Abstract

Ours is an era of crises. Having weathered the recent COVID-19 global pandemic, we are confronted with numerous interconnected crises that challenge the global community. These crises bring with them issues of justice and injustice, as different populations are differentially impacted. Certainly, we have seen obstacles to success in Global North-South inequalities, power differentials and structural injustices. It is essential to consider how we may collaborate together to manage and transition through these multitude of problems. This is the context in which contemporary tourism must operate and play its role in seeking resolutions. This introduction to the Special Issue on “Tourism Global Crises and Justice”, critiques these contemporary issues and considers how we might transition tourism for more just, sustainable and equitable futures. Drawing on contributions to this Special Issue, in this article we bring together a discussion of pertinent themes that consider just transformations, issues of climate justice, diverse worldviews and knowledges, possibilities for solidarity through tourism, and concerns with power and decolonisation. In doing so, we propose a transdisciplinary analytical framework that can inform more just and equitable practices in tourism.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic gave us time to pause and reflect on the fundamental underpinnings of tourism as a phenomenon. During this extraordinary moment of managing a global pandemic, borders were shut, tourism halted, lockdowns ensued for various lengths of time and economies ground to a temporary standstill. It was immediately apparent just how interdependent the sector is, and certainly its vulnerability as a result. While crisis, risk and resilience studies in tourism are not new (e.g. Mert, Citation2016; Prayag, Citation2018; Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019), the scale and pervasiveness of COVID-19 forced more profound reflection, particularly as other crises and disasters emerged concurrently.

There are diverse voices from various positionalities of expertise alerting us to a time of potential existential crisis and our need to act. Arguably, we are arriving to a time with a critical difference, the potential for these crises and injustices to bring us to “collapse”. However, the experiences of crises and even collapse will not be experienced in universally the same way. As we will show with our particular focus on (in)justices for poor, marginalised and oppressed groups, crises are usually far worse and capacities to adapt more limited and are therefore worthy of greater attention. We focus particularly on the Global South as the home of the majority of the world’s population but also in our attunement to powerplays and failures to act in true solidarity; “the use of the phrase Global South marks a shift from a central focus on development or cultural difference toward an emphasis on geopolitical relations of power” (Dado & Connell, Citation2012, p. 12).

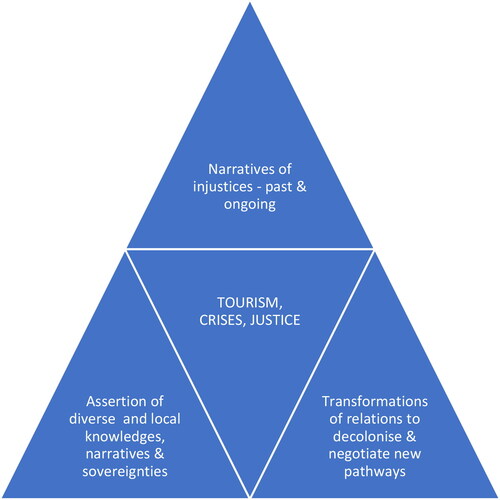

In this introduction to our Special Issue, we examine the multiple contemporary crises human societies face and the ways they impact on, intersect with, and shape tourism futures. The position we present here is that these crises share a common theme; at their centre lie issues of justice and injustice for humans, more-than-human kin and whole ecologies. Together with the articles that comprise this volume, we engage concepts, cases and dilemmas to better know where we are and where we might go. We offer an extension to these discussions through a preliminary framework for tourism, crises and justices (see ).

Figure 1. Framework for addressing crises and injustices in tourism towards engaged and transformative outcomes.

Building a transdisciplinary analytical framework can help inform more just and equitable practices in tourism, leveraging the cutting edge thinking from other disciplines (e.g. environmental justice, decolonial studies and peace studies) that we have drawn into our discussion to offer new insights for managing tourism in an era of crises by moving beyond managerial, technocratic and reformist approaches. This framework resonates with the papers submitted to the special issue, and collectively (this introduction and the Special Issue papers) we hope that this may prove helpful in guiding tourism scholarship and practice to consider and advocate for more fair and sustainable futures. The sections that follow build insights that support the framework, detailing the nature of impending tourism crises, the distinct claims of ecological and environmental justice and the climate justice imperative raised by climate change challenges. Narratives and experiences of injustices bring current tourism practices into question and expose the need for engagement with diverse worldviews and knowledges and transformations in relations of tourism for solidarity and decolonisation. We bring these diverse threads together to build a solid triangulated framework for critiquing contemporary tourism and reshaping it in more equitable and sustainable ways. In this era of “polycrisis” (Tooze, Citation2022), we need renewed thinking that grapples with the complexities of injustices in order to avoid siloed thinking and inspire the collaborations that are vital for just, sustainable and equitable solutions.

Tourism and justice in the face of global crises

“There’s no tourism on a dead planet”- adaptation of climate activist mantra

As we write this piece, communities in the north, south, east and west are facing the devastating impacts of crises such as wars, sanctions, refugee movements, pandemics, biodiversity loss, and climate change; many of these are the direct or indirect products of capitalism and colonialism. COVID-19 was more than just a health crisis, but a crisis that has affected, and continues to affect, the most vulnerable individuals among us, including tourism, hospitality, and gig workers whose livelihoods disappeared altogether as travel and leisure halted. In other contexts, such as hospitality workers in the healthcare system, workers found themselves bearing the brunt of the crisis despite receiving relatively lower pay and benefits in many capitalistic economies.

