Abstract

The Amboseli landscape in Kenya has long been facing persistent challenges regarding conservation and development. To mitigate these problems and contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), various policy interventions have been initiated, mostly in the form of partnership arrangements. This article examines two such partnerships, the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust (AET) and the Big Life Foundation (BLF), to understand how they contribute to the governance of the Amboseli landscape, and the intrinsic link to power and politics. The research findings, based on document analysis, interviews and focus-group discussions, reveal that the partnerships have performed complementing landscape governance roles. Whereas AET focused on policy development, agenda-setting and meta-governance, BLF concentrated on policy implementation and meta-governance in relation to wildlife security. The way the partnerships performed these governance roles can be explained through the four faces of power, which reveal BLF’s compulsory power and AET’s institutional power. Nevertheless, the partnerships have only partially managed to bridge conflicting conservation and development discourses illustrating that the concept of sustainable development appears to hold little productive power on the ground. Overall, the article provides important insights into the contributions that partnerships can make to the SDGs, but also their limitations.

Introduction

Poverty and loss of biodiversity are prominent global challenges that are intricately linked and mutually dependent. It is widely acknowledged that they ought to be addressed simultaneously, as recognised by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, when it adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that seeks to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 . It is also increasingly recognised that transformative change is needed to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Transformative change can be defined as a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values (IPBES, Citation2019). Such fundamental and structural change is called for, as current structures often hamper sustainable development and actually represent the underlying causes, or indirect drivers, of unsustainable development (Díaz et al., Citation2019; see also Boluk et al., Citation2019).

The SDGs represent current global effort towards sustainable development by reducing inequalities and ecological impacts, while securing resilient livelihoods (Fleming et al., Citation2017). The SDGs are closely linked to conservation, poverty and development issues, as exemplified by SDG-1, on ending poverty, SDG-3 on improving health and well-being, SDG-4 on quality education, and SDG-15 on life on land (UNDP, 2016). But, as clearly claimed through SDG-17, a successful sustainable development agenda requires partnerships between governments, the private sector and civil society. Such synergy allows SDGs to be addressed simultaneously, while trade-offs can be avoided (see for example, Gupta & Vegelin, Citation2016).

Conservation and development are thus integrative and require a holistic approach (Caiado et al., Citation2018) by multiple actors in partnerships. Partnerships are promoted as instruments for improved governance (Brinkerhoff, Citation2007), sustainable development (Mert, Citation2015; Mert & Pattberg, Citation2015; UNDP, 2016) and more specifically in achieving the SDGs (Beisheim et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, governance for sustainable development is increasingly based on partnership arrangements (Beunen & Opdam, Citation2011; Paavola, Citation2007). Examples in sub-Saharan Africa vary from conservancies in Namibia and conservation enterprises in Kenya and Uganda (Van der Duim et al., Citation2015, Citation2017) to partnerships focusing on entire landscapes such as the Laikipia Wildlife Forum and the Northern Rangelands Trust (see Pellis et al., Citation2015) and the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust in Kenya. Many of these integrate tourism as an avenue for livelihood improvement (Nthiga et al., Citation2015). Although various authors have examined how effective partnerships are in governing sustainable development (Nthiga et al., Citation2015; Visseren-Hamakers, Citation2009), there is limited understanding of how partnerships contribute to governing landscapes. Moreover, in governance and partnerships literature, power has often been neglected as a useful concept in analysing and understanding landscape governance processes. Governance and partnerships tend to be presented as depoliticised and consensual policy-making by interdependent actors in power-free processes (Kuindersma et al., Citation2012).

Therefore, this article explores two of these landscape-wide partnerships – the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust (AET) and the Big Life Foundation (BLF) – in one of the most renowned wildlife-based tourism destinations: the Amboseli landscape in Kenya. Our study aimed to understand: i) how AET and BLF govern the Amboseli landscape with the goal to address persistent conservation and livelihood challenges, and ii) how such governance is intrinsically linked to power and politics. To analyse the two partnerships, the article amalgamates literature on partnerships, governance, power and landscapes into a landscape governance perspective.

This article proceeds as follows. We will first introduce the Amboseli landscape and the two partnerships, after which we will present our landscape governance perspective and methods used. We will then examine the landscape governance roles fulfilled by the partnerships in the results section and end with broader discussions on the role of partnerships in landscape governance and a brief conclusion.

The Amboseli landscape and its partnerships

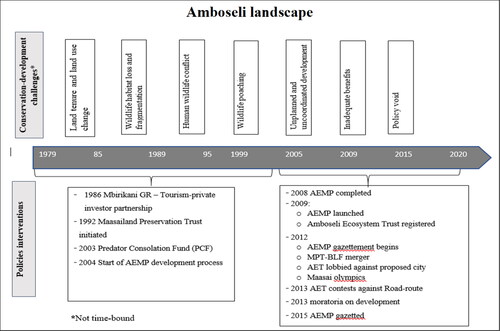

The Amboseli landscape in Kenya covers an area of over 500,000 ha. The core of the landscape is a 392 km2 protected area – Amboseli National Park (ANP) – sandwiched between six group ranches (GRsFootnote1): Mbirikani (MGR), Kuku (KUKU-GR), Kimana (KGR), Olgulului (OL-GR), Rombo (R-GR) and Eselengei (ES-GR) (see ). The national park accounts for about 5 per cent of the required wildlife habitat, making it too small to support its vibrant wildlife populations (BurnSilver, Citation2009; BurnSilver et al., Citation2008). Consequently, community group ranches serve as extended wildlife habitat and migratory corridors (Okello et al., Citation2009). This extension is possible because of the communal land tenure of group ranches and the predominant pastoralismFootnote2 land-use practiced by Maasai communities.

Figure 1. The Amboseli landscape and its location in Kenya (adopted from Okello et al., Citation2011).

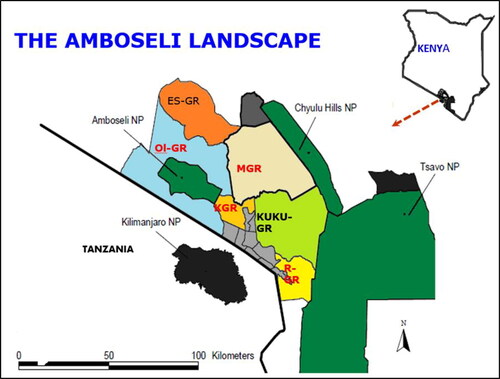

The Amboseli landscape has faced fundamental and persistent conservation and development challenges for decades (Western, Citation2007). Since the 1980s there has been a gradual change in land tenure, because group ranches have been subdivided into smaller individual and privately-owned parcels of land (Western et al., Citation2009b). Changing land tenure aggravated an array of interlinked conservation and development challenges that include changing land use (Kioko & Okello, Citation2010), human-wildlife conflicts (Okello, Citation2005), wildlife habitat loss and fragmentation (Western, Citation2007), poaching (AET, Citation2014a), unplanned and uncoordinated (tourism) development, a conservation-development policy void, and inadequate income from wildlife conservation for communities. Land use changed from pastoralism to include others (such as crop farming, mining), which compete and/or conflict with wildlife conservation (see Ntiati, Citation2002; Western et al., Citation2009a). Changing land use also led to human settlements and the development of tourism facilities in fragile wildlife habitat and migratory areas. As a result, wildlife habitat decreased and traditional wildlife migratory corridors between Amboseli and neighbouring protected areas were disconnected (BurnSilver et al., Citation2008; Ole Seno, Citation2012; Western et al., Citation2009b), leading to more human-wildlife conflicts (Okello et al., Citation2010). Accordingly, the Amboseli National Park is under threat of insularisation, and the communities have fewer opportunities to provide for their livelihoods. Despite incurring high costs that come with co-existing with wildlife, the local communities do not receive adequate benefits, and are generally poor, with over 50 per cent of the communities neighbouring the Amboseli National Park living below the poverty lineFootnote3 (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007). Human population growth only adds to the challenges.

