Abstract

In January 2020, infections with a novel coronavirus were confirmed in China. Two years into the pandemic, countries continue to struggle with fifth and sixth waves, new virus variants, and varying degrees of success in vaccinating national populations. Travel restrictions continue to persist, and the global tourism industry looks into a third year of uncertainty. There is a consensus that the COVID crisis should be a turning point, to “build back better”, and that a return to pre-pandemic overtourism phenomena is undesirable. Yet, there is very limited evidence that the crisis has changed or will change tourism beyond the micro-scale. In regard to many issues, such as new debt, global tourism has become more vulnerable. Against the background of the climate crisis, the purpose of this paper is to take stock: Which lessons can be learned from the pandemic for global warming? To achieve this, relevant papers are discussed, along with a dissection of the development of the crisis in Germany, as an example of ad hoc crisis management. Findings are interpreted as an analogue to climate change, suggesting that our common interest should be to put every possible effort into mitigation and the avoidance of a > 1.5 °C future.

Introduction: two years of COVID-19

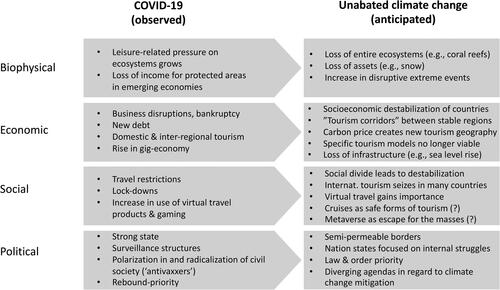

Almost two years after the outbreak of the COVID-19 coronavirus in Wuhan, China, and about 20 months after the spread of the virus to most countries in the world, the availability of vaccines has made the global pandemic more manageable in some countries, but the crisis is far from over (WHO, Citation2021). Struggling with fifth, and sixth waves, new highly infectious virus variants such as Omicron, the unavailability of vaccines in poor economies, and the protests of the “antivaxxers” in significant parts of the population in industrialized countries, COVID-19 continues to affect national economies, businesses, health services and social life. While tourism advocacy organizations (WTTC, Citation2021a) and academics (Deb & Nafi, Citation2020; Dias et al., Citation2021; Dube et al., Citation2021; Gu et al., Citation2021; Mensah & Boakye, Citation2021) have been swift to discuss global recovery pathways, it is currently unclear when to expect a lasting recovery. For the pandemic to become manageable, i.e. for COVID-19 patients to no longer clog emergency beds, it will be necessary for a large share of the population to be vaccinated or to have recovered from an infection. As evident from , the pandemic followed very different trajectories, involving double (India) and multiple (Spain) waves, with observable (United Arab Emirates) and inconclusive vaccination-effects (France, see also for Germany).

Figure 1. Infection trajectories in four different countries.

Source: WHO (Citation2021)

Depending on the situation, national tourism systems have been affected by travel restrictions, lockdowns, quarantines, and mandatory testing, creating volatile and unpredictable business and travel environments. Notable developments included, on the demand side, the turn of business travelers to videoconferencing, as well as the willingness – in an acknowledged absence of alternatives – of significant parts of the population in industrialized countries to embark on domestic holidays (Adinolfi et al., Citation2020; Jacobsen et al., Citation2021). All the while, travel restrictions, test requirements, and quarantines made international travel complicated and demanding. This included both the 2020 and 2021 summer seasons in Europe and North America, for example, with significant implications for shifts in spending, from which export markets profited as money was retained within national economies, while destinations suffered.

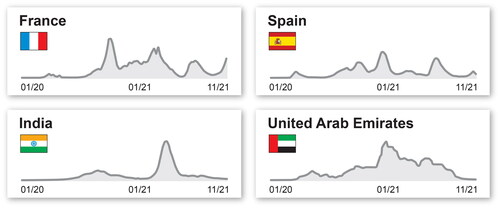

These developments are mirrored in GDP changes, which ranged from −56.3% (Macao SAR, China) to +43.5% (Guyana), and an overall global GDP decline by 3.4% between 2019 and 2020 (World Bank, Citation2021a). Tourism-dependent Small Islands and Developing States (SIDS) are the most affected by the crisis, with nations including the Maldives, Turks and Caicos, St. Lucia, Fiji, Barbados, Dominica, The Bahamas, Antigua & Barbuda, Mauritius, Cabo Verde, Belize, Grenada, St. Kitts & Nevis, or Seychelles all reporting a significant decline in GDP, by 11% (Seychelles) to 32% (Maldives) (World Bank, Citation2021a). illustrates this relationship for the least/most affected nations, showing that, as a general principle, a greater economic reliance on international tourism has resulted in more substantial GDP losses. Tourism-dependent (long-haul) destinations in particular are vulnerable to disruptions in global traveler flows.

Figure 2. Tourism dependence and growth/decline in 2020 GDP.

Source: The World Bank Group, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; WTTC, Citation2021b

On the supply side, impacts on tourism have included bankruptcies and new debt, specifically among airlines and cruise operators (ITF OECD, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2021). ITF OECD (Citation2020) estimated that in October 2020, the maritime shipping industry had already received €8.3 billion in support packages; while loans and guarantees, fiscal transfers, equity and hybrid debt forwarded to the aviation sector amounted to €119.8 billion (March 2020 to March 2021) (OECD, Citation2021). These amounts are notable bearing in mind difficulties to find funding for climate change mitigation. For comparison, the EU LIFE Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation program is endowed with grants amounting to €0.9 billion over the period 2021-2027 (EC, Citation2021a).

Tourism businesses responded to the crisis with product diversification, rebates, workforce reductions, and new marketing strategies (Rogerson, Citation2021; Sharma et al., Citation2021), though it seems clear that the effects of income losses and new debt will be felt for a considerable time. Employment in tourism was also affected by restrictions, closures, and re-openings causing on-off employment situations. Self-victimization prevailed, with for instance airlines repeatedly presenting themselves as victims of the pandemic, omitting that they acted as carriers of the virus (Gössling et al., Citation2021), accelerating the spread of new strains such as Delta or Omicron.

Self-victimization is evident in the sector’s communication. In 2020, the World Tourism Council (2020) suggested that in excess of 100 million jobs in tourism were at risk. In comparison, the Airports Council International saw 46 million aviation and tourism jobs at risk, or 43% of the 87.7 million jobs supported by “aviation and the tourism it facilitates” (ACI, Citation2020: no page). The WTTC (Citation2021c) later concluded that 62 million tourism jobs were lost in 2020. However, not all employment was “lost”. Many countries observed fluctuations in workforce entries and exits (Tourism HR Canada, Citation2021). Significant shares of the tourism and hospitality workforce sought (and found) new employment, with for example one fifth of gastronomy workers in Germany (Grundner, Citation2021) and 15% of those in Austria (ÖGZ, Citation2021) leaving tourism employment. The re-opening tourism economy then presented the sector with problems of finding staff (Zukunftsinstitut, Citation2021).

