Abstract

The tourism sector is often characterized by precarious working conditions. With the aim of promoting sustainable business practices and addressing labour concerns, many tourism service providers are keen to set and enforce sustainability standards in their value chains. However, there is a contested debate on the local impacts of voluntary standards. This paper focuses on tourism labour and investigates how sustainability standards can contribute to capability building and social upgrading processes at the firm-level. It argues that most research on sustainability standards has analysed the “visible” outcomes of standard implementations while a process-based perspective is largely missing. The paper addresses this gap through a novel approach and makes both theoretical and empirical contributions. Conceptually, it integrates the dynamic capabilities approach into global value chain (GVC) research. This enhances current conceptualisations of capabilities and the understanding of upgrading processes within GVCs. Empirically, the paper investigates the South African standard “Fair Trade in Tourism” through a longitudinal, mixed-methods research design that extended over a period of eight years. The findings show how sustainability standards in tourism can contribute to capability building and upgrading at the firm-level. The paper concludes by arguing that policy makers should better resource local standard-setting organisations.

Introduction

This paper focuses on sustainability standards and how they can contribute towards better working conditions in tourism. Particularly in the Global South1, the tourism sector is often characterized by precarious working conditions with low wages, long hours, exploitation, and job insecurity (De Beer et al., Citation2013; Ladkin, Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2019; Winchenbach et al., Citation2019). The International Labour Organisation (ILO) points out that in tourism “the predominance of on-call, casual, temporary, seasonal, and part-time employment is related to insecurity, comparatively low pay, job instability, limited career opportunity, a high level of subcontracting and outsourcing, and a high turnover rate” (ILO Citation2010:14). Precarious working conditions, in turn, can have negative effects at the firm-level, including poor customer service, a high staff turnover, and additional costs for recruiting and training inexperienced workers (ILO, Citation2010).

In addressing these challenges, sustainability standards and certification systems are important because they translate the abstract concept of “sustainability” into specific organisational practices, which can be implemented locally and can potentially promote organisational change. Driven by an increasing awareness of, and demand for sustainable business practices, many tour operators have begun to set or enforce sustainability standards to address labour and environmental concerns within their value chains (Christian, Citation2017; Font & Harris, Citation2004).

A considerable body of research has focused on standards in global value chains (GVCs) (Bair, Citation2017; Barrientos et al., Citation2011; Nadvi & Wältring, Citation2004; Nadvi, Citation2008, Citation2014; Ponte & Cheyns, Citation2013; Rossi, Citation2013). Contributing to this literature, this paper uses a GVC perspective to understand whether and how standards can facilitate capability building and social upgrading at the firm-level. The paper understands capabilities as the abilities of firms to become and remain competitive in a changing environment (Teece et al., Citation1997), while upgrading is defined as economic or social improvements at the firm-level, for example increased benefits or profits for producers or improvements in working conditions (Barrientos et al., Citation2011).

The paper draws on the GVCs approach2 which is a conceptual framework that has been used by academics, including tourism researchers to analyse global production processes and local outcomes (Christian, Citation2017; Daly & Gereffi, Citation2017). GVCs connect actors at multiple scales, are coordinated by lead firms that govern production processes and comprise all the activities required to bring a product or service from conception, through production, and to its end use (Gereffi et al., Citation2005). In tourism, GVCs comprise of organisations such as travel agencies, tour operators, transportation providers, accommodation and activity providers, located in origin and destination countries.

Empirical GVC research revealed mixed evidence and uneven outcomes from the implementation of private standards and their role in promoting upgrading in GVCs (Bair, Citation2017; Locke, Citation2013). Similarly, tourism researchers have underlined constraints around tourism sustainability standards and their local impacts (Christian, Citation2017; Font, Citation2013). For example, researchers found that most tourism standards focus on the environmental dimensions of sustainability while the integration of social criteria is often insufficient (Font, Citation2013). Additionally, many tourism sustainability standards, set and enforced along GVCs, have been developed by actors in the Global North and therefore often lack local contextual relevance (Strambach & Surmeier, Citation2018). Correspondingly, small-, medium- and micro enterprises (SMMEs) from the Global South are often excluded from tourism GVCs because of difficulties in covering implementation costs and limited capabilities for meeting the requirements of international tour operators’ standards (Christian, Citation2012).

Most research on sustainability standards has analysed the “visible” outcomes of standard implementations, for example increased wage levels or eco-efficiency (Barrientos et al., Citation2011; Font, Citation2013), but the question of how, and under which conditions, tourism standards can facilitate firm-level processes of upgrading and sustainable business practices in tourism GVCs remains underexplored. Addressing this gap can enhance our understanding of the enablers of and barriers to upgrading at the firm-level (Kadarusman & Nadvi, Citation2013).

This paper makes both conceptual and empirical contributions to address this gap and develop deeper insights into the process dimension of upgrading. It is guided by the question: ‘How can sustainability standards contribute to firm-level processes of capability building and social upgrading in GVCs?’ Based on a comparative literature review, the paper develops a conceptual framework, which integrates the dynamic capabilities (DC) approach, from organisational and management studies, into the GVC upgrading research. DC are the abilities of firms to transform their resource base to become and remain competitive in a changing environment (Teece et al., Citation1997). The DC approach offers a process-based, micro-level perspective, focusing on organisational learning and capability building. Although these processes are intertwined with upgrading, they have not yet been understood in-depth within GVC research.

Empirically, the paper is located in the South African context and investigates the case of the South African standard “Fair Trade in Tourism (FTT)”3, introduced in 2003, and how it contributes to firm-level processes of capability building and social upgrading in value chains. South Africa provides an interesting context for this study as, similar to other countries in the Global South, tourism is an important sector in the national economy and, in South Africa, contributes almost 10 percent of GDP and directly employs more than half a million people (Koelble, Citation2011; World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), Citation2014). Yet, tourism’s potential to contribute to sustainable development processes is still constrained by the legacy of apartheid, which manifests in limited capabilities and market access of local tourism entrepreneurs (particularly of SMMEs owned by previously disadvantaged individuals), and in an insufficient integration of communities and previously neglected groups into tourism value chains (DEAT, Citation1996; South African Tourism, Citation2008). South Africa is characterised by higher levels of inequality and socio-economic fragmentation than most developed countries, and the tourism sector currently tends to reproduce these patterns. Therefore, efforts to promote capability building and social upgrading are critically important to facilitate a more inclusive tourism industry and alleviate poverty and inequality. Within this context, the FTT-organisation developed its associated standard to support the national government in promoting capability building and upgrading in the South African tourism industry and, as a result, the FTT-standard is well-embedded in the local institutional context. At the same time, the FTT-standard integrates global demands for more sustainable organisational practices within tourism (Strambach & Surmeier, Citation2013). Therefore, it provides valuable insights on how sustainability standards can promote capability building and social upgrading in tourism GVCs where, for example, the FTT-standard is required by international tour operators focusing on sustainable tourism (Strambach & Surmeier, Citation2018).

The empirical research is based on a longitudinal, mixed-methods design, comprising of document analysis, qualitative interviews, participatory observations and an explorative analysis of assessment data. The data collection extended over a period of eight years, from 2009 through to 2016. In total, 103 interviews were conducted, mainly with the FTT-organisation and FTT-certified businesses in South Africa but also with other actors along tourism global value chains, such as international tour operators. The empirical findings illuminate coaching & mentoring by the FTT-organisation, peer-learning between certified businesses, and changing procurement practices to create local value chains, as the most important processes that lead to capability building and upgrading within tourism value chains.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section “Bringing together research on upgrading in GVCs and dynamic capabilities,” a comparative literature review, discusses how the DC approach can advance research on upgrading in GVCs and develops a conceptual framework to interlink these bodies of literature, which is subsequently applied to the empirical analyses. The methodology, a longitudinal case study design with a mixed-methods approach, is outlined in section “Methodology.” The empirical part of the paper in section “Processes of organisational change and upgrading Outcomes - The impacts of the FTT-standard implementation,” comprises the presentation and discussion of empirical findings. It combines a social upgrading and a DC perspective to analyse the impacts of the FTT-standard implementation at the firm-level and in value chains. Section “Conclusion” summarises the research findings, derives policy recommendations, and suggests future research avenues.