To mitigate these challenges, various policy interventions have been implemented over time (Western, Citation2007). The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), for instance, shares benefits from the entrance fees for Amboseli National Park through the support of educationFootnote4 in the six group ranches. Other policy interventions include land lease and concession fees provided by conservancies, community tourism enterprises, predator compensation programmes that pay consolation fees for livestock killed or injured by predators (Anyango-Van Zwieten et al., Citation2015), community centred wildlife security programmes, and community livelihood support programmes . A common factor in many of these partnership-based interventions is the integration of tourism as a crucial link between communities’ livelihoods and conservation (Van der Duim et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). Although the Kenyan government and many NGOs, like the African Conservation Center (ACC) and the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), have been active in Amboseli for several decades, AET and BLF have specifically come to the fore in the last decade, which makes them interesting cases for this study (see also Mugo et al., Citation2020).

The AET is a landscape-based partnership registered in 2009 that brings together stakeholders in Amboseli with the aim to implement the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan (AEMP). The AEMP is a policy document developed by the AET that identifies the course Amboseli stakeholders intend to follow for a period of 10 years (2008–2018Footnote5) with the goal to ensure that wildlife continues to thrive and to improve community livelihoods (AET, Citation2009a). The key components of the AEMP include a detailed land-use zonation plan aimed at separating conflicting land uses (AET, 2014c) and management programmes outlining what the AEMP seeks to achieve:

Ecological management programme aimed at maintaining Amboseli landscape as a “key wildlife conservation area” (AET, Citation2009a:x) by securing critical wildlife dispersal areas, corridors and habitats, and protect wetlands and river systems (AET, Citation2009a);

Tourism development and management programme, aimed at ensuring that Amboseli sustains tourism destination competitiveness by promoting sustainable development (AE, 2009a; AET, Citation2014b);

The community partnership and education programme aimed at encouraging and inculcating a culture for sustainable livelihoods and conservation and management of wildlife outside Amboseli National Park, mainly on community owned land, by enhancing incentives to communities, and reducing “cost of living with wildlife by implementing prudent measures to manage the escalating human-wildlife conflict” (AET, Citation2009a:xi; 2014b);

Security programme, which aims to enhance and sustain the Amboseli landscape wildlife and visitor security through close collaboration with all the stakeholders, by improving a) security operations for the protection of AE’s wildlife resources, b) the effectiveness of natural resource protection, and c) the safety of visitors, KWS staff and assets (AET, Citation2009b);

Ecosystem operation programme aimed at improving service delivery by KWS staff and conservation partners within and outside the Amboseli National Park by formalising and strengthening institutional collaborations, improving the welfare and performance of KWS staff, and enhancing management infrastructure in the landscape (AET, Citation2009a; Citation2009b).

The AEMP was developed using the Protected Area Planning Framework (PAPF), a planning tool KWS uses as a management planning standard for protected areas (KWS, Citation2017). The plan was launched in 2009 and thereafter, the planning taskforce reconstituted to form the AET. The AET is run by a Board of Trustees (BoT) consisting of the partners listed in .

Table 1. AET partners.

The BLF is an AET partner and a member of the AET Board of Trustees. This foundation is the product of a successive evolution from a 3-phased partnership arrangement spanning the Mbirikani GR and the Amboseli landscape over the last three decades. The first phase started in 1986 when a partnership between the Mbirikani GR community members and a private tourism investor, Bonham Safaris, was initiated. During the second phase, this partnership evolved into the Maasailand Preservation Trust (MPT), a partnership between Ol donyo Wuas TrustFootnote6 and the Mbirikani GR community members that ran between 1992 and 2012. In 2012, which marked the start of the third phase, MPT merged its activities into the BLF, a conservation NGO registered in the United States of America. BLF runs conservation-development initiatives in collaboration with local communities, NGOs and the government in the Amboseli landscape in Kenya and in northern Tanzania. For purposes of this study, all phases of the partnership are referred to as BLF. BLF has implemented policy interventions over its entire lifespan, including a wildlife conservation and security programme, a Predator Compensation Fund (PCF), a wildlife education bursary, health care, the so-called Maasai Olympics and women empowerment projects (as elaborated below) (Figure 2).

Theoretical framework

In order to explain the landscape governance roles of AET and BLF, we first used the multi-dimensional perspective on power introduced by Kuindersma et al. (Citation2012), based on the fourfold taxonomy of power by Barnett and Duvall (Citation2005). Both employ multiple conceptions of power from different scientific paradigms and offer an integrated framework in which different power perspectives are viewed as complementary rather than conflicting. First, compulsory power is about the direct control of one actor over the conditions of existence and/or the actions of another, either intentionally or unintentionally, through the use of resources, such as money, manpower or knowledge (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005). We therefore wanted to know which stakeholders had control over which resources. Second, institutional power is about actors’ control of others in indirect ways. The conceptual focus of institutional power is on formal and informal institutions that shape agenda-setting processes in ways that deal with or eliminate the very issues that are points of conflict by mediating between actors (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005). Related, we analysed which actors set the agenda with the aim of changing the institutional setting (Kuindersma et al., Citation2012). Third, structural power refers to the structures “that define the kind of social beings actors are. It produces the very social capacities of structural, or subject, positions in direct relation to one another, and the associated interests that underlie and dispose action” (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005, pp. 52–53). Structural power is not about the control of one actor over another, it focuses on the social production of ‘power to’ and questions what structural subject positions are given (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005). Finally, productive power is the “socially diffuse production of subjectivity in systems of meaning and signification” (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005: 43), through scientific and societal discourses, that include some subjects or identities, and exclude others (Kuindersma et al., Citation2012). In this article, we analyse the relevant discourses and the kinds of subjects or identities that are produced by these discourses (Kuindersma et al., Citation2012). Although discussed here as distinct types of power, they are intertwined and have blurred boundaries; one type of power may enable or disable another.

