Abstract

A debate is emerging about the evolving functions and roles of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). New functions pivot on value-adding to the social, environmental and economic sustainability of communities – or in tourism parlance – destinations. This paper extends knowledge with a case study of an Italian-based EU project, in which a local university took a prominent role in developing a city and its countryside into a sustainable gastronomy and food tourism destination, working with a variety of stakeholders. Synthesising the collaborative destination alliance and university ‘third mission’ co-creation for sustainability frameworks, the study extended across various collaborative activities, including two years beyond the life of the project. Results show the university performed numerous roles enacting the co-creation for the sustainability approach, and that these roles evolved through a communicative and outcomes-based cyclical process. Theoretically, this case study serves as a functional platform explaining the new ways in which tourism academic sector performance is reviewed and evaluated. Practically, this case informs sustainable academic and community collaborations in tourism destinations.

Introduction

Commentators suggest that sustainable tourism has “disproportionately focused on the environmental aspects of tourism as compared to the broader triple-bottom-line expectations of sustainable development” (Ruhanen et al., Citation2015, p.529), while the social pillar of sustainability is often neglected by policy makers and researchers (Boström, Citation2012; Robinson et al., Citation2019). In this context, universities are embracing emerging functions extending beyond traditional industry partnership approaches (Solnet et al., Citation2007). Scholars recognise this dynamic context by conceptualising new models of collaboration and, in recent decades, the commitment of universities in the civic society has become more important, above all in rural areas where Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have increasingly built relationships with local stakeholders and worked on co-creation activities to achieve sustainable development objectives (Trencher et al., Citation2013; Cavicchi et al., Citation2013). In fact, many HEIs are now involved in assessing the presence of specific needs by engaging themselves in place-based projects involving several actors to propose innovative solutions to real problems.

Among these contributions, a specific framework, the so-called ‘co-creation for sustainability’, directly addresses sustainability challenges from a participatory perspective (Trencher et al., Citation2013; Trencher et al., Citation2014a; Trencher et al., Citation2014b). The basic premise is that sustainability challenges are so broad, complex and ambitious, that their solutions need to be co-created by multiple actors. Universities are not exempt from what could be considered both a ‘social duty’ and an opportunity to contribute to overall systemic change framed within the knowledge economy broadly – including tourism (Cooper, Citation2006). Co-creation for sustainability implies a new model for universities, that of a transformative university. This model is conceived as “a multi-stakeholder platform engaged with society in a continual and mutual process of creation and transformation” (Trencher et al., Citation2014a, pp. 7-8). This approach supports community-based action as a tool to foster sustainable tourism development (McGehee et al., Citation2015).

Given these sustainability premises, this paper presents a case study on the long-term (ongoing) collaboration between a university and local stakeholders, born of a URBACT project funded by the European Commission (herein the European Project). The main aim of the project and its subsequent evolution was contributing to branding a city in eastern Italy’s Marche region as a city of gastronomy, with the long-term objective of fostering sustainable tourism development based on food and gastronomy. An emerging literature is directly treating the link between gastronomy and sustainable development, as detailed in the literature review.

Yet while different studies addressed third mission activities or university roles within these activities (e.g. Molas-Gallart et al., Citation2002, Trencher et al., Citation2013), there is a knowledge gap in terms of unpacking the process that creates and sustains university engagements with local communities to enable co-creation. Accordingly, the overarching objective of this paper is to empirically reveal the process through which co-creation among university and community stakeholders is established and maintained, emphasising engagement facilitators and barriers within the context of destination branding. To address this objective, data were collected, critically reviewed, and conceptualised around a co-creation for sustainability framework, during different stages of the collaboration between university and local stakeholders.

Literature review

One of the objectives of the social pillar of sustainability is to support transformations aimed at ensuring public awareness, equity, participation and social cohesion (Murphy, Citation2012), as advocating for social justice and inclusiveness urges participation from diverse stakeholders for sustainable tourism development. However, the focus is still often on tourism businesses rather than on communities, who should be engaged directly to support social sustainable change (Cockburn-Wootten et al., Citation2018).

Multi-stakeholder inclusion appears essential to enable governance for sustainable development. Sustainability challenges are not bounded by disciplines, but rather require the pooling of different types of knowledge possessed by different actors. Therefore, multi-stakeholder networks, including local communities, emerge as pivotal tools in addressing sustainability challenges (Miller et al., Citation2014). Collaboration among different actors is fundamental to create social transformations enabling the materialisation of sustainable development. In fact, every place is different and a one-size-fits-all model does not exist. Accordingly, each sustainable tourism development strategy needs to consider place-specific characteristics and include its stakeholders - who should contribute to processes that affect them (Rinaldi, Citation2017; Ramaswamy & Ozcan, Citation2014).

However, multi-stakeholder inclusion can in fact be considered as a necessary but not sufficient condition for sustainable tourism development. It appears that often to make multi-stakeholder networks function effectively, it might be decisive to build capacities (Kempton, Citation2015) as well as engaging actors who can enable cooperation. Therefore, this study identifies universities as place-based super partes institutions (Cavicchi et al., Citation2013), that might support long-term community engagement within tourism development.

The European Commission has defined sustainability in European projects by focusing on their long-term impacts. A project is considered sustainable if it continues delivering benefits to beneficiaries and/or other constituencies after the Commission’s financial assistance is terminated (European Commission & Directorate-General Education & Culture, 2006). This broad definition entails two main dimensions (European Commission & Directorate-General Education & Culture, Citation2006, URBACT, Citation2013):

Results and exploitation: activities/outputs are maintained or developed after the end of the funding; outputs developed for the project/initiative are used by other people/groups not involved in the project.

Networks: the international and the local networks engaged for the project/initiative are maintained and/or extended after the funding ends.

These aspects relate also to the social/human dimension of sustainability, in that it is necessary not only to offer tools, but also to enable communities and individuals to maintain and protect local resources, material (e.g. environment, landscape), immaterial (e.g. culture, traditions, know-how), and building on already developed outputs and networks.

Food, destination branding, and tourism development

Food has been identified as a principal vehicle by which tourism destinations develop and broadly contribute to community; socially, culturally and economically. Food tourism, as fundamentally represented in the literature, concerns supply-side development and planning (Getz et al., Citation2014). Indeed, as it has been observed (Ellis et al., Citation2018), the earliest food tourism literature was primarily focused on the economic benefits to the host community (Belisle, Citation1983). A supply-side approach considers the various destination products, experiences and attributes that contribute to a destination’s gastronomic and culinary resources (e.g. agrarian/fisheries/wine) offer. When considered in this way an almost infinite number of destination stakeholders are in one way or another integral to the destination’s food value proposition inter alia restaurateurs and chefs, grocers, delicatessens, producers and suppliers, and event and tourism planners. As such a destination’s gastronomic endowments are a core tourism asset for events and festivals (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2010), cultural identity and expressing authenticity (Robinson & Clifford, Citation2012) - and for destination branding and marketing (Okumus et al., Citation2007). Food and gastronomy are increasingly recognised as pivotal elements to support place branding and marketing, because they link together many components of the destination experience (Rinaldi, Citation2017). Food culture seems to be able to connect different branding elements, such as products, practices, food preparation and consumption customs, provenance, sensory elements, preparation of meals and foodscapes (Richards, Citation2015).

