Abstract

Barcelona is an attractive location in Spain for tourism entrepreneurship; however, women are significantly under-represented. This study adopts a locally based perspective and a feminist ethic of care theoretical lens to give voice to tourism women entrepreneurs and members of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona. The aim of our analysis is to understand the culture of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and seeks to answer the following research question: How does an entrepreneurial ecosystem that operates in a tourism entrepreneurship context characterized by gendered barriers, find support through gender equity resources and policies? To address this question, we have applied feminist theory to analyze the semi-structured interviews with female entrepreneurs and individuals committed to Barcelona’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. Our analysis revealed three main gender equity-related issues i.) Hunting and caring: The Gender Entrepreneurship Division; ii.) Social Conditioning and gender norms: Reinforcing Gender Inequities and iii.) Entrepreneuring and the Motherhood Penalty. Our findings draw attention to gender biases and opportunities to enhance equity in the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona by employing an ethic of care and committing to diversification. We offer a theoretical framework to understand and respond to gender inequities to enhance the success of women tourism entrepreneurs.

Introduction

In Europe, the rate of entrepreneurial activity among women stands at only 5.7%, compared with a worldwide average of 11% (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Citation2022). Gender gaps are often accentuated in advanced economies where business ownership is less of a necessity and more of an option. The European Union estimates that, by 2050, improving gender equity could lead to a significant increase in GDP by 6.1 to 9.6% per capita amounting to €1.95 to €3.15 trillion (European Institute for Gender Equality, Citation2017). The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, specifically SDG 5 Gender Equality, supports gender based practical solutions worldwide (United Nations, Citation2022). Our work contributes to Target 5.5 and is in line with SDG 8 promoting Decent Work and Economic Growth and its Target 8.3 that encourages policies to support job creation, growing enterprises and entrepreneurship.

Research on female entrepreneurial roles in tourism and the gender-based obstacles they face are scarce (see Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Freund & Hernandez-Maskivker, Citation2021 for exceptions; Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016). Unfortunately, contemporary tourism sector practices further perpetuate gender inequities where women hold low level, unstable jobs, face wage disparities (Hutchings et al., Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2019), and are under-represented in senior management (Equality in Tourism, Citation2018). In the Spanish tourism sector specifically, little attention has been paid to the field of gender studies, despite its impact on the Spanish economy and the importance of women in tourism as entrepreneurs and employees (Segovia-Pérez & Figueroa-Domecq, Citation2014).

For women entrepreneurs to thrive, it is important to cultivate a supportive environment including investment support in both human and financial capital, creating opportunities for growth, and a mixture of innovative and progressive institutional and infrastructural provisions (Bullough et al., Citation2022). Importantly, equitable access to financial capital and the promotion of practices that support women’s businesses are required (Brush et al., Citation2019). The culture of the ecosystem; however, is often rooted in non-transparent rules, practices, and norms (Brush et al., Citation2019) and persistent negative stereotypes negatively impact women business owners. Such structural barriers might be mitigated through incubators, accelerators, and business networks when they are committed to supporting women entrepreneurs (GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), Citation2022).

Barcelona is a leading tourism destination worldwide and one of the most attractive locations for entrepreneurship in the country. While it is recognized as a city with the ability to foster growth for women entrepreneurs in Spain (Tarr, Citation2019), only 3 in every 10 entrepreneurs are women (Mastercard, Citation2019). This gender disparity suggests that the entrepreneurial path for women is likely not easy. Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020b) in a comprehensive analysis of 127 female tourism entrepreneurship related publications found that most research (52,1%) focuses on rural contexts, only 28.3% of articles explored policy and governance, and few engaged with critical theories. Accordingly, there is a clear gap in the scholarship exploring female entrepreneurship in urban environments in the Spanish tourism sector and suggesting policies which may assist women tourism entrepreneurs.

The aim of our research is to understand the culture of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona and determine supports which may assist women tourism entrepreneurs. This paper adopts a locally based perspective (Kimbu et al., Citation2021) focusing on Barcelona, Spain that has been underexplored (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020b) and a feminist ethic of care approach (Gilligan, Citation1982) to give voice to women entrepreneurs and members of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona. Taking up critical feminist theory responds to a gap pointed out by Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020b) in the tourism entrepreneurship literature, as well as responding to calls for scholarly work to engage with reflexive, feminist politics, contributing to the scholarly debate on feminist ethic of care (Boluk & Panse, Citation2022; Higgins-Desbiolles & Monga, Citation2021; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014; Pritchard, Citation2018, Carnicelli & Boluk, Citation2021). Accordingly, such theoretical approaches are vital in enhancing our understandings of gendered tourism entrepreneurship (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020b).

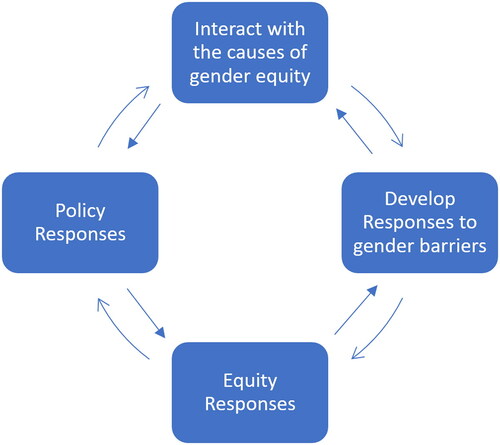

Considering the foregoing literature, this paper seeks to answer the following research question: How does an entrepreneurial ecosystem that operates in a tourism entrepreneurship context characterized by gendered barriers, find support through gender equity resources and policies? To address this question, we have applied feminist theory (Gilligan, Citation1982; Noddings, Citation2012) to analyze the qualitative data in the Barcelona context. Building on the existing scholarship (i.e., Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020b; Boluk & Panse, Citation2022) and stemming from our analysis, we have identified the specific gender barriers in the tourism entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona and proposed equity and policy responses required. Based on our analysis we offer a theoretical framework that may be useful beyond our context in Spain for uncovering the policy responses necessary for addressing gendered barriers within a tourism entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Figure 1. A framework for understanding gendered barriers in tourism entrepreneurial ecosystems and supports required.

Table 1. Specific barriers faced by women tourism entrepreneurs and insufficient gender equity policies in Spain.

Table 2. Background of the sample.

The paper proceeds with a discussion of the main obstacles faced by female entrepreneurs in the current literature and an overview of the main social policies regarding gender and entrepreneurship in Spain. Next, the theoretical framework guiding the study a feminist ethic of care is presented. This is followed by our methodological discussion detailing our qualitative approach, sample profiles, and our process of employing the strategies of grounded theory in analyzing the semi-structured interviews of female entrepreneurs and individuals committed to Barcelona’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. A presentation of our analysis follows revealing three main gender equity-related issues. Our findings draw attention to gender biases in the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona that could be enhanced by employing an ethic of care and commitment to diversification. By bringing awareness to the inequities faced by women, we offer recommendations and policy suggestions which may support the success of women tourism entrepreneurs in Spain. Finally, the paper draws conclusions and offers suggestions for future research.