Bringing together research on upgrading in GVCs and dynamic capabilities

Research on upgrading in GVCs

Economic activities in the global economy are often connected through global value chains that connect actors at multiple scales and are governed by lead firms, which coordinate most global trade (Gereffi et al., Citation2005; Nadvi, Citation2014). Although the globalisation of economic activities has created significant employment opportunities in the Global South, and led to social and environmental improvements, it has also resulted in precarious working conditions and environmental exploitation (Bair, Citation2017; Barrientos et al., Citation2011). To better understand dynamics in the global economy, GVC research explores the global division of production and labour and its local outcomes. It investigates the governance of linkages between firms located in different political and institutional contexts and analyses the roles of diverse public and private actors in setting and enforcing rules (Barrientos et al., Citation2011; Gereffi et al., Citation2005). Although most research on GVC governance has focused on the role of powerful global lead firms, more attention has recently been paid to the agency of local lead firms and how they coordinate regional or local value chains (Horner & Nadvi, Citation2018; Nadvi, Citation2014), with a central theme focussing on governance through private standards (Nadvi & Wältring, Citation2004; Nadvi, Citation2008).

Standards in GVCs increasingly address working conditions and environmental practices in the global economy and are mainly driven by changing consumer demands (Barrientos & Smith, Citation2007; Nadvi, Citation2008). At the business level, the implementation of standards has the potential to facilitate upgrading processes, which are understood as increased benefits or profits for producers, resulting from a move to higher value-added activities in global value chains based on improved technology, knowledge and skills (Barrientos et al., Citation2011).

Initial research on upgrading has taken a firm-centric and economic view towards understanding learning processes and development prospects (Coe & Hess, Citation2013). Economic upgrading has been distinguished into functional, process, product, and inter-sectoral (or chain) upgrading (Blažek, Citation2016; Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002). This distinction is considered seminal to the upgrading debate but has also been criticised for indicating a hierarchical and linear upgrading trajectory (Ponte & Ewert, Citation2009). Moreover, it is not always clear whether and how positive economic outcomes, at the firm-level, translate into better working conditions, especially in firms located in the Global South. Thus, more recent GVC research analyses the interrelations between economic and social upgrading (Barrientos et al., Citation2011; Locke, Citation2013; Milberg & Winkler, Citation2011).

Barrientos et al. (Citation2011:324) define social upgrading as “the process of improvement in the rights and entitlements of workers as social actors, which enhances the quality of their employment”. Based on ILO’s framework of ‘decent work’ (ILO, Citation1999), social upgrading can be subdivided into two interrelated elements, ‘measurable standards’, and ‘enabling rights’. ‘Measurable standards’ are relatively easy to quantify and monitor, such as improvements of working conditions in terms of, wages, employment security (contract type, social protection), and physical wellbeing (health and safety levels). ‘Enabling rights’, conversely, include less easily quantifiable aspects, such as freedom of association, collective bargaining, non-discrimination, voice and empowerment (Barrientos & Smith, Citation2007; Barrientos et al., Citation2011; Rossi, Citation2013). Social upgrading research usually analyses worker data, but this data provides limited insights on how social upgrading is achieved at a firm-level and how it can be facilitated strategically while simultaneously contributing to economic upgrading (Milberg & Winkler, Citation2011).

Thus, a more integrated understanding is needed on why, and how, some firms upgrade while others do not, and several research gaps remain (Kadarusman & Nadvi, Citation2013; Morrison et al., Citation2008). Firstly, current conceptualisations of upgrading fail to distinguish between processes that lead to upgrading and upgrading as an outcome (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015; Morrison et al., Citation2008). Although, processes and outcomes are challenging to disentangle, a clearer analytical framework of upgrading may enable researchers to better understand processes that underlie upgrading outcomes. Secondly, it is largely assumed within GVC research that learning opportunities and upgrading are determined by external influences, such as local and regional industrial policies and specific governance structures, and the so-called vertical ‘knowledge transfer’ between lead firms from the Global North and their suppliers from developing countries (Gereffi et al., Citation2005; Hansen et al., Citation2016; Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002). Conversely, limited attention has been paid to intra-firm learning and the agency of local firms in facilitating learning and upgrading within their organisations and value chains, despite an increased acknowledgement of the role that local innovation systems play in capability building and upgrading in GVCs (Lema et al., Citation2018; Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, Citation2011). Even though the importance of firm capabilities as a determinant for upgrading has been underlined (Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002; Citation2004), the nature of capabilities and processes of capability building remains underexplored in GVC research. Upgrading research barely takes note of deliberate and idiosyncratic learning strategies and there is no nuanced distinction into different types of capabilities, although these aspects seem to influence upgrading processes (Hansen et al., Citation2016; Morrison et al., Citation2008).

There is growing, yet fragmented research on the relationship between capabilities and upgrading in value chains. It includes research on innovation capabilities (Lema et al., 2018; Schmitz, Citation2007) and technological capabilities (Morrison et al., Citation2008; Staritz et al., Citation2017); Kadarusman and Nadvi's (Citation2013) research on the agency of local actors and their strategies to facilitate capability building and upgrading; and Locke’s (Citation2013) emphasis on the important role assessors play in facilitating capability building, even though their key responsibility is monitoring compliance with standards. However, these authors call for more conceptual and empirical research on capabilities within GVC literature and how these relate to upgrading prospects.

This paper, therefore, responds to this call in that it applies the DC approach to the interrelated firm-level processes of capability building and upgrading in GVCs. DC research analyses the nature and acquisition of capabilities and provides an opportunity to illuminate firm-level learning processes. The DC approach is related to research on innovation capabilities in GVCs, given that DC can be regarded as more nuanced components of innovation capabilities (Breznik & Hisrich, Citation2014). Furthermore, DC research goes beyond the technological capabilities approach through distinguishing hierarchies of capabilities and acknowledging the multi-scalar learning processes inherent to different types of capabilities. Integrating the DC approach into GVC research can, therefore, increase an understanding of how intra- and inter-organisational learning processes shape upgrading prospects in GVCs. Moreover, analysing capability building in tourism is important because tourism researchers have emphasised that upgrading occurs unevenly and is frequently inhibited by limited capabilities of tourism businesses, particularly in SMMEs (Christian, 2016a).

Dynamic capabilities – a complementary perspective on upgrading

DC research investigates a question that is also central to the GVCs upgrading debate: Why are some firms more successful than others; and how do they develop the skills and competences that allow them to gain and hold a competitive advantage within a changing environment (Teece et al., Citation1997; Helfat & Winter, Citation2011)? The DC approach first emerged from the resource-based view of firms, where favourable configurations of physical, human and organisational resources, necessary to reach organisational goals, are analysed (Barney, Citation2000). The resource-based view, however, is limited in explaining how firms transform their resource base to remain competitive in a changing environment. Research on DC addresses this gap and focuses on the processes that organisations use to change and renew their resource base and create new sources of value (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000; Teece et al., Citation1997; Teece, Citation2012).

