?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

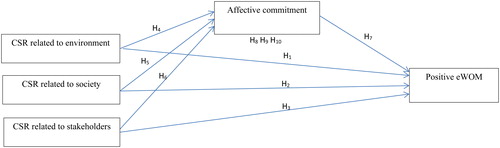

Although previous research establishes customer reactions to companies' corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions, little is known about the effect of CSR on customers’ affective commitment and their positive electronic word of mouth (eWOM). This study examines i) which perceptions of the three CSR activities (environment, society, and stakeholders) influence customers’ affective commitment and positive eWOM, and ii) the mediating effects of affective commitment on the relationships between CSR activities and eWOM. A self- administered survey was conducted on hotel customers in Malaysia and the data was analysed using structural equation modelling (CB-SEM). The results revealed that environment-related CSR and stakeholder related CSR have significant and direct impacts on customers’ eWOM, and demonstrated the mediating role of affective commitment between the three activities of CSR and eWOM. The findings can be interpreted using social exchange theory, and provide valuable insights regarding how CSR dimensions and affective commitment are related to customers’ positive eWOM in the hotel industry. Hoteliers shall benefit from understanding how specific CSR activities can enhance customers’ affective commitment, leading to positive eWOM.

Introduction

Environmental issues such as climate change and natural disasters have begun to make individuals more aware of the issues related to the earth (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2020; Martínez et al., Citation2014), with growing concern for its resources and inhabitants (Ghaderi et al., Citation2019; Ghosh et al., Citation2018). In the tourism industry, customers may have a positive attitude toward the environment without recognising the tension between environmental protection and their vacation behaviour (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). To reduce this cognitive distance and increase environmentally sustainable behaviour, service providers in the tourism industry can develop environmental initiatives, providing information about their ecofriendly practices. Juvan and Dolnicar (Citation2017), for example, conclude that customers wish to behave in ways that can reduce tourism’s negative environmental impact by staying in hotels that implement sustainable environmental practices. Environmental tourist self-identity is emerging as the strongest driver of specific sustainable tourist behaviour, needing more research into effective initiatives.

The growing awareness of this issue has led hoteliers to develop and promote social and environmental initiatives to attract travellers who are aware of their interest, manifest through CSR activities (Ghaderi et al., Citation2019; Martínez et al., Citation2018; Mohammed & Al-Swidi, Citation2019; Mohammed & Rashid, Citation2018; Palacios-Florencio et al., Citation2018). CSR concerns a firm’s activities and attitude in relation to its obligations towards the environment, stakeholders and the society in which it operates (Liu et al., Citation2014b). Online reviews can be used to assess customers’ level of CSR consciousness, expressed in their opinions about a hotel’s attention to CSR issues (D’Acunto et al., Citation2020). With the advent of social media, eWOM is regarded as a major driver of customers’ purchasing decisions in the hotel industry (Chen et al., Citation2015; Leong et al., Citation2019). It refers to either positive or negative comments on the products and services written and posted online by previous consumers, and is identified as a distinct aspect of behavioural intention (Abubakar & Ilkan, Citation2014; Huang, Weiler, and Assaker 2015). The current study focuses on positive eWOM as an aspect of behavioural intention, because understanding the motivation for positive eWOM is especially important for business owners. It is the most significant indicator of a product’s reputation, especially influencing consumers’ purchase decisions in the hospitality industry (Jeong & Jang, Citation2011; Xie et al., Citation2016).

While previous studies indicate that CSR initiatives have a direct influence on customers’ eWOM (e.g., D’Acunto et al., Citation2020; Jalilvand et al., Citation2017; Romani et al., Citation2013; Su et al., Citation2015), including in tourism and hospitality (Serra-Cantallops et al., Citation2018), few have investigated the influence of CSR as a multidimensional construct affecting customers’ eWOM (Bigné et al., Citation2020; Gil-Soto et al., Citation2019; Serra-Cantallops et al., Citation2018), and little is known about the underlying psychological mechanism of customer reactions (Markovic et al., Citation2018; Romani et al., Citation2013). In response to the need for such research, customers’ commitment has been suggested as a key mediator in the relationship between their perception and behavioural intention (Gil-Soto et al., Citation2019; Su et al., Citation2014; Xie et al., Citation2015). Affective commitment reflects the consumer’s sense of belonging and involvement with a service provider (Fullerton, Citation2003), and affectively committed customers spread their positive feelings about service providers to others (Harrison-Walker, Citation2001). In this case, Romani et al. (Citation2013) pointed out that customers’ affective commitment to a company’s CSR initiatives seems to be an important mechanism in understanding how and why CSR affects customers’ reactions. In this vein, key authors, such as Markovic et al. (Citation2018), Su et al. (Citation2017), Kim et al. (Citation2017), Jalilvand et al. (Citation2017) and Liu et al. (Citation2014a) have called for research to understand the influence of customers’ affective commitment to the CSR perceptions and their behavioural intention reflected in positive eWOM.

Therefore, the objectives of this study are twofold. The first is to examine how the environment, society, and stakeholder dimensions of CSR influence customers’ positive eWOM in the hotel sector. The second is to analyse the mediating influence of affective commitment on the relationship between the CSR dimensions and positive eWOM. Thus, the study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, it adds to previous findings about customers’ perception of CSR and their online reviews (eWOM) by investigating the influence of the three CSR dimensions (environment, society and stakeholders) on customers’ positive eWOM. Although previous studies have discussed the link between CSR and customers’ online reviews, the influence of CSR dimensions on eWOM remains neglected (Gil-Soto et al., Citation2019; Serra-Cantallops et al., Citation2018). Second, this study examines the mediating role of customers’ affective commitment on the relationship between CSR dimensions and positive eWOM as advocated by previous studies, such as Jalilvand et al. (Citation2017), Markovic et al. (Citation2018) and Su et al. (Citation2017). From a managerial perspective, the results give hoteliers opportunities to develop their marketing strategies by understanding their customers’ attention to environmental, social and stakeholder issues, consequently increasing their commitment and spreading positive eWOM about the hotel services provided.

