Abstract

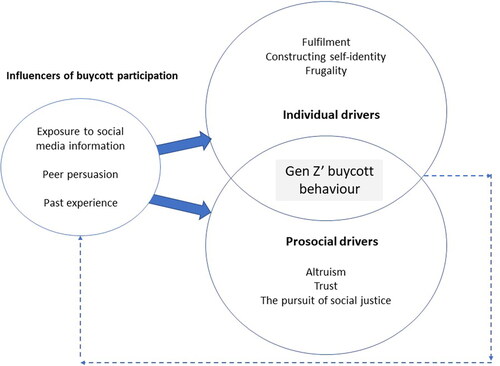

Generation Z (Gen Z) is the largest cohort of generational consumers worldwide and is perceived to show greater connectivity with political consumerism compared to older age cohorts. Nonetheless, there is a notable absence of empirical knowledge on key antecedents of Gen Z’s engagement in tourism-related buycotting. Grounded in political and ethical consumerism literature and guided by lifestyle politics theory, this study aims to illuminate the drivers underpinning buycott behaviour of Gen Z in a developing country context. The qualitative findings demonstrate that Gen Z’ buycott behaviour has two categories of drivers: individual (fulfilment, constructing self-identity and frugality) and prosocial (altruism, trust and the pursuit of social justice). Exposure to social media information, peer persuasion and past experience are also key influencers in Gen Z’ buycott participation. Overall, the research extends the understanding of tourist sustainable consumption in terms of generational behaviours, notably Gen Z’s buycott behaviour. The study provides novel insights to a stream of the political consumerism literature, which is only at a nascent stage in tourism studies. While adding value theoretically, the study also provides useful managerial implications for businesses to stimulate tourists’ political and ethical consumption.

Introduction

Sustainability is an important consideration in the consumption decision-making of many generational cohorts (Gardiner et al., Citation2015; Prayag et al., Citation2022). Successful implementation of sustainability requires the active participation of individuals from different generations of society (Hall, Citation2019). When it comes to purchasing choices and consumption, each generation has new perspectives and demands. Hence, understanding generational consumption practices and behaviours is under increased scrutiny across a range of academic fields (e.g. Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022). Gen Z (usually described as those born between mid-to-late 1990s and the early 2010s) has emerged “as the largest and most challenging consumer group” for destinations (European Travel Commission, Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2022). Comprising more than one-third of the global population and with purchasing power five or six times that of prior generations, Gen Z has become a segment of great business interest (Sakdiyakorn et al., Citation2021; Jiang & Hong, Citation2021; Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2022).

Notwithstanding the economic importance of this generation, knowledge of Gen Z and tourism stands in marked contrast to other market segments (e.g. Generation Y (millennials) or seniors’ tourism). Owing to the exposure to social media platforms, Gen Z are regarded as “digital natives” because they grew up in a more connected environment than prior generations (Francis & Hoefel, Citation2018; Stavrianea & Kamenidou, Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2022) and, as Casalegno et al. (Citation2022) note, digital technologies significantly shape the environmental behaviour of this cohort. This generation’s purchasing behaviour and lifestyle preferences may vary from those of previous generations in terms of ethical and responsible consumption choices (Robinson & Schänzel, Citation2019; Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022; Salinero et al., Citation2022; Lin et al., Citation2022). Growing evidence suggests that Gen Z are aware of environmental and sustainability issues (Sharpley, Citation2021; Prayag et al., Citation2022; Salinero et al., Citation2022), and engage in political consumerism (Seyfi et al., Citation2022; Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022).

Political consumerism refers to the expression of political beliefs and ethical values via the purchasing of goods or services (Copeland & Boulianne, Citation2022; Stolle et al., Citation2005). After voting, political consumerism is regarded as the most popular form of political involvement in many Western countries (Van Deth, Citation2016). Boycotting and buycotting are the two most common forms of political consumption (Stolle et al., Citation2005; Stolle & Micheletti, Citation2013). In contrast to boycotts, which try to punish businesses for unethical practices by not purchasing a product or campaigning against a product, destination, or organization (Shaheer et al., Citation2019, Citation2021), buycotts include the intentional purchase of specific brands or products to reward or the recommendation of companies or products for their desirable behaviour (Stolle et al., Citation2005). Arguably, even though buycotts are increasingly prevalent (Neilson, Citation2010), the existing tourism literature has primarily focused on boycotts (e.g. Shaheer et al., Citation2019, Citation2021,Citation2022; Yu et al., Citation2020; Seyfi & Hall, Citation2020; Seyfi et al., Citation2021; Shepherd, Citation2021).

Previous research suggests that the determinants of boycotting and buycotting behaviours should be fairly distinct (Copeland, Citation2014) and researchers have been called upon to further investigate consumers engagement in buycotting (Nielson, 2010; Hoffmann et al., Citation2018). Although scholarly interest in Gen Z is increasing, the buycott behaviour of this cohort is yet to be explored empirically. Extant literature research on political and ethical consumerism has mainly focused on economically developed countries and those with democratic systems of government (e.g. Stolle et al., Citation2005; De Zúñiga et al., Citation2014; Gregson & Ferdous, Citation2015). However, the politics of ethical consumption varies significantly among societies and different consumer cultures have different motives and values driving ethical consumption (Sudbury Riley et al., Citation2012). Despite the growing ethical dimensions of consumption among the middle classes in developing societies, there is limited research on buycotting behaviour in such regions. As Walsh et al. (Citation2010) argue, cultural and political differences affect customers’ ethical decision-making and responses to ethical marketing. This echoes the call of a number of scholars for further research to explore ethical consumption behaviours in different cultures (e.g. Sudbury Riley et al., Citation2012; Weeden & Boluk, Citation2014).

This study focuses on Iran which, despite a number of economic, political and social issues, especially arising from sanctions, has nevertheless seen the emergence of a growing middle class (Seyfi & Hall, Citation2018). This has also contributed to the development of political consumption and activism, particularly from urban youth, because of ICT developments (Salehi et al., Citation2021), especially the growth in social media (Faris & Rahimi, Citation2015). For example, a report on the use of social media by Iranian Gen Z suggested that they “basically have a protesting nature toward current conditions,” and “the role of Gen Z in shaping the country” and “future domestic and foreign policies” is increasingly recognized (Sobhe Sadegh, Citation2021). This generation has also been at the forefront of recent political protests in support of women freedom in Iran (Bizaer, Citation2022).

