Abstract

The past decade has seen significant growth in the tourism and hospitality literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR). Indeed, over 70% of the articles on this topic have been published in the past five years. Through the application of a stakeholder lens, this paper explores how CSR has developed within the extant literature, paying particular attention to current gaps and highlighting the contributions of the research in this special issue. This emerging research on CSR in the context of tourism and hospitality is pushing past the boundaries of early approaches to corporate sustainability by providing empirical evidence to support the importance of integrating a range of stakeholder perspectives and needs throughout the planning, implementation, and evaluation of CSR initiatives. We observe that while there is ample research on certain stakeholder groups such as management, employees, shareholders, and consumers, there is less emphasis on the role of communities and ecosystems as stakeholders and very little related to suppliers, NGOs, and government. Although tourism and hospitality firms may not be subject to the same pressures as other industries, there remain important opportunities to both document and engage these external stakeholders in the journey towards sustainability.

Introduction

In 1983, an environmental activist by the name of Jay Westerveld was travelling in the Pacific islands when he came across a placard in a hotel asking guests to reuse their towels for the sake of the environment. Westerveld saw this request from the hotel not as a gesture of altruism but rather, as a way for the hotel to save money – not the planet. A few years later, Westerveld published an essay based on this experience in which he coined the term “greenwashing” (Watson, Citation2016). Despite this early dialogue on the motivations for corporate social responsibility (CSR) in hospitality and tourism, it would take another three decades for academic research in this area to really get underway.

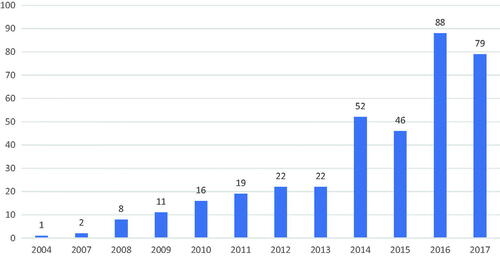

Indeed, it has only been in the last 10 years that we have started to see significant growth in this literature. In 2006, there were no articles published on CSR in tourism and hospitality; in 2007 there were two papers (Holcomb et al., 2007; Merwe & Wocke, Citation2007) and by 2016 the number of publications peaked at 88. In fact, a search of the Web of Science database for refereed books or articles that self-identified as being related to either CSR, corporate sustainability, corporate responsibility, or corporate social and environmental responsibility AND either tourism or hospitality (including research related to airlines, cruise ships, and restaurants) reveals that 366 articles have been published in journals and refereed conference proceedings on this subject, and over 70% of all articles on this subject have been published in the past five years (see ). Broadly, the focus of this paper is to take stock of the extant CSR literature in the disciplines of hospitality and tourism to critically explore how it has progressed and to draw insights into where it should be further developed in the future. More specifically, this paper positions the research included in this special issue in the context of existing literature, highlighting the gaps in knowledge that they address and the novel contributions that they offer.

As the content of the articles in this special issue took shape, we observed an unplanned yet distinct common thread that wove these pieces together: an emphasis on the fundamental role that stakeholders play within a firm’s CSR practises. This thread aligns nicely with Carroll’s 2016 reflection on his original CSR pyramid of CSR, in which he notes several recent appeals in the literature to redefine CSR from “corporate social responsibility”, to “corporate stakeholder responsibility”. It is, thus, through the lens of “stakeholders” that we critically examine how previous research on CSR in tourism and hospitality aligns with this current issue.

The concept of CSR has evolved since the 1950s, as society has placed greater expectations on companies (Carroll, Citation1999). The evolution of definitions of CSR has been shaped by how it is socially constructed (Dahlsrud, Citation2008). Rather than repeating well established definitions, it is worth relating the subject of this journal and its focus on sustainable tourism with the concept of CSR. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), typically known as the Brundtland Commission, defined sustainable development as meeting the current society’s needs without compromising the ability of future generations to do so. Sustainability, therefore, is the aim of both this journal and this special issue. Responsibility is the human response to that aim: it is a (relative) choice in relation to, firstly, accepting that sustainability is important and secondly, deciding which initiatives, activities, and other changes one is willing to undertake in response. Response(ability) relates to activities pursued to achieve a social good and performed to meet social requirements (McWilliams & Siegel, Citation2001; Perrini, Citation2006).

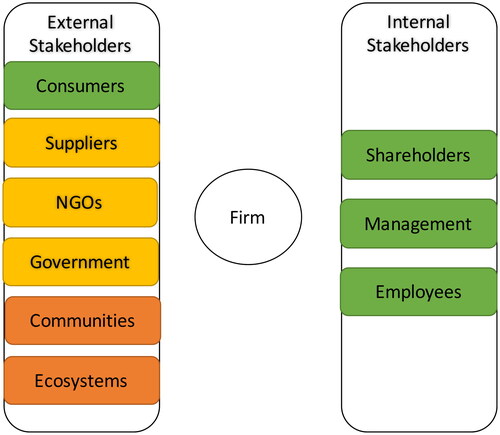

Responsibility is embedded within the five dimensions of CSR that are common to most definitions (Dahlsrud, Citation2008) and is linked to the concept of stakeholders. CSR is described as a process whereby individuals identify stakeholder demands on their organisations and negotiate their level of responsibility towards the collective wellbeing of society, environment, and economy (Dahlsrud, Citation2008). Such a description highlights that responsibility is socially constructed by organisations engaged in CSR. The degree to which an organisation acknowledges responsibility towards society determines how proactive their approach to CSR is and, therefore, the pro-activity of a stakeholder. It also determines whether their actions contribute towards shared wellbeing, depending on whether these actions are motivated by seeking benefits to oneself, to others, or to the biosphere (De Groot & Steg, Citation2008; Schultz, Citation2001). Under this conception of CSR stakeholders, and their relation to organisations engaged in CSR, lie key indicators of responsibility for individual CSR strategies. In short, by looking at how CSR strategies define and engage stakeholders, one can determine how inclusive and proactive a strategy is, as well as the breadth of its application (i.e. whom may benefit, and to what degree they will benefit, from its implementation). Figure 2 depicts the range of external and internal stakeholders that may be considered as part of a firm’s CSR practices. Stakeholders in the unshaded boxes (i.e. consumers, shareholders, management, and employees) are prominently discussed in tourism literature on CSR; stakeholders in the textured boxes (i.e. communities and ecosystems) are moderately but not widely discussed; and stakeholders in the shaded boxes (i.e. suppliers, NGOs and government) are virtually untouched in the literature.

Previous studies have mapped out the CSR literature in tourism and hospitality (e.g. Aragon-Correa, Martin-Tapia, & de la Torre-Ruiz, Citation2015; Coles, Fenclova, & Dinan, Citation2014; Farrington, Curran, Gori, O’Gorman, & Queenan, Citation2017). These studies have found that the lens used to study CSR is often determined by the reasons one has for investigating the practice, ranging from CSR as a tool for raising corporate profits, improving political performance, or increasing stakeholder accountability, through to CSR as a means for studying the ethics of decision-making (Garriga & Meléé, Citation2004). There is also agreement that there has been disproportionate attention paid to CSR as a tool for enhancing economic gain and corporate legitimacy.