Beyond this more descriptive discussion of the crisis and its outcomes, there are more profound lessons to be learned. As has been proposed earlier (Gössling et al., Citation2021) and echoed by others (Cole & Dodds, Citation2021; Prideaux et al., Citation2020; Sigala, Citation2020), COVID-19 should be considered an analogue to climate change. There are differences: the pandemic erupted within a few months, while climate change has been acknowledged as an ongoing crisis for decades. The effects of COVID-19 became immediately felt on a global scale, while climate change impacts have mostly had local or regional relevance, for instance in the context of flooding events, storms, wildfires, or heat waves (UNCCS, Citation2019). Yet, there are commonalities. With expectations that climate change will be more economically and socially disruptive than the pandemic, as well as largely irreversible, it is meaningful to study the pandemic with a view to gain insights for the management of climate change.

Method

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, significant numbers of academic papers have been published across all fields. In tourism studies, articles were published within months of the outbreak. Tourism academics have engaged in “response research” before, for instance in the context of terrorism (Krajňák, Citation2020), disruptions such as Airbnb (Guttentag, Citation2019), or overtourism phenomena (e.g. Milano et al., Citation2019). However, the speed of the academic response as measured in paper output is unprecedented, as platforms such as Google Scholar already list thousands of articles on the topic.

To consider the insights that have so far accumulated, the paper sets out with a discussion of the literature on tourism and COVID-2019. Two reviews of the field have already been published, by Yang et al. (Citation2021) and Zopiatis et al. (Citation2021), and this paper does not seek to provide a third systematic or thematic review. Rather, key insights as already presented by Yang et al. (Citation2021) and Zopiatis et al. (Citation2021) are complemented with an integrative review, based on reflexivity, more selective foci, and problematization (Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2020). To achieve this, a sample of papers is considered, including all papers that cite Gössling et al. (Citation2021), as one of the earliest comments on the pandemic. The sample includes papers published between April 2020 and September 2021 (n = 1,953), accessed through Google Scholar’s tracking function that links each citation to a source. This process revealed a large number of references in reports and other non-academic outputs, which are excluded, reducing the number of items published in journals or in book chapters to n = 589. Papers were then assessed on an individual basis to determine their relevance. “Relevant” here refers to either new themes or interpretations of content that add to insights as presented by Yang et al. (Citation2021) and Zopiatis et al. (Citation2021). The process is subjective, and was carried out individually by the two authors to ensure that the discussion would be as inclusive as possible.

As highlighted by Zopiatis et al. (Citation2021) and Yang et al. (Citation2021), many tourism and COVID-19 publications are characterized by poorly conceived methodologies, speculation, “’promotion’ of individual research agendas, personal bias, and ethical and academic integrity issues” (Zopiatis et al., Citation2021, p. 279), as well as a “a lack of theoretical engagement” (Yang et al., Citation2021, p. 14). Their relevance for tourism studies is limited, because many are commentaries, short communications, or using “available” datasets (Yang et al., Citation2021). This calls for a different approach to interpretation. Here, we turn to a critical geography perspective (Bauder & Engel-Di Mauro, Citation2008), complemented with perspectives founded in political science (Marsh & Stoker, Citation1995). Critical geography is explicitly normative and seeks to connect theory and practice, in connection to space, and in discussing bi-directional outcomes of human interaction with Earth systems. This represents a wider perspective on economic-social-environmental systems, here combined with a view on the implications for state and citizenship. Links to tourism are detailed, heeding the call for tourism studies to be critical and transformative (Ateljevic et al., Citation2011), and with the explicit purpose of deconstructing the dynamics of crises that act, and will act, as barriers to considered responses. In deconstructing the general understanding of key tourism institutions (and some academics) that a tourism rebound is desirable – even with the caveat of “building back better” (UNWTO, Citation2021), – a key endeavor is to excavate insights that have relevance for the management of climate change.

Climate change has been described as a “super wicked” problem, because of the limited time left to decarbonize the world economy; the dilemma of those causing the problem also being the ones in charge of defining the solutions; the lack (or weakness) of a central authority to address the problem; and the discounting of the future in policy responses (Levin et al., Citation2012).

Cole and Dodds (Citation2021) propose that these aspects also characterize pandemics, while climate change, biodiversity loss, land-use change, and the emergence of novel infectious diseases also interact in self-reinforcing ways. To link the ongoing crisis to unabated climate change futures is thus meaningful, as this will improve the understanding of the complexity of the challenge humanity needs to prepare for.

The paper probes a national policy response, in Germany, as most insights in regard to crisis management may be derived at this scale of analysis. The country is one of the world’s most important tourism export markets, and its volatile management interventions in the unfolding crisis are well documented in the media. The paper also discusses outcomes for the democratic nation state and its foundation (constitution, fundamental rights, public trust). Throughout, linkages to tourism are considered and highlighted.

Any discussion of a crisis cannot avoid specific viewpoints, and alternative narratives are possible. Even though the authors have sought to balance their perspectives within the normative dimensions of climate change – the global consensus that warming be limited –, views as to how the pandemic is to be evaluated in regard to this phenomenon may vary, and subjectivity in interpretation is acknowledged here.

What we have learned

Two review papers have sought to structure the great number of tourism-related COVID-19 papers that have appeared over the past 18 months. Zopiatis et al. (Citation2021) evaluate n = 362 articles, and identify three distinct themes: impacts of the pandemic on the tourism industry; post-COVID recovery perspectives; tourist perceptions and behaviour. In concluding that the research focus of COVID-19 and tourism research is narrow, the authors outline six research gaps. The first relates to workforce (“human resource management”). Since the review was published, a number of publications have addressed this aspect, for instance in terms of psychological pressure on employees (Chen, Citation2021; Ozdemir, Citation2020; Said et al., Citation2021). Another gap, “finance and economics”, refers to changes in tourist spending, investor confidence, corporate financial tools – including bankruptcy models -, and the impact of government stimulus and aid packages (Zopiatis et al., Citation2021: 279). This gap has significant relevance, as new debt will determine economic vulnerabilities, competitiveness, and price levels – all with great relevance for the future of tourism. State aid in its different forms means that governments, banks and investors are now financially involved in tourism sub-systems, specifically cruises and airlines. To probe these interrelationships has considerable relevance for climate change, as this may mean that transport companies have to show greater commitment on mitigation, or, as governments seek to return to pre-pandemic volume growth models, growing conflicts with decarbonization goals.

Research gaps related to “education and research” comprise “post-pandemic research agendas and paradigm shifts, educational technologies, experiential learning activities, and the expansion of the discipline’s conceptual boundaries via the development of a post-COVID curriculum” (Zopiatis et al., Citation2021, p. 279). “Marketing” covers “expectations, perceptions and attitudes of post-pandemic travelers”, such as those related to travel interest, risk perceptions, or psychological effects on travelers (ibid.: 279). Some of these aspects have been covered in the meantime (Byrd et al., Citation2021; Dedeoğlu & Boğan, Citation2021; Meng et al., Citation2021; Villacé-Molinero et al., Citation2021). In the context of “operations”, digitalization, robot use, health and safety practice, as well as yield and revenue management are listed as gaps, along with more general issues of innovation. Again, some of these topics have received attention, such as health and safety practices (Khatib et al., Citation2020; Rosemberg, Citation2020). Last, “destination” gaps include image restoration, post-pandemic crisis management, as well as “politics and government interventions, sustainability and transformation, and operational strategies for travel service providers (intermediaries)” (Zopiatis et al., Citation2021, p. 279). This is a rather large field. “Sustainability” alone comprises, in the context of this paper, issues as diverse as post-COVID net-zero emission trajectories (Scott & Gössling, Citation2021), the decline in specific travel segments such as business travel, along with emissions (Le et al., Citation2020), and the rise in virtual travel interest (Lu et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2022); growing pressure on ecosystems as a result of changing interest in outdoor activities (Jackson et al., Citation2021; Mutz & Gerke, Citation2021; Schweizer et al., Citation2021), declining pressure on ecosystems as a result of lockdowns (Lele et al., Citation2021), or loss of income for protected areas in emerging economies (Smith et al., Citation2021).

