Abstract

This essay discusses the interplay of nationalism and internationalism amongst Soviet youth from the 1960s to the early 1980s, arguing that there was much that united the language, underlying concepts and problems of these political agendas. More than that: they were mutually constitutive, while mobilising youth and generating enthusiasm and anger on a large scale. At the same time, national and international questions became more republicanised in these years: they were experienced and tackled differently across the republics. To show this, the essay discusses a range of archival materials and published sources from Soviet Armenia, Central Asia and Ukraine.

In the mid-1970s, international student exchanges were common across the Soviet Union, from Leningrad to Yerevan and from Odessa to Alma-Ata. Following a series of bilateral agreements with various countries over the previous two decades, educational institutions and the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) welcomed ever-growing numbers of students from the socialist bloc and from capitalist and developing countries. Some came to study, others for short educational or recreational stays, while students from socialist and developing countries also came to take part in festivals, competitions and international construction projects.

In February 1975, the Komsomol at Yerevan Polytechnical Institute invited young locals to join Polish and Hungarian students later that year at Lake Sevan, in the mountains about two hours north of the Armenian capital, to form what was known as an ‘international student construction brigade’ (internatsional’nyi studencheskii stroitel’nyi otryad—ISSO).Footnote1 A hundred applications were received for a total of 40 places, which were given to local Komsomol (37) or Communist Party (3) members, all Armenian by nationality.Footnote2 The name chosen for the ISSO was ‘Nairi’, an Assyrian word referring to Armenian highland tribes thousands of years ago.Footnote3

On 30 June, 45 young activists travelled to Sevan, where they were assigned two run-down floors of a vocational school’s hall of residence.Footnote4 When the guests arrived a few days later, the groups were split into six brigades: the Armenians were divided into three and the Hungarians into two, while the Polish students formed one brigade. Each was assigned a different construction task. While the six units were thus separated by nationality, they mingled for political and social activities. Assisted by the local Komsomol, the organisers took the participants on excursions to factories, the attractive Sevan peninsula and the Dilijan nature reserve. The groups even attended the semi-final of the Soviet Football Cup to cheer for the eventual champions Ararat Yerevan.Footnote5 Folk music and sports events complemented the list of activities. For the readings and lectures, national themes were chosen, including ‘Armenia, Its History and Culture’ and ‘Yerevan Is 2,750 Years Old’. While the Armenian activists’ final report criticised the Polish group for being more focused on trading chewing gum, jeans and t-shirts with the local population, it praised the Hungarian students, with whom they had made some ‘great memories’, expressing their hope for ‘long and durable ties’ (see ).Footnote6

This opening vignette is not meant to offer new insights into the success or failure of internationalist projects but to highlight the importance of nationality in such projects, and in post-Stalinist society more broadly. International visiting programmes developed considerable appeal amongst youth and, since the titular nationalities of the Soviet Union’s constituent republics often dominated in the local state and party apparatuses, ‘local’ youth activism in the Armenian SSR largely meant Armenian youth activism. It is no coincidence that a name from pre-modern Armenian history (with strong national connotations) was chosen as the title for the internationalist project and that lectures and discussions focused on Armenian history. The only music mentioned in the report was folk music. The football match was an opportunity to see an Armenian club (which won the Soviet championship in 1973) beat sports giant Dinamo Tbilisi 3–1—a matter of national pride, all the more because the opponent was Georgian.Footnote7 There may have been practical reasons for organising the construction work by nationality (and language), but it also helped to enshrine the importance of nationality in internationalist experience. Ultimately, it was the presence of international guests that made local activists cultivate not only their Soviet but also their national identities.

This essay discusses the interplay of nationalism and internationalism after Stalin’s death by exploring the role of Komsomol-age youth, who were at the forefront of political activism.Footnote8 While the two agendas were opposites insofar as nationalism would later play no small role in tearing the union apart whereas internationalism was supposed to hold it together, there was much that united their language, underlying concepts and problems. More than that, they were mutually constitutive. One was barely conceivable, or would have been much weaker, without the other. Young people were key agents in this interplay of political projects: they were mobilised by state and party structures in great numbers but also took activism into their own hands, with results that could not be scripted. They reinforced, legitimated and challenged national, nationalist and internationalist agendas. This essay illustrates this process focusing on a timeframe spanning from the early 1960s to the early 1980s, when nationalism and internationalism turned into mass phenomena across the USSR and the Komsomol was transformed from a ‘revolutionary vanguard’, with highly selective recruitment, to a mass organisation covering two-thirds of the eligible age group. I argue that, far from being an era of stagnation, these years were highly dynamic because the two political projects generated both enthusiasm and anger on a large scale.Footnote9 At the same time, the national and international questions became more republicanised as they were experienced and tackled differently across the union republics. To show this, the essay discusses a range of archival materials and published sources, including conference papers and contemporary journals and newspapers, from Soviet Armenia, Central Asia and Ukraine.

In the early 1960s, people inside and outside party organisations began to explore cultural heritage, national histories and identity across the Soviet Union. Nation-building became as crucial as it had been in the 1920s but could now benefit from a more stable political climate. Simultaneously, the USSR expanded and intensified its ties with the outside world. With improving economic conditions, visitors were received from the socialist and capitalist worlds, and Soviet citizens started travelling abroad for work, study and recreation.

The existing literature treats the phenomena of Soviet internationalism and nationalism rather differently. For decades, internationalism was largely ignored as little more than a socialist propaganda tool. Soviet Central Asia and the Caucasus were assumed to be ‘cordoned off, isolated, and separated from much of the rest of the world’ (Gleason Citation2003, p. 2).Footnote10 Outside the socialist bloc, liberal internationalism also remained under-explored as its purported antipode, nationalism, was seen as far more important (Sluga Citation2013). In recent years, the USSR’s global connectivity—beyond foreign policy and support for communist parties—has received more attention, with some scholars arguing that the socialist world experienced its own forms of globalisation (Boden Citation2013; Kirmse Citation2018; Calori et al. Citation2019; Mark & Rupprecht Citation2019). Much research has focused on how national and supranational/Soviet identities were shaped by exposure to the West and, in some cases, Eastern Europe (Gorsuch & Koenker Citation2006; Zhuk Citation2010; Risch Citation2011; Roth-Ey Citation2011; Chernyshova Citation2013; Gilburd Citation2018; Wojnowski Citation2018). Those examining Soviet entanglements with the Global South (Matusevich Citation2008; Rajagopalan Citation2008; Rupprecht Citation2015; Babiracki & Jersild Citation2016; Katsakioris Citation2017) have contributed to our understanding of the scope and intensity of Soviet connectedness but, with few exceptions, have paid less attention to its impact on identity formation in the USSR, let alone Soviet nationalities.

Nations and nationalism have always been a focus of Soviet studies as a means of exposing the system’s neo-imperial nature and the brave resistance of its victims (Allworth Citation1971; Carrère d’Encausse Citation1978; Simon Citation1986; Huttenbach Citation1990; Nahaylo & Swoboda Citation1990). The systematic oppression of certain nations, such as the Crimean Tatars, received much attention, as did any form of resistance against Soviet rule (Remeikis Citation1980; Alexeyeva Citation1985; Rorlich Citation1986). Undoubtedly, the treatment of deported peoples was brutal, yet the argument that the Soviet Union was killing off or suppressing nations was applied far beyond these cases. After the Cold War, the idea that the Soviet Union had essentially repressed national feelings, which then naturally burst forth once liberalisation occurred under Gorbachev, remained strong.Footnote11

However, an increasing body of work has acknowledged what Slezkine called the ‘chronic ethnophilia of the Soviet regime’ (Slezkine Citation1994, p. 415): that the Bolsheviks consciously promoted and created nations and nationality as an inherent part of the Soviet project.Footnote12 Martin showed that it was this promotion of distinct national identities that the Soviet leadership would frame as the ‘friendship of the peoples’ from the mid-1930s (Citation2001, pp. 432–61). Newer research has also begun to demonstrate the compatibility of national and Soviet identities in the post-Stalin years (Suny Citation2012; Smith Citation2013; Hasanli Citation2015; Lehmann Citation2015). Eruptions of local nationalism were not so much examples of the resurgence of dormant nationalist sentiment after decades of repression but the direct result of sustained Soviet efforts at promoting titular nationalities (Rolf Citation2014). Indeed, as Smith suggests, the post-Stalin state took nation-building to new levels; by the time perestroika began, ‘the republics resembled modern nation-states’ (Smith Citation2013, p. 244). However, policies were not implemented and received in similar fashion across the USSR. Khalid’s analysis of cultural and religious practice in Soviet Uzbekistan and his pithy conclusion that ‘the Soviet regime indulged in the most ambitious—and successful—project of nation-building in human history’ (Khalid Citation2003, p. 579) may be no overstatement for Central Asia; yet the reality of Soviet policy looked different across the union. This essay therefore aims to explore how nationalism and internationalism informed each other, and to do so with a focus on regional differences.