In the spirit of providing a different (stakeholder centric) lens, this article is structured as follows. Accepting that CSR is a social construction, we start with a comprehensive literature review of CSR in the tourism and hospitality sector, presenting five sections that explore what CSR means to different stakeholder groups. We first review the meaning of CSR as stakeholder accountability in its broadest sense. We then consider what CSR means for the “elephant in the room” that guides all CSR activities: the shareholder (see Friedman, Citation1970 for more on the relationship between shareholders and social responsibility). We continue by examining how CSR is enacted by organisational management in order to deliver on the organisation’s strategy, as well as how this is mediated by the organisation’s culture. This is followed by what CSR means to employees and how it is associated with human resources management, before moving on to the role of consumers and how the organisation deploys persuasive marketing and communication efforts. Discussion of the role of communities and ecosystems as stakeholders remains an under-represented component of the research on stakeholders. Readers may observe the absence of discussion related to governments and NGOs in this paper. This is because the tourism literature has paid little attention to their potential role in nudging tourism firms to be more responsible.

Overview of the literature

Society: stakeholder accountability

The real meaning of the S in CSR is that companies have a responsibility towards ensuring that all aspects of the business have a positive impact on our society. Currently, it appears that companies are making superficial changes to appear to be more sustainable, perhaps because stakeholders are not sufficiently well-organised to demand change (Coles, Fenclova, & Dinan, Citation2011; Dodds & Kuehnel, Citation2010; Weaver, Citation2014). Industry surveys provide some explanations for the relatively poor quality of CSR engagement. Despite having a good understanding of the term CSR, members of the Travel Industry Association of America (TIA) implement primarily environmental rather than sociocultural CSR actions, mostly for reputational reasons (Sheldon & Park, Citation2011). UK airlines use self-serving language to justify their actions (Burns & Cowlishaw, Citation2014), and UK conference venues undertake eco-savings or tokenistic CSR activities (Whitfield & Dioko, Citation2012).

It is clear that increasing the accountability of sustainability practices improves CSR engagement. Merwe and Wocke (Citation2007) reported that the membership of South African “responsible tourism” associations increased the practice and communication of CSR actions in the region, although arguably not to the extent that may have been desired. In Malaysia, we find both endogenous and exogenous antecedents for primarily social CSR actions in local hotel chains (Abaeian, Yeoh, & Khong, Citation2014). Even those companies that believe that sustainability is important find that dedicating time to it, and the cost of acting more responsibly, both make companies less competitive (Frey & George, Citation2010). These findings suggest that improving CSR practices, especially those related to sustainability, will require stakeholders to become more effective at lobbying for industry-wide acknowledgement of the importance of social and environmental responsibilities towards society.

Ideally, CSR measurement scales would be grounded in a detailed understanding of what stakeholders expect from each business in relation to the context in which it operates, however the reality is rarely quite as straightforward (Martínez, Pérez, & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2013). For example, Macao’s gambling industry engages only symbolically with CSR activities, emphasising the economic contribution the industry makes to the destination while turning a blind eye to the social issues of gambling addiction, and environmental impacts (Leung & Snell, Citation2017). Stakeholders themselves often see CSR as secondary to business as usual. A study about the CSR of a Taiwanese airport, for instance, found that safety and security, service quality, and corporate governance were prioritised by stakeholders over criteria related to either environmental management, or employee and work environment management (Chang & Yeh, Citation2016). In general, consumers believe that long-term sustainable economic practices are more central to a business’ CSR programme than its social and environmental dimensions (Martínez et al., Citation2013).

CSR reports are an excellent tool for gauging what companies believe their responsibility is towards society, as well as how they act on perceived obligations. Only 18 out of the 50 largest hotel groups in the world, and 12 out of 80 cruise companies, provide CSR reports that contain environmental, social, and economic information (Bonilla-Priego, Font, & Pacheco, Citation2014; Guix, Bonilla-Priego, & Font, Citation2017). The literature indicates a lack of consistency in CSR accounting methodologies, the scope of reporting, and the activities undertaken (Bonilla-Priego et al., Citation2014; Burns & Cowlishaw, Citation2014; de Grosbois, Citation2012; Holcomb, Upchurch, & Okumus, Citation2007). This results in a significant gap between stated CSR commitments, actual practices, and the quality of data shared with stakeholders (de Grosbois, Citation2012; Font, Walmsley, Cogotti, McCombes, & Häusler, Citation2012). Moreover, there are gaps in the information provided to employees, suppliers and shareholders in relation to, for example, information transparency, labour rights, human rights, and sustainability in supplier relations (Perez & Rodríguez Del Bosque, Citation2014). All of these gaps exist because CSR reports tend to reflect the priorities of the companies that prepare them, and not the expectations placed on those companies by their stakeholders (Font, Guix, & Bonilla-Priego, Citation2016).

Two articles in this special issue contribute to the stakeholder accountability literature. Ringham and Miles (Citation2018) study the “boundary” of activities stakeholders may expect a company to report on, in other words, the perceived limits of an organisation’s accountability. This includes, for example, the choices made about the type of impacts considered, as well as the scope of the organisation (Ringham & Miles, Citation2018). Previous research has shown that hotel groups choose not to include franchised hotels in the scope of their CSR activities and subsequent reports, due to having lower management control over them, despite stakeholders’ expectations that CSR reporting would include all establishments under a given brand (Melissen, van Ginneken, & Wood, Citation2016). Ringham and Miles (Citation2018) find that the airline industry defines its CSR responsibility rather narrowly and conveniently, without taking into account stakeholder expectations. They also find that the companies claiming to have a stricter level of CSR compliance set themselves a narrower organisational scope. The second article in this issue to explore stakeholder accountability is Guix et al. (Citation2017), which considers the opacity of the reporting of the processes used by companies. The authors focus on hotel groups to account for the stakeholders that are identified and engaged as relevant to determining CSR programmes, as well as the scant information available relating to how CSR reports respond to stakeholder expectations.

Shareholders: the quest for corporate financial performance

Companies have defined CSR as secondary to the business growth imperative (Jones, Hillier, & Comfort, Citation2016). In response, a multitude of studies have attempted to identify which aspects of positive or negative CSR management and performance have an impact, or mediating effect, on measures of short- and long-term corporate financial performance (CFP) (see for example Inoue & Lee, Citation2011; Kang, Lee, & Hug, Citation2010; Leonidou, Leonidou, Fotiadis, & Zeriti, Citation2012; Lee & Heo, Citation2009; Lee & Park, Citation2009; Pereira-Moliner, Claver-Cortés, Molina-Azorín, & Taríí, Citation2012; Pereira-Moliner et al., Citation2015; S.-B. Kim & D.-Y. Kim, Citation2014; Singal, Citation2014). In fact, this subject has been the most researched aspect of CSR in the tourism and hospitality industries (Farrington et al., Citation2017), yet the results have been inconclusive (Kang et al., Citation2010; Pereira-Moliner et al., Citation2015).

