?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The article investigates the extent of political favouritism in the central financing of local governments in Hungary between 2015 and 2018. An investigation of various transfers and the role of both mayor and member of parliament (MP) in the granting of funds enabled me to map how grant schemes relate to pork-barrelling. The rewarding of core supporters is observable with regard to discretionary intergovernmental transfers, while the political alignment affects the distribution of EU funds; thus, these constitute the primary mechanisms for acknowledging and sharing credit with local leaders. When a grant scheme requires municipalities to file an application for funding, local governments in opposition receive fewer grants.

Under fiscal federalism, the proper allocation of public tasks between central and subnational governments increases social wellbeing across the board (Oates Citation2005). Nevertheless, to fully realise the advantages of decentralisation, those who reap the benefits must bear the associated costs in both time and space. Otherwise, the social welfare derived from decentralisation might be compromised (Vasvári Citation2022). For example, breaching the golden rule—that is, financing current expenses from long-term loans—leads to the unfair distribution of financial burdens between generations (Musgrave Citation1959). Similarly, the increasing financial dependency of local government on central funds—for example, the centralisation of local income and compensation via intergovernmental transfers—may also lead to spatial inequalities and the inefficient allocation of funds, especially if fund distribution lacks objective and transparent guidelines (Vasvári Citation2022).

In Hungary, local governance was subject to fundamental reform a decade ago, in 2013. This was characterised by centralisation of public services (for example, education, healthcare). As a result, the municipal sector was halved between 2010 and 2021 (Hungarian Central Statistics Office Citation2022b). As the local taxation system remained unchanged, the reform was expected to improve vertical fiscal imbalance; in other words, the share of intergovernmental transfers in municipal budgets should have dropped. However, as local taxes became an integral part of redistribution mechanisms, and the spending of local taxes was further limited by law, the dependence of municipalities on financial transfers from the central government has in fact grown since the reform (Vasvári Citation2021). In addition, the extent of discretionary grants has also increased, making municipalities even more exposed to central decisions and political interests. However, as Papp (Citation2019) points out, pork-barrel politics is not limited to intergovernmental transfers. Supranational funds, such as transfers from the EU, may also be subject to political bias, especially in transition countries, who are the main beneficiaries of these grants. According to prior studies, Hungary has also demonstrated political bias in this regard, and the involvement of the central government in fund allocation has increased since 2010 (Muraközy & Telegdy Citation2016; Vasvári Citation2022).

This article aims to explore political favouritism in the financing of Hungarian local governments in the political cycle of 2015–2018. Although there is an extensive literature on political favouritism, analysis of the Hungarian case in the period specified will provide several new contributions. First, while Hungary, a postsocialist country, has been a member of the European Union since 2004, there are signs of democratic backsliding (Greskovits Citation2015; Kornai Citation2015; Bogaards Citation2018; Győrffy Citation2020). Rule-of-law concerns have been raised by the European Commission (Bayer Citation2022), and the European Parliament declared, in 2022, that Hungary could no longer be considered a full democracy.Footnote1 The growing dependency of local governments on central funds, the increasing extent of discretionary grants and amendments to the distribution of EU funds for the programming period 2014–2020 are the main reasons to extend investigation to this period. Second, by constructing a novel dataset I am able to investigate the role of grant schemes in pork-barrel politics with regard to both intergovernmental discretionary transfers and EU funds. Third, although I mainly follow the usual methodology applied in the literature (see Migueis Citation2013; Muraközy & Telegdy Citation2016; Vasvári Citation2022), my approach includes several novelties. I jointly investigate the role of two dominant local leaders, the mayor (elected in all settlements) and the locally elected member of parliament (MP). By applying regression discontinuity analysis, I am also able to test whether politicians reward partisanship of the local leaders or the grants are distributed considering the core supporters of the governing parties. To my knowledge, this is the first attempt to investigate such a combination of transfer types and channels of pork-barrelling in the financing of Hungarian municipalities.

The article is structured as follows. The next section provides a brief overview of the literature of political favouritism, followed by a description of the Hungarian case, data and the applied methodology, and then the results and discussion. The last section concludes.

Literature review

Early works on political favouritism mostly focused on how governments use financial resources to win swing districts (Lindbeck & Weibull Citation1987; Ward & John Citation1999; Case Citation2001; Johansson Citation2003) or reward core supporters (Cox & McCubbins Citation1986)—that is, grant distribution considers the share of supporters of the government. More recently, party alignment between central and local leaders has also been investigated in the literature. Applying regression discontinuity design for municipal elections between 1989 and 2001 in Portugal, Migueis (Citation2013) found that aligned municipalities received approximately 19% more targetable transfers than unaligned municipalities; however, formula-based grants and EU transfers were mostly shielded from political bias. The author also showed that rewarding core supporters significantly affected the allocation of transfers. In the case of Portuguese national elections, Veiga and Veiga (Citation2013) found that intergovernmental transfers increased in election years, and that the central government primarily targeted municipalities where a greater loss of votes was expected. Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro (Citation2008) analysed grants received by the Spanish municipalities and argued that alignment with the state government was rewarded with significantly more transfers. Bracco et al. (Citation2015) explored the issue from both theoretical and empirical aspects and found that Italian municipalities were rewarded with an increase in grants between 36% and 47% if they were politically aligned with the central government. Taking the case of four Nordic countries, Tavits (Citation2009) argued that pork-barrelling was likely to be universal and not only related to presidentialism, strong party systems or developing democracies. The German case was researched by Kauder et al. (Citation2016), who found that settlements having more core supporters of the incumbent state government were awarded with more discretionary grants. The authors also found that formulaic transfers were not politically biased; unlike in Brazil, where Litschig (Citation2012) found that even formulaic transfers may be politically biased by manipulating the input variables, such as population. While most of the literature identifies favouritism with the alignment of the mayor with the ruling party, some studies consider the alignment of members of parliament (MPs) in fund distribution. By exploring the transfers provided to the single-member districts (SMD) in Romania, Coman (Citation2018) found that local leaders could attract central funds as their open support of the ruling party resulted in more local votes for it. Papp (Citation2019) investigated the Hungarian case between 2007 and 2010 and found a correlation between a higher amount of EU funds transferred to an SMD and the electoral performance of incumbent government MPs. If the mayor was also aligned with the government, MP performance was boosted even further.