Drawing on a sample of Gen Z in a developing country context, the study aims to answer this key question: What are the underlying motivations driving buycott behaviors of Gen Z?. The contributions of this study are threefold. First, the core contribution of this research lies in illuminating the drivers underpinning tourists’ buycott behaviours, hence enriching scant understanding of this in the tourism literature. Second, this study focuses on Gen Z as an important growing travel market and expands empirical research about tourist sustainable consumption from a generational perspective. Third, this research responds to previous calls for more empirical evidence of political and sustainable consumption behaviours among Gen Z within different cultures, hence laying the groundwork for future comparative cross-cultural studies on the topic.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Following the conceptualization of buycott, work related to Gen Z’s buycott behaviour is reviewed which is then followed by describing lifestyle politics theory as the theoretical lens of the study. The study methodology is then presented in Section 3. The research findings are discussed in Section 4 followed by concluding remarks, implications, and directions for further research in the final section.

Literature review

Conceptualizing buycott

In a seminal work, Micheletti (Citation2003) defined political consumerism as “actions by people who make choices among producers and products with the goal of changing objectionable institutional or market practices. Their choices are based on attitudes and values regarding issues of justice, fairness, or noneconomic issues that concern personal and family well-being and ethical or political assessment of favourable and unfavourable business and government practice” (p.3). This definition of political consumerism is inclusive of reasons ranging from personal and ethical to those that are overtly political (Stolle et al., Citation2005). Political consumerism is often viewed as an alternative mode of political/civic engagement (Copeland & Boulianne, Citation2022) which, as a form of “lifestyle politics,” allows individuals to address personal and political issues pertaining to quality-of-life concerns beyond electoral politics (Copeland, Citation2014).

Buycotting encourages businesses to acting in accordance with corporate social responsibility (CSR) objectives or exert pressure on companies who have neglected CSR to alter their practices (Stolle & Micheletti, Citation2013). Exercising choice in this way generates incentives for businesses or service providers to align their practices to customer values (Stolle et al., Citation2005). According to Copeland (Citation2014), boycotting is related to “dutiful citizenship norms” and shares characteristics with electoral, interest-based politics owing to its punitive nature. Buycotting, on the other hand, is more strongly associated with “engaged citizenship” norms and has more in common with civic engagement due to being reward-oriented.

Friedman (Citation1996) conceptualized buycott as a positive dimension of boycotting that “attempt to induce shoppers to buy the products or services of selected companies in order to reward them for behaviour which is consistent with the goals of the activists” (p.440). Micheletti and Stolle (2005) defined buycotts more simply as politically motivated purchasing and shopping. While Stolle et al. (Citation2005) regard buycotting an act of political consumerism, other research view buycotting as expressions of ethical consumption (Hoffmann & Hutter, Citation2012); moral self-realization (Brunk, Citation2010); identity and values expression (Neilson & Paxton, Citation2010); prosocial behaviour (Newman & Bartels, Citation2011); and consumer empowerment (Shaw et al., Citation2006) that, as Baek (Citation2010) argues, reflect historical trends driving social change. Nonetheless, despite the growing body of research on buycotts, there is a dearth of knowledge on its generational dimensions (Seyfi et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, and most importantly in the generational context, Gen Z is believed to support positive ethical action by actively engaging in pro-sustainability practices (Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022; Prayag et al., Citation2022; Seyfi et al., Citation2022; Lin et al., Citation2022). Nonetheless, the drivers of buycotting behaviours among Gen Z tourists has not been previously assessed which points to the main focus of the present study.

Understanding Gen Z buycott behaviour

According to generational theory, each generation has distinctive expectations, experiences, and history that reflect generations’ lifestyles and attitudes (Strauss & Howe, Citation2009) which in turn, influence cohort consumption behaviour (Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022; Salinero et al., Citation2022). The generational behaviour of tourists is of theoretical and practical significance. For example, Gardiner et al. (Citation2015) examined the similarities and differences across generations in the decision-making process of Australian domestic tourists. Similarly, Chen et al. (Citation2021) explored generational disparities in New Zealand residents’ attachment to local communities.

Being born into a generation that has grown up with digital media and the Internet (Stavrianea & Kamenidou, Citation2022), together with socio-cultural and political change, has influenced the development of a Gen Z cohort that, in terms of attitude, appears passionate about a wide range of global issues such as climate change, social justice and sustainability (Sakdiyakorn et al., Citation2021; Salinero et al., Citation2022; Prayag et al., Citation2022). Recent research suggests that younger generations are cognitively interpreting their political, environmental and social concerns into expressed purchase behaviour and seeking out and paying more for ethical products (Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022). Haddouche and Salomone (Citation2018) demonstrated that Gen Z is sensitive to the concept of sustainable tourism, as shown by their environmental habits. Sharpley (Citation2021) asserts that Gen Z serves as the spearhead of a consumer transition towards more sustainable tourism. Robinson and Schänzel (Citation2019) also argued that environmental aspects of a destination are crucial to the travel experience of Gen Z. In a similar vein, Lin et al. (Citation2022) focused on Gen Z’s environmental pursuits and reported eudaimonic pursuit in shaping their sustainable tourism consumption. Casalegno et al. (Citation2022) also noted that Gen Z are more concerned about rising environmental issues than previous generations; a conclusion also reported by Prayag et al. (Citation2022) and Salinero et al. (Citation2022). However, this contradicts the findings of Qiu et al. (Citation2022) who found that Gen Z is less likely than prior generations to engage in environmentally responsible travel behaviours. Interestingly, research in other disciplines showed that while Gen Z holds strong environmental beliefs and attitudes, they tend to have lower engagement in actual environmental practices than older age cohorts (Giachino et al., Citation2022; Parzonko et al., Citation2021).

A growing number of studies indicate that younger people are more likely to adopt a lifestyle based on the principles of sustainability (e.g. Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022; Salinero et al., Citation2022; Prayag et al., Citation2022). For instance, in their study focusing on the retailing sector in Romania, Dabija et al. (Citation2020) reported that Gen Z has a strong interest in sustainable development and social responsibility and wish to participate in environmental protection activities. Similarly, Last (2014) showed that Gen Z tend to purchase products from companies that apply sustainability principles and want to reduce their carbon footprint. However, this does not mean that Gen Z is necessarily willing to adopt new sustainable products. Therefore, understanding Gen Z travelers, their concerns, and motivations, is critical to assessing how changes in tourism demand could evolve. Furthermore, the continuation of such behaviours over time has significant long-term implications for tourism businesses and how they incorporate sustainability into their business model, especially given the size of the Gen Z market (European Travel Commission, Citation2020).

Theoretical approach: lifestyle politics theory

De Moor (Citation2017, p. 181) defines lifestyle politics as “the politicization of everyday life, including ethically, morally, or politically inspired decisions.” Micheletti and Stolle (Citation2012) argue that lifestyle politics refers to “an individual’s choice to use his or her private life sphere to take responsibility for the allocation of common values and resources, in other words, for politics” (p. 126). Haenfler et al. (Citation2012) argue that lifestyle politics refers to collectives who promote a particular lifestyle “as their primary means to foster social change” (p. 2). Lifestyle politics theory is grounded on discussions of modernisation, individualisation, and value change which imply that broad societal changes, including globalisation, have led to the dismantling of conventional institutions and a growing focus on self-reflexivity and political expression (Newman & Bartels, Citation2011). This echoes de Moor’s (Citation2017) argument that “lifestyle politics depart from a realisation that one’s everyday decisions have global implications, and that global considerations should therefore affect lifestyle choices” (p. 180).