DC were originally defined by Teece et al. (Citation1997:516) as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments.” Firms use operational capabilities, expressed as organisational routines, to conduct repetitive actions within a work process. Routines are “the building blocks of organisational capabilities” (Becker, Citation2004:662), emerge in a path-dependent way, are context-dependent and shaped by institutional frameworks (Becker, Citation2004; Nooteboom, Citation2010). DC have different purposes and outcomes from operational capabilities (Helfat & Winter, Citation2011). As “capabilities to develop or change capabilities” (Nooteboom, Citation2010:173), they enable firms to strategically change operational capabilities and, therefore, they are important for the firm’s future viability. DC are path-dependent in their emergence and idiosyncratic to the firm; they cannot be transferred easily but must be constructed on learning processes and the development of organisational routines (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). Research on DC, however, is a contested debate and there is no universally accepted set of DC (Helfat & Winter, Citation2011; Zahra et al., Citation2006).

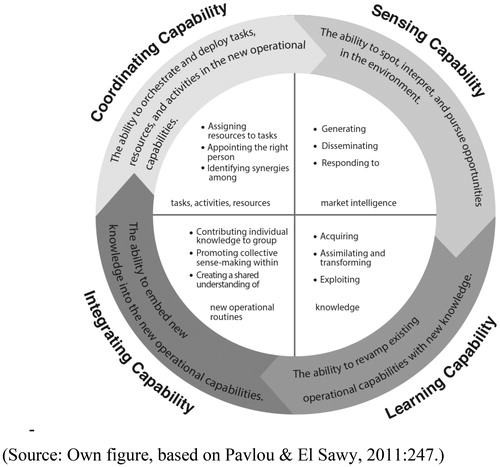

This article employs Pavlou and El Sawy (Citation2011) set of DC, which is based on Teece et al. (Citation1997) and Teece (Citation2007) seminal work, but it also draws on a more extensive literature review as a basis to distinguish between the DC of sensing, learning, integrating and coordinating (see ). While sensing is understood as the ability to spot, interpret and pursue opportunities in an environment, learning represents the ability to revamp existing operational capabilities with new knowledge. Integrating refers to the ability to embed individual knowledge into an organisation’s new operational capabilities through collective sense-making. Coordinating is the ability to orchestrate and deploy tasks, resources and activities in the reconfigured operational capabilities. Pavlou and El Sawy (Citation2011) suggest that these capabilities interact in a sequential logic to reconfigure existing operational capabilities, yet, they are also characterised by reciprocal relationships as illustrated in .

Figure 1. Dynamic capabilities and associated routines. Source: Own figure, based on Pavlou & El Sawy, Citation2011:247.

Empirical research on DC mostly analysed the DC of large, established, for-profit organisations, often focusing on manufacturing or knowledge-intensive services (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). However, some researchers have also analysed the DC of entrepreneurs (Zahra et al., Citation2006) and a small yet nascent body of literature transferred the approach to social enterprise research, which attempts to understand how organisations can build and exploit DC to reach social goals (Corner & Kearins, Citation2018; Tashman & Marano, Citation2009). In addition, while there is some research on DC in tourism (Camisón & Monfort-Mir, Citation2012; Denicolai et al., Citation2010; Nieves & Haller, Citation2014), such research focuses on tourism businesses in the Global North and has not yet been brought to the sustainable tourism realm with reference to the Global South.

Integrating a dynamic capabilities perspective into the GVC’s upgrading research

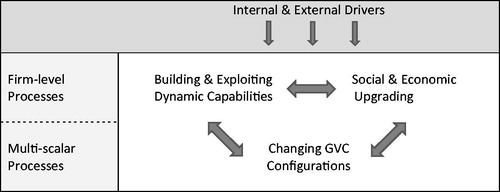

Research on DC can complement GVC upgrading research. As visualised in , internal and external drivers, such as social norms or regulatory requirements, can facilitate organisational change and influence processes of DC building at the firm-level (Scott, Citation2014). This paper proposes that such processes are not only interrelated with upgrading in GVCs but are the underlying processes that can lead to upgrading outcomes in GVCs. Upgrading outcomes represent changes in firm resources, for example, in the knowledge base of the firm, which, in turn, impacts the exploitation of DC. When organisations use DC to change their resource base, they may become more competitive in the market, promote social and economic upgrading, and possibly get access to, or move into a more favourable position within existing GVCs, and, in this way, transform them, or create new GVCs, and vice versa, in iterative processes. Therefore, firm-level processes of organisational change have implications for the multi-scalar governance and configurations of GVCs.

Figure 2. Dynamic interrelations between dynamic capabilities, upgrading and GVC configurations. Source: Own figure.

Applying a DC perspective to investigate how standards contribute to upgrading in GVCs has several strengths. Similar to the research on technological capabilities in GVCs (Staritz et al., Citation2017), the DC approach focuses on the micro-level of the firm and provides an opportunity to analyse the agency of actors in facilitating organisational change and how these processes are related to GVC dynamics. Integrating DC and GVC perspectives also helps to reveal internal challenges and opportunities that can hinder or enable firm-level upgrading processes. Furthermore, because these processes often unfold slowly, they may remain hidden when only an outcome-based upgrading perspective is applied. Thus, applying a DC view to analyse GVC upgrading helps to conceptually distinguish upgrading processes from “visible” upgrading outcomes and, therefore, it enables researchers to capture learning processes rather than just tangible upgrading outcomes. Additionally, research on capability building acknowledges that, at the firm-level, economic improvements are inseparably intertwined with social learning processes and evolving social practices (Nooteboom, Citation2010). Thus, it provides an opportunity to concomitantly study the interrelations and co-evolution of different forms of upgrading and may provide better insights into how upgrading occurs.

Applying a DC view to investigate GVC upgrading requires longitudinal micro-level analysis to investigate how changes in business practices evolve over time. This paper adopts such an approach.

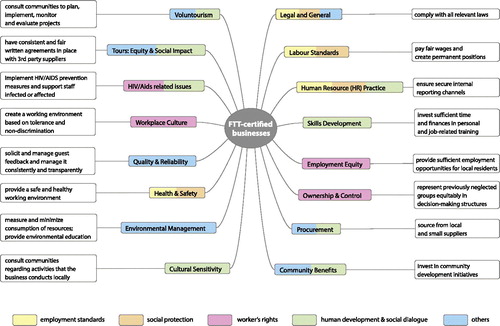

Methodology

The empirical research is based on a longitudinal case study design with a mixed methods approach. It investigates the South African “Fair Trade Tourism (FTT)” standard over a period of eight years — from 2009 through to 2016 — to understand how private standards can contribute to capability building and possible upgrading in GVCs. The FTT-standard was chosen because it focuses on the social dimension of sustainability, has been developed in the Global South, and intends to drive both intra- and inter-organisational learning and capability building. As opposed to other South African tourism standards, which focus on quality performance or the environmental dimension of sustainability, the FTT-standard addresses internal working conditions within businesses and the creation of linkages to local suppliers and communities (see ). The standard is compliant with national legislation including Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) requirements and ILO Core Labour standards (ITC, Citation2016). The FTT-standard is divided into 16 categories and includes social (49%), ecological (32%), and economic (19%) of standard criteria requirements (ITC, Citation2016). FTT certification is available to established and emerging tourism businesses of any size. The application process starts with an online self-assessment and is followed by an on-site assessment, lasting multiple days. Re-assessment is done every three years and certified businesses must report on their improvements, annually online (FTT, Citation2018). At the time of writing, there are 99 FTT-certified tourism businesses in South Africa, Madagascar and Mozambique. Additionally, there are 105 tourism businesses in five African countries that have been recognized as meeting the FTT-standard requirements through mutual recognition agreements (FTT, Citation2018).

