Abstract

In order to analyse the ways in which problematic ethno-national behaviour at dark events in the Western Balkans undermines the transition from conflict, to post conflict and then peaceful societies, this research employed a sociological discourse analysis to critique the role dark events play in post-conflict tourism development and peaceful coexistence. Accordingly, by combining previous analyses of dark commemorative events with a new analysis of sport events, this research explains the relationship between event tourism and 16th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) focused on peace, justice and strong institutions. This media-based analysis shows that dark commemorative and sport events share similar historical contexts, dissonant heritage and the dark leisure practices of attendees. These dark events attract tourism flows across national boundaries in the region, as well as including more widely dispersed diasporas, and international media and politicians. The prevalence of dark events in the region, which feature strongly in tourism flows, require significant attention in order to promote sustainable development. The findings of this research can be used to develop future research into the relationship between dark events and SDG16, using methods that build on this exploratory study and the new model of dark events that it provides.

Introduction

The United Nations have set out 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) intended to “end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere” (United Nations, Citation2015a). This research focuses on the relationship between event tourism and SDG16, “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions” in the post-conflict, post-Yugoslav states of the Western Balkans (; hereinafter Western Balkans). There have been several attempts to analyse the contribution that tourism makes to the SDGs, including in the areas of poverty (Folarin & Adeniyi, Citation2020), climate change (Dick-Forde et al., Citation2020), partnerships for development (Nguyen et al., Citation2019) and gender (Alarcón & Cole, Citation2019). Tourism is frequently mentioned in the preamble to the SDGs and in the detail of some of them, but it is not explicitly acknowledged in SDG16.

Figure 1. Map of the post-Yugoslav Western-Balkan states included in the analysis.

Source: d-maps (n.d.) and authors’ elaboration

Many international organisations, including the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the European Commission have identified tourism as an instrument of peace. However, in the Western Balkans, tourism involving the commemoration of conflict has contributed to increasing regional tensions (Naef & Ploner, Citation2016), notwithstanding its economic benefits. In the Western Balkans, tourism’s contribution to GDP ranges from more than 20% in the very tourism-dependent states of Croatia and Montenegro, to less than 10% in others that are less so (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2016).

Tourism offers opportunities to war-torn inland areas that are in the shadow of regionally dominant coastal destinations, and it is important to consider how tourism can contribute to SDG16 in this region. This study responds to Farmaki’s (Citation2017) call for research to consider the types of tourism that are appropriate for peace-building, the types of peace that tourism can and does contribute to and, to what extent local post-conflict situations condition these relationships. Previous research has highlighted the potential of special interest tourism to contribute to peace in general (Blanchard & Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2013) and to peace specifically in the Western Balkans (Causevic & Lynch, Citation2013; Naef & Ploner, Citation2016) but this exploratory research is the first to analyse the role of event tourism. Commemorative events in the Western Balkans with tourist audiences play divisive roles within communities, due to their links to recent conflicts, and this has been explored from a dark events perspective (Kennell et al., Citation2018). This research additionally argues that sport events can be analysed as a type of dark events, linked to the tragic past through dissonant heritage (Đorđević, Citation2019; Lalić & Biti, Citation2008; Mills, Citation2012; Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2015, Citation2017).

Previous research into the relationship between sport events and peace has frequently focused on their sporting aspects, emphasising the “universally understood language” of sport (Schulenkorf & Edwards, Citation2010, p. 102), or the role of sport organisations and federations (Peachey & Burton, 2016), and rarely considering their links to tourism. This research employs a sociological discourse analysis of regional media, using insights from dark tourism and dark leisure to analyse sport events alongside commemorative events, showing commonalities between them from a dark events perspective. This extends previous conceptualisations (Frost & Laing, Citation2013; Laing & Frost, Citation2016, Kennell et al., Citation2018) of dark events to further develop this emerging field of enquiry.

Despite the emergence of a substantial literature on tourism and peace, and the well-researched phenomenon of event tourism, the role that events can play in the development of sustainable peace has received little attention (Moufakkir & Kelly, Citation2013). In the Western Balkans, commemorative and sport events that are promoted for cross-border and international tourist consumption, and for both diasporic and non-diasporic communities, frequently feature behaviours and discourses that exceed the moral boundary-crossing and taboos attributed to dark tourism. These events are, in their extreme, accompanied by dangerous, criminal or violent acts (Bryant, Citation2011; Kennell et al., Citation2018; Stone & Sharpley, Citation2013). The aim of this research is to explore the role of these dark events in post-conflict tourism development in the Western Balkans, in the context of SDG16 and its aspirations for the peaceful coexistence of societies.

Literature review

The Western Balkans as a post-conflict destination

Although the relationship between tourism and peace has been the subject of academic and practitioner debate (Farmaki, Citation2017; Litvin, Citation1998), there is a little consensus on the directionality of this relationship. Does an increase in tourism help to promote peace, or is peace a necessary condition for the development of tourism? Advocates of the first position claim that contact between people from different cultures, societies and nations will lead to mutual understanding, helping to reduce the likelihood of conflict breaking out in the future (Durko & Petrick, Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2007). The counter-argument is that this contact is not possible unless there is a peaceful situation in a destination and that, without peace, it is not possible to develop or grow tourism (Pratt & Liu, Citation2016). From this perspective, tourism is “simply the beneficiary of peace” and not its cause (Litvin, Citation1998, p. 63).

Research into the sustainable development of tourism in post-conflict areas including Bosnia-Herzegovina (Causevic & Lynch, Citation2013), Rwanda (Maekawa et al., Citation2013) and Colombia (Mosquera-Laverde et al., Citation2019), indicates the importance of understanding local contexts. Previous research has examined the relationship between tourism and peace in the post-conflict Western Balkans (Causevic & Lynch, Citation2013; Goulding & Domic, Citation2009; Naef & Ploner, Citation2016), where processes of the normalization of ethnic relations have not been linear, especially in multi-ethnic areas where national and political elites foster divisions and antagonism. The development of tourism in these contexts, which include sites linked to recent conflicts, requires careful stakeholder engagement (McDowell, Citation2008), to ensure that these “dark” tourism offers contribute to sustainable development.

The Balkan peninsula has been the focus of many conflicts, and the twentieth century saw a series of wars that had their roots or major battles in the territories of the former state of Yugoslavia (Mujanovic, Citation2018). The First World War (WWI) began with the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand, in Sarajevo, the capital of what is now Bosnia-Herzegovina. During the Second World War (WWII), most of the territory of the Balkan peninsula was either occupied by, or aligned with, Nazi Germany (Glenny, Citation2012). Domestic quisling forces fought against “Partisans” led by communists in an anti-fascist coalition. After intense fighting for national liberation, the violence of a socialist revolution followed.

In the 1990s, the states of the former Yugoslavia were involved in the largest military conflict in Europe since the end of WWII (Šuligoj, Citation2016). This was accompanied by concentration camps and mass graves, indicating the scale of ethnic cleansing and atrocities that took place, which were brought to an end through the Dayton Peace Accords (U.S. Department of State, Citation1995). A later conflict took place between Serbia and forces of the independence struggle of Kosovo.Footnote1 The Yugoslav wars ended in 2001 after a civil war between Macedonians and Albanians in the contemporary Republic of North Macedonia. However, the core of all these historical conflicts was in the post-Yugoslav states presented in , which are the focus of this research. The relationship between tourism and the legacies of these conflicts is the focus of the following section.