Many studies address the potential that food and gastronomy might have to support sustainable tourism development (e.g. Sims, Citation2009; Sidali et al., Citation2015; O’Sullivan & Jackson, Citation2002). Yet from a governance perspective, it is necessary to involve local stakeholders for community-based participatory approaches (Kavaratzis & Hatch, Citation2013), which appear important to support more sustainable place development. Participatory branding approaches (Kavaratzis, Citation2012) consider destination branding as a co-creation process, whereby stakeholders are considered as co-creators engaged in a dialogue to co-construct the place brand. In a similar fashion, Waligo et al. (Citation2013, p.342) emphasise that effective stakeholder participation is essential to sustainable tourism, as destinations are “a network of interdependent multiple stakeholders”.

This bottom-up approach supports the mobilisation of local resources for the development process more effectively than top-down marketing approaches, even though bottom-up and top-down approaches are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they should be used together, so that bottom-up community-led approaches can complement top-down approaches from national/regional authorities (Zago et al., Citation2014). Local tourism branding represents a top-down strategy that potentially could “draw together a network of grassroots activities” (Woodland & Acott, Citation2007, p.719). This process is particularly relevant in rural areas, where the majority of tourism businesses are constituted of micro/small-sized enterprises with limited resources and low levels of knowledge. Therefore, information exchange, resource sharing and collaboration between operators are essential features for small-scale community-based rural tourism development (Ying et al., Citation2015). As Idziak et al. (Citation2015) state, not only does local participation build capacity and raise efficiency and effectiveness of implemented sustainable development projects, but local participation has also been recognised as facilitating the redistribution of power and empowering local communities, enhancing social capital and strengthening local identity.

However, even though stakeholder-inclusive governance appears to be one of the pillars for sustainable tourism development, there are a paucity of studies addressing the process that creates and sustains university engagement with local communities as co-creators of destination branding around food and gastronomy. This article aims to address this gap, by unpacking the process through which co-creation among university and community stakeholders is established and maintained over time. In particular, this article emphasises engagement facilitators and barriers, as well as determining the role(s) universities might have within this process.

Moving beyond the third mission: new 21st century roles and functions for HEIs

According to Sneddon et al. (Citation2006) a crucial aspect proffered by the Brundtland report (WCED, 1987) was the need for far-reaching campaigns of education, debate and public participation to actualise changes in attitudes, aspirations and social values. These aspects contribute to empowering stakeholders and communities and represent a highly relevant dimension of sustainability. Indeed, learning approaches “such as mentoring, facilitation, participative inquiry, action learning and action research” are ways of exploring the sustainability agenda (Tilbury, 2007, p.118). This suggests that a reconsideration of university and HEIs roles in this process should also take place. Thus, new functions are currently explored by many scholars belonging to both HEIs and international institutions and organisations such as the European Commission and the OECD.

A turning point in the evolution of the studies concerning universities’ roles in society was represented by the emergence of the third mission (Etzkowitz, Citation1998). It is widely acknowledged that a university’s first mission is teaching and their second mission is research. The third mission, was defined as the bundle of activities that generate, use, apply and exploit knowledge and other university capabilities - outside academic environments (Molas-Gallart et al., Citation2002). As Trencher et al. (Citation2014a, Citation2014b) note though, the idea of societal contribution of third mission activities can be mainly assimilated to 'technology transfer', 'the entrepreneurial university', 'triple-helix partnerships' (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, Citation2000). These functions are essentially aimed at contributing to economic development. Therefore, while the third mission in principle refers to all activities that are not covered by the first and second missions, this social contribution is often promoted as an economic contribution.

This view appears to be too narrow while dealing with complex and transversal issues such as that of sustainability, “whose challenges encompass social, economic, political, cultural and environmental considerations” (Rinaldi et al., Citation2018, p.69). At the same time, sustainability needs to be dealt within context, as challenges and solutions depend on place-specific characteristics and are in a continuous process of creation and transformation (Trencher et al., Citation2014b). Actually, this need for sustainable learning approaches allowing multiple stakeholders such as universities, local government, economic players, communities and civil society, to co-create solutions able to address sustainability challenges, has contributed to the emergence of a proposed new function for universities; that of co-creation for sustainability (Trencher et al., Citation2013; Citation2014a; Citation2014b). There is still academic debate over whether co-creation for sustainability represents an extended version of third mission reaching beyond its economic/technological dimension, or if it should be considered as a fourth mission whose aim is to materialise sustainable development (Rinaldi et al., Citation2018). However, in this new function - gaining traction in academic literature (e.g. Dentoni & Bitzer, Citation2015; Baker-Shelley et al., Citation2017) - the model passes from entrepreneurial to transformative university, conceived as “a multi-stakeholder platform engaged with society in a continual and mutual process of creation and transformation” (Trencher et al., Citation2014a, pp.157-158). Addressing sustainability challenges requires universities to shift away from their ‘ivory tower’, by giving greater emphasis to knowledge production as a means for creating potential solutions aimed at triggering societal transformations (Trencher et al., Citation2017). This of course does not imply that the first and second missions are not relevant anymore, rather, a knowledge society necessitates that university roles are wider and extend beyond purely academic contributions - reaching societal issues. Critically, co-creation is not only collaboration: co-creation does not mean only ‘to work together’, but implies opening up to new ideas, embracing these ideas, and implementing them to create a new vision of the world (e.g. apply them also in daily life, or current work cf. Ramaswamy & Ozcan, Citation2014).

Co-creation for sustainability represents a broad construct that synergies different research and social engagement dimensions at varying degrees and combinations, such as (non-exhaustively): participatory and action research; technology transfer; transdisciplinarity; cooperative extension system; service learning; regional development; urban reform; living laboratories (Trencher et al., Citation2014a). This study considers in particular participatory and action research, and transdisciplinarity dimensions as essential for the enactment of co-creation for sustainability function in the case study presented. Describing in detail each of the dimensions goes beyond the scope of the paper, however, while co-creation for sustainability is a rather new concept within tourism research, literature does offer some examples of how universities can be engaged in different activities to support sustainable tourism. Cockburn-Wootten et al. (Citation2018, p.4) opine that in order to promote social sustainable change within communities, it is necessary to develop long-term engaged collaboration and participation in which academics can provide “environments that facilitate spaces of welcome, empowerment, longer engagement and inclusion”. They emphasise that academics have a pivotal role in supporting communication processes that translate knowledge to make it accessible to communities and enable social change. Therefore, academic roles as translator and communicator of research and knowledge, as well as facilitation and participation with communities, appear crucial to support social change. Similarly, Higuchi and Yamanaka (Citation2017) found that collaboration between universities and local actors is supported by academics’ capacity to provide translatable knowledge relevant to tourism practitioners. However, co-creation between universities and tourism enterprises should be supported by embedded relationships, facilitating the building of trust among actors, transfer of information, and problem-solving capacities.

And yet, as pointed out by McCool et al. (Citation2013), the impact of academic knowledge on the real (non-academic) world appears very limited for two main reasons. One is the academic award system that privileges academic prestige over social impact; while the other resides in the need for academics to have long-term engagements with “real world” actors. While this paper does not address the first issue – as it does not focus on university’s evaluation system – it can shed light on the second aspect, as the data collected for the case study specifically aims at unpacking the process of how long-term collaboration among university and local stakeholders is established and maintained.

