Abstract

The trend of private interest groups influencing governance processes has recently gained prominence in the urban tourism domain, along with a strong increase in resident protests against the tourism sector and policy in many urban destinations worldwide. However, governance of tourism studies have so far paid only marginal attention to protests taking place ‘outside’ the formal governance arena. Moreover, relatively limited attention has been paid to large and mature urban destinations – often with more complex institutional bodies and a wider variety of stakeholders involved in tourism governance. Our article aims to understand why and how resident protests and contestation continue intensively in the city of Barcelona, despite formal governance channels and mechanisms created to facilitate and encourage resident participation. Taking the strategic action field perspective reveals that residents, as challengers, continue with protest and contestation because they perceive a threat from mass tourism, a bias in the political agenda and a risk of losing their autonomy. The main modes of protest used are gatherings in public spaces, promoting debate, providing information and extending the network. To advance their interests, challengers use protest and participation in a strategically dynamic way – i.e. they protest to empower participation and participate to empower protest.

Introduction

During the past decade, Barcelona has experienced a strong and persistent increase in the volume of tourists it receives, with the number staying in hotels rising from 1.7 million in 1990 to nearly 9.5 million in 2019 (Statista, Citation2020). The tourist flow towards the city has grown in recent years due to a combination of various factors, such as a wide offer of low-cost flights plus the accommodation opportunities provided by online platforms like Airbnb. Another important explanatory factor for the ‘success’ of Barcelona can be found in the marketing of its rich heritage. In so doing, the city was re-imagined and promoted as a ‘brand’ for tourists by the municipal government in collaboration with private interest groups (Cuadrado & Monedero, Citation2016; Smith, Citation2005).

Large and growing numbers of tourists have also been witnessed in many other cities across Europe, such as Venice, Amsterdam and Berlin, as well as beyond, in New Orleans, Hong Kong and elsewhere (Minoia, Citation2017; Pinkster & Boterman, Citation2017; Xing et al., Citation2020). In these and many other urban tourism destinations, the mobilisation of residents against the tourism sector and policy has gained prominence during the last couple of years. This is occurring to such an extent that it strongly questions the roles and duties of public decision-makers and the involvement of private interest groups in the development of tourism policy (Novy & Colomb, Citation2017). In this context, the so-called ‘Barcelona brand’ is increasingly being criticised for mainly fostering the interests of the private sector, deepening tourism impacts on neighbourhoods and as a rule relegating the needs of residents (Fava & Rubio, Citation2017).

Protests against the tourism sector and policy started in the late 1990s and reached a critical point in the neighbourhood of La Barceloneta in 2014. In this context, the Neighbourhoods’ Assembly for Tourism Degrowth (ABDT in Catalan) – a platform of grassroots movements and neighbourhood associations – was created and organised many mobilisations. The platform is calling for sustainable ‘degrowth for liveability’ in Barcelona, with the aim of improving residents’ living conditions and well-being, reducing the number of flights to and the number of tourists in the city and preventing the “proliferation of unmanageable and unsustainable tourism flows” in general (Milano et al., Citation2019, p. 1859). As a response to the many mobilisations and protests, the Advisory Council on Tourism and the City (CTiC in Catalan) was created by the municipal government in 2016 with the overall aim of fostering more sustainable development of urban tourism by means of a dialogue among and involvement by a wide variety of stakeholders in tourism governance. The specific intention was to facilitate and encourage participation by the local community in the governance of tourism in Barcelona. Since then, however, resident protests in the streets, online activism and debates contesting tourism policy ‘outside’ governance institutions have continued to take place in several neighbourhoods, and have sometimes even become more intense. Recently, however, the protests and contestations came to a sudden halt due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown measures enforced in Barcelona (La Moncloa, Citation2020).

Academic governance of tourism studies, focusing on protest and participation in particular, have two important limitations. Firstly, their general assumption seems to be that stakeholders – including municipal governments, the private sector and civil society organisations – will participate in tourism policy development, or at least be willing to establish a dialogue and seek consensus. As such, protests taking place ‘outside’ formal governance mechanisms and channels have been researched only marginally, although academic interest does seem to be gaining momentum (Cócola-Gant & Pardo, Citation2017; Milano et al., Citation2019; Novy & Colomb, Citation2017; Sequera & Nofre, Citation2019). Secondly, governance of tourism studies focus mainly on the national level (Conceição et al., Citation2019; Scott & Marzano, Citation2015) or on smaller settlements at the local level – including towns and villages (Beaumont & Dredge, Citation2010, Sawatsuk et al., Citation2018), natural and coastal areas (Presenza et al., Citation2013; Qian et al., Citation2016) and rural areas in developing countries (Adiyia et al., Citation2015) – as tourism destinations. As such, there is a relative lack of attention for large and mature urban tourism destinations – often with more complex institutional bodies and a wider variety of stakeholders involved in tourism governance. This article aims to enrich governance of tourism studies by developing an understanding of why and how resident protest and contestation continue intensively in the city of Barcelona, despite the CTiC created by the municipal government to facilitate and encourage participation in the governance of tourism. The strategic action field (SAF) framework (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011) is adopted as our perspective, providing us with a conceptual lens to analyse and pay particular attention to the influence residents may have on, and the roles they may acquire in, the governance of tourism.

The article is structured as follows. In the next section we build a theoretical framework based on governance of tourism studies (including recent studies on resident protests in urban tourism destinations), urban social movements studies and the SAF framework. We then present our research design and the methods, before presenting our results. The article concludes by summarising and discussing our main results, as well as providing suggestions for future research.

Protest and participation in the governance of tourism

Governance of tourism

Governance of tourism can be understood as a regionally and locally embedded relationship between stakeholders “who are engaged in planning, managing and controlling the tourism activity” (Oliveira, 2014, in Conceição et al., Citation2019, p. 2). Governance of tourism studies usually assume implicitly that the relationship between these stakeholders – including the municipal government, but also various private interest groups and civil society organisations – are based on trust and involves collaboration and co-operation (Damayanti et al., Citation2019; González-Morales et al., Citation2016). As a consequence, until recently governance of tourism studies tended to remain rather “exploratory and descriptive” (Beaumont & Dredge, Citation2010) when it came to contestation, protest and the related power play. This despite the recognition that actors not only co-operate but also compete, and that power relationships are of particular relevance in understanding governance of tourism processes (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2011).

Overcoming this analytical limitation has become all the more pertinent with the growth of resident contestation and protests in many tourism destinations worldwide. Residents should be acknowledged as a relevant group of stakeholders, alongside the municipal government and the private sector, in the formulation and implementation of tourism policy – as Moscardo (Citation2011) and Presenza et al. (Citation2013) also argued.