It also enters contested terrain. The literature has become richer and more complex, yet there are still jarring discrepancies in interpretation. Crucially, there is a gap between research done in the West and that done in many of the former union republics, where talk of national repression, local resistance and primordial identities has become a key part of post-Soviet nation-building (Suny Citation2001, pp. 862–71).Footnote13 Even in the West, there is a notable discrepancy between academic and public discourse, as politicians, journalists and activists regularly repeat the cliché of the Soviet Union’s repression of nations.

Given the contested and politically sensitive nature of this research, it is important to address some methodological concerns at the outset. Saroyan’s (Citation1997) incisive critique of Sovietology, widely discussed amongst scholars of Soviet Islam but otherwise less known, offers a starting point. Until 1991, access to the USSR was limited for Western researchers, who therefore discussed internal Soviet developments mainly by referring to the Soviet press and other publications. Analysing their findings, Saroyan identified two interpretive strategies for reading Soviet sources: direct and indirect extrapolation (Saroyan Citation1997, p. 11). The first is based on the assumption that Soviet discourse, especially complaints in the press, reflected the ‘real’ situation, despite the fact that press polemics were often part of power struggles and that problems could be blown out of proportion just as much as they were in Western media. The second strategy assumed the opposite, namely that Soviet texts could only be used as raw material and had to be analysed with reference to Western categories. Few Western observers seemed worried that the decision whether Soviet sources could be trusted or had to be turned on their head was arbitrary. Saroyan’s analysis showed how the two strategies helped to paint a picture of Soviet Islam that had little to do with reality.

Similar problems prevailed in research on youth. Extrapolating directly from complaints in the party and Komsomol press, or émigré statements, scholars attributed widespread problems and cynicism to the young generation (Kassof Citation1965; Unger Citation1981; Fierman & Olcott Citation1988). Similarly, anti-Soviet nationalist activism, including but not limited to youth, was usually (and still tends to be) taken in good faith (Olcott Citation1990; Vardys & Sedaitis Citation1997; Nahaylo Citation1999; Zisserman-Brodsky Citation2003; Subtelny Citation2009). Internationalism, in turn, received the opposite treatment: viewed as ‘propaganda’, until recently it hardly featured in research on Soviet identities at all. What happened here was indirect extrapolation: we did not trust the text, so we ignored it. Studies of Soviet youth activism continue to neglect the non-Russian republics, where anti-Soviet nationalism presumably prevailed. Those who mention the non-Russian Komsomol after Stalin do so only in passing, usually with a note on how these activists aided nationalist agendas (Swain Citation2012; Hasanli Citation2015; Blauvelt & Smith Citation2016, pp. 182–84). This logic also applies to entire groups of archives. Files from secret service archives, now open in several postsocialist countries, have been reproduced to show ‘reality’ under socialist rule (Bekirova Citation2004; Smolii Citation2004; Bazhan Citation2016; Baberowski et al. Citation2021), while the detailed everyday material kept in party and youth organisation archives is rarely discussed alongside these holdings, other than to document decisions on clampdowns.

In order to avoid falling into this Sovietological trap, this essay starts from the premise that every document must be treated with the same critical distance and, ideally, be considered in relation to others. While this may seem to be stating the obvious, the different trajectories of the study of nationalism and internationalism suggest that this point is worth highlighting.

A second spring for Soviet nations

With the adoption of a new Communist Party programme in 1961, the ‘drawing together’ (sblizhenie) and, ultimately, ‘fusion’ (sliyanie) of Soviet nationalities were endorsed as policy. However, both processes were seen as long-term goals. For the time being, another policy was meant to prevail, namely the ‘flourishing’ (rastsvet) of nations. Under Brezhnev (1964–1982), the shared culture of the developing ‘Soviet people’ (sovetskii narod) was to be expressed in different forms and languages. This was no tactical concession to nationalist elites but very much in line with post-Stalinist nationality theory.Footnote14 Ultimately, it was believed that each nation had ‘progressive’ and ‘reactionary’ traditions; and while the latter would fade out under socialism, the progressive ones would be cultivated and, in an ever more urban context, merge with new socialist traditions (Nadzhimov Citation1974, p. 127). The long list of nations living in the Soviet Union shrank from 175 to 100 between the censuses of 1926 and 1939, but then increased again after the death of Stalin. This fluctuation was due to a number of factors: most importantly, the authorities first argued that certain nationalities had already ‘merged’, or they chose to deprive groups that had fallen out of favour of their nationality status. Under the new emphasis on the ‘flourishing’ of nations, however, they once again ‘awarded’ nationality status to more communities, with 123 different national groups accepted as options in the census of 1970.Footnote15

By introducing ethno-territorial federalism and personal nationality, the 1920s and early 1930s had already seen the dual institutionalisation of nationhood and nationality: while the former had created a system of nationally defined territories with privileged ‘titular’ nationalities (such as Armenians in the Armenian SSR) and different degrees of autonomy, the introduction of nationality in official documentation in 1932 meant that every Soviet citizen was assigned a national group (Brubaker Citation1994, pp. 52–3). Simultaneously, in affirmative action known as korenizatsiya (‘indigenisation’), titular nationalities were systematically promoted to positions of authority in ‘their’ republics (Martin Citation2001). Though never formally abandoned, these principles played less of a role under Stalin. In the early 1960s, they came back with a vengeance. As the Soviet leadership tried to free itself from the legacies of Stalinism, it took nationality policy to a level never reached in the 1920s.

First, the folklorisation of culture now reached the masses, with music and film festivals, exhibitions and competitions ‘staging’ nationality through costume, song and cultural practice for everyone to see and experience. Young people—and youth organisations such as the Pioneers and Komsomol—were at the forefront of such activities. On Soviet holidays, including May Day and the anniversary of the October Revolution, large numbers of youth activists would march in clothes and headwear reflecting national ‘traditions’.Footnote16 Republican film industries developing national themes emerged from Georgia to Kirghizia (Cummings Citation2009; Radunović Citation2014). Distinctive architectural styles merging Soviet, national and international modernist elements were also promoted: in public buildings, residential blocks and metro systems, and in the use of water and green spaces in new urban design.Footnote17 Travelling folklore ensembles, lavishly funded jubilees, statues and memorials, publications and readings devoted to national poets became a key part of life (Baldauf Citation2007). A striking example of the Soviet promotion of nationality was given in the Osh Oblast’ Encyclopaedia:

Before the October Revolution, the art of the manaschi, reciters of the monumental Kirghiz epic Manas, was not widely practised in the southern regions [of the Kirghiz SSR], and some Kirghiz mountain tribes were not even familiar with the Manas epic. Under Soviet rule the art of the manaschi has been spread everywhere. Party organisations attach great importance to the continuity of the traditions of the manaschi, and the mentoring of youth by older reciters is encouraged. (Iarkova Citation1987, p. 114)

The history of the Manas and other folk epics was admittedly complicated as they had been temporarily forbidden under Stalin (Myer Citation2002, pp. 87–9, 111). From the late 1950s, however, republican party elites, artists and intellectuals were able to promote these epic poems as the essence of national values. That local party organisations even promoted the recitation of Manas in villages was very much in line with Brezhnev-era nationality policy.

By the mid-1950s, national academies of science had been established in nearly all union republics. They greatly diversified and intensified their activities in the post-Stalin years. Along with the exhibitions and programmes offered by ethnographic museums and other cultural institutions, they helped to showcase national culture to academic and non-academic audiences. In collaboration with the republican communist parties, local linguists, historians and artists, many of them party members, actively engaged in reviving national pasts and in glorifying the national present (Smith Citation2013, p. 229). National histories were taught in Soviet schools from 1960, and the academic study of these histories was conducted in accordance with state plans.Footnote18 In some cases, open disagreements between, for example, Armenian and Azerbaijani scholars over their national territories, were aired in Soviet publications.Footnote19 In long articles published in the local party press, Kazakh academics called for further efforts to teach the Arabic script and ‘Eastern languages’ (şığıs tilderi) more generally in the republic; such efforts would enhance people’s understanding of Kazakh history and culture.Footnote20 At the same time, such academics framed the previous introduction of Arabic in (some) schools and universities as the ‘direct result of party concern’ (partïyalıq qamqorlıqtıń tikeleý nätïjesi) (Berdibaev Citation1979, p. 4).