Figure 3. Examples of Fair Trade in Tourism (FTT) Requirements. Source: Own figure based on FTT, 2013; ILO, Citation1999 and ITC, 2016.

The mixed-methods design included document analysis of newsletters and reports of the FTT-organisation and FTT-certified businesses. At the core of the research design were 103 explorative or semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders, presented in . Furthermore, the interview data was triangulated with an explorative analysis of quantitative assessment data, provided by the FTT organisation.

Table 1. Overview of Empirical Interviews.

Regarding certified businesses, theoretical sampling strategies were applied with selection criteria consisting of price-category, size, services, certification-time, and geographic location, thereby, representing the entire range of certified businesses. Some businesses were interviewed multiple times to analyse how the impacts of the standard implementation evolved over a time period. Most interviews included on-site visits lasting several days.

The main topics of the interview guide investigated reasons behind the standard implementation; associated changes in organisational practices (including strategies, opportunities and challenges to bring about these changes via DC); and the role of the FTT-organisation in supporting these processes. Upgrading outcomes were captured through intra- and inter-organisational results, from new organisational practices and standard implementations. Changing value chain configurations were investigated through questions about linkages with firm-external actors, such as local suppliers and national and international tour operators.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed to ensure accuracy, transparency and avoid loss of information. The qualitative data analysis followed the methodological approach of the qualitative content analysis (Mayring, Citation2014), a method to systematically analyse qualitative data. Central to the analysis was the use of categories, which were derived in iterative processes, developed deductively from theory, and inductively from the interview material, and applied to analyse the transcribed text.

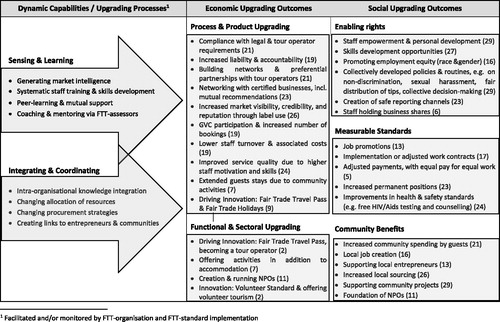

Subsequently, qualitative interview data was triangulated with quantitative assessment data provided by the FTT-organisation. While qualitative data contributed to a deeper understanding of processes that hinder or foster capability building and upgrading, quantitative data helped to explore the ‘hard facts’, for example, wage levels. Many challenges in the quantitative data analysis occurred because of an inconsistent and dispersed data base. Complete assessment data was available from 18 certified businesses, in total, but time series data was only available from six businesses. Due to these limitations, the available quantitative data could only be used in an explorative way, but still provided in-depth information. While provides an overview of the empirical evidence4, the next section presents and discusses the empirical findings.

Processes of organisational change and upgrading outcomes - the impacts of the FTT-standard implementation

Recent GVC research has focussed on the agency of local firms when coordinating regional or local value chains in the Global South (Horner & Nadvi, Citation2018). In this study, FTT-certified businesses are considered local lead firms that govern local value chains. Studying the way in which FTT-certified businesses used the FTT-standard to change their organisational practices adds important insights into the agency of actors, when driving capability building and social upgrading within their organisations and local value chains, and into the implications of these processes for GVC configurations.

FTT-certified businesses comprise a heterogeneous group of businesses in terms of size, location, and organisational age. They range from established urban luxury hotels to community-based micro entrepreneurs and backpacker accommodation5 in rural areas. The key drivers for the implementation of the voluntary FTT-standard were normative, values-based motivations and a desire to ‘make a difference’ within the South African context. The capabilities of FTT-certified businesses varied across different areas with regards to strengths and weaknesses. Established businesses usually possessed operational capabilities to conduct their daily business, as per national legislation and international tour operator’s requirements, and used the FTT-standard to strategically implement responsible management practices. One of the first certified businesses explained:

“There was no overriding strategy about how to apply socially and environmentally responsible practices in tourism. The reason was not so much to get it, but it was actually to learn how to do it.” (Interview 2009; urban hotel 1).

Although emerging businesses were often well-embedded locally, they wanted to use the standard as a tool to develop operational capabilities and professionalize organisational routines. Moreover, many businesses expressed an expectation that once the FTT-label gained some market value it would help them to develop a unique selling proposition (USP), giving their businesses external credibility and validation and enabling better access to GVCs (Interview 2009, urban backpacker 1; rural safari lodge 1; Interview 2014, rural backpacker 1/2).

Dynamic capabilities – a process-based perspective on upgrading

The following section analyses how the FTT-standard implementation helped certified businesses to build and employ DC and promote social upgrading within their organisations and value chains, using the DC and associated routines in . For analytical purposes, the DC are investigated in a sequential logic, however, it is important to note that there are interrelations and overlaps in practice.

The capabilities of sensing and learning

Sensing market and community needs

Christian (Citation2016a) found that SMMEs from the Global South have limited access to market intelligence, understood as knowledge on trends, competitors and customer demands. This lack inhibits their GVC insertion because they need this knowledge to sense and seize market opportunities. The FTT-organisation bridged this gap through pro-actively generating, disseminating and exploiting market intelligence, for example, by representing and marketing FTT-certified businesses through regular participation at national and international industry events, including trade fairs and road shows. When funds were available, the FTT-organisation also invited some certified businesses to participate at such events to get insights into current market trends, promote their businesses, and build new networks with, for example, international tour operators. Small businesses valued these activities as they often lacked the financial resources to generate market intelligence and build relationships with actors along tourism GVCs (Interview 2009, urban backpacker; Interviews 2013, urban activity provider; rural backpacker).

Furthermore, as required by the FTT-standard, FTT-certified businesses also sensed community needs within their environments through processes of community consultation and, subsequently, pursued opportunities to address identified needs. Although organisational responses were adapted to specific contexts, they frequently focused on promoting job creation and access to quality education and healthcare within communities. Rather than the FTT-organisation actively engaging with these processes, the FTT-standards structured the implementations of these activities. This shows how the engagement with the FTT-organisation and the FTT-standard facilitated both the ability to sense global market trends and customer demands, relevant to become and remain competitive in GVCs, and the sensing of local needs, which are important to consider when embedding new organisational practices locally.

Firm -level learning processes

The FTT-organisation and the FTT-standard implementation facilitated the DC of learning directly and indirectly: through collaboration with the FTT-assessors, via intra-organisational skills development activities, and between FTT-certified businesses.

Learning facilitated by FTT-assessors

Similar to Locke’s (Citation2013) observations, FTT-assessors supported the dynamic learning capability of the certified businesses through, firstly, assisting them to acquire new knowledge and then adjusting it to their organisational context. During assessments, assessors engaged in information sharing, the diffusion of best practices, and joint problem solving via coaching and mentoring. Assessors also adapted their experience-based and context-specific knowledge to individual businesses’ needs and consulted with FTT-certified businesses on how to meet FTT-standard requirements. The FTT-assessors provided process-based strategic guidance and they operationalised organisational change, required for GVC insertion, into specific tasks and goals, which could then be ordered according to priorities. This was appreciated by the businesses:

“We had an assessment where we improved tremendously. We had 23 points that we had to get in order. By the time she (the assessor) came back we had all 23 in order and we got 13 points more - which is great because you can always strive for something more” (Interview 2009, rural country lodge 1).