University roles in the co-creation for sustainability paradigm

Given the complexity of sustainability, it is pertinent to report different roles universities can assume in co-creating a sustainability framework. Trencher et al. (Citation2013) proposed a classification of roles that universities can assume in the co-creation for the sustainability process: scientific advisor/communicator, inventor/innovator, revitaliser/retrofitter, builder/developer, director/linker and facilitator/empowerer role. These roles, as well as the co-creation for sustainability construct, will be used to investigate the involvement of the university engaged in the URBACT Gastronomic Cities case study, both during and after the project, to also explore the temporal dimension of sustainability.

Research context

University- stakeholder collaboration in time

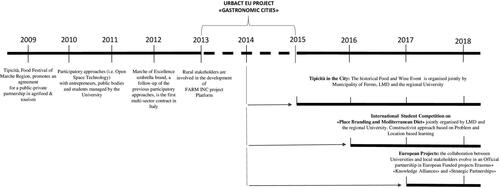

The Italian university, subject to this case study, started consistently working with local business and communities since 2009 around topics like territorial marketing, marketing of agri-food products, place branding and rural development. shows how the relations between the case study university and local stakeholders developed in time through different actions, activities and networks. In particular, from 2009 to 2013 the university started working with local stakeholders mainly by facilitating multi-stakeholder Forums (Marche d’Eccellenza), and through a European project. A stepping stone to university-stakeholder collaboration was represented by Gastronomic Cities project, which contributed to form a long-term alliance between the university and a multi-stakeholder network of local stakeholders - representing a Laboratory for Mediterranean Diet (LMD). The main aim of Gastronomic Cities was to ensure the transfer of good practice from a (giving) city in Spain to four other (receiving) cities in Europe. Good practices consisted of the giving city’s capacity to leverage on food and gastronomy for destination branding. To ensure the transfer of good practice, the project involved transnational staff exchange among different stakeholder groups (chefs, producers, organisers, etc.) to allow stakeholders to understand how good practice was implemented in the giving city; and through a participatory process at local levels facilitated by the university, aimed at co-creating a Local Action Plan (LAP), containing a list of actions and activities to be implemented. Due to space constraints, details on the university-stakeholder collaboration over-time are elaborated in Appendix 1. visualises all activities held before and after Gastronomic Cities, to highlight joint activities. Activities held from Gastronomic Cities (2014) onwards are unpacked in the data.

Materials and methods

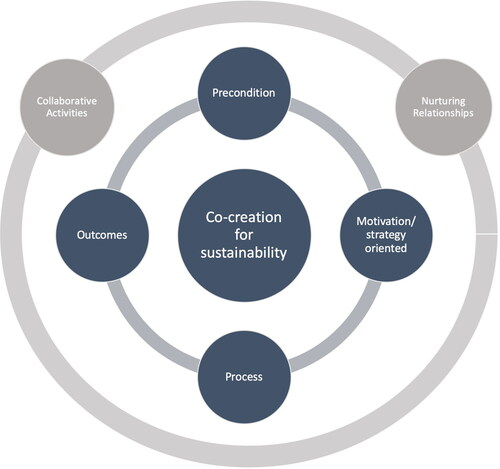

Given the nature of the research aims, a case study approach was adopted. Case studies have a long tradition in tourism research given the phenomenon of destinations as units of analysis, and their complex networks requiring exploration. They have proved valuable in previous examinations of attaining sustainable goals where multiple stakeholders are involved in a tourism destination (Idziak et al., Citation2015). The case study was structured around the Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) collaborative process framework. Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) framework guided the analysis of the case study, ultimately serving as a methodological tool. While the framework was conceptualised in the context of marketing, it is fundamentally a collaborative explicator, and it provided somewhat unexpected utility in a holistic analysis of the case study. Indeed, reports the four conceptual ‘constructs’ of Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) framework, mapped to the empirical data. Following, we embark on a detailed description of the two critical stages of the project’s implementation, which correspond to the ‘process’ construct of the framework.

Table 1. Adapting the destination marketing alliance framework.

Empirical data collection – focus on the process

To address the objective of the paper - to empirically reveal the process through which co-creation among university and community stakeholders is established and maintained within the context of destination branding – the authors built on both the co-creation for sustainability and tourism literature. Given that co-creation for sustainability is an increasingly established approach in social science research - however new within tourism literature - we adopted Wang and Xiang’s framework that is an established model within tourism research to develop interview questions and guide the analysis of data. Accordingly, we aim to contribute to tourism literature by determining how co-creation for tourism sustainability might be realized. summarises the two research stages, presenting the focus and the methods of each stage.

Findings and discussion

The multiple sources of data collection summarised () outlined different ways in which universities can contribute to sustainability co-creation of destination branding initiatives within multi-stakeholder networks.

Stage 1. – gastronomic cities project

Part a) URBACT Local Support Group (ULSG) facilitation meetings

In this stage, the university had a specific role assigned by the URBACT method: that of facilitating ULSG meetings at the local level, carrying out a multi-stakeholder consultation process, assisting some of the exchanges at the transnational level, and supporting stakeholders and Municipality in delivering the LAP. Through university-facilitated Focus Groups (FGs) and regular meetings, stakeholders were able to understand local strengths and weaknesses, and to identify different potential activities to be included in the LAP, representing a roadmap of actions leading towards the implementation of giving city best practices. ULSG meetings would also allow stakeholders who were in transnational exchanges to report their experiences abroad, concerning practical activities/solutions that other groups in other countries had devised and to reflect with local stakeholders which actions might be implemented in local contexts.

Then, through the survey created by university facilitators, and informed by the literature, stakeholders had to select which of the activities they had identified in the meetings were more interesting/feasible from their perspective; the ones with higher scores were included in the LAP. There was strong agreement from the survey’s participants on a range of initiatives to activate food and wine-lead place-branding activities, including various farm-based activities such as cooking classes at agri-tourism businesses, city-based events like ‘gastro-nites’, and some collaborative marketing and knowledge-sharing. This step of the case study was functional both in defining activities for insertion in the LAP through a facilitated bottom-up approach and to understand stakeholders’ perceptions of pros and cons related to the opportunity of leveraging food and gastronomy for destination branding of the city. On the basis of these results, the LAP was co-created by the municipality and stakeholders, as facilitated by the university.

Part b) – students’ work

The university team working into the project facilitated students’ involvement through the PBL approach. The students were divided into five groups: violet, red, blue, yellow and green. Appendix 2 indicatively reports two student groups’ work, framed according to the following dimensions: name of the group; problem identified; target group addressed; objective(s); activities. Students offered fresh perspectives on how to tackle some of the weaknesses/threats emerging from stakeholders’ discussion in the previous phase (ULSG meetings). The students’ involvement was beneficial both to students and stakeholders. The former, through PBL, learnt how to draw from academic theories to frame a problem, how to relate/engage with stakeholders to understand their perspectives on problems, and finally how to critically and reflexively address real-world issues, by providing recommendations to the city stakeholders. In the last stakeholder meeting, each student group delivered structured presentations, supported by audio/visual material on their topic, offering suggestions and ideas, which informed the LAP. Therefore, both students and stakeholders had the chance to be engaged in the co-creation process of a policy document (LAP), enacting the collaborative (social) dimensions of construction of knowledge (Donnelly, Citation2010).

