Abstract

This article aims to examine how the border closures due to Covid-19 have impacted the well-being of Pacific peoples. Many women, men and children living on islands around the South Pacific live in households that depend on tourism income to provide for the majority of their cash needs, thus the pandemic has delivered a devastating financial blow to them. Nevertheless, an online survey combined with interviews in five Pacific countries shows that many people have drawn on their traditional skills combined with cultural systems, social capital and access to customary land to ensure that their well-being is maintained despite major decreases in household income. Others, however, have been more vulnerable, struggling with reductions in their mental health and increases in household conflict, for example. As well as this, the research data reveals that there needs to be a consideration of the spiritual aspect of well-being as something that is of deep importance for Pacific peoples and can provide them with great comfort and support during times of shocks. We will elucidate what can be learned from this in terms of planning for more just, sustainable tourism.

Introduction

Examples and statistics from around the world have been used to claim that tourism-dependent economies have been 'devastated' (Huang et al., Citation2020; Jones & Comfort, Citation2020; Sheller, Citation2021), 'destroyed' (Ozili & Arun, Citation2020; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020; UNCTAD, Citation2020) or brought to a 'standstill' (Brouder, Citation2020; Khalid et al., Citation2021; UN, Citation2020) by the impacts of Covid-19. In the Pacific, there is heavy dependence on tourism income in several states, making them particularly vulnerable in the face of the pandemic’s associated economic downturn. For example, the five countries that are the focus of this study - Samoa, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Cook Islands and Fiji - rely on tourism for between 12.5 and 87 percent of their GDP (South Pacific Tourism Organisation (SPTO),), Citation2019). The majority of large-scale tourism enterprises in the Pacific are managed by international hotel groups, meaning that many Pacific peoples engage in tourism as employees of an entity without a long-term interest in their country. This, combined with most workers being on casual contracts, in an industry subject to signifcant seasonal shifts in demand, and earning wages that sit at or just above the minimum wage, makes these employees rather vulnerable.

Internationally, industry leaders often assert that the best option in the face of economic challenges associated with the pandemic is to re-open tourism-dependent economies to tourists as soon as possible (Staporncharnchai, Citation2020; Wallin, Citation2020; WTO, Citation2020). However, what these studies do not do, in many cases, is investigate further to see how people have adapted without tourism and what impacts the pandemic border closures have had on people's well-being. This information is essential if we consider how tourism might work better in the future to support sustainable development (Higham & Miller, Citation2018), social justice (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020; Jamal, Citation2019; Rastegar et al., Citation2021), and community well-being goals (Rastegar, Citation2018). In the South Pacific region, comprising those island states in the Pacific Ocean to the South the equator, most governments protected the health of their populations by closing their borders early and leaving them closed to tourists for over a year. They thus remained relatively free of Covid-19 and directly protected the health of their peoples. However, it has not been clear what other impacts these measures have had on multiple well-beings. This is a vital question for tourism scholars and government policy makers around the globe who have been debating what we can learn from this pandemic and how tourism could either recover, or, more significantly, be ‘re-set’ (Prayag, Citation2020), or ‘re-imagined’ (Mackenzie & Goodnow, Citation2021) post-pandemic. The aim of this article is thus to examine ways in which the border closures due to the global pandemic have impacted the well-being of Pacific peoples who are usually dependent on tourism income and to elucidate what can be learned from this in terms of planning for more just, sustainable tourism in future. Essentially, this provides a case study of community well-being during the pandemic in one tourism-reliant region of the world.

The article begins by analysing conceptual ideas on well-being, particularly related to Indigenous people as most people living in the South Pacific can be designated as such, before honing how this concept can apply to Pacific peoples and contexts. The literature on how tourism can contribute to or undermine well-being is then also reviewed. Following this, we explain the ‘remote’ methodology employed in this research, which included both an online survey and working with research associates living in the five different countries. Findings on both increases and decreases in people's reported well-being are then presented and analysed. Overall, we found that despite the financial hardships, many of our respondents experienced improvements to social, mental, spiritual and physical well-being during the pandemic-related border closures. We finish with lessons learned for tourism planners, policy-makers and business owners.

Literature review

Before delving into the primary research conducted in the Pacific, it is essential to situate the study in relation to previous literature on Indigenous well-being, as most South Pacific peoples working in the tourism sector are Indigenous, as well as examining what is already known about Pacific people’s conceptions of well-being. This research asserts that in tourism studies, the well-being of both tourists and those living in tourism destinations needs to be considered thus we will also consider what the literature says about tourism destination communities.

Understanding the well-being of indigenous people

Well-being is a complex concept with no single definition or interpretation (Richardson et al., Citation2019; Shakespeare et al., Citation2020). The OECD and the United Nations highlight the importance of well-being at the individual and the communal level in terms of thinking about people's development (Hatipoglu et al., Citation2020). However, for a long time, well-being was perceived through a Western lens, with ideas of hedonic and eudaemonic well-being dominating (Shakespeare et al., Citation2020). These theories are focused on individual actions to enhance well-being by either gaining pleasure and eluding pain or seeking out meaningful actions in life (Smith & Diekmann, Citation2017). While it is important to recognize that we should not over-generalize about the thousands of unique, Indigenous cultures around the world (Maranga, Citation2013), a common thread running through many of them is use of collective notions of well-being (Durie, Citation1994; Fleming & Manning, Citation2019): these views contrast significantly with individualistic notions of well-being. Indigenous concepts of well-being "do not overlook individuals' health and well-being but position these within a construct of relationality, defining well-being as a state of harmony or balance between physical, mental, spiritual, cultural, community and ecological dimensions, extended through time" (Shakespeare et al., Citation2020, p.9). Indigenous well-being is thus commonly seen as a holistic, multidimensional concept that connects people to their land and each other through their kinship systems (Fleming & Manning, Citation2019; McGurie-Adams, Citation2017; Shakespeare et al., Citation2020; Sones et al., Citation2010; Wilson, Citation2004).

Unfortunately, Indigenous well-being and health have not always been prioritised by governments. Many Indigenous people have to struggle to retain their identity and cultural links, which have been deemed less important than those of settlers. These identities are significant for well-being, especially where Indigenous people have experienced a loss of culture due to various engagements with Western society (Wexler, Citation2009; Wilson, Citation2004). Oppressive systems which breed racism decrease the mental health of Indigenous people; while, accordingly, supportive systems which uplift Indigenous culture aid their resilience and well-being (Cormack et al., Citation2018; National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Leadership in Mental Health, Citation2015; Shakespeare et al., Citation2020; Sones et al., Citation2010; Wexler, Citation2009).

It is problematic if Western notions of health and well-being are the standard that determines all Indigenous health, when, in fact, Indigenous people have different ways of measuring well-being (McGurie-Adams, Citation2017). Durie (Citation1994) asserts that the connection between body and mind is integral to Indigenous health and well-being. He further develops a now widely accepted Māori framework for Indigenous well-being called 'Te Whare Tapa Wha', which has the four walls of a house (whare) being the pillars of well-being: these are, spirituality, thoughts and feelings, physical well-being and family (Durie, Citation1994). For example, Māori women's well-being is seen as being derived from their spiritual ancestors and linked to Papatūānuku (mother earth) as they are "bearers of future generations" (Wilson, Citation2004, p.15). Spiller et al. (Citation2011) extend this to the business sector noting how Indigenous businesses can contribute to the spiritual aspect of well-being. Some businesses have managed to balance traditional customs with contemporary business practices through establishing business models that explicitly recognise and acknowledge the social connectedness and embedding of the enterprise.