Tourism and sustainable development in the Western Balkans

Despite a growing acceptance that sustainability should be central to the development of tourism, tourism development seems less sustainable than ever (Hall, Citation2019). Research in this field is dominated by a relatively narrow range of topics which frequently do not engage with the socio-political context of sustainability, which is essential for more critical scholarship to develop (Boluk et al., Citation2019). Research into tourism development in the Western Balkans often considers the “peace dividend” (Butler & Baum, Citation1999) in post-conflict areas. This mirrors research that has taken place in destinations as diverse as Northern Ireland (Leslie, Citation1996), Sri Lanka (Fernando et al., Citation2013) and the Philippines (Schiavo-Campo & Judd, Citation2005), as well as central and eastern Europe (Silvkova & Bucher, 2017).

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Western Balkan states with coastal areas were the first to see the peace dividend, using tourism for diversification following their recent conflicts (Vitic & Ringer, Citation2008). The transition from planned to market economies in these states created new conditions for economic diversification through tourism (Knežević et al., Citation2020; Mulec & Wise, Citation2013). Across all of the states of the former Yugoslavia, tourism has seen significant growth in the past two decades, notwithstanding significant problems related to its sustainable development (Bučar, Citation2017). Croatia has experienced the fastest and most significant growth in international arrivals, due to its coastal tourism offering, although niche tourism elsewhere is also expanding. For example, Serbia has experienced annual arrivals growth rates of more than ten percent since 2017 (SORS, Citation2020).

Dark tourism in post-conflict areas

Dark tourism involves “encountering spaces of death or calamity that have political or historical significance, and that continue to impact upon the living” (Stone, Citation2016, p. 23). Post-conflict destinations provide resources on which dark tourism can be built (Zhang, Citation2017). Contestation over post-conflict tourism resources, however, means that the selection of sites for development can exacerbate or create inequalities and lead to concentrations of wealth (Winter, Citation2008).

The choices of whether to develop dark tourism in post-conflict destinations are often made by public authorities, due to their politicized and sensitive nature (Light, Citation2017). Dark tourism sites are often the focus of nation-building projects, due to the role of places of conflict, death and suffering in national narratives (Nora, Citation1989; Slade, Citation2003). Where territory is disputed, or conflicting post-conflict narratives exist, tourism has been identified as problematic for peace, as its commodifies and preserves difficult heritage, including in the Western Balkans (Kamber et al., Citation2016; Pavlaković & Perak, Citation2017; Šešić Dragićević & Mijatović Rogač, Citation2014). However, the role that events play in the relationship between tourism and peace has received only limited attention in the literature (Moufakkir & Kelly, Citation2013; Skoll & Korstanje, Citation2014). Consequently, we now turn to examining the role of commemorative and sport events in post-conflict areas, to shed light on this topic.

Dark commemorative events in post-conflict areas

Commemoration establishes and fixes in the public sphere the “correct” representations of events deemed significant for particular groups (Jedlowski, Citation2002). Sites where this take place become “lieu du memoire” (Nora, Citation1984, Citation1989); a metaphor for the spatial, material, narrative and non-narrative foundations of memory. Šuligoj (Citation2016) notes, in the case of Croatia, that these are related to national memory and identity. They cannot be unproblematically introduced into dark tourism (Ashworth & Hartmann, Citation2005; Ashworth & Isaac, Citation2015).

A number of authors have used the term “dark events” to refer to commemorative events that are associated with death, disaster and suffering (Kennell et al., Citation2018; Laing & Frost, Citation2016; Šuligoj, Citation2019). Within leisure studies, the word dark has been associated with practices that involve deviance from social norms, or to denote associations with illegal or controversial subcultures (Blackshaw, Citation2018; Spracklen & Spracklen, 2012). Commemorations can also have their own dark sides (e.g. politization, manipulation, nationalism), which place them within a dark leisure framework as previously explained by Stone and Sharpley (Citation2013), Kennell et al. (Citation2018) and Bryant (Citation2011), undermining contributions that they could make to SDG16. Typically, these events are associated with war, conflict or trauma and linked to ideas such as remembrance and education, as well as to political interventions and post-conflict development (Frew & White, Citation2015; Sather-Wagstaff, Citation2011). Although they often become tourist attractions, these events should be considered on their own terms as specific types of events, with specific management and representational challenges (Frew, Citation2012; Frost & Laing, Citation2013; Kennell et al., Citation2018). Although events can contribute to peace through bringing together divided groups for dialogue (Moufakkir & Kelly, Citation2013), this can be problematic in post-conflict contexts, where the coming together of victims and perpetrators, and of communities with competing claims on justice, can lead to volatile and unpredictable situations due to “non-negotiable discrepancies” (Skoll & Korstanje, Citation2014, p. 100) between the values of participants.

Dark sport events in post conflict areas

Dark events research has not previously considered non-commemorative events. In many states, sport events are politicized occasions, involving associations between teams and political parties, or the use of sport events as platforms for political or nationalist messages (Bairner, Citation2008; Hodges & Brentin, Citation2018). Sport events also have a social function and form part of narratives about identity and belonging, mediated through the collective memory of significant matches and occasions (Healey, 1991; King, Citation2016), as well as the symbolism of specific teams, venues and individuals (Bairner, Citation2008; Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2005). Research into the relationship between sport events and peace has often taken place in the “sport for development and peace” field (Peachy & Burton, 2016). This has emphasised the positive contribution to peace from sport participation, especially by young people (Clarke et al., Citation2021) and is frequently based on projects that have explicit peace-building roles (Schulenkorf & Sugden, Citation2011). In the Western Balkan context, many sport events occur outside of the scope of this previous research. Despite its recent history of conflict, the region is well-integrated into international competition networks, in multiple sports. The Western Balkans hosts significant sport tourism events including international matches in football, tennis, handball and basketball, which attract international sports tourist audiences. Notwithstanding this apparent integration, sport events in the region with tourist audiences are frequently marked by deviant behaviour.

Sport event research in transition economies remains sparse (Hodges & Brentin, Citation2018), but the relationship between sport and the dissolution of Yugoslavia has been the topic of numerous studies, with a focus on the emergence of ethnic nationalisms in the 1990s (Đorđević, Citation2019; Lalić & Biti, Citation2008; Mills, Citation2012). In the Western Balkans, sport associations continue to be heavily politicized (Karadzoski & Siljanoska, Citation2011) and many sport events are notable for their hooligan violence involving ethno-national displays (Mills, Citation2012; Misic, 2012; Vejnović, Citation2014). Violent sport hooliganism is a common feature of football matches internationally, with some notable hooligan groups hailing from this region. However, unlike in most other destinations, hooligan violence is not confined to football matches, and is a feature of many sport events. Although a “sport for development and peace” movement exists in some areas (Giulianotti et al., Citation2017), and despite the popular perception that sport offers the potential for diffusing or releasing inter-state tension – that it is “war without the bullets” (Orwell, 1945: 10, cited in Beck, Citation2013: 73), the dominant regional discourses surrounding sport events, are of discord and nationalism, with repeated references to conflicts, such as the ongoing struggle over the recognition of Kosovo (Brentin & Tregoures, Citation2016). Wood (Citation2013) and Lalić and Biti (Citation2008) summarize some of the deviant behaviours of fans in this region, which can best be understood from the perspective of dark leisure (Spracklen, Citation2013), which is manifested in its extreme form as hooligan violence.

