?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The economic effects of tourism industry during periods of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have received significant attention in recent years. The future is likely to pose a range of new challenges and opportunities to sustainable tourism. This paper employs the Markov-switching vector autoregressions (MSVAR) model to investigate the sustainability of tourism’s economic effects in Hong Kong, both during periods of crisis and in the absence of crises. The empirical results show that: (1) The MSVAR model is effective in capturing the nonlinear relationship between the economy and tourism and allows for the categorizing of this relationship into four regimes, for example, the “major event crises” regime and the “economic crises” regime; (2) The economic effects of tourism differ noticeably across the four different regimes, and sustainability varies depending on the presence and type of crisis; (3) The Hong Kong economy, and the tourism industry in particular, exhibits high levels of stability and sustainability. In short, economic growth in Hong Kong’s tourism industry is capable of rapid recovery following major crisis events, and it has the capacity to rebound quickly into new periods of rapid growth.

Introduction

In recent decades, tourism has become one of the largest and fastest growing industries in the global economy. The tourism industry not only stimulates industry, fosters investment, and leads to increased consumption and income levels; it also plays an irreplaceable role in promoting employment and improving people’s quality of life (Andereck & Nyaupane, Citation2011; Sharpley, Citation2014). This is why tourism is considered by countries all over the world as one of the vital driving forces behind the stimulation of regional economic growth and industrial upgrading. According to statistics from the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC, Citation2019a), in 2019, the tourism industry generated around 334 million jobs globally and, combining direct, indirect, and induced effects accounted for 10.4% of global GDP. Hong Kong is a leading destination of world tourism, enjoying both national and international prominence. As one of the four pillar industries in Hong Kong, tourism plays an irreplaceable role in promoting Hong Kong’s economic development (Li et al., Citation2013). Tourism can affect economic activity through numerous different channels. For example, it generates jobs, tax revenues, a healthy flow of foreign currency, tourism-related investment, and consumption (Sinclair, Citation1998). Prior to the pandemic, the travel and tourism economy (including direct, indirect, and induced effects) accounted for 14.9% of all jobs in Hong Kong, and 12.3% of the region’s total economy (WTTC, Citation2019b). Meanwhile, international visitor spending in 2019 amounted to 288.7 billion Hong Kong dollars (5.8% of total exports).

However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has had a catastrophic impact on the tourism industry. Since its detection, the expansion of COVID-19 has had various wide-ranging and long-term impacts on people around the world. The pandemic has reached practically every country in the world and has affected the lives of millions of people. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have been more severe than those of global financial shocks (Rodríguez-Antón & Alonso-Almeida, Citation2020). Whereas the latter only suppress people’s desire to travel, the pandemic has forcibly halted global travel, tourism, and leisure activities as a direct consequence of government restrictions designed to limit face-to-face activities so as to stop the spread of the disease. Like many tourist destinations, Hong Kong has also experienced significant negative effects as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recently, there has been growing academic recognition of the importance of investigating, measuring, and predicting the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism industry (Mariolis et al., Citation2020; Sharma & Nicolau, Citation2020; Ye & Law, Citation2021). Over the course of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have focused on investigating the promotion and recovery of tourism (Rodríguez-Antón & Alonso-Almeida, Citation2020; Sigala, Citation2020), social cost analysis (Qiu et al., Citation2020), the impact of the pandemic on hotel employees’ health and safety (Sonmez et al., Citation2020), and the government’s role in the recovery of the tourism industry (König & Winkler, Citation2020).

In addition to the current COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism industry in Hong Kong has previously been negatively affected by various crises, such as SARS, economic crises, and the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests. Against this background of recurring crises, it is becoming increasingly important to understand how these crises affect the tourism industry and to come up with effective means for measuring changes and trends in the tourism market. According to the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) implemented by the United Nations, sustainable tourism is regarded as one of the key targets to “promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth” (UN, Citation2016). The sustainability of tourism’s economic effects refers to a state in which the tourism industry will maintain a positive effect on economic development, and which can be sustained for a long time. However, the sustainable development of Hong Kong’s tourism sector has been challenged by various crises. One common characteristic of all the crises that have affected Hong Kong is their negative impact on tourism activities, leading to damaging volatility in the performance of the industry (Steiner, Citation2007). Nevertheless, the impact of crises depends on their nature, size, frequency, duration, and severity (Alexander & Alexander, Citation2000). Most previous studies that have investigated the economic effects on tourism during a crisis have focused on the impact of a specific crisis in a specific region. There has, to date, been little research that has focused on the longer-term influences of crises on the tourism industry.

The major aim of this study is to investigate the ways in which both a crisis’s presence and type impact the economic effects of tourism in Hong Kong. To achieve this goal, we will use the MSVAR model to divide the historical data relating to economic growth and tourism growth into different regimes: “negative growth, high risk (NG-HR),” “high growth, low risk (HG-LR),” “moderate growth, low risk (MG-LR),” and “moderate growth, high risk (MG-HR),” and will then analyze economic effects under the conditions of each regime.

The present study contributes to the existing scholarly literature on this subject in multiple ways. First, it enriches the extant literature on tourism’s economic effects by investigating the economic effects of tourism in the presence of different kinds of crises. Previous studies have targeted a specific crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, in a specific region without considering the differences between different kinds of crises. Second, the present study differs methodologically from former research methods that have been employed to measure tourism’s economic effects, such as tourism multipliers (Archer, Citation1973; Ntibanyurwa, Citation2010), the input-output model (Klijs et al., Citation2015; Tohmo, Citation2018), and the Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSA) method (Kenneally & Jakee, Citation2012; Yu et al., Citation2019). By employing the non-linear econometric method of MSVAR, this study offers a new perspective for exploring the economic effects of tourism. The specification of multiple regimes with regime-dependent intercept terms (I) and heteroscedasticity (H) in our research, named MSIH (4)-VAR (3), is used to effectively capture the influence of a crisis on the economic effects of tourism and explore the relationship between the development of the tourism industry and the economy in the presence of different kinds of crisis. Lastly, against the background of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, this study provides an estimation of future development trends for Hong Kong’s economy and tourism sector and offers valuable insights into the sustainability of tourism’s economic effects under different regimes.

Literature review

In the field of tourism economics, a vast amount of literature has been devoted to investigating the relationship between economic development and the tourism industry. There are four main hypotheses about the relationship between tourism and economic growth. The first hypothesis is the tourism-led economic growth hypothesis (TLEGH), which asserts that tourism is a major driver of economic growth (Gunter et al., Citation2017; Lei et al., Citation2021; Narayan et al., Citation2010; Su et al., Citation2021; Tang & Tan, Citation2015). Proponents of this hypothesis have suggested that the expansion of tourism makes a positive contribution to the economic growth of a country/region through various channels, both direct and indirect. First, the consumption of tourists provides direct revenues to other economic sectors such as transportation, entertainment, hotels, and food (Mayer & Vogt, Citation2016). Second, the tourism industry generates jobs and has an important role in increasing the income level of the county/region (Khalil et al., 2007). Finally, as these direct and indirect beneficiaries tend to spend their extra income on further developing their activities, the expansion of tourism tends to have a magnified effect on the economy.