Yang et al. (Citation2021) analyze n = 249 papers on tourism and COVID-19 and identify five major research themes. These include (i) psychological effects and behavior; (ii) responses, strategies and resilience: organization and government; (iii) sustainable futures; (iv) impact monitoring, valuation and forecasting; and (v) technology adoption. Yang et al. (Citation2021) confirm that many of the articles and commentaries are descriptive. They also propose that the field of tourism studies is caught in a binary of “recovery” and “reform”, with contrasting viewpoints that either support a return to the volume-growth tourism model of the past or that advocate for its transformation (ibid.: 11). Yang et al. (Citation2021, pp. 11–12) also bemoan that “few [authors] offer a clear path forward for the industry”, recommending that “scholarship be more reflective of the role of the pandemic in transformative tourism rather than aiming for transformation as an outcome of the pandemic”. This latter suggestion reflects on the importance of distinguishing theoretical vis-à-vis applied research contributions. Against the background of climate change, all the evidence is that tourism needs to transform if it is to remain a viable option for future generations (Scott et al., Citation2019). Indeed, much cited commentaries have echoed this sentiment (Sigala, Citation2020). At the same time, the pandemic has implied changes that are transformative of tourism, as exemplified by the decline in business travel and the widespread adoption of videoconferencing.

Our own integrative analysis suggests that various of the gaps proposed by Zopiatis et al. and Yang et al. (Citation2021) have started to fill. We also find that a large share of papers is concerned with responses (Kreiner & Ram, Citation2021; Pham et al., Citation2021; Sharma et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021) and rebound (Dube et al., Citation2021; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2021; Vu & Hartley, Citation2021), even though many recovery-related findings are premature, in the sense that it is not as yet clear how long the crisis will last, whether behavioral change is permanent, or what the new economic realities of travel and tourism will be. The following section is thus concerned with a meta-perspective that interprets COVID-19 related findings in the wider context of governance in times of crisis. Further findings from the integrative review are introduced here.

What we should have learned

“Crisis management” – or “panic”? A national perspective

Crisis and disaster management is an established field in tourism studies that has focused on the analysis of and responses to events ranging from earlier pandemics, to terrorism, military coups, or environmental disaster (Ritchie, Citation2004). Berbekova et al. (Citation2021) distinguish eight major themes in the crisis literature, including vulnerability & resilience, outcomes, tourist perceptions, models, marketing, communication, media relevance, and dark tourism. Pathogen distribution has been discussed in various contexts, highlighting the role of modern transport systems, specifically aviation, as vectors (Gössling, Citation2002; Hall et al., Citation2020). While several highly problematic incidences of virus distribution have occurred in recent years, COVID-19 proved altogether more difficult to contain because of its characteristics of being highly contagious, yet difficult to detect in early stages; the emergence of new virus strains; and the comparably costly and time-consuming treatment of a share of patients, and relatively high fatality rates. This led to heterogenous responses by national governments. The following analysis discusses developments as these unfolded in Germany.

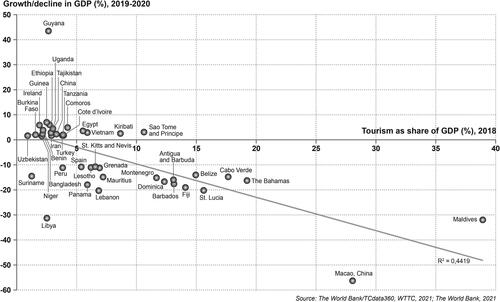

Germany moved through five infection waves over the first 20 months of the pandemic, to which it responded with two lockdowns, business and school closures, and event and activity bans (). Tourism, including incoming, outgoing, and domestic travel, was affected by travel restrictions, quarantines and test mandates. Virtually all measures were implemented on an ad hoc basis, trailing infection rate developments. In March 2020, comparably low infection levels led to a first lockdown, with a palatable nervousness in the population, as evident in clearance sales of toilet paper (Spiegel, Citation2020). This phenomenon was also reported in other countries and repeated itself before the second lockdown in October 2020. It had such significance that it became a topic of research on personality types (Garbe et al., Citation2020), and suggests that the crisis was considered existential by many people.

Figure 3. COVID-19-related restrictions and their impacts on tourism, Germany.

Source: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit 2021, Handelsblatt 2021, Robert Koch Institute 2021

Major tourism-related developments included the repatriation of Germans on holiday in other countries, at a cost of €94 million, in March 2020. A majority of the 240,000 travelers later refused to pay a share of this cost, not considering themselves liable (Euronews, Citation2020). Tourists also endured other inconveniences. Travelers arriving from red list countries or testing positive for COVID-19 were held in “quarantine hotels”, and had to pay accommodation bills (The Guardian, Citation2021a). Travelers trapped onboard cruise ships generated global media headlines (Cruise Law News, Citation2020; Sekizuka et al., Citation2020). Changing restrictions and rules, and the economic losses and cancellations these entailed also caused a flurry in lawsuits, including a supreme court decision on the legality of COVID-19 actions as taken by government (Bundesverfassungsgericht, Citation2021). The supreme court however concluded that lockdowns and other actions by government were backed by the constitution.

In the first year of the pandemic, significant financial support was forwarded to companies and individuals, with a cost of €397.1 billion to Germany’s Economic Stabilization Fund. The total cost of the pandemic, including lost revenue, is estimated at €1.3 trillion (ZDF., Citation2020a), a sum that does not include the cost of hospitalizations and vaccinations, mental health issues, or lost education. The cost of the pandemic can be compared to the German pre-pandemic GDP of €3.473 trillion (in 2019; Destatis, Citation2020), revealing the very significant new debt the crisis has incurred for nations. Notably, while inflation already affects low-income households, the fortunes of the very wealthy grew rapidly during the crisis, both inside and outside Germany (UBS/PWC., Citation2020).

The first German lockdown ended in May 2020 (), when retailers opened again, and schools partially, for older students. During the summer, and up to October 2020, travel was possible within Europe, depending on rules in receiving countries; visits in “at risk” countries implied two-week quarantines. As an effect of these policies, the share of Germans holidaying at home increased considerably, possibly also because of official recommendations to stay in the country (ZDF, Citation2020b). As Germany is one of the largest tourism export markets and a comparably small destination for international tourists, demand exceeded supply during the summer 2020, with positive catch-up effects for tourism businesses. However, continuously changing COVID-19 rules as well as the threat of new travel restrictions represented major planning barriers for both travelers and industry (ZDF, Citation2020b), prompting the national hotel and gastronomy association to “demand an end of the regulation chaos” (DEHOGA, Citation2020, no page).

