Abstract

Academia is generally carbon intensive. Many academics are highly aeromobile to an extent that is now being framed as a form of ‘climate hypocrisy’. Technological advances are not enough to reduce the negative impacts of flying, and behaviour change is needed. As tourism academics our knowledge of the industry means that we have a greater than average responsibility to show leadership, and yet currently will remain responsible for a disproportionate amount of carbon emissions. At individual and societal levels, we morally disengage from the significance of our impacts and exonerate ourselves with worthy causes, we absolve ourselves from personal responsibility, we disregard the impacts at the destination, and we discredit those impinging on our “rights” to fly. It is time for academic institutions to take responsibility and for academics to show leadership in the sector by auditing our own impacts, reducing them within our current institutional constraints, and envisaging and experimenting with low carbon business models that make us proud of being part of a sustainable solution, and not just reporting how unsustainable everyone else’s behaviour is.

Introduction

The last twelve months have been notable for the heightening of global climate concerns, and the intensification of climate action. The Extinction Rebellion (ER) protest movement has combined creative public protests with acts of wilful disruption, with transportation hubs (e.g., London Heathrow) and networks (e.g., urban public transport networks) a focus of particular attention. Greta Thunberg has mobilized a generation of climate activitists by way of school strikes and protests, and brought significant influence to the public conscience in Sweden. Aviation has been a touchstone issue for ER protesters. The flygskam (flight shame) movement has been inspired by her use of rail to attend the ER protests in London, and by travelling by ecoyacht across the North Atlantic to New York to speak at the United Nations Climate Action Summit in September–October 2019. Flygskam has resulted in a significant decline in air travel in Sweden and a concomitant increase in rail journeys.

The flygskam circumstances are unique to mature aeromobile markets such as Sweden. The same set of circumstances are not applicable in new and emerging air travel markets, such as in China, India and Vietnam, where aeromobility is seen as a marker of status and success. This is where much of the future growth in air travel lies (Boeing, Citation2019). The airline industry has been generally unwilling or unable to make significant change. Unwilling in the sense that the aviation industry discourses remain entrenched in the view that special consideration for aviation is necessary because of its importance to global business, regardless of developed or developing world status (Wood, Bows, & Anderson, Citation2012; ICAO, Citation2012; Aviation Benefits, Citation2016). Policymakers are happy to be persuaded that sustainable aviation is possible, and may be achieved through technical, energy and operational innovations (Sustainable Aviation, Citation2011). And unable because no silver bullet innovations are currently available, despite optimistic promise-making over the course of recent decades (Peeters, Higham, Kutzner, Cohen, & Gössling, Citation2016). The growing chorus of global and national protest movements, and continued inaction on meaningful emissions mitigation in key tourist transport sectors, gives reason for concerns that can no longer be willingly ignored or wished away. At the heart of these issues lie the academic community and, in particular, our own long-standing and deeply entrenched travel behaviours.

Transportation and climate

Transportation is the lifeblood of tourism. Almost a quarter (23%) of total global energy-related CO2 emissions arise from transportation. The highest emitting transport modes so happen to also be the fastest growing. Global transport emissions are currently forecast to double by 2050 (Creutzig et al., Citation2015). The IPCC highlights the fact that resolving transport emissions is critical to climate stabilization (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC),), Citation2014). In a paper published in Nature Climate Change (May 2018) it was noted that tourism accounts for 8% of global carbon emissions (Lenzen et al., Citation2018), significantly more than previously thought. Transportation is the most significant driver of high tourism sector emissions (Scott, Peeters, & Gössling, Citation2010; Scott, Hall, & Gössling, Citation2016). Aviation emissions continue to rise in both absolute and relative terms (IPPC, 2014; Bows-Larkin, Mander, Traut, Anderson, & Wood, Citation2016). Global air passenger demand has, since 1970, consistently grown at 5–6% per annum (Bows-Larkin et al., Citation2016). This represents a doubling of global passenger revenue kilometres (RPK) approximately every 18 years; a long established trend that is set to continue. The International Civil Aviation Authority (ICAO) admits that without strong regulation aviation emissions are likely to grow by 300% by 2050 (EFTE, Citation2016). Business as usual represents a threat to our collective social and environmental wellbeing (Bows-Larkin et al., Citation2016; IPCC, Citation2014, Citation2014).