Second, to analyse the role of partnerships in landscape governance we based ourselves on the work of Görg (Citation2007), van Huijstee et al. (Citation2007) and Visseren-Hamakers (Citation2013). Landscapes are socially and culturally constructed entities (Arts et al., Citation2017; Görg, Citation2007; van Oosten & Hijweege, Citation2012) that provide and support opportunities for and fulfil multiple needs of diverse actors (Antrop, Citation2006; McShane et al., Citation2011; Sayer et al., Citation2013). A landscape can be defined as a social-biophysical construct that bridges “social scales and the biophysical conditions and ecological processes in spaces” (Görg, Citation2007, p. 955). Given this multifunctional character, supporting multiple actors with multiple and diverse interests (Sayer et al., Citation2013), landscapes create the need for governance. Following Görg (Citation2007), this article defines landscape governance as the manner in which actors – in our case partnerships – steer and shape the Amboseli landscape. Partnerships are defined as collaborative arrangements between multiple actors from public, private and/or civil society sectors, who work towards solving specific societal problems and/or issues of mutual concern, often in the context of sustainable development (van Huijstee et al., Citation2007). Partnerships are viewed as specific forms of governance (Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2007), attributed with problem-solving capacity (Bitzer et al., Citation2013). We define governance as modes of steering in which multiple societal actors organise themselves, and are involved in making and implementing decisions with the aim of addressing societal problems (de Loë et al., Citation2009; Kersbergen & Waarden, Citation2004; Rosenau & Czempiel, Citation1992).

Partnerships fulfil several landscape governance roles, such as agenda-setting, policy development, information sharing, capacity building, implementation, and meta-governance ( Selsky & Parker, Citation2005; van Huijstee et al., Citation2007; Visseren-Hamakers, Citation2013; Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2012). Through these landscape governance roles, partnerships have the ability to address challenges related to sustainable development in complex landscapes (Lamers et al., Citation2014; Nthiga, Citation2014). However, partnerships are also criticised as being elitist (Dubbink, Citation2013), exclusionary and favouring the interests of specific partners (Rhodes, Citation1997). To understand how the analysed partnerships contribute to the governance of the Amboseli landscape, we examined the landscape governance roles they fulfil based on existing governance literature ().

Table 2. Landscape governance roles of partnerships.

Methods

A case study research design was used for this research (Yin, Citation2009). The article is based on primary and secondary data. Data collection and data analysis were carried out concurrently and continued for most of the study period, from August 2012, when a scoping mission was conducted, to August 2018Footnote7. The study area and the case studies were selected purposively. Specifically, the choice of the Amboseli landscape was informed by the fact that it offers a perfect example of a multifunctional landscape – with multiple actors, interests and challenges. It is also one of the first areas in Kenya for which an integrated landscape management plan was developed. We used a snowball sampling technique to recruit participants for in-depth interviews and focus-group discussions (FGDs). Primary data was collected using 75 in-depth interviews from 55 interviewees () and findings were triangulated with four FGDs (), four non-participant observations (), and around 30 informal conversations. FGDs were conducted with community members of the Mbirikani community, owing to the fact that the BLF originally started in the Mbirikani GR. The group ranch is also representative of most conservation-development challenges and policy interventions in Amboseli. To ensure inclusivity, two of the four FGDs were women-only, another one was with Maasai youth (young men aged between 18 and 35 years), and the last one was conducted with men over 35 years of age. In addition, the researchers observed four other meetings.

Table 3. Interviews and interviewees.

Table 4. Focus group discussions.

Table 5. Non-participant observations.

To supplement and validate the interview findings, secondary data was collected through the analysis of policy documents, which provided useful information on the partnerships’ implications for biodiversity conservation and people’s livelihoods in the Amboseli landscape. Data collection continued until data saturation was reached, so when we were confident that no new information was being obtained from respondents (Green & Thorogood, Citation2013).

Where possible, interviews and FGDs were recorded, while field notes were taken at all times. During interviews we spoke Kiswahili, ‘Maa’ and English languages. Being a non-Maasai speaker, the first author engaged the services of a ‘Maa’ speaking Maasai research assistant from Amboseli who also doubled as a guide during data collection. The research assistant-cum-guide acted as an interpreter to translate ‘Maa’Footnote8 to English or Kiswahili and vice versa during interviews and FGDs when the need arose, and also helped the first author to easily gain access to the community respondents and gain their trust (Green & Thorogood, Citation2013).

Clearly, being an outsider, data unavailability and data confidentiality played a role, especially regarding access to sensitive information about the management and distribution of financial benefits among group ranch members. Accordingly, some respondents did not permit the recording of interviews, and seemed more at ease when discussing issues in informal conversations and/or telephone conversations as opposed to formal interviews. In order to ensure that respondents remained anonymous and information provided remained confidential, interviews were coded and named using abbreviations ‘Inv-1′ through to ‘Inv-55′, focus group discussions numbered ‘FGD-1′ to ‘FGD-4′, and observations referred to as ‘Obser-1′ to ‘Obser-4′. Data analysis involved a thematic content analysis which involved transcription of in-depth interviews and FGDs. Each transcription was analysed and coded – through colour-highlighting and labelling – in order to distil emerging themes relevant to the study. Themes were then compared and related, or grouped according to their coding; this further grouping being based on literature (Green & Thorogood, Citation2013), until no new themes or groupings came up.

Results

The landscape governance roles of AET

The most tangible output of the governance roles performed by AET is the policy development of the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan (AEMP) (see ). The aim of the AEMP was not only to bring about a discursive shift to overcome conflicting policies resulting from Kenya’s sectoral-based policy development, but also to provide a legal framework for addressing persistent conservation-development challenges. Clearly, the development of the AEMP gave rise to AET’s meta-governance role, as demonstrated by the coordination and collaboration of AET partners with regards to conservancy leases. By coordinating the acquisition of land for conservation, the resulting conservancies created a ‘patchwork’ of areas that together represent important wildlife migratory corridors. AET-partners, such as the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), negotiated adjacent leases in order to create the Kitenden Corridor Conservation Area (KCCA) in the Olgulului GR, thereby increasing the area of land under biodiversity conservation use and improving wildlife habitat connectivity between Amboseli National Park in Kenya and Kilimanjaro National Park in Tanzania. AET and its partners have also been instrumental in maintaining connectivity of the wildlife migration corridor between Amboseli and Chyulu National Parks through a series of conservation land leases that BLF inherited in 2017 after the AWF left the area in 2016 due to inadequate funding.

Table 6. Landscape governance roles fulfilled by the partnerships.

However, the AEMP development process dragged for more than 4 years as a result of tensions and power struggles. At the very beginning, the African Conservation Center (ACC) proposed to develop an integrated management plan. Stakeholders then came together to form the planning taskforce (that later became the AET) that provided important historical data on conservation and livelihoods, and funded the AEMP process as well as AET’s operational costs. During the AEMP development and implementation process, the AWF, Kenyan Wildlife Services (KWS), BLF, and the Amboseli/Tsavo Group Ranch Conservation Association (ATGRCA) came to the fore. While the ACC continued to support AET activities and capacity building among communities, specifically the AWF took a leading role in habitat extension by creating community wildlife conservancies through land leases. Meanwhile, BLF focused on wildlife security issues outside government-run protected areas.

