Abstract

Globally, the tourism industry has been devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated changes in international travel. This paper draws on interviews with 51 women working in the tourism sector in Tanzania and examines gendered impacts of the pandemic on their welfare, which instigated or accelerated entrepreneurial activities as an attempt to protect women’s incomes and security. Women in the study adopted one of three entrepreneurial strategies: they (re)committed to the tourism industry, working on developing their own skills and business ideas; they diversified their business interests to have a ‘Plan B’ in addition to tourism to safeguard against future crises; or they moved away from tourism altogether, focusing instead on other less volatile sectors. The crisis caused by the pandemic exposed tourism as a risky business and a gamble for many women, who are considering leaving the sector. This represents a significant obstacle for the tourism industry’s recovery and sustainability and illustrates some of the limitations of tourism entrepreneurship for supporting and empowering women in the Global South. Priority policy areas for supporting women to remain within tourism are identified to help support women entrepreneurs and ensure their skills and enthusiasm contribute to rebuilding and reshaping the sector.

Introduction

In 2019 international visitation to Tanzania was around 1.6 million tourists who brought to the country US$2.5 billion and contributed more than 17% of GDP, around 30% of foreign earnings and 10% of formal employment (Anderson et al., Citation2021; Suluo et. al, Citation2021). However, in the fourth quarter of 2020, earnings from tourism dropped by nearly 75 percent in comparison to quarter four in 2019, as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (Statista, Citation2021). The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating effect on the tourism industry, both worldwide and nationally, with a 93% decline in international visitors in April, May and June 2020, leading to closure and uncertainty among tourism businesses in Tanzania (Ministry of Natural Resources & Tourism, Citation2020). Many impacts of the pandemic globally are gendered, with women more likely to lose jobs, experience reduced incomes and take on additional unpaid caring responsibilities than men (Bahn et al., Citation2020; Collins et al., Citation2021). Tourism work is already gendered, with women overrepresented in casual, insecure and sometimes informal roles (Je et al., Citation2022). The impacts of the pandemic on tourism work are thus likely to be gendered as well, with women more vulnerable to losing their incomes and with heavy responsibility to care for others through the on-going global health crisis. This paper examines the impacts of the first 1.5 years of the pandemic on women working in the tourism sector in Tanzania and their entrepreneurial responses to the extreme crisis they faced as a result of the almost total shutdown of international tourism that severely limited their ability to earn money to support themselves and their families.

Tourism offers important employment and entrepreneurship opportunities for many women; however, entrepreneurship is gendered, like most other aspects of work (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2022). In many regions, particularly in parts of the Global South, women’s work and entrepreneurship opportunities may be further limited by a variety of factors including lack of formal education, cultural and religious norms, and the expectations of caring for family and the wider community (Phommavong & Sörensson, Citation2014). Tourism may offer opportunities for women to overcome some of these restrictions, though many barriers are persistent (Tucker, Citation2022). Tourism work can provide economic support for many women in a variety of roles, ranging from large to small tourist organisations (such as hotels and tour companies) to the making and selling of food products and handicrafts (Maliva & Mwaipopo, Citation2017). Women entrepreneurs in tourism challenge, negotiate and sometimes transform their environments. Maliva (Citation2017) identified three types of women entrepreneurs in Tanzania; producers, retailers and distributors, indicative of the range of roles women take on, as well as their important contribution to tourism development in the country. In turn, this means that many women entrepreneurs in a variety of roles were vulnerable to the shock that the pandemic has had on the tourism sector and its dependent services and industries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has sent shockwaves through the tourism industry. In this paper we draw on interviews with women working in the tourism sector in Tanzania to illustrate how this crisis has had gendered effects, detailing impacts that have not yet been acknowledged, let alone addressed, by policy makers and employers. As we demonstrate, the pandemic has both reinforced and intensified entrepreneurship activities, borne out of necessity and fear of an uncertain future. The UNWTO (Citation2021) estimates that countries in the Global South heavily dependent on international tourism, like Tanzania, will be the worst hit and slowest to recover from the pandemic. It is thus important to focus on the gendered aspects of the pandemic and efforts towards recovery in such regions in order to understand if and how this crisis may either worsen or improve existing gender inequalities in tourism entrepreneurship in the Global South. The tourism sector remains organised under regulative, normative, and cognitive institutions that in turn influence women entrepreneurs’ access to cultural, social, and economic capital (Lugalla, Citation2018).

Dushnitsky et al. (Citation2020) argue that entrepreneurs may be particularly vulnerable to crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic, as associated conditions of high uncertainty and resource scarcity significantly increase chances of failure. However, they note that “every crisis also carries the seeds of renewal” (p.537), creating opportunities that entrepreneurs may be well-placed to capitalise upon. This tension - between extreme precarity and the opening up of new opportunities - provides an interesting context in which to explore women’s entrepreneurship, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa where resources were already highly constrained even before this unprecedented crisis struck (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). The responses of women entrepreneurs in Tanzania in our study were varied; they were highly exposed to the economic vulnerability brought about by the pandemic, and many suffered extreme hardship as a result. However, the necessity to try to mitigate the consequences of this hardship meant that crisis also stimulated action and required the pursuit of new opportunities, both within and beyond the tourism industry. We define entrepreneurial action as “any activity entrepreneurs might take to form and exploit opportunities” (Alvarez & Barney, Citation2007:12), which for the women in our study was borne out of both necessity and a desire to capitalise on opportunity and mitigate against future disasters.

We begin by introducing our theoretical positioning which recognises entrepreneurship as socially embedded and contextual. Welter et al. (Citation2019) argue that entrepreneurship needs to be contextualised, be that in relation to who (the ideal entrepreneur is implicitly assumed to be male), where (most research concentrates on industrialised countries), how (the focus has been mainly on technological innovations) and why (the primary motive is assumed to be to generate wealth). The women entrepreneurs in our study differ from these norms on all levels. After presenting the methods of the study, we draw on the accounts of 51 women working in the tourism sector to identify gendered impacts of the pandemic on those women and their entrepreneurial responses to the crisis this pandemic caused. We outline three entrepreneurial strategies adopted by the women in this study and argue that one—moving away from tourism completely—represents a risk to the sustainability of the tourism industry. We identify some areas for policy interventions and action to support women to remain within and contribute to the recovery of the risky business that is tourism.