However, most research has approached Indigenous well-being "through a deficit lens," which emphasises negative outcomes for Indigenous peoples rather than the ways they are thriving (McGurie-Adams, Citation2017, p.90). In this study, we purposefully ask respondents to consider both negative and positive impacts of tourism-related border closures on their well-being.

Pacific perspectives on well-being

As most people living in the South Pacific island countries are Indigenous, it is not surprising that they align with the Indigenous view of well-being in which "an individual does not exist alone but exists in relationships with other people both living and deceased" (Thomsen et al., Citation2018, p.7). Thus identities, values, beliefs and cultural activities are central to Pacific well-being (Ataera-Minster & Trowland, Citation2018; Thomsen et al., Citation2018). Levels of social and cultural connectedness of Pacific Island peoples are high and are strongly tied to their well-being (Ataera-Minster & Trowland, Citation2018). To sustain well-being, Pacific people need connections to their land and local knowledge (Dacks et al., Citation2019; Richardson et al., Citation2019). This communal and spiritual view of well-being that Pacific people have is at odds with Western ideas of well-being, which are more individualistic and secular (Richardson et al., Citation2019; Thomsen et al., Citation2018).

Pacific peoples have different ways of referring to well-being, from the Kwara’ae (ethnic group in Solomon Islands) ‘good life’ concept of gwaumaurianga (Gegeo, Citation1994), to the Fijian concept of sautu (Richardson et al., Citation2019). The former term embraces “the state of being at the head or pinnacle of life” (Gegeo, Citation1994, p.299). Meanwhile, the latter term can be understood as a term emcompassing the fulfilment of all your needs not so much as individuals, but as families: “It represents the pinnacle and optimal state where the family is operating at its best and have secured a stable, harmonious and mutually sustaining status” (Lealea, Citation2012, p.6).

Due to Pacific people’s different views of well-being from Europeans, alternative well-being frameworks have been developed for them. The Fonofale method is one way of measuring Pacific health, which uses a fale as a representation of the pillars of Pacific well-being, similar to the Te Whare Tapa Wha model (Crawley et al., Citation1995; Durie, Citation1994). These pillars include cultural, spiritual, physical and psychological aspects (Crawley et al., Citation1995). However, as Kupa (Citation2009) notes, this is based on Samoan values. It is essential to recognise that while there are similarities, there are also distinct cultural differences across the Pacific islands (Kupa, Citation2009). Manuela and Sibley (Citation2013) created a Pacific Identity and Wellbeing Scale, based off key values of Pacific identity and well-being in the New Zealand context. They found that familial and social well-being, Pacific connectedness, religion and identity were the five factors that were important for maintaining well-being of Pacific Islanders living in New Zealand. Kupa (Citation2009) found similar results and noted the importance of connection to the environment, such as Tokelauan connections to the weather, stars and the lagoon. This is similar to Indigenous people, who also have a holistic view of well-being that connects people to their land (Crawley et al., Citation1995).

Based on these types of frameworks for Pacific well-being that scholars have created, some countries have put theory into action. In Vanuatu, the government has developed alternative indicators for well-being. They measure citizens' well-being by subjective well-being, satisfaction and stress, which aids the government in finding areas to improve on for the well-being of their people (Tanguay & Haberkorn, Citation2015). Interestingly, many of their measures are based around traditional processes such as a person’s access to customary land on which to grow food, or their trust in their village leaders, as well as their ability to speak their Indigenous language. The survey shows that people are happier when they are more connected to their culture and land, which are essential aspects to their well-being (Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs, Citation2012). Interesting, when international measures of development like the Sustainable Development Goals are applied in the South Pacific, they often miss things that are of central importance to localised perceptions of well-being in the Pacific, such as connections between people and places and their associated Indigenous knowledge (Sterling et al., Citation2020).

The New Zealand government has also created a Living Standards Framework, which measures' four capitals' of well-being for New Zealanders. These are natural, social, human and financial/physical capital. Under this, it includes cultural and community identity to measure well-being (The Treasury of New Zealand, Citation2019). While traditions and customs are listed under social well-being, there is no specific mention of spiritual well-being, despite the New Zealand government considering Pacific perspectives on well-being when creating this framework (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2019; Thomsen et al., Citation2018). A number of scholars have also noted that spiritual well-being is essential to Pacific identity and well-being (Crawley et al., Citation1995; Kupa, Citation2009; Richardson et al., Citation2019).

Tourism and well-being of destination communities

The well-being of Indigenous and Pacific peoples is particularly important when looking at tourism and development. These groups can be quite dependent on tourism income but often have low access to capital, and little influence over tourism policy and practie (Jennings, Citation2017; Tolkach et al., Citation2018). Clearly, tourism can have positive impacts on a community by providing jobs and stimulating the economy; this is clear, for example, when looking at Brunnschweiler's (Citation2010) example of effective ecotourism in the Shark Reef Marine Reserve in Fiji. It is also clear when viewing tourism in the Pacific Island countries most economically dependent on tourism, the Cook Islands. A recent Community Attitudes Survey here found that 89 percent of Maori (that is, Indigenous) respondents felt tourism was good for the Cook Islands, even though only 59 percent of them directly benefited from tourism (New Zealand Tourism Research Institute, Citation2020). However, tourism can also have negative effects on the communities in which tourism operations exist. As Pratt et al. (Citation2016) found in Fiji, when looking at gross national happiness and comparing two villages, the village with less tourism dependence had higher levels of well-being. This is due to the fact that positive economic change through tourism can influence negative social change in the community, particularly in terms of values, family, traditions and organisation of the community.

A range of approaches to tourism have assumed an interest in the well-being of tourism destination peoples. Tourist operators have been more actively trying to promote well-being through their operations, particularly in terms of corporate social responsibility efforts and their support for sustainable tourism (Smith & Diekmann, Citation2017). These ideas can contribute to tourism which is tied to quality of life of local people, although this is often measured by individual satisfaction in different areas (Pratt et al., Citation2016). When looking at the Pacific and considering Indigenous peoples in general, their measures of well-being look more collective ( Richardson et al., Citation2019; Brunnschweiler, Citation2010; Renkert; Citation2020; Chassagne & Everingham, Citation2020). This corroborates research done by Hatipoglu et al. (Citation2020) on small scale sustainable tourism initiatives in Turkey over a five year period. What they found was that in rural areas, the most important factors for societal well-being are strong leadership and societal cohesion. Chassagne and Everingham (Citation2020) apply well-being and tourism to and Indigenous community through the concept of buen vivir. They describe this as: “a holistic vision for social and environmental well-being, which includes alternative economic activities to the neoliberal growth economy” (p1909). With tourism, the authors think that buen vivir can redefine tourism through a lens which prioritises degrowth and moves towards positive interactions between tourists, host communities and the environment (Chassagne & Everingham, Citation2020). Renkert (Citation2020) has similar ideas, using the case study of the Kichwa Anangu community in Ecuador to show how community-led tourism and buen vivir can work in harmony. Here, Indigenous people are able to use cultural and spiritual values to guide their tourism through self-determination, placing well-being at the premise of tourism operations (Renkert, Citation2020).