The winter period 2020/2021 saw a second lockdown, implemented when infection rates started to climb again in October 2020. Retailers, schools, and hotels had to close (in mid-December, affecting the Christmas sales period), and movement in high-incidence areas was restricted, cumulating in a curfew in April 2021. Vaccinations, which began in late December 2020, prioritized the older population, and it was uncertain when and under which conditions tourism would resume. Debates over the EU’s failure to order enough COVID-19 vaccine emerged in January 2021 (The Guardian, Citation2021b). It was only in June 2021 that vaccinations became available to all adults, with the implication that second jabs could only be had four weeks later, in July 2021, making summer holiday planning changes largely impossible. Demand for vaccinations was nevertheless instantaneous, and in particular younger people lined up at vaccination centers to regain travel freedoms. During the summer, travel abroad was characterized by frequently changing rules regarding border crossings, conditions for stays, and returns (negative tests, quarantines). In Germany, hotels and restaurants often required a negative test, a situation that extended over and beyond the second lockdown, with negative repercussions for many businesses. Events were banned completely. As vaccinated older people were free to travel, while families faced travel difficulties also because of specific rules regarding unvaccinated children, COVID-19 justice debates ensued (ZDF, Citation2021). After a relatively quiet summer with low infection rates, these again began to climb in August 2021, reaching a ratio of almost 500 infections per 100,000 citizens and day towards the end of the year. In between an outgoing and an incoming government, a strengthening of rules from “3 G” to “2 G” was the only measure to address infection rate growth at the end of November 2021, i.e. allowing only vaccinated and recovered citizens to enter non-food stores (3 G accepted negative tests; the three German “Gs” refer to “geimpft” (vaccinated), “genesen” (recovered), or “getested” (tested negatively)).

Why is it important to recall these developments? First, it is evident that the German government’s crisis management over close to two years resembled panic behavior, defined here as an ad hoc response to a phenomenon triggered by fear. This perhaps had to be expected, as there was no guideline to rely on. The most recent pre-COVID national pandemic plan (RKI, Citation2017) was modelled on influenza; a document of 72 pages that offers limit insights for a crisis of COVID-19 dimensions. Hence, governmental responses had to be devised on the run, in political processes trailing the actual development of the pandemic, and with no vision as to how to end the crisis. Second, the government apparently felt that it had to justify its actions. Conservative newspaper Die Welt (Citation2021) reports that scientists were pressured to develop a worst-case scenario projecting one million deaths, to stifle an anticipated public outcry in response to restrictions. This justification of the “strong state” also functioned as a mechanism to establish state authority, aided by surveillance technologies such as the Corona-warn-app tracing infection chains (downloaded 37.9 million times as of 6 December 2021, according to the developer). In restaurants and cafés, the “luca” app was used to track patrons. The pandemic consequently saw the establishment of new surveillance structures, justified on the basis of stimulated fears. Third, lockdowns and curfews may also have been considered in terms of their political appeal to the older population, with a view to this large group’s considerable influence on election outcomes. In contrast, very limited attention was given to the potential mental health impacts of lockdowns on children, teenagers, and young adults, who were barred from daycare centers, schools and universities, leisure activities, and even meetings with friends. Negative educational implications are evident (Lütje-Klose et al., Citation2021). Fourth, as governments scrambled to justify restrictions, many countries initially relied on the opinion of individual advisers, the state epidemiologists. Countries with alternative strategies, such as The Netherlands (initially seeking herd immunity) or Sweden (relying on citizens to heed recommendations), were portrayed as irresponsible, a process in which the media played an important role (The Guardian, Citation2020).

As evident from this discussion, limited preparedness to a crisis is likely to have negative outcomes, as ad hoc fear responses (Gray, Citation1987) are necessarily less than perfect. There is a parallel to climate change, where it took several years of hurricanes (Caribbean, USA), wildfires (USA, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Paraguay), or heavy rainfall (Canada, Germany) for populations to begin to understand the implications of global warming. When disaster hit, responses were devised on the run – even though risks are known (e.g. EC, 2021b). This also holds true for tourism. As highlighted by Becken et al. (Citation2020), there are few countries with mitigation or adaptation plans, ignoring the scientific evidence of vulnerabilities (Scott et al., Citation2019). In this context, the German Supreme Court’s ruling gains importance, as it entitles the government to severely restrict citizen rights in the event of an existential crisis (Bundesverfassungsgericht, Citation2021). As climate change represents such a crisis, the ruling should have relevance for mitigation, because it underlines that governments can act, deliberately and anticipatory, if they choose to.

Citizen rights, the strong state, and mental health: an international perspective

The preceding sections suggest that in a crisis, there is a likely reaction of “everyone for himself” at various scales, from governments to political parties to individuals. This highlights another set of interdependent affairs, i.e. the interrelationships of border closures, restrictions of citizen rights, and concomitant outcomes for trust in government. As Cole and Dodds (Citation2021) observe, states reacted individually rather than collectively to the pandemic, weakening international cooperation. National borders quickly became impenetrable, as freedoms of movement were curtailed. An associated risk of xenophobia became evident, as specific traveler nationalities attained pariah status. For example, Swedish tourists were refused entry to other countries, as the country’s media portrayal of succumbing to high infection-rates caused fears. For the same reason, Sweden also saw a massive decline in international tourist arrivals. The class of the wealthy, on the other hand, made headlines when it sought refuge in its private islands, to later on catch up on “lost” holiday time, relying on private air travel (The Washington Post, Citation2021).

Border closures, mobility restrictions, lockdowns, quarantines, curfews, and the closure of educational institutions represent significant infringements on citizen rights and civil liberties that increase economic insecurity and reduce social capital (Fetzer et al., Citation2021). While constitutional, measures could have been considered oppressive by civil society, with potentially negative outcomes for trust in government. For example, the large “antivaxxer” share of the population in Europe was unforeseen. As resistance to vaccinations often took very organized forms, antivaxxer stances may at least partially be explained as a form of rebellion against the state. However, in contrast to these expectations, studies have consistently found that trust in government and democracy increased during the pandemic (Bol et al., Citation2021; Esaiasson et al., Citation2021; Goldfinch et al., Citation2021; Gozgor, Citation2021; Rieger & Wang, Citation2021). Schraff (Citation2021) cautions that this should be interpreted as an outcome of collective angst as a response to the existential threat of growing COVID-19 numbers, and not a support of lockdowns. Yet, studies seem to indicate that in an existential crisis, the state is expected to act, and that such action will increase trust in government. As the Financial Times (Citation2021, no page) commented, the pandemic marks “the close of an era in which power and responsibility migrated from states to markets”.