The following sections present the literature review and hypothesis development, the research method used, the data analysis, discussion and implications, and finally, the conclusion with suggestions for future research.

Literature review and development of hypotheses

CSR activities and positive eWOM

eWOM is represented by online reviews offering consumers’ opinions about products, services or companies; they are a source of information independent of commercial influence between consumers and producers (Cantallops & Salvi, Citation2014; Leong et al., Citation2019). In this case, eWOM plays a particularly vital role in consumer purchasing decisions about hotel services, as intangibility makes the pre-purchase trial of services impossible (Jalilvand et al., Citation2017; Serra-Cantallops et al., Citation2018).

From the theoretical standpoint, this study uses the social exchange theory (SET) to explain the relationship between CSR activities and eWOM. A basic principle of SET is the exchange of benefits between two parties (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Specifically, one party voluntarily offers a benefit to another, and the other feels obliged to return that benefit (Whitener et al., Citation1998). In the hotel context, a social exchange-based mechanism suggests that CSR actions send signals to customers that hotels support their well-being; the customers feel obliged to reciprocate with positive attitudes and behaviours. Thus, as hotels provide benefits beyond their legal and financial obligations, customers translate their obligations towards these hotels in terms of positive WOM (Jalilvand et al., Citation2017).

Several major CSR categories have been considered in the literature, but most research focuses on environmental, societal, and stakeholder perspectives (Liu et al., Citation2014a; Torres et al., Citation2012); this study follows this categorization. Environmental CSR includes activities that are concerned with preventing environmental pollution, conserving energy and offering green production/services (Dahlsrud, Citation2008; Liu et al., Citation2014a). In considering the social perspective, Pinney (Citation2001) contends that CSR is looked at as a company’s management practices that aim to reduce negative operational impacts on society and maximize the company’s positive impacts. Societal activities include cultural promotion, philanthropy, sustainable development and public welfare contributions (Liu et al., Citation2014a). Woodward (1999) considered CSR from the stakeholder perspective, seeing it as a ‘contract’ between organizations and society through which organizations conduct the business by accepting some obligations and behaving acceptably. Stakeholder activities include returns to investors, community development, treatment of employees, and control and monitoring of suppliers’ behaviour (Dahlsrud, Citation2008).

Previous studies on CSR and customers’ online reviews/eWOM highlight the role of CSR activities (see ). For example, Su, Swanson, and Chen (Citation2015) investigated the influence of CSR as a unidimensional construct and found that it has a positive direct influence on word of mouth and an indirect influence through customer satisfaction. Jalilvand et al. (Citation2017) examined the influence of CSR on WOM in the hotel industry in Iran, and concluded that it is positively significant; WOM also has a mediating influence on the relationship between CSR and corporate reputation. With regard to the significant role of the environmental dimension of CSR, Bigné et al. (Citation2020) concluded from online reviews that it has a stronger influence on perceptions of helpfulness, influence and destination brand equity than the other dimensions.

Table 1. Recent key empirical studies on CSR and eWOM/ online review in tourism and hospitality sector.

Martínez et al. (Citation2018) also found that the higher the environmental consciousness of consumers, the greater their intention to spread positive WOM for environmentally certified hotels. Brazytė et al. (Citation2017) focused on a small sample of Costa Rican hotels with a sustainability certificate to explore how guests responded to sustainability efforts in their online reviews. They found that customers who explicitly recognized the sustainability measures implemented by a hotel tended to provide higher ratings in their reviews. Likwise, Ettinger et al. (Citation2018) analyzed guests’ comments on hotels’ CSR engagement in a small sample of Austrian hotels, showing that environmental issues and supplier relations attracted the most comments in customer reviews. Regarding the effect of social CSR activities on customers’ online reviews, Herrero and Martínez (Citation2020) found that social consciousness was a direct determinant of attitudes towards commenting on CSR news on Facebook and also positively influenced customers’ perception of information usefulness.

Other researchers investigated factors that would explain eWOM comments on Facebook with regard to negative CSR information, that is offering information about potentially irresponsible environmental behaviour. Herrero and Martínez (Citation2020), for example, found that environmental consciousness, like social consciousness, exerted a direct and positive infuence on attitudes towards sharing comments about CSR on Facebook, but that in this case not on perceived information usefulness. Grappi et al. (Citation2013) investigated consumer response to irresponsible corporate behaviour, and found that the more serious moral transgression, the more strongly users expressed negative WOM through contempt and outrage.

One longitudinal study, conducted by D’Acunto et al. (Citation2020) on the six top European destinations, found that hotel customers have gradually begun to pay more attention to CSR factors in their online reviews, particularly to social and environmental ones. When a hotel behaves in a manner that is perceived as philanthropic and ethical, guests are likely to conclude that it has certain desirable traits that resonate with their sense of self.

Regarding the link between stakeholders’ CSR activites and customers’ positive eWOM, Liu et al. (Citation2014b) found this to be more relevant, and therefore more valuable, to hoteliers. Vlachos et al. (Citation2009) similarly stated that CSR activities related to stakeholders could improve customer trust and reduce any scepticism about the organization, leading to stronger positive recommendations. Markovic et al. (Citation2018) found that corporate behaviours related to stakeholders were favoured by customers and considered as an important factor when making a purchase decision, as well as influencing their positive eWOM.

Overall, with respect to social exchange mechanisms, hotels implementing CSR initiatives send signals to customers that they are supporting their well-being; customers reciprocate with positive eWOM. We have applied the conclusions of major studies (Ettinger et al., Citation2018; Jalilvand et al., Citation2017; Markovic et al., Citation2018; Martínez et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2014, Citation2015) in focusing on the influence of CSR on customers’ online reviews. In sum, there is strong evidence of a positive relationship between CSR dimensions and positive e-WOM. Therefore, the following hypotheses are postulated:

H1. Customers’ perception of the hotel environmental CSR has a positive influence on their positive eWOM.

H2. Customers’ perception of the hotel social CSR has a positive influence on their positive eWOM.

