Abstract

The tourism sector has recommitted itself to be ‘climate neutral’ by 2050 through its 2021 Glasgow Declaration: A Commitment to a Decade of Tourism Climate Action. The declared ambition is consistent with the Paris Climate Agreement and net-zero emission targets; however, lacks specific actions by which such a transition might be achieved. The highly influential International Energy Agency (IEA) has produced the most detailed global roadmap to a 2050 net-zero future. This paper examines its implications for the tourism sector. Getting to net-zero is imperative to ensure the societal disruption of a + 3 °C or warmer world are avoided, but the IEA net-zero scenario would nonetheless be as transformative for tourism as the internet was. International air travel and tourism growth projections from the tourism sector are not compatible with the IEA net-zero scenario. The geography of transition risk will influence tourism patterns unevenly. The incoherence of tourism and climate policy represents an increasing vulnerability for tourism development. While any business and destination in tourism can act immediately to reduce emissions, the findings compel a critical new research agenda to determine how the assumptions of the IEA, or any net-zero scenario, could be achieved and how this will affect tourism development.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a devastating tragedy for tens of millions and caused considerable economic damage and major new government debt around the world (World Bank, Citation2021). With accelerating distribution of vaccines, the post-COVID-19 pandemic recovery is emerging in a growing number of countries. While pandemic uncertainties associated with health risks, travel restrictions and the economic recovery will continue to reshape tourism for the foreseeable future there is optimism that a new appreciation for travel and renewed commitment to sustainable tourism may emerge (e.g., Galvani et al., Citation2020; Hall et al. Citation2020; Ioannides & Gyimóthy, Citation2020). The pandemic has provided striking lessons to the tourism sector about the effects of global change and the urgent need to respond to the unfolding and potentially far more devastating climate crisis (Gössling et al., Citation2020a). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (UNWTO, Citation2021, no page) has linked the pandemic to the global decline in emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) and concluded that “There is a growing consensus among tourism stakeholders as to how the future resilience of tourism will depend on the sector’s ability to embrace a low carbon pathway and cut emissions by 50% by 2030”.

The pivotal Paris Climate Agreement (UN 2015, p. 22) represents the commitment of 195 signatory countries to avoid the dangerous consequences of anthropogenic climate change by limiting global warming to “well below 2 °C” and aiming for a target of 1.5 °C warming above pre-industrial levels. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change),) (Citation2018) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C reinforced the devastating and widespread impacts of a 2 °C or warmer world for current and future generations and the prospects for irreversible climate tipping points. To keep the Paris Agreement 1.5 °C target within reach, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (Citation2018) stressed that global CO2 emissions must decline 45% by 2030 (from 2010 level) and to net-zero by 2050.

Net-zero (NZ) is a concept that emerged in the climate/natural sciences and is expanding throughout the social sciences as the politics, economics and social dimensions of this historic societal transition are examined. The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (Citation2018, p. 555) defined NZ emissions as “achieved when anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere are balanced by anthropogenic removals over a specified period” (emphasis added). NZ has evolved from this technical concept to the new guiding ambition for climate policy and action. As of June 2021, over 130 countries that collectively represent over 70% of global emissions have committed to net zero targets (Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit, 2021). The timelines of NZ pledges vary, with the large majority connected to the IPCC 2050 target, but some (Bhutan, Suriname, Uruguay, Finland, Austria, Iceland, Sweden) aim to reach their goal before 2050 and others after (Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and China in 2060) or have not yet specified a timeline (Australia and Singapore). While NZ pledges represent essential political ambition, to operationalize what would be one of the greatest transformations in human history remains a formidable task. In response, some countries (Canada, France, New Zealand, UK) have established independent NZ commissions to advise on pathways with strategies and milestones to achieve NZ emissions and foster a just transition regionally and across diverse segments of society. Tourism has not yet been a focal sector for any of these advisory bodies, but their recommendations will be important for reshaping tourism policy and development within their countries. Likewise, the study of the societal NZ transition has not yet reached the tourism studies literature.

While NZ ambitions are consistent with the overarching goal of the Paris Agreement, the policies and plans by which to achieve those ambitions remain a work in progress. An analysis by Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (2021) indicated that only 20% of existing net zero targets met a set of robustness criteria and are not yet supported by near‐term policies, legislation, and investment strategies. UN Secretary General António Guterres (The Guardian, Citation2021a), UNEP. (Citation2020) and others (Carbon Brief, Citation2021) have strongly emphasized the missed opportunity for fiscal rescue and recovery programs to accelerate the NZ transition. Although 2020 emissions were significantly lower due to the Covid-19 pandemic impact on transportation and manufacturing (Friedlingstein et al., Citation2020), the IEA (2021) is projecting emissions to surge in 2021, reversing most of the 2020 decline.

The tourism sector has voiced its support for the Paris Agreement and its science-based emission targets (WTTC, Citation2018). This support was strongly reinforced in the 2021 Glasgow Declaration: A Commitment to a Decade of Tourism Climate Action, that was led by UNWTO, UNEP, VisitScotland, Tourism Declares a Climate Emergency, and the Travel Foundation, and supported by many other tourism departments, organizations, and businesses. While the sector has ‘climate neutral/net-zero’ ambitions by 2050, communications with international tourism leaders found a worryingly unfamiliarity of the strategies by which Paris Agreement compatible energy-emission futures could be achieved and the potential implications for the tourism sector (Gössling & Scott, Citation2018). The lack of specific actions in the Glasgow Declaration, and only unspecific commitments to measure sector emissions, reduce emissions, finance decarbonization and adaptation, and to collaborate on the NZ journey reinforce this concern. Many of these actions have been recommended over a decade ago (e.g., Scott et al., Citation2008), while recent studies demonstrate the persistent disconnect between tourism and climate policy at national scales (Becken et al., Citation2020; Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021).

It has been previously argued that there is a salient need for the tourism research community and tourism sector to assess the implications of Paris Agreement compatible emission scenarios for global tourism and determine which may represent preferable policy pathways that support more economically efficient or rapid tourism decarbonization, and better support of tourism development consistent with the SDGs and principles of climate justice (Gössling, Citation2011; Gössling & Scott, Citation2018; Scott, Citation2021; Scott et al., Citation2010). Diverse international research and civil society organizations have developed a range of low-carbon emission transition pathways to achieve the Paris Agreement 1.5 °C target). None mention tourism (domestic or international) explicitly (Gössling & Scott, Citation2018; Scott, Citation2021) and thus overlook the implications of their policy recommendations for what Lenzen et al. (Citation2018) estimate represents 8% of global emissions.

