Abstract

Market economies are often characterised by a failure to self-regulate. One of the most enduring of these ‘market failures’ is the ability to maximise the entrepreneurial potential to generate growth. Within this context, gender remains one of, and probably, the most prevalent dimension of this perceived failure to maximise entrepreneurial potential. Feminist political economy provides a starting point for understanding this reproduction of inequalities via policy interventions that have sought to address perceived market failure. This paper analyses how such gendered inequalities are reproduced. Through the critical assessment of Spain’s Emprendetur funding scheme, active from 2012 to 2016, 996 applications were analysed, through a content analysis, applying a gender perspective. The findings, including a decision tree analysis, demonstrate not only that women participate less as applicants in the funding scheme but are also less successful. This can be partly explained because women apply via business typologies that are less successful in relation to the dominance of ICT and technologically informed innovations. However, the barriers extend beyond these typologies; for even when controlling for critical success factors like project size, women are less successful, experiencing a double gender gap, that underlines the need for a gender lens policy approach.

Introduction

Market economies are characterised by a failure to self-regulate their inherent destructive characteristics, leading to various forms of non-market regulation, especially state intervention, to address their limitations (Jessop, Citation2001). There is growing evidence of women entrepreneurs creating and managing successful businesses, with calls for more country/regional-specific policies and initiatives to support women’s entrepreneurship (World Bank, Citation2016). Yet, gender remains one of, and probably the most prevalent dimension, of this perceived failure to maximise entrepreneurial potential (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019), with assumed negative economic and egalitarian consequences.

While many countries possess gender-specific programmes to address such ‘market failure’ (Henry et al., Citation2017; Kimbu et al., Citation2019), most policy interventions have targeted general support for entrepreneurship (Castaño et al., Citation2016), as part of a neo-liberal focus on growth and employment generation (Ahl & Nelson, Citation2015). Such policies inherently fail to address the gendered selectivity of entry to entrepreneurship (Zin & Ibrahim, Citation2020), because support is often determined by masculine and Westernised (mis)conceptions of entrepreneurship that assume women lack the necessary key skills and capital to generate high growth. This condemns women to being, at worst, ‘survivalist entrepreneurs’ and at best ‘constrained gazelles’, with high marginal return to capital but limited growth capacity (Grimm et al., Citation2012), and operating mainly micro, small, and medium sized enterprises (MSMEs) (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). Such policies tend to reproduce the gendered inequalities that they are implicitly intended to target. Gender inequalities here refer to the differences between the essentialist categories of men and women, as influenced by the surrounding economic and social structures, as well as the culture of any particular group (Lorber, Citation2010).

Given the preoccupation with these neo-liberal narratives of growth and market failures, there is still limited understanding of the processes by which gendered inequalities in tourism entrepreneurship tend to be reproduced or, at best, moderated, by entrepreneurship-supporting policies. This is despite the significant growth in the literature that sits at the intersection of gender, tourism, and entrepreneurship (cf. Citationde Jong & Figueroa-Domecq, 2022; Kimbu et al., Citation2021; Kimbu et al., Citation2019; Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Peters & Ateljevic, Citation2009). For a systematic review, see CitationFigueroa-Domecq et al., 2020). This literature, though, has been identified as being dominated by studies underpinned by Global North perspectives that construct women entrepreneurs in essentialist, economically unproductive ways; with only a small segment of the identified studies in tourism and entrepreneurship focusing on the impact of policy-making (CitationFigueroa-Domecq et al., 2020).

This paper contends that inequalities within tourism entrepreneurship stem not only from the gendered nature of society but also in how systematic gendered biases tend to be reproduced in state-backed funding schemes. We adopt a feminist political economy perspective to understand this reproduction of inequalities via policy interventions that target perceived market failure. Particularly important is whether the gendered selectivity in the scale and types (sub-sectors) of business projects women participate in (Coleman & Robb, Citation2009), are carried into the policy arena. It is not only the broad policy goal which matters but also how it is implemented in the face of gendered information asymmetries that persist across public, as well as private funding organisations. These information asymmetries arise because lenders, in response to possessing less information about firms than the lendees, rely on surrogate indicators (Carbo-Valverde et al., Citation2008); a process that has strongly gendered implications.

This article provides insights into these issues by using a mixed methods approach, engaging content analysis, through a gendered lens, to assess a major Spanish funding scheme (Emprendetur) that was designed to promote tourism innovation and entrepreneurship. The bare statistics about this policy initiative, which received almost 1,000 applications during its lifespan (2012–2016) are striking: only 15.3% of applications were made by women, and women’s applications were far less successful than men’s: only 19.6% compared to 32.9%.

Literature review and theoretical framework

Feminist political economy approaches, used here as the theoretical framework, focuses on the complex ways deeply engrained norms and relations are conditioned through political–economic practices/processes that produce unequal outcomes (Porobić Isaković, Citation2018). They examine and deconstruct such social processes (such as entrepreneurial funding schemes) through a gendered lens, providing insights into how normative constructions become embedded within seemingly autonomous economic processes, while granting specific attention to how decisions are made in ways that reproduce inequalities (Porobić Isaković, Citation2018).

A feminist political economy approach argues that economic processes that are not based on equality are harmful for societies and are unsustainable. Consequently, a feminist political economy approach seeks to question the dominant prevailing neoliberal discourse, which contends that all individuals have potential to achieve economic success through entrepreneurship, without considering the relevance of gender or race, for example (Werner et al., Citation2017). By extension, nuanced understandings of social and cultural determinants become airbrushed, ensuring that the failure to become a ‘successful’ entrepreneur is conceived as an individualised issue (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2021). These neoliberal perspectives have been reflected in the policy agendas of both national and international bodies in recent decades, focusing on the ability to generate income and/or employment (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2021): for example, the World Bank’s ‘Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative’ and UNWTO’s ‘Global Report on Women in Tourism’ (de Jong & Figueroa-Domecq, Citation2022).

Participation in funding schemes from a gender perspective

The existing literature on applications for funding, almost without exception, focus on analyses of grant applications to commercial rather than public sector lenders, or on gendered differences in the rates of application for external funding (Cziráky et al., Citation2005). Nevertheless, recent evidence identifies gendered differentials in performance and in accessing external funding. Not only are women less likely to become entrepreneurs but, when they do, they are less likely to apply for external funding and they apply for smaller amounts (Coleman & Robb, Citation2009; Yacus et al., Citation2019); perhaps because they are more likely to have smaller capital needs (Alsos et al., Citation2006; Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). The lower numbers of women applying for, and accessing external funding, are often positioned as either, or both, a reluctance due to pessimistic perceptions of discrimination or disadvantage (cf. Roper & Scott, Citation2009) and a lower propensity to take on debt because they are more risk averse (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2022).