The second hypothesis is the economy-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTGH), which considers that economic growth determines tourism growth (Martins et al., Citation2017; Oh, Citation2005; Payne & Mervar, Citation2010; Tsui, Citation2017). This is because economic prosperity leads to the increase of the resources available for tourism infrastructure development and for the provision of better services for tourists. The third hypothesis proposes that a bidirectional relationship exists between economic growth and tourism (Bilen et al., Citation2017; Gao et al., Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2006; Seetanah, Citation2011; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2020). Finally, some studies propose no causal relationship between them (Ozturk & Acaravci, Citation2009; Tang & Jang, Citation2009).

A number of studies have attempted to analyze the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth, but researchers have reached inconsistent or even contradictory results. This is partly due to differences in the country/region looked at, period focused on, methods used, variables selected, and data included. In recent years, there has been increasing interest in investigations into this relationship in heterogeneous, nonlinear, time-varying circumstances. For instance, based on a non-parametric, non-linear approach, Brida et al. (Citation2020) find that there is heterogeneity in the relationship between tourism and economic growth. Gunter et al. (Citation2017) find that international tourism has a highly significant impact on economic development in Central America and the Caribbean. Conversely, Tsui (Citation2017) finds evidence that supports the EDTGH in New Zealand. Wu et al. (Citation2016) use a panel smooth transition vector error correction model to support their argument that the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth is nonlinear and time-varying, in both the short term and the long term. As the effects of tourism on economic growth adhere to the law of diminishing returns, the relationship between them cannot be strictly linear (Ridderstaat et al., Citation2014). The main disadvantage of a linear framework is that it may oversimplify the relationship and neglect aspects that are complex and nonlinear (Wang, Citation2012). For example, tourism demand can lead to improvements in people’s quality of life (Fu et al., Citation2020). However, overtourism causes a negative cointegration relationship with residents’ sentiment (Cheung & Li, Citation2019; Oklevik et al., Citation2019).

In addition, it has previously been observed that the relationship between tourism and economic growth is unstable in terms of magnitude and direction, which are highly dependent on economic and tourism events (Antonakakis et al., Citation2015; Liu & Song, Citation2018). Chatziantoniou et al. (Citation2013) find that the impact of oil price fluctuations has a lagging effect on the economic growth generated by the tourism industry. Antonakakis et al. (Citation2015) use a newly introduced spillover index to analyze the dynamic interactions between tourism growth and economic growth. Their results indicate that the relationship between them was affected by both the Great Recession of 2007 and the Eurozone debt crisis. A study conducted by Liu et al. (Citation2020) shows that economic policy uncertainty has an important negative effect on the relationship since businesses tend to reduce their investment in tourism during times when there is increasing uncertainty over economic policy. Wu et al. (Citation2016) find that the causality also depends on the level of real interest rates. These researches demonstrate the impact of many elements on the economic effects of tourism. So, what has been said about the impact of crises?

Tourism is an extremely sensitive and highly vulnerable industry (Li et al., Citation2010). Recently, there has been a considerable number of studies that have addressed the impact that crises have on the tourism industry. The effects of financial and economic crises on tourism have long been a question of great interest among scholars working in a wide range of fields (Eugenio-Martin & Campos-Soria, Citation2014; Haque & Haque, Citation2018; Okumus & Karamustafa, Citation2005; Ritchie, Citation2004; Rontos et al., Citation2017). In light of recent events related to COVID-19, it is becoming extremely difficult to ignore the existence of contagious disease (Choe et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Lim & To, Citation2021; Mao et al., Citation2010; McCartney et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021). Researchers have conducted various studies into the impact of natural disasters (Cole et al., Citation2021; Faisal et al., Citation2020; Min et al., Citation2020), terrorism (Anderson, Citation2006; Arana & Leon, Citation2008; Avraham, Citation2016; Goodrich, Citation2002; Hanon & Wang, Citation2020; Sonmez, Citation1998), and political instability (Álvarez-Díaz et al., Citation2019; Ivanov et al., Citation2017; Perles-Ribes et al., Citation2019; Sonmez, Citation1998; Yap & Saha, Citation2013). Another important focus of research has been the recovery and development of the tourism sector following major crises (Backer & Ritchie, Citation2017). However, most previous studies in this area share a common limitation, which is their exclusive focus on a single, particular crisis.

A common effect of all kinds of crises is that they generate high levels of uncertainty and thus lead to a reduction in the number of tourists. An economic crisis reduces the disposable income of many households for a considerable period, which in turn has a negative impact on tourism spending power. Crises that arise as a result of public health events, such as SARS and COVID-19, result in a more severe decrease in tourist numbers and have significant socio-economic repercussions that result from the imposition of prophylactic measures such as distancing rules and social isolation (Rodríguez-Antón & Alonso-Almeida, Citation2020). In the short term, the impact of crises on the tourism industry includes a decline in the number of tourists, an increase in unemployment, and a decrease in profits, investment, and government revenue (Henderson, Citation2007). Crises also result in very severe medium-term effects for businesses dependent on the tourism industry, including increased difficulties in collecting loans, the postponing of future investment plans, difficulties in paying debts, and so on (Okumus et al., Citation2005). These sorts of difficulties can thrust a country/region into a fragile state of deterioration (Novelli et al., Citation2012). Clearly, therefore, the increasingly frequent occurrence of various crises and disasters challenges the sustainability of tourism development and its contribution to a destination’s economic growth. A fuller understanding of the complex nonlinear relationship between tourism and economic growth is thus necessary and will have important policy implications.

Methods and data

MSVAR model

In this study, we use the MSVAR model proposed by Krolzig (Citation1997) to assess the economic effects of tourism under different regimes. As a combination of the Markov-switching model and the vector autoregression (VAR) model, the MSVAR model is applied to identify different regimes, characterize the nonlinear relationship between economic variables, and reveal the different characteristics and laws of economic behavior in different states.

The most general specification of the MSVAR model of order p and M regimes can be defined as below:

(1)

(1)

where

the intercept, the autoregressive parameters, and the heteroscedasticity are conditioned on the regime.