Political bias in central grants or governmental decisions is a well-known issue in Hungary. Kornai (Citation2014) found evidence of political clientelism in the bailout of local governments by the central government between 2011 and 2014. The mechanisms and importance of informal arrangements in central granting decisions is further explored by Jelinek (Citation2020). Vasvári (Citation2020) investigated the central decisions on local borrowing applications between 2012 and 2017 and found that unaligned local governments were less likely to receive governmental approval; thus, they had limited access to the financial markets. Muraközy and Telegdy (Citation2016) investigated the distribution of EU funds between 2004 and 2012 and found that politically aligned local governments had higher project acceptance rates; also, EU subsidies were beneficial for incumbent mayors in forthcoming local elections. Gregor (Citation2020) found that, during the national elections of 1998 and 2002, swing and poorer local governments were politically targeted and received larger intergovernmental transfers. Vasvári (Citation2022) explored the effect of alignment from both the local and central perspective between 2006 and 2018 and found that aligned local governments were more likely to have a budget deficit and could expect more discretionary grants and EU funds.

Institutional background

Local governance was re-established in Hungary right after the transition in 1990. The local tier was characterised by high fragmentation and extensive responsibilities, which is considered a unique mix among European countries (Vigvári Citation2010; Vasvári Citation2022).Footnote2 The economic basis of municipal autonomy lay in their assets, the power to levy local taxes, block grants from the central government, and a presence on financial markets (Kopányi et al. Citation2004). In the early 2000s, the share of earmarked grants in central funding increased; tax income gradually became part of redistribution mechanisms (that is, settlements with higher tax income received smaller transfers from the state), and further public responsibilities (for example, in the fields of education, family care, healthcare) were allocated to the local level (Kákai & Vető Citation2019). This resulted in financial tension between available resources and responsibilities, and the de jure decentralised, de facto increasingly centralised system concealed the softening of budget constraints (Rodden Citation2002), as financial autonomy of municipalities was curtailed but no tight fiscal rules were imposed on them, allowing them to run deficits and rack up large debts. Not surprisingly, a massive wave of municipal borrowing swept the country from 2006, which was only halted by the financial crisis of 2008 (Vasvári Citation2013).

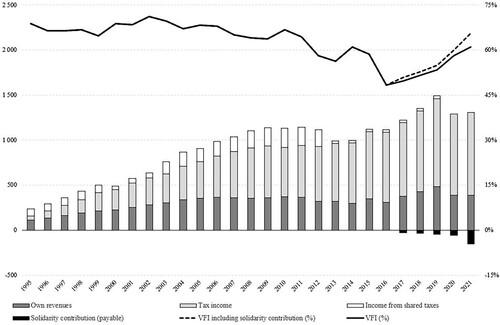

After 2010, the new government—a coalition of Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People’s Party (Kereszténydemokrata Néppárt—KDNP) that won the election by a two-thirds majority—made centralisation the focus of public reforms (Dobos Citation2021; Karas Citation2021). The new governing concept was labelled ‘illiberal democracy’, a sharp departure from the existing major reform paradigms, such as New Public Management, New Public Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State (Kornai Citation2015; Hajnal & Rosta Citation2019).Footnote3 The democratic U-turn also affected local services: some public tasks (for example, in the fields of education and healthcare), were re-centralised. Counties are currently solely tasked with conceptualising regional development; however, they gained an important role in the allocation of EU funds to local governments from 2014. Due to the reform, municipal expenditure compared to GDP dropped from 12.4% to 6.1% between 2010 and 2021 (Hungarian Central Statistics Office Citation2022b). As the local taxation system remained unchanged, the anticipation was that reliance on central transfers would diminish, as local tax incomes were now matched to smaller responsibilities (Vasvári Citation2021). Indeed, as illustrates, the vertical fiscal imbalance (VFI)Footnote4 significantly dropped between 2014 and 2016; however, the decline in central dependency turned out to be brief and only superficial. The reasons are threefold. First, local tax income became an important part of the redistribution mechanism (more revenue from local taxes translated to fewer central transfers). Second, the utilisation of local tax revenue, particularly from local business taxes, has been legally constrained since 2016 (Vasvári Citation2021). Third, local governments with high local tax income were obliged to pay a ‘solidarity contribution’ to the central budget from 2017, which has also contributed to the rebound of VFI (Vasvári Citation2021). At the same time, the extent of discretionary grants compared to the local budgets rose between 2015 and 2020 (from 0.6% to 3.7% relative to the total local budgets), suggesting that the exposure of municipalities to central decisions and political interest may have grown (Vasvári Citation2021).

FIGURE 1. Local Income of Municipalities (HUF Billion) and VFI (%)

Source: Hungarian Central Statistics Office (Citation2022b).

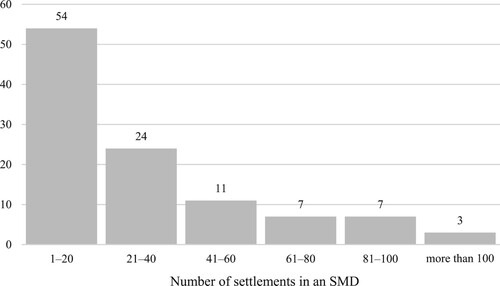

The pre-2014 Hungarian election system is thoroughly presented by Gregor (Citation2020); however, there have been some important amendments since then. Most importantly, there is now only a single round of parliamentary elections, whereas previously, two rounds were conducted; local elections are now held every five years (decoupling them from national elections); and elected mayors can no longer simultaneously hold a parliamentary seat.Footnote5 Now, 106 of the 199 MPs are directly elected in single-member districts (SMD), while the remainder receive their mandate from the votes cast for a party list. The number of settlements represented by a directly elected MP may vary; while some districts consist of one, some may have over 100 settlements (see ). Mayors and members of a city council are directly elected, while people living outside Budapest and major cities (cities with county rights, see Table A1 in the online Appendix) also vote for the members of the County Council.