It is clear that well-being for Pacific and Indigenous people is more collective and thus requires different responses and frameworks than those for Westerners. In the tourism industry, a shift in focus from enhancing individual to communal forms of well-being for local people can help to enhance this. Different ways of thinking inspired by Pacific and Indigenous concepts of well-being, such as buen vivir or sautu can pave the way towards forms of tourism that are more likely to accord with the aspirations of these people.

Methodology

Researcher positionality and ethical issues

The ideas and arguments presented in this article derive from a research project developed in May 2020 by two scholars, the first and second authors of this article, whose work focused on tourism and sustainable development, especially regarding small island states. One is palagi (of European origins) with around 20 years experience in this field, while the other is Fijian, with over 10 years of experience both teaching and researching tourism in the Pacific. They both position themeslves as researchers concerned about social and environmental justice. In this case, they were specifically concerned with how Pacific peoples were coping with a drastic decline in tourism income in the early stages of the global coronavirus pandemic due to border closures. The overarching project focused on how COVID-19 had impacted on people involved in tourism, how these people had responded to those impacts, and how could more sustainable forms of tourism be developed in the future to support well-being of people in the South Pacific region. This work is inspired by Smith’s (Citation1999) decolonised research approach that places Indigenous people at the centre of research. This has encouraged the research term to focus on tourism workers' well-being and that of people residing in destination areas, rather than mainly focusing on travellers or business owners.

In addition to following University's procedures on ethical conduct, which covered fundamental considerations such as informed consent and minimisation of harm, this research is committed to the Pacific research principles as laid out by the Pacific Research and Policy Centre at Massey University (Massey University, Citation2017), namely: respect for relationships; respect for knowledge holders; reciprocity; holism; and, using research to do good. These principles informed the work of the key researchers in a range of ways. Respect for relationships influenced our choice of Research Associates, described below, who were our main interface with research participants in the chosen countries. These people needed to be of, or have a close understanding of, the cultures and language groups they were going to be researching so they could show due respect and follow appropriate protocols. Respect for knowledge holders in terms of upholding the mana (dignity/prestige) of participants was demonstrated by taking a strengths-based approach aligned with appreciative critical inquiry (Ridley-Duff & Duncan, Citation2015). Rather than being positioned as 'victims' of the global pandemic, participants were approached as 'actors' who would have a range of capabilities, knowledges, networks and resources they could draw on in responding to the challenging economic times. The Pacific Research Guidelines state that reciprocity "…can encompass gifts, time and service and extends to accessible dissemination of research findings" (Massey University, Citation2017, p.12). As such, the Research Associates were funded to provide refreshments to research participants, and an initial summary report of findings was provided to the Research Associates to share with their interviewees in a timely fashion (that is, in October 2020, the month after the first phase of data collection ended).

In terms of dissemination of the research, and also the fifth principle of using the research to do good, the key researchers established a website in October 2020 onto which the summary report, short articles, videos and media items relating to the research project are regularly being uploaded: thus the tourism industries and governments of the countries concerned can access the findings quickly, rather than having to wait for journal articles to be published (See https://www.reimaginingsouthpacifictourism.com/). Holism as a principle has also informed the way in which the research has been designed, as the interconnection of physical, social, economic, environmental and spiritual aspects of Pacific communities is intrinsic to the questions that have been asked in the study.

Data collection

Pursuing such research under lockdowns and with significant border restrictions preventing the key researchers from travelling to the chosen countries for fieldwork ultimately required an adaptive approach to data collection. Two main methods were employed in this distance-based research approach. Firstly, we designed an online survey that ran from June to September 2020. The purpose of the online survey was to have a quick means of accessing the views of a variety of people in different Pacific countries who had been impacted by the decline in tourism since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. It asked questions about the economic impacts of the pandemic on individuals, their households and tourism-related businesses, as well as about how it had impacted on people's well-being. We chose to focus on mental, financial, social and physical aspects of well-being because these were common elements in other research on well-being among either Indigenous and/or Pacific people. The survey included some open-ended questions, allowing participants to providing explanatory comments in relation to, for example, their adaptive strategies.

The online survey was distributed using email lists of contacts of the researchers as well as tourism-related social media sites (e.g. Facebook groups) and had 106 responses. 59 percent of respondents were male, 37 percent were female, while 4 percent preferred to self-identify. 60 percent of respondents were between the ages of 20 and 49, while 40 percent were over 50 years of age. 58 percent of those who completed the survey were tourism employees or former employees: over half of employees were involved in large-scale accommodation (hotels/resorts), with groups of others from aviation, ground transportation, smaller accommodation, tour operators, and ‘other’ tourism-related businesses such as taxis. Another 27 percent of respondents owned a tourism or related (e.g. taxi, restaurant) business. The remaining 15 percent of respondents were neither tourism business owners nor employees, but they lived in households or communities impacted by the slowdown in tourism.

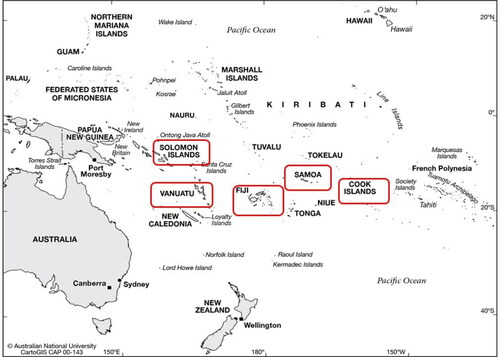

Secondly, five countries were selected for a more in-depth study involving face-to-face interviews: Samoa, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Cook Islands, and Fiji (). Using a multi-country approach was deemed necessary to capture insights into how Pacific islanders in different contexts were coping without tourism and how their well-being had been impacted. These Pacific island states vary considerably in terms of population size, number of visitors annually, and how heavily they rely on tourism for revenue and jobs: this is shown clearly in . However, we chose to gather data for this research from specific communities within these countries that had been, prior to Covid-19, heavily dependent on tourism jobs and revenue. It is this point which enabled us to expose similarities in how the absence of tourism impacted on people’s well-being.

Figure 1. Case study locations.

Source: http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/mapsonline/base-maps/southwest-pacific.

Table 1. Comparison of tourism in five Pacific Island countries, 2019.

In-country research associates (RAs), consisting of five females and one male, were then employed in the five countries. The RAs were approached based on their connections to the tourism sector, prior research experience, and pre-existing links with the specific case study communities. These links provided the necessary access to communities and were a strong platform from which to engage in meaningful conversations with community members. The RAs mostly had prior involvement in tourism either through government or NGO jobs supporting tourism enterprises or involvement with the private sector. They were trained via Zoom about research practice and ethics, with further time to discuss the key researchers' motivations for the study, RA roles and the benefits they would get from taking part in the study.

The RAs were asked to conduct interviews (semi-structured conversations with individuals or pairs) or talanoa in communities impacted by the downturn in tourism. Talanoa refers to more fluid discussions or sharing of ideas and stories between two or more people: they are deemed a more organic and contextually appropriate method than structured interviews (Nabobo-Baba, Citation2008). As alluded to under discussion of Pacific Research Principles above, the RAs were asked to follow appropriate cultural protocols such as organising sevusevu or koha as required and providing refreshments. Engaging in sevusevu or offering koha is important as a transaction which symbolises the beinning of a new relationship and mutual respect between two parties (Brison, Citation2008; Mead, Citation2003). Further Zoom meetings with RAs were scheduled in August and September to discuss progress and problem-solve in terms of any challenges which had arisen. The RA interviews/talanoa with participants centred around the following areas of enquiry:

Please explain the impacts of the slowdown in tourism on your family and community

Please explain ways in which you have coped/adapted to the loss of income and other changes caused by COVID-19

Please explain how the slowdown in tourism and the adaptations you made have influenced well-being in your family and community (both positive and negative impacts on health, economic well-being, cultural and social well-being)

What aspirations do you have for the development of your family and community in the future?