Still, there were differences in the ways in which the republics handled and showcased their national histories. In Ukraine, even under the party leadership of Petro Shelest (1963–1972), who defended Ukrainian autonomy, linguistic and cultural rights, museums were reluctant to engage with Ukrainian national history. When in November 1968 the Ukrainian KGB intercepted leaflets distributed by a group calling itself the tvorcha molod m. Dnipropetrov’ska (creative youth of Dnipropetrovsk city), they found the group bitterly complaining about the tsinichne ukrainofobstvo (cynical Ukrainophobia) of the Dnipropetrovsk history museum and the city authorities.Footnote21 Due to the museum’s exclusive focus on Russian achievements, the group had become cynical themselves:

The long-term plans for the monumental popularisation [of history] in the city of Dnipropetrovsk do not include the names of outstanding Ukrainian figures of the past … such as Mikola Skripnik, one of the most prominent Bolshevik revolutionaries, organiser of the revolutionary struggle in Ekaterinoslav and associate of V. I. Lenin. But our city will be enriched [zbagatit’sya] with yet another monument to Gorky, a monument to Matrosov, monuments to Tchaikovsky and Glinka and others.Footnote22

In Armenia, by contrast, numerous cultural institutions were engaged in the popularisation of Armenian national culture. In 1981, the director of the State Museum of Ethnography, Lavrentii Barsegian, sent a letter to the first secretary of the Armenian Communist Party in which he began by reporting the ‘rapturous growth [burnyi rost] of ethnographical and folkloristic studies’ in the country before lamenting the lack of coordination between all the research institutes, academic departments and museums working on Armenian national history.Footnote23 The ‘creative youth’ of Yerevan enjoyed far better conditions than their counterparts in Dnipropetrovsk and Kyiv.

Discrepancies were also apparent in more practical policy matters, such as language and the preferential treatment of titular nationalities. On the whole, the post-Stalin neo-korenizatsiya took the promotion of local staff in state and party organisations to new heights. Statistics on staffing between 1955 and 1972 reveal that locals became overrepresented in republican elites in 12 out of 14 non-Russian republics (Hodnett & Ogareff Citation1973). The percentage of non-Russians also increased amongst academics between 1960 and 1973, though in some cases these increases were higher than in others: in Ukraine, for example, they rose slightly from 48.3% to 50.6%, whereas in Azerbaijan and all of Central Asia, the growth was significant; for example, from 64.6% to 72.9% in Azerbaijan and from 34.4% to 46.9% in Uzbekistan.Footnote24 In Armenia, the increase was from 93.6% to 94.8%. These figures also show that the republics started from very different levels when it came to the recruitment of locals.

Perhaps the most striking increase in ‘indigenisation’ took place within the Communist Party. In Lithuania, ethnic Lithuanians made up 80% of local party cadres by the 1970s, compared with just 40% after Stalin’s death (Rolf Citation2014, p. 213). In Ukraine, ethnic Ukrainians made up 84% of provincial party secretaries in the mid-1960s and an astonishing 96% in 1980 (Beissinger Citation1988, p. 75). With few exceptions, the indigenisation data for other republics show similar developments: a strong representation, even overrepresentation, of titular nationalities in most key institutions. Yet the differences between republics remained. While Armenian, Ukrainian and Lithuanian representation in their respective KGB leaderships was very high for most of the Brezhnev period, it was less than 25% in Azerbaijan, Belorussia and most of Central Asia (Knight Citation1988, pp. 167–68, 339–41).

Another key factor affecting national representation was age. shows intriguing differences between Komsomol and party membership amongst Soviet nationalities in 1982. While all nationalities except for the Russians, Belorussians and Georgians were underrepresented in the Communist Party rank and file, non-Russians were overrepresented in the Komsomol. This was particularly pronounced in the Caucasus and Central Asia; Baltic youth, Ukrainians and Russians in particular were represented less strongly than their share of the population would have suggested.

TABLE 1 Membership in the Komsomol and Communist Party of the Soviet Union by Nationality

Put bluntly, by the end of the Brezhnev period, the Komsomol was a predominantly non-Russian organisation. Youth activism was one sphere in which affirmative action paid off. And, given the mass involvement of youth organisations in both nation-building and internationalist activities, the effects of nationalisation and internationalisation were, in all likelihood, also particularly strong amongst the young.

Before exploring the link between nationality and international ties in more detail, I would like to offer some brief caveats: first, the republicanisation of nationality policy was pronounced in language matters. Ukraine, Belorussia, Moldavia and, to a degree, the Kazakh SSR were hit the hardest by constraints on their national languages (Lipset Citation1967; Fowkes Citation2002, pp. 72–4). Thus, while the notion of ‘Russification’ has become an overused cliché for much of Soviet rule, it is certainly appropriate for some contexts. Second, the promotion of titular nationalities could not prevent interethnic friction and violence, despite the Brezhnev-era insistence on harmony (for examples, see Kozlov Citation2002). Third, the hierarchies built into the Soviet Union’s ethno-territorial federalism—with the 15 union republics constituting the top tier and the autonomous regions and districts underneath—produced many inequalities. While the promotion of national cultures and cadres concentrated on the top tier, smaller national communities’ concerns were often neglected. Finally, the promotion of nation and nationality after 1961 was paralleled by a virulent campaign against ‘bourgeois nationalism’, that is, activism in the name of the nation that the authorities branded ‘anti-Soviet’. The difference between a legitimate nation-builder and a dangerous nationalist was often in the eye of the beholder.

From the national to the international

Internationalism in the Soviet sense included not only interaction with states beyond the Soviet border but also invocations of ‘peoples’ friendship’ (druzhba narodov) within the Soviet Union itself. Both were inconceivable without conscious and persistent nation-building efforts. The supranational did not replace the national in Soviet thinking and practice but was informed by it in myriad ways. The interplay of the national and the international was explained by an Uzbek delegate at a 1972 conference on internationalism in Tashkent:

New popular traditions have both a national and an international character. … Socialist traditions have become the national achievement of the peoples [narodov] of our country, an inherent part of its general culture—socialist in content and national in form. At the same time, they are international because they belong to every nation of the Soviet Union. (Nadzhimov Citation1974, p. 128)

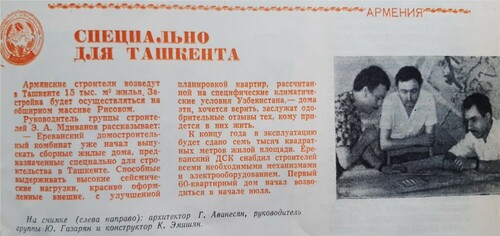

Manifestations of friendship between republics were presented as examples of the merger of ‘progressive’ national and new socialist traditions. For this delegate, the ‘progressive’ Uzbek tradition of mutual help (hashar) had evolved under socialism, ensuring a swift response to the devastating earthquakes in 1966, when ‘the construction of new Tashkent took on the character of an all-union people’s hashar: builders from brother republics created more than 1.2 million m² of living space’ (Nadzhimov Citation1974, pp. 127–28). This is not just one individual’s terminology. Right after the earthquakes, Uzbek writer Asqad Muxtor invoked the notion of the hashar to characterise the reconstruction efforts, which then spread amongst architects and policymakers.Footnote25 Experts, relief funds and building materials soon poured into Tashkent from all over the USSR (Sheehy Citation1966). The authorities, for their part, sought to reassure the population by endlessly repeating the internationalist message that the whole country was coming to their aid, and the notion of a city rebuilt through brotherhood would feature in the Soviet press for decades.Footnote26 The head of the Union of Architects of Uzbekistan provided more exact figures, claiming that Russia helped to reconstruct 660,000 m² of living space while Ukraine built 160,000 m², Azerbaijan 35,000 m², Kazakhstan 28,000 m² and Armenia 15,000 m² (Tursunov Citation1974, p. 214). Specialist journals such as Building and Architecture of Uzbekistan (Stroitel’stvo i arkhitektura Uzbekistana) offered information on the assistance provided by individual republics (see ), enshrining internationalism further in the collective memory.

FIGURE 2. ‘Armenia—Specially for Tashkent’. The Armenian Reconstruction Effort Captured

Source: ‘Tashkent stroit vsya strana’, Stroitel’stvo i arkhitektura Uzbekistana, 7, no. 8, August 1966, p. 5.

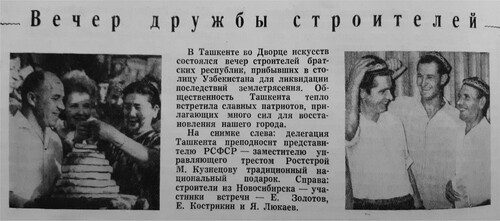

Nationality was also part of everyday encounters, including social events for builders and engineers at which the Uzbek hosts presented their national cuisine and wore national costume (see ). It is telling that just hours after the first earthquake and despite severe after-shocks, Tashkent went ahead with the final concert of the ten-day Festival of Belorussian Arts. The Belorussian delegation briefly mentioned the earthquake before explaining, more importantly, how the festival had seen hundreds of events featuring Belorussian and Uzbek writers, musicians, painters and film-makers.Footnote27 The two sides then symbolically exchanged musical instruments: ‘May the Belorussian tsimbaly and the Uzbek chang sound together forever!’Footnote28 Not even natural disasters could stop efforts to showcase Soviet nations.

FIGURE 3. ‘Builders’ Friendship Evening’

Source: ‘Tashkent stroit vsya strana’, Stroitel’stvo i arkhitektura Uzbekistana, 7, no. 8, August 1966, p. 12.