Risk aversion, loss of control, and information opacity may, ergo, likely drive women entrepreneurs to pursue personal and/or family funding and informal microfinance which is presumed to be safer and less stressful than formal external funding and debt. However, this practice may reduce women’s access to business capital and constrain growth (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019).

Another important consideration is that not all women enter entrepreneurship with the purpose of achieving high growth (Hughes et al., Citation2012; Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). Women business owners have a broader range of entrepreneurial intentions or goals than men including, for example, self-realisation, work/life flexibility, innovation, and independence (Carter et al., Citation2003). They are more likely to undertake social and/or environmentally orientated entrepreneurship (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2022; Coleman & Robb, Citation2018) and work part time or casually, often due to the higher, socially constructed obligation of women to take on work/family commitments (Coleman & Robb, Citation2009). All these influence women’s approaches to applying for external funding. We therefore posit that:

H1a. Women apply less in funding schemes.

H1b. Women apply for funds for smaller projects.

Social norms and gender stereotypes are powerful mechanisms influencing people’s perceptions of occupations as being masculine or feminine. Entrepreneurship is gendered and continues to be ‘perceived and portrayed as a stereotypically masculine endeavour’ (Jennings & Brush, Citation2013: 680). Although the gap in the rates of women and men entering entrepreneurship are diminishing, there is still significant gender segregation within entrepreneurship by industry (Micelotta et al., Citation2018), leading those undertaking a more feminised entrepreneurial performance to experience greater challenges (Jennings & Brush, Citation2013; Kimbu et al., Citation2021). However, when a woman business owner is in an industry perceived as feminine, such as a services business, it is recognised that they experience fewer challenges than in more masculine industries because of the feminisation of that industry. In part, this has led women entrepreneurs to gravitate towards industries that are widely recognised as feminine, whilst men entrepreneurs have been found to gravitate towards masculine associated industries (Tellhed et al. Citation2018). Consequently, we propose that:

H1d. Women are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial projects related to consumers services.

Characteristics of successful projects: the impact of gender

Information asymmetries play an important role in lending because lenders have less information about the firms they are considering lending to (Carbo-Valverde et al., Citation2008) than the firms themselves. As a result, lenders tend to focus on ‘visible’ surrogate indicators, and ‘success at obtaining finance resides in the availability of signals of quality that can aid the selection of investment propositions’ (Mina et al., Citation2021: 2). The most potent of these are human capital, collateral, and firm size. Human capital is considered to signal entrepreneurial competence (Florin et al., Citation2003). Collateral is a key form of insurance against default for lenders (Lehmann & Neuberger, Citation2001). Smaller firms are generally considered to be disadvantaged in this respect, not only because they have fewer tangible assets than larger firms but also because their more informal internal procedures mean they have less documentation of ‘signals of quality’ (Canton et al., Citation2013). Additionally, Levenson and Willard (Citation2000) contend that lenders are deterred by the high fixed costs of providing the smaller loans that small companies usually apply for. Lenders also favour firms with physical assets as opposed to intangible ones, leading to the valuing of manufacturing firms over services firms (Silva & Carreira, Citation2010), as well as—in the context of this paper—firms whose innovations have a strong technological focus. All these factors are known to affect and disadvantage women-owned enterprises which tend to be smaller, have limited tangible assets and little to no collateral security compared to men owned enterprises (Morris et al., Citation2006). We, therefore, posit that:

H2a. The size of the project influences success.

H2b. The amount of requested money influences the success of funding applications.

H2c. The type of economic activity impacts on the success rates.

Despite the increasing rate at which women are starting businesses, there remains a marked gap in terms of women operating larger businesses which employ higher numbers of individuals because of the gendered challenges they experience in accessing external funding to grow their enterprises. This enhances the likelihood of men-led enterprises obtaining additional funding later in the entrepreneurial journey. Importantly, however, gender differences tend to disappear for businesses that receive similar amounts of funding in the early stages of business development, highlighting the importance of early funding in reducing gendered inequalities within entrepreneurship (Alsos et al., Citation2006).

Networking and social capital have further been identified as determinants in funding decisions, whereby financial institutions are observed to prefer to deal with companies they have pre-existing established relationships with (Xiong et al., Citation2011). Both women and men entrepreneurs who are highly embedded (i.e., networked, coexisting, and interacting with other actors) can more easily access resources, win legitimacy, and enhance entrepreneurial agency (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Kimbu et al., Citation2019). However, women again are at a disadvantage in this respect, for their connections tend to be less diversified and more likely to exclude contacts with financial institutions (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). At the same time, women’s limited access to executive positions and smaller networks reduces opportunities for the endorsement of their professional aptitudes, again reducing funding success (Brooks et al., Citation2014).

Scholars argue that variances in funding outcomes are the direct result of biased investors, who are disproportionately men, who disproportionately decide to provide capital to other men (Brooks et al., Citation2014). Gendered bias and stereotypical judgments also limit investors engagement with women. For example, investors may unwittingly offer women entrepreneurs fewer opportunities to present themselves and discuss funding. These observations underline the subtle, as opposed to overt, biases that persist (Joshi et al., Citation2015) and contribute to gender disparity in funding outcomes (Kanze et al., Citation2018). Consequently, Orser et al. (Citation2000) note that, some women entrepreneurs, who are likely to be aware of these gender biases, do not even attempt to seek business funding. We therefore posit that:

H3. Women are generally less successful than men when applying for funding from gender-neutral funding scheme.

Methodology

This study analyses, from a gender perspective, the Emprendetur funding scheme which aimed to support enterprises within the Spanish tourism industry through the broad areas or subprogrammes of ‘Research and Development’, ‘Innovative Products’, and ‘Young Entrepreneurs’ from 2012 to 2016. During this period, 996 applications were received, and 313 projects were approved. A mixed method content analysis is used to analyse the call’s description and all the applications.

Content analysis

A content analysis is a systematic search or review, where the researcher attempts to draw inferences from a ‘text’, to identify or understand certain trends or themes, or common characteristics in communication, in this case through a mixed methods methodology (Schram, Citation2014). It allows researchers to establish their own context of inquiry to extend understanding beyond the immediately observable physical vehicles of communication (Krippendorff, Citation1989: 403). The aim of the study defines the need for implementing a gender perspective in the content analysis (Rocheleau, Citation1995). Following Creswell and Plano Clark’s (Citation2017) guidance on conducting mixed method content analysis, the following steps have been followed.

Documentation selection: two types of documents are analysed.

Call description: The Emprendetur funding scheme was divided into three calls: R&D, young entrepreneurs, and internationalisation. The R&D and young entrepreneurs calls were active from 2012 till 2016, while internationalisation was only active in 2016. In total documents from 11 different calls were analysed: the annual calls for R&D and young entrepreneurs over five years (10 documents) and one call for internationalisation (1 document).