The inadequate understanding of how the NZ transition would transform tourism, concurrent with increasing physical risks of a changing climate and potential climate litigation risk, and the demands it would place on the sector remains a disconcerting knowledge gap. This NZ transition risk may represent what the Bank for International Settlements (2020) – a forum for global central banks – have termed a ‘Green Swan’ for tourism. The NZ policy and planning challenge is no longer a distant one we have the time to prepare for, rather global leaders in government, business and civil society agree the 2020s will be a decisive decade when critical decisions and investments take place. Illustrative of this momentum are the June 2021 Group of Seven (G7) countries announcement of support for mandatory climate-related disclosures (European Council, Citation2021) and the so called ‘Black Wednesday’ series of courtroom and boardroom defeats for the oil and gas industry in Europe and the US (The Guardian, Citation2021b) that will force companies to reduce emissions not only from their own operations but as well as the products they sell. For example, in a recent case, German NGO Deutsche Umwelthilfe won a lawsuit in Germany’s Constitutional Court, ruling that the country’s mitigation ambitions are insufficient and violate fundamental freedoms (BBC. , Citation2021). The list of similar climate litigation against governments and corporations continues to grow (Climate Case Chart, Citation2021) and illustrates the potential perils of declaring climate ambitions without credible strategies to achieve them. The tourism sector’s insufficient “aspirational” emission reduction strategies have been pointed out for more than a decade (Scott et al., Citation2010), and unfortunately the near decade old conclusion of Gössling et al. (Citation2013, p. 534) remains valid as we embark on this decisive decade of climate action: “… no credible plan of how combinations of technological investment, management strategies, marketing, and consumer behavioral change could achieve the declared tourism sector emission reductions targets have been proffered by the UNWTO or WTTC.”

This paper utilizes the most recent and comprehensive NZ scenario from the prominent International Energy Agency (IEA) (2021) to examine the potentially transformative implications for tourism over the next 30 years. It begins with a critical assessment of the recommended emission reduction strategies and timelines most germane to tourism. The key tourism relevant components of the scenarios presented by IEA are compared with insights in the scientific literature as well as other policy analyses by governments and other NZ stakeholders. The authors highlight where knowledge gaps exist, or where opinion over future pathways, specifically regarding technology innovations, scaling, and their cost, is varied. A suite of indicators was then selected to represent the key recommendations for as many countries as possible to enable an analysis of differential transition risk for the tourism sector worldwide. The methodology and results are followed by discussion of research and policy implications.

The IEA roadmap to net-zero by 2050

The choice of the IEA NZ roadmap for this analysis is purposeful. The IEA was founded in the mid-1970s in response to the world oil crisis. The membership of this multilateral organization is restricted to 30 OECD countries which hold significant oil or gas reserves. IEA has been criticized in the past for serving the interests of fossil fuel industry and downplaying climate change. Fatih Birol, the Executive Director of IEA, called this landmark report the most challenging and important undertaking in the organization’s history. Because of the influence the IEA has in global energy policy, their comprehensive and detailed NZ scenario should not go unnoticed by tourism policy makers and scholars.

The aim of the NZ scenario is not solely to decarbonize the global economy but is consistent with the IEA mandate to advance affordable universal energy access and economic growth. The IEA NZ scenario for 2050 assumes a global population of 9.8 billion (median United Nations projection - UNDESA, Citation2019) and a global GDP that has increased 72%. The scenario relies on six key pillars of change: (1) the rapid expansion of renewable energy sources, (2) electrification of many energy end uses, (3) gains in energy efficiency, (4) notable behavioural change and willingness of citizens, (5) the deployment at scale of a number of emerging and immature technologies including negative emission technologies, (6) international cooperation to facilitate an orderly whole of society transformation. Two of the most commented on elements of the roadmap are the call to end all investment in new fossil fuel extraction projects within one year and that nearly half of the reductions come from technologies that are in the prototype stage of development. Both are highly uncertain and standing in sharp contrast to existing fossil fuel subsidies criticized the UN Sectary General António Guterres (The Guardian, Citation2021a). Behaviour change is also a major pillar of the scenario (IEA, 2021, p. 67). The IEA (2021, p. 4) scenario emphasizes that the NZ transition cannot occur without sustained support of citizens around the world and must be “fair and inclusive, leaving nobody behind.”

Importantly, the IEA emphasizes that this is but one potential path to NZ and that it will need to evolve as technological, economic, political, and social conditions change. While this roadmap is not necessarily ‘the path’ to NZ, it is highly illustrative of the many challenges the NZ transition would instigate for global tourism.

Implications of the IEA NZ roadmap for tourism

The IEA (2021) scenario is the most detailed roadmap to NZ currently available. It sets out 400 specific emission reduction strategies across major emitting sectors to transform the global economy by 2050. Some of the strategies most germane to tourism are summarized in . The IEA NZ scenario has several other notable characteristics. The scenario is consistent with limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 °C without a temperature overshoot (with a 50% probability). This is a scenario where global temperatures are allowed to go beyond 1.5 °C in the near term, but then be brought down by the end of the century by removing CO2 from the atmosphere. It achieves NZ without the use of carbon offsets from outside the energy sector. The IEA contends it places relatively low reliance on technologies actively removing CO2 from the atmosphere, but it does include an important role for carbon capture, storage and use which scientists caution against because these technologies remain unproven at the scale required (Temple, Citation2021). Removing CO2 from the atmosphere in an overshoot scenario might also not be as effective at reducing warming because warming alters the land and ocean CO2 uptake/release feedbacks (Zickfeld et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. IEA NZ emission reduction strategies influential for tourism.

While the IEA NZ scenario is necessarily global in scale, it emphasizes that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach and that each country will need to implement its own strategy based on its unique circumstances. Nonetheless, the IEA scenario emphasizes the critical importance of international cooperation to foster the whole of society cooperation of all levels of government, businesses, investors, and citizens. IEA explored a ‘low international cooperation scenario’ and found NZ took almost 40 years longer to achieve; far too late to achieve the Paris Agreement policy goal. It also warned of the potential for disorderly policy regime to delay NZ as well as adversely impact the global economy. Importantly, the low cooperation scenario acknowledges other key uncertainties, particularly the level of investment, development of bioenergy and synthetic fuels, carbon capture, as well as the social acceptability and rates of some behavioural changes. These uncertainties, as they relate to tourism, are further explored below.

Climate change is already influencing tourism sector investment, planning, operations, and demand (Scott, Citation2021; WTTC, 2017), and as the strategies summarized in illustrate clearly, the implications of the IEA, or any, net-zero scenario pose salient and largely unrecognized transition risks for tourism. Several elements of the IEA NZ scenario will influence tourism operations and investment broadly, including worldwide carbon pricing, the massive deployment of energy efficiency technologies, and the shift to electrification dominated by renewable energy sources. Specific strategies most influential on specific components of the tourism system are described in .

Air travel is the largest source of warming in the tourism system (Lenzen et al., Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2010) and one of the most challenging components to decarbonize. The IEA NZ scenario allows revenue passenger kilometers to grow 3% per year from 2020 levels to 2050 (versus an average of 6% from 2010 to 2019) reaching 14.5 trillion in 2050 by 2050 (compared to the Air Transport Action Group, [Citation2021] post-covid revised central estimate of 20 trillion) (). It reduces aviation emissions approximately 80% from 2019 levels mainly through a combination of rapid development and deployment of prototype sustainable aviation fuels (both bio and synthetic) and demand management. The challenges this implies have been discussed by Gössling et al. (2021a), and both strategies remain highly uncertain, as overcapacities and debt characterize the aviation market situation (Hepburn et al., Citation2020).

Three major behavioural changes combine to reduce aviation emissions 50% by 2050 (). These three strategies to reduce growth in air travel would have important implications for travel costs and access to many destinations. The first demand management strategy is to restrict business travel at 2019 levels (estimated to comprise just over one-quarter of pre-pandemic air travel). The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted business travel and this critical moment of change may provide an opportunity for a long-term shift to achieve this strategy. A 2020 survey found that between 19% and 36% of airline business travel will not return after the pandemic (Idea Works, 2020) and more corporations and governments are seeking to avoid, not offset work related travel (Skift, 2021). Academics are also rethinking travel patterns for a carbon constrained world (Higham & Font, Citation2020; Klöwer et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, as more businesses adopt NZ goals and emission disclosures become mandatory, business leadership may compel emission reductions associated with business travel.

