Abstract

The digital information age has changed global tourism in profound ways. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are pervasive, and they have become inextricably linked with contemporary consumer cultures. ICTs represent affordances: to apprise, plan, order, network, socialize, stream, transact and rate. These are remunerated with concessions in the form of consumer data that is used to determine product/service marketability, and to predict and manipulate consumer choices. As a result, ICTs have profoundly changed society, with repercussions for identity formation, social norms, and business structures. Tourism is at the forefront of these developments: as a driver of ICT introductions, an arena for testing & trialing, and a global market. This paper critically examines these developments and its linkages to tourism and sustainability goals, concluding that existing academic assessments are optimistic, simplistic and monocausal, with a focus on business and marketing opportunities. Tourism appears to have developed through four stages of ICT adoption - opportunity, disruption, immersion and usurpation -, which reflect on new opportunities and risks, and the need for more critical evaluations of the implications of the ICT economy.

Introduction

Technology and ICT innovationsFootnote1, specifically the smartphone, have fundamentally altered the basis for economic development and business models, and implied unprecedented changes in human behaviour and social psychology (Cusumano et al., Citation2019; Trottier, Citation2012; Turkle, Citation2011, Citation2015; Zuboff, Citation2019). There is much evidence that social, psychological, economic and environmental outcomes of technology and ICT innovations are profound, interrelated, and complex in their outcomes. Consumers have shifted from the use of technology and ICTs to accomplish tasks towards becoming enmeshed in online lives, with concomitant repercussions for social networking, connectedness and friendship (e.g. Turkle, Citation2011, Citation2015); identity and personality formation (e.g. Belk, Citation2013; Ryan & Xenos, Citation2011); mental form (creativity, attention spans, intellectual capacity; e.g. Carr, Citation2020; Mills, Citation2016); interests, learning, education, and opinion (e.g. Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2010; van Laar et al., Citation2020); and consumer choices, practices, and cultures (e.g. Cochoy et al., Citation2017; Denegri-Knott and Molesworth 2010; Leban et al., Citation2020).

Important characteristics of the ICT economy are its rapid expansion, global reach, and oligopolistic structures funneling vast financial flows towards small owner groups: Founders of platform economy models are counted among the wealthiest individuals in the world (Forbes, Citation2020), a phenomenon trailing its own issues of wealth distribution and inequality (Piketty, Citation2014). Tourism is an integral part of all of these dimensions of the growing ICT economy (Gössling & Hall, Citation2019; Martin, Citation2016; Moazed & Johnson, Citation2016), which at its core continues to represent an industrial economy with physical infrastructures and natural resource dependency, specifically fossil fuels (Lenzen et al., Citation2018).

As this short introduction illustrates, the ways in which technology innovations and ICT influence economic development and society are entangled and convoluted. Tourism is an arena in which these processes become particularly evident, demanding a better understanding of outcomes in regard to the Sustainable Development Goals (UN Citation2020). This paper is intended as a contribution to the debate, as ICT innovations are generally understood as socially enriching and supportive of the SDGs (e.g. Ekholm & Rockström, Citation2019; Sachs et al., Citation2019). As noted by Hughes and Moscardo (Citation2019: 237), “The existing discussion of ICT and tourism has mostly focused on ways in which new technologies can automate or make existing tasks more efficient (doing old things better) or ways that expand and alter existing tasks (doing old things in new ways)”. In other words, the wider implications of technology and ICT innovations have not been sufficiently studied, specifically in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the need to transform economic models (Dorninger et al., Citation2021).

The following discussion is theoretically embedded in critical geography. It devotes considerable space to the framing of the drivers, changes and outcomes of the technology and ICT development, to illustrate its potency in changing society and economy. It then moves on to describe how this has affected tourism and travel, followed by an analysis of ICT as consumer affordances with a less-discussed prerogative of concessions. The last section examines the ICT progression as stages with specific characteristics, before more general conclusions for tourism sustainability are drawn.

Critical scholarship and the SDGs

The discussion in this paper has a starting point in critical geography (Bauder et al., Citation2008). Geography is an interdisciplinary science that is commonly described as the study of systems, specifically interrelationships of physical aspects of the Earth system and human activity including perspectives on society, governance, and economic systems. It is here used as the theoretical lens to study implications of technology and ICT in tourism contexts, also embracing relevant insights from sociology, psychology, politics. As Bauder et al. (Citation2008: 1) emphasize, critical geography is “both an approach to scholarship and a practice of scholarship” with an explicitly normative link to the Frankfurt School and Marcuse’s (Citation1964, quoted in ibid.) description of critical theory as a tool of social analysis to “improve the human condition” or what today may be described as ‘advancing the SDGs’. Critical scholarship thus explicitly connects to practice (Werner et al., Citation2020) and even though geography is primarily concerned with place, it also investigates “the processes that shape the evolution of socio-technical systems” (Murphy, Citation2015: 73).

Some authors in tourism studies have called for “critical” or “transformative” tourism scholarship (Ateljevic et al., Citation2013; Boluk et al., Citation2019; Gretzel et al. Citation2020). “Critical” in this paper is however more than an assessment of progress on the SDGs, a comment on the desirability of social development processes, or a blanket critique of “neoliberalism” and “paradigms”. It is here understood as a framework that allows for reflection on complexities in interconnected economic-social-environmental systems, the consideration of ‘challenge hierarchies’ that make some issues priorities over others, the discussion of roadblocks, as well responsibilities for change. It distinguishes dichotomies of individual and society, consumer and citizen, business and governance. As humanity approaches less desirable socio-environmental states in path-dependent processes and as a result of ‘lock-in’ (Unruh, Citation2000), there is a need to move beyond the sweeping calls “to come to terms with tourism’s negative impacts” (Caton et al., Citation2014: 125), and to rather understand the system dynamics and their structural conditions to advance the SDGs.

For this purpose, the paper moves beyond the discussion of individual SDG goals in favor of a more comprehensive understanding of underlying developments, and with a view to highlight ‘taboos’ and omissions. ‘Taboos’ here refers to key barriers to progress on the SDGs that countries choose to not discuss, including population growth and affluence (Ehrlich and Holdren Citation1971). Both issues are acknowledged widely in the literature (Hubacek et al., Citation2017; Ivanova & Wood, Citation2020; Wynes & Nicholas, Citation2017), specifically in regard to unequal wealth distribution (Piketty 2014), but they are socially and politically ignored and even contradicted. Likewise, mainstream opinion purports that technology & ICT benefit human development (Sachs et al., Citation2019), omitting more problematic implications, such as those related to surveillance and corporate power (Babic et al., Citation2017; Zuboff, Citation2019).

The following sections take the form of discourse analysis, i.e. a discussion of depictions of social reality (Potter, Citation2004). The image of technology and ICT as something inherently beneficial to the human project is socially constructive of a given reality (Gill, Citation2000). This is for instance evident in the creation and widespread adoption of biology nomenclature in the business and management literature. Terminology such as “business ecosystem” (Kandiah & Gossain, Citation1998) is now featuring widely in consultancy documents (e.g. Copenhagen Economics, Citation2020a), or, in the context of tourism studies, recognizable in related terms of “tourism ecosystem” (Gretzel et al., Citation2015), “urban smart tourism ecosystems” (Brandt et al., Citation2017), “managerial ecology” (Hall, Citation2019) or “scapegoat ecology” (Mkono, Hughes and Echentille Citation2020). However, ‘ecology’ describes relations of organisms with other organisms and their physical environment, while the term ‘ecosystem’ refers to the interaction of organisms in a specific physical environment; in both cases on the basis of rules founded in biology, physics and chemistry. In comparison, businesses are embedded in socio-economic organizational structures, and governed by economic and legal rules. The difference should be obvious: an ecosystem does not strive for abstract profit nor will it exist outside laws of energy preservation; it follows causality as set out in the natural sciences. In contrast, socio-economic systems are governed by rules and laws that will change over time, and allow for unequal exchange in time or energy (Dorninger et al., Citation2021). Much of the terminology that is in use in the (tourism) literature is thus socially constructive, possibly to invoke notions of efficiency or economic-environmental alignment.

