Abstract

Te Awa Tupua is an ancestor of the Māori people of Whanganui, and is also the Whanganui River, who in 2017 was formally recognised as a person. While legally conferring personhood upon an element of nature is relatively novel, it recognises a fundamental principle of indigeneity, that all things—human and nonhuman—are related. We explore intersections of peace, justice, and sustainability through Indigenous tourism in case studies of three Māori tourism enterprises on Te Awa Tupua (the Whanganui River). Our paper spotlights three findings. First, that treaty settlements elevate the status of Māori knowledge and contain elements of peace-making and economy-making as decolonising projects of self-determined development. Second, while indigeneity is foundational, we found that syncretism is evident in the sustainability of Māori tourism enterprises. Third, we uncovered a socioecological dissonance in attitudes towards commercial growth, with Māori tourism enterprises opting for slower and lower growth in favour of environmental and community wellbeing. We propose a model of Indigenous tourism called kaupapa tāpoi. We conclude by suggesting that reconciling differences in viewpoints on sustainability and growth between Māori and non-Māori tourism enterprises will require involvement of several institutional actors, starting with Te Awa Tupua.

Introduction

Tourism has some lofty ambitions: beyond being simply an enterprising activity, tourism strives to promote peace, justice, and sustainability (D'Amore, Citation1988; Hall, Citation2019; Higgins-Desbiolles & Whyte, Citation2013; Raymond & Hall, Citation2008). In relation to Indigenous peoples, we can add that tourism aims to contribute to Indigenous self-determination and development (Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, et al., Citation2018; Bunten & Graburn, Citation2018; Whitford & Ruhanen, Citation2016; Zapalska & Brozik, Citation2017). Expectations for peace, justice, and sustainability manifest as social, moral, legal, and institutional ethical codes because of universal intolerance for their opposites: war, injustice, inequity, unsustainability, and subjugation (Dutta & Elers, Citation2020; Pereiro, Citation2016; Verbos et al., Citation2017b). Thus, tourism may be viewed as a catalyst for harmony within humanity and with nature (D'Amore, Citation1988). The prospect of harmony through tourism seems vital in post-conflict situations. In the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, although the colonial government’s conflict with Māori—the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand—may have subsided over 140 years ago, its postcolonial effects remain. Persistent socioeconomic disparities, the formation of a tribunal to enquire into historical injustices, and the reaffirmation of Māori knowledge across multiple domains allude to intersections of peace, justice, and sustainability within te ao Māori (Māori society) intended to create dialogic space for epistemological and ontological equity (Cole, Citation2017; Harris & Wasilewski, Citation2004; Smith, Citation1999).

The research question this paper addresses is how do peace, justice, and sustainability intersect in Indigenous tourism in Aotearoa New Zealand? This paper seeks to understand whether and how peace, justice, and sustainability feature within Indigenous tourism by exploring the experiences of three Māori tourism enterprises on the Whanganui River. We focus on the Whanganui River because it offers important insights into the indigeneity of Māori tourism in the context of a treaty settlement between Māori and the Crown pertaining to the river (Awatere et al., Citation2017; Mika et al., Citation2018; Reid et al., Citation2019). We proceed by contextualising the research within the structure of Māori tourism, before discussing tourism in relation to the Whanganui River. Second, we define four key concepts—peace, justice, sustainability, and indigeneity—which function as the theoretical framework for the analysis of Indigenous tourism. Third, we outline the methodology we employed for the research. Fourth, we present the findings as case studies of three Māori tourism enterprises on the Whanganui River. Fifth, we discuss findings on peace, justice, and sustainability in Indigenous tourism and propose a model of Indigenous tourism. We conclude by identifying principles that emerge and their implications for tourism research, policy, and practice.

Māori tourism and Te Awa Tupua

Māori have long been involved in tourism in Aotearoa New Zealand (Te Awekotuku, Citation1981), with a tradition of generosity in the hosting of people, characterised as manaakitanga (Barnett, Citation2001; Mika, Citation2014; Papakura, Citation1991). Although Māori initially controlled the development of tourism (Bremner, Citation2013), colonialism and its racist constructions (Meihana, Citation2015; Smith, Citation1999) reduced Māori participation to the roles of cultural performer, artisan, or guide (Amoamo & Thompson, Citation2010, cited in Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, et al., Citation2018). Colonial legacies continue to hamper Māori tourism (Horn & Tahi, Citation2009), as they do for other Indigenous groups (Bunten & Graburn, Citation2018). Furthermore, what constitutes success in tourism has tended to be moulded on normative economic conventions of self-interest and accumulation, devoid of political, identity and equity considerations (Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, et al., Citation2018). Peredo and McLean (Citation2013) argue that the economic logic of market-based assistance for Indigenous entrepreneurs results in development mistakes that fail to account for the importance of social ties, social value and social exchange. In the vein of this plurality, Māori entrepreneurs increasingly see tourism as a means of securing self-determined economic development (Tretiakov et al., Citation2020), which requires novel forms of economy and enterprise to account for their indigeneity (Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, et al., Citation2018), and the “coexistence of traditional and nontraditional methods of organising economic activity” (Mika et al., Citation2019, p. 374).

The Whanganui Māori Regional Tourism Organisation (Citation2020, p. 1) was established in 2003 by Māori tourism operators with the support of Whanganui iwi (tribes) to “lead and empower Māori tourism from the mountain to the sea.” It does this by promoting the authenticity and cultural and spiritual significance of the Whanganui River as a destination, and by coordinating Māori tourism activities on the river. The organisation’s chair, Hayden Potaka, initiated a process to update the organisation’s strategy based on principles of sustainability, quality infrastructure, and ecocultural tourism (Whanganui Māori Regional Tourism Organisation, Citation2020). Hayden sees the organisation as leveraging off and contributing to existing strategies for Māori economic development in the region (Mika et al., Citation2016).

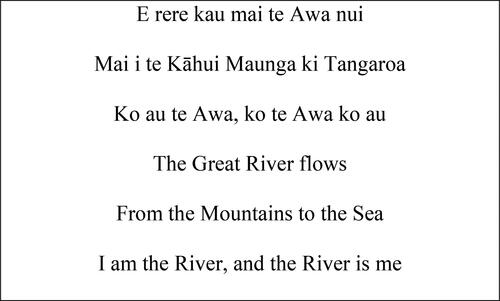

Te Awa Tupua—the Whanganui River—has significant spiritual and material meaning for the Māori people of Whanganui as the site of an 800-year long relationship that was severed through colonial settlement and is only now being restored through treaty settlements. The whakataukī (tribal proverb) in speaks to the indivisibility of the Whanganui awa (river) and the identity of local iwi (tribes) (Waitangi Tribunal, Citation1999). The Whanganui River runs for 290 kilometres from Mount Tongariro to the Tasman Sea, and passes through the three local government districts of Ruapehu, Rangitīkei, and Whanganui and the whenua (lands) of three related tribal groupings—Hinengākau of the upper river, Tama Ūpoko of the middle reaches, and Tūpoho of the lower Whanganui (Young, Citation2017). It flows through the Whanganui National Park, past several settlements of historical and cultural significance, and through the city of Whanganui. The Māori tourism enterprises we engaged with are situated along a depopulated stretch of the river.

On 14 October 1990, Hikaia Amohia and others of the Whanganui Māori Trust Board submitted a treaty claim (Wai 167) to the Waitangi Tribunal, arguing that the Crown had breached their unextinguished customary rights of tino rangatiratanga (self-determination) and kaitiakitanga (guardianship) over the Whanganui River (Waitangi Tribunal, Citation1999). The government’s development of the Whanganui River as a tourist route in the 1890s, for example, effectively forced Te Ātihaunui-a-Pāpārangi (the principal tribe of the Whanganui River) from the river, their lands, and their fishing grounds (Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Citation2019). On 8 June 1999, the tribunal established that Ātihaunui did indeed own the Whanganui River “in its entirety” and that the Crown had deprived Ātihaunui of “their possession and control of the Whanganui River” (Waitangi Tribunal, Citation1999, p. xi).