Drawing on extensive digital media use, lifestyle politics tend to be spontaneous and targets multiple actors (Bennett, Citation1998, Citation2012) in order to promote social changes by encouraging politically inspired lifestyle choices (Stolle & Micheletti, Citation2013). People who engage in lifestyle politics see daily consumption choices as political statements (Bennett, Citation1998, Citation2012) in which politics permeates non-political areas of our everyday lives (Endres & Panagopoulos, Citation2017). Thus, lifestyle politics refers to the politicisation of daily life decisions, in terms of ethically or politically motivated choices regarding, for instance, consumption or styles of living (Micheletti, Citation2003; Wahlen & Laamanen, Citation2015). Given its focus, the field of lifestyle politics potentially offers useful insights for advancing our understanding of buycotting behaviour by Gen Z as a sustainability-oriented generation. Drawing on lifestyle politics theory and using Iran as a case study, this study therefore aims to identify the key antecedents to the Gen Z cohort’s participation in tourism buycotting practices.

Methodology

Research design

The primary emphasis of this research is to gain an in-depth understanding of Gen Z’s buycott behaviour in a developing country context. An exploratory qualitative research approach that originates from an interpretivist approach is therefore used for data collection and analysis (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Qualitative research provides in-depth and rich information for studying highly contextualised and personal consumer, lifestyle and political perspectives, hence allowing for an improved initial understanding of the phenomena being studied and its various influences (Hennink et al., Citation2020; Maxwell, Citation2009). Given the exploratory nature of this study and due to buycotting potentially having various meanings for different persons, semi-structured interviews were deemed appropriate for the study’s aims (Kallio et al., Citation2016). Semi-structured interviewing is most closely associated with the interpretivist historical tradition in the social sciences (Lewis-Beck et al., Citation2004), and “reflects an ontological position that is concerned with people’s knowledge, understandings, interpretations, experiences, and interactions “(Lewis-Beck et al., Citation2004, p. 1021). Semi-structured interviews encourage active participant engagement and enable a better and deeper understanding by enabling interviewees to expand on their experiences due to their open-ended nature and flexibility to ask probing questions (Kallio et al., Citation2016; Creswell & Poth, Citation2018).

Data collection

The lead author collected and analysed the data and made use of his personal connections and membership on social media networks to access participants. The participants were asked their previous experience, if any, in supporting tourism and hospitality related businesses due to desirable ethical, environmental, political, rights or social issues. To ensure participants meet the study’s requirements, as the screening pre-interview phase, only those who had at least one previous buycott experience with tourism-related products or services and aged 18-25 were asked to participate in our interviews. Follow-up contacts were then made to interested and eligible participants via email, messages on different social media and platforms such as Telegram and WhatsApp. This purposive sampling allowed the selection of respondents who were familiar with the context of the study and could “purposefully inform an understanding of the research problem” (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018, p. 285).

Using exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling, more participants were recruited by asking those who were initially contacted to recommend persons who might be interested in participating in an interview. This sampling technique was regarded as most appropriate for getting a sample suitable for this investigation (Flick, Citation2018). Nevertheless, as a non-probability sampling method, snowball samples are liable to potential sampling bias and should not be regarded as representative of a target population to make generalisations about (Given, Citation2008), despite being an effective method for reaching out to hidden or difficult-to-reach populations (Biernacki & Waldorf, Citation1981; Given, Citation2008) of Gen Z in Iran. The two methods of sampling helped to capture a wide variety of perspectives from Gen Z regarding the buycotting engagement. In order to comprehend the uniqueness of the examined phenomenon and its circumstances, qualitative research often employs a highly focused small sample (Flick, Citation2018). This study adhered to the idea of 'data saturation,' which refers to the moment in the research process when more interviews provide no more or only little new information (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Saturation was reached after 26 interviews and interviewing was considered as completed.

Before commencing interviews, interviewees were given an introduction to the objective of the research. The first part of interviews consisted of questions pertaining to demographic information ().

Table 1. Profile of study participants.

Participants were asked to recount their prior buycott experiences in depth (i.e. Can you discuss this in more detail?) and the underlying motivations that lead to their buycott behaviours (i.e. why did you engage in buycotting? How were your feelings and emotions when having buycott experiences?). Questions were proposed in a way to allow participants to explain their experiences in their own terms.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted using WhatsApp, Skype, Teams, or Zoom depending on the preferences of respondents and their accessibility. The flexible data collection process was necessary given that participants were located in different parts of the country. The use of new Internet technologies as a research medium has been acknowledged in studies conducted during the pandemic and such media are more suitable for politically sensitive topics (Hall, Citation2010) and some hard-to-reach or geographically scattered populations (Hanna, Citation2012). The interviews lasted 45 minutes on average and were conducted in Farsi, and back translated into English by the first author.

Data analysis

In accordance with using an interpretive research paradigm, qualitative thematic analysis was used for data analysis. Thematic analysis is applicable to a range of epistemologies and research questions (Nowell et al., Citation2017) and is an appropriate method for summarising key features of a large data set. It is also valuable for interpretivist research that seeks a more nuanced comprehension of empirical data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The five steps of analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) (date familiarisation, initial code generation, thematic search, thematic reviewing, and theme defiinition and naming) were followed to direct data analysis. The interviews were transcribed after being read several times and initial ideas were noted. Key ideas were underlined and noted for each transcript. After familiarisation with the data, preliminary codes were identified. The relevant data extracts were then categorised in accordance with the overarching themes. They were then re-read several times to ensure accurate coding and thematic categorisation. The next step involved further refining and defining of the themes and potential sub-themes to identify patterns within the data, and sorting into thematically distinct groupings.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the research, Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) principles were used. Regarding credibility, the triangulation approach was used to assure a diversified data source (respondents recruited from various regions of the country) and a sufficient amount of time given for data collecting (interviews from December 2021 to March 2022). Investigator triangulation was used through the authors continuous conversation of the codes and the findings. Peer debriefing was also used to discuss the study design, interview questions, and results with the authors. To ensure dependability and reliability, member checking was used and some of the study participants were provided with a brief summary of the findings and copies of interview transcripts for checking, and their opinion was asked (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985).

Findings and discussion

This section details the results of interviews with Gen Z to gain more detailed perspectives on their buycott experiences. The following common themes and patterns that emerged are depicted in .