Stage 2 – Post gastronomic cities project - Interviews with “project champions”

This stage represents the evaluation and transformation parts of the process construct, carried out through semi-structured interviews with ‘project champions’. Interviews were made in two different moments, both to understand if and how stakeholders’ perceptions on the university roles would have changed, and to verify the temporal dimensions of sustainability. The first round was aimed at investigating the impact of the Gastronomic Cities project on the stakeholders involved and how it contributed to establishing relationships between the local stakeholders and the university. The second interview round, performed two years after the end of the project, was aimed at understanding the evolution of post-project activities and the evaluation that stakeholders had of the work and engagement carried out by the university. After the end of the project, LMD stakeholders kept engaged and active, and performed several initiatives. For example, three International Student Competitions on Place Branding and Mediterranean Diet were co-organised by LMD and the university, involving around 50 students per edition, from eight universities across Europe. These activities support the EC (2006) conception of project sustainability; therefore, interviews were conducted to investigate how relationship between stakeholders and the university had evolved over time. Prominent activities carried out after the end of the project are collated in (Outcomes section).

First round interviews, performed after project ended

Stakeholders would recognise the university’s involvement in different stages of the project as beneficial. During ULSG meetings, the university facilitation would contribute to building a ‘shared horizon’ between different stakeholders.

“Each person’s opinion would be taken into account. In every new meeting we would make a little step forward, as information gathered in the previous meeting were re-elaborated and proposed back to us with new questions. So, it seemed like we were actually going somewhere”. (P2)

“It was really interesting to see how in the first ULSG meeting we were only a few people, while you could totally see an increasing in people’s presence meeting after meeting. This is because people felt they had a voice, their ideas were taken into account and discussed together”. (P8)

These quotes speak to both the assembling and ordering elements of the framework, where issue identification, establishment of goals and development of programs can be seen as a circular process.

Concerning the issue of whether the university contributed towards pursuing project goals, one stakeholder emphasised,

“the most important part of this project has been the ‘awareness empowerment’ process, allowing stakeholders to become conscious of many issues” (P1)

and how this, together with several staff exchange trips eventually,

“made stakeholders feel protagonists in the project, rather than feeling subjected to it”. (P1)

One interviewee (P4) argued that the university’s support to the project had gone well beyond that expected:

“For the aims of the project we produced the LAP, but during and after this process the university supported us. Students came and interviewed us to come up with some potential innovative ideas starting from our strengths and weaknesses (PBL), we had internationally renowned scholars supporting us and giving us feedback, we had the chance to discuss about this project during ExpoFootnote1 and so on. So, I guess university involvement helped multiplying project impact somehow. Then I find it great that cooperation between us and the university continued after the project ended”.

These excerpts appear to link all central dimensions of the Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) framework. In particular, the structure of the ULSG itself was performed in a way that stakeholders were recursively asked to evaluate their choices, for example in terms of activities selected. Providing information about their own choices often prompted stakeholders to re-think what they deemed as relevant issues, which in turn would support identification of another goal and so on.

The interview statements seem to highlight different university roles (Trencher et al., Citation2013): the director/linker role, as the university contributed to creating a grand vision for the future and seeking its materialisation by leveraging other partners' assets and know-how. The facilitator role was expressly identified by the URBACT method, while stakeholders’ interviews have emphasised the empowerer role, as they could self-diagnose their problems and create conditions supporting a self-realised transformation as the destination product portfolio developed, in accordance with Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) outcomes process. Finally, the scientific advisor/communicator role, as university actors contributed influencing local governance structures and development trajectories, by co-creating LAP and advising potential courses of action once the project ended.

Second round of interviews

This step addressed the temporal dimensions in terms of the EC (2006) project sustainability goals, and to verify if and how stakeholders’ perceptions of their collaboration with the university had changed. These elements relate to the evaluation stage of the Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) framework, as stakeholders appeared to be retroactively assessing if goals were achieved and checking against previous expectations in terms of effectiveness of the cooperation.

Stakeholders-university: evaluating the long-term collaboration. All interviewees concurred that trust was an essential element, “the condicio sine qua non” (P2) for collaboration to exist, both among the LMD members and between the LMD and the university. Firstly, interviewees were asked if their approach and responsibilities had changed from the beginning of the collaboration between them and the university. It seems interesting to notice that while some of them would recognise the university as essential for the development of both LMD’s networks and activities, others would rather emphasise benefits that the university could gain through the collaboration with the group.

Concerning the first approach, P2 observed: “At the beginning, other stakeholders (not belonging to the Lab) were a bit sceptical about what we were doing. People from this region are a bit distrustful. When relationship with the university has started this changed a lot: producers and people now look for us. This is what has changed: before we were the ones that were looking for people, now they look for us. They saw we are serious. This I think for sure began when the relationship with university has started. It gave us more credibility and made us more visible”.

The second approach would emphasise how reciprocal knowledge has allowed the university to discover what the LMD was doing as well as how this was beneficial for academics to engage with real-world problems.

“Relationships have evolved. [The] university has now a better awareness of who we are and we better understand each other”. (P1)

“[The] university through this collaboration is trying to get out from being purely academic and engage with the territory. Here university is a bit late: it needs to get out from its ivory tower to be engaged with the territory and be a promoter of the territory through these initiatives” (P5).

Finally, a mediating opinion between the two approaches is evident:

“I have always considered a principle: that of science-practitioner, the practical scientist. This means that what you do has to be connected to a theory, to something that gives it a meaning. In a more specific sense to become a practical scientist there are two main essential lines: one is the direct action inspired by certain principles, the other is the scientific and cultural support that can come from an element which is the university”. (P4)

These excerpts emphasise how stakeholders saw the collaboration as beneficial for them in terms of acquiring more credibility within their local networks, but also how this was positive for the university because it allowed researchers to deal with reality-driven problems and take a role in the co-construction of sustainable development. The last quote (P4) interestingly sees the cooperation as two-way: both university and stakeholders need each other for the cooperation to be fruitful, by linking principles to actions.

Transformation stage. Finally, the interviews were focused on the transformation stage, to investigate if stakeholders perceived to have achieved something through this collaboration, and understand future directions. It is noteworthy that all stakeholders interpreted the collaboration as beneficial, but each of them for different reasons.

Some saw the collaboration as beneficial for the university:

“If we wouldn’t have such collaboration, university would not have discovered a beautiful land like this one. We have been the bridges between university and this land”. (P1)

“University has helped us a lot at planning level and has indicated us some paths to follow that brought us to grow and keep going. Of course, there is also a reverse: even university has learned from us that there is a very fertile territory, a close-knit group that operates quite seriously. So we have a huge trust and respect for each other and we still have a long way to go”. (P3)

The ideas and activities emerging thanks to this lasting cooperation are also underlined:

“I feel like university galvanizes us, makes us being more cohesive and more channelled. I am talking of course about the people I am working with, as AndreFootnote2. For e.g. if there wasn’t the active involvement of the university and Andre we wouldn’t have done these student competitions, we wouldn’t have thought about it and we wouldn’t have been able to do them alone. Now one of our aspirations is that of being more autonomous”. (P5)

These elements align with Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) transformation stage, regarding evolutions into stronger partnerships. This aspect is also consistent with the EC (2006) conception of project sustainability with respect to an enlargement of local and international networks, and increased cooperation activities (e.g. the international student competitions).