Literature review

Entrepreneurship is an obstacles race. The following section explores the constraints faced by tourism female entrepreneurs in Spain, focusing on the current employment situation, their access to financial capital, and their caring responsibilities. The next section will examine social policies currently implemented in the Spanish economy, and the last section reframes current conceptualizations of tourism entrepreneurship giving voice to women by introducing the theoretical framework that guides the research a feminist ethic of care.

Exploring obstacles faced by female tourism entrepreneurs

Regardless of gender, entrepreneurs typically face obstacles when starting a business regarding managing time, securing funds, and finding support. But several scholars have noted that such barriers are exacerbated for female entrepreneurs and go beyond the general barriers for entrepreneurship (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2013; Verheul & Thurik, Citation2001). The scholarship suggests women face harder setbacks compared to men, because of their education, previous experiences, care responsibilities, networking limitations, risk aversion, social norms, and stereotypes (i.e., Abouzahr et al., Citation2018; Alonso-Almeida, Citation2013; Klyver & Grant, Citation2010; Kwapisz & Hechavarría, Citation2018; Verheul & Thurik, Citation2001; Zhang et al., Citation2020). There are three main obstacles to female tourism entrepreneurs presented in the literature which will discuss below.

Firstly, the current employment situation in tourism presents an obstacle to female entrepreneurship, for starting off with a weak capital base is claimed to be seriously detrimental (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2013). It is commonly accepted that economic freedom is crucial for entrepreneurship to occur (Verheul & Thurik, Citation2001). UNWTO (Citation2019) reports that 54% of people employed in tourism are women; however, women hold low level, low paying, precarious jobs (Freund & Hernandez-Maskivker, Citation2021; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2019), and face wage disparities earning 14.7% less than men (UNWTO, Citation2019). Focusing on Spain, female tourism workers receive less than 80% of men’s average annual salaries in the sector, earning less than 51% of the average salary in Spain. Furthermore, 38% of female professionals have temporary contracts and 36% work part time (CCOO Servicios, Citation2019).

Secondly, access to financial capital and the capital management of female-led entrepreneurship businesses has proved to be affected by gender biases (Abouzahr et al., Citation2018; Verheul & Thurik, Citation2001). Indeed, female entrepreneurs obtain only 80 cents of capital for every dollar that men receive, even if companies led by women generate 10% more cumulative revenue than men in a 5-year period (Abouzahr et al., Citation2018). Women entrepreneurs in Canada, for example, receive just 4% of venture capital funding available, in part due to gender biases against women entrepreneurs and the types of businesses they start (Sultana & Ravanera, Citation2020). A lack of gender-balance in accessing external funding hampers success and viability of their projects. In this sense, Kwapisz and Hechavarría (Citation2018) claim that female entrepreneurs are traditionally assigned a role of compliance that minimizes the perception of their financial management capabilities during the start-up process.

Thirdly, societal pressure impacts if women enter, and how they may navigate the entrepreneurial ecosystem while managing caring responsibilities. Care work may limit activities women are able to engage in outside of traditional work hours which generally has more rigid schedules and where the sexual division of work is presented with greater force (Carrasco et al., Citation2011). A greater responsibility for providing care often disadvantages women in pursuing paid work and entrepreneurship (Stroh & Reilly, Citation2012). Precisely, women are more likely than men to be perceived to have a duty of care for both their households and children. Unfortunately, data shows that it is much more than just a perception; in Europe 79% of women engage in household activities every day and more than four over ten Europeans (44%) believe that the utmost important role of women in society is to provide childcare (European Commission, Citation2018). Thus, caring responsibilities may impact the capability of women to engage in networking opportunities and may lead women to be more isolated in their professional lives, resulting in a reduction of their network’s size and effectiveness (Klyver & Grant, Citation2010) and play a role on the composition and the prosperity of their networks (Benschop, Citation2009).

A low representation of female entrepreneurs has the potential for negative impacts not only in terms of economic impact, but also in relation to our understandings of equity and social justice (Chambers et al., Citation2017; Jamal & Higham, Citation2021; Moreno-Alarcón, Citation2020). Research suggests women excel at providing business development with a sense of understanding and sensibility towards both service quality and employment conditions (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2012). Women also place a high importance on community well-being (Tajeddini et al., Citation2017), and are more likely to initiate businesses with the intention of creating wealth in their communities (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2013) and making a difference (GEM, 2020). Therefore, female entrepreneurs are important contributors to communities making broad impacts beyond just economic contributions. The following section explores the social policies implemented by Spanish institutions and the European Union to respond to the obstacles discussed.

Examining social policies in the Spanish economy

Recognition of gender inequity has historically determined women’s participation in the Spanish economy (Muñoz & Pérez, Citation2007). As such, tackling gender inequity in entrepreneurship is as much a strategic decision as it is a question of principles (Government of Spain. High Commissioner for Spain Nation of Entrepreneurship, Citation2021). While entrepreneurship is not explicitly mentioned in the national Gender Equality law of 2007, it features regulations to achieve gender balance (see Art.75 on the participation of women in the Boards of Directors of commercial companies) (Law 03/2007, of March 20, 2007, on gender equality for men and women, 2007). Gender balance in the professional field is still far from reality. For example, currently, Spain places a strong focus on leveraging the gender wage pay gap. Thus, companies with at least 50 employees are required to register their salaries disaggregated by gender and professional category (Law 06/2019 of March 1, 2019). Accordingly, companies are required to justify salary disparities ensuring they are not due to gender. Importantly, only in those cases where the average remuneration received by one sex or the other exceeds 25%, taking as a reference the set of paid perceptions. Notably, less than 25% differences in wages are regarded as “normal” in Spain.

Spanish institutions have made efforts to include gender sensitive measures in entrepreneurship laws by creating gender-specific development plans. For instance, the RENACE project, aims to “initiate actions to develop, attract and retain women talent” (Spain Nation of Entrepreneurship, 2021, p. 92) through, the provision of educational and advisory support for female entrepreneurs and, particularly, investors to increase women’s interest in engaging in entrepreneurship. Another project led by the Spanish Chamber of Commerce through the PAEM (the national business support program for women) provides a range of financial services like, non-guaranteed microcredits, subsidies and guaranteed obtention support, as well as training and networking spaces so women may readily access resources for entrepreneurship (Chamber of Commerce of Spain, Citation2022). Our key findings from our literature review and exploration of policies supporting women entrepreneurs in Spain is captured in . The barriers recognized in the literature and insufficient gender equity policies signal the importance in engaging with feminist theory and enhancing provisions for SDG 5 Gender Equality and SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth.