Model selection

The form of MSVAR means that it allows for a great variety of specifications. To select the optimal model for our research, we construct a series of MSVAR models with different specifications (Markov-switching mean (M), intercept term (I), autoregressive parameters (A), heteroscedasticity (H)), regimes (2, 3, 4), and orders (1, 2, 3). Moreover, we test the stability of each model through eigenvalues of the companion matrix. In consideration of the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Schwarz information criterion (SIC) and Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQ), and the stability of models, the MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model is the one best suited to the empirical conditions of the present study. The MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model divides the series into four regimes and the intercept term and heteroscedasticity are regime-dependent. It can be written in the following form:

(2)

(2)

where

represents the growth rate of GDP and visitor arrivals (hereinafter, VA) in quarter t, and

is the variance-covariance matrix depends on the regime

, where

represents the four different regimes. In this model, when there is a switch in the regime, the specification of the model will change accordingly.

Before commencing analysis with the MSVAR model, we conducted a Granger causality test (Granger, Citation1969) to explore the relationship between economic growth and tourism. Based on the estimation results of the MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model, we performed both regime analysis and impulse response analysis for each regime of the model to further research the economic effects of tourism in the presence or absence of different kinds of crises.

Data description and stationarity tests

To analyze the economic effects of tourism, we use Hong Kong’s quarterly real GDP (constant price) and VA to represent the situation in terms of economic growth and tourism growth, respectively. GDP data for the first quarter of 1973 to the last quarter of 2020 are available from the Hong Kong SAR Government’s Census and Statistics Department website. The VA data for the same period is obtained from the Hong Kong Tourism Board website.

Since GDP and VA data have strong seasonality, the X-12 method is used for seasonal adjustment firstly, and the data are logarithmically processed, which are denoted as LN_GDP_SA and LN_VA_SA. To ensure the stability of the data, we employed the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test for the variables (Dickey & Fuller, Citation1979). As shown in , the null hypothesis was not rejected at the 10% significance level for the LN_GDP_SA and LN_VA_SA, but the first-order difference of each series passes the ADF test at the 1% confidence level. This suggests that the two series are stationary. Therefore, this paper uses the log difference form of quarterly real GDP and VA after seasonal adjustment, namely GDPg and VAg, which present the chain-based growth rate of output and the number of tourists for our remaining research. For a more detailed descriptive statistical analysis of the variables (mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation), please see .

Table 1. Descriptive statistical analysis and ADF unit root test.

Optimal lag order selection

In this paper, we construct a VAR model and use five information criteria to select the optimal lag order. As shown in , according to the various criteria, the optimal lag order is lag 3 when the maximum lag is equal to 3 or more. Therefore, the optimal lag order of GDPg and VAg is lag 3.

Table 2. Optimal VAR lag order selected by different criteria.

Empirical results and discussion

Granger causality tests

We adopt the Granger causality test to study the existence of the relationship between the two variables at lag order 3. The results are shown in . As can be seen from the results, the null hypothesis of “VAg does not Granger cause GDPg” cannot be rejected at the 5% confidence level, indicating that the hypothesis that the VAg in Hong Kong is the Granger cause of GDPg is not significant. Moreover, the other null hypothesis is accepted at the 1% level. The results suggest that GDPg is the Granger cause of VAg, which means there is a one-way Granger causality between GDPg and VAg.

Table 3. Granger causality test results.

This conclusion gives support to the EDTGH, which considers that economic growth determines tourism growth, but not to the TLEGH. It is also contradictory to the analysis of our research. The traditional Granger causality test examines the linear relationship between variables. However, economic variables are often affected by several elements, such as policies and crises. Additionally, the underlying relationship between tourism and economic growth is complex and nonlinear in nature. A linear test may, therefore, oversimplify it and lead to obvious deviations in the conclusion (Wang, Citation2012). To better explore the relationship between tourism and economic growth in different situations, in the present paper, we use the nonlinear MSVAR model with the characteristic of regime-switching.

The estimation results

presents the parameter estimation results of the MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model. As is made clear in , the GDPg and VAg series are divided into four regimes based on the different intercepts and standard deviations of residuals, namely “NG-HR,” “HG-LR,” “MG-LR,” and “MG-HR.” It should be noted that the high, moderate, and low growth regimes are defined based on the values of intercepts of both GDPg and VAg, while the high and low risk regimes are defined with reference to the standard deviation of GDPg, not necessarily consistent with that of VAg. The specific analysis will be given below.

Table 4. The estimation results and transition probability of MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model.

From the perspective of the intercept, the values for GDPg and VAg are both negative under the “NG-HR” regime, far lower than the level of growth under other regimes, which means that the development of the economy and tourism is in a recession phase. Under the “HG-LR” regime, the intercept values for GDPg and VAg both reached the maximum, indicating that the economy and tourism are both in the expansion phase. In the other two regimes, namely the “MG-LR” regime and the “MG-HR” regime, the intercept values for the two variables are relatively close, and both are at a relatively moderate level. The development of Hong Kong’s economy and tourism is at a moderate level at this stage. The significant coefficients of intercepts show the presence of switches between the four regimes. The results suggest that there is a relatively clear synchronization between Hong Kong’s economic growth and the development of tourism.

From the standpoint of the standard deviation, under the four regimes, the standard deviations of VAg are larger than those of GDPg, indicating that the fluctuation in the number of tourists is much greater than economic growth. This result is consistent with the real situation. The tourism industry has high sensitivity and vulnerability, and tourist numbers are susceptible to various factors, such as policies, emergencies, and crises (Brownell, Citation1990). Therefore, a higher fluctuation in tourism growth is in line with reality. In addition, VAg fluctuates significantly under both the “NG-HR” regime and the “HG-LR” regime. This is especially true in the case of the “NG-HR” regime, for which the standard deviation of VAg is as high as 172.0325, much larger than those of the “MG-LR” (2.5573) and “MG-HR” (3.0050) regimes. This suggests that the tourism industry has relatively high volatility, which means that it has a poor ability to resist external shocks in the recession and expansion phases. In the moderate growth stage of the “MG-LR” and “MG-HR” regimes, the volatility of VAg decreased significantly, compared with the “NG-HR” regime, indicating the strong stability of the tourism industry during the period of moderate growth. In addition, GDPg has a relatively large standard deviation during both the recession phase and the period corresponding to the “MG-HR” regime, which indicates that under these two regimes, the development of the economy is more volatile.

The estimation results of the autoregressive coefficients may seem confusing given that the VAg is negative to GDPg in the first and third order, which differs from reality. One possible explanation for this result is that the autoregressive coefficient of the MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model is invariant under different regimes, while an increase in the number of tourists may increase the severity of the epidemic and inhibit economic growth under the conditions of the resulting crisis. The impact of such crises is so large that it affects the estimation of other regimes.