Given the vast size of the field discussing sustainability and the SDGs, the paper does not attempt to engage in a systematic literature review. Instead, it is focused on the discussion of the implications of technology and ICT innovations for socio-economic-environmental systems in human development terms and more specific tourism contexts. It seeks to embrace complexity and to consider insights from various disciplines, on the premise that it is important to recognize the challenges incurred in the technology and ICT progression: to dismantle contradictions, to discuss ways to overcome fundamental roadblocks, and to devise strategies to increase benefits.

Emergence and outcomes of technology and ICT developments

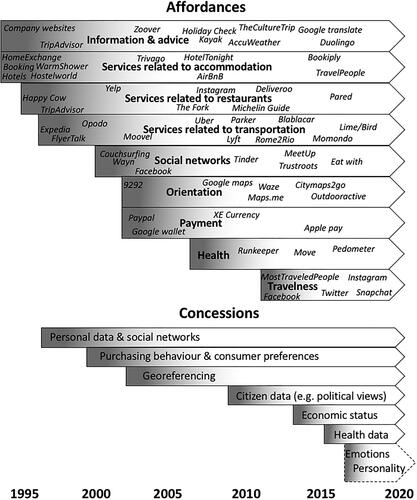

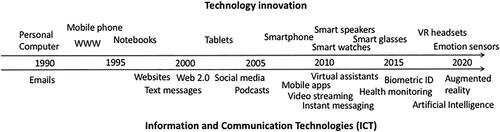

Many of the technology and ICT innovations people take for granted have been introduced rather recently (), bearing evidence of an acceleration in the development of socio-technological systems. The World Wide Web was made available in 1993, a period also characterized by an expansion in personal computer use. Emails increasingly replaced other forms of communication (letters, facsimiles) in the mid 1990s. Nokia introduced the first cellphones with internet capabilities in 1996. Websites caused an early wave of Internet gold fever, but the dot-com bubble was initially short-lived (Goodnight & Green, Citation2010). Yet, by 2000, the Pew Research Center (Citation2000) recorded that some 43% of American Internet users would miss going online “a lot”. At this point in time, the introduction of the Web2.0 allowed users to make the step from being passive observers of online content to become its generators. The Internet turned to participation, and became driven by contributions from individuals and their interactive collaboration (Sutter, Citation2009), vastly increasing the interest in technology and ICT.

Figure 1. Technology innovations and ICT developments, 1990–2020*.

*Time scale positions indicate when technologies/ICTs became widely available to consumers, not when these were invented. The most recent tech & ICT developments have not as yet become relevant for mass-markets.

The most significant hallmark over the past 30 years of technology innovations is arguably the smartphone, introduced by Apple in 2007. The phone made it possible to use applications (apps), of which just 500 were available through the IOS App Store in 2008 – compared to 2,560,000 in 2020 (Google Play Store; BusinessofApps, Citation2020). New ICT services, such as social media, including social networking sites, blogs, review sites, and wikis (Gandomi & Haider, Citation2015), rapidly gained in popularity in subsequent years. A global survey found that consumers spent an average 80 minutes per day accessing the mobile Internet in 2015, and 130 minutes in 2019 (Zenithmedia, Citation2020). Throughout the past decade, tech innovations have been added to the market: smart speakers and smart watches around 2010, data glasses (smart glasses) in 2013. These innovations enabled new applications, ranging from biometric ID to e-governance to wireless payment. Virtual reality (VR) headsets are now in use in various contexts, including gaming and augmented reality applications. In the future, emotion sensors are likely to represent the next step in the technology development chain, again allowing for new ICT innovations. The timeline () illustrates both the recency of many innovations, as well as the growing speed of market integration.

Growing opportunities to use mobile ICT have gone along with very significant changes in consumer behaviour that fundamentally altered business models. Large global tech firms profited most, with estimates that apps were downloaded 115 billion times in 2019 (Google Play and IOS App Stores; BusinessofApps, Citation2020). Platforms increasingly control purchases of goods (Amazon; Alibaba; E-bay), the flow of information (Alphabet including Google), data processing (Microsoft), sociality online (Facebook; Instagram; Weibo; Whatsapp; Tencent; Twitter), trade, sales and logistics (JD; SAP), entertainment streaming (Netflix, YouTube), or financial transactions (PayPal, ApplePay). Market concentration processes are ongoing. For example, Facebook bought Instagram in 2012 and Whatsapp in 2014. Cooperation between the corporate leaders has simultaneously intensified, as evident in the increasing number of sites asking for registration through Facebook or Google accounts. This confirms and reinforces these platforms’ market dominance, as well as their capabilities in verifying identity. As an outcome, there has been a consolidation in terms of the largest players in terms of revenue generation, the structure of financial flows to “centers”, product and service diversity, as well as control of consumer information. This has prompted lawsuits alleging anticompetitive behaviour (Vermont Law School, Citation2020).

Financial flows are perhaps best suited to illustrate the economic outcomes of concentration processes. Babic et al. (Citation2017) show that on the basis of a comparison of state revenue (taxes) and business revenue (turnover), the 100 largest economic entities in the world comprise 71 corporations and 29 countries. In 2016, Walmart’s revenue was larger than Spain’s; Royal Dutch Shell’s larger than Sweden’s. Facebook’s marketing income alone was US$148 billion in 2014 (Deloitte, Citation2015), and hence only slightly smaller than Denmark’s tax revenue in 2016 (Babic et al., Citation2017). While the global economy continues to be dominated by corporations belonging to the oil and automotive industries, tech and ICT corporations have become increasingly important. The largest 20 technology corporations reported a combined revenue of US$2,641 billion in 2019 (FXXSI, Citation2020), exceeding the tax revenue of any nation state save the USA (Babic et al., Citation2017).

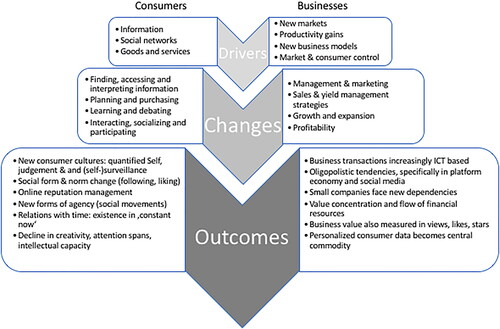

It is obvious that the rapid growth of the ICT economy initiated complex changes that have affected businesses small and large, with repercussions for individuals and society, as well as consumer culture more generally. illustrates this in a generalized model of drivers, changes, and outcomes for consumers and businesses. Drivers of consumer ICT interest include access to information, social networks, and goods and services; businesses profit from new markets, productivity gains, new business models, as well as the control of consumer preferences. Notably, in the ICT economy, means of production loose importance in comparison to the control of transactions. Drivers of change thus always need to be understood as both opportunities and necessities: where ICT turn into standards, business involvement is no longer a choice.

Figure 2. Drivers, changes and outcomes of the technology & ICT innovations.