The reinvention of disaster relief as hashar is one example of how Soviet rhetoric and practice simultaneously strengthened national and internationalist sentiments. There were others. Soviet music historian Tamara Vyzgo saw internationalism in the musical practice of Soviet Uzbekistan: while the topics of songs showed much convergence across the Soviet Union, the language, instruments and musical arrangements were shaped by national traditions (Vyzgo Citation1974, pp. 250–51). Examples included Suleymon Iudakov’s Partiya haqida yoshlar qushigi (Youth Song about the Party), Mutal Burhonov’s Partiya jonajon (Beloved Party) and Po’lat Mo’min’s Jonon qizlar (Sweet Girls), the latter idolising female cotton-pickers. It was not just the mixing of styles and musical traditions that accounted for these works’ internationalist meaning, however; they were performed by young national ensembles for non-local audiences across the USSR and beyond. In this sense, it was the international encounter that gave meaning to national practice.

Internationalism understood as friendship amongst Soviet nations was also carried into rural locations. At the Akkol sovkhoz (state farm) in the predominantly Kazakh-speaking Balkhash region in southeastern Kazakhstan, the Komsomol committee was enthusiastic about Äzilxan Nurşaýıqov’s novel Aqïqat pen ańız (Truth and Legend, 1973), which would receive the Kazakh SSR’s Abai State Literature Award in 1980.Footnote29 The young activists approached the sovkhoz and local library councils and persuaded them to organise a ‘readers’ conference’ (oqırmandar konferencïyası), accompanied by a ‘book show’ (kitap kórmesi), in August 1979. The event and the novel itself, eventually published in Russian in 1980, highlight the ways in which the nation, nationalism and internationalism reinforced each other: Nurshaıyqov’s Kazakh-language work was a dialogical novel about the Soviet–Kazakh war veteran and national hero Bawırjan Momışulı, whose legendary feats were a source of immense national pride for Kazakh readers. The author himself was not only an acclaimed literary figure but also a prolific journalist and regular contributor to the Kazakh Communist Party press organ, Socïalïstik Qazaqstan, amongst other newspapers.Footnote30 The book and its author were both profoundly Soviet and profoundly Kazakh and therefore almost guaranteed to appeal to Komsomol youth on state farms.

Internationalism also concerned the outside world. One reason why the Tashkent authorities wanted to restore a sense of normality as quickly as possible after the 1966 earthquakes was that the city was reluctant to give up its role as a model of Soviet ‘modernity’ and showcase for guests from Asia and Africa. Earlier that year, it had already welcomed delegations from Latin America, Nepal and, most importantly, India and Pakistan.Footnote31 The latter arrived to hold negotiations in January 1966 ‘in the name of peace and the friendship of peoples’, suggesting that druzhba narodov was meant to guide the relations of nations both inside and outside the Soviet Union.Footnote32 The Uzbek hosts played a proactive role during the negotiations, held inside the building of the Supreme Soviet of the Uzbek SSR: they gave daily press conferences to hundreds of international journalists, using these events to stress the achievements of Soviet Uzbekistan (more than those of the Soviet Union as a whole) and highlight how close the Uzbeks were to their South Asian guests in a geographical and cultural sense.Footnote33 This quality clearly set them apart from Moscow. The international limelight thus accommodated and stirred national sentiment. Two months later, Pravda vostoka—the official organ of the Communist Party of the Uzbek SSR—published an overview of Pakistani and Indian press reactions to the summit, proudly focusing on how Uzbekistan had been presented as a ‘thriving republic’ and their capital as ‘one of the most modern cities of Asia’.Footnote34 Tashkent was the place to be.Footnote35

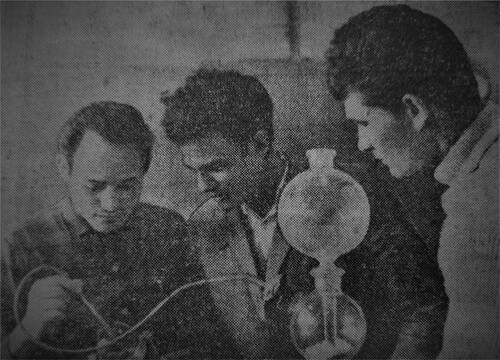

By the early 1970s, Uzbekistan had established links with 107 countries (Shukurova Citation1974, p. 225). This was facilitated by the fact that, since the mid-1940s, the union republics had been allowed to establish their own foreign ministries, which were encouraged to develop cultural and economic ties abroad. International symposia and seminars flourished, and by 1972, 620 non-Soviet university students were enrolled in Uzbekistan (Shukurova Citation1974, p. 226; see also ). This number was considerable, and it also had to do with the idea that staying in Tashkent would ease the entry of Asian and African students into Soviet society: once accepted at the University of People’s Friendship in Moscow, they would, for example, be required to complete a preparatory year in Tashkent (Rupprecht Citation2010, p. 104).

FIGURE 4. Cuban, Somali and Russian First-year Students at the Tashkent Institute for Irrigation and Mechanisation Engineering

Source: Pravda vostoka, 11 January 1966, p. 4.

Most foreign students in the USSR—35,000 by 1972 and over 100,000 by the 1980s—were from Asia, the Arab countries, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (Katsakioris Citation2011, p. 411). These ties thus became a notable factor in Soviet society. Much has been written about these international guests’ feelings and impressions (Hessler Citation2006; Rupprecht Citation2015, pp. 191–229; Hornsby Citation2016; Applebaum Citation2019), whereas the importance of these ties for Soviet youth has received less attention. The Komsomol was, in practice, the everyday gatekeeper and supervisor of this internationalist experience: its ‘Sputnik’ travel bureaus screened and selected those who travelled abroad, and it was the university, regional, city and district Komsomol branches that looked after (and monitored) foreign youth—be they students, tourists or participants in ISSOs and festivals.

Soviet Armenia hosted only a modest number of non-Soviet graduates: 1,676 for the entire period from 1961 to 1987.Footnote36 International student exchange, however, was still an important factor in this republic, not least because it took on a distinctive national flavour. Student construction projects were one small element in this, as we saw at the beginning; international youth camps were another. In the mid-1970s, the Lastochka (‘Swallow’) youth camp had an annual intake of 15–20 youth groups, all staying for roughly three weeks at a time.Footnote37 These groups, which tended to include youth from capitalist, socialist and developing states, would follow clearly defined work schedules, with entire days set aside for national themes such as the ‘Fine Arts of Soviet Armenia’, ‘Historical-Architectural Monuments of Armenia’, ‘Armenia—An Open-air Museum’ and ‘Armenian Theatre Is 2,000 Years Old’.Footnote38 In this sense, an international youth camp (Russian: Mezhdunarodnyi Molodezhnyi Lager’—MML) fulfilled functions similar to the ISSO at Lake Sevan, highlighting national achievements for international audiences.

Student exchange in Soviet Armenia bolstered national identity in other ways. A striking 1,431 of the aforementioned non-Soviet graduates were ethnic Armenians, and 70.4% of them came from Lebanon, Syria and Jordan.Footnote39 This was possible because from 1962, as part of a new ‘repatriation' campaign aimed at attracting ethnic Armenians outside the Soviet Union, the Armenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs recruited foreign (zarubezhnye) Armenians for study in Yerevan primarily from these countries, along with smaller contingents of ethnic Armenians from other states, including Iran, Iraq, the United States and France (while requiring applicants to submit a recommendation by a ‘progressive Armenian organisation’).Footnote40 By the late 1970s, many Soviet embassies routinely received so many applications that the original number of 70 admissions of ‘foreign’ Armenians per year had to be raised to 120.Footnote41

International student interactions were thus rather diverse and included truly intercontinental ties, as seen in Tashkent, and more regionally contained movement by Soviet nationalities across the southern border. Such movement, moreover, was not limited to the young generation. Until the late 1970s, conferences and festivals on Armenian culture attracted many Armenians from Iran while Yerevan encouraged the Armenian community in Tehran to organise cultural film events (and supplied them with films, books, magazines and other cultural goods). Iranian Armenians even came to Soviet Armenia as pilgrims (palomniki).Footnote42 The Armenian government saw the value of all these exchanges partly in the promotion of Soviet ideas abroad, yet these international connections also helped to forge national identities across borders. Either way, from an Armenian perspective, the southern border certainly seemed porous.

However, there were important changes over time. Odessa offers an example of a Soviet city on the southern border that sought to develop its maritime, international ties on all fronts. In post-Stalin society, this ambition fell on fertile ground. In 1959, the chairman of the State Committee on Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries reminded city councils across the Soviet Union that international connections between cities were ‘useful forms of cooperation’ but still lacked the ‘necessary coordination, orderliness, and strength of purpose’.Footnote43 In its answer, the Odessa council sent detailed reports of a 12-day trip to Alexandria (Egypt) in July 1960 and a seven-day trip to Oulu (Finland) in September.Footnote44 With all three cities being major ports, they had much in common. Notably, both trips were return visits, following visits by Egyptian and Finnish city delegations to Odessa the previous year. In November, Odessa received a delegation from the port of Durrës, Albania.Footnote45 While the trip to Egypt had attracted much local attention (records in Odessa contain translations of 13 Egyptian newspaper articles), this time it was Ukrainian newspapers and radio that reported incessantly on the Albanian delegation.