H3. Customers’ perception of the hotel stakeholder CSR has a positive influence on their positive eWOM.

CSR activities and customers’ affective commitment

Affective commitment is defined as the customer’s emotional attachment to service providers that strengthens a sense of belonging and involvement with a brand or organization (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990; Fullerton, Citation2003; Su et al., Citation2017). In the hotel industry in South Korea, Kim et al. (Citation2017) found that employees’ CSR perception toward the organization and its activities positively affects their affective commitment. Su et al. (Citation2017) came to the same conclusion in China. Thus, hotel customers are likely to exhibit a high level of commitment toward a company when they have a positive perception of its CSR. Park and Levy (Citation2014) add that employees’ CSR perception in the hotel sector influences their organizational identification, which may be an antecedent of employee affective commitment, in turn predicting turnover intentions.

Moreover, Benavides-Velasco et al. (Citation2014) suggest that customers may show considerable commitment and supporting behaviours towards hotels that are socially responsible. Previous studies indicate that CSR activities can enhance customers’ affective commitment toward the organization (Bartikowski & Walsh, Citation2011; Servera-Francés & Arteaga-Moreno, Citation2015). Thus, customers’ CSR perception guides their affective commitment because CSR practices can reflect their relational and psychological needs (Hur et al., Citation2018). Sen and Bhattacharya (Citation2001) early indicated that positive perception of the CSR activities, environmental, social and stakeholders, is necessary to obtain a high level of commitment. Singh et al. (Citation2012) confirmed that customers are more likely to have affective commitment toward an organization which acts ethically towards its stakeholders. More recently, Markovic et al. (Citation2018), Hur et al. (Citation2018) and Engizek and Yasin (Citation2017) found that CSR activities positively influence customers’ affective commitment toward the organization. Thus, based on these arguments, the current study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4. Customers’ perception of the hotel environmental CSR has a positive influence on their affective commitment.

H5. Customers’ perception of the hotel social CSR has a positive influence on their affective commitment.

H6. Customers’ perception of the hotel stakeholder CSR has a positive influence on their affective commitment.

Affective commitment and positive eWOM

Customers with greater commitment toward service providers are more likely to tell people about the positive aspects of an organization (Bettencourt, Citation1997). Liu and Mattila (Citation2015) revealed that customers with high levels of affective commitment have strong intention to support the firm in improving its performance. Hence, hotel customers with a strong CSR commitment are more willing to share their positive perceptions with friends and family members (Su et al., Citation2014). This corroborates Tsao and Hsieh (Citation2012) conclusions that affectively committed customers intend to refer to an organization through positive eWOM communication. Nusair et al. (Citation2011) similarly found that affective commitment is positively linked to WOM communication. Thus, customers’ commitment towards a firm’s products and services has a significant impact on their subsequent behaviours (e.g. positive WOM) (Morales, Citation2005). We therefore hypothesize that:

H7. Customers’ affective commitment has a positive influence on their positive eWOM.

Mediating role of affective commitment

Generally, highly satisfied and affectively committed customers tend to promote the positive aspects of an organization with which they identify, and to spread positive WOM (Nusair et al., Citation2011; Tsao & Hsieh, Citation2012). Nusair et al. (Citation2011) argue that once generation Y, in particular, is affectively committed to web vendors as a result of their favourable attitude, they spread positive WOM. This is consistent with many previous studies that have argued that customers’ commitment to firms’ products and services leads to positive eWOM (Morales, Citation2005; Tsao & Hsieh, Citation2012).

After examining consumer responses to irresponsible corporate behaviour, Grappi et al. (Citation2013) found that favourable CSR activities enhance consumers’ gratitude and emotions, that is their affective commitment, leading to intention outcomes such as WOM. Romani et al. (Citation2013) similarly found that CSR positively affects consumers’ gratitude and positive WOM. Accordingly, it can be said that CSR activities can improve affective commitment because they strengthen customers’ favourable emotions and feelings toward that organization.

Previous studies have demonstrated that customers’ emotions can have a mediating role between their perception and behaviour (Gracia et al., Citation2011; Su et al., Citation2017). Recently, Hur et al. (Citation2018) found that customers’ affective commitment mediates the relationship between customers’ perception of CSR and their social behaviour towards firms. Moreover, based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response framework, Su et al. (Citation2017) argue that the CSR-related record of a company is seen as a social psychological stimulus that could help in directing customers’ emotions towards pro-environmental consumer behaviours. Other studies have proposed that a positive assessment of a firm’s CSR activities reinforces both internal and external commitment to it (Turban & Greening, Citation1997); subsequently, this behaviour is transformed into positive WOM and repeat purchase behaviour (Stanaland et al., Citation2011). For this reason, researchers such as John et al. (Citation2017) and Su et al. (Citation2017) have stated that an individual’s emotion (e.g. commitment) could act as a mediating factor between perception of CSR activities and behavioural attitudes and actions. Su et al. (Citation2017) also found that commitment has a partial mediating role between perceived CSR activities and customers’ green behaviour in the hotel sector, while Bartikowski and Walsh (Citation2011) found that CSR practices directly influence consumers’ commitment to the firm. Thus, customers with a strong affective commitment toward a hotel consider it not only as their first choice but also become more committed to promoting it among their friends and peers. In general, customers give positive references as a way of showing greater commitment to a company. When customers are committed, they tend to take the initiative in recommending it to others and talking positively about their experience (Tsao & Hsieh, Citation2012). This study therefore proposes the following hypotheses:

H8. Customers’ affective commitment plays a mediating role between their perception of the hotel environmental CSR and their positive eWOM.

H9. Customers’ affective commitment plays a mediating role between their perception of the hotel social CSR and their positive eWOM.

H10. Customers’ affective commitment plays a mediating role between their perception of the hotel stakeholder CSR and their positive eWOM.

Based on the hypothesis development, the proposed research framework is presented in .

