Abstract

Research on animal ethics in tourism has gained traction but posthumanist approaches to wildlife (eco)tourism remain sparse. There has never been a more urgent need to redress this paucity in theory and practice. More than 60% of the world’s wildlife has died-off in the last 50 years, 100 million-plus nonhuman animals are used for entertainment in wildlife tourist attractions (WTAs), more than one billion “wildlife” live in captivity, and some scholars argue that earth has entered its sixth mass extinction event known as the Anthropocene. This paper presents a posthumanist multispecies livelihoods framework (MLF) based on an applied ethnographic study of 47 wildlife ecotourism (WE) operators and wildlife researchers in protected area WTAs across four countries. Like any framework, it is a snapshot of the authors’ thinking at a particular time and must be improved upon. The MLF does not purport to solve the negative treatment of nonhumans that can occur in tourism settings, but rather responds to calls in the tourism literature to acknowledge our effects on other species and advocates for equitable human-nonhuman livelihoods. This paper argues that we have a moral responsibility to nonhumans and the environment, and the authors hope to generate reflexive discourse concerning the role tourism can play in redressing the ecological crisis and improving the treatment of individual nonhumans to foster wildlife-human coexistence.

Introduction

Wildlife tourism has been championed by some for its potential to conserve species (Belicia & Islam, Citation2018), protect ecosystems (Lamb, Citation2019), and provide sustainable human livelihoods (Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2018). Critics of this type of tourism suggest that commodifying wildlife is overtly anthropocentric and centers on the positive economic returns for humans while ignoring the rights, agency, and welfare of nonhuman animals (Belicia & Islam, Citation2018; Burns, Citation2017; Cohen, Citation2019; Thomsen et al., Citation2021a). This is fundamentally evident in the application of the term wildlife tourism, as it broadly encompasses all tourism related to wildlife, including consumptive practices (e.g. hunting and fishing) that result in a nonhuman animal’s death (Burns, Citation2017). Belicia and Islam (Citation2018) criticize “market environmentalism” to call for a decommodified approach to wildlife tourism that values nonhumans beyond their economic worth to humans. Burns (Citation2017) argues that “the advent of the Anthropocene provides an opportunity for humans to accept responsibility for how they engage with animals in tourism settings and ethically reassess this engagement” (p.213); the Anthropocene is theorized to be the sixth-mass extinction event in the planet’s history, caused by humans exceeding planetary thresholds (Steffen et al., Citation2011).

Biodiversity conservation is critical to ameliorating the negative effects brought on by the Anthropocene, as more than 60% of the world’s wildlife has died-off in the last half-century (Grooten & Almond, Citation2018). Stone and Nyaupane (Citation2018) state that “wildlife-based community tourism within and around protected areas is seen as a tool to link biodiversity conservation and community livelihoods improvement”, and argue that current frameworks do not adequately consider the “complex and dynamic relationships that exist among conservation, tourism and development” (p. 307). Though in the context of protected areas, they present a systems-thinking approach, “communities capital framework” (CCF), that considers the social, human, natural, financial, physical/built, cultural, and political capitals within communities.

However, existing frameworks and discourse about biodiversity conservation, tourism, development, and nonhuman species remain anthropocentric. Humans often speak of nonhuman animal species in the abstract and do not focus on the rights, agency, and welfare of individual nonhumans (Thomsen et al., Citation2021a; Thomsen, in press). Cohen (Citation2019) states that posthumanism is essentially absent from tourism scholarship. Posthumanism is a postmodern philosophical line of inquiry that attempts to subvert human-exceptionalism and considers the ethics of speaking for and about nonhuman animals, without their consent. In this paper, we respond to Cohen’s call for a posthumanism approach to tourism to eliminate the “animal-human” divide, by contributing a posthumanist, subaltern, multispecies livelihoods framework (see below). Subaltern refers to marginalized groups (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities, women, indigenous, nonhuman animals) that are subservient to another group in terms of power (Mitchell, Citation2002; Spivak, Citation1988; Thomsen et al., Citation2021a).

Literature review

Multispecies livelihoods

Manfredo et al. (Citation2016) state that “values are arguably at the root of our ability to attain global environmental sustainability - a pursuit inextricably linked to conservation of Earth’s biological diversity” (p.288), and suggest that a mutualism approach that works within current values systems may positively alter human behavior to better favor wildlife. Manfredo et al. (Citation2020) suggest that economic modernization in developed countries may explain the shift from long-held dominance frameworks that reinforced humankind’s power over “Nature” (Descola & Pálsson, Citation1996), to a mutualism orientation that “consider wildlife as part of their broader social community, deserving of rights and caring treatment” (p. 3). This entrenched “dominance” (utilitarian) worldview often suggests that humans have the moral and ethical right to determine the welfare, rights, and status of nonhuman animals (Peterson & Nelson, Citation2017; Vantassel, Citation2008). Wildlife-human conflict persists through asymmetrical power relations where special interest groups possess an inequitable stronghold over other species through policy (Fox & Bekoff, Citation2011; Thomsen et al., 2020b), management (Nie, Citation2001), security (Lynn, Citation2010), and fear (Lappalainen, Citation2019). Multispecies ethnography deconstructs power relations between species and stakeholders to theorize how animal welfare may be foregrounded in nonhuman-human animal relationships (Faier & Rofel, Citation2014; Kirksey & Helmreich, Citation2010).

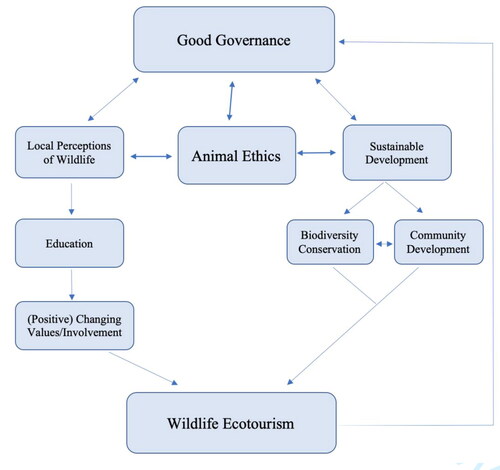

Hyvärinen (Citation2019) captures this change in their study on beekeeping to define multispecies livelihoods as “the diverse and particular practices of securing the necessities of life through sharing lifeworlds with human and non-human others” (p. 366). We contend that humans have a moral responsibility to care for the environment and the wildlife that inhabit it, so Hyvärinen’s definition should be expanded to account for “securing the necessities of life” without causing undue harm toward another individual or species. We define multispecies livelihoods as the right for human and nonhuman animal species to not only exist but to secure the necessities of life in a manner that does not infringe on another species’ right to live, except for sustenance hunting or legitimate safety concerns to foster optimal conditions for wildlife-human coexistence. We visualize our framework in below.

The multispecies livelihoods framework is a posthumanist attempt to emphasize animal ethics - human and nonhuman - for wildlife ecotourism in theory and practice. The framework considers animal ethics as a conduit to balance human and nonhuman livelihoods through sustainable development, biodiversity conservation, and community development on the right side, with local perceptions of wildlife (human and industry), education, and (positive) changing values/involvement on the left side. Wildlife ecotourism (WE) operators are uniquely positioned to engage with local, often rural, communities in a plurality of pathways, which can inform good governance and serve as a feedback loop. For example, providing opportunities for different age groups and rural versus urban demographics to engage in discourse about wildlife-human encounters. When established in a thoughtful and reflexive manner, (community-based) wildlife ecotourism can serve as a dynamic mechanism for local community empowerment (Scheyvens, Citation1999).