Resident protests in urban tourism destinations

Governance of tourism studies have so far paid only marginal attention to contestation and protest taking place outside formal governance mechanisms and channels, although coverage of the mobilisation of residents against the tourism sector and policy is gaining momentum. The compilation by Novy and Colomb (Citation2017), for instance, includes a variety of analyses of tensions and contestations in large and mature tourist cities across Europe and beyond – such as Prague, Berlin, Paris and Hong Kong. Several other recent studies have focused on analysing resident mobilisations against cruise-ship tourism in Venice (Seraphin et al., Citation2018) and rising discontent amongst residents living in Amsterdam city centre (Pinkster & Boterman, Citation2017), as well as anti-tourism mobilisation and urban activism in Madrid (Cabrerizo et al., Citation2016; Sequera & Nofre, Citation2019).

Some studies zoom in on resident protests in Barcelona. According to Cócola-Gant and Pardo (Citation2017) in their examination of tourism-led gentrification in Barcelona, protests started at the end of the 1990s as a response to urban policy in which tourists’ necessities were prioritised over residents’ needs. After the economic crisis in 2008, the mobilisations intensified as residents started to ‘rebel’ against new policy implemented to further increase the number of tourists. In this context, some studies have focused on analysing resident protests in specific parts of the city, especially the neighbourhoods of La Barceloneta (Boer & De Vries, Citation2009) and Gràcia (Arias-Sans & Russo, Citation2017). Milano et al. (Citation2019) add an analysis of social movements arguing for a shift in Barcelona from a “simplistic economic growth-oriented approach, to one that encourages tourism degrowth … rooted in protection of local resident quality of life and well-being” (p. 1858). Building on this emerging debate on resident protests in urban tourism destinations, our article aims to enrich governance of tourism studies by deepening understanding of resident contestation and protest from an SAF perspective.

A strategic action field perspective

Contestation, co-operation and urban social movements

The strategic action field (SAF) framework was proposed by Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011) with the aim of integrating notions of mobilisation and contestation into organisational studies. The reason for this was that they found that these studies take consensus and co-operation for granted, while marginalising contestation and protest. Since our findings and consequent aim for governance of tourism studies in this article are largely similar, we have borrowed the notions of contestation and co-operation from the SAF framework for use as a conceptual lens to analyse protest and participation in the governance of tourism.

The SAF framework is particularly helpful for our endeavours because it stresses both the agency of actors operating in a field – e.g. the governance of urban tourism – and the dynamics of the field itself. Due to a crisis, for instance (Richter et al., Citation2020). As such, social structures are not considered fixed but are seen as being produced and reproduced by actors based on collective interests (Moulton & Sandfort, Citation2017). Investigating the agency of actors is essential for our study since we aim to understand the influence residents have and the roles they acquire through protest and participation in the governance of tourism. In addition, taking field dynamics into account is essential since the creation of the CTiC represents a significant change in the governance field in Barcelona, implemented to solve a crisis situation in terms of resident protests. For the purpose of this article, the SAF perspective will be specified in the next section, by drawing on recently available studies of resident protests in urban mass-tourism destinations, complemented with more widely available urban social movements studies.

According to Silver et al. (Citation2010), contestation on the one hand and co-operation – in formal institutions established by the municipal government – on the other can complement one another. Both occur in “different political phases of policymaking, implementation and monitoring” (p. 453) and through a dynamic “cycle of contestation and consensus”. So, participation by social movements in urban governance may involve contestation and co-operation, as these “are both legitimate and mutually reinforcing forms of participation” (Aylett in Silver et al., Citation2010, p. 470). Moreover, contestation and co-operation can also take place when participating ‘inside’ formal governance institutions. Such participation can be understood as “direct involvement – or indirect involvement through representatives – of concerned stakeholders in decision-making about policies, plans or programs” (Quick & Bryson, Citation2016, p. 158). It may range, for instance, from residents being consulted through public hearings and being engaged in advisory councils to taking part in decision-making processes (Arnstein, Citation1969). And, as already stated, they also involve contestation.

Contestation can also take place ‘outside’ the formal governance arena, through protests in particular. Such protests can be understood as “collective action aimed at achieving significant social or personal change opposed to central institutions” (Lofland, Citation2017, p. 24). They involve human gatherings and media campaigns, taking place over a shorter or longer period, in the form of events such as demonstrations and forums and employing both offline and online media. The argument that co-operation and contestation, including protests, are related and may also strengthen one another is supported by Groth and Corijn (Citation2005). They argue that creating coalitions is the way “that an agenda-setting is obtained, that the informal actors become players in the public debate” (p. 521) as well as the way that capacities to protest and negotiate are built. At the same time, however, there may be a lack of consensus within a social movement resulting in fragmentation due to conflicts between individual and collective interests (Özdemir & Eraydin, Citation2017).

With respect to participation by residents in urban governance, Blakeley (Citation2010) cautions that it does not necessarily imply their empowerment in the sense that their interests are actually being taken into account by the decision-makers. Moreover, mechanisms and channels to facilitate and encourage participation by residents may be instrumental for municipal governments in providing a counterweight to private-sector interests, but resident participation may also provide a means to demobilise social movements and to defuse contestation and protest (Silver et al., Citation2010). When social movements are co-opted into formal governance institutions and processes, they may not only be manipulated by politicians but their character can also change in a more ‘subtle’ manner. They may, for instance, lessen their critical approach, adjust their agenda, adapt their language and lose their autonomous position outside policy arenas – becoming a ‘hostage’ of the municipal government (Blakeley, Citation2010; De Souza, Citation2006). As such, it seems that in order to guarantee the autonomy of social movements, their active protests outside formal mechanisms and channels as provided by the municipal government are a necessity (Silver et al., Citation2010).

Types of actors and sources of contestation

The SAF framework conceptualises a meso-level social order that recognises the existence of constellations of actors with much and little power. It recognises two types of actors. Incumbents are the powerful actors who dominate the field, such as the municipal government and the private sector. Challengers are non-powerful actors who are often non-institutionalised and therefore usually excluded from governance processes (Milano et al., Citation2019); they can include grassroots movements and civil society groups. In addition, the SAF framework considers governance units or institutions as formal entities established to facilitate and guarantee a well-functioning system. “Ordinarily, … [these] governance units can be expected to serve as defenders of the status quo and are a generally conservative force during periods of conflict within the SAF” (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011, p. 6).