Women’s entrepreneurship in tourism in the Global South

Entrepreneurs operate in a complex tourism sector that is driven, owned, and influenced by governments, the private sector, and large international companies with consequences for both the formal and informal sectors, which are shaped by laws, regulations, rules, and government policies that promote or restrict creation of new businesses, reduce or increase the risk for an entrepreneur, and facilitate or restrict access to resources (Busenitz et al., Citation2000).

The private sector, which constitutes most entrepreneurs, is a key player and is in fact recognised as the engine for tourism growth in many countries. Tourism promotes entrepreneurship and SME (small and medium-sized enterprises) growth in tourist-generating and -receiving countries. Tanzania is not unique, with several private sector organisations (PSOs) involved in tourism business (Anderson et al., Citation2017), including gender focused ones such as Association of Women in Tourism in Tanzania and Tanzania Women Chamber of Commerce. The PSOs serve as a strong tool for engagement in partnerships and dialogue with the government on behalf of tourism service providers.

In many countries in the Global South, women entrepreneurs play a significant role in contributing to the nation’s economy and yet represent the poorest of the poor (Mordi et al., Citation2010). Compared to their male counterparts, the tourism sector employs a high proportion of female workers and their concentration is much felt in lower-skilled and lower-paid jobs (Anderson, Citation2015). Moreover, as Stevenson and St-Onge (Citation2005) indicate, women entrepreneurs typically engage in business as a way of creating employment for themselves for meeting household needs, supplementing income, security, autonomy, and enjoyment in the work they do. Tourism can provide various entry points for women’s social and economic development and offers opportunities for creating self-employment in small and medium sized income generating activities (Ateljevic, Citation2009; Thien, Citation2009).

However, there are multiple cultural and religious norms, values, and societal views influencing participation of women in the public space and workforce (UNWTO, Citation2022). Conceptualisations of entrepreneurship are usually based on implicit assumptions that all women entrepreneurs have equal access to resources, participation and support, whereas evidence illustrates that variance in regional culture, economic context and social norms affect women’s motivations, experiences and growth aspirations (Elam et al., Citation2019). Our theoretical position recognises that entrepreneurship is a socially embedded process that occurs differently in diverse contexts (Welter et al., Citation2019). Social, cultural, economic and religious factors influence how entrepreneurship is perceived, practised, experienced and valued, related to “different normative perceptions of who should be an entrepreneur and how they should ‘do’ or enact entrepreneurship” (Ojediran & Anderson, Citation2020: 1).

Rindova et al. (Citation2009) argue that entrepreneurial activity can be a means of emancipation through which groups and individuals break free from constraints within their economic, social and cultural environments. This focus on change, as opposed to just wealth creation, is an important disjuncture from mainstream entrepreneurship theorisation and indicates ways in which tourism may provide avenues for transforming the lives of women in the Global South. However, as Jennings et al. (Citation2016) argue, in practice it is unlikely that women’s entrepreneurship will lead to such transformation within neoliberal societies and this is exacerbated within patriarchal societies like Tanzania.

Entrepreneurship is valorised as a near universal ‘solution’ to women’s economic, social and political marginalisation, and tourism entrepreneurship is often positioned as uniquely beneficial for women in the Global South. However, as Trupp and Sunanta (Citation2017) argue based on their research in Thailand, although tourism does offer women work and entrepreneurship opportunities that can provide some income and economic empowerment, this may not always lead to women becoming less marginalised in communities and public life, due to wider social, cultural and religious norms. Duffy et al. (Citation2015) make similar observations in relation to the limitations of tourism work for women’s wider empowerment in families and communities in the Dominican Republic. Therefore, women’s entrepreneurship in tourism must be considered in context and in relation to local and regional social, cultural and religious norms.

In many countries in Africa, today strong patriarchal systems dominate, which are further shaped by religious beliefs, nominating men and especially husbands as the main decision makers, and thus affecting women entrepreneurs (Lugalla, Citation2018; Anderson & Mdemu Komba, Citation2017). In contrast, women are usually responsible for caregiving and family maintenance. As Creighton and Omari (Citation2018) argue, changing gender relations, coupled with economic pressures on Tanzanian men, are transforming traditional gender roles with more women shouldering greater financial responsibility for families as well. This has impacts for women’s entrepreneurial motivations, intentions and experiences. Furthermore, ILO (Citation2003) report that gender issues and power relations that challenge women entrepreneurs include “women being subjected to pressure to offer sexual favors to corrupt government officials; lack of confidence in women by bank officers; discouragement from men when starting or formalizing businesses; and inadequate management for covering during maternity leave” (Lugalla, Citation2018: 32). Women entrepreneurs in tourism in Tanzania thus face multiple barriers to success, even prior to the shock of the pandemic.

The implications for future developments in the tourism sector in the context of the pandemic are clear: both the public and private sector can contribute to the on-going response and recovery with a special emphasis on the role women can play in the key sector of tourism (World Bank, Citation2021); however, the gendered and localised nature of entrepreneurship in tourism needs specific policies and actions. In order to develop contextualised strategies and actions, it is first necessary to understand the experiences of women entrepreneurs in the Tanzanian tourism industry.

Gendered impacts of the pandemic and strategies to support women entrepreneurs in tourism

In this paper we position entrepreneurship as contextual and socially embedded in both local and global processes (Welter et al., Citation2019; Ojediran & Anderson, Citation2020). The potential for tourism entrepreneurship to contribute to emancipation and empowerment for women in Tanzania is thus shaped by local practices and policies, as well as global factors like the shutdown of international tourism in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Tanzanian government did implement some measures to try and support businesses during the pandemic, including the tourism sector. This ranged from reducing licence fee rates to waiving some national park fees. However, most businesses in the private sector relied heavily on loans from commercial banks for survival, increasing financial risk for many. The government’s draft Recovery and Sustainability Plan for the Tourism Sector 2020/21-2024/25 did not identify gender as an important consideration, and there was no comment on the gendered impacts of the pandemic or specific strategies to support women entrepreneurs in particular. This focus limits understanding of the gendered nature of the pandemic and its impacts on tourism, impacts which we identify in our interview data. Without attention to gendered impacts of the pandemic, or the gendered aspects of tourism entrepreneurship, inclusive tourism development during and post COVID-19, with a focus on social issues and an equitable distribution of economic benefits through sustainable use of environmental resources, is unlikely.

Even international organisations like the UNWTO did not initially acknowledge the gendered aspects of the pandemic nor centralise gender in early recovery strategies. The UNWTO has since produced an Inclusive Recovery Guide with a focus on ‘Women in Tourism’, which contains a number of general recommendations for embedding gender perspectives in recovery plans (UNWTO, Citation2021). If and how this will be operationalised at national and local levels remains to be seen. The widespread failure to embed gender perspectives in tourism policy and practice—a problem that existed long before the COVID-19 pandemic (Ferguson & Alarcón, Citation2015)—continues to limit the potential for tourism to contribute to more equitable and sustainable futures, as championed in the Sustainable Development Goals since 1992.

Crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have far-reaching consequences. As Dushnitsky et al. (Citation2020) note, such crises expose entrepreneurs as vulnerable to failure due to increased insecurity and scarcity of resources, but also provide opportunity for innovation and development. This uncertainty affected entrepreneurs around the world, leading to varied entrepreneurial responses as a result of numerous factors, such as government support (or lack of), planning and collaboration, and ability to respond to and capitalise on opportunities (Giones et al., Citation2020). Kuckertz and Brändle (Citation2022) review of early empirical research on the pandemic and entrepreneurship showed that the level of uncertainty entrepreneurs faced as a result of this crisis was unprecedented, requiring resilience in order to not only survive but also embrace opportunities that arise. Zhang et al. (Citation2022) found that entrepreneurial responses to the COVID-19 pandemic amongst B&B enterprises in China were varied, influenced by access to different forms of capital and the shifting nature of uncertainty. Kuckertz et al. (Citation2020) argue that entrepreneurs in Germany faced considerable adversity with the onset of the pandemic, risking loss of growth, innovation and survival, adopting a bricolage approach (including capital accumulation, network support, partner goodwill and political support) to turn adversity into resilience. The findings of these studies inform our analysis, however we conceptualise entrepreneurship as contextual and socially embedded (Welter et al., Citation2019), consequently we also recognise the different circumstances the women entrepreneurs in our study faced, as women in precarious financial positions in a patriarchal society that did little to financially support its citizens, businesses or entrepreneurs through the unprecedented shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. The women in our study were already operating in a resource-scarce context prior to the pandemic that limited support to develop entrepreneurship activities (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). When the pandemic struck, resources became even more scarce, prompting entrepreneurial action to not only save their businesses but also their families and wider communities.

Research context and methods

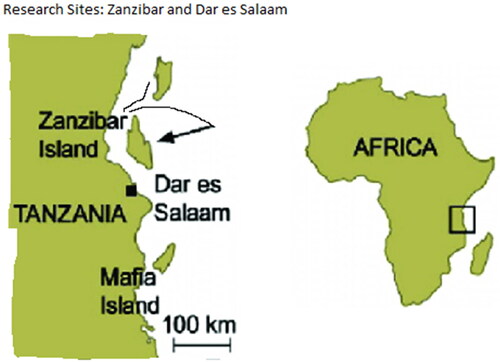

Our theoretical position recognises that entrepreneurship is a social process that needs to be contextualised. In this paper we draw on interviews with female entrepreneurs from two different tourism regions of Tanzania: the cosmopolitan city and commercial capital, Dar es Salaam, and the Muslim majority island of Zanzibar, as illustrated in (Anderson, Citation2013). It is estimated that 61% of international tourists to Tanzania use their international airports and the two sites combined host more than 1,000 kilometres of beaches. This positions them among the very important tourist destinations in East Africa. It is due to their importance as tourism sites, and therefore as locations for women’s entrepreneurship in tourism, that they were selected for this study.

Women were accountable for around 52% of the total population of 1.3 million (from 2012 census) in Zanzibar. On average, 22.8% of households in Zanzibar are headed by women (The Office of the Chief Government Statistician, Citation2019); and of these women, 44% have no education. Only 25% of women own land (The Office of the Chief Government Statistician, Citation2016), and the majority of them are the producers of food and cash crops. Regarding the other research site, Dar es Salaam, the latest census (in 2012), indicated that 51.2% of the total population of 4.4 million are women. Most of the residents in this city are employed in industrial or commercial activities. On top of the COVID-19 pandemic, the inadequate resources of production such as land, modern agricultural equipment and tools, loans, technology, education and extension service training, limit the success and personal development of most women at these two research sites.

In this study we adopted a qualitative research approach with semi-structured and open-ended interviews allowing probes when needed; for example, through reflecting the answer back to the interviewee or asking them to explain statements further (Charmaz, Citation2002; Gillham, Citation2000). We note that methodology is culturally bound and, in line with critical feminist theory, recognise the complexities of power and representation inherent in all research projects. Guided by a critical feminist research ethic (see Ackerly & True, Citation2008), our intention in this study was to give voice to the experiences of women working in tourism during the pandemic, voices which are not often heard in public discourse. The interviews were conducted by the first author, a Tanzanian woman, due to her local knowledge and expertise, as well as her fluency in English and Swahili, which allowed a wider range of interviewees to participate. Her shared identity as a Tanzanian woman was important in establishing trust from respondents and in recognising many of the shared contextual issues that shape these women’s experiences of entrepreneurship. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Dar es Salaam.

The interview questions collected basic demographic information - age, sex, ethnicity, religion, children, marital status, current caring responsibilities (including older relatives - none, responsibility for 1-3 others, 4-6 others, 6-10 others) - as well as the time involved within the tourism sector (less than a year, 1–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–15 years, 16–20 years, 20–25 years, 25+ years), the nature of the involvement, relevant qualifications, work characteristics (casual/permanent, part time, full time, etc.) and entrepreneurial activities, as well as the gendered aspects of their working experiences. Furthermore, questions about the nature and extent of the influence of the pandemic were asked and extended to inquire about long term goals and hopes, especially in regard to working in tourism.

In total, the first author conducted interviews with 51 women aged 21–65. All interviewees were working in the tourism sector prior to the pandemic, in mostly SMEs ranging from shop or hotel employees, to tour guides, vendors and artists. Of these, 13 had formal qualifications and most had extensive practical experience. Participants were classified into three areas of work, based on their position pre-pandemic, and following Maliva’s (Citation2017) classification of women entrepreneurs in Tanzania: employed (retailers - working for someone else in a tourism business such as a hotel, restaurant or shop), vendor (producers - working for themselves, selling direct to customers) or travel and tour operator (distributors - working for themselves or an employer in a tour company). Participants were recruited through the researchers’ professional networks, through relevant associations such as AWOTTA (Association for Women in Tourism Tanzania) and Tanzania Society of Travel Agents, and through attending local enterprises and asking workers if they would be willing to participate.