Good governance capstones the framework as it also presents a fluid context where wildlife-human relations govern power relations but can be reflexively altered when humans advocate for wildlife protection. Fennell and Sheppard (2021) state that “good governance in its application to animals, therefore, is a function of competing interests between justice and commerce and entertainment” (p. 328). We heed Fletcher’s (Citation2019) cautionary warning to not view (wildlife) ecotourism’s relationship to the Anthropocene as a capitalist “fix” that exploits the “end of nature”, by arguing for nonhuman animals to be treated as equal stakeholders in tourism governance (Sheppard & Fennell, Citation2019). The multispecies livelihoods framework maintains elements of neocapitalist practices out of pragmatic necessities, but challenges humans to cease exploitation of the environment and engage in sustainable business practices that result in enhanced animal welfare, rights, and agency, moving past “market environmentalism” (Belicia & Islam, Citation2018). We purposely foreground “wildlife-human” throughout, in an attempt to equitably represent nonhuman animals in this exercise of power that “speaks” for and about wildlife. The following sections in the literature review correlate to each topic from the multispecies livelihoods framework to provide theoretical underpinnings that cut across various disciplines, but center on their relation to tourism.

Wildlife ecotourism

Wildlife tourism is a broad term that includes a range of nature-based activities that aim to directly engage with non-domesticated, nonhuman animals in consumptive (e.g. fishing, hunting) and non-consumptive ways (e.g. sightseeing) (Burns, Citation2017). Ecotourism ideally takes a pro-environmental and sustainable lens that advocates respect for ecosystems and culture through environmental education and non-consumptive use to foster ecological conservation and sustainable development (see Fennell & Weaver, 2005; Bansal & Kumar, Citation2013; Clark et al., Citation2019; Gurung & Seeland, Citation2008; Stronza, Citation2001). Wildlife ecotourism has largely been viewed as a vehicle to secure economic benefits and increase human livelihoods while intending to conserve wildlife and their environment (Balmford et al., Citation2009; Higginbottom, Citation2004; Karanth et al., Citation2012).

However, a critical exploration into WE literature also unveils negative effects on nonhuman animals’ conservation and welfare that extend beyond place-based community development to that of powerful corporate interests that may exploit natural capital (Castree, Citation2008; Duffy, Citation2008). Moorhouse et al. (Citation2015) analyzed 24 wildlife tourism attractions (WTAs) to show the collective negative effect on the welfare status of 230,000–550,000 individual nonhuman animals per year; hundreds of thousands more tourist interactions attributed to the reduced conservation status of wildlife populations, and 2–4 million of the 3.6–6 million tourists inadvertently supported wildlife exploitation. Green and Giese (Citation2004) focus on the negative effects of tourism on wildlife concerning issues of increased stimuli, behavioral changes related to survival or reproductive stress, as well as direct and indirect killing or injury of nonhuman animals attributed to tourism developments.

Cantor and Knuth (Citation2019) present the limitations of “postnatural” environmentalism through their examination of the Salton Sea, questioning the efficacy of the green capitalist movement (manipulation of environmental framings to support accumulation projects) and its misuse of an entire geographic region that suffers from regulatory freedoms, relativism, degradation, and neoliberal austerity. Gluszek et al. (Citation2020) identify 15 emerging trends that reinforce the illegal wildlife trade and threaten vulnerable ecosystems, national security in Mesoamerica, and sustainable development within the region (also see Nellemann et al., Citation2014). While certain benefits remain, Moorhouse et al. (Citation2017) challenge the extent to which WE offers support to conservation, citing ubiquitous negative effects on wildlife, while also suggesting wildlife tourists are “boundedly ethical in failing to recognize the dimensions of their own decisions”, exacerbating their blind spots (p.509).

Sustainable development

Global sustainable development initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) endeavor to address economic, social, cultural, and environmental conditions while enhancing the quality of life for humans and nonhumans alike (Copeland, Citation2020; Thomsen & Thomsen, Citation2020). Tourism is a controversial mode of sustainable development (see Sharpley, Citation2020) as it can cause environmental degradation and, at times, reinforces anthropocentric power relations over nonhuman species. However, wildlife ecotourism (WE) may be uniquely positioned to bolster nonhumans’ rights and welfare and work within the confines of the neoliberal paradigm to catalyze a multispecies livelihoods framework (Copeland, Citation2021; Thomsen, in press; Thomsen & Thomsen, Citation2020).

Sharpley (Citation2020) draws upon debates of “sustainable tourism” and its proverbial efforts of “sustaining tourism as a specific activity”, decoupling it from projects that are “sustainable tourism development” and their broader accomplishments in a bottom-up approach to development. Ideally, sustainable development alters the social constructs between practices, social relations, and sociotechnical systems (Bramwell et al., Citation2017), with the fundamental purpose of promoting community participation (Zadeh & Ahmad, Citation2010) and capacity building (Gilchrist & Taylor, Citation2016). Thomsen et al. (Citation2020a) apply a social entrepreneurship lens to sustainable development. They present a transcultural development approach that advocates for the inclusion and preservation of cultural norms and rights of receiving cultures within and among the development process while critiquing institutions that become myopic in focus. Social entrepreneurship takes a triple bottom line approach to sustainable development as it balances economic profitability, environmental conservation, and social justice issues (Bohlmann et al., Citation2018; Thomsen et al., Citation2018; Citation2019; Citation2021a; 2021b). Extending the transcultural development approach to more equitably consider nonhumans’ rights, welfare, and agency could aid in the effort to reduce anthropocentric sustainable development and promote an equitable multispecies livelihoods framework.

Biodiversity conservation

“Biodiversity is the variability among living organisms; within species, between species, and of ecosystems” ( Copeland, Citation2020, p.2; see Gaston & Spicer, Citation2013 ). On a global scale, biodiversity is increasingly threatened by anthropocentric economic systems of production that place greater stressors on ecosystem functions. One such threat to resilient ecosystems is biodiversity fragmentation-risk or conditions that prevent viable unification of natural areas that include limited spatially protected areas (Chapin III et al., Citation2009), urban sprawl (Radeloff et al., Citation2005), wildlife-human conflict (Hill, Citation2015), large-scale industrialization projects (Harte et al., Citation2010), and human-human conflict (Redpath et al., Citation2015). Debates surrounding agricultural production and their detrimental effects on wildlife and ecosystems consider whether land for nature and land for production should be separate - land sparing, or integrated - land sharing (Grau et al., Citation2013; Kremen, Citation2015). Tscharntke et al. (Citation2012) argue that smallholder farming is currently the “backbone” to agricultural systems within the developing world, highlighting the importance of wildlife-friendly agroecological practices. Grass et al. (Citation2019) transition to multifunctional landscapes, arguing that together these practices have the potential to connect habitats for biodiversity conservation.

Pettersson et al. (2020) utilize an Asset Framework (AF) focused on human and nonhuman values related to ecotourism in Protected Areas (PAs) to evaluate shifting egalitarian perceptions of land-use and utility for integrated “co”- management strategies and community resilience. Naidoo et al. (Citation2019) evaluates environmental and socioeconomic conditions that compare the affects of PAs on human wellbeing to conclude that households near PAs with ecotourism have higher wealth levels and a lower likelihood of poverty than those that do not. However, Green et al. (Citation2018) caution that the opportunity cost for biodiversity conservation disproportionately affects local populations, affirming the need for community-based approaches.