Part of the complexity of studying the CSR–corporate financial performance (CSR-CFP) relationship is that CSR is not a homogeneous construct. Hence, several studies have considered CSR as an aggregate variable (Nicolau, Citation2008) and have therefore investigated its individual components, such as environmental practices (Pereira-Moliner et al., Citation2012) or corporate charitable giving (Chen & Lin, Citation2015). Others have studied multiple CSR elements in parallel, such as employee relations, product quality, community relations, environmental, and diversity issues (Inoue & Lee, Citation2011). The relative impacts, or efficacy, of CSR measures also depend on the company and its contextual variables. For example, CSR appears to influence CFP differently depending on a firm’s size (Youn, Hua, & Lee, Citation2015), managerial ownership (Paek, Xiao, Lee, & Song, Citation2013), top management gender (Quintana-García, Marchante-Lara, & Benavides-Chicón, Citation2017), familial control (Singal, Citation2014), and geographical diversification (Park, Song, & Lee, Citation2017). Further, we find that during recessionary periods, non-operations related CSR practices cause a substantial decline in firm value, while operations-related CSR have a positive impact (Lee, Singal, & Kang, Citation2013). As the literature has evolved, more recent studies have provided empirical evidence to explain the interrelationships between a firm’s CSR initiatives, stakeholders groups, and financial performance. Theodoulidis, Diaz, Crotto, and Rancati (Citation2017) conducted one of the most comprehensive accounts of this literature to justify the disaggregation of CSR, and to relate CSR to concerns from specific stakeholder groups. They consider how CRS relates to the use of strategic and intrinsic stakeholder models as explanatory frameworks, as well as to the use of both short- and long-term corporate financial performance data, in order to test their model in multiple subsectors of tourism. What all these studies have in common is the use of mainstream management, economics literature, and quantitative methods to explain patterns in CSR–CFP.

Three articles in this special issue contribute to the topic of CSR from a shareholder perspective (Horng, Hsu, & Tsai, Citation2017; Jung, Kim, Kang, & Kim, Citation2018; Wang, Xu, & Li, Citation2018). Horng et al. (Citation2017) develop a multiple attribute decision-making model to determine the causal relations and the weight of the attributes of CSR. They also present an influential network relations map to aid decision-making to deploy resources and reach optimal CSR performance, based on experts’ understandings of the impacts and influences between items. Next, Jung et al. (Citation2018) theorise that as part of a firm’s internationalisation strategy, CSR activities have the opportunity to contribute to image formation and adaptation to local markets, hence working to reduce a firm’s systematic risk. Their results show that while socially responsible CSR actions did not have a moderating effect between internationalisation and systematic risk, socially-irresponsible activities did: to reduce systematic risk from internationalisation, firms must therefore address any activities that are perceived as irresponsible, in relation to consumers’ health, environment, and social issues. Wang et al. (Citation2018) found that tourist attractions engage more in corporate philanthropy than do other tourism firms. In this context, philanthropy is used to redress economic imbalance, unsustainable use of resources due to fierce competition and/or low access to education. For tourist attractions, philanthropy therefore becomes a tool for enhancing legitimacy, smoothing community relations, and improving corporate image in locations where there is a high power imbalance between large tourist attractions, the local community, and the tourism businesses that depend on the attraction.

Management: CSR, strategy and organisational culture

A third strand of the literature studies how managers negotiate trade-offs in implementing CSR (Hahn, Figge, Pinkse, & Preuss, Citation2010). Organisations will naturally seek the most cost-effective way of achieving their CSR objectives, and therefore the actions they implement will vary according to whether their motivations to engage in CSR are based on profit, legitimation or altruism (Font, Garay, & Jones, Citation2016b). We know that companies tend to implement actions that will lead to efficiency gains that can be quantified, while they pay less attention to the more ambiguous socio-economic potential gains (Font & Harris, Citation2004; Jones, Hillier, & Comfort, Citation2014; Kasim, Gursoy, Okumus, & Wong, Citation2014; Levy & Park, Citation2011).

There is an understanding that the CSR–CFP relationship looks like an inverted U curve, whereby increases in a firm’s social responsibility lead to improved financial performance; however, there also comes a point when further increases in responsibility are actually detrimental to a firm’s overall financial performance. The optimal balance between CSR and CFP is something that few articles address (Chen & Lin, Citation2015). There are reasons to believe that businesses with more altruistic motivations worry less about the return on investment per se: for example, Garay and Font (Citation2012) found that businesses with a higher CSR performance tend to have a higher level of satisfaction with their current CFP, even though it is actually similar to that of their competitors. Hence, we need to understand how CSR is enacted according to organisational culture and values. Studies have shown that small firms are more likely to take CSR actions for altruistic and social capital reasons, rather than commercial reasons, when compared to large firms; their actions will also be more ad hoc and less strategic (Font, Garay, & Jones, Citation2016a; Garay & Font, Citation2012). Global tourism firms, on the other hand, struggle to operationalise their centralised CSR strategies in a way that is sensitive to different local contexts (Smith & Ong, Citation2015). Therefore, they tend to centralise the environmental, cost efficiency driven indicators, while allowing each individual hotel to have social programmes that are typically not quantified beyond philanthropic donations. The literature shows that tourism firms tend to get the most benefits (financial or otherwise) from CSR actions that are strategic and genuine, and less so when these are tactical and reactive (Prud’homme & Raymond, Citation2013). There is evidence that the joint introduction of total quality management and CSR activities provides benefits to stakeholders, which in turn positively affects hotel performance (Benavides-Velasco, Quintana-García, & Marchante-Lara, Citation2014). The need for strategic approaches is also evident in sustainable supply chain management, which requires stakeholder collaborations and long-term strategic partnerships to deliver operational improvements (Xu & Gursoy, Citation2015; Zhang, Joglekar, & Verma, Citation2012).

Organisational priorities explain why chain hotels are more likely to implement low cost CSR practices compared to independent hotels (Rahman, Reynolds, & Svaren, Citation2012). There is a tendency to internalise CSR activities that can be seen as a core part of the business (such as those leading to operational savings and aspects of personnel management), while outsourcing CSR actions that are not part of the core business (such as those providing community and broader environmental benefits) (Smith & Ong, Citation2015). This is because partnering with local stakeholders allows tourism businesses to cost-effectively access knowhow and externalise fixed costs and responsibilities, while also gaining visibility that legitimises their businesses. It is a shame that there are few published examples of how individual organisations go about introducing CSR programmes that are appropriate to the organisational culture of the organisation, and even less information about the unintended consequences of well-meaning CSR programmes (Bohdanowicz & Zientara, Citation2008).