While measures increased trust in government, lockdowns and the closure of schools also came at a very significant psychological cost. For example, social isolation and the perception of loneliness are associated with suicidal ideation (Calati et al., Citation2019). In the USA, the CDC (Citation2021, 888) reports that suicide attempts of teenagers have increased since May 2020, specifically among girls. While the CDC cautions that linkages to COVID-19 are unclear, it highlights that young people have been affected by concerns as diverse as lack of connectedness, barriers to mental health treatment, increases in substance use, and anxieties in regard to family health and economic problems (CDC, Citation2021, p. 889). The CDC also notes that Emergency Department visits for mental health issues as well as suspected child abuse and neglect increased in 2020. Studies in the USA and UK suggest that child and adolescent eating disorder cases have almost doubled in numbers (Otto et al., Citation2021; Solmi et al., Citation2021). This is echoed in the wider literature, linking COVID-19 with psychiatric disorders, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety and distress, domestic abuse (Casagrande et al., Citation2020; Sher, Citation2020). Quarantines have also been found to affect children and parents, with symptoms including difficulties to concentrate, boredom, irritability, restlessness, nervousness, loneliness, uneasiness and worries (Orgilés et al., Citation2020). A representative study of the impacts of COVID-19 on youth (14-29 years) in Germany confirms negative health effects of the pandemic. It concludes that there is a perceived loss of control in this age group, with expectations that government secure a “livable”, stable economic future (Schnetzer & Hurrelmann, Citation2021). These findings underscore the massive mental health implications of the pandemic, which are overlooked in management responses that handle a crisis on a day-to-day basis. They also emphasize expectations that governments act.

A Note on the future

The preceding discussion suggests that the global response to the pandemic has in many ways been imperfect. Governments will seek short-term system stabilization, making available significant state aid, while working towards a return to the old normal. Critical questions regarding the system’s vulnerabilities are not raised, and the interest to consider the crisis as an opportunity for change is limited, also because of industry’s powerful narratives of employment and revenue loss. Nationally, a tendency to protect “one’s own” is reflected in border closures or new rules of entry for foreign nationals. Longer-term challenges like climate change loose relevance, and the implications of fiscal stabilization policies for future generations remain ignored. Mental health issues are overlooked. Upward distribution in the economy is accepted, as the very wealthy increase their fortunes disproportionally. While there is support of a strong state, there are also signs of polarization and radicalization, as evident in the “antivaxxers”. Science, it appears, can only contribute so much to the understanding of a crisis, underlining the importance of anticipatory planning and management.

These more general insights are reflected in tourism. Here, research indicates significant vulnerabilities, specifically in tourism-dependent economies as well as on the side of airlines and cruises. Accommodation and gastronomy also belong to the vulnerable sub-sectors, as lockdowns and test-requirements affected patron numbers and finances. The most resilient component in the tourism system are the tourists themselves, who have shown great willingness to switch to domestic holidays and to engage in new leisure activities. Virtual travel becomes more attractive, adding to the growth in gaming that was pushed during pandemic lockdowns (King et al., Citation2020). The crisis also caused a rise in the gig-economy, with its short-notice, pay-per-job structures. For instance, food delivery and package delivery services boomed during the pandemic (Gavilan et al., Citation2021). This latter trend suggests growing economic vulnerabilities.

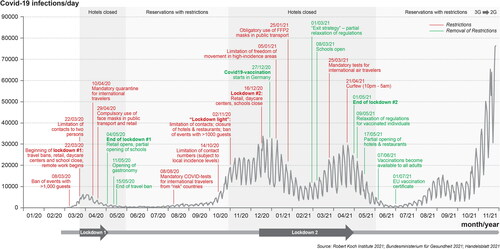

These developments can be compared to anticipated outcomes of unabated climate change. distinguishes biophysical, economic, social and political dimensions, with many linkages to tourism. A shortcoming of this comparison is that there is no specific point in time at which climate change outcomes will become felt at grander scales, as this depends on emission trajectories, adaptation, and so far insufficiently understood system responses. For example, some 14% of the world’s coral reefs have already been lost in the decade 2009–2018 (GCRMN & ICRI, Citation2020), and there is an expectation that even under are more ambitious 1.5 °C maximum warming scenario, 70-90% of all coral reefs will disappear by the end of the century (IPCC, Citation2018). This will affect the livelihoods of millions, with implications for coastal tourism. Compounding this, there is a prospect of infrastructure loss due to sea level rise and extreme events (Scott et al., Citation2012). In Europe, scenarios suggest that snow may vanish entirely below elevations of 1200 m towards the end of the century (Marty et al., Citation2017). These are examples of longer-term, gradual changes that will have significant negative repercussions for tourism. In comparison, disruptive events, including storms, wildfires, heavy rainfall events and flooding, drought and heat waves will be felt more immediately and locally. The prospect is that entire countries will become less desirable as destinations, for interrelated reasons of asset and ecosystem loss, unpredictable weather conditions, or socioeconomic instability (Scott et al., Citation2019).

Should there be more significant threats to socioeconomic stability as economies collapse, it is possible that tourism corridors continue to exist between the stable tourism regions, as observed during the pandemic for “low risk” destinations (e.g. UK Department for Transport, Citation2020). In a dystopian climate change scenario, borders may become semi-permeable, favoring those with economic resources or power. In such unstable worlds, cruises may become more relevant, as ships provide “floating safety” in controlled holiday environments (much in contrast to the current situation with continued outbreaks of the virus onboard cruise ships). Whether such holidays remain economically viable will depend on carbon policies, as cruises require vast amounts of energy and may become too expensive for mass markets. The very wealthy already own super-yachts the size of cruise ships, and there is a new model of shared ships, in which “cabins” of up to 800 m2 are used by a total number of up to 100 guests in ships exceeding the size of cruise ships carrying 2600 passengers (Spiegel, Citation2021). These moving islands may become important destinations of the future, though for a very small share of humanity.

Travel cost, instability and anxieties related to travel may also foster virtual travel, as observed during the pandemic. This suggests a growing interest in the Metaverse and its opportunities for escape. The idea of a parallel, virtual world (the Metaverse) was originally presented in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science fiction novel “Snow Crash”, and has since re-emerged in other novels, such as “Ready Player One” (author: Ernest Cline, 2011). It is imaginable that the virtual world will become an increasingly more desirable place, specifically if the real world is characterized by biophysical and socioeconomic destabilization. This makes it important to understand the Metaverse as an offer of withdrawal to a “stable” world with set rules by corporate authorities. The Metaverse is the antithesis of civil society, and its opportunity and need for engagement. It is introduced at a time when a significant share of young adults no longer plan to have children (Hickman et al., Citation2021), the ultimate expression of distrust in the future. In many ways, the Metaverse is the anticipation, acceptance and acceleration of the real world’s decline in its biophysical, social and political forms.

With growing instability, nations may be increasingly occupied with internal struggles, as currently evident in the USA (McKay, Citation2021). This may lead to diverging agendas in regard to climate change mitigation: countries such as Australia or Saudi Arabia already refuse to support global mitigation efforts. Again, the overall perspective is one of growing vulnerabilities.