Source: author, based on Babic et al., Citation2017; Mills, Citation2016; Zuboff, Citation2019

Thus, the widespread adoption of ICT has led to changes in the way consumers find, access, and interpret information; how they plan and purchase; learn and debate; interact and participate. For companies, there have been major shifts in management and marketing; sales and yield management strategies; growth and expansion; as well as implications for profitability. Over the last decade, these changes have had an unprecedented acuity for society and businesses.

Last, outcomes for society and businesses are complex. On the side of the consumer, ICT innovations have generated new consumer cultures, social norms and concomitant needs, such as to manage one’s online reputation. Social media also change perspectives on time, as being “constantly online” (Mills, Citation2016: 4) means living in the present, attenuating the importance of past and future. This has repercussions for the way humans interact, think, and learn; including creativity, attention spans, and overall intellectual capacity (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2010; van Laar et al., Citation2020). Carr (Citation2020: 112) calls online presence a “permanent state of distractedness”, and there is evidence that online culture affects cognitive processes including analytical thinking, memory, performance, social cue interpretation and social competence (Mills, Citation2016). On the side of businesses, a growing share of transactions are managed through ICT. Smaller companies face the new markets’ oligopolistic tendencies and depend on platforms dictating their own rules. Business value is measured in views, likes or stars. Developments have also meant that volunteered and extracted individualized consumer data is the central commodity in the ICT economy.

The complexity of these processes is best illustrated looking into one individual company such as Facebook, though Booking or Airbnb are likely equally revealing in tourism contexts. Launched in 2004, Facebook claimed to support 4.5 million jobs globally in 2014 (Deloitte, Citation2015), and €208 billion in economic activity across 15 EU markets in 2019 (Copenhagen Economics, Citation2020b). Figures such as these support an understanding of Facebook as a job engine, omitting that as a result of the platform’s growth, vast job numbers have also disappeared: Between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, print media started to struggle with the transition to (additional) digital editions, while simultaneously facing revenue losses due to a massive shift of advertisement flowing to Facebook and other platforms (ACCC (Australian Competition & Consumer Commission), Citation2018). As a result, many daily newspapers went bankrupt in the 2000s (Herndon, Citation2012), while journalists were replaced with ‘authors’ (O’Regan & Young, Citation2019). By implication, power over news flows (and hence opinion) shifted, while investigative journalism controlling the dealings of large corporations disappeared (Carson, Citation2014). The information vacuum was filled by Facebook and other online platforms with their new formats including news apps, podcasts, or video streaming and a focus on specific stories (ACCC (Australian Competition & Consumer Commission), Citation2018): “News” became “algorithmically personalized services” (Bodó, Citation2019), with contents increasingly designed to shape opinion, written by people without education in journalism ethics.

The importance of these changes in terms of misleading information has been intensely discussed, because it affects trust in government services and institutions (Einstein & Glick, Citation2015). It undermines the “intellectual well-being” of society and thus the foundations of democracy (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2017: 355). Notably, misleading information is often targeted at specific audiences determined on the basis of algorithms using ‘volunteered’ consumer data (Sinclair 2016). It involves complex sets of techniques such as bots (automated user accounts to manipulate other users or algorithms), spamming (deceptive profiles in social network communities), astroturfing (coordination of large groups of platform users to spread specific content), contagion (spread of content through social media chains), algorithmic bias (spread of specific information that is not balanced in terms of its reporting), and outright fake news (fabricated information) (Treen, Williams & O’Neill, 2020). All of these forms of online misinformation tap into human interest to receive “newsworthy” information, also to create social capital (Phua et al., Citation2017). As confirmed by Vosoughi et al. (Citation2018), false news spread faster than real news. Facebook enables and accelerates misinformation, due to the platform’s global use and outreach and its functioning as an “echo chamber” (Treen et al., Citation2020), in which opinion polarization is based on processes of belief system reinforcement within social media groups with specific identities (Dovidio et al., Citation1998).

ICT media innovations thus undermine social and political form, creating a “post-truth world [that has] emerged as a result of […] growing economic inequality, increased polarization, declining trust in science, and an increasingly fractioned media landscape” (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2017: 353). Put differently, part of the ICT economy feeds on the deteriorating socio-economic-political structures that its business model creates. It is for this reason Zuboff (Citation2019) describes the ICT economy as “surveillance capitalism” that seeks to replace the nation state with “instrumentarianism”. Her observations need to be seen in light of global tendencies for countries to drift towards autocratic regimes (V-Dem Institute, Citation2020), the ICT economy’s tax avoidance strategies (e.g. Los Angeles Times, Citation2016), as well as mechanisms of data collection through (self)-surveillance (Chantre-Astaiza et al., Citation2019; Erevelles et al., Citation2016).

As Carr (Citation2020) notes, just ten years ago the Internet was associated with access to information. Today, the opportunity of access has turned into a necessity to engage, as sociality in Gen Z (and partially in Gen Y) is largely lived and organized through apps and social media. ICT taps into the basic human need to connect, to belong, and to be accepted among peers: it defines ‘meaning’ (Williams, Citation2001) and thus affects identity formation, autonomy, and wider social norms.

Technology, ICT & the SDGs

The preceding discussion raises significant questions regarding the role of the ICT economy in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. In 2015, the UN Sustainable Development Summit in New York adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that have since provided the guideline for global development (UN 2018). The SDGs address poverty and inequality, health and education, gender equality, water and energy, climate, and the environment on land and in the oceans. The UN (Citation2020) acknowledges that very limited progress on the SDGs has been undermined by the COVID-19 crisis. Naidoo and Fisher (Citation2020: 198) suggest that “[…] the very foundations on which the SDGs were built have shifted.” With expectations that climate change will lead to greater food security vulnerabilities, the socio-economic situation in many countries is now characterized by a very real risk of “geopolitical unrest” (ibid.).

In discussing the key challenges, Naidoo and Fisher (Citation2020) start with population growth: “[…] if the world’s population rises, as predicted, to 9.7 billion by 2050, it will exacerbate all other threats to sustainability” (ibid.: 200). Notably, children born in high-income countries contribute to resource consumption at a rate up to several orders of magnitude greater than children born in poorer parts of Africa (Ivanova & Wood, Citation2020). This is particularly relevant in the context of climate change: Wynes and Nicholas (Citation2017) suggest that having one fewer child saves, in developed countries, 58.6 t of CO2-equivalent per year. In comparison, a car-free lifestyle can save 2.4 t CO2-equivalent per year. Population growth is also linked to loss of biological diversity and food production (Crist et al., Citation2017). Yet, politically, population growth continues to be a non-issue (Bongaarts and O’Neill Citation2018), and many high-income countries retain policies to increase birth rates (e.g. Lepperhoff & Correll, Citation2014).

A second major sustainability challenge is affluence (Ehrlich and Holdren Citation1971; Holdren and Ehrlich Citation1974; Saez Citation2017; Wiedmann et al., Citation2020). There is ample evidence that resource consumption increases with wealth (Hubacek et al., Citation2017; Ivanova & Wood, Citation2020). It is equally clear that ecological modernization cannot outweigh growing resource use, requiring behaviour change and limits to consumption (Alcott, Citation2008; Sorrell et al., Citation2020; Spangenberg & Lorek, Citation2019). Yet, the implications of affluence and wealth distribution are not usually discussed in the development literature (see e.g. Sachs et al., Citation2019), other than in terms of the need to increase income levels among the poor. Recent years have seen an acceleration of global inequalities in wealth distribution, with estimates that the world’s 2,153 billionaires possess the same wealth as the 4,600,000,000 least wealthy (Oxfam, Citation2020). In line with these concentration processes, global corporations have become more powerful economically and politically, while seeking to avoid tax payments and to obscure production processes (e.g. Cherry & Sneirson, Citation2012; Contractor, Citation2016). Naidoo and Fisher (Citation2020) also raise the issue of subsidies, as governments support fossil fuel industries with 6.3% of global GDP (in 2015). These processes have relevance for the ICT economy, which is more energy-efficient than other economic sectors in principle (Lange et al., Citation2020), but still consuming large amounts of energy (Hittinger & Jaramillo, Citation2019). There is also a difference in the ‘value’ generated: Agriculture produces food, while the ICT economy may burn fossil fuels to generate cryptocurrencies via algorithm-based ‘mining’ (Gallersdörfer et al., Citation2020).