Concurrently, biodiversity and ongoing sixth mass species extinction is threatening the well-being of many, as indicated in the recent Living Planet Report 2022 which reported: “[…] an average decline of 69% in species populations since 1970” (WWF, Citation2022). Biodiversity loss will have catastrophic impacts on human lives and significantly affect many destinations and tourist experiences. Similarly, the climate change crisis disproportionately affects the environment and livelihoods of many low-income countries and poor people in high-income countries, violating their human rights and access to social justice (Levy & Patz, Citation2015; Venn, Citation2019). However, not too far in the future, no one will be immune from the devastating impacts of socio-ecological crises when for example rising temperatures fuel other crises such as “environmental degradation, natural disasters, weather extremes, food and water insecurity, economic disruption, conflict, and terrorism” (UN, Citation2020).

The socio-ecological crises of the present time have made it clear that failure to prevent human-induced mass extinction and climate change will affect the wellbeing of us all, but most particularly those with little “voice”, including youth, future generations and nonhuman animals. The contemporary (anthropocentric) tourism system has long contributed to the environmental crises with both negative social and ecological consequences. As we well know, tourism is both vulnerable to, and a contributor to, such crises. Therefore, one key issue is to identify the human impact of tourism’s role in climate ecological and environmental justice (Rastegar, Citation2022). Yet the meaning and importance of these distinct terms are not widely understood, and this has significant negative impacts on our ability to both prevent and respond to these multitude of crises.

These global crises suggest we must consider pathways to tourism transition. But how do we cultivate a transition mindset in tourism and what are the short-term and long-term measures that are essential to reach our goals for just, sustainable, and equitable outcomes remain disputed (see, for instance, debates on overtourism hotspot Venice in Friel, Citation2021; Standish, Citation2023). Since the experience of the global pandemic, it has been frequently claimed that tourism cannot and must not return to “business as usual” (e.g. Becken, Citation2021; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2022; UNWTO, Citation2022). However, the resumption of travel certainly casts doubt on these assessments, as consumers embrace reopened travel opportunities with a fervour; meanwhile businesses capitalise on this demand to recoup pandemic losses. We are left to wonder if the notion of a tourism transition was over before it even started. Or are tourism transitions a contested space that requires greater unpacking and critical analysis to strengthen our understanding?

Ecological justice and environmental justice: justice for human and biological diversity

As we explore the interstices of crises, justice and tourism, we must wrestle with the tensions in meeting human needs while also tending to ecological needs and the needs of the more-than-human in our shared spaces, including spaces of tourism. Additionally, humans are not a homogenous category, and there are myriad inequalities, inequities and injustices that must be recognised and addressed. In these discussions, it is vital to note the distinctions between the terms “environmental justice” and “ecological justice”, despite the fact they would appear to concern similar things. Low and Gleeson explained the former addresses “the struggle for… justice of the distribution of environments among peoples” while the latter addresses “[…] justice in the relationship between humans and the rest of the natural world” (Low & Gleeson, Citation1998, p. 2).

The injustices of environmental racism catalysed environmental justice movements and has resulted in transformed policies, including in the US state of Massachusetts that created an Environmental Justice Policy in 2002 (see Agyeman & Evans, Citation2003, p. 36). However, this stream of environmentalism has been criticised for focusing more on social justice among humans, with less emphasis on the intrinsic value of the wilderness or non-human animals. Environmental justice advocates have countered that the fight against negative environmental impacts contributes to the overall efforts for environmental conservation and sustainability (Agyeman et al., Citation2002 p. 78). On the other hand, advocates for ecological justice argue that non-anthropocentric approaches of justice will be required to give full voice to the range of interests of nonhumans and futurity of all life (e.g., Treves et al., Citation2019). The environmental movements that solely focus on protection of the natural environment informed by experts or western approaches can however result in injustice when ignoring the rights, values, and knowledges of local and Indigenous communities. Similarly, many emerging socio-environmental conflicts are due to either ecological justice actions undermining communities’ interests or promoting anthropocentric environmental justice neglecting the interests of nonhuman beings. Such development strategies are not sustainable nor just.

Combating the devastating impacts of global crises such as biodiversity loss and climate change requires addressing both environmental conservation and sociocultural wellbeing. Therefore, addressing the tension between justice among humans (social justice) and environmental protection (ecological justice) requires a collaborative and inclusive approach. Examples can be seen when the formulation of Indigenous Environmental Justice based on Indigenous philosophy, ontology, and epistemologies is suggested to address both ecological crisis and injustices being experienced by communities (McGregor et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Higgins-Desbiolles (Citation2020, p. 618) advocates for “socialising tourism” by placing “tourism in the context of the society in which it occurs and to harness it for the empowerment and wellbeing of local communities” to promote social and ecological justice. This is to ensure that any tourism development is accountable to local social and ecological limits as it occurs in the local contexts that include both human and nonhuman dimensions. Identifying a social-natural sciences divide in tourism, Rastegar (Citation2022, p. 117) proposed “a multispecies justice turn by considering a mixed moral community with human-nonhuman interaction in shared ecological, social, and political spaces”.