While most established businesses fulfilled legal requirements, emerging businesses appreciated how implementing FTT-standards helped them to build operational routines and professionalize management practices, which, in turn, enabled them to fulfill national legal requirements and tour operators’ demands, both needed for GVCs participation (Interview 2014, rural backpacker; Interview 2009, rural country lodge; urban activity provider; urban hotels). An owner of an emerging business from a very remote part of the Eastern Cape explained:

“FTT helped us a lot in terms of getting the business legal. It is so easy to start a business in this country but no one of us ever realizes what the legal requirements are and what the customers’ requirements are.” (Interview 2014, rural backpacker 1)

Most learning processes, and associated changes in organisational routines, happened at the beginning of FTT-standard implementations, particularly between the first two assessments (Interview 2009; urban hotel; rural country lodge 1; Interview 2014, rural backpacker; urban activity provider). However, over time and with increased absorptive capacity, some businesses found it easier to implement standard requirements despite initial difficulties. Moreover, as learning processes developed, businesses built DC to drive intra- and inter-organisational changes more independently. Repeated interactions with FTT-assessors led to increased development of trust. Conversely, when assessors changed, some certified businesses expressed disappointment with their replacements, who they considered as less competent and with less valuable suggestions than their predecessors. Some FTT-certified and formerly certified businesses felt that their knowledge on how to address challenges within their environment had exceeded the knowledge of the assessors over time so that their advice was not perceived as valuable to them anymore (Interview 2013, urban activity provider; urban hotel; Interview 2015, urban backpacker, rural backpackers). This unexpected result indicates that the experienced-based and contextual knowledge of individual assessors, and established relationships between assessors and certified businesses, play an important role in facilitating DC at the firm-level.

Skills development and learning within certified businesses

Research on social upgrading in GVCs usually analyses staff empowerment and enabling rights at a collective level, with limited empirical GVC research existing on how training can contribute to staff empowerment at the firm-level. Findings from this study indicate that learning and empowerment were facilitated through internal skills development activities and, as a result, human resources were enhanced. Implementing the FTT-standard required businesses to revamp organisational routines to facilitate more systematic and transparent staff training and include staff in the selection of training, with a view to changing the employment structure and enable previously disadvantaged workers in particular to move to higher-skilled positions. Job-related training, such as guest liaison or computer courses, aimed to improve the quality of services and promote economic upgrading while personal development trainings aimed to promote social upgrading. These processes were, however, challenging and several FTT-certified businesses, particularly in rural areas, underlined the barriers in promoting job mobility. One interviewee underlined:

“Probably 95% of the people that work here are from the immediate area. One of the biggest issues is the training. The majority of the people from the area are not that well educated or have knowledge of the tourism sector, so getting them to start from scratch with the training is hard.” (Interview 2013, rural backpacker 3).

Correspondingly, although training investments were reported to have positive impacts, such as positive staff feedback, higher job satisfaction, staff motivation, and a lower staff turnover, investments in trainings, during the analysed time period, frequently did not translate into aspired visible social upgrading outcomes, such as job promotions. In line with Morrison et al. (Citation2008) findings, this indicates that the existing resource-base (including human resources) and the absorptive capacity of firms influences whether and how fast, or slow, upgrading outcomes evolve in value chains.

Peer learning between certified businesses

In addition to intra-organisational learning, FTT-certified businesses also supported each other in acquiring and exploiting knowledge necessary for the FTT-standard implementation. Knowledge-based approaches, from innovation studies, accentuate that both the absorptive capacity of actors and the creation of different forms of proximity are decisive for learning processes and knowledge generation (Strambach, Citation2017). Correspondingly, due to geographical and relational distance, a “knowledge transfer” along GVCs and between actors from different institutional context is often challenging (Hansen et al., Citation2016). In the case of FTT-certified businesses, social and cognitive proximity (such as sharing similar values, goals, and facing similar challenges) enabled collaboration and co-learning between owners and managers. In addition, after the FTT-organisation initiated initial networking, many certified businesses continued collaboration and mutual support around implementing FTT-standard requirements and some businesses developed close collaborations based on trust:

“We deal a lot with the same problems and we share ideas a lot on what we have to deal with whether it is on the community-level, at a social level or practical level. We are on the phone talking to each other almost every day.” (Interview 2013; rural backpacker).

Additionally, some businesses started mentoring projects, where established businesses helped emerging ones to develop operational routines and implement more sustainable business practices (Interviews 2009; urban and activity provider). A better understanding of such peer learning practices, how they are facilitated through the implementation of sustainability standards in value chains, and how they are enabled through geographical and relational proximity, may be valuable to inform strategies to support processes of capability building and social upgrading.

The capabilities of integrating and coordinating

While learning is mainly associated with knowledge owned by individuals, the DC of integrating brings a shared understanding and collective sense-making towards new operational capabilities and can enhance the coordinating capability. Furthermore, because DC literature focuses on an ability to coordinate tasks, resources, and activities within firms, it complements GVC coordination research, which investigates mechanism to govern complex linkages between globally disperse actors along value chains.

Knowledge integration and coordination within FTT-certified businesses

Promoting enabling rights through integrating

The FTT-standard facilitates the DC to integrate because it requires FTT-certified businesses to promote a shared understanding and embed individual knowledge and staff demands into their organisational routines. Consequently, FTT-certified businesses must develop certain policies and associated routines collectively with their staff — for example, on non-discrimination, sexual harassment, the fair distribution of tips, or collective decision-making. Resulting routines integrate not only technical knowledge, which is directly work-related, but also cultural and context knowledge, which may affect the staff’s work performance, such as religious, cultural and contextual conditions. These collective processes promote social upgrading and ensure fair business practices within certified businesses and their value chains but were often considered challenging. For example, some FTT-certified businesses realised that technical approaches to embed cultural and context knowledge into organisational capabilities were not sufficient as these processes needed to be based on trust, mutual understanding, and social proximity (Interview 2009; urban hotel, Interview, 2013 rural backpacker). In such cases, some certified businesses used informal activities as a tool to break down socio-economic barriers and connect with each other. This was valued by staff:

“The whole lodge goes on holiday together, everyone! From the gardeners to the owners. We all come from very different cultural backgrounds. We all work together. Our best one is when we go to the beach, we have beach games. Everybody can come” (Int.2009, urban lodge).

Although informal collective activities went beyond FTT-standard requirements they seemed to ease formal approaches of knowledge integration into organisational policies and associated routines. It was also expressed that collectively developed written policies helped to create more transparency in the workplace because they were perceived as formally binding and more reliable than verbal agreements; thus, contributing to better accountability for workers and suppliers and more awareness of staff rights (Interview 2012; FTT-assessor).

While the FTT-organisation was not directly involved in the development of the idiosyncratic policies and routines, FTT-assessors held confidential staff interviews during assessments, to ensure that associated routines were implemented. These interviews aimed to strengthen the workers’ voice and created external reporting channels (Interview 2015, assessor 2/3; Interview 2016, FTT). The challenges met — a need for trust and mutual understandings and social proximity — correspond to Cockburn-Wootten (Citation2012) suggestions on how to create more meaningful working conditions in tourism.

Implementing measurable standards through coordinating

In addition to promoting enabling rights through knowledge integration, the DC of coordinating and associated routines, together with associated standard requirements, influenced measurable standards of social upgrading — particularly through employing previously disadvantaged people and changing practices when allocating resources, such as wages, work contracts, and the creation of permanent positions. FTT-certified businesses are expected to pay above minimum wage, to reach a living wage, or to offer benefits such as medical aid, a contribution to education, transportation, or meals. They must also provide equal pay for equal work, especially relating to race and gender. During assessments, these processes were monitored and adjusted when necessary (Interview, 2016, FTT). The FTT-standard further requires businesses to coordinate their activities and create as many permanent positions as possible. This was in line with the businesses’ values:

“We only make a profit 5 months of the year, the rest we make a loss. So, we have to make enough during whale season to cover us through the year. But we rather keep our staff employed than getting rid of them” (Interview 2009, urban activity provider).