These early exchanges involved a handful of carefully selected people. Soon, however, crossing borders became popular with the masses (Gorsuch & Koenker Citation2006; Wojnowski Citation2018; Tondera Citation2019). In November 1968, the Ukrainian KGB reported that in 1967–1968, more than 49,000 Soviet citizens had travelled from Ukraine alone to other socialist, capitalist or developing countries for work and study visits, tourism and sports events.Footnote46 For Kazakhstan, where KGB data are not readily available, the Komsomol’s ‘Sputnik’ bureau in Alma-Ata counted roughly 4,500 tourists from the Kazakh SSR who passed through formal channels in 1977, with the vast majority (4,209) visiting socialist countries.Footnote47 The Kazakh figures, however, do not include professional, study, sports and cultural exchange trips.

Considerable numbers of young people were rewarded with foreign travel themselves: in their respective republics, local cadres were selected for Soviet delegations abroad or for tourist visits. ‘Sputnik’ records offer evidence of such preferential treatment. In Armenia, for example, 38 out of 40 young tourists sent to Cuba in January 1979 were ethnic Armenians; four months later, all 17 tourists sent to Mexico were Armenians; in September, a group of 37 youths (exclusively Armenian) was cleared to spend 15 days in Colombia and Ecuador.Footnote48 This predominance runs through all other tourist groups sent from Soviet Armenia to Latin America and Europe in the late 1970s. While the archive holds no accounts of the trips themselves, it is certainly conceivable, even likely, that travelling in largely single-nationality groups helped to make Soviet nations seem natural and functional.

Was this a broader phenomenon? Comparable data are scarce. A report on international travel from Odessa oblast’ in 1959–1963 shows an increase in the percentage of Ukrainians travelling, from about 30% to 40%, largely because of a decline in Jewish travel, which dropped from around 30% to 11% over the same period (mostly because of Jewish out-migration).Footnote49 Since the 1959 Soviet census put ethnic Ukrainians at 55.5% of the population of Odessa oblast’, the titular nationality seems underrepresented at first sight. That said, the bulk of this Ukrainian population lived in rural areas, whereas the city of Odessa, the main source of international travellers, had a sizeable Russian population. Against this background, the increase in Ukrainian travel can also be read as an attempt at ‘indigenisation’. Indeed, records from different parts of the USSR suggest difficulties in recruiting rural travellers. In 1980, Alma-Ata’s ‘Sputnik’ Bureau informed the local Komsomol that significant numbers of places for travel abroad had not been filled the previous year due to a shortage of rural applicants.Footnote50 That said, these examples also indicate that the conditions for, and results of, affirmative action differed across the republics.

Finally, friendship clubs and societies played a crucial role in developing internationalism. The visits between Odessa and Oulu, for example, were facilitated by the USSR–Finland Society.Footnote51 The Armenian section of the Soviet–Indian Friendship Society assisted in developing exchange between Armenia and the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, which had established friendly relations in 1965.Footnote52 To reflect the ‘growing mutual interest between the people of Armenia and India (indiiskogo i armyanskogo narodov)’, Armenian-language authors were translated into Telugu, Kannada and Bengali, while numerous Indian authors were made available in Armenian.Footnote53 The festivities surrounding a visit to Armenia by Indian officials in 1982, in turn, largely consisted of Armenian and Indian music and poetry readings, thus deliberately catering to national tastes.Footnote54

Arguably, the impact of international friendship clubs and societies amongst state representatives was not nearly as important as the role these connections played for ordinary Soviet citizens, especially youth. The opening speech at a Komsomol seminar on internationalist education in Alma-Ata in 1982 (see ) mentioned the existence of over 500 international friendship clubs (klub internatsional’noi druzhby—KID) across Alma-Ata Region alone; and since the local Komsomol received regular reports from clubs in hundreds of schools, universities, factories and even farms, this number may not be an exaggeration.Footnote55 A speaker from Alma-Ata oblast’ explained that these clubs’ appeal lay not only in the contact they established with young people in over 30 countries, but also in their ‘circles of artistic creativity’, including musical ensembles and other creative groups, down to the state farm level.Footnote56 In other words, they offered the kinds of leisure activities that galvanised young people as well as windows to the outside world.

FIGURE 5. Participants at the Internationalist Seminar, Alma-Ata 1982

Source: APRK, f. 9, op. 32, d. 23 (Photographs of the seminar on the internationalist education of youth).

Like the Armenian–Indian friendship society, such friendship clubs also promoted national content. The international club at School No. 11 in Aktyubinsk, northwestern Kazakhstan, for example, established a partnership and correspondence with a school in the GDR, which led the East German school to name itself after the famous Soviet–Kazakh war veteran Aliya Moldagulova. Reporting back to Alma-Ata, the secretary of the Aktyubinsk Komsomol, Kul’sharov, proudly described her as a ‘heroine of our Kazakh nation’. Then he added: ‘The kids at School No. 11 are now helping their friends to find material about Aliya’s life’.Footnote57 It was the international exchange that inspired these young people to research their past and come up with material simultaneously nurturing their Soviet and Kazakh identities.

Given the ubiquitous national forms that international activities promoted, it is perhaps surprising that KIDs and solidarity campaigns for Third World countries became the target of nationalists.

In 1968, the Ukrainian KGB reported the formation of an illegal youth organisation calling itself slavyanskii volonter (Slavic Volunteer), consisting of 14 pupils at a local school.Footnote58 The group’s agenda was radical, with their written ‘programme’ calling for nothing less than the liquidation of the Communist Party and the destruction of the Soviet system. The group claimed to be a ‘military-political organisation’, used military terminology, and even stated its intention to launch a campaign of bombing and arson: driven by racist beliefs, it claimed that the Soviet state should renounce internationalism and the equality of nationalities and instead follow pan-Slavic ideals. Assistance to other countries should stop, and non-Slavic peoples should be forced to leave the USSR. Given the radical nature of these positions, it is striking that the KGB monitored the group, formed in 1964, for almost five years before acting. At the time of the group’s formation, its key members were only 15–16 years of age; however, their demands seemed to intensify over time. In 1968, when a harsh response might have been expected, the KGB file merely states that during the interrogations, the youths ‘renounced their beliefs with all sincerity’, pledging never to engage in such activities again. It is also mentioned that most of their parents were Communist Party members and that the young people’s actions were seen as ‘immature’ rather than ‘hostile’. They were therefore required to perform ‘socially beneficial labour’ and not expelled from their institutions.

Perhaps it was the long-standing Soviet belief that young people needed firm guidance that led to such a lenient response; perhaps it was the parents or other relatives who put in a good word or had to be handled with caution; or maybe harsher treatment during the interrogations is simply not mentioned in the file. Perhaps it was a mixture of the above, or that the nationalism and racism proposed by ‘Slavic volunteer’ were deemed less problematic than nationalist separatism.

The situation was different when youth activists pursued more distinctly ‘Ukrainian’, ‘Armenian’ or other nationalist agendas aimed at changing borders. This is where nation-building stopped and ‘bourgeois nationalism’ started. For example, several Armenian nationalist youth groups that emerged at roughly the same time expressed their solidarity with the Communist Party but formulated claims to Azerbaijani, Turkish and Georgian territory.Footnote59 In response, members were detained and expelled from the party, their institutes or jobs. Their activities were branded ‘anti-Soviet’ even though they saw themselves as devoted communists. While academic nationalism was tolerated to a degree, uncontrolled nationalism by youth groups was not. That said, anti-internationalist pan-Slavism may have been less dangerous in Soviet eyes than activism aimed at redrawing maps. That the authorities yielded to mass demonstrations in Yerevan by erecting the genocide memorial in 1967 did not mean that independent nationalist organisations and their public agitation were considered acceptable.

Conclusion

In the end, who was a nationalist rather than a Soviet patriot and internationalist, and who was not, was a labelling issue, and the answer changed over time and differed between actors, regions and republics. By the time of glasnost’ and perestroika, the answer no longer mattered. Decades of nation-building, reinforced by internationalist rhetoric and activities, had elevated national categories and thought patterns to such heights that the distinction between proud Soviet nations and dangerous anti-Soviet nationalism had become unrecognisably blurred. Once economic problems came to dominate public discourse in the 1980s, it was only natural that the solution would be sought and couched in national terms.

Internationalism had helped to prepare the ground. As nationalism’s seemingly innocent cousin, it had enshrined national thinking in everyday politics and, more importantly perhaps, in everyday work and leisure. Young people were galvanised by both projects in considerable numbers, especially in the Soviet south: Komsomol activists were running and monitoring most exchanges with foreign students and visitors, and it was mostly youth activists and ordinary party members who went abroad themselves. These activists also organised clubs at schools and universities devoted to the ‘friendship of peoples’ inside and outside the Soviet Union. And in so doing, they actively promoted nation-building, as participants in ‘national’ artistic performances and parades and as hosts displaying their ‘Uzbekness’, ‘Armenianness’ and so on to guests from other republics and abroad. Without nations, the druzhba narodov would have had no building blocks and little purpose; and without internationalism, Soviet nations would have lost not only much of their mobilising appeal but also their audiences.