Regime properties and classification

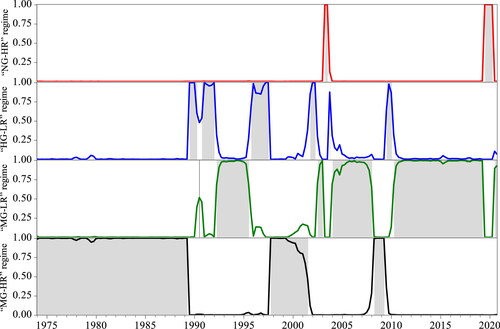

In the MSVAR model, the smoothed probability curve reflects the switches of GDPg and VAg under different regimes through probability distribution values. As shown in , the random walk trend of the smoothed probability curve between different regimes reflects the time-varying characteristics of the economy and tourism.

presents the specific regime classification. It can be seen that the “NG-HR” regime corresponds to two periods: the second quarter to the third quarter of 2003 and the third quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2020. Why is the growth of the economy and tourism negative in these two periods? The event corresponding to the former is the SARS epidemic that prevailed around 2003. In November 2002, the SARS epidemic broke out in Guangdong Province and Hong Kong, China, spreading rapidly across the whole country. The outbreak of the epidemic resulted in the imposition of restrictions on people’s freedom of movement. The tourism industry in Hong Kong was hit hard, and the number of tourists dropped sharply. During the latter period, two major incidents occurred in Hong Kong: the “2019–2020 Hong Kong protests” that broke out in June 2019, and the COVID-19 pandemic that spread to the city at the beginning of 2020 and the effects of which continue to be felt up to the present. In June 2019, protesters in Hong Kong carried out various radical resistance activities in response to plans to allow extradition to mainland China. Violent clashes between police and protesters ensued and escalated. The actions of the protesters, who claimed to be carrying out peaceful demonstrations, posed a significant threat to the social stability of Hong Kong and the personal safety of its people. In addition, since the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020, the disease has rapidly spread and has wreaked havoc in countries around the world. In an attempt to curb the spread of the pandemic, various countries and regions have enforced policies that restrict people’s movements. The Hong Kong government has also enforced compulsory quarantine and other restrictive measures for those entering Hong Kong in an attempt to lower the risk from imported cases. Many people, furthermore, have canceled or scaled back their travel plans in response to the current health and safety risks associated with travel. The global tourism industry has suffered a huge impact. As one of the four pillar industries in Hong Kong, the recession of the tourism industry has been a great shock to Hong Kong’s economy and has significantly retarded economic development. In addition, the impacts on everyday life of both the epidemic and of the riots that preceded it have triggered a recession and caused harmful fluctuations in Hong Kong’s economic activities.

Table 5. Regime classification.

The periods corresponding to the “HG-LR” regime are mainly pre and post major economic crises: Japan’s financial crisis in 1993, the Asian financial crisis in 1997, and the global financial crisis in 2008. In these periods, Hong Kong’s economy and tourism demonstrated a good momentum in development and maintained rapid growth. The period from the 1990s to the beginning of this century saw the completion of the structural transformation of Hong Kong’s economy and the agreement between China and Britain on the Hong Kong issue. Clarity was achieved in the matter of Hong Kong’s future, and the economy entered a stage of rapid development. At this stage, several economic crises and the SARS epidemic did exert some negative influence over Hong Kong’s economic growth. The economy nevertheless continued to achieve moderate levels of growth. Following the SARS epidemic, Hong Kong’s economy entered a period of moderate growth. It was not until the phase of economic recovery that followed the 2008 global financial crisis that the economy of Hong Kong resumed its short-term rapid development. At this stage, with the rapid development of Hong Kong’s economy, Hong Kong’s tourism industry also entered a stage of rapid development, and the number of visitors to the city increased significantly. From the 1990s, with the completion of economic restructuring, Hong Kong’s economy shifted from manufacturing to a trade-based service industry, and the tourism industry was further developed. It should be noted that since the return of Hong Kong in 1997, mainland China has been the principal source of tourists to Hong Kong. In July 2003, after the SARS epidemic had been brought under control, the government of China formally allowed travelers from mainland China to visit Hong Kong on an individual basis (Individual Visit Scheme). This measure was aimed at promoting the development of Hong Kong’s tourism industry and supporting the recovery of Hong Kong’s economy. The number of tourists to Hong Kong soared. The rapid development of tourism had an immediate rebound impact on Hong Kong’s economy. The economy, which had been stagnant due to the impact of the SARS epidemic, gradually returned to normal.

Under the “MG-LR” and “MG-HR” regimes, Hong Kong’s economy and tourism industry enter a stage of moderate development. The difference is that under the “MG-LR” regime, fluctuations in GDPg and VAg are relatively small, which indicates that the development is stable, while under the “MG-HR” regime, the GDPg of Hong Kong fluctuates greatly. Although it still belongs to the stage of moderate development, its ability to resist external shocks is weak. The “MG-HR” regime corresponds to three periods: the 1970s and 1980s, the fourth quarter of 1997 to the third quarter of 2001, and the second quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2009. During these periods, the economy fluctuated greatly, while the number of visitors fluctuated slightly. In the 1970s and 1980s, Hong Kong’s economy was undergoing a period of structural transformation. Due to the rapid northward movement of its manufacturing industry under the conditions of China’s reform and opening up, the rapid development of the service industry led by foreign trade transformed Hong Kong from a lightweight product processing and manufacturing center to a pivotal business service center in the Asia-Pacific region. A major economic restructuring was taking place during these years in Hong Kong. During this period, the economy of Hong Kong fluctuated greatly, and its ability to withstand shocks was weak. In addition, the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the global financial crisis in 2008 both impacted Hong Kong’s economic development. However, although Hong Kong’s economy fluctuated greatly during these stages, it still maintained a trend of considerable growth. The direct impact of the economic crises on Hong Kong was not significant. Under the conditions of the economic crises, Hong Kong still maintained a moderate growth rate. However, the occurrence of an economic crisis will lead to greater fluctuations in the Hong Kong economy, and the economy and the tourism industry will be less capable of resisting external shocks, which indicates greater risks in these periods.