Good governance

Rastegar (Citation2020) claims that Western, developed country politicians and scholars dominate tourism policy and practice in developing countries. These policies often favor social justice (human livelihoods) over ecological justice (nonhumans’ rights, agency, and welfare and the ecosystems they inhabit), leading to lax government enforcement of protected areas and “increased poaching and habitat destruction” (p.2). Sheppard and Fennell (Citation2019) reviewed 123 tourism policies from 73 countries and reported mixed results concerning animal welfare. They found that policies evolved from predominantly economic-based outcomes to encompass “social and natural environments, including the concern for animal welfare”, but suggest that “until animals are considered a stakeholder in the tourism industry, their rights to exist and thrive will be considered only as it relates to their ability to enhance the attractiveness of and economic potential of a destination” (p.134). Sheppard and Fennell’s assessment to equally treat nonhumans as stakeholders aligns with the multispecies livelihoods framework to center on animal ethics as its core component.

(Environmental) education, attitudes, & perceptions of wildlife

Ballantyne et al. (Citation2007) synthesize zoo and aquarium research of non-captive models of wildlife tourism, finding that they provide an opportunity for “conservation learning” through a variety of methods that include: animal observation, close wildlife encounters, emotional connections with visitors, links between conservation to quotidian activities, and incentives for human behavioral change. There are mixed results with trying to directly change human environmental behavior, but studies suggest that wildlife ecotourism may indirectly influence a shift toward pro-environmental perceptions and decisions (Ballantyne et al., Citation2011; Clark et al., Citation2019; Curtin & Kragh, Citation2014). In their study on wildlife ecotourism in Manaus, Brazil, D’Cruze et al. (Citation2017) call for “a wider and more holistic approach that includes education and human behaviour change focused initiatives targeting both local communities, operators and in particular, tourists is required to prevent potential negative impacts from inevitable ecotourism expansion in the Amazon”, in response to a lack of legal enforcement concerning illegal wildlife “photo-prop” tourism (p. 13).

Reynolds and Braithwaite (Citation2001) proffer a conceptual framework for WE, suggesting a “conflicting but necessary” trade-off between conservation, animal welfare, visitor satisfaction, and profitability. To further remedy this issue, a combination of ecological and animal welfare education may significantly influence tourists’ perceptions to seek out pro-wildlife experiences (Moorhouse et al., Citation2017). When utilizing local knowledge and adapting to community needs (Sekhar, 2003; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2017), implementing science-based wildlife-human coexistence measures for management (Carter et al., Citation2012; Haidir et al., Citation2020), and effectively planning to broaden conservation protections (Lopez Gutierrez et al., 2019), WE may serve as a positive pathway for wildlife-human coexistence so long as animal ethics are foregrounded.

Animal ethics

More than 100 million animals are used for entertainment and another billion “wildlife” exist in captivity worldwide (Fennell, Citation2013), yet research on animal ethics in tourism is largely absent in theory and practice. Fennell states:

What is important for the tourism industry, and this includes scholars and practitioners, is the immediate need to initiate programmes of research for the purpose of taking more seriously the welfare needs of animals used in tourism. At present scholarship is thin at best and this scarcity exists despite the scale of the problem, and in view of what many other disciplines have done to date (2013, p.336).

Moorhouse et al. (Citation2017) warn that while tourism revenue can “promote local livelihoods and tourist education, enact conservation, and improve animal welfare”, these benefits can only be achieved when ethical actions are in the forefront, and that “in the absence of global regulatory authorities, tourist revenue has become the ultimate arbiter of what constitutes acceptable use of animals in WTAs” (p.505). Animal welfare has since increased in tourism discourse. Winter (Citation2020) reviewed 74 articles on animal ethics, welfare, and tourism and states that “what is now needed above all, is the application of specific ethical principles to tourism situations involving animals, and research about unique human-animal relationships that exist within touristic encounters” (p.18). Filion et al. (Citation1994) estimate that between 20–40% of all international tourism includes wildlife experiences, demonstrating the importance of focusing on our moral obligations to nonhumans. The multispecies livelihoods framework centers on animal ethics to decommodify wildlife and equitably consider wildlife-human rights, agency, and welfare in wildlife ecotourism.

Methodology

Multispecies ethnography

Multispecies ethnography is a relatively new paradigm within the social sciences that considers mutual dependencies, influences, and hybrid ontologies involving human and nonhuman actors (see Haraway, Citation2008). Building on (post)colonial studies, such work focuses on “middle grounds” (Kohn, Citation2013) or “naturalcultural borderlands” (Kirksey & Helmreich, Citation2010), where lines between nature and culture are blurred to elucidate how human-nonhuman worlds mutually emerge through interspecies relationships (Parathian et al., Citation2018; Thomsen et al., 2020b). This study applied ethnographic methods, (e.g., semi-structured interviews, archival research, and participant observation), grounded in the field of anthropology that follows an inductive, emic approach, and qualitative thematic analysis to theorize the multispecies livelihoods framework (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). This research was driven by three primary research questions: (1) how can nonhumans animals’ rights, welfare, and agency be foregrounded in wildlife (eco)tourism to foster wildlife-human coexistence?, and (2) how can wildlife (eco)tourism be decommodified to equitably consider nonhumans’ interests and human livelihoods?, and (3) to what effect does wildlife conservation education, policy, and governance have on human stakeholders’ perceptions of nonhumans?

Data collection

The authors are part of a U.S. university research team that trains students to conduct applied international research on wildlife-human conflict and coexistence in a combination of domestic and international settings. The team consisted of 12 students, including 10 undergraduates and two graduate students, and two academic staff. One of the graduate students was from a different regional university but had participated in two previous research trips and now served as a co-leader of the study. Nine of the undergraduates were female with one male, ranging from 21-to-56 years of age. The two graduate students were male, and were 21 and 26 years old. The two instructors were 32 and 34 years old, and one was male and the other female. presents an overview of the data collection methods used in this study and the information gathered.

Table 1. Overview of data collection.

Data procedures

Site selection was based on instructors’ networks and familiarity with ecotourism operators, previous research, and the significance of ecotourism in each country. In total, 12 locations were selected across four countries: Italy, Costa Rica, U.S., and Scotland (UK). The organizations are described in .

Table 2. Overview of Wildlife Ecotourism Organizations.

Fieldwork was evenly split between in person and online data collection via electronic communications, e.g., Zoom, to complete semi-structured interviews, archival data analysis, and participant observation over nine months (Hanna, Citation2012). The two instructors collected data in person at five separate wolf (Canis lupus) sanctuaries and Yellowstone National Park in the U.S. Forty-one interviews were conducted with 47 (22 male and 25 female) participants from eight sanctuaries and four excursion models. Interviewees were identified for their expertise on wildlife ecotourism, and a “snowball sampling” technique was engaged with to facilitate data collection (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). Three participants were from Scotland, 32 were from the U.S., three were from Italy, and nine were from Costa Rica. Interlocutors’ ages ranged from 22 to 62, and 43 of the 47 had at least some college education. Interviews were conducted predominantly in English; however, a few exchanges occurred in Spanish and led by the instructors. All participants were leaders in their respective organizations and included high-level positions such as executive director and founder, as well as mid-level leadership positions including program coordinators, staff veterinarians, and volunteer coordinators. Interviews lasted between 50 and 90 minutes. Semi-structured interview questions focused on the organizations’ mission and goals, the extent of human-human and wildlife-human conflict observed, challenges faced, human perceptions of wildlife, relationships with customers, the treatment of animals in their care or effected by their operations, interactions with governmental agencies, and opponents to wildlife rights and welfare.