This understanding of CSR organisational climate and the relation between organisational and personal CSR values is key to understanding CSR successes and challenges. An organisation’s culture towards CSR moderates between personal CSR norms and behaviour between firms, while personal CSR values moderate the variations in behaviour within firms (Chou, Citation2014; El Dief & Font, Citation2011; Wells, Smith, Taheri, Manika, & McCowlen, Citation2016). Lin, Yu, and Chang (Citation2018), for instance, found that young companies were more active in CSR than established companies, even when the latter employed younger and more educated managers who personally acknowledged having positive attitudes towards sustainability. Chou (Citation2014, p. 436) similarly determined that “personal environmental norms explain within-hotel variance, but green organisational climates explain between-hotel variance and moderate the effect of personal environmental norms on employees’ environmental behaviour”. Further, Lin et al. (Citation2018) discussed how managers’ altruistic attitudes, as well as an appreciation of the benefits to the company, predicted CSR practices in Taiwanese tour operators, while their choices of CSR practices were also informed by their understanding of subjective norms and their perceptions of their own abilities to succeed. Finally, Lee, Lee, and Li (Citation2012) found that both the economic and philanthropic dimensions of CSR positively influence an employee’s trust in their organisation, however only the ethical dimensions of CSR have a positive effect on an employees’ job satisfaction; the legal dimension has no influence. What these articles have in common is showing that organisations with a genuine belief in sustainability create organisational climates that empower staff to take ownership for relevant CSR actions.

Within this special issue, there are three contributions to the literature on negotiating CSR actions within an organisational strategy. Kallmuenzer, Nikolakis, Peters, and Zanon (Citation2017) use socio-emotional wealth and random-utility theory to explain why, after meeting financial requirements, Austrian rural tourism family firms gain greater utility from ecological and social outcomes than they do from higher profit outcomes. Their contribution is also methodological as they are the first study to use conjoint analysis, a choice-method survey, to study CSR pay-offs as well as the trade-offs between different CSR attributes. Buijtendijk, Blom, and Vermeer (Citation2018) report on the industry co-construction of sustainability innovations and the choices resulting from environmental and social trade-offs that arise due to these innovations. They use Actor-Network Theory as an analytical tool to study how stakeholders engage with each other in order to develop sustainable tourism innovations and to negotiate the outcomes and implications of such innovations. A further contribution to the literature on CSR, strategy, and organisational culture comes from Vila, Afsordegan, Agell, Sánchez, and Costa (Citation2018), who put forward a fuzzy Delphi technique using linguistic scales to develop a consensus on sustainable tourism indicators in relation to water allocation. This is the only article in this special issue that considers destination-wide negotiations of responsibility towards the appropriate management of resources for tourism, residents, and nature.

Employees: CSR and human resources management

A strategy that creates the appropriate organisational culture to nurture CSR must enable the organisation’s employees to feel that they identify with the organisation’s values, and to act on their own pro-sustainability personal values (Wells et al., Citation2016). The role that management staff and personnel play in the implementation of CSR programmes is gaining attention in the tourism and hospitality literature (Bohdanowicz, Zientara, & Novotna, Citation2011; Chou, Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2012; Lynes & Andrachuk, Citation2008). Managers’ leadership styles, and their understanding of CSR, affect how they encourage their employees to engage in CSR activities (Mackenzie & Peters, Citation2014) as a result of their influence on the organisation’s identity and commitment (Fu, Ye, & Law, Citation2014). Tsai, Tsang, and Cheng (Citation2012), for example, found that both employees and managers in Hong Kong have a low level of environmental awareness and (potentially as a consequence) a high level of satisfaction with their employer’s current CSR effectiveness. Gaining employee affective emotional commitment, innovation, and customer loyalty impact positively on the relationship between CSR and CFP (Wang, Citation2014).

A social marketing experiment that attempted to change employee behaviour showed the need for managers to plan CSR strategies that increase staff knowledge and awareness, but pay equal attention to staff motivation, self-efficacy and information adequacy (Wells, Manika, Gregory-Smith, Taheri, & McCowlen, Citation2015). Employee awareness of, and engagement with, CSR activities is directly related to job satisfaction, engagement, and voice behaviour, and negatively related to job exhaustion (Raub & Blunschi, Citation2014). It has been shown to stimulate work engagement, career satisfaction, and voice behaviour (Ilkhanizadeh & Karatepe, Citation2017), to positively influence organisational identification (Park & E. Levy, Citation2014), and to enhance quality of working life, affective commitment, and organisational citizenship behaviour (Kim, Rhou, Uysal, & Kwon, Citation2017). However, despite positive attitudes towards CSR, small and large firms alike, in developed and developing countries, report similar barriers to acting on these attitudes, including lack of time, money, support, and customer demand (Frey & George, Citation2010; Garay & Font, Citation2013). At hotel level, staff usually have CSR responsibilities as an addition to their main job, and this determines the way that CSR is interpreted in the organisation, with a preference for engineering approaches to efficient management of facilities (Geerts, Citation2014). Hence, the importance of CSR task significance, which is the degree to which employees believe that their job has a positive impact on the lives of others (Raub & Blunschi, Citation2014).

This special issue includes three contributions to the study of CSR and employee behaviour, also drawing connections to the impact of organisational culture. Zientara and Zamojska (Citation2016) present a study of how green organisational climate affects organisational citizenship behaviour. They develop a multilevel approach to studying employee roles in green organisational behaviour, considering the role of individuals within departments, within organisations, and within organisational contexts. This nested understanding of behaviour allows them to better understand the ability of personal, organisational, and contextual factors to influence organisational citizenship behaviour. Similarly, Martínez García de Leaniz, Herrero Crespo, and Gómez López (Citation2017) find multiple relationships between organisational green practices, green image, environmental consciousness, and the behavioural intentions of customers. Finally, Tuan (Citation2017) shows that there are interactive, multidirectional, and amplifying influences between organisational CSR, employee pro-environmental citizenship, and tourists’ pro-environmental citizenship, which he explains using social identity theory. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that organisations make better decisions when they understand CSR as being central to their DNA rather than merely as a legitimisation tool (Husted & Allen, Citation2007). They share methods to determine the fit between corporate strategy and CSR choices (Tsai, Hsu, Chen, Lin, & Chen, Citation2010). They also show that not only are CSR actions more successfully implemented when they are well embedded in organisational culture, but enacting this culture through CSR helps to further consolidate the organisational culture (Martínez, Pérez, & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2014).

Consumers: marketing and communication

It is essential to engage both employees and customers in order to co-create meaningful sustainability experiences (Zhang et al., Citation2012), remembering that both stakeholder groups are motivated by self-interest (Wong & Gao, Citation2014). Guests, however, are rarely engaged in the design of CSR strategies (Moscardo & Hughes, Citation2018). Tourists’ own interpretations of CSR vary considerably depending on their inner versus outer directed goals and the role that responsibility has as part of their self-identity (Caruana, Glozer, Crane, & McCabe, Citation2014). Also, we know that consumers are considerably more environmentally friendly at home than in hotel settings, and that their reasons for pro-environmental behaviour are normative at home, but hedonic on holiday (Miao & Wei, Citation2013). Hedonism may explain why positive (but not negative) emotions on environmentally responsible behaviour have a mediating role between destination social responsibility and environmentally responsible behaviour (Su & Swanson, Citation2017). Baker, Davis, and Weaver (Citation2014) found that consumers boycott hotels’ environmental actions that are perceived to lead to inconvenience, cost cutting, and loss of luxury. Altruistic CSR communications to consumers that focus on preventing something negative from happening work well, whereas both altruistic and strategic CSR communications that promote a positive outcome are received similarly well by consumers (Kim, Kim, & Mattila, Citation2017).