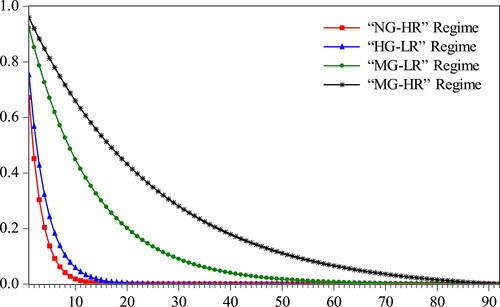

In the model, “transition probability” and “state duration” are used to reflect the transition probability and average duration of GDPg and VAg in different regimes. As shown in , from the perspective of transition probability, the highest probability, under all four regimes, is the state of maintaining the original regime. Among them, the probability of maintaining the original state in the moderate growth period (“MG-LR” and “MG-HR” regimes) is higher than 90%, indicating that the economy and tourism growth in Hong Kong are highly stable during the moderate growth period. In addition, the probability of the “NG-HR” regime becoming either the “HG-LR” or the “MG-LR” regimes are almost the same, both at 16%, while the probability of it turning into the “MG-HR” regime is very small. This suggests that when the negative economic growth phase of Hong Kong is over, it is more likely to turn to the “high growth, low risk” and “moderate growth, low risk” regimes during the recovery period. The prospects for the recovery of Hong Kong’s economy and tourism are relatively clear after the crisis. From the perspective of the state duration, the duration of the negative growth period and the high growth period is relatively short, with an average of the third and fourth quarters. The duration of the phase of moderate growth is much larger than the recession phase and the expansion phase. The average duration of the two periods of “moderate growth, low risk” and “moderate growth, high risk” is three years and six years, respectively. presents the probability of staying in the same regime of the four regimes after h periods, which provides corroboration of the analysis above. As shown in the figure, the probability of staying in the “NG-HR” and “HG-LR” regimes drop very rapidly, while the probability of moderate growth phases has a stronger persistence.

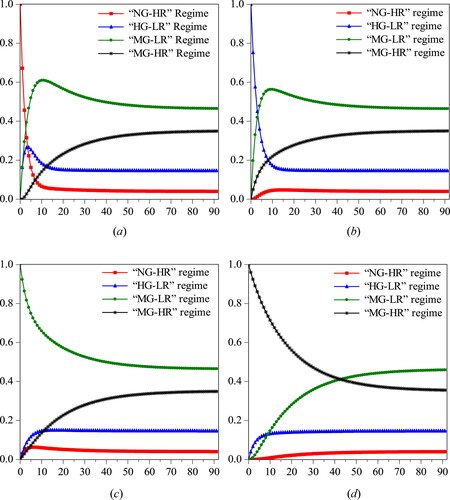

The results of the probability of switching to each regime under four regimes after h periods are shown in . With the increase in the number of periods, there are some differences between the variation of each regime. As can be seen from , after entering the negative growth period (“NG-HR” regime) for three quarters and four quarters, the probability of switching to the “MG-LR” regime and the “HG-LR” regime exceeds the probability of staying in the original regime respectively, and the probability of switching to the “MG-LR” regime is maintained at the highest level. Therefore, although crises caused by major public health incidents will have a huge shock on the economy and tourism growth in Hong Kong in the short term, the impact of such crises lasts for a relatively short time. Hong Kong tends to recover quickly from such crises and to move on to new rounds of rapid growth. While under the conditions of economic crises (“MG-HR” regime), as shown in , the probability of staying in the original regime drops slowly, while the probability of switching to the “MG-LR” regime does not exceed it until 40 quarters later. Comparison between the two regimes indicates that the impact of major event crises (which, in our case of Hong Kong, refer to the “2019–2020 Hong Kong protests” and major public health incidents) has a lower persistence than that of economic crises.

Figure 3. The probability of switching to the specific regime from four different regimes. (a) The probability of switching from the “NG-HR” regime. (b) The probability of switching from the “HG-LR” regime. (c) The probability of switching from the “MG-LR” regime. (d) The probability of switching from the “MG-HR” regime.

Importantly, we noticed that the negative growth phase of Hong Kong’s economy and tourism growth caused by the “2019–2020 Hong Kong protests” and the COVID-19 epidemic in Hong Kong lasted for four quarters, and this phase then turned into the “MG-LR” regime in the third quarter of 2020. This change is in line with our above analysis. In addition, the duration of the “MG-LR” regime is as long as 13 quarters, and the probability of switching to other regimes is very low. Combined with the results in , it can be seen that after Hong Kong enters the “MG-LR” regime, the probability of staying in the same regime remains highest over time. In the short run, the probability of switching to a high growth period of the “HG-LR” regime is second to the probability of maintaining the original regime, while the probability of switching to the negative growth of the “NG-HR” regime is always low. The analyses above indicate high sustainability of the economic effects of Hong Kong’s tourism development. Therefore, we believe that for a long period of time in the future, the economy and tourism development of Hong Kong will remain in a state of moderate growth and low risk, and may even enter a new round of rapid growth in the short run.

Regime-dependent impulse response

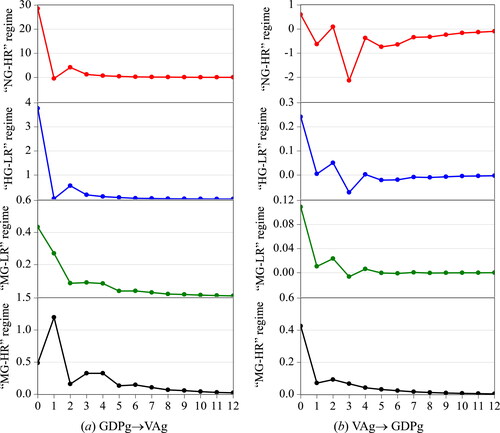

This paper uses orthogonal impulse responses to analyze the relationship between Hong Kong’s economy and tourism growth, and compared the differences in the short-term dynamic effects of different regimes. Based on the MSIH (4)-VAR (3) model, we give GDPg and VAg a positive shock of one standard deviation respectively, and observe the response results of GDPg and VAg in 12 quarters under the four regimes. presents the results of the impulse response.

It can be seen from that the impulse responses of VAg to GDPg’s shock remain positive in all four regimes, but the response intensity varies greatly under different regimes. The impact under the “NG-HR” regime is the most significant, while the impact under the “MG-LR” regime is the least significant. This indicates that the development of Hong Kong’s economy can bring an increase in the number of visitor arrivals, especially in a period of negative growth. Given a positive impact of one standard deviation to GDPg under the “NG-HR” and “HG-LR” regimes, the number of visitor arrivals has a positive response in the current period and reduced to 0 in the first period. It increased again in the second period and then decreased to 0 after the 5th when the effects of the response to the shock gradually fade. Under the “MG-LR” regime, the number of visitors has a positive response in the current period, and this positive response decreases gradually, dropping to 0 near the tenth period. Under the “MG-HR” regime, when a positive impact of one standard deviation of GDPg occurs, the number of tourists has a positive response in the current period, and the response reaches the maximum in the second period, decreasing to zero gradually. It can be seen from the analysis that improvement in Hong Kong’s economic growth has a more significant effect on promoting the development of the tourism industry during phases of negative growth and high growth, but their durations are shorter. In other words, it has a more obvious promotion effect in the short run. In the phase of moderate development, such promotion effect is less significant, but with stronger sustainability and lasting longer.