Even in discussions of war experiences and party achievements, and in the organisation of disaster relief, the language and practice of internationalism helped to build Soviet nations. The Soviet Union’s simultaneous promotion of national cultures and the opening up to the outside world contributed to a vibrant, dynamic society for most of the 1960s and 1970s but, inadvertently, these developments played no small role in preparing the system’s demise.

Strikingly, internationalists and nation-builders were often the same people. While some were singled out as dangerous ‘bourgeois nationalists’ where matters of territory and (in some cases) language were concerned, many young people were simultaneously avid Soviet activists and nationalists, in the social constructivist sense of nations requiring nationalists to build them. This also means that there are no easy answers to the question of the overall role of youth: some supported and some challenged the system, wittingly or unwittingly, and many did both. The effects of international connections were equally varied: while it is certainly conceivable that contact with the outside world in itself, let alone trips abroad, nurtured critical attitudes amongst Soviet youth, such contact, especially with Asian and African countries, was also the source of immense pride and may have helped to sustain the union for years.

Either way, the nexus of nations, nationalism and internationalism was not uniform across the USSR. In Ukraine, Belorussia and elsewhere, ethnic nation-building gathered pace while calls for strengthening the national language were routinely branded as ‘anti-Soviet, bourgeois nationalism’.Footnote60 While Soviet nationalities were all promoted to different degrees, they were clearly not equal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefan B. Kirmse

Stefan B. Kirmse, Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin, Germany. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 National Archive of Armenia (Hayastani azgayin arkhiv, hereafter NAA), f. 488 (Central Committee of the Communist Youth League of Armenia), op. 45, d. 28 (‘Reports by International Student Brigades’, 1975).

2 NAA, f. 488, op. 45, d. 28, ll. 3, 19–21.

3 Over time, the term came to be used interchangeably with ‘Armenia’.

4 NAA, f. 488, op. 45, d. 28, ll. 5–6.

5 NAA, f. 488, op. 45, d. 28, ll. 8, 10, 13–7.

6 NAA, f. 488, op. 45, d. 28, l. 25.

7 Perhaps the presence of international guests even pushed Armenian activists to get tickets in the first place, which were reportedly hard to obtain: ‘Vperedi—final’, Kommunist. Organ Tsentral’nogo Komiteta KP Armenii, no. 167, 17 July 1975, p. 4.

8 The eligible age bracket was 14–28 years, but many functionaries were in their mid-30s.

9 On the dynamism of the Brezhnev period, see Belge and Deuerlein (Citation2014), Fainberg and Kalinovsky (Citation2016).

10 See also Shahrani (Citation1994, pp. 144, 147), Menon (Citation2003, p. 188).

11 Most general works on Soviet history advance variants of this argument. More specifically, see Bremmer and Taras (Citation1993), Kozlov (Citation2002), Zisserman-Brodsky (Citation2003).

12 See also Martin (Citation2001), Hirsch (Citation2005).

13 Suny describes a telling episode in this article: his mere suggestion that Armenian nationality and statehood may be modern constructs led to protests and public outrage in Yerevan in 1997. If anything, the gap between Western academia and post-Soviet discourse has widened since then, with most things Soviet now being denounced as Russian colonial and imperial impositions across former Soviet republics, and entire museums dedicated to Soviet ‘occupation’.

14 On its complex trajectory, see Shanin (Citation1989), Bromley and Kozlov (Citation1989).

15 See the All-Union Population Census of 1970: ‘Vsesoyuznyi perepis’ naseleniya 1970 goda. Natsional'nyi sostav naseleniya po respublikam SSSR’, Demoscope Weekly, available at: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/sng_nac_70.php, accessed 2 August 2022.

16 Examples from Tashkent in the 1960s and 1970s were captured by the Soviet photo correspondent Semyon Beznosov (1917–1978), to whose work several social media pages are now devoted. See, for example: https://www.facebook.com/semyonbeznosov/photos/pcb.3812992215392272/3812988295392664, https://www.facebook.com/semyonbeznosov/photos/pcb.3812992215392272/3812989132059247, https://www.facebook.com/tashkentretrospective/photos/pcb.1522710567916218/1522708507916424, accessed 16 August 2021.

17 For the debate on twentieth-century mahallas (traditional Uzbek neighbourhoods) merging national, Soviet and international patterns, see ‘Makhallya XX veka’, Pravda vostoka, 3 February 1967, p. 1. On mixed architectural styles, see also Ter Minassian (Citation2007), Chukhovich (Citation2014, pp. 263–94), Kirasirova (Citation2018, pp. 53–66).

18 See the correspondence between the director of the State Museum of Ethnography in Armenia and the Armenian Communist Party: NAA, f. 1 (Central Committee of the Armenian Communist Party), op. 68, d. 19, l. 3.

19 The Azerbaijani scholar Ziya Buniyatov (Citation1965) was heavily criticised, for example, by the Armenian intellectuals Asatur Mnatsakanian and Paruyr Sevak (Citation1967).

20 The ‘Eastern’ languages implied were Arabic, Persian and Turkish: see, for example, Berdibaev (Citation1979, p. 4).

21 State Archive Branch of the Security Service of Ukraine (Haluzevyy derzhavnyy arkhiv Sluzhby bezpeky Ukrayiny—HDA SBU), f. 16 (KGB secretariat), op. 1, spr. 981 (November–December 1968), ark. 203–19, esp. ark. 210.

22 HDA SBU, f. 16, op. 1, spr. 981, ark 218–19.

23 NAA, f. 1, op. 68, d. 19 (‘Letter from the Director of the State Museum of Ethnography of Armenia’), ll. 2–4.

24 See the tables in Bialer (Citation1980, p. 216).

25 ‘Tashkent stroit vsya strana’, Stroitel’stvo i arkhitektura Uzbekistana, 7, no. 8, August 1966, p. 2. By the late 1960s, Uzbek papers used the term hashar virtually interchangeably with the Russian term subbotnik referring to voluntary weekend work for the common good: for example, ‘Hashar fikul’turnikov’, Pravda vostoka, 13 April 1969, p. 4.

26 Just one of many examples: ‘Bratstvom rozhdennyi’, Pravda, 26 April 1976.

27 ‘Do novykh vstrech, Belarus!’, Pravda vostoka, 27 April 1966, pp. 1, 3.

28 ‘Do novykh vstrech, Belarus!’, Pravda vostoka, 27 April 1966, p. 3.

29 Archive of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Qazaqstan Respublïkası Presïdentiniń Arxïvi —APRK), f. 1177 (Balkhash raikom of the Kazakh Komsomol), op. 15, d. 8 (‘Minutes of Komsomol sessions’, 1979), l. 45.

30 For biographical details, see Nurshaıyqov’s official website, available at: http://nurshaihov.kz/kz/mirbayany.html, accessed 13 August 2021.

31 ‘Uzbekistan privetstvuiet poslantsev Latinskoi Ameriki’, Pravda vostoka, 23 April 1966, p. 4; ‘Gosti Uzbekistana—deyateli kul’tury Nepala’, Pravda vostoka, 28 January 1966, p. 1.

32 ‘Vo imya mira i druzhby narodov’, Pravda vostoka, 4 January 1966, p. 1.

33 ‘Na Tashkent smotrit ves’ mir’, Pravda vostoka, 8 January 1966, p. 1; ‘Uzbekistan prezhde i teper’, Pravda vostoka, 6 January 1966, p. 1.

34 ‘Tashkent—simvol mira’, Pravda vostoka, 18 March 1966, p. 3.

35 On Tashkent as an exchange hub, see also Rakowska-Harmstone (Citation1983, pp. 68–71), Kirasirova (Citation2011), Djagalov and Salazkina (Citation2016).

36 NAA, f. 733 (Ministry of Education), op. 14, d. 15 (‘Contingent of Foreign Students’, 1987), l. 6.

37 NAA, f. 488, op. 50, d. 74 (‘Work schedule for Information, Culture and Physical Education’, 1977).

38 NAA, f. 488, op. 50, d. 74, ll. 4–5.

39 Author's calculation based on NAA, f. 733, op. 14, d. 15, l. 6.

40 NAA, f. 326 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), op. 4, d. 85 (‘Information on the Admission of Foreign Armenians to Universities in the Armenian SSR’, 1979), l. 2. For a critical assessment of these ‘repatriations’, see Lehmann (Citation2012, pp. 265–66).

41 NAA, f. 326, op. 4, d. 85, l. 3.

42 NAA, f. 326, op. 4, d. 44 (‘Correspondence with the Soviet Embassy in Iran, 1977’), ll. 1–6 (conferences), ll. 7–8 (pilgrims); d. 33 (‘Correspondence with the Soviet Embassy in Iran, 1975’), ll. 4–5.