Methodology

Measurements

To measure the constructs of the study, valid and reliable methods have been adapted from the literature: CSR dimensions from Liu et al. (Citation2014a); affective commitment from Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) and Engizek and Yasin (Citation2017); and positive eWOM from Tsao and Hsieh (Citation2012). All the constructs are reflective of their concept.

The study employs a standardized survey questionnaire to gather the data. The demographic section comprises the variables gender, age, duration of stay, demographic origin, occupation, and educational level. The second section contains the questions to measure affective commitment, the three CSR activities, and positive e-WOM. The responses were based on a seven-point Likert scale where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 7 represents “strongly agree”. To ensure content validity, three faculty members and ten graduate students on a hospitality management programme reviewed the preliminary questionnaire and provided comments and suggestions.

Population and sampling

Visitors to hotels in the most attractive islands of Malaysia, Penang and Langkawi, were the population of the current study. With the time and budget constraints, 3- to 5-star hotels in these two popular tourist destinations were identified from the Malaysian Association of Hotels website. These hotels were then checked by browsing their websites and inquiring by phone to learn if they had a formal CSR programme in place, such as the implementation of the 3 Rs practice of reduce, reuse and recycle; energy conservation; and contribution to the development of local communities.

Rejecting those with no formal CSR programme, 78 hotels were qualified for inclusion; 49 of these were visited. Employing the convenience sampling method, individual respondents were selected based on their willingness to participate and their familiarity with the hotel’s activities. In other words, every adult tourist waiting to check out was approached and asked if they would be willing to participate in the survey. To ensure respondents’ awareness of the hotel’s activities, the study also selected respondents who had stayed in that hotel previously. The survey was conducted during April and September 2017, periods in which several holidays including school, university and public holidays occur. Out of 450 questionnaires distributed, 389 were used for further analysis.

Data analysis and results

Statistical methodology

Structural equation modelling (SEM) has become popular in many fields (Hair et al., Citation2017); it has two approaches, CB-SEM, and PLS-SEM or VB-SEM. While PLS-SEM is a prediction-oriented approach primarily used for exploratory research, CB-SEM is preferred in cases confirming established theory (i.e., explanation). Hair et al. (Citation2017) suggest that PLS-SEM performs better in the structural model where the relative deviations in small sample sizes are comparable to those produced by CB-SEM for sample sizes of 250 to 500 when estimating factor model-based data. In earlier work, Hair et al. (Citation2010) suggested that CB-SEM can be used for a large sample size (more than 200) and (Hair et al., Citation2014) that it requires 5-10 observations per indicator. This makes the sample size requirements large even for relatively simple models. As our study uses only 24 indicators and the sample size is 389, the ratio of observations to indicators is 16 to 1, which exceeds the rule of thumb of 5-10 observations for each indicator. This study therefore adopts CB-SEM.

Sample profile

reports the profiles of the respondents. 71% were male, over half (57.6%) were aged between 26 and 40 years, 79.4% were foreigners and 56.1% stayed 3 to 4 nights in their hotel; 60.9% were in employment and 79% had college or undergraduate degrees. Based on these results, it can be seen that the majority of respondents were young and were therefore expected to use the Internet to search for data, and to be familiar with social media as a way of communicating with others. Given their stay of at least three nights, they were able to assess the CSR activities of their hotels.

Table 2. Sample distribution.

Measurement model analysis

To test the proposed model, SEM was applied using AMOS 21, the norm as suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988). The first step was to confirm the adequacy of the measurement model, and the second was to examine the proposed hypotheses.

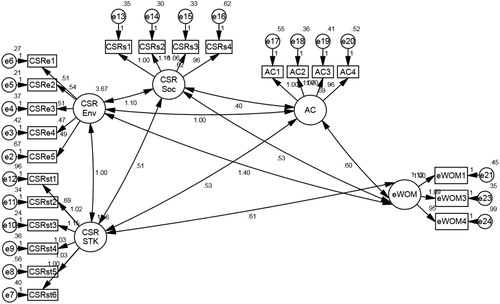

Construct validity of the measurement model was first established by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE). Discriminant validity was tested according to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion. shows the measurement model results.

Goodness of fit

To assess the model’s goodness of fit, different indicators were deployed. The standardized χ2 of the measurement model was 2.369, which is less than the 3.0 recommended by Bagozzi and Yi (Citation2012). The comparative fit index (CFI) was found to be 0.958, which exceeds the 0.95 suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (Citation2012). The non-normed fit index (NNFI or TLI), which was 0.951, confirmed that the model fits well the data. Furthermore, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.059, which is lower than the 0.08 proposed by Browne and Cudeck (Citation1993). Overall, these indicators established the goodness of fit of the measurement model. Next, the study established its content validity.

Content validity

In addition to the review of the preliminary questionnaire by three faculty members and ten graduate students on a hospitality management programme, the factor loadings were assessed to ensure content validity. As shown in the results in , the loadings of the variables were higher on their own constructs than on other constructs, supporting the content validity of the measurement model (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Table 3. Convergence validity analysis.

Construct validity

Construct validity is defined as the extent to which a set of items used to measure a construct appropriately measures that construct (Hair et al., Citation2010). It can be assessed by confirmation of convergent and discriminant validity, as follows:

Convergent validity analysis

Convergent validity is defined as the degree to which a set of items converges in reflecting the concept of the construct (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012; Hair et al., Citation2010). As the results in show, the factor loadings for all the items exceeded the value of 0.7 recommended in the SEM literature. Moreover, the values of composite reliability as shown in range between 0.858 and 0.933 which are all higher than the 0.7 suggested by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) and Hair et al. (Citation2010). Furthermore, to assess the shared variance among the sets of items designed to measure the constructs, the values of the average variances extracted (AVE) were assessed against the threshold value of 0.5 suggested by Barclay et al. (Citation1995). illustrates that the AVE values ranged between 0.606 and 0.711, confirming the convergent validity of the measurement model.

Table 4. Discriminant validity analysis.