The SAF framework aims to explain how grassroots movements and other groups or collectives of actors with relatively little power can still exert influence in a ‘field’ – i.e. through a process of contestation. This process “typically starts with at least one collective actor defining some change in the field or external environment as constituting a significant new threat to, or opportunity for, the realization of group interests” (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011, p. 9). According to Mayer (Citation2007), in recent decades resident protests in Western cities have often focused on the contestation of neoliberal growth policies for city centres, developed to participate in the inter-urban competition for international tourists and their spending power. Cócola-Gant and Pardo (Citation2017) add that residents protest because they perceive tourism as a threat to their daily environment and way of life, and also as intensifying potentially related phenomena, such as evictions and gentrification, in specific neighbourhoods. This resonates with two of the main sources of contestation by residents as mentioned by Novy and Colomb (Citation2017). These are related to (1) “negative effects and externalities caused by tourism on people and places” (p. 18) and (2) often very unequal “equity impacts – i.e. the distribution of the costs and benefits of urban tourism among various groups and spaces” (p. 18). They also mention a third main source of contestation related to urban tourism policy: that residents perceive a bias in the political agenda in favour of the ‘visitor class’ or tourism sector.

Mobilisations and destabilisations

When a change in the field is perceived as a threat to and/or opportunity for group-interest realisation, Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011) argue that “it is not enough for some subset of individuals to define the situation in this way” (p. 9). Resonating with Castells’ argument that social movements operate through “purposive social actions” (Citation1983, p. xv), Fligstein and McAdam continue by saying that challengers “perceiving the threat/opportunity must also command the organizational resources needed to mobilize and sustain action in the face of the ‘threat’ or ‘opportunity’” (p. 9). And “finally, contention depends on actors violating field rules with respect to acceptable practices and engaging in ‘innovative action’ in defense or support of group interests” (p. 9). In this context, Groth and Corijn (Citation2005) argue that the mobilisation of residents may result in a wide variety of challengers. They emerge from contestation based on the strategies or ‘innovative actions’ used – ranging from radical activism in the streets, e.g. demonstrations impeding the flow of tourists and immobilising tourist buses, to initiatives fostering a dialogue with institutionalised actors, and from temporary to more durable collaborations or even institutionalised associations. Parés et al. (Citation2012) stress the importance of geographical context for the influence resident mobilisations and strategies may have in articulating their demands, and for the prominence of resident participation and co-operation in urban governance. Both the influence of mobilisations and the prominence of participation seem to depend on the context of the neighbourhood where the residents live.

According to the SAF framework, changes in the external environment – such as a strong growth in the number of tourists flocking into cities – can destabilise the power structure of the field. In that case, ‘innovative actions’ by challengers result in episodes of contestation – i.e. periods of emergent and strengthened contentious interaction between actors. Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011) argue that ‘destabilisations’ can be solved in three ways. Firstly, when incumbents restore themselves by creating alliances with other incumbents or by mobilising governance units and institutions. They may also give concessions to one or more of the challengers and perhaps even integrate them in the dominant coalition. Secondly, when governmental actors restore the status quo or change the structure. They can dismiss incumbents if they are substantially damaged due to the crisis, restructure the governance units or even convert particular challengers to incumbent status. And thirdly, when a real transformation occurs in the field due to one of the following factors: (a) an exogenous shock of unusual intensity; (b) defection of at least some incumbents and some or all external allies; or (c) united opposition by virtually all challengers.

Research design and methods

This study employed the qualitative methods of textual analysis, participant observations and in-depth interviews. A wide range and large number of textual materials related to urban tourism in Barcelona were collected, including policy documents, strategic plans, legal texts, minutes of council meetings, press releases, newspaper articles and website texts. In addition, extensive observations were performed, with notes taken of discussions and events, while attending in several meetings and forums organised by the ABDT. Extensive participatory observations were also undertaken ‘in the field’, by attending protests, to develop an understanding of how protests are organised and take place in Barcelona. In so doing, we focused in the neighbourhoods of El Gòtic, El Born, El Raval and Sagrada Família, as these are generally the areas with the largest tourist crowds and the deepest tourism impacts (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2017). The participatory observations of meetings, forums and protests were complemented by informal conversations with seven urban activists, notes of which were taken.

The political effervescence in Catalonia due to the independence movement and the Spanish government’s response, which was ongoing during the time of our fieldwork between October 2017 and July 2018, inevitably produced a challenge for the recruitment of interview respondents. Considering the situation, we managed to recruit a considerable number and variety of urban activists and experts participating in the CTiC. Thirteen in-depth interviews of high quality were conducted, which provided us with rich and detailed insights into how challengers operate and why they protest against and participate in the governance of tourism. We managed to recruit eight urban activists for interviews, aged between thirty-five and sixty. Five are male, three female. They represent a variety of grassroots movements and neighbourhood associations in Barcelona. These are the ABDT, several organisations belonging to or collaborating with it – i.e. Fem Plaça (‘We make the square’), Resístim al Gòtic (‘We are resisting in El Gòtic’), the El Barri Gòtic Neighbourhood Association, the Barcelona Federation of Neighbourhood Associations and Ciutat Vella No Està en Venda (‘The Old Town is not for sale’) – as well as the Barcelona Association of Neighbours and Hosts. In addition, we managed to recruit five academic experts for interviews. Together, they represent most of the disciplines active in the CTiC – i.e. anthropology, demography, sociology, geography and tourism.

The interview recordings were fully transcribed and, together with all textual materials collected, coded thematically for analysis. Five main themes related to the SAF framework, with a focus on resident protest and participation, emerged during the coding process and were used to structure the results section on the governance of tourism. These are: (1) incumbents and challengers; (2) challenger protest strategies; (3) the CTiC; (4) challenger participation strategies; and (5) motivations for protest and participation. Findings from the participatory observations were used to contextualise and illustrate the main themes presented in the results section of this article. Most of the textual materials were translated from Catalan into English, and all the quotes from the in-depth interviews were translated from Spanish into English.

The governance of tourism in Barcelona

Incumbents and challengers

The private sector constitutes an important part of the group of incumbents and is influential in the governance of tourism in Barcelona. More specifically, as an anthropologist put it, “For several years decisions regarding tourism [policy] were made by taking account of [tourism] businesses, the so-called ‘lobby’, but not residents.” The main incumbents are grouped in the Consorcio de Turisme de Barcelona (also known as Barcelona Turisme), a governance unit formed as a public-private partnership. This was created in 1993 as a consortium of the municipal government, the official Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Navigation and the Foundation for the Promotion of Barcelona. Currently, Barcelona Turisme remains in charge of the promotion of the city under the Barcelona brand (Barcelona Turisme, Citation2020).