The quantitative analysis showed that on average the analysed FTT-certified businesses turned 95% of all positions into permanent, full-time positions. This is a high share in the seasonal tourism industry. Furthermore, in several emerging businesses, work agreements had only been in place verbally or did not fulfil legal requirements, set by the national government. To become certified, businesses had to introduce legally binding contracts that formalised the allocation of tasks and resources, complied with national legislation and were fully understood by all workers.

Aligned to the B-BBEE legislation of South Africa, the FTT-standard also addresses issues of ownership and control across racial lines. The majority of FTT-certified businesses were owned and controlled by white people and, similar to Christian’s (Citation2016b) findings on tourism in Kenya, path-dependent ownership structures in South Africa limited social upgrading outcomes and was, therefore, perceived by the FTT-organisation as one of the most challenging aspects to change (Interview 2015, FTT; Interviews 2009, assessor 1; urban activity provider; Interview 2013, urban activity provider). These insights underline the limitations of the FTT-standard in promoting structural change in the South African tourism industry in which ownership structures are still racialised.

Knowledge integration and coordination of local value chains

Beyond integrating and coordinating intra-organisational tasks and resources, certified businesses used the DC of integrating and coordinating to include, and coordinate, SMMEs from previously disadvantaged groups into their local value chains, to create linkages with local communities, and to drive upgrading processes within value chains and at a community level (Interview 2009, assessor; urban hotel; Interview 2013, urban hotel).

A key challenge in these processes was the limited number of local businesses owned by previously disadvantaged groups, particularly in rural areas, often because of a lack of essential capabilities and financial means. FTT-certified businesses, therefore, assisted emerging entrepreneurs (such as food and laundry service providers, artists, and activity providers) to start businesses that could be included into their value chains. Entrepreneurs sometimes received financial assistance from the FTT-certified businesses, when developing new businesses and building operational capabilities (such as guest liaison, language skills, reliability, and finance management) but most assistance occurred via coaching and mentoring (Interview 2009, urban hotel; Interview 2013, urban backpacker; Interviews 2014, rural backpackers 1/2/3). These integration processes required significant time commitments from the certified businesses, and it was challenging to coordinate small, often inexperienced suppliers rather than using established organisations, however, it provided positive local outcomes. The FTT-organisation had mainly a monitoring role in relation to coordinating activities of the certified businesses. They investigated whether fair and transparent contracts and income distribution systems were in place with third parties.

Furthermore, most FTT-certified businesses actively collaborated with communities to tackle local challenges. Although community engagement had already been in place in most cases, the FTT-standard required certified businesses to coordinate their activities more systematically. One of the major outcomes was the foundation of non-profit organisations (NPOs). FTT advised some businesses to start these new organisational forms to be able to apply for government funding, receive donations, and get tax advantages. However, for many FTT-certified businesses, it was difficult to run two organisations at the same time, especially because most of the businesses had no prior experience in the NPO sector (Interview 2013, rural backpacker), and they often had to hire additional staff to support them, which was costly. Yet, caring for communities and including SMMEs from previously disadvantaged groups into local value chains was driven by the organisational values of the FTT-certified businesses and resemble Winchenbach et al. (Citation2019) findings on how to create meaningful work and quality employment in tourism.

Driving innovation and upgrading in value chains

Exploiting DC, built over time, allowed some FTT-certified businesses to develop innovative responses to combine market and social needs. All certified businesses developed innovative ways to integrate community projects into their local value chains and frequently provided opportunities for guests to visit the community projects. In this way guests gained deeper insights into the South African context and they could also financially support community projects. Moreover, FTT-certified businesses received feedback which suggested that these activities helped to upgrade the quality of overall guest experiences and they promoted upgrading at a community level through local communities benefitting from the inclusion in local value chains (Int. 2009, rural luxury lodge 1/2; Int. 2014, rural backpackers 1/2/3).

Additionally, several businesses went beyond this and developed new products, such as eight FTT-certified businesses who collaboratively developed a product innovation called the “Fair Trade Travel Pass”. The pass is like a package tour, directed at the backpacking market, and consists of FTT-certified businesses only. Through functional economic upgrading, two of the FTT-certified accommodation providers, based in Johannesburg and Cape Town, developed new capabilities and became travel agents, marketing and selling the Fair Trade Travel Pass, while more FTT-certified businesses were included (Interviews 2013, urban & rural backpackers).

Two certified businesses also sensed concerns about a perceived lack of regulation and malpractices within the growing volunteer tourism market. Concomitantly, they identified needs within communities, which could be addressed when volunteers paid for their placements. The two businesses collaborated with the FTT-organisation and collaboratively developed an innovative standard for volunteer tourism, which is based on the original FTT-standard and requirements (Interviews 2012/2013/2016, FTT-organisation; Interviews 2015; urban activity provider, rural backpackers). Subsequently, they extended their business activities into the volunteer tourism sector and implemented the FTT volunteer tourism standard in 2010, which distinguished them from other volunteer tourism providers. Through sectoral and functional upgrading, they became local tour operators in the international volunteer tourism market and could link their activities into GVCs.

The FTT-organisation also used DC to drive innovation when they developed the “Fair Trade Travel Holidays”, which are like package tours and support the integration of certified businesses into GVCs. During FTT Holidays, at least 50% of the nights must be spent in FTT-certified businesses (FTT 2016). Currently, 58 national and international FTT approved tour operators transformed their GVCs by replacing non-certified accommodation providers by FTT-certified ones to be able to offer Fair Trade Holidays. In this way, the FTT-organisation’s DC supplemented and leveraged the DC of the certified businesses and promoted their GVC integration.

Social and economic upgrading - an outcomes-based perspective

Building and exploiting DC led to social and economic upgrading outcomes and changing GVC configurations of FTT-certified businesses (summarised in ). Additionally, revamped operational capabilities increased the liability and accountability of the certified businesses. Most FTT-certified businesses found that the FTT-label and marketing activities improved their credibility, and market visibility and eased access to GVCs where national and international tour operators focus on sustainable tourism (Interview 2009; rural and urban hotel; Interview 2013; urban backpackers). Furthermore, certified businesses referred customers to one another and, where possible, integrated each other into their respective value chains. Most certified businesses felt that FTT-certification meant they were preferred and, therefore, received more bookings through national and international tour operators who focus on sustainable tourism (Interview 2009 & 2013, urban activity providers). This perception aligns with statements of interviewed international and local tour operators (Interviews 2015 & 2016, international tour operators). Furthermore, certified businesses exploited DC to drive innovation, which increased their competitive advantage and promoted both social and economic upgrading. Empirical insights showed that the simultaneity of production and consumption in tourism, with many interaction processes between customers and staff, meant social upgrading was closely interrelated with economic upgrading. One manager explained:

“If you look after the employees and you ensure that they are fairly treated, you’ll have people who will give the best service because they are well looked after.” (Interview 2009, urban hotel 1)

As opposed to manufacturing, quality employment and empowerment of workers in the sustainable tourism sector seemed to positively influence service quality and customer satisfaction. New operational routines also had an impact at the community level (see ) and community activities often provided a USP for the certified businesses which, in turn, led to economic upgrading. For example, the guests of the rural backpacker hostels often extended their stays to participate in the community projects (Interviews 2014, rural backpackers).

