Abstract

We propose entrepreneurial bricolage as a framework that enables the description, explanation and exploration of the modus operandi of tourism micro-firms. Particularly, the notion of spatial bricolage constitutes fertile ground for further research and theoretical advances of sustainable tourism entrepreneurship. The potential for rural tourism development is conditioned by entrepreneurs’ capability to utilise local physical and non-material resources sustainably. Thus, knowledge about the resourcing behaviour of micro-firms is paramount to understanding their role in promoting sustainable tourism. This study explores how rural micro-firms interact with their spatial environment to design tourism value propositions. Our analysis is based on interviews with eighteen owners-managers of tourism micro-firms in rural Sweden. We portray spatial bricolage as a resourcing behaviour that builds on the re-interpretation of existing resources, the unique features of the destination and community involvement. The findings suggest that resource transfer facilitates sustainable development since it enables long-term planning and validates the entrepreneurs’ operation. Moreover, their small-scale enables rural tourism firms to utilise local resources in non-exploitative ways that minimise disturbance for other stakeholders.

Introduction

“How can sustainable tourism be understood and addressed without appreciating the role of small enterprises,” ask Thomas, Shaw, and Page (Citation2011, p.972). This important question underlines two major issues. First, that owner-managers of small-scale tourism firms promote sustainable practices consistent with their values and lifestyle motivations (Ateljevic & Doorne, Citation2000; Font, Garay, & Jones, Citation2016). Second, that the topic of tourism entrepreneurship deserves more rigorous academic attention than it has received until now (Power, Di Domenico, & Miller, Citation2017).

Despite the dramatic increase in publications since 2010, tourism entrepreneurship studies are predominantly inductive, lacking an explicit theoretical framework (Fu, Okumus, Wu, & Köseoglu, Citation2019). For the field to advance it is important to build upon the theoretical developments within the mainstream entrepreneurship research (Solvoll, Alsos, & Bulanova, Citation2015). Examples of such efforts include studies of small-scale tourism firms within the theoretical frameworks of effectuation and causation (Alsos & Clausen, Citation2014), entrepreneurial orientation (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018), risk perception (Power, Di Domenico, & Miller, Citation2019) and the opportunity-based perspective (Yachin, Citation2019).

This paper contributes to the theoretical advancements of tourism entrepreneurship by introducing the entrepreneurial bricolage framework in general and spatial bricolage in particular. Entrepreneurial bricolage is an emerging theory concerned with how entrepreneurs perceive, combine and use resources, to create value in resource-constrained environments (Davidsson, Baker, & Senyard, Citation2017; Fisher, Citation2012; Kang, Citation2017). It concerns finding solutions and realising opportunities by reinterpreting the potential use of available resources (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005). Spatial bricolage constitutes a distinct form of entrepreneurial bricolage that specifically treats the entrepreneur’s geographical context as a resource in itself (Korsgaard, Mueller, & Welter, Citation2018).

Pursuing opportunities beyond controlled resources is a key element of entrepreneurship that is particularly pertinent in the context of small-scale rural tourism firms. Micro-firms are the foundation of rural tourism (Komppula, Citation2014), acting as development agents that deliver the bulk of customer experiences and maintaining connections to a specific place (Cunha, Kastenholz, & Carneiro, Citation2018; Morrison, Citation2006). While policymakers commonly view tourism as vital for rural redevelopment (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011), limited control over necessary resources like natural and human-built infrastructure, poses a major challenge for rural tourism development (Lane & Kastenholz, Citation2015).

Through the conceptual lenses of entrepreneurial and spatial bricolage, we study how rural micro-firms engage with resources within their spatial environment to design tourism value propositions. We primarily aim to theoretically explore the concept of spatial bricolage and its applicability to tourism entrepreneurship. Additionally, we hope to generate knowledge about the entrepreneurial behaviours of tourism micro-firms in rural areas and their association with sustainability. We adopt an interpretivist stance, creating knowledge through an examination of the entrepreneurs’ subjective interpretations of their actions (Packard, Citation2017). Our analysis is based on data collected through unstructured interviews with the owner-managers of tourism micro-firms in the Swedish countryside.

Rural Sweden is ideal for studying tourism-related resources and their use. Swedish micro-tourism firms face several challenges regarding their access to capital, material and staff (Müller, Citation2013). Simultaneously, the right of public access means that, in Sweden, tourism firms can carry-out activities on land owned by others (Sandell & Fredman, Citation2010). This right generates opportunities for entrepreneurs but can cause potential conflicts with landowners and other stakeholders (Øian et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, rural tourism in Sweden is typically based on nature, wildlife and scenery, resources which, are beyond a firm’s control (Lundberg, Fredman, & Wall-Reinius, Citation2014).

This article proceeds as follows. First, we present the core behaviours embodying entrepreneurial and spatial bricolage. These function as the themes in our analysis. We proceed to: explain our approach and epistemological stance; detail how we collected, processed and analysed the data and; present the study’s geographical context. The empirical findings flesh out the themes developed in the theoretical framework. In the discussion, we elaborate on how the findings relate to the theoretical ideas of spatial bricolage and what we can learn about tourism micro-firms and rural tourism development. We conclude with thoughts that hopefully will inspire further research and promote our understanding of small-scale tourism firms and their role in sustainable development.

Theoretical framework

Entrepreneurial bricolage

Entrepreneurial resource mobilisation refers to the processes whereby entrepreneurs search, access and transfer the resources used to create value (Clough, Fang, Vissa, & Wu, Citation2019). Baker and Nelson (Citation2005) suggested that bricolage illustrates how some entrepreneurs create value in resource-constrained environments. Lévi Strauss (Citation1966) coined the term “bricolage” to describe the behaviour of the bricoleur, a jack of all trades whose “rules of his game are always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand’” (p.17). Lévi Strauss contrasts the bricoleur to the engineer. Whereas the latter requires task-specific tools, skills and material, the bricoleur uses things in ways they were not originally intended for. In the context of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial bricolage is a resourcing behaviour defined as “making do by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities” (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005, p.333). Entrepreneurial bricolage encompasses a complex and open-ended set of three main behaviours: making do, referring to creating something from nothing (e.g., designing new services through discarded, disused, or local resources that others fail to recognise); refusal to enact limitations, relating to how entrepreneurs use resources in ways that disregard commonly accepted limitations, definitions, practices and social conventions and; bias towards action and improvisation, suggesting that entrepreneurs initiate a range of projects and constantly respond to opportunities (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005; Davidsson et al., Citation2017; Di Domenico, Haugh, & Tracey, Citation2010; Fisher, Citation2012).