Transport inequality

It is important to note the deep inequalities that exist in transportation (Banister, Citation2018). An important aspect of the aviation emissions equation is the realization that the distribution of aviation emissions is high skewed both globally and nationally. Lenzen et al. (Citation2018) outline that over half (53%) of the total global tourism carbon footprint is produced by just five countries. The combined contribution to the total global tourism carbon footprint of the top five countries is 53%; USA (24%), China (12%), Germany (7%), India (6%) and Brazil (4%) (Lenzen et al., Citation2018). Remarkably, almost a quarter (24%) is from one country, the USA (Lenzen et al., Citation2018). Globally it is estimated that 85–90% of the human population on Earth has never flown in an aeroplane (Farrier, Citation2013). The International Council on Clean Transportation (2019) reports that 12% of Americans are responsible for two-thirds of all air travel by Americans (53% take no flights in a given year) and the associated emissions (ICCT, 2019). Similarly, in the UK 15% of the population is responsible for 70% of all flights (Carmichael, Citation2019). Banister (Citation2018) reports that 54.8% of UK adults had not flown at all in the seven-year period 2006–2012.

Clearly, the great majority of aviation emissions are produced by the profligate flying behaviours or a small cross section of people in the most aeromobile societies (Banister, Citation2018). Given this realization, very reasonable questions are now being asked about reasons to fly (Gössling, Hanna, Higham, Cohen, & Hopkins, Citation2019). Such questions are particularly reasonable when directed towards those who fly excessively. Transport inequality applies equally to the academic community. The academic community falls generally into the category of high aviation emitters. Hopkins, Higham, Orchiston, and Duncan (Citation2019) note that many aspects of success in academia are linked to particular practices of corporeal mobility, drawing attention to the hypocrisy of hypermobile academics who are acutely aware of the climate crisis and the contribution of air travel to the crisis, yet remain largely entrenched in their high‐carbon aeromobility practices.

There is now a growing body of work that critically reflects upon established academic practices in relation to climate hypocrisy. At the University of Montréal, professors generate 10.76TCO2 and 2.19kgN, resulting from their average 33000 km/person per year travelled (Arsenault, Talbot, Boustani, Gonzalès, & Manaugh, Citation2019). In this journal, Høyer and Naess (Citation2001) were the first to highlight the climate hypocrisy of conference travel in the tourism field, noting the environmental burden of conference air travel, and commenting that “…it is questionable whether conferences are effective arenas for communicating and gathering knowledge”. Despite the passage of two decades since Høyer and Naess (Citation2001) published their critique, it remains that case that a stunning array of annual conferences offer academics a smorgasbord of annually recurring travel opportunities to attend conferences in often distant and exotic destinations.

Ormosi (under review) provides a quantification of conferences serving the field of economics in a given year. He reports on data from a sample of 263 economics conferences for which invited speakers and delegates travelled 417 million kilometres to attend, producing between them 50,000 metric tonnes of CO2 emissions. His analysis reports that longer conference travel distances are associated with moderately higher citation numbers for EU speakers, suggesting that local conferences are likely to deliver much the same benefits at greatly reduced social and environmental costs. Of course, it is also noteworthy that the availability of conference travel opportunities are grossly inequitable. It may be the case the 15% of academics globally are responsible for 70% of conference air travel (Cass, Shove, & Urry, Citation2005) given that, for example, academics working in the developing world have little or no access to the privilege of conference travel. Expectations of conference attendance for career progression also disadvantage women, particularly those with responsibilities to care for others (Cohen, Hanna, Higham, Hopkins, & Orchiston, Citation2020). Many years ago, Urry (Citation2003) called for new interplays of corporeal and virtual mobilities that take account of social and environmental inequalities. Perhaps this is especially true of (some) senior academics who may be particularly saturated with conference travel opportunities. Urry (Citation2003, p. 172) expressed concerns about generational inequality in travel opportunities, noting the need to “…ensure that the conditions for (academic travel) are not all used up on the hypermobile present’.