The European Commission (Citation2021) states one of its main goals is to foster education at all levels to support female entrepreneurs boosting their morale. The Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan aims to increase awareness of females in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, by supporting business and family life. Both public institutions and several scholars continue to understand entrepreneurship as a subject position in which men outperform women (Vujko et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, in response to this, they specifically attend to the supports required by women “to win the race”; however, we argue here we need to engage with feminist theory and specifically an ethic of care to shift feminist debates more firmly from the margins to the center of discussions (Boluk & Panse, Citation2022; Carnicelli & Boluk, Citation2021; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020b; Pritchard, Citation2018). We position ourselves with feminist economics as a transformative thought that proposes a new paradigm that places care work as a determining aspect of social reproduction and the living conditions of the population (Carrasco et al., Citation2011). For our analysis then it is critical to acknowledge that Spanish institutions and current policy seem somewhat committed to reduce gender inequities in entrepreneurship; however, our findings reveal insufficient gender sensitivity reinforcing the empirical importance to contribute to the debate on gender equity, and to encourage further policy recommendations.

The global backdrop, specifically the health crises brought on by COVID-19 has drawn attention to a variety of inequities society faces. It is against this backdrop that deep reflection on care is needed. Some have argued that society faces a crisis of care, exacerbated by neoliberal capitalism supporting careless states and communities (Chatzidakis et al., Citation2021). We argue that such moments call us to action. This view supports calls for new tourism practices to re-centering human well-being (Boluk et al., Citation2019) guided by attending to relationships and showing care for others (Gilligan, Citation1982). As such, a feminist ethic of care may equip us with the necessary insights to re-center care in entrepreneurial ecosystems supporting the tourism sector. In our case we use this moment to reflect on insufficient gender and social policies in the entrepreneurial space calling for a paradigm shift. The next section will detail the theoretical framework adopted a feminist ethic of care.

Theoretical framework: feminist ethic of care

An ethic of care is a feminist, critical theory because it profoundly challenges historically constructed gender normativity and power relations (Robinson, Citation2018). The foundations of care theory can be traced back to Carol Gilligan’s (Citation1982) seminal book entitled In a Different Voice. Gilligan’s (Citation1982) work importantly drew attention to a preference for listening to and attending to the masculine experience and a natural understanding of the male experience as the experience. With this knowing, Gilligan’s (Citation1982) analysis has been guided by questions about voice, relationship, and psychological processes and theory, leaning into the silenced experiences of women. Gilligan (Citation1982) argues

In the different voice of women lies the truth of an ethic of care, the tie between relationship and responsibility, and the origins of aggression in the failure of connection (p. 173) […] The failure to see the different reality of women’s lives and to hear the differences in their voices stems in part from the assumption that there is a single mode of social experience and interpretation (p. 174).

Fundamentally, Gilligan (Citation1982) emphasizes that care is an activity of relationship responding to individual needs. This is further supported by Noddings (Citation2012) who asserts “in care ethics, relation is ontologically basic, and the caring relation is ethically (morally) basic. Every human life starts in relation, and it is through relations that a human individual emerges” (p. 771). Importantly, Noddings (Citation2012) work on an ethic of care is premised on the mutual nature of care between the individual who provides care and the individual on the receiving end of care. Robinson’s (Citation2006) analysis on an ethic of care argues the importance of “attentiveness to details, responsiveness to particular others, and responsibility over the long-term” (p. 337). Contemporaneously situated within an array of crises and driven by neoliberal ideology focusing on production and consumption, demonstrating responsibility and a capacity to be attentive and responsive to the needs of others is challenged. Importantly, an ethic of care is an approach to morality and emphasizes a complex web of interdependence and relationship with others (Gilligan, Citation1982; Tronto, Citation1993).

Employing an ethic of care lens is particularly important in response to concerns expressed by Pritchard (Citation2018) regarding the limited analyses carried out in the tourism scholarship employing feminist perspectives and limited research specifically adopting an ethic of care (see Carnicelli & Boluk, Citation2021; Higgins-Desbiolles & Monga, Citation2021; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014 for exceptions). Accordingly, our analysis here contributes to this important scholarly debate.

Methodology

Context and participants

The aim of this research is to centre the female experience in the tourism entrepreneurship ecosystem in Barcelona, Spain to understand the culture of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and determine supports which may assist women tourism entrepreneurs. We also examine the contributions of our analysis to progressing SDG 5 and SDG 8. Our choice to focus on the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona responds to the scarcity of research on the gendered experiences of urban based entrepreneurs which has not adequately reflected the “diverse and complex experiences” of tourism entrepreneurs (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020a, p. 10) adopting a feminist ethic of care approach. With this in mind, we conducted 11 semi-structured interviews categorized using the work of Block et al. (Citation2018) and Colombelli et al. (Citation2019) as a guiding principle. Our convenience sample consisted of 11 informants selected on an accessibility basis from an internal university database of contacts. Besides female entrepreneurs in the formal economy, we categorized active entrepreneurial investing agents to obtain a cross sectional view. Specifically, interviews were carried out with a university-based fund, an accelerator, a social venture fund and two types of investors namely an angel network, and a corporate venture capitalist. Moreover, given the high intervention of the government in the Spanish entrepreneurial ecosystem (Alesina & Glaeser, Citation2006), Catalonia’s government funded entrepreneurial supporting institution was also included in the study.

The interview questions were constructed based on the review of the literature and identification of the main barriers faced by female entrepreneurs. As such, we used the main barriers as a compass to guide our study. Interviews were carried out between March and April 2020 through digital platforms, in view of the pandemic lockdown. The interviews lasted between 50 to 75 min, and were recorded, transcribed, and translated into English with participants’ consent. The transcripts were coded, and informants were assigned pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality. We classified informants as female, or male based on their affirmed gender. shows the background of the interviewees.

Analysis: strategies of grounded theory

The researchers employed strategies of constructivist grounded theory to guide the analysis (Charmaz, Citation2011). Adopting this process involved engaging in a close line by line reading of the transcripts, developing codes based on our dealings with the data including summarising, synthesizing, and sorting our data (Charmaz, Citation2011). Our team recorded memos throughout our entire process of analysing the data and we regularly met throughout the data collection and analysis process to discuss our analysis and memos which led to the development of tentative analytical categories. Iterative communication and analysis among the research team led to the refinement of the categories (Charmaz, Citation2011) which are presented below. This process reflects a blended analytic process leading to a “systematic rendering of data analysis” as prescribed by Creswell (Citation2013, p. 35). Our analysis was informed by an ethic of care lens, and as such centres important considerations required for thinking about cultivating inclusive spaces in relation to the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona which could have implications for inclusivity beyond just this context. The following section will detail the three categories emerging from our analysis.

Findings

The analysis conducted revealed three main categories. The first, : The Gender Entrepreneurship Division, draws attention to a patriarchal ecosystem where women are often left out. The second category, Social Conditioning, and gender norms: Reinforcing Gender Inequities, illustrates the use of accepted sexist language, current educational biases, and the glass ceiling women entrepreneurs face. The final category, Entrepreneuring and the Motherhood Penalty, discusses the intricacies of caring roles and the barriers presented for female entrepreneurs.