Will tourism stakeholders understand the challenge? Zurab Pololikashvili, UNWTO Secretary-General, proposed that:

“The crisis is an opportunity to rethink the tourism sector and its contribution to the people and planet; an opportunity to build back better towards a more sustainable, inclusive and resilient tourism sector that ensue the benefits of tourism are enjoyed widely and fairly” (UNWTO, Citation2021, no page).

But what does this mean in practice, “to rethink tourism”? In all of its public statements, UNWTO supports a pro-growth agenda that pays lip service to net-zero ambitions (Scott & Gössling, Citation2021). As Demiroz and Haase (Citation2019) propose, systems can bounce back to the status quo, or bounce forward to a new equilibrium in response to a disturbance. It may be argued that in tourism, there is a discourse of bouncing forward and a reality of bouncing back. By implication, vulnerabilities will increase. It will take systemic change, not an improvement of existing models, to achieve climate change mitigation and to build more robust tourism systems (Gössling & Higham, Citation2020; Rosenbloom et al., Citation2020). This is the lesson that should have been learned from the pandemic: In a world that engages in serious efforts to mitigate, the global tourism economy will change (Peeters & Landré, Citation2011). It will also be more stable, and benefit a larger number of people. This would seem a price worth paying.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefan Gössling

Stefan Gössling is a professor at Linnaeus-University and Lund University, Sweden. He has worked with different aspects of sustainable tourism and transport since 1995.

Nadja Schweiggart

Nadja Schweiggart (M.Sc.) studied Tourism Management at Hochschule Heilbronn in Germany as well as International Business Economics and Management at KU Leuven, Belgium. She worked in destination marketing at the German National Tourist Board in Brussels as well as a strategy consultant in destination management. She is now a PhD student at the Chair of Marketing and Innovation of the Universität Hamburg, Germany.

References

- ACI. (2020). Up to 46 million jobs at risk due to COVID-19 aviation downturn. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://aci.aero/2020/09/30/up-to-46-million-jobs-at-risk-due-to-covid-19-aviation-downturn/

- Adinolfi, M. C., Harilal, V., & Giddy, J. K. (2020). Travel stokvels, leisure on lay-by, and pay at your pace options: The post COVID-19 domestic tourism landscape in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 10(1), 302–317.

- Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2020). The problematizing review: A counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s argument for integrative reviews. Journal of Management Studies, 57(6), 1290–1304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12582

- Ateljevic, I., Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (Eds.). (2011). The critical turn in tourism studies: Creating an academy of hope. Routledge.

- Bauder, H., & Engel-Di Mauro, S. (2008). Critical geographies: A collection of readings. Praxis e-Press.

- Becken, S., Whittlesea, E., Loehr, J., & Scott, D. (2020). Tourism and climate change: Evaluating the extent of policy integration. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1603–1624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1745217

- Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). A thematic analysis of crisis management in tourism: A theoretical perspective. Tourism Management, 86, 104342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104342

- Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., & Loewen, P. J. (2021). The effect of COVID‐19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? European Journal of Political Research, 60(2), 497–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12401

- Bundesverfassungsgericht. (2021). Verfassungsbeschwerden betreffend Ausgangs- und Kontaktbeschränkungen im Vierten Gesetz zum Schutz der Bevölkerung bei einer epidemischen Lage von nationaler Tragweite („Bundesnotbremse“) erfolglos. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2021/bvg21-101.html

- Byrd, K., Her, E., Fan, A., Almanza, B., Liu, Y., & Leitch, S. (2021). Restaurants and COVID-19: What are consumers’ risk perceptions about restaurant food and its packaging during the pandemic? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102821.

- Calati, R., Ferrari, C., Brittner, M., Oasi, O., Olié, E., Carvalho, A. F., & Courtet, P. (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 653–667.

- Casagrande, M., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R., & Forte, G. (2020). The enemy who sealed the world: Effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Medicine, 75, 12–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011

- CDC. (2021). Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Suicide Attempts Among Persons Aged 12–25 Years Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic – United States, January 2019–May 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7024e1.htm

- Chen, C. C. (2021). Psychological tolls of COVID-19 on industry employees. Annals of Tourism Research, 89, 103080. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103080

- Cole, J., & Dodds, K. (2021). Unhealthy geopolitics: Can the response to COVID-19 reform climate change policy? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(2), 148–154.

- Cruise Law News. (2020). Crew members stranded on cruise ships as cruise lines refuse to agree to pay for repatriation expenses. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.cruiselawnews.com/2020/04/articles/disease/100000-crew-members-stranded-on-cruise-ships-as-cruise-lines-refuse-to-agree-to-pay-for-repatriation-expenses/

- Deb, S. K., & Nafi, S. M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on tourism: Recovery proposal for future tourism. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 33(4 Supplement), 1486–1492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.334spl06-597

- Dedeoğlu, B. B., & Boğan, E. (2021). The motivations of visiting upscale restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of risk perception and trust in government. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102905. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102905

- DEHOGA. (2020). Coronavirus: DEHOGA fordert sofortige Beendigung des Verordnungschaos. Retrieved December 6, 2021 from https://www.dehoga-bundesverband.de/fileadmin/Startseite/06_Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2020/PM_20_07_Coronavirus_DEHOGA_fordert_sofortige_Beendigung_des_Verordnungschaos.pdf

- Demiroz, F., & Haase, T. W. (2019). The concept of resilience: A bibliometric analysis of the emergency and disaster management literature. Local Government Studies, 45(3), 308–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1541796

- Destatis. (2020). Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Wirtschaft/Volkswirtschaftliche-Gesamtrechnungen-Inlandsprodukt/Tabellen/inlandsprodukt-gesamtwirtschaft.html

- Dias, A., Patuleia, M., Silva, R., Estêvão, J., & González-Rodríguez, M. (2021). Post-pandemic recovery strategies: Revitalizing lifestyle entrepreneurship. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–18. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2021.1892124.

- Dube, K., Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and prospects for recovery of the global aviation industry. Journal of Air Transport Management, 92, 102022. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102022

- EC. (2021a). Life Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Retrieved November 29, 2021 from https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/funding-climate-action/life-climate-change-mitigation-and-adaptation_en

- EC. (2021b). Climate change and wildfires. Retrieved January 3, 2022 from https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/09_pesetaiv_wildfires_sc_august2020_en.pdf

- Esaiasson, P., Sohlberg, J., Ghersetti, M., & Johansson, B. (2021). How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: Evidence from ‘the Swedish experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 748–760. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12419

- Euronews. (2020). German passengers sue government over €94m repatriation bill. Retrieved December 2, 2021 from https://www.euronews.com/2020/12/28/german-passengers-sue-government-over-94m-repatriation-bill.

- Fetzer, T., Hensel, L., Hermle, J., & Roth, C. (2021). Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(5), 968–978. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00946

- Financial Times. (2021). How coronavirus is remaking democratic politics. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.ft.com/content/0e83be62-6e98-11ea-89df-41bea055720b.

- Garbe, L., Rau, R., & Toppe, T. (2020). Influence of perceived threat of Covid-19 and HEXACO personality traits on toilet paper stockpiling. Plos One, 15(6), e0234232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234232

- Gavilan, D., Balderas-Cejudo, A., Fernández-Lores, S., & Martinez-Navarro, G. (2021). Innovation in online food delivery: Learnings from COVID-19. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 24, 100330.