Overcoming climate hypocrisy

It is well established that in terms of reducing energy demand and mitigating emissions, the transport sector is deeply problematic (Anable, Brand, Tran, & Eyre, Citation2012). This is not only because of the absence of immediate game-changing technical solutions in the highest carbon transport modes (Peeters et al., Citation2016) but also due to social lock-in in transport policy (Banister & Hickman, Citation2013). Aeromobility is defined as the “dominance of flying as the normal international mode of traveling” (Adey, Budd, & Hubbard, Citation2007, p. 774). Academics are, as a rule, highly aeromobile. Many academics engaged in regular air travel to conduct field work, attend conferences, engage in collaborations, and deliver papers and guest lectures (Storme, Faulconbridge, Beaverstock, Derudder, & Witlox, Citation2017). Academic air travel carries an enormous environmental burden (Lassen, Citation2010; Spinellis & Louridas, Citation2013), and a resolution “…must be found in an increased understanding of the social and material basis of work travel” (Lassen, Citation2006, p. 311), based on individual experiences (Leung, Citation2013) that are set within specific geographical and institutional contexts (Lassen, Smink, & Smidt-Jensen, Citation2009; Storme et al., Citation2017).

The work sociology of academic aeromobility is important. It is necessary to understand “… what compels and motivates academics to travel” (Storme et al., Citation2017, p. 406). Existing studies generally focus on academic mobility practices in the global North (Ackers, Citation2008; Lassen, Citation2006; Leung, Citation2013; Storme, Beaverstock, Derrudder, Faulconbridge, & Witlox, Citation2013; Storme et al., Citation2017). As internationalisation has become more important, aeromobility has become increasingly entrenched. It is important to understand the drivers of academic aeromobility in relation to personal and professional connectivity and obligations of co-presence (Urry, Citation2002; Hoffman, Citation2009; Storme et al., Citation2017).

Storme et al. (Citation2017, p. 406) also observe that the complex interplay between corporeal (physical) and virtual mobility needs to be more critically addressed. We need to better understand the interplay of corporeal and virtual mobilities, and how this interplay has evolved – and continues to evolve – over time. It is also important to ask if virtual mobility substitution is likely to reduce levels of academic aeromobility. Urry (Citation2002) did note that obligations of co-presence in academia are so strong that digital communications may function as a driver of, as opposed to a substitute for, corporeal mobility (Storme et al., Citation2017). Obligations of co-presence are further cemented by institutional policy settings and forms of institutionalization that reproduce aeromobility practices (Gössling & Nilsson, Citation2010). It is interesting to note, in respect to the institutional reproduction of air travel in the form of frequent flier programmes, that a recent report by the Committee on Climate Change (UK) recommends an Air Miles Levy that escalates with the air miles accumulated by an individual over a three-year accounting period (Carmichael, Citation2019). The report notes that “In contrast to an aviation fuel tax, which would increase air fares for all passengers at the same rate, research suggests a levy aimed at excessive flying by frequent flyers could have popular support” (Carmichael, Citation2019, p. 7).

Existing unrestrained academic air travel practices are, under the current technical regime, morally and environmentally untenable (Lassen et al., Citation2009; Caset, Boussauw, & Storme, Citation2018). It is important that all academics critically reflect upon their own personal academic aeromobility practices. A growing number of academics have joined the vanguard in committing to shift their air travel practices1. Some vanguard pioneers have successfully stepped back from the high carbon transport regime. Kevin Anderson, Professor of Energy and Climate Change, University of Manchester, has actively refused to fly for many years, drawing attention to alternative and effective academic conventions. In New Zealand Prof. Shaun Hendy (Department of Physics, University of Auckland) experimented with zero flying for a calendar year, reporting some relatively modest inconvenience in domestic travel and a willingness to work around the temporary suspension of international travel. These colleagues recognize that high carbon transport use is a social convention that entrenches suboptimal social and environmental outcomes for everyone. The commitment of those who unilaterally exit the system inconveniences and disadvantages themselves without meaningfully addressing the convention itself (Mackie, Citation1996; Hechter & Satoshi, Citation1997). Ultimately high carbon conventions can only be addressed by way of collective commitment and coordinated action.

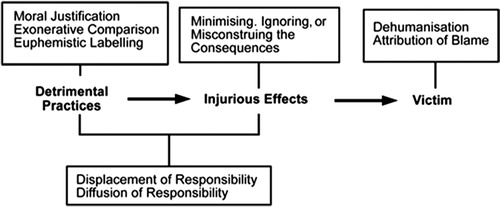

We might well pre-empt some of the responses that we can clearly expect from colleagues, by using Bandura’s theory of moral disengagement (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation1991, Citation2007) (see Figure 1). Bandura’s psychological mechanisms can help us explain how we all disengage from moral sanctions, to enable us to continue flying without the restraint of censure. We invite readers to recall personal experiences where they have engaged in such moral exclusion.