It also emerged how this long-lasting collaboration was possible thanks to specific individual academics involved in working together with the LMD. This suggests that real trust and willingness to work together grows among people rather than among institutions. Many stakeholders put forward that their perception of academics used to be that of the ‘ivory tower’, and how in other situations they tried to approach academia but without success.

“I had approached some professors that would be interested into Mediterranean Diet as research area, but we were unable to engage them. We organised a congress and I still clearly remember this professor that attended and seemed interested, then I never heard from him again”. (P5)

“I consider the experience with the university, in particular with one of the university staff members and his team as the example of what I have always hoped for and that other universities did not realise at least from my own experience. Collaboration has reinforced with time”. (P4)

It appears that stakeholders have mixed opinions in terms of future directions of collaboration. While some emphasised that the collaboration was reinforced across time, and should continue, others underlined their need for autonomy. Evidently, the university might be more relevant in terms of enlarging the international network and engaging in international activities, while the LMD group seems to increasingly take the lead in terms of enlarging local networks and increasing local level activities.

The different activities held after the end of the project ( - Outcomes section) reveal the project as self-sustaining. For instance, the International Student Competitions on Place Branding and Mediterranean Diet represented the first international events, born of close cooperation between the LMD and the university. The university activated its international networks (Rinaldi et al., Citation2018) to identify relevant international keynote speakers and foreign universities interested in participating into this experiential learning event, while the LMD coordinated all field visits and practical administration of the event. The competitions’ focus on social media and ICT potential for territorial promotion is also related to the inventor/innovator role: the diffusion of technologies and their potential to innovate the territorial offer, supported the LMD’s social entrepreneurialism (Trencher et al., Citation2013).

Academic staff perspectives

Eight focused structured interviews were held with academic staff involved in the collaboration process with local stakeholders: four interviews were carried out with international academics, and four with the university’s internal staff. The interviews focused on the identification of facilitators and barriers of the university’s involvement with stakeholders. Academic interviewees are coded as A (from one to eight).

Facilitators

Academic staff identified stakeholder commitment and involvement as a key factor supporting collaboration (A1, A2, A4, A6, A7, A8). Trust was mentioned as the glue able to develop links between university and stakeholders, even though “a gradual and progressive developing of ties is sometimes considered ‘slow’, but faster dynamics would simply not work” (A3). The presence of students willing to spend their future in the region was also considered as an important facilitator to university-business collaboration (A3, A4), as well as involvement of PhD students and early career researchers as mediators between different stakeholder groups (A8). The use of experiential learning and participatory approaches in different activities appear to contribute to “reducing the communication gap between scholars and students” (A5).

Barriers

One barrier was Italian political instability and sudden alternations of local governments (A3, A4), which negatively affects long-term collaboration efforts (A6). University administration and bureaucracy (A2, A4, A8), “narrowmindedness of local stakeholders, and their often defensive attitude” (A3) when discussing and evaluating local policies with university representatives (A5), as well as language barriers (A1) when local stakeholders were involved in international activities, were indicated as further barriers to collaboration. Many scholars appear not capable to orient their own research and teaching activities toward territorial needs (A5), and multi-stakeholder group management appears a cumbersome task (A7). Moreover, one of the main barriers appears to be the lack of clear institutionalisation from both university and stakeholders of this co-creational process (A8): co-creation exists in activities but there is a lack of a concrete dialogue and long-term vision of the collaboration (A7).

These excerpts highlight elements widely discussed in academic literature. The need to build trust among stakeholders belonging to diverse spheres is acknowledged as an essential condition for relation-based cooperation, promoting “trust, relational norms of flexibility, solidarity, bilateralism and continuance” (Lee & Cavusgil, Citation2006, p.900). However, it takes time to build trust among unfamiliar stakeholders and this requires long-term engagement from committed people (Rinaldi & Cavicchi, Citation2016). On the other hand, many scholars do not orient research and teaching towards territorial needs. Studies show that university evaluation systems tend to value only technical outcomes and quantitative measures such as numbers of patents, spin-offs (Rinaldi et al., Citation2018) making it even less rewarding for academics to engage in long-term relational engagements with communities.

University-community engagement: case study implications

Practically, it is hard to formalise all potential engagements universities might have with local communities, as their needs are contextual (Cockburn-Wootten et al., Citation2018). Academic engagement with community appears pivotal in terms of translating knowledge to make it accessible and support social change. From a project sustainability perspective (EC, 2006), the events carried out under stage 2 have contributed both to keeping the local network engaged and enlarging the international networks. As suggested by Cornelissen et al. (Citation2001, p.173) and congruent with research results, “sustainability consistently means, either explicitly or implicitly, ‘continuity through time’”, where continuity is considered as context-dependent to environmental, societal and economic issues. Accordingly, it appears that a long-term co-creation for sustainability process is created by a more tangible aspect constituted by co-creational activities, and a “softer” side focused on nurturing relationships.

Data show that universities are increasingly crucial institutions under a co-creation for sustainability framework, and could not be substituted by non-academic institutions. In particular, this case highlights different characteristics that determine universities’ uniqueness. First, universities are super partes and non-profit institutions (Cavicchi et al., Citation2013) that are not following a specific political or business agenda. In the case study, this has ensured a high number of stakeholders attended meetings held during Stage 1 and openly discussed their issues and problems. While expertise in the field does belong also to non-academic institutions, university students played a central role in the case presented: during the project timeframe they provided solutions to stakeholders, while after the project ended they ensured the long-term sustainability of the project, for example by participating in student competitions. Another pivotal role was played by international renown scholars. They supported students’ work in terms of identifying challenges and defining questions for the interviews under the PBL method. They offered different perspectives to local stakeholders and they contributed to enlarging international networks by involving their (international) students to different editions of the student competitions. On the other hand, the lack of clear institutionalisation of these co-creational processes both from the university and stakeholders, makes it hard to go beyond joint activities and move towards a long-term vision of the collaboration.