Applications: Participants are required to present three types of documents. First, legal documentation, which has been excluded as not being relevant for this study and due to privacy concerns; secondly, a business plan, not included in this exploratory analysis; and finally, a standardised application form, that includes all the relevant characteristics of the project. Only the last document has been analysed.

Codification: A quantitative and qualitative content analysis allowed the codification of themes. Three researchers were involved in the design of the content analysis, to ensure the coherence of the coding process which adopted the following process:

Call description: A combination of inductive and deductive methods provided greater insight in the application of mixed methods. Through a deductive process, especially considering the relevance of a gender perspective in relation to technology, a quantitative content analysis was performed: advance search was applied to identify the relevance of gender in the documents, and the relation between innovation and technology. After that, a qualitative inductive process was applied in order to identify relevant topics from a gender perspective.

Applications: Two researchers were involved in the codification of the 996 applications. After eliminating repeated cases and incomplete applications, a total of 932 applications were analysed. From a deductive perspective, several variables were identified as plausible and homogeneous in the codification process. The key variable, the applicant’s gender, was identified through name disambiguation; this task was unproblematic in most of the applications, but some ambiguous names were searched in Google and disambiguation was ultimately possible in all cases (Pooja et al., Citation2021). presents the quantitative variables under analysis.

Table 1. Variables, content analysis.

Integration or merging of the data, data transformation (Schram, Citation2014), ‘refers to the process of assigning numerical (nominal or ordinal) values to data conceived as not numerical’, also called quantising. In this analysis, inductive and deductive methods were combined (data transformation) to evaluate the calls and applications.

Statistical analysis

As an exploratory analysis, the descriptive statistical analysis is followed by a Decision Tree (DT) Analysis. Using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests, the exploratory analysis identified the main characteristics of a project successfully obtaining funding, the impact of the applicant’s gender (woman or man), as well as the success rate. To weigh the influence of gender in the different characteristics of the projects, as well as in their success, OR (binomial and emphasised logistic regression) was used to complement the Chi-square tests, through Odds Ratio (OR).

The DT systematically analyses data to derive important relationships between the target or dependent variable, and the input or independent variables, and displays these in a tree structure. The tree is composed of nodes, branches, and leaves. The advantages of the DT include not requiring a pre-defined underlying relationship and allowing a number of explanatory variables to be processed, identifying the most relevant variables for explaining the variance in the dependent variable (Rondović et al., Citation2019). Within DT, CHAID was applied. CHAID is a criterion-based approach that allows researchers to understand segments in relation to a dependent variable (criterion) having two or more categories according to the combination of independent variables (predictors) (cf. Kim et al., Citation2011). The number of categories of independent variables depends on whether or not the results of the Chi-square test are significant, and the integration of variables. SPSS automatically produces the best DT model on the basis of variations of likelihood-ratio Chi-square values when each independent variable is used for building the tree. Here, the most significant independent variable becomes the first node and the procedure of splitting the nodes stops when no significance between the dependent variable and the independent variable is found (Kim et al., Citation2011).

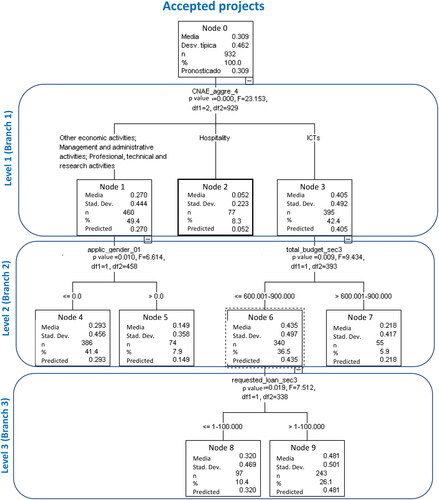

The study tests one model. The dependent variable is the success of the application (SUCCESS). The independent variables are the requested loan, total budget related to the size of the project, CNAE (economic activity), and applicant’s gender. The stopping rules for two CHAID analyses were a maximum tree depth of 4, a minimum of 25 cases for a given node, and significance level for splitting of 0.05. outlines the resulting variables.

The use of DTs is methodologically novel in identifying the gendered dimensions of funding schemes. A published systematic review on gender, entrepreneurship, and tourism (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020) confirms that qualitative methods (47.2%) were more common within tourism entrepreneurship literature, followed by quantitative methods (29.9%). An in-depth examination of the applied quantitative methods shows that DTs were not used in any of the previous publications in tourism, gender, and entrepreneurship, where there was a clear preponderance of descriptive statistics and tests (40.7%) and regression and logistic regressions (28.1%), focusing mainly of individual perceptions towards entrepreneurship.

Methodological limitations from a feminist perspective

Feminist scholars have been critical of quantitative approaches seeking objectivity and truth (Sundberg, Citation2017). Moreover, as we take a quantified approach that categorises tourism entrepreneurs as either, and only, ‘women’ or ‘men’, we potentially obscure certain experiences and reproduce the invisibility of other groups (Rocheleau, Citation1995). Respecting these limitations here, we argue that the lack of information on the gendered aspects of tourism entrepreneurial policy warrants the need to quantify the gendered inequalities in this area, because statistical analysis assists in making visible how gender informs policy outcomes within tourism entrepreneurship.

Results

EMPRENDETUR call characteristics: a gender perspective

In June 2012, the National and Comprehensive Tourism Plan (Plan Nacional e Integral de Turismo, PNIT) (2012–2015) was approved to address the loss of competitiveness in Spain’s mature tourism industry and provide solid foundations for sustainable growth. The priorities of PNIT were to support Spain’s international branding, customer orientation, tourism supply and destinations, encourage public–private collaboration, knowledge management, talent, and entrepreneurship.

Emprendetur comprised four subprogrammes—(a) Young Entrepreneurs scheme; (b) Research and Development (R&D) scheme; (c) Innovative Products; and (d) Internationalisation. The first three schemes were active between 2012 and 2016, while the fourth was only active in 2016. The assistance consisted of reimbursable loans, amortising in 5 years and with a grace period of two years (Cobo-Soler et al., Citation2018).

The Emprendetur programme was designed to foster technological development and innovation for long-term economic growth, which would impact positively on the well-being of society.

The call details of Emprendetur were published in the National Official Bulletin annually, in print and online. The call included the main objectives, applicants’ characteristics, types of projects, evaluation committees and evaluation criteria.

The main finding of a content analysis, from a gender perspective, is that there is no evidence of direct discrimination against women in the call specification. There is a need, however, to consider how prioritisation of certain forms of entrepreneurship led to gendered outcomes in the three main types of calls, which are largely invariant across the years.