Therefore, addressing the complex issues of justice for humans and nonhumans is essential. These efforts require interdisciplinary research involving both natural and social sciences. However, such a task requires addressing some practical challenges and barriers. For example, overcoming the communication barriers across multiple disciplines and sectors requires developing a common language, facilitating engagement, and embracing diversity in a supportive environment that values interdisciplinary research. In our considerations of tourism, crises and justice, we suggest that understanding the requirements for environmental justice, ecological justice, social sustainability and fulfilling the needs of communities are complex and interconnected. Attaining these “wisdoms” and building different, transformed approaches will be vital in facing the enormous challenges that climate change presents.

The imperative for climate justice in a climate change world

Global climate change presents one of the most pressing challenges of our time and is posing grave threats for every nation, community and sector including tourism. Devastating climate change induced impacts are already evident from recent bush fires, floods, sea level rise, extreme weather and drought threatening the lives and livelihoods of many groups, particularly marginalised populations including women, children, people living with disabilities, those on low-incomes, those suffering discrimination and Indigenous groups both in the Global North and Global South. “Climate justice is a concept that views climate change and efforts to combat it as having ethical implications and considers how these relate to wider justice concerns” (Robinson & Shine, Citation2018, p. 564). Distributional inequality of climate change risk and responsibilities has already led to a “double inequality” (Barrett, Citation2013) affecting the social wellbeing and health of many marginalised groups. While some have highlighted the climate injustice ingrained in North-South relations (Okereke & Coventry, Citation2016), immigrants, people of colour or low-income groups in the Global North are also under considerable pressure from the increasing costs of climate change-driven impacts such as higher energy bills, costly insurance and infrastructure needed to protect their properties and lives (Heffron, Citation2022; Porter et al., Citation2020).

Similarly, the urgency to scale up climate actions in the tourism domain by embracing a low carbon pathway as identified in the Glasgow Declaration (UNWTO, Citation2021) is in response to the dual realisation of both vulnerability and the contribution of tourism to climate change. However, a critical question to pose is how the transition to a post carbon economy will address social inequalities or tensions that emerge in the process? Or even most importantly, what strategies are in place to avoid harmful actions affecting those who already suffer from climate change impacts? Despite the significant growth of climate change and tourism scholarship over the past 30 years, this work has “failed to prepare the sector for the net-zero transition and climate disruption that will transform tourism over the next three decades” (Scott & Gössling, Citation2022, p. 1). Scott & Gössling argue this is the preeminent challenge to understand how climate change and the subsequent sustainability transition will transform tourism over the coming decades; this is most critical for tourism-dependent communities in the Global South.

It is difficult to sustain hope for the radical change needed when the same institutions and self-interested political and business players are commonly allowed to set policies and strategies, such as adaptation and mitigation, to address climate change despite being the very creators of the problems. As a result, the response toolkit to climate change prioritises technological solutions and socio-technical processes (some of which are not yet invented or proven such as carbon capture and storage (see Oquist, Citation2022)) while failing to give due attention to the roots of the crises in our extractive and materialistic socioeconomic systems. The impacts of such narrowly framed transitions are already evident in job losses, population dis/re-locations, rising poverty and lack of funding for local public services such as education, public health and transportation (McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018; Wang & Lo, Citation2021) in countries such as Bangladesh (Carrico et al., Citation2020), China (Lo, Citation2021) and Australia (Evans & Phelan, Citation2016).

Additionally, the drive for clean energy technologies, such as solar panels, wind plants and electric cars, brings global social and environmental impacts, with research indicating how such rapid technological change in the Global North has shifted social and environmental problems to the countries of the Global South. Examples can be seen when the increasing demand for minerals and mining in the Global South to provide resources to build these solar panels and electric cars has increased the risk of soil, air and water pollutions, slavery, child labour and sexual abuse (Sovacool, Citation2021), human rights violations (Marín & Goya, Citation2021) and even armed conflicts (Church & Crawford, Citation2020).

Considering the factor of human development in climate actions and transition will be vital. However, there is no country that guarantees climate justice for its people (Furlan & Mariano, Citation2021). Therefore, the sustainability transition efforts to move to a net zero society must focus more effectively on social and human dimensions (Rastegar & Ruhanen, Citation2023), particularly when acceptability and adaptation of new policies and practices requires individuals’ willingness to change (Martiskainen & Sovacool, Citation2021). Agyeman et al.’s conceptualisation of “just sustainabilities” is useful guidance in such efforts, which underscores: “The need to ensure a better quality of life for all, now and into the future, in a just and equitable manner, whilst living within the limits of supporting ecosystems” (2003, p. 5).

Identifying climate change as a social and ecological justice issue, a just sustainability transition in tourism research, policy, and practice requires us to “move away from ethnocentrism or the domination of political and economic elite by including the voice of coastal communities, marginalised groups and their traditional knowledge” (Rastegar, Citation2022, p. 119). Therefore, transitions reaffirming the interests, power and knowledges of privileged elites will not be just or sustainable. Privileged groups are usually more protected and might be less supportive of environmental regulations threatening their advantageous livelihoods. Additionally, such groups can employ new forms of settler- colonial practices by taking over and occupying more protected homes and neighbourhoods while pushing out disadvantaged lower income groups. Viewed from a more macro perspective, the North’s response to the climate crisis very much looks like militarisation, as walls, border fences and armed units try to repel those that flee impacted communities in the Global South.