The development of the AEMP also involved internal and external agenda-setting. Internal agenda-setting is illustrated in the way the stalling of the AEMP development process was handled. The local communities perceived the land-use zonation plan as a conspiracy from NGOs and the government (the KWS) to convert their land into protected areas. They protested against an attempt to launch the AEMP in 2008 without the community partners’ consent, arguing that the AEMP prioritised wildlife conservation over livelihood improvement. In both instances, consultative meetings between the planning taskforce and the community partners were held to iron out conflicting views, thereby jump-starting the AEMP development process and strengthening the community livelihood component in the AEMP, leading to its eventual launch in 2009. However, the AEMP only partially facilitated a discursive shift towards integration of conservation and development goals in an integrated landscape perspective. This is also illustrated by the little progress that was made in addressing land tenure and land-use change that threaten conservation and development goals. Specifically, our findings reveal non-adherence to the AEMP zonation plan where crop farming continues in fragile wildlife habitats such as wetlands. Local communities continue to cultivate crops in non-agricultural zones, because they can earn more income with it in the short term. This reduces wildlife habitat connectivity and increases human-wildlife conflictsFootnote9 (HWC). Non-adherence to AEMP zonation shows that there are conflicting views and interests among AET partners in the landscape, and that local communities only partially embrace their newly assigned subject positions as landscape stewards.

AET also performed an external agenda-setting role in the period between the launch of the AEMP in 2009, and when it was enshrined in Kenyan law in 2015. During this period, AET, through its Board of Trustees, made concerted efforts to uphold and defend the landscape as an integrated and holistic system. Other notable examples are the instances where AET defended the landscape by successfully petitioning the government against planned development projects that threatened to disrupt the landscape. Specifically, in 2012, the AET successfully lobbied against the construction of a planned town next to Amboseli National Park. Thereafter, in 2013, AET contested a proposed route of an all-weather road linking Namanga to Loitoktok townships, after which the route was altered. In both instances, AET based their argument on the AEMP – to highlight that the planned town and road would interfere with important wildlife habitats and migratory routes and limit dry-period livestock grazing areas in the landscape.

However, further control of AET over developments in Amboseli was restricted, because only the government has the power to make laws. The fact that the plan was not recognised under Kenyan law for years hampered its implementation. Consequently, in 2012, AET began the process of gazetting the AEMP by convening a series of meetings for its partners to discuss its requirements. A stakeholder workshop involving all stakeholders in the Amboseli landscape was convened in February 2013. The intention was to create awareness of the AEMP’s viability as a tool for mitigating the fundamental and long-term challenges facing the Amboseli landscape. After the workshop, a moratorium on development was put in place for a period of one year and/or until the AEMP was gazetted, thereby outlawing all new forms of development projects in the landscape subject to approval by AET for compliance with the AEMP’s land-use zonation plan (Inv-1). The AEMP was gazetted on 30 October 2015 under the Kenya Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (GoK, Citation2015).

The landscape governance roles of BLF

Although BLF at first primarily worked together with the Mbirikani GR and later contributed to the work of AET by supporting the AEMP development and implementation process, its role has gradually become more influential. This dominant position of BLF is mainly because of its annual budget of around US$3,5 million, funded through donor funds from over 150 partners that include Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, United Nations Development Programme, Global Environment Facility, US Agency for International Development and the Disney Conservation Fund (BLF, Citation2018). BLF contributes to policy implementation through the Predator Compensation Fund (PCF), health and education programmes and coordination of wildlife security through the Wildlife Security and Conservation Program (WSCP). The WSCP was initiated in the Mbirikani GR by the Ol donyo Wuas Trust in the late 1980s as a response to increased wildlife poaching for bush meat and trophies (Inv-29). The WSCP is executed through an elaborate network of community wildlife game scouts – young Maasai from Amboseli – whose number has grown from 4 in 1993 when the programme began to over 300 in 2018 (BLF, Citation2018; Inv-29; Inv-30). Most scouts patrol the area on foot and are backed up by 14 patrol vehicles, 2 tracker dogs and 2 planes for aerial surveillance (BLF, Citation2020). Once apprehended, poaching suspects are handed over to the KWS for prosecution. The role of BLF is a supporting one, it provides witnesses, for instance.

Through the WSCP, BLF also performs a meta-governance role, as it coordinates a network of over 30 partners in Amboseli in Kenya and the transboundary landscape that extends into Tanzania (see BLF, Citation2019). For example, partners of AET (ACC, IFAW, and AWFFootnote10) support the WSCP by seconding their community wildlife game scouts to BLF, which manages their daily activities. The partners then still pay the wages of the scouts. Through the WSCP, BLF directly addresses human-wildlife conflicts and poaching in the Amboseli landscape, thereby supporting AET’s aims and the Security Programme of the AEMP. As a result, there has been a general drop in cases of poaching in BLF areas of operations outside formal protected areas. Although our analysis shows that BLF has become a crucial actor in Amboseli, the durability of its operations in the longer term remains uncertain owing to the fact that most of their policy interventions (such as the Predator Compensation Fund) solely depend on donor funding, which is indefinite (Anyango-Van Zwieten et al., Citation2015). Also, the PCF is not undisputed; there are tensions between BLF and some community members who feel that the current structure of BLF side-lines them (Inv-25b).

Relations of power

Our analysis of the governance roles of AET and BLF, using the multi-dimensional perspective on power (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005; Kuindersma et al., Citation2012), reveals complex power relationships among the actors, which include all four types of power (see ). Through these power relationships, actors shape the partnerships and the governance roles they fulfil.

Table 7. Main power relations.

AET can be best understood as an arena where power and power relationships are enacted. Different types of power have shaped the landscape governance roles of the partnership with regards to various issues over time. Moreover, the power relationships among the partners enable the AET to perform its different landscape governance roles or prevent it from doing so. For example, through institutional power enabled by the AEMP, AET has been able to play important agenda-setting and meta-governance roles. However, AET depends on individual partners for on-the-ground implementation of policy interventions, owing to their compulsory power because of the resources they control (funding, manpower, knowledge et cetera), thereby shaping the characteristics and focus of the partnership. Membership to the AET also strengthens partners’ positions. An important example is BLF, which plays a major meta-governance role in wildlife security matters in the transboundary area that the Amboseli landscape is part of, but which is still fully dependent on the mandate of government agencies such as the KWS for the prosecution of poaching suspects. This agency influences the AET and the Amboseli landscape through a combination of its structural position in society (owing to its mandate as a government parastatal), and its relative abundance of resources (manpower, expertise and knowledge) in formulating conservation area management policies and plans. In developing the AEMP, AET had to apply the national Protected Area Policy Framework (PAPF) giving KWS a relatively large influence on the development and implementation structure of the AEMP and on the work of AET and BLF.