What type of tourism development would you like to see here in the future to meet your aspirations?

The RAs selected participants based on their prior relationships and decided whether individual interviews or group talanoa were most appropriate in each case, given the cultural context. In particular, we asked RAs to specifically seek out the voices of tourism workers, former workers, women, youths, and elders in the communities. provides a summary of those who took part in the the interviews and talanoas. In total, 82 participants across the five countries engaged in either talanoa or interviews. The RAs provided written summary notes and quotes from the interviews to the research team, using pseudonyms to protect participant identities. Where permission was given, some RAs were able to offer the research team audio recordings and photographs in addition to the written report.

Table 2. Interviewees.

Data analysis and limitations

Initial analysis of the data took place during the Zoom meetings with RAs in August and September. Each RA would be asked to reflect on what interviews they had done and if there were any common or prominent ideas being expressed, as well as highlighting if anything had stood out to them as significant or had surprised them. Others in the research team would then reflect on these points, and sometimes another RA would corroborate what an RA from a different location had found or demonstrate a contrary finding, bringing in narratives around how people were coping, adapting, or otherwise reacting to their situation. This was very helpful to the key researchers in terms of identifying key trends.

At the end of the data collection phase, more systematic thematic analysis – an organic, circular process involving coding data, searching for meaning, and interpreting the data (O'Leary, Citation2017) – was undertaken. This involved working with reports from the RAs along with notes taken by the key researchers during meetings with the RAs, transcripts from interviews, and the survey data. Key themes and sub-themes relevant to the study were signalled, and the quotes and statistics were then organised around these themes. Reflexivity was possible because the key researchers were continuously conversing about the data that was coming in, triangulating data from multiple sources and revisiting the data for further clarification (Russell-Mundine, Citation2012). It was during this process that it became clear that we need to add ‘spiritual well-being’ to our themes because it was striking to see how often this was raised by participants, even though questions were not specifically asked about this in the survey or interviews.

Limitations of this study are similar to those faced by many other researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic. We were unable to travel to the field, and had to work remotely, relying on an online survey and RAs situated in the field. The survey was designed with input from social scientists with considerable survey design expertise, yet contains the usual limitations of pre-determined, closed questions (such as the four initial well-being categories, which did not cover the full scope of people’s well-being experiences). However, inclusion of some open-ended questions allowed for considerable elaboration by many of the survey participants, providing great insights into their experiences. A code connecting to the survey was sent out by email, but most respondents completed the survey on their mobile phones, which meant they needed internet access. The high cost of internet access in parts of the Pacific would no doubt have impeded participation in this survey by a number of potential respondents. We would have liked to have had more than 106 responses, but we could not access an established database of contacts across a range of Pacific Island countries to do this.

In terms of the interviews, while on the whole the RAs were invaluable and they collected very rich qualitative data, internet access was sometimes patchy which made communication between the key researchers and RAs difficult at times. In addition, they were not all experienced researchers, and most of them were doing the RA work in addition to fulfilling professional roles. Ideally, we would have worked alongside RAs at field sites which would have provided more opportunities to clarify points with participants, to follow-up on interesting leads, and to gain insights into the context in which people were living. Nevertheless, it should be noted that this research has value as it was the only study to examine views of community members most impacted by the decline in tourism across these countries during the first six months of the pandemic.

Findings

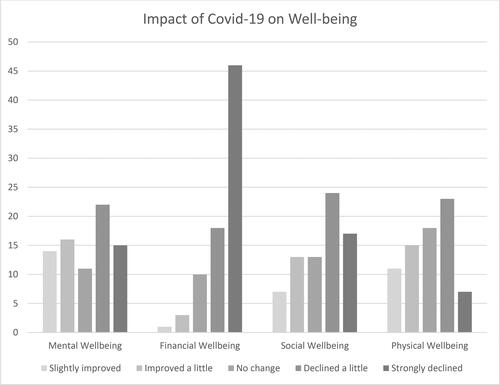

The survey findings on the impacts of COVID-19 on the well-being of respondents are captured in . As noted earlier, four aspects of well-being were studied in the survey: financial, social, mental and physical. In terms of financial well-being, given the impacts on household income noted earlier and the loss of jobs in tourism and shutdowns of many tourism-related businesses, it was not surprising to see a very clear trend where most people's financial well-being had declined, and for many, it had 'strongly declined'. However, for social, mental and physical well-being, the results were more split, with more people showing declines in these aspects of well-being but quite a number showing improvements. This was further revealed by some open-ended questions in the survey (signalled by quotes below denoted as 'Survey respondent') and data from interviews/talanoa (signalled by 'Interview - X country', below).

Figure 2. How COVID-19 has impacted aspects of the well-being of respondents' families, households or communities.

Next, drawing from both the survey and interviews, negative and positive responses to the initial four well-beings will be dicussed in turn, before findings which emerged around the theme of spiritual well-being are elaborated upon.

Financial well-being

As anticipated, many participants indicated the gravity of the financial pressure on their households. While some were able to cope with this in the short term due to savings, this became more difficult the longer the crisis wore on: "Financial struggles have caused us to exhaust all our resources" [Survey respondent]. It was not only owners of tourist businesses, or hotel, restaurant and resort employees who were impacted, but also those operating small village enterprises that were reliant on tourism:

The families and individuals that were relying directly on hotel guests that patronise their small business operations…in so many way as in terms of selling artifacts, operating tours (fishing/diving/horse riding, hiking, visiting waterfalls/hotsprings/schools/caves), to provide them with the needed financial resources weekly, are left high and dry" (Interview – Fiji).

This was corroborated by the owner of a local store, who was concerned not only for her family but for suppliers of handicrafts, with whom she had cultivated strong relationships over time:

Since COVID-19 and the current lockdown of our borders, my business has seen drastic changes. Obviously, reduced sales, therefore income.… We have had long standing partnerships with some of our local handicraft makers, like fans, lavalava, coconut shell bracelets and other jewellery… No one is buying those things as much, so… I know they too are suffering… (Interview – Samoa).

While financial insecurity in terms of one's own family's welfare was a key concern, a number of participants also stressed how important it was to them to meet wider societal commitments: "Our shop is our main source of income…for all our family, church and village obligations" (Interview – Samoa). In some cases, remittances from family overseas had helped them to continue to make these contributions, although often at a lower rate than would have normally occurred, because, as one former tourism employee on reduced hours explained, "…we belong to this community, so despite a tight budget with reduced incomes, we are not letting these obligations slide" (Interview – Samoa).