Data analysis

Responses were digitally recorded, transcribed for accuracy, and coded. A thematic analysis was conducted to identify commonalities between interlocutors’ responses and compared against archival data (e.g. internal documents provided by interviewees) and participant observations (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Thomsen et al., Citation2018). Participants’ names were anonymized, and each respondent was given a corresponding number. Interview transcriptions and thematic analysis were completed in collaboration with the first four authors, while the limited participation observation was conducted by the two instructors. Participant observation provided context to visualize the WE organizations’ operations and animal welfare practices. Perspectives were contrasted against archival research to proffer insight as to how potentially competing perspectives may be altered by WE, and affect human livelihoods, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife welfare. Archived research documents included internal documents as well as external research papers shared with the team by WE operators.

Data saturation was reached prior to the completion of the study as no new themes emerged and although interlocutors hailed from different countries, interlocutors shared relatively homogenous expertise in wildlife ecotourism. Guest et al. (Citation2006) study of data saturation showed that while some researchers suggest that 35 is the minimum number of interviews needed for saturation and that each study requires contextual consideration, “for most research enterprises, however, in which the aim is to understand common perceptions and experiences among a group of relatively homogeneous individuals, twelve interviews should suffice” (p. 79).

Limitations to this study primarily included the U.S. dominated sample size for logistical necessity, compared to the limited scope of WE operators from each non-U.S. country. Further inquiry should include more non-English speaking organizations, as well as WE operators from non-Western or non- ‘developed’ countries. This exploratory study can nonetheless be used as a basis to test the multispecies livelihoods framework; the Italian and one of the Costa Rican organizations committed to conducting a longitudinal study with the first four authors of the study to test the framework.

Findings & discussion

Four key themes were identified and described in below and include: wildlife perceptions, conservation and education, livelihoods, and governmental policies. Sub-themes were also included, and differences in sociocultural, sociopolitical, and socioeconomic conditions were also evident throughout different countries.

Table 3. Overview of Four Key Themes and Related Sub-themes.

Key findings theme #1: Wildlife perceptions: Positive local perceptions of wildlife

Generational perceptions

In a meta-analysis of existing literature on human attitudes towards large mammals, Kanskay and Knight (2014) found that age is rarely a significant factor affecting perceptions of wildlife and wildlife-human conflict. However, this study supports emerging evidence by Hamilton et al. (Citation2020) to the contrary, where age and sociopolitical identity may significantly influence human perceptions of wildlife, with older (often white in a Euro-American context) males who surround themselves with similar-minded, conservative-leaning social groups holding the most anti-wildlife perspectives. In 37 out of the 41 interviews, nearly all respondents shared that individuals from older age groups (ranging from 55 years or older per their estimates) tended to hold more negative perceptions of wildlife and were more resistant to wildlife-human coexistence, especially if it was viewed to conflict with economic livelihoods. Generational wildlife perceptions transcended across multiple cultures and sociocultural demographic groups meriting further research. All respondents discussed the overwhelmingly favorable transition of young adults’ attitudes compared to previous generations. Respondent #16 described the differences in reactions between wolf sanctuary visitors:

When I tell adults, especially older adults, about how wolves affect ecosystems their jaws drop. They’re like, wow! I had no idea. Meanwhile, the kids just sit there and nod their heads. The kids tell me all the time how they are learning about wildlife. I’m excited about the change that the youth will bring, I just hope it’s not too late before people like you can do something about it.

Negative opinions may originate in culturally held attitudes and younger generations are perhaps being exposed to more pro-wildlife education than previous generations (Hopper et al., Citation2019; Lappalainen, Citation2019).

Rural versus urban perceptions

All respondents described interactions with at least some rural residents who perceived that they suffered from the ‘damage’ of wildlife conflict, while urbanites reaped the rewards of coexistence. The Italian organization provided photographic evidence of bear attacks on livestock of one rural resident, demonstrating that negative perceptions of bear conflict are at times warranted. Respondent #1 shared:

In general, bear damages are not high in economic value, I would say. Sometimes, the perception from the older people is quite bad because you have a big animal, the largest carnivore in Italy, that on rare occasions is going into your garden, is killing your livestock, is breaking probably the branches of your fruit trees and so, the perception from some people who are not very educated in coexistence with wildlife is very bad and that’s very frustrating because, let’s say the bear is an icon for our territory, but some people still look at the bear as a competitor or a pest to destroy.

Rural viewpoints may further exacerbate issues of conflict, skewing the magnitude of these problems. In some cases, interviewees revealed that rural residents may go as far as retaliating to livestock depredation by setting bait traps and other lethal measures. Dickman (Citation2010) found that people tend to exaggerate the potential risk of wildlife damage to their livelihood.

However, interactions between rural residents and urban tourists may lead to a positive shift in wildlife-perceptions. Respondent #1 expressed:

The older people in the communities see the youth come in from the cities and abroad just to see the bears. It brings in money to the economy and people are starting to say to themselves, well if the young people come here just to see the bears then maybe there’s something to it.

This sentiment was echoed throughout the conversations with representatives from Scotland, Italy, and Costa Rica. All interviewees suggested that increased interactions between generations, as well as urbanites and rural dwellers, may help to alter local perceptions of wildlife.

Key findings theme #2: biodiversity conservation: education & animal welfare

The steady expansion of the global human ecological footprint and demand for natural resources has been correlated with negative effects on biodiversity, resulting in altered wildlife migration habits and increased risk of extinction (Karimi & Jones, Citation2020). One of the most common approaches to biodiversity conservation in this study was wildlife rescue and rehabilitation. Sanctuary models operated mixed-access facilities in which there was a sanctuary side - open to ecotourists, and a rehabilitation side - closed to the public.

These sanctuaries responded to calls regarding injured or orphaned wildlife, or when wildlife-human conflict ensued. Respondent #11 shared:

We had somebody call a few weeks ago because something was eating their chickens, and so they set a trap and caught an ocelot. Instead of just killing it, or killing it for income, they called us to see how we could help. I mean that's not necessarily a reflection of us, but I think that’s a reflection of education and support in the country that’s changing the perspective of wildlife and understanding that it’s something to be preserved.

When nonhuman animals suffered from a critical life-threatening disability or disadvantage, barring them from a safe return to their natural habitat, they were cared for using husbandry methods similar to those employed at zoos. Resident wildlife served as “ambassadors” to educate visitors about the species and their environment. Those that could be rehabilitated entered a veterinary hospital where they received initial care, were transferred to pre-release enclosures that simulated a “wilderness environment”, and were eventually released.

In Costa Rica, rescue centers are, in part, financially and logistically supported by the government. The Sistema Nacional de Áreas de Conservación or National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC) provides funding for the initial veterinary assessment of rescued wildlife. SINAC also facilitates wildlife transportation, provides training, and enforces regulations concerning wildlife handling and treatment. Grant opportunities also exist to support sanctuaries and offset their operating costs. Costa Rica wildlife excursion operators (e.g. howler-monkey sightseeing jungle walks) also partner with SINAC to engage in biodiversity conservation. For example, one organization in the study placed volunteers as guardians over a migrating group of critically endangered White-lipped Peccaries (Tayassu pecari) to protect them from poaching. Respondent #14 Shared:

We work with a variety of communities across the peninsula, but one model community converted to less hunting, and now they do more rural community tourism. One of the amazing initiatives led in collaboration with SINAC and also a group of volunteers was protecting the chanchos de monte (white-lipped peccaries) as they migrated out of Corcovado National Park into the peninsula. They worked tirelessly day and night to be bodyguards to prevent people from hunting based on social and legal pressure.