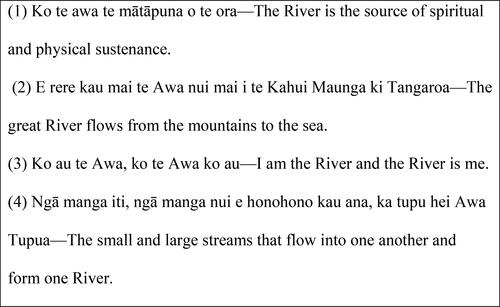

Of significance to Whanganui iwi is a treaty settlement signed at Ruakā Marae in Rānana on 5 August 2014 (Office of Treaty Settlements, Citation2014; Whanganui Iwi & The Crown, 2014a). The settlement—passed into law on 20 March 2017 via Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017—represents the culmination of over 100 years of struggle by the iwi to protect their special bond with the Whanganui River (Ngā Ngā Tāngata Tiaki o Whanganui, Citation2020). The deed of settlement—Ruruku Whakatupua—comprises two distinct documents. The first—Te mana o Te Awa Tupua—recognises the mana (status, power, and authority) of the Whanganui River and its tributaries as a single physical and spiritual entity (Whanganui Iwi & The Crown, 2014a). The second—Te mana o te iwi o Whanganui—is a deed recognising the mana of the tribes of the Whanganui River (Whanganui Iwi & The Crown, 2014b), affirming Ngā Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui as their post-settlement governance entity and outlining the agreed redress. Under the settlement, legal personhood is conferred on Te Awa Tupua—a novel legal principle (Morris & Ruru, Citation2010) but one consistent with a Māori world view (Royal, Citation2003). Te Pou Tupua is the human face of the river, vested in two people appointed by Māori and the Crown who are to act and speak on behalf of Te Awa Tupua, and uphold the status of Te Awa Tupua and Tupua te Kawa, as the natural law and values which bind the people to the river and the river to the people (see ) (Whanganui Iwi & The Crown, 2014a).

Figure 2. Tupua te Kawa—Intrinsic values of Te Awa Tupua.

Source: Whanganui Iwi and The Crown (2014a, p. 7)

Contextually, then, Māori tourism on the Whanganui River occurs amid the collective aspirations of Māori tourism operators for equitable, quality, sustainable, and culturally authentic tourism. This is a system supposedly predicated upon treaty-based relationships with Māori and a treaty settlement that privileges a Māori view of the river, and provides legal and financial means by which to restore the relationship of the people with the river, and with one another. Implicit within this context are the notions of indigeneity, peace, justice, and sustainability, which are foregrounded as theoretical anchors for analysis in the next section.

Theoretical positioning

Indigeneity and tourism

Indigenous tourism requires an understanding of indigeneity and how tourism is shaped by it. Although comprising more than 6 per cent of the world’s population, Indigenous peoples make up 15 per cent of the extreme poor, face life expectency that is up to 20 years lower than that of non-Indigenous people, and their status and rights may not be recognised by the states in which they live (World Bank, Citation2019). Yet, Indigenous peoples are increasingly engaging in economic development as emancipatory processes of Indigenous self-determination and sustainable development across multiple sectors (Henry et al., Citation2017; Mika et al., Citation2017; Peredo & Anderson, Citation2006), including in tourism (Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, et al., Citation2018; Jacobsen, Citation2017; Pereiro, Citation2016; Whitford & Ruhanen, Citation2016).

Indigeneity is evident in Indigenous people’s world views, which Harris and Wasilewski (Citation2004) characterise as relational, responsible, reciprocal, and redistributive. Venkateswar et al. (Citation2011) see indigeneity as ‘a way of being’ expressed in relationships between people and nature, Indigenous activism, and the assertion of Indigenous rights. Indigeneity tends to be viewed by non-Indigenous peoples as a threat to state sovereignty and the presumption of hegemonic postcolonial cultures and institutions (Durie, Citation2004; Dutta, Citation2015; Lightfoot, Citation2016). Bunten and Graburn (Citation2018) suggest that indigeneity is thus contingent on permissible postcolonial categorisations, where states ‘otherise,’ objectify, and appropriate representations of indigeneity as semiotic projections for consumption of the touristic gaze.

For Indigenous tourism to develop equitably, the spirituality of Indigenous peoples must be respected (UNWTO., Citation2020). An appreciation of Indigenous spirituality (Venkateswar et al., Citation2011) requires personal experience of it with community consent (UNWTO., Citation2020), lest unfortunate cross-cultural encounters ensue (see for example, Venkateswar, Citation2018). Spirituality is embedded within Indigenous world views, which are “both spiritual and material… [expressions] of identity and culture” (Mika et al., Citation2020, p. 261). A fundamental principle of Indigenous world views is that all things—people, flora, fauna and planet—are interrelated, obliging people to care for the Earth as one would a mother, and for the Earth to care for her people as kin (Colbourne, Citation2017; Gladstone, Citation2018; Hēnare, Citation2001; Knudtson & Suzuki, Citation1997).

A Māori world view is broadly consistent with Harris and Wasilewski (Citation2004) principles, but is grounded in tribally-specific knowledge about the origins of the universe (Mead, Citation2017; Royal, Citation2003). While Royal (Citation2005) uses aronga (outlook) to focus on a Māori orientation to the world, Durie (Citation2017) uses te ao Māori (the Māori world) to denote the totality of the Māori world, both its physical and metaphysical elements. In Aotearoa New Zealand, te ao Māori—a Māori world view—imbues Māori tourism with the interrelatedness and the intertemporality of all things as manifestations of localised indigeneity, but this is also inflected with the colonial Christian legacy with which it has interacted since early settlement.

Peace and tourism

Whether peace is a predicate or consequence of Indigenous tourism, some understanding of the term from Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives is necessary to move toward consensus about its relevance and meaning for Māori tourism on the Whanganui River. D'Amore (Citation1988) contends that peace through tourism is possible and desirable as an unofficial way of generating goodwill, trust, and understanding between culturally diverse peoples, catalysing trade, investment, and exchanges of people and ideas. Moreover, D'Amore (Citation1988) urges a move away from negative definitions of peace as the absence of war or violence toward positive conceptualisations of peace as unity, tranquillity, and freedom between humans and nonhumans. Litvin (Citation1998) challenges D'Amore’s (Citation1988) view as conjectural, instead seeing tourism as benefiting from peace rather than inducing it because without peace tourism cannot proceed. D'Amore (Citation1988) and Litvin (Citation1998) leave unresolved a positive vision for peace; Indigenous perspectives offer possibilities for resolution. Verbos et al. (Citation2017a, p. 1) refer to a “hopeful vision for Mother Earth if we begin to remember our interconnectedness,” a view generated by Indigenous grandmothers. In recognising Indigenous rights and imploring educators and enterprises to appropriately include Indigenous peoples, the United Nations presents a vision for the peaceful coexistence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples (Verbos et al., Citation2017a).

Indigenous forms of peace in Aotearoa New Zealand necessarily defer to Indigenous knowledge of the Māori god of peace—Rongo, also known as Rongomaraeroa and Rongomātāne—whose domain extends to peace-making, agriculture, and human generosity (Best, Citation1976). Karena (Citation2020) characterises the epistemology of Rongo as relying less on state coercion and more on culturally-centred ontologies, such as hohou i te rongo (allowing peace to enter), as metaphors for peace-making and peace pacts.

As much as the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840 was a treaty of cession it was also a treaty of peace because it contained within it provision for power sharing between Māori and the British Monarch (Orange, Citation1987). The treaty was not preceded by civil conflict, but such conflict soon followed through the colonial government dishonouring it and the courts setting it aside (Belich, Citation1998; Durie, Citation1998). The pathway to peace in Aotearoa New Zealand had been obvious to Māori from the signing of the treaty—simply, to honour it (Kelsey, Citation1990; Mutu, Citation2019; Orange, Citation1987). Honouring the treaty for Māori means enacting a decolonising agenda underpinned by constitutional reform that upholds mana motuhake (tribal sovereignty) (Burrows et al., Citation2013; Mutu, Citation2012, Citation2019).

Justice and tourism

Indigenous tourism must be just, but what constitutes justice is a complex matter. In the non-Indigenous world, justice has an illustrious Western tradition, helping decide what is right by reference to, for example, what is fair and lawful (Aristotle), what is due (Augustine), what is rational (Aquinas), and the protection of property (Hume), freedom (Kant), and liberty (Rawls) (Pomerleau, Citation2019). Using the Justinian (Citation1913, p. 5) definition of justice as “the set and constant purpose which gives to every man his due,” Miller (Citation2017) explicates justice in ways that make sense and have credence in non-Indigenous settings. Watene (Citation2016), however, finds that the omission of Indigenous peoples from justice theorising has not been sufficiently rectified by liberal theories, such as Kymlicka’s (Citation1995, Citation2002) multiculturalism and Anaya’s (Citation2004) self-determination. Instead, she argues that actual engagement with Indigenous peoples is necessary to adequately comprehend an Indigenous view of justice, which has potential to reframe how justice is understood and applied generally. Watene (Citation2016) argues that Indigenous peoples see justice as healing and as relational, evident in processes that redress colonial trauma, legitimise indigeneity, and restore relationships. An Indigenous view, she argues, is consistent with the capabilities approach of Sen (Citation1999), which holds that meaningful development is tied to the freedom to pursue and sustain lives that matter to those people. A precolonial Māori view of justice is to be found in the maintenance of balance achieved through concepts of utu (reciprocity) (Firth, Citation1929), which may manifest as gift-giving (Hēnare, Citation2018) on the one hand, or muru (ritual compensation) on the other (Walker, Citation2004).