Discriminant validity analysis

Discriminant validity is defined as the extent to which a group of variables meant to measure a construct can differentiate the construct from others in the model. To confirm the discriminant validity of the measures, the study followed the method suggested by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). As reported in , the diagonal elements representing the square root of AVE were higher than the other elements in the row and column in which they are located. This finding, therefore, confirmed the discriminant validity.

By confirming its convergent and discriminant validity, the measurement model was confirmed to have an adequate level of construct validity and reliability, thus guaranteeing that the results of the hypothesis testing will be valid and reliable.

Hypothesis testing results

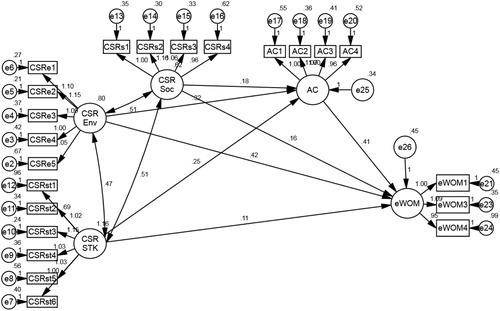

In assessing the structural model’s goodness of fit, all the indicators showed a good fit when compared to the cutoff values suggested by the SEM reporting standards. For example, the scaled χ2 was 2.369, which is less than 3.0; GFI was 0.902, higher than the cutoff value of 0.90; TLI was 0.951 and CFI 0.958, higher than 0.95; RMSEA was 0.059, lower than 0.08. Therefore, the model had adequate goodness of fit according to Bagozzi and Yi (Citation2012) and Kline (Citation2011).

The next step examined the hypothesized relationships, as illustrated in .

The statistical results confirmed that the environment and stakeholder dimensions of CSR, and affective commitment, have positive and significant impacts on positive eWOM (β = 0.416, LB= 0.242, UB= 0.576), (β = 0.107, LB= 0.002, UB= 0.216) and (β = 0.405, LB= 0.25, UB= 0.584) respectively. Thus, hypotheses H1, H3 and H7 are supported. Similarly, the results confirmed that all three CSR dimensions have positive and significant effects on affective commitment (β = 0.320, LB= 0.179, UB= 0.495), (β = 0.185, LB= 0.004, UB= 0.351) and (β = 0.247, LB= 0.147, UB= 0.341). These results support hypotheses H4 to H6.

The mediating role of affective commitment

One of the main objectives of the study was to investigate the mediating role of affective commitment between CSR dimensions and positive eWOM. The mediation analysis was examined by the bootstrapping methodology, as suggested by Hayes and Preacher (Citation2014) for results generated from 5,000 samples. As illustrates, the indirect effects were estimated and the confidence intervals calculated. Specifically, the indirect effects on the relationship between CSR related to the environment, society and stakeholders and positive eWOM were significant as zero was not included in any of the confidence intervals (a*b = 0.130, LB= 0.062, UB = 0.255), (a*b = 0.075, LB= 0.057, UB = 0.166) and (a*b = 0.100, LB= 0.01, UB = 0.172) respectively. Following the methodology suggested by Nitzl et al. (Citation2016), it was confirmed that affective commitment acts as a partial mediator between CSR related to the environment and stakeholders and positive eWOM, with VAF 24% and 48% respectively. However, affective commitment fully mediates only the relationship between CSR related to society and positive eWOM (VAF 32%). These results, therefore, suggest that affective commitment has a mediating role between CSR dimensions and positive eWOM, supporting hypotheses H8 to H10.

Table 6. The mediation analysis results.

CSR related to environment and stakeholders has a direct significant effect on positive eWOM, although CSR related to society does not (see ). Notable is also that CSR related to environment has a greater direct effect on positive eWOM (0.416) than CSR related to stakeholders (0.107). CSR related to environment, stakeholders and society has a direct effect on affective commitment. CSR related to environment has a greater direct effect on affective commitment (0. 320) than CSR related to stakeholders (0.2470) and CSR related to society (0.185). Affective commitment also has a direct significant effect on positive eWOM. Further, CSR activities related to environment, stakeholders and society have an indirect effect on eWOM through effective commitment. Affective commitment has a full mediation effect on the relationship between CSR related to society and positive eWOM, as compared to the partial mediation effect of affective commitment on the relationship between the environment and stakeholder CSR activities and positive eWOM. Overall, CSR dimensions and affective commitment were able to predict 59.5% (R2) of the variance in positive eWOM. The implications of these findings are discussed in the following section.

Table 5. Structural relationship results.

Discussion

The present study extends current research on customers’ online behaviour toward CSR activities in the hotel industry in two main ways. First, we sought to clarify how CSR dimensions (i.e., environment, society, and stakeholders) and customers’ positive eWOM are related. Second, the current study investigated the mediating role of affective commitment on the relationship between CSR dimensions and positive eWOM. The present study reported that CSR dimensions have direct and indirect influences on positive eWOM, and CSR related to society has only an indirect influence on positive eWOM. Our findings are best understood in the context of social exchange; according to Blau (Citation1964), in a social exchange, when a party voluntarily supplies a benefit to the other, it creates a feeling in the second party to reciprocate these voluntary actions. Therefore, CSR can stimulate social exchange processes between an organization and its customers (Glaveli, Citation2020). In particular, the findings indicate that CSR actions toward a customer incorporate the voluntary actions of a hotel that support their customers’ welfare and consider the environment and society; it is thus possible to motivate customers to feel obliged to pay back these voluntary investments in terms of affective commitment and positive eWOM.