The excursion model organizations tended to focus less on individual species and instead spend their resources restoring and protecting the environment. They frequently relied on work from international volunteers to perform various habitat restoration projects such as planting native flora, managing road ecology, monitoring rivers, building fences, etc. Respondent #18 provides insight on combining conservation volunteering for habitat restoration with ecotherapy for human well-being:

It’s conservation volunteering, people come in to do practical work on the land and they come to us for a week. It’s a combination of a sense that you’re contributing to something that aligns with your values, and in a safe way, you can share that experience with others. You feel like you’re part of a community. You’re helping your wider set of values and your wider stories about your relationship with nature and the land. Some say this has changed their life in some way.

(Environmental) education

There appeared to be a direct correlation between the level of education and perception of wildlife. It may be the single most persuasive factor, in terms of unifying communities in supporting wildlife and influencing the success of ecotourism establishments. Respondent #5 summarized this well:

The main differences between the communities that have had success and the ones that have had more troubles are that the elders of the community are really involved, and the population is pretty educated, so these communities are very unified. The other communities aren’t as unified and aren’t as educated. When they’re trying to go about ecotourism, which makes them interested in conservation, they do it as single landowners and they don’t do as good with communication and advertising, so they go hand in hand.

Though previous studies suggest that basic levels of formal education may generally be a poor predictor of positive attitudes towards wildlife (Kansky & Knight, Citation2014), specific working knowledge of wildlife, natural history, and conservation can significantly strengthen pro-wildlife outlooks that may be crucial in leading pro-environmental action (Klöckner, Citation2013).

Wildlife literacy has shown to positively affect human attitudes towards other species (Hopper et al., Citation2019; Melson, Citation2005). Wildlife ecotourism organizations facilitate educational exchanges through local outreach programs. Respondent #14 stated:

The older people are the ones that are going to be making the decisions right now, so you need to focus on them. When you work with kids, it’s a way to getting to their parents; parents that might be very busy with work and might not have time to think about an issue. If you work with the kids, then you send them homework. Through the kids, you are making a change in the mindset of older people.

Key findings theme #3: livelihoods: wildlife ecotourism & sustainable development

Wildlife ecotourism could be a key driver to wildlife-human coexistence and sustainable development as the very presence of newcomers may provide communities the incentive to promote WE as a means to enhance individual livelihoods (Kc et al., Citation2018; Shoo & Songorwa, Citation2013). Wildlife “value” and protections may be advanced through the “buy-in” of WE initiatives at the community level. Much like Holling and Meffe (Citation1996) model of ecological systems, “adaptive cycles” are present within sustainable development. For example, Glikman et al. (Citation2019) provide evidence of local attitudes in support of biodiversity conservation regarding the Marsican Brown Bear (Ursus arctos marsicanus) of Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (PNALM) (Falcucci et al., Citation2008; Maiorano et al., Citation2019). The Italian organization’s excursion model acts as a channel to link tourism to conservation while engaging the community and building support for sustainable WE and development.

Wildlife ecotourism may advance biodiversity efforts, protect wildlife, and promote their welfare (Thomsen et al., Citation2021a). For example, one Costa Rican organization utilized WE to build ecological conservation networks that connect core habitat areas (Finegan et al., Citation2008), assist the recovery of declining species (Whitworth et al., Citation2018), design quality control programs for the restoration of riparian habitats and downstream estuaries (Fournier et al., Citation2019), design policy recommendations for forest conservation (Sierra & Russman, Citation2006), and build community well-being through indicators of economic, social, and environmental impact (Hunt et al., Citation2015).

Key findings theme #4: governmental policies

Wildlife “management” policies are complex and vary by location and context. Madden (Citation2004) states, “numerous factors, including biological, geographic, political, economic, social, institutional, financial, cultural, and historical features, make each conflict or coexistence situation unique” (p.249). Policies enacted and enforced often have a domino-like effect that may influence how organizations and citizens interact with nonhumans. The multi-country interviewees all indicated at least some governmental agency involvement, either directly or indirectly, and depicted a spectrum of restrictions and protections.

U.S. based organizations described how big industry (e.g. agriculture, oil and gas) regularly lobbied governmental representatives to skew power dynamics in their favor. Respondent #16 described the complexity of U.S. government programs that pit human economic interests against wildlife recovery:

It’s very complicated because our policies [in the U.S.] are complicated. Any time you have a federal program you’re dealing with a bureaucracy. The same place you lease land to oil companies and livestock owners is federal land. If you have a federal wildlife recovery program, it’s also on federal land. So, they’re putting them together and expecting there to be no conflict. It’s insane to put them together and be upset when there’s conflict.

While U.S. respondents discussed the hyper-politicization of environmental policies, those from Scotland expressed reserved optimism as the management of protected areas operates a blended public-private model. Respondent #15 stated, “most of the land inside our national park is privately owned” and stressed that making their national parks welcoming to tourists was important to draw attention and revenue to pro-wildlife and environmental restoration causes, but that further wildlife protection laws were needed.

However, even when pro-wildlife laws are enacted, enforcement can prove difficult. For example, Italy’s conservation action plan for the Marsican brown bear, Piano d’Azione Nazionale per la Tutela dell’ Orso Bruno Marsicano (PATOM), inspired Respondents #1–3 and their colleagues to start a pro-bear organization. Respondent #1 shared:

The PATOM is an action plan for the conservation of the Marsican Brown bear. Before the establishment of [organization], future members were looking at the pattern as if it was a kind of Bible. It was very well written. It’s still very well written, but we saw that these institutions weren’t implementing or enforcing it at all. We were very motivated to do something, to take action, to do something very practical, very grass-rooted because we understood that just a small example could make a difference.

The interviews with the Costa Rican organizations stood out for their considerable emphasis on positive governmental involvement and intervention related to wildlife welfare and coexistence. Constructive collaboration seems to be driven by a unified goal, directed and supported by agencies such as MINAET (Ministry of the Environment, Energy, and Technology) and SINAC. Respondent #9 stated:

If people find an injured animal they can call this agency, but they keep everybody in line as well to make sure we’re following the laws of Costa Rica and following protocols that we should and so, I think having that umbrella as well, helps everybody know we’re following the same rules, we’re doing the same thing, and we’re all working together for that same cause overall.

In this case, governmental leadership functions as an essential intermediary and organizing influence between otherwise disconnected entities. Respondent #13 spoke about the role of the government in its operation:

[The Costa Rican government is] huge in the whole country. They protect the national parks. They guard them or have stations in some of the bigger places, just trying to make sure people aren’t coming through and causing any damage or stealing, taking any animals. It’s a pretty good system. If we’re too far away, they can bring animals to us and collect them from the people that find them. They pay us to do the initial assessment of the animal, so if it’s either x-rays, blood work, surgery, stuff like that.

In the U.S. private land ownership and industrial interests seemed to be at odds with pro-wildlife initiatives. However, when the goals of governmental agencies, industry, and nonprofit organizations are aligned it may promote an environment conducive to cooperation and growth that advocates wildlife-human coexistence. Costa Rica, and to a lesser extent Italy, appeared to be optimal testing beds of the multispecies livelihood framework, as strong governmental policies empowered WE and rehabilitation organizations to advocate wildlife needs, resulting in increased community involvement and support. Local citizens also helped to influence governmental policy, as Costa Rica appears to have embraced WE as a pathway toward sustainable development and biodiversity conservation.