Engaging in entrepreneurial bricolage allows resource-constrained firms to overcome challenges, discover opportunities and increase their innovative capacity (Senyard, Baker, Steffens, & Davidsson, Citation2014). Yet, an inherent risk emerges when adhering to in-house and/or low-cost solutions at the expense of acquiring new knowledge and tools. By adopting bricolage as the firm’s identity, firms commit to a path that prevents them from growing (Fisher, Citation2012). Nevertheless, the “making do” mindset of entrepreneurial bricolage is appropriate for firms seeking long-term survival (Stinchfield, Nelson, and Wood (Citation2013).

Entrepreneurial bricolage promotes a constructivist approach, allowing researchers to explain entrepreneurial behaviours and the creation of novel services in ways that advance the contemporary entrepreneurship literature (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005). Consequently, bricolage has emerged as an important theme in entrepreneurship studies (Davidsson et al., Citation2017). One intriguing development is the application of entrepreneurial bricolage to study processes and behaviours in a geographical context, in ways that stress how place-bound features create opportunities and challenges. Examples include: how artisans create unique products (Arias & Cruz, Citation2019); how “bottom of the pyramid” individuals extract value from tangible and intangible resources (Sarkar, Citation2018); how social enterprises mobilise resources in relation to their social network (Desa & Basu, Citation2013; Di Domenico et al., Citation2010) and; how entrepreneurs engage with values and traditions to promote urban development (Kang, Citation2017). Focusing on the entrepreneur–environment nexus has theoretically advanced entrepreneurial bricolage in two directions: by identifying practices that facilitate engagement with the local community as a means to access local resources (Di Domenico et al., Citation2010) and; by re-perceiving tangible and intangible elements of a specific place as resources, upon which services and products can be developed (Kang, Citation2017). Korsgaard et al. (Citation2018) conceptualise these as spatial bricolage.

Spatial bricolage

Spatial bricolage is a distinct form of entrepreneurial bricolage consisting of localised activities. It is defined as “making do by applying combinations of the resources at hand in the immediate spatial context to new problems and opportunities” (Korsgaard et al., Citation2018, p. 4–5). The minor, yet significant, addition to Baker and Nelson (Citation2005) original definition is the conception of what constitutes “at hand”. Spatial bricolage stresses that entrepreneurs can utilise resources, which they do not own or control outright. Furthermore, spatial bricolage treats geographical context as a resource. Korsgaard et al. (Citation2018), identify three connected sets of activities helping entrepreneurs to overcome resource constraints: local sourcing; commodification through storytelling and; community involvement.

Local sourcing describes the entrepreneurs’ preference to use, whenever possible, local resources and supplies. Within the framework of spatial bricolage, local resources are the physical and non-material resources available within the immediate spatial context. Physical resources include landscapes, nature, built infrastructure and raw materials available for little or no cost. Non-material local resources encompass culture, heritage, traditions, and distinctive local identities (Kang, Citation2017). The second behaviour, commodification through storytelling, relates to how entrepreneurs create narratives that embed local physical and non-material resources into their products and services. Storytelling and the commodification of local heritage and scenery provide legitimacy and enhance the value of the firm’s offerings (Anderson, Citation2000).

Thirdly, Community involvement consists of engaging with local people through recruitment, collaborations, communication and sharing. For businesses struggling to hire or retain personnel, non-traditional labour sources, such as volunteers, pensioners and people with disabilities, embody (human) resources at hand. These are available - often dedicated - workers at lower costs or greater flexibility (Korsgaard et al., Citation2018). Collaboration and business networks enable businesses to share costs and sell products under the same umbrella (Korsgaard et al., Citation2018). Cooperation aims to generate value shared by the participating actors. It can create a supportive environment and a sense of shared responsibility. Furthermore, shared responsibility and a sense of ownership towards local common resources can mitigate the challenges and potential conflicts associated with the use of common resources that tourism businesses often depend on (Garrod, Wornell, & Youell, Citation2006; Holden, Citation2005).

Spatial bricolage is conceptualised as a means of explaining entrepreneurial practices in rural areas. The context is significant. Rural and peripheral, areas are typically limited in financial and human capital, lacking the critical mass of businesses and institutions to generate opportunities (Korsgaard et al., Citation2018). Moreover, rural entrepreneurs are embedded in their spatial context and inclined to engage in spatial bricolage (Korsgaard, Müller, & Tanvig, Citation2015b). Embeddedness is a key concept in rural entrepreneurship studies. It is defined as the nature, depth, and extent of an entrepreneur’s ties into the local environment and social structure (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002). The idea is that embeddedness provides access to local information, knowledge and contextually-bound resources (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011; Korsgaard, Ferguson, & Gaddefors, Citation2015a). On the downside, over-embedded entrepreneurs who rely heavily on local contacts and knowledge, risk stagnation due to the lack of access to external knowledge and markets (Kalantaridis & Bika, Citation2006; Saxena, Clark, Oliver, & Ilbery, Citation2007).

Spatial bricolage is effective for spatially-embedded entrepreneurs (Korsgaard et al., Citation2015b) since they have access to local resources and knowledge. Hence, embeddedness enables spatial bricolage. Concurrently, rural entrepreneurs that practice spatial bricolage and utilise local resources through community involvement, are likely to strengthen their local ties and become further embedded in their local environment and social structure. Thus, we suggest that embeddedness and spatial bricolage are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. Nevertheless, an apparent reservation arising from combining these two constructs relates to the tension between doing things differently (resource re-interpretation) and being a part of a local social structure. It is a question of whether embeddedness in a local community prevents entrepreneurs from using local resources in ways that disregard local social conventions and; if a refusal to enact limitations weakens social ties. Alternatively, perhaps embeddedness enables entrepreneurs to persuade other local stakeholders to accept their re-perception of local resources.

Tourism researchers have so far overlooked the bricolage framework. Nevertheless, nearly thirty per cent of the firms studied by Korsgaard et al. (Citation2018) were tourism-related. Furthermore, the academic tourism literature incorporates several key ideas and activities relating to spatial bricolage. There are examples of how community involvement, local sourcing and embeddedness facilitate sustainable rural tourism development (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011; Keen, Citation2004; Saxena et al., Citation2007); how storytelling enhances the tourism experience value (Anderson, Citation2000); the commodification of nature (Margaryan & Wall-Reinius, Citation2017), culture, and identity (Karlsson, Citation2005), as tourism experiences and; making use of existing facilities as a diversification strategy from farming to tourism (Komppula, Citation2004). These reinforce the application of spatial bricolage in tourism research.

Methodology

Approach

Entrepreneurial bricolage implies a constructivist approach (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005; Clough et al., Citation2019), embodied by the entrepreneur’s subjective perception and interpretation of objects in their immediate spatial context, as resources. Accordingly, we explored the entrepreneurs’ resourcing behaviour from an interpretivist stance (Schwandt, Citation2000; Tracy, Citation2013). This enables us to see entrepreneurship as a process driven by the pursuit of new value through an inside perspective of the entrepreneur’s motivations (Leitch, Hill, & Harrison, Citation2010; Packard, Citation2017). This promotes our understanding of small-scale tourism firms (Morrison, Carlsen, & Weber, Citation2010) and their relationship to rural processes and practices overall (Gaddefors & Anderson, Citation2017).