A deductive quantitative content analysis showed that the concepts of women or gender are only mentioned once in the three calls: the number of employed women and men in the proposed enterprises is a relevant variable since this information is required in the application forms, although it is not mentioned in the text. Innovation is mentioned in relation to competitiveness and increasing productivity in all the calls: it is mentioned 15 times in the R&D call, 12 times in the young entrepreneurs call and 5 times in the internationalisation call. Technology tends to be considered as integral to the programme since it is referred to as being critical to fostering innovation.

An inductive qualitative content analysis shows that the specific objectives of the R&D, Innovative Products and Young Entrepreneurs programmes were all related to innovation, R&D, and technology. The Internationalisation scheme aimed to support businesses to access international markets, although there was special interest in projects that strengthened the innovative potential of companies, as well as competitiveness and scientific and technological knowledge relating to the tourism sector. The call further highlighted the types of technologically informed projects that were emphasised in the overarching National Tourism Plan (PNIT) ().

Table 2. EMPRENDETUR’s main aims.

The STEM gender gap in the EU-28 countries has been steadily closing in the past decade, with women constituting 40.9% of scientists and engineers in 2019, up from 32.4% in 2009. However, ICTs and high-tech industries are still male dominated, with just 32.5% of employees in these sectors identifying as women in 2019 (Eurostat, Citation2020). Whilst the remit of the funding call was broad, there was clear preference for technological innovation/research in the type of projects supported/funded by these schemes. Women’s underrepresentation within the context of technological innovation/research was thus reemphasised through the funding call, constraining women’s access to Emprendetur.

The criteria that applicants had to fulfil when applying for a grant in the R&D and Innovative Products programmes were quite broad. They had to be Spanish residents and demonstrate financial solvency: ‘…the sum of their assets and rights, including credits against third parties, is greater than the sum of their debts increased by 50%’. For the Young Entrepreneur’s programme, they had to be under 40 years old, although demonstrating financial solvency was not required. For the internationalisation subprogramme, applicants needed ‘to be companies legally incorporated in Spain whose exports did not exceed 40% of their turnover at the time of application’.

For all programmes, the Evaluation Committee comprised five members from five different government organisations: 1. National Tourism Office; 2. Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism; 3. Office for Tourism and Sustainable Development; 4. Office for Cooperation and Tourism Competitiveness; 5. SEGITTUR.

Finally, in three sub-programmes, ‘innovativeness’ was the key criterion during the evaluation process: innovation accounted for up to 40% in the R&D subprogramme, 25% in the Innovative Products programmes and 30% in the Young Entrepreneurs programme. The most important evaluation criteria in the Internationalisation programme was the internationalisation strategy, closely followed by the potential innovation behind the product or service.

Analysis of the applications

Basic characteristics

A total of 932 applications were codified. The number of applications increased significantly over time, from 124 in 2014 to 274 in 2016. Most applications came from the Innovative Products subprogramme (425, 45.6%), followed by Young Entrepreneurs (310, 33.3%) and R&D (131, 11%). Participation in the Internationalisation subprogramme (66, 7.1%) was much lower since it was only active for one year (2016). Most businesses applying were established after 2010 (657, 70.5%) with very few existing before 1990 (93, 10%).

The average funding requested was €249,418 per project with an average total budget of €1,471,953 for the whole project. The size of the requested loans varied enormously, between €1,458 and €1,000,000, while total budgets varied between €3,404 and €1,371,860 illustrating a substantial standard deviation. Nevertheless, most applicants requested under €300,000 (72.4%), followed by requests for €300,001–600,000 (18.8%), whilst only 8.8% of applicants requested more than €600,000. Relatedly, nearly half (48.2%) of the applicants had a total operational budget of less than €300,000, 26.4% had €300,001–600,000 and 25.4% had budgets of more than €600,000.

Following CNAE, most projects were related to ICTs (42.4%), followed by professional activities related to consulting (16.4%) and administrative activities related to distribution and commercialisation (15.7%). Other activities for which funding was sought included wholesale and retail (e.g. food, beverages, and hardware) (5.7%); artistic, recreational, and performing arts activities (3.3%); manufacturing (food, drinks, textiles, clothes, printing and graphic arts, plastic packaging, etc.) (2.4%); and hospitality (8.3%).

A more detailed analysis of the economic activities indicates that although the call specifies the relevance of a range of sectors outlined earlier, applications were biased towards Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) related projects. These constitute 42.4% of applications and 40.5% of funded projects, followed at a distance by professional, scientific, and technical activities, and administrative activities/services (including, car rentals, transportation, human resources management, intermediation and commercialisation, security, research, administrative services, call centres, event management, etc.). There were very few construction (0.3%) or energy (0.2%) projects.

Companies tended to be small (35%) or microenterprises (49.2%), based on the number of employees. In fact, the majority had no employees (13.7%), only 1 employee (21.5%) or two to five employees (30.9%). The limited size of these enterprises was also evidenced by the number of shareholders, with the large majority (77.1%) having between 0 and 3 shareholders, including 13.9% having 0 shareholders and 28.6% having only 1 shareholder.

Finally, most enterprises (33.4%) were based in the largest Spanish urban centres of Madrid (33.4%) and Barcelona (23.5%). In total, 84.1% of the applications were concentrated in 14 of the 50 Spanish provinces.

A gender perspective on the applications

Women made up only 15.4% (143 of 932 applications) of applications during the programme’s entire life cycle. Consequently, women’s participation in all sub-programmes was extremely limited: 19.4% in young entrepreneurs, 16% in R&D, 12% in innovative products and 16.7% in the internationalisation programmes. Whilst these findings supported H1a (Women apply less to funding schemes), the relationship was not statistically significant, although it was close to the limit (p value 0.077). Interestingly, women’s participation did not improve throughout the programme’s five-year lifespan. In fact their participation reached its lowest at the end of the scheme’s lifecycle in 2016 (10.2%), a near 50% decline compared to their participation in 2012, when 19.4% of applications were submitted by women.

Appendix A provides further details on the statistical relationships described hereafter.

The analysis showed that women’s projects were significantly smaller (). Most women applicant’s projects (60.84%) had a total budget under €300,000 (p value 0.000). In terms of company size, women were concentrated in micro and small enterprises (53.2% vs. 48.5% of men) and individual entrepreneurship forms (16.1% vs. 8.2% men); and this is statistically significant (p value 0.01). Consistent with this, the OR shows that men were 72.4% more likely to be in big and medium-sized enterprises (Sig. 0.040). Furthermore, women tended to have significantly fewer employees (p value 0.000): 21.7% of women-led projects had no employees compared to only 12.3% of the men-led projects. The above findings lend credence to H1b (Women apply for funds for smaller projects).

Table 3. Total budget and loan.