First, three mechanisms operate at the behaviour locus that allow us to believe that flying is a worthy cause. We morally justify flying in order to do our job, ironically often to teach others how to be sustainable, and we say that because we fly we are creating jobs in those locations. Exonerative comparison allows us to identify other academics that fly more than us (you can name some yourself, regularly appearing in Facebook and other social media all over the place), and allow early career researchers to say that they will stop flying once they have gained the status of professors, who can then afford to give conference presentations via Skype. And we sanitise language by saying that we are just popping over to Amsterdam for a conference, or dropping in to see a coauthor of a paper. Second, two further mechanisms operate at the agency locus, that allow us to be less accountable for our actions. We displace responsibility by blaming flying on our employers, the conference organisers, the need to attend conferences in order to achieve tenure… despite evidence that increased attendance to conferences, for example, does not influence academic success (Wynes, Donner, Tannason, & Nabors, Citation2019). We also diffuse responsibility by saying that all other academics are also flying (probably to the very same conference). Third, at the outcome locus, we limit our moral obligation by minimising, ignoring or misconstruing the impacts of flying- even when, as tourism academics, we have the industry knowledge and the intellectual capacity to fully appreciate such impacts. Ultimately, we cannot cope with the idea that we teach people how to work in an industry, tourism, that is making a disproportionate negative impact on the planet, and that our behaviour is directly contributing to the problem. Fourth, the recipients of the negative impacts from flying are depersonalised, marginalised and potentially even blamed for their destiny. The more abstract the concept of carbon remains, the easier it is to continue flying. Finally, the messengers of bad news are derogated and discredited. Critics are questioned in terms of their own motivations and their own carbon dependencies, allowing all of us to morally disengage with our own individual behaviour.

Collective commitment to aggregate actions

While unconstrained air travel emissions threaten everyone's wellbeing (IPCC, Citation2014) it is clear that individual restraint and personal sacrifice cannot on its own succeed due to the structure of the problem that we seek to resolve. It is necessary, therefore, to reframe the high-carbon air transport regime as a problem of coordinated collective action (Higham, Ellis, & Maclaurin, Citation2019). “Collective action arises when the efforts of two or more individuals are needed to affect an outcome” (Sandler, Citation2004, p. 17). Ideally, a collective commitment to aviation emissions would be expressed at the global level through international policy mechanisms. However, given the multiple failures to address aviation emissions from the Kyoto Protocol (1997) to the Paris Climate Accord (2015), the continued failure of meaningful progress under the ICAO framework is impossible to ignore.

Thus, a collective commitment to aggregate rather than individual emissions must be advanced at different scales of analysis, and may best be advanced, in the first instance, through national and local institutions. It is important, as noted in the work of Ormosi (above) that we address aggregate actions rather than (or as well as) individual behaviours. The individual approach risks the error of “ignoring the effects of sets of acts” (Parfit, Citation1984, p. 70) which is important given that the moral logic of sets of acts differs from the moral logic of isolated individual acts (Higham et al., Citation2019). Tertiary education institutions, with policy leadership from the academic community, are well placed to advance this imperative. Our moral duty is to provide leadership to achieve coordinated collective action on academic aviation emissions, and there is growing evidence to suggest that this imperative is now underway.

The Tyndal Centre has been in the vanguard of institutional change towards a culture of low-carbon academic practices (Le Quéré et al., Citation2015)2. While recognizing the benefits of face-to-face interactions, they identify no reasons why academics should be exempt from carbon mitigation imperatives. They put forward a roadmap framework to reduce emissions in line with government targets, that is informed by a simple web-based monitoring system to track emissions (Tyndall Travel Tracker) and a decision tree that is embedded into institutional Travel Management policies. The institutional response extends to advocating incentives from international and national research funding agencies to align practices, and a fundamental change in research culture.

Inspired by a groundswell of similar initiatives elsewhere, on 1st July 2019 the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment (GPE) at Concordia University adopted a flying less policy3 that is intended to stabilize and then significantly reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. This policy institutionalizes a number of commitments to encourage a low carbon working culture that include; full disclosure of individual annual flying activity, linked to annual evaluations to achieve concrete reduction targets; prioritizing travel-free meetings; prioritizing collective ground travel within 12 hours of travel; prioritizing extended visits; promoting a flying less approach; and providing financial support to encourage students and staff to attend academic activities that do not require air travel.