Also evident in their quotes was a strong link between people's financial, social and mental well-being:

Stress comes with no income, and you only pay but don't receive income – [that] is very difficult, and this promotes arguments and anger towards your immediate social structure [Survey respondent]

The interviews/talanoa also revealed that there were additional pressures on those who had taken out loans in order to start their business. In Fiji, some were struggling to pay back loans on their minibuses, which were now standing idle. Similarly, in Cook Islands, people had mortgages to pay on holiday homes which they had been renting to tourists, and now there was no income to use to meet their obligations to the bank:

It was a worry for me, especially when you have a big loan and you don't know what's going to happen with the job and also what's happening with the economy in general [Interview – Cook Islands]

Despite the financial hardships, some people noted that there were benefits emerging from the loss of income. In the survey, respondents pointed our improvements in household budgeting and financial management skills, and one noted there was "A lot less wastage and more conscious spending". Quotes from 11 interviews/talanoa corroborate these findings, with some in the Cook Islands suggesting that people were "greedy" prior to feeling the effects of the pandemic. Many talked about how returning to or upsclaing use of their customary resources and adopting traditional livelihood practices had saved them a lot of money:

We eat mainly from our plantations, catch our own fish, crab, clams, seaweed and all that's out there that doesn't need cash. We change the brand of toiletries that we've gotten used to, to a cheaper version that does the same thing [Interview – Fiji]

Social well-being

Social well-being refers to people's sense of contentment in their broader social group or environment. For quite a number of research participants, adjusting to significant loss of household income – as indicated in the financial well-being section above - along with restrictions on social gatherings (such as limits on church rituals, community celebrations, and sports practices), has led to adverse implications for their social well-being. In addition, having more family members at home more of the time, with less money to pay the bills, has led to tensions in many households:

It's a constant worry where the money for the next meal for the family, [or] the electricity supply will come from. It's even more worrying if someone gets sick [Survey respondent]

…there is uncertainty of where the next income is coming from and is it coming at all. So the stress levels can shoot high, and you, because of such stress, there's some yelling and arguments with children, or your spouse or even your whole family. I guess that can be an ugly side of it. But its all because of mental stress because you care for your family and you have to worry… [Interview – Samoa]

While the negative social implications of COVID-19 were evident in a number of households, many people were effusive in praising some positive social impacts of the pandemic. In particular, many people spoke of valuing, spending more time with family, especially their children and elderly family members, who often lived together in the same household. This was the case particularly for women who worked in the tourism sector, taking them away from their homes from dawn until dusk when travel and work hours are taken into account. Some noted that there had been more of a return to traditional values such as sharing excess produce with neighbours:

When the fisherman goes out fishing when they cook the fish, they share through the households of Muri [Interview – Cook Islands]

People also appreciated having more time for meeting religious and cultural obligations and to look after others in the community:

At the moment, at [X] village, each Tokatoka [extended family group] does their own rotational visitations to a household each week, mainly on Wednesdays during evening devotion. This helps the villagers a lot with our social, health and cultural well-beings. We have devotions together, catch up over tea or kava afterwards and just socialise & de-stress [Interview – Fiji]

For some, the disruption caused by COVID-19 has led to a re-set of their mind-set, which they have found refreshing:

I have worked in the Tourism Industry for the past 10 years and this is a much welcome break to concentrate and complete certain tasks/projects that were pending at home. This break has given us a "new breath of life". We have since analysed and pondered on what are the most important things in life apart from money. We have strengthened our relationships with friends and family, worked together, laughed and enjoyed each other's company. We have strengthened our spiritual life and have never felt better after moving back to the village [Interview – Fiji]

Mental well-being

Not surprisingly, the financial struggles and uncertainty brought out by the pandemic, as noted above, along with more crowded households due to people being out of work, created issues of anxiety and mental stress for some people. The connections between mental, social and financial well-being are apparent in these quotes:

It has stopped social gatherings which is essential in my community, and as for harmony in my household…. it's driving me crazy being put on lockdown during this pandemic [Survey respondent]

The slowdown has impacted the family psychologically, financially… we don't know what to do. We are unable to meet family, community and church financial commitments [Interview – Fiji]

While the negative impacts on mental well-being are noted and expected, only one interviewee or survey respondent spoke of 'depression'. Meanwhile, many participants showed signs that their resilience, which is linked to their embedded social systems, stood out by deliberately seeking ways to improve their situation. Many of those interviewed were optimistic that they could get through this. Some expressed feeling 'happy', 'contented', 'less stressed', more connected to their families and communities, and felt 'confident' moving forward:

It's changed my life coming home, and I looked around, went to church, and saw people. Went back to the community, you see the people… They are very happy not like before - the stress, the dollar sign. [Interview – Cook Islands]

They presented themselves not as bystanders but as active participants in the change process. Thus the quotes below demonstrate how mental well-being can improve as a result of people's appreciation for the social, spiritual and cultural gains that stem from a return to the land, family and being away from the tourism setting:

We've had so much more time together. It is good to be out in the open and getting dirty. I miss my friends at work and meeting different people every day, but this is nice too; the quiet in the plantation allows us to relax while working. Less stress, and this feels natural. [Interview – Samoa]

Everyone's so connected now, more connected now [Interview – Cook Islands]

Some people talked about enjoying their islands without tourists, as they would see their own people on the beaches, having fun. The slower pace of life without international tourism also meant people finally felt they could 'recharge' their energy and do things that brought them personal satisfaction:

I have to say we've been able to properly rest and recharge focus for a new day. … I have really enjoyed down time with shortened opening hours so have also found time to do other hobbies like learning a new skill like making elei [stencil printing on fabric] or caring for my garden, which has been neglected over the years [Interview – Samoa]

Physical well-being

There were not a lot of negative comments about physical well-being from participants overall. Those who raised concerns mentioned that problems that did occur were associated with increases in alcohol consumption. One woman whose husband had lost his job in tourism noted that she and her husband were not communicating well and that his habit of "drinking Kuaso, the local moonshine…made situations even worse" (Interview - Solomon Islands). Others, especially women who were interviewed, also noted how family arguments and gender-based violence seemed to stem from financial hardship.

…there is uncertainty of where the next income is coming from and is it coming at all. So the stress levels can shoot high and… because of such stress, there's some yelling and arguments with children, or your spouse or even your whole family. I guess that can be an ugly side of it [Interview – Samoa]

Some respondents might have implied physical violence, but it was never stated outright, making this a theme that needs to be explored with sensitivity and more deeply in the next phase of the research.

On the positive side, this study's findings highlight how people perceive an improvement in physical well-being as they move back to the land, engaging in more physical activities related to farming, fishing, and doing work around the house. Respondents and participants alluded to an improvement in physical well-being also because their diets are now healthier, there is more time to prepare meals, and they are not rushed for convenience as was the case when people worked in tourism:

[We] take time to look after our health and well-being - more time for fitness/walking/exercise - better nutrition and spending more time together as a family [Survey respondent].

My kids were sickly when I was working, they were eating junk. Since I'm not working, they're eating more healthy foods-‘kana mai na were' eating from the land–fresh fruits and vegetables [Interview – Fiji].

Interestingly, the health theat of COVID-19 also encouraged some participants to reflect on how they could take responsibility for their own physical health and well-being by the choices they made around diet and exercise:

…we now have to think about doing our own part and looking after our health and eating well. …Our food is our medicine… We've just got to be extra vigilant, extra careful about our health and just do some research [on] how we can sustain good health [Interview – Cook Islands]

Spiritual well-being

When the key researchers designed the initial survey, we did not consider separating spiritual well-being; instead, we saw this as an aspect of social well-being. That is why it does not appear as a category in . However, when analysing the data, it became apparent that many of our respondents were speaking specifically about spiritual well-being, and, importantly, none of them said that this had declined. Rather, their spirituality had helped to uplift them during times of hardship:

The first 2 weeks after losing my job, I was lost! Fortunately, I often spoke to my mother, who was a woman of great faith, and she often told me to ask God for peace. That has been my source of strength and peace [Interview – Fiji]

A number of respondents spoke of experiencing a spiritual revival that had enhanced their sense of well-being since the pandemic struck. They associated this with having time to pray with their families in the evenings and go to church services with the wider community:

I think a lot of people turned spiritual… I mean before this happened…you can have my mates and my cousin sending me, like, church messages. Things like that. I've never seen these people go to church in the past. And now you see them dressed up on Sunday mornings heading down to the church.[Interview – Cook Islands]

We've created more meaningful relations through the strengthening of our daily spiritual family devotions, which has been the cornerstone of our family, especially in our spiritual well-being and helping us navigate through our daily challenges and the occasional triumphs. [Survey respondent].