In terms of theoretical contributions, this study has merged two frameworks: the co-creation for sustainability concept (Trencher et al., Citation2013) and the destination marketing alliance framework (Wang & Xiang, Citation2007). The former recognises the pivotal role of universities to support transitions towards more sustainable systems, but it has not yet been applied within the context of tourism, while the latter – which is already an established model in tourism research - served as a methodological tool to unpack these data and guide the analysis. offers a visual representation of how the two frameworks merged in this case study. In the centre, there is the co-creation for sustainability framework, and surrounding it the destination marketing alliance framework constructs. In the outer circle are indicated the two tangible (co-creational activities) and intangible (nurturing relationships) elements stemming directly from this case study. They represent transversal dimensions that allow co-creation for sustainability function to be enacted and sustained in the long-term. A significant contribution of this case study is the identification of the temporal dimension, which was not expressly captured in the original destination marketing alliance framework (Wang & Xiang, Citation2007). By emphasising how long-term cooperation between local stakeholders and the university provided the basis for a marketing alliance formation process (Wang & Xiang, Citation2007), and how this element might be related to EC (2006) understandings of project sustainability, the study has demonstrated how the stakeholder-university collaboration across time set the basis for a recursive process. Accordingly, the Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) framework might be reconceptualised in terms of a loop, rather than as distinct and sequential constructs (and elements). Consistently, co-creation appears to be a cyclical and dynamic process, and the university represents a mediating actor in the process. Therefore, this article extends Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) model of collaboration into a co-creational model. In this co-creational model, sustainability is seen as a circular process in which co-creation outcomes (the last construct of the model) appear to create new ideas/opportunities/relationships which constitute the new precondition (first construct of the model). This circular model appears to be fuelled and sustained by collaborative activities (tangible element) and nurturing relationships (intangible element).

Conclusions

This article unpacked the process that creates and sustains university engagements with local communities to enable co-creation within the context of destination branding. This was achieved by presenting a case study on the long-term collaboration between a university and community stakeholders beginning with an EU project, in order to highlight the relationship between stakeholders and academics, both during a project and after the end of the project, emphasising the evolution of the collaboration and discussing implications.

A number of contributions, extending previous knowledge, are proffered. Critically, the paper has synthesised a number of the specific sustainability co-creation third mission roles identified by Trencher et al. (Citation2013) and the constructs and processes for destination collaboration (Wang & Xiang, Citation2007). Specifically, this case study builds theoretically on the co-creation for sustainability concept (Trencher et al., Citation2013) and uses Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) framework as a methodological tool to unpack these data and guiding the codification of a co-creation process.

This case study has revealed different missions the university has undertaken throughout the process, and highlighted roles respectively assumed in different stages. In particular, although the focus of this paper was on demonstrating the universities third mission, of engagement and co-creation, the case study demonstrates that the first two missions of teaching and research were deeply embedded in the processes, via the active involvement of students (teaching) and various knowledge creation dimensions (research), both in terms of the project deliverables and subsequent academic outputs. Results show that university roles within a knowledge society framework appear to be expanding, and this multi-faceted engagement aimed at addressing real-world issues appear to support transition towards more sustainable systems. Therefore, this case shows universities roles and contributions to the social pillar of sustainability, by supporting communities realising sustainable tourism development. This case study addressed the co-creation for sustainability framework within the project implementation emphasising how the university facilitation supported reflexive thinking and allowed stakeholders to self-diagnose their problems and identify their potential solutions.

There are rich opportunities for future research, especially in an environment that is increasingly challenging the traditional role of the university and its value to society and the economy. As conversations shift to impact, rather than output and inputs, this case study regarding the emerging third mission of universities is timely and pertinent. Nonetheless, this case study does have its limitations. The obvious one is that the roles (Trencher et al., Citation2013) or processes (Wang & Xiang, Citation2007) cannot be readily transferable beyond the unique, idiosyncratic and contextual specifics of this case study, although opportunity exists to test them. However, while specific conditions are not transferable, the co-creation for sustainable destination branding model () can indeed be used and applied by multiple destinations embarking on similar destination branding efforts.

In particular, even though overall the relationship between local stakeholders and the university appeared to be mostly beneficial within the case study context, it also showed that while the university institution offers opportunities to carry out collaborations with stakeholders, long-term engagements which enable these collaborations to be implemented often depend on the willingness of a few academics, who consistently work on the ‘soft’ side of co-creation - building and maintaining relationships. In fact, the continuation of relationships and activities with stakeholders necessary to maintain trust and mutual understanding cannot be limited to the availability of research funds. Consequently, academic-stakeholder engagement is often dependent on academic staff willingness to continue cooperating with community. If on the one hand this might be due to personal characteristics of the actors involved, on the other it also reflects a structural problem: extant university evaluation systems appear to not reward academics for performing activities that fall outside first and second missions (Rinaldi et al., Citation2018), potentially hindering academics’ engagement. Moreover, long-term engaged relationships with communities are not a feature of research time allowances (Cockburn-Wootten et al., Citation2018), therefore even though academic engagement with society appears beneficial and the third mission is increasingly important, there is a paucity of established structures or benefits for those who do so. As McCool et al. (Citation2013) opine, even though there is a huge number of academic contributions to sustainable tourism in terms of reports, scientific articles and book chapters, the impact of academic knowledge on the real (non-academic) world appears very limited. Accordingly, it appears that there are two ways to resolve this issue: on the one hand, changing the academic award system to privilege social impact over academic prestige, and on the other the need for academics to have long-term engagements with “real world” actors in the tourism sector, such as industries, communities and institutions. The results from this case study are in line with McCool et al. (Citation2013), in that it indeed represents an example of long-term engagement with local community.

Including communities is pivotal to the path aimed at enhancing social sustainability and contributing to socially sustainable and inclusive tourism systems, but to enable this transformation, collective rather than individual efforts are required. Academics have an increased role in this collective process because by engaging with society they can offer accessible knowledge needed to support change, as well as representing super partes institutions that might have a role in enhancing stakeholder participation and engagement, as in the case presented. Therefore, academic institutions are increasingly expected to “serve as the role of conscience of society” (Bramwell et al., Citation2017, p.7) and should facilitate academics’ engagements with society to enable sustainable tourism development and support the social pillar of sustainability. Ultimately, the third mission appears pivotal for communities to access knowledge and making informed choices towards more sustainable tourism systems. Accordingly, universities are called upon to support these engagements with society in a more structured and formalised manner that allows academics to pursue meaningful long-term engagements, ultimately contributing to the social pillar of sustainability.

Acknowledgments

Chiara Rinaldi’s research was funded under the FOODEV project (Food and gastronomy as leverage for local development). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 707763. The content of this article does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the article lies entirely with the author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chiara Rinaldi

Dr. Chiara Rinaldi is a researcher at the Centre for Tourism, School of Business, Economics and Law – University of Gothenburg (Sweden). She joined the University of Gothenburg in 2016 as Post-Doctoral Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow for the research project “Food and gastronomy as leverage for local development – FOODEV”, financed by European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. Her research interests lie in the area of sustainability and sustainable development, food and gastronomy, participatory approaches, and tourism. She published several articles on these topics and presented her work in various international conferences. Chiara has also been involved in different EU co-funded projects, and for different roles: exchange researcher, project manager, and expert evaluator.

Alessio Cavicchi

Alessio Cavicchi is Professor at University of Macerata (Italy), where he teaches "Food Economics and Marketing" and "Place Branding and Rural Development" in the degree of International Tourism and Destination Management. He received his PhD in Economics of Food and Environmental Resources from University of Naples, Parthenope and a MSc in Food Economics and Marketing from University of Reading (UK). His main fields of interest and research are consumer food choice, economics of food quality and safety, and innovation and sustainability in agribusiness and tourism. He has served as an agrifood expert for several DGs of the European Commission, and he has coordinated different EU funded projects.