This study is a part of a broader research project on entrepreneurial behaviours in tourism micro-firms in rural areas. The entrepreneurial bricolage theory, particularly spatial bricolage, relates to the knowledge accumulated since the project’s inception. Accordingly, we revisited previously-recorded interviews, examining them through the entrepreneurial bricolage lens. To embellish our information and pursue the applicability of the bricolage framework further, we conducted additional interviews. Saturation was reached after assessing that further interviews would add little value to the analysis (Tracy, Citation2013). We had sufficient examples illustrating the different bricolage behaviours and indicating the direction of future research.

Data collection

Our investigation of how rural micro-firms engage with their spatial environment to design tourism value propositions is based on data collected through unstructured interviews with eighteen owners-managers of tourism micro-firms in rural Sweden. We collected data over three periods between 2016 and 2019. We conducted each interview with flexible questions and probes prepared according to our knowledge of the respective firms. The organic nature of unstructured interviews allowed us to stimulate a discussion (Tracy, Citation2013) revolving around the firm’s background, its products, customers and the owner-managers’ engagement with local people, culture and the environment. On average, the interviews lasted one hour. The bilingual lead author conducted the interviews in either Swedish or English, depending on the respondent’s preference. All interviews were recorded, transcribed and translated into English. presents information about the interviews and the firms.

Table 1. Studied firms.

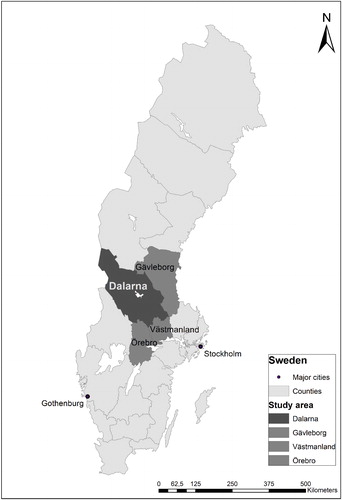

We purposely selected firms from tourism web directories and from participants we encountered throughout the project. Selected firms complied with the following criteria: (1) the European Commission’s (2014) definition of a micro-firm (fewer than 10 employees and a turnover under two million euro); (2) their main product had a stark “rural” character (functional relationship to nature and tradition) typical to Swedish tourism and; (3) they were located in Dalarna or a neighbouring county. Seven interviews were undertaken specifically for this study. We also included previous interviews only if these were: (1) recorded (accessible raw data); (2) conducted with owner-managers of tourism firms and; (3) contained sufficient discussion about resources and/or the spatial environment they operate in (this was evaluated after carefully listening to the recorded interviews). A total of nineteen interviews were analysed (F2 was interviewed twice).

Study area - Dalarna

Dalarna is located in the middle of Sweden, northwest of the capital Stockholm (). The county has 287,350 inhabitants in an area of 28,189 km2 (Statistics Sweden, Citation2019). Dalarna is a rural area, which fits what Koster (Citation2019) classifies as “the boring bits in-between”, places that are neither too remote nor within the immediate commuter belt. The county represents the rural idyll of modern Sweden, its attractions are the local culture, nature and heritage (Scott & Pashkevich, Citation2019). Dalarna is an established tourism destination catering to domestic and international, especially north-European, tourists. The main tourist season is the summer when popular outdoor activities include hiking, biking, canoeing, fishing and wildlife-watching. There is also a popular winter season for skiing and ice-skating.

Two-thirds of the studied firms operate in Dalarna. The remaining six are within 50 kilometres of Dalarna’s borders, offering products and catering to markets in-line with Dalarna’s tourism sector. We have not considered the actual county of location as relevant for the analysis, though we acknowledge that for the firms, certain implications might arise from divergent regulations and development strategies in each administrative unit.

Data processing and analysis

This study purpose is dual: (a) to theoretically explore spatial bricolage and; (b) to generate knowledge about entrepreneurship in tourism micro-firms. Thus, we use the empirical data, on the resourcing behaviours of Swedish tourism micro-firms to illustrate and develop the spatial bricolage concept, while entrepreneurial bricolage allows us to re-conceptualise tourism micro-firms’ entrepreneurship. Accordingly, we utilised an abductive approach. This involves moving between theoretical concepts and data to let one illuminate the other (Given, Citation2008). Abduction incorporates elements of both deductive and inductive analysis; the researcher analyses the data according to existing theories while leaving room for emerging themes (Skjott Linneberg & Korsgaard, Citation2019). In contrast to deductive (theory confirmation) and inductive (theory grounding) analysis, abduction aims at theory development (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002). While the validity of abductive conclusion is difficult to assess, its strength rests in guiding interpretative processes (Danermark, Ekström, Jakobsen, & Karlsson, Citation2006).

In the theoretical framework, we presented six behaviours of entrepreneurial and spatial bricolage. These, together with embeddedness, are the themes in our analysis. Subsequently, we reviewed the transcribed material and extracted passages of text, attentive to statements and examples that corresponded to these themes. The extracted passages and our commentary were placed in a table, by each firm’s ID and theme. The themes are not mutually exclusive. To accommodate relevant statements, we adjusted the themes through the process. Moreover, we searched for emerging themes that bear a conceptual interest or were extensively discussed by the interviewees (Creswell, Citation2007). When these emerged, we created additional columns in the table and reviewed all material for relevant data. This was a dynamic process resulting in a new theme, namely resource transfer as well as two sub-themes, right of public access and challenges and dependency. details the eight themes, their definitions, the literature used to develop them and a commentary on how the themes were applied to the data.

Table 2. Themes.

Limitations

The analysis draws from the entrepreneurs’ subjective perceptions and reflections. The following discussion and propositions constitute our interpretation of the entrepreneurs’ viewpoint of their resourcing behaviour and operational circumstances. Our study does not represent additional stakeholders, such as resource owners, local inhabitants or public officers. In our data collection, we used both face-to-face and telephone interviews. Certainly, face-to-face interviews can provide richer nonverbal information (Tracy, Citation2013). However, telephone interviews allowed us to reach otherwise unavailable participants

As noted, this study is a part of a broader research project, during which we encountered several instances supporting the linkage between spatial bricolage and the entrepreneurial behaviour of tourism micro-firms in rural Sweden. However, we opted to include in this study only data that was available in its raw form (i.e., recorded interviews).

Findings

We aim to theoretically explore the bricolage framework and its applicability to tourism entrepreneurship. We used data about tourism entrepreneurs’ experiences with resource mobilisation to illustrate the entrepreneurial and spatial bricolage behaviours. We present the findings according to the themes detailed in .