Conclusion

Wildlife ecotourism is a community-based human livelihood approach to sustainable development and biodiversity conservation (Copeland, Citation2021; Kc et al., Citation2018; Shoo & Songorwa, Citation2013), as locals often possess “first-hand knowledge of local landscapes and native flora and fauna” (D’Cruze et al., Citation2017, p.2). Our findings support previous research of three primary mechanisms for governmental support that reinforce conservation networks and emphasize its importance in the multispecies livelihoods framework: (1) financial incentives for locals; (2) logistical and financial assistance for conservation organizations; and (3) legal enforcement of protections. Each component of the multispecies livelihoods framework is complex in its own right, but we argue that by increasing (environmental) education and sustainable development opportunities, local perceptions toward wildlife may positively change to result in greater support for wildlife-human coexistence and animal welfare, rights, and agency (Copeland, Citation2021; Thomsen & Thomsen, Citation2020).

Future pathways

Wildlife tourism has been widely criticized for exploiting nonhuman animals, particularly in WTAs, who often endure inhumane practices that place nonhumans’ welfare at risk (Moorhouse et al., Citation2017). In this study, we responded to Belicia and Islam (Citation2018) call for decommodified wildlife tourism, and Cohen’s (Citation2019) argument for a posthumanist approach to tourism that values wildlife and humans equally. Though the sample size was U.S. dominated for logistical reasons, these initial findings support the need for further research to test the efficacy of the model in a variety of settings and cultures. The ecological crisis demands immediate and sustained action if wildlife is to persist, at the species and individual levels.

The multispecies livelihoods framework provides global tourism scholars and practitioners a posthumanist approach to wildlife ecotourism that challenges us, as humans, to embrace our moral obligation to nonhumans and equitably advocate for their rights, welfare, and agency. Ultimately, the MLF is a simple attempt to underscore the urgent need for equitable power relations between species in tourism settings, directly and indirectly. We plead to you, as tourism scholars and practitioners, to immediately and sustainably leverage our collective platform, privilege, and power – in its varying degrees of inequality within human relations – to redress the status quo (e.g. commodification and domination of nonhumans) in wildlife (eco)tourism. We must equitably foreground all human and nonhuman animals’ rights, agency, and welfare in theory and practice, or we may soon regret that we could have done something to stave off species’ extinction and improve the quality of life for individuals. Or we will have no one to blame but ourselves.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Falk, J. (2011). Visitors’ learning for environmental sustainability: Testing short- and long-term impacts of wildlife tourism experiences using structural equation modeling. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1243–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.11.003

- Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., Hughes, K., & Dierking, L. (2007). Conservation learning in wildlife tourism settings: Lessons from research in zoos and aquariums. Environmental Education Research, 13(3), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701430604

- Balmford, A., Beresford, J., Green, J., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M., Manica, A., & Reid, W. V. (2009). A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biology, 7(6), e1000144-6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144

- Bansal, S. P., & Kumar, J. (2013). Ecotourism for community development: A stakeholder’s perspective in great Himalayan National Park. In E. G. Carayannis (Ed.), Creating a sustainable ecology using technology-driven solutions (pp. 88–98). IGI Global.

- Belicia, T. X. Y., & Islam, M. S. (2018). Towards a decommodified wildlife tourism: Why market environmentalism is not enough for conservation. Societies, 8(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030059

- Bohlmann, C., Krumbholz, L., & Zacher, H. (2018). The triple bottom line and organizational attractiveness ratings: The role of pro‐environmental attitude. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1507

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., & Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1251689

- Burns, G. L. (2017). Ethics and responsibility in wildlife tourism: Lessons from compassionate conservation in the anthropocene. In I. B. de Lima & A. J. Green (Eds.), Wildlife tourism, environmental learning and ethical encounters (pp. 213–220). Springer.

- Cantor, A., & Knuth, S. (2019). Speculations on the postnatural: Restoration, accumulation, and sacrifice at the Salton Sea. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(2), 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18796510

- Carter, N. H., Shrestha, B. K., Karki, J. B., Pradhan, N. M. B., & Liu, J. (2012). Coexistence between wildlife and humans at fine spatial scales. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(38), 15360–15365. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210490109

- Castree, N. (2008). Neoliberalising nature: The logics of deregulation and reregulation. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(1), 131–152. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3999

- Chapin III, F. S., Kofinas, G. P., & Folke, C. (Eds.). (2009). Principles of ecosystem stewardship: Resilience-based natural resource management in a changing world. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Clark, E., Mulgrew, K., Kannis-Dymand, L., Schaffer, V., & Hoberg, R. (2019). Theory of planned behaviour: Predicting tourists’ pro-environmental intentions after a humpback whale encounter. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(5), 649–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1603237

- Cohen, E. (2019). Posthumanism and tourism. Tourism Review, 74(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2018-0089

- Copeland, K. (2020). Commodifying Biodiversity: Socio-economic approaches to wildlife-human coexistence. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Partnerships for the Goals (Vol. 1, 1st ed.). Springer. 1–12.

- Copeland, K. (2021). Reimagining innovation for “social” entrepreneurship: Nonhuman spaces for the SDGs. Journal for the International Council for Small Business. Doi:10.1080/26437015.2021.1882917

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

- Curtin, S., & Kragh, G. (2014). Wildlife tourism: Reconnecting people with nature. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 19(6), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2014.921957

- D’Cruze, N., Machado, F. C., Matthews, N., Balaskas, M., Carder, G., Richardson, V., & Vieto, R. (2017). A review of wildlife ecotourism in Manaus, Brazil. Nature Conservation, 22, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.22.17369

- Descola, P., & Pálsson, G. (1996). Nature and society: Anthropological perspectives. Taylor & Francis.

- Dickman, A. J. (2010). Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Animal Conservation, 13(5), 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x

- Duffy, R. (2008). Neoliberalising nature: Global networks and ecotourism development in Madagascar. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(3), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802154124

- Faier, L., & Rofel, L. (2014). Ethnographies of encounter. Annual Review of Anthropology, 43(1), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-030210

- Falcucci, A., Maiorano, L., Ciucci, P., Garton, E. O., & Boitani, L. (2008). Land-cover change and the future of the Apennine Brown Bear: A perspective from the past. Journal of Mammalogy, 89(6), 1502–1511. https://doi.org/10.1644/07-MAMM-A-229.19i

- Fennell, D. A. (2013). Tourism and animal welfare. Tourism Recreation Research, 38(3), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2013.11081757

- Fennell, D., & Weaver, D. (2005). The ecotourium concept and tourism-conservation symbiosis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(4), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580508668563

- Filion, F. L., Foley, J. P., & Jacqemot, A. J. (1994). The economics of global ecotourism. In M. Munasinghe & J. McNealy (Eds.), Protected area economics and policy: Linking conservation and sustainable development (pp. 235–252). The World Bank.

- Finegan, B., Herrera Fernández, B., Delgado, D., Campos Arce, J. J., Céspedes, M. V., & Velásquez, S. (2008). Diseño de una red ecológica de conservación entre la Reserva de Biosfera La Amistad y las áreas protegidas del Área de Conservación Osa, Costa Rica.