FIGURE 2. Settlements in SMDs, 2014

Source: National Election Office (Citation2022).

Dąbrowski (Citation2013) presents the EU Cohesion Policy and allocation mechanism by using case studies from Poland, Czechia and Hungary. Muraközy and Telegdy (Citation2016) describe the Hungarian institutional setting and note that member states have considerable freedom to determine their institutions and rules of fund allocation. According to the authors, the managing authorities were subject to close political supervision between 2004 and 2012. In 2014, these bodies were not only subject to government supervision but merged into several ministries (for example, Ministry of National Development, Ministry for National Economy) based on Operative Programmes.Footnote6 At the same time, the allocation of the Territorial and Settlement Development Operative Programme (TSDOP), the most important source of EU funds that targets local governments, became somewhat decentralised, and now county municipalities actively participate in the planning and decision-making processes in distribution of these transfers. As the governing parties have held a majority in each County Council since 2010, these bodies are now able to influence the flow of these grants.

In summary, pork-barrelling in general and the Hungarian case in particular are well represented in the literature. However, I identified some areas to develop. First, by applying regression discontinuity design, I was able to test the core-supporter hypothesis along with the importance of the local leaders’ alignment. I also investigated an additional channel of political favouritism by analysing the role of MPs in funds’ distribution. Finally, my novel dataset, consisting of various discretionary intergovernmental transfers, enabled an exploration of the relationship between grant schemes and pork-barrelling.

Model and data

Descriptive statistics

The data regarding the political variables came from the National Election Office.Footnote7 For local settlement leadership, the key variable is the elected mayor and their political affiliation.Footnote8 They are regarded as aligned if they were nominated directly by the governing alliance, namely Fidesz or KDNP in the examined period. Regarding the unaligned mayors, I distinguish between those who were nominated by an opposition party and those who were independent, applying a similar approach used by Fink and Stratmann (Citation2011). Second, for representation of the settlements in the national politics, I use a variable for the partisanship of the elected member of the parliament in the corresponding SMD; their classification is the same as that of the aligned mayors. For each case, I considered the results of the parliamentary and local elections held in 2014 (in April and October, respectively).

shows the descriptive statistics of the variables, while Figure A1 in the online Appendix shows the geographical distribution of mayor alignment. It is obvious that independent municipalities are smaller settlements, with lower budgets, fewer assets and less tax power. Due to the fractured municipal system of numerous small settlements, many local governments are outside the sphere of interest of party politics, meaning that mayors run in the local elections without support from any national parties. Consistently, settlements governed by opposition mayors exceeded other groups in terms of average population, population density and tax income. This suggests that opposition strongholds are predominantly concentrated in larger cities, while governing parties exhibit a higher level of influence in rural areas and smaller settlements.

TABLE 1 Local Government Characteristics According to Political Alignment

The situation is similar in the case of MPs: there were only ten unaligned members of parliament, representing 24 settlements (including 11 districts of Budapest);Footnote9 however, these represented larger constituencies, with higher employment and taxation capacities.

The dependent variables are the per capita supplementary intergovernmental grants and EU funds. Supplementary grants are important central finance tools that are used to manage inequalities among settlements that cannot be addressed by formulaic transfers. Such grants may be given in the case of fiscal or economic shocks, or as funding for municipal projects, while varying public responsibilities may also require extra funds (for example, the operation of river ferries or public transport in urbanised areas; the maintenance of cultural heritage). In this study, I consider supplementary grants, where the government has some extent of discretion (that is, purely formulaic transfers are omitted).

The first kind of supplementary grants are transfers that are included in the budget bill adopted by parliament, which are subject to application or based on calculations by the relevant ministry. These semi-discretionary grants include additional and extraordinary grants for delivering public services (such as water and sewerage services, public transport, chimney sweep services, public catering) and financing municipal projects, such as the development or renovation of public buildings or infrastructure (kindergartens, schools, roads, pavements). For simplicity, these grants are labelled here as application-based transfers. The second kind are targetable grants, based solely on government decrees, assessed by the highest level of the central government (that is, in cabinet meetings). These fully discretional transfers have various purposes, ranging from additional support for public services to the funding of municipal projects.

Data regarding these grants are taken from the final statement made by the local governments (Form 11/A), provided by the Hungarian State Treasury for each municipality. Discretionary transfers considered in the analysis totalled HUF410 billion (approximately €1.14 billion), comprising 7.1% of total intergovernmental funds in the examined period.

The host of the distributed EU funds is the Ministry of Innovation and Technology, whose data are organised in a database by the NGO Atlatszo (atlatszo.hu).Footnote10 A total of HUF1,396 billion (€3.9 billion) was awarded for municipal projects between 2015 and 2018, of which HUF1,096 billion was distributed under the TSDOP, the most important source of EU funds for local governments. Municipalities have to apply for EU funds, however, data are only available for successful applications.

Methodology

The empirical part of the study aims to capture the extent of pork-barrelling from three perspectives. First, I perform an OLS regression on the annual average per capita funds received. The model is as follows:

where i denotes each local government, and j each type of grant analysed (application-based and targetable transfers, EU funds). The alignment of the mayor is measured by two dummies: ‘mayor aligned’ is 1, if the mayor was nominated by the governing parties, zero otherwise. Similarly, ‘mayor opposition’ is 1, if the mayor was aligned to the opposition, zero otherwise. Settlements with an independent mayor are the point of reference.