In terms of loan amounts requested (), 19.93% more women than men requested loans under €100,000 (p value 0.000). This was confirmed by the OR which indicated that men were 67.5% more likely than women to have submitted applications loans above €300,000 (Sig. 0.02). These results confirm H1c (Women that apply in funding schemes, apply for less money).

Women-led enterprises were significantly more likely (p value 0.002) to be in hospitality (15.4% vs. 7.0%), while men were more likely to lead ICT projects (44.1% vs. 32.9%; statistically significant). The OR further confirmed that men have 61.7% more probability than women of being entrepreneurs in ICT-related organisations (Sig. 0.013). A more balanced distribution between women and men was observed in other activities such as retailing, professional and administration activities. Thus, H1d. (Women are more likely to engage in entrepreneurship projects related to consumer services) was confirmed.

Finally, women’s businesses were significantly more likely to have been established for longer, with 18.8% having been created before 1990, compared to only 8.5% of men’s (p value 0.001). Relatedly, the OR showed that, compared to women, men had 54% less probability of being the applicant of organisations created before 2000 (Sig. 0.010).

Characteristics of successful applications

Men not only made more applications than women, but their applications were significantly more successful: 33.0% (260) versus 19.6% (28) (p value 0.001). According to OR men had 66.9% more probability of being successful than women (Sig. 0.002), confirming H3 (Women are generally less successful than men when applying for funding from gender-neutral funding schemes).

The size of the project clearly influenced the success rate which increased when the total budget was over €300,000 and under €900,000 (p value 0.002). According to the OR, projects with a total budget between €100,001 and 300,000 had 2.168 times greater probability of being successful (Sig. 0.01) and projects with total budgets ranging between €300,001 and 600,000 were 2.069 times more likely to be successful (Sig. 0.02) compared to projects above €900,000. Individual entrepreneurs were far less successful than larger enterprises, with a success rate of 10.2% compared to micro-small enterprises (34.0%), small (32.3%) and big or medium enterprises (33.3%) (p value 0.00). The OR shows that, based on size, all types of businesses were more successful than individual entrepreneurs (). H2a (The size of the project has influence on success) was also confirmed.

Table 4. OR according to size and legal classification.

Directly related to the previous results, the amount of the loan requested clearly influenced the success rate which increased when the loan was over €300,000 and under €900,000 (p value 0.004). Consequently, H2b (The amount of requested money has an influence in success) was confirmed.

Applications from ICT businesses, professional, scientific, and technical activities, and management activities were more successful (40.5%, 30.1%, 28.1% rate of success respectively), whilst the least successful were hospitality applications (5.19%) (p value 0.00), The OR evidenced how non-ICT projects were 2.17 times less probable of being successful (Sig. 0.00). These results confirm H2c (The economic activity has an impact on the success rates). An in-depth analysis shows that a large majority of projects were related to platforms that enhanced the commercialisation of tourism products or services, through personalisation, specialisation or loyalty programs. Technological projects tended to relate to process improvements: payment processes, automatisation, human resources, training, etc. Collaborative platforms were also likely to be supported by this funding scheme: including, for example, online tv, online tourism videos, training, and children caring.

Relatedly, the date of enterprise creation was also significantly related to the success of the application (). The highest success rates were in companies created after 2009, especially between 2010 and 2014 (36.3%) and after 2015 (32.1%), compared to those created 1991–1999 (5.4%) (p value 0.00).

Table 5. OR according to size and legal classification.

Testing a model for successful applications: DT

The tested model () includes those independent variables that have been identified as relevant in the previous statistical analysis in relation to success: economic activity; project size (budget); gender; and the total loan requested. The risk estimate for the model was 0.309 and the error was 0.015, which is acceptable and in line with other studies (e.g., Kim et al., Citation2011).

The most relevant classificatory variable in the DT is economic activity. Following this, the applicant’s gender is important for businesses unrelated to hospitality, while the total budget is important for ICT. The DT ends in the branch for hospitality since the success rate is so low, with just four projects accepted out of 77. In the ICT branch, there is a further step after the total budget, with the requested loan being important.

Level 1 analysis shows that the type of economic activity becomes the root variable, having the highest classification power. This classifies the projects into three branches. The most successful branch is ICT-related, with 395 projects and an above-average success rate of 40.5%. The two other branches, with below-average success rates, are ‘Hospitality’ and the residual ‘Other economic activities’. The ‘Other economic activities’ branch shows a success rate of 27% for 460 projects, whilst hospitality has a very low success rate of 5.2%, with just four of 77 projects accepted.

The second branch (Level 2) is only relevant for the categories ‘ICTs’ and ‘Other economic activities’, due to hospitality being excluded because of its low success rate. Gender is relevant for ‘Other economic activities’ at this second level with men having a higher success rate than women (29.3% compared to 14.9%). Conversely, women’s limited participation, since they only lead 11.8% (47) of ICT projects is likely responsible for the lack of gendered impact evident among ICT projects. Instead, for ICT projects, the second level variable is budget. Interestingly, there seems to be a limitation in the size of the projects this scheme funds, and projects above €600,000 budget are less successful (21.8% vs. 43.5%). A third level of impact is identified only for ICT projects with a small total budget: those requesting a larger loan are more successful (48.1% vs. 32%).

Relationships between gender, size, and economic activity

The analysis has identified that successful projects tend to relate to ICTs, with women being less likely to participate in these types of businesses. Women also generally tend to be more likely to lead smaller companies, which are less likely to be successful in receiving funding.

According to the DT (), the most important variable explaining success is economic activity, followed by size. Even within smaller projects, applications for ICT projects are far more successful (30%) than hospitality projects (2.4%) and other types of economic activities (21.6%). Within ICT, 395 projects were identified and, yet again, the percentage of accepted projects from men was higher than women (41.7% vs. 31.9%), although the relationship was not statistically significant. The OR showed similar results.

As demonstrated earlier, the success rate tended to increase when the total budget was over €300,000 and under €900,000. However, when controlling for size by only analysing those projects over €300,001 (total budget), women’s success rates continued to be lower: they were almost half as likely as men to be successful (16.1% compared to 30.7%) and this was significant (p value 0.023). Furthermore, the OR indicated that men were 2.311 times more successful than women (69.8% probability) in the 483 projects above €300,000 (Sig. 0.027).

Discussion

Emprendetur is far from alone in positioning ‘innovation’ as central in its funding call. Innovation has become a necessary social good and is widely perceived within governments and international organisations as a panacea for responding to socioeconomic challenges (Godin & Vinck, Citation2017). Government policies, and their related funding streams, tend to prioritise ‘innovation’, driven by the generally unquestioned conception that this will inherently lead to increased competitiveness.