Compulsory power therefore continues to play an important role in the partnerships and landscape. For the classic power question ‘who wins?’ (see Kuindersma et al., Citation2012), not only KWS but also BLF seems to be a suitable answer. BLF can only play its dominant role in wildlife security because of its significant financial resources. Lack of funding forced AWF to halt its operations that included wildlife habitat and security activities in the landscape, while availability of funding enabled BLF to take over some of the conservancies’ leases.

Our analysis also shed some particular light on the role of communities. First, the fact that the Maasai communities own the land outside of the protected areas enables them to ignore the rules of the AEMP (when it is convenient or beneficial), as illustrated by the continued expansion of crop farms in wetland areas contravening the AEMP’s zonation planFootnote11, which has a tremendous impact on biodiversity conservation. Second, while the development of the AEMP by AET provided a mechanism for local communities to become actively involved in governing the landscape, this study reveals examples of exclusion. Despite the fact that migrant communities represent a significant interest because of the way they use the landscape – cultivating crops, which exacerbates wildlife habitat loss and human wildlife conflicts – they are excluded from the AET. The AET Trust Deed (AET, Citation2009b) and the Group Representative Act of 1968 (BurnSilver & Mwangi, Citation2007) define membership to the AET in terms of group ranch members, thereby ignoring migrants. Third, local communities are also underrepresented in BLFs top decision-making level since the Maasailand Preservation Trust merged its activities into BLF, and the organisational set-up evolved from a partnership into an NGO. Accordingly, although local populations in theory have been given a new structural position as landscape stewards, their participation in the governance remained limited despite the fact that they actually own the land. Similarly, women are underrepresented. As has been the practice in most African cultural settings, Talle (Citation1999) points at gender inequality in social relations among Maasai communities. Maasai women have been excluded from decision making (Hodgson, Citation2005) and accruing benefits (Stewart-Phelps et al., Citation2013). For example, Maasai women are excluded from membership of group ranches (Nthiga, Citation2014). Moreover, it is argued that the Maasai culture is imbued with patriarchy, where men have a monopoly on decision-making, while women and young men have limited opportunity to own or claim resources – such as land and livestock (Ondicho, Citation2012). However, with increased access to education, awareness and capacity building, Archambault (Citation2016) asserts that the roles of Maasai women have been shifting and they are playing greater roles in for example raising livestock. In our research we found that women are represented in the AET Board of Trustee (BoT) meetingsFootnote12, implying that they are involved in AET operations, and hence in the governance of the Amboseli landscape. However, it is not clear if or how their involvement in AET translates on the ground. Although individual partners of AET (e.g. ACC, BLF, AWF) have set up projects to improve the livelihoods of women and to ensure women benefit from tourism as illustrated by BLF support offered to two BOMA women’s groups in the Mbirikani GR.

Finally, the above clearly illustrates the continued dominance of the ‘conservation versus development’ discourse, despite decades-long efforts to promote the sustainable development discourse that proposes that conservation and development can go hand in hand. Although at the global level the sustainable development discourse dominates, also through the SDGs, the trade-offs between conservation and development are so clear in the Amboseli landscape that the concept of sustainable development appears to hold little productive power on the ground. The AET partners can clearly be divided into coalitions that prioritise either conservation or development and show fluidity in their position in these debates, since they play various shifting roles, adding another layer to the complexity of the power relationships. Community members, for example, are often farmers or pastoralists, representing development discourses, but are also active in AET or BLF as partners, and involved in policy discussions or implementation of conservation efforts (e.g. as wildlife scout). Furthermore, while the government (KWS) is an active partner in the AET, the latter successfully lobbied against plans of the same government to develop a town and road in the area.

Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we examined two partnerships in Amboseli – the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust (AET) and the Big Life Foundation (BLF) – blending a landscape governance approach with the multi-dimensional perspective on power introduced by Kuindersma et al. (Citation2012) and Barnett and Duvall (Citation2005). What are the main lessons learned?

First, our analysis demonstrates that partnerships can play prominent and complementary roles in landscape governance. In our case we showed how AET has focused on policy development, agenda-setting and meta-governance, while BLF concentrated on policy implementation and meta-governance in relation to wildlife security. While AET’s key governance processes have first and foremost enabled deliberation and decision-making resulting in the AEMP, it depends on AET partners for implementation of the plan, notably and increasingly BLF (see Dentoni et al., Citation2018). However, in most cases partnerships are only able to effectively fulfil their governance roles with support of the government. Governing landscapes through partnerships is in actual sense about ‘governance with government’, denoting that the government is a dominant and essential partner in landscape governance. In Amboseli, by using the Protected Area Policy Framework, AET relied on government institutions in the development and gazettement of the plan. BLF needs the government to effectively protect wildlife, since governmental agencies prosecute poaching suspects. Accordingly, the success of BLF in wildlife security can partly be credited to the compulsory power of the government, enabled by authoritative enforcement. These findings therefore reiterate sentiments by authors who argue that even in instances where the government has shared power with other societal actors, the state always retains authority and control in new governance arrangements (Airey & Chong, Citation2010; Bell & Hindmoor, Citation2009). Interestingly, in the Amboseli case, the Kenyan government has on several occasions also bowed to the partnerships’ authority, illustrated by instances when AET prevented large government projects (the proposed town and road route). This finding echoes sentiments by some authors that shifting authority from government to partnerships enhances the position of other actors in decision-making (see McAllister & Taylor, Citation2015) and reduces state influence.

Second, the article shows that power is in fact an essential concept in analysing and understanding the role of partnerships in landscape governance processes, “that power is now more diffuse” (see Boluk et al., Citation2019: 857) and that policy is not limited to ‘public policy’. Critics of partnerships argue that these favour specific interests (Rhodes, Citation1997), may lead to power imbalances (Visseren-Hamakers, Citation2009), and may favour ‘capable’ partners, thereby excluding others in governance processes (Bitzer & Glasbergen, Citation2015; Bowen & Ebi, Citation2015). This study reveals that a fruitful analysis of power in landscape governance should surpass the realist perspective on power in terms of material resources and also include other faces of power that focus on institutions and agenda-setting, socio-economic structures, and ideas and perspectives (Kuindersma et al., Citation2012). As we have shown, the power relationships in the landscape are multi-dimensional, with all four types of power playing a role, and are multi-directional, with different partners dominating on different issues or over time. These complex power relationships have shaped the partnerships and their governance roles in the landscape. While BLF’s dominant position is predominantly based on their financial resources, AET has mediated between different actors and has been able to control agenda-setting aiming to change the institutional setting. However, both partnerships have only been able to bridge the conservation and development discourses to a certain degree, and thus have only partly been able to structurally change the positions of local communities involved.