Recently, however, the existence and authority of Barcelona Turisme has increasingly been questioned, not only by many social movements but also by the city administration itself. One factor explaining this shift is that citizen platform Barcelona en Comú (Barcelona in Common) – constituted by a number of grassroots movements and neighbourhood associations – won the local elections in 2015. Another is that the current city mayor, Ada Colau, used to be a challenger: before taking office, she was part of the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages, devoted primarily to contesting property speculation and resident evictions.

The group of challengers consists of neighbourhood associations and a variety of grassroots movements. After numerous anti-tourism demonstrations by residents in La Barceloneta in 2014, several grassroots movements started to collaborate and join forces to oppose the effects of tourist pressure on neighbourhoods. This culminated in the creation of the ABDT platform in 2015 (Cócola-Gant & Pardo, Citation2017), as the most important challenger protesting against tourist policy and the related ‘Barcelona brand’. It combines about 35 grassroots movements and neighbourhood associations, as well as the Barcelona Federation of Neighbourhood Associations.

Barcelona residents tend to hold memberships of more than one social movement. However, not all take an active part in these with the aim of protesting against the tourism sector and policy. The Barcelona Association of Neighbours and Hosts, for instance, is fighting for the right of its members to let out homes as tourist accommodation via online platforms, such as Airbnb.

In line with Parés et al. (Citation2012) on the importance of geographical context for resident participation in urban governance, most of the grassroots movements emerged in and are supported by neighbourhood associations from areas under the highest tourist pressure, such as El Barri Gòtic, La Barceloneta, Sagrada Família, Gràcia and El Raval. Moreover, the neighbourhood associations participating in the CTiC also represent the Barcelona neighbourhoods with the highest tourist pressure.

Challenger strategies: protests in the city

Resident protests against the tourism sector and policy started in the late 1990s, and many are now organised by the ABDT. In we present the main modes of protest, and the related strategies, used by challengers outside the formal governance arena in Barcelona.

Table 1. Main modes of tourism protest and related strategies in Barcelona.

Gatherings in public spaces

In line with Blanchet (Citation2015) and Lofland (Citation2017), strategies employed by challengers in Barcelona often involve human gatherings in public spaces – including street demonstrations and rallies in neighbourhoods under high tourist pressure and gatherings in front of specific buildings, usually the headquarters of incumbents and the offices of tourist services. These protest strategies are used to show discontent, to put pressure on incumbents and to attract media attention.

The strategy of street demonstrations is exemplified by the STOP#BúsTurístic (Stop the Tourist Bus) campaign, involving the blocking and immobilisation of tourist buses by groups of protesters at several locations across the city. A telling example of protests in front of offices took place on 25 October 2017. As can be established from the minutes of the CTiC plenary meeting held on 4 October 2017, at that gathering challengers co-ordinated efforts to contesting a decision by the Port Authority to develop a second terminal for cruise tourists, and so further increase their number in Barcelona. The meeting ended without resolution of the issue or any formal compromises by representatives of the municipal government. As a consequence, the ABDT organised a large gathering in front of the Port Authority offices in the World Trade Centre to protest against the second terminal. In addition, gatherings took place – with other goals – in front of a variety of buildings in the city, including the headquarters of Barcelona Turisme, under the hashtag #Foralobbies (Lobbies out!), and Hotel Rec Comtal in the district of Ciutat Vella.

Meetings with neighbours take place in public spaces considered seriously threatened by tourist pressure. ‘Vermut veïnal’ (‘drinks with neighbours’) gatherings, for instance, are organised by Fem Plaça and Ciutat Vella No Està en Venda. These protests not only involve meetings of neighbours living in the old city, but also informal exhibitions highlighting the effects of mass tourism in the district. Having meetings with drinks and snacks was chosen as a strategy to regain the public space for uses and activities by local residents (see ).

Figure 1. Neighbours meeting with drinks in El Born: “Let’s retake public space!”.

Source: Photograph by first author.

Challengers consider increasing rents – due to property speculation related to tourist accommodation and regeneration projects (Cócola-Gant & Pardo, Citation2017) – as one of the main negative impacts of tourism faced by residents in particular neighbourhoods. As a response, they mobilise groups of people to stop, or at least delay, evictions by blocking the entrances of housing blocks and immobilising the police. As an activist described it:

“When we know the cops are coming, it doesn’t matter whether we live in the same neighbourhood or not. It’s a question of solidarity and we want to show them [the police] that we will fight. We make it more difficult for them to kick out those families … Obviously, it’s not always successful and then the most we can do is delay things” (activist, Resístim al Gòtic).

Promoting debate and providing information

Challengers also try to raise attention for their interests and residents’ problems by promoting debate and providing information. The ABDT, for instance, organised international neighbours’ forums on mass tourism in 2016 and 2018. During both events, developments related to the tourism sector in several southern European cities were discussed critically. A variety of residents, activists from grassroots movements and academic and professional experts were invited as speakers. Smaller workshops and conferences have also been organised by the challengers. One example of a local event is a debate on the implications of business development districts for residential neighbourhoods, with a focus on the relationship between urban tourism and gentrification processes. A second focused on the benefits of promoting sustainable tourism in Barcelona.

Social media are widely used by challengers due to their extensive reach, together with the limited financial resources they require. Through Facebook and Twitter, the ABDT posts press releases, reacts to incumbents’ positions and to decisions made by the municipal government and denounces resident evictions and illegal tourist apartments. Social media posting is often used in combination with and to support other protest strategies. Before the gathering in front of Port Authority offices, for instance, the ABDT platform posted a press release with the hashtag #NovaTerminalNo (No to the new terminal) and supported by forty-five civil-society organisations, neighbourhood associations and grassroots movements as well as at least three hundred residents. Moreover, the platform maintains an online blog describing all activities undertaken by the activists and providing information about, as well as a detailed agenda of, upcoming activities.

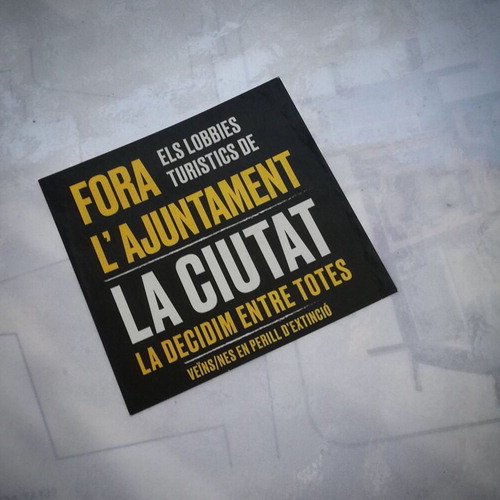

Putting banners on buildings and stickers on walls and street furniture (see ) is also frequently used as a protest strategy in ‘offline’ public spaces. This is done to reach a large audience, to raise awareness of tourism impacts and to create empathy for residents’ tourism-related problems – especially evictions.