Under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 Māori have been able to make claims to the Waitangi Tribunal for breaches of the treaty by the Crown from 1840 and seek redress from government through treaty settlements (Kawharu, Citation1989; Tapsell et al., Citation2007). For the Crown, treaty settlements offer a middle-ground in which the government defines the process toward the just resolution of past wrongs within the confines of political settlements (Office of Treaty Settlements, Citation2015). Kawharu (Citation2018) is critical of treaty settlements, however, because they rely on Crown-defined processes, which have been divisive, adversarial, exhausting, and protracted, leaving post-settled tribes with capacity challenges and a public unprepared for iwi whose rangatiratanga has been restored. Instead, Kawharu (Citation2018) favours the recent reconciliation process of Parihaka with its attention on a future-focused relationship of peaceful coexistence with the Crown. Hēnare (Citation2011) concurs with Kawharu (Citation2018), arguing that tikanga Māori (Māori values), underscored by the assurances of the treaty (Kawharu, Citation1989; Waitangi Tribunal, Citation2016) provide principles for lasting peace, justice, prosperity, and guidance for contemporary enterprise among Māori. Thus, we contend that treaty settlements appear as devices for both peace-making and economy-making, with tourism a logical candidate for investment (Amoamo, Ruwhiu, et al., Citation2018; Barry et al., Citation2020).

Sustainability and tourism

When concerns are raised about the negative effects of tourism on natural ecosystems (Butler, Citation2018), the denigration of significant cultural sites (Harrison, Citation2001), and disparities in the spread of benefits (Scheyvens, Citation2011), sustainability has been proffered as the answer. The World Commission on Environment and Development defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, Citation1987, p. 41). With its focus on meeting human needs from within ecological and socio-technological limits, sustainable development appears to present an unrivalled opportunity for a better life (Brundtland, Citation1987). Yet, even at its inception, Brundtland (Citation1987) recognised the enormity of the challenge for diverse societies to accept integrative and comprehensive approaches to development. Furthermore, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been criticised for favouring growth over sufficiency (Hall, Citation2019), inconsistencies, measurement and evaluative difficulties (Swain, Citation2018), and insufficiently including Indigenous perspectives (Yap & Watene, Citation2019).

Virtanen et al. (Citation2020) advocate for the inclusion of Indigenous views on sustainability because of the bio-cultural diversity within Indigenous communities. Sustainability from an Indigenous perspective, according to Virtanen et al. (Citation2020), is contextual, emanating from particular landscapes, entailing human and nonhuman sociality and a capacity for the coexistence of all entities. Indigenous conceptualisations of sustainability challenge the universalism of the SDGs, which rely on individualistic, human-centred, and singular approaches rather than viewing sustainability as locally lived (Virtanen et al., Citation2020). While the SDGs point to the potential for sustainable development through tourism (Scheyvens, Citation2018), including empowering Indigenous participation in tourism (Mendoza-Ramos & Prideaux, Citation2018), reservations remain. Boluk et al. (Citation2019), for example, argue that sustainable tourism requires greater consideration of Indigenous world views because the lingering effects of colonisation entrench inequity, but also because “Indigenous ontologies can offer… a transformed global order” (p. 853).

A Māori perspective on sustainability is evident in the epistemology of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge), the ontology of kaitiakitanga (stewardship, guardianship), and the axiology of whakapapa (genealogy), which are indicative of a socioecological framework that is instructive for sustainability in tourism (Harmsworth & Awatere, Citation2013; Reid & Rout, Citation2020; Rout et al., Citation2020). Kaitiakitanga is accepted within resource management law and policy as a fundamental principle guiding the relationship between tribes and their ancestral lands (Crengle, Citation1993; Kawharu, Citation2000). The effect of kaitiakitanga is to prioritise environmental considerations not as an arbitrary moral restraint on growth, but because the environment is kin, an ancestor who precedes humanity in the hierarchy of genealogical time and space (whakapapa) and upon whom humans depend for their wellbeing (Hēnare, Citation2015; Te Rito, Citation2007). Such a view may be problematic for those unused to evaluating the pragmatism of metaphysical Indigenous knowledge (Pratt, Citation2002), yet such knowledge illuminates a relational view of sustainability in tourism as an intrinsic ethical code rather than enforced compliance with an external legal code (Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, et al., Citation2018; Boluk et al., Citation2019).

Methodology

Indigenous methodologies

Our research is embedded in Māori cosmologies and foregrounds Indigenous methodologies (Martin & Hazel, Citation2020). Indigenous methodologies are culturally embedded in the diversity of Indigenous peoples' world views, institutions, circumstances and aspirations (Henry & Foley, Citation2018; Hudson et al., Citation2010; Kovach, Citation2010; Smith, Citation1999; Vivian et al., Citation2017). In Aotearoa New Zealand, Indigenous methodologies are those that develop Māori knowledge, improve Māori outcomes, involve Māori at all levels, and use Māori and non-Māori methods (Cunningham, Citation2000; Martin & Hazel, Citation2020). Māori-centred research and kaupapa Māori research are two such methodologies, distinguished by the degree to which Māori control and benefit from research. While Māori-centred research produces Māori knowledge, the knowledge is evaluated against dual standards—Māori and mainstream (Cunningham, Citation2000). Kaupapa Māori research is research by, for, and with Māori (Smith, Citation1999), which is culturally affirming and transformative (Smith, Citation1997). In kaupapa Māori research, non-Māori contributions are possible, provided the researcher’s record of research “lends legitimacy to their work” (Smith et al., Citation2012, p. 20).

To explore our research question we used Māori-centred organisational ethnographic methods, including interviews, observation, and use of published information to produce three case studies of Māori tourism enterprises on the Whanganui River (Ybema et al., Citation2009). To facilitate our engagement with these enterprises, we contacted Hayden Potaka, a Māori tourism entrepreneur who agreed to assist the research. Hayden arranged visits to four Māori tourism enterprises along Te Awa Tupua over two days in April 2019, dinner with several other Māori tourism entrepreneurs at a Māori-owned restaurant, and opportunities to share preliminary findings with Māori and iwi tourism enterprises in the Whanganui-Manawatū region. Four interviews with Māori entrepreneurs were conducted ranging in duration from 60 minutes to over two hours, which were primarily in English. Participants were provided with information sheets and consent forms, and interviews were audio recorded (or notes were taken), consistent with the low risk ethics notification we received (reference number: 4000020654). Low risk means the researchers are responsible for the ethical conduct of the research.

Of the three case studies, two are private, family-owned Māori enterprises (Unique Whanganui River Experience and Whanganui River Adventure) and the third is a hapū-based enterprise (Te Ao Hou Marae). Interviews began with questions about where they were born and raised. Beginning interviews with ‘origin stories’ helps establish common ground through the sharing of mutually known people, places, and interests, and is an important method of Māori research centring on whakawhanaungatanga—reaffirming genealogical connections (Bishop, Citation1996). Questions then turned to how the enterprise came to be, its cultural values, approach to sustainability and entrepreneurial aspirations.

Positionality of the researchers

Positionality in Indigenous research involves giving an account of oneself to expose differences in perception, power, and privilege and establish grounds for commonality, relationality, and decoloniality between the researcher and the researched (Moffat, Citation2016). While collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers brings diverse positionalities, Jones and Jenkins (Citation2014) suggest a more uneasy relationship is desirable based on learning from, rather than about, Indigenous people lest the coloniality that one seeks to displace is instead invigorated. The authors of this paper are of different ethnicities and genders. The first coauthor is male and identifies as Māori (New Zealander of Māori descent), but recognises his Scottish, French and Irish ancestry, whose research adheres to kaupapa Māori theory, but integrates within this elements of Western knowledge. The second coauthor is female and identifies as Pākehā (New Zealander of European descent) with Netherlands and Slovenian ancestry, whose upbringing imbued her with an affinity for the bio-cultural diversity of Aotearoa, a strong sense of social justice, and a deep respect for Māori and Pasifika peoples. Our respective positions have influenced the research by affirming a Māori world view; by the complementarity of using non-Māori knowledge for Māori-defined purposes; and the requisite acknowledgement of university standards for what counts as knowledge.