The classification of MPs follows that of the aligned mayors: 1 if they belonged to the governing alliance, zero otherwise. I also marked districts of Budapest and cities with county rights as ‘flagship’ municipalities, as these are the most populated and economically advanced local governments; the corresponding 46 municipalities represent 36.8% of the total population and 35% of the total municipal sector budget (see Table A1 in the online Appendix). Therefore, the ‘flagship’ variable captures both the level of urbanisation and the importance of these cities in national politics. A regional dummy is included when EU funds are considered, as Budapest (including its districts) and Pest County had lower access to EU funds due to their relatively higher level of development. Xi includes the general control variables: log population density controls for urbanisation:Footnote11 while the share of operation expenditures captures the extent of public services in municipal budgets (Muraközy & Telegdy Citation2016). The share of tax income in total municipal revenue correlates highly with the GDP produced and thus controls for economic factors. Socioeconomic background is captured by the rate of unemployment and the proportion of the population older than 65; higher values may result in more central transfers. Comparisons are drawn with the preceding political cycle of 2011–2014 to assess the impact of MPs on fund distribution, both before and after the legislative changes implemented from 2014.

Secondly, we continue with regression discontinuity design (RDD), which is my main identification strategy. I included ‘margin of victory or loss’ in the general model, which is calculated differently on both sides of the discontinuity, based on Migueis (Citation2013): if the aligned mayor won the election, the margin of victory equals the difference of the aligned vote share and the runner-up candidate (right side); if a government party candidate lost the election, the margin of loss is their vote share minus the winning candidate (see geographical distribution of the margin variable in Figure A2 in the online Appendix).

RDD has multiple advantages. First, it allows us to investigate whether settlements governed by aligned or unaligned mayors differ systematically. Second, it illustrates whether core supporters or local leaders attract more transfers; according to the core-supporters hypothesis, per capita transfers should increase as vote margin increases. If the alignment of the mayor also plays a role in the distribution of transfers, there will be a ‘jump’ at the cut-off point. Third, RDD accounts for the potential overestimation of political variables and reverse causality between political variables and transfers.

Thirdly, I investigate whether distribution of discretionary and EU funds benefited parties in the national election in 2018. I mainly follow the approach of Muraközy and Telegdy (Citation2016); in the OLS model specified below, the dependent variable is the difference in share of government supporting votes between 2014 and 2018, cast on the party list.

The main right-side variable is the logged change in percentage of grants in the period of 2015 and 2018, compared to the prior four-year period of 2011–2014. I controlled for the annual average grant per capita of the previous cycle, the alignment of the incumbent MP, while lagged votes of the previous national election controlled for any unobserved heterogeneity between settlements, possibly affecting the election outcomes.

includes the same controls as the baseline specification.

The analysis accounts for all local governments with the following limitations. The counties and the Metropolitan Municipality of Budapest are omitted due to their special territorial status; however, I included the districts of Budapest.Footnote12 Several smaller settlements were left out due to lack of data. In the case of EU funds, the estimation only includes local governments that had received grants. The OLS estimates for all local governments (N = 3,155) are shown. I narrowed the examination to the settlements that had a mayoral candidate aligned with the ruling parties in the local election held in 2014 (N = 918). In this regard, settlements channelled into national party politics through the affiliation of their mayoral candidates are assessed, regardless of their size. I continued with an evaluation of the RD estimates on the same set of municipalities (N = 918), also presenting the results for larger settlements with population over 10,000 (N = 161), as the nature of local politics might be different above this threshold (Soós & Kákai Citation2010; Kovarek & Dobos Citation2023).

Results

OLS estimation

Estimations are presented in . The upper section includes the estimation for all settlements, while the bottom section describes the narrowed set of municipalities with aligned mayor candidate. For each type of grant four estimations are provided: column (1) considers whether the mayor is aligned to government or not, while column (2) also flags settlements led by an opposition mayor. Column (3) investigates the role of MP alone, while the last column (4) shows the estimations when all political variables are considered jointly.

TABLE 2 OLS Estimations for 2015–2018

It is obvious that settlements led by aligned mayors received more transfers, whether central government grant or EU funds. However, transfers received by opposition municipalities show some dependency on the grant scheme: in case of application-based grants, the disfavouring of opposition settlements greatly exceeded the extent to which aligned municipalities were favoured. However, in case of targetable transfers, the extent of disfavouring is low and not significant. EU funds show a mixed picture; disfavouring is only significant in the case of opposition settlements when an aligned mayoral candidate was running for election.Footnote13 The effect of MP on fund distribution is estimated to be significant only in the case of EU funds. Control variables behave as expected: lower population density and tax income correlate to more transfers, which may be due to compensation of poorer and economically underdeveloped settlements. Settlements with high unemployment and a significant elderly population received more transfers.

As discussed previously, the emerging importance of MPs on the distribution of EU funds may be due to the institutional changes in distribution mechanisms and the legislative change that prohibited mayors from serving simultaneously as MPs, both effective from 2014. To test this hypothesis, I performed the same estimation regarding for the political cycle of 2011–2014. Due to the lack of a detailed and complete dataset of corresponding supplementary grants (Form 11/A was applied only from 2014), I relied on my own collected data for discretionary grants and included only the narrowed set of settlements. I found that although aligned MPs may have attracted more transfers, this was not estimated to be significant, while mayoral affiliation is estimated to be similarly important in the period 2011–2014 (see the results in Table A3 in the online Appendix).