43 State Archive of Odessa District (Derzhavnyy arkhiv Odes’koyi oblasti/Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Odesskoi oblasti—GAOO), f. R-1234 (Executive Committee of Odessa City Council), op. 8, d. 183 (‘Directives’, 1960), l. 77.

44 GAOO, R-1234, op. 8, d. 183, ll. 78–123, 127–34.

45 GAOO, R-1234, op. 8, d. 183, ll. 124–26.

46 HDA SBU, f. 16, op. 1, spr. 981 (1968), ark. 101–3, esp. 101.

47 APRK, f. 812 (Central Committee of the Komsomol of Alma-Ata city), op. 44, d. 288 (‘BMMT Sputnik Reports’, 1977), l. 14.

48 NAA, f. 488, op. 49 (BMMT ‘Sputnik’), d. 15 (‘Decisions by Exit Commission’, 1979), ll. 9, 41, 111.

49 GAOO, f. R-1763 (Council of Trade Unions for Odessa Region), op. 9, d. 28 (‘Annual Report on International Tourism’, 1963), l. 2.

50 APRK, f. 9, op. 29, d. 43 (‘Information on the Work of the Regional Komsomol Organisations’, 1980), esp. l. 2.

51 GAOO, R-1234, op. 8, d. 183, l. 122.

52 NAA, f. 709 (Armenian Society of Friendship and Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries), op. 8, d. 83 (‘Programme and Reports about Soviet–Indian Friendship’, 1982), l. 9.

53 NAA, f. 709, op. 8, d. 83, l. 11.

54 NAA, f. 709, op. 8, d. 83, l. 3.

55 APRK, f. 9, op. 32, d. 22 (‘Materials for a Seminar on Internationalist Youth Education for Regional Komsomol Committee Secretaries’, 1982), l. 41.

56 APRK, f. 9, op. 32, d. 22, l. 76.

57 APRK, f. 812, op. 34, d. 370 (‘Information from the Aktyubinsk obkom on International Friendship Clubs’, 1970), l. 1.

58 HDA SBU, f. 16, op. 1, spr. 973 (1968), ark. 75–80.

59 ‘Report by Vladimir Semichastnyi to the Central Committee on Armenian Nationalists’, in Suny (Citation2014, pp. 452–55).

60 Examples of such accusations by the Ukrainian KGB can be found, for example, in: HDA SBU, f. 16, op. 1, spr. 947 (1964), ark. 35–42; and f. 16, spr. 1149 (1978), ark. 62–5 and 181–85.

References

- Alexeyeva, L. (1985) Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious and Human Rights (Middletown, CT, Wesleyan University Press).

- Allworth, E. (ed.) (1971) Soviet Nationality Problems (New York, NY, Columbia University Press).

- Applebaum, R. (2019) Empire of Friends: Soviet Power and Socialist Internationalism in Cold War Czechoslovakia (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Baberowski, J., Kindler, R. & Donth, S. (eds) (2021) Disziplinieren und Strafen. Dimensionen Politischer Repression in der DDR (Frankfurt, Campus).

- Babiracki, P. & Jersild, A. (eds) (2016) Socialist Internationalism in the Cold War: Exploring the Second World (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Baldauf, I. (2007) ‘Tradition, Revolution, Adaption: Die kulturelle Sowjetisierung Zentralasiens’, Osteuropa, 57, 8–9.

- Bazhan, O. (2016) Krym v Umovakh Suspil’no-Politychnykh Transformatsii (1940–2015) (Kyiv, Klio).

- Beissinger, M. (1988) ‘Ethnicity, the Personnel Weapon, and Neo-Imperial Integration: Ukrainian and RSFSR Provincial Party Officials Compared’, Studies in Comparative Communism, 21, 1.

- Bekirova, G. (2004) Krymskotatarskaya Problema v SSSR (1944–1991) (Simferopol, Ocaq).

- Belge, B. & Deuerlein, M. (eds) (2014) Goldenes Zeitalter der Stagnation? Perspektiven auf die Sowjetische Ordnung der Brežnev-Ära (Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck).

- Berdibaev, R. (1979) ‘Jazba muralar mäni’, Socïalïstik Qazaqstan, no. 142, 19 June.

- Bialer, S. (1980) ‘Soviet Stability and the National Problem’, in Bialer, S. (ed.) Stalin’s Successors: Leadership, Stability and Change in the Soviet Union (Cambridge, MA, Cambridge University Press).

- Blauvelt, T. & Smith, J. (2016) Georgia After Stalin. Nationalism and Soviet Power (London, Routledge).

- Boden, R. (2013) ‘Globalisierung sowjetisch: Der Kulturtransfer in die Dritte Welt’, in Aust, M. (ed.) Globalisierung imperial und sozialistisch: Russland und die Sowjetunion in der Globalgeschichte 1851–1991 (Frankfurt am Main, Campus Verlag).

- Bremmer, I. & Taras, R. (eds) (1993) Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Bromley, J. & Kozlov, V. (1989) ‘The Theory of Ethnos and Ethnic Processes in Soviet Social Sciences’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 31, 3.

- Brubaker, R. (1994) ‘Nationhood and the National Question in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Eurasia: An Institutionalist Account’, Theory and Society, 23, 1.

- Buniyatov, Z. M. (1965) Azerbaidzhan v VII–IX vv (Baku, Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk AzSSR).

- Calori, A., Hartmetz, A., Kocsev, B. & Zofka, J. (2019) ‘Alternative Globalisation? Spaces of Economic Interaction Between the “Socialist Camp” and the “Global South”’, in Calori, A., Hartmetz, A., Kocsev, B., Mark, J. & Zofka, J. (eds) Between East and South: Spaces of Interaction in the Globalizing Economy of the Cold War (Berlin, DeGruyter).

- Carrère d’Encausse, H. (1978) L’empire éclaté: La Révolte des Nations en URSS (Paris, Flammarion).

- Chernyshova, N. (2013) Soviet Consumer Culture in the Brezhnev Era (London, Routledge).

- Chukhovich, B. (2014) ‘Orientalist Modes of Modernism in Architecture: Colonial/Postcolonial/Soviet’, Études de lettres, 2–3.

- Cummings, S. N. (2009) ‘Soviet Rule, Nation and Film: The Kyrgyz “Wonder” Years’, Nations and Nationalism, 15, 4.

- Djagalov, R. & Salazkina, M. (2016) ‘Tashkent ‘68: A Cinematic Contact Zone’, Slavic Review, 75, 2.

- Fainberg, D. & Kalinovsky, A. (eds) (2016) Reconsidering Stagnation in the Brezhnev Era: Ideology and Exchange (London, Lexington Books).

- Fierman, W. & Olcott, M. (1988) ‘Youth Culture in Crisis’, Soviet Union/Union Soviètique, 15, 2–3.

- Fowkes, B. (2002) ‘The National Question in the Soviet Union Under Leonid Brezhnev: Policy and Response’, in Bacon, E. & Sandle, M. (eds) Brezhnev Reconsidered (London, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Gilburd, E. (2018) To See Paris and Die: The Soviet Lives of Western Culture (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

- Gleason, G. (2003) ‘The Centrality of Central Eurasia’, Central Eurasian Studies Review, 2, 1.

- Gorsuch, A. E. & Koenker, D. (eds) (2006) Turizm: The Russian and East European Tourist Under Capitalism and Socialism (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Hasanli, J. (2015) Khrushchev’s Thaw and National Identity in Soviet Azerbaijan, 1954–1959 (Lanham, MD, Lexington Books).

- Hessler, J. (2006) ‘Death of an African Student in Moscow: Race, Politics, and the Cold War’, Cahiers du monde russe, 47, 1–2.

- Hirsch, F. (2005) Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Hodnett, G. & Ogareff, V. (1973) Leaders of the Soviet Republics, 1955–1972: A Guide to Posts and Occupants (Canberra, Australian National University).

- Hornsby, R. (2016) ‘The Enemy Within? The Komsomol and Foreign Youth Inside the Post-Stalin Soviet Union, 1957–1985’, Past and Present, 232.

- Huttenbach, H. R. (ed.) (1990) Soviet Nationality Policies: Ruling Ethnic Groups in the USSR (London, Cassell).

- Iarkova, E. N. (1987) ‘Muzykal’naya kul’tura’, in Oruzbaeva, B. O. (ed.) Oshskaya Oblast’: Entsiklopedia (Frunze, Akademiya Nauk Kirgizskoi SSR).

- Kassof, A. (1965) The Soviet Youth Program (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

- Katsakioris, C. (2011) ‘Sowjetische Bildungsförderung für asiatische und afrikanische Länder’, in Greiner, B., Müller, T. B. & Weber, C. (eds) Macht und Geist im Kalten Krieg (Hamburg, Hamburger Edition HIS).

- Katsakioris, C. (2017) ‘Burden or Allies?: Third World Students and Internationalist Duty Through Soviet Eyes’, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 18, 3.