While customers expect to receive a benefit for themselves from engaging in CSR activities (Wong & Gao, Citation2014), they are also sceptical about environmental claims for which they recognise an ulterior motive of the hotel, affecting their intention to support the hotel’s CSR programme and to revisit the establishment (Rahman, Park, & Chi, Citation2015). Corporate values impact the consumer’s engagement, as well as consumer expectations of different business models: CSR has a positive synergistic effect with service quality for full service airlines and a negative effect for low cost airlines (Seo, Moon, & Lee, Citation2015). While CSR mostly influences the affective dimension of brand image, the functional image mostly influences brand loyalty (Martínez, Pérez, & del Bosque, Citation2014). Trust, customer identification with the company, and satisfaction are therefore mediators between CSR and customer loyalty (Martínez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2013).

Often larger firms initially engage in CSR to manage their image, brand, and corporate systematic risk (Jung et al., Citation2016; Levy & Park, Citation2011; M. Kim & Y. Kim, Citation2014; Miller, Citation2001; Tsai et al., Citation2010), subsequently realising the complexities of communicating their CSR efforts, exemplified in both the use of social marketing (Truong & Hall, Citation2017) and certification (Geerts, Citation2014). This results in small businesses “greenhushing” – that is, deliberately under-communicating their sustainability actions (Font, Elgammal, & Lamond, Citation2017). However, recent evidence shows that the benefits achieved from engaging in CSR are more than reversed if the CSR activity is discontinued (Li, Fang, & Huan, Citation2017). Therefore, communication of CSR actions needs to be more strategic and less ad hoc, and must consider the likely consumer responses, in relation to both what is communicated and how (Font & McCabe, Citation2017; Villarino & Font, Citation2015; Zhang, Citation2014). A good recent review on sustainability communication in tourism was written by Tölkes (Citation2018).

When sustainability benefits and responsibility actions are persuasively communicated, they can positively affect consumer satisfaction. In return, this raises the likelihood to repeat business (Jarvis, Stoeckl, & Liu, Citation2016), contributes to service recovery (Albus & Ro, Citation2017; Siu, Zhang, & Kwan, Citation2014), increases customer loyalty (Martínez García de Leaniz & Rodríguez Del Bosque Rodríguez, Citation2015; Pérez & Rodriguez del Bosque, Citation2015), and creates positive word-of-mouth and resistance to negative information (Xie, Bagozzi, & Gr⊘nhaug, Citation2015). Through effective communication, CSR positively affects perceptions of corporate reputation and customer satisfaction, and positively impacts customer commitment and behaviour, particularly amongst people with a higher income (Su, Pan, & Chen, Citation2017). Consumer motivations towards responsible tourism, together with their perceptions of both the destination visited and the brand of the operator used, also shape their attitudes and loyalties towards the operator chosen (Mody, Day, Sydnor, Lehto, & Jafféé, Citation2017). Construal level theory suggests that consumers respond best to messages that are congruent with: (i) what sustainability means to them (Line, Hanks, & Zhang, Citation2016), (ii) their processing fluency and psychological distance (Zhang, Citation2014), and (iii) the core purpose of that business (Kim & Ham, Citation2016).

In summary, there are very good reasons to further research how to better market and communicate CSR. For example, previous studies have demonstrated that image is an important motivator for firms to adopt CSR practices, and there is evidence to support the mediating role of trust between image and customer loyalty. In this special issue, Palacios-Florencio, García del Junco, Castellanos-Verdugo, and Rosa-Díaz (Citation2018) expand on the theoretical and empirical evidence regarding how customer trust acts as a mediator between CSR and image and loyalty, initiated by Martínez and Rodríguez del Bosque (Citation2013). This research shows that customers are more inclined to believe that responsible companies operate honestly in their activities and are more willing to enter into relationships with firms that develop socially responsible initiatives. Furthermore, Moscardo and Hughes (Citation2018) outline 10 strategies to close the consumer’s attitude–behaviour gap towards CSR using literature from tourist interpretation, social marketing and sustainability marketing. Their paper offers valuable recommendations for businesses, and useful guidance on avenues of further research. These studies reinforce the need for customers to not only understand what actions firms are taking with respect to CSR but more importantly to both believe and trust that these actions are legitimate.

Conclusions

Through the application of a stakeholder lens, this paper explores how CSR has developed within the tourism and hospitality literature, paying particular attention to current gaps in the literature and highlighting how the papers presented in this special issue offer novel and timely contributions to this field of study. Specifically, five key contributions have been highlighted. First, this issue explores CSR in terms of stakeholder accountability by considering both the scope of reporting and the quality of stakeholder engagement (Guix et al., Citation2017; Ringham & Miles, Citation2018). Next, it analyses how CSR contributes to shareholder accountability (i.e. as financial performance) by developing a multiple attribute decision-making model to deploy CSR resources (Horng et al., Citation2017), analysing how CSR contributes to the management of systematic risk as part of an internationalisation strategy (Jung et al., Citation2018); and showing how philanthropy is used as a legitimisation tool (Wang et al., Citation2018). This special issue also reviews how managers negotiate CSR priorities within their organisational strategy by accounting for the utility gained by family firms from ecological and social outcomes in comparison with profit outcomes (Kallmuenzer et al., Citation2017), analysing the trade-offs of co-constructing a sustainability innovation (Buijtendijk et al., Citation2018) and weighting factors in water planning (Vila et al., Citation2018). Fourth, it reviews how employees are central to the delivery of CSR actions by exploring how green organisational culture affects organisational citizenship behaviour (Zientara & Zamojska, Citation2016), how organisational green practices impact an organisation’s image and its customers’ environmental consciousness and behavioural intentions (Martínez García de Leaniz et al., Citation2017); and how organisational CSR affects employee pro-environmental citizenship and tourists’ pro-environmental citizenship (Tuan, Citation2017). Finally, this special issue reviews the role of consumers in CSR with 10 strategies to close the consumer’s attitude–behaviour gap (Moscardo & Hughes, Citation2018) and an account of how customers’ trust is a mediator between CSR, image and loyalty (Palacios-Florencio et al., Citation2018).

This emerging research on CSR in the context of tourism and hospitality is pushing past the boundaries of early approaches to corporate sustainability by providing empirical evidence to support the importance of integrating a range of stakeholder perspectives and needs throughout the planning, implementation, and evaluation of CSR initiatives. We have created to depict the various internal and external stakeholders that should are (or should be) involved in CSR at the level of the firm.