Hunting and caring: the Gender Entrepreneurship Division

This category refers to gendered leadership styles and instead of approaching such differences with an appreciative and caring lens our data revealed the leadership differences between genders were perceived negatively. Specifically, our analysis highlighted men were perceived as strong, and women were often perceived as soft and averse to risk.

Several adjectives were used by our informants to describe the leadership styles of men including men aim higher, they are hard sellers, ask for more money, and they are more aggressive. In contrast, the leadership styles of women were described as sensitive, purpose-led, and values-led. Women were recognized as more cautious than men, demonstrating care in their work, and concerned with making a social impact. For example, one informant said this “They bring caring attitudes into the tourism business, recognizing diverse interests within their communities” (Natalia, Entrepreneur). Our data clearly revealed a difference in the value-led orientation of informants.

Importantly, the conduct of women and men was recognized in the data as playing an important role in securing funds. For example, Laura (University Fund) said that “men have a deeper voice, are more authoritative and representative in entrepreneurship.” The authority of some male entrepreneurs, palpable in the depth of their voice seemed to serve as an advantage. Another female informant, referred to the general way male entrepreneurs conduct themselves and take up space in a room which contrasts the approach of women entrepreneurs and may implicitly create disadvantages when seeking funds. She said,

We start our business differently because we are different and, when asking for funding, too. Even when we express ourselves, we are different, if you listen to a man, his position when he speaks is much more static, they usually spread their legs, right? They stick out their chests while explaining what they want and are not ashamed to tell you […] A woman always presents herself differently. Even the way we dress limits us sometimes, right? If you wear a blouse or high heels, you can get stared at, you can get uncomfortable, then […] right? You shrink a little and you already speak differently. (Natalia, Entrepreneur)

Aside from recognizing the different conduct of men and women, the data revealed what seemed like different expectations of genders. Specifically, the data illustrated women entrepreneurs are pressed more in areas they are perceived to be weaker. For example, Marta shared,

The investors in front of you are usually men not women, thus you feel less empathy. The questions they ask are different; a woman is always asked more about commitment and a man for big numbers […] therefore the answers […] if the questions are already focused differently, the answers will never be the same, right? (Marta, Entrepreneur).

Importantly, Marta referred to a difference in the types of questions women entrepreneurs receive regarding funding. This nuance in addition to the lack of female representation and the lack of equal opportunities for women may lead to feelings that women need to go above and beyond to earn a seat at the table. This was explicitly recognized by Sara (Business Angel) who stated, “as a woman you have additional pressures, you always have to demonstrate more than a man in equal conditions.” This gender division leaves minorities at the margins which was further reinforced by Pablo (Corporate Venture) when he said this “To give you an idea: of approximately 35 projects that I have presented to the investment committee, only 4 were led directly by women.” Accordingly, investment is masculinized, meaning men often decide who to grant funding to and this impacts who and how entrepreneurs ask for funding, and this reinforces the patriarchal system favoring men.

Considering the above, our data disclosed that the gender division reinforces an unconscious bias and, in some instances, has resulted in some women adopting male mannerisms to attempt to be more alike their successful male peers. For example, Luisa (Entrepreneur) said some women “feel that they should mirror men’s style to succeed.” This was reinforced by another female entrepreneur informant who put it like this:

If I look very feminine and I go like: We want 5 million euros […] they would say: Wait, who is this girl and what is she doing here? I think there are many cases in political campaigns where leaders like Hillary Clinton and Angela Merkel mimic the look dressing a lot like males (Silvia, Entrepreneur).

Social conditioning and gender norms: reinforcing gender inequities

The data disclosed evidence of a gender biased ecosystem nurtured by societal gender norms imposed from childbirth treating boys and girls differently and expecting them to conform, with what is accepted by society. Gender norms are learned by observing others, by observing how people behave around us and this cultivates, in turn, cultural biases. In this ecosystem, biases impact the way women request money, and the way they are perceived by investors. This social conditioning is built in a sexist society where stereotypes might hinder the success of women. These unconscious biases affect both female and male views.

Maria (Governmental Venture Capital) reflected on some unconscious biases that are common but not discussed, “we put prejudices inside our heads that are totally educational and socially measured, so for example, women are not visualized in power, with money and decision making.” These statements impact funding questions creating differences depending on the gender of the candidates from the moment the entrepreneur walks on stage. For example, the biases directed toward women, influence questions about child-care and commitment to one’s entrepreneurial pursuits. However, “[…] women who got into the sector was because they were ready […] once they got in, they are not going to come out. I believe the opposite, because I found entrepreneurs who did not have the sufficient base or fundamentals, who were impulsive and who started in the entrepreneurial sector when they still did not know so much, those ones are likely to leave” (Ana, Social Venture Fund).

Due to this social conditioning, women must face the so-called ‘glass ceiling’, which includes all the taboos, biases, and prejudices that society holds locking women to prescribed pathways. It is harder for women to get respect from investors, to consider themselves as another player on the entrepreneurial ecosystem. For instance, Pablo (Corporate Venture) said this,

If you ask a woman, an entrepreneur, a twenty-five-year-old girl, she will tell you, yes, that she has encountered obstacles, she will tell you that there are guys who look at her as a woman and want to fuck her […] all this happens, because the world is still like that, isn’t it? But, in all the objective issues that we are mentioning, no difference. Because this woman is a real leader, she’s a gritty chick and, I would invest blindly in her company, being a woman; it doesn’t make any difference to me.

This reflection from Pablo reveals tension. On the one hand he sheds light on how women in business are sometimes perceived to be sexual objects. While recognizing that this is not right, and demonstrating support for women entrepreneurs, the sexiest language used here (and throughout the interview) evidenced in the use of the word “chick” is done so with total acceptance and may continue to create divisions and reinforce gender inequities. Interestingly, gender inequity was challenged by another male informant, Jordi (Accelerator) who said,

The professional investor ignores everything […] he does not give a damn about the project, the product, the person. What he wants, is to make money so, if he sees a product that can make money and a leader who can take it forward, he doesn’t give a damn if they wear a skirt or a tie, okay? […] it’s a matter of you aspiring to the final goal of wanting something. And a woman who inspires you is as good as a man.”

While Jordi drew attention to the entrepreneurial system supporting good ideas, the type of language chosen depicting the ways gendered understandings manifests in entrepreneurs dress (wearing skirts or ties) is important. Furthermore, noting that women could be as “good as a man” reinforces the patriarchal ecosystem. It is this ecosystem which favors men and continues to construct gendered biased barriers for women.