- Fletcher, R. (2019). Ecotourism after nature: Anthropocene tourism as a new capitalist “fix. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(4), 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1471084

- Fournier, M. L., Castillo, L. E., Ramírez, F., Moraga, G., & Ruepert, C. (2019). Evaluación preliminar de la influencia del área agrícola sobre la calidad del agua en el Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales, 53(1), 92–112.

- Fox, C. H., & Bekoff, M. (2011). Integrating values and ethics into wildlife policy and management—lessons from North America. Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 1(1), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani1010126

- Gaston, K. J., & Spicer, J. I. (2013). Biodiversity: An introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

- Gilchrist, A., & Taylor, M. (2016). The short guide to community development 2e. Policy Press.

- Glikman, J. A., Ciucci, P., Marino, A., Davis, E. O., Bath, A. J., & Boitani, L. (2019). Local attitudes toward Apennine brown bears: Insights for conservation issues. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(5), e25. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.25

- Gluszek, S., Ariano-Sánchez, D., Cremona, P., Goyenechea, A., Luque Vergara, D. A., Mcloughlin, L., Morales, A., Reuter Cortes, A., Rodríguez Fonseca, J., Radachowsky, J., & Knight, A. (2020). Emerging trends of the illegal wildlife trade in Mesoamerica. Oryx, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605319001133

- Grass, I., Loos, J., Baensch, S., Batáry, P., Librán‐Embid, F., Ficiciyan, A., Klaus, F., Riechers, M., Rosa, J., Tiede, J., Udy, K., Westphal, C., Wurz, A., & Tscharntke, T. (2019). Land‐sharing/‐sparing connectivity landscapes for ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation. People and Nature, 1(2), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.21

- Grau, R., Kuemmerle, T., & Macchi, L. (2013). Beyond ‘land sparing versus land sharing’: Environmental heterogeneity, globalization and the balance between agricultural production and nature conservation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(5), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.06.001

- Green, J. M. H., Fisher, B., Green, R. E., Makero, J., Platts, P. J., Robert, N., Schaafsma, M., Turner, R. K., & Balmford, A. (2018). Local costs of conservation exceed those borne by the global majority. Global Ecology and Conservation, 14, e00385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00385

- Green, R., & Giese, M. (2004). Negative effects of wildlife tourism on wildlife. In K. Higginbottom (Ed.), Wildlife tourism: Impacts, management and planning (pp. 81–97). Common Ground.

- Grooten, M., Almond, R. E. A. (2018). Living planet report-2018: Aiming higher.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Gurung, D. B., & Seeland, K. (2008). Ecotourism in Bhutan. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.004

- Haidir, I., Macdonald, D. W., & Linkie, M. (2020). Sunda clouded leopard Neofelis diardi densities and human activities in the humid evergreen rainforests of Sumatra. Oryx, 55(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605319001005

- Hamilton, L. C., Lambert, J. E., Lawhon, L. A., Salerno, J., & Hartter, J. (2020). Wolves are back: Sociopolitical identity and opinions on management of Canis lupus. Conservation Science and Practice, 2(7), e213. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.213

- Hanna, P. (2012). Using internet technologies (such as Skype) as a research medium: A research note. Qualitative Research, 12(2), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111426607

- Haraway, D. (2008). When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

- Harte, M., Campbell, H., & Webster, J. (2010). Looking for safe harbor in a crowded sea: Coastal space use conflict and marine renewable energy development. In: Shifting Shorelines: Adapting to the Future,The 22nd International Conference of The Coastal Society , June 13-16, 2010 ,Wilmington, North Carolina, USA.

- Higginbottom, K. (2004). Wildlife tourism: An introduction. In K. Higginbottom (Ed.), Wildlife tourism: Impacts, management and planning (pp. 1–11). Common Ground.

- Hill, C. M. (2015). Perspectives of “conflict” at the wildlife–agriculture boundary: 10 years on. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 20(4), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2015.1004143

- Holling, C. S., & Meffe, G. K. (1996). Command and control and the pathology of natural resource management. Conservation Biology, 10(2), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020328.x

- Hopper, N. G., Gosler, A. G., Sadler, J. P., & Reynolds, S. J. (2019). Species’ cultural heritage inspires a conservation ethos: The evidence in black and white. Conservation Letters, 12(3), e12636. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12636

- Hunt, C. A., Durham, W. H., Driscoll, L., & Honey, M. (2015). Can ecotourism deliver real economic, social, and environmental benefits? A study of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.965176

- Hyvärinen, P. (2019). Beekeeping Expertise as Situated Knowing in Precarious Multispecies Livelihoods. Sosiologia, 56(4), 365–381. https://www.sosiologia.fi/2019-2/

- Kansky, R., & Knight, A. T. (2014). Key factors driving attitudes towards large mammals in conflict with humans. Biological Conservation, 179, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.008

- Karanth, K. K., DeFries, R., Srivathsa, A., & Sankaraman, V. (2012). Wildlife tourists in India’s emerging economy: Potential for a conservation constituency? Oryx, 46(3), 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060531100086X

- Karimi, A., & Jones, K. (2020). Assessing national human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation in Iran. Ambio, 49(9), 1506–1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01305-8

- Kc, B., Morais, D. B., Seekamp, E., Smith, J. W., & Peterson, M. N. (2018). Bonding and bridging forms of social capital in wildlife tourism microentrepreneurship: An application of social network analysis. Sustainability, 10(2), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020315

- Kirksey, S. E., & Helmreich, S. (2010). The emergence of multispecies ethnography. Cultural Anthropology, 25(4), 545–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01069.x

- Klöckner, C. A. (2013). A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behavior – A meta-analysis. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1028–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.014

- Kohn, E. (2013). How forests think: Toward an anthropology beyond the human. University of California Press.

- Kremen, C. (2015). Reframing the land-sparing/land-sharing debate for biodiversity conservation: Reframing the land-sparing/land-sharing debate. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1355(1), 52–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12845

- Lamb, G. (2019). Spectacular sea turtles: Circuits of a wildlife ecotourism discourse in Hawai ‘i. Applied Linguistics Review, 12(1), 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2019-0104

- Lappalainen, K. (2019). Recall of the Fairy-Tale Wolf:“Little Red Riding Hood” in the Dialogic Tension of Contemporary Wolf Politics in the US West. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 26(3), 744–767. https://doi.org/10.1093/isle/isz065

- Lopez Gutierrez, B., Almeyda Zambrano, A. M., Mulder, G., Ols, C., Dirzo, R., Almeyda Zambrano, S. L., Quispe Gil, C. A., Cruz Díaz, J. C., Alvarez, D., Valdelomar Leon, V., Villareal, E., Sanchez Espinosa, A., Quiros, A., Stein, T. V., Lewis, K., & Broadbent, E. N. (2019). Ecotourism: The ‘human shield’ for wildlife conservation in the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Journal of Ecotourism, 19(3), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1686006

- Lynn, W. S. (2010). Discourse and wolves: Science, society, and ethics. Society & Animals, 18(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1163/106311110X12586086158529

- Madden, F. (2004). Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife: Global perspectives on local efforts to address human–wildlife conflict. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9(4), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200490505675

- Maiorano, L., Chiaverini, L., Falco, M., & Ciucci, P. (2019). Combining multi-state species distribution models, mortality estimates, and landscape connectivity to model potential species distribution for endangered species in human dominated landscapes. Biological Conservation, 237, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.06.014

- Manfredo, M. J., Teel, T. L., & Dietsch, A. M. (2016). Implications of human value shift and persistence for biodiversity conservation. Conservation Biology : The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 30(2), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12619

- Manfredo, M. J., Urquiza-Haas, E. G., Carlos, A. W. D., Bruskotter, J. T., & Dietsch, A. M. (2020). How anthropomorphism is changing the social context of modern wildlife conservation. Biological Conservation, 241, 108297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108297

- Melson, G. F. (2005). Why the wild things: Animals in the lives of children. Harvard University Press.