- GCRMN & ICRI. (2020). The Sixth Status of Corals of the World: 2020 Report. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://gcrmn.net/2020-report/.

- Goldfinch, S., Taplin, R., & Gauld, R. (2021). Trust in government increased during the Covid-19 pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 80(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12459

- Gössling, S. (2002). Global environmental consequences of tourism. Global Environmental Change, 12(4), 283–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(02)00044-4

- Gössling, S., & Higham, J. (2020). The low-carbon imperative: Destination management under urgent climate change. Journal of Travel Research.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gozgor, G. (2021). Global evidence on the determinants of public trust in governments during the COVID-19. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09902-6

- Gray, J. A. (1987). The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge University Press.

- Grundner, B. (2021). Tourismus in Oberbayern: mehr Gäste und weniger Personal. BR. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://www.br.de/nachrichten/bayern/tourismus-in-oberbayern-mehr-gaeste-und-weniger-personal,Sn9rcSH.

- Gu, Y., Onggo, B. S., Kunc, M. H., & Bayer, S. (2021). Small Island Developing States (SIDS) COVID-19 post-pandemic tourism recovery: A system dynamics approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1924636

- Guttentag, D. (2019). Progress on Airbnb: A literature review. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(4), 814–844. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-08-2018-0075

- Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, E. R., Mayall, E. E., & van Susteren, L. (2021). Young people's voices on climate anxiety, government betrayal and moral injury: A global phenomenon. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3918955

- IPCC. (2018). Summary for Policymakers of IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C approved by governments. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/.

- ITF OECD. (2020). COVID-19 Transport Brief. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/shipping-state-support-covid-19.pdf

- Jackson, S. B., Stevenson, K. T., Larson, L. R., Peterson, M. N., & Seekamp, E. (2021). Outdoor activity participation improves adolescents’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052506

- Jacobsen, J. K. S., Farstad, E., Higham, J., Hopkins, D., & Landa-Mata, I. (2021). Travel discontinuities, enforced holidaying-at-home and alternative leisure travel futures after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1943703

- Khatib, A. N., Carvalho, A. M., Primavesi, R., To, K., & Poirier, V. (2020). Navigating the risks of flying during COVID-19: A review for safe air travel. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(8), taaa212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa212

- King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Billieux, J., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 184–186.

- Krajňák, T. (2020). The effects of terrorism on tourism demand: A systematic review. Tourism Economics, 27(8), 1736–1758.

- Kreiner, N. C., & Ram, Y. (2021). National tourism strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 89, 103076. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103076

- Le Quéré, C., Jackson, R. B., Jones, M. W., Smith, A. J., Abernethy, S., Andrew, R. M., De-Gol, A. J., Willis, D. R., Shan, Y., Canadell, J. G., Friedlingstein, P., Creutzig, F., & Peters, G. P. (2020). Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nature Climate Change, 10(7), 647–653.

- Lele, N., Nigam, R., & Bhattacharya, B. K. (2021). New findings on impact of COVID lockdown over terrestrial ecosystems from LEO-GEO satellites. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 22, 100476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100476

- Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, 45(2), 123–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

- Lu, J., Xiao, X., Xu, Z., Wang, C., Zhang, M., & Zhou, Y. (2021). The potential of virtual tourism in the recovery of tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–17.

- Lütje-Klose, B., Geist, S., & Goldan, J. (2021). Schulschließung während der Covid-19-Pandemie. Perspektiven auf Schüler* innen mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 68(4), 292–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2378/peu2021.art25d

- Marsh, D., & Stoker, G. (Eds.). (1995). Theory and methods in political science. Macmillan.

- Marty, C., Schlögl, S., Bavay, M., & Lehning, M. (2017). How much can we save? Impact of different emission scenarios on future snow cover in the Alps. The Cryosphere, 11(1), 517–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-11-517-2017

- McKay, D. (2021). American politics and society. Wiley.

- Meng, Y., Khan, A., Bibi, S., Wu, H., Lee, Y., & Chen, W. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 risk perception on travel intention: Evidence from Chinese Travelers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655860. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655860

- Mensah, E. A., & Boakye, K. A. (2021). Conceptualizing post-COVID 19 tourism recovery: A three-step framework. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.1945674

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and tourismphobia: A journey through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(4), 353–357.

- Mutz, M., & Gerke, M. (2021). Sport and exercise in times of self-quarantine: How Germans changed their behaviour at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(3), 305–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220934335

- OECD. (2021). State support to the air transport sector: Monitoring developments related to the Covid-19 crisis. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.oecd.org/corporate/State-Support-to-the-Air-Transport-Sector-Monitoring-Developments-Related-to-the-COVID-19-Crisis.pdf.

- ÖGZ. (2021). Warum es im Tourismus an Fachkräften mangelt. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://www.gast.at/gast/warum-es-im-tourismus-fachkraeften-mangelt-206832.

- Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delvecchio, E., Mazzeschi, C., & Espada, J. P. (2020). Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2986. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579038

- Otto, A. K., Jary, J. M., Sturza, J., Miller, C. A., Prohaska, N., Bravender, T., & Van Huysse, J. (2021). Medical admissions among adolescents with eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 148(4), e2021052201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052201

- Ozdemir, M. A. (2020). What are economic, psychological and social consequences of the covid-19 crisis on tourism employees? International Journal of Social, Political and Economic Research, 7(4), 1137–1163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.46291/IJOSPERvol7iss4pp1137-1163

- Peeters, P., & Landré, M. (2011). The emerging global tourism geography – An environmental sustainability perspective. Sustainability, 4(1), 42–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su4010042

- Pham, T. D., Dwyer, L., Su, J.-J., & Ngo, T. (2021). COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on Australian economy. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103179

- Prideaux, B., Thompson, M., & Pabel, A. (2020). Lessons from COVID-19 can prepare global tourism for the economic transformation needed to combat climate change. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 667–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762117

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Rastegar, R., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Destination image during the COVID-19 pandemic and future travel behavior: The moderating role of past experience. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 21, 100620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100620

- Rieger, M. O., & Wang, M. (2021). Trust in government actions during the COVID-19 crisis. Social Indicators Research, 1–23.

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669–683. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.004

- RKI. (2017). Nationaler Pandemieplan Teil I. Strukturen und Maßnahmen. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.gmkonline.de/documents/pandemieplan_teil-i_1510042222_1585228735.pdf.

- Rogerson, J. M. (2021). Tourism business responses to South Africa’s COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency. Geoj. Tour. Geosites, 35, 338–347.

- Rosemberg, M. A. S. (2020). Health and safety considerations for hotel cleaners during Covid-19. Occupational Medicine, 70(5), 382–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqaa053

- Rosenbloom, D., Markard, J., Geels, F. W., & Fuenfschilling, L. (2020). Opinion: Why carbon pricing is not sufficient to mitigate climate change – and how “sustainability transition policy” can help. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(16), 8664–8668. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004093117

- Said, H., Ali, L., Ali, F., & Chen, X. (2021). COVID-19 and unpaid leave: Impacts of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention: Mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour Manag Perspect, 39, 100854. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100854

- Schnetzer, S., & Hurrelmann, K. (2021). Trendstudie: Jugend in Deutschland Winter 21/22. Datajockey Verlag.