Regression discontinuity estimation

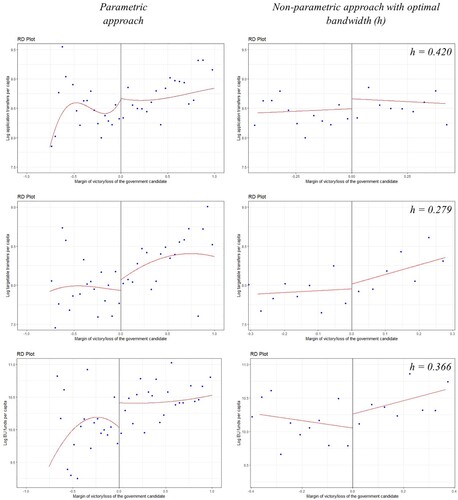

The main results of the regression discontinuity analysis are presented in . The best fit plots (based on AIC) of the global approach are displayed on the left side, while the right side represent the non-parametric linear estimations, using the optimal bandwidth based on Imbens and Kalyanaraman (Citation2012). I found that alignment with governing parties was rewarded in the case of EU funds (lower row), while targetable transfers were only slight affected by ‘mayor aligned’ and primarily followed core supporters (middle row). The distribution of application-based transfers is even at both sides of the cut-off point (upper row).

FIGURE 3. RD Plots Applying Parametric and Non-parametric Estimations

Notes: Margin is measured on the x-axis, while log grant value per capita is measured on the y-axis. Red lines represent the predicted values of best fit global polynomial estimations (left hand side), and local linear estimation with optimal bandwidth (right hand side) based on Imbens and Kalyanaraman (Citation2012), applying triangular kernel and 20 intervals on both sides.

presents the regression results for RDD estimation, including four different specifications. The columns labelled 1, 2 and 4 are the same as applied in the OLS analysis, while the first column includes only the dependent, the treatment and the running variables.Footnote14 I found that in the case of application-based grants, the disfavouring of opposition-led settlements was still observable, while in the case of targetable transfers, none of the political variables were estimated to be significant. Vote margin, that is, the rewarding of core supporters, played an important role in both cases. EU funds seemed to be affected predominantly by the alignment of both the mayor (simultaneous favouring and disfavouring) and the MP.

TABLE 3 RDD Estimations for 2015–2018

Looking at the larger settlements (population over 10,000), a different picture emerges: there is a noticeable jump in the case of targetable transfers, while EU funds and application-based transfers seem less biased (see Figure A3 in the online Appendix). This is also reflected by the estimations presented in Table A5: in the case of targetable transfers, aligned mayors were rewarded to a significant extent, greatly exceeding the estimation of the baseline scenario (1.037 compared to 0.183). Even in the case of application-based transfers, the favouring of aligned settlements is observable as opposed to the disfavouring of opposition settlements. The estimations regarding the EU funds behave somewhat similar to the baseline scenario, but they are not significant.

Impact of awarded grants on the election outcome

In this section I estimate whether targeting of central grants paid off for the government in the 2018 national election. Due to the lack of data (described above), I provide estimations for discretionary grants and EU funds. The estimated coefficients are presented in , suggesting that EU funds had some impact on the election results.

TABLE 4 Impact of Grants on Government Supporting Votes in the National Election of 2018

Discussion

This analysis confirms the existence of political favouritism in the financing of local governments in Hungary, and the results provide new insights into how grant schemes affect pork-barrelling in distribution mechanisms. First, the rewarding of core supporters is observable in the case of discretionary grants, namely application-based and targetable transfers; in these cases, transfers are aimed to increase the popularity and vote share of the governing alliance. The distribution of EU funds is biased primarily by the alignment of the incumbent mayor and MP. Second, somewhat surprisingly, targetable transfers are independent from the alignment of local leaders (both mayors and MPs); however, in the case of larger settlements, the alignment of the mayor seemed decisive. Third, when a grant scheme requires local governments to file an application or when the corresponding ministries have some discretion over the transfer amount, be it a government grant or an EU project, it is more likely that settlements in opposition will receive fewer transfers. This effect increases even among those settlements with an aligned but unsuccessful mayoral candidate. There are various possible reasons. Although application-based grants are generally open to all settlements, it is likely that opposition municipalities submit fewer application than aligned ones. As Muraközy and Telegdy (Citation2016) note, application calls may be personalised; aligned municipalities may be informed about short deadlines or file more applications in hope of success, while the high chance of rejection may lead unaligned municipalities to refrain from submission. Our results align with these findings: settlements with MPs in alignment exhibit a fivefold increase in successful EU fund applications per capita, and municipalities led by aligned mayors boast twice as many awarded applications compared to those in opposition, relative to their population.Footnote15 RD estimates for larger settlements—despite the low number of observations—underline the findings of previous research arguing that the nature of local politics and the involvement of settlements in national politics differs for municipalities with a population of over 10,000 (Soós & Kákai Citation2010; Kovarek & Dobos Citation2023). summarises the results and maps how pork-barrelling is related to grant schemes.

TABLE 5 Mapping of Grant Schemes to Channels of Pork-Barrelling

What may central government expect from redirecting these transfers? According to Coman (Citation2018), preferring aligned settlements in fund distribution is linked with the competition for ‘credit’: local and national politicians both try to convince voters that they are responsible for winning funds for local projects. However, if local leaders are unaligned, or aligned with the opposition, this competition may be fierce and uncertain. When local leaders are aligned, central and local leaders may share credit; based on their current political interests, they can even adjust how the role of the central or local government is communicated to voters. In Hungary, the central government shares credit for EU funds with local leaders, increasing the popularity of the mayor and the MP at the same time. Application-based and targetable transfers are intended mainly to increase the government’s vote share. In this regard, Migueis (Citation2013) also notes that, beyond simply rewarding electoral support, extra grants may increase the local MP’s chances of re-election, which, in turn, may further increase the chances of the government parties in the next national elections. As I have shown, governmental influence on the allocation of EU transfers may have contributed to the success of the government parties in the 2018 national election. The extent of this influence (0.5% percentage points) is in line with the previous finding of Muraközy and Telegdy (Citation2016), who estimated the effect of EU transfers on votes for the incumbent mayor as around 0.4–0.8 percentage points.