Decades of violence at sport events in the region, against a nationalist background and intertwined with corruption and organized crime, are harmful to post-conflict societies (Lalić & Biti, Citation2008; Mills, Citation2012). These events become sites for manipulating history, but also for the creation of new national narratives (Mills, Citation2012), that are almost always related to previous conflicts (Vejnović, Citation2014). The informal, dark leisure practices connected to recent conflicts position these events outside of previous analyses of sport heritage and sport as heritage, which have tended to concentrate on aspects of nostalgia (Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2005), cultural heritage (Hinch & Ramshaw, Citation2014), or the formal ways in which sport events contribute to commemoration (King, Citation2016). Research into sport heritage is still relatively underdeveloped (Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2015) and the emergence of a critical sport heritage field involves an increasing engagement with dissonance and intangible heritage (Pinson, Citation2017; Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2017), but has not focused on its associated tourism.

Sport events are drivers of tourism and this is one of the fastest growing sectors of the industry (Higham, Citation2018; UNWTO, Citation2020). Although sport tourism is well researched (Hinch & Higham, Citation2001; Lesjak, Citation2018), the dark sides of this type of tourism are frequently overlooked and mostly considered only as aspects of safety and security (Perić, Citation2018). Links between the dark aspects of these events and sport tourism through media reporting should not be overlooked; journalists inside and outside of the region produce a number of articles on regional sport hooliganism and violence every year.

This research extends previous conceptualisations of dark events to include these sport events in the Western Balkans, due to their specific post-conflict context, in order to consider how dark event tourism contributes to SDG16. In the following section, we set out our methodological approach to analysing dark commemorative and sport events.

Method

The media represent current events to diverse audiences (Abazi & Doja, Citation2017) and influence popular perceptions of tourist destinations (Volcic et al., Citation2014). Accordingly, the media has become an important source of information for tourism researchers (Li et al., 2018). The media also play an important role in raising awareness about the SDGs (Nishimura & Shimbun, Citation2020). Research into the relationship between the media and sustainable tourism has tended to focus on the influence of the media on the behaviours of visitors, and also on the promotion of certain destinations as more or less sustainable to visit (Pasquinelli & Trufino, 2020). However, the relationship between dark tourism, events and sustainable development has not been previously considered. This exploratory research analyses dark events, using a sociological discourse analysis (SDA) of media reports to gain deeper insights into this issue in the Western Balkans.

Discourse defines experiences and constructs shared realities. In turn, discourse is shaped by its social context (Jaworski & Pritchard, Citation2005) and analysing this enables qualitative research to engage with the complex social structures of tourism development. Discourse analysis is increasingly prevalent in the tourism literature (Qian et al., Citation2018) as a method for dealing with large amounts of textual data, including written documents and the photographs, brochures and websites that proliferate in tourism (Hannam & Knox, Citation2005; Li et al., 2018). There is a lack of consensus on what is meant by discourse analysis across different disciplines, with approaches varying from the analysis of individual conversations to the analysis of complex social systems (Jaworski & Pritchard, Citation2005).

In this research SDA was used, which relies on sociological theories and concepts and “allows us to understand social intersubjectivity because discourses contain it and because social intersubjectivity is produced through discursive practices” (Ruiz, Citation2009, p. 11). Gee (Citation2014) places this approach to discourse analysis within the umbrella categorization of critical discourse analysis, rather than with the more linguistic forms of discourse analysis that focus more descriptively on the use of language and its meaning.

For SDA, Ruiz (Citation2009) suggests three levels of analysis carried out simultaneously: a textual level (discourse characterization), a contextual level (understanding of discourse) and an interpretive level (explanation of the discourse). Li et al. (2018) employed a similar tripartite model for their analysis of media texts in tourism, spitting their analysis into textual description, process interpretation and social explanation. Gee (Citation2014) used six steps of analysis that help to analyse the significance, practices, identities, relationships, politics and connections inherent in discourse, which has been widely applied in other fields. Gee’s method, however, is more suited for the analysis of dynamic discourse with multiple participants, rather than for single authored media texts. This research employed Ruiz’s three stages of analysis, which are well aligned with Qian et al. (Citation2018) explanation of the dominant approaches taken to critical discourse in tourism research.

To collect the data for analysis, it was necessary to prepare a corpus of news media texts (Schweinsberg et al., Citation2017) to be analysed, which served as the sample for this research, following the previous practice of Wise and Mulec (Citation2012) similar study. Searches for news stories were run in Google with a focus on the Western Balkans, using search terms in the main south Slavic languages: Croatian, Serbian, Montenegrin and Bosnian, and covering the period from June 2010–June 2020. This was the first decade without armed conflict and so offered the opportunity to analyse the post-conflict period, which was accompanied by the rise of online news media (Stojarová, Citation2020). Search terms were developed by generating keywords from the literature review and background research in the region. shows a selection of keywords and results, to indicate the volume of news stories related to dark events in the period under study. Subsequently the “Customised date range” and “Sorted by relevance” Google tools (see Segev, Citation2010) were used for initial screening by headline. News reports produced by this search that did not focus solely on the Western Balkans or which covered non relevant events were excluded.

Table 1. Key words and news results.

We identified a heterogeneous list of 150 articles; all of which were then read for deeper analysis. Articles focusing on other geographical areas, duplicate articles, articles with a focus on solely the sporting aspects of an event (technical and match reports), advertisements, paid posts and similar were excluded. Selected articles were then manually segmented using a matrix, where the criteria were “Country of publisher” and ‘Conflict.” For sport events, the level of competition was also used to select articles for analysis, with only national and international levels of competition being included for analysis as these are most clearly linked to tourism. In matrix quadrants with multiple articles, a reduction was made to ensure representativeness in a purposive sample for further analysis, but to ensure that the matrix preserved its temporal, substantive, media and national dispersion. Our purposeful sample is presented in .

Table 2. Selected articles on dark commemorative events.

Following Ruiz’s (Citation2009) method, three stages of SDA were performed on the corpus of 30 news stories. The first stage involved textual analysis, aiming to give a descriptive characterisation of the discourse. To this end, headlines of the articles are presented in tables three to six, below. They create a representation of events, although they cannot convey broader narratives. The second stage of contextual analysis required engagement with the deeper meanings of each journalist’s narrative (Zandberg, Citation2010), therefore, entire articles were then brought within the analysis. Counterfactual analysis (Mahoney & Barrenechea, Citation2017) and sequence elaboration (Mahoney et al., Citation2009), were employed to deepen the contextual analysis, which also involved a critical comparison of our emerging findings with relevant literature reviewed for this research. The final, interpretive stage of analysis involved drawing connections between the discourse and its more broad social context, which in this case concerned the relationship to SDG16 and the post-conflict environment of the Western Balkans. The following discussion section presents these contextual and interpretive phases of the SDA.

Discussion

Contextual and interpretive analysis of dark commemorative events in the Western Balkans

The first set of stories to be analysed in the SDA were about dark commemorative events, shown in . Only Serbian media gave prominence to events linked to WWI. The anniversary linked to the Sarajevo assassination that sparked WWI highlighted contemporary divisions in the Western Balkans, as reports showed that Serbs did not want to take part in the main international dark event in Sarjevo (10). An alternative commemorative event organised by Serbs had a notable military presence (3). Politicians and ambassadors participated, peace and cooperation were highlighted, the heroism of Serbians was proclaimed, yet other Western Balkan nations were excluded, illustrating the difficulties of integrating these international events into sustainable tourism development for peace.

The achievement of SDG16 in the region is also undermined by events related to WWII and the later socialist revolution. Because of the legacies of both resistance and collaboration, the Western Balkans are internally and externally divided, which is reflected in their memorial practices. This division is seen in the politicization of the anniversary of the liberation of the Jasenovac concentration camp (Pavlaković & Perak, Citation2017), where three different dark events were organized. There was an official state commemoration organized by the centre-right government, a commemoration of Serbs and WWII veterans, and another for the Jewish community. The Croatian president also visited the memorial park separately (5).