Richard N. S. Robinson

Associate Professor Richard N. S. Robinson teaches courses in hospitality and tourism management and professional development. His expertise and scholarship in teaching and learning are recognized by awards and advisory appointments at state and national level. His research, often nationally and internationally funded, explore tourism and hospitality workforce policy and planning, skills development, identifying ‘foodies’ consumer behaviours and designing and evaluating education programs. Richard currently holds an Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellowship.

Notes

1 The interviewee referred to Expo 2015 in Milan “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life”. http://www.expo2015.org/archive/en/index.html

2 A pseudonym.

References

- Baker-Shelley, A., van Zeijl-Rozema, A., & Martens, P. (2017). A conceptual synthesis of organisational transformation: How to diagnose, and navigate, pathways for sustainability at universities? Journal of Cleaner Production, 145, 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.026

- Belisle, F. J. (1983). Tourism and food production in the Caribbean. Annals of Tourism Research, 10(4), 497–513.

- Boström, M. (2012). A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: introduction to the special issue. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 3–14.

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., & Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1251689

- Cavicchi, A., Rinaldi, C., & Corsi, M. (2013). Higher education institutions as managers of wicked problems: Place branding and rural development in Marche region. Italy, International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 16(A), 51–68.

- Cockburn-Wootten, C., McIntosh, A. J., Smith, K., & Jefferies, S. (2018). Communicating across tourism silos for inclusive sustainable partnerships. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(9), 1–16.

- Cooper, C. (2006). Knowledge management and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.04.005

- Cornelissen, A. M. G., van den Berg, J., Koops, W. J., Grossman, M., & Udo, H. M. J. (2001). Assessment of the contribution of sustainability indicators to sustainable development: a novel approach using fuzzy set theory. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 86(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(00)00272-3

- Dentoni, D., & Bitzer, V. (2015). The role (s) of universities in dealing with global wicked problems through multi-stakeholder initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 106, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.050

- Donnelly, R. (2010). Harmonizing technology with interaction in blended problem-based learning. Computers & Education, 54(2), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.08.012

- Ellis, A., Park, E., Kim, S., & Yeoman, I. (2018). What is food tourism? Tourism Management, 68, 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.025

- Etzkowitz, H. (1998). The norms of entrepreneurial science: Cognitive effects of the new university–industry linkages. Research Policy, 27(8), 823–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00093-6

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The Dynamics of Innovation: from National Systems and “Mode 2” to a triple helix of university-industry-government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

- European Commission, Directorate-General Education and Culture. (2006). Sustainability of international cooperation projects in the field of higher education and vocational training - Handbook on Sustainability. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Retrieved from http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/tempus/doc/sustainhandbook.pdf

- Getz, D., Robinson, R. N. S., Andersson, T., & Vujicic, S. (2014). Foodies and food tourism. Goodfellow Publishers.

- Higuchi, Y., & Yamanaka, Y. (2017). Knowledge sharing between academic researchers and tourism practitioners: A Japanese study of the practical value of embeddedness, trust and co-creation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(10), 1456–1473. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1288733

- Idziak, W., Majewski, J., & Zmyślony, P. (2015). Community participation in sustainable rural tourism experience creation: a long-term appraisal and lessons from a thematic villages project in Poland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8-9), 1341–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1019513

- Kavaratzis, M. (2012). From “necessary evil” to necessity: stakeholders' involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331211209013

- Kavaratzis, M., & Hatch, M. J. (2013). The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Marketing Theory, 13(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593112467268

- Kempton, L. (2015). Delivering smart specialization in peripheral regions: the role of Universities”, Regional Studies. Regional Science, 2 (1), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1085329

- Kim, Y. G., Suh, B. W., & Eves, A. (2010). The relationships between food-related personality traits, satisfaction, and loyalty among visitors attending food events and festivals. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(2), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.10.015

- Lee, Y., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2006). Enhancing alliance performance: The effects of contractual-based versus relational-based governance. Journal of Business Research, 59(8), 896–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.03.003

- McCool, S., Butler, R., Buckley, R., Weaver, D., & Wheeller, B. (2013). Is concept of sustainability utopian: Ideally perfect but impracticable? Tourism Recreation Research, 38(2), 213–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2013.11081746

- McGehee, N. G., Knollenberg, W., & Komorowski, A. (2015). The central role of leadership in rural tourism development: a theoretical framework and case studies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8-9), 1277–1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1019514

- Miller, T. R., Wiek, A., Sarewitz, D., Robinson, J., Olsson, L., Kriebel, D., & Loorbach, D. (2014). The future of sustainability science: a solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustainability Science, 9(2), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0224-6

- Molas-Gallart, J., Salter, A., Patel, P., Scott, A., & Duran, X. (2002). Measuring Third Stream Activities: Final Report of the Russell Group of Universities. SPRU Science and Technology Policy Research Unity.

- Murphy, K. (2012). The social pillar of sustainable development: a literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2012.11908081

- Okumus, B., Okumus, F., & McKercher, B. (2007). Incorporating local and international cuisines in the marketing of tourism destinations: The cases of Hong Kong and Turkey. Tourism Management, 28(1), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.12.020

- O’'Sullivan, D., & Jackson, M. J. (2002). Festival tourism: a contributor to sustainable local economic development?. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(4), 325–342.

- Ramaswamy, V., & Ozcan, K. (2014). The co-creation paradigm. Stanford University Press.

- Richards, G. (2015). Food experience as integrated destination marketing strategy. In Proceedings of theWorld Food Tourism Summit, Estoril, Portugal, 8–11 April 2015.

- Rinaldi, C. (2017). Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development: A multidisciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability, 9(10), 1748, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101748

- Rinaldi, C., & Cavicchi, A. (2016). Cooperative behaviour and place branding: a longitudinal case study in Italy. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-02-2016-0012

- Rinaldi, C., Cavicchi, A., Spigarelli, F., Lacchè, L., & Rubens, A. (2018). Universities and smart specialisation strategy: From third mission to sustainable development co-creation. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-04-2016-0070

- Robinson, R. N. S., & Clifford, C. (2012). Authenticity and foodservice festival experiences. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 571–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.06.007

- Robinson, R. N., Martins, A., Solnet, D., & Baum, T. (2019). Sustaining precarity: critically examining tourism and employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1008–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1538230

- Ruhanen, L., Weiler, B., Moyle, B. D., & McLennan, C. L. J. (2015). Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(4), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.978790

- Sidali, K. L., Kastenholz, E., & Bianchi, R. (2015). Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8-9), 1179–1197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.836210

- Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802359293

- Sneddon, C., Howarth, R. B., & Norgaard, R. B. (2006). Sustainable development in a post Brundtland world. Ecological Economics, 57(2), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.04.013

- Solnet, D., Robinson, R. N. S., & Cooper, C. (2007). An industry partnerships approach to tourism education. The Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport and Tourism, 6(1), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.3794/johlste.61.140

- Trencher, G. P., Yarime, M., & Kharrazi, A. (2013). Co-creating sustainability: Cross-sector university collaborations for driving sustainable urban transformations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 50, 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.047

- Trencher, G., Yarime, M., McCormick, K. B., Doll, C. N., & Kraines, S. B. (2014a). Beyond the third mission: Exploring the emerging university function of co-creation for sustainability. Science and Public Policy, 41(2), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/sct044

- Trencher, G., Bai, X., Evans, J., McCormick, K., & Yarime, M. (2014b). University partnerships for co-designing and co-producing urban sustainability. Global Environmental Change, 28, 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.009

- Trencher, G., Nagao, M., Chen, C., Ichiki, K., Sadayoshi, T., Kinai, M., Kamitani, M., Nakamura, S., Yamauchi, A., & Yarime, M. (2017). Implementing sustainability co-creation between universities and society: A typology-based understanding. Sustainability, 9(4), 594–528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040594

- URBACT. (2013). The URBACT II Local Support Group Toolkit. Retrieved from www.urbact.eu

- Waligo, V. M., Clarke, J., & Hawkins, R. (2013). Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tourism Management, 36, 342–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.10.008

- Wang, Y., & Xiang, Z. (2007). Toward a theoretical framework of collaborative destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507302384

- Woodland, M., & Acott, T. G. (2007). Sustainability and local tourism branding in England's South Downs. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 715–734. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost652.0

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. University Press, Oxford.