Theme 1: influencers of buycott participation

Before making a choice, respondents indicated that they were influenced by a variety of factors that led them to engage in buycotting. A buycott decision is influenced by an individual’s personal and social obligations, which allude to the negative and positive consequences of their consumption choices (Hoffmann et al., Citation2018). Despite the fact that a feeling of responsibility often motivates buycotting, some triggers are also influenced by buycott awareness, particularly in the initial stage of decision-making. These are explained below.

Exposure to social media information

The usage of social media is a significant characteristic of Gen Z in terms of personal connections and relationships, as well as consumption behaviours, particularly with regard to e-word of mouth and readiness to offer feedback and ratings (Han et al., Citation2021). Participants repeatedly mentioned the significant influence of social media on their buycott engagement. Many noted that social media was the source of information that made them aware of ethical issues. This was most evident with several participants expressing that when they encountered information about the ethical activities of firms, they were motivated to reward them by purchasing their goods or services.

I have seen a lot of campaigns on social media to help businesses that are environmentally conscious. When I decide to support such businesses, I often look at what the media says about it…. I think they are very helpful for getting the word out (Interview #4).

I saw a post on Instagram about a tour operator that promotes sustainable travel to the south of Iran… This motivated us to book a hotel via their system when we travelled to the southern Island with family (Interview #9).

…I think social media and messaging app really help to learn about such sustainable activities of travel agencies in Iran. I have personally learnt about such tour operators on message app such as Telegram and decided to participate in pro-sustainable tours (Interview #14).

The above also corroborates previous studies that suggest Gen Z travel behaviours and consumption patterns are substantially shaped by technological innovations such as social media (Wee, Citation2019). Social media has been identified as an effective communication channel to encourage pro-sustainable tourism and ethical consumption behaviours among Gen Z (Robichaud & Yu, Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2022; Salinero et al., Citation2022). Evidence suggests that exposure to information about businesses that affect to individuals’ political and ethical values is an integral component of political consumerism (Stolle & Micheletti, Citation2013; Seyfi et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). Liu et al. (Citation2022) noted that social media is particularly relevant for Gen Z. When social media publicises acts of buycott and spreads it, participation in buycotting is encouraged among Gen Z who is communicatively reliant on these networks (Stavrianea & Kamenidou, Citation2022; Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022). This suggests that buycotts are more likely to include informal learning, whereby individuals learn about companies or services that align with their beliefs via the news media or direct advertising by corporations (Copeland, Citation2014). The findings of this study are consistent with lifestyle politics theory, which posit that social media use influences buycott behaviour (e.g. Kelm & Dohle, Citation2018; Seyfi & Hall, Citation2020).

Peer persuasion

Peer persuasion is widely acknowledged as a significant influencer for buycott participation (Nielson, 2010; Copeland, Citation2014). This was evident where several participants noted that their buycotting decisions were substantially influenced by the persuasion of their friends:

I learnt from a friend of mine who had stayed with his family in a green hotel in Kish Island. There was a debate on social media to support this hotel and other green hotels and many of my friends who I trust in their judgement and way of thinking supported this hotel and encouraged me to do whatever I can to support such ecohotels (Interview #11).

If I see that my friends participate in a buycott and support a business, I’ll do the same. (Interview #8).

Past experience

Prior experience of buycotting emerged as a theme with a number of participants expressing that their past experience helped them to easily engage in buycotting. This reiterates arguments made in the literature that familiarity obtained via earlier experience affects long-term connections and drives re-consumption (Kwun & Oh, Citation2007; Seyfi et al., Citation2021).

I had participated in a call for buycotting a travel agency for its sustainable policies, when I saw new calls, I usually support it because I know the rationale behind it (Interview #17).

I always buy locally made products and souvenirs from the same store whenever I travel to Kish. I trust the owner of this store and his commitment to empower local women handicraft (Interview #5).

These comments are also consistent with the claim of Seyfi et al. (Citation2021), also writing in the Iranian context, who reported that participation in sustainability-related tourism activism tends to occur as the result of a process-based continuous practice instead of just a one-time participation. In fact, there is a sort of “career ladder” for political activism (Abramowitz & Nassi, Citation1981) by which previous experience acts as a significant predictor of future consumption practices and ethical engagement of consumers, particularly if the experience has been felt by the participant to be a success (Kwun & Oh, Citation2007).

Theme 2: individual-level drivers

Interview analysis indicated that Gen Z buycott behaviours are often substantially the result of strongly held personal values and motives. Three themes emerged to explain Gen Z’s buycott decisions:

Fulfilment

The study participants expressed that they had feelings of fulfilment when buycotting. This is in line with the arguments made in the literature that buycotting is typically related with feelings of positive fulfilment and pleasure when consumers match their own needs with their moral commitments and values (Soper, Citation2008; Hoffmann et al., Citation2018).

When I support environmentally-friendly businesses, it provides me with joy. As if I am positively impacting the planet in my own way (Interview #13).

We often use the day excursions to closer destinations promoted by travel agents during the weekend, which may have a significant influence on our carbon footprint… I often feel positive when I get home (Interview #22).

Several participants believed that their choice to participate in buycotting was influenced by the company’s values coinciding with their own. In this instance, individuals engage in buycotting to obtain personal fulfilment. This indicated that if a person felt connected to more widely public values and environmental issues, fulfilment would increase the chance of buycotting, as buycotting provides consumers with a sense of pleasure when purchasing in what they regard as a positive fashion. Additionally, several respondents said that they are inspired to buy from companies that align with their self-image and beliefs: “I am so much more confident in myself and my purchase. I mean I am consciously aware of it” (Interview #2), “I believe it simply helps me feel happier” (Interview #6), “It is important to me to engage in activities that bring me joy” (Interview #12).

The above findings show that buycotting is a pleasure and fulfilment-seeking behaviour and buycotts help Gen Z to incorporate self-interest and societal obligation into their consumption. This finds support in previous studies. For example, Hoffmann et al. (Citation2018, p. 7) reported that hedonic consumers considered buycotting as “an action that helps to harmonise their interests at the societal level and at the personal level” . In a similar vein, Tomhave and Vopat (Citation2018) found that some customers engage in buycotting because they wish to meet their moral obligations to effect change. The findings lend support to the notion that a “moral turn” emphasises that consumers may be fulfiled by not just caring for “their own” and people close by, but also for distant strangers (Malone et al., Citation2014).

Constructing self-identity

Self-identity was another motive for interviewees to engage in buycotting. They mentioned that their decision to purchase ethical products is influenced by their self-perception and the association of the product with their identity and personal ethics. This confirms the argument of Boström et al. (Citation2019) that consumption plays a major role in the formation and reinforcement of personal identities. According to Liu et al. (Citation2022), consumption has become a form of self-expression for Gen Z and this cohort is more inclined than millennials to seek products and services that reflect their self-identity.