In light of these reflections, there is a need to reinforce efforts to advance the SDGs (Naidoo & Fisher, Citation2020; UN Citation2020); a discussion in which artificial intelligence and digital technologies often feature as “solutions”. Sachs et al. (Citation2019: 810), for example, underline that “digital technologies can raise productivity, lower production costs, reduce emissions, expand access, reduce resource intensity of production processes, improve matching in markets, enable the use of big data and make public services more readily available”. Even though some risks are mentioned, such as the loss of jobs, tax avoidance, the theft of digital identities, privacy invasion, or data monopolies, there appears to be a very limited understanding of the wider socio-economic-environmental implications of ICT innovations. As Banister and Stead (Citation2004: 628) observed in transport contexts, “every technological innovation has acted to increase demand rather than to reduce it” (Banister & Stead, Citation2004: 628), raising the prospect of potentially contradictory outcomes of ICT innovations.

Technology and ICT in tourism studies

Relationships of technology & ICT with tourism have received much attention since the early days of computerized reservation systems, global distribution systems, and the introduction of the Internet (Inkpen, Citation1998; O’Connor, Citation1999; Tjoa, Citation1997; Werthner & Klein, Citation1999). Digitalization is now the largest field in tourism studies that also has seen the publication of many influential papers, if measured in citation numbers. These discuss marketing and management (Buhalis, Citation2003; Buhalis & Laws, Citation2001; Carter & Bedard, Citation2001; Carter & Richer, Citation1999) wider ICT developments (Buhalis, Citation2003; Buhalis & Law, Citation2008), social media (Leung et al., Citation2013; Xiang & Gretzel, Citation2010) and recommender systems (Ricci et al., Citation2015).

The field has now reached such a degree of maturity that reviews are increasingly commonplace. In a meta-study of reviews, Ukpabi and Karjaluoto (Citation2017) show that there has been a particular interest in ICT applications (Buhalis & Law, Citation2008; Frew, Citation2000; Law et al., Citation2009; Citation2010; Citation2014; Leung & Law, Citation2007); social media (Leung et al., Citation2013; Lu & Stepchenkova, Citation2015; Zeng & Gerritsen, Citation2014); market segmentation based on ICT (Pesonen, Citation2013); and Internet marketing (Leung et al., Citation2015). Ukpabi and Karjaluoto (Citation2017) see these as dimensions of consumer adoption of ICT, either in the form of web-based services, social media, or mobile information systems. In the most recent review, Law et al. (Citation2019) distinguish consumer and supplier perspectives. They conclude that, on the consumer side, most papers discuss purchase decisions, followed by post-purchase behaviour, information searches, technology adoption, alternatives evaluation, and need recognition. On the supplier-side, ICT research is occupied with management, followed by research, product distribution, promotion, and communication.

This suggests that ICT research in tourism is preoccupied with business models or consumer responses. Studies have predominantly had economic perspectives, often with normative starting points. In comparison, critical studies of ICT in environmental, social or governance contexts are relatively rare. They also focus on potential positive contributions: to measure carbon content, to design “intelligent” transport systems, to manage and monitor - from energy to waste to visitors (e.g. Ali & Frew, Citation2014; Buning & Lulla, Citation2021; Gallego & Font, Citation2020; Giglio et al., Citation2019; Scott & Frew, Citation2013; Serrano et al., Citation2020). Budeanu (Citation2013) raised the prospect of an increase in demand in socially and environmentally “better” products and services as a result of online comparison, though concluding that such an interest was not as yet evident on social media. It may be argued that neither has this interest developed over the past seven years. This is also true for social equity, local control, employment quality, or biological diversity preservation, the future ICT-advancing-sustainability propositions heralded by Benckendorff et al. (Citation2014). In recalling the outline of this paper, interrelationships of ICT with sustainability beget complexity, and they can contradict or confound the SDGs (Gössling, Citation2017; Nagle & Vidon, Citation2020).

The dearth of critical assessments of tourism and ICT interrelationships is evident. Yet, such views are needed, as there are consequences for i) businesses, in terms of revenue generation and distribution, market access and concentration, competition, dependency structures, profitability, reputation, value chains and business ethics; ii) destinations in terms of changes in spending, length of stay, timing of holidays, tax evasion, health and safety, control, overtourism phenomena; and iii) consumers in regard to judgement, information search, purchase decision-making, cultural learning, utilization of transport systems, or the performance of mobilities (Gössling & Hall, Citation2019).

Double-edged outcomes can be illustrated for consumers, for whom opportunities associated with technology and ICT innovations represent affordances, defined here with Gibson (Citation1966) as “resources or support”. As shows, affordances have demanded concessions. Affordances include information & advice in the form of websites, travel advice, weather data, or translation services. There is also support for finding accommodation, including rental, reciprocal or free stays, as well as services related to food, such as special-interest gastronomy (vegan, distinguished), food communication, or deliveries. Services related to transportation include information, reservations, planning and routing, or rentals/sharing (cars, bicycles, e-scooters). Social networks refers to sociality through co-presence, social capital generation, or new relations (Germann Molz, 2006, Citation2012; Gössling & Stavrinidi, Citation2016).

Orientation comprises tools to navigate unfamiliar environments, including the outdoors. Payment is of central relevance for any traveler and reduces risks (carrying cash), including payment functions and blockchain currencies (Tham & Sigala, Citation2020). Health refers to options to monitor or improve one’s fitness (pulse, steps walked, kilometers cycled, calories “burnt”). Finally, travelness (Urry, Citation2012) is an important emerging use of ICT related to self-representation needs (Marwick, Citation2015; Ok Lyu, Citation2016) and affecting identity formation (Gössling & Stavrinidi, Citation2016). Social media has great relevance in this context because of its roles in upward comparison; this is, tendencies to compare one’s own situation with better-off others (Matley, Citation2018; Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). Comparison may involve staged and manipulated situations, depicted in edited and modified photographs (Marwick, Citation2015), again underlining the complexity of ICT uses and outcomes.

ICT affordances are usually taken for granted by customers, though there are concessions of personal data. suggests that these concessions have become more comprehensive over time, beginning with general consumer (citizen) interests and social network structures (Grimmelmann, Citation2008), and subsequently tracking purchasing behaviour and consumer preferences (Erevelles et al., Citation2016), as well as locational data (Humphreys, Citation2017). It may be argued that citizen data then gained importance (see Cambridge Analytica scandal; Venturini & Rogers, Citation2019), along with economic status data to derive credit ratings and consumer profiles (Hurley & Adebayo, Citation2017). More recently, the introduction of smart watches initiated real-time health data collection, linked to remote monitoring, and with options to make this data available to the health system (King & Sarrafzadeh 2018). In the near future, focus will be on emotions, including opportunities to distinguish individuals on the basis of their personality types (Matsuda et al., Citation2018; Xing et al., Citation2019). An important caveat is that while some jurisdictions have implemented barriers to limit opportunities for private data collection (EC Citation2020), the reality is that individuals are incapable to consider all privacy policies (McDonald & Cranor, Citation2008), and even unlikely to see the need to protect their privacy (Acquisti et al., Citation2015).