In the tourism and hospitality literature, internal stakeholders such as shareholders, employees, and management and as well as external stakeholders such as consumers are the main focus of current and past on this topic. Other external stakeholders such as communities and ecosystems are increasingly being addressed in the literature but more research is needed. To date, the role of suppliers, governments, and NGOs have been largely overlooked. We encourage future research to focus on the role of some of these under-researched stakeholders. While tourism and hospitality may not be subject to the same pressures from these stakeholders as other industries, there remain valuable opportunities to engage these stakeholders in the journey toward corporate sustainability and responsibility.

School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK

Jennifer Lynes

School of Environment, Enterprise and Development, University of Waterloo,

Waterloo, ON, Canada

[email protected]

Notes on contributors

Dr. Xavier Font is professor of sustainability marketing at the University of Surrey, and head of impact at Travindy (www.travindy.com), a web-based organisation helping the travel industry to understand the issues around tourism and sustainability and integrate them into their work. He has run over 100 training courses on sustainability marketing to over 2500 delegates, and consulted for UNWTO, UNEP, EC, IFC, Rainforest Alliance and numerous governments and businesses. His research focuses on understanding reasons for pro-sustainability behaviour and market-based mechanisms to encourage sustainable production and consumption.

Dr. Jennifer Lynes is associate professor and director of Canada’s leading undergraduate program in environment and business at the University of Waterloo. Her research focuses on the intersection of sustainability and marketing, particularly with respect to the live music industry. Her earlier research looked at corporate motivations for environmental commitment in the airline industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aragon-Correa, J., Martin-Tapia, I., & de la Torre-Ruiz, J. (2015). Sustainability issues and hospitality and tourism firms’ strategies: analytical review and future directions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27, 498–552. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0564.

- Abaeian, V., Yeoh, K. K., & Khong, K. W. (2014). An exploration of CSR initiatives undertaken by Malaysian hotels: Underlying motivations from a managerial perspective. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 144, 423–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.312.

- Albus, H., & Ro, H. (2017). Corporate social responsibility: The effect of green practices in a service recovery. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 41, 41–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013515915.

- Baker, M. A., Davis, E. A., & Weaver, P. A. (2014). Eco-friendly attitudes, barriers to participation, and differences in behavior at green hotels. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55, 89–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513504483.

- Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Marchante-Lara, M. (2014). Total quality management, corporate social responsibility and performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41, 77–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.003.

- Bohdanowicz, P., & Zientara, P. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in hospitality: Issues and implications. A case study of Scandic. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8, 271–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250802504814.

- Bohdanowicz, P., Zientara, P., & Novotna, E. (2011). International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton's we care! programme (Europe, 2006–2008). Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19, 797–816. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2010.549566.

- Bonilla-Priego, M. J., Font, X., & Pacheco, R. (2014). Corporate sustainability reporting index and baseline data for the cruise industry Tourism Management, 44, 149–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.004.

- Buijtendijk, H., Blom, J., & Vermeer, J. (2018). Eco-innovation for sustainable tourism transitions as a process of collaborative co-production: The case of a carbon management calculator for the Dutch travel industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1433184.

- Burns, P. M., & Cowlishaw, C. (2014). Climate change discourses: How UK airlines communicate their case to the public. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(5), 750–767. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.884101.

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility. Business & Society, 38, 268–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303.

- Caruana, R., Glozer, S., Crane, A., & McCabe, S. (2014). Tourists’ accounts of responsible tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 46, 115–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.03.006.

- Chang, Y.-H., & Yeh, C.-H. (2016). Managing corporate social responsibility strategies of airports: The case of Taiwan’s Taoyuan International Airport Corporation. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 92, 338–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.06.015.

- Chen, M.-H., & Lin, C.-P. (2015). The impact of corporate charitable giving on hospitality firm performance: Doing well by doing good? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 25–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.02.002.

- Chou, C.-J. (2014). Hotels' environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tourism Management, 40, 436–446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.08.001.

- Coles, T., Fenclova, E., & Dinan, C. (2011). Responsibilities, recession and the tourism sector: Perspectives on CSR among low-fares airlines during the economic downturn in the UK. Current Issues in Tourism, 14, 519–536. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.544719.

- Coles, T., Fenclova, E., & Dinan, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibility reporting among European low-fares airlines: challenges for the examination and development of sustainable mobilities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22, 69–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.790391.

- Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.132.

- De Groot, J. I., & Steg, L. (2008). Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior how to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40, 330–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506297831.

- de Grosbois, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31, 896–905. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.008.

- Dodds, R., & Kuehnel, J. (2010). CSR among Canadian mass tour operators: good awareness but little action. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22, 221–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111011018205El.

- El Dief, M., & Font, X. (2011). Determinants of environmental management in the Red Sea Hotels: Personal and organizational values and contextual variables. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 36, 115–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010388657.

- Farrington, T., Curran, R., Gori, K., O’Gorman, K. D., & Queenan, C. J. (2017). Corporate social responsibility: Reviewed, rated, revised. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29, 30–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010388657.

- Font, X., Elgammal, I., & Lamond, I. (2017). Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25, 1007–1023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1158829.

- Font, X., Garay, L., & Jones, S. (2016a). A social cognitive theory of sustainability empathy. Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 65–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.02.004.

- Font, X., Garay, L., & Jones, S. (2016b). Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1439–1448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.071s.

- Font, X., Guix, M., & Bonilla-Priego, M. J. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tourism Management, 53, 175–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.007.

- Font, X., & Harris, C. (2004). Rethinking labels: From green to sustainable. Annals of Tourism Research, 31, 986–1007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.001.

- Font, X., & McCabe, S. (2017). Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25, 869–883. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1301721.

- Font, X., Walmsley, A., Cogotti, S., McCombes, L., & Häusler, N. (2012). Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure–performance gap. Tourism Management, 33, 1544–1553. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.012.

- Frey, N., & George, R. (2010). Responsible tourism management: The missing link between business owners' attitudes and behaviour in the Cape Town tourism industry. Tourism Management, 31, 621–628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.06.017.

- Fu, H., Ye, B. H., & Law, R. (2014). You do well and I do well? The behavioral consequences of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 40, 62–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.03.004.

- Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits, New York Times, New York Times Archives, 17.

- Garay, L., & Font, X. (2012). Doing good to do well? Corporate social responsibility reasons, practices and impacts in small and medium accommodation enterprises. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31, 328–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.013.

- Garay, L., & Font, X. (2013). Corporate social responsibility in tourism small and medium enterprises. Evidence from Europe and Latin America. Tourism Management Perspectives, 7, 38–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2013.03.002.

- Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 51–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039399.90587.34.

- Geerts, W. (2014). Environmental certification schemes: Hotel managers’ views and perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 39, 87–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.02.007.

- Guix, M., Bonilla-Priego, M. J., & Font, X. (2017). The process of sustainability reporting in international hotel groups: An analysis of stakeholder inclusiveness, materiality and responsiveness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.09662017.01410164

- Hahn, T., Figge, F., Pinkse, J., & Preuss, L. (2010). Trade‐offs in corporate sustainability: You can't have your cake and eat it. Business Strategy and The Environment, 19, 217–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.674.