My friends and I joined and supported the national campaign to introduce and travel to Sistan and Baluchestan [a province in the south-east of Iran] and promoted local handicrafts on Instagram…. so I can say that I have acted ethically, and I believe that I am the type of person who wants to assist local people in peripheral destinations (Interview #19)

Supporting a small business in a village may not change the whole picture… whenever I spend money in locally owned businesses and share the pictures of small hotels in villages, I feel good about myself, and one day my actions maybe create positive change (Interview #10).

I belong to a generation that we know we’re destroying the world… For me it is very important to travel responsibly and if possible I often use my bike…I believe my actions even small help to save the planet (Interview #15).

This finding corroborates previous works indicating that political consumption reflects personal identity and lifestyle (e.g. Shah et al., Citation2007; Baek, Citation2010). Lifestyle politics theory also posits that appealing to identity plays a crucial role in mobilising ethical consumption (Baek, Citation2010). Klein et al. (Citation2004) argued that customers want to boost their self-esteem, and buycotting as a moral act assists them in doing so. Typically, a feeling of responsibility and sense of obligations motivate buycotting. Society and environment have an important influence in the formation of personal values that foster ethical consumption. Thus, Chatterjee et al. (Citation2021) argue, creating a society whose aims align with the concept of constructing a just and fair world can influence construction of self-identity and ethics which in turn lead to ethical consumption. The study of Lin et al. (Citation2022) on eudaimonic environmental pursuit of Gen Z also revealed that green volunteer trips induced a feeling of internal transcendence and self-respect in this generation.

Frugality

The analysis of interviews also showed that Gen Z’ers tend to engage in ethical consumption behaviours. De Young (Citation1986) defined consumer frugality as “careful use of resources and avoidance of waste” (p. 285) which in other words mean the careful use of both financial and physical resources. Gen Z in general is often regarded as a more frugal and fiscally responsible group with their own unique consumption behavioural characteristics (Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022). Consumer frugality may play an essential role in encouraging the purchase of green products (Schaefer & Crane, Citation2005). Some of the study participants mentioned that they have become more frugal travellers as a result of practicing responsible travel. They stated:

I do not have a high salary that requires me to travel on a budget. I prefer staying and support locally-owned eco-friendly hotels. It is always cheaper than big hotels (Interview #20).

Whenever I can, I stay with local people during my travels. This not only help to save money, but it also helps to minimise my environmental footprint whenever possible. Besides, staying with locals gives a more authentic experience (Interview #24).

As a tourist, I always try to eat and buy groceries at local markets and shops. Prices at these markets are always less than what you would pay at a restaurant. You also help the local economy directly by buying from local vendors (Interview #21).

With my classmates, we often prefer travelling to cheap destinations and small villages. Some tours are available that support travelling to remote destinations sustainably. We often travel with them and always share our experiences on social media to help them to attract new customers (Interview #3).

Theme 3: prosocial drivers

Analysis of interviews revealed that a buycott choice is also influenced by Gen Z's social commitments. Through their consumption decisions, Gen Z expresses their concern and sense of societal responsibility by purchasing from firms that they believe behave responsibly. This is consistent with the results of research indicating that the propensity to buycott is influenced by consumer motivation and prosocial drives that indicate social responsibility (Shaw et al., Citation2006; Hoffmann et al., Citation2018). Altruism, trust and the pursuit of social justice constitute a set of prosocial motivators for the participants of this research.

Altruism

Many members of Gen Z put a high value on taking responsibility for their own consumption and also feel obligated to alter the consumption patterns of others (Sharpley, Citation2021; Lin et al., Citation2022). From this perspective, not only many members of Gen Z are aware of the world’s environmental problems, but they also believe that inequality, poverty, unemployment, and the frugal economy are also critical issues that will become profoundly significant over their lifetimes and for which they are looking to business and government to respond. They are conscious that their actions may influence others, the environment, or the resource access of future generations (Dabija et al., Citation2020). Increasing evidence in tourism suggests that cohorts tend to be very worried about environmental issues (Sharpley, Citation2021; Prayag et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2022). Gen Z’ers are regarded to be self-aware in achieving environmental goals, as they search for environmental solutions (Robinson & Schänzel, Citation2019). Lin et al. (Citation2022) concluded that eudaimonic environmental motivations influence voluntary behaviours of Gen Z towards environmental sustainability. According to Salinero et al. (Citation2022) Gen Z travellers attribute a great deal of responsibility to themselves for preventing the deterioration of sustainability issues in destinations. In general, travellers who believe they are accountable for avoiding or reducing tourism-related sustainability issues will behave more sustainably than those who do not (Confente & Scarpi, Citation2021; Han et al., Citation2018). For Gen Z, buycotts are the means through which environmental or social concerns and aspirations are translated into collective actions.

We must care about the world we live in. We must care about our environment and do whatever we can to protect it. If we do nothing, it will lead to a catastrophic outcome. We’re all connected to one another and the planet (Interview #2).

I want to be part of the change. Through my posts on social media and blogs, I want to encourage and educate everyone and especially my peers to act ethically while travelling to sensitive areas. We must really care about our heritage. Heritage sites belong to everyone (Interview #6).

I have always supported those businesses that take social responsibility seriously and committed themselves to the community (Interview #16).

I am a member of a network that collects and donates money to local environmental projects for empowering villages in different parts of Iran. I believe we are all connected (Interview #23).

Thus, this study supported previous findings which argue that altruism significantly increases the likelihood of buycott engagement (Neilson, Citation2010). Significantly with respect to sustainable tourism and responses to global environmental change, surveys of the sustainable behaviour of the Gen Z cohort suggest that they have a strong sense of social responsibility and interest to enable sustainable development (e.g. the 2016 Masdar Gen Z global sustainability survey). Social concerns are positively associated with willingness to participate in buycotts to reward responsible companies. This echoes Copeland (Citation2014) that buycotting is congruent with engaged citizenship norms that highlight the significance of assisting others which also reflects Islamic values of charity in Iranian society (Siyavooshi et al., Citation2018). For Neilson (Citation2010), buycott is a simple everyday action than boycott since the information necessary for buycott decisions is more readily available and consumers are more likely to support a business that aligns with their beliefs. Thus, as the above findings also showed, social concerns foster consumer buycott decisions.

Trust

The data analysis also indicates that those members of Gen Z who buycott build trust towards the buycott targets. Buycotting fosters a greater degree of confidence in the social bonds formed with other parties. This corroborates Neilson’s (Citation2010) conclusion that buycotters have much more trust in others because they have trust in institutions. This enhances people’s confidence in the buycott targets, hence encouraging buycotting activity. This was also noted by the participants:

I really trust companies and businesses that sacrifice profit for ethical and moral conduct (Interview #26).