- Khalid, A. (2003) ‘A Secular Islam: Nation, State, and Religion in Uzbekistan’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 35, 4.

- Kirasirova, M. (2011) ‘“Sons of Muslims” in Moscow: Soviet Central Asian Mediators to the Foreign East, 1955–1962’, Ab imperio, 4.

- Kirasirova, M. (2018) ‘Building Anti-Colonial Utopia: The Politics of Space in Soviet Tashkent in the “Long 1960s”’, in Jian, C., Klimke, M., Kirasirova, M., Nolan, M., Young, M. & Waley-Cohen, J. (eds) The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties: Between Protest and Nation-Building (London, Routledge).

- Kirmse, S. B. (2018) ‘Der Blick nach Süden. Globalisierung im Sozialismus’, public lecture at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, 17 January, available at: https://www.academia.edu/49172855/Der_Blick_nach_S%C3%BCden_Globalisierung_im_Sozialismus, accessed 16 July 2022.

- Knight, A. W. (1988) The KGB: Police and Politics in the Soviet Union (London, Unwin Hyman).

- Kozlov, V. A. (2002) Mass Uprisings in the USSR: Protest and Rebellion in the Post-Stalin Years (Armonk, NY, ME Sharpe).

- Lehmann, M. (2012) Eine sowjetische Nation. Nationale Sozialismusinterpretationen in Armenien seit 1945 (Frankfurt, Campus).

- Lehmann, M. (2015) ‘Apricot Socialism: The National Past, the Soviet Project, and the Imagining of Community in Late Soviet Armenia’, Slavic Review, 74, 1.

- Lipset, H. (1967) ‘The Status of National Minority Languages in Soviet Education’, Soviet Studies, 19, 2.

- Mark, J. & Rupprecht, T. (2019) ‘The Socialist World in Global History: From Absentee to Victim to Co-Producer’, in Middell, M. (ed.) The Practice of Global History (London, Bloomsbury).

- Martin, T. D. (2001) The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939 (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Matusevich, M. (2008) ‘Journeys of Hope: African Diaspora and the Soviet Society’, African Diaspora, 1.

- Menon, R. (2003) ‘The New Great Game in Central Asia’, Survival, 45, 2.

- Mnatsakanian, A. & Sevak, P. (1967) ‘Po povodu knigi Z. Buniyatova “Azerbaidzhan v VII–IX vv.”’, Istoriko-filologicheskii zhurnal, 1.

- Myer, W. (2002) Islam and Colonialism: Western Perspectives on Soviet Asia (London, Routledge).

- Nadzhimov, G. N. (1974) ‘Rol’ narodnykh traditsii v internatsional’nom vospitanii trudyashchikhsya’, in Khairullaev, M. (ed.) Bratstvo Narodov i Internatsional’noe Vospitanie (Tashkent, Tashkentskii Gosudarstvennyi Universitet).

- Nahaylo, B. (1999) The Ukrainian Resurgence (London, C. Hurst).

- Nahaylo, B. & Swoboda, V. (1990) Soviet Disunion: A History of the Nationalities Problem in the USSR (New York, NY, Simon and Schuster).

- Olcott, M. (1990) ‘Youth and Nationality in the USSR’, Journal of Soviet Nationalities, 1, 1.

- Radunović, D. (2014) ‘Incommensurable Distance: Versions of National Identity in Georgian Soviet Cinema’, in Bahun, S. & Haynes, J. (eds) Cinema, State Socialism and Society in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, 1917–1989 (London, Routledge).

- Rajagopalan, S. (2008) Indian Films in Soviet Cinemas: The Culture of Movie-Going After Stalin (Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press).

- Rakowska-Harmstone, T. (1983) ‘Islam and Nationalism: Central Asia and Kazakhstan Under Soviet Rule’, Central Asian Survey, 2, 2.

- Remeikis, T. (1980) Opposition to Soviet Rule in Lithuania, 1945–1980 (Chicago, IL, Institute of Lithuanian Studies Press).

- Risch, W. (2011) The Ukrainian West: Culture and the Fate of Empire in Soviet Lviv (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

- Rolf, M. (2014) ‘Die Nationalisierung der Sowjetunion: Indigenisierungspolitik, nationale Kader und die Entstehung von Dissens in der Litauischen Sowjetrepublik der Ära Brežnev’, in Belge, B. & Deuerlein, M. (eds).

- Rorlich, A.-A. (1986) The Volga Tatars: A Profile in National Resilience (Stanford, CA, Hoover Institution Press).

- Roth-Ey, K. (2011) Moscow Prime Time: How the Soviet Union Built the Media Empire That Lost the Cultural Cold War (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Rupprecht, T. (2010) ‘Gestrandetes Flaggschiff. Die Universität der Völkerfreundschaft in Moskau’, Osteuropa, 1.

- Rupprecht, T. (2015) Soviet Internationalism After Stalin: Interaction and Exchange Between the USSR and Latin America During the Cold War (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Saroyan, M. (1997) ‘Rethinking Islam in the Soviet Union’, in Saroyan, M. & Walker, E. W. (eds) Minorities, Mullahs and Modernity: Reshaping Community in the Former Soviet Union (Berkeley, CA, University of California Press).

- Shahrani, M. N. (1994) ‘Islam and the Political Culture of “Scientific Atheism” in Post-Soviet Central Asia: Future Predicament’, Islamic Studies, 33, 2/3.

- Shanin, T. (1989) ‘Ethnicity in the Soviet Union: Analytical Perceptions and Political Strategies’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 31, 3.

- Sheehy, A. (1966) ‘The Tashkent Earthquakes’, Central Asian Review, 14, 1.

- Shin, B. (2017) ‘Inventing a National Writer: The Soviet Celebration of the 1948 Alisher Navoi Jubilee and the Writing of Uzbek History’, International Journal of Asian Studies, 14, 2.

- Shukurova, K. S. (1974) ‘Znachenie kul’turnykh svyazei Uzbekistana s zarubezhnymi stranami’, in Khairullaev, M. (ed.) Bratstvo Narodov i Internatsional’noe Vospitanie (Tashkent, Tashkentskii Gosudarstvennyi Universitet).

- Simon, G. (1986) Nationalismus und Nationalitätenpolitik in der Sowjetunion (Baden-Baden, Nomos).

- Slezkine, Y. (1994) ‘The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism’, Slavic Review, 53, 2.

- Sluga, G. (2013) Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism (Philadelphia, PA, University of Pennsylvania Press).

- Smith, J. (2013) Red Nations. The Nationalities Experience in and After the USSR (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Smolii, V. (2004) Krymski Tatary: Shlyakh do Povernennya (Kyiv, Ukrainian History Institute).

- Subtelny, O. (2009) Ukraine: A History (Toronto, University of Toronto Press).

- Suny, R. G. (2001) ‘Constructing Primordialism: Old Histories for New Nations’, Journal of Modern History, 73, 4.

- Suny, R. G. (2012) ‘The Contradictions of Identity: Being Soviet and National in the USSR and After’, in Bassin, M. & Kelly, C. (eds) Soviet and Post-Soviet Identities (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Suny, R. G. (ed.) (2014) The Structure of Soviet History (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Swain, G. (2012) ‘Before National Communism: Joining the Latvian Komsomol Under Stalin’, Europe-Asia Studies, 64, 7.

- Ter Minassian, T. (2007) Erevan: La Construction D’une Capitale à L'époque Soviétique (Rennes, PU Rennes).

- Tondera, B. (2019) Reisen auf Sowjetisch: Auslandstourismus Unter Chruschtschow und Breschnew 1953–1982 (Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz).

- Tursunov, F. I. (1974) ‘Stroitel’stvo novogo Tashkenta—voploshchenie idei druzhby i vzaimopomoshchi narodov SSSR’, in Khairullaev, M. (ed.) Bratstvo Narodov i Internatsional’noe Vospitanie (Tashkent, Tashkentskii Gosudarstvennyi Universitet).

- Unger, A. (1981) ‘Political Participation in the USSR: YCL and CPSU’, Soviet Studies, 33, 1.

- Vardys, V. S. & Sedaitis, J. (1997) Lithuania: The Rebel Nation (Boulder, CO, Westview).

- Vyzgo, T. S. (1974) ‘Uglublenie internatsional’nogo soderzhaniya uzbekskoi sovetskoi muzyki’, in Khairullaev, M. (ed.) Bratstvo Narodov i Internatsional’noe Vospitanie (Tashkent, Tashkentskii Gosudarstvennyi Universitet).

- Wojnowski, Z. (2018) The Near Abroad: Socialist Eastern Europe and Soviet Patriotism in Ukraine, 1956–1985 (Toronto, Toronto University Press).

- Zhuk, S. (2010) Rock and Roll in the Rocket City: The West, Identity and Ideology in Soviet Dniepropetrovsk. 1960–1985 (Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press).

- Zisserman-Brodsky, D. (2003) Constructing Ethnopolitics in the Soviet Union: Samizdat, Deprivation and the Rise of Ethnic Nationalism (London, Palgrave Macmillan).