (Massey & Espana Citation1987; Bade Citation2003; Haug Citation2008), and migrant networks that sustain the social interactions between migrants in the destination country as well as the links between migrants and their families and friends ‘at home’ (Bommes Citation2011; Krawatzek & Sasse Citation2018). The relevance of everyday migrant networks through which different types of remittances flow has primarily been studied in terms of how they affect migrant attitudes and their engagement with their places of destination and origin.

Granovetter’s (Citation1973) premise of the strength of weak ties, arguably more important for communication and social mobility than strong transitive ties to family members and friends, is generally borne out by academics in the field of migration studies. However, the varying definitions of ‘weak ties’—ranging from people helping to find jobs for newly arrived migrants (Elrick & Lewandowska Citation2008) to distant family relations and acquaintances (Liu Citation2005)—make it hard to generalise about the type and depth of migrants’ social ties. In our analysis, we explicitly probe the relevance of ‘strong ties’ to family members and friends from the perspective of those residing in the place of origin.

Rooted in the international relations literature on norm diffusion, Keck and Sikkink (Citation1998), for instance, highlighted the need to understand these types of flows as grassroots phenomena. Others have used the terms ‘transnational social spaces’ and ‘transnational social fields’ to describe sets of social relations that shape identities and behaviours (Glick Schiller et al. Citation1992; Basch et al. Citation1994; Risse-Kappen Citation1995; Faist Citation2000; Pries Citation2001; Wimmer & Glick Schiller Citation2002; Vertovec Citation2009). The concept of ‘social remittances’ (Levitt Citation2001) broadened discussions around financial transfers made by migrants in order to capture norms, practices, identities and social capital transmitted through migration. Migrants are thus conceptualised as ‘norm entrepreneurs’ and transnational agents of social change (Glick Schiller et al. Citation1992; Levitt Citation1998, Citation2001; Itzigsohn et al. Citation1999). Over time, the original conceptualisation of social remittances has been extended beyond unidirectional flows from the host society to the place of origin and include more dynamic interactions between actors in different places (Levitt & Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Lacroix et al. Citation2016; Nowicka & Šerbedžija Citation2016). Through this broadened perspective, studies of remittances now include, for instance, the influence migrants might exercise on their home countries upon their return (Goldring Citation2004).

More recently, the term ‘political remittances’ has been used to further differentiate between these various intangible remittances. Here the emphasis is on the political content and potential impact of electoral and non-electoral engagement in migrants’ countries of origin (Pérez-Armendáriz & Crow Citation2010; Ahmadov & Sasse Citation2015, Citation2016; Meseguer et al. Citation2016), and also on the transmission of political principles, vocabulary and practices between places of origin and residence (Krawatzek & Müller-Funk Citation2020). Some scholars have gone as far as arguing that migrants act as ‘new and unaccounted power groups’ (Itzigsohn & Villacrés Citation2008) and ‘vectors of … mass-level … democratic diffusion’ (Pérez-Armendáriz & Crow Citation2010).

We expand previous scholarship on migrant transnationalism and the premise of multidirectional flows by focusing entirely on citizens in the country of origin: we compare individuals with transnational links to those without such links. Moreover, we extend the notion of ‘transnational experiences’ beyond the personal experience of migration to include links with family or friends who have migrated (referred to as ‘close ties’), the receipt of financial remittances, and international travel for leisure or work. We hypothesise that transnational links are an intrinsic part of the attitudes of those who maintain these links. We should, therefore, be able to trace the patterns that characterise the relationship between transnational links and attitudes, such as trust in national institutions or foreign policy preferences, and political behaviour, such as voting or protest participation. By tracing whether personal links to a particular region of the world relate to preferences for closer cooperation with that region, we widen our perspective beyond a focus on the effect of transnational influences on domestic politics.

The survey data we have collected on young Russians cannot answer the question of whether transnational links actually shape attitudes, or whether pre-existing attitudes are being maintained through a series of transnational experiences and networks. However, identifying consistent patterns between transnational links and attitudes would highlight the relevance of these links and their persistence. On this basis, new hypotheses can be generated for future research on the mechanisms behind the change or preservation of attitudes through transnational links.

Russian youth and transnationalism

Young age is a factor in predicting transnational mobility. Migration peaks at a young age (Wilson Citation2010), around the time when people are making their first independent educational decisions (Patiniotis & Holdsworth Citation2005; Dustmann & Glitz Citation2011). Students tend to move around domestically and internationally for their higher degrees before deciding where they will settle more permanently. The mobility of young Russians is particularly high, with a substantial percentage participating in the globalisation of education and labour markets (Smith et al. Citation2014). Russian youth, moreover, migrate to very diverse places internationally and nationally. Annual out-migration from Russia is estimated to be about 150,000–200,000 people, and young people, aged 16–29, make for around 30% of the total (Ryazantsev & Lukyanets Citation2016, pp. 487–89). At the same time, young people are highly mobile within Russia itself (Mkrtchyan Citation2013) and move within the countries of the former Soviet Union, aided by the widespread use of Russian, but also settle in the growing economies of Asia, as well as the United States or Canada and Europe, attracted by new educational opportunities, strong labour markets, and social and political considerations.

In a 2019 Gallup poll, a record 20% of the Russian population expressed a desire to leave their country.Footnote5 Out-migration has fuelled the country’s demographic imbalance and has led to a shortage of highly qualified labour, with provincial areas beings particularly affected (Kashnitsky Citation2020). According to the Gallup poll, among 15–29-year-old Russians, a staggering 44% indicated that they would like to move to another country; Germany (chosen by 15%) and the United States (chosen by 12%) were the most popular destinations mentioned. Of course, voicing your desire to migrate does not equate to actually migrating, but these numbers do convey an impression of the widespread frustration among young people about the state of affairs in their country and their transnational orientation.