Within such conceptions, the dominant representation of innovation is technological (Hall & Williams, Citation2020) or, more specifically, the commercialisation of new technological products (Godin & Vinck, Citation2017). This innovation/technology relationship has strongly developed in recent decades, at the same time as governments have conceptualised innovation as a major growth-orientated economic policy tool (Godin & Vinck, Citation2017; Rodriguez et al., Citation2014). Emprendetur provided no definition of what innovation entails within the funding call, and its documentation did not directly equate innovation with technological innovation. However, the types of potential projects listed as part of the Emprendetur call (e.g. ‘hardware’, ‘machinery’, and ‘equipment’), do indicate that the call indirectly (whether intentionally or unintentionally), aligned with the ‘technological innovation’ paradigm. In consequence, it seems innovation within Emprendetur was largely interpreted as technological and a high number of submissions focused on developing innovative technologies, with those submissions being more likely to be successful.

Whether associations between innovation and technology were intended or not, the prioritisation of innovation within the funding call rendered gendered outcomes. This is because these two concepts have become somewhat synonymous in their meanings whilst, at the same time, women’s access to and engagement with technology is relatively constrained, compared to men’s (Figueroa-Domecq et al. Citation2020). Costa et al., (Citation2017), as well as Belgorodskiy et al., (Citation2012) and Valenduc (Citation2011), have identified that women’s access to technology, both within and beyond tourism, is based on culturally specific gendered norms that have tended to lead to under-representation of women in technology-related industries. Moreover, Holtgrewe (Citation2014) and Valenduc (Citation2011) found that women involved in technology-related endeavours were more likely to be represented in ‘technically soft’ roles—rather than being involved with the ‘innovative’ technology-driven product development activities that tend to be favoured through government-funded schemes.

In considering the social construction of innovation, Shearmur (Citation2017) has suggested that the term is often assumed to be intimately connected to urban areas. This is because the clustered accumulation of networks that are facilitated through cities are thought to generate dynamic interactions and external economies that favour innovation (Kennedy, Citation2011). Whilst there is evidence to support this conceptualisation, its premise reflects an urban bias—whereby urban-based innovative activities are more visible and overvalued, compared to remoter settings which are less visible and taken less seriously (Shearmur, Citation2017). Within Emprendetur, the prioritisation of innovation, coupled with a broader cultural association of innovation with urban enterprises, may have indirectly influenced the urban dominance of applications to the funding scheme: 56.9% of applications came from Madrid and Barcelona alone. The urban bias exacerbates urban/rural divides, limiting the scope for government funding schemes to facilitate the objective of cohesive social and economic territorial development.

Within Emprendetur, new businesses were more successful than older ones. Favouring younger “innovative” firms is negative for women, since in Emprendetur women’s businesses were significantly more likely to have been established for longer. This finding somewhat contrasts with much of the literature, which suggests younger firms find it harder to access finance due to higher perceived risks (cf. Cowling et al., Citation2018; Schneider & Veugelers, Citation2010). The unusual finding within Emprendetur can perhaps again be understood through the funder’s prioritisation of innovation. Novelty, or newness, is the key characteristic of innovation. This conception that new, or younger, businesses are more innovative is not unique to Emprendetur. There is a well-established discourse in economics, where start-ups are seen as drivers of innovation-led productivity gains (Markman et al., Citation2019). In fact, the gap in growth performance between the United States and the European Union has previously been explained by differential start up rates (Schneider & Veugelers, Citation2010). Yet, despite this policy attention within Europe, there is surprisingly limited empirical evidence of the contribution of young businesses to innovation (Schneider & Veugelers, Citation2010), and the evidence from tourism is mixed (Hall & Williams, Citation2020). Nevertheless, the social construction that new businesses have a higher innovation potential provides a feasible explanation as to why new businesses within Emprendetur may have been more likely to be successful despite the recognised higher risks. In doing so, they are fulfilling a market gap that counterbalances the tendency of private sector lenders to favour larger firms, because of their focus on collateral and firm size in the face of information asymmetry (Lehmann & Neuberger, Citation2001).

Women in ICT projects were less successful in obtaining funding than men (31.9% vs. 41.7%) but this difference was not statistically significant. Supporting women to participate in STEM, therefore, seems to be a means to support diversity and inclusion in entrepreneurship. However, supporting women to invest in bigger projects, which have higher funding success rates, does not seem to have the same positive relationship: there seems to be a double gendered disadvantage as their success rates are less than men’s, even when controlling for firm size. These results are not aligned with Tinkler et al. (Citation2015) conclusions about women in masculinised industries such as ITCs, where women are perceived to possess effective leadership and sociability that enable them to navigate such industries, making them highly competent from the perspective of funders.

Another important issue was the request of financial coverage. Women generally have limited access to business funding (e.g. Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019), and have lower salaries and lower quality positions (Santero-Sanchez et al., Citation2015), which again limits their access to funding. A further issue of interest is the limited media coverage the call received, according to a search performed in Google News 2011–2017. As women tend to have more limited access to (professional) networks, this could have reduced their awareness of, and participation in, this call.

Conclusions

Emprendetur was designed to increase the country’s tourism competitiveness, by supporting innovation through supplementing commercial lending. However, the persistent prioritisation of innovation as a driver of competitiveness, coupled with the association of innovation with technology, ensured gendered inequalities were reproduced. This means that this policy in Spain, along with similar policies in many other countries, are at risk of continuing to reproduce, rather than reduce, gendered inequalities in entrepreneurship, with negative implications for maximising potential entrepreneurship and the reproduction of gendered inequalities.

The findings of this study show how women participate less as applicants in the funding scheme and are less successful. This can be explained, in part, because women are more likely to focus on business typologies that are less successful when the applications are assessed. But the barriers extend beyond these typologies; even when controlling for critical success factors like project size, women are less successful, experiencing a double gender gap, that cries out to be solved.

This was a missed opportunity for the Emprendetur funding scheme to respond to structural inequalities. Essentialised definitions of success and high visible impact were prioritised, through favouring technological projects and businesses with a relatively large number of employees. These innovation-led schemes and policies thus reproduce market failure, through the reproduction of gendered social constructions, limiting—even if unintentionally—women’s opportunities. There is a need to review, through a gendered lens, how government entrepreneurial economic and social policies are constructed: in terms of their objectives, design, communication and implementation, and how they address information asymmetries. This is particularly important within a governance context, as governments generally possess remits to reduce structural inequalities.