- Schraff, D. (2021). Political trust during the Covid-19 pandemic: Rally around the flag or lockdown effects? European Journal of Political Research, 60(4), 1007–1017. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12425

- Schweizer, A. M., Leiderer, A., Mitterwallner, V., Walentowitz, A., Mathes, G. H., & Steinbauer, M. J. (2021). Outdoor cycling activity affected by COVID-19 related epidemic-control-decisions. Plos One, 16(5), e0249268.

- Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2021). Destination net-zero: What does the International Energy Agency roadmap mean for tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1962890

- Scott, D., Hall, C. M., & Gössling, S. (2019). Global tourism vulnerability to climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 49–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.007

- Scott, D., Simpson, M. C., & Sim, R. (2012). The vulnerability of Caribbean coastal tourism to scenarios of climate change related sea level rise. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(6), 883–898. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.699063

- Sekizuka, T., Itokawa, K., Kageyama, T., Saito, S., Takayama, I., Asanuma, H., Nao, N., Tanaka, R., Hashino, M., Takahashi, T., Kamiya, H., Yamagishi, T., Kakimoto, K., Suzuki, M., Hasegawa, H., Wakita, T., & Kuroda, M. (2020). Haplotype networks of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the Diamond Princess cruise ship outbreak. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(33), 20198–20201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006824117

- Sharma, A., Shin, H., Santa-María, M. J., & Nicolau, J. L. (2021). Hotels' COVID-19 innovation and performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103180

- Sher, L. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 113(10), 707–712. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Smith, M. K. S., Smit, I. P., Swemmer, L. K., Mokhatla, M. M., Freitag, S., Roux, D. J., & Dziba, L. (2021). Sustainability of protected areas: Vulnerabilities and opportunities as revealed by COVID-19 in a national park management agency. Biological Conservation, 255, 108985. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108985

- Solmi, F., Downs, J. L., & Nicholls, D. E. (2021). COVID-19 and eating disorders in young people. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 5(5), 316–318.

- Spiegel. (2020). „Das ist pure Jagd, Überlebenskampf.“. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/service/einkaufen-in-corona-zeiten-klopapier-hamsterkaeufe-machen-durchaus-sinn-a-8e014594-6a56-4319-8b69-7d562cdd7be3.

- Spiegel. (2021). Ein Apartment in jedem Hafen. Retrieved January 6, 2022, from https://www.spiegel.de/reise/the-world-somnio-und-njord-der-trend-geht-zum-luxusjacht-apartment-a-8f6b154a-e30f-40d1-a0de-539c4f1824e5.

- The Guardian. (2020). Swedish PM warned over ‘Russian roulette-style’ Covid-19 strategy. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/swedish-pm-warned-russian-roulette-covid-19-strategy-herd-immunity.

- The Guardian. (2021a). 'Treated worse than criminals': Australian arrivals put into quarantine lament conditions. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/treated-worse-than-criminals-australian-arrivals-put-into-quarantine-lament-conditions.

- The Guardian. (2021b). BioNTech criticizes EU failure to order enough Covid vaccine. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/01/france-to-step-up-covid-jabs-after-claims-of-bowing-to-anti-vaxxers.

- The Washington Post. (2021). How the ultra-rich are traveling during covid, according to their travel advisers. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2021/10/08/how-the-rich-travel-covid/

- Tourism HR Canada. (2021). Tourism Employment Tracker. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://tourismhr.ca/labour-market-information/tourism-employment-tracker-insights-into-covid-19s-impact/#Entry-Exit.

- UBS/PWC. (2020). Riding the storm. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.pwc.ch/en/publications/2020/UBS-PwC-Billionaires-Report-2020.

- UK Department for Transport. (2020). Travel corridors. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/travel-corridors.

- UNCCS. (2019). Climate action and support trends. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Climate_Action_Support_Trends_2019.pdf

- UNWTO. (2021). This crisis is an opportunity to rethink the tourism sector. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from, https://www.unwto.org/un-tourism-news-21.

- Villacé-Molinero, T., Fernández-Muñoz, J. J., Orea-Giner, A., & Fuentes-Moraleda, L. (2021). Understanding the new post-COVID-19 risk scenario: Outlooks and challenges for a new era of tourism. Tourism Management, 86, 104324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104324

- Vu, K., & Hartley, K. (2021). Drivers of growth and catch-up in the tourism sector of industrialized economies. Journal of Travel Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211019478

- Welt. (2021). Innenministerium spannte Wissenschaftler für Rechtfertigung von Corona-Maßnahmen ein. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article225864597/Interner-E-Mail-Verkehr-Innenministerium-spannte-Wissenschaftler-ein.html.

- WHO. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://covid19.who.int.

- World Bank Group. (2021a). GDP growth (annual %). Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG.

- World Bank Group. (2021b). TCdata360. Travel and Tourism direct contribution to GDP. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/tot.direct.gdp?country=BRA&indicator=24648&countries=ESP&viz=line_chart&years=1995,2028.

- WTTC. (2021a). Economic Impact Reports. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact.

- WTTC. (2021b). WTTC now estimates over 100 million jobs losses in the Travel & Tourism sector and alerts G20 countries to the scale of the crisis. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://wttc.org/News-Article/WTTC-now-estimates-over-100-million-jobs-losses-in-the-Travel-&-Tourism-sector-and-alerts-G20-countries-to-the-scale-of-the-crisis.

- WTTC. (2021c). A net zero roadmap for travel & tourism. Proposing a new target framework for the travel & tourism sector. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2021/WTTC_Net_Zero_Roadmap.pdf.

- Yang, Y., Zhang, C. X., & Rickly, J. M. (2021). A review of early COVID-19 research in tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research’s Curated Collection on coronavirus and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103313

- ZDF. (2020a). Corona-Kosten: Bis zu 1,3 Billionen Euro. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/corona-novemberhilfen-dezemberhilfen-kosten-bartsch-102.html.

- ZDF. (2020b). Reisebranche in Not. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/wirtschaft/coronavirus-tourismusbranche-urlaub-100.html.

- ZDF. (2021). Entlastungen für Geimpfte. Grundrecht oder Gerechtigkeit. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/corona-lockerungen-geimpfte-100.html.

- Zhang, S. N., Li, Y. Q., Ruan, W. Q., & Liu, C. H. (2022). Would you enjoy virtual travel? The characteristics and causes of virtual tourists’ sentiment under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Management, 88, 104429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104429

- Zhang, H., Song, H., Wen, L., & Liu, C. (2021). Forecasting tourism recovery amid COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103149

- Zopiatis, A., Pericleous, K., & Theofanous, Y. (2021). COVID-19 and hospitality and tourism research: An integrative review. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 48, 275–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.07.002

- Zukunftsinstitut. (2021). Fachkräftesicherung im Tourismus: Resonanz als Erfolgsfaktor. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/artikel/tourismus/resonanz-gegen-fachkraeftemangel-im-tourismus/.