The prevalence of social and other online media usage among the younger generation is an important element of the transnational links. Russia’s ‘digital natives’ differ sharply from older generations in the way they consume political and other news, with 65% of young people aged 18–34 getting their news online in 2020. Many young people no longer own a television.Footnote6 Online media underpin online and offline transnational networks based on both strong and weak ties. They channel information, personal experiences and impressions across geographical spaces and provide reference points for assessing one’s own context.

For the purposes of our study, we defined an upper age limit of 34, representing the cohort most likely to have extensive transnational links through personal migration, travel or active transnational networks beyond Russia. Transnational networks may also transmit the idea that it is not desirable to live in a specific place for economic, social or political reasons. It is, therefore, not a foregone conclusion that the relationship between transnational ties and a more critical attitude towards political institutions is mutually reinforcing. Scholars have underlined the difficulty faced by young migrants when trying to integrate socially and economically into their new places of residence. Indeed, migration, both domestic and international, does not necessarily make young Russians more upwardly mobile. Instead, it seems that migration in post-Soviet Russia might also reproduce existing social stratifications, because when migrants struggle to integrate, they cannot take advantage of educational and economic opportunities in their new places of residence (Eastman Citation2013). Young Russians, moreover, migrate at a comparatively early age, given that university is often the driving factor and admission usually takes place at the age of 17 or 18 (Kashnitsky et al. Citation2016). To add to this, those young people who have left provincial areas are far less likely to return than those who leave major urban centres (Florinskaya Citation2017).

Arguably, the attitudes of youth provide insights into expectations politicians have to take into account if they want to offer a more long-term perspective in their policies. The younger generation can also be seen as an important litmus test for assessing the Russian regime’s success in shaping the public mood. The extent to which youth has been at the centre of political attention in Russia is indeed striking. Inspired by the role of youth in a series of ‘colour revolutions’ in Eastern Europe, the Russian state created organisations such as Nashi and Rossiya molodaya in the first decade of this century to proactively mobilise and manage youth in an attempt to stabilise the system against internal and external threats (Lassila Citation2012; Krawatzek Citation2018). Russian state policies are not an exception in this regard, as the analysis of Belarus in this special issue highlights (Nizhnikau & Silvan, this issue). In Russia, the official strategy of the Putin administration has changed over time: the high visibility of public displays of regime support based on a top-down organisational network in the immediate aftermath of the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine has been replaced by more long-term measures to train youth as the bearer of the conservative social and political values propagated by the regime, for example through changes to the school history curriculum, as Schwenck illustrates in this collection.

Taken together, young people play an important and as yet underexplored role in Russian politics, while also taking an active interest in emigration or already having migration experience and being the cohort participating most intensively in online transnational networks through web-based and social media communication.

Data, research design and analytic strategy

We conducted online surveys of Russian youth in 2018 and 2019, implemented by the UK-based agency R-Research. Our 2018 online survey was conducted shortly after the presidential elections of 2–9 April (n = 2,018) and a second survey was carried out between 9 and 21 April 2019 (n = 2,019). Each survey included respondents aged 16–34 and living in the country’s 15 largest cities.Footnote7 We applied a quota-based sample (gender, age, educational level) and traced a wide range of characteristics, attitudes and behavioural patterns related to socio-political issues and respondents’ transnational experiences. We asked respondents, for instance, to rank their trust in several state institutions or other people, their own political involvement such as in elections or protests, media consumption and several questions related to their transnational experience such as having friends or family members abroad, receiving money from abroad or travel to other countries. For our analysis of the transnational connections of young Russians, including potential changes between 2018 and 2019, we merged both datasets. As we were dealing with cross-sectional data, we compared the two samples through ordinal and binary logistic regression models, based on the dependent variable, and controlled for the main socio-demographic differences between the samples.

Respondents were invited to the survey drawing on an actively managed panel of individuals who are willing to take part in social and political surveys as well as market-research. The panel provider regularly verifies that information about an individual's income, family status or place of residence are correct to screen-out respondents who provide inconsistent information. Through such basic demographic information, the researchers could meet the required quotas for the underlying population of young people in urban centres. Respondents took on average 30 min to complete the survey. Compared to face-to-face surveys, which have become more difficult to implement in Russia, an online format has the advantage of ensuring a higher degree of anonymity in an authoritarian context. An online survey is also easier to exit if a respondent feels uncomfortable at any stage (additionally, the option ‘refuse to answer’ supplemented the standard ‘don’t know’). The online format also matched the communication practices of the demographic group we were interested in. Our survey sample cannot be taken to represent Russian youth in general, therefore, our analysis refers to its particular reference population.

Dependent variables

To measure transnational links, we combined several survey items. First, respondents were asked whether they currently had family or friends living in one of the following regions: the United States/Canada, the European Union (EU), the former Soviet Union (FSU) and Asia. They were then asked whether they themselves had lived or worked in any one of these regions during the previous year or whether they had received financial support from friends or family members living in these regions. Each of those three items (family/friends, live/work, financial aid) could be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. A final question asked whether respondents had travelled beyond Russia in the past 12 months.