Importantly, this is not about asking what women can do to enhance their chances in submitting successful applications. Within the conclusions of much of the research on gender, tourism and entrepreneurship, for example, greater education for women is presented as a panacea for all concerns. However, as identified by de Jong and Figueroa-Domecq (Citation2022), whilst education is of course important, the framing of education as all-encompassing solution fails to recognise that women remain underrepresented in tourism leadership and management positions, despite already constituting 53% of bachelor’s and master’s tourism and hospitality graduates globally (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2019). Tourism’s gendered inequalities, and the sustainability of women’s entrepreneurship, do not solely align with education, nor other solutions that focus on what women might be lacking compared to men. Rather—as our findings illustrate—broader structural concerns are overshadowed through the positioning of education as a solution. Such structural concerns need to be rectified through utilising a gendered lens in designing and assessing funding schemes and initiatives (Ngoasong & Lamptey, Citation2021).

These findings have relevance beyond Emprendetur. For example, at a global level the World Tourism Organization, through its Global Report on Women in Tourism (2019), aims to help actors in the private and public sector boost tourism’s empowering potential for women by expanding women’s access to digital technologies. Again, training in technology for women entrepreneurs is proposed as the answer for enhancing women’s access to technology but with limited consideration for the broader structural barriers influencing women’s lower access to technology in many geographical locations (de Jong & Figueroa-Domecq, Citation2022), as a result of varying cultural norms inhibiting access to employment and educational opportunities, and income disparities.

Several future research lines arise from these results. For example, specific assessment of the ‘successful’ business plans submitted as part of this funding scheme through a gendered lens would identify the main strengths of the successful projects. This would also shed light on the main perceived ‘limitations’ of women’s applications. But the evaluation of the gendered nature of project success should not be based only on the immediate outcome of the funding schemes. Taking a longitudinal approach, whereby organisations which received funding were assessed 2–5 years later, would further help to understand the relevance and success of the funding scheme, and the extent to which longer-term outcomes of the funding contribute to gendered inequalities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2021). Exploring the false promise of entrepreneurship through a postfeminist critique of the enterprise policy discourse in Sweden and the UK. Human Relations, 74(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719848480

- Ahl, H., & Nelson, T. (2015). How policy positions women entrepreneurs: A comparative analysis of state discourse in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.002

- Alsos, G. A., Isaksen, E. J., & Ljunggren, E. (2006). New venture financing and subsequent business growth in men–and women–led businesses. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 667–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00141.x

- Peters, L. W. J., & Ateljevic, I. (2009). Women empowerment entrepreneurship nexus in tourism. In J. Ateljevic & S. J. Page (Eds.), Tourism and entrepreneurship (pp. 75–89). Routledge.

- Belgorodskiy, A., Crump, B., Griffiths, M., Logan, K., Peter, R., & Richardson, H. (2012). The gender pay gap in the ICT labour market: Comparative experiences from the UK and New Zealand. New Technology, Work and Employment, 27(2), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00281.x

- Brooks, A. W., Huang, L., Kearney, S. W., & Murray, F. E. (2014). Investors prefer entrepreneurial ventures pitched by attractive men. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(12), 4427–4431. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321202111

- Canton, E., Grilo, I., Monteagudo, J., & van der Zwan, P. (2013). Perceived credit constraints in the European Union. Small Business Economics, 41(3), 701–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9451-y

- Carbo-Valverde, S., Rodriguez-Fernandez, F., & Udell, G. F. (2008). Bank lending, financing constraints and SME investment (Working Paper No. 2008-2004). Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

- Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00078-2

- Castaño, M. S., Méndez, M. T., & Galindo, M. Á. (2016). The effect of public policies on entrepreneurial activity and economic growth. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5280–5285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.125

- Cobo-Soler, S., Fernández-Alcantud, A., Santamaría-García, M., & López-Morales, J. M. (2018). Public support for entrepreneurship, human capital and talent in the context of Spanish tourism. Investigaciones Regionales-Journal of Regional Research, 42, 53–74.

- Coleman, S., & Robb, A. (2009). A comparison of new firm financing by gender: Evidence from the Kauffman Firm Survey data. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9205-7

- Coleman, S., & Robb, A. (2018). Executive forum: linking women’s growth-oriented entrepreneurship policy and practice: Results from the Rising Tide Angel Training Program. Venture Capital, 20(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2018.1419845

- Costa, C., Bakas, F. E., Breda, Z., Durao, M., Carvalho, I., & Caçador, S. (2017). Gender, flexibility and the ideal tourism worker. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.03.002

- Cowling, M., Liu, W., & Zhang, N. (2018). Did firm age, experience, and access to finance count? SME performance after the global financial crisis. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-017-0502-z

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Cziráky, D., Tišma, S., & Pisarović, A. (2005). Determinants of the low SME loan approval rate in Croatia. Small Business Economics, 25(4), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-004-6481-0

- de Jong, A., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (2022). UNWTO’S Global Report on Women in Tourism: tourism’s impact on gender equality. In A. Stoffelen & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Handbook of tourism impacts and impact assessments (pp. 151–165). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Eurostat. (2020). Employment in Technology and Knowledge-Intensive Sectors at the National Level, by Sex (from 2008 Onwards, NACE Rev. 2). Eurostat Database. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-datasets/-/HTEC_EMP_NAT2

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Gender, tourism & entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102980

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2022). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: A gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Palomo, J., Flecha-Barrio, M. D., & Segovia-Pérez, M. (2020). Technology double gender gap in tourism business leadership. Information Technology & Tourism, 22, 1–32.

- Florin, J., Lubatkin, M., & Schulze, W. (2003). A social capital model of high-growth ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 46(3), 374–384.

- Godin, B., & Vinck, D. (2017). Introduction: innovation—From the forbidden to a cliché. In B. Godin & D. Vinck (Eds.), Critical studies of innovation: Alternative approaches to the pro-innovation bias (pp. 1–14). Edward Elgar.

- Grimm, M., Knorringa, P., & Lay, J. (2012). Constrained gazelles: High potentials in West Africa’s informal economy. World Development, 40(7), 1352–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.03.009

- Hall, C. M., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Tourism and Innovation. 2nd ed. Routledge.

- Henry, C., Orser, B., Coleman, S., Foss, L., & Welter, F. (2017). Women’s entrepreneurship policy: A 13-nation cross-country comparison. In T. S. Manolova, C. G. Brush, L. F. Edelman, A. Robb & F. Welter (Eds.), Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth of women’s entrepreneurship: A comparative analysis (pp. 244-278). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Holtgrewe, U. (2014). New technologies: The future and the present of work in information and communication technology. New Technology, Work and Employment, 29(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12025

- Hughes, K. D., Jennings, J. E., Brush, C., Carter, S., & Welter, F. (2012). Extending women’s entrepreneurship research in new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00504.x

- Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.782190

- Jessop, B. (2001). Regulationist and autopoieticist reflections on Polanyi’s account of market economies and the market society. New Political Economy, 6(2), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563460120060616

- Joshi, A., Son, J., & Roh, H. (2015). When can women close the gap? A meta-analytic test of sex differences in performance and rewards. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1516–1545. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0721

- Kanze, D., Huang, L., Conley, M. A., & Higgins, E. T. (2018). We ask men to win and women not to lose: Closing the gender gap in startup funding. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 586–614. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1215

- Kennedy, C. (2011). The evolution of great world cities. University of Toronto Press.