I trust and respect small businesses in tourism a lot… I believe that dining at small restaurants and purchasing things from local craftsmen are excellent ways to help the local community. They are the ones that have the most need for tourism revenue (Interview #25).

This also corroborates the findings of Neilston (2010) that trust and associated social capital support and inspire political consumption via access to knowledge and resources. This means that those who have trust in the facts about political consumerism are expected to be more inclined to participate in buycott activities, while generalised trust may cause political consumers to feel effective as a part of the communal endeavour as a result of their confidence that others will also buycott. According to Dalton (Citation2008), a crucial aspect of active citizenship is the significance of assisting others outside of established political conflict mechanisms which arguably reflects reward orientation of buycotting nature. By connecting norms and buycotting, the latter is therefore situated within broader political and civic behaviour (Copeland, Citation2014).

The pursuit of social justice

Another motive driving Gen Z to engage in buycotting is the pursuit of social justice. The respondents argue that their participation in a buycotting campaign was motivated by a desire for peace of mind and to avoid a sense of guilt for not supporting what is viewed as justice. These are noted by the study participants:

I care how people are treated. When I see or hear about the businesses that respect the workers’ rights, I have no doubt to spread the word and support (Interview #7)

My sister works for a travel agency that employed around 20 young people. The majority of whom are recent university graduates. She and her coworkers are treated fairly and paid decently. We always say good things about this travel agency and recommend it to others (Interview #12).

Conclusion and implications

Grounded in political and ethical consumerism literature and guided by lifestyle politics theory, the central objective of this study was to explore why Gen Z engages in tourism related buycotts. This provides insight on the underlying motivations and drivers leading to such practices. Gen Z has been viewed as the first generation to grow up with the Internet which therefore creates certain practices, behaviours and expectations with respect to how consumption, connectedness, and mobility are understood. Despite a great concern for sustainability displayed by Gen Z, empirical evidence exploring drivers underpinning their buycotting in the tourism realm is limited.

Different themes emerged from the study’s results to explain the motivations of Gen Z to participate in buycott-related actions. The research demonstrated that fulfilment, self-identity, and frugality are core individual drivers of buycotting for Gen Z tourism consumers. The study also found that Gen Z buycott behaviour is encouraged by prosocial drivers including altruism, trust, and the pursuit of social justice motivations. Furthermore, exposure to social media information, peer persuasion, and past experience were identified as the influencers of buycott participation. By exploring a variety of buycott motivators and influencers, the findings of this study provided significant new insights to advance the knowledge on this topic.

Theoretical implications

Findings from this research contribute to the field of tourism in several ways. First, as far as can be ascertained, this is the first empirical study that is grounded in seeking to understand the drivers underpinning buycotting in a tourism context. The present study, therefore, extends previous research on political tourism consumption which have only examined boycotts. Second, by focusing on Gen Z as the study’s key informants, we bridge a critical gap in the empirical literature on generational understanding of sustainable tourism. Most studies on tourist pro-environmental behaviours do not identify generational differences in travel behaviour. Thus, this study presents novel insights to the literature on the political and ethical consumption of this cohort and expanded the scope of sustainable tourism consumption research to take into account the buycotting behaviour of Gen Z which has not been previously researched.

Third, by applying the lens of lifestyle politics theory to buycotting engagement, the study extends earlier literature by providing a theoretically and empirically grounded generational understanding of buycotting decisions in travel and tourism. Fourth, despite the substantial research on political consumerism and responsible consumption in developed economies and democratic states, there is very limited research on developing countries, especially those with a theocratic constitution. This study therefore extends the broader literature by focusing on a developing and emerging economy and polity.

Practical implications

From a managerial perspective, this study has also several implications. First, the findings suggest that businesses should acknowledge the growing importance of political consumerism among tourists and more particularly the Gen Z cohort. Contemporary tourism consumers are aware of the influence of their purchasing choices and consumption practices. Significantly, Recent advances in communication technology enable the rapid dissemination of information; thus, it is crucial to comprehend how and why tourists respond to certain business practices (Liu et al., Citation2022). Second, the results of this research offer insights on the factors that lead to buycotts, allowing managers to be aware of the ethical and sustainability dimensions that motivate or discourage consumption of particular products. Ethical concerns and social obligations are important motivators for the contemporary tourism consumers especially the Gen Z cohort, as shown by the participant data. This is particularly important in the post-pandemic travel period, and how the broad environmental values of tourists and their usage of social media may convert into actual sustainable behaviour (Salinero et al., Citation2022). Understanding the extent to which Gen Z’s contemporary activism, including online campaigns, will be sustained over time and potentially be transferred to more active boycotts and buycotts should be considered by DMOs and industry practitioners. Managers need to be better attuned to buycott motivations and practices. As the findings showed, those with fulfilment values are more likely to buycott. Managers can effectively engage with buycott behaviour if they have a thorough understanding of their target market.

Third, the study’s findings have far-reaching consequences for businesses and policymakers seeking to alter business conduct via buycotting. Similarly, enterprises targeted by these sorts of coordinated consumer activities must account for the particular incentive processes that are founded in the unique characteristics of buycotts (i.e. rewarding). Finally, consumers may act on their favourable attitudes about CSR-minded purchasing behaviour, and these consumers are willing to reward ethical behaviour. In their commercial interactions, companies and brands must be morally, fiscally, legally, and philanthropically responsible and show their social responsibility in order to appeal to new generations of tourism consumers.

Limitation and directions for future research

Some of the limitations of this research provide several recommendations for further studies. Although the research offered substantial information on the factors that impact Gen Z's buycott behaviours, it was limited to a single cohort in a particular country (Iran). Future research could compare ethical consumption behaviours between generations as well as different cultures and countries, including comparative studies between countries with different economic and political conditions. Despite this study increases understanding of political consumerism by identifying the drivers of Gen Z’s buycott behaviour, future research could empirically corroborate these findings through quantitative or mixed methods. This would potentially provide more information into, for example, how individual and pro-social motivators inspire participation in buycotts. Future studies could also analyse the underlying social and cultural values of political consumers while also seeking to identify relationships between political consumption in tourism with other forms of political consumption as well as wider sets of political values and actions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of the paper and their thoughtful comments and constructive suggestions, which helped to improve the quality of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abramowitz, S. I., & Nassi, A. J. (1981). Keeping the faith: Psychosocial correlates of activism persistence into middle adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10(6), 507–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02087943

- Adugu, E. (2014). Boycott and buycott as emerging modes of civic engagement. International Journal of Civic Engagement and Social Change, 1(3), 43–58.