Out of these four items, two different variables were generated measuring the type and intensity of transnational exposure the respondent had experienced. One variable measured whether a respondent had family/friends in, lived/worked in and/or received remittances from a certain region. The regional variable was 1 for every respondent who had either family/friends in that specific region, had lived/worked there or received remittances. The second variable combined a respondent’s overall transnational experience; in this variable four types of transnational experience were included, namely family/friends abroad, living/working experience abroad, receipt of remittances and personal experience of travel. Thus, the more connections a respondent had to foreign countries, the higher their value on this count variable.

We first tried to understand the characteristics of respondents who reported having transnational linkages. Using the above transnational dummy variable per region, we computed logistic regression models, measuring transnational experiences in each of the following regions: Asia, EU, FSU and US/Canada.Footnote8 We then used the count variable to further explore the socio-demographic profile of the individuals with more or fewer transnational links. The goodness-of-fit chi-squared test was insignificant, indicating that the data were not characterised by overdispersion. Therefore, we performed a Poisson regression with the transnational count variable as the dependent variable.

We also wanted to know more about the foreign policy orientation of young Russians. Respondents were asked with which single country they would like to see Russia having closer relations. This was an open question, that is to say, respondents could write down any country they liked. The answers to this question were then grouped into the four regions—US/Canada, Asia, EU and FSU—and dummy variables were created for the individual categories. Each of those dummy variables was introduced in a logistic regression model as a dependent variable. In each of the regressions, we introduced a region-specific transnational variable. For example, in the regression model with the EU as the preferred region for closer relations with Russia, we included a variable that measured whether a respondent had travelled to the region, had family/friends or living/working experience in the region, or received financial remittances from the EU (with ‘yes’ to any of these four options resulting in the value 1).

From the original variable on foreign relations preferences, a further dummy variable was created, grouping the countries according to OECD membership. Additionally, an ordinal variable was created that sorted countries from the foreign relation variable according to their level of democracy. To this end, we used the Polity VI index from 2017, ranging from –10 to 10.Footnote9 The foreign relations answers were sorted according to the level that had been assigned on the Polity VI scale. For these variables, rather than using the region-specific transnational variables, we created two groups by combining Asia and the former Soviet Union and then Europe, the US and Canada. A logistic regression was performed with regard to the OECD variable and an ordinal logistic regression was performed for the Polity variable.

We were also interested in domestic political preferences. Here we coded a dummy variable for voting preferences (1 = for all respondents who had voted for Vladimir Putin in March 2018 and a 0 for everyone who had voted for someone else). Respondents were also asked about their views on the legitimacy of protest. We created an ordinal variable ranging from 1 to 3, distinguishing between those who answered ‘yes, in all cases’ (3), ‘yes, in some cases’ (2) and those who said ‘no, never’ (1). Finally, we enquired about actual protest participation in social/political or environmental protests.

A final battery of questions on political attitudes probed the respondents’ trust in several institutions, including the Russian army, the Russian security forces, non-governmental organisations, the Russian Orthodox Church, Russian mass media, local government, their regional governor and the Russian president. The answer categories were on a four-point scale ranging from ‘do not trust at all’, ‘tend not to trust’, to ‘tend to trust’ and ‘completely trust’.

Control variables

In order to investigate the change in our dependent variables from 2018 to 2019, a dummy variable was generated (2018 sample = 0 and 2019 sample = 1). Standard socio-demographic variables were introduced as controls. For age, we grouped respondents into four categories: 16–20, 21–26, 27–30 and 31–34, which corresponded to thresholds identified in the data. Gender was measured using a dummy variable (male = 1; female = 0). Wealth was measured by using the answers to the question about the respondents’ ability to afford certain goods. This continuous variable ranged from 1 (‘There is not enough money even for food’) to 7 (‘We experience no material difficulties; if needed we could purchase an apartment’) with a mean of 4.36 in 2018 and 4.39 in 2019. Furthermore, a simplified variable indicating the educational level of the respondent was introduced, reducing a nine-level scale to a four-point scale of primary and incomplete secondary education (1), complete secondary, incomplete higher education and complete higher education (4). The mean value for 2018 was 3.09 and for 2019, 3.01.

To measure the urban context of a respondent, a dummy variable was generated for all respondents living in Moscow or in St Petersburg (1) versus all individuals living in the other 13 regional cities (0). In both years of the survey around half of our respondents came from Moscow or St Petersburg, mirroring the relative population share of these two cities among Russia’s largest cities. A second dummy variable was introduced measuring whether a respondent had children under the age of 16 (1 = yes; 0 = no) with fewer than half of our respondents indicating that they were parents. Church attendance was captured by a variable that asked respondents how often they attended church. This variable was a five-level variable ranging from 0 for those who were not believers, to 1 for those who self-identified as religious but ‘never or almost never’ attended church, to 5 for those who attended a ‘few times a week’. This was introduced as a continuous variable and the mean in both years was 1.3 with a standard deviation of 1.2, underlining that the sample included a non-negligible share of people who frequently attended church.

Finally, respondents were asked about their main source of information about politics. The list of different sources included Russian state television, Russian radio, newspapers, social media and web-based media as well as international media. The most frequently named category was Russian television, still listed as the main source of information by a third of respondents. This response was singled out and recoded to a dummy variable (Russian television as first choice = 1, and other sources of information = 0).