- Kim, S. S., Timothy, D. J., & Hwang, J. (2011). Understanding Japanese tourists’ shopping preferences using the Decision Tree Analysis method. Tourism Management, 32(3), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.04.008

- Kimbu, A. N., de Jong, A., Adam, I., Ribeiro, M. A., Afenyo-Agbe, E., Adeola, O., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (2021). Recontextualising gender in entrepreneurial leadership. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103176

- Kimbu, A. N., Ngoasong, M. Z., Adeola, O., & Afenyo-Agbe, E. (2019). Collaborative networks for sustainable human capital management in women’s tourism entrepreneurship: The role of tourism policy. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1556329

- Krippendorff, K. (1989). Content analysis. In E. Barnouw, G. Gerbner, W. Schramm, T. L. Worth, & L. Gross (Eds.), International encyclopedia of communication. (Vol. 1, pp. 403–407). Oxford University Press.

- Lehmann, E., & Neuberger, D. (2001). Do lending relationships matter?: Evidence from bank survey data in Germany. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 45(4), 339–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00151-2

- Levenson, A. R., & Willard, K. L. (2000). Do firms get the financing they want? Measuring credit rationing experienced by small businesses in the US. Small Business Economics, 14(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008196002780

- Lorber, J. (2010). Gender inequality. Oxford University Press.

- Markman, G. D., Gianiodis, P., Tyge Payne, G., Tucci, C., Filatotchev, I., Kotha, R., & Gedajlovic, E. (2019). The who, where, what, how and when of market entry. Journal of Management Studies, 56(7), 1241–1259. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12448

- Micelotta, E., Washington, M., & Docekalova, I. (2018). Industry gender imprinting and new venture creation: The liabilities of women’s leagues in the sports industry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(1), 94–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717732778

- Mina, A., Di Minin, A., Martelli, I., Testa, G., & Santoleri, P. (2021). Public funding of innovation: Exploring applications and allocations of the European SME Instrument. Research Policy, 50(1), 104131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104131

- Morris, M. H., Miyasaki, N. N., Watters, C. E., & Coombes, S. M. (2006). The dilemma of growth: Understanding venture size choices of women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00165.x

- Ngoasong, M. Z., & Kimbu, A. N. (2019). Why hurry? The slow process of high growth in women‐owned businesses in a resource‐scarce context. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12493

- Ngoasong, M. Z., & Lamptey, R. O. (2021). Gender lens investing in the African context. In E. de Morais Sarmento & R. P. Herman (Eds.), Global handbook of impact investing: Solving global problems via smarter capital markets towards a more sustainable society (pp. 273–302). Wiley.

- Orser, B. J., Hogarth-Scott, S., & Riding, A. L. (2000). Performance, firm size, and management problem solving. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(4), 42–58.

- Pooja, K. M., Mondal, S., & Chandra, J. (2021). Exploiting similarities across multiple dimensions for author name disambiguation. Scientometrics, 126(9), 7525–7560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04101-y

- Porobić Isaović, N. (2018). A WILPF guide to feminist political economy. from https://www.wilpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/WILPF_Feminist-Political-Economy-Guide.pdf.

- Rocheleau, D. (1995). Maps, numbers, text and context: mixing methods in feminist political ecology. The Professional Geographer, 47(4), 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1995.00458.x

- Rodriguez, I., Williams, A. M., & Hall, C. M. (2014). Tourism innovation policy: Implementation and outcomes. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.004

- Rondović, B., Djuričković, T., & Kašćelan, L. (2019). Drivers of E-business diffusion in tourism: A decision tree approach. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 14(1), 30–50.

- Roper, S., & Scott, J. M. (2009). Perceived financial barriers and the start-up decision: An econometric analysis of gender differences using GEM data. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 27(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608100488

- Santero-Sanchez, R., Segovia-Pérez, M., Castro-Nuñez, B., Figueroa-Domecq, C., & Talón-Ballestero, P. (2015). Gender differences in the hospitality industry: A job quality index. Tourism Management, 51, 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.025

- Schneider, C., & Veugelers, R. (2010). On young highly innovative companies: Why they matter and how (not) to policy support them. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 969–1007. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtp052

- Schram, A. B. (2014). A mixed methods content analysis of the research literature in science education. International Journal of Science Education, 36(15), 2619–2638. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2014.908328

- Shearmur, R. (2017). Urban bias in innovation studies. In H. Bathelt, P. Cohendet, S. Henn, & L. Simon (Eds.), The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, pp. 440–456.

- Silva, F., & Carreira, C. (2010). Financial constraints: Are there differences between manufacturing and services?. (Working Paper No. 2010-16). GEMF, Faculty of Economics, University of Coimbra.

- Sundberg, J. (2017). Feminist political ecology. In The international encyclopedia of geography: People, the earth, environment and technology. Taylor & Francis, pp. 1–12.

- Tellhed, U., Bäckström, M., & Björklund, F. (2018). The role of ability beliefs and agentic vs. communal career goals in adolescents’ first educational choice. What explains the degree of gender-balance? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.09.008

- Tinkler, J. E., Whittington, K. B., Ku, M. C., & Davies, A. R. (2015). Gender and venture capital decision-making: The effects of technical background and social capital on entrepreneurial evaluations. Social Science Research, 51, 1–16.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2019). Global report on women in tourism. UNWTO.

- Valenduc, G. (2011). Not a job for life? Women’s progression, conversion and dropout in ICT professions. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 3(2), 483–500.

- Werner, M., Strauss, K., Parker, B., Orzeck, R., Derickson, K., & Bonds, A. (2017). Feminist political economy in geography: Why now, what is different, and what for? Geoforum, 79, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.11.013

- World Bank. (2016). Women, business and the law 2016. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the World Bank.

- Xiong, X., Fu, R., Zhang, W., Zhang, Y., & Xiong, L. (2011). The research on the influencing factors of financing strategy of woman entrepreneurs in China. Journal of Computers, 6(9), 1819–1824. https://doi.org/10.4304/jcp.6.9.1819-1824

- Yacus, A. M., Esposito, S. E., & Yang, Y. (2019). The influence of funding approaches, growth expectations, and industry gender distribution on high‐growth women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12491

- Zin, M. L. M., & Ibrahim, H. (2020). The influence of entrepreneurial supports on business performance among rural entrepreneurs. Annals of Contemporary Developments in Management & HR, 2(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.33166/ACDMHR.2020.01.004