A similar example of division ( previously highlighted by Šešić Dragićević & Mijatović Rogač, Citation2014; Pavlaković & Perak, Citation2017) is shown by far-right commemorations at the Jazovka pit (6), a site of post-WWII mass executions, which is a “mirror image” of anti-fascist commemorations in Brezovica forest. A journalist reports that the reconciliatory words of the Croatian president’s envoy (… “The President of the Republic under the name of unity continues Tuđman’s policy of reconciliation…it is obvious how difficult it is to build unity, …. we must therefore make additional efforts to strengthen unity on what is historically unquestionable, and that is the idea of statehood ….”) were booed. Many criticisms of the communist regime and anti-fascists were shared, such as, “There, those who call themselves anti-fascists, with all the state honours, orgy over the bones of thousands of killed Croats …”.

Also based on WWII, is a dark event at the former execution site of Donja Gradina in Bosnia, where the victims of the Croatian Ustasha regime are remembered (7). A journalist explains that it is: “…the largest execution site from WWII on the territory of the former Yugoslavia, because 700,000 victims of the Ustasha crime died in it”; it was also reported that, during this event, the leader of the Republika Srpska entity in Bosnia proclaimed about Serbian forces that “If they went outside Serbia, to some other areas, then they brought freedom to others.” This perspective resonates with memories of conflicts in the 1990s, marked by Serbian expansionism (and factual inaccuracy). Regional politicians, ambassadors, representatives of Roma and Jews, anti-fascists and the armed forces participated in the commemoration organized by governments of Serbia and the Republika Srpska entity. In the programs, which also included a religious ritual, historical facts were presented markedly differently than in (5). The nationalism of these events, and their politicization, mark them as dark events in a dark leisure and dark tourism context (Bryant, Citation2011; Kennell et al., Citation2018; Stone & Sharpley, Citation2013).

The wars in the 1990s saw the collapse of the Yugoslav idea of “brotherhood and unity,” whilst at the same time democratizing society and introducing new memorial practices (Pavlaković & Perak, Citation2017). The tragedies of Vukovar and Srebrenica, have attained the status of national myths for Croats and Bosniaks (Naef & Ploner, Citation2016), and have become the focus of commemorative events. The 20th anniversary event of the Srebrenica massacre, which attracted local and international participants, world leaders and international organizations, was overshadowed by a violent attack on the Serbian Prime Minister by angry Bosniaks (9). The Prime Minister’s entourage told the media that “It was very uncomfortable, they were throwing stones, shoes, whatever they could get,” … “They threw stones at his face and broke his glasses, shouting ‘Allahu akbar'” and “Chetnik, go home!”. indicating the interconnectedness of different 20th century conflicts through mention of WWII belligerents in the protests.

Commemorations in Vukovar, in contrast, have not yet seen similar violent acts. At the 25th anniversary, the Minister of Croatian Veterans said that … “with the arrival of almost 100,000 people today in Vukovar to pay their respects and tribute to its victims, a message was once again sent that 25 years after the crime, the courage and resistance of Vukovar remain in the collective consciousness of the Croatian people.” (8). However, expressions of anti-Serbian rhetoric have frequently occurred at such events (Goulding & Domic, Citation2009; Šuligoj, Citation2016). Similarly, the commemoration of 1995s Operation Storm in August each year has special meaning for Croatians and Serbs, but their perspectives are contradictory: Croatians celebrate victory, pride and patriotism, while for Serbs it is a day of sorrow, a symbol of exodus, and linked in the media to Ustashaism (1, 2, 4). Media reporting on these events and the participation in them by large numbers of tourists place these events in a dark tourism and dark leisure context (Kennell et al., Citation2018) that are not compatible with the achievement of SDG16 in the region, due to their role in perpetuating divisions in this post-conflict context.

One of the peculiarities of Western Balkan commemorations is that events are organized outside of the contemporary borders of the region, a sample of which are shown in . Italian Remembrance Day commemorates post-WWII executions and the “exodus” of the Italian community of the Eastern Adriatic. This takes place at the monument at Basovizza/Bazovica near Trieste, Italy (11), where the then Italian President of the European Parliament provocatively exclaimed “Long live Trieste, long live Italian Istria, long live Italian Dalmatia”. This provokes Slavs of the Eastern Adriatic through accusations of the post-WWII persecution and massacre of Italians, while 20th century Italian imperialism and Fascism are ignored (Hrobat Virloget, Citation2015). Less controversial, and generally calmer, according to regional media, are events at the Risiera di San Sabba/Rižarna, a former Nazi camp in Trieste, where anti-fascists were imprisoned and murdered (13). These events are less subject to co-option by Italian extremists, as Italians were also amongst the victims.

Table 3. Selected articles on dark commemorative events outside the region.

Events 12, 14 and 15 relate to the post-WWII massacres of fleeing enemy soldiers, enemies of the new regime, and of civilians in Austria and Slovenia (Geiger, Citation2010). A symbolic funeral event was held in Maribor (15), where Slovenian and Croatian political leaders and visitors from both stateses participated, and which took place peacefully. However, a related event in Pliberk/Bleiburg (12, 14) in Austria appears much more problematic. According to the Croatian organizers, it is a peaceful mass event, but it is under strict police control and banned Ustasha iconography and symbols have been prominent at the event (Pavlaković et al., Citation2018). In 2018, “about 11,000 people arrived on the Bleiberg field to pay their respects to the fallen civilians and soldiers of the pro-Nazi Independent State of Croatia” (14). The contemporary cross-border dark tourism dimension of these events is related to the dynamic history of the Upper Adriatic and Central Europe, which remains characterised by conflicts, disputed borders, ideological differences, dissonant heritage and dark leisure. Media discourses, which are also relevant from the SDG perspective (Nishimura & Shimbun, Citation2020), on these events clearly demonstrate that commemorative events mostly exacerbate these tensions, presenting barriers to the implementation of SDG16 (United Nations, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). This consequently indicates that weak national institutions (Goals SDG 16.6 and 16.A) do not effectively enforce the rule of law (Goals SDG16.3 and 16.B) sufficiently and thus do not effectively mitigate the above-mentioned violence (Goal SDG16.1) which is endemic to these events.

Contextual and interpretive analysis of dark sport events in the Western Balkans

firstly shows dark sport events within the sample that feature football matches, the most frequently reported sport events in the region, and the most problematic in terms of SDG16, due to the high incidence of ethno-nationalist fan violence and controversies involving domestic and international fans (Blackshaw & Crabbe, Citation2004; Bodin et al., Citation2007; Lalić & Biti, Citation2008; Mills, Citation2012; Misic, 2012; Vejnović, Citation2014; Vrcan, Citation2003; Wood, Citation2013). Aside from verbal and physical violence, the most frequently reported deviant behaviour at these events are expressions of nationalism, such as those of visiting fans at the Rijeka stadium, Croatia (19). Shouts were heard of “Miserable Rijeka, you are full of Serbs, don’t worry, Rijeka has more willows” (alluding to a slogan from the Ustasha period of “Serbs on willows”); “We Croats do not drink wine, only the blood of Chetniks from Knin”; “Kill, kill the Serb”. Nationalism is also evident in other reports, i.e. 16 − 21 and 25. They in some cases involve coalitions between different international groups of fans expressing intolerance against another state in the region. For example, in report 16, Kosovan and English fans act against the Serbs. In Pilsen “… Czech supporters sang ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ and ‘Serbia, Serbia’ in front of the hotel where Kosovo football players are accommodated. They also carried slogans with the flag of Serbia and the famous inscription ‘No surrender’.” Some were arrested for rioting (17). In report 22, Bosnian Serb and Russian fans act against Montenegrins, which escalated at the match into violence, chaos and destruction; a reporter perceived this as “the end of football as a civilized sport in Montenegro, at least for some time.”