The second strategy is to freeze long‐haul leisure flights (more than six hours) at 2019 levels. This would impact a relatively small proportion of flights but has important implications for primarily long-haul destinations like New Zealand, Australia, and UAE, as well as the tourism focused development strategies of many small island developing states and other least developed countries. As Gössling et al. (Citation2015) analysis of inter-market emission intensities demonstrated, there is large potential for source market shifts and demarketing to reduce emissions while maintaining the tourism economy of many nations. Voluntary behavioural shifts in holiday travel will only curtail demand at insignificant levels (Markham et al., Citation2018; Seetaram et al., Citation2014), though there is support for market-based policies (Gössling et al., Citation2020b). There is also a need for new policy designs informed by behavioural research (Hardisty et al., Citation2019; Sonnenschein & Smedby, Citation2019).

The third strategy requires the modal shift of regional flights of 1 hour to high-speed rail where it is available (estimated 15% of flights in 2019 and 17% in 2050). In April 2021, the government of France introduced a similar policy banning short-haul domestic flights when rail alternatives could cover the same journey in under two-and-a-half hours. Austria had implemented similar bans on certain inter-city routes in late 2020. A 2019 survey by the European Investment Bank found public support (62%) for banning short haul flights (Reuters, 2020). This is supported by national studies investigating social norm change because of Fridays-for-Future demonstrations (for example in Germany; Gössling et al., Citation2020b).

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are the other major IEA strategy to reduce emissions from aviation, with the use of synthetic and advanced biofuels increasing rapidly from almost zero in 2020 to 50% in 2040 and 80% in 2050. Niche markets are also projected for limited capacity electric aircraft. The IEA acknowledges that SAFs are in the low maturity prototype and demonstration phases, and given the slow development of SAFs, timelines are considered highly optimistic. For example, the International Council on Clean Transportation (2021) examined SAF feedstock availability and estimated it could supply between 1.9% and 6.5% of European Union demand in 2035. Longer range estimates by Rystad Energy and HIS Markit suggest SAF will supply only between 15% and 30% in 2050 (New York Times, 2021). Important technical, economic, and political barriers remain (Gössling et al., Citation2021b; Scheelhaase et al., Citation2019; Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021). A massive and rapid increase in alternative propulsion research and development would be required in the early 2020s if the gap in these projections is potentially to be narrowed.

With airlines worldwide having received hundreds of billions in rescue funding from governments (Hepburn et al., Citation2020; IATA, 2020), can investments in SAF research and development and production be expected from the aviation sector? This raises important policy questions about the role of government in SAFs. Aviation’s social licence to operate in a NZ economy and recent trends in climate law would suggest the onus is on industry to prioritize such investments, but this will only happen if mandated by governments, for instance through feed-in quotas and carbon taxes (Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021). The significant cost of technology innovation and carbon taxes stand in sharp contrast to the ICAO CORSIA plan and its objective of marginal cost increases. With much evidence that air travel is to a significant degree induced by the low cost of flying as the real cost of flying has decreased by 60% over the past 20 years (IATA, 2019), the implications a technology transition will have for low-cost air carriers as well as tourist destination choices and travel patterns remains an important area of future inquiry.

Importantly, if the behavioural changes and transition to SAF can be realized, global CO2 emissions from aviation fall to 210 Mt in 2050 in the IEA scenario (down nearly 80% from approximately 1 Gt in 2019) and represent just over 10% of unabated CO2 emissions in 2050. Other studies estimate that aviation could represent as much as 12-27% (ICAO, 2016) of the remaining global carbon budget in 2050. This, however, ignores the role of additional non-CO2 warming, which is likely to remain an issue unless flightpaths are altered (Lee et al., 2021). Social and litigation risks are likely to increase for airlines as aviation represents an increasing share of the dwindling allowable global carbon budget. With a court ruling in 2021 that Royal Dutch Shell’s emission reduction target was inadequate to meet the requisite standard of care under Dutch law, when might a similar ruling be expected for KLM, the national flag carrier? Any such ruling against airlines (particularly those partially government owned) to increase emission reductions would have an abrupt impact on travel cost and possibly demand management strategies.

The IEA aviation strategies and outcomes are highly uncertain and based on the 20-year history of ICAO negotiations on emissions reduction (Scott et al., Citation2012), a disorderly regional/country level implementation is a reasonable prospect, with attendant implications for the introduction of international travel carbon-levies and airspace/gate restrictions on non-compliant air carriers. These aviation strategies and associated costs and outcomes for demand patterns, or indeed any similar carbon constrained scenario for air travel, would be transformative for tourism and necessitates the prioritization of new research to assess the implications for destination competitiveness and future tourism development.

Marine transport was also identified as a difficult to decarbonize sector within the IEA NZ scenario and because of a lack of mature low carbon fuel technology and long operating lifetimes of vessels it does not achieve zero emissions by 2050. Cruise ships were not specifically referred to in the scenario, as they represent less than 1% of international vessels, but the increasing size of cruise ships share the propulsion fuel challenges of other large ships and have additional challenges of providing electricity for what amounts to a floating resort with thousands of travellers and staff.

The 30 million cruise passengers in 2019 (Cruise Lines International Association [CLIA] 2020) represent only 2% of international arrivals but is one of the most carbon intensive forms of tourism. The Cruise Lines International Association (2018) committed to reduce its members emissions 40% by 2030 (from 2008 levels, which does not consider most of the sector’s rapid recent growth). Currently, several cruise operators promote their operations as carbon neutral (MSC cruises, Lindbald Expeditions, Royal Caribbean Cruises, Virgin Voyages) by purchasing offsets equivalent to their ship emissions. Offsets include “forest protection” programmes, in which the conservation of a forest is considered an offset (Mediterranean Shipping Agency, Citation2021); but net emissions continue to increase under this scheme. Some new ships are being fueled with LNG, which reduces emissions approximately 15%-20%. Most new ships are also being equipped to receive shore-side electricity for their extended time in port. Currently this has limited capacity to reduce emissions, as many regions where cruise ships operate have not decarbonized their electricity grids. For example, over 93% of the electricity in the Caribbean region, where one-third of the global cruise fleet operates (CLIA Citation2020), is generated from fossil fuels. Given that most energy is used for propulsion (Simonsen et al., Citation2019), it is however unlikely that continued grid-decarbonization will allow CLIA to achieve its emission reduction targets by 2030.