Although Mares and Young (Citation2018) provide insights into how clientelist linkages and mechanisms between politicians, state employees (as brokers) and voters directly influence election results, little is known about how local politicians manipulate central fund distribution in Hungary. Policies that favour certain localities suggest that there are informal, bottom-up processes in which requests and needs are delivered within the party organisations or directly to the ministries or managing authorities. Jelinek (Citation2020) provides the following example with regard to targetable transfers:

In this case, tender is not submitted. Instead, an A4 letter is written, which goes to 3–4 different e-mail and 3–4 different postal addresses. Afterwards, the mayor—relying on his governmental and party relations—gets into the company car and goes up to the capital, where he lobbies in several places. (Jelinek Citation2020, p. 131)

What is the extent of pork-barrelling? Considering the annual median value for the calculation, in the case of application-based discretionary grants, settlements with an opposition mayor received 58.4% fewer transfers than settlements with an independent mayor, that is, HUF4,390 (€13.5) per capita. Government-aligned larger settlements received around double the number of targeted transfers, approximately HUF1,760 (€5.40) per capita.

In the case of EU grants, an aligned mayor brings home 22% more transfers to a settlement (HUF8,600; €26.40 per capita), while opposition municipalities lose 41.7% (HUF16,280; €50 per capita), compared to the independent municipalities. An unaligned MP means HUF28,230 (€86.70) less in EU funds. My estimates show that political influence in the distribution of EU funds in the period of study grew compared to previous periods. For example, Muraközy and Telegdy (Citation2016), considering major settlements, found that settlements aligned with the governing parties received an additional HUF5,900 annually between 2004 and 2012. My analysis finds that aligned municipalities receive even more transfers (approximately 45% more); in addition, in the same time period settlements led by an opposition mayor were seriously disfavoured. Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro (Citation2008) estimated the effect of political alignment as €7–11 per capita in the case of Spanish intergovernmental transfers, which is similar in extent to my results regarding application-based transfers. I also found that settlements may receive additional EU funds if the mayor and the MP are both aligned, which is in line with the findings of Papp (Citation2019).

Conclusion

The parallel existence of increasing transfer dependency and political discretion in fund distribution results in a vulnerable local government system, where the future of current and following generations may depend on a good relationship with the central government. According to Kornai (Citation2014), this distracts the attention of local government: instead of making public service delivery more efficient and able to satisfy local needs, local leaders may focus mainly on their relationship with the central government. Consequently, local projects are financed only if the government decides accordingly. Such finance is regarded as a gift in return for political support,Footnote17 while those who do not benefit from these decisions or who are disadvantaged can be said to pay the price.

This article has investigated the role of local leaders in gaining central government funding in exchange for political support. Based on a novel dataset, I analysed different grant types, investigated the role both of the mayor and the locally elected MP. By applying regression discontinuity analysis, I was also able to test whether politicians reward the alignment of the local leaders or the core supporters, which enabled me to map how pork-barrelling is related to grant schemes (see ). I found that the rewarding of core supporters was observable in the case of both application-based and targetable discretionary transfers; thus, these transfers were designed to increase the popularity and vote share of the governing alliance. Distribution of EU funds was biased solely by the alignment of the incumbent mayor and MP, consequently, these instruments were used primarily to share credit with local leaders, namely the mayor and the MP. Targetable transfers, however, show a mixed picture, as alignment of the mayor proved to be crucial only in case of larger settlements. When a grant scheme requires local governments to file an application, or when the corresponding ministries have some discretion over the transfer amount, and whether it is an intergovernmental transfer or an EU project, it is more likely that settlements in opposition will receive less money. According to my results, MPs gained power over funds distribution after 2014 for two reasons: an amendment of the institutional system of EU fund distribution and the 2014 Hungarian law prohibiting mayors from serving simultaneously as MPs. Finally, I found that the politically managed distribution of EU funds could have contributed to the election outcome in 2018.

Based on my findings, central government may be advised to strive for more transparent and formulaic distribution of resources, reverse the recent shift towards discretionary transfers and decrease the dependency of the local tier on intergovernmental transfers; this all may help to establish the fair distribution of burdens. Until such changes, it is not surprising that unaligned local governments welcome any chance to bypass the current distribution mechanisms. For example, in a 2022 report, the European Parliament raised the possibility that Hungarian local governments could submit funding applications directly to the EU.Footnote18

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Disclosure statement:

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tamás Vasvári

Tamás Vasvári, University of Pécs Faculty of Business and Economics, Centre of Excellence in Economic Studies, Rákóczi út 80, Pécs 7622, Hungary. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 ‘MEPs: Hungary Can No Longer Be Considered a Full Democracy’, European Parliament, 15 September 2022, available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220909IPR40137/meps-hungary-can-no-longer-be-considered-a-full-democracy, accessed 3 October 2022.

2 See the general characteristics of the local tier in Table A1 of the online Appendix.

3 In the words of Bogaards, ‘never in the history of the European Union has an election in a member state resulted in political, legal, economic and administrative changes of this magnitude in such a short period’ (Bogaards Citation2018, p. 1841).

4 Vertical fiscal imbalance is calculated by the share of intergovernmental transfers and EU funds in total municipal budgets, based on the methodology applied by Aldasoro and Seiferling (Citation2014).

5 Eighty-nine of the total of 386 MPs were also mayors between 2010 and 2014.

6 Operational Programmes (OPs) dissect the overarching strategic objectives established in the Partnership Agreement between the EU and the member state. They delineate investment priorities, specify objectives and further detail concrete actions to be taken.

7 Despite the issues of democratic backsliding, the results of the elections are still considered reliable; see the latest report of Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Citation2022).

8 Including the composition and political affiliation of the city council would be cumbersome. Also, in most local governments in the period under study, the mayor had a majority.

9 The relatively low number of opposition mayors and settlements represented by unaligned MPs may skew the results, and I have taken this into account in the analysis.