In this study we adopted an interpretative constructivist view that people intersubjectively construct their social realities, focusing on the meanings that participants give to their experiences (Lincoln et al., Citation2018). All interviews were recorded and transcribed as soon as possible (and translated into English if necessary) and then analysed through thematic coding. Each researcher read the interview transcripts independently, identifying broad open codes related to (a) gendered experiences of the pandemic; (b) effects of the pandemic on tourism work and entrepreneurship, and (c) entrepreneurial responses to the crisis. The team discussed the open codes and their relation to our theoretical position as outlined above. We followed a process of iterative analysis that “alternates between emic, or emergent, meanings of the data and an etic use of existing models, explanations and theories” (Tracy, Citation2013: 184). In this way, we identified shared entrepreneurial responses to the pandemic which we then grouped as three separate but related strategies. illustrates an example of the coding process adopted.

Table 1. The coding process.

McAllum et al. (Citation2019) argue that choice of analytic method affects the ‘data story’ that is presented. Adopting a thematic analysis approach enabled us to identify codes that transcended multiple interview transcripts and thus led to the development of themes (see ). Transforming categories into themes requires creating one or two sentences that encapsulate the ‘scope and content’ of the category (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006: 92), that then form the basis for the findings reported in the next section.

Table 2. Defining themes.

Research findings

The COVID-19 pandemic has had widespread impacts for women working in the tourism industry in Tanzania, who have responded in a variety of entrepreneurial ways to protect their incomes, themselves, their families and communities. We begin by briefly considering some of the impacts of the pandemic on women entrepreneurs that shape their experiences and relationships with the tourism industry. This provides important context for understanding the entrepreneurial actions and motivations of these women, as entrepreneurship is understood here as socially embedded action (Welter et al., Citation2019). The women in our study suffered extreme difficulties in the early stages of the pandemic and were forced to act to protect themselves and their families. We then identify three different strategies adopted in response to this unprecedented crisis, each of which pose challenges for the tourism industry as it rebuilds.

Impacts of the pandemic

Dushnitsky et al. (Citation2020) argue that extreme crises, like the pandemic, pose significant challenges for entrepreneurs due to drastic and sudden reduction in resources. All of our participants confirmed the devastating effects that the pandemic has had on tourism in Tanzania. The severe reduction in international tourist arrivals led many businesses to close down and/or shed staff, and severely impeded opportunities for vendors to sell their products of local crafts and foods:

It [COVID-19] has had a large effect, especially on the tourism industry. Business was very difficult for those that depend entirely on tourism… There were no tourists, our business depends on the presence of tourists and they were not available at the time. We used to come here but there was no work, we just came to guard the place. (Employee 93, significant care responsibilities for 4-6, and 6-10 years in tourism, Zanzibar)

We were hit hard, there was no business at all since borders were closed and we just had to shut down business for a while. We closed for about 6 months. There was no business, our lives and families were affected. We did not have money to pay school fees for the children. We depend on this business, we depend on tourists to come in and buy our products, and since the borders were closed we did not have anyone to sell to. (Vendor 14, care responsibilities for 1-3, and 1-5 years in tourism, Dar es Salaam)

Challenges occur because there is no work but the children still have to be taken to school, or when they fall sick, it is quite a headache. Just recently I had to pay a lot of money for school fees which I had to borrow around. (Employee 87, care responsibilities for 1-3, and 11-15 years in tourism, Zanzibar).

It has quite affected our plans. Whatever plans we had set for the year we have had to wait and we have had difficulties paying for the loans we had taken out. It did not come with any warning so that we could prepare for it, it was just sudden. The little savings that were kept had to be spent, so Corona has quite given us a setback. (Vendor 12, care responsibilities for 1-3, and 1-5 years in tourism, Zanzibar)

Both my parents are retirees and we cannot depend only on their retirement benefits. So before COVID-19 I was the sole provider for the family, so when COVID came in I could not provide the same amount I used to before. (Vendor 25, care responsibilities for 1-3, and 6-10 years in tourism, Dar es Salaam)

When COVID emerged in 2020, we lost a large portion of our customers, especially the international customers. We had to change our whole system and started to conduct trips for locals, especially institutions like banks, government institutions and schools. We have operated that way until 2021 and we still do not have international customers because they are restricted by COVID… So, to a great extent, our business has been shaken. (Tour company employee 25, care responsibilities for 1-3, and unknown years in tourism, Dar es Salaam)

Entrepreneurial responses

All women in our study were affected by the consequences of the pandemic on their incomes, their families and their day-to-day-lives. As they received no or very little support from the government, they were reliant on their own abilities to diversify and source alternative income. In this time of crisis, the entrepreneurial resilience of the women in our study was striking, and almost all participants expressed plans to either change activities or increase what they were already doing. In contrast to the entrepreneurship literature focused on Global North contexts that stresses entrepreneurship as an activity focused on wealth accumulation and often technological innovation (Schumpeter, Citation2000; Galloway et al., Citation2015), the women in our study accelerated their entrepreneurship plans through necessity and to try to protect themselves and their families from future crises. Furthermore, this entrepreneurial spirit was not something new to most of the women in our study, many of whom were already engaged in multiple forms of income generation, or had plans to do so, before the pandemic hit and forced them to accelerate those plans or risk financial ruin and even starvation in some cases.

In the face of great uncertainty about the future, and if and how tourism will recover in Tanzania post-pandemic, women in our study were adopting one of three entrepreneurial strategies: sticking with tourism; diversifying around tourism; or moving away from tourism altogether. Each of these strategies pose challenges for the tourism industry to address in efforts to rebuild and develop, as we discuss further in the following section.

Strategy one: Sticking with tourism

Tourism was one of Tanzania’s main employers and an important source of income generation pre-pandemic (World Bank, Citation2021), and some participants were confident that this situation would return and tourism would once again provide a reliable source of income. As Employee 86 (with no care responsibilities, and 1-5 years in tourism, Dar es Salaam) explained:

I have not thought about leaving the tourism sector. I know that this situation is just temporary and soon everything will get back to normal. It is an ongoing activity; it is not something that can just die like that. In every generation there will be people who would love to come and see how we live. I believe that it is something that will last for a long time so I have not thought about leaving tourism for another career.

I will keep on working in tourism but it will be on an international scale. I will expand horizons beyond just Tanzania, and even go out to bring people from afar to Tanzania.

It [COVID-19] affected me a lot. I was affected 100%. It is a job that I depended on completely and I was looking forward to growing my career … I had a lot of plans while working there [the hotel] on growing my career and the hotel management even had plans to take us abroad to other branches of the hotel. But when COVID emerged, they had to close all their branches in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Turkey etc. and we kept on getting paid until our contracts expired, and then we remained without any salary.