Entrepreneurial bricolage themes

Making do refers to using discarded or disused resources available either for free or inexpensively for new purposes. This theme addresses the resources that the firms in our study use to create their core value propositions. By far, the prominent resource is nature. The interviewees stress that forests, lakes and wildlife are rural Sweden’s main attractions. Hiking, kayaking and wildlife-watching are the most popular activities offered () while even non-nature-based companies regard nature as the core of their value proposition.

Those that come here, they come for nature. They want to see a moose, want to be in the forest. These are the main resources we have. We don’t have the time to carry any activities ourselves, but we talk and advise our guests where to go. (F9)

Making do is also manifested in the transformation of disused human-constructed physical resources, into tourism businesses. Commonly, old buildings, which were available for an affordable price, became lodging establishments. Examples include a prison (F3), a train station (F7) and three ex-schools (F1, F8 and F18). Additionally, non-material resources, such as culture and ambience constitute an important part of the firms’ value propositions. For example, the owner-manager of F4 guides tourists through a traditional animal grazing area. The experience is based on the Swedish summer farm culture and on the “special feeling you get when you are in the forest” (F4). Being in nature and participating in outdoor recreation (friluftsliv) is a cultural cornerstone and part of Nordic identity. The following quote, from an organiser of nature tours, illustrates Swedish rural culture as a non-material resource for tourism experiences:

You know, much of what we do with our guests is culture. How we engage with nature, the right of public access, fishing, being in the forest, cutting wood and picking berries and mushrooms, this is our culture and people from other countries want to know about it, anything that is local could be interesting. (F10)

Another owner-manager adds

There is a long list of “resources” that are important for the eco-tour. But probably more than anything else, it is the interaction with local people. To see a different way of rural living, that is the core product. (F5)

Thus, local culture and people constitute important resources. Similarly, the owners of a B&B (F18), conceptualise their village as a tourism product but admit their capacity to deliver tourist experiences is limited. Their creative solution was to initiate product development workshops to help locals to develop tourism experiences based on their knowledge and hobbies. This resulted in several activities thus, F18’s product became more attractive and locals were able to make extra income, share their knowledge and practice their hobbies. This “we see what is around and who is around and try to make something out of it” (F14), describes how rural tourism micro-firms develop their value propositions. The approach embodies both a strong appreciation of the place and a bias towards action.

The second theme, bias towards action and improvisation derives from the ongoing behaviour of trial and error and an ability to adapt and make incremental changes. Such behaviour relates mainly to activity-based firms, and less to B&Bs, which are predominantly occupied with daily tasks. Given the small financial risk, the firms continuously develop new products and tours, although some of these may never be realised. Moreover, incremental changes are regularly implemented. Being small allows quick adaption and improvisation.

My groups are so small that I know I can find solutions. If I need something, like a kid’s bicycle for one of my guests, I can just ask someone, I know everybody around here that has kids. (F5)

In the context of entrepreneurial bricolage, refusal to enact limitations relates to behaviour and practices challenging commonly accepted perceptions. Inherently, tourism lifestyle entrepreneurs do things differently; often manifested by moving from cities to the countryside in pursuit of a different lifestyle (F11, F16 and F18) and attempts to make a living out of ones’ hobby (F2, F5 and F15). Further, we note examples of confronting limitations imposed by local institutions. In Sweden, the right of public access is culturally ingrained (The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency [SEPA], 2019). However, even though a 1996 Supreme Court ruling established that this right also applies to organised commercial activities, there are objections to profiting from this right. These appear stronger in remote localities, possibly also aimed at non-Swedish entrepreneurs.

We learned that local people were not happy. Maybe it is about the right of public access, you know that nature is something public that should be open and now this guy from the outside … We never really cared about such talk… I think that in the end, they will appreciate it. (F7)

Predators are another problematic issue, particularly wolves. As one of Sweden’s “big five”, wolves attract visitors. Given that hunters and farmers do not always see eye to eye with these animals’ protected status, political debates arise.

You know wolves are a real taboo here in Sweden. People here accused me that I attract wolves here on purpose…I spoke to them and explained myself … Actually now I think their anger became pride, they now say it loud that it is their forest that people from all over the world come to experience because of the crazy Dutch guy. (F1)

Unlike F1, another entrepreneur abandoned her plans to conduct wolf-tours.

Yes, I had in the past an idea to have a tour that focuses on wolves. I ran it once but then decided to let it be … I think that if I would have gone on with it the whole village would have turned against me for making the wolves into a positive thing. I cannot deal with the conflicts that would have come. (F2)

Thus, tension exists between doing things differently and embeddedness. Later, we return to this issue and its potential to promote changes in informal institutions in rural areas. Also, we illustrate how firms address resource transfer, particularly concerning the right of public access. Making do and bias towards action focus on the entrepreneur’s subjective perceptions and behaviour. Conversely, the refusal to enact limitations theme constitutes a link to spatial bricolage, shifting the focus to the entrepreneur—context nexus.

Spatial bricolage themes

In spatial bricolage, community involvement relates to three practices: Drawing on local human capital; collaborating with local actors and; contributing to the local community. Discussions of human capital often relate to employees. By definition, tourism micro-firms have few employees and the majority of companies we investigated consisted of the owner-managers and their families (see ). Full-time employment is rare, but help is needed. Our data reveal alternative solutions involving practitioners (F1, F17) and employees whose salaries are subsidised through unemployment benefits (F18). Likewise, F15 employs pensioners as guides since they are an available, affordable and knowledgeable locally-based workforce that adds value. Additionally, as mentioned earlier through the cases of F5 and F18, firms can build their value propositions on locals and their knowledge.

Collaboration between tourism firms is a regular phenomenon (e.g., accommodation and activities). The studied firms illustrate such practices, although some interviewees noted that they rarely collaborate given: the absence of actors to collaborate with in the first place (F7); insufficient time (F9); or because they prefer to work alone (F1 and F8). However, we found that informal collaborations based on trust and fellowship, are instrumental. These give-and-take relationships facilitate access to resources, provide support and form a sense of belonging.

We are lucky to live in an active village. Our neighbours organise meetings where we all together decide what we want to do and actively do it ourselves … Today, for example, we meet to plan lakeside development … It is great for us that we can use it. We could have never done it without our neighbours. (F13)

Tourism businesses, by definition, cater to non-locals. Nevertheless, some of the studied firms wilfully contribute to the local community by providing free fishing (F6) and nature-based (F2) activities for local youth. In another case, the owner-manager of a B&B operates a summer café catering mainly to locals. Such actions enhance embeddedness.

We started the café; it is actually non-profit and its purpose is just to be able to keep the house. It was a great way to make friends in a small community where things tend to become insular. (F11)

Another observed aspect of community involvement is shopping locally and promoting local businesses.