Discussion of findings

Connectedness beyond Russia

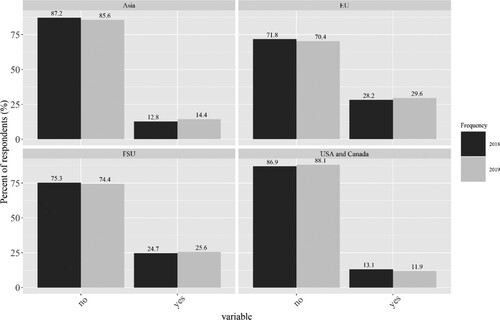

The majority of respondents did not have any of the four transnational links (see ). Over one-quarter of respondents had links to the EU and to FSU countries, and only around 13% had personal links to the US/Canada and Asia respectively. The descriptive results for both survey years suggest that across all destinations, transnational ties remained relatively stable between both years.

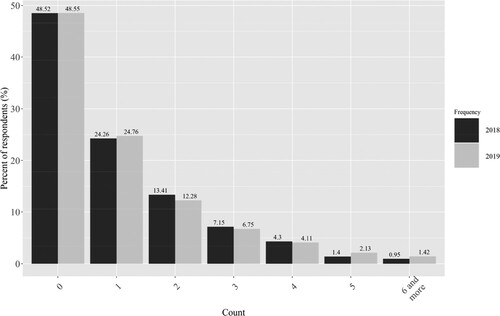

presents the descriptive statistics of the transnational count variable. Nearly half of the respondents (49% in both years) had no transnational experience at all; 24% had one type of transnational link and around 13% reported two types of link. The highest count in our dataset was eight.

We first examined the profiles of the respondents who reported having transnational links and looked for potential changes in these profiles between the two years (see ). The descriptive statistics reported above suggested a slight increase in the intensity of transnational ties from 2018 to 2019, but this change failed to reach levels of statistical significance. Across both years, a higher level of education had a significantly positive effect on links to all transnational destinations. The likelihood of having links to Asia increased by 34%, to the EU by 12%, to FSU countries by 19% and to the US/Canada by 35%.

TABLE 1 Factors Determining Transnational Links with …

With each higher value on the wealth-variable, the likelihood of having transnational links to the US/Canada or Asia increased and, to a somewhat lesser extent, to the EU. The odds of men having links to EU countries were lower than the odds of women having those links, but the reverse was true of links to FSU countries. Furthermore, being based in Moscow or St Petersburg, compared to being based in the other 13 cities, increased the likelihood of having personal links to any of the regions, but in particular to EU countries and Asia, followed by FSU countries and US/Canada. Clearly, this pattern speaks to the kind of people who live in the two capitals and how internationally connected these two cities are. There was no statistically significant difference regarding age.

The Poisson regression for the aggregated transnational count variable revealed that for the older age category within our youth cohort, the incidence-rate ratio decreased in relation to the count variable measuring transnational links. The incident-ratio of the wealthier respondents increased by 15% and of the more highly educated respondents by 20%, and for people living in Moscow or St Petersburg by 60%. Thus younger people, those with more education, those with more wealth and those based in Russia’s two largest cities were the most transnationally networked individuals.

Transnational links and foreign policy orientation

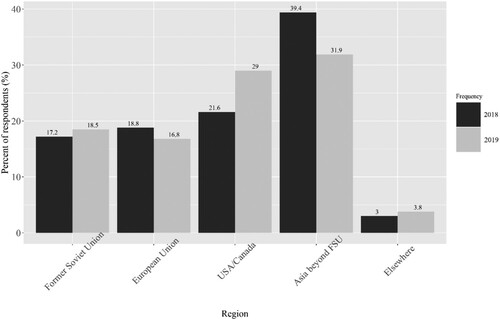

presents the respondents’ foreign policy preferences aggregated in terms of their opinion about the single region with which Russia should have closer relations. The region most favoured in 2018 for close relations with Russia was Asia beyond the former Soviet Union, with around 39% of the respondents saying that they would like Russia to have closer relations with a country in the region. US/Canada, the EU and FSU countries were similarly popular among respondents in 2018 (about 20%). Only around 4% of respondents favoured closer relations with other countries beyond those four core regions. In 2019, US/Canada and Asia were equally popular, with each chosen by about 30% of the respondents, indicating a significant shift away from seeing closer relations with Asia as desirable. This may well be related to the deterioration in Russia’s relationship to the United States over that time period and respondents’ awareness that relations ought to be less confrontational. Furthermore, the European Union and countries of the FSU were mentioned slightly less in 2019 (17% and 18% respectively).

FIGURE 3. With a Country from which Region in the World would you most like Russia to have a Closer Relationship?

Note: Data from survey of 2,000 Russians, aged 16–34.

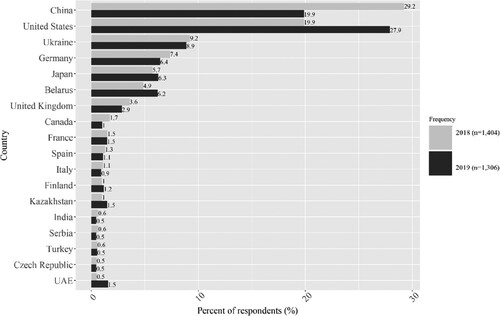

The most frequently mentioned single country that respondents felt Russia should have closer relations with in 2018 was China (29%), followed by the United States (20%) (see ). Those figures were reversed in the 2019 sample, in which the United States was the most frequently mentioned country (28%) followed by China (20%). Ukraine came third in both years with around 9%, at a point in time when the actual relationship between the two countries had been tense for several years. With 7% and 6%, respectively, Germany was the most important EU country singled out by young Russians in both years. Taken together, all the EU member states mentioned individually by the respondents added up to about 19% of the respondents, representing a similar share to those prioritising closer relations with the US in 2018 and China in 2019.