To approach NZ by 2050, the cruise industry will have to achieve a full-scale fuel transition over the next 30 years and the IEA NZ scenario indicates that governments should define their strategies for low‐carbon fuels in marine transport by 2025 at the latest to guide the major investments required. Ammonia is the main transition fuel for marine transport in the IEA NZ scenario and the fuel that a study by Krantz (2020) concluded was the most cost effective. The IEA NZ estimates ammonia will represent 45% of marine transport fuel in 2050, which is a more rapid deployment than other estimates (e.g., approximate 25% - DNV 2020). Notably, 87% of the estimated cost of decarbonizing marine transport was needed for land-based carbon neutral fuel production and storage infrastructure and only 13% for ship retrofits. Ammonia remains technologically challenging, however, as key problems remain unresolved. It is highly toxic, and the Royal Society (2020, p. 10) calls it a “chronic hazard to […] ecosystems”. Hydrogen and fuel-cell technology was the second most prevalent shipping fuel source in the IEA scenario and may be a long-term option for the cruise industry, but with uncertain fuel cost implications. The transition to new zero-carbon ship fueling infrastructure would concentrate cruise activity at fewer ports of departure and routes, with international development assistance required to support such infrastructure in key markets like the Caribbean. Importantly, a 2020 survey of Europe's 18 largest cruise ship operators found few had started to develop a credible strategy of alternate propulsion systems compatible with the NZ transition or launched pilot projects to test new low emission technologies (Nature & Biodiversity Conservation Union, Citation2020). Marine policy makers, meanwhile, have focused on the sector’s relative emission reductions, with limited attention absolute emission reduction needs (Gössling et al., Citation2021b).

All forms of ground transport are rapidly electrified in the IEA NZ scenario (), accelerating transitions that are underway in many countries. Passenger rail is increasingly electrified (from 50% in 2020 to over 80% in 2040) as electricity grids in more regions are decarbonized and doubles its share of passenger transport (to 20% globally and much higher regionally) by 2050. This heightened role in passenger transport has important implications for tourism in regions with well-developed and improving rail networks and will be an important opportunity for sustainable tourism in destinations with access. New infrastructure, operational systems (scheduling/ticketing) and cost structures will require policy support (market based as well as regulatory) to support such a modal shift to rail.

Electrification also rapidly dominates automobile and bus/coach transport. A combination of policy strategies already enacted in some jurisdictions, including lower speed limits, strict fuel-economy standards, internal combustion engine (ICE) car access and parking restrictions and tolls in large cities and other low emission zones, and ICE car sales bans (), accelerate the market penetration of EVs from just under 5% of global new car sales in 2020 to 60% by 2030 and nearly 100% by the late 2030s. This would represent a faster transition than other projections that estimate EV sales will represent 23-32% globally by 2030 (IHS Markit, Citation2021; Deloitte, 2020). Similarly, the IEA NZ scenario includes no new ICE car sales by 2035, which is later than some jurisdictions (Norway and South Korea 2025; Belgium, Austria, Washington State 2026-27; and 10 other countries in 2030) and auto manufacturers (Volvo 2030, Volkswagen early 2030s), but earlier than 10 countries and several sub-state jurisdictions in 2040-45 and several auto manufacturers (General Motors, Jaguar Land Rover, Honda 2035–2040). By 2050 nearly 90% of cars in operation are electric with the remaining hydrogen powered. It is worth noting that none of these scenarios discusses the implications of continued growth in private car numbers and associated problems such as urban congestion. Electric cars are expensive but comparably cheap to drive, pointing at potential rebound effects in terms of greater use. Some jurisdictions, such as the German state of Baden-Wuerttemberg (Ministry of Transport BW, Citation2021), have thus declared that a 30% reduction in private vehicle numbers is necessary by 2030 to meet climate objectives. This rapid transition also has implications for investment in taxi and rental/car sharing fleets and their refueling infrastructure. Bus/coach vehicles follow a similar rapid transition, with 60% of new sales electric/hybrid in 2030, increasing to 100% by 2050. By 2030 nearly one-quarter of the bus/coach fleet (higher in some regions) would need to be electrified, with important implications for tour bus fleet investment, charging infrastructure and routing.

Tourism sector planning and investment in EV charging infrastructure at hotels/other accommodations, attractions of all types (including remote areas for ecotourism), and travel routes (highway stops, scenic routes, tunnels) would need to accelerate accordingly. The carbon intensity of local-national electricity grids will also determine the pace at which electrification of tourism ground transport should proceed.

Accommodations is another important area of tourism decarbonization. A step change improvement in energy efficiency and electrification are the two main drivers of decarbonization of buildings across all real estate classes in the IEA NZ scenario. There is a rapid transition to zero‐carbon‐ready buildings, which are highly energy efficient and either use renewable energy directly (e.g., heat pump, onsite solar) or an energy supply that will be fully decarbonized by 2050 (e.g., zero carbon electricity grid). Building codes for new construction would need to be updated in all regions by 2030 and widespread retrofit programs put in place to achieve the IEA target of all new commercial buildings and 20% of existing stock zero‐carbon‐ready by 2030 and 85% by 2050.

Hotels and resorts, and their NZ transition challenges (i.e., amenities and visitor energy consumption patterns that make them among the most energy intense of all commercial real estate classes, and complex ownership and management structures), were not specifically examined by the IEA. However, International Tourism Partnership (2017) concludes that the technology exists today to fully decarbonize the hotel industry and alternate lodging (e.g., Airbnb, serviced apartments) and emphasized the importance of expanding calculations of revenue and return on investment to include existing and future price of carbon. Hotel energy intensity is highest among 4 and 5-star hotels in tropical regions (nearly double the intensity of comparable hotels in temperate regions) (Dibene-Arriola et al., Citation2021), and similar NZ retrofit pilot projects are urgently needed in tropical destinations.

As part of the NZ transition, all forms of accommodation will also need to invest in EV charging infrastructure to support the EV shift in private and tour coaches. NZ ready transition guidance will need to be integrated into other programs like the UNWTO Hotel Energy Solutions project supporting small and medium sized enterprises in the accommodation sector. Like ground transport, the carbon intensity of local-national electricity grids will have an important influence on how quickly and deeply tourism accommodation can decarbonize.

As indicated by Gössling et al. (Citation2012) and Scott and Gössling (Citation2018), tourist behavioural changes will also be fundamental to the NZ transition. There is evidence of growing public support for strategies that will curb emissions from aviation through regulation (Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021; Kallbekken & Saelen, Citation2021). While a greater understanding of tourist policy preferences and willingness to pay or adopt specific decarbonization strategies (e.g., modal shifts, destination choice), continue to be important areas of research to advance tourism decarbonization, it is basically understood that governments need to push behavioral change by introducing significant prices on carbon.

IEA NZ strategies alignment with tourism sector emissions

Tourism has been estimated to represent approximately 8% of global CO2 emissions in in 2013 (Lenzen et al., Citation2018). While other studies have used different methodologies, making benchmark and trend comparisons difficult, they nevertheless also show that tourism can be expected to grow rapidly, from 130% from 2005 through 2035 (UNWTO et al., 2007) to 169% 2010 through 2050 (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2015). The sector has acknowledged its responsibility to reduce its emissions as early as the 2007 Davos Declaration on Climate Change and Tourism (UNWTO et al., 2007) and more recently in accordance with science-based targets of the Paris Agreement through the United Nations Climate Neutral Now initiative (WTTC, Citation2018) and the 2021 Glasgow Declaration: A Commitment to a Decade of Tourism Climate Action.

Common to all studies is that they identify air transport as the largest source of emissions. Other forms of transportation and accommodations also rank high in all assessments of tourism emissions. How feasible is it to achieve NZ from each of these major emission sources? As the consulting group Arup et al. (2021) retrofit analysis and existing pioneering projects demonstrated, there is no technical barrier to NZ in accommodations, where the cost of saving energy is often negative (Gössling, Citation2011). The technologies needed exist and, in many cases, will become less expensive over time as demand for retrofits and onsite solar and battery storage increase. Enabling policy, substantial investment (much of which provides near term return on investment), visitor engagement programs, and eventually a low-carbon electricity grid will be critical to achieve deep emission reductions in accommodations.