Some also enacted Christianity through service to others who were struggling due to the pandemic.

Our communities have come together more, I think… We take the time… to make sure neighbours and other extended families are ok, we visit each other more often. I am actually really thankful for that effect of COVID-19. God has his ways, I think it is also a message from God, to look back at our priorities in life and value family and neighbours, to care for each other… [Interview – Samoa].

Another aspect to spiritual well-being was related to the fact that, in order to survive when they lost their tourism sector jobs, many people in the Pacific left towns near to tourist areas in order to return to their villages where they had customary land. This return to ancestral lands is significant because, as well as providing the basis for everyday sustenance through agricultural activities, the land carries deep meaning to Pacific peoples in terms of connecting past, present and future generations. Indigenous terms for ‘land’ (e.g. vanua in Fiji, fonua in Tonga, enua in the Cook Islands) are all-encompassing and include cultural, social and spiritual elements, along with people’s values, beliefs, traditions and history, all interlinked with the natural and supernatural world (Batibasaga et al., Citation1999).

Discussion and implications

This article has provided essential insights into how Indigenous people in the South Pacific have adapted without tourism, extending specific knowledge about how border closures resulting from Covid-19 have impacted destination communities. These findings are important, as they establish that Pacific peoples' well-being should be at the centre of understanding how tourism can be reimagined post-pandemic. More broadly, this article asserts that a multi-dimensional understanding of well-being is essential in tourism research.

The paper has shown that due to the border closures and the virtual collapse of tourism, financial well-being declined, but social, mental and physical well-being improved for quite a number of people. This demonstrates the potential for highly embedded Indigenous social systems to improve well-being (Ataera-Minster & Trowland, Citation2018; Fleming & Manning, Citation2019; McGurie-Adams, Citation2017; Shakespeare et al., Citation2020; Sones et al., Citation2010; Wilson, Citation2004). More importantly, Western approaches to well-being cannot be applied loosely in Pacific tourism research; instead, caution must be exercised because of different contexts and values (Kupa, Citation2009). Certainly, researching well-being must move beyond financial or predetermined measures (Richardson et al., Citation2019).

This paper further affirms that improvements in social and mental well-being are inherently connected (Ataera-Minster & Trowland, Citation2018). This entails appreciating that activities such as relearning traditional knowledge, reconnecting with nature, and engaging in alternative livelihoods activities bring people ‘enjoyment' and cohesively improves their social, physical and mental well-being (McGurie-Adams, Citation2017; Richardson et al., Citation2019). Despite suffering financially, this paper supports the notion that Pacific people are active agents in development. They deliberately seek out ways to improve their situation by turning to their social and ecological systems, utilising traditional ideas and methods as safety nets, coping mechanisms and as a source for improved well-being.

Perhaps this paper’s most notable contribution is to explain the importance of spirituality as a distinct well-being dimension for Pacific peoples. The findings clearly show that increased religious practice, family devotion, church involvement and also, deeper connections to ancestral lands, led to improvements in mental, social, and physical well-being. There can thus be both religious and ancestral components to spirituality as a component of well-being. These components are observed to be holistic and cyclical, including the whole body and mind (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party, Citation1996; Tomyn et al., Citation2013), ‘…in kinship with our planet’ (Spiller, Citation2021, p.176). What was previously thought to be an intangible element nestled under social well-being has emerged from the data as having prominence and power and must be acknowledged as a critical dimension of Pacific peoples' well-being. As our research has shown, spirituality holds immense potential to positively influence social, mental and physical well-being while providing 'comfort' for people enduring financial hardship.

Therefore, we recommend that future research into tourism and well-being that relates at least in part to Indigenous peoples, must consider spiritual well-being as a significant dimension (Ataera-Minster & Trowland, Citation2018; Thomsen et al., Citation2018). The importance of spiritual well-being has been highlighted in the literature around Pacific peoples and Indigenous peoples more generally (Spiller et al., Citation2011), but has yet to be implemented in practice. Spiritual well-being is seldom discussed within the tourism space as it is usually obscured from academic inquiry aims, mostly overlooked due to the dominance of Western frameworks (Pratt et al., Citation2016). Frameworks such as the New Zealand Treasury's Living Standards Framework omit spiritual well-being even though this is intrinsic to the cultures of Pacific peoples, who make up 8.1 percent of the population.

In the pursuit of sustainable tourism, researchers must be sensitive to local beliefs and challenge existing knowledge systems to recommend more equitable and just forms of tourism. This includes re-thinking what we understand as good business practice:

As the world wakes up more and more to our ecological and human crises it is becoming clearer that for too long many people have been promulgating and subscribing to a flawed economic paradigm of short-termism and a singular focus on profit-maximisation which have run roughshod over ancient systems of well-being that value an ecosystemic approach. It’s a return to the true meaning of “welth”, an old English word meaning “to be well” (Spiller, Citation2021: 175).

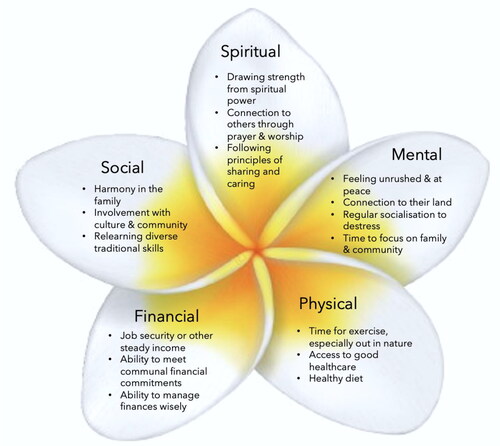

As such, we propose the ‘Frangipani Framework: Pacific Peoples’ Well-Being Through Tourism’ (), which demonstrates aspects of the five critical well-beings discussed in this article. Note that while the give general categories of well-being can be applied across multiple contexts, some of the bullet points within each well-being ‘petal’ might be specific to Pacific experiences. Using the frangipani flower as a metaphor emulating the flourishing dimensions for Indigenous well-being is deemed appropriate for several reasons. Firstly, the frangipani is synonymous with tourist culture, widely used as garlands or ear decorations that one would receive as a token of welcome to countries in the Pacific and tourist destinations worldwide, inducing euphoria when beginning a holiday and, on return home, evoking strong memories of past travel experiences. In tourism, it is often used as a tangible item to improve the tourist experience and enhance various well-beings: for example, it provides a key decorative feature in beauty spas in the Pacific as well as being used in their lotions. Secondly, and more significantly, throughout the world's tropical regions and especially in the Pacific, the frangipani is well-rooted within Indigenous cultures and identities. The frangipani flower is used in wedding ceremonies and for other important occasions in the Pacific, symbolising union and togetherness (Thaman et al., Citation2012). In Hawaiian folklore, the frangipani represents positive ha or life-giving energy. Thirdly, while the frangipani looks delicate, its five petals are quite firm and strong so the flower is naturally tougher and more resilient than many other tropical flowers. This framework aims to encapsulate these values while representing the extension of well-being knowledge, including spirituality, situated in the upward most petal. Furthermore, it supports previous literature that suggests that supportive systems can induce well-being (Shakespeare et al., Citation2020).