Discussion

The findings illustrate how sustainability standards, combined with the agency and commitment of FTT-certified businesses, were decisive in promoting capability building and upgrading within FTT-certified businesses, their value chains, and the communities in which they were embedded. The empirical findings add novel insights to existing GVC upgrading research:

The categories of sensing, learning, integrating and coordinating (see ) helped to investigate how the FTT-organisation supported DC building at the firm-level. It revealed that the FTT-organisation pro-actively promoted the DC of sensing and learning through facilitating access to market intelligence, promoting community engagement, and initiated intra- and inter-organisational learning processes. Conversely, the DC of integrating and coordinating were mainly driven by the certified business, during the process of meeting targets set by FTT-standard requirements and through goal setting in the consulting process. The FTT-organisation was not actively involved in driving these processes because associated routines had to be adapted to individual firms and local context conditions. These insights confirm and enrich De Marchi et al. (Citation2013) findings that both a standards-driven and a mentoring-driven approach are necessary to promote more sustainable business practices in value chains.

Empirical insights also provide answers to Morrison et al. (Citation2008)’s call for more upgrading research with a dynamic approach and reveal the context and time dependency as important dimensions when analysing upgrading in GVCs. Context dependency resulted in different perceptions regarding the degree of change at a business level and depended on an existing resource base and the capabilities of individual organisations. Similarly, the FTT-standard facilitated different change processes at various points in time and at different speeds and, accordingly, the impacts of the standard implementation can be intangible, often hard to grasp and evolve over different periods of time. This emphasizes the time dependency of upgrading which has not yet been thoroughly explored in GVC research. Moreover, although learning processes mostly evolved while organisations prepared for the assessment and within first three years of standard implementation (between the first and second assessment), there there was no guarantee that the processes of learning and restructuring organisational routines would translate into visible social or economic upgrading outcomes, such as job promotions. Thus, difficulties remain in measuring or quantifying the benefits of the standard implementation as a driver for upgrading outcomes (Barrientos et al., Citation2011). These issues have received limited attention in the research on the impacts of the implementation of standards and could explain why mixed results have been observed empirically. A combination of a process-based and an outcomes-based perspective, to analyse upgrading, was, therefore, valuable to understand how sustainability standards can promote capability building and social upgrading in tourism GVCs.

Furthermore, as proposed in , the findings confirm that processes of building and exploiting DC and associated upgrading outcomes were interrelated with changing GVC configurations. From an actors-based perspective, the empirical findings illustrate that some actors, for example, tourism entrepreneurs or local suppliers, gained access to the value chains of FTT-certified businesses. Many FTT-certified businesses were also included in the GVCs of international tour operators after certification. In the case of volunteer tourism, FTT-certified businesses created new GVCs that had not existed before. Furthermore, through FTT Holidays, national and international tour operators pro-actively transformed their value chains and replaced non-certified accommodation providers with FTT-certified businesses.

Conclusion

Although GVC researchers have emphasized the importance of firm-level capabilities, the literature on capability building in GVCs is still limited. This contribution addresses the research gap by integrating the DC approach into GVCs research. To do so, it distinguishes between operational capabilities and DCs and shows how the underlying processes of building and exploiting DCs can concomitantly lead to social and economic upgrading in GVCs and affect GVC configurations. Thus, it advances current conceptualisations of capabilities within GVC research and provides a more nuanced distinction of different types of innovation capabilities (Lema et al., Citation2018).

In addition to this theoretical contribution, the paper also provides new empirical insights on how standard setting organisations, such as the FTT-organisation, can provide more than the development of sustainability standards and certification. The FTT-organisation and the FTT-standard implementation facilitated capability building and social upgrading through coaching and mentoring by FTT-assessors, and initiated peer-learning between certified businesses as well as changes in procurement practices of the certified businesses. These processes facilitated wide-reaching, gradual organisational and institutional change in tourism businesses, their value chains and their local environments.

For policy makers and practitioners, the empirical findings underline the importance of local sustainability standard setting organisations when helping businesses to build and exploit DC. These are necessary to become and remain competitive in the market but also to promote social upgrading and address societal challenges in innovative ways. Therefore, providing resources for intermediary organisations, such as the FTT-organisation, could contribute to gradually creating a more inclusive tourism industry in South Africa and other countries where the tourism industry is still characterised by path-dependent inequalities.

Even though the scope of this study is limited to one sector and geographical context, the conceptual approach and empirical insights are likely to have wider relevance due to the importance of tourism in many countries in the Global South (Daly & Gereffi, Citation2017). Based on the findings of this paper, future comparative research could investigate the interrelations between DC building and firm-level upgrading in other sectors and contexts. Moreover, because upgrading research currently focuses on outcomes, more research is needed that analyses micro-level processes of upgrading and the agency of local actors in shaping these processes.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the four reviewers for their very valuable and constructive engagement with the paper, the editors for their helpful guidance, and all participants who gave up their precious time. I would also like to thank Simone Strambach at the University of Marburg, Peter Lund-Thomsen at Copenhagen Business School, Shane Godfrey at the University of Cape Town and Khalid Nadvi at the University of Manchester for providing important and generous comments to earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annika Surmeier

Annika Surmeier has been awarded a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Global Fellowship and currently works at the University of Manchester, UK and the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Notes

1 The distinction between global North and South is not a strictly geographical categorisation. It refers to global inequalities in the distribution of wealth and power and interdependencies between developed and developing countries (Horner & Carmody, Citation2020).

2 A cognate body of research on Global Production Networks (GPNs) was developed mainly in economic geography (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015). While the GVC research focuses on vertical linkages between actors, the GPN framework pays equal attention to non-firm actors and the broader environment in which value-adding activities are embedded. This paper, however, applies a GVC framework as dynamics of upgrading are central to the analysis in this paper and have mainly been studied within GVC research.

3 FTT standard requirements were adjusted over time and now include comprehensive environmental requirements. During the data collection, however, environmental criteria were weak and, therefore, not included in the analysis.

4 The numbers in the upgrading section indicate how many businesses perceived the listed upgrading outcome.

5 In the South African context, the word ‘backpacker’ is used to describe budget accommodation. In this paper, the word backpacker refers to an organisation and not a person.

References

- Bair, J. (2017). Labor administration and inspection in Post-Rana Plaza Bangladesh. International Labor Rights Case Law Journal, 3(3), 457–462.

- Barney, J. B. (2000). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. In Economics meets sociology in strategic management (pp. 203–227). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Barrientos, S. W., & Smith, S. (2007). Do workers benefit from ethical trade? Assessing codes of labour practice in global production system. Third World Quarterly, 28(4), 713–729.

- Barrientos, S., Gereffi, G., & Rossi, A. (2011). Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. International Labour Review, 150(3-4), 319–340.

- Becker, M. C. (2004). Organisational routines: A review of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13(4), 643–678. DOI: 10.1093/icc/dth026.

- Blažek, J. (2016). Towards a typology of repositioning strategies of GVC/GPN suppliers: The case of functional upgrading and downgrading. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(4), 849–869.

- Breznik, L., & Hisrich, D. R. (2014). Dynamic Capabilities vs. innovation Capability: Are They Related? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(3), 368–384.

- Camisón, C., & Monfort-Mir, V. M. (2012). Measuring innovation in tourism from the Schumpeterian and the dynamic-capabilities perspectives. Tourism Management, 33(4), 776–789.

- Christian, M. (2012). Economic and social up(down)grading in tourism global production networks: findings from Kenya and Uganda. Capturing the Gains. (Working paper 11). University of Manchester. DOI: 978-1-907247-89-7.

- Christian, M. (2016a). Tourism global production networks and uneven social upgrading in Kenya and Uganda. Tourism Geographies, 18(1), 38–58.

- Christian, M. (2016b). Kenya’s tourist industry and global production networks: Gender, race and inequality. Global Networks, 16(1), 25–44.