However, shows that the response of GDPg to VAg’s shock is quite different under the four regimes. When a positive shock is given to VAg under the “NG-HR” regime, the current response of GDPg is positive, while a negative response appears from the second period. Such a negative response decreases gradually but lasts for a long time. Nevertheless, under the “HG-LR” regime, the GDPg demonstrated a relatively large positive response in the current period and then declined. In the fourth period, it showed the largest negative response and then decreased gradually until the response ended. The response path of the “MG-LR” regime is similar to that of the “HG-LR” regime with much smaller intensity. Under the “MG-HR” regime, GDPg had the largest positive response in the current period and then decreased to zero gradually. According to the results of the impulse response of GDPg under the four regimes, we can see that under major event crises such as epidemics, an increase in the number of tourists will inhibit the development of the economy. One possible explanation for this is that rising numbers of tourists are likely to increase the risk and severity of the epidemic crisis, which in turn causes more economic damage and leads to higher economic costs to recover. In the high growth period, the increase in VAg plays a relatively significant role in promoting short-term economic growth, while it will have a weak negative impact on economic growth in the future for a longer period. Furthermore, the response of GDPg remains positive during the period of economic crises, and the increase in VAg will have a positive effect on economic growth over a relatively long period.

It’s worth noting that the impulse responses of VAg and GDPg under the “NG-HR” regime are extremely high in specific periods. For example, the response of VAg is as high as 30 in the first period and the response of GDPg is negative 2 in the third period. The result regarding VAg is mainly due to the restrictions on people’s freedom of movement at the stage of the “major event crises” and the severe suppression of tourism demand. Once the epidemic is under control and the economy recovers, the tourism demand will be released, which will result in a significant increase in tourist numbers. The travel plan that was stalled by the outbreak has been restored. Whereas, the rising number of visitor arrivals under the “NG-HR” regime is likely to increase the risk and severity of the epidemic crisis, which causes more economic damage and inhibits economic growth. This gives an explanation to the negative large response of GDPg to VAg in the third period under this regime.

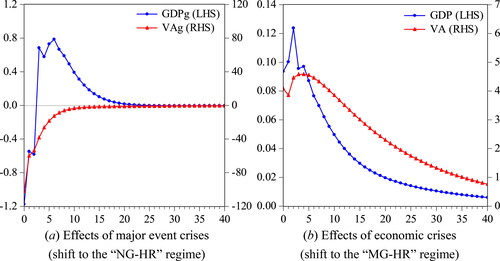

In addition, we compared the impacts of two different types of crises on Hong Kong’s economy and tourism. The results are shown in . After the occurrence of a major event crisis, the economy of Hong Kong exhibited a largely negative response in the current period first and decreased gradually. From the third period, it begins to be positive, and the response decreases gradually after reaching the maximum value in the sixth period. It reduces to zero after around 20 periods, indicating the end of the impulse response. The results of impulse response analysis show that when a major event crisis occurs, the economy of Hong Kong will suffer negative influence significantly in the short run, reflected in short-term negative growth. However, this impact lasts for only a short time and will turn into a positive response after three quarters. The economy of Hong Kong then enters the recovery phase. This result is in line with the transition probability and the average duration of the “NG-HR” regime described in . The “NG-HR” regime lasts for an average of three quarters, and the probability of this turning into the “HG-LR” or “MG-LR” regimes is high. When such a crisis occurs, the number of tourists in Hong Kong will be affected negatively, but this impact lasts for a relatively short time. The spread of the epidemic has the effect of restricting the movement of people, so it has a relatively negative shock on the tourism industry in the short run. Once the epidemic is over, the demand from tourists will increase greatly and the tourism industry will recover quickly.

Figure 5. The economic effects of two kinds of crises. (a) Effects of major event crises (shift to the “NG-HR” regime). (b) Effects of economic crises (shift to the “MG-HR” regime).

It is noteworthy that these analysis results of the impact of economic crisis on the economy and tourism growth in Hong Kong are different from those of other studies. Our research shows that an economic crisis will have a persistently positive impact on Hong Kong’s economy and tourism development, although this positive impact will be relatively small. Therefore, we believe that Hong Kong’s economy has strong sustainability. Though major crises will have a quite negative impact on Hong Kong in the short term, its economy possesses a strong capacity to recover rapidly from the recession period and return rapidly to normality.

Conclusions

This study explored the changing relationships between economic growth and tourism growth in Hong Kong both during and in the absence of crises, and it answered the question of whether crises affect the sustainability of the economic effects of tourism. We used the quarterly growth rate of Hong Kong’s real GDP and VA from 1973Q1 to 2020Q4 as proxies for economic growth and tourism, respectively. It provided empirical evidence that was analyzed in demonstrating the impact of crises on the sustainability of the economic effects of tourism. Specifically, this was achieved by capturing the regime-switching characteristics of the variables through the application of the MSVAR model. The results indicate a relatively clear synchronization between Hong Kong’s economic growth and the development of tourism, with both series being divided into four regimes, namely “NG-HR,” “HG-LR,” “MG-LR,” and “MG-HR.” The “NG-HR” regime corresponds to major event crises, while the “MG-HR” regime corresponds to economic crises.

The results also reveal the high stability and sustainability of Hong Kong’s economy and tourism development. The sustainability of tourism’s economic effects means that tourism can maintain its positive effect on the economy, which will not be interrupted by external factors easily and can recover quickly even if the tourism sector is negatively affected. The sustainability of Hong Kong’s tourism development is well reflected in the empirical results. The huge impact of major event crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, appears to last for a relatively short time, which indicates that Hong Kong has the capacity to recover from such crises quickly, and those periods of crisis are likely to be followed by further rounds of rapid growth. While under the conditions of economic crises, Hong Kong’s economy still manages to maintain moderate growth rates. Furthermore, according to the results of the impulse response analysis, the economic effects of tourism are quite different under the four kinds of regimes investigated. During major event crises such as epidemics, there are significant negative economic effects, and this means that increases in the number of visitors will have the effect of inhibiting economic development. During high growth periods, increases in tourist numbers play a relatively significant role in promoting short-term economic growth, but this will also exercise a weak negative impact on economic growth in the long run. During economic crises, finally, the economic effects remain positive and endure for a relatively long period. The changing economic effects of tourism under the conditions of different regimes demonstrate how the occurrence of crises affects the sustainability of the economic effects of tourism and how these effects vary according to the characteristics of different kinds of crises.

The changing relationships between tourism and economic growth give support to the hypothesis that a bidirectional relationship exists between the two variables. Furthermore, the findings of this study have some useful policy implications. Given that the increase in the number of tourists will have a negative impact on the economy, in the context of an epidemic or pandemic, the government should tighten the restrictions carefully on the movement of people. While in an economic crisis, the role of tourism in promoting economic development has become more significant. The government should therefore exercise preferential tourism policies to stimulate the development of the tourism industry, which will further contribute to the recovery of the economy.