The framework reflects Pacific people's mana. Tomlinson and KāWika Tengan (Citation2016) find that mana has no singular definition as it traverses a range of cultures in the Pacific. For the purposes of this article we define it as the spiritual, cultural and ecological strengths embedded within Pacific Islanders’ way of life that are a source of people’s dignity and pride. Mana then becomes an embodiment of the strengths that emanate from the values, practices and the interconnected and reciprocal nature of Pacific cultural systems. That interconnection is represented in by the overlapping of petals, showing that the various dimensions of well-being do not exist alone but are related to one another (Cormack et al., Citation2018; National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Leadership in Mental Health, Citation2015; Sones et al., Citation2010; Wexler, Citation2009). Therefore, the use of the frangipani is appropriate as it depicts the potential for Pacific peoples’ well-being to flourish when in harmony with tourism development.

Tourism and the wanderlust have long been a cure-all for enhanced well-being for people from the West. Tourism’s effectiveness in improving the mental, physical and social well-being of tourists is well documented (Hartwell et al., Citation2018; McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013; Uysal et al., Citation2017). Often, tourists' improved well-being due to their travel experiences has been at the forefront of inquiry. This study has been an attempt to pivot tourism and well-being research towards the aspirations of Indigenous Pacific people in destination communities to seek out pathways for more just, fair and sustainable tourism. By these people, their needs, value systems and traditions at the centre of tourism and well-being research, more equitable outcomes can be harnessed for local communities. Ultimately, global concerns about overtourism prior to the pandemic (Fletcher et al., Citation2019), along with the findings of this research, provide a strong evidence base to assert that in every case where tourism is being planned or developed, well-being of the people that live in the area should be a central concern. Tourism of the future should not focus foremost on tourists' well-being: this will just lead to further environmental damage and greater social and economic inequity in an already divided world (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020; Rastegar et al., Citation2021). Covid-19 has allowed us to reimagine tourism in ways we could not previously. We believe that to build tourism back better, planning and consideration must be done respectfully and be centred around the well-being of destination communities in general, and especially, Indigenous peoples.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 While tourism’s contribution to GDP is a universally used indicator of the value that tourism adds to an economy, it is important to note that there are limitations with this indicator in terms of in inconsistencies in the way in which related data is collected and reported from one context to the next.

References

- Ataera-Minster, J., & Trowland, H. (2018). Te Kaveinga – Mental health and well-being of Pacific peoples. Health Promotion Agency. https://www.leva.co.nz/uploads/files/resources/te-kaveinga-mental-health-and-wellbeing-of-pacific-peoples-june-2018.pdf.

- Batibasaga, K., Overton, J., & Horsley, P. (1999). Vanua: Land people and culture in Fiji. In J. Overton, & R. Scheyvens (Eds.), Strategies for sustainable development: Experiences from the Pacific. Zed Books.

- Brison, K. J. (2008). Defining the community through ceremony. In Our wealth is loving each other: self and society in Fiji (pp. 15–40). Lexington Books.

- Brouder, P. (2020). Re-set redux: possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Brunnschweiler, J. (2010). The Shark Reef Marine Reserve: a marine tourism project in Fiji involving local communities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903071987

- Chassagne, N., & Everingham, P. (2020). Buen Vivir: Degrowing extractivism and growing well-being through tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003017257-10

- Cormack, D., Stanley, J., & Harris, R. (2018). Multiple forms of discrimination and relationships with health and well-being: findings from national cross-sectional surveys in Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0735-y

- Crawley, L., Pulotu-Endemann, F. K., & Stanley-Findlay, R. T. (1995). Strategic directions for the mental health services for Pacific Island people. Ministry of Health. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/2199679

- Dacks, R., Ticktin, T., Mawyer, A., Caillon, S., Claudet, J., Fabre, P., Jupiter, S. D., McCarter, J., Mejia, M., Pascua, P‘a., Sterling, E., & Wongbusarakum, S. (2019). Developing biocultural indicators for resource management. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(6), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.38

- Durie, M. (1994). Tirohanga Maori – Maori health perspectives. In Whaiora – Maori health development (pp.67–81). Oxford University Press.

- Fleming, C., & Manning, M. (2019). Understanding well-being. In Routledge handbook of indigenous well-being (pp. 3–11). Routledge.

- Fletcher, R., Mas, I. M., Blanco-Romero, A., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (2019). Tourism and degrowth: an emerging agenda for research and praxis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1745–1763. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1679822

- Gegeo, D. W. (1994). Kastom and bisnis: Towards integrating cultural knowledge into rural development in the Solomon Islands. PhD Thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Hartwell, H., Fyall, A., Willis, C., Page, S., Ladkin, A., & Hemingway, A. (2018). Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(16), 1830–1892. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1223609

- Hatipoglu, B., Ertuna, B., & Salman, D. (2020). Small-sized tourism projects in rural areas: the compounding effects on societal well-being. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1784909

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after Covid-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Higham, J., & Miller, G. (2018). Transforming societies and transforming tourism: sustainable tourism in times of change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1407519

- Huang, A., Makridis, C., Baker, M., Medeiros, M., & Guo, Z. (2020). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 intervention policies on the hospitality labor market. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102660

- Jamal, T. (2019). Justice and ethics in tourism. Routledge.

- Jennings, H. (2017). Indigenous peoples & tourism. Tourism Concern. Retrieved from http://www.tourismconcern.org.uk/.

- Jones, P., & Comfort, D. (2020). The COVID-19 Crisis, Tourism and Sustainable Development. Athens Journal of Tourism, 7(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajt/v7i2

- Khalid, U., Okafor, L., & Burzynska, K. (2021). Does the size of the tourism sector influence the economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Current Issues in Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1874311

- Kupa, K. (2009). Te Vaka Atafaga: a Tokelau assessment model for supporting holistic mental health practice with Tokelau people in Aotearoa. New Zealand. Pacific Health Dialogue, 15(1), 156–163.

- Lealea, S. (2012). Vuvale Doka Sautu: A cultural framework for addressing violence in Fijian families in New Zealand. Ministry of Social Development. https://library.nzfvc.org.nz/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=3849.

- Mackenzie, S. H., & Goodnow, J. (2021). Adventure in the age of COVID-19: Embracing microadventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leisure Sciences, 43(1-2), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773984

- Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs. (2012). Alternative indicators of well-being for Melanesia: Vanuatu Pilot Study Report. Vanuatu National Statistics Office. http://www.christensenfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Alternative-Indicators-Vanuatu.pdf.

- Manuela, S., & Sibley, C. (2013). The Pacific Identity and Wellbeing Scale (PIWBS): A culturally-appropriate self-report measure for pacific peoples in New Zealand. Social Indicators Research, 112(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0041-9

- Maranga, K. M. (2013). Indigenous people and the roles of culture, law and globalization: Comparing the Americas, Asia-Pacific, and Africa. Universal-Publishers.

- Massey University. (2017). Doing research in the Pacific. Massey University. https://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/learning/departments/centres-research/pacific-research-policy/doing-research.cfm.