It is important that a collective commitment extends to our institutional partners and disciplinary associations. Academies, like the International Academy for the Study of Tourism and the International Academy for China Tourism Studies (probably others too) expect their members to attend their biennial conferences. Public research funding agencies must move further towards funding open access outputs that are widely available, rather than travel to disseminate research through closed and exclusive meeting forums and conference delegations. Disciplinary associations must also demonstrate a raft of commitments that reflect those outlined in the Tyndall and Concordia initiatives. A conference travel and emissions tracker would render the carbon footprint of individual conferences entirely transparent. Such a measurement system would soon highlight the obvious need to move annual conference to a biennial timetable. Such a step might encourage the hosting of entirely virtual conferences in alternate years, as a signal and important commitment towards changing the established high carbon social convention. A growing commitment to exploring and facilitating virtual conference contributions would allow wider contributions from keynote speakers who are otherwise burdened by a high personal carbon footprint, and potential conference contributors who are excluded from the high carbon transport regime. This shift would also facilitate the development of virtual conference satellite centres, which are likely to begin to address equity of access issues for academic communities that have been historically excluded from conference attendance and participation.

Conclusion

Participation in the high-carbon air travel regime is a social convention, and effective transition from social conventions requires policy-led coordination among players (Banister & Hickman, Citation2013; Schwanen, Citation2016). We are facing a problem that individuals must morally respond to but, acting independently, cannot resolve, whether those individuals are participants in the global tourism system, or members of the academic community. The current approach, which relies on individual sacrifice, hinders cooperation and delays an effective collective response to anthropogenic climate change (Stern, Citation2007; IPCC, Citation2014).

The Paris Climate Agreement requires that aviation emissions are stabilised and then decline rapidly (Scott et al., Citation2016). To achieve this, policy-makers must “…use the full suite of policies at their disposal” (Creutzig et al., Citation2015, p. 911) in order to meet the nationally-defined commitments expressed in the Paris Climate Agreement. Collective action will inevitably take various forms. All political, economic, legal, religious and media (mass and social) institutions have roles to play in advancing effective collective action (Higham et al., Citation2019). It is important that we also seek to advance the moral imperative through our academic institutions. We have a duty to engage in collective action in the form of policy leadership through our institutions and associations.

We invite academics to envisage a different way of doing our jobs. We first need to have the courage to audit our carbon footprint, and this may work best at the departmental level, as was done by Arsenault et al. (Citation2019). Many corporate travel agents all over the world already capture the carbon footprint of flights booked by clients, and they have the systems to report such data back, while additional carbon data on accommodation and activities can be extrapolated with some degree of confidence from the number of days travelled. Second, we need to generate consciousness about the need to manage our impacts, however that is defined within your own organizational culture, and set out some boundaries to how flying can be justified. Third, we need to publicly share changes in policy as part of our collective experiment to manage our impacts, bearing in mind the reaction that this is likely to generate from all of us, at different points in time, when we see our rights to fly being impinged. This step is important in order to develop a growing collective sense of ownership for the actions required to make tourism academia less unsustainable, and because many staff do not have any interest in using technology for example to replace part of their travel (Arsenault et al., Citation2019). Fourth, we need to develop systems that allow academics to become more effective and efficient at doing their jobs in a less carbon intensive way. The whole process cannot be one of reducing the departmental budget for flying without substantive changes in how institutions reward academics with tenure and promotion, or how academics share their knowledge with peers. What is clear is that change ahead is required, and sustainable tourism academics must lead the way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Figure 1. Psychosocial mechanisms through which moral self-sanctions are selectively disengaged from detrimental practices at different points in the exercise of moral agency.

Source: Bandura (Citation1986).

Notes

Notes

1 https://academicflyingblog.wordpress.com (see: https://docs.google.com/document/d/14NZh0bZW2jB0qXjt-pl5A2_JfHtErQhxq06ZFd61sN8/edit)

https://theconversation.com/researchers-set-an-example-fly-less-111046

References

- Ackers, L. (2008). Internationalisation, mobility and metrics: A new form of indirect discrimination? Minerva, 46(4), 411–435.