FIGURE 4. With which ONE Country in the World would you most like Russia to have a Closer Relationship?

Note: Data from survey of 2,000 Russians, aged 16–34.

Over 60% of our respondents (66% in 2018 and 64% in 2019) favoured closer relations with non-OECD countries, while only 34% and 36% respectively favoured closer relations with OECD countries. Yet, more than half of the respondents in both years wished for closer connections with more democratic countries, and only a third favoured stronger relations with non-democratic countries.

How significant are these descriptive insights and the shifts between 2018 and 2019 once we control for other factors? Without comparing the two survey years directly, the wish for closer relations with the United States and Canada was significantly higher in 2019 (by 44%), while the wish for links to Asia and the European Union was far less pronounced (about 30% and 15% lower respectively). We found transnational links to be the most substantive indicator of foreign policy attitudes in both years. shows the regression results for the foreign relations variables as dependent variables.

TABLE 2 Russia Should Have Closer Relations with …

With the exception of Asia, the combination of transnational links was a highly significant and strong positive predictor for a person’s hope for Russia to have closer relations with countries in a given region. Transnational links to the European Union more than doubled the odds of desiring closer relations with the EU; transnational links to FSU countries doubled the chances of an orientation towards this region; links with North America increased the odds of expressing the wish for closer relations with these two countries by 60%. Around 15% of respondents indicated that one of their parents was born in another FSU country. The family ties that may go along with a parent’s place of birth is a potential explanation for the desire to have closer relations with countries of that specific region. The relevance of parents’ birthplace speaks to the importance of underlying transnational ties based on family networks trumping other factors such as education or wealth.

Closer relations with Asia appeared particularly desirable to respondents not living in Moscow or St Petersburg, reflecting the logic of how Russia’s geography relates to the international outlook of its young citizens. Those based in Moscow or St Petersburg tended to choose FSU countries as their favoured international partners—here one might have expected an equally pronounced orientation towards the European Union or the United States/Canada; however, this was not a significant explanatory factor. Additionally, media consumption correlated with foreign policy orientation: those whose main source of information was Russian state television were more likely to orient themselves towards Asia and other FSU countries and significantly less likely to be oriented towards the US/Canada. Men and individuals with a higher level of reported religiosity were also more likely to look towards countries of the former FSU; however, men were also more likely to desire closer relations with the US/Canada.

The older a person was (within our youth cohort) and the degree to which they used Russian state television as their most important source of information significantly reduced the odds that they would single out the US/Canada as the countries with which Russia should have closer relations. By comparison, male respondents were 30% more likely to favour closer relations with the US/Canada than women, with wealth also increasing the likelihood that respondents would choose this option. In addition to pre-existing migration connections across the FSU, these results might also have reflected the current political confrontation between Russia and the European Union and the United States/Canada.

shows the results of the regression analysis based on the political characteristics of the respective countries (OECD member and polity score). There was a significant increase between 2018 and 2019 in respondents preferring closer relations with OECD countries and those with a higher Polity score. Links to US/Canada or Europe were clearly correlated with closer relations to OECD countries (and those with a higher Polity score), whereas links to FSU countries reduced this likelihood. Of the social controls, wealth was positively associated with the desire for closer relations with an OECD country (increasing the odds by 11%), whereas increased age and not having children reduced these odds substantially. The more religious respondents were also less likely to desire closer links with OECD countries or those with a higher Polity score.

TABLE 3 Foreign Policy Attitudes: Closer Relationship with …

Domestic politics, trust and transnational links

The transnational links maintained by our respondents were systematically related to their domestic political attitudes (see ). Our analysis suggests that personal links to Europe and US/Canada were associated with a much more critical perspective on domestic politics in Russia, whereas links to FSU countries and Asia did not seem to matter in the assessment of domestic politics.

TABLE 4 Domestic Political Attitudes and Behaviour: Russia 2018–2019

With respect to voting behaviour, the more transnational connections individuals had to EU countries or US/Canada, the lower the likelihood that they voted for President Vladimir Putin in 2018. The effect was highly significant and substantive as it reduced the odds by 43%, whereas links to FSU countries or Asia did not relate to the likelihood of having voted for Putin, also illustrating what type of links are more politicised between Russia and various countries of destination. Moreover, men were significantly less likely to have voted for Putin (by 43%), as were people with a higher level of education (by 15%). By comparison, people who regularly attended church and those with children were more likely to have voted for Putin in the past.

Personal links to EU countries and the US/Canada related to a significantly higher likelihood of viewing protests as ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ legitimate. However, links to FSU countries or Asia did not affect attitudes towards protests, in line with the attitudes on voting behaviour. Beyond the transnational connections, a person’s level of education made it more likely that they would view protests as legitimate, though this decreased with age. Along similar lines, links to EU countries or the United States and Canada related to a significantly higher likelihood of having participated in protests, as did being younger and being male.