In relation to the extent to which structural positions have changed, this article therefore raises questions related to the extent of change. Recently Dentoni et al. (Citation2018) suggested that partnerships can address complex societal problems, in our case the conservation-development nexus in Amboseli, by triggering or contributing to systemic change. The persisting challenge that remains, however, is whether partnerships trigger or support breadth and depth of change to an extent that adequately addresses these complex, fundamental societal problems (Waddock et al., Citation2015). In relation to Amboseli we argue that AET and BLF have supported systemic change as their work involves interconnected change across multiple spheres and subsectors as they have targeted conservation, development, tourism, agriculture, health, and education. This has been referred to as breadth of change (Waddell et al., Citation2015). In the case of Amboseli, clear differences in values between stakeholders and power struggles over the nature of the problems have been brought to the table and negotiated to find a temporarily acceptable synthesis in the AEMP (see Dentoni et al., Citation2018). However, systemic change should also entail a power shift among actors in society and a related redistribution of resources in a system. One could therefore really question to what extent AET and BLF have been able to address the necessary depth of change. The persistent poverty, conflicts with community members that halted the AEMP process, the continuous role of the Kenyan government in legitimising wildlife security programmes and the intensification of crop farming raises questions of whether AET and BLF, as forms of collaborative governance, have been fully able to tackle the complex challenges that Amboseli faces. This debate about breadth and depth of change is fully in line with discussions on the need for transformative change to achieve the SDGs (Díaz et al., 2019; Visseren-Hamakers, Citation2020). While the partnerships are able to contribute to addressing direct drivers of biodiversity loss (such as human wildlife conflicts, poaching), they contribute to a much lesser extent to addressing the indirect drivers, such as poverty and land subdivision. More generally speaking, partnerships represent policy arenas where different interests are negotiated and trade-offs between SDGs are brought to the surface. The added value of the partnerships comes from their fulfilment of important meta-governance roles through which partners’ views of the landscape (at least to a certain extent) converge and are shaped and re-shaped through actors’ practices. However, the two examples in Amboseli show that power struggles and power vacuums may seriously affect the capacity of partnerships to strengthen and secure the SDG agenda.

The above makes clear that our findings are not unique for the Amboseli case. The tendency to integrate landscape approaches by initiating partnerships is not only growing in Kenya (see Pellis et al., Citation2015), but also more broadly in Africa and around the world (see Van der Duim et al., Citation2015, Citation2017) in recognition of the need for “balancing multiple objectives, equitable inclusion of all relevant stakeholders, dealing with power and gender imbalances, adaptive management based on participatory outcome monitoring, and moving beyond existing administrative, jurisdictional, and sectorial silos” (Ros-Tonen et al., Citation2018, p. 11). However, it is increasingly clear that partnerships and integrated approaches such as landscape governance often struggle to do just that – maybe because they are unable to address the underlying causes of poverty and biodiversity loss. This makes more focused research on partnerships that govern landscapes rather urgent (ibid, p. 3). A central question is, then, whether, how, and the extent to which landscape governance through partnerships can evolve further to contribute to the transformative change needed to achieve the SDGs (Visseren-Hamakers, Citation2020; see also Mugo et al., Citation2020). Most probably, they will always need to be seen as part of ‘smart policy mixes’ (IPBES, Citation2019), in which different governance instruments together can address the indirect drivers underlying sustainability issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tabitha Mugo

Tabitha Mugo is a lecturer in the Department of Tourism Management, School of Tourism, Hospitality & Events Management, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya. Tabitha’s research interests revolve around partnerships and sustainability in tourism, biodiversity conservation and community development. She is currently pursuing her PhD studies at Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands.

Ingrid Visseren-Hamakers

Ingrid Visseren-Hamakers serves as chair of the Environmental Governance and Politics (EGP) group at the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment of the Institute of Management Research at Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Her research is especially focused on transformative global environmental governance and aims to contribute to both academic and the societal debates on how societies and economies can become sustainable, and how such transformative change is, and can be, governed.

Rene van der Duim

Rene van der Duim is Emeritus Professor Tourism and Sustainable Development at the Cultural Geography Chair Group, Department of Environmental Sciences at Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands. His research focuses on the relation between tourism, conservation and development, and he has executed research projects in countries like Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania Costa Rica, Portugal and the Netherlands.

Notes

1 Group Ranches are large parcels of land that provide a communal land tenure (Wayumba & Mwenda, Citation2006).

2 Pastoralism is a practice that involves rearing livestock (in this case cattle) that move from one location to another, based on seasonal availability of pasture and water (Catley et al., Citation2013).

3 International Poverty Line has a value of US$1.90 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) (Ferreira et al. Citation2016).

4 KWS shared Kshs. 20 million in 2013 (+/- USD 200,000).

5 In 2018, AET received an extension of the AEMP till 2020 to allow for a review of the plan. A revised management plan (2019-2029) was ratified in December 2019 (ACP, Citation2020).

6 Ol donyo Wuas Trust was the tourism-private-investor based NGO that fundraised and supported conservation and livelihood programmes in the Mbirikani Group Ranch.

7 Follow-ups on in-depth interviews through informal telephone conversations and secondary data continued until May 2020.

8 Interestingly, most Maasai respondents preferred to air their views in Maa even when they were eloquent in both English and Kiswahili.

9 Human wildlife conflicts involve wildlife destroying crops, preying on livestock, injuring or killing humans, and people killing and/or injuring wildlife in retaliation attacks (Western et al., Citation2009b).

10 Until 2016.

11 Land use is also influenced by other policies, such as the Water Act 2012 and the Environmental Act EMCA (1999).

12 Attendance to 4 out of 5 AET-BoT meetings had a woman representative.

13 Game rangers

14 Invited to the AET Board of Trustees when necessary.

References

- ACP. (2020). Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 ratified and adopted. Amboseli Conservation Program. http://www.amboseliconservation.org/news–commentaries/amboseli-ecosystem-management-plan-2020-2030-ratified-and-adopted.

- AET. (2009a). Amboseli ecosystem management plan: 2008–2018. Amboseli Ecosystem Trust.

- AET. (2009b). Declaration of trust establishing the amboseli ecosystem trust. Amboseli Ecosystem Trust.

- AET. (2014a). Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the amboseli ecosystem management plan (2008–2018). Amboseli Ecosystem Trust.

- AET. (2014b). Amboseli ecosystem trust strategic plan 2014–2019. Amboseli Ecosystem Trust.

- Airey, D., & Chong, K. (2010). National policy-makers for tourism in China. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.09.004

- Antrop, M. (2006). Sustainable landscapes: Contradiction, fiction or utopia? Landscape and Urban Planning, 75(3–4), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.02.014

- Anyango-Van Zwieten, N., van der Duim, V. R., & Visseren-Hamakers, I. J. (2015). Compensating for livestock killed by lions: Payment for environmental services as a policy arrangement. Environmental Conservation, 42(4), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892915000090

- Archambault, C. (2016). Re-creating the commons and re-configuring maasai women’s roles on the rangelands in the face of fragmentation. International Journal of the Commons, 10(2), 728–746. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.685

- Arts, B., Buizer, M., Horlings, L., Ingram, V., Oosten, C. v., & Opdam, P. (2017). Landscape approaches: A state-of-the-art review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 439–463. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060932

- Barnett, M., & Duvall, R. (2005). Power in international politics. International Organization, 59(01), 39–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050010

- Beisheim, M., Ellersiek, A., Goltermann, L., & Kiamba, P. (2018). Meta‐governance of partnerships for sustainable development: Actors' perspectives from Kenya. Public Administration and Development, 38(3), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1810

- Bell, S., & Hindmoor, A. (2009). Rethinking governance: The centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press.