The data showed the current ecosystem has an impact on the morale of women, especially young women, as they place limitations on themselves. Self-doubt, mostly related to the viability of their ideas was apparent in the data. In an ecosystem dominated by men, female entrepreneurs felt vulnerable because it was assumed that “men trust men.” An important concern shared among our informants was that society is missing female role models in positions of responsibility. Specifically, Carla (Entrepreneur) put it like this:

Role models are important as they have a lot of capacity to help women move forward and become entrepreneurs […] there are almost no examples, no role models, and that is because we hardly ever reach positions of responsibility and higher decision-making.

Education is fundamental because it is a narrow-mindedness to have a barrier as a woman or as a man […] I do think that education is the only thing that will really lead to this […] because everything else is artificial and then you will always find barriers.

It is important to have diversity, as diversity enriches business, diversity brings talent which is fundamental for any company that wants to be competitive. This was reinforced by Maria (Governmental Venture Capital) who said, “There must be women entrepreneurs, women working, women at the top and women making decisions and taking the lead together with men and with other types of diversity.” Accordingly, supporting diversity was deemed essential for supporting an inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem. The final category centers the impact of life choices including having a family as an additional barrier for entrepreneurs in our study.

Entrepreneuring and the motherhood penalty

Our study revealed that motherhood is one of the biggest hurdles impacting women’s entrepreneurial path. Respondents associated being a mother with a burden due to two main aspects: Stereotypes about childhood and co-responsibility and values established in the ecosystem positively associating success with long working hours. As Ana (Social Venture Fund) put it, “It seems that the ideal entrepreneur must forget about family, lock themselves up for three years, not talk to anyone and just dedicate themselves to doing business. So, of course, it would be more difficult for women to make this sacrifice and not keep up with our family plans or family obligations.”

Motherhood becomes a barrier not only due to the social constructions or lack of co- responsibility but as a taken for granted assumption that is directly discriminatory. For example, all our informants agreed that men are not asked about family obligations during their pitches, conversely women are, and as a result, responsibility is juxtaposed with family planning, emphasizing normative masculine understandings of success and profit generation at all costs. Luisa (Entrepreneur), for example, had this to say,

Many people stop their professional career in companies because they say: "Oh, now is not the time to have children or to move forward! Or even the businesspeople who say: this girl will soon take a leave of absence because she will have children and then she will perform less […] There is a negative connotation associated with having a family and motherhood linked to business and work and until we overcome this, this negative connotation will affect entrepreneurs and workers.”

The assumption that motherhood can interfere with productivity forces female entrepreneurs to choose between having a family or starting a business, on top of that due to the lack of co-responsibility and the fact that housework or caring for the children still fall on women, force women to decide if or what to sacrifice. Further reflecting on the motherhood dilemma, Marta (Entrepreneur) stated, “There is a time in life when you take a decision of life and maturity, to become a mother, and unfortunately if there is not co-responsibility 50-50 it is very complicated and a barrier as at the end you don’t have time to balance both.”

Our data exposes that motherhood hinders entrepreneurship as investors want to see professionals fully dedicated to guarantee success on the capital invested. A glaring question is why isn’t fatherhood a barrier for male entrepreneurs? If caregiving is not shared, or in other words responsibility for the children, women continue to be linked with caring obligations and this will continue to impact their job opportunities and success. One example illustrated was an inability to engage in networking activities. Networking was noted as a basic activity to connect with and build relationships with investors; however, informants noted women are excluded due to their caring obligations.

Men have spaces, they have more resources, meeting spaces such as clubs and so on, not only social networks but clubs where they can network, share business experiences […] and in the case of women, there is a lack of these spaces and, in fact, if we look at the United States and England there are already initiatives of clubs that are working wonderfully for women (Silvia, Entrepreneur).

The creation of intentional spaces for male entrepreneurs to network places them at an advantage, especially given that many women felt they were not socialized to network. Accordingly, the economic system should respond to this concern and design a framework for equal opportunities where women’s skills are valued and supported to reach top positions fostering positive perceptions and increasing the visibility of female entrepreneurs.

Discussion

Women are key to achieving sustainable development and to implement the SDGs in tourism. Yet importantly this is not women’s work exclusively. By using a feminist ethic of care lens, we recognise the importance of relationality as a win-win strategy to break barriers. Progressing gender equity will require all genders and changes in the institutions which govern societies (Mathews & Nunn, Citation2020). Our analysis here is informed by a feminist ethic of care lens to recognize and spotlight the continued assumption that a masculine experience is the human experience when it comes to supporting and funding tourism entrepreneurs in Spain. As our findings reveal, gender inequities are still present in the tourism entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona, Spain. Male investors outnumber female investors, questions posed to female entrepreneurs are different to their male counterparts, and there are gendered differences in leadership styles, which are often perceived negatively. All of this may lead to insecurities felt by women and feelings that women need to go above and beyond to earn a seat at the table. Specifically, our data revealed implicit biases underpinning the performance and success of male entrepreneurs in securing capital, supporting previous studies (Kwapisz & Hechavarría, Citation2018). Our findings hold up the view that gender biases and embedded traditional masculine attitudes affect our understandings of what successful entrepreneurs look like (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2012). conveys the gender barriers in the tourism entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona, Spain and equity and policy responses required.

Table 3. Understanding gender barriers in the tourism entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona, Spain through equity and policy responses.

To address the key question underpinning this study: How does an entrepreneurial ecosystem that operates in a tourism entrepreneurship context characterized by gendered barriers be supported through gender equity resources and policies? we propose a theoretical framework (see ). This framework will be useful beyond the Spanish context explored here, to understand gender inequities and develop appropriate responses.

Our data revealed evidence of social conditioning reinforcing gender inequities in the tourism entrepreneurial space. For example, while a couple of male venture capitalists revealed their care and allyship for, and with female entrepreneurs, the disparaging language (although this may not have been intended) draws attention to a fissure which may further perpetuate gender inequities. Evidently, attending to implicit biases is needed and could be addressed via a series of educational training sessions, and dialogue with women entrepreneurs, which may begin to repair such fissures. Gilligan (Citation1982) reminds us that “crisis reveals character” and “crisis also creates character” (p. 126). Accordingly, creating bridges may counterpose some of the social conditioning reinforcing gender inequities encouraging responsibility and living in relationship with each other.

Formal and informal factors impact the entrepreneurship ecosystem. Our analysis suggested that informal factors such as the lack of female role models or the lack of strong networking systems, have a high impact in determining the success of female entrepreneurs. These results reinforce findings in the literature where females experienced a reduction of their network’s size and effectiveness (Klyver & Grant, Citation2010) and impact on the composition and the prosperity of their networks (Benschop, Citation2009). Women’s associations are a clear strategy for facing these gender issues. They promote the exchange of information, experiences, and resources, while encouraging professional and business collaboration (Freund & Hernandez-Maskivker, Citation2021). Moreover, associations give visibility to female entrepreneurs, helping to create alliances among them, providing support on a local, national, and international level. When women have spaces where they can share their experiences and doubts with others, a more critical perception of reality emerges. Thus, a stronger focus should be placed on cultivating informal institutions to support female entrepreneurs in Barcelona, Spain. This finding is in line with Noguera’s (Citation2012) work examining the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Catalonia. The very first institutional step in this direction is the recently inaugurated Espai Lidera, a space created by the Barcelona town hall for women entrepreneurs (Barcelona Activa, Citation2022).