The level of trust in a state's key institutions is a critical dimension for assessing the strength of a political system, be it democratic or authoritarian. In we sum up the results of several trust-related ordinal logistic regressions. For a number of Russian institutions, average trust decreased significantly from 2018 to 2019, including trust in the president (46%), state media (20%), the army (26%) and the security forces (21%). Personal transnational contact with US/Canada or the European Union was clearly linked to lower trust levels across key institutions. Westward transnational exposure thus correlated with a more sceptical attitude towards domestic political institutions. Inversely, links to FSU countries or Asia were associated with higher trust in the president and the mayor in respondents’ respective cities. Our analysis revealed a persistent congruity between personal links to democratic countries and sceptical attitudes towards key institutions in Russia, and a correlation between links to other (semi)authoritarian states and higher trust in the political executive in the authoritarian country of origin. In both cases, respondents may have held these views before they became transnationally connected; in fact, their attitudes may have made the establishment of these transnational links more likely, due to the out-migration of family members and like-minded peers. However, our data allowed us to test the strength of these connections at different points in time. Therefore, even if transnational exposure was not necessarily the critical causal factor that lowered trust in authoritarian institutions, the transnationalism–trust nexus was strong, as the above analysis demonstrates.

TABLE 5 Trust in Key State Institutions: Russia 2018–2019

Beyond transnational exposure, a number of controls affected respondents’ trust in institutions. Female respondents reported lower trust in a variety of institutions, such as the president, the media, the church, NGOs and security forces. While wealth significantly increased trust in almost all instances, with the exception of the church, the opposite held true for higher levels of education, which, in turn, was associated with lower trust in the president, the local mayor, the media, the army, the church and security forces. Additionally, some socio-demographic variables were associated with trust in a single institution or a small number of institutions. Being a resident of Moscow or St Petersburg, for instance, increased the odds that a respondent trusted the local mayor, while having children increased trust in the president, the state media, the army and the church. As might be expected, people who attended church more regularly tended to trust the Russian Orthodox Church, but they also had more trust in mass media, the president, the governor of their region and their local mayor.

Conclusion

Conceptually and empirically, our analysis demonstrates that the notion of ‘transnational social fields’ needs to include a focus on non-migrants in countries of origin with a range of transnational links beyond personal migration experience. Our focus on a sub-section of the population—the young—in a country like Russia that is experiencing significant (and potentially increasing) out-migration and growing digital interconnectedness, helped us trace the relationship between personal transnational experiences and political attitudes related to foreign policy and domestic politics, namely perceptions of the legitimacy of protest and voting preferences.

The analysis presented in this essay proceeded in two steps. It first unpacked the profile of young Russians with a range of transnational experiences, including but not limited to personal migration. Socio-demographic factors highlighted in migration studies generally have been found to be relevant in this case: higher education and income levels as well as gender are closely linked to transnational exposure (the latter varies depending on region). The profile of those with transnational exposure did not change significantly from 2018 to 2019.

At the heart of this essay was the question of whether personal transnational links and, by extension, the networks underpinning these links were associated with domestic and foreign policy preferences. We found that the direction and extent of transnational exposure was indeed a significant predictor of the reported foreign policy preferences. Disentangling the various types of transnational linkages, we found that, in particular, those who had family members living in a specific country or region favoured Russia’s closer relationship with that country or region. The effects were strong for relations with the EU, the US/Canada, and the FSU across both years, despite a significant change in the overall orientation towards China and the US. In other words, personal experiences and prior socialisation trumped regime-related considerations. Thus, Granovetter’s thesis does not hold in this regard, and it is in fact strong rather than the weak ties that predict foreign policy preferences and attitudes to domestic politics, including protest legitimacy and trust in various institutions.

Comparing the 2018 and 2019 data in as far as it is possible, we were also able to show that an individual’s transnational connections are clearly linked to lower trust in a variety of state institutions such as the army, the security forces, the media and the Russian Orthodox Church. Ideas, norms and money transmitted via transnational connections may bring about, maintain or reinforce a generally low level of trust in a very diverse set of political institutions. Our analysis of the attitudes of young Russians adds to the evidence that pressure on the regime is growing. Migration intentions alone send an important signal: the regime needs to find responses to the expectations of the younger generation. The association between transnational links and lower levels of trust in domestic political institutions and belief in the legitimacy of protest deepens this challenge.

Further fine-grained analysis of each of the recorded transnational connections, including the motivations for migrating to particular destinations alongside their political regime types, is necessary to unpack these dynamics further. Our data and, to our knowledge, other existing data do not yet allow us to tease out the causality behind the correlations demonstrated in this essay. Thus, we cannot establish if these transnational connections induce certain political attitudes or whether our respondents already held these views before establishing transnational connections. Perhaps their predispositions enabled them to build these links in the first place, or they have preserved or reinforced them. Here an experimental or qualitative research design could help to unpack whether, in an individual’s own perception, personal transnational links shape political attitudes on domestic politics and foreign policy. However, the strong correlation between transnational links and domestic and foreign policy attitudes itself is a novel dimension that deserves further attention in scholarly and policy circles. It suggests a split that is at least maintained, if not caused by an individual’s transnational links. This is an important insight for future research that seeks to determine how the transnational impacts on domestic political attitudes in an increasingly interconnected world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Félix Krawatzek

Félix Krawatzek, Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), Mohrenstraße 60, 10117, Berlin, Germany. Email: [email protected]

Gwendolyn Sasse

Gwendolyn Sasse, Humboldt University of Berlin & Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), Germany. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 International Migration Report 2017, United Nations, available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf, accessed 16 May 2022.

2 ‘Inoi russkii mir’, Proekt, 16 January 2019, available at: https://www.proekt.media/research/statistika-emigration/?utm_source=tlgrm&utm_medium=chnl&utm_campaign=migr, accessed 16 May 2022.

3 ‘One Out of Five Russians Wants to Leave the Country. Here’s Who They Are’, Washington Post, 12 August 2019, available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/08/12/one-out-five-russians-wants-leave-country-heres-who-they-are/, accessed 16 May 2022.