As the IEA NZ scenario indicates, there are no technical barriers to decarbonizing automobile transport with existing technology, although the supplies of rare earth minerals for batteries, decarbonizing and doubling electricity capacity to power EVs, and reservations among some consumers (current cost comparisons, range, access to charging network) pose important challenges to a rapid deployment of EVs. Nonetheless, with the majority of required EV technology at the market uptake and mature stage and some countries well advanced in the transition (e.g., over 50% of new car sales in Norway in 2021 are EVs) decarbonization of automobile travel could accelerate in accordance with the IEA NZ scenario in many countries with the largest domestic tourism industry with a strongly supportive policy regime (including measure set out in ).

Air travel remains the most difficult and largest source of tourism emissions to abate, though a very significant share of emissions could probably be avoided by simply reducing capacity and addressing the demand patterns of the very frequent fliers (Gössling & Lyle, Citation2021). The political and technological challenges to emission reduction from aviation are discussed in detail by Gössling and Lyle (Citation2021) and Gössling et al. (Citation2021b). With SAFs in the immature prototype stage (IEA, 2021) and past demand management policy experiments (e.g., Cohen & Higham, Citation2011; Higham et al., Citation2016; Markham et al., Citation2018; Seetaram et al., Citation2014) marginally able to influence behavior, the path to deep emission reductions committed to by the aviation sector (ICAO, 2019) and required by the IEA NZ scenario remain the most uncertain for the tourism sector, unless nation states include air transport emissions in their Nationally Determined Contributions and act accordingly.

The financial costs for the tourism sector to pursue the deep decarbonization strategies required by the IEA NZ scenario remain uncertain, as a vision of tourism in the NZ economy of mid-century has not yet been articulated (though calls for a sector wide collaborative vision have been made by the scientific community). The closest examination of potential costs associated with pursuing deep decarbonization consistent with tourism sector ambitions and the IEA NZ scenario found that the cost to achieve a −50% target (by 2050) through abatement and some strategic offsetting (in aviation), while significant, represented less than 0.1% of the estimated global tourism economy in 2020 (approximately USD 600 million annually) and 3.6% (approximately USD 351 billion annually) in 2050 as emission reductions became more difficult (Scott et al., Citation2015). Achieving a −70% emission reduction target more closely aligned with the IEA NZ scenario requirements required greater investment of approximately 4.1% of the anticipated total global tourism economy near to 2050. While challenging, Scott et al. (Citation2015) found the cost of the NZ journey for travellers was roughly equivalent to many current travel fees or taxes, or approximately US$11 per trip when distributed equally among all tourists (international and domestic). With deep decarbonization achieved near mid-century, costs associated with the NZ transition could rapidly decline, and would do so sooner for many early adopters and leading businesses and destinations.

Methodology of comparative NZ transition risk

Net-zero transition risk is defined as the challenges associated with transforming to a low-carbon global tourism economy in comparison, which includes costs and impacts of decarbonizing the tourism sector itself, but also the impacts on tourism from emission reduction policies in other sectors and countries. Like physical climate risk, net-zero transition risks are not equally distributed and will differentially impact tourism demand and competitiveness of destinations and countries in the global tourism market. It is also important to emphasize that the net-zero transition will also represent new market opportunities for many destinations and tourism businesses.

Certain market segments and destinations would be more influenced by the range of strategies and associated costs proposed by the IEA, and it is important to understand this differential transition risk to inform future policy development and potential implications for tourism to contribute to the SDGs in some countries. To examine these differential risks, the paper relies on Scott et al. (Citation2019), who explored the global distribution of climate change risk using 27 indicators. Four of these indicators are selected as specifically relevant to aspects of the NZ transition set out by the IEA, including: (1) the percentage of electricity supply from fossil fuels (signifying where electrification is already a viable NZ strategy and where electricity decarbonization costs are likely to be higher), (2) the average distance to a destination’s top five international markets (designating countries most dependant on long haul air travel with exposure to travel price increases and lower modal substitution options), (3) the size of the outbound international market (indicative of the potential market to replace any decline in international markets resulting from changes in competitiveness or access), and (4) food import dependency (representing exposure to increased transportation costs and price volatility). As in Scott et al. (Citation2019) each indicator was first transposed to quintiles and then combined into a cumulative transition risk score, with the average distance of top international markets to the destination weighted twice as important in the index because of its critical influence on difficult to reduce emissions). Other indicators were weighted equally for a specification as follows:

Transition Risk = percentage of electricity supply from fossil fuels (20%) + the average distance to a destination’s top five international markets (40%) + the size of the outbound international market (20%) + food import dependency (20%)

Transition risk was calculated for 192 countries. Results should be seen as indicative and are shown only for the most and least at-risk destinations. More comprehensive analyses of transition risks should be carried out in the future as new data on relevant indicators becomes available, including different scopes (GHG emissions) as well as first and second order effects (for instance rising carbon costs affecting employment levels in tourism). Other indicators of dimensions of transition risk were explored for this study but were available for too few countries and few developing countries, which would have adversely impacted global insights. The assessment does not consider the relevance of each country’s tourism economy in relation to GDP (i.e., countries with high transition risks and tourism-dependent economies are highlighted), but this is examined in the discussion.

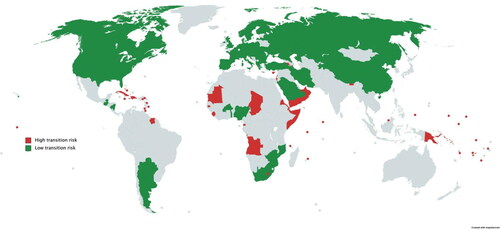

The geography of NZ transition risk

The countries most and least exposed to NZ transition risk are presented in . The lowest transition risk was found in diverse countries, including most countries in Europe that often also have strong outbound markets that could convert to strengthen domestic tourism or neighbouring economies. North America, Argentina, South Africa and China were also found to have low transition risks, with the USA and China having similarly sizable outbound markets. Other countries with low transition risk are not major international tourism destinations (Russia, Kazakhstan, or Ukraine).

Conversely, the highest transition risk was found to largely be concentrated among Small Island Developing States (SIDS) (). These islands all depend on long-haul international markets, commonly have fossil fuel dominated electricity supply, have high food import dependence, and very small outbound markets that could convert to domestic tourism. These countries also have among the highest percentage of GDP derived from tourism, accentuating potential economic impacts associated with tourism transition risk. Many of the larger countries with high transition risks have insignificant tourism industries (Angola, Somalia, Chad or Mauretania). Israel and the UAE are notable exceptions on this list, but both share characteristics of high reliance on long-haul international visitors, fossil fuel dominated electricity, and high food imports.

The climate justice implications of this preliminary analysis of relative NZ transition risk are inescapable. Even though many of the most at risk countries have contributed the least to cumulative historic emissions, they are most likely to see declining tourism competitiveness and adverse impacts on their tourism economies. These tourism economies are carbon-intense and growing, pushing up per capita emissions in SIDS. Although developed countries are bound by the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement to support technology transfer and support the NZ transition in most vulnerable countries, these supports are rarely earmarked to the tourism sector (e.g., major investments in synthetic SAFs would represent such a targeted technology transfer in support of their tourism economies). The tourism sector must therefore develop innovative collaborative mechanisms to support the NZ transition and adaptation to physical climate risks in these most at-risk countries, while also considering alternative business models and economic development strategies. Clearly, there is limited room for countries to further develop their long-haul dependent tourism systems under the IEA scenario.