Despite the contributions of our study, some limitations should be noticed. First, as a case study of Hong Kong, this research only focused on one specific region, which may restrict the generalizability of the results. Second, we only used two variables, GDPg and VAg when exploring the relationship between tourism and the economy, while some other variables may also influence their relationship. Given that the MSVAR model can be applied for multivariate analysis, further research can expand to more regions and incorporate more factors in the empirical design. Third, this study used quarterly data with the same frequency, while tourism data have monthly or even higher frequencies. In future studies, the use of mixed-frequency models is encouraged to gain further insights into this important research topic.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from “Natural Science Foundation of China” (Grant nos. 72004077; 71673233), “Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education” (Grant no. 20YJC79007), and “Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant no. JLUXKJC2020312).”

References

- Alexander, D., & Alexander, D. E. (2000). Confronting catastrophe: New perspectives on natural disasters. Oxford University Press.

- Álvarez-Díaz, M., González-Gómez, M., & Otero-Giráldez, M. S. (2019). Estimating the economic impact of a political conflict on tourism: The case of the Catalan separatist challenge. Tourism Economics, 25(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816618790885

- Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

- Anderson, B. A. (2006). Crisis management in the Australian tourism industry: Preparedness, personnel and postscript. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1290–1297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.06.007

- Antonakakis, N., Dragouni, M., & Filis, G. (2015). How strong is the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe? Economic Modelling, 44, 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.10.018

- Arana, J. E., & Leon, C. J. (2008). The impact of terrorism on tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.08.003

- Archer, B. (1973). The impact of domestic tourism. University of Wales Press.

- Avraham, E. (2016). Destination marketing and image repair during tourism crises: The case of Egypt. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 28, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.04.004

- Backer, E., & Ritchie, B. W. (2017). VFR travel: A viable market for tourism crisis and disaster recovery? International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(4), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2102

- Bilen, M., Yilanci, V., & Eryüzlü, H. (2017). Tourism development and economic growth: A panel Granger causality analysis in the frequency domain. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1073231

- Brida, J. G., Matesanz Gómez, D., & Segarra, V. (2020). On the empirical relationship between tourism and economic growth. Tourism Management, 81, 104131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104131

- Brownell, J. (1990). The symbolic/culture approach: Managing transition in the service industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 9(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4319(90)90015-P

- Chatziantoniou, I., Filis, G., Eeckels, B., & Apostolakis, A. (2013). Oil prices, tourism income and economic growth: A structural VAR approach for European Mediterranean countries. Tourism Management, 36, 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.10.012

- Cheung, K. S., & Li, L.-H. (2019). Understanding visitor-resident relations in overtourism: Developing resilience for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(8), 1197–1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1606815

- Choe, Y. J., Choe, S. A., & Cho, S. I. (2017). Importation of travel-related infectious diseases is increasing in South Korea: An analysis of salmonellosis, shigellosis, malaria, and dengue surveillance data. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 19, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.09.003

- Choe, Y., Wang, J., & Song, H. (2021). The impact of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus on inbound tourism in South Korea toward sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 1117–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1797057

- Cole, S., Wardana, A., & Dharmiasih, W. (2021). Making an impact on Bali's water crisis: Research to mobilize NGOs, the tourism industry and policy makers. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103119

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366a), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1979.10482531

- Eugenio-Martin, J. L., & Campos-Soria, J. A. (2014). Economic crisis and tourism expenditure cutback decision. Annals of Tourism Research, 44(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.08.013

- Faisal, A., Albrecht, J. N., & Coetzee, W. J. L. (2020). (Re)Creating spaces for tourism: Spatial effects of the 2010/2011 Christchurch earthquakes. Tourism Management, 80, 104102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104102

- Fu, X., Ridderstaat, J., & Jia, H. (2020). Are all tourism markets equal? Linkages between market-based tourism demand, quality of life, and economic development in Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 77, 104015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104015

- Gao, J., Xu, W., & Zhang, L. (2021). Tourism, economic growth, and tourism-induced EKC hypothesis: Evidence from the Mediterranean region. Empirical Economics, 60(3), 1507–1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01787-1

- Goodrich, J. N. (2002). September 11, 2001 attack on America: A record of the immediate impacts and reactions in the USA travel and tourism industry. Tourism Management, 23(6), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00029-8

- Granger, C. W. (1969). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37(3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912791

- Gunter, U., Ceddia, M. G., & Tröster, B. (2017). International ecotourism and economic development in Central America and the Caribbean. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1173043

- Hanon, W., & Wang, E. (2020). Comparing the impact of political instability and terrorism on inbound tourism demand in Syria before and after the political crisis in 2011. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(6), 651–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1752750

- Haque, T. H., & Haque, M. O. (2018). Evaluating the impacts of the global financial crisis on tourism in Brunei. Tourism Analysis, 23(3), 409–414. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354218X15305418667011

- Henderson, J. C. (2007). Tourism crises: Causes, consequences and management. Routledge.

- Ivanov, S., Gavrilina, M., Webster, C., & Ralko, V. (2017). Impacts of political instability on the tourism industry in Ukraine. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9(1), 100–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1209677

- Kenneally, M., & Jakee, K. (2012). Satellite accounts for the tourism industry: Structure, representation and estimates for Ireland. Tourism Economics, 18(5), 971–997. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2012.0156

- Khalil, S., Kakar, M. K., & Waliullah. (2007). Role of tourism in economic growth: Empirical evidence from Pakistan economy. The Pakistan Development Review, 46(4), 985–994. https://doi.org/10.30541/v46i4IIpp.985-995

- Kim, H. J., Chen, M. H., & Jang, S. (2006). Tourism expansion and economic development: The case of Taiwan. Tourism Management, 27(5), 925–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.05.011

- Klijs, J., Peerlings, J., & Heijman, W. (2015). Usefulness of non-linear input-output models for economic impact analyses in tourism and recreation. Tourism Economics, 21(5), 931–956. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2014.0398

- König, M., & Winkler, A. (2020). COVID-19 and economic growth: Does good government performance pay off? Inter Economics, 55(4), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-020-0906-0

- Krolzig, H.-M. (1997). Markovswitching vector autoregressions: Modelling, statistical inference, and application to business cycle analysis. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-51684-9

- Lei, K., Wen, C., & Wang, X. (2021). Research on the coordinated development of tourism economy based on embedded dynamic data. Microprocessors and Microsystems, 82, 103933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpro.2021.103933

- Li, G., Song, H., Cao, Z., & Wu, D. C. (2013). How competitive is Hong Kong against its competitors? An econometric study. Tourism Management, 36, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.019

- Li, S., Blake, A., & Cooper, C. (2010). China's tourism in a global financial crisis: A computable general equilibrium approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 435–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.491899

- Lim, W. M., & To, W. M. (2021). The economic impact of a global pandemic on the tourism economy: The case of COVID-19 and Macao’s destination- and gambling-dependent economy. Current Issues in Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1910218