Table 4. Selected articles on dark sport event that feature football events.

During these events, many problematic symbols are reported as displayed by fans to provoke their opponents, glorify historical events or proclaim their own identity: the double-headed eagle of Albania (16 and 25), symbols of Ustasha violence against Serbs (18), the flag of the wartime proto-state of Herzeg-Bosnia (20) and swastikas (23, 24). These symbolic manifestations of nationalism show how contemporary violence at sport events takes place in specific post-conflict contexts (Vrcan, Citation2003), involving narratives of former domestic belligerent groups such as Partisans, Chetniks and Ustashe, whose activities during WWII continue to be the source of contemporary tensions and conflicts. These violent and provocative fan behaviours are part of the “dark leisure family” (Spracklen, Citation2013).

Although football-related violence is common in many states, it also features frequently in other sport events in the Western Balkans. shows reports on water polo (26, 28), shooting (29) and basketball (27, 30). In report 30, for example, groups of Serbian fans cheered with national flags, among which was one with the inscription “Vukovar” in Cyrillic, accompanied with shouts “Kosovo is the heart of Serbia”, “Vukovar is the heart of Serbia” and “Here is Serbia,” provoking locals and the Croatian police. Other reports show international fans damaging buildings, equipment and vehicles (26), and attacking participants verbally and physically (30). A Serbian sport marksman stated (29): “When we passed seven young men in the parking area, they followed us. When we got in the car, they ran and caught up with us, they started to yell and threaten. They tried to open the doors and get us out on the road, and then started pounding on the car. Fortunately, I managed to start the car quickly, and after that they ran after us for another fifty meters.” A similar attack happened to Serbian water polo players in Split (Croatia), forcing one to jump into the sea; some locals wanted to help him, while others commented: “After all, he is a Chetnik” (28).

Table 5. Selected articles on non-football dark events.

The commemorative and sport events analysed here involve tourist activities and interactions with host communities, some of which are marred by violence outside the events (28, 29) and across the wider destination (17, 21), indicating a darker side of event tourism. Media reports reflect the dark leisure practices associated with these events, which undermine their potential to contribute to SDG16, despite their stimulation of tourism development in the region.

Further discussion and implications

Media, as an important transmitter of information on deviant behaviour (Blackshaw & Crabbe, Citation2004; Bodin et al. (Citation2007), show that both the content of these events, and their representations, are existentially dependent on narratives of past conflicts. Unlike other kinds of dissonant heritage which rely on locational authenticity, this research shows that the darkness of events does not always depend on the location where historic events occurred. Previous research into dark commemorative events has highlighted the location-specific nature of dark events (Frost & Laing, Citation2013; Kennell et al., Citation2018), and dark tourism research typically considers experiences at the locations of tragedy to be at the darker end of the spectrum (Stone, Citation2006, Citation2016). In the Western Balkans, these dark events attract international tourism flows. By considering dark sport events as a type of dark event, sustained through the mobile dark leisure practices of travelling participants, sport fans and other bad-faith actors, this research provides a new understanding of dark events, and of dark tourism that moves beyond locational authenticity.

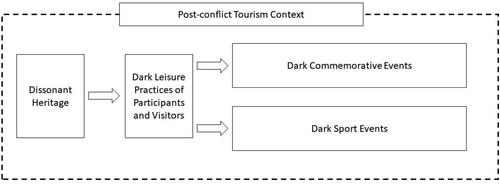

This new perspective is synthesized in . The model connects dark commemorative events with this analysis of dark sport events. Both types of events are influenced by politics, manipulation and nationalisms (Bryant, Citation2011; Kennell et al., Citation2018; Stone & Sharpley, Citation2013), significantly related to identity and belonging, (Healey, 1991; King, Citation2016; Šuligoj, Citation2016) and the symbolism of participant behaviours (Bairner, Citation2008; Pavlaković et al., Citation2018; Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2005; Vrcan, Citation2003). Moreover, visitors’ deviant behaviour at dark events are in line with the “dark leisure theory” (Spracklen, Citation2013). Commemorative and sports events in post-conflict tourism contexts differ in their form, yet share a socio-political environment and are both frequently marred by violence and other controversies.

Figure 2. Dark Commemorative and Dark Sport Events in Post-conflict Tourism Contexts, based on media analysis.

Source: authors’ elaboration.

Consequently, the two types of dark events are shown in as products of the post-conflict environment of their destinations, where the dark past has left a legacy of dissonant heritage that that is transmitted to the events through the dark leisure practices of participants and visitors. Our analysis shows that earlier conceptualisations of dark events, which focus on commemorative content, can be extended to other types of events that share the same context, but which do not intentionally make links to the dark past. By considering events in terms of their links to dissonant heritage and the dark leisure practices of attendees, in this case in a post-conflict tourism context where SDG16 is particularly pertinent, we propose the new model in as a contribution to the dark tourism and dark events literature. This can be further explored in future research and extended to include other forms of events in post-conflict tourism contexts where dark leisure practices are prevalent.

In practical terms, event organizers, destination managers and marketers should be aware that dark events transcend event management and sporting issues and can be related to many historical divisions and deviations. To integrate dark events into aspirations for SDG16, Western Balkan governments should ensure the rule of law, strong and effective institutions and, through cross-border campaigns at all levels of societies, promote peaceful coexistence and prevention of violence to achieve the goals of SDG16. Events can be catalysts for bridging community divides and can form part of sustainable tourism development in this context (Moufakkir & Kelly, Citation2013; Peachey & Burton, Citation2016), but only when event organisers can design and deliver inclusive events. Currently, in the Western Balkans, divisive state politics manifested at commemorations, and deviant fan behaviours at sport events mean that aspirations for peaceful coexistence in the region are hampered by dark events.

Conclusion

Controversial dark events can be understood from the perspective of memory studies (Nora,Citation1984, Citation1989), management challenges (Kennell et al., Citation2018) and dark leisure (Stone & Sharpley, Citation2013) as well as dark tourism (Stone, Citation2006; Stone & Sharpley, Citation2013; Šuligoj, Citation2016, Citation2017). Moreover, they can be discussed in domestic as well as international tourism contexts. Although the main non-domestic target audiences for dark commemorative events come from widespread diasporas in the region (cross-border tourism) and elsewhere (see Drnovšek Zorko, Citation2020), some of the major dark commemorative events, e.g. milestone anniversaries of the Srebrenica massacre or the Jasenovac camp, attract international elites and other visitors. More attractive to international tourists, however, are international sport events, especially various championships, attracting the international sport tourists.

In order to analyse the contribution made by dark events to SDG16 in the Western Balkans, this exploratory research provided an SDA of media reports of these events, sampled from across the region. A corpus of media reports on thirty sport and commemorative events was developed in order to develop a novel analysis, extending the scope of dark events research beyond commemorations (Kennell et al., Citation2018; Laing & Frost, Citation2016; Šuligoj, Citation2019) to include sport events which, in particular in this region, share dark characteristics linked to memory, politics and violence (Bairner, Citation2008; Brentin & Tregoures, Citation2016; Healy, Citation1991; Vejnović, Citation2014). This research shows that dark events of different types in the Western Balkans are part of a complex and seemingly permanent social system of cause-and-effect relationships, where excesses of verbal/physical violence often occur, including attacks on politicians, fans and property. The events are part of social systems characterised by nationalism and intolerance towards “others” in the region, supported and maintained by senior politicians and media. Future research into the relationship between tourism and sustainable development in post-conflict areas should also consider the influence of dark events, and this research provides a new model that can be used for this purpose.