Figure 2. Sticker on a wall in Ciutat Vella: “Tourism lobbies, leave City Hall. We decide. Neighbours in danger of extinction.”

Source: Photograph by first author.

Activists also produce and distribute magazines with articles – written by themselves and invited experts – discussing tourism impacts on Barcelona. Two of these are Marea Urbana and Masala, which only recently started to focus on discussing problems related to tourism in the city. Moreover, ABDT members have contributed to documentaries in order to gain more media attention and make the platform more ‘visible’. Two examples are the films Bye Bye Barcelona (Chibás Fernández, Citation2014) and City for Sale (Álvarez Soler, Citation2019), both visualising and discussing implications of mass tourism for the city.

To oppose tourism-led gentrification and resident displacement, both activists and legal consultants, working on a voluntary basis, provide legal advice and mental support to individuals or groups of residents facing eviction. Most evictions are due to renovation projects and the related property speculation, resulting in rising rents and the development of new tourist apartments. The grassroots movement Resístim al Gòtic was created with the specific aim of ‘fighting speculation’ in the Barri Gòtic, in the city centre.

Extending the network

The ABDT welcomes new members and allies to extend its network and to build a stronger coalition of challengers in Barcelona. The same is also being done at the European level since the creation in 2018 of the Network of South European Cities Facing Touristification (SET network), consisting of grassroots movements from twenty-five different cities in four countries. The ABDT is seeking to establish a stronger network together with other movements with similar interests and to share and learn from each other’s knowledge and experiences. The main aim of taking protest and contestation ‘beyond Barcelona’ is to put more pressure on the municipal government.

The Advisory Council on tourism and the city

As a response to resident protests reaching a critical point in La Barceloneta in 2014, the CTiC was announced by the municipal government in 2015 and formally constituted in 2016. This was done with the overall aim of fostering more sustainable development of tourism in Barcelona, by means of a dialogue among a wide variety of stakeholders in tourism governance. The specific intention was to facilitate and encourage participation by residents in tourism governance and, in so doing, to have their voices heard more and attention for their needs raised through formal governance channels and mechanisms.

Amongst other tasks, the CTiC advises the municipal government on tourism policy, proposes action to foster the sustainability of tourism, undertakes research on urban tourism developments and compiles an annual report monitoring the tourism situation in the city. Article 2 of its statute confirms the non-binding nature of its work:

“The functions of the Advisory Council on Tourism and the City are exercised through elaborating reports, opinions, proposals and suggestions which have the character of recommendations for the organs of the municipal government and are not, in any case, binding” (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2016).

The CTiC comprises a president, three vice-presidents, representatives of each political party in Barcelona, thirty-four representatives of diverse neighbourhood associations and of various social movements and organisations, as well as six municipal officials and three members of Barcelona Turisme consortium. In addition, twelve academic and professional experts from tourism and related disciplines – i.e. geography, anthropology, demography and economics – are invited to participate. shows the sixteen challengers – i.e. neighbourhood associations and other social movements and organisations – represented in the CTiC. The five neighbourhood associations plus the Barcelona Federation of Neighbourhood Associations are elected by the entities registered in the General File of Citizen Entities of the City Council of Barcelona. In addition, each district government in the city selects one movement or organisation to represent ‘social groups’ in its area (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2016).

Although the CTiC aims to include a wide variety of stakeholders in the debate, it is closed to residents who do not take part in any association, movement or organisation. Moreover, the ABDT is not directly represented because it is not a legally constituted entity but a grassroots movement. It is represented indirectly, however, through challengers affiliated to or collaborating with it (see ).

Table 2. Challengers in the CTiC and their relationship with the ABDT.

Challenger strategies: participation in the CTiC

When participating in the CTiC, communication between and the co-ordination of positions by challengers prior to plenary meetings are considered important strategies to negotiate a shared position. For instance, as can be ascertained from minutes of its plenary meetings, the neighbourhood associations belonging to the ABDT usually adopt the same position, use similar arguments and support each other.

Challengers also continuously seek to engage in dialogue with actors who might have similar positions, or at least are not incumbents. In so doing, they seek rapprochement with trade unions, environmental groups, social movements and organisations representing Barcelona’s districts and academic and professional experts. Contrary to what Blakeley (Citation2010) has suggested, participation by professionals – e.g. researchers and consultants with expertise in tourism and related disciplines – is not contested by the challengers. Instead, they try to find common ground with them and to gain their support in the CTiC working groups, in which topics related to the management of tourism are discussed. To some extent, arguments propounded by experts are used to legitimise and empower claims made by activists. As one expert explained:

“They know that we have evidence and more knowledge on some topics, and in that sense when we say something in the CTiC we usually have stronger arguments. Some of my colleagues have already worked with residents and I think the majority of us think in a similar way about the impact of tourism in the city” (demographer).

However, challengers are also reluctant to accept and co-operate with particular social movements and organisations. For instance, tensions often occur in the CTiC between the neighbourhood associations belonging to the ABDT and the Association of Neighbours and Hosts of Barcelona. The reason for this is that the latter is seen as backed by the private sector and supportive of economic interests (related to online tourist accommodation platforms, in particular) while pretending to be a social movement.

Moreover, activists define and defend their position through open confrontation within the CTiC. A telling example can be found in what happened at one of its first meetings, in November 2016, at which a representative of Barcelona Turisme presented the work done by this consortium and emphasised the importance of continuing to promote the city as a tourist destination. After the presentation, the representatives of the El Barri Gòtic Neighbourhood Association and the Sagrada Família Neighbourhood Association openly criticised the objective of attracting more tourists “without considering the current situation” in the city, with its many negative impacts in neighbourhoods. By means of these actions – with the ABDT represented indirectly in the CTiC by both neighbourhood associations, amongst others – this platform pushed for a “more integral and social vision” as opposed to the focus on economic performance by Barcelona Turisme. In so doing, the ABDT established its status in the CTiC as a grassroots movement to be taken seriously, even though it operates outside the formal governance arena. As one activist put it:

“They [Barcelona Turisme] at least know now that we will question everything they say. They now have to meet us and discuss with us face-to-face, so it’s more difficult for them to do whatever they want” (activist, Barcelona Federation of Neighbourhood Associations).