- Adey, P., Budd, L., & Hubbard, P. (2007). Flying lessons: Exploring the social and cultural geographies of global air travel. Progress in Human Geography, 31(6), 773–791. doi:10.1177/0309132507083508

- Anable, J., Brand, C., Tran, M., & Eyre, N. (2012). Modelling transport energy demand: A socio-technical approach. Energy Policy, 41, 125–138. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.08.020

- Arsenault, J., Talbot, J., Boustani, L., Gonzalès, R., & Manaugh, K. (2019). The environmental footprint of academic and student mobility in a large research-oriented university. Environmental Research Letters, 14(9), 095001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab33e6

- Aviation Benefits. (2016). Climate action takes flight. Retrieved 26 May 2016 from http://aviationbenefits.org/environmental-efficiency/our-climate-plan/

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. M. Kurtines and J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development (pp. 45–103). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bandura, A. (2007). Impeding ecological sustainability through selective moral disengagement. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 2(1), 8–35. doi:10.1504/IJISD.2007.016056

- Banister, D. (2018). Inequality in transport. Marcham, Oxon: Alexandrine Press.

- Banister, D., & Hickman, R. (2013). Transport futures: Thinking the unthinkable. Transport Policy, 29, 283–293. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.07.005

- Boeing. (2019). Commercial Market Outlook 2019-2038. Retrieved 22 October 2019 from: http://www.boeing.com/resources/boeingdotcom/commercial/market/commercial-market-outlook/assets/downloads/cmo-sept-2019-report-final.pdf.

- Bows-Larkin, A., Mander, S. L., Traut, M. B., Anderson, K. L., & Wood, F. R. (2016). Aviation and climate change: The continuing challenge. Manchester, UK: Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, School of Mechanical Aerospace and Civil Engineering, University of Manchester. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303446744

- Carmichael, R. (2019). Behaviour change, public engagement and Net Zero. A report for the Committee on Climate Change (UK). Retrieved 22 October 2019 from https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/behaviour-change-public-engagement-and-net-zero-imperial-college-london/

- Caset, F., Boussauw, K., & Storme, T. (2018). Meet & fly: Sustainable transport academics and the elephant in the room. Journal of Transport Geography, 70, 64–67. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.05.020

- Cass, N., Shove, E., & Urry, J. (2005). Social exclusion, mobility and access. The Sociological Review, 53(3), 539–555. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00565.x

- Creutzig, F., Jochem, P., Edelenbosch, O. Y., Mattauch, L., Vuuren, D. P. V., McCollum, D., & Minx, J. (2015). Transport: A roadblock to climate change mitigation? Science, 350(6263), 911. doi:10.1126/science.aac8033

- Cohen, S. A., Hanna, P., Higham, J., Hopkins, D., & Orchiston, C. (2020). Gender discourses in academic mobility. Gender, Work & Organization. doi:10.1111/gwao.12413

- European Federation for Transport and Environment (EFTE). (2016). Aviation emissions and the Paris Agreement: Europe and ICAO must ensure aviation makes a fair contribution to the Paris Agreement’s goals. Retrieved 30 May 2016 from http://www.transportenvironment.org

- Farrier, T. (2013). What percent of the world's population will fly in an airplane in their lives? Retrieved from https://www.quora.com/What-percent-of-the-worlds-population-will-fly-in-an-airplane-in-their-lives

- Gössling, S., & Nilsson, J. H. (2010). Frequent flyer programmes and the reproduction of mobility. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(1), 241–252. doi:10.1068/a4282

- Gössling, S., Hanna, P., Higham, J. E. S., Cohen, S., & Hopkins, D. (2019). Can we fly less? An evaluation of the ‘necessity’ of air travel. Journal of Air Transport Management, 81, 101722. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2019.101722

- Hechter, M., & Satoshi, K. (1997). Sociological rational choice theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 23(1), 191–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.191

- Higham, J., Ellis, E., & Maclaurin, J. (2019). Tourist aviation emissions: A problem of collective action. Journal of Travel Research, 58(4), 535–548. doi:10.1177/0047287518769764

- Hoffman, D. M. (2009). Changing academic mobility patterns and international migration: What will academic mobility mean in the 21st century? Journal of Studies in International Education , 13(3), 347–364. doi:10.1177/1028315308321374

- Hopkins, D., Higham, J. E. S., Orchiston, C., & Duncan, T. (2019). The practice of academic mobilities: Bodies, networks and institutional rhythms. The Geographical Journal, 185(4), 472. doi:10.1111/geoj.12301