To address these difficult issues, we may need more radical responses, and suggestions have included, degrowth strategies, ending capitalism, building alternative economic models more focused on the public good (see EuroNews, Citation2023; Hickel, Citation2021) and more just forms of global order with greater voice and power afforded to the Global South (see Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2022). Debates and discussions on degrowth have featured in tourism academia recently and these contest the need for more radical possibilities to better align human needs with planetary boundaries (e.g., Butcher, Citation2021; Higgins-Desbiolles et al., Citation2019; Higgins-Desbiolles & Everingham, Citation2022). Such approaches are under consideration because they may offer greater scope for transformation to address persisting injustice and inequalities.

Arguably this situation requires tourism actors to rethink, redefine and reorient tourism (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., Citation2019). The transformational opportunities may facilitate the long-heralded responsible, ethical and sustainable transition in tourism. This will not work without tourism actors and decision makers fully and meaningfully adopting justice principles and sustainability values (Rastegar & Ruhanen, Citation2022) that respect the rights, interests and social needs of vulnerable groups and local communities (Boluk et al., Citation2019). Therefore, decolonising or de-centring tourism’s transition will be necessary by identifying power relations, alternative worldviews, and social realities.

Tourism transformation for a more just and sustainable future

As we have been explaining here, ours is an era of crises. While the COVID-19 global pandemic, for a period in time, upended the world as we knew it, the global crisis caused by climate change gathers even greater attention. We will not be able to look back on climate change as a moment in time as the impacts and effects will be pervasive, constant and altering every sphere of our lives. The climate crisis also portends a multitude of other crises associated with it including conflict, financial recession, resource scarcity, growing authoritarianism and more. Despite these tangibly impactful crises, it is important to also be attentive to cultural perspectives and worldviews on these events and how these may shape how we attend to these many crises and the solutions we may countenance. Val Plumwood (Citation2002) observed, no culture that has set “in motion massive processes of biospheric degradation which it has normalised, and which it cannot respond to or correct can hope to survive for very long” (p. 1). Indigenous Potawatami philosopher and scholar Kyle Whyte noted “[…] the hardships many non‐Indigenous people dread most of the climate crisis are ones that Indigenous peoples have endured already due to different forms of colonialism: ecosystem collapse, species loss, economic crash, drastic relocation, and cultural disintegration” (Whyte, Citation2018, p. 226). Such critiques invite us to step outside the taken-for-granted views and perspectives many of us have held and see the root causes of current crises and injustices. Following this path, however, requires transitional steps to rethink, redefine and reorient tourism futures.

Recognising “worlds and knowledges otherwise” in tourism justice

It is important to recognise that a good deal of the contributions to recent discussion of justice in tourism emerge from the Western tradition. In this era of demands for greater engagement with diversity and inclusion and in the heat of multiple crises, opening up to other ways of understanding is imperative. As Watene (Citation2016) noted, there has been very little engagement with non-Western philosophical traditions, and especially Indigenous ones, in common discussions of justice and ethics. As Arturo Escobar explained, we need recognition of the need for “worlds and knowledges otherwise,” that is, for “worlds that are more just and sustainable and, at the same time, worlds that are defined through principles other than those of Eurocentric modernity” (2004, p. 220). For example, scholars argue how understanding gender-leisure nexus in the Global South requires inclusion of women’s voices, stories, diverse cultural perspectives, and justice narratives (e.g., Zarezadeh & Rastegar, Citation2023). This approach of “worlds and knowledges otherwise” invites us to imagine justice in tourism much more widely than has yet occurred. It is an essential agenda that ranges far beyond conventional equality, diversity and inclusion programmes which largely fail to engage with issues of justice. The promise and richness of such diverse worlds of knowledge are many, as seen for example in recent work on “embodied plantation ecologies” (Davis et al., Citation2019) and ecofeminism (Power, Citation2016).

Western approaches have dominated for far too long, through a trifecta of forces described by development theorists such as Escobar (Citation2004) as coloniality, development and modernisation. This is a homogenising, universalist agenda that designates Global South communities as “underdeveloped” and purports to set them on a rigid development trajectory whose rules are set by Western institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It is operative too in the drive to set tourism as a pathway to development for the developing world and is promoted by institutions such as the UNWTO. Higgins-Desbiolles has critiqued the dependency on tourism that this has fostered that “[…] works against the abilities for the communities of the Global South to achieve just, fair, self-determining and sustainable futures” (2022, p. 7).

The impacts of these dynamics can be described as a form of epistemic injustice as Western approaches are forced on the developing world. Epistemic injustice occurs when a wrong or harm is “done to someone in their capacity as a knower”, and justice is secured by counteracting practices of silencing or devaluing alternative forms of knowing and living that do not conform with assumptions about the “authority” of scientific knowledge (Fricker, Citation2007, p. 1). We can identify cases of epistemic justice in tourism in the projects that ground tourism in Indigenous knowledges and lifeways. Examples can be found in Bhutan’s initial tourism programme based in part on Buddhist philosophy found in the “Gross National Happiness” approach (Schroeder, Citation2018, p. 3) and the “kaupapa tāpoi” framework for Indigenous tourism derived from Māori values and principles offered by Mika and Scheyvens (Citation2022). We can identify epistemic injustices in tourism when tourism undermines the lifeways of local and Indigenous communities, requiring they change to suit tourists and tourism industry interests.