10 The database is based on the funded projects, as they appeared on the EU application portal and on the related page, available at: https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/tamogatott_projektkereso, accessed 19 October 2020. For further details, see: https://atlatszo.hu/kozpenz/2016/03/31/interaktiv-terkepen-mutatjuk-meg-hogy-mennyi-eu-s-penzt-kaptak-a-magyar-telepulesek/, accessed 19 October 2020.

11 Controlling for population size was dropped due to its high correlation with population density.

12 Budapest has a two-tier administration: the Metropolitan Municipality of Budapest, led by the Lord Mayor, has authority over the entire capital, while districts have their own local governments, similar to settlements in institutional structure, responsibilities and competencies.

13 In the case of political variables for mayor alignment, settlements with an independent mayor are the points of reference; thus, the gap between aligned and opposition municipalities is the difference of their estimated coefficients.

14 Inclusion of the MP variable alone (third specification in the OLS estimation) was not executable, because ‘mayor aligned’ was included by default as treatment variable.

15 Vasvári (Citation2020) shows that the central approval mechanism of local borrowing has similar patterns: aligned municipalities file 10% more applications than settlements in opposition.

16 However, there is only anecdotal evidence for how politicians can influence fund distribution. In 2018, for example it was even confirmed by the government that fewer EU funds were awarded to the town of Hatvan (with a population of 20,000) than to neighbouring settlements because the mayor and the local MP were at odds. Reports indicated that the MP exerted influence over the planning and decision-making processes, both within the county municipality and at the Ministry of Finance, which was responsible for overseeing the allocation of EU funds in this instance (Rovó Citation2018).

17 Anecdotal evidence further supports the strengthening patron–client relationship between municipalities and the central government. For example, at the inauguration ceremony of a football stadium financed by the government, the mayor of Szombathely noted that the townspeople received the project as a gift for their support to the ruling parties (Medvegy Citation2017).

18 ‘Challenges for Urban Areas in the Post-COVID-19 Era’, European Parliament Resolution (2021/2075(INI)) P9_TA(2022)0022, available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0022_EN.html, accessed 7 February 2024.

References

- Aldasoro, I. & Seiferling, M. (2014) Vertical Imbalances and the Accumulation of Government Debt, International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/14/209, available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Vertical-Fiscal-Imbalances-and-the-Accumulation-of-Government-Debt-42460, accessed 3 October 2022.

- Bayer, L. (2022) ‘EU Launches Process to Slash Hungary’s Funds Over Rule-of-Law Breaches’, Politico, 5 April, available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-commission-to-trigger-rule-of-law-budget-tool-against-hungary/, accessed 27 April 2022.

- Bogaards, M. (2018) ‘De-democratization in Hungary: Diffusely Defective Democracy’, Democratization, 25, 8.

- Bracco, E., Lockwood, B., Porcelli, F. & Redoano, M. (2015) ‘Intergovernmental Grants as Signals and the Alignment Effect: Theory and Evidence’, Journal of Public Economics, 123.

- Case, A. (2001) ‘Election Goals and Income Redistribution: Recent Evidence from Albania’, European Economic Review, 45, 3.

- Central Office for Administrative and Electronic Public Services (2022) ‘Official Census on Population by Municipality 2010–2018’, available at: https://nyilvantarto.hu/hu/statisztikak, accessed 7 March 2022.

- Coman, E. E. (2018) ‘Local Elites, Electoral Reform and the Distribution of Central Government Funds: Evidence from Romania’, Electoral Studies, 53.

- Cox, G. W. & McCubbins, M. D. (1986) ‘Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Game’, Journal of Politics, 48, 2.

- Dąbrowski, M. (2013) ‘EU Cohesion Policy, Horizontal Partnership and the Patterns of Sub-National Governance: Insights from Central and Eastern Europe’, European Urban and Regional Studies, 21, 4.

- Dobos, G. (2021) ‘Institutional Changes and Shifting Roles: Local Government Reform in Hungary, 2010–2014’, in Marta, L., Szmigiel-Rawska, K. & Teles, F. (eds) Local Government in Europe: New Perspectives and Democratic Challenges (Bristol, Bristol University Press).

- Fink, A. & Stratmann, T. (2011) ‘Institutionalised Bailouts and Fiscal Policy: The Consequences of Soft Budget Constraints’, KYKLOS, 64, 3.

- Gregor, A. (2020) ‘Intergovernmental Transfers and Political Competition Measured by Pivotal Probability—Evidence from Hungary’, European Journal of Political Economy, 62, 101841.

- Greskovits, B. (2015) ‘The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe’, Global Policy, 6, S1.

- Győrffy, D. (2020) ‘Financial Crisis Management and the Rise of Authoritarian Populism: What Makes Hungary Different from Latvia and Romania?’, Europe-Asia Studies, 72, 5.

- Hajnal, G. & Rosta, M. (2019) ‘A New Doctrine in the Making? Doctrinal Foundations of Sub-National Governance Reforms in Hungary (2010–2014)’, Administration and Society, 51, 3.

- Hungarian Central Statistics Office (2022a) ‘STADAT Territorial Database on Non-budgetary Control Variables’, available at: https://statinfo.ksh.hu/Statinfo/themeSelector.jsp?lang = hu, accessed 7 March 2022.

- Hungarian Central Statistics Office (2022b) ‘21.1.1.17 Main Figures of the Government Sector’, available at: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/gdp/hu/gdp0017.html, accessed 24 October 2022.

- Hungarian State Treasury (2019) ‘Annual Accounts of Local Governments 2010–2021’, available at: https://www.allamkincstar.gov.hu, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Imbens, G. & Kalyanaraman, K. (2012) ‘Optimal Bandwidth Choice for the Regression Discontinuity Estimator’, Review of Economic Studies, 79, 3.

- Jelinek, C. (2020) ‘“Gúzsba kötve táncolunk” Zsugorodás és a kontroll leszivárgásának politikai gazdaságtana magyarországi középvárosokban’, Szociológiai szemle, 30, 2.