As shown in , this study reveals that customers’ perception of the hotel’s environmental CSR has a positive influence on their positive eWOM. This evidence is consistent with previous contributions that have shown a link between CSR related to the environmental dimension and customers’ behavioural outcomes (Bigné et al., Citation2020; Ghaderi et al., Citation2019). In this case, because of increasing awareness of environmental issues in the global hotel industry, consumers display strong purchase intention and positive behaviour towards organizations that adopt environmentally friendly practices (Kasim, Citation2004). Also, the significant positive link between customers’ perception of the hotel stakeholder CSR and their positive eWOM confirms previous research that revealed how stakeholders’ CSR activities affect customers’ WOM (Liu et al., Citation2014b; Markovic et al., Citation2018). The explanation might be that customers, as hotel stakeholders, see CSR stakeholder activities relevant to themselves and therefore as more valuable (Liu et al., Citation2014b). On the other hand, the finding in the current study regarding the influence of customers’ perception of the hotel social CSR and their eWOM is inconsistent with previous studies such as D’Acunto et al. (Citation2020) and Herrero and Martínez (Citation2020). The non-significant link between society-related CSR and eWOM might be due to difficulty in evaluating this dimension because of its complexity and the lack of information available to hotel customers (Liu et al., Citation2014b). Thus, the hotels’ societal CSR practices (e.g. financial contributions to local cultural and social events) may not be readily perceived by customers in the Malaysian context; limited knowledge about CSR society activities may result in a lower level of sensitivity to the society-related dimension of CSR (Singh et al., Citation2008).

According to our findings there is a significant and positive influence of CSR dimensions on customers’ affective commitment. The results are in line with previous work by Hur et al. (Citation2018), Kim et al. (Citation2017) and Servera-Francés and Arteaga-Moreno (Citation2015), which concluded that customers show strong commitment to organizations when they perceive their CSR activities positively. That is to say, CSR dimensions are consolidated as an essential tool for developing customers’ commitment to the hotel sector. Since CSR activities build up the customer’s commitment to the organization, the customer feels more involved in the company and becomes a supporter, recommending it to other consumers. Furthermore, the findings of this study lend some supports to Tsao and Hsieh (Citation2012) and Nusair et al. (Citation2011) finding that affective commitment has a positive significant influence on spreading customers’ eWOM.

The findings revealed that customers’ affective commitment can play a mediating role between CSR activities and positive eWOM. This highlights the need to invest in developing affective customer commitment towards the firm (Singh et al., Citation2012) if hotels are aiming to leverage their investment in CSR activities, especially those activities related to society. The results also indicate that when consumers perceive their hotel as a positive CSR identity, they develop a strong affective commitment, and consequently will spread positive online comments about that hotel. Further, social exchange theory could explain the mediating influence of customers’ affective commitment in the relationship between CSR activities and their positive eWOM. The findings prove that customers who are affectively committed to a hotel through perceptions of its CSR activities tend to maintain mutually beneficial relationships, based on this theory.

Although this study provides valuable insight into the link between CSR dimensions, affective commitment and customers’ positive eWOM in the hospitality industry, there are some limitations. The first is the small number of hotels selected for the study sample, located in specific geographic areas of Malaysia (Penang and Langkawi). Due to the lack of a sampling frame, the study followed convenience sampling techniques to collect data from respondents, making it difficult to make generalizations based on the results. Future research should survey a broader sample of Malaysian accommodation and guest houses of different hospitality types, and could also be conducted across countries to validate the findings. Second, while the empirical model and theoretical framework have been carefully established, this study may still have ignored variables such as hotel size, level of service quality, perceived value and hotel brand image. Future studies could explore the impact of these variables on CSR activities to extend the empirical framework.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature both theoretically and empirically, since the aim of our research was to shed new light on the relationship between CSR dimensions, customers’ affective commitment and their positive eWOM, analyzing the mediating role of affective commitment. Additionally, it suggests a series of actions that hotel managers should follow in order to increase the positive effects of these variables. The current study makes several contributions to the literature on CSR and hotel customers’ eWOM.

From a theoretical perspective, first, there has been little research on the effects of CSR dimensions on customers’ eWOM (Gil-Soto et al., Citation2019; Markovic et al., Citation2018; Serra-Cantallops et al., Citation2018). Bigné et al. (Citation2020) commented that previous studies had linked CSR activities and customers’ online reviews when considering CSR as a unidimensional construct, highlighting the lack of studies investigating the different dimensions of CSR on travellers’ behaviour, with most focusing only on the environmental dimension. Therefore, the current study extends earlier findings by investigating CSR as a mutidimensional construct. Second, this study contributes to the current debate suggesting that not all CSR dimensions carry the same weight (Ettinger et al., Citation2018). We provide evidence that two of the CSR dimensions (stakeholder and environment) have significant direct and indirect impacts on positive eWOM. The findings also demonstrate that CSR related to society has no direct significant influence on customers’ positive eWOM, although it has an indirect influence through affective commitment.

Third, this study contributes to the field of CSR by providing empirical evidence for the indirect impact of CSR on eWOM, considering the mediating variable of customer affective commitment as recommended by previous studies (e.g. Su et al., Citation2014, Citation2017; Xie et al., Citation2015). As for indirect effects of CSR on customer behavioural intention, the literature suggests customers’ emotional variables as appropriate mediators. For example, prior research in the hospitality/services context found positive and indirect effects of ethical/CSR initiatives on customer loyalty, mediated by affective commitment (Markovic et al., Citation2018); and CSR indirectly influenced customer citizenship behaviour through affective commitment (Hur et al., Citation2018). In the same vein, CSR indirectly influences WOM, mediated by gratitude (Romani et al., Citation2013) and other emotions (Su et al., Citation2014). The results of our hypothesized model extend this list of relevant mediators by empirically showing that the impact of customer-perceived CSR activities on eWOM is mediated by customers’ affective commitment. This highlights the need to invest in developing customer affective commitment toward the hotel (Gil-Soto et al., Citation2019; Xie et al., Citation2015) if corporate services aim at leveraging their investments in CSR dimensions. In addition, by using the tenets of social exchange theory, this study fills a gap in the CSR literature by providing data indicating that the social exchange framework is appropriate for studying the link between CSR activities and customers’ eWOM behaviour in the hotel context. It explains why customers are willing to share positive eWOM about hotels and highlights the significant impact of drivers such as CSR activities and affective commitment that can be linked to the social exchange framework.

From the practical perspective, our findings have two important implications for hotel managers aiming to improve their customers’ affective commitment and gain positive eWOM. First, the results show that environmental and stakeholder CSR activities play a positive and significant role in customers’ positive eWOM. Hotel managers should invest more in socially responsible initiatives, especially environmental and stakeholder, to obtain higher levels of positive eWOM, as customers tend to reward socially responsible companies. In their communication campaigns, hoteliers should point out the advantages and values their hotels provide to customers and the environment. It is therefore important for hotel management to take appropriate actions and be more responsible in dealing with the consumption of energy and water, and changing their chemical-based cleaning products to more eco-friendly alternatives to minimize environmental impacts. Second, given that CSR activities have a stronger effect on customers’ positive eWOM through affective commitment, hotel businesses should allocate more resources to improving that commitment. They should put more effort into building a feeling of affective commitment among customers. To increase the level of commitment, hoteliers can provide adequate information about why they have focused on certain CSR activities (e.g., reducing waste, saving energy and water, donations to local projects, showing commitment to improving the community, and engaging in poverty alleviation campaigns). They need to advertise their activities and contributions to the public through all effective communication channels including social media, e.g. Facebook, Instagram, micro-blogs, Twitter, WeChat, and travel websites. These practices and policies consolidate the link between the customer and the hotel; thus, improvement in customers’ perception of the CSR practices developed by hoteliers should increase their commitment and motivate them to spread positive WOM about the hotel.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdulalem Mohammed

Dr. Abdulalem Mohammed is an assistant professor at the college of Science and Arts in Shaqra Unversity, Saudi Arabia. He holds a master of business adminstartion and a PhD from University Utara Malaysia. His research focus is on services management and marketing, consumer behavior, tourism and hospitality management, and corporate social responsibility. His research has been published in various international peer reviewed journals.

Abdullah Al-Swidi

Abdullah Kaid Al-Swidi is an Associate Professor of Management in the Department of Management and Marketing, College of Business and Economics, Qatar University. He holds a master degree of statistics and operations research from India and a Doctor of Business Administration from Malaysia. He supervised more than 17 PhD students working on different field such as business excellence and quality management and marketing among others. His research work revolves around business excellence, green operations and green behavior and has been published in various international peer reviewed journals. In addition to this, he has been a professional trainer and business consultant for companies and programs in Qatar, Malaysia and Yemen.

References

- Singh, J. J., Iglesias, O., & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2012). Does having an ethical brand matter? The influence of consumer perceived ethicality on trust, affect and loyalty. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(4), 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1216-7

- Abubakar, A. M., & Ilkan, M. (2014). eWOM and the 3W's: Who, why and what. Morebooks.

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (pls) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption ans use as an illustration.

- Bartikowski, B., & Walsh, G. (2011). Investigating mediators between corporate reputation and customer citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Research, 64(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.09.018

- Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Marchante-Lara, M. (2014). Total quality management, corporate social responsibility and performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.003

- Bettencourt, L. A. (1997). Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90024-5

- Bigné, E., Zanfardini, M., & Andreu, L. (2020). How online reviews of destination responsibility influence tourists’ evaluations: An exploratory study of mountain tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(5), 686–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1699565

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Brazytė, K., Weber, F., & Schaffner, D. (2017). Sustainability management of hotels: How do customers respond in online reviews? Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 18(3), 282–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2016.1230033

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136–136. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005

- Cantallops, A. S., & Salvi, F. (2014). New consumer behavior: A review of research one WOM and hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.08.007

- Chen, C. H., Nguyen, B., Klaus, P. P., & Wu, M. S. (2015). Exploring electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in the consumer purchase decision-making process: The case of online holidays–evidence from United Kingdom (UK) consumers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(8), 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.956165

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- D’Acunto, D., Tuan, A., Dalli, D., Viglia, G., & Okumus, F. (2020). Do consumers care about CSR in their online reviews? An empirical analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102342

- Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.132

- Engizek, N., & Yasin, B. (2017). How CSR and overall service quality lead to affective commitment: Mediating role of company reputation. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-09-2015-0135

- Ettinger, A., Grabner-Kräuter, S., & Terlutter, R. (2018). Online CSR communication in the hotel industry: Evidence from small hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 68, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.09.002

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement errors. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fullerton, G. (2003). When does commitment lead to loyalty? Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670503005004005

- Ghaderi, Z., Mirzapour, M., Henderson, J. C., & Richardson, S. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and hotel performance: A view from Tehran, Iran. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.007

- Ghosh, S. K., Islam, D., & Bapi, A. B. (2018). The relationship between CSR, PSQ and behavioral intentions of hotel customers in Bangladesh. Journal of Management, 12(1), 50–67.

- Gil-Soto, E., Armas-Cruz, Y., Morini-Marrero, S., & Ramos-Henríquez, J. M. (2019). Hotel guests’ perceptions of environmental friendly practices in social media. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.016

- Glaveli, N. (2020). Corporate social responsibility toward stakeholders and customer loyalty: Investigating the roles of trust and customer identification with the company. Social Responsibility Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-07-2019-0257

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Díaz-Fernández, M. C., & Font, X. (2020). Factors influencing willingness of customers of environmentally friendly hotels to pay a price premium. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2019-0147

- Gracia, E., Bakker, A. B., & Grau, R. M. (2011). Positive emotions: The connection between customer quality evaluation and loyalty. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 52(4), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965510395379

- Grappi, S., Romani, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2013). Consumer response to corporate irresponsible behavior: Moral emotions and virtues. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1814–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.002

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson.

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2).

- Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050141006

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028

- Herrero, A., & Martínez, P. (2020). Determinants of electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites about negative news on CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04466-9

- Huang, S., Weiler, B., & Assaker, G. (2015). Effects of interpretive guiding outcomes on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intention. Journal of Travel Research, 54(3), 344–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513517426

- Hur, W. M., Kim, H., & Kim, H. K. (2018). Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behaviour? The mediating roles of customer‐company identification and affective commitment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(6), 1258–1269. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1636

- Jalilvand, M. R., Nasrolahi Vosta, L., Kazemi Mahyari, H., & Khazaei Pool, J. (2017). Social responsibility influence on customer trust in hotels: Mediating effects of reputation and word-of-mouth. Tourism Review, 72(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2016-0037

- Jeong, E., & Jang, S. S. (2011). Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) motivations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(2), 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.08.005

- John, A., Qadeer, F., Shahzadi, G., & Jia, F. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and employee’s desire: A social influence perspective. The Service Industries Journal, 37(13–14), 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1353081

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2017). Drivers of pro-environmental tourist behaviours are not universal. Journal of Cleaner Production, 166, 879–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.087

- Kasim, A. (2004). Socio-environmentally responsible hotel business: Do tourists to Penang Island, Malaysia care? Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 11(4), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1300/J150v11n04_02

- Kim, H. L., Rhou, Y., Uysal, M., & Kwon, N. (2017). An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.10.011

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Leong, L. Y., Hew, T. S., Ooi, K. B., & Lin, B. (2019). Do electronic word-of-mouth and elaboration likelihood model influence hotel booking? Journal of Computer Information Systems, 59(2), 146–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2017.1320953

- Liu, S. Q., & Mattila, A. S. (2015). I want to help” versus “I am just mad” how effective commitment influences customer feedback decisions. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 56(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515570939

- Liu, M., Wong, I., Rongwei, C., & Tseng, T. H. (2014b). Do perceived CSR initiatives enhance customer preference and loyalty in casinos? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(7), 1024–1045. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2013-0222

- Liu, M., Wong, I., Shi, G., Chu, R. L., & Brock, J. (2014a). The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and perceived brand quality on customer-based brand preference. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(3), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-09-2012-0171

- Markovic, S., Iglesias, O., Singh, J. J., & Sierra, V. (2018). How does the perceived ethicality of corporate services brands influence loyalty and positive word-of-mouth? Analyzing the roles of empathy, affective commitment, and perceived quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2985-6

- Martínez, C. P., Herrero, C. A., & López, R. (2018). Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1160–1177. doi:10.1080/09669582.2017.1349775

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & Del Bosque, I. R. (2014). Exploring the role of CSR in the organizational identity of hospitality companies: A case from the Spanish tourism industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1857-1

- Mohammed, A., & Al-Swidi, A. (2019). The influence of CSR on perceived value, social media and loyalty in the hotel industry. Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC, 23(3), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-06-2019-0029

- Mohammed, A., & Rashid, B. (2018). A conceptual model of corporate social responsibility dimensions, brand image, and customer satisfaction in Malaysian hotel industry. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 39(2), 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2018.04.001

- Morales, A. C. (2005). Giving firm an “E” for effort: Consumer responses to high-effort firms. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 806–812. https://doi.org/10.1086/426615

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- Nusair, K., Parsa, H. G., & Cobanoglu, C. (2011). Building a model of commitment for Generation Y: An empirical study on e-travel retailers. Tourism Management, 32(4), 833–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.07.008

- Palacios-Florencio, B., García del Junco, J., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Rosa-Díaz, I. M. (2018). Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1273–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1447944

- Park, S. Y., & Levy, S. E. (2014). Corporate social responsibility: Perspectives of hotel frontline employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(3), 332–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2013-0034

- Pinney, C. (2001, June). More than charity: Building a new framework for Canadian private voluntary sector relations. Discussion Paper for Imagine’s Voluntary Sector Forum, Canadian Centre for Philanthropy, Toronto.

- Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2013). Explaining consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of gratitude and altruistic values. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1337-z

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.225.18838

- Serra-Cantallops, A., Pe ∼ na-Miranda, D. D., Ramon-Cardona, J., & Martorell-Cunill, O. (2018). Progress in research on CSR and the hotel industry (2006–2015). Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 59(1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965517719267

- Servera-Francés, D., & Arteaga-Moreno, F. (2015). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the customer commitment and trust in the retail sector. Ramon Llull Journal of Applied Ethics, 6, 161–178.

- Singh, J., Sanchez, M., & del Bosque, I. (2008). Understanding corporate social responsibility and product perceptions in consumer market: A cross-culture evolution. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(3), 597–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9457-6

- Stanaland, A. J. S., Lwin, M. O., & Murphy, P. E. (2011). Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0904-z

- Su, L., Huang, S., van der Veen, R., & Chen, X. (2014). Corporate social responsibility, corporate reputation, customer emotions and behavioral intentions: A structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of China Tourism Research, 10(4), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2014.958606

- Su, L., Swanson, S. R., & Chen, X. (2015). Social responsibility and reputation influences on the intentions of Chinese Huitang Village tourists: Mediating effects of satisfaction with lodging providers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(8), 1750–1771. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2014-0305

- Su, L., Swanson, S. R., Hsu, M., & Chen, X. (2017). How does perceived corporate social responsibility contribute to green consumer behavior of Chinese tourists: A hotel context. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(12), 3157–3176. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0580

- Torres, A., Bijmolt, T., Tribo, J., & Verhoef, P. (2012). Generating global brand equity through corporate social responsibility to key stakeholders. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2011.10.002

- Tsao, W. C., & Hsieh, M. T. (2012). Exploring how relationship quality influences positive eWOM: The importance of customer commitment. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 23(7-8), 821–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2012.661137

- Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–672. https://doi.org/10.2307/257057

- Vlachos, P. A., Tsamakos, A., Vrechopoulos, A. P., & Avramidis, P. K. (2009). Corporate socialresponsibility: Attributions, loyalty, and the mediating role of trust. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0117-x

- Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Jon, M. W. (1998). Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.2307/259292

- Woodward, C. (1999). Key opportunities and risks to New Zealand's export trade from green market signals. Final paper, Sustainable Management Fund Project 6117, New Zealand Trade and Development Board.

- Xie, C., Bagozzi, R. P., & Grønhaug, K. (2015). The role of moral emotions and individual differences in consumer responses to corporate green and non-green actions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(3), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0394-5

- Xie, K. L., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Singh, A., & Lee, S. K. (2016). Effects of managerial response on consumer eWOM and hotel performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 2013–2034. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2015-0290