- Mitchell, T. (2002). Rule of experts: Egypt, techno-politics, modernity. University of California Press.

- Moorhouse, T. P., Dahlsjö, C. A. L., Baker, S. E., D'Cruze, N. C., & Macdonald, D. W. (2015). The customer isn’t always right—conservation and animal welfare implications of the increasing demand for wildlife tourism. PloS One, 10(10), e0138939. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138939

- Moorhouse, T., D'Cruze, N. C., & Macdonald, D. W. (2017). Unethical use of wildlife in tourism: What’s the problem, who is responsible, and what can be done? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 505–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1223087

- Naidoo, R., Gerkey, D., Hole, D., Pfaff, A., Ellis, A. M., Golden, C. D., Herrera, D., Johnson, K., Mulligan, M., Ricketts, T. H., & Fisher, B. (2019). Evaluating the impacts of protected areas on human well-being across the developing world. Science Advances, 5(4), eaav3006. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3006

- Nellemann, C., Henriksen, R., Raxter, P., Ash, N., Mrema, E., & Pravettoni, R. (Eds.). (2014). The environmental crime crisis: Threats to sustainable development from illegal exploitation and trade in wildlife and forest resources: A rapid response assessment. United Nations Environment Programme.

- Nie, M. A. (2001). The sociopolitical dimensions of wolf management and restoration in the United States. Human Ecology Review, 8(1), 1–12.

- Parathian, H. E., McLennan, M. R., Hill, C. M., Frazão-Moreira, A., & Hockings, K. J. (2018). Breaking through disciplinary barriers: Human-wildlife interactions and multispecies ethnography. International Journal of Primatology, 39(5), 749–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-018-0027-9

- Peterson, M. N., & Nelson, M. P. (2017). Why the North American model of wildlife conservation is problematic for modern wildlife management. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 22(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2016.1234009

- Pettersson, H. L., & de Carvalho, S. H. C. (2020). Rewilding and gazetting the Iberá National Park: Using an asset approach to evaluate project success. Conservation Science and Practice, 3, e258.

- Radeloff, V. C., Hammer, R. B., & Stewart, S. I. (2005). Sprawl and forest fragmentation in the US Midwest from 1940 to 2000. Conservation Biology, 19(3), 793–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00387.x

- Rastegar, R. (2020). Tourism and justice: Rethinking the role of governments. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 102884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102884

- Redpath, S. M., Bhatia, S., & Young, J. (2015). Tilting at wildlife: Reconsidering human-wildlife conflict. Oryx, 49(2), 222–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605314000799

- Reynolds, P. C., & Braithwaite, D. (2001). Towards a conceptual framework for wildlife tourism. Tourism Management, 22(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00018-2

- Scheyvens, R. (1999). Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management, 20(2), 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00069-7

- Sekhar, N. (2003). Local people’s attitudes towards conservation and wildlife tourism around Sariska Tiger Reserve, India. Journal of Environmental Management, 69(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2003.09.002

- Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1932–1946. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1779732

- Sheppard, V. A., & Fennell, D. A. (2019). Progress in tourism public sector policy: Toward an ethic for non-human animals. Tourism Management, 73, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.017

- Shoo, R. A., & Songorwa, A. N. (2013). Contribution of eco-tourism to nature conservation and improvement of livelihoods around Amani nature reserve. Journal of Ecotourism, 12(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2013.818679

- Sierra, R., & Russman, E. (2006). On the efficiency of environmental service payments: A forest conservation assessment in the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Ecological Economics, 59(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.10.010

- Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). University of Illinois Press.

- Steffen, W., Persson, A., Deutsch, L., Zalasiewicz, J., Williams, M., Richardson, K., Crumley, C., Crutzen, P., Folke, C., Gordon, L., Molina, M., Ramanathan, V., Rockström, J., Scheffer, M., Schellnhuber, H. J., & Svedin, U. (2011). The Anthropocene: From global change to planetary stewardship. Ambio, 40(7), 739–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0185-x

- Stone, M. T., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2017). Ecotourism influence on community needs and the functions of protected areas: A systems thinking approach. Journal of Ecotourism, 16(3), 222–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1221959

- Stone, M. T., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2018). Protected areas, wildlife-based community tourism and community livelihoods dynamics: Spiraling up and down of community capitals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(2), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1349774

- Stronza, A. (2001). Anthropology oftTourism: Forging new ground for ecotourism and other alternatives. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30(1), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.261

- Thomsen, B. (In press). Wolf ecotourism: A posthumanist approach to wildlife ecotourism. In D. Fennell (Ed.), Routledge’s Handbook of Ecotourism. Routledge.

- Thomsen, B., Muurlink, O., & Best, T. (2018). The political ecology of university-based social entrepreneurship ecosystems. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-08-2017-0068

- Thomsen, B., Muurlink, O., & Best, T. (2019). Backpack bootstrapping: Social entrepreneurship education through experiential learning. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 10(3), 1–27.

- Thomsen, B., Muurlink, O., Best, T., Thomsen, J., & Copeland, K. (2020a). Transcultural development. Human Organization, 79(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259.79.1.43

- Thomsen, B., & Thomsen, J. (2020). Multispecies livelihoods: Partnering for sustainable development and biodiversity conservation. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Partnerships for the Goals (Vol. 1, 1st ed., pp. 1–11). Springer.

- Thomsen, B., Thomsen, J., Cipollone, M., & Coose, S. (2021a). Let’s Save the Bear: A multispecies livelihoods approach to wildlife conservation and achieving the SDGs. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 2(2), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/26437015.2021.1881934

- Thomsen, J., Thomsen, B., Copeland, K., Coose, S., Blackwell, S., & Dante, V. (2021b). Social enterprise as a model to improve live release and euthanasia rates in animal shelters. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 654572. doi: 10.3389/fvets.

- Thomsen, B., Gosler, A., Cousins, T. (2020b). Democratizing Conservation: A new paradigm in conservation management. Working paper. Oxford, UK.

- Tscharntke, T., Clough, Y., Wanger, T. C., Jackson, L., Motzke, I., Perfecto, I., Vandermeer, J., & Whitbread, A. (2012). Global food security, biodiversity conservation and the future of agricultural intensification. Biological Conservation, 151(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.01.068

- Vantassel, S. (2008). Ethics of wildlife control in humanized landscapes: A response. In Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference, vol. 23, no. 23. https://doi.org/10.5070/V423110597

- Whitworth, A., Beirne, C., Flatt, E., Huarcaya, R. P., Diaz, J. C. C., Forsyth, A., Molnár, P. K., & Soto, J. S. V. (2018). Secondary forest is utilized by Great Curassows (Crax rubra) and Great Tinamous (Tinamus major) in the absence of hunting. The Condor, 120(4), 852–862. https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-18-57.1

- Winter, C. (2020). A review of animal ethics in tourism: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on animal ethics in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102989

- Zadeh, B. S., & Ahmad, N. (2010). Participation and community development. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 2(1), 13–14.