Findings

Unique Whanganui River experience

Unique Whanganui River Experience is a private Māori tourism enterprise owned and operated by Hayden Potaka, which he started in 2018. The enterprise specialises in providing guided canoe tours through the “heart of the Whanganui River, places inaccessible by land” (Unique Whanganui River Experience, Citation2020, p. 1). Visitors are hosted by a “team of cultural navigators” who have all completed the Tira Hoe Waka—an annual 12-day spiritual journey by canoe along the Whanganui River for iwi members who learn the culture, history, and language of their iwi (Stowell, Citation2020). A unique feature of some of the products offered is a gourmet dining experience incorporating produce of the bush (Unique Whanganui River Experience, Citation2020). Trips range from 3-5 days for groups of 4-10 guests.

On starting the business, Hayden says “I gave up my job and I saw this business on [an online auction site]—[a] canoeing business on the Whanganui River. My son is called Ahurei. Ahurei means unique. So I thought: why not? So, I bought the Unique Whanganui River Experience.” Hayden grew up on the river and wanted to share his experience and his love of the river with others, while incorporating elements that he had developed in other ventures:

At the end of last year… I thought, ‘Bloody hell, I’m going to get this sort of thing going on the river, to mix in sort of fine dining and then also canoeing’. Just really connecting with the river and really gaining that spiritual connection… get them trained for river crafting, and then back to the site to… have a cocktail before dinner and just chill out and mingle.

A key motivation for Hayden in starting the venture was ensuring his children were well connected to their culture. He explains: “I think the biggest aspiration is for my kids to know and identify themselves with the river.” Hayden found it was essential to have confidence in his ability to get the business going because “there was nobody out there supporting businesses … [so I] just went and did it.”

On the spirituality of the river, Hayden says:

I developed [these tour packages] because I believed that there’s a spiritual side to the river and people who want to disengage from city life and come out and just engage with nature is magic. When you’re able to do that, in the solitude of the middle reaches of the river, and get the real understanding of the whakataukī [proverb]– ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au. So, I am the river and the river is me, and what that means.

We elaborate further on the spiritual dimension to Māori tourism in the next case study.

Te Ao Hou Marae

A marae is a sacred courtyard in the front of a tribal meeting house surrounded by other buildings, which has a central role in Māori communities (Karetu, Citation1992; Tauroa & Tauroa, Citation1986). Te Ao Hou Marae was established in 1978. The marae is situated in Aramoho on the banks of the Whanganui River near the Whanganui township. Geoff Hipango, who was raised in a house adjacent to the marae and is the marae chairperson, provided an account of the marae and its engagement in tourism. Geoff has resided full time on the marae since 2017. His mission is to revive the marae. In the context of “the door being open for our community [and] our tribal gatherings, tourism came out as a possible strategy to look at some sustainable economic development.” This “coincided with… the recognition of the Whanganui River and its status,” which has received worldwide attention.

As more people arrived wanting to learn about the Whanganui River, the marae was offered as a space for Māori tourism operators to prepare visitors or debrief them. A collaboration emerged that worked—the operators organise the tours; the marae hosts the visitors and “make them feel welcome.” This negated the need for the marae to engage in direct marketing of its offering. For Geoff, “rather than catering for the bus loads,” the focus has been on hosting smaller groups with an environmental research interest. This has “allowed us to share stories… of why we keep saying, ‘I am the river and the river is me,’ [and] actually our iwi narrative is important for the world to know, especially… around global climate change.” The intimacy of the river experience affects some visitors very deeply: “[When] they did come back here, some of them were breaking down crying; there was real transformation that occurred. Really, I think part of that is… a connection back to nature to see yourself through a different lens.”

An experience of the river from the vantage point of the marae is something that not only appeals to international visitors, but also to domestic visitors. Geoff explains: “You know, there’s this saying that we use, ‘globally hot, locally not’. We’ve got a lot within our community that live here that have never been on a marae… [and] if we do need to shift in terms of relationships then there has to be more importance on the [domestic market, particularly, among non-Māori].” There is a view that sees the legal status of the Whanganui River as an unrealised economic gain, but there is an important distinction to be grasped, Geoff suggests, and that is, that the Whanganui River and Te Awa Tupua “are not necessarily the same thing.” Te Awa Tupua is an “iwi narrative… that is best articulated in [the] authentic environment of marae… with our people.” Yet, when looking through local tourism publicity, Geoff notes that “[the marae is] not visible,” which he attributes in part to a slower pace of development. With the Māori tourism operators, though, “there’s a trust, we’ve got decades… of knowing one another… we’re on the same wavelength; it’s storytelling in a combination.”

Whanganui River Adventures

Whanganui River Adventures (Citation2019) is a Māori tourism enterprise based at Pipiriki, a settlement along the middle reaches of the Whanganui River, owned and operated by Ken and Josephine Haworth as a family business. Josephine’s husband Ken carries out the maintenance, and Ken, Josephine’s brother, and their nephew take the tours. Both Ken and Josephine’s families have been involved in jet boating for many years. In 1998, they purchased the family business, Pipiriki Jet Boat Tours, and in 2003 purchased Riverspirit Jet Boat Tours, combining it with their existing business to form Whanganui River Adventures. The offering includes guided jet boating, canoe and biking tours, ranging from a few hours to several days. In the busy season (October to April), the business employs 5-7 staff, almost all of whom are whānau (family), which is a deliberate strategy to keep locals employed. Josephine recalls that there was once 300 or more people living at Pipiriki, but now the population is around 30 people. Without tourism, Josephine says there would be even fewer.

The business is located in an old school that is leased from a Māori land incorporation: this “puts the pūtea [funds] back into our own people,” says Josephine. Josephine says that “because [the business is on] Māori land it makes it hard for us as a Māori business—with banks, we can’t get loans. [We] have to do things the hard way—saving. We built this business slowly to what we could afford.”

Josephine says a distinctive feature of the tour is the history:

It’s something we don’t have to read about. Outsiders try to copy what we do, especially the history side of things, but it’s a lived history of growing up on the river and on Māori land. We get asked all the time since the river gained legal status, what does the awa [river] mean to you? It’s our food basket, our workplace, our place to play… It’s always been that.

On sustainability, Josephine says,

We do one tour per day, so there’s less impact. With four boats, that’s 60 people max a day. We won’t do extra trips even if there’s more demand—we’ll pass those customers on to others; we’d prefer to share the load. [In Māori tourism fora] our discussions are about quality, not quantity, and culture. At general tourism forums it’s all about the numbers.

There is a strong ethic of reciprocity and wanting to support the community. The business invested in the school when it was operating, helped with the playground, and provided employment for locals. But, as Josephine adds, “it’s hard in a little community, too. Some see us as ‘Oh, they’ve got plenty of money’… we just focus on moving forward.”

Discussion

Indigeneity

Indigenous tourism cannot exist without indigeneity. Indigeneity denotes a metaphysical world view whose central premise is the interrelatedness of all things. Indigeneity orients human thought toward holism and human action toward the wellbeing of all things. What is contentious is the extent to which the Indigenous people, whose indigeneity is on offer in tourism, have control of the journey through local narrative. Although coloniality has substantially displaced indigeneity, recognition of Indigenous rights, Indigenous self-determination, and Indigenous knowledge provide epistemic space for indigeneity to inform Indigenous enterprising ontologies (Awatere et al., Citation2017; Dana, Citation2015; Mika, Citation2020; Peredo & McLean, Citation2013).

The tribal narrative—ko au te awa, ko te awa ko (I am the river, the river is me)—evidences a socioecological unity between the Whanganui iwi (tribe) and the Whanganui awa (river) that has been promulgated in law, enabled by treaty settlement, and enacted by tribal institutions. Māori tourism operators act as authentic voices and stewards of tribal indigeneity because they are of the Whanganui River.

Three key findings on indigeneity in Indigenous tourism are evident in the case studies: (1) tribal indigeneity has meaning for Māori and non-Māori that is both spiritual and material, but it must be governed, preserved and shared by tribes; (2) sustaining tribal indigeneity is important for the identity and wellbeing of current and future generations of tribal members, which Māori tourism operators contribute to and draw from as motivation for initiating enterprise and the capability for delivering culturally authentic offerings; (3) while legal personality of the river via settlement has brought public attention to the innovation and substance of tribal indigeneity, it is susceptible to misrepresentation, appropriation, and indifference because the extent to which tribal values (Tupua te Kawa) are generally applicable on the river is still being established.