- Christian, M. (2017). Protecting tourism labor? Sustainable labels and private governance. GeoJournal, 82(4), 805–821.

- Cockburn-Wootten, C. (2012). Critically unpacking professionalism in hospitality: Knowledge, meaningful work and dignity. Hospitality & Society, 2(2), 215–230.

- Coe, N. M., & Hess, M. (2013). Global production networks, labour and development. Geoforum, 44, 4–9.

- Coe, N. M., & Yeung, H. W. C. (2015). Global production networks: Theorizing economic development in an interconnected world. Oxford University Press.

- Corner, P. D., & Kearins, K. (2018). Scaling-up social enterprises: The effects of geographic context. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–19.

- Daly, J., & Gereffi, G. (2017). Tourism global value chains and Africa. Industries without Smokestacks, 68, 1–25.

- De Beer, A., Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2014). Decent work in the South African tourism industry: Evidence from tourist guides. Urban Forum, 25(1), 89–103.

- Denicolai, S., Cioccarelli, G., & Zucchella, A. (2010). Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence. Tourism Management, 31(2), 260–266.

- Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT). (1996). White paper on the development and promotion of tourism in South Africa. Retrieved February 02, 2018, from http://responsiblecapetown.co.za/tools/Document-Library/

- De Marchi, V., Di Maria, E., & Ponte, S. (2013). The greening of global value chains: Insights from the furniture industry. Competition & Change, 17(4), 299–318.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10-11), 1105–1121.

- Fair Trade Tourism. (2018). Annual Report 2017/18. http://www.fairtrade.travel/source/websites/fairtrade/documents/OCTOBER-2018.pdf

- Font, X., & Harris, C. (2004). Rethinking standards from green to sustainable. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 986–1007.

- Font, X. (2013). Sustainable tourism certification. In A. Holden and D. Fennell (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of tourism and the environment. Routledge.

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. 805. doi:10.1080/09692290500049

- Hansen, U. E., Fold, N., & Hansen, T. (2016). Upgrading to lead firm position via international acquisition: Learning from the global biomass power plant industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(1), 131–153.

- Helfat, C. E., & Winter, S. G. (2011). Untangling dynamic and operational capabilities: Strategy for the (n)ever‐changing world. Strategic Management Journal, 32(11), 1243–1250.

- Horner, R., & Carmody, P. (2020). Global North/South. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of Human Geography (pp.181–187). Elsevier.

- Horner, R., & Nadvi, K. (2018). Global value chains and the rise of the Global South: Unpacking twenty‐first century polycentric trade. Global Networks, 18(2), 207–237.

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. DOI: 10.1080/0034340022000022198.

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2004). Chain governance and upgrading: Taking stock. In H. Schmitz (Ed.), Local Enterprises in the Global Economy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- International Labour Organisation. (1999). Report of the Director-General: Decent work [Paper presentation]. International Labour Conference, 87th, Geneva. Retrieved February 02, 2018, from http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm

- International Labour Organisation. (2010). Development and challenges in the hospitality and tourism sector. ILO. Retrieved February 02, 2018, from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_166938.pdf

- International Trade Center. (2016). Standards Map. Retrieved April 21, 2016, from http://www.standardsmap.org/review.aspx?standards=202

- Kadarusman, Y., & Nadvi, K. (2013). Competitiveness and technological upgrading in global value chains: Evidence from the Indonesian electronics and garment sectors. European Planning Studies, 21(7), 1007–1028.

- Koelble, T. (2011). Ecology, economy and empowerment: Eco-tourism and the game lodge industry in South Africa. Business & Politics, 13(1), 1–24. doi:10.2202/1469-3569.1333

- Ladkin, A. (2011). Exploring tourism labor. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1135–1155.

- Lema, R., Rabellotti, R., & Sampath, P. G. (2018). Innovation trajectories in developing countries: Co-evolution of global value chains and innovation systems. The European Journal of Development Research, 30(3), 345–363.

- Locke, R. M. (2013). The promise and limits of private power: Promoting labor standards in a global economy. Cambridge University Press.

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Social Science Open Access Repository. Retrieved February 02, 2018, from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- Milberg, W., & Winkler, D. (2011). Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: Problems of theory and measurement. International Labour Review, 150(3-4)‐, 341–365.

- Morrison, A., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2008). Global value chains and technological capabilities: A framework to study learning and innovation in developing countries. Oxford Development Studies, 36(1), 39–58.

- Nadvi, K. (2008). Global standards, global governance and the organisation of global value chains. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(3), 323–343.

- Nadvi, K. (2014). Rising powers” and labour and environmental standards. Oxford Development Studies, 42(2), 137–150. 10.1080/13600818.2014.909400.

- Nadvi, K., & Wältring, F. (2004). Making sense of global standard. In H. Schmitz (Ed.), Local enterprises in the global economy. Issues of governance and upgrading (pp. 53–94). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Nieves, J., & Haller, S. (2014). Building dynamic capabilities through knowledge resources. Tourism Management, 40, 224–232.

- Nooteboom, B. (2010). A cognitive theory of the firm: Learning, governance and dynamic capabilities. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pavlou, P. A., & El Sawy, O. A. (2011). Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decision Sciences, 42(1), 239–273.

- Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2011). Global value chains meet innovation systems: Are there learning opportunities for developing countries? World Development, 39(7), 1261–1269.

- Ponte, S., & Cheyns, E. (2013). Voluntary standards, expert knowledge and the governance of sustainability networks. Global Networks, 13(4), 459–477.

- Ponte, S., & Ewert, J. (2009). Which way is “up” in upgrading? Trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine. World Development, 37(10), 1637–1650.

- Robinson, R. N., Martins, A., Solnet, D., & Baum, T. (2019). Sustaining precarity: Critically examining tourism and employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1008–1025.

- Rossi, A. (2013). Does economic upgrading lead to social upgrading in global production networks? World Development, 46, 223–233.

- Schmitz, H. (2007). Transitions and trajectories in the build‐up of innovation capabilities: Insights from the global value chain approach. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 15(2), 151–160.

- Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities. Sage Publications.

- South African Tourism. (2008). The marketing tourism growth strategy for South Africa 2008–2010. Retrieved December 11, 2012, from www.southafrica.net/uploads/legacy/1/287886/The Marketing TGS 2008 to 2010_v2_30042008.pdf

- Staritz, C., Whitfield, L., Melese, A. T., Mulangu, F. M. (2017). What is required for African-owned firms to enter new export sectors? Conceptualizing technological capabilities within global value chains. Working Paper.

- Strambach, S. (2017). Combining knowledge bases in transnational sustainability innovation: microdynamics and institutional change. Economic Geography, 93(5), 500–526.

- Strambach, S., & Surmeier, A. (2013). Knowledge dynamics in setting sustainable standards in tourism–the case of ‘Fair Trade in Tourism South Africa’. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(7-8), 736–752.

- Strambach, S., & Surmeier, A. (2018). From standard takers to standard makers? The role of knowledge‐intensive intermediaries in setting global sustainability standards. Global Networks, 18(2), 352–373.

- Tashman, P., & Marano, V. (2009). Dynamic capabilities and base of the pyramid business strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(S4), 495–514.

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350.

- Teece, D. J. (2012). Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus entrepreneurial action. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1395–1401.

- Winchenbach, A., Hanna, P., & Miller, G. (2019). Rethinking decent work: The value of dignity in tourism employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 0(0), 1–18. 10.1080/09669582.2019.1566346.

- World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). (2014). Travel & tourism—economic impact 2014 South Africa. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic%20impact%20research/regional%20reports/africa2014.pdf

- Zahra, S. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917–955.