Conclusion

The climate change and tourism literature has predominantly focused on the impacts (and to a lesser extent the adaptations to) of changing climate on tourism assets, operations, and demand (Scott et al., 2012, Citation2015). Less work has been dedicated to assessing tourism sector emissions and strategies to decarbonize tourism operations and travel. Research on the transition risk to a net-zero economy is virtually absent in the tourism literature and as this analysis indicates, this is a salient gap that must rapidly be addressed. Furthermore, as the IEA global roadmap (and others like it) as well as initial work of national NZ advisory committees, reveal, the tourism sector cannot rely on climate/energy researchers and policy makers to assess the implications of the NZ transition on the tourism sector and countries/destinations most dependent on the tourism economy. The sector and its scholarly community must develop this capacity internally, rapidly, and at scale.

It is important to reiterate that achieving 1.5 C is the most difficult pathway sought by the Paris Agreement, one that several analyses have indicated has a low likelihood of success (Raftery et al., 2017; World Meteorological Organization, Citation2021; Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, 2021) because of the complex technological, economic, political, and social challenges to overcome in such a short period of time. The journey to NZ will be uncertain and unlikely to be orderly in some regions and sectors. Many governments are not likely to closely follow the IEA NZ roadmap and may pursue different strategies and milestones, as there are many possible pathways to achieve NZ by 2050. Regardless, there is no avoiding the challenges and implications of the net-zero transition, for it is assured that governments and industry will continue to pursue this common agenda, if only at a somewhat slower pace. It is also vital to reinforce that while the costs and disruption of the NZ transition will be significant for society and for tourism, as IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (Citation2018) and the leaked version of the upcoming IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (The Guardian, 2021c) makes abundantly clear, they absolutely pale in comparison to those associated with higher emission futures.

Achieving the IEA NZ scenario or any other NZ scenario would require tourism to reinvent itself at both global and destination scales, requiring major and immediate upsurge in research and innovation, new cross-sector integrated and internationally co-operative policy innovation, novel demand management strategies, and a massive ongoing investment in infrastructure and technology deployment. The incoherence of tourism and climate policy at national and international scales (Gössling & Lyle, [Citation2021] and Becken et al., [Citation2020]) is an increasing vulnerability for tourism development. If the IEA roadmap is supported through the massive policy interventions it would require, the implications for future tourism development, the distribution of global tourism, and destination competitiveness are nothing short of transformative.

The tourism sector’s Glasgow Declaration: A Commitment to a Decade of Tourism Climate Action does not discuss potential transition risks or articulate a process by which these may be better understood and ameliorated. Getting to net-zero will be as disruptive for tourism as the internet was and will introduce conflicts and trade-offs with tourism development, and these remain to be acknowledged and unpacked. While the Declaration recognizes the importance of collaboration, it does not outline how that could be enhanced, such as a commitment to establish a ‘Tourism Net-zero Advisory Committee’ to develop credible NZ pathways at the global or regional scale. The Declaration also does not support OECD and academic calls for the removal of fossil fuel subsidies and the taxation of greenhouse gas emissions (Chepeliev & van der Mensbrugghe, Citation2020; Elgouacem, Citation2020). There is also no provision for the assessment of the implications of diverse policy proposals.

The sector was able to mobilize immediately to form the Global Tourism Crisis Committee in the face of the Covid-19 crisis. The climate crisis demands no less. The net-zero advisory bodies created by the UK, France, New Zealand, and Canada offer some excellent advice for the tourism sector to build on as part of their post-Glasgow Declaration action agenda (Net-Zero Advisory Body, 2021): (1) Collaborate across the sector (government, private sector, destination communities, tourists) and with other sectors on policy, research and development, investment, and engagement. (2) Develop a collective vision of tourism in the net-zero economy of mid-century and identify the many opportunities and co-benefits for tourism businesses, destinations, and tourists of advancing that vision. (3) Act early and urgently; the illusion of time to act is behind us. (4) Recognize and assess the regional differences, both in transition risk and strategies to decarbonize tourism, to advance a just transition. (5) Prioritize strategies and pathways that utilize solutions that are already available at scale and do not rely on immature solutions that may or may not be realized or in the timeframes required. (6) Understand the liabilities of solutions that may provide near term gains, but do not provide a secure path to deeper reductions required by the net-zero economy (e.g., Scott et al., [Citation2015] warned against a strategy of relying on the uncertain quality, availability, and costs of carbon offsets). (7) Beware of the ‘net’ in net-zero. Negative emissions technologies remain prohibitively expensive and are not proven at scale (Haikola et al., Citation2021; Temple, Citation2021), ecosystem-based strategies have been often overestimated (Friedlingstein et al., Citation2019) and a recent study found that offsetting CO2 emissions with negative emissions of the same magnitude would nonetheless result in greater warming than if CO2 emissions were avoided because of alterations to terrestrial and ocean CO2 releases (Zickfeld et al., Citation2021). This also reinforces the importance of putting a global price on carbon, as costing carbon at significant levels (consistent with or exceeding the IEA NZ scenarios) will remain one of the most efficient mitigation strategies because it forces the market to devise its own solutions.

The IEA NZ scenario and the societal transformation it implies, compels a critical research agenda to determine how the central strategies and assumptions of such scenarios that are germane to tourism could be achieved, develop new methods and information sources to understand the scope and scale of transition risk in order to inform policy innovation that might support a just transition in tourism sector, and the implications of achieving the scenario for tourism development and pursuit of the SDGs (and their post-2030 replacements). To accomplish this requires tourism scholars to reprioritize their research agenda, with less than 4% of research published in top 5 tourism journals from 2000 to 2019 dedicated to climate change (Scott, Citation2021). Such a major transition was accomplished with a rapid increase in research to address the informational needs of the Covid-19 pandemic. The climate crisis demands the same urgent mobilization of tourism expertise, as global tourism will be changed significantly by both the NZ transition and the wide-ranging impacts of accelerating changes in climate.

Finally, let us be definitive in our call for urgent climate action in the tourism sector. While the NZ transition will be disruptive for some tourism businesses and destinations, a + 3 C or warmer world will be far more disruptive, and in many cases devastating, for tourism. It is crucial that tourism develop strategies to accelerate its decarbonization and a vision of the place of tourism in a NZ society. The knowledge and business case to act on emissions is already available for businesses and destinations, while work on emission tracking/indicators and their adoption, transition effects on tourism employment and social stability, and the development of alternative business models in the NZ economy all need greater attention. Growth strategies and market segments will have to be evaluated against the potential for emission reductions compatible with NZ future, and some forms of tourism will, due to their energy-intensity, simply no longer be viable. Net-zero carbon is now, and will remain, the new policy and planning imperative for everyone working in tourism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Air Transport Action Group. (2021). Waypoint 2050. https://aviationbenefits.org/media/167187/w2050_full.pdf

- Arup, Gleeds, IHG Hotels and Resorts, and Schneider Electric. (2021). Transforming existing hotels to net zero carbon. https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/transforming-existing-hotels-to-net-zero-carbon

- Bank for International Settlements. ( 2020). The green swan: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp31.pdf