- Liu, H., Liu, Y., & Wang, Y. (2020). Exploring the influence of economic policy uncertainty on the relationship between tourism and economic growth with an MF-VAR model. Tourism Economics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620921298

- Liu, H., & Song, H. (2018). New evidence of dynamic links between tourism and economic growth based on mixed-frequency granger causality tests. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517723531

- Mao, C. K., Ding, C. G., & Lee, H. Y. (2010). Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on a catastrophe theory. Tourism Management, 31(6), 855–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.09.003

- Mariolis, T., Rodousakis, N., & Soklis, G. (2020). The COVID-19 multiplier effects of tourism on the Greek economy. Tourism Economics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620946547

- Martins, L. F., Gan, Y., & Ferreira-Lopes, A. (2017). An empirical analysis of the influence of macroeconomic determinants on World tourism demand. Tourism Management, 61, 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.008

- Mayer, M., & Vogt, L. (2016). Economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors: An overview focusing on the spending determinants of visitors. Zeitschrift Für Tourismuswissenschaft, 8(2), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/tw-2016-0017

- McCartney, G., Pinto, J., & Liu, M. (2021). City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities, 112, 103130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103130

- Min, J., Birendra, K. C., Kim, S., & Lee, J. (2020). The impact of disasters on a heritage tourist destination: A case study of Nepal earthquakes. Sustainability, 12(15), 6115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156115

- Narayan, P. K., Narayan, S., Prasad, A., & Prasad, B. C. (2010). Tourism and economic growth: A panel data analysis for Pacific Island countries. Tourism Economics, 16(1), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000010790872006

- Novelli, M., Morgan, N., & Nibigira, C. (2012). Tourism in a post-conflict situation of fragility. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1446–1469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.03.003

- Ntibanyurwa, A. (2010). Tourism multiplier effects: Empirical evidence from Rwanda. International Journal of Ecology and Development, 16(S10), 47–60.

- Oh, C. O. (2005). The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tourism Management, 26(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.014

- Oklevik, O., Gossling, S., Hall, C. M., Jacobsen, J. K. S., Grotte, I. P., & McCabe, S. (2019). Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1804–1824. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1533020

- Okumus, F., Altinay, M., & Arasli, H. (2005). The impact of Turkey's economic crisis of February 2001 on the tourism industry in Northern Cyprus. Tourism Management, 26(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.013

- Okumus, F., & Karamustafa, K. (2005). Impact of an economic crisis evidence from Turkey. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 942–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.04.001

- Ozturk, I., & Acaravci, A. (2009). On the causality between tourism growth and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Turkey. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 5(25), 73–81. https://rtsa.ro/tras/index.php/tras/article/view/193

- Payne, J. E., & Mervar, A. (2010). Research note: The tourism-growth nexus in Croatia. Tourism Economics, 16(4), 1089–1094. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2010.0014

- Perles-Ribes, J. F., Ramón-Rodríguez, A. B., Such-Devesa, M. J., & Moreno-Izquierdo, L. (2019). Effects of political instability in consolidated destinations: The case of Catalonia (Spain). Tourism Management, 70, 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.08.001

- Qiu, R. T. R., Park, J., Li, S. N., & Song, H. Y. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994

- Ridderstaat, J., Croes, R., & Nijkamp, P. (2014). Tourism and long-run economic growth in Aruba. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(5), 472–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1941

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.004

- Rodríguez-Antón, J. M., & Alonso-Almeida, M. M. (2020). COVID-19 impacts and recovery strategies: The case of the hospitality industry in Spain. Sustainability, 12(20), 8599. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208599

- Rontos, K., Syrmali, M. E., Vavouras, I., Karagkouni, E., Saradakou, E., & Salvati, L. (2017). Tourism in time of crisis: Specialization, spatial diversification and potential to growth across European regions. Tourismos, 12(2), 180–206.

- Seetanah, B. (2011). Assessing the dynamic economic impact of tourism for island economies. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.08.009

- Sharma, A., & Nicolau, J. L. (2020). An open market valuation of the effects of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102990

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Sinclair, M. T. (1998). Tourism and economic development: A survey. Journal of Development Studies, 34(5), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389808422535

- Sonmez, S. F. (1998). Tourism, terrorism, and political instability. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2), 416–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00093-5

- Sonmez, S., Apostolopoulos, Y., Lemke, M. K., & Hsieh, Y. C. (2020). Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on the health and safety of immigrant hospitality workers in the United States. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100717

- Steiner, C. (2007). Political instability, transnational tourist companies and destination recovery in the middle east after 9/11. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 4(3), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530701733421

- Su, Y., Cherian, J., Sial, M. S., Badulescu, A., Thu, P. A., Badulescu, D., & Samad, S. (2021). Does tourism affect economic growth of China? A panel granger causality approach. Sustainability, 13(3), 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031349

- Tang, C. H., & Jang, S. (2009). The tourism-economy causality in the United States: A sub-industry level examination. Tourism Management, 30(4), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.09.009

- Tang, C. F., & Tan, E. C. (2015). Does tourism effectively stimulate Malaysia's economic growth? Tourism Management, 46, 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.06.020

- Tohmo, T. (2018). The economic impact of tourism in Central Finland: A regional input–output study. Tourism Review, 73(4), 521–547. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2017-0080

- Tsui, K. W. H. (2017). Does a low-cost carrier lead the domestic tourism demand and growth of New Zealand? Tourism Management, 60, 390–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.013

- UN. (2016). Sustainable development goals. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/economic-growth/

- Wang, Y. S. (2012). Research note: Threshold effects on development of tourism and economic growth. Tourism Economics, 18(5), 1135–1141. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2012.0160

- WTTC. (2019a). Travel & tourism economic impact 2016: World. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

- WTTC. (2019b). Travel & tourism economic impact 2016: Hong Kong. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

- Wu, P.-C., Liu, S.-Y., Hsiao, J.-M., & Huang, T.-Y. (2016). Nonlinear and time-varying growth-tourism causality. Annals of Tourism Research, 59, 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.005

- Yap, G., & Saha, S. (2013). Do political instability, terrorism, and corruption have deterring effects on tourism development even in the presence of unesco heritage? A cross-country panel estimate. Tourism Analysis, 18(5), 587–599. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354213X13782245307911

- Ye, H., & Law, R. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on hospitality and tourism education: A case study of Hong Kong. Journal of Teaching in Travel and Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2021.1875967

- Yu, L., Bai, Y., & Liu, J. (2019). The dynamics of tourism’s carbon footprint in Beijing. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(10), 1553–1571. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1648480

- Zhang, H., Song, H., Wen, L., & Liu, C. (2021). Forecasting tourism recovery amid COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103149

- Zhang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Tourism, economic growth, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in China. Tourism Economics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620918458