Dark events can contribute to increasing polarization (Farmaki & Antoniou, Citation2017), and memorial tensions (Naef & Ploner, Citation2016) or open up moral concerns (Stone, Citation2009; Stone & Sharpley, Citation2013). This article demonstrates the very limited peaceful coexistence of post-conflict communities at these events, in line with claims of Adamović et al. (Citation2017) and Banovac et al. (Citation2014). Ambitions of international actors to develop “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions” (United Nations, Citation2015a, Citation2015b) as well as hopes for sustainable tourism associated with these events are “prisoners of the past.” Advocates of peace through tourism suggest that increased contact between communities will lead to peace (Durko & Petrick, Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2007), yet this research contributes new evidence that the peaceful coexistence of post-conflict societies is a pre-condition for sustainable tourism development, in line with the previous findings of Pratt and Liu (Citation2016). In the Western Balkans sustainable tourism development linked to events is more likely to be the “beneficiary of peace” and not its cause (Litvin, Citation1998, p. 63).

This study followed Farmaki’s (Citation2017) call for research into the relationships between types of tourism and peace, in post-conflict contexts. In the Western Balkans, coastal tourism dominates discussions of tourism development, and despite the emergence of special interest and urban tourism in the region, this form of tourism will continue to grow. However, a desire to spread the benefits of tourism to inland communities, and to support cross-border international tourism in the Western Balkans, means that is important to consider how other forms of tourism can contribute to sustainable development/SDG16. Tourist arrivals to the region have been increasing dramatically, and many of the dark events analysed in this research take place in destinations that have a general tourist appeal. At present, the dark nature of many commemorative and sports events in the Western Balkans will make them difficult to integrate into itineraries and products that are offered to general tourists, and destination managers and marketers should be aware of this. For these events to support sustainable tourism development in the Western Balkans, it will first be necessary for political and civil society communities to address the underlying tensions from which many of these events draw their dark character.

One of the main limitations of this research is the reliance on media reporting, which depends on journalists’ interpretations and editorial policies; in many destinations these are also heavily influenced by the authorities (Stojarová, Citation2020). Through developing a heterogeneous purposive sample of media reports for this analysis, we tried to minimise these biases. However, only Western Balkan media were considered, although dark events are also reported internationally in a way that may influence tourism to the region. We are also aware that non-controversial events are less interesting to the media and thus have often been overlooked. Although this research is limited by its focus on media reports of these events, future research into dark events could take a more ethnographic approach to analyse the experiences of participants and managers, to develop a more bottom-up understanding of the issues that have been identified through this exploratory study. In addition, further studies could use big data analytics to take a more quantitative approach to media reporting of dark events in order to generate alternative data from a more broad sample, now that some key issues for the analysis of these events have been identified.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Metod Šuligoj

Metod Šuligoj is an Associate Professor at the Department for Management in Tourism at the Faculty of tourism studies – Turistica, University of Primorska, Slovenia. His area of research relates to dark tourism, special interest tourism and hospitality management. He often blends and bridges theory from a variety of disciplines (e.g. management, sociology, geography, history) in order to explain social phenomena in tourism, especially in the Balkan and Upper Adriatic context. He utilises qualitative and quantitative methodology in delving into the complex social phenomena associated with tourism.

James Kennell

James Kennell is Deputy Head of the Department of Marketing, Events and Tourism at the University of Greenwich, where he has led programmes in tourism management for more than a decade. Over the last twenty years, he has developed and managed projects for clients in the public private and third sectors, with a focus on the relationships between tourism, culture and urban change. James' research has explored these ideas in numerous international contexts, with a concentration on the policy and political economy aspects of tourism. As well as research in tourism, James carries out research in events management, from a critical events studies perspective. He is co-author of the popular events management textbook, ‘Events Management: An Introduction’ (Routledge). James is a fellow of the Tourism Society (UK) and a regular contributor to national and international media on tourism and politics.

Notes

1 This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

References

- Abazi, E., & Doja, A. (2017). The past in the present: time and narrative of Balkan wars in media industry and international politics. Third World Quarterly, 38(4), 1012–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1191345

- Adamović, M., Gvozdanović, A. & Kovačić, (2017). Process of reconciliation in the Western Balkans and Turkey: A qualitative study. Compex d.o.o. & Institute for Social Research in Zagreb.

- Alarcón, D. M., & Cole, S. (2019). No sustainability for tourism without gender equality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 903–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1588283

- Ashworth, G., & Hartmann, R. (2005). Introduction: Managing atrocity for tourism. In G. Ashworth & R. Hartmann (Eds.), Horror and human tragedy revisited: The management of sites of atrocities for tourism (pp. 1–14). Cognizant Communication Corporation.

- Ashworth, G., & Isaac, R. K. (2015). Have we illuminated the dark? Shifting perspectives on ‘dark’ tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1075726

- Bairner, A. (2008). The cultural politics of remembrance: sport, place and memory in Belfast and Berlin. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 14(4), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630802445880

- Banovac, B., Katunarić, V. i., & Mrakovčić, M. (2014). From war to tolerance? Bottom-up and top-down approaches to (re)building interethnic ties in the areas of the former Yugoslavia. Zbornik Pravnog Fakulteta Sveučilišta u Rijeci, 35 (2), 455–483.

- Beck, P. J. (2013). ‘War minus the shooting’: George Orwell on International Sport and the Olympics. Sport in History, 33(1), 72–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460263.2012.761150

- Blackshaw, T. (2018). Some notes on the language game of dark leisure. Annals of Leisure Research, 21(4), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2017.1376220

- Blackshaw, T., & Crabbe, T. (2004). New perspectives on sport and ‘deviance’: Consumption, performativity, and social control. Routledge.

- Blanchard, L. A. & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (eds.) (2013). Peace through tourism: promoting human security through international citizenship. Routledge.

- Bodin, D., Robén, L., & Héas, S. (2007). Sport i nasilje u Europi. Knjiga trgovina.

- Boluk, K. A., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Brentin, D., & Tregoures, L. (2016). Entering through the sport’s door? Kosovo’s sport diplomatic endeavours towards international recognition. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 27(2), 360–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2016.1169799

- Bryant, C. D. (Ed.) (2011). The Routledge handbook of deviant behaviour. Routledge.

- Bučar, K. (2017). Green orientation in tourism of Western Balkan. In: Renko, S. & Pestek, A. (Eds.), Green economy in the Western Balkans. Towards a sustainable future (pp. 175–209). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Butler, R. W., & Baum, T. (1999). The tourism potential of the peace dividend. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903800106

- Causevic, S., & Lynch, P. (2013). Political (in) stability and its influence on tourism development. Tourism Management, 34, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.04.006

- Clarke, F., Jones, A., & Smith, L. (2021). Building peace through sports projects: A scoping review. Sustainability, 13(4), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042129

- Dick-Forde, E. G., Oftedal, E. M., & Bertella, G. M. (2020). Fiction or reality? Hotel leaders’ perception on climate action and sustainable business models. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 12(3), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-02-2020-0012

- D-maps (n.d.). Balkans. Retrieved from https://d-maps.com/pays.php?num_pay=181&lang=en.