The work in development studies on ‘worlds and knowledges otherwise’ calls us to be more critical in our considerations of tourism justice issues. It spotlights the ways that ‘tourism as modernisation’ discourses and practices compel communities to reject their own knowledges and lifeways in the interest of tapping tourism for development. Escobar and others use the term ‘pluriversality’ as an approach conducive to multiple knowledges and lifeways: “The diversity of mundializacíon is contrasted with the homogeneity of globalisation, aiming at multiple and diverse social orders—in sum, pluriversality” (Escobar, Citation2004, p. 219). Such approaches to tourism counteract the problems of exploitation, domination, homogeneity and inauthenticity that had long been sources of criticism and opposition to tourism developments. Such concepts and ideas are gaining traction in tourism studies (e.g., Chambers & Buzinde, Citation2015; Everingham et al., Citation2021), however further work is needed. For instance, social movements active in and against tourism could be studied through this analytical lens (e.g., Fairbnb, the Global Cruise Activist Network and Network of Southern European Cities against Touristification).

Recognising and protecting “worlds and knowledges otherwise” in tourism offers an important mechanism to ensure diversity, inclusion, justice, and sustainability in tourism as different knowledges are respected and empowered. As we confront multiple crises, epistemic justice approaches help us to access diverse knowledges and innovative approaches that evolve from living in various cultures and places. In contrast, the homogenising and myopic perspectives and approaches derived from Western capital-centric approaches are likely to offer only more of the same.

In this Special Issue, we have a number of contributions that offer insights into tourism from “worlds and knowledges otherwise”. Firstly, Benjamin and Laughter use a lens of critical race theory and a “framework of endarkened storywork” to bring to the fore the concerns and experiences of marginalised individuals and communities in tourism, particularly Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC). Bigby, Hatley and Jim reflect on Indigenous-led “toxic tours” to the superfund site of Tar Creek in Oklahoma and reveal that an Indigenist lens spotlights action for Indigenous resurgence which differs from Western notions of “justice” in the face of ecological and social crises brought on by settler-colonial injustices. Analysing child labour and orphanage tourism, Canosa and Graham reveal the adult-centric discourses of tourism and advocate for “childist” approaches in tourism, moving work away from patronising and alienating protectionism to respectful engagement with child rights and empowerment.

Solidarity in and through tourism for building collaboration

As we consider justice in tourism, we need to consider the bonds of solidarity and how widely its purview extends because solidarity is essential in addressing the multiple crises now faced, particularly climate change. “While ‘justice’ refers to rights and duties (Moralität), the concept of solidarity refers to relations of personal commitment and recognition (Sittlichkeit)” (Ter Meulen, Citation2017, p. 71). The importance of solidarity lies in its relational aspects, particularly its emphasis on cooperation and commonality. Solidarity does not result from a universal human capacity to identify with the needs of others, but instead is a learned “we-ness” that delineates “us” from “others” (Rorty, Citation1989). However, Schwartz argues that we may be moving towards forms of more global solidarity: “The emerging ‘global civil society’ of transnational social movements helps raise the visibility of transnational issues” (Schwartz, Citation2007, p. 143). As the global community confronts crises such as human-induced climate change and global pandemics, the pressures for global solutions through global cooperation and even global order increase.

In such a context, the intercultural and peace-building capacities of tourism may act as a catalyst to greater solidarity. Peace through tourism analyses suggest that tourism may contribute to peace between peoples, communities, and nations. While the intercultural contact theory of tourism has been challenged because tourism is too superficial to induce conflict reduction and peace (e.g., Farmaki, Citation2019), discussions of solidarity through tourism may advance the possibilities. However, for peace through tourism and solidarity through tourism to be effective and have real meaning, justice underpinnings are essential (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., Citation2022).

Discussions of solidarity through tourism were revived with the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. In this context, scholars discuss the need for solidarity tourism action plans (Dolnicar & McCabe, Citation2022) or understanding place solidarity in supporting Ukraine (Josiassen et al., Citation2022 & Josiassen et al., Citation2023). But we are prompted to consider critical questions here at this moment in 2023, as to whether this expression of solidarity is limited to bonds with Ukrainians as newly designated Europeans, while black and brown people have been refused such solidarity in cases where they have sorely needed it (see Lyubchenko, Citation2022). Here we can argue that “rather than accepting the status quo of global order, this “peace with justice” approach (Rees, 2020) requires that we interrogate tourism’s roles and responsibilities in maintaining an unjust global order and act accordingly” (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2022, p. 5). This issue directly links to the Global North and Global South disparities that we have analysed in the previous section concerning how climate change and other crises are experienced and managed.

This is advocacy for a more globalised form of solidarity. Structural injustices derive from unequal power constellations embedded in systemic structures. This perspective presses us to engage with decolonial thinking recognising the colonial, Western roots behind the current global order and economic system, including the tourism industry (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2022). It is also important to understand the complexity and multiple forms of oppression that structural injustices bring. This might be best supported by complex intersectional analyses informed by critical race studies (Crenshaw, Citation1991).

These discussions on justice, solidarity and what is owed to whom are growing more vital as we are compelled to address complex and global level crises such as the pandemic and climate change. Considerations of solidarity move us from cold and disembodied rules and principles of justice to living and connected relations between people for securing wellbeing and thriving (see Country et al., Citation2017). As we confront global crises such as pandemics, climate change, financial upheavals and potentially globalised conflicts, we will need cooperation that bridges “civilisational” divides and addresses the structural injustices that have in fact helped create these very crises. Well-considered solidarity through tourism approaches may indeed serve as a helpful pillar in this work.