The research finds that the spiritual dimension of tribal indigeneity is consistent with syncretistic spirituality of the Rangiwai (Citation2018) framework of atuatanga—a blending of Christian religiosity and Māori spirituality. This syncretism manifests as spiritual capital embodied within Māori entrepreneurs (Mika, Citation2018), with the potential for tourists to experience spiritual wellbeing in their encounters with the river. Further, the maintenance of tribal knowledge through the immersion of tribal members in their culture facilitates and supports the identity work of indigeneity, exemplified by tira hoe waka. The case studies reveal that the unique identity of the river is prone to being commodified by industry and government for the collective good of all without adequate consideration of Indigenous perspectives, rights, and interests. Yet, Māori institutional capacity at the iwi (Ngā Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui), industry (Whanganui Māori Regional Tourism Organisation) and firm-level (Māori tourism operators) exists to contribute to a more balanced view of the role of indigeneity in the wellbeing and prosperity of the community through tourism.

Peace

In the literature, tourism is viewed as either a catalyst or beneficiary of peace, where it is generally defined negatively as an absence of war and violence. Yet, idealisations of peace in transcendent terms as values of unity and harmony come close to the Indigenous predicate of the interrelatedness of all things, constituted in reciprocal relations among humans and between humans and nonhumans. Beyond the idealism of peace as harmonious relations, deference to the Māori epistemology of the god of peace—Rongomātāne—reveals cultural ontologies of peace-making, which have historically manifested as post-conflict peace pacts between tribes and nonviolent resistance to colonial conquest (Karena, Citation2020). The Treaty of Waitangi provided terms for peace conditional on preserving tribal self-determination and shared prosperity that were negated by colonisation and are now finding restitution via treaty settlements. For Māori, realising a positive vision of peace is contingent on appropriate and equitable power sharing through constitutional reform, which honours the treaty and enacts decoloniality (Boulton & Te Kawa, Citation2020; Durie, Citation1998).

The research suggests that peace in Indigenous tourism is about power sharing, access to fair and adequate means by which to live a good life, and acceptance of the legitimacy of Indigenous notions of peace and peace-making. The case studies show that peace has several dimensions: (1) an openess to encountering the river as a spiritual and material being; (2) engaging in tourism enterprise on the river to fulfil aspirations for cultural continuity and shared wellbeing; and (3) an evolving power sharing between Māori and the Crown.

In two of the cases, tourists found peace as personal tranquility and healing through curated encounters with the river. As these cases highlight, peace is conditional on the means to sustain physical, cultural, and spiritual needs. Māori tourism enterprises demonstrated this by participating at scales consistent with their identity and aspirations. For example, Te Ao Hou Marae saw its role in tourism as a medium for authentic sharing of the tribal narrative and sustaining itself as a marae through enterprise. Economic gain was a lower-order priority for Unique Whanganui River Experience than ensuring family and tribal members had the opportunity to maintain and share their culture. Peace for Whanganui River Adventures is characterised as village harmony. In Māori terms, this may be expressed as hau kāinga—the vitality of the village, where the people of the land on which the enterprise operates contribute to and benefit from the tourism offering. Fair and appropriate power sharing between Māori and non-Māori lies at the heart of peaceful coexistence and shared prosperity for Māori generally, and for Māori tourism in particular. The Whanganui River treaty settlement provides a basis for continuing peace between Māori and the Crown, local government, and mainstream industry, but the role of the settlement in tourism is still unfolding.

Justice

Our analysis of the literature suggests that justice in Indigenous tourism is about fair and equitable access to the means by which to live a good life, restoring relationships by healing past trauma and legitimising indigeneity (Hēnare, Citation2011; Mutu, Citation2019; Watene, Citation2016). Treaty settlements are the primary policy instrument through which justice for Māori in these terms is available. Settlements are intended to provide legal and financial means for rebuilding tribal nations. Tribal nation-building is, however, contingent on the sufficiency of the redress, the quality of post-settlement governance, and the value of properties available, among other considerations (Te Aho). Treaty settlements have been criticised as preserving postcolonial dominance and granting tribes limited statutory power and resources (Kawharu, Citation2018). Thus, it falls to tribal entrepreneurs to pursue Indigenous tourism rather than the tribe itself (Mika et al., Citation2019).

In the Whanganui River settlement, four provisions for justice are evident: (1) recognising Te Awa Tupua in law as a person; (2) the codification of Indigenous values for the river (Tupua te Kawa, see ); (3) the provision of a human voice to speak for the river (Te Pou Tupua); and (4) financial redress and a governance entity to fulfil post-settlement obligations and aspirations. The effect of these provisions is to oblige tourism institutions to engage in treaty-based relationships with the iwi, establish an ethical, moral and pragmatic framework for sector and firm-level engagement with the river, and to guide entrepreneurs on their obligation to uphold the indigeneity of the river. All three case studies recognise the significance of the Whanganui River settlement, but its implications for tourism on the river generally, and for their particular enterprises, is less clear. Unique Whanganui River Experience found enterprise assistance from the iwi was unavailable for investment in a new business. Te Ao Hou Marae spoke about the importance of sharing the tribal narrative with the world, and with local non-Māori who may not have had a marae experience. Whanganui River Adventures is concerned with providing livelihoods for community members to remain living on Māori land by the river. Justice in Indigenous tourism on the river arises in three ways: (1) what the tribe can do for the river and tribal members as a consequence of the treaty settlement despite the constraints; (2) what tribal entrepreneurs like those in our case studies can do to provide means by which to determine and lead a ‘good life’ (Hēnare, Citation2011); and (3) what the tourism system can do to uphold the mana (power and authority) of the river and of the tribe.

Sustainability

Sustainability in Indigenous tourism is about the extent to which a kinship-based approach, rather than simply a goal-oriented approach, can be operationalised to help the tourism system, sector, and operators meet the needs of current and future generations. When human and nonhuman elements are viewed as kin (Harmsworth & Awatere, Citation2013), a new socioecological framework for sustainability grounded in Indigenous knowledge emerges that requires careful articulation and evaluation. This framework fundamentally centres on the principle of kaitiakitanga (stewardship, guardianship), which obliges responsible use and protection of natural resources for the coexistence and shared wellbeing of people and nature (Kawharu, Citation2000). While kaitiakitanga is widely used in environmental policy and practice across mulitple sectors (Cherrington, Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Thompson, Citation2018), operationalising and evaluating its effect in business is relatively recent (Maxwell et al., Citation2020; Reid & Rout, Citation2020; Spiller et al., Citation2011).

In this research, we found that tourism is not all about the numbers—customers and revenue. Unbridled growth of both tourists and enterprises on the river falls outside the ambit of what constitutes sustainable tourism, according to the Māori tourism operators with whom we spoke. Rather than burden the river with the waste that additional visitors create, operators would forgo tours and pass them on to other operators who have a higher propensity and capacity for growth. It appears, then, that there may be a socioecological dissonance between Māori and non-Māori tourism operators regarding commercial growth. By this we mean that the social and ecological limits that Māori tourism operators work to are set at levels that differ from industry norms; however, we cannot argue this with certainty as the views of non-Māori operators were not canvassed in this research.

This presents a conundrum: how to reconcile different perspectives on the growth of the tourism sector with regard to planetary boundaries? This is a question of sustainability that is unlikely to be easily settled by tourism operators alone. Instead, institutional actors must be invited to help, starting with Te Awa Tupua itself and the voice of the awa (river), Te Pou Tupua. Ngā Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui, and the peoples of Hinengākau, Tama Ūpoko, and Tūpoho, must also be involved, followed by the principal regulators—the Department of Conservation, the Whanganui District Council, and tourism sector organisations, including the Whanganui Māori Regional Tourism Organisation. The perspectives of these actors remain questions for further research, policy, and practice. Next, we propose a model of Indigenous tourism to bring theory and findings together.

Foundations for Indigenous tourism—kaupapa tāpoi

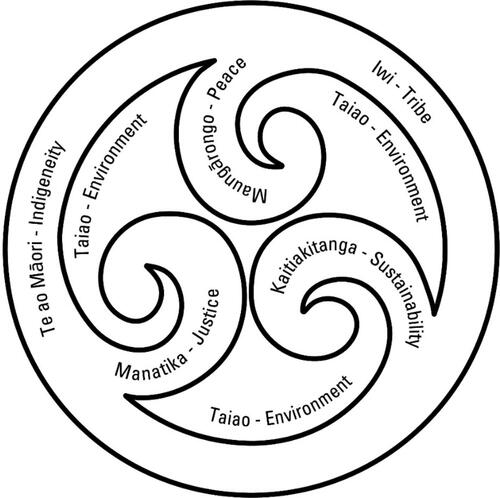

In , intersections of maungārongo (peace), manatika (justice), kaitiakitanga (sustainability), te ao Māori (indigeneity), and iwi (tribe) are depicted as kaupapa tāpoi—foundations for Indigenous tourism. The model privileges Māori language, Māori concepts and Māori symbolism because of the focus on Te Awa Tupua, the Whanganui River, but the principles may be generalisable as foundations for Indigenous tourism elsewhere.