Motivations for protest and participation

Three main motivations were found to be of importance to challengers, encouraging them to engage in and continue with contestation (when participating) and with protests outside the formal governance arena. These are the threat they perceive from mass tourism, the bias the perceive in the political agenda and a risk of losing autonomy. Interestingly enough, the Catalan independence movement was not seen by our interviewees as an element shaping motivations for protest against and the contestation of tourism.

Threat of mass tourism

This motivation confirms that ‘negative effects of tourism’ are an important source of resident discontent – as indicated by Novy and Colomb (Citation2017) – and also confirms that tourism and its effects are seen as a threat, which, according to Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011), is one of the key mechanisms shaping the process of contention. Protest slogans used by grassroots movements also clearly pinpoint tourism as a threat to cities and their neighbourhoods – e.g. “Tourists go home! You’re killing the city” and “Neighbours in dangers of extinction”. Residents perceive the threat as particularly acute for their everyday environment and way of life (Cócola-Gant & Pardo, Citation2017). They see neighbourhoods changing in order to fulfil tourists’ expectations, often resulting in a loss of residents’ sense of belonging and also resentment towards tourists. As one activist put it:

“The neighbourhood is changing all the time … I can’t do anything here any more; everything is for tourists. Every new shop is one of those you can find here as well as in China, and now I have to do my groceries in other places because the old ones are closing down … I don’t know how long we’ll be able to hold out, it’s becoming more and more difficult. They [tourists] are everywhere” (activist, El Barri Gòtic Neighbourhood Association).

Residents may not only have to travel outside their neighbourhood to find proximity stores providing everyday goods and services to local residents – such as grocery stores, bakeries and restaurants – many also avoid public spaces they see as overcrowded with tourists. Moreover, mass tourism may induce gentrification processes, raising property values and rents in particular neighbourhoods. This results in higher profits for affluent property owners but also in the potential displacement and eviction of less affluent renters, intensifying socioeconomic problems in the city. Activists see protest and participation as a way to draw attention to these intensifying problems and protect neighbourhoods’ authenticity and vitality. This resonates with the argument made by Novy and Colomb (Citation2017) that uneven distribution of the costs and benefits of tourism among social groups and neighbourhood spaces across the city is an important source of resident discontent.

Bias in the political agenda

Prior to 2015, the municipal government and private interest groups had long co-operated to give preferential treatment to the needs of tourists and the tourism sector, at the expense of residents’ necessities and problems (Cócola-Gant & Pardo, Citation2017). This bias in the political agenda has been an important source of resident discontent, as also indicated by Novy and Colomb (Citation2017). Despite the creation of the CTiC and residents’ participation in this council, however, a ‘pro-tourist bias’ is still perceived. This is also apparent from protest slogans used by grassroots movements in the media as well as on stickers and banners – e.g. “A city to live in or a city to visit?” and “The city is for neighbours, not for tourists”.

The majority of activists admit that the current municipal government ‘is working harder’ than any of its predecessors to reduce tourist flows and to stop illegal tourist rentals. However, one interviewee added that “at the end of Colau’s administration, the number of tourists is [still] going to be higher than when she took office” (activist at Resístim al Gótic). This is explained by the argument that the so-called ‘tourism lobby’ led by private interest groups and Barcelona Turisme is too powerful to be counterbalanced by the municipal government alone. According to the activists, the government ‘wants but can’t’ due to the configuration of forces in the city council, with Barcelona en Comú holding a minority position. At the same time, the work done by the CTiC is not legally binding and the municipal government has limited powers and tools to actually manage tourist flows and mitigate tourism impacts. To assist in overcoming the ‘pro-tourist bias’, challengers consider it a necessity to continue with their contestation when participating in the CTiC as well as with their protests outside the formal governance arena. In so doing, they aim to increase pressure on the incumbents operating within the formal governance channels and mechanisms.

Risk of losing autonomy

In addition to protest and contestation, challengers also consider co-operation with the municipal government useful to advance their interests. The government, too, is open to co-operation in the sense that it seeks dialogue with challengers and even seems to ‘listen’ to them, at least to a certain extent. A telling example of this can be found in how the ‘tourism degrowth’ concept has come to be used in official policy documents. This was originally proposed by the ABDT with the intention of limiting the offering for tourists and, in so doing, also reducing tourist flows and improving the liveability of the city for its residents (Milano et al., Citation2019):

“For us, a new economic model for the city would be to reduce the [tourist] flows and offering … The [‘tourism degrowth’] concept has started to be used in some plans, although with a different idea. For us it is clear ‘wink’ from the municipal government, like they’re saying ‘we are listening to you’” (activist, ABDT).

The concept is in indeed now used in official documents such as the Special Urban Plan for Tourist Accommodation, intended to regulate new licences for the various types of tourist accommodation in Barcelona (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2017). However, whereas for the activists ‘tourism degrowth’ implies a new approach to the economy of the city as a whole, the municipal government uses the term to address particular parts of it only – i.e. the ones under the highest tourist pressure. In this case, therefore, the plan at best entails a stabilisation of tourist accommodation in the city, not degrowth.

This selective use of the ‘tourism degrowth’ concept by the municipal government illustrates what Silver et al. (Citation2010) describe as resident participation being instrumental for the interests of the municipal government – employing that participation as a counterweight to private interests. At the same time, however, participating through formal governance institutions may result in grassroots movements losing their autonomous position outside the governance arena, as argued by De Souza (Citation2006). Our interviewees also perceive and are concerned about the risk of losing autonomy. As one activist put it:

“They [the municipal government] always try to talk with us, to make us participate. They look at us constantly because we know that legitimises them, but also because we sometimes give them good ideas. Obviously, we want to keep the line ‘clear’, we want to keep our independence” (activist, Ciutat Vella No Està en Venda).

To maintain an independent and autonomous position in the CTiC, not only is contestation when participating considered important, but so too is being engaged in protests outside the formal governance arena – thus confirming the argument made by Silver et al. (Citation2010).

Conclusion and discussion

In the context of large and growing numbers of tourists and prominent resident mobilisations against the tourism sector and policy – with negative tourism impacts on neighbourhoods as important sources of contestation – this article has aimed to develop an understanding of why and how resident protest and contestation continue intensively in Barcelona, despite the CTiC created by the municipal government to facilitate and encourage resident participation. To do so, notions of contestation and co-operation have been borrowed from the SAF framework and used as a conceptual lens to analyse protest and participation in the governance of tourism.