My plan is to go back to work and to grow my career, but I also have plans for starting a business. In fact I have known that plan even before I started working. I have a plan to have my own restaurant, but first I have to gain experience from working at the hotels.

We have thought of going for local tourism, arranging trips for the locals, which is also a challenge. We had a trip in December to Serengeti and Butiama which we had advertised and it was very cheap and there was a good turn out, but when we got there everyone decided what to do on their own and it was not what we had initially planned. Local tourism is still quite a challenge because Tanzanians still do not have the tourism mindset; we only travel to visit relatives and we do not have the mindset of having savings for travelling for tourism purposes. It will take time to impose that idea in us to an extent that we can get business out of it.

We still have hope because this [tourism] is an important sector that cannot just go completely extinct. It has been shaken quite a lot but we believe it will stabilise and we do not want to lose our focus by engaging in other activities that we are not very proficient in. I have 12 years’ experience in this sector so I know exactly how to handle this business. So trying to venture into other businesses that I am not so sure about will just lead to financial losses.

Strategy two: Diversifying around tourism

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed entrepreneurs to unprecedented levels of uncertainty, risk and possibility of failure (Kuckertz & Brändle, Citation2022). In order to survive, entrepreneurs need support, resilience, flexibility and openness to opportunities for change and innovation (Kuckertz et al., Citation2020). For many of our participants, work in tourism had been shown to be unreliable in a crisis context, although it had previously been a steady source of income. The second entrepreneurial strategy evident amongst our participants was to diversify their business interests. This did not mean moving away from tourism work altogether, but spreading the risk by also ensuring income from other sectors, primarily agriculture and retail:

Tourism is something that I really like and I cannot say that I will leave it, but I have learned that it is important to have various sources of income. I should not limit myself to tourism only, if there are other activities that are not directly related to tourism that I can do, then I should also engage in those activities so that when something like this happens again, I will have a contingency plan. (Employee 84, with no care responsibilities, and 1-5 years in tourism, Dar es Salaam).

This tragedy has taught us to have a habit of saving and also to have something else to provide extra income, something like maybe a shop. We cannot be completely dependent on a job because when something like this happens again, we will be in trouble. When I do get some money I will start a business and not just depend on the hotel because there are some challenges, like the way right now there are no customers, meaning that we cannot even get paid in time and that becomes a problem. (Employee 92, with no care responsibilities, and 1-5 years in tourism, Dar es Salaam)

I will stay in this field because I have vast experience in it, but I will also try and find some other means to earn a living. I am thinking of selling groceries. (Vendor 23, with care responsibilities for 4-6, and 16-20 years in tourism, Zanzibar).

The nature of my work is entrepreneurial, I am not selective such that whatever work comes in front of me will be accepted, whether it is farming or sweeping, I will take the job and finish it. (Travel and Tour Operator, 81, with unknown care responsibilities, and 6-10 years in tourism, Zanzibar)

Strategy three: Moving away from tourism

The third entrepreneurial strategy we identified was to move away from tourism completely, and its associated risks. Many women in our study had suffered when the sudden onset of the pandemic, and associated limits on international travel, decimated their incomes. They were loath to find themselves in a similar situation again:

We faced a challenge because we had relied completely on one source and we had no Plan B, so when COVID came, we found ourselves having nowhere to go, so we were shaken a lot. (Travel and Tour Operator 87, with care responsibilities for 1-3, and 11-15 years in tourism, Dar es Salaam)

When something like this happens and your income is reduced or even worse you are completely laid off, as there are some people who have not yet been called back to work to this day, then you need another plan for survival like livestock keeping or other businesses that do not depend on tourism … My future plan is to completely detach myself from tourism and do business that is completely not related to tourism. (Employee 91, with care responsibilities for 4-6, and 6-10 years in tourism, Zanzibar).

I have thought of a lot of things, but the challenge is in getting the capital. I have thought of establishing a cafe because I see that it has the potential to be a good source of income. (Vendor 21, with care responsibilities for 1-3, and unknown years in tourism, Dar es Salaam)

We are waiting to see how the government will handle it and help us, because most of us depend only on this one job and we have no other means. We have to pay rent, buy food, clothing for the grandchildren, it is really difficult …I have a farm in Bagamoyo. I want to go there and engage in agriculture. I just need someone to help me with the starting capital and I will be able to go there and grow the crops that mature quickly so that I can make some money. I just wish we would get aid from the government.

Discussion

Major crises, like the pandemic, expose the vulnerability of entrepreneurs as resources dry up, uncertainty prevails and the chances of failure increase considerably (Dushnitsky et al., Citation2020). This was certainly the case for the women in our study who were already operating in a resource-scarce context in Sub-Saharan Africa (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). The women in our study all experienced this vulnerability, where risk of failure meant not only business collapse but also severe hardship and potential starvation for families. Lack of government support, patriarchal norms that limit access to funding, land ownership and powerful networks, and gendered expectations that place primary responsibility for supporting families with working age women, position our participants very differently to many entrepreneurs in the Global North who also suffered hardship during the pandemic but did have opportunity to access resources, networks and political support to help them turn adversity into resilience (Giones et al., Citation2020; Kuckertz et al., Citation2020; Kuckertz & Brändle, Citation2022). The women in our study do not fit with traditional notions of entrepreneurship (Schumpeter, Citation2000) but show both the creativity and necessity of entrepreneurship for women in precarious situations. The need to survive in unequal and insecure conditions remains a key motivator for women’s entrepreneurship. The pandemic has dramatically increased the pressures on many women working in the tourism sector, causing a shift into survival mode for far too many of our interviewees (see also Filimonau et al., Citation2022). However, our findings illustrate that many women in resource-scarce contexts like Tanzania also turned adversity into resilience. This took the form of adopting one of three entrepreneurial responses, as outlined in the findings sections above: they (re)commit to tourism and look to develop their own expertise and pursue further business opportunities; they diversify their interests so that they retain involvement in the tourism industry whilst spreading their risks through a ‘Plan B’ beyond the sector; or they move away completely from the gamble with their security and future plans that the tourism industry represents and focus their attentions elsewhere.