- McCabe, S., & Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.001

- McGurie-Adams, T. (2017). Anishinaabeg women's stories of well-being: Physical activity, restoring well-being, and dismantling the settler colonial deficit analysis. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing, 2(3), 90–104.

- Mead, S. M. (2003). Te Takoha: Gift giving. In Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values (pp. 181–192). Huia Publishers.

- Nabobo-Baba, U. (2008). Decolonising Framings in Pacific Research: Indigenous Fijian Vanua Research Framework as an Organic Response. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 4(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718010800400210

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership in Mental Health. (2015). Gayaa Dhuwi (Proud Spirit) Declaration (pp. 1–6). Australian Government Department of Health. https://natsilmh.org.au/sites/default/files/gayaa_dhuwi_declaration_A4.pdf.

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party. (1996). A national aboriginal health strategy. Dept. of Aboriginal Affairs: Australian Government. https://apo.org.au/node/306265.

- New Zealand Tourism Research Institute. (2020). Cook Islands – Community attitudes survey, 2020. Auckland University of Technology. https://www.nztri.org.nz/cook-islands-resources

- O'Leary, Z. (2017). The essential guide to doing your research project (3rd ed). Sage.

- Ozili, P., & Arun, T. (2020). Spillover of COVID-19: Impact on the global economy. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3562570

- Pratt, S., Mccabe, S., & Movono, A. (2016). Gross happiness of a "tourism' village in Fiji. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.001

- Prayag, G. (2020). Time for reset? Covid-19 and tourism resilience. Tourism Review International, 24(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427220X15926147793595

- Rastegar, R. (2018). Tourism development and local community wellbeing: understanding the needs. Tourism Innovations, 8(2), 66–70.

- Rastegar, R., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Ruhanen, L. (2021). COVID-19 and a justice framework to guide tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103161.

- Renkert, S. R. (2020). Community-owned tourism and degrowth: a case study in the Kichwa Anangu Community. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003017257-9

- Richardson, E., Hughes, E., McLennan, S., & Meo-Sewabu, L. (2019). Indigenous well-being and development: Connections to large-scale mining and tourism in the Pacific. The Contemporary Pacific, 31(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2019.0004

- Ridley-Duff, R. J., & Duncan, G. (2015). What is critical appreciation? Insights from studying the critical turn in an appreciative inquiry. Human Relations, 68(10), 1579–1599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714561698

- Rogerson, C., & Rogerson, J. (2020). COVID-19 and tourism spaces of vulnerability in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(4), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-26

- Russell-Mundine, G. (2012). Reflexivity in Indigenous Research: Reframing and Decolonising Research? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 19(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/jht.2012.8

- Shakespeare, M., Fisher, M., Mackean, T., & Wilson, R. (2020). Theories of Indigenous and non-Indigenous well-being in Australian health policies. Health Promotion International. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa097

- Sheller, M. (2021). Reconstructing tourism in the Caribbean: connecting pandemic recovery, climate resilience and sustainable tourism through mobility justice. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(9), 1436–1449. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1791141

- Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (1st ed.). Zed Books.

- Smith, M., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and well-being. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

- Sones, R., Hopkins, C., Manson, S., Watson, R., Durie, M., & Naquin, V. (2010). The Wharerata Declaration — the development of indigenous leaders in mental health. International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 6(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.5042/ijlps.2010.0275

- South Pacific Tourism Organisation (SPTO). (2019). 2018 Annual Visitor Arrivals Report. SPTO: Suva. Retrieved from: https://pic.or.jp/ja/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2018-Annual-Visitor-Arrivals-ReportF.pdf.

- Spiller, C. (2021). Wayfinding odyssey: into the interspace. In J. Ruru & L. W. Nikora (Eds.), Ngā Kete Mātauranga: Māori scholars at the research interface (pp. 173–181). Otago University Press.

- Spiller, C., Erakovic, L., Henare, M., & Pio, E. (2011). Relational well-being and wealth: Māori businesses and an ethic of care. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0540-z

- Staporncharnchai, S. (2020). Thailand to see more visitors, "signal' for reopening - tourism chief. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/thailand-economy-tourism/thailand-to-see-more-visitors-signal-for-reopening-tourism-chief-idUKL4N2ID1G4.

- Statistics New Zealand. (2019). 2018 Census population and dwelling counts: Stats NZ. 2018 Census population and dwelling counts | Stats NZ. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/2018-census-population-and-dwelling-counts.

- Sterling, E. J., Pascua, P., Sigouin, A., Gazit, N., Mandle, L., Betley, E., Aini, J., Albert, S., Caillon, S., Caselle, J. E., Cheng, S. H., Claudet, J., Dacks, R., Darling, E. S., Filardi, C., Jupiter, S. D., Mawyer, A., Mejia, M., Morishige, K., … McCarter, J. (2020). Creating a space for place and multidimensional well-being: lessons learned from localizing the SDGs. Sustainability Science, 15(4), 1129–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00822-w

- Tanguay, J., & Haberkorn, G. (2015). Vanuatu survey: Happiness fact sheet. Secretariat of the Pacific Community & Vanuatu National Statistics Office. http://www.spc.int/DigitalLibrary/Doc/SDD/Fact_Sheet/FS_Vanuatu_happiness_12.pdf.

- Thaman, R. R., Gregory, M. P., & Takeda, S. (2012). Trees of life: a guide to trees and shrubs of the University of the South Pacific. The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji.

- The Treasury New Zealand. (2019). Our living standards framework. The Treasury New Zealand. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/our-living-standards-framework.

- Thomsen, S., Tavita, J., & Levi-Teu, Z. (2018). A Pacific perspective on the Living Standards Framework and well-being (Ser. New Zealand Treasury Discussion Paper). The Treasury. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/dp/dp-18-09.

- Tolkach, D., Cheer, J., & Pratt, S. (2018). Tourism and development in the Pacific: possible or improbable? Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. https://devpolicy.org/tourism-development-in-pacific-possible-or-improbable-20180917/.

- Tomlinson, M., & KāWika Tengan, T. (2016). New mana: transformations of a classic concept in Pacific languages and cultures. ANU Press.

- Tomyn, A. J., Norrish, J. M., & Cummins, R. A. (2013). The subjective well-being of indigenous australian adolescents: Validating the personal wellbeing index-school children. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 1013–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9970-y

- UN. (2019). Population Division: World population prospects. https://population.un.org/wpp/

- UN. (2020). Policy Brief: COVID-19 and transforming tourism. United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_tourism_august_2020.pdf.

- UNCTAD. (2020). Coronavirus deals severe blow to services sectors. UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/news/coronavirus-deals-severe-blow-services-sectors.

- Uysal, M., Sirgy, M., Woo, E., & Kim, H. (2017). The impact of tourist activities on tourists' subjective wellbeing. In M. K. Smith & P. László (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of health tourism (pp. 65–78). Routledge.

- Wallin, B. (2020). Why some countries are opening back up to tourists during a pandemic. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/2020/11/are-economics-driving-countries-to-reopen-to-tourists-coronavirus/.

- Wexler, L. (2009). The importance of identity, history, and culture in the wellbeing of indigenous youth. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 2(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1353/hcy.0.0055

- Wilson, D. (2004). Ngā kairaranga oranga = The weavers of health and well-being: a grounded theory study: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing at Massey University [thesis]. Retrieved from https://mro.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/992.

- WTO. (2020). Restarting tourism. UNWTO. https://www.unwto.org/restarting-tourism.