The Spanish entrepreneurial ecosystem is socially conditioned and reinforces gender inequities excluding women entrepreneurs from succeeding which as identified in the final category- Entrepreneuring Motherhood Penalty. This third category depicted the penalty women entrepreneurs face. Indeed, choosing motherhood encourages us to think deeply about Chodorow’s (Citation1978) work. Each generation plays a role in reproducing its society and given that women are universally responsible for early childcare, sex roles are experienced and reoccur (Chodorow, Citation1978). As such, we are curious how gender roles may be challenged to support women tourism entrepreneurs. Shared parental leaves and governmental subsidies for childcare may support women to feel they can afford to work, tax subsidies for new entrepreneurs, mentorship programs, and access to training, and educational opportunities for women may be a start and help foster future female role models which the ecosystem would clearly benefit from. Adopting such supports may begin to repair some of the damages created and foster a more caring and equitable entrepreneurial ecosystem progressing SDG 5 and SDG 8.

When analyzing our data dissonances and contradictions emerge between theory and praxis. For example, despite the Spanish government making initial efforts to achieve greater gender equality through entrepreneurial policy, critique is needed. Although policy wise, they often transmit positive discourses and images promoting gender equality, the reality demonstrates that the measures in place still perpetuate the gender gap, as noted by other scholars such as Khoo-Lattimore et al. (Citation2019). Our analysis showed that constraints for female entrepreneurs exist in an ecosystem that shows sexist patterns, and this misguided social pattern drives female entrepreneurs to a ‘glass ceiling’ of non-recognition and disrespect in a male represented system. As an example, our data revealed the casual and accepted use of sexist language. In this respect, unconscious bias training including inclusive language modules may serve as useful in the Spanish entrepreneurial ecosystem. The focus of these policies continues to improve gender equality metrics but how do we know that these quantitative indicators are enough to create effective policies directed to tackle the real constraints of female entrepreneurs?

Supported by an ethic of care including, and listening, to the voices of women entrepreneurs will be necessary to ensure women are receiving the supports they need to succeed. Diversity and inclusion are not necessarily synonymous. For example, if venture capitalists funded more female entrepreneurs (enhancing the visibility of women), but the ecosystem still supported the use of sexist language and/or shared parenting supports were not in place, it may appear the ecosystem is more diverse, but it may not be inclusive. Furthermore, for policies to be effective they need to be reinforced. Our analysis as illustrated in above, revealed opportunities to improve existing policies, consider female involvement in crafting policies, and additional policies to support female entrepreneurs.

Critical analyses of discourses that perpetuate structures of gender inequity discrediting female entrepreneurship are necessary. Considering gender equity concerns is particularly important now because gender biases and embedded traditional masculine attitudes affect our understanding of what successful entrepreneurs look like (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2012). It is widely accepted that tourism entrepreneurship empowers women, particularly through the provision of direct jobs and income-generation. This view; however, is simplistic and obeys a masculinist framing (Cole, Citation2018). Income-generation is only one aspect and scholars such as Cole (Citation2018), stress the need to reframe conceptualizations of tourism entrepreneurship for women. Specifically, it is important to understand how women envision entrepreneurship, its opportunities, and limitations. This vision might not necessarily be limited to capitalistic views, currently adopted in tourism entrepreneurship ecosystems.

We believe that the above problems should be tackled using an ethic of care approach, giving voice to everyone, and recognizing inequalities to contribute to a more democratic and inclusive society. It is important that policy actions link diversity with value creation and reinforce the message of recognizing different social groups as a win-win strategy. By using a feminist ethic of care lens, we can appreciate the value of care and relationality as mutually a barrier or ideally a pathway for improved entrepreneurial conditions in Barcelona, Spain. It is interesting to mention that only one of our informants is leading a social startup. Nonetheless, in support of previous scholarly work our informants exhibited concern for the well-being of their communities (Tajeddini et al., Citation2017), which was central in their businesses intending to create community social wealth (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2013) and make a difference to their communities (GEM, 2020). As such, their relationship to their community was strong and played a vital role in their professional endeavors. Furthermore, their care for their communities demonstrated the impacts they were keen to generate beyond economic capital. While a caring orientation among women was noted among many of our informants, it was sometimes used in opposition to success, as male entrepreneurs were capable of hunting and securing revenue which seemed to secure their success.

Conclusions

The aim of our study was to examine the culture of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona and determine supports which may assist women tourism. Our findings draw attention to gender biases that in our view, could be improved by employing an ethic of care, specifically acting in relation to one another and committing to inclusion and diversification. It is 2022, and although equity advancements have been made, our findings illustrate that a gender division exists based on social conditioning, and the motherhood penalty which serve as barriers to female participation in the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona. Our study compliments previous works noting the low representation of female entrepreneurs and its potential for negative impacts in relation to our understandings of equity and social justice (Chambers et al., Citation2017; Jamal & Higham, Citation2021; Moreno-Alarcón, Citation2020). Our findings reinforce Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020b) claim that entrepreneurship is not gender neutral in the tourism industry.

While varied efforts by tourism stakeholders are currently underway in Spain to progress the SDGs, there is still a long road ahead with a rather slow speed of change. Clearly, advancing SDG 5, Gender Equality and SDG 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth, will require work from all genders in the entrepreneurial ecosystem in a more strategic way with a clear commitment to inclusivity. Furthermore, we note that the current pandemic landscape has exacerbated challenges for women and scholars alert that the post-COVID phase places even greater challenges (Jamal & Higham, Citation2021).

Our findings contribute to scarce attention to the field of gender studies in Spain and to the urgent need to translate the awareness of gender inequity into practical solutions (Chambers et al., Citation2017; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2018; Khoo-Lattimore et al., Citation2019; Segovia-Pérez et al., Citation2019). This situation of gender biases unfortunately is not only present in Spain or solely affects the tourism and hospitality sector but is also similar in other countries and sectors (Hutchings et al., Citation2020). Our data revealed implicit biases that support the performance and success of male entrepreneurs in securing capital, evidence of social conditioning and informal factors such as the lack of female role models and the lack of a strong networking systems. Furthermore, our analysis reconfirmed the motherhood penalty is real. Our data clearly showed a difference in the value-led orientation of informants and what seemed like different expectations of genders. Specifically, the data illustrated women entrepreneurs are pressed more in areas they are perceived to be weaker. We position ourselves with Cole (Citation2018) who stresses the need to reframe conceptualizations of tourism entrepreneurship for women. In this way, the findings of our study contribute to the limited tourism scholarship adopting feminist perspectives, in this case adding to the scholarly debate on feminist ethic of care (Higgins-Desbiolles & Monga, Citation2021; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014; Pritchard, Citation2018, Carnicelli & Boluk, Citation2021).