- BBC. (2021). German climate change law violates rights, court rules. 29 April 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56927010

- Becken, S., Whittlesea, E., Loehr, J., & Scott, D. (2020). Tourism and climate change: Evaluating the extent of policy integration. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1603–1624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1745217

- Carbon Brief. (2021). Coronavirus: Tracking how the world’s ‘green recovery’ plans aim to cut emissions. https://www.carbonbrief.org/coronavirus-tracking-how-the-worlds-green-recovery-plans-aim-to-cut-emissions

- Chepeliev, M., & van der Mensbrugghe, D. (2020). Global fossil-fuel subsidy reform and Paris Agreement. Energy Economics, 85, 104598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104598

- Climate Case Chart. (2021). Climate change litigation databases. wwwclimatecasechart.com

- Cohen, S. A., & Higham, J. (2011). Eyes wide shut? UK consumer perceptions on aviation climate impacts and travel decisions to New Zealand. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683501003653387

- Cruise Lines International Association. (2018). Cruise industry commits to reduce the rate of carbon emissions globally by 40 percent by 2030. https://cruising.org/en/news-and-research/press-room/2018/december/clia-emissions-commitment-release

- Cruise Lines International Association. (2020). State of the Cruise Industry Outlook – 2020.

- Deloitte. (2020). Electric vehicles setting a course for 2030. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/future-of-mobility/electric-vehicle-trends-2030.html

- Dibene-Arriola, L. M., Carrillo-González, F. M., Quijas, S., & Rodríguez-Uribe, M. C. (2021). Energy efficiency indicators for hotel buildings. Sustainability, 13(4), 1754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041754

- Elgouacem, A. (2020). Designing fossil fuel subsidy reforms in OECD and G20 countries: A robust sequential approach methodology. OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 168, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/d888f461-en.

- Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU). ( 2021). Taking stock: A global assessment of net zero targets. https://eciu.net/analysis/reports/2021/taking-stock-assessment-net-zero-targets

- 'European Council (2021)' can be removed. this was reported in many media outlets and is common knowledge now.

- Friedlingstein, P., Allen, M., Canadell, J. G., Peters, G. P., & Seneviratne, S. I. (2019). Comment on “The global tree restoration potential”. Science, 366(6463). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay8060

- Friedlingstein, P., O'Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Sitch, S., Le Quéré, C., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S., Aragão, L. E. O. C., Arneth, A., Arora, V., Bates, N. R., … Zaehle, S. (2020). Global carbon budget 2020. Earth System Science Data, 12(4), 3269–3340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020

- Galvani, A., Lew, A. A., & Sotelo Perez, M. (2020). COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 567–576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760924

- Gössling, S. (2011). Carbon management in tourism. Routledge.

- Gössling, S., Humpe, A., & Bausch, T. (2020b). Does 'flight shame' affect social norms? Changing perspectives on the desirability of air travel in Germany. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266, 122015. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122015

- Gössling, S., Humpe, A., Fichert, F., & Creutzig, F. (2021a). COVID-19 and pathways to low-carbon air transport until 2050. Environmental Research Letters, 16(3), 034063. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abe90b

- Gössling, S., & Lyle, C. (2021). Transition policies for climatically sustainable aviation. Transport Reviews, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1938284

- Gössling, S., Meyer-Habighorst, C., & Humpe, A. (2021b). A global review of marine air pollution policies, their scope and effectiveness. Ocean and Coastal Management. 212. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964569121003070

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism's global environmental impact 1900–2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(5), 639–659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1008500

- Gössling, S., & Scott, D. (2018). The decarbonisation impasse: Global tourism leaders’ views on climate change mitigation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(12), 2071–2086. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1529770

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., Hall, M.C., Ceron, J.P., Dubious, G (2012) Consumer Behaviour and Demand Response of Tourists to Climate Change. Annals of Tourism Research, 39 (1), 36–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.11.002

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2013). Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. WIREs Climate Change, 4(6), 525–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.243

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2015). Inter-market variability in CO2 emission-intensity in tourism: Insights for energy policy and carbon management. Tourism Management, 46(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.06.021

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020a). Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Haikola, S., Anshelm, J., & Hansson, A. (2021). Limits to climate action-narratives of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. Political Geography, 88, 102416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102416

- Hall, C.M, Gössling, S., Scott, D. (2020) Pandemics, Transformations and Tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Hardisty, D. J., Beall, A. T., Lubowski, R., Petsonk, A., & Romero-Canyas, R. (2019). A carbon price by another name may seem sweeter: Consumers prefer upstream offsets to downstream taxes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 66, 101342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101342

- Hepburn, C., O’Callaghan, B., Stern, N., Stiglitz, J., & Zenghelis, D. (2020). Will COVID-19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change? Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Supplement_1), S359–S381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa015

- Higham, J., Cohen, S. A., Cavaliere, C. T., Reis, A., & Finkler, W. (2016). Climate change, tourist air travel and radical emissions reduction. Journal of Cleaner Production, 111, 336–347. https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/state-of-the-cruise-industry.pdf https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.100

- Higham, J., & Font, X. (2020). Decarbonising academia: Confronting our climate hypocrisy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1695132

- IATA. (2019). Economic performance of the airline industry. https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/airline-industry-economic-performance–-december-2019–-report/

- IATA. (2020). Best practices for COVID-19 market stimulation. https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-12-08-02/

- ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization). (2016). Environmental Report 2016 - Aviation and Climate Change. https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/Documents/ICAO%20Environmental%20Report%202016.pdf

- ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization. (2019). Assembly – 40th session: Agenda Item 16: Environmental Protection – International Aviation and Climate Change — Policy and Standardization. https://www.icao.int/Meetings/a40/Documents/WP/wp_561_en.pdf

- Idea Works. (2020). The journey ahead: How the pandemic and technology will change airline business travel. https://ideaworkscompany.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Journey-Ahead-Airline-Business.pdf

- IEA (International Energy Agency. (2021). Net zero by 2050. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

- IHS Markit. (2021). Global electric vehicle sales grew 41% in 2020, more growth coming through decade. https://ihsmarkit.com/research-analysis/global-electric-vehicle-sales-grew-41-in-2020-more-growth-comi.html

- International Council on Clean Transportation. ( 2021) Estimating sustainable aviation fuel feedstock availability to meet growing European Union demand. https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Sustainable-aviation-fuel-feedstock-eu-mar2021.pdf

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global warming of 1.5 °C (An IPCC special report). World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

- International Tourism Partnership. (2017). HOTEL GLOBAL DECARBONISATION REPORT: Aligning the sector with the Paris Climate Agreement towards 2030 and 2050. https://buildingtransparency-live-87c7ea3ad4714-809eeaa.divio-media.com/filer_public/c4/9c/c49c0756-d91b-43b6-9819-6f4a2215052b/wc_am-hoteldecarbonizationreportpdf.pdf

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763445

- Kallbekken, S., & Saelen, H. (2021). Public support for air travel restrictions to address COVID-19 or climate change. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 93, 102767. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.102767

- Klöwer, M., Hopkins, D., Allen, M., & Higham, J. (2020). An analysis of ways to decarbonize conference travel after COVID-19. Nature, 583(7816), 356–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02057-2

- Krantz, R. (2020). The scale of investment needed to decarbonize international shipping. https://www.globalmaritimeforum.org/content/2020/01/Getting-to-Zero-Coalition_Insight-brief_Scale-of-investment.pdf

- Lee, David & Fahey, D & Skowron, Agnieszka & Allen, M & Burkhardt, U & Chen, Q. & Doherty, S & Freeman, S & Forster, Piers & Fuglestvedt, J & Gettelman, A & Rodriguez De Leon, Ruben & Lim, Ling & Lund, Marianne & Millar, R & Owen, Bethan & Penner, Joyce & Pitari, G & Prather, Michael & Wilcox, Laura. (2020). The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmospheric environment (Oxford, England: 1994). 244. 117834. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117834.