- Holcomb, J. L., Upchurch, R. S., & Okumus, F. (2007). Corporate social responsibility: What are top hotel companies reporting? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19, 461–475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110710775129.

- Horng, J.-S., Hsu, H., & Tsai, C.-Y. (2017). An assessment model of corporate social responsibility practice in the tourism industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1388384.

- Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2007). Strategic corporate social responsibility and value creation among large firms: Lessons from the Spanish experience. Long Range Planning, 40, 594–610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2007.07.001.

- Ilkhanizadeh, S., & Karatepe, O. M. (2017). An examination of the consequences of corporate social responsibility in the airline industry: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and voice behavior. Journal of Air Transport Management, 59, 8–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2016.11.002.

- Inoue, Y., & Lee, S. (2011). Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tourism Management, 32, 790–804. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.019.

- Jarvis, D., Stoeckl, N., & Liu, H.-B. (2016). The impact of economic, social and environmental factors on trip satisfaction and the likelihood of visitors returning. Tourism Management, 52, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.003.

- Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2014). Sustainability in the global hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26, 5–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2012-0180.

- Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016). Sustainability in the hospitality industry: Some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28, 36–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0572.

- Jung, S., Jung, S., Lee, S., Lee, S., Dalbor, M., & Dalbor, M. (2016). The negative synergistic effect of internationalization and corporate social responsibility on US restaurant firms’ value performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28, 1759–1777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2014-0361.

- Jung, S., Kim, J. H., Kang, K. H., & Kim, B. (2018). Internationalization and corporate social responsibility in the restaurant industry: Risk perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1421201.

- Kallmuenzer, A., Nikolakis, W., Peters, M., & Zanon, J. (2017). Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: Exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1374962.

- Kang, K. H., Lee, S., & Hug, C. (2010). Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29, 72–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.05.006.

- Kasim, A., Gursoy, D., Okumus, F., & Wong, A. (2014). The importance of water management in hotels: A framework for sustainability through innovation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22, 1090–1107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.873444.

- Kim, E., & Ham, S. (2016). Restaurants’ disclosure of nutritional information as a corporate social responsibility initiative: Customers’ attitudinal and behavioral responses. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55, 96–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.02.002.

- Kim, M., & Kim, Y. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and shareholder value of restaurant firms. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 40, 120–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.03.006.

- Kim, S.-B., & Kim, D.-Y. (2014). The effects of message framing and source credibility on green messages in hotels. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55, 64–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513503400.

- Kim, Y., Kim, M., & Mattila, A. S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and equity-holder risk in the hospitality industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58, 81–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965516649052.

- Kim, H. L., Rhou, Y., Uysal, M., & Kwon, N. (2017). An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61, 26–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.10.011.

- Lee, S., & Heo, C. Y. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and customer satisfaction among US publicly traded hotels and restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28, 635–637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.02.007.

- Lee, Y.-K., Lee, K. H., & Li, D.-x. (2012). The impact of CSR on relationship quality and relationship outcomes: A perspective of service employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31, 745–756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.011.

- Lee, S., & Park, S. Y. (2009). Do socially responsible activities help hotels and casinos achieve their financial goals? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28, 105–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.003.

- Lee, S., Singal, M., & Kang, K. H. (2013). The corporate social responsibility – Financial performance link in the US restaurant industry: Do economic conditions matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32, 2–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.03.007.

- Leonidou, L. C., Leonidou, C. N., Fotiadis, T. A., & Zeriti, A. (2012). Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tourism Management, 35, 94–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.003.

- Leung, T. C. H., & Snell, R. S. (2017). Attraction or distraction? Corporate social responsibility in Macao’s gambling industry. Journal of business ethics, 145, 637–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2890-z.

- Levy, S. E., & Park, S.-Y. (2011). An analysis of CSR activities in the lodging industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 18, 147–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.18.1.147.

- Li, Y., Fang, S., & Huan, T.-C. T. (2017). Consumer response to discontinuation of corporate social responsibility activities of hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 41–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.04.001.

- Lin, L.-P. L., Yu, C.-Y., & Chang, F.-C. (2018). Determinants of CSER practices for reducing greenhouse gas emissions: From the perspectives of administrative managers in tour operators. Tourism Management, 64, 1–12.

- Line, N. D., Hanks, L., & Zhang, L. (2016). Sustainability communication: The effect of message construals on consumers’ attitudes towards green restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57, 143–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.07.001.

- Lynes, J. K., & Andrachuk, M. (2008). Motivations for corporate social and environmental responsibility: A case study of Scandinavian Airlines. Journal of International management, 14, 377–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2007.09.004.

- Mackenzie, M., & Peters, M. (2014). Hospitality managers' perception of corporate social responsibility: An explorative study. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19, 257–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2012.742915.

- Martínez García de Leaniz, P., Herrero Crespo, Á., & Gómez López, R. (2017). Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1349775.

- Martínez García de Leaniz, P., & Rodríguez Del Bosque Rodríguez, I. (2015). Exploring the antecedents of hotel customer loyalty: A social identity perspective. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 24(1), 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2014.891961.

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & del Bosque, I. R. (2014). CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 27, 267–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-12-2013-0190.

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2013). Measuring corporate social responsibility in tourism: Development and validation of an efficient measurement scale in the hospitality industry. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30, 365–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.784154.

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2014). Exploring the role of CSR in the organizational identity of hospitality companies: A case from the Spanish tourism industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 47–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1857-1.

- Martínez, P., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2013). CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 89–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.05.009.

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26, 117–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4011987.

- Melissen, F., van Ginneken, R., & Wood, R. C. (2016). Sustainability challenges and opportunities arising from the owner–operator split in hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 35–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.005.

- Merwe, M., & Wocke, A. (2007). An investigation into responsible tourism practices in the South African hotel industry. South African Journal of Business Management, 38(2), 1–15.

- Miao, L., & Wei, W. (2013). Consumers’ pro-environmental behavior and the underlying motivations: A comparison between household and hotel settings. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32, 102–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.04.008.

- Miller, G. (2001). Corporate responsibility in the UK tourism industry. Tourism Management, 22, 589–598. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00034-6.

- Mody, M., Day, J., Sydnor, S., Lehto, X., & Jaffé, W. (2017). Integrating country and brand images: Using the product—Country image framework to understand travelers' loyalty towards responsible tourism operators. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24, 139–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.08.001.

- Moscardo, G., & Hughes, K. (2018). All aboard! Strategies for engaging guests in corporate responsibility programmes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.08.001.

- Nicolau, J. L. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: worth-creating activities. Annals of Tourism Research, 35, 990–1006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.09.003.

- Paek, S., Xiao, Q., Lee, S., & Song, H. (2013). Does managerial ownership affect different corporate social responsibility dimensions? An empirical examination of US publicly traded hospitality firms. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 423–433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.12.004.

- Palacios-Florencio, B., García del Junco, J., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Rosa-Díaz, I. M. (2018). Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1447944.