The sustainable thinking is important for me and I try to help to promote the local economy, I always shop and fuel in the village. It is all on a very small scale. But I try the best I can to do business locally … I also communicate this to my guests; I recommend them to buy locally and inform of different places they can stay around here. (F2)

We noted that the scope of local sourcing, defined as prioritising locally-available resources, was unclear. To distinguish it from community involvement and making do, we restricted local sourcing to supplementary services and products. Among our cases, relying on local suppliers is common. This communicates the entrepreneurs’ values and arguably enhances their image.

All food and drinks are locally produced, for example, the beers are from a local micro-brewery and the wraps we get from a small B&B. It is something which we are proud of and we make sure our customers know, I think they appreciate it too. (F10)

Evidence of local sourcing mostly relates to food and drinks, nevertheless, making the most out of existing local resources contributes to the community and the firm in a sustainable way that minimises waste.

… Another example is the inner garden, usually, you would have pebbles or grass but it didn’t work for us, we didn’t want asphalt either. What you see here is all made from leftovers of the local stonemasonry company, we got 400 square meters for almost nothing. (F13)

Commodification through storytelling relates to how entrepreneurs enhance product value using narratives drawing on the physical and non-material features of their spatial context. We refer to this behaviour under making do. Our findings indicate that rural tourism in Sweden is commodified around narratives of nature and culture. Also, the historical features of transformed buildings (e.g., prison, train station and schools), are integral to the firms’ story and marketing (F7, F3 and F11). We also learned that the entrepreneurs’ individual life story can be part of the commodification process. Some interviewees noted that customers wish to learn about their own experiences. Thus, the entrepreneurs, their lifestyle, interests and knowledge become part of the local tourism product.

Embeddedness the final theme associated with spatial bricolage, is illustrated through the interviewees’ sense of belonging and their utilisation of local contacts. The entrepreneurs’ subjective perception is probably influenced by the duration of living in the locality in which they operate () and their personality. Nevertheless, we are primarily concerned with the interplay between embeddedness and resource mobilisation. Earlier, we suggested that embeddedness and spatial bricolage are interdependent and mutually reinforcing but also that doing things differently to what is socially accepted, can cause tension. The case of F2 illustrates the complexity of these dynamics. She has lived in the area since childhood and purposely contributes to the local community and economy. Knowledge about the whereabouts of wild animals, the core of her tourist products, stems from inhabitants and her contacts with local landowners and hunting associations. However, she believes she is not considered a true local. Only thanks to the support of her close friend, who comes from a family with a long local history, is her activity accepted. This backdrop explains her aforementioned reluctance to offer wolf-tracking tours.

Many interviewees mentioned the notion of acceptance, or approval relating to the theme refusal to enact limitations but also how the entrepreneurs’ interpretation of local resources is perceived locally. The findings suggest that the entrepreneurs’ sense of acceptance varies greatly. Some feel excluded while others experience support. This inconsistency relates to place-based contingencies such as local standards and institutions which influence the entrepreneur or specific tourism activity. Regardless, the entrepreneurs generally feel that over time, locals become proud of their activity, because they present and export the place and its culture to the world.

We also identified the support of local and regional public offices and tourism development organisations as a source of confidence for entrepreneurs, especially in the early stages of their venture. Public support communicates to the entrepreneurs that what they are doing, although it might challenge local institutions, is alright. Validation is especially important for firms utilising resources beyond their control or ownership which are accessed for free. This links to the last theme, resource transfer.

Resource transfer

Resource transfer emerges as a theme concerned with the dynamics of assuming external resources and making them one’s own. Inherent to entrepreneurial bricolage is that resources are accessible. In our study, many firms utilise local nature and culture. As resources, these are usable, albeit, not exclusive. Thus, resource transfer, the process by which entrepreneurs and other stakeholders agree on the deployment and governance of resources, is fundamental for spatial bricolage.

We have identified nature as the core resource. In Sweden, under the freedom to roam, nature is accessible. SEPA (Citation2019) dictates that using a third party’s land for tourism requires the entrepreneur to: have the necessary knowledge of, and inform participants about, the right of public access; take adequate measures to prevent damage and nuisance and; consult the county administrative board if the activity could impact the environment. However, as the owner-manager of F3 notes “The thing with the right of public access, you can interpret it in different ways”. Applying the right to commercial tourism seems unclear. None of the studied firms has ever experienced objections from landowners. Nevertheless, many express a need for validation of their activity. We have uncovered examples of their search for validation. Typically, the owners-managers contact the landowners. Locally embedded entrepreneurs easily reached informal agreements with private landowners, they “just had to ask” (F5). In contrast, those operating on land owned by forestry companies struggle to initiate any dialogue with the landowners who seem indifferent to their operation. This does not prevent these firms from conducting their activities but it means they never establish a resource transfer and are, therefore, reluctant to plan long-term and invest in expanding their operation. F1 constitutes an exception. With the local municipality as a broker, the firm’s owner-manager reached a formal agreement with Sweden’s largest forestry company to rent an adjacent forest area. The owner-manager notes that the contract validates his right to conduct commercial activity there and proves the municipality’s support. Similarly, the owner-manager of F2 stresses how important it is to get the landowners’ approval to operate on their land. To illustrate the dynamics of resource transfer she tells about her attempt to establish this right:

Where I have my bear hide, I am a part of the local road association. It is only for landowners, so I had to make them send me a bill every year. It is important for me to pay and show my appreciation, without that road I had no business… It gives me some kind of confirmation that what I do here is OK. (F2)

Hence, there is value in paying a nominal fee to validate the right to use resources that are otherwise accessible for free. This notion is strengthened in the case of fishing tourism. Fishing in Sweden requires permits produced by the landowner or responsible association. The purchase mechanism of fishing permits is simple and the rules clear. It is, therefore, unsurprising that for those firms, which deal with fishing, resource transfer is not an issue:

There is water everywhere here. You need a fishing permit but just that…the water is very accessible and could be used as we wish…just respect the local rules and you are good to go. (F6)

The core of resource transfer involves the firms’ commitment to ensuring their activities do not disturb the resources they utilise. While the main resource (nature) is easily accessible, we could not find anything suggesting that the firms have opportunistic intentions. The firms’ exhibit utmost respect for the environment, the landowners and the wildlife. A recurring notion is that the small scale of their operations means they do not bother other stakeholders. Concurrently, the interviewees worry that if tourism grows, the right of public access might become a threat to the well-being of the environment and landowners.