This presents a potentially significant problem for the tourism sector as it tries to recover and rebuild. The sector depends on women like those within our study to provide the skills and labour needed to deliver services and experiences sought by tourists. Indeed, women make up approximately 54% of the global tourism workforce, rising to 69% in Africa (UNWTO, Citation2018). Women represent 50% of all entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa, the highest proportion globally, although their businesses are usually micro or small and typically focused in the informal economy (De Vita et al., Citation2014) and significantly contribute to the tourism sector (Jiyane et al., Citation2012). If the gamble of working in the tourism industry is one that many women believe is not worth making following the devastating impacts of the pandemic, then the sector risks losing out on a significant size workforce and its important skills, services and innovations. As discussed above, many women have strong entrepreneurial ambitions that could be capitalised on to develop the tourism industry in the context of global crises that threaten the sector’s very existence, whether that be a pandemic or climate change. However, if women are not supported to focus those entrepreneurial activities within the tourism industry then they will be lost to other sectors which seem less risky. There is thus a need for the tourism industry, supported by national governments and international organisations like the UNWTO, to support women entrepreneurs specifically to keep them within the industry and to provide them with some security and protection against future shocks and crises.

Recognising entrepreneurship as a social process embedded in diverse contexts (Welter et al., Citation2019) is an important step to first understanding the experiences of women entrepreneurs in tourism and then designing policy responses to encourage and enable them to remain within the tourism industry. Our study focused on women entrepreneurs in Tanzania, a country heavily dependent on the male-dominated sectors of agriculture and manufacturing. As a patriarchal society governed by traditional gender norms, tourism offers one possible avenue for women to gain some level of economic independence and support themselves and their families. Tourism is often identified as a route for women’s empowerment, especially in the Global South. However, our study illustrates that this empowerment is fragile and confined largely to the economic realm. When a crisis strikes, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, women entrepreneurs were exposed to the risks of the tourism industry without having access to much needed support and opportunity to shape the response.

As Ojediran and Anderson (Citation2020: 12) note, “The impediment to women’s empowerment [through entrepreneurship] is the fact that they are women, which is reinforced by cultures and the dominant patriarchal social order.” Although many women in the Global South engage in entrepreneurship in tourism and other sectors, their entrepreneurship is marginalised due to deeply entrenched social, cultural and religious factors that place women in positions that limit their ability to access capital, own land and premises, and shape business strategy and policy. Therefore, entrepreneurship in tourism is only ever partially successful in empowering women. Without the means to grow their businesses and respond agilely to challenges, women’s entrepreneurial activities are always at risk of failing, particularly in the face of such an enormous and unexpected shock as the pandemic.

The women in our study are in precarious positions. As women in a patriarchal society, they are responsible for their families’ needs but not in positions of power to access much needed resources and shape decision-making and policy that might help them maximise benefits from their entrepreneurial activities. In such ways, the much-touted benefits of tourism entrepreneurship for empowering women are at best marginal: tourism entrepreneurship does offer women important opportunities for income generation but at the same time reinforces traditional gender roles through divisions of labour and unequal distribution of power and influence (Martinez Caparros, Citation2018).

This does not mean that tourism entrepreneurship is not important for women in the Global South. Rather, it points to the necessity to consider how tourism entrepreneurship can be reconstituted in ways that will enable women to be better protected and able to adapt to crises. Unless women are involved in formal decision-making, and gender is embedded in policy initiatives and tourism development plans, tourism entrepreneurship will remain a risky business for women in the Global South.

Access to finance is a key policy issue that can help women entrepreneurs survive and thrive, and thus increase the likelihood that they will remain in the tourism industry. Women in Tanzania are more likely than men to be working in the informal economy and, although women-owned enterprises (WOE) have grown from 35% in the early 1990s to 54.3% in 2012, over 99% of WOEs have fewer than five employees with almost three quarters having only one employee (Mori, Citation2015). There is also a large gender pay gap in the country (Idris, Citation2018). These factors illustrate that women were already in precarious positions in relation to starting and growing businesses prior to the pandemic, and this has only deepened with this crisis. Most of the participants in our study told us that they were held back in their entrepreneurial ambitions by a lack of access to capital to invest and/or difficulties in navigating the complex requirements of formal business registration, challenges reported in other studies and industries as well (Kapinga & Montero, Citation2017). Access to finance, business support and help with registration processes are important to enabling women to move from the informal to formal economy and thus develop businesses in tourism.

Women entrepreneurs in Tanzania and other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are facing extreme challenges in the current crisis and are operating in survival mode. Many of them have strong entrepreneurial ambitions which, if supported, could be harnessed to the benefit of the tourism industry as well as to support these women and their families. Without such support it is probable that many of the women in our study, and others like them, will be forced to move away from the tourism industry and into other sectors which appear to offer more stability and security for their futures. This would undoubtedly be a loss for the tourism sector, which will need to capitalise on as wide an entrepreneurial base as possible if it is to remain viable in the face of global challenges like pandemics and climate change.

Conclusion

This paper develops current discussions within tourism entrepreneurship that remain dominated by Anglo-Western approaches (see Kimbu et al., Citation2021). It seeks to extend the field of entrepreneurship research that is currently dominated by Global North perspectives that have a rather narrow view of entrepreneurship based on an implicit norm of a white, male, wealth creator (see Brush et al., Citation2009; Jennings & Brush, Citation2013). There is an uneasy relationship between the unspoken admiration and promotion of entrepreneurship in the Global North and the underlying exploitative and precarious working conditions of many entrepreneurs that reproduce neoliberal subjects (McCarrick & Kleine, Citation2018). This study focuses on women who do not fit the entrepreneurial norm as per some definitions, but whose activities can nevertheless be described as entrepreneurial. Driven by necessity as well as desire to improve their financial status, women entrepreneurs in the Tanzanian tourism sector illustrate the tenacity and innovation at the very heart of entrepreneurship. They have been severely affected by the devastating impacts of the pandemic on Tanzanian tourism and have responded through the adoption of one of three entrepreneurial strategies: sticking with tourism; diversifying around tourism; or, moving away from tourism. They thus both embody and transform the entrepreneurial norm and show that entrepreneurship can take many forms in differing contexts. This study thus contributes to theoretical development in relation to entrepreneurship as contextual and socially embedded, revealing that the potential for tourism entrepreneurship to empower women in the Global South is highly dependent on local, social, cultural and religious factors that shape those women’s experiences, motivations, and ability to act on their entrepreneurial ambitions. Crises like the pandemic are recognised to have caused considerable hardship and volatility for entrepreneurs around the world, increasing the risk of failure but also opening up opportunity for innovation (Dushnitsky et al., Citation2020). This study reveals the importance of embedding such understandings of entrepreneurial action, resilience and opportunity within specific socio-cultural contexts. The entrepreneurial actions described by the women in our study may be of smaller scale than the start-ups in Germany within Kuckertz et al. (Citation2020) study, but they are no less resilient or innovative. Operating within an already resource-constrained environment (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019), the women in our study demonstrate considerable resilience, flexibility, desire to grasp opportunity and innovate, all hallmarks of entrepreneurial action (Alvarez & Barney, Citation2007).