- Park, S.-Y., & E. Levy, S. (2014). Corporate social responsibility: Perspectives of hotel frontline employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26, 332–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2013-0034.

- Park, S., Song, S., & Lee, S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and systematic risk of restaurant firms: The moderating role of geographical diversification. Tourism Management, 59, 610–620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.016.

- Pereira-Moliner, J., Claver-Cortés, E., Molina-Azorín, J. F., & Tarí, J. J. (2012). Quality management, environmental management and firm performance: Direct and mediating effects in the hotel industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 37, 82–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.06.010.

- Pereira-Moliner, J., Font, X., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Lopez-Gamero, M. D., Tarí, J. J., & Pertusa-Ortega, E. (2015). The Holy Grail: Environmental management, competitive advantage and business performance in the Spanish hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27, 714–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2013-0559.

- Perez, A., & Rodríguez Del Bosque, I. (2014). Sustainable development and stakeholder relations management: Exploring sustainability reporting in the hospitality industry from a SD-SRM approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 174–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.07.003.

- Pérez, A., & Rodriguez del Bosque, I. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: Exploring the role of identification, satisfaction and type of company. Journal of Services Marketing, 29, 15–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2013-0272.

- Perrini, F. (2006). SMEs and CSR theory: Evidence and implications from an Italian perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 305–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9186-2.

- Prud’homme, B., & Raymond, L. (2013). Sustainable development practices in the hospitality industry: An empirical study of their impact on customer satisfaction and intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 116–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.03.003.

- Quintana-García, C., Marchante-Lara, M., & Benavides-Chicón, C. G. (2017). Social responsibility and total quality in the hospitality industry: Does gender matter? Journal of Sustainable Tourism. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1401631.

- Rahman, I., Park, J., & Chi, C. G.-q. (2015). Consequences of “greenwashing” consumers’ reactions to hotels’ green initiatives. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27, 1054–1081. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2014-0202.

- Rahman, I., Reynolds, D., & Svaren, S. (2012). How “green” are North American hotels? An exploration of low-cost adoption practices. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31, 720–727. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.008.

- Raub, S., & Blunschi, S. (2014). The power of meaningful work: How awareness of CSR initiatives fosters task significance and positive work outcomes in service employees. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55, 10–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513498300.

- Ringham, K., & Miles, S. (2018). The boundary of corporate social responsibility reporting: The case of the airline industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1423317.

- Schultz, P. W. (2001). The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 327–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0227.

- Seo, K., Moon, J., & Lee, S. (2015). Synergy of corporate social responsibility and service quality for airlines: The moderating role of carrier type. Journal of Air Transport Management, 47, 126–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2015.05.011.

- Sheldon, P. J., & Park, S.-Y. (2011). An exploratory study of corporate social responsibility in the US travel industry. Journal of Travel Research, 50, 392–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510371230.

- Singal, M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility in the hospitality and tourism industry: Do family control and financial condition matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 81–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.08.002.

- Siu, N. Y.-M., Zhang, T. J.-F., & Kwan, H.-Y. (2014). Effect of corporate social responsibility, customer attribution and prior expectation on post-recovery satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 43, 87–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.08.007.

- Smith, R. A., & Ong, J. L. T. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and the operationalization challenge for global tourism organizations. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20, 487–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.918555.

- Su, L., Pan, Y., & Chen, X. (2017). Corporate social responsibility: Findings from the Chinese hospitality industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 240–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.013.

- Su, L., & Swanson, S. R. (2017). The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tourism Management, 60, 308–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.011.

- Theodoulidis, B., Diaz, D., Crotto, F., & Rancati, E. (2017). Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tourism Management, 62, 173–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.018.

- Tölkes, C. (2018). Sustainability communication in tourism – A literature review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 27, 10–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.04.002.

- Truong, V. D., & Hall, C. M. (2017). Corporate social marketing in tourism: To sleep or not to sleep with the enemy? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25, 884902. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1201093.

- Tsai, W. H., Hsu, J. L., Chen, C. H., Lin, W. R., & Chen, S. P. (2010). An integrated approach for selecting corporate social responsibility programs and costs evaluation in the international tourist hotel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1143–1154.

- Tsai, H., Tsang, N. K., & Cheng, S. K. (2012). Hotel employees’ perceptions on corporate social responsibility: The case of Hong Kong. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31, 1143–1154.

- Tuan, L. T. (2017). Activating tourists' citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of CSR and frontline employees' citizenship behavior for the environment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1330337.

- Vila, M., Afsordegan, A., Agell, N., Sánchez, M., & Costa, G. (2018). Influential factors in water planning for sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1433183.

- Villarino, J., & Font, X. (2015). Sustainability marketing myopia: the lack of persuasiveness in sustainability communication Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21, 326–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715589428.

- Watson, B. (2016). The Troubling Evolution of Corporate Greenwashing. The Guardian. 20 Aug. Accessed at: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/aug/20/greenwashing-environmentalism-lies-companies.

- Wang, C.-J. (2014). Do ethical and sustainable practices matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on business performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26, 930–947. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2013-0001.

- Wang, C., Xu, H., & Li, G. (2018). The corporate philanthropy and legitimacy strategy of tourism firms: A community perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1428334.

- Weaver, D. B. (2014). Asymmetrical dialectics of sustainable tourism: Toward enlightened mass tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 53, 131–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513491335.

- Wells, V. K., Manika, D., Gregory-Smith, D., Taheri, B., & McCowlen, C. (2015). Heritage tourism, CSR and the role of employee environmental behaviour. Tourism Management, 48, 399–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.12.015.

- Wells, V. K., Smith, D. G., Taheri, B., Manika, D., & McCowlen, C. (2016). An exploration of CSR development in heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.01.007.

- Whitfield, J., & Dioko, L. A. (2012). Measuring and examining the relevance of discretionary corporate social responsibility in tourism: Some preliminary evidence from the UK conference sector. Journal of Travel Research, 51, 289–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511418369.

- Wong, I. A., & Gao, H. J. (2014). Exploring the direct and indirect effects of CSR on organizational commitment: The mediating role of corporate culture. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26, 500–525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2013-0225.

- Xie, C., Bagozzi, R. P., & Grønhaug, K. (2015). The role of moral emotions and individual differences in consumer responses to corporate green and non-green actions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 333–356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0394-5.

- Xu, X., & Gursoy, D. (2015). A conceptual framework of sustainable hospitality supply chain management. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 24, 229–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2014.909691.

- Youn, H., Hua, N., & Lee, S. (2015). Does size matter? Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 51, 127–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.09.008.

- Zhang, L. (2014). How effective are your CSR messages? The moderating role of processing fluency and construal level. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41, 56–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231211248462.

- Zhang, J. J., Joglekar, N., & Verma, R. (2012). Pushing the frontier of sustainable service operations management: Evidence from US hospitality industry. Journal of Service Management, 23, 377–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.04.005.

- Zientara, P., & Zamojska, A. (2016). Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1206554.