The interviewed entrepreneurs value resource transfer as a mechanism for establishing their activities. This behaviour is likely associated with the uncertainty they face since they depend on resources beyond their control and ownership. Examples from the data are plentiful and relate to lacking an ability to influence the local landscape to better suit tourism activities. Interviewees talk about infrastructure decay, deforestation, closed roads and over-grown vegetation blocking hiking trails. F8 expresses a common frustration:

They are a big company and we are just a small firm … I tried to talk to them but we are not in their interest … They earn money on cutting trees, but I think that in the long run, a standing forest is worth more. It is a problem. We need to explain it to our customers that come here to experience the forest and then come across clear-cut … Tourism grows in Sweden but the forest is the resource for nature-based tourism. When you take it away, you remove our ability to work. Also, it becomes that we are marketing something false…There is so much potential if you just stop taking down trees and regulate what it is allowed to do in the forest and lakes. (F8)

Discussion

Korsgaard et al. (Citation2018) conceptualised spatial bricolage as a distinct form of entrepreneurial bricolage, extending the notion of “at hand” to include resources at the entrepreneur’s immediate environment. We attempt to develop and understand this novel idea in the context of rural tourism. The bricolage framework offered a set of ideas for investigating tourism micro-firms. Our findings portray a resourcing behaviour manifested in the extensive and intentional use of local resources in ways that enhance the firm’s value proposition. Spatial bricolage underlines the broad extent of available local non-material, physical and human resource attributes. These are typically available, though their use cannot be exclusive to the firm. Hence, spatial bricolage contains a reciprocal dimension. Unlike entrepreneurial bricolage, it is not a unilateral behaviour, which makes use of disused and neglected resources, but rather it involves using resources that likely concern multiple stakeholders.

Since rural tourism utilises common resources, conflicts between stakeholders are possible (Garrod et al., Citation2006). In the context of spatial bricolage, resource transfer is about how an additional actor assumes interest in and responsibility for a resource. Clough et al. (Citation2019) explain resource transfer as a mechanism allowing resource owners to mitigate opportunistic behaviour by resource users. Conversely, our findings indicate that the entrepreneurs regularly seek contact with landowners. Such a proactive approach entails effort but promotes long-term activity (Matilainen & Lähdesmäki, Citation2014). Our study corroborates that many owner-managers of small tourism firms project moral responsibility towards the natural, cultural and social environment (Kornilaki, Thomas, & Font, Citation2019). Such values enable the application of resource transfer.

In the context of rural tourism, relationships between landowners and resource-users are often not conventional business-to-business, but rather encompass the reciprocity typical of rural culture (Matilainen & Lähdesmäki, Citation2014). Informal understandings enable access to resources, but the owner-managers of the studied tourism micro-firms appreciate the legitimacy coming from formal agreements. Validation of their activity, the sense that it is alright to use local resources the way they do, reduces uncertainty and the functional risk associated with lack of control over resources (Power et al., Citation2019). Resource transfer might require the involvement of a mediating actor to bridge over possible power imbalances between the entrepreneur and other stakeholders. In the context of rural tourism, this function could be filled by destination management organisations, which are important stimulators of local cooperation (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018). Public officers could also help mitigate possible tension between local embeddedness and doing things differently.

Entrepreneurial bricolage involves generating value by reusing resources for different applications to those for which they were originally intended (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005). In spatial bricolage, this involves the creative re-interpretation of local features. Places have their local informal institutions, such as values and norms (Welter & Smallbone, Citation2011). Such institutions might confine embedded entrepreneurs (Kalantaridis & Bika, Citation2006). However, entrepreneurs who opt to utilise local resources in ways that challenge local institutions, for example, wolves as attractions, put their social acceptance at risk. Local embeddedness is key for firm survival (Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013) and it promotes sustainable practices (Kallmuenzer, Nikolakis, Peters, & Zanon, Citation2018). Exploring the tension between embeddedness and pursuing opportunities that challenge local institutions is key to understanding spatial bricolage as a firm strategy and a behaviour that promotes change. We suggest that community involvement is vital in resolving this tension. In the context of spatial bricolage, community involvement is about awarding locals a sense of ownership and responsibility for the venture (Korsgaard et al., Citation2018). This relates to our observation that spatial bricolage contributes to local pride. In their encounters with visitors, firms represent the place and communicate local culture.

Largely, our findings corroborate the characterisation of the owner-managers of micro-firms as lifestyle entrepreneurs who relish local amenities and hold values that reflect environmental and social awareness. Previous studies demonstrated how these values dictate the actions of small-scale tourism firms (Font et al., Citation2016; Kornilaki et al., Citation2019). The bricolage theory complements the tourism entrepreneurship field with a set of concepts to describe and identify practices. Moreover, it provides a framework, within which observed tourism entrepreneurship phenomena are linked, including: the interpretation of local resources and traditions (Mattsson & Cassel, Citation2019); storytelling as means of experience enhancement (Anderson, Citation2000); flexibility to exploit opportunities and adapt to changes (Alsos & Clausen, Citation2014); going against social norms (Kornilaki et al., Citation2019) and; community involvement (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011; Saxena et al., Citation2007).

The firms in our study exhibit aspects of entrepreneurial and spatial bricolage to varying degrees. Two dominant traits are the reliance on local resources available for free or little cost and the tendency of activity providers to be proactive and seek actionable opportunities in their environment. Thus, spatial bricolage could help to mitigate the functional and monetary risks tourism entrepreneurs face (Power et al., Citation2019). Moreover, we found that personal contacts with locally embedded actors and pubic bodies facilitate resource mobilisation. The latter could be instrumental in formalising resource transfer and help tourism micro-firms in rural areas overcome challenges deriving from their small size and dependency on external resources. Nevertheless, being small is not necessarily a constraint, since it embodies lifestyle decisions, enabling catering to niche markets (Ateljevic & Doorne, Citation2000). Moreover, we argue that small-scale is a condition for rural tourism firms to be able to utilise local physical and non-material resources in ways that do not exploit the resource or disturb other stakeholders. It might be that unless tourism operations remain small, rural areas will experience what we already witness in cities worldwide (Venice, Barcelona and Dubrovnik) where, rather than being a desired development strategy, tourism emerges as a contested political question (Coldwell, Citation2017).

Conclusion

Three decades ago Williams, Shaw, and Greenwood (Citation1989) conceptualised tourism entrepreneurship as a blend of consumption and production. Since then, a considerable number of studies have promoted our understanding of tourism firms’ owner-managers. This article joins a growing body of literature that advances the tourism entrepreneurship research field by linking it to contemporary entrepreneurship theories. The bricolage framework enables us to describe, explain and explore the modus operandi of tourism entrepreneurs in ways that move us away from a persistent focus on their identity and motivations, to research focusing on their entrepreneurial behaviours. Such knowledge can advance our understanding of tourism supply dynamics and produce usable insights for public bodies and destination management organisations on how to better support tourism micro-firms. In Sweden, for example, this means addressing the ambiguity of the right of public access in ways that formalise agreements between landowners and tourism entrepreneurs.