The foundations—kaupapa tāpoi—are enclosed in a circle, which signifies the unity, perpetuity, and holism of Papatūānuku, Earth Mother, represented in the model by te taiao—the natural environment—as the foundation from which other elements grow. While individual tribal entrepreneurs as Māori tourism operators were the focus of this research, they acknowledge the tribe as the custodian of tribal narrative. Thus, te ao Māori (a Māori world view) offers a view of indigeneity particular to Aotearoa New Zealand, but it more precisely manifests locally as the indigeneity of hapū and iwi knowledge around which Indigenous tourism in situ is configured. Intersecting principles of indigeneity appear in the three koru (spiral motifs) that represent new life, growth and development, and a strong connection to a place of origin (te taiao). These principles are maungārongo—peace, manatika—justice, and kaitiakitanga—sustainability. The English and Māori words of kaupapa tāpoi are neither equivalent nor substitutes, but represent different perspectives on related principles for Indigenous tourism. For instance, treaty settlements are intended as instruments of manatika (justice) by addressing past grievances, maungārongo (peace) by redefining Māori and Crown relationships, and kaitiakitanga (sustainability) by enabling shared responsibility for tribal wellbeing. The effect is self-determined tribal development, with Indigenous tourism an example of this.

A further example of the intersection of kaupapa tāpoi is the immersion of tribal members in tribal culture, which we see as the identity work of indigeneity. The effect is to strengthen cultural capacity for Indigenous tourism, producing, for example, cultural navigators as knowledgeable, authentic and engaged operators. Relatedly, the syncretism of atuatanga (blending of religiosity and spirituality) represents a distinct basis for Indigenous tourism, which operators report has had therapeutic effects for tourists. While inward (tribal) and outward (tourist) acculturations serve different ontologies, they depict reciprocal intersections of maungārongo, manatika, and kaitiakitanga for host and visitor. Finally, kaitiakitanga is indicative of an Indigenous socioecological framework that prioritises environmental considerations because of the interrelatedness of all things. Taken together, kaupapa tāpoi may provide foundations for Indigenous tourism research, policy and practice.

Conclusion

This paper set out to discuss peace, justice, and sustainability through Indigenous tourism using case study research of Māori tourism enterprises on Te Awa Tupua, the Whanganui River. The Whanganui iwi have, through the treaty settlement process, had their relationship with their ancestor—Te Awa Tupua—reaffirmed, and are now embarking on new era of development. While the legal status of Te Awa Tupua as a person is a modern-day marvel, it gives effect to an 800-year-old spiritual socioecological relationship that has sustained the people and the river.

Indigenous tourism—the tourism enterprises, assets and activity of Indigenous peoples—offers a unique perspective on notions of peace, justice, and sustainability. As descendents of the original peoples of colonised territories, a peaceful postcolonial existence is problematic as inequity, inequality, and precarity prevail for many Indigenous peoples. Yet, the promise of a self-determining and decolonising development agenda, while possibly unsettling for some, presents a potential path to peace, justice, and sustainability through Indigenous tourism. This paper identifies five main principles that support this effort. First, treaty settlements present a framework for self-determined tribal development, with Indigenous tourism an example of this. Second, the identity work of immersing tribal members in their tribal indigeneity strengthens individual and collective capacity for Indigenous tourism. Third, Indigenous spirituality, evident in the syncretism of atuatanga, represents a distinct basis for Indigenous tourism. Fourth, an Indigenous spiritual socioecological framework that prioritises environmental considerations because of the interrelatedness of all things differentiates Indigenous tourism. Fifth, a process for recalibrating the boundary of growth in tourism is intimated by the kaupapa tāpoi model, but requires further research. These principles are constitutive of an Indigenous approach to tourism that present development advantages for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous entrepreneurs.

| Glossary of Māori words | ||

| ahurei | = | unique |

| ao Māori | = | Māori world view, Māori society |

| ao | = | world, light |

| Aotearoa | = | Land of the long white cloud, New Zealand |

| Ātihaunui | = | principal tribe of the Whanganui region |

| atua | = | god, deity |

| atuatanga | = | all things pertaining to gods and God |

| awa | = | river |

| hapū | = | subtribe |

| hau kāinga | = | vitality of the village, home people |

| hohou i te rongo | = | peace-making process |

| hou | = | new |

| iwi | = | tribe |

| kai | = | food, prefix added to verbs to make them nouns |

| kaitiakitanga | = | guardianship, stewardship, sustainability |

| kaupapa | = | purpose, principle, philosophy |

| koha | = | gift |

| koru | = | spiral motif, looped, coiled, fold |

| mana motuhake | = | separate identity, autonomy, self-determination |

| mana | = | power authority, prestige acquired by divinity and deed |

| manaakitanga | = | hospitality, kindness, generosity, care for people and land |

| manatika | = | justice |

| manuhiri | = | visitor |

| Māori | = | Indigenous people of New Zealand |

| marae | = | courtyard in front of a carved meeting house |

| mātauranga | = | knowledge |

| maungārongo | = | peace |

| muru | = | ritual compensation, forgive, pardon |

| Ngā Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui | = | Post-settlement governance entity of the Whanganui tribes |

| Pākehā | = | New Zealanders of European descent |

| Papatūānuku | = | Earth mother |

| Pipiriki | = | A settlement on the Whanganui River |

| pūtea | = | fund, finance, bank account, sum of money |

| Rānana | = | A settlement on the Whanganui River |

| rangatira | = | chief (male or female), leader, noble, high ranking person |

| Ranginui | = | Sky father |

| Rangitīkei | = | A river valley and district bordering Whanganui |

| Rongomaraeroa | = | god of peace |

| Rongomātāne | = | god of peace |

| Ruakā Marae | = | Tribal village courtyard and buildings on Whanganui River |

| Ruapehu | = | Ancestral mountain within the Tongariro National Park |

| Ruruku Whakatupua | = | Deed of Settlement of the Whanganui River |

| taiao | = | world, earth, natural environment |

| tangata whenua | = | people of the land, local people, Indigenous people |

| tangata | = | person, man, human |

| taonga | = | treasure, highly prized object, something of value |

| tāpoi | = | tourism |

| Te Ātihaunui-a-Pāpārangi | = | tribe of the Whanganui River |

| Te Awa Tupua | = | Ancestral Māori name for the Whanganui River |

| Te Pou Tupua | = | Human agents who act on behalf of Te Awa Tupua |

| tikanga | = | correct procedure, custom, rule, value and practice |

| tino rangatiratanga | = | self-determination, sovereignty, autonomy |

| Tira Hoe Waka | = | A canoe journey on the Whanganui River for iwi members |

| Tupua te Kawa | = | Customary laws and values for the Whanganui River |

| utu | = | reciprocity, payment |

| wānanga | = | meet, discuss, deliberate, consider |

| whakapapa | = | genealogy |

| whakataukī | = | proverb |

| whakawhanaungatanga | = | process of establishing relationships, relating well to others |

| whānau | = | family, extended family |

| Whanganui | = | A district in the lower North Island |

| whenua | = | land, placenta |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge te mana o Te Awa Tupua (the Whanganui River) and te mana o te iwi o Whanganui (the authority of the Whanganui tribes). We thank Associate Professor Hone Morris of Te Pūtahi-ā-Toi, Massey University, for sharing his mātauranga (knowledge), helping bring clarity and depth to Māori cultural concepts. We thank Hayden Potaka of the Whanganui Māori Regional Tourism Organisation for his support in facilitating our research on the Whanganui River. We thank the Māori tourism operators of Whanganui for their manaakitanga (generosity) in hosting us and sharing their knowledge. We thank June Lincoln and Fiona Brown of the Massey University Design Studio for turning a hand drawn depiction into a publishable image.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jason Paul Mika

Dr Mika is a senior lecturer and co-director of Te Au Ranghau, the Massey Business School Māori Business Research Centre. Dr Mika’s research focuses on Indigenous entrepreneurship, innovation and enterprise.

Regina A. Scheyvens

Professor Scheyvens is an experienced scholar who has led two Marsden projects, won a Massey research medal for supervision in 2015, and who has an international reputation for her work on sustainable tourism.