There is much evidence that these processes are driven by large corporations to gain consumer control, with complex outcomes for society. AirBnB, for example, introduced mutual reviews, encouraging guests to rate hosts and hosts to rate guests, in a form of reciprocal surveillance (cf. Celata et al., Citation2017; Newell, Citation2014). This effectively expands surveillance structures (Lyon et al., Citation2012) and introduces the need for online reputation management. Notably, the private sector has opportunities for data collection that are equal to those of government, though with fewer restrictions (Marx, Citation2012). This discussion will gain importance with the emergence of AI and the potential for ICTs to determine identity and personality, questioning the autonomy of an increasingly expandable, replaceable, manipulable, and exploitable global consumer class doubling as workforce.

ICT & SDGs: from divergence to support

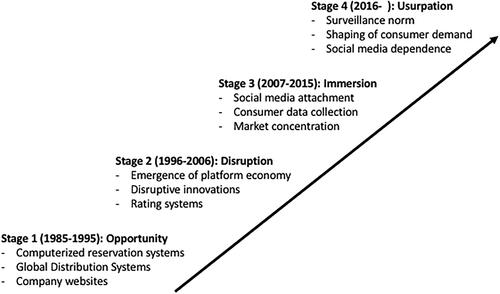

The ICT economy imposes systemic risks on society that also undermine sustainability goals, such as those related to equality, autonomy, transparency, and democracy. It also creates new challenges for individuals in terms of competition, learning, or socializing. These downsides of the ICT economy are not usually discussed; yet they have specific relevance in light of the progression that is observable. In tourism, developments may be conceptualized as four distinct stages. Each of these stages covers about one decade, described here as opportunity, disruption, immersion and usurpation. Stage 1, Opportunity (roughly 1985-1995), is characterized by major advances in connectivity and coordination (). For example, computerized reservation systems made bookings seamless, and allowed for reservations to be made in real-time. Global distribution systems increased outreach, facilitating in particular air transport. Company websites combined tourist information interests with opportunities for self-representation and marketing. In this early stage of the technology and ICT revolution, structural change implied benefits in terms of efficiency and user-friendliness, with a low level of complexity involved in transactions.

Stage 2, Disruption (1996–2006), sees the emergence of the platform economy. Quasi-monopolies are established, as global platforms become intermediaries in reservation transactions. Disruptive innovations (Booking, the low cost carriers) increase the speed and ease of reservations, introduce direct competition on price, while adding capacity and increasing overall demand. The introduction of rating systems trails its own issues of reputation management, trust, and wider consumer norm changes, with concomitant repercussions for businesses and consumers.

Stage 3, Immersion (2007-2015), describes the wider absorption of ICT in the daily lives of consumers as a result of widespread smartphone adoption, and patterns of immersion in social media use. Disruptive innovations (e.g. AirBnB) continue to affect market propositions and to upset established business models. The collection of ‘volunteered’ consumer data becomes systemic, and makes it possible to predict and shape demand. Markets become increasingly concentrated as established platforms increase their outreach, and start to become interconnected and integrated.

Finally, stage 4, Usurpation (2016-2020, ongoing), may be understood as the expansion of power and control mechanisms by a limited number of dominating platforms on a global scale, with a focus on the individualized consumer. With access to data defining consumers - also in their role as citizens -, platforms gather information encompassing social and professional networks, economic ratings, health, views, and personality. Surveillance has turned into a norm, and can be mutual, as in the case of Airbnb hosts and guests. The ultimate corporate goal is to shape consumer demand in real time, as well as to influence the preferences of citizens in social-media engineered democracies. This coincides with the growing dependence of individuals on ICT for participation in social and professional life.

There is some evidence that the next stage in this development will see a major role for robotics, cryptocurrencies, and artificial intelligence (Law et al., Citation2018). Provisionally, it may be called a stage of Assertion, the cementing of control and power structures, through ICT. This fifth stage is likely to simultaneously undermine governmental and institutional control, as exemplified by the expansion of cryptocurrencies. It will also further question sustainable development goals in that the ICT economy seeks to extract economic value and to control the economically valuable population. By implication, the interest in “redundant” people will be limited. As the ICT economy is guided by an economic imperative, environmental and social goals will only be considered where consumers demand this.

Toward the end of 2020, the ICT expansion consequently predicts structures that represent growing risks for society. It will be difficult to correct these developments, as ICT powerfully connect to social needs that they reinforce and echo. Social media streamline desires, reinforce fears, and they demand specific preferences while ruling out others: travel platforms, for example, are as much about applauding movement as they are about condemning stasis. Individual entanglement with the ICT economy and the building of digital identities dependent on social media thus represent major barriers to more critical views of the implications of technology and ICT developments.

Findings such as these can also be discussed in relation to popular views that the ICT economy will make key contributions to the SDGs (e.g. Sachs et al., Citation2019). While such notions refer to the potential of resource efficiency gains, it also remains questionable whether such gains, if they materialize, will not be dwarfed by the overall growth of the economy. This would be specifically true for the tourism economy and its resource use dynamic (Lenzen et al., Citation2018). There is thus a need to critically examine technology and ICT outcomes, bearing in mind complexities, causalities, and hierarchies, such as the double-challenge of population and affluence growth. Currently, the evidence is that the ICT economy contributes to accelerating resource use, the channeling of transaction benefits to the already wealthy, and further deterioration of social development goals.

This critical discussion of the ICT economy reveals a need for regulation. This, however, will be difficult, as the ICT economy dissolves boundaries between consumer and citizen, corporation and state. Even though some proposals exist (e.g. Leal et al., Citation2020), there can be little doubt that bolder action is necessary. Even though hopes have been expressed that technology and ICT will make major contributions to advancing the SDGs, it appears that ICT tools are currently used to investigate and understand the very problems the ICT economy created in the first place (e.g. Celata & Romano, Citation2020; Peeters et al. Citation2018). Even forward-looking discussions of ICT (Fennell, Citation2020; Han et al., Citation2018; McGrath et al., Citation2020) do not suggest transformative outcomes. This confirms a risk that ongoing discussions of ICT benefits are socially constructive in the sense that they support a narrative of technology and ICT as inherently beneficial, in spite of much evidence to the contrary.

Conclusion

This paper observes that technology and ICT innovations are widely understood as making positive contributions to human development. This overlooks surveillance structures and quasi-monopolies in the ICT economy that blur lines between government and corporation, consumer and citizen. The ICT economy transforms global economies, society and individuals. While many of the affordances of the ICT economy are welcomed by consumers, there is a social cost in terms of equality, autonomy, transparency, and democracy. The ICT economy in its current form does not make the world fairer or more resilient, and it is not respectful of environmental limits.

Some important interrelationships have been discussed in the context of tourism, examined in terms of a juxtaposition of affordances and concessions. Technology and ICT are attractive because of the wide range of opportunities they offer to navigate tourist life. Yet, affordances demand concessions in the form of personal data. Individuals are increasingly tracked and profiled with the purpose of revenue generation. Tourism is a specifically relevant arena for these developments, as the platform economy is a prominent driver of developments in the sector, and because of the many applications with relevance for travelers.