Earlier, we addressed the methodological limitations of this study. Data about the entrepreneurs’ experiences were sufficient to illustrate the bricolage behaviours and characterise spatial bricolage as a strategy that generates opportunities and promotes sustainable development. In the past, small-scale tourism firms have been linked to sustainable development because of their motivation and values (Ateljevic & Doorne, Citation2000). Spatial bricolage has enabled us to flesh out this link and better understand it by extending it to the resourcing behaviour of tourism entrepreneurs.

Ultimately, our main contribution is the theoretical development of spatial bricolage. Rural tourism, which builds on local nature and culture, provides a remarkable context for an examination of these ideas. We now understand spatial bricolage as a resourcing strategy that is embodied by looking around to see who or what is available for use. It is an approach, which, in a tourism context, reflects that what is local could be attractive for visitors. Spatial bricolage is applicable for firms for whom the locality constitutes a fundamental part of their business; their activity could not take place elsewhere without significantly alternating its character. Thus, imperative to spatial bricolage is that alongside “making do” it is about “making with”. Spatial bricolage requires consideration of the place, its people, nature and culture, and it is conditioned by sustainably using local resources. We, therefore, suggest focusing on two main aspects, namely, resource transfer and the change of local institutions through resource re-interpretation. We do not imply that change is always good nor that all local institutions should be challenged. However, entrepreneurship is about promoting a desired change and when this desire incorporates the interests of both the entrepreneur and the local community, it leads us to associate spatial bricolage with sustainable development. Also, we ascribe much importance to the mechanism of resource transfer as it is essential for the sustainable application of spatial bricolage in ways that generate value for the entrepreneur and the locality while ensuring that the resources in question are unharmed.

The owner-manager of F11 told us that “Rural living is not for everyone; you have to be resourceful in a different way”. In a sense, this is exactly what spatial bricolage and sustainable development are all about; finding different ways to use and appreciate resources that already exist and adopting a different view on growth. In this context, we can appraise the role of small-scale tourism enterprises in channeling a connection to the locality and promoting sustainable development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Moshe Yachin

Jonathan Moshe Yachin is a member of CeTLer, the Centre for Tourism and Leisure Research at the University of Dalarna, Sweden and a doctoral student in tourism at Mid-Sweden University in the Department of Tourism Studies and Geography. His research focuses on entrepreneurial behaviours in tourism micro-firms in rural areas.

Dimitri Ioannides

Dimitri Ioannides, PhD is chaired professor of Human Geography at Mid-Sweden University. His primary interests are in the economic geography of tourism and tourism planning and sustainable development. He edits the book series New Directions in Tourism Analysis (Routledge) and sits on the editorial boards of several journals including Tourism Geographies. He is also on the board of the International Polar Tourism Research Network.

References

- Alsos, G. A., & Clausen, T. H. (2014). The start-up processes of tourism firms: The use of causation and effectuation strategies. In Handbook of research on innovation in tourism industries. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Anderson, A. R. (2000). Paradox in the periphery: An entrepreneurial reconstruction? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 12(2), 91–109. doi:10.1080/089856200283027

- Arias, R. A. C., & Cruz, A. D. (2019). Rethinking artisan entrepreneurship in a small island: A tale of two chocolatiers in Roatan, Honduras. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(4), 633–651. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-02-2018-0111

- Ateljevic, I., & Doorne, S. (2000). Staying within the fence’: Lifestyle entrepreneurship in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(5), 378–392. doi:10.1080/09669580008667374

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

- Bosworth, G., & Farrell, H. (2011). Tourism entrepreneurs in Northumberland. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1474–1494. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.015

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013). Staying power: What influences micro-firm survival in tourism? Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 125–144. doi:10.1080/14616688.2011.647326

- Clough, D. R., Fang, T. P., Vissa, B., & Wu, A. (2019). Turning lead into gold: How do entrepreneurs mobilize resources to exploit opportunities? Academy of Management Annals, 13(1), 240–271. doi:10.5465/annals.2016.0132

- Coldwell, W. (2017, August 10). First Venice and Barcelona: Now anti-tourism marches spread across Europe. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2017/aug/10/anti-tourism-marches-spread-across-europe-venice-barcelona.

- Creswell, J.W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Cunha, C., Kastenholz, E., & Carneiro, M. J. (2018). Lifestyle entrepreneurs: The case of rural tourism. In Entrepreneurship and structural change in dynamic territories (pp. 175–188). Cham: Springer.

- Danermark, B., Ekström, M., Jakobsen, L., & Karlsson, J. C. (2006). Explaining society. Critical realism in the social science. London: Routledge.

- Davidsson, P., Baker, T., & Senyard, J. M. (2017). A measure of entrepreneurial bricolage behavior. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(1), 114–135. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-11-2015-0256

- Desa, G., & Basu, S. (2013). Optimization or bricolage? Overcoming resource constraints in global social entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 26–49. doi:10.1002/sej.1150

- Di Domenico, M., Haugh, H., & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681–703. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00370.x

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- European Commission. (2014). What is an SME? Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/sme-definition/index_en.htm.

- Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019–1051. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.x

- Font, X., Garay, L., & Jones, S. (2016). Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1439–1448. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.071

- Fu, H., Okumus, F., Wu, K., & Köseoglu, M. A. (2019). The entrepreneurship research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.005

- Gaddefors, J., & Anderson, A. R. (2017). Entrepreneursheep and context: When entrepreneurship is greater than entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(2), 267–278. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-01-2016-0040

- Garrod, B., Wornell, R., & Youell, R. (2006). Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. Journal of Rural Studies, 22(1), 117–128. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.001

- Given, L. M. (Ed.). (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

- Holden, A. (2005). Achieving a sustainable relationship between common pool resources and tourism: The role of environmental ethics. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(4), 339–352. doi:10.1080/09669580508668561

- Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3

- Kalantaridis, C., & Bika, Z. (2006). In-migrant entrepreneurship in rural England: Beyond local embeddedness. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 18(2), 109–131. doi:10.1080/08985620500510174

- Kallmuenzer, A., & Peters, M. (2018). Entrepreneurial behaviour, firm size and financial performance: The case of rural tourism family firms. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 2–14. doi:10.1080/02508281.2017.1357782

- Kallmuenzer, A., Nikolakis, W., Peters, M., & Zanon, J. (2018). Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: Exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1204–1221. doi:10.1080/09669582.2017.1374962

- Kang, T. (2017). Bricolage in the urban cultural sector: The case of Bradford city of film. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(3–4), 340–356. doi:10.1080/08985626.2016.1271461

- Karlsson, S. E. (2005). The social and the cultural capital of a place and their influence on the production of tourism–a theoretical reflection based on an illustrative case study. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , 5(2), 102–115. doi:10.1080/15022250510014408

- Keen, D. (2004). The interaction of community and small tourism businesses in rural New Zealand. In R. Thomas (Ed.), Small firms in tourism (pp. 139–152). Boston: Elsevier.