References

- Amoamo, M., Ruckstuhl, K., & Ruwhiu, D. (2018). Balancing indigenous values through diverse economies: A case study of Māori ecotourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(5), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1481452

- Amoamo, M., Ruwhiu, D., & Carter, L. (2018). Framing the Māori economy: The complex business of Māori business. MAI Journal: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, 7(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.20507/MAIJournal.2018.7.1.6

- Amoamo, M., & Thompson, A. (2010). (Re)imaging Māori tourism: Representation and cultural hybridity in postcolonial New Zealand. Tourist Studies, 10(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797610390989

- Anaya, J. S. (2004). Indigenous peoples in international law. Oxford University Press.

- Awatere, S., Mika, J. P., Hudson, M., Pauling, C., Lambert, S., & Reid, J. (2017). Whakatipu rawa mā ngā uri whakatipu: Optimising the 'Māori' in Māori economic development. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 13(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117700816

- Barnett, S. (2001). Manaakitanga: Maori hospitality–A case study of Maori accommodation providers. Tourism Management, 22(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00026-1

- Barry, P., Graham, L., & Barry, M. (2020). Iwi investment report 2019. https://www.tdb.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Iwi-Investment-Report-2019.pdf

- Belich, J. (1998). The New Zealand wars and the Victorian interpretation of racial conflict. Penguin.

- Best, E. (1976). Māori religion and mythology part 1: An account of the cosmogony, anthropogeny, religious beliefs and rites, magic and folk lore of the Māori folk of New Zealand (2nd ed.). Government Printer.

- Bishop, R. (1996). Collaborative research stories: Whakawhanaungatanga. Dunmore Press.

- Boluk, K. A., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Boulton, A., & Te Kawa, D. (2020). Raising waka, and not just yachts. https://www.psa.org.nz/assets/Uploads/ProgressiveThinking-Dr-Amohia-Deb-Te-Kawa-Raising-Waka-edited.pdf

- Bremner, H. (2013). Tourism development in the Hot Lakes District, New Zealand c. 1900. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(2), 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311301649

- Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

- Bunten, A. C., & Graburn, N. H. H. (Eds.). (2018). Indigenous tourism movements. University of Toronto Press.

- Burrows, J., O'Regan, T., Chin, P., Pihama, L., Coddington, D., Poutu, H., Cullen, M., Smith, L. T., Luxton, J., Tennent, P., Mene, B., & Walker, R. (2013). New Zealand's constitution: A report on a conversation: He kōtuinga kōrero mō te kaupapa ture o Aotearoa. Constitutional Advisory Panel - Te Ranga Kaupapa Ture, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Minister of Māori Affairs.

- Butler, R. (2018). Sustainable tourism in sensitive environments: A wolf in sheep's clothing? Sustainability, 10(6), 1789–1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061789

- Cherrington, M. (2019, November). Environmental social and governance sustainability: Ka mua, ka muri. Scope: Contemporary Research Topics (Learning & Teaching), 2019(8), 51-56.

- Colbourne, R. (2017). An understanding of Native American entrepreneurship. Small Enterprise Research, 24(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2017.1289856

- Cole, A. (2017). Towards an indigenous transdisciplinarity. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science, 8(1), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.22545/2017/00091

- Crengle, D. (1993). Taking into account the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi: Ideas for the implementation of Section 8, Resource Management Act 1991. M. f. t. Environment.

- Cunningham, C. (2000). A framework for addressing Māori knowledge in research, science and technology. Pacific Health Dialog, 7(1), 62–69.

- D'Amore, L. (1988). Tourism: The world's peace industry. Journal of Travel Research, 27(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758802700107

- Dana, L.-P. (2015). Indigenous entrepreneurship: An emerging field of research. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 14(2), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2015.067433

- Durie, M. H. (1998). Te mana, te kāwanatanga: The politics of Māori self-determination. Oxford University Press.

- Durie, M. H. (2004, February 17). Public sector reform, indigeneity and the goals of Māori development. In Commonwealth Advanced Seminar.

- Durie, M. H. (2017). Pūmau tonu te mauri: Living as Māori, now and in the future. file:///C:/Users/jpmika/Downloads/Pumau%20Tonu%20te%20Wairua%20Mason%20Durie%20(1).pdf

- Dutta, M. J. (2015). Decolonizing communication for social change: A culture-centered approach. Communication Theory, 25(2), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12067

- Dutta, M. J., & Elers, S. (2020). Public relations, indigeneity and colonization: Indigenous resistance as dialogic anchor. Public Relations Review, 46(1), 101852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.101852

- Firth, R. (1929). Primitive economics of the New Zealand Māori (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Gladstone, J. (2018). All my relations: An inquiry into a spirit of a Native American philosophy of business. American Indian Quarterly, 42(2), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.5250/amerindiquar.42.2.0191

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Harmsworth, G. R., & Awatere, S. (2013). Indigenous Māori knowledge and perspectives of ecosystems. In J. R. Dymond (Ed.), Ecosystem services in New Zealand: Conditions and trends (pp. 274–286). Manaaki Whenua Press.

- Harris, L. D., & Wasilewski, J. (2004). Indigeneity, an alternative worldview: Four R’s (relationship, responsibility, reciprocity, redistribution) vs. two P’s (power and profit). Sharing the journey towards conscious evolution. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 21(5), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.631

- Harrison, D. (Ed.). (2001). Tourism and the less developed world: Issues and case studies. CABI.

- Hēnare, M. (2001). Tapu, mana, mauri, hau, wairua: A Māori philosophy of vitalism and cosmos. In J. A. Grim (Ed.), Indigenous traditions and ecology (pp. 197–221). Harvard University Press.

- Hēnare, M. (2011). Lasting peace and the good life: Economic development and the 'āta noho' principle of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In V. M. H. Tawhai & K. Gray-Sharp (Eds.), Always speaking: The Treaty of Waitangi and public policy (pp. 261–276). Huia.

- Hēnare, M. (2015). Tapu, mana, mauri, hau, wairua: A Māori philosophy of vitalism and cosmos. In C. Spiller & R. Wolfgramm (Eds.), Indigenous spiritualities at work: Transforming the spirit of enterprise (pp. 77–98). Information Age Publishing.

- Hēnare, M. (2018). “Ko te hau tēnā o tō taonga…”: The words of Ranapiri on the spirit of gift exchange and economy. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 127(4), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.15286/jps.127.4.451-463

- Henry, E., & Foley, D. (2018). Indigenous research: Ontologies, axiologies, epistemologies and methodologies. In L. A. E. Booysen, R. Bendl, & J. K. Pringle (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in diversity management, equality and inclusion at work (pp. 212–227). Edward Elgar.

- Henry, E., Newth, J., & Spiller, C. (2017). Emancipatory Indigenous social innovation: Shifting power through culture and technology. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(6), 786–802. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.64

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Whyte, K. P. (2013). No high hopes for hopeful tourism: A critical comment. Annals of Tourism Research, 40, 428–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.07.005

- Horn, C., & Tahi, B. (2009). Some cultural and historical factors influencing rural Māori tourism development in New Zealand. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 4(1), 84–101.

- Hudson, M., Milne, M., Reynolds, P., Russell, K., & Smith, B. (2010). Te ara tika: Guidelines for Māori research ethics: A framework for researchers and ethics committee members. https://www.hrc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-06/Resource%20Library%20PDF%20-%20Te%20Ara%20Tika%20Guidelines%20for%20Maori%20Research%20Ethics_0.pdf

- Hutchings, J., Smith, J., Taura, Y., Harmsworth, G., & Awatere, S. (2020). Storying kaitiakitanga: Exploring Kaupapa Māori land and water food stories. MAI Journal: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, 9(3), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.20507/MAIJournal.2020.9.3.1

- Jacobsen, D. (2017). Tourism enterprises beyond the margins: The relational practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander SMEs in remote Australia. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2016.1152290

- Jones, A., & Jenkins, K. (2014). Rethinking collaboration: Working the indigene-colonizer hyphen. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies (Online ed., pp. 471–486). Sage.

- Justinian, F. (1913). The Institutes of Justinian: Translated into English by J. B. Moyle. Project Gutenberg EBook of The Institutes of Justinian, by Caesar Flavius Justinian. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/5983/5983-h/5983-h.htm

- Karena, T. (2020). Reclaiming the role of Rongo: A revolutionary and radical form of nonviolent politics. In R. Jackson, J. Llewellyn, G. Leonard, A. Gnoth, & T. Karena (Eds.), Revolutionary nonviolence: Concepts, cases and controversies (1st ed., pp. 200–223). Zed Books.

- Karetu, T. (1992). Language and protocol of the marae. In M. King (Ed.), Te ao hurihuri: Aspects of Māoritanga (pp. 28–41). Reed.