- Baek, Y. M. (2010). To buy or not to buy: Who are political consumers? What do they think and how do they participate? Political Studies, 58(5), 1065–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00832.x

- Bennett, W. L. (1998). The uncivic culture: Communication, identity, and the rise of lifestyle politics. PS: Political Science & Politics, 31(4), 741–761.

- Bennett, W. L. (2012). The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212451428

- Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2), 141–163.

- Bizaer, M. (2022). Iran’s rising Generation Z at the forefront of protests. The Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/irans-rising-generation-z-forefront-protests.

- Boström, M., Micheletti, M., & Oosterveer, P. (2019). The Oxford handbook of political consumerism. Oxford University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Brunk, K. H. (2010). Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.03.011

- Casalegno, C., Candelo, E., & Santoro, G. (2022). Exploring the antecedents of green and sustainable purchase behaviour: A comparison among different generations. Psychology & Marketing, 39(5), 1007–1021.

- Chatterjee, S., Sreen, N., & Sadarangani, P. (2021). An exploratory study identifying motives and barriers to ethical consumption for young Indian consumers. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 22(2–3), 127–148.

- Chen, Z., Ryan, C., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Transgenerational place attachment in a New Zealand seaside destination. Tourism Management, 82, 104196.

- Confente, I., & Scarpi, D. (2021). Achieving environmentally responsible behavior for tourists and residents: A norm activation theory perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 60(6), 1196–1212.

- Copeland, L. (2014). Conceptualizing political consumerism: How citizenship norms differentiate boycotting from buycotting. Political Studies, 62, 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12067

- Copeland, L., & Boulianne, S. (2022). Political consumerism: A meta-analysis. International Political Science Review, 43(1), 3–18. 0192512120905048. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120905048

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed). Sage Publications.

- Dabija, D. C., Bejan, B. M., & Pușcaș, C. (2020). A qualitative approach to the sustainable orientation of generation Z in retail: The case of Romania. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(7), 152.

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies, 56(1), 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

- De Moor, J. (2017). Lifestyle politics and the concept of political participation. Acta Politica, 52(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2015.27

- De Young, R. (1986). Encouraging environmentally appropriate behavior: The role of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Environmental Systems, 15(4), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.2190/3FWV-4WM0-R6MC-2URB

- De Zúñiga, H. G., Copeland, L., & Bimber, B. (2014). Political consumerism: Civic engagement and the social media connection. New Media & Society, 16(3), 488–506.

- Djafarova, E., & Foots, S. (2022). Exploring ethical consumption of generation Z: Theory of planned behaviour. Young Consumers. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2021-1405

- Endres, K., & Panagopoulos, C. (2017). Boycotts, buycotts, and political consumerism in America. Research & Politics, 4(4), 2053168017738632.

- European Travel Commission. (2020). Study on generation Z travellers. https://etc-corporate.org/uploads/2020/07/2020_ETC-Study-Generation-Z-Travellers.pdf.

- Faris, D.M., & Rahimi, B. (Eds.). (2015). Social media in Iran: Politics and society after 2009. SUNY Press.

- Flick, U. (2018). Designing qualitative research. Sage.

- Francis, T., & Hoefel, F. (2018). True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies.

- Friedman, M. (1996). A positive approach to organized consumer action: The “buycott” as an alternative to the boycott. Journal of Consumer Policy, 19(4), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00411502

- Gardiner, S., Grace, D., & King, C. (2015). Is the Australian domestic holiday a thing of the past? Understanding baby boomer, Generation X and Generation Y perceptions and attitude to domestic and international holidays. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21(4), 336–350.

- Giachino, C., Bollani, L., Truant, E., & Bonadonna, A. (2022). Urban area and nature-based solution: Is this an attractive solution for Generation Z? Land Use Policy, 112, 105828.

- Given, L.M. (Ed.). (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage.

- Gregson, N., & Ferdous, R. (2015). Making space for ethical consumption in the South. Geoforum, 67, 244–255.

- Haddouche, H., & Salomone, C. (2018). Generation Z and the tourist experience: Tourist stories and use of social networks. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 69–79.

- Haenfler, R., Johnson, B., & Jones, E. (2012). Lifestyle movements: Exploring the intersection of lifestyle and social movements. Social Movement Studies, 11(1), 1–20.

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Hall, M. C. (Ed.). (2010). Fieldwork in tourism: Methods, issues and reflections. Routledge.

- Han, H., Yu, J., Kim, H. C., & Kim, W. (2018). Impact of social/personal norms and willingness to sacrifice on young vacationers’ pro-environmental intentions for waste reduction and recycling. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(12), 2117–2133.

- Han, W., Wang, Y., & Scott, M. (2021). Social media activation of pro-environmental personal norms: An exploration of informational, normative and emotional linkages to personal norm activation. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(6), 568–581.

- Hanna, P. (2012). Using internet technologies (such as Skype) as a research medium: A research note. Qualitative Research, 12(2), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111426607

- Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative research methods. Sage.

- Hoffmann, S., & Hutter, K. (2012). Carrotmob as a new form of ethical consumption. The nature of the concept and avenues for future research. Journal of Consumer Policy, 35(2), 215–236.

- Hoffmann, S., Balderjahn, I., Seegebarth, B., Mai, R., & Peyer, M. (2018). Under which conditions are consumers ready to boycott or buycott? The roles of hedonism and simplicity. Ecological Economics, 147, 167–178.

- Jiang, Y., & Hong, F. (2021). Examining the relationship between customer-perceived value of night-time tourism and destination attachment among Generation Z tourists in China. Tourism Recreation Research,. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1915621

- Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi‐structured interview guide.Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

- Kelm, O., & Dohle, M. (2018). Information, communication and political consumerism: How (online) information and (online) communication influence boycotts and buycotts. New Media & Society, 20(4), 1523–1542.

- Klein, J. G., Smith, N. C., & John, A. (2004). Why we boycott: Consumer motivations for boycott participation. Journal of Marketing, 68(3), 92–109.

- Kwun, D. J. W., & Oh, H. (2007). Past experience and self-image in fine dining intentions. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 9(4), 3–23.

- Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A. E., & Liao, T. F. (2004). Semistructured interview. In M. Lewis-Beck, A. E. Bryman, & T. F. Liao, T.F. (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods (pp. 1021–1021). Sage.

- Lin, Z., Wong, I. A., Wu, S., Lian, Q. L., & Lin, S. K. (2022). Environmentalists’ citizenship behavior: Gen Zers’ eudaimonic environmental goal attainment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2108042

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Liu, J., Wang, C., Zhang, T., & Qiao, H. (2022). Delineating the effects of social media marketing activities on Generation Z travel behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 00472875221106394.

- Malone, S., McCabe, S., & Smith, A. P. (2014). The role of hedonism in ethical tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 241–254.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2009). Designing a qualitative study. In L. Bickman, & D. J. Rog (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of applied social research methods (pp. 214–253). Sage.