- Đorđević, I. (2019). Politics on the football field. An overview of the relationship between ideology and sport in Serbia. In: M. Martynova & I. Bašić (Eds.), Prospects for Anthropological Research in South-East Europe (pp. 153–177). N. N. Miklouho-Maklay Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology Russian Academy of Sciences & Institute of Ethnography Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

- Drnovšek Zorko, Š. (2020). Cultures of risk: On generative uncertainty and intergenerational memory in post-Yugoslav migrant narratives. The Sociological Review, 68(6), 1322–1337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120928881

- Durko, A., & Petrick, J. (2016). The Nutella project: an education initiative to suggest tourism as a means to peace between the United States and Afghanistan. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8), 1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515617300

- Farmaki, A. (2017). The tourism and peace nexus. Tourism Management, 59, 528–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.012

- Farmaki, A., & Antoniou, K. (2017). Politicising dark tourism sites: Evidence from Cyprus. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 9(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-08-2016-0041

- Fernando, S., Bandara, J. S., & Smith, C. (2013). Regaining missed opportunities: The role of tourism in post-war development in Sri Lanka. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(7), 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2012.695284

- Folarin, O., & Adeniyi, O. (2020). Does tourism reduce poverty in Sub-Saharan African countries? Journal of Travel Research, 59(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518821736

- Frew, E. A. (2012). Interpretation of a sensitive heritage site: The Port Arthur Memorial Garden. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.603908

- Frew, E., & White, L. (2015). Commemorative events and national identity: Commemorating death and disaster in Australia. Event Management, 19(4), 509–524. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599515X14465748512722

- Frost, W., & Laing, J. (2013). Commemorative events: Memory, identities, conflict. Routledge.

- Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Geiger, V. (2010). Ljudski gubici Hrvatske u Drugome svjetskom ratu i u poraću koje su prouzročili Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i Partizanski odredi Jugoslavije/Jugoslavenska armija i komunistička vlast Brojidbeni pokazatelji (procjene, izračuni, popisi) Case study: Bleiburg i folksdojčeri. Časopis za Suvremenu Povijest, 42(3), 693–722.

- Glenny, M. (2012). The Balkans 1804-2012: Nationalism, War and The Great Powers. Granta.

- Goulding, C., & Domic, D. (2009). Heritage, identity and ideological manipulation: The case of Croatia. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.004

- Giulianotti, R., Collison, H., Darnell, S., & Howe, D. (2017). Contested states and the politics of sport: the case of Kosovo–division, development, and recognition. International journal of sport policy and politics, 9(1), 121–136.

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Hannam, K., & Knox, D. (2005). Discourse analysis in tourism research a critical perspective. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(2), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2005.11081470

- Healey, J. F. (1991). An exploration of the relationships between memory and sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 8(3), 213–227.

- Higham, J. (2018). Sport tourism development. Channel view publications.

- Hinch, T. D., & Higham, J. E. S. (2001). Sport tourism: A framework for research. International Journal of Tourism Research, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/1522-1970(200101/02)3:1<45::AID-JTR243>3.0.CO;2-A

- Hinch, T., & Ramshaw, G. (2014). Heritage sport tourism in Canada. Tourism Geographies, 16(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.823234

- Hodges, A., & Brentin, D. (2018). Fan protest and activism: football from below in South-Eastern. Soccer & Society, 19(3), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2017.1333674

- Hrobat Virloget, K. (2015). Breme preteklosti: Spomini na sobivanje in migracije v slovenski Istri po drugi svetovni vojni. Acta Histriae, 23(3), 531–554.

- Jaworski, A., & Pritchard, A. (Eds.). (2005). Discourse, Communication and Tourism. Channel View Publications.

- Jedlowski, P. (2002). Memoria, esperienza e modernità. Memorie e società nel XX secolo. Franco Angeli.

- Kamber, M., Karafotias, T., & Tsitoura, T. (2016). Dark heritage tourism and the Sarajevo siege. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 14(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2016.1169346

- Karadzoski, M., & Siljanoska, J. (2011, May). Political interference in the sport associations in the countries of the Western Balkans. Ovidius University Annals, Physical Education and Sport/Science, Movement and Health Series, 11(Suppl 2), 631–636.

- Kennell, J., Šuligoj, M., & Lesjak, M. (2018). Dark events: Commemoration and collective memory in the former Yugoslavia. Event Management, 22(6), 945–963. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599518X15346132863247

- Kim, S. S., Prideaux, B., & Prideaux, J. (2007). Using tourism to promote peace on the Korean Peninsula. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.09.002

- King, A. (2016). Sport, war and commemoration: Football and remembrance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. European Journal for Sport and Society, 13(3), 208–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2016.1226027

- Knežević, M. N., Hadžić, O., Nedeljković, S., & Kennell, J. (2020). Tourism entrepreneurship and industrial restructuring: GLOBE national and organisational cultural dimensions. Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic, SASA, 70(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.2298/IJGI2001015N

- Laing, J., & Frost, W. (2016). Dark tourism and dark events: A journey to positive resolution and well-being. In S. Filep, J. Laing, & M. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Positive Tourism (pp. 82–99). Routledge.

- Lalić, D., & Biti, O. (2008). Četverokut sporta, nasilja, politike i društva: Znanstveni uvid u Europi i u Hrvatskoj. Politička Misao: časopis za Politologiju, 45(3–4), 247–272.

- Lesjak, M. (2018). Velike športne prireditve in turizem: Teoretični in raziskovalni vidik merjenja vplivov velike športne prireditve. Založba Univerze na Primorskem.

- Leslie, D. (1996). Northern Ireland, tourism and peace. Tourism Management, 17(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(96)83161-X

- Li, J., Pearce, P. L., & Low, D. (2018). Media representation of digital-free tourism: A critical discourse analysis. Tourism Management, 69, 317–329.

- Light, D. (2017). Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 61, 275–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.011

- Litvin, S. W. (1998). Tourism: The world's peace industry? Journal of Travel Research, 37(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803700108

- Maekawa, M., Lanjouw, A., Rutagarama, E., & Sharp, D. (2013). May). Mountain gorilla tourism generating wealth and peace in post‐conflict Rwanda. Natural Resources Forum, 37(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12020

- Mahoney, J., & Barrenechea, R. (2017). The logic of counterfactual analysis in case-study explanation. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(1), 306–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12340

- Mahoney, J., Kimball, E., & Koivu, K. L. (2009). The logic of historical explanation in the social sciences. Comparative Political Studies, 42(1), 114–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414008325433

- McDowell, S. (2008). Selling conflict heritage through tourism in peacetime Northern Ireland: transforming conflict or exacerbating difference? International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(5), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250802284859

- Mills, R. (2012). It all ended in an unsporting way’: Serbian football and the disintegration of Yugoslavia, 1989–2006. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 26(9), 1187–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360902941829

- Mosquera-Laverde, W. E., Vásquez-Bernal, O. A., Gomez-E, C. P. (2019). Eco-touristic foresight in the Colombian post-conflict for the sustainability of the tourist service with emphasis on ecological marketing. Buenaventura Case. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Pilsen, Czech Republic, July 23-26, 2019

- Moufakkir, O., & Kelly, I. (2013). Peace through tourism A sustainable development role for Events. In T. Pernecky & M. Lück (Eds.), Events, society and sustainability: Critical and contemporary approaches (pp. 130–150). Routledge.

- Mujanovic, J. (2018). Hunger and Fury: The Crisis of Democracy in the Balkans. Hurst.