- Kawharu, I. H. (Ed.). (1989). Waitangi: Maori and Pakeha perspectives of the Treaty of Waitangi. Oxford University Press.

- Kawharu, M. (2000). Kaitiakitanga: A Maori anthropological perspective of the Maori socio-environmental ethic of resource management. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 109(4), 349–370.

- Kawharu, M. (2018). The ‘unsettledness’ of treaty claim settlements. The Round Table, 107(4), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2018.1494681

- Kelsey, J. (1990). A question of honour? Labour the Treaty. Allen & Unwin.

- Knudtson, P., & Suzuki, D. (1997). Wisdom of the elders (2nd ed.). Allen & Unwin.

- Kovach, M. (2010). Indigenous methodologies. Toronto University Press.

- Kymlicka, W. (1995). Multicultural citizenship: A liberal theory of minority rights. Clarendon Press.

- Kymlicka, W. (2002). Politics in the vernacular: Nationalism, multiculturalism and citizenship. Oxford University Press.

- Lightfoot, S. R. (2016). Global indigenous politics: A subtle revolution. Routledge.

- Litvin, S. W. (1998). Tourism: The world's peace industry? Journal of Travel Research, 37(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803700108

- Martin, W.-J., & Hazel, J.-A. (2020). A guide to vision mātauranga: Lessons from Māori voices in the New Zealand science sector. https://mcusercontent.com/afe655700044a9ad6a278bac0/files/5e6b7d88-a39e-4de2-817f-23b6748c84a2/Rauika_Ma_ngai_A_Guide_to_Vision_Ma_tauranga_FINAL.pdf

- Maxwell, K. H., Ratana, K., Davies, K. K., Taiapa, C., & Awatere, S. (2020). Navigating towards marine co-management with Indigenous communities on-board the waka-taurua. Marine Policy, 111(2020), 103722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103722

- Mead, H. M. (2017, August 23). Mātauranga Māori: te mahi, te mohio, te māramatanga – Mātauranga Māori: doing, knowing and understanding. Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi: 25 Year Anniversary 1992–2017 Lecture Series. Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi.

- Meihana, P. N. (2015). The paradox of Māori privilege: Historical constructions of Māori privilege circa 1769-1940 [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Massey University.

- Mendoza-Ramos, A., & Prideaux, B. (2018). Assessing ecotourism in an Indigenous community: Using, testing and proving the wheel of empowerment framework as a measurement tool. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(2), 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1347176

- Mika, J. P. (2014, February 4–7). Manaakitanga: Is generosity killing Māori enterprises? In P. Davidsson (Ed.), Proceedings of the Australian Centre for Entrepreneurship Research Exchange Conference (pp. 815–829). Queensland University of Technology.

- Mika, J. P. (2018). The role of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in building indigenous enterprises and economies. In S. Katene (Ed.), Conversations about indigenous rights: The UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 156–175). Massey University Press.

- Mika, J. P. (2020). Indigenous entrepreneurship: How Indigenous knowing, being and doing shapes entrepreneurial practice. In D. Deakins & J. M. Scott (Eds.), Entrepreneurship: A contemporary & global approach (pp. 1–32). Sage. https://study.sagepub.com/deakins/student-resources/e-chapter-on-indigenous-entrepreneurship

- Mika, J. P., Bishara, S., Kiwi-Scally, T., Taurau, M., & Dickson, I. (2016). Te pae tawhiti: Manawatū-Whanganui Māori economic development strategy 2016 - 2040. Te Rūnga o Ngā Wairiki-Ngāti Apa.

- Mika, J. P., Colbourne, R., & Almeida, S. (2020). Responsible management: An Indigenous perspective. In O. Laasch, R. Suddaby, E. Freeman, & D. Jamali (Eds.), Research handbook of responsible management (pp. 260–276). Edward Elgar.

- Mika, J. P., Fahey, N., & Bensemann, J. (2019). What counts as an Indigenous enterprise? Evidence from Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 13(3), 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-12-2018-0102

- Mika, J. P., Smith, G. H., Gillies, A., & Wiremu, F. (2019). Unfolding tensions within post-settlement governance and tribal economies in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 13(3), 296–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-12-2018-0104

- Mika, J. P., Warren, L., Foley, D., & Palmer, F. R. (2017). Perspectives on indigenous entrepreneurship, innovation and enterprise. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(6), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2018.4

- Mika, J. P., Warren, L., Palmer, F. R., & Jacob, N. (2018, November 13–16). Entrepreneurial ecosystem efficacy for indigenous entrepreneurs [Paper presentation]. Indigenous Futures: 8th Biennial International Indigenous Research Conference, Auckland University.

- Miller, D. (2017). Justice. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/justice/

- Moffat, M. (2016). Exploring positionality in an Aboriginal research paradigm: A unique perspective. International Journal of Technology and Inclusive Education, 5(1), 750–755. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijtie.2047.0533.2016.0096

- Morris, J. D. K., & Ruru, J. (2010). Giving voice to rivers: Legal personality as a vehicle for recognising Indigenous peoples’ relationships to water? Australian Indigenous Law Review, 14(2), 49–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26423181

- Mutu, M. (2012). Māori issues. The Contemporary Pacific, 24(1), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2012.0020

- Mutu, M. (2019). To honour the treaty, we must first settle colonisation’ (Moana Jackson 2015): the long road from colonial devastation to balance, peace and harmony. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(sup1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1669670

- Ngā Tāngata Tiaki o Whanganui. (2020). Our story: Ngā tāngata tiaki. https://www.ngatangatatiaki.co.nz/our-story/

- Office of Treaty Settlements. (2014). Ruruku whakatupua—Whanganui River deed of settlement between the Crown and Whanganui Iwi: Summary of the historical background to the Whanganui River claims of Whanganui Iwi. https://www.govt.nz/assets/Documents/OTS/Whanganui-Iwi/Whanganui-Iwi-Whanganui-River-Deed-of-Settlement-Summary-5-Aug-2014.pdf

- Office of Treaty Settlements. (2015). Healing the past, building a future: A guide to Treaty of Waitangi claims and negotiations with the Crown. https://www.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Red-Book-Healing-the-past-building-a-future.pdf

- Orange, C. (1987). The treaty of Waitangi. Allen & Unwin.

- Papakura, M. (1991). Makareti: The old-time Maori. New Women's Press.

- Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. (2019). Pristine, popular… imperilled? The environmental consequences of projected tourism growth. https://www.pce.parliament.nz/media/196983/report-pristine-popular-imperilled.pdf

- Peredo, A. M., & Anderson, R. B. (2006). Indigenous entrepreneurship research: Themes and variations. International Research in the Business Disciplines, 5, 253–273.

- Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2013). Indigenous development and the cultural captivity of entrepreneurship. Business & Society, 52(4), 592–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650309356201

- Pereiro, X. (2016). A review of Indigenous tourism in Latin America: Reflections on an anthropological study of Guna tourism (Panama). Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8–9), 1121–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1189924

- Pomerleau, W. P. (2019). Western theories of justice. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/justwest/

- Pratt, S. L. (2002). Native pragmatism: Rethinking the roots of American philosophy. Indiana University Press.

- Rangiwai, B. (2018). Atuatanga and syncretism: A view of Māori theology. Indigenous Pacific Issues, 11(1), 653–661.

- Raymond, E. M., & Hall, C. M. (2008). The development of cross-cultural (mis)understanding through volunteer tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 530–543. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost796.0

- Reid, J., & Rout, M. (2020). The implementation of ecosystem-based management in New Zealand – A Māori perspective. Marine Policy, 117, 103889–103886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103889

- Reid, J., Rout, M., & Mika, J. P. (2019). Mapping the Māori marine economy. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/tools-and-resources/mapping-the-maori-marine-economy/

- Rout, M., Reid, J., & Mika, J. (2020). Māori agribusinesses: The whakapapa network for success. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 16(3), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180120947822

- Royal, T. A. C. (Ed.). (2003). The woven universe: Selected writings of Rev Māori Marsden. Estate of Rev Māori Marsden.

- Royal, T. A. C. (2005, June 10–12). An organic arising: An interpretation of tikanga based upon the Māori creation traditions [Paper presentation]. Tikanga Rangahau Mātauranga Tuku Iho: Traditional Knowledge and Research Ethics Conference, Te Papa Tongarewa.

- Scheyvens, R. (2011). Tourism and poverty. Routledge.

- Scheyvens, R. (2018). Linking tourism to the sustainable development goals: A geographical perspective. Tourism Geographies, 20(2), 341–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1434818

- Sen, A. K. (1999). Development as freedom. Anchor Books.

- Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (1st ed.). Zed Books.