If technologies and ICTs are to make positive contributions to sustainable development, these insights need to be addressed. This is primarily a structural problem, in which the dominance of individual platforms, their influence, and the evident lack of regulation have created barriers to transform the sector. There clearly is an opportunity for ICT to make substantial sustainability contributions, but to harness this potential will require awareness of risks and complexities, also in regard to consumption and production norms, citizenship and governance. Critical scholarship will continue to have an important role in empowering transformations, though this will require the field to acknowledge that it has to far been largely uncritical, supportive and hence socially constructive of developments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The terminology used in this paper distinguishes technologies and Information and Communication technologies (ICTs). Technologies are defined as hardware (from smartphones to smart glasses), while ICTs describes the software (websites, applications, social media, artificial intelligence) used by technology.

References

- Buhalis, D & Laws, E. (eds). (2001). Tourism Distribution Channels-Practices, Issues and Transformations., Continuum Publishing.

- (2013). Ateljevic, I., Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (Eds.). The critical turn in tourism studies: Creating an academy of hope. Routledge.

- ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) (2018). Issues Paper: Digital Platforms Inquiry. Canberra, ACT, Australia: ACCC.

- Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science (New York, N.Y.).), 347(6221), 509–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1465

- Alcott, B. (2008). The sufficiency strategy: Would rich-world frugality lower environmental impact? Ecological Economics, 64(4), 770–786. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.04.015

- Ali, A., & Frew, A. J. (2014). ICT and sustainable tourism development: An innovative perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 5(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-12-2012-0034

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Babic, M., Fichtner, J., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2017). States versus corporations: Rethinking the power of business in international politics. The International Spectator, 52(4), 20–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1389151

- Banister, D., & Stead, D. (2004). Impact of information and communications technology on transport. Transport Reviews, 24 (5), 611–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0144164042000206060

- Bauder, H., Engel, D., & Mauro, S. (2008). Critical geographies: a collection of readings. Praxis e-Press.

- Belk, R. W. (2013). Extended self in a digital world. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(3), 477–500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/671052

- Benckendorff, P. J., Sheldon, P. J., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2014). Tourism information technology. CABI.

- Bodó, B. (2019). Selling news to audiences–a qualitative inquiry into the emerging logics of algorithmic news personalization in. Digital Journalism, 7(8), 1054–1075. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1624185

- Boluk, K. A., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism.

- Bongaarts, J., & O'Neill, B. C. (2018). Global warming policy: Is population left out in the cold? Science (New York, N.Y.), 361(6403), 650–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8680

- Brandt, T., Bendler, J., & Neumann, D. (2017). Social media analytics and value creation in urban smart tourism ecosystems. Information & Management, 54(6), 703–713.

- Budeanu, A. (2013). Sustainability and tourism social media. In A.M. Munar, S. Gyimóthy, & C. Liping (Eds.), Tourism social media: Transformations in identity, community and culture. (pp. 87–103). Emerald.

- Buhalis, D. (2003). e tourism –Information Technology for strategic tourism management. Prentice Hall.

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

- Buning, R. J., & Lulla, V. (2021). Visitor bikeshare usage: tracking visitor spatiotemporal behavior using big data. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(4), 711–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1825456

- BusinessofApps (2020). App download and usage statistics. Available: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/app-statistics/ Accessed 13 October 2020.

- Carr, N. (2020). The shallows: What the Internet is doing to our brains. WW Norton & Company.

- Carson, A. (2014). The political economy of the print media and the decline of corporate investigative journalism in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 726–742. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.963025

- Carter, R., & Bedard, F. (2001). E-Business for Tourism-Practical Guidelines for Tourism Destinations and Business., WTO Business Council.

- Carter, R., & Richer, P. (1999). Marketing Tourism Destination Online., WTO Business Council.

- Caton, K., Schott, C., & Daniele, R. (2014). Tourism’s imperative for global citizenship. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 14, 123–128.

- Celata, F., Hendrickson, C. Y., & Sanna, V. S. (2017). The sharing economy as community marketplace? Trust, reciprocity and belonging in peer-to-peer accommodation platforms. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(2), 349–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsw044

- Celata, F., & Romano, A. (2020). Overtourism and online short-term rental platforms in Italian cities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1788568

- Chantre-Astaiza, A., Fuentes-Moraleda, L., Muñoz-Mazón, A., & Ramirez-Gonzalez, G. (2019). Science mapping of tourist mobility 1980–2019. Technological advancements in the collection of the data for tourist traceability. Sustainability, 11(17), 4738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174738

- Cherry, M. A., & Sneirson, J. F. (2012). Chevron, Greenwashing, and the Myth of'Green Oil Companies. Journal of Energy, Climate, and the Environment, 3, 133–153.

- Cochoy, F., Hagberg, J., Petersson McIntyre, M., & Sörum, N. (Eds) (2017). Digitalizing Consumptions. How devices shape consumer culture. Routledge.

- Contractor, F. J. (2016). Tax avoidance by multinational companies: Methods, policies, and ethics. Rutgers Business Review, 1(1), 27–43.

- Copenhagen Economics (2020a). Empowering the European Business Ecosystem. Available: https://www.copenhageneconomics.com/publications/publication/empowering-the-european-business-ecosystem Accessed 14 October 2020.

- Copenhagen Economics (2020b). The Facebook Company. Empowering the European Business Ecosystem. Available: https://www.copenhageneconomics.com/publications/publication/empowering-the-european-business-ecosystem Accessed 17 November 2020.

- Crist, E., Mora, C., & Engelman, R. (2017). The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection. Science (New York, N.Y.), 356(6335), 260–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal2011

- Cusumano, M. A., Gawer, A., & Yoffie, D. B. (2019). The business of platforms: Strategy in the age of digital competition, innovation, and power. HarperCollins.

- Deloitte (2015). Facebook’s global economic impact. Available: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-uk-global-economic-impact-of-facebook.pdf Accessed 14 October 2020.

- Denegri‐Knott, J., & Molesworth, M. (2010). Concepts and practices of digital virtual consumption. Consumption Markets & Culture , 13(2), 109–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10253860903562130

- Dorninger, C., Hornborg, A., Abson, D. J., von Wehrden, H., Schaffartzik, A., Giljum, S., Engler, J.-O., Feller, R. L., Hubacek, K., & Wieland, H. (2021). Global patterns of ecologically unequal exchange: implications for sustainability in the 21st century. Ecological Economics, 179, 106824. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106824

- Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Validzic, A. (1998). Intergroup bias: status, differentiation, and a common in-group identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.109

- EC (2020). EU data protection rules. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/eu-data-protection-rules_en Accessed 19 November 2020.

- Einstein, K. L., & Glick, D. M. (2015). Do I think BLS data are BS? The consequences of conspiracy theories. Political Behavior, 37(3), 679–701. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9287-z

- Ekholm, B., Rockström, J. (2019). Digital technology can cut global emissions by 15%. Here’s how. Available: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/why-digitalization-is-the-key-to-exponential-climate-action/ Accessed 7 November 2020.

- Ehrlich, P. R. & Holdren, J. (1971). Impact of Population Growth, Science, 171, 1212–1217.

- Erevelles, S., Fukawa, N., & Swayne, L. (2016). Big Data consumer analytics and the transformation of marketing. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 897–904. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.07.001

- Fennell, D. A. (2020). Technology and the sustainable tourist in the new age of disruption. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1769639

- Forbes (2020). The richest people in the world. Available: https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/#1cd64db251c7 Accessed 12 March 2020.

- Frew, A. J. (2000). Information and communications technology research in the travel and tourism domain: perspective and direction. Journal of Travel Research, 39(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900203

- FXXSI (2020). Top 10 world’s most valuable technology companies in 2020. Available: https://fxssi.com/most-valuable-tech-companies Accessed 15 October 2020.