- Høyer, K. G., & Naess, P. (2001). Conference tourism: A problem for the environment, as well as for research? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9(6), 451–470. doi:10.1080/09669580108667414

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2014). Fifth Assessment Report (AR5). http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/index.shtml

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2019). Special Report on the Oceans and Cryosphere in a changing climate. Retrieved 22 October 2019 from https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/home/

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). (2012). Climate change action plan 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2016 from http://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/Pages/action-plan.aspx

- International Council on Clean Transportation(ICCT). (2019). Should you be ashamed of flying? Probably not. Retrieved 22 October 2019 from https://theicct.org/blog/staff/should-you-be-ashamed-flying-probably-not

- Lassen, C. (2006). Aeromobility and work. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38(2), 301–312. doi:10.1068/a37278

- Lassen, C. (2009). Networking, knowledge organizations and aeromobility. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 91(3), 229–243.

- Lassen, C., Smink, C. K., & Smidt-Jensen, S. (2009). Experience spaces,(aero) mobilities and environmental impacts. European Planning Studies, 17(6), 887–903. doi:10.1080/09654310902794034

- Lassen, C. (2010). Environmentalist in business class: An analysis of air travel and environmental attitude. Transport Reviews, 30(6), 733–751.

- Leung, M. W. (2013). Read ten thousand books, walk ten thousand miles’: Geographical mobility and capital accumulation among Chinese scholars. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(2), 311–324. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00526.x

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 522. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

- Le Quéré, C., Capstick, S., Corner, A., Cutting, D., Johnson, M., Minns, A., … Wood, R. (2015). Towards a culture of low-carbon research for the 21st Century. Tyndall Working Paper 161, March 2015. https://tyndall.ac.uk/publications/tyndall-working-paper/2015/towards-culture-low-carbon-research-21st-century

- Mackie, G. (1996). Ending footbinding and infibulation: A convention account. American Sociological Review, 61(6), 999–1017. doi:10.2307/2096305

- Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peeters, P., Higham, J. E. S., Kutzner, D., Cohen, S., & Gössling, S. (2016). Are technology myths stalling aviation climate policy? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 44, 30–42. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2016.02.004

- Sandler, T. (2004). Global collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schwanen, T. (2016). Innovations to transport personal mobility. In D. Hopkins & J. E. S. Higham (Eds.), Low carbon mobility transitions. Oxford: Goodfellow.

- Scott, D., Hall, C. M., & Gössling, S. (2016). A report on the Paris Climate Change Agreement and its implications for tourism: Why we will always have Paris. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(7), 933– 916. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1187623

- Scott, D., Peeters, P., & Gössling, S. (2010). Can tourism deliver its “aspirational” emission reduction targets?. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 393–408.

- Spinellis, D., & Louridas, P. (2013). The carbon footprint of conference papers. PloS one, 8(6), e66508.

- Stern, N. H. (2007). The economics of climate change: The stern review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Storme, T., Beaverstock, J. V., Derrudder, B., Faulconbridge, J. R., & Witlox, F. (2013). How to cope with mobility expectations in academia: Individual travel strategies of tenured academics at Ghent University, Flanders. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 9, 12–20.

- Storme, T., Faulconbridge, J. R., Beaverstock, J. V., Derudder, B., & Witlox, F. (2017). Mobility and professional networks in academia: An exploration of the obligations of presence. Mobilities, 12(3), 405–424.

- Sustainable Aviation. (2011). Progress report 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2013 from http://www.sustainableaviation.co.uk/progress-report/

- Tyndall Travel Strategy. (2015). Retrieved 17 May 2017 from: http://oldsite.tyndall.ac.uk/sites/default/files/tyndall_travel_strategy_2015_v1.pdf

- Urry, J. (2002). Mobility and proximity. Sociology, 36(2), 255–274. doi:10.1177/0038038502036002002

- Urry, J. (2003). Social networks, travel and talk1. British Journal of Sociology, 54(2), 155–175. doi:10.1080/0007131032000080186

- Wood, F. R., Bows, A., & Anderson, K. L. (2012). Policy update: A one-way ticket to high carbon lock-in: The UK debate on aviation policy. Carbon Management, 3 (6), 537–540. doi:10.4155/cmt.12.61

- Wynes, S., Donner, S. D., Tannason, S., & Nabors, N. (2019). Academic air travel has a limited influence on professional success. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 959–967.