- Mulec, I., & Wise, N. (2013). Indicating the competitiveness of Serbia's Vojvodina Region as an emerging tourism destination. Tourism Management Perspectives, 8, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2013.07.001

- Naef, P., & Ploner, J. (2016). Tourism, conflict and contested heritage in former Yugoslavia. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 14(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2016.1180802

- Nguyen, T. Q. T., Young, T., Johnson, P., & Wearing, S. (2019). Conceptualising networks in sustainable tourism development. Tourism Management Perspectives, 32, 100575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100575

- Nishimura, Y., Shimbun, A. (2020). How the media can be a meaningful stakeholder in the quest to meet the SDGs. Retrieved from World Economic Forum website: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/sdgs-sustainable-development-news-media-coverage/

- Nora, P. (1989). Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations, 26, 7–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928520

- Nora, P. (1984). Entre. Mémoire et Histoire. La problématique des lieux. Université Lumière Lyon 2. https://perso.univ-lyon2.fr/∼jkempf/LDM_intro.pdf

- Pavlaković, V., Brentin, D., & Pauković, D. (2018). The controversial commemoration: Transnational approaches to remembering Bleiburg. Politička Misao, 55(2), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.20901/pm.55.2.01

- Pavlaković, V., & Perak, B. (2017). How does this monument make you feel?: Measuring emotional responses to war memorials in Croatia. In T. S. Andersen & B. Törnquist-Plewa (Eds.), The Twentieth Century in European Memory (pp. 268–304). Brill.

- Peachey, J. W. & Burton, L. (2016) Servant Leadership in Sport for Development and Peace: A Way Forward. Quest, 69(1), 125–139, https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1165123

- Perić, M. (2018). Estimating the perceived socio-economic impacts of hosting large-scale sport tourism events. Social Sciences, 7(10), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100176

- Pinson, J. (2017). Heritage sporting events: Theoretical development and configurations. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 21(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2016.1263578

- Pratt, S., & Liu, A. (2016). Does tourism really lead to peace? A global view. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2035

- Qian, J., Wei, J., & Law, R. (2018). Review of critical discourse analysis in tourism studies. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(4), 526–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2202

- Ramshaw, G., & Gammon, S. (2005). More than just nostalgia? Exploring the heritage/sport tourism nexus. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 10(4), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080600805416

- Ramshaw, G., & Gammon, S. (2015). Heritage and sport. In E. Waterton & S. Watson (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of contemporary heritage research (pp. 248–260). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ramshaw, G., & Gammon, S. J. (2017). Towards a critical sport heritage: Implications for sport tourism. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 21(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2016.1262275

- Ruiz, J. R. (2009). Sociological discourse analysis: Methods and logic. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-10.2.1298

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. (2011). Heritage that hurts: Tourists in the memoryscapes of September 11. Left Coast Press.

- Schiavo-Campo, S., & Judd, M. P. (2005). The Mindanao conflict in the Philippines: Roots, costs, and potential peace dividend (Vol. 24). Conflict Prevention & Reconstruction, Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, World Bank.

- Schulenkorf, N., & Edwards, D. (2010). The role of sport events in peace tourism. In O. Mouffakir & I. Kelly (Eds.), Tourism, progress and peace (pp. 99–117). CABI.

- Schulenkorf, N., & Sugden, J. (2011). Sport for development and peace in divided societies: Cooperating for inter-community empowerment in Israel. European Journal for Sport and Society, 8(4), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2011.11687881

- Schweinsberg, S., Darcy, S., & Cheng, M. (2017). The agenda setting power of news media in framing the future role of tourism in protected areas. Tourism Management, 62, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.011

- Segev, E. (2010). Google and the Digital Divide. The Bias of Online Knowledge. Chandos Publishing.

- Šešić Dragićević, M., & Mijatović Rogač, L. (2014). Balkan dissonant heritage narratives (and their attractiveness) for tourism. American Journal of Tourism Management, 3(1B), 10–19.

- Slivková, S., & Bucher, S. (2017). DARK TOURISM AND ITS REFLECTION IN POST-CONFLICT DESTINATIONS OF SLOVAKIA AND CROATIA. 19(1), 22–34.

- Skoll, G. R., & Korstanje, M. E. (2014). Terrorism, homeland safety and event management. International Journal of Hospitality and Event Management, 1(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHEM.2014.062869

- Slade, P. (2003). Gallipoli Thanatourism: The meaning of ANZAC. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(4), 779–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00025-2

- SORS. (2020). Tourism Statistics. Online. Retrieved from https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-us/oblasti/ugostiteljstvo-i-turizam/turizam/16.01.2021

- Spracklen, K. & Spracklen, B. (2012). “Pagans and Satan and Goths, Oh My: Dark Leisure as Communicative Agency and Communal Identity on the Fringes of the Modern Goth Scene.” World Leisure Journal, 54 (4), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2012.720585

- Spracklen, K. (2013). Leisure, sports & society. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stojarová, V. (2020). Media in the Western Balkans: Who controls the past controls the future. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 20(1), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2020.1702620

- Stone, P. R. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Turizam: Međunarodni Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis, 54(2), 145–160.

- Stone, P. R. (2009). Dark tourism: Morality and new moral spaces. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism (pp. 56–72). Channel View Publications.

- Stone, P. R. (2016). Enlightening the ‘dark’ in dark tourism. Interpretation Journal, 21(2), 22–24.

- Stone, P. R., & Sharpley, R. (2013). Deviance, Dark Tourism and ‘Dark Leisure’: Towards a (re)configuration of morality and the taboo in secular society. In S. Elkington & S. Gammon (Eds.), Contemporary Perspectives in Leisure: Meanings, Motives and Lifelong Learning (pp. 54–64). Routledge.

- Šuligoj, M. (2016). Memories of war and warfare tourism in Croatia. Annales. Series Historia et Sociologia, 26(2), 259–270.

- Šuligoj, M. (2017). Warfare tourism: an opportunity for Croatia? Economic research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 30(1), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2017.1305800

- Šuligoj, M. (2019). Dark events of the Istrian countryside: An electronic media perspective. Academica Turistica, 12(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.26493/2335-4194.12.121-132

- U.S. Department of State. (1995). Dayton Accords. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/or/dayton/.

- United Nations. (2015a). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Preamble and Declaration. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations. (2015b). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations.

- UNWTO. (2020). Sport Tourism. Retrieved from https://www.unwto.org/sport-tourism.

- Vejnović, D. (2014). Nasilje i sport. Uzroci, posljedice i strategije prevazilaženja. Evropski defendologija centar za naučna, politička, ekonomska, socijalna, bezbjednosna, sociološka i kriminološka istraživanja.

- Vitic, A., & Ringer, G. (2008). Branding post-conflict destinations: Recreating Montenegro after the disintegration of Yugoslavia. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2–4), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n02_10

- Volcic, Z., Erjavec, K., & Peak, M. (2014). Branding post-war Sarajevo: Journalism, memories, and dark tourism. Journalism Studies, 15(6), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.837255

- Vrcan, S. (2003). Nogomet – politika – nasilje. Jesenski i Turk.

- Winter, T. (2008). Post‐conflict heritage and tourism in Cambodia: The burden of Angkor. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(6), 524–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250802503274

- Wise, N. A., & Mulec, I. (2012). Headlining Dubrovnik’s tourism image: Transitioning representations/narratives of war and heritage preservation 1991–2010. Tourism Recreation Research, 37(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2012.11081688

- Wood, S. (2013). Football after Yugoslavia: Conflict, reconciliation and the regional football league debate. Sport in Society, 16(8), 1077–1090. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.801225

- Zandberg, E. (2010). The right to tell the (right) story: Journalism, authority and memory. Media, Culture & Society, 32(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443709350095

- Zhang, J. J. (2017). Rethinking ‘heritage’ in post-conflict tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 66(C), 194–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.06.005