- Micheletti, M. (2003). Political virtue and shopping. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Micheletti, M., & Stolle, D. (2012). Vegetarianism—A lifestyle politics?. In M. Micheletti & A.S. McFarland (Eds.), Creative participation responsibility-taking in the political world (pp. 125–145). Routledge.

- Neilson, L. A. (2010). Boycott or buycott? Understanding political consumerism. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(3), 214–227.

- Neilson, L. A., & Paxton, P. (2010). Social capital and political consumerism: A multilevel analysis. Social Problems, 57(1), 5–24.

- Neilson, L. A. (2010). Boycott or buycott? Understanding political consumerism. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(3), 214–227.

- Newman, B. J., & Bartels, B. L. (2011). Politics at the checkout line: Explaining political consumerism in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 64(4), 803–817.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847.

- Parzonko, A. J., Balińska, A., & Sieczko, A. (2021). Pro-environmental behaviors of generation Z in the context of the concept of Homo Socio-Oeconomicus. Energies, 14(6), 1597.

- Prayag, G., Aquino, R. S., Hall, C. M., Chen, N., & Fieger, P. (2022). Is Gen Z really that different? Environmental attitudes, travel behaviours and sustainability practices of international tourists to Canterbury, New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2131795

- Qiu, H., Wang, X., Morrison, A. M., Kelly, C., & Wei, W. (2022). From ownership to responsibility: Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourist environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2116643

- Robichaud, Z., & Yu, H. (2021). Do young consumers care about ethical consumption? Modelling Gen Z's purchase intention towards fair trade coffee. British Food Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2021-0536

- Robinson, V. M., & Schänzel, H. A. (2019). A tourism inflex: Generation Z travel experiences. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(2), 127–141.

- Sakdiyakorn, M., Golubovskaya, M., & Solnet, D. (2021). Understanding Generation Z through collective consciousness: Impacts for hospitality work and employment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102822.

- Salehi, S., Telešienė, A., & Pazokinejad, Z. (2021). Socio-cultural determinants and the moderating effect of gender in adopting sustainable consumption behavior among university students in Iran and Japan. Sustainability, 13(16), 8955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168955

- Salinero, Y., Prayag, G., Gómez-Rico, M., & Molina-Collado, A. (2022). Generation Z and pro-sustainable tourism behaviors: Internal and external drivers. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2134400

- Schaefer, A., & Crane, A. (2005). Addressing sustainability and consumption. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(1), 76–92.

- Seyfi, S., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Tourism, sanctions and boycotts. Routledge.

- Seyfi, S., & Hall, C.M. (Eds.). (2018). Tourism in Iran: Challenges, development and issues. Routledge.

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., Saarinen, J., & Vo-Thanh, T. (2021). Understanding drivers and barriers affecting tourists’ engagement in digitally mediated pro-sustainability boycotts. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.2013489

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., Vo-Thanh, T., & Zaman, M. (2022). How does digital media engagement influence sustainability-driven political consumerism among Gen Z tourists? Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2112588

- Shah, D. V., McLeod, D. M., Kim, E., Lee, S. Y., Gotlieb, M. R., Ho, S. S., & Breivik, H. (2007). Political consumerism: How communication and consumption orientations drive “lifestyle politics”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 611(1), 217–235.

- Shaheer, I., Carr, N., & Insch, A. (2019). What are the reasons behind tourism boycotts? Anatolia, 30(2), 294–296.

- Shaheer, I., Carr, N., & Insch, A. (2021). Rallying support for animal welfare on Twitter: A tale of four destination boycotts. Tourism Recreation Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1936411

- Shaheer, I., Carr, N., & Insch, A. (2022). Spatial distribution of participation in boycott calls: A study of tourism destination boycotts associated with animal abuse. Anatolia, 33(3), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2021.1931896

- Sharpley, R. (2021). On the need for sustainable tourism consumption. Tourist Studies, 21(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797620986087

- Shaw, D., Newholm, T., & Dickinson, R. (2006). Consumption as voting: An exploration of consumer empowerment. European Journal of Marketing, 40(9/10), 1049–1067.

- Shepherd, J. (2021). ‘I’m not your toy’: Rejecting a tourism boycott. Tourism Recreation Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1998874

- Siyavooshi, M., Foroozanfar, A., & Sharifi, Y. (2018). Effect of Islamic values on green purchasing behavior. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(1), 125–137.

- Sobhe Sadegh. (2021). Generation Z and the future of Iran. http://ssweekly.ir.

- Soper, K. (2008). Alternative hedonism, cultural theory and the role of aesthetic revisioning. Cultural Studies, 22(5), 567–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380802245829

- Stavrianea, A., & Kamenidou, I. (2022). Complying with digital transformation in online booking through experiential values of generation Z. European Journal of Tourism Research, 30, 3003–3003.

- Stolle, D., & Micheletti, M. (2013). Political consumerism: Global responsibility in action. Cambridge University Press.

- Stolle, D., Hooghe, M., & Micheletti, M. (2005). Politics in the supermarket: Political consumerism as a form of political participation. International Political Science Review, 26(3), 245–269.

- Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (2009). The fourth turning: What the cycles of history tell us about America’s next rendezvous with destiny. Broadway Books.

- Suárez, E., Hernández, B., Gil-Giménez, D., & Corral-Verdugo, V. (2020). Determinants of frugal behavior: The influences of consciousness for sustainable consumption, materialism, and the consideration of future consequences.Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 567752. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567752

- Sudbury Riley, L., Kohlbacher, F., & Hofmeister, A. (2012). A cross-cultural analysis of pro-environmental consumer behaviour among seniors. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(3–4), 290–312.

- Tomhave, A., & Vopat, M. (2018). The business of boycotting: Having your chicken and eating it too. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(1), 123–132.

- Van Deth, J. W. (2016). What is political participation. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, 49(3), 349–367.

- Wahlen, S., & Laamanen, M. (2015). Consumption, lifestyle and social movements. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(5), 397–403.

- Walsh, G., Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., Andrews, J. C., & Hastings, G. (2010). Segmentation in social marketing: Insights from the European Union’s multi‐country, antismoking campaign. European Journal of Marketing, 44(7/8), 1140–1164.

- Wee, D. (2019). Generation Z talking: Transformative experience in educational travel. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2019-0019

- Weeden, C., & Boluk, K. (2014). Introduction: Managing ethical consumption in tourism–compromises and tensions. In C. Weeden, & K. Boluk (Eds.), Managing ethical consumption in tourism (pp. 21–36). Routledge.

- Yu, Q., McManus, R., Yen, D. A., & Li, X. R. (2020). Tourism boycotts and animosity: A study of seven events. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102792.