If we aim to provide inclusive tourism models stakeholder collaboration is crucial. Sustainable development progress can only be attained by means of strong partnerships and cooperation, at the local, regional, national, and global level, placing people and the planet at the center (UN, 2022). With this goal in mind tourism and hospitality must commit to a range of tourism’s entrepreneurial stakeholders. Firstly, from a public administration perspective, there is a strong focus on attaining diversity; however, diversity is mostly understood by policymakers in absolute numbers. It is usually measured through numerical ratios of gender equality (for example, 40/60). Success in this sense is attained by “increasing the number of female entrepreneurs.” While this is an initial step, we must go one step further. Diversity does not warrant inclusivity; thus, it is fundamental to listen to the voices of female entrepreneurs and females in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Insufficient efforts have been made in this sense in Barcelona.

Secondly, in our view, tourism universities should work closely with female entrepreneurs to increase the visibility of women as role models. Most students of tourism and hospitality in Barcelona are women, yet female role models are scarce. Most of the higher educational institutions in Barcelona are fostering entrepreneurship, though they are replicating gendered discourses. Training related to unconscious biases, mentorship, and support with funding access should be offered. Not only to young entrepreneurs but to the ecosystem. Higher education has a privileged position as a hub, interconnecting different stakeholders. Transformational entrepreneurs, business angels, venture capitalists, accelerators with inclusive values are greatly needed in the tourism and hospitality industry to reinforce change. Higher Education should be committed to advancing a just society by being the catalysts for positive social change themselves and to help enable others to achieve societal impact.

We are aware that this study is not without limitations, and our experience conducting it provides us with insights regarding future lines of research. This study is based in Barcelona, further research is needed to fully understand the entrepreneurial ecosystems in other locations, therefore we call for more qualitative research in different regional settings in Spain and abroad. Further research could explore the perspectives of corporate females who considered entrepreneurship but did not pursue entrepreneurship to improve understandings of constraints. Furthermore, our study was conducted before the onset of COVID-19, as such it would be interesting to explore how the ecosystem has been shaped by the pandemic attending to recent literature claiming that the pandemic has exacerbated gender inequality and a lack of female empowerment (Moreno-Alarcón, Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniela Freund

Daniela Freund is lecturer and researcher at Ramon Llull University in Barcelona, Spain. She holds a PhD in Education Sciences and is a member of the research group in tourism, hospitality and mobilities. With more than 20 years expertise in tourism and hospitality-related education, she specializes in educational and business innovation. Her research interests include gender diversity, inclusion, and educational innovation.

Itziar Ramírez García

Itziar Ramírez García has more than 12 years of experience in the Hospitality Industry, particularly in the field of human resource management. She holds a PhD in Organisational Psychology, and her main field of research is organizational values. Currently she is a lecturer and researcher at Ramon Llull University. Her past experiences include working with multicultural teams in Barcelona, Hong Kong and London and has participated in challenging projects such as the opening of the tallest hotel in Europe, the Shangri-La Hotel at the Shard. She is member of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development and works as an external consultant for a luxury hospitality recruitment company.

Karla A. Boluk

Karla A. Boluk is an Associate Professor in the Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies at the University of Waterloo. Guided by a social justice paradigm and feminist ethic of care lens the broad goals of her research program are to examine ways tourism enhances the well-being and quality of life of those involved in or affected by tourism. Her work has mutually challenged and critiqued the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as considered the global framework to better understand how tourism may progress sustainability efforts.

Mireia Canut-Cascalló

Mireia Canut-Cascalló is a Tourism and Hospitality Management graduate from Ramon Llull University. She holds an MSc in Global Governance and Ethics at University College of London. Her research interests include the application of gender studies and the empowerment of minorities to tourism and international organisations.

María López-Planas

María López-Planas is a Tourism and Hospitality Management graduate from Ramon Llull University. She is currently studying a Bachelor Degree in Business Administration at Universitat Oberta Catalunya. Her research interests include the application of gender studies and the empowerment of minorities to tourism and international organisations.

References

- Abouzahr, K., Brooks Taplett, F., Krentz, M., & Harthorne, J. (2018). Why women-owned startups are a better bet. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/why-women-owned-startups-are-better-bet.aspx?linkId=52657137&redir=true.

- Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2012). Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism, and entrepreneurship: Advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization, 19(5), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508412448695

- Alesina, A., & Glaeser, E. (2006). Why are welfare states in the US and Europe so different? What do we learn? La Documentation française. Horizons Stratégiques, n° 2(2), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.3917/hori.002.0051

- Alonso-Almeida, M. d M. (2013). Influence of gender and financing on tourist company growth. Journal of Business Research, 66(5), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.09.025

- Barcelona Activa. (2022). https://emprenedoria.barcelonactiva.cat/en/espai-lidera.

- Benschop, Y. (2009). The micro-politics of gendering in networking. Gender, Work & Organization, 16(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00438.x

- Block, J. H., Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2018). New players in entrepreneurial finance and why they are there. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9826-6

- Boluk, K., Cavaliere, C., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in Tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Boluk, K., & Panse, G. (2022). Recognizing the regenerative impacts of Canadian women tourism entrepreneurs through a feminist ethic of care lens. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(3), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-11-2021-0253

- Brush, C., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., & Welter, F. (2019). A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1187-018-9992-9

- Bullough, A., Guelich, U., Manolova, T. S., & Schjoedt, L. (2022). Women’s entrepreneurship and culture: Gender role expectations and identities, societal culture, and the entrepreneurial environment. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 985–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00429-6

- Carnicelli, S., & Boluk, K. (2021). A theory of care to socialise tourism. In F. Higgins-Desbiolles, A. Doering, & B. Bigby (Eds.), Socialising tourism. Routledge, 58–71.

- Carrasco, C., Borderías, C., & Torns, T. (Eds.). (2011). El trabajo de cuidados: Historia, teoría y políticas. Los libros de la Catarata.

- CCOO Servicios. (2019). Análisis de la actividad del turismo en España. https://www.ccoo-servicios.es/archivos/turismo/2020-02-04-Analisis-TURISMO-en-Espanya–2019.pdf.

- Chamber of Commerce of Spain. (2022). Ayudas para Mujeres Emprendedoras - Programa PAEM. https://empresarias.camara.es/.

- Chambers, D., Munar, A. M., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Biran, A. (2017). Interrogating gender and the tourism academy through epistemological lens. Anatolia, 28(4), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2017.1370775

- Charmaz, K. (2011). A constructivist grounded theory analysis of losing and regaining a valued self. In F. J. Wertz, K. Charmaz, L. M. McMullen, R. Josselson, R. Anderson, & E. McSpadden (Eds.), Five ways of doing qualitative analysis. The Guilford Press, 165–204.