4 ‘Migration and Youth: Challenges and Opportunities’, Global Migration Group, available at: https://www.globalmigrationgroup.org/system/files/2._Executive_Summary_0.pdf, accessed 16 May 2022.

5 ‘Record 20% of Russians Say They Would Like to Leave Russia’, Gallup, available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/248249/record-russians-say-leave-russia.aspx, accessed16 May 2022.

6 Rossiiskii medialandshaft-2020, Levada Centre, 28 April 2020, available at: https://www.levada.ru/2020/04/28/rossijskij-medialandshaft-2020/, accessed 16 May 2022.

7 Moscow, St Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Ekaterinburg, Kazan, Krasnoyarsk, Nizhnii Novgorod, Chelyabinsk, Omsk, Rostov-on-Don, Ufa, Samara, Voronezh, Perm and Volgograd.

8 Logistic regression results are reported as odds ratios.

9 The following countries/regions did not have a Polity score for 2017: Iceland, Dubai, EU, Kazakhstan (only data for 2016).

References

- Adida, C. & Girod, D. (2011) ‘Do Migrants Improve Their Hometowns? Remittances and Access to Public Services in Mexico, 1995–2000’, Comparative Political Studies, 44, 1.

- Ahmadov, A. & Sasse, G. (2015) ‘Migrants’ Regional Allegiances in Homeland Elections: Evidence on Voting by Poles and Ukrainians’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41, 11.

- Ahmadov, A. & Sasse, G. (2016) ‘A Voice Despite Exit: The Role of Assimilation, Emigrant Networks, and Destination in Emigrants’ Transnational Political Engagement’, Comparative Political Studies, 49, 1.

- Ahmed, F. (2012) ‘The Perils of Unearned Foreign Income: Aid, Remittances, and Government Survival’, American Political Science Review, 106, 1.

- Bade, K. J. (2003) Migration in European History (Malden, MA, Blackwell).

- Bakewell, O., Engbersen, G., Fonseca, M. L. & Horst, C. (2016) Beyond Networks: Feedback in International Migration (Basingstoke, Palgrave).

- Barry, C. M., Clay, K. C., Flynn, M. E. & Robinson, G. (2014) ‘Freedom of Foreign Movement, Economic Opportunities Abroad, and Protest in Non-Democratic Regimes’, Journal of Peace Research, 51, 5.

- Basch, L., Glick-Schiller, N. & Blanc-Szanton, C. (1994) Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States (London, Gordon & Breach Science).

- Bommes, M. (2011) ‘Migrantennetzwerke in der funktional differenzierten Gesellschaft’, in Bommes, M. & Tacke, V. (eds) Netzwerke in der funktional differenzierten Gesellschaft (Wiesbaden, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften).

- Burgess, K. (2014) ‘Unpacking the Diaspora Channel in New Democracies: When Do Migrants Act Politically Back Home?’, Studies in Comparative International Development, 49, 1.

- Castles, S. (2000) ‘International Migration at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century: Global Trends and Issues’, International Social Science Journal, 52.

- Délano, A. & Gamlen, A. (2014) ‘Comparing and Theorizing State–Diaspora Relations’, Political Geography, 41.

- Diani, M. (2013) ‘Networks and Social Movements’, in Snow, D., Della Porta, D., Klandermans, B. & McAdam, D. (eds) The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements (Hoboken, NJ, Wiley).

- Doyle, D. (2015) ‘Remittances and Social Spending’, American Political Science Review, 109, 4.

- Dustmann, C. & Glitz, A. (2011) ‘Migration and Education’, in Hanushek, E., Machin, S. & Woessmann, L. (eds) Handbook of the Economics of Education (Amsterdam, Elsevier).

- Eastman, J. (2013) ‘Youth Migration, Stratification and State Policy in Post-Soviet Russia’, Sociology Compass, 7, 4.

- Elrick, T. & Lewandowska, E. (2008) ‘Matching and Making Labour Demand and Supply: Agents in Polish Migrant Networks of Domestic Elderly Care in Germany and Italy’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34, 5.

- Faist, T. (2000) The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and Transnational Social Spaces (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Farré, L. & Fasani, F. (2013) ‘Media Exposure and Internal Migration—Evidence from Indonesia’, Journal of Development Economics, 102, C.

- Florinskaya, Y. F. (2017) ‘School Graduates from Small Towns in Russia: Educational and Migration Strategies’, Studies on Russian Economic Development, 28, 1.

- Gallo, E. (2013) ‘Migrants and Their Money are not all the Same: Migration, Remittances and Family Morality in Rural South India’, Migration Letters, 10, 1.

- Glick Schiller, N., Basch, L. & Blanc-Szanton, C. (1992) ‘Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 645, 1.

- Goldring, L. (2004) ‘Family and Collective Remittances to Mexico: A Multi-Dimensional Typology’, Development & Change, 35, 4.

- Granovetter, M. (1973) ‘The Strength of Weak Ties’, American Journal of Sociology, 78, 6.

- Haug, S. (2008) ‘Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34, 4.

- Itzigsohn, J., Cabral, C. D., Medina, E. H. & Vazquez, O. (1999) ‘Mapping Dominican Transnationalism: Narrow and Broad Transnational Practices’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22, 2.

- Itzigsohn, J. & Villacrés, D. (2008) ‘Migrant Political Transnationalism and the Practice of Democracy: Dominican External Voting Rights and Salvadoran Home Town Associations’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31, 4.