By centralising the experiences of women entrepreneurs during a time of unprecedented crisis in the tourism sector, this paper makes an important contribution to gender-aware research in tourism entrepreneurship (see Figueroa-Domecq & Segovia-Perez, Citation2020). The women in this study are impacted by the pandemic and also by their experiences as women within a patriarchal society, while working in a sector that does not value women’s work and contributions, often leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. It is thus not surprising that many women are considering no longer accepting the risk that tourism represents and are instead focusing their entrepreneurial ambitions elsewhere. We argue that this poses a very real risk to the tourism sector in its efforts to respond and rebuild following the shocks of the current global crisis. As Lugalla (Citation2018: 145) suggests, “a lack of understanding of women entrepreneurs’ growth aspirations might ultimately inhibit how best to support female entrepreneurship.” In this paper we have presented evidence of women’s entrepreneurial aspirations and limiting factors, and this has practical implications for the tourism industry to address, at local and global levels, if women entrepreneurs are to be supported to both remain within tourism AND to play an integral role in reshaping the sector. Women entrepreneurs in the Global South have a crucial role to play in the future of tourism, and need to be supported, enabled and empowered to develop their entrepreneurial ambitions within the sector by a variety of means and actions, including effective individual, professional, cultural and governmental support. The COVID-19 pandemic represents an opportunity to restructure outdated socio-economic and cultural relations and conditions that in turn will improve our capacity to respond to future crises.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerly, B., & True, J. (2008). Reflexivity in practice: Power and ethics in feminist research on international relations. International Studies Review, 10(4), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2008.00826.x

- Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1–2), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.4

- Anderson, W. (2013). Leakages in the tourism systems: Case of Zanzibar. Tourism Review, 68(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371311310084

- Anderson, W. (2015). Human Resource Needs and Skill Gaps in the Tourism and Hospitality Sector in Tanzania Consultancy Report submitted to The Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, Tanzania under World Bank - STHEP AF Project.

- Anderson, W., & Mdemu Komba, I. (2017). Female entrepreneurs and poverty reduction: hair craft SMEs in Tanzania. Development in Practice, 27(3), 392–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2017.1293008

- Anderson, W., Busagara, T., Mahangila, D., Minde, M., Bahati, V., & Olomi, D. (2017). The dialogue and advocacy initiatives for reforming the business environment of the tourism and hospitality sector in Tanzania. Tourism Review, 72(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2016-0036

- Anderson, W., Mossberg, L., & Andersson, T. (Ed). (2021). Sustainable tourism development in Tanzania. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Ateljevic, J. (2009). Tourism and entrepreneurship (S. J. Page (Eds.), 1st ed.). Routledge.

- Bahn, K., Cohen, J., & van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2020). A feminist perspective on COVID‐19 and the value of care work globally. Gender, Work, and Organization, 27(5), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12459

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brush, C. G., De Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender‐aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566260910942318

- Busenitz, L. A., Gómez, C., & Spencer, J. W. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 994–1003. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556423

- Charmaz, K. (2002). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (pp. 347–366). Sage.

- Claudio-Quiroga, G., Gil-Alana, L. A., Gil-López, Á., & Babinger, F. (2022). A gender approach to the impact of COVID-19 on tourism employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2068021

- Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., & Scarborough, W. J. (2021). COVID‐19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work, and Organization, 28(Suppl 1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506

- Creighton, C., & Omari, C. K. (2018). Introduction: Family and gender relations in Tanzania - inequality, control and resistance. In C. Creighton & C. K. Omari (Eds.), Gender, family and work in Tanzania. Routledge.

- De Vita, L., Mari, M., & Poggesi, S. (2014). Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. European Management Journal, 32, 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.07.009

- Duffy, L. N., Kline, C. S., Mowatt, R. A., & Chancellor, H. C. (2015). Women in tourism: Shifting gender ideology in the DR. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.017

- Dushnitsky, G., Graebner, M., & Zott, C. (2020). Entrepreneurial responses to crisis. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 14(4), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1383

- Elam, A. B., Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., Baumer, B., Dean, M., & Heavlow, R. (2019). Global entrepreneurship research association. In Women’s entrepreneurship report. 2018/2019. Smith College.

- Ferguson, L., & Alarcón, D. M. (2015). Gender and sustainable tourism: reflections on theory and practice. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.957208

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., & Segovia-Perez, M. (2020). Application of a gender perspective in tourism research: a theoretical and practical approach. Journal of Tourism Analysis: Revista de Análisis Turístico, 27(2), 2254.

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2022). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: a gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Filimonau, V., Matyakubov, U., Matniyozov, M., Shaken, A., & Mika, M. (2022). Women entrepreneurs in tourism in a time of a life event crisis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2091142

- Galloway, L., Kapasi, I., & Sang, K. (2015). Entrepreneurship, leadership, and the value of feminist approaches to understanding them. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(3), 683–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12178

- Ghosh, P. K., Ghosh, S. K., & Chowdhury, S. (2018). Factors hindering women entrepreneurs’ access to institutional finance-an empirical study. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 30(4), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2017.1388952

- Gillham, B. (2000). Case study research methods. Continuum.

- Giones, F., Brem, A., Pollack, J. M., Michaelis, T. L., Klyver, K., & Brinckmann, J. (2020). Revising entrepreneurial action in response to exogenous shocks: Considering the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00186

- Hughes, K. D., Saunders, C., & Denier, N. (2022). Lockdowns, pivots & triple shifts: early challenges and opportunities of the COVID-19 pandemic for women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 34(5), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2022.2042657

- Idris, I. (2018). Mapping women’s economic exclusion in Tanzania. Helpdesk report: Knowledge, evidence and learning for development (K4D). Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Mapping_Womens_Economic_Exclusion_in_Tanzania.pdf.

- ILO. (2003). Tanzanian women entrepreneurs: Going for growth. Retrieved March 20, 2022 from https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/ilo-bookstore/order-online/books/WCMS_PUBL_9221137317_EN/lang–en/index.htm.

- Je, J. S., Khoo, C., & Chiao Ling Yang, E. (2022). Gender issues in tourism organisations: insights from a two-phased pragmatic systematic literature review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 30(7), 1658–1681. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831000

- Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.782190

- Jennings, J. E., Jennings, P. D., & Sharifian, M. (2016). Living the dream? Assessing the “entrepreneurship as emancipation” perspective in a developed region. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(1), 81–110.