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

- Markham, F., Young, M., Reis, A., & Higham, J. (2018). Does carbon pricing reduce air travel? Evidence from the Australian ‘Clean Energy Future’ policy, July 2012 to June 2014. Journal of Transport Geography, 70(2018), 206–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.06.008

- Mediterranean Shipping Agency. (2021). Go neutral with us. https://www.msc.com/che/sustainability/msc-carbon-neutral-programme

- Ministry of Transport BW. (2021). Klimaschutz und Mobilität. https://vm.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/politik-zukunft/nachhaltige-mobilitaet/klimaschutz-und-mobilitaet/

- Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union. (2020). Cruise rankings 2020. https://www.nabu.de/umwelt-und-ressourcen/verkehr/schifffahrt/kreuzschifffahrt/28642.html

- Net-Zero Advisory Body (2021) Net-Zero Pathways Initial Observations June 2021. Available at: https://ehq-production-canada.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/9e3bb1476e46e10b839309c4eb5c6dae3a674e48/original/1624044169/9fce922e91ab369313cf4caffe773e79_NZAB_-_Summary_-_Pathways_to_Net-Zero_-_EN.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAIBJCUKKD4ZO4WUUA%2F20210803%2Fca-central-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20210803T173727Z&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=78ede59ace0226ced9f7dbf170f40151be1ed369016864a4d49949db4545fc71

- New York Times. (2021). A big climate problem with few easy solutions: Planes. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/business/energy-environment/airlines-climate-planes-emissions.html

- Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). (2021, May 14). Few realistic scenarios left to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/05/210514134042.htm

- Raftery, A. E., Zimmer, A., Frierson, D. M., Startz, R., & Liu, P. (2017). Less than 2 C warming by 2100 unlikely. Nature Climate Change, 7(9), 637–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3352

- Reuters. ( 2020, March 10). Ban short-haul flights for climate? In EU poll 62% say yes. Reuters. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-eu-flights-idUSKBN20X2RA

- Royal Society. (2020). Ammonia: Zero-carbon fertilizer, fuel and energy store. https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/green-ammonia/green-ammonia-policy-briefing.pdf

- Scheelhaase, J., Maertens, S., & Grimme, W. (2019). Synthetic fuels in aviation–Current barriers and potential political measures. Transportation Research Procedia, 43, 21–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2019.12.015

- Scott, D., Amelung, B., Becken, S., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., Gössling, S., Peeters, P., & Simpson, M. (2008). Climate change and tourism: Responding to global challenges (Technical report). UNWTO, 25–256.

- Scott, D. (2021). Sustainable Tourism and the Grand Challenge of Climate Change. Sustainability, 13(4), 1966. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041966

- Scott, D., Gössling, S., Hall, C.M. (2012) International Tourism and Climate Change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews – Climate Change, 3 (3), 213–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.165

- Scott, D., Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., & Peeters, P. (2015). Can tourism be part of the decarbonized global economy?: The costs and risks of alternate carbon reduction policy pathways. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(1), 1–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1107080

- Scott, D., Peeters, P., & Gössling, S. (2010). Can tourism deliver its ‘aspirational’ emission reduction targets? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 393– 408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653542

- Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2018). Tourism and climate change mitigation: Embracing the Paris agreement – pathways to decarbonization. European Travel Commission.

- Scott, D., Hall, C.M., Gössling, S. (2019) Global Tourism Vulnerability to Climate Change. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 49–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.007

- Seetaram, N., Song, H., & Page, S. J. (2014). Air passenger duty and outbound tourism demand from the United Kingdom. Journal of Travel Research, 201453(4), 476–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513500389

- Simonsen, Morten & Gössling, Stefan & Walnum, Hans Jakob. (2019). Simonsen et al. 2019 ResearchGate. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.05.014

- Skift. (2021). Expect climate change to finally drive more corp travel decisions post-pandemic. https://skift.com/2021/06/14/expect-climate-change-to-finally-drive-more-corp-travel-decisions-post-pandemic/

- Sonnenschein, J., & Smedby, N. (2019). Designing air ticket taxes for climate change mitigation: Insights from a Swedish valuation study. Climate Policy, 19(5), 651–663. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1547678

- Sun, Y. Y., Higham, J. (2021) Overcoming information asymmetry in tourism carbon management: The application of a new reporting architecture to Aotearoa New Zealand. Tourism Management, 83, 104231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104231.

- Temple, J. (2021). Carbon removal hype is becoming a dangerous distraction. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/07/08/1027908/carbon-removal-hype-is-a-dangerous-distraction-climate-change/

- The Guardian. (2021a). Interview: António Guterres on the climate crisis: ‘We are coming to a point of no return’. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/11/antonio-guterres-interview-climate-crisis-pandemic-g7

- The Guardian. (2021b). ‘Black Wednesday’ for big oil as courtrooms and boardrooms turn on industry. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/may/29/black-wednesday-for-big-oil-as-courtrooms-and-boardrooms-turn-on-industry

- The Guardian. (2021c). IPCC steps up warning on climate tipping points in leaked draft report. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/23/climate-change-dangerous-thresholds-un-report

- UN. (2015). Paris agreement. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

- UNDESA. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/

- UNEP. (2020). Emissions Gap Report 2020. https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2020

- United Nations World Tourism Organization, United Nations Environment Programme, and the World Meteorological Organization. (2008). Climate change and tourism – Responding to global challenges. UNWTO. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284412341

- United Nations World Tourism Organization and International Transport Forum (2019) Transport-related CO2 emissions of the tourism sector – Modelling results. UNWTO. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284416660

- UNWTO. (2021). Climate action. https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development/climate-action

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (2021) Glasgow declaration: A commitment to a decade of tourism climate action. UNWTO. https://www.unwto.org/news/the-glasgow-declaration-an-urgent-global-call-for-commitment-to-a-decade-of-climate-action-in-tourism

- World Bank. (2021). Hidden debt: Solutions to avert the next financial crisis in South Asia. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/sar/publication/south-asia-hidden-debt

- World Meteorological Organization. (2021). New climate predictions increase likelihood of temporarily reaching 1.5 °C in next 5 years. https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/new-climate-predictions-increase-likelihood-of-temporarily-reaching-15-%C2%B0c-next-5

- WTTC. (2017). Understanding the critical issues for the future of travel and tourism. https://www.wttc.org/tourism-for-tomorrow-awards/newsletter/2017/march-2017/

- WTTC. (2018). World travel & tourism industry pledges climate neutrality. https://unfccc.int/news/world-travel-tourism-industry-pledges-climate-neutrality

- Zickfeld, K., Azevedo, D., Mathesius, S., & Matthews, H. D. (2021). Asymmetry in the climate–carbon cycle response to positive and negative CO2 emissions. Nature Climate Change, 11, 613–617.