In this volume of articles, Burrai, Buda and Stevenson take us to the Leeds, UK where refugees and asylum-seekers are being empowered through opportunities as tour guides to not only represent themselves but also co-build more inclusive and diverse city futures. As xenophobia and anti-immigrant politics is stoked, such programmes embody solidarity being built through tourism. Kalisch and Cole suggest the value of combining a feminist ethic of care, social solidarity economy and human rights to transform tourism towards justice. By way of contrast, Seyfi, Hall, Saarinen and Vo-Tranh interviewed tourism actors in Iran to assess the value of international sanctions on tourism in achieving justice, human rights and sustainability goals and found them to be problematic.

The rights of precarious workers in tourism also feature in the analyses in this Special Issue. Wilson and Dashper present an ethnographic study of high-altitude mountaineering tourism in the Himalaya in which they document the precarity and injustices experienced by workers but also their agency through self-organisation and advocacy. Another ethnographic study is offered by Riordan, Robinson and Hoffstaedter focused on the injustices experienced by migrant food delivery workers in Australia who similarly find that these workers are active agents in transforming their circumstances.

Addressing power asymmetries: decolonisation

To build these bonds of solidarity that are essential for confronting the polycrises we face, decolonisation is essential to dismantle structures of exploitation and extraction. Our recent experiences during the global pandemic illustrate this well. In April 2021 at the height of the global pandemic, the World Health Organization reported that 87% of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines had gone to people in wealthy countries and just 0.2% had gone to people in low-income countries (UN, Citation2021). Harman et al. (Citation2021, p. 1) argued: “This reprehensible imbalance is no accident. High-income countries have used neocolonial negotiating power, global policy leverage and capital to procure enough doses to cover 245% of their citizens while leaving few doses for poorer countries”.

Such gross injustice is the result of continual failure to dismantle the unequal and unfair global infrastructure that has resulted from the failure to complete decolonisation. Higgins-Desbiolles has called for recognition of the “ongoingness of imperialism” arguing: “Tourism development in such a context of unaddressed and unreformed imperialism, manifests in exploitation, abuse, dispossession, commodification and many other sorts of injustices and inequities” (2022, p. 2). This is evident in the safari tourism in East Africa (see Akama, Citation2004), white saviourism in volunteer tourism (Bandyopadhyay, Citation2019) and cultural pollution through tourism seen in Hawai’i in its debasement of Kanaka Maoli (Aikau & Gonzlez, Citation2019).

Our Special Issue contains a number of articles that address power, injustices, decolonisation and resistance. Buzinde and Caterina-Knorr employ a decolonial lens to interrogate the development policies of Rwanda and Kenya in terms of inclusive development criteria and find the limits imposed by legacies of colonialism and the ongoing impacts of neocolonialism in these countries. Yang analyses the alternative tourism niche growing in China known as “qiongyou”, characterised as low-budget travel by some and analysed here as a form of justice tourism in its resistance to being disciplined to commercial tourism regimes. Higgins-Desbiolles, Scheyvens and Bhatia call for “decolonising tourism and development” and offer a case study of the Cambodian Children’s Trust to explain how this non-government organisation evolved from paternalistic, white saviourism to decolonising, collaborative approaches corresponding to Freirian praxis which work to build critical consciousness and capacities together. Bigby, Hatley and Jim discuss toxic tours conducted by LEAD agency in terms of Indigenous-led resurgence, offering insights into an Indigenous perspective on crises, the pursuit of justice and recovery from historical and ongoing settler colonialism.

Continuing these important debates, in this volume, Hunt, Barragán-Paladines, Izurieta & Ordóñez offer a historical study of waves of in-migration to the well know ecological destination of the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Employing sovereignty theory, they show the complexity of navigating justice issues as these human migrants hold varying values and worldviews on ecology, community, recreation and tourism in this location. Paddison and Hall investigate urban spatial injustices in tourism through a case study of York, UK during the pandemic to assess how transforming policymaking can result in fewer negative tourism impacts. Tomassini and Lamond provide a conceptual analysis rethinking the spatial (in)justices of tourism following the spatial turn in the social sciences. Wu, Wu, Li, Wang and Wang focus on small tourism business entrepreneurs in rural China and investigate their “community citizenship behavior for the environment” arguing this greatly influences the sustainable development of rural tourism communities.

Towards a framework of tourism, crises and justices

The discussions in this introductory article allow for the articulation of a preliminary framework for this topic of tourism, crises and justices (see ). Firstly, are narratives of truth-telling that must come to the fore in order to address ongoing injustices in tourism. These may, for example, contradict the discourse of tourism as a pathway to development, the benevolence of international aid programmes promoting tourism or the value of charity found in volunteer tourism. These truths will, in many cases, be confronting. For example, Australian scholar Deborah Bird Rose explained: “Settler societies are brought into being through invasion: death and silence pervade and gird the whole project” (Rose, Citation2004, p. 58). This sheds light on Bigby, Hatley and Jim ‘s article offered in this Special Issue which narrates the use of toxic tours as a vehicle to reveal that this settler colonial project in still playing out in Oklahoma with deadly consequences. Recent developments in the United States to ban the teaching of critical race studies in schools and colleges reveals how essential and contested this facet is for undoing historic and ongoing injustices (Izaguirre, Citation2023).