- Johansson, E. (2003) ‘Intergovernmental Grants as a Tactical Instrument: Empirical Evidence from Swedish Municipalities’, Journal of Public Economics, 87, 5–6.

- Kákai, L. & Vető, B. (2019) ‘Állam vagy/és önkormányzat? Adalékok az önkormányzati rendszer átalakításához’, Hungarian Political Science Review, 28, 1.

- Karas, D. (2021) ‘Financialization and State Capitalism in Hungary After the Global Financial Crisis’, Competition & Change, 26, 1.

- Kauder, B., Potrafke, N. & Reischmann, M. (2016) ‘Do Politicians Reward Core Supporters? Evidence from a Discretionary Grant Program’, European Journal of Political Economy, 45.

- Kopányi, M., Wetzel, D. & Daher, S. E. (2004) Intergovernmental Finance in Hungary—A Decade of Experience 1990–2000 (Washington, DC, The World Bank).

- Kornai, J. (2014) ‘The Soft Budget Constraint—An Introductory Study to Volume IV of the Life’s Work Series’, Acta Oeconomica, 64, 1.

- Kornai, J. (2015) ‘Hungary’s U-Turn: Retreating from Democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 26, 3.

- Kovarek, D. & Dobos, G. (2023) ‘Masking the Strangulation of Opposition Parties as Pandemic Response: Austerity Measures Targeting the Local Level in Hungary’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 16, 1.

- Lindbeck, A. & Weibull, J. (1987) ‘Balanced Budget Redistribution as a Political Equilibrium’, Public Choice, 52.

- Litschig, S. (2012) ‘Are Rules-Based Government Programs Shielded from Special-Interest Politics? Evidence from Revenue-Sharing Transfers in Brazil’, Journal of Public Economics, 96, 11–12.

- Mares, I. & Young, L. E. (2018) ‘The Core Voter’s Curse: Clientelistic Threats and Promises in Hungarian Elections’, Comparative Political Studies, 51, 11.

- Medvegy, G. (2017) ‘A szombathelyi polgármester szerint ajándékba kapták a stadiont’, 24.hu, 8 November, available at: https://24.hu/belfold/2017/11/08/a-szombathelyi-polgarmester-szerint-ajandekba-kaptak-a-stadiont/, accessed 27 April 2022.

- Migueis, M. (2013) ‘The Effect of Political Alignment on Transfers to Portuguese Municipalities’, Economics & Politics, 25, 1.

- Muraközy, B. & Telegdy, Á (2016) ‘Political Incentives and State Subsidy Allocation: Evidence from Hungarian Municipalities’, European Economic Review, 89.

- Musgrave, R. A. (1959) The Theory of Public Finance (New York, NY, McGraw-Hill).

- National Election Office (2022) ‘Results of Local and National Elections 2010–2018’, available at: https://www.valasztas.hu/1990-2019_eredmenyek, accessed 7 March 2022.

- Oates, W. E. (2005) ‘Toward a Second-Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism’, International Tax and Public Finance, 12, 4.

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (2022) ‘Hungary, Parliamentary Elections and Referendum, 3 April 2022: Election Observation Mission Final Report’, 29 July, available at: https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/523568, accessed 1 March 2023.

- Papp, Z. (2019) ‘Votes, Money Can Buy. The Conditional Effect of EU Structural Funds on Government MPs’ Electoral Performance’, European Union Politics, 20, 4.

- Rodden, J. (2002) ‘The Dilemma of Fiscal Federalism: Grants and Fiscal Performance Around the World’, American Journal of Political Science, 46, 3.

- Rovó, A. (2018) ‘Egy fideszes véletlenül írásba adta, hogy pofára osztják az EU-s pénzeket’, Index.hu, 8 February, available at: https://index.hu/belfold/2018/02/08/top_palyazatok_eu-s_penz_feszultseg_lazar_szabo_zsolt_nfm/, accessed 27 April 2022.

- Solé-Ollé, A. & Sorribas-Navarro, P. (2008) ‘The Effects of Partisan Alignment on the Allocation of Intergovernmental Transfers. Differences-in-Differences Estimates for Spain’, Journal of Public Economics, 92, 12.

- Soós, G. & Kákai, L. (2010) ‘Hungary: Remarkable Successes and Costly Failures: An Evaluation of Subnational Democracy’, in Hendriks, F., Lidström, A. & Loughlin, J. (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe (New York, NY, Oxford University Press).

- Tavits, M. (2009) ‘Geographically Targeted Spending: Exploring the Electoral Strategies of Incumbent Governments’, European Political Science Review, 1, 1.

- Vasvári, T. (2013) ‘The Financial Management of Local Governments in 2011 in Light of the Crowding-out Effect of Their Debt Service’, Public Finance Quarterly, 58, 3.

- Vasvári, T. (2020) ‘Hardening the Budget Constraint: Institutional Reform in the Financial Management of Hungarian Local Governments’, Acta Oeconomica, 70, 4.

- Vasvári, T. (2021) ‘Az iparűzési adó szerepe az önkormányzati gazdálkodás autonómiájában’, Comitatus, 31, 238.

- Vasvári, T. (2022) ‘Beneficiaries and Cost Bearers: Evidence on Political Clientelism from Hungary’, Local Government Studies, 48, 1.

- Veiga, L. G. & Veiga, F. J. (2013) ‘Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers as Pork Barrel’, Public Choice, 155, 3/4.

- Vigvári, A. (2010) ‘Is the Conflict Container Full? Problems of Fiscal Sustainability at the Local Government Level in Hungary’, Acta Oeconomica, 60, 1.

- Ward, H. & John, P. (1999) ‘Targeting Benefits for Electoral Gain: Constituency Marginality and the Distribution of Grants to English Local Authorities’, Political Studies, 47, 1.