- Kapur, D. (2014) ‘Political Effects of International Migration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 17.

- Kashnitsky, I. (2020) ‘Russian Periphery is Dying in Movement: A Cohort Assessment of Internal Youth Migration in Central Russia’, GeoJournal, 85.

- Kashnitsky, I., Mkrtchyan, N. & Leshukov, O. (2016) ‘Interregional Migration of Youths in Russia: A Comprehensive Analysis of Demographic Statistics’, Educational Studies Moscow, 13, 3.

- Keck, M. & Sikkink, K. (1998) ‘Transnational Advocacy Networks in the Movement Society’, in Meyer, D. & Tarrow, S. (eds) The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for a New Century (Lanham, MD, Rowman & Littlefield).

- Koinova, M. & Tsourapas, G. (2018) ‘How do Countries of Origin Engage Migrants and Diasporas? Multiple Actors and Comparative Perspectives’, International Political Science Review, 39, 3.

- Krawatzek, F. (2018) Youth in Regime Crisis: Comparative Perspectives from Russia to Weimar Germany (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Krawatzek, F. & Müller-Funk, L. (2020) ‘Two Centuries of Flows Between “Here” and “There”: Political Remittances and Their Transformative Potential’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46, 6.

- Krawatzek, F. & Sasse, G. (2018) ‘Integration and Identities: The Effects of Time in Migration, Migrant Networks, and Political Crises on Germans in the US’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 60, 4.

- Lacroix, T., Levitt, P. & Vari-Lavoisier, I. (2016) ‘Social Remittances and the Changing Transational Political Landscape’, Comparative Migration Studies, 4, 16.

- Lassila, J. (2012) The Quest for an Ideal Youth in Putin’s Russia II: The Search for Distinctive Conformism in the Political Communication of Nashi, 2005–2009 (Stuttgart, Ibidem-Verlag).

- Levitt, P. (1998) ‘Social Remittances: Migration Driven Local-Level Forms of Cultural Diffusion’, International Migration Review, 32, 4.

- Levitt, P. (2001) The Transnational Villagers (Berkeley, CA, University of California Press).

- Levitt, P. & Lamba-Nieves, D. (2011) ‘Social Remittances Revisited’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37, 1.

- Liu, H. (2005) The Transnational History of a Chinese Family: Immigrant Letters, Family Business, and Reverse Migration (New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press).

- Massey, D. & Espana, F. (1987) ‘The Social-Process of International Migration’, Science, 237, 4816.

- Mata-Codesal, D. (2013) ‘Linking Social and Financial Remittances in the Realms of Financial Know-How and Education in Rural Ecuador’, Migration Letters, 10, 1.

- McKenzie, D. & Rapoport, H. (2007) ‘Network Effects and the Dynamics of Migration and Inequality: Theory and Evidence from Mexico’, Journal of Development Economics, 84, 1.

- Meseguer, C. & Burgess, K. (2014) ‘International Migration and Home Country Politics’, Studies in Comparative International Development, 49, 1.

- Meseguer, C., Lavezzolo, S. & Aparicio, J. (2016) ‘Financial Remittances, Trans-Border Conversations, and the State’, Comparative Migration Studies, 4, 1.

- Miller, G. L. & Ritter, E. H. (2014) ‘Emigrants and the Onset of Civil War’, Journal of Peace Research, 51, 1.

- Mkrtchyan, N. V. (2013) ‘Migration of Young People to Regional Centers of Russia at the End of the 20th and the Beginning of the 21st Centuries’, Regional Research of Russia, 3, 4.

- Nowicka, M. & Šerbedžija, V. (2016) ‘An Introduction to the Debate Migration and Remittances in a Global Europe’, in Nowicka, M. & Šerbedžija, V. (eds) Migration and Social Remittances in a Global Europe (Basingstoke, Palgrave).

- Patiniotis, J. & Holdsworth, C. (2005) ‘“Seize That Chance!” Leaving Home and Transitions to Higher Education’, Journal of Youth Studies, 8, 1.

- Pérez-Armendáriz, C. & Crow, D. (2010) ‘Do Migrants Remit Democracy? International Migration, Political Beliefs, and Behavior in Mexico’, Comparative Political Studies, 43, 1.

- Pries, L. (2001) New Transnational Social Spaces: International Migration and Transnational Companies in the Early Twenty-First Century (London, Routledge).

- Regan, P. M. & Frank, R. W. (2014) ‘Migrant Remittances and the Onset of Civil War’, Conflict Management and Peace Science, 31, 5.

- Risse-Kappen, T. (1995) Bringing Transnational Relations Back In: Non-State Actors, Domestic Structures, and International Institutions (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Ryazantsev, S. & Lukyanets, A. (2016) ‘Emigration of Young People from Russia: Forms, Trends and Consequences’, Vestnik Tadzhikskogo Universiteta Prava, Biznesa i Politiki. Ser. Obshchestvennykh Nauk, 15, 23.

- Smith, D. P., Rérat, P. & Sage, J. (2014) ‘Youth Migration and Spaces of Education’, Children’s Geographies, 12, 1.

- Vertovec, S. (2009) Transnationalism (London & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Wilson, T. (2010) ‘Model Migration Schedules Incorporating Student Migration Peaks’, Demographic Research, 23, 8.

- Wimmer, A. & Glick Schiller, N. (2002) ‘Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation–State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences’, Global Networks, 2, 4.

- Zahra, T. (2016) The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World (New York, NY, W. W. Norton & Company).