- Gallego, I., & Font, X. (2020). Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: using Big Data to inform tourism policy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1773476

- Gallersdörfer, U., Klaaßen, L., & Stoll, C. (2020). Energy consumption of cryptocurrencies beyond bitcoin. Joule, 4(9), 1843–1846. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2020.07.013

- Gandomi, A., & Haider, M. (2015). Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. International Journal of Information Management, 35(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.10.007

- Germann Molz, J. (2006). Watch us wander': mobile surveillance and the surveillance of mobility. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38(2), 377–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a37275

- Germann Molz, J. G. (2012). Travel connections: Tourism, technology and togetherness in a mobile world. Routledge.

- Gibson, J. J. (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Houghton Mifflin.

- Giglio, S., Bertacchini, F., Bilotta, E., & Pantano, P. (2019). Using social media to identify tourism attractiveness in six Italian cities. Tourism Management, 72, 306–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.12.007

- Gill, R. (2000). Discourse Analysis. In Atkinson, P., Bauer, M.W. & Gaskell, G. (Eds), Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound (pp. 172–190). Sage.

- Goodnight, G. T., & Green, S. (2010). Rhetoric, risk, and markets: The dot-com bubble. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 96(2), 115–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00335631003796669

- Gössling, S. (2017). Tourism, information technologies and sustainability: an exploratory review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 1024–1041. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1122017

- Gössling, S., & Hall, C. M. (2019). Sharing versus collaborative economy: how to align ICT developments and the SDGs in tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(1), 74–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560455

- Gössling, S., & Stavrinidi, I. (2016). Social networking, mobilities, and the rise of liquid identities. Mobilities, 11(5), 723–743. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2015.1034453

- Gretzel, U., Werthner, H., Koo, C., & Lamsfus, C. (2015). Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 558–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.043

- Grimmelmann, J. (2008). Saving Facebook. Iowa Law Review, 94, 1137–1206.

- Gretzel, U., Fuchs, M., Baggio, R., Hoepken, W., Law, R., Neidhardt, J., Pesonen, J., Zanker, M. & Xiang, Z. (2020). e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: a call for transformative research. Information Technology & Tourism, 22, 187–203, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00181-3

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Han, W., McCabe, S., Wang, Y., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2018). Evaluating user-generated content in social media: an effective approach to encourage greater pro-environmental behavior in tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 600–614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1372442

- Herndon, K. (2012). The decline of the daily newspaper: How an American institution lost the online revolution. Peter Lang.

- Hittinger, E., & Jaramillo, P. (2019). Internet of Things: Energy boon or bane? Science (New York, N.Y.).), 364(6438), 326–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau8825

- Holdren, J. P., & Ehrlich, P. R. (1974). Human population and the global environment: population growth, rising per capita material consumption, and disruptive technologies have made civilization a global ecological force. American Scientist, 62(3), 282–292.

- Hubacek, K., Baiocchi, G., Feng, K., Castillo, R. M., Sun, L., & Xue, J. (2017). Global carbon inequality. Energy, Ecology and Environment, 2(6), 361–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-017-0072-9

- Hughes, K., & Moscardo, G. (2019). ICT and the future of tourist management. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(3), 228–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2018-0072

- Humphreys, L. (2017). Locating Locational Data in Mobile and Social Media. In Zimmer, M. and Kinder-Kurlanda, K. (Eds) Internet Research Ethics for the Social Age (pp. 245–254). Peter Lang.

- Hurley, M., & Adebayo, J. (2017). Credit scoring in the era of big data. Yale Journal of Law and Technology, 18(1), 148–216.

- Inkpen, G. (1998). Information Technology for Travel and Tourism., Addison Wesley Logman.

- Ivanova, D., & Wood, R. (2020). The unequal distribution of household carbon footprints in Europe and its link to sustainability. Global Sustainability, 3 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.12

- Kandiah, G., & Gossain, S. (1998). Reinventing value: The new business ecosystem. Strategy & Leadership, 26(5), 28–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/eb054622

- King, C. E., & Sarrafzadeh, M. (2018). A survey of smartwatches in remote health monitoring. Journal of Healthcare Informatics Research, 2(1–2), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-017-0012-7

- Lange, S., Pohl, J., & Santarius, T. (2020). Digitalization and energy consumption. Does ICT reduce energy demand? Ecological Economics, 176, 106760. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106760

- Law, R., Buhalis, D., & Cobanoglu, C. (2014). Progress on information and communication technologies in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(5), 727–750. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2013-0367

- Law, R., Chan, I. C. C., & Wang, L. (2018). A comprehensive review of mobile technology use in hospitality and tourism. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 27(6), 626–648.

- Law, R., Leung, R., & Buhalis, D. (2009). Information technology application in hospitality and tourism: a review of publication from 2005-2007. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 26(5-6), 599–623. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400903163160

- Law, R., Leung, D., & Chan, I. C. C. (2019). Progression and development of information and communication technology research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(2), 511–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2018-0586

- Law, R., Qi, S., & Buhalis, D. (2010). Progress in tourism management: A review of website evaluation in tourism research. Tourism Management, 31(3), 297–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.11.007

- Leal, F., Malheiro, B., Veloso, B., & Burguillo, J. C. (2020). Responsible processing of crowdsourced tourism data. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1778011

- Leban, M., Seo, Y., & Voyer, B. G. (2020). Transformational effects of social media lurking practices on luxury consumption. Journal of Business Research, 116, 514–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.010

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

- Lepperhoff, J., & Correll, L. (2014). Children in Family Policy Discourses in Germany: from invisible family members to society's great hope. Global Studies of Childhood, 4(3), 143–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2014.4.3.143

- Leung, X. Y., Xue, L., & Bai, B. (2015). Internet marketing research in hospitality and tourism: a review and journal preferences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(7), 1556–1572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2014-0268

- Leung, R., & Law, R. (2007). Information technology publications in leading tourism journals: A study of 1985 to 2004. Information Technology & Tourism, 9(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3727/109830507781367357

- Leung, D., Law, R., Van Hoof, H., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 3–22.

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

- Lewis, S., Pea, R., & Rosen, J. (2010). Beyond participation to co-creation of meaning: mobile social media in generative learning communities. Social Science Information, 49(3), 351–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018410370726

- Los Angeles Times (2016). One of Facebook’s biggest accomplishments: Paying far lower taxes. Available: https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-tn-facebook-taxes-20160714-snap-story.html Accessed 18 October 2020.

- Lu, W., & Stepchenkova, S. (2015). User-generated content as a research mode in tourism and hospitality applications: Topics, methods, and software. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 24(2), 119–154.

- Lyon, D., Haggerty, K. D., & Ball, K. (2012). Introducing surveillance studies. In: Ball, K., Haggerty, K. D., and Lyon, D. (Eds) Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

- Marcuse, H. (1964). One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Beacon Press.

- Martin, C. J. (2016). The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecological Economics, 121, 149–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027

- Marwick, A. E. (2015). Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public Culture, 27(1 75), 137–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2798379

- Marx, G. T. (2012). Preface. In: Ball, K., Haggerty, K.D., and Lyon, D. (Eds) Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies (pp. xx–xxxi). Routledge.

- Matley, D. (2018). This is NOT a #humblebrag, this is just a #brag”: The pragmatics of selfpraise, hashtags and politeness in Instagram posts. Discourse. Context & Media, 22, 30–38.