A multiplicity of actors with diverse interests was found to participate in the governance of tourism in Barcelona as an urban destination. In accordance with Blakeley (Citation2010), the results reveal that participation by residents does not necessarily empower them, or at least not to an extent challengers are satisfied with. Despite the creation of the CTiC, with a substantial degree of resident participation, and a municipal government implementing measures to manage tourist flows and to mitigate negative tourism impacts, challengers still perceive a bias in the political agenda in favour of tourists over residents. This can be explained by the strength of the tourism lobby backed by private interest groups and Barcelona Turisme, combined with the non-binding nature of the work done by the CTiC and the limited powers and tools available to the municipal government to actually manage flows and mitigate effects related with urban tourism.

The twin perceptions that the political agenda is biased and that mass tourism poses a threat are important motivations for challengers to continue with protest and contestation. Both the perceived ‘threat’ – together with the uneven distribution of its effects – and the perceived ‘bias’ concur with the work done by Novy and Colomb (Citation2017) on sources of resident discontent in urban tourism destinations in general. Our study has contextualised and detailed these motivations for Barcelona in particular, and also pinpointed an additional motivation. Taking the SAF perspective has revealed that challengers perceive a risk of losing autonomy when only participating through formal governance channels and mechanisms, and so they also continue with their protests.

To achieve their goals when participating in the CTiC, challengers seek coalitions with other challengers and incumbents – ABDT members in particular, and also experts – whereas contention with challengers and incumbents also occurs, especially with the Association of Neighbours and Hosts of Barcelona and Barcelona Turisme. Challengers protest outside the formal governance arena, too, combining different modes of protest – i.e. gatherings in public spaces, promoting debate, providing information and extending the network – and using a variety of related strategies. Altogether, challengers engage strategically in a dynamic “cycle of contestation and consensus” (Silver et al., Citation2010) to advance their interests. Both contestation and consensus can be witnessed when challengers participate in the CTiC, but they are also actively involved in contestation by means of protests ‘outside’ it. This is done to become ‘visible’, to gain attention from and put pressure on incumbents in the CTiC and to add leverage to their ‘inside’ participation. Moreover, challengers’ participation and coalition building within the CTiC empowers and builds capacity for ‘outside’ protests (Groth & Corijn, Citation2005).

From the SAF perspective, the protests in La Barceloneta reaching a critical point in 2014 could be understood as a ‘first shock’ inducing a change to the structure of the field of tourism governance with the creation two years later by the municipal government of the CTiC. This change was also facilitated by a new city administration, installed in 2015 and with a mayor who used to be a challenger, questioning the authority of Barcelona Turisme. However, with the latter consortium still operational and the CTiC lacking the institutional power to dismiss and replace it, governance of the tourism field can be considered as remaining ‘under reconfiguration’ or even ‘destabilised’.

In such a situation, the SAF framework indicates that it is highly probable that challengers will continue with protests in order to gain incumbent status, to dismantle the former governance unit and to replace it with a new one closer to their own interests. This can indeed be witnessed in the case of Barcelona, and is also confirmed by the objective in the agenda of the ABDT to adopt a degrowth approach under which Barcelona Turisme is dismantled and replaced by a Public Agency for Tourism, with the main task of regulating rather than promoting urban tourism. Moreover, and contrasting with the argument made by Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011) that governments usually have close ties with the private sector and create coalitions with other, potentially new incumbents, this article has shown that when the field is in a reconfiguration stage, the government may also perform a role ‘in-between’ challengers and incumbents. In so doing, the government seeks to come closer to and build coalitions with the former rather than the latter, with the aim of maintaining and enhancing its legitimacy as well as empowering the newly created governance institution. This development of government-challenger coalitions is not only promising for the future liveability of Barcelona and the well-being of its residents, but also for the sustainability of other urban tourism destinations. With the recent COVID-19 pandemic as an ‘exogenous shock’, the field of tourism and its governance seems to have entered a stage of reconfiguration in many tourist cities, promoting the degrowth debate and pressure for more sustainable tourism, with greater attention for ‘the local’ and local people.

This article has addressed strategies and motivations for grassroots movements and neighbourhood associations to engage in protest and participation in the governance of tourism in Barcelona. In so doing, however, we have not paid any attention to the perspectives of the following three resident groups, which we think are of interest and relevance for future research. Firstly, radical movements of residents who are willing to use violence and reject any co-operation with the municipal government, particularly in the context of the independence movement and related political effervescence in Catalonia. Secondly, groups of residents who are in favour of current tourism policy and very much appreciate the right to let out their homes as tourist accommodation. And thirdly, ‘silently discontented’ residents who do not take part in any grassroots movement or neighbourhood association but engage in silent protest through ‘micro-politics’, such as avoidance strategies (Gravari-Barbas & Jacquot, Citation2017). Moreover, longitudinal analysis of the development of motivations and strategies for, and the influence of, resident participation and protest in Barcelona – in comparison with other urban tourism destinations, accounting for different and dynamic political contexts – is required to advance the debate around the governance of tourism. Finally, the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for the roles in and influence of resident participation and protest in tourism governance require investigation. This ‘exogenous shock’ has much potential to bring about a rethink and redesign of the tourist city, including its governance.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adiyia, B., Stoffelen, A., Jennes, B., Vanneste, D., & Ahebwa, W. M. (2015). Analysing governance in tourism value chains to reshape the tourist bubble in developing countries: The case of cultural tourism in Uganda. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1027211

- Ajuntament de Barcelona (2016). Reglament de funcionament intern del Consell Turisme i Ciutat. Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona (2017). Pla especial urbanístic per a la regulación dels establiments d’allotjament turístic, albergs de Joventut, residències col·lectives d’allotjament temporal i habitatges d’ús turístic a la ciutat de Barcelona. Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Álvarez Soler, L. (2019). City for sale. Bausan Films.

- Arias-Sans, A., & Russo, A. P. (2017). The right to Gaudí. What can we learn from the communing of Park Güell, Barcelona?. In Colomb C., & Novy J. (Eds.). Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City (pp. 247–263). Routledge.

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Barcelona Turisme (2020). “Qui som”. Retrieved April 18, 2020 from https://professional.barcelonaturisme.com/ca/corporate/informacio-corporativa/qui-som

- Beaumont, N., & Dredge, D. (2010). Local tourism governance: A comparison of three network approaches. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903215139

- Blakeley, G. (2010). Governing ourselves: Citizen participation and governance in Barcelona and Manchester. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00953.x

- Blanchet, T. (2015). Struggle over energy transition in Berlin: How do grassroots initiatives affect local energy policy-making? Energy Policy, 78, 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.11.001

- Boer, R. W. J., & De Vries, J. (2009). The right to the city as a tool for urban social movements: The case of Barceloneta [Paper presentation]. Paper Presented at the 4th International Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism, Amsterdam/Delft,.