- Jiyane, G. V., Majanja, M. K., Ocholla, D. N., & Mostert, B. J. (2012). Contribution of informal sector women entrepreneurs to the tourism industry in eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, in KwaZulu-Natal: barriers and issues: recreation and tourism. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 18(41), 709–728.

- Kapinga, A. F., & Montero, C. S. (2017). Exploring the socio-cultural challenges of food processing women entrepreneurs in Iringa, Tanzania and strategies used to tackle them. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 7(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0076-0

- Kimbu, A. N., de Jong, A., Adam, I., Ribeiro, M., Afenyo-Agbe, E., Adeola, O., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (2021). Recontextualising Gender in Entrepreneurial Leadership. Annals of Tourism Research, 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103176

- Kuckertz, A., & Brändle, L. (2022). Creative reconstruction: A structured literature review of the early empirical research on the COVID-19 crisis and entrepreneurship. Management Review Quarterly, 72(2), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00221-0

- Kuckertz, A., Brändle, L., Gaudig, A., Hinderer, S., Reyes, C. A. M., Prochotta, A., Steinbrink, K. M., & Berger, E. S. (2020). Startups in times of crisis–A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 13, e00169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00169

- Kumar, S., & Singh, N. (2021). Entrepreneurial prospects and challenges for women amidst COVID-19: a case study of Delhi, India. Fulbright Review of Economics and Policy, 1(2), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/FREP-09-2021-0057

- Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., & Guba, E. G. (2018). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 108–150). Sage.

- Lugalla, I. M. (2018). Growth aspirations of women entrepreneurs in tourism in Tanzania [Doctoral thesis]. University of Groningen.

- Maliva, N. S. (2017). Women entrepreneurs’ strategies and tourism development in Zanzibar. Business Management Review, January-June, 110–130.

- Maliva, N., & Mwaipopo, L. (2017). Gender and women entrepreneurs’ strategies in tourism markets: A comparison between Tanzania and Sweden. Operations Research Society of Eastern Africa, 7(2), 1–12. Retrieved January 10, 22, from https://orseajournal.udsm.ac.tz/index.php/orsea/article/view/62.

- Martinez Caparros, B. (2018). Trekking to women’s empowerment: A case study of a female-operated travel company in Ladakh. In S. Cole (Ed.), Gender equality and tourism: Beyond empowerment (pp. 57–66). CABI.

- McAllum, K., Fox, S., Simpson, M., & Unson, C. (2019). A comparative tale of two methods: How thematic and narrative analyses author the data story differently. Communication Research and Practice, 5(4), 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2019.1677068

- McCarrick, H., & Kleine, D. J. (2018). Digital inclusion, female entrepreneurship and the production of neoliberal subjects—views from Chile and Tanzania. In M. Graham (Ed.), Digital economies at global margins (pp. 103–128). MIT Press.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism. (2020). Comprehensive COVID-19 recovery and sustainability plan for tourism sector in Tanzania 2020/21-2024/25 – Draft, September. The United Republic of Tanzania.

- Mordi, C., Simpson, R., Singh, S., & Okafor, C. (2010). The role of cultural values in understanding the challenges faced by female entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411011019904

- Mori, N. (2015). Women’s Entrepreneurship Development in Tanzania: Insights and Recommendations. Report number 14.04.2. International Labour Organization (ILO). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4163.1444

- Ngoasong, M. Z., & Kimbu, A. N. (2019). Why hurry? The slow process of high growth in women‐owned businesses in a resource‐scarce context. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12493

- Ojediran, F., & Anderson, A. (2020). Women’s entrepreneurship in the global south: empowering and emancipating? Administrative Sciences, 10(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10040087

- Phommavong, S., & Sörensson, E. (2014). Ethnic tourism in Lao PDR: Gendered divisions of labour in community-based tourism for poverty reduction. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(4), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.721758

- Rindova, V., Barry, D., & Ketchen, D. J.Jr, (2009). Entrepreneuring as emancipation. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 477–491. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.40632647

- Schumpeter, J. A. (2000). Entrepreneurship as Innovation. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1512266

- Statista. (2021). Earnings from visitors at tourist attraction sites in Tanzania in Q1 2021, by geographical zone. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1149350/earnings-from-visitors-at-tourist-attraction-sites-in-tanzania-by-zone/.

- Stevenson, L., & St-Onge, A. (2005). Support for growth-oriented women entrepreneurs in Uganda. International Labour Organization.

- Suluo, S. J., Mossberg, L., Andersson, T. D., Anderson, W., & Assad, M. J. (2020). Corporate sustainability practices in tourism—Evidence from Tanzania. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2020.1850515

- Sun, Y. Y., Li, M., Lenzen, M., Malik, A., & Pomponi, F. (2022). Tourism, job vulnerability and income inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(1), 100046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2022.100046

- The Office of the Chief Government Statistician. (2016). Household budget survey 2014/15. OCGS.

- The Office of the Chief Government Statistician. (2019). Women and men in Zanzibar: Facts and figures. Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar. February 2019.

- Thien, O. S. (2009). Women empowerment through tourism—from social entrepreneur perspective. http://edepot.wur.nl/11305.

- Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Trupp, A., & Sunanta, S. (2017). Gendered practices in urban ethnic tourism in Thailand. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.02.004

- Tucker, H. (2022). Gendering sustainability’s contradictions: between change and continuity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1500–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1839902

- UNWTO. (2018). Global report on women in tourism (2nd ed.). World Tourism Organisation.

- UNWTO. (2021). UNWTO inclusive recovery guide: Sociocultural impacts of COVID-19. Issue 3: women in tourism. World Tourism Organisation.

- UNWTO. (2022). New guidelines put women’s empowerment at heart of tourism’s restart. World Tourism Organisation. Retrieved July 2, 2022, from https://www.unwto.org/news/new-guidelines-put-women-s-empowerment-at-heart-of-tourism-s-restart.

- Welter, F., Baker, T., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Three waves and counting: the rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0094-5

- World Bank. (2021). Transforming tourism: Toward a sustainable, resilient, and inclusive sector (English). World Bank Group. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/794611627497650414/Transforming-Tourism-Toward-a-Sustainable-Resilient-and-Inclusive-Sector.

- Zhang, W., Williams, A. M., Li, G., & Liu, A. (2022). Entrepreneurial responses to uncertainties during the COVID-19 recovery: A longitudinal study of B&Bs in Zhangjiajie, China. Tourism Management, 91, 104525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104525