- Beunen, R., & Opdam, P. (2011). When landscape planning becomes landscape governance, what happens to the science? [Landscape and Urban Planning at 100. Landscape and Urban Planning, 100(4), 324–326. ]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.01.018

- Bitzer, V., & Glasbergen, P. (2015). Business–NGO partnerships in global value chains: Part of the solution or part of the problem of sustainable change? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 12, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.08.012

- Bitzer, V., Glasbergen, P., & Arts, B. (2013). Exploring the potential of intersectoral partnerships to improve the position of farmers in global agrifood chains: findings from the coffee sector in Peru. Agriculture and Human Values, 30(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-012-9372-z

- BLF. (2018). Annual report 2018 (p. 12). Big Life Foundation. https://biglife.org/images/operational-reports/BLF-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

- BLF. (2019). Big Life Foundation report July - September 2019. https://biglife.org/images/about-big-life/OperationalReports/BLF_Quarterly_Report_-_Q3_2019.pdf

- BLF. (2020). Big Life Foundation. https://biglife.org/

- Boluk, K. A., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the united nations sustainable development goals 2030 agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Bowen, K. J., & Ebi, K. L. (2015). Governing the health risks of climate change: Towards multi-sector responses. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 12, 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.12.001

- Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2007). Partnership as a means to good governance: Towards an evaluation framework. In P. Glasbergen, Frank Biermann, & A. P. J. Mol (Eds.). Partnerships, governance and sustainable development: Reflections on theory and practice (pp. 68–98). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- BurnSilver, S., & Mwangi, E. (2007). Beyond group ranch subdivision: collective action for livestock mobility, ecological viability, and livelihoods (No. 577-2016-39153). International Food Policy Research Institute.

- BurnSilver, S. B., Worden, J. S., Boone, R. B. (2008). Processes of fragmentation in the Amboseli ecosystem, Southern Kajiado District, Kenya. In K. A. Galvin, R. S. Reid, R. H. Behnke Jr, & N. T. Hobbs (Eds.), Fragmentation in semi-arid and arid landscapes (pp. 225–254). Springer.

- BurnSilver, S. B. (2009). Pathways of continuity and change: Maasai livelihoods in Amboseli, Kajiado District, Kenya. In Staying maasai? (pp. 161–207). Springer.

- Caiado, R. G. G., Leal Filho, W., Quelhas, O. L. G., de Mattos Nascimento, D. L., & Ávila, L. V. (2018). A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 1276–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.102

- Catley, A., Lind, J., & Scoones, I. (2013). Pastoralism and development in Africa: Dynamic change at the margins. Routledge.

- Crabbé, A., & Leroy, P. (2012). The handbook of environmental policy evaluation. Earthscan.

- de Loë, R. C., Armitage, D., Plummer, R., Davidson, S., & Moraru, L. (2009). From government to governance: A state-of-the-art review of environmental governance. Final Report. Prepared for Alberta Environment, Environmental Stewardship, Environmental Relations. Rob de Loë Consulting Services.

- Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V., & Schouten, G. (2018). Harnessing wicked problems in multi-stakeholder partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(2), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3858-6

- Derkx, B., & Glasbergen, P. (2014). Elaborating global private meta-governance: An inventory in the realm of voluntary sustainability standards. Global Environmental Change, 27, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.016

- Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E., Ngo, H., Guèze, M., Agard, J., Arneth, A., Balvanera, P., Brauman, K. A., Butchart, S. H. M., Chan, K. M. A., Garibaldi, L. A., Ichii, K., Liu, J., Subramanian, S. M., Midgley, G. F, Miloslavich, P., Molnár, Z., Obura, D., …., Zayas, C. N. (2019). IPBES, Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Advance unedited version. Plenary of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Seventh session, Paris, 29.

- Dubbink, W. (2013). Assisting the invisible hand: Contested relations between market, state and civil society. (Vol. 18). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Ferreira, F., Jolliffe, D. M., & Prydz, E. B. (2016). The international poverty line has just been raised to $1.90 a day, but global poverty is basically unchanged. How is that even possible? World Bank Blog: Let’s Talk Development. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/international-poverty-line-has-just-been-raised-190-day-global-poverty-basically-unchanged-how-even

- Fleming, A., Wise, R. M., Hansen, H., & Sams, L. (2017). The sustainable development goals: A case study. Marine Policy, 86, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.09.019

- Gemmill, B., & Bamidele-Izu, A. (2002). The role of NGOs and civil society in global environmental governance. In D. C. Esty & M. H. Ivanova (Eds.), Global environmental governance: Options and opportunities (pp. 77–100). Yale University of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

- GoK. (2015). Economic Survey Report. Government Printers.

- Görg, C. (2007). Landscape governance: The “politics of scale” and the “natural” conditions of places. [Pro-poor water? The privatisation and global poverty debate]. Geoforum, 38(5), 954–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.004

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2013). Qualitative methods for health research. Sage.

- Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9323-z

- Hodgson, D. L. (2005). The church of women: gendered encounters between Maasai and missionaries. Indiana University Press.

- IPBES. (2019). Global assessment report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 2019. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

- Kersbergen, K. V., & Waarden, F. V. (2004). Governance’ as a bridge between disciplines: Cross-disciplinary inspiration regarding shifts in governance and problems of governability, accountability and legitimacy. European Journal of Political Research, 43(2), 143–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00149.x

- Kioko, J., & Okello, M. M. (2010). Land use cover and environmental changes in a semi-arid rangeland, Southern Kenya. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 3(11), 322–326.

- Kuindersma, W., Arts, B., & van der Zouwen, M. (2012). Power faces in regional governance. Journal of Political Power, 5(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.735116

- KWS. (2017). Protected Area Management Plans. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://www.kws.go.ke/content/protected-area-management-plans-0

- Lamers, M., van der Duim, R., van Wijk, J., Nthiga, R., & Visseren-Hamakers, I. (2014). Governing conservation tourism partnerships in Kenya. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.07.004

- Manyara, G., & Jones, E. (2007). Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 628–644. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost723.0

- McAllister, R. R. J., & Taylor, B. M. (2015). Partnerships for sustainability governance: A synthesis of key themes. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 12, 86–90. doi: . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.01.001

- McShane, T. O., Hirsch, P. D., Trung, T. C., Songorwa, A. N., Kinzig, A., Monteferri, B., Mutekanga, D., Thang, H. V., Dammert, J. L., Pulgar-Vidal, M., Welch-Devine, M., Peter Brosius, J., Coppolillo, P., & O’Connor, S. (2011). Hard choices: Making trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biological Conservation, 144(3), 966–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.038

- Mert, A. (2015). Environmental governance through partnerships: A discourse theoretical study. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mert, A., & Pattberg, P. (2015). 11 Public–private partnerships and the governance of ecosystem services. In J. A. Bouma & P. van Beukering (Eds.), Ecosystem services: From concept to practice (pp. 230–249). Cambridge University Press.