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.580586

- Cabrerizo, C., Sequera, J., & Bachiller, P. G. (2016). Entre la turistificación y los espacios de resistencia en el centro de Madrid: Algunas claves para (re) pensar la ciudad turística. Ecología Política, (52), 78–82.

- Castells, M. (1983). The city and the grassroots: A cross-cultural theory of urban social movements. University of California Press.

- Chibás Fernández, E. (2014). Bye Bye Barcelona. Barcelona, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kdXcFChRpmI.

- Cócola-Gant, A., & Pardo, D. (2017). Resisting tourism gentrification: The experience of grassroots movements in Barcelona. Urbanistica Tre, Giornale Online Di Urbanistica, 5(13), 39–47.

- Conceição, C. C., Dos Anjos, F. A., & Gadotti dos Anjos, S. J. (2019). Power relationship in the governance of regional tourism organizations in Brazil. Sustainability, 11(11), 3062–3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113062

- Cuadrado, N., & Monedero, M. (2016). El sueño de Barcelona: ¿una ciudad para vivir o para ver?. Editorial Open University of Catalonia.

- Damayanti, M., Scott, N., & Ruhanen, L. (2019). Coopetition for tourism destination policy and governance: The century of local power?. In Fayos-Solà, E. & Cooper C. (Eds.). The Future of Tourism (pp. 285–299). Springer.

- De Souza, M. L. (2006). Social movements as ‘critical urban planning’ agents. City, 10(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810600982347

- Fava, N., & Rubio, S. P. (2017). From Barcelona: The pearl of the Mediterranean to Bye Bye Barcelona. In Bellini, N., & Pasquinelli C. (Eds.). Tourism in the City (pp. 285–295). Springer.

- Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2011). Toward a general theory of strategic action fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01385.x

- Gravari-Barbas, M., & Jacquot, S. (2017). No conflict? Discourses and management of tourism-related tensions in Paris. In Colomb, C., & Novy J. (Eds.). Protest and resistance in the tourist city. (45–65). Routledge.

- Groth, J., & Corijn, E. (2005). Reclaiming urbanity: Indeterminate spaces, informal actors and urban agenda setting. Urban Studies, 42(3), 503–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500035436

- González-Morales, O., Álvarez-González, J. A., Sanfiel-Fumero, M. A., & Armas-Cruz, Y. (2016). Governance, corporate social responsibility and cooperation in sustainable tourist destinations: The case of the island of Fuerteventura. Island Studies Journal, 11(2), 561–584.

- Moncloa, L. (2020). El gobierno decreta el estado de alarma para hacer frente a la expansión de coronavirus COVID-19. https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/consejodeministros/resumenes/Paginas/2020/14032020_alarma.aspx

- Lofland, J. (2017). Protest: Studies of collective behaviour and social movements. Routledge.

- Mayer, M. (2007). Contesting the neoliberalization of urban governance. In Leitner H., Peck, J. & Sheppard, Erick S. (Eds.). Contesting neoliberalism: Urban frontiers (pp. 90–115). Guilford Press.

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1857–1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

- Minoia, P. (2017). Venice reshaped? Tourist gentrification and sense of place. In Bellini, N., & Pasquinelli, C. (Eds.). Tourism in the city (pp. 261–274). Springer.

- Moulton, S., & Sandfort, J. R. (2017). The strategic action field framework for policy implementation research. Policy Studies Journal, 45(1), 144–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12147

- Moscardo, G. (2011). Exploring social representations of tourism planning: Issues for governance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.558625

- Novy, J., & Colomb, C. (2017). Urban tourism and its discontents: An introduction. In Colomb, C. & Novy, J. (Eds.), Protest and resistance in the tourist city (pp. 1–30). Routledge.

- Özdemir, E., & Eraydin, A. (2017). Fragmentation in urban movements: The role of urban planning processes. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(5), 727–748. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12516

- Parés, M., Bonet-Martí, J., & Marti-Costa, M. (2012). Does participation really matter in urban regeneration policies? Exploring governance networks in Catalonia (Spain). Urban Affairs Review, 48(2), 238–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411423352

- Pinkster, F. M., & Boterman, W. R. (2017). When the spell is broken: Gentrification, urban tourism and privileged discontent in the Amsterdam canal district. Cultural Geographies, 24(3), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474017706176

- Presenza, A., Del Chiappa, G., & Sheehan, L. (2013). Residents’ engagement and local tourism governance in maturing beach destinations. Evidence from an Italian case study. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.01.001

- Qian, C., Sasaki, N., Shivakoti, G., & Zhang, Y. (2016). Effective governance in tourism development – Analysis of local perception in the Huangshan mountain area. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.08.003

- Quick, K. S., & Bryson, J. M. (2016). Public Participation. In C. Ansell & J. Torfing (Eds.). Handbook on theories of governance (pp. 158–169). Edward Elgar.

- Richter, R., Fink, M., Lang, R., & Maresh, D. (2020). Social entrepreneurship and innovation in rural Europe. Routledge.

- Sawatsuk, B., Darmawijaya, I., Ratchusanti, S., & Phaokrueng, A. (2018). Factors determining the sustainable success of community tourism: Evidence of good corporate governance of Mae Kam Pong homestay, Thailand. International Journal of Business and Economic Affairs, 3(1), 13–20.

- Scott, N., & Marzano, G. (2015). Governance of tourism in OECD countries. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1041746

- Sequera, J., & Nofre, J. (2019). Urban activism and touristification in Southern Europe. In J. Ibrahim & J. M. Roberts (Eds.), Contemporary left-wing activism, vol 2: Democracy, participation and dissent in a global context (pp. 88–105). Routledge.

- Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 374–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.01.011

- Silver, H., Scott, A., & Kazepov, Y. (2010). Participation in urban contention and deliberation. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(3), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00963.x

- Smith, A. (2005). Conceptualizing city image change: The ‘re-imaging’ of. Tourism Geographies, 7(4), 398–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680500291188

- Statista (2020). Number of tourists in hotels in Barcelona city from 1990 to 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2020 from https://www.statista.com/statistics/452060/number-of-tourists-in-barcelona-spain/

- Xing, S., Spierings, B., Dijst, M., & Tong, Z. (2020). Analysing trends in the spatio-temporal behaviour patterns of mainland Chinese tourists and residents in Hong Kong based on Weibo data. Current Issues in Tourism, Advance Online, 23(12), 1542–1558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1645096