- Chatzidakis, A., Hakim, J., Littler, J., Rottenberg, C., & Segal, L. (2021). The care manifesto. The politics of interdependence. VERSO.

- Chodorow, N. (1978). The reproduction of mothering. University of California Press.

- Cole, S. (2018). Gender equality and tourism beyond empowerment. CABI.

- Colombelli, A., Paolucci, E., & Ughetto, E. (2019). Hierarchical and relational governance and the life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9957-4

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Equality in Tourism. (2018). Report: Sun, sand and ceilings: Women in the boardroom in tourism and hospitality boardrooms. https://equalityintourism.org/sun-sand-and-ceilings-women-in-tourism-and-hospitality-boardrooms/.

- European Commission. (2018). 2018 Report on equality between women and men in the EU. https://doi.org/10.2838/21655

- European Commission. (2021). Supporting entrepreneurship commission’s actions on entrepreneurship education. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/supporting-entrepreneurship/support/education/commission-actions_en.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2017). Economic benefits of gender equality in the European Union. http://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/sectoral-areas/economic-and-financial-affairs/economic-benefits-gender-equality.

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020b, September). Gender, tourism & entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102980

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., De Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020a). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: A gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, pp, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Segovia-Perez, M., Flecha Barrio, M. D., & Palomo, J. (2018). Women in decision-making positions in tourism high-technology companies: Board of directors. In XII International Conference of Tourism and Information and Communications Technologies, pp. 117–130.

- Freund, D., & Hernandez-Maskivker, G. (2021, April). Women managers in tourism: Associations for building a sustainable world. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100820

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). (2022). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021/2022 global report: Opportunity amid disruption. GEM. https://gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=50900.

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2020). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2019/2020 Global Report. GEM. https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2019-2020-global-report.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Harvard University Press.

- Government of Spain. High Commissioner for Spain Nation of Entrepreneurship. (2021). Spain nation of entrepreneurship strategic plan. https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/presidente/actividades/Documents/2021/110221-Estrategia_Espana_Nacion_Emprendedora.pdf.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Monga, M. (2021). Transformative change through events business: A feminist ethic of care analysis of building the purpose economy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11–12), 1989–2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1856857

- Hutchings, K., Moyle, C., Chai, A., Garofano, N., & Moore, S. (2020, January). Segregation of women in tourism employment in the APEC region. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100655

- Jamal, T., & Camargo, B. A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice, and an ethic of care: Toward the just destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

- Jamal, T., & Higham, J. (2021). Justice and ethics: Towards a new platform for tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2–3), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1835933

- Khoo-Lattimore, C., Yang, E. C. L., & Je, J. S. (2019). Assessing gender representation in knowledge production: A critical analysis of UNWTO’s planned events. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 920–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1566347

- Kimbu, A. N., De Jong, A., Issahaku, A., Ribeiro, M. A., Afenyo-Agbe, E., Adeola, O., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (2021). Recontextualising gender in entrepreneurial leadership. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103176

- Kimbu, A. N., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2016). Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

- Klyver, K., & Grant, S. (2010). Gender differences in entrepreneurial networking and participation. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 2(3), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261011079215

- Kwapisz, A., & Hechavarría, D. M. (2018). Women don’t ask: An investigation of start-up financing and gender. Venture Capital, 20(2), 159–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2017.1345119

- Law 03/2007, of March 20, 2007, on gender equality for men and women. (2007). https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2007-6115.

- Law 06/2019, of March 1, 2019, on measures to support equal employment opportunities. (2019). https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2019/03/01/.

- Mastercard. (2019). Mastercard index of women entrepreneurs 2019. https://newsroom.mastercard.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Mastercard-Index-of-Women-Entrepreneurs-2019.pdf.

- Mathews, H., & Nunn, M. (2020). Women on the move can we achieve gender equality by 2030? In. H. Kharas, J. W. McArthur, & I. Ohno (Eds.), Leave no one behind time for specifics on the sustainable development goals. Brookings Institute, 23-40.

- Moreno-Alarcón, D. (2020). El impacto de la Covid-19 en el turismo rural. Turismo Estudos & Práticas (UERN), 9. Seminário Virtual Perspectivas Críticas sobre o Trabalho no Turism, 1–7.

- Muñoz, L. G., & Pérez, P. F. (2007). Female entrepreneurship in Spain during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Business History Review, 81(3), 495–515. https://doi.org/10.2307/25097379

- Noddings, N. (2012). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), 771–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.745047

- Noguera, M. (2012). Female entrepreneurship in Catalonia: An institutional approach [PhD thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/116322#page=9.

- Pritchard, A. (2018). Predicting the next decade of tourism gender research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 144–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.014

- Robinson, F. (2006). Beyond labour rights. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 8(3), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616740600792871

- Robinson, F. (2018). Care ethics and international relations: Challenging rationalism in global ethics. International Journal of Care and Caring, 2(3), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1332/239788218X15321005364570

- Segovia-Pérez, M., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (Eds.). (2014). Mujer y alta dirección en el sector Editorial Síntesis.

- Segovia-Pérez, M., Figueroa-Domecq, C., Fuentes-Moraleda, L., & Muñoz-Mazón, A. (2019). Incorporating a gender approach in the hospitality industry: Female executives’ perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76(Part A), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.05.008

- Stroh, L. K., & Reilly, A. H. (2012). Gender and careers: Present experiences and emerging trends. In N. P. Gray (Ed.), Handbook of gender & work (pp. 307–324). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231365.n16

- Sultana, A., & Ravanera, C. (2020). A feminist economic recovery plan for Canada: Making the economy work for everyone. The Institute for Gender and the Economy (GATE) and YWCA Canada. www.feministrecovery.ca

- Tajeddini, K., Walle, A. H., & Denisa, M. (2017). Enterprising women, tourism, and development: The case of Bali. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 18(2), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2016.1264906

- Tarr, T. (2019). How women entrepreneurs are breaking free of the pay gap (and the best cities to be in). Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tanyatarr/2019/11/19/how-women-entrepreneurs-are-breaking-free-of-the-pay-gap-and-the-best-cities-to-be-in/#465732e35f44.

- Tronto, J. C. (1993). Moral boundaries, a political argument for an ethic of care. New York University Press.

- United Nations SDGs. (2022). Sustainable development goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- UNWTO. (2019). International Tourism Highlights, 2019 Edition. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284421152

- Verheul, I., & Thurik, R. (2001). Start-up capital: Does gender matter? Small Business Economics, 16(4), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011178629240

- Vujko, A., Tretiakova, T. N., Petrović, M. D., Radovanović, M., Gajić, T., & Vuković, D. (2019). Women’s empowerment through self-employment in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 76, 328–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.09.004

- Zhang, C. X., Kimbu, A. N., Lin, P., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2020). Guanxi influences on women intrapreneurship. Tourism Management, 81, 104137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104137