- Ying, T., Jiang, J., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Networks, citizenship behaviours and destination effectiveness: a comparative study of two Chinese rural tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8–9), 1318–1340. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1031672

- Zago, R., Block, T., Dessein, J., Brunori, G. (2014). Participatory democracy in integrated rural development: the case of LEADER programme: towards Europe 2020 and community-led local development. In ILVP Winter school 'Place base approaches in regional development'. Proceedings. Retrieved from: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/6845538

Appendix 1

This Appendix contains the descriptive parts of the case study, by focusing on different steps of the university-stakeholder relations in time according to .

2009 – Tipicità – Food festival of Marche region promotes an agreement for public-private partnership in agrifood involving the university. A team of researchers from the university worked since 2009 with local businesses and communities on topics like territorial marketing, marketing of agri-food products, place branding and rural development. As outlined in Rinaldi and Cavicchi (Citation2016), the project Marche Excellence, a network of 13 companies with the primary aim to promote the territory of the Marche Region, originated from the interaction of several stakeholders that in 2009 established the Marche d’Eccellenza Forum, conceived as a “laboratory of ideas”, aimed at creating a centre for analysis and reflections on regional development and to promote the Made in Marche brand, reinforcing the regional identity and supporting local entrepreneurs. The tourism sector and all the related supply chains were also included. The idea firstly emerged in the context of the Tipicità Festival, a festival about agri-food and typical products from Marche existing for more than 20 years.

2010-2011 – Marche d’Eccellenza Forums - In 2010 the Marche d’Eccellenza Forum organized an event to discuss tourism development and the creation of a regional umbrella brand. The university played an important role in terms of expertise and provided opportunities for discussion and exchange. The participants discussed “network building” capability and the lack of clear leadership for the process of creation of an umbrella-brand, and the need for a “code of conduct” to guide collaboration (Cavicchi et al., Citation2013). A second Marche d’Eccellenza Forum was held in 2011, but the representatives of the regional government were absent and no workshops for discussion were held, nor was a “code of conduct” provided to the stakeholders.

2012 – Marche d’Eccellenza network contract. Even though policymakers were absent from the second Forum, a group of stakeholders decided to continue collaborating and created the Marche d’Eccellenza network contract, that can be considered the starting point for the university civic commitment. The university played a facilitator role, being a super partes entity that could observe, moderate and identify different needs emerging from involved actors.

2013 - the project Farm Inc., funded by the EU Leonardo Lifelong Learning Programme – Transfer of Innovation. The project involved the university and other European partners from Italy, Greece, Belgium, Latvia, Cyprus, and became a living lab where local university co-designed and co-created learning materials for an e-learning platform, in collaboration with local stakeholders.

2013- 2015 – “Gastronomic Cities” Project.

In 2013 the URBACT secretariat funded a European project, called “Gastronomic Cities”. The aim was to create a brand for cities based on gastronomy. the project was led by Burgos (Spain), which according to the URBACT framework, was considered a “giving” city, because it was the one transferring its best practices to other municipalities of the European Union (“receiving cities”). These receiving cities were L'Hospitalet (Spain), Alba Iulia (Romania), Korydallos (Greece) and Fermo (Marche, Italy).

URBACT tries to foster integrated and sustainable urban development through various actions (URBACT, Citation2013). First, receiving cities need to demonstrate through a feasibility plan how they share common characteristics with the giving city and how the giving city’s best practices can be adapted to local contexts. Other relevant actions include the facilitation of exchange of experiences and learnings among city policy-makers, decision-makers and practitioners, the dissemination of good practices and lessons drawn from these exchanges, ensuring the transfer of know-how, and assistance to policy-makers and practitioners in defining and implementing Local Action Plans (LAPs) with long-term perspectives. LAPs represent the final outcome of the whole project for city. This strategic document addresses the identified needs, analyses problems and puts forward feasible and sustainable solutions. To this purpose, the organisation of the basic units of collaboration, called URBACT Local Support Groups (ULSGs), is fundamental. Every city partner in an URBACT network has to manage such groups of stakeholders, engaged in order to participate in the development and implementation of urban development policies. Thus, the efficacy of stakeholders’ engagement is probably the most critical issue that needs to be addressed and monitored by cities.

The ULSG activities entailed the analysis of local challenges and seeking solutions, embedding the learning from the transnational exchange in the local policy-making process and contributing to the communication of results at the local level through a dissemination of learned lessons to the whole local community. Specifically, the Italian ULSG was involved in activities at the transnational and local levels, such as technical visits and staff exchanges performed according to different stakeholder categories (e.g. chefs; producers; policymakers).

The Italian city involved the university in the Marche region as a key stakeholder, represented in the project by two of this paper’s authors.

Specifically, the Fermo Local support group was involved in activities at the transnational and local levels.

Transnational activities

At the transnational level groups of stakeholders participated since the inception of the project in the following exchange activities:

Exchanges held in Burgos (giving city)

Burgos Deep Dive - Technical visit to the “city providing the practice”

First staff exchange - During “Devora es Burgos” – one of the most important gastronomic events happening in the giving city. Staff exchange involved mainly event organisers and managers

Second staff exchange - “Chefs Exchange”

Third staff exchange - “Zero Km producers exchange”

Transnational events organised in receiving cities.

The Fermo event was organised within “Tipicità 2014 Edition”, the long-lasting food and gastronomy event in the Marche region.

These exchange activities incorporated peer review exercises, field trips and study visits to facilitate the process of good practice transfer, by involving different stakeholder groups to each of the exchanges, such as policymakers, festival managers, chefs, producers, etc.

Local activities

At the local level, several meetings took place starting in February 2014 with the presentation of the project during the board of the local destination management organisation called “Marca Fermana” to inform the most relevant and influential public and private stakeholders about the purpose and methods of the project.

Facilitation of three multi-stakeholder meetings (ULSG meetings)

During the first formal ULSG meeting (3rd April, 2014), Burgos good practices were presented. A discussion regarding the weaknesses and strengths of Fermo Province and its relations with eno-gastronomic tourism was performed through the generation of a mind-mapping exercise.

In the second stakeholder meeting (20th June, 2014), a summary of the main exchange activities was presented by participants, sharing with local stakeholders their perspectives and starting a discussion about possible actions and activities to be implemented from the Burgos experience.