Secondly truth-telling must be followed by transformative actions towards decolonising and finding new pathways forward. Decolonisation is not peripheral to our concerns with tourism, crises and justice. As Perkins explained: “[…] equity, decolonization, and activism are central to building political institutions to reduce carbon emissions and material throughput in human economies, so that humans can again flourish within reciprocal relationships with the rest of life” (Perkins, Citation2019, p. 184). Tourism analysts and policymakers may want to consider Hickel’s advice that “[…] economic sovereignty and self-reliance [a]re essential to real decolonization” (2021, n.p.). To achieve transformative changes in the face of these crises, we may need some radical tools in our tool kit including climate reparations, reparations for colonialism that can replace dependency on debt and approaches to development where recipients are engaged as partners not beneficiaries (see Higgins-Desbiolles, Scheyvens and Bhatia in this volume).

The third and final pillar to our framework is the assertion of diverse and local knowledges, narratives and sovereignties. The theoretical foundations for this pillar we have explained in the discussion offered in Section 3. The practical application in tourism may be found in the arguments on defining and focusing tourism on the rights, benefits and interests of local communities (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020; Rastegar et al., Citation2021). This theme arises in a number of analyses found in our volume, including in Buzinde and Caterina-Knorr’s call for “locally defined and equitable approaches to development”, Canosa and Graham’s advocacy for listening to children in tourism dialogues and Paddison and Hall’s narrating of York’s community reclaiming its voice in tourism, among numerous others.

is intended to offer a flexible tool to guide future research and practice in tourism. The three facets of diverse knowledges, narratives of injustices and transformed relations open up more conducive spaces to build justice, equity and empowerment in communities engaged with tourism. The order in which they are engaged may vary depending on the specific context. For instance, in places where stories of injustices have been long suppressed, their uncovering may need to be prioritised and given greater attention (such as in the United States). In contrast, in other instances diverse and local knowledges, narratives and sovereignties may remain largely strong and therefore offer a sound foundation for proceeding (such as in Indigenous localities). However, no matter which way these three facets are employed in a process of bringing greater justice to communities in tourism, they collectively effectively link past, present and future together so that injustices, oppressions and marginalisations can be addressed. This, we argue, presents more solid foundations for addressing tourism futures likely to be beset by polycrisis.

Conclusion

In this introduction, we have been conversing about crises and even collapse, laying out extraordinary challenges before us. But it is important to not give in to “doomism” which could sap our energy to act for justice. Our discussion is mindful of Haraway’s caution on crises discourses which she noted “connotes something approaching apocalypse and its mythologies. Urgencies have other temporalities, and these times are ours. These are the times we must think; these are the times of urgencies that need stories” (Haraway, Citation2016, p. 37). Such stories are found within this Special Issue; stories of injustices, resistance, conscientisation, resurgence, sovereignty and care, from Tribal Nations in Oklahoma, to Cambodia, to Rwanda, to China and cities in Europe and Australia. Urgencies press us to act with thought and care and the articles in this Special Issue offer insights by introducing new concepts, revealing important case experiences and spotlighting proactive strategies that highlight the ability to act to transform tourism and direct it to building better futures in the face of all of the challenges that we face. We hope that through the papers in this Special Issue, new perspectives, critiques and contemporary debates are sparked as we collectively address this sustainability crises and the role of tourism within it.

In this introduction, we have built on the work of earlier analysts (e.g. Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Jamal, Citation2019; 2021; Rastagar, 2022) but expanded the conversations and debates by specifically considering the voices and interests of the excluded, less powerful and marginalised. We have offered a framework for addressing crises and injustices in tourism towards engaged and transformative outcomes. This is based on listening to narratives of injustice in tourism, engaging with and respecting diverse and local knowledges and sovereignties and then co-designing responses in tourism policy and practices that support just tourism futures. The pandemic has been a portent of a challenging future for both tourism and society. Transformations towards justice are essential in meeting these difficult times and navigating the many crises we collectively face if we are to have any hopes for success.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Raymond Rastegar

Raymond Rastegar holds a PhD in tourism management and is a lecturer and researcher in Tourism at the UQ Business School, University of Queensland. His scholarly interest and expertise lie in the fields of justice, sustainability transitions and environmental conservation. His recent research has focused on promoting sustainable management practices and building inclusive futures through sustainability transitions at local, national, and global levels. His research delivered new insights into the tourism phenomenon to advocate a more just and sustainable tourism future for humans and nonhumans.

Freya Higgins-Desbiolles

Freya Higgins-Desbiolles is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer, Business Unit, University of South Australia, Adjunct Associate Professor with the Department of Recreation and Leisure, University of Waterloo, Canada and Visiting Professor with the Centre for Research and Innovation in Tourism, Taylor’s University of Malaysia. Her work focuses on social justice, human rights and sustainability issues in tourism, hospitality and events. She has worked with communities, non-governmental organisations and businesses that harness tourism for better futures.

Lisa Ruhanen

Lisa Ruhanen (PhD, GCEd, BBusHons) is a Professor and the Director of Education at University of Queensland Business School. She has been involved in almost 30 academic and consultancy research projects in Australia and overseas. Her research areas include sustainable tourism destination policy and planning, climate change and Indigenous tourism.

References

- Agyeman, J., & Evans, T. (2003). Toward just sustainability in urban communities: Building equity rights with sustainable solutions. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 590(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203256565

- Agyeman, J., Bullard, R. D., & Evans, B. (2002). Exploring the nexus: Bringing together sustainability, environmental justice and equity. Space and Polity, 6(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570220137907

- Aikau, H. K., & Gonzlez, V. V. (2019). Detours: A decolonial guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press.