- Matsuda, Y., Fedotov, D., Takahashi, Y., Arakawa, Y., Yasumoto, K., & Minker, W. (2018). Emotour: Estimating emotion and satisfaction of users based on behavioral cues and audiovisual data. Sensors, 18(11), 3978. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/s18113978

- McDonald, A. M., & Cranor, L. F. (2008). The cost of reading privacy policies. I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, 4, 543.

- McGrath, G. M., Lockstone-Binney, L., Ong, F., Wilson-Evered, E., Blaer, M., & Whitelaw, P. (2020). Teaching sustainability in tourism education: a teaching simulation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1791892

- Mills, K. L. (2016). Possible effects of internet use on cognitive development in adolescence. Media and Communication, 4(3), 4–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.516

- Mkono, M., Hughes, K., & Echentille, S. (2020). Hero or villain? Responses to Greta Thunberg's activism and the implications for travel and tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2081–2098.

- Moazed, A., & Johnson, N. L. (2016). Modern monopolies: what it takes to dominate the 21st century economy. St. Martin's Press.

- Murphy, J. T. (2015). Human geography and socio-technical transition studies: Promising intersections. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 17, 73–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.03.002

- Nagle, D. S., & Vidon, E. S. (2020). Purchasing protection: outdoor companies and the authentication of technology use in nature-based tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1828432

- Naidoo, R., & Fisher, B. (2020). Reset sustainable development goals for a pandemic world. Nature, 583(7815), 198–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01999-x

- Newell, B. C. (2014). Crossing lenses: policing's new visibility and the role of smartphone journalism as a form of freedom-preserving reciprocal surveillance. University of Illinois Journal of Law, Technology and Policy, 59–104.

- O’Connor, P. (1999). Electronic Information Distribution in Tourism and Hospitality. CABI Publishing.

- O’Regan, T., & Young, C. (2019). Journalism by numbers: trajectories of growth and decline of journalists in the Australian census 1961–2016. Media International Australia, 172(1), 13–32.

- Ok Lyu, S. (2016). Travel selfies on social media as objectified self-presentation. Tourism Management, 54, 185–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.001

- Oxfam (2020). Time to care. Available: https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/time-care Accessed 6 November 2020.

- Pesonen, A. J. (2013). Information and communications technology and market segmentation in tourism: a review. Tourism Review, 68(2), 14–30.

- Pew Research Center (2000). Tracking Online Life. Available: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2000/05/10/tracking-online-life/ Accessed 20 November 2020.

- Peeters, P., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C., Eijgelaar, E., Hartman, S., Heslinga, J., Isaac, R., Mitas, O., Moretti, S., Nawijn, J., Papp, B., and Postma, A. (2018). Research for TRAN Committee – Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses. Available: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/629184/IPOL_STU(2018)629184_EN.pdf Accessed 10 October 2020.

- Phua, J., Jin, S. V., & Kim, J. J. (2017). Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital: A comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 115–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.041

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st Century. Havard University Press.

- Potter, J. (2004). Discourse Analysis. In: Hardy, M. and Bryman, A. (Eds), Handbook of Data Analysis (pp. 607–624). Sage.

- Ricci, F., Rokach, L., & Shapira, B. (2015). Recommender systems handbook. Springer.

- Ryan, T., & Xenos, S. (2011). Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1658–1664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.004

- Sachs, J. D., Schmidt-Traub, G., Mazzucato, M., Messner, D., Nakicenovic, N., & Rockström, J. (2019). Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nature Sustainability, 2(9), 805–814. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0352-9

- Saez, E. (2017). Income and wealth inequality: Evidence and policy implications. Contemporary Economic Policy, 35(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12210

- Scott, M. M., & Frew, A. J. (2013). Exploring the role of in-trip applications for sustainable tourism: Expert perspectives. In Gretzel, U., Law, R. & Fuchs, M. (Eds), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism (pp. 36–46). Springer.

- Serrano, L., Ariza-Montes, A., Nader, M., Sianes, A., & Law, R. (2020). Exploring preferences and sustainable attitudes of Airbnb green users in the review comments and ratings: a text mining approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1838529

- Sorrell, S., Gatersleben, B., & Druckman, A. (2020). The limits of energy sufficiency: A review of the evidence for rebound effects and negative spillovers from behavioural change. Energy Research & Social Science, 64, 101439.

- Spangenberg, J. H., & Lorek, S. (2019). Sufficiency and consumer behaviour: From theory to policy. Energy Policy, 129, 1070–1079. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.03.013

- Sutter, J. (2009). Tutorial: Introduction to web 2.0. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 25(1), 40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.02540

- Taylor, D. G., & Strutton, D. (2016). Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 10(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-01-2015-0009

- Tham, A., & Sigala, M. (2020). Road block (chain): bit (coin) s for tourism sustainable development goals? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 11(2), 203–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-05-2019-0069

- Tjoa, A. M. (ed.) (1997). Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism. Springer.

- Treen, K. M. D. I., Williams, H. T., & O'Neill, S. J. (2020). Online misinformation about climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 11(5), e665.

- Trottier, D. (2012). Social media as surveillance: Rethinking visibility in a converging world. Ashgate Publishing.

- Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Basic Books.

- Turkle, S. (2015). Reclaiming conversation: The power of talk in a digital age. Penguin Random House.

- Ukpabi, D., & Karjaluoto, H. (2017). Consumers’ acceptance of information and communications technology in tourism: A review. Telematics and Informatics, 34 (5), 618–644. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.12.002

- UN (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.pdf Accessed 2 November 2020.

- Unruh, G. C. (2000). Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy, 28(12), 817–830. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00070-7

- Urry, J. (2012). Social networks, mobile lives and social inequalities. Journal of Transport Geography, 21, 24–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.10.003

- van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J., van Dijk, J. A., & de Haan, J. (2020). Determinants of 21st-century skills and 21st-century digital skills for workers: A systematic literature review. SAGE Open, 10(1), 215824401990017. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900176

- V-Dem Institute (2020). Democracy Report 2020. Available: https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/de/39/de39af54-0bc5-4421-89ae-fb20dcc53dba/democracy_report.pdf Accessed 2 November 2020.

- Venturini, T., & Rogers, R. (2019). API-Based Research” or How can Digital Sociology and Journalism Studies Learn from the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica Data Breach. Digital Journalism, 7(4), 532–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1591927

- Vermont Law School (2020). Class-action lawsuit against Facebook alleges anticompetitive behavior. Available: https://www.jurist.org/news/2020/12/class-action-lawsuit-against-facebook-alleges-anticompetitive-behavior/ Accessed 22 December 2020.

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science (New York, N.Y.), 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

- Werner, M., Asher, K., Barraclough, L., Featherstone, D., Loftus, A., Ouma, S., Theodore, N., & Kent, A. (2020). Radical geography for a resurgent left. Antipode, 52, 3–11.

- Werthner, H., & Klein, S. (1999). Information Technology and Tourism - A Challenging Relationship. Springer.

- Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., Keyßer, L. T., & Steinberger, J. K. (2020). Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y

- Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. Guildford Publications.

- Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters, 12(7), 074024. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541

- Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

- Xing, B., Zhang, H., Zhang, K., Zhang, L., Wu, X., Shi, X., Yu, S., & Zhang, S. (2019). Exploiting EEG signals and audiovisual feature fusion for video emotion recognition. IEEE Access., 7, 59844–59861. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2914872

- Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001

- Zenithmedia (2020). Consumers will spend 800 hours using mobile internet devices this year. Available: https://www.zenithmedia.com/consumers-will-spend-800-hours-using-mobile-internet-devices-this-year/ Accessed 11 March 2020.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.