- Komppula, R. (2004). Success and growth in rural tourism micro-businesses in Finland: Financial or life-style objectives? In R. Thomas (Ed.)Small firms in tourism (pp. 115–138). Boston: Elsevier.

- Komppula, R. (2014). The role of individual entrepreneurs in the development of competitiveness for a rural tourism destination – A case study. Tourism Management, 40, 361–371. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.007

- Kornilaki, M., Thomas, R., & Font, X. (2019). The sustainability behaviour of small firms in tourism: The role of self-efficacy and contextual constraints. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(1), 97–117. doi:10.1080/09669582.2018.1561706

- Korsgaard, S., Ferguson, R., & Gaddefors, J. (2015a). The best of both worlds: How rural entrepreneurs use placial embeddedness and strategic networks to create opportunities. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(9–10), 574–598. doi:10.1080/08985626.2015.1085100

- Korsgaard, S., Müller, S., & Tanvig, H. W. (2015b). Rural entrepreneurship or entrepreneurship in the rural–between place and space. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 21(1), 5–26. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-11-2013-0205

- Korsgaard, S., Mueller, S., & Welter, F. (2018). It’s right nearby: how entrepreneurs use spatial bricolage to overcome resource constraints. Academy of Management Proceedings , 2018(1), 14361. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2018.14361abstract

- Koster, R. L. (2019). Why differentiate rural tourism geographies? In Perspectives on rural tourism geographies (pp. 1–13). Cham: Springer.

- Lane, B., & Kastenholz, E. (2015). Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches–towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8–9), 1133–1156. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1083997

- Leitch, C. M., Hill, F. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2010). The philosophy and practice of interpretivist research in entrepreneurship: Quality, validation, and trust. Organizational Research Methods, 13(1), 67–84. doi:10.1177/1094428109339839

- Lévi Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lundberg, C., Fredman, P., & Wall-Reinius, S. (2014). Going for the green? The role of money among nature-based tourism entrepreneurs. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(4), 373–380. doi:10.1080/13683500.2012.746292

- Margaryan, L., & Wall-Reinius, S. (2017). Commercializing the unpredictable: Perspectives from wildlife watching tourism entrepreneurs in Sweden. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 22(5), 406–421. doi:10.1080/10871209.2017.1334842

- Matilainen, A., & Lähdesmäki, M. (2014). Nature-based tourism in private forests: Stakeholder management balancing the interests of entrepreneurs and forest owners? Journal of Rural Studies, 35, 70–79. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.04.007

- Mattsson, K. T., & Cassel, S. H. (2019). Immigrant entrepreneurs and potentials for path creating tourism development in rural Sweden. Tourism Planning & Development. Published online May 14. doi:10.1080/21568316.2019.1607543

- Morrison, A. (2006). A contextualisation of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 12(4), 192–209. doi:10.1108/13552550610679159

- Morrison, A., Carlsen, J., & Weber, P. (2010). Small tourism business research change and evolution. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(6), 739–749. doi:10.1002/jtr.789

- Müller, D. K. (2013). Sweden. In C. Fredricsson & L. Smas (Eds.), Small-scale tourism in rural areas: Trends and research in Nordic countries (pp. 41–46). Nordic Working group 1B: Future rural areas. Nordregio Working paper 2013:3. Nordregio, Stockholm.

- Øian, H., Fredman, P., Sandell, K., Saeþórsdóttir, A. D., Tyrväinen, L., & Jensen, F. S. (2018). Tourism, nature and sustainability: A review of policy instruments in the Nordic countries. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Packard, M. D. (2017). Where did interpretivism go in the theory of entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 536–549. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.004

- Power, S., Di Domenico, M., & Miller, G. (2017). The nature of ethical entrepreneurship in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 36–48. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.001

- Power, S., Di Domenico, M., & Miller, G. (2019). Risk types and coping mechanisms for ethical tourism entrepreneurs: A new conceptual framework. Journal of Travel Research. Published online September 27. doi:10.1177/0047287519874126

- Sandell, K., & Fredman, P. (2010). The right of public access–opportunity or obstacle for nature tourism in Sweden? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(3), 291–309. doi:10.1080/15022250.2010.502366

- Sarkar, S. (2018). Grassroots entrepreneurs and social change at the bottom of the pyramid: The role of bricolage. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(3–4), 421–449. doi:10.1080/08985626.2017.1413773

- Saxena, G., Clark, G., Oliver, T., & Ilbery, B. (2007). Conceptualizing integrated rural tourism. Tourism Geographies, 9(4), 347–370. doi:10.1080/14616680701647527

- Schwandt, T. A. (2000). Three epistemological stances for qualitative inquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics, and social constructionism. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2, 189–213.

- Scott, D., & Pashkevich, A. (2019). Dalarna, Sweden: Conflicted touristic representations of a place on the fringe. In Perspectives on rural tourism geographies (pp. 63–82). Cham: Springer.

- Senyard, J., Baker, T., Steffens, P., & Davidsson, P. (2014). Bricolage as a path to innovativeness for resource‐constrained new firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(2), 211–230.

- SEPA. (2019). Organised outdoor recreation. Retrieved from http://www.swedishepa.se/Enjoying-nature/The-Right-of-Public-Access/This-is-allowed1/Organised-outdoor-recreation/.

- Skjott Linneberg, M., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270. doi:10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012

- Solvoll, S., Alsos, G. A., & Bulanova, O. (2015). Tourism entrepreneurship–review and future directions. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(sup1), 120–137. doi:10.1080/15022250.2015.1065592

- Statistics Sweden. (2019). Population statistics. Retrieved from https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/.

- Stinchfield, B. T., Nelson, R. E., & Wood, M. S. (2013). Learning from Levi–Strauss’ legacy: Art, craft, engineering, bricolage, and brokerage in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(4), 889–921. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00523.x

- Thomas, R., Shaw, G., & Page, S. J. (2011). Understanding small firms in tourism: A perspective on research trends and challenges. Tourism Management, 32(5), 963–976. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.003

- Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. West Susse, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Welter, F., & Smallbone, D. (2011). Institutional perspectives on entrepreneurial behavior in challenging environments. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 107–125. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00317.x

- Williams, A. M., Shaw, G., & Greenwood, J. (1989). From tourist to tourism entrepreneur, from consumption to production: Evidence from Cornwall, England. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 21(12), 1639–1653. doi:10.1068/a211639

- Yachin, J. M. (2019). The entrepreneur–opportunity nexus: Discovering the forces that promote product innovations in rural micro-tourism firms. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 19(1), 47–65. doi:10.1080/15022250.2017.1383936