- Akama, J. (2004). Neocolonialism, dependency and external control of Africa’s tourism industry. In C. M. Hall & H. Tucker (Eds.), Tourism and postcolonialism (pp. 140–152). Routledge.

- Bandyopadhyay, R. (2019). Volunteer tourism and “The White Man’s Burden”: globalization of suffering, white savior complex, religion and modernity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1578361

- Barrett, S. (2013). Local level climate justice? Adaptation finance and vulnerability reduction. Global Environmental Change, 23(6), 1819–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.015

- Becken, S. (2021). Tourism desperately wants a return to the ‘old normal’ but that would be a disaster. The Conversation. Retrieved 17 October 2022, from https://theconversation.com/tourism-desperately-wants-a-return-to-the-old-normal-but-that-would-be-a-disaster-154182.

- Boluk, K., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Butcher, J. (2021). Covid-19, tourism and the advocacy of degrowth. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1953306

- Carrico, A. R., Donato, K. M., Best, K. B., & Gilligan, J. (2020). Extreme weather and marriage among girls and women in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change, 65, 102160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102160

- Chambers, D., & Buzinde, C. (2015). Tourism and decolonisation: Locating research and self. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.12.002

- Church, C., & Crawford, A. (2020). Minerals and the metals for the energy transition: Exploring the conflict implications for mineral-rich, fragile states. In M. Hafner & S. Tagliapietra (Eds.), The geopolitics of the global energy transition (pp. 279–304). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39066-2_12

- Country, B., Wright, S., Lloyd, K., Suchet-Pearson, S., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D., & Tofa, M. (2017). Meaningful tourist transformations with Country at Bawaka, North East Arnhem Land, northern Australia. Tourist Studies, 17(4), 443–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797616682134

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Dado, N., & Connell, R. (2012). The Global South. Contexts, 11(1), 12–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504212436479

- Davis, J., Moulton, A. A., Van Sant, L., & Williams, B. (2019). Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises. Geography Compass, 13(5), e12438. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438

- Dolnicar, S., & McCabe, S. (2022). Solidarity tourism how can tourism help the Ukraine and other war-torn countries? Annals of Tourism Research, 94, 103386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103386

- Escobar, A. (2004). Beyond the Third World: Imperial globality, global coloniality and anti-globalisation social movements. Third World Quarterly, 25(1), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659042000185417

- EuroNews. (2023). Seeking solutions beyond growth in 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CUDQbujZ5xA.

- Evans, G., & Phelan, L. (2016). Transition to a post-carbon society: Linking environmental justice and just transition discourses. Energy Policy, 99, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.05.003

- Everingham, P., Peters, A., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2021). The (im)possibilities of doing tourism otherwise: The case of settler colonial Australia and the closure of the climb at Uluru. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103178

- Farmaki, A. (2019). Visitor-host encounters in post-conflict destinations. The case of Cyprus. In R. K. Isaac, E. Çakmak, & R. Butler (Eds.), Tourism and hospitality in conflict-ridden destinations (pp. 240–252). Routledge.

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

- Friel, M. (2021). First cruise liner sailing into Venice since the start of the pandemic met by hundreds of protesters demanding ‘No Big Ships’. Business Insider. Retrieved 22 May 2023, from https://www.businessinsider.com/video-venice-protesters-oppose-the-first-cruise-ship-since-pandemic-2021-6.

- Furlan, M., & Mariano, E. (2021). Guiding the nations through fair low-carbon economy cycles: A climate justice index proposal. Ecological Indicators, 125, 107615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107615

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Harman, S., Erfani, P., Goronga, T., Hickel, J., Morse, M., & Richardson, E. T. (2021). Global vaccine equity demands reparative justice—not charity. BMJ Global Health, 6(6), e006504. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006504

- Heffron, R. J. (2022). Applying energy justice into the energy transition. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 156, 111936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111936

- Hickel, J. (2021). How to achieve full decolonization. The New Internationalist. Retrieved 17 October 2022, from https://newint.org/features/2021/08/09/money-ultimate-decolonizer-fjf.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2018). The potential for justice through tourism. Via Tourism Review, 13(13). https://doi.org/10.4000/viatourism.2469

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2022). The ongoingness of imperialism: The problem of tourism dependency and the promise of radical equality. Annals of Tourism Research, 94, 103382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103382

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2022). The question of solidarity in tourism. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2022.2107657

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Everingham, P. (2022). Degrowth in tourism: Advocacy for thriving not diminishment. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2079841

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Blanchard, L.-A., & Urbain, Y. (2022). Peace through tourism: Critical reflections on the intersections between peace, justice, sustainable development and tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(2–3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1952420

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1926–1944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1601732

- Izaguirre, A. (2023). DeSantis moves to ban critical race theory in state colleges in Florida. Retrieved 22 May 2023, from https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/desantis-moves-to-ban-critical-race-theory-in-state-colleges-in-florida/2962569/.

- Jamal, T. (2019). Justice and ethics in tourism. Routledge.

- Josiassen, A., Kock, F., & Assaf, A. G. (2022). In times of war: Place solidarity. Annals of Tourism Research, 96, 103456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103456

- Josiassen, A., Kock