- Mugo, T., Visseren-Hamakers, I., & van der Duim, V. R. (2020). Contributions of partnerships to conservation and development: Insights from Amboseli. Tourism Review International (forthcoming).

- Nthiga, R. (2014). Governance of tourism conservation partnerships: Lessons from Kenya [PhD]. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Nthiga, R. W., van der Duim, V. R., Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., & Lamers, M. (2015). Tourism-conservation enterprises for community livelihoods and biodiversity conservation in Kenya. Development Southern Africa, 32(3), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2015.1016217

- Ntiati, P. (2002). Group ranches subdivision study in Loitokitok division of Kajiado District, Kenya. Land Use Change Impacts and Dynamics (LUCID) Project Working Paper, 19. African Wildlife Foundation.

- Okello, M. M., Kiringe, J., & Kioko, J. (2010). The dilemma of balancing conservation and strong tourism interests in a small national park: the case of Amboseli, Kenya. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 12(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580408667224

- Okello, M. M. (2005). Land use changes and human–wildlife conflicts in the Amboseli Area, Kenya. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 10(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200590904851

- Okello, M. M., Seno, O., Simon, K., & Nthiga, R. W. (2009). Reconciling people's livelihoods and environmental conservation in the rural landscapes in Kenya: Opportunities and challenges in the Amboseli landscapes. Natural Resources Forum, 33(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2009.01216.x

- Okello, M. M., Buthmann, E., Mapinu, B., & Kahi, H. C. (2011). Community opinions on wildlife, resource use and livelihood competition in Kimana Group Ranch near Amboseli, Kenya. The Open Conservation Biology Journal, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874839201105010001

- Ole Seno, S, K. (2012). Local communities’ perceptions on and expectations of conservation initiatives in the Amboseli Ecosystem. The Journal of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Makerere University, 11(2), 16–29.

- Ondicho, T. G. (2012). Local communities and ecotourism development in Kimana, Kenya. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/39064

- Paavola, J. (2007). Institutions and environmental governance: a reconceptualization. Ecological Economics, 63(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.09.026

- Pellis, A., Lamers, M., & van der Duim, R. (2015). Conservation tourism and landscape governance in Kenya: The interdependency of three conservation NGOs. Journal of Ecotourism, 14 (2-3), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1083028

- Pinkse, J., & Kolk, A. (2012). Addressing the climate change—sustainable development nexus: The role of multistakeholder partnerships. Business & Society, 51(1), 176–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650311427426

- Rhodes, R. A. (1997). Understanding governance: Policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. Open University Press.

- Rosenau, J. N., & Czempiel, E.-O. (1992). Governance without government: Order and change in world politics (Vol. 20). Cambridge University Press.

- Ros-Tonen, M. A., Reed, J., & Sunderland, T. (2018). From synergy to complexity: The trend toward integrated value chain and landscape governance. Environmental Management, 62(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1055-0

- Sayer, J., Sunderland, T., Ghazoul, J., Pfund, J.-L., Sheil, D., Meijaard, E., Venter, M., Boedhihartono, A. K., Day, M., Garcia, C., van Oosten, C., & Buck, L. E. (2013). Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(21), 8349–8356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210595110

- Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31(6), 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279601

- Stewart-Phelps, L., Johnson, P. S., Harvey, J., & Coppock, D. L. (2013). Foreword: Women as change agents in the world's rangelands. Rangelands, 35(6), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.2111/RANGELANDS-D-13-00057.1

- Stone, M. T. (2015). Community empowerment through community-based tourism: The case of Chobe Enclave Conservation Trust in Botswana. In V. R. van der Duim, M. Lamers, & J. van Wijk (Eds.), Institutional arrangements for conservation, development and tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa (pp. 81–100). Springer.

- Talle, A. (1999). Pastoralists at the border: Maasai poverty and the development discourse in Tanzania. In D. Anderson & V. Broch-Due (Eds.), The poor are not us (pp. 106–124). James Currey.

- Van der Duim, R., Lamers, M., & van Wijk, J. (2015). Institutional arrangements for conservation, development and tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa. Springer.

- Van der Duim, V. R., van Wijk, J., & Lamers, M. (2017). 13 Governing nature tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa. In J. S. Chen & N. K. Prebensen (Eds.), Nature tourism (pp. 146–158). Routledge.

- van Huijstee, M. M., Francken, M., & Leroy, P. (2007). Partnerships for sustainable development: A review of current literature. Environmental Sciences, 4(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15693430701526336

- van Oosten, C. J., & Hijweege, W. L. (2012). Governing biocultural diversity in mosaic landscapes Forest-people interfaces (pp. 211–222). Springer.

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. (2009). Partnerships in biodiversity governance: An assessment of their contributions to halting biodiversity loss. Nederlandse geografische studies (Vol. 387, pp. 1–177). KNAG.

- Visseren-Hamakers, I., & Glasbergen, P. (2007). Partnerships in forest governance. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.11.003

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. J. (2020). The 18th sustainable development goal. Earth System Governance, 3, 100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100047

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., Arts, B., & Glasbergen, P. (2007). Partnership as governance mechanism in development cooperation: Intersectoral North-South partnerships for marine biodiversity. MA. Edward Elgar.

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., Leroy, P., & Glasbergen, P. (2012). Conservation partnerships and biodiversity governance: fulfilling governance functions through interaction. Sustainable Development, 20(4), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.482

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. J. (2013). Partnerships and sustainable development: the lessons learned from international biodiversity governance. Environmental Policy and Governance, 23(3), 145–160.

- Waddell, S., Waddock, S., Cornell, S., Dentoni, D., McLachlan, M., & Meszoely, G. (2015). Large systems change: An emerging field of transformation and transitions. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2015(58), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2015.ju.00003

- Waddock, S., Meszoely, G. M., Waddell, S., & Dentoni, D. (2015). The complexity of wicked problems in large scale change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(6), 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-08-2014-0146

- Wayumba, R. N., & Mwenda, J. N. (2006, March 8–11). The impact of Changing land tenure and land use on wildlife migration within group ranches in Kenya: A case study of the amboseli ecosystem. 5th FIG Regional Conference, Accra, Ghana.

- Western, D. (2007). A half a century of habitat change in Amboseli National Park, Kenya. African Journal of Ecology, 45(3), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00710.x

- Western, D., Russell, S., & Cuthill, I. (2009a). The status of wildlife in protected areas compared to non-protected areas of Kenya. PLoS One, 4(7), e6140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006140

- Western, D., Groom, R., & Worden, J. (2009b). The impact of subdivision and sedentarization of pastoral lands on wildlife in an African savanna ecosystem. Biological Conservation, 142(11), 2538–2546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.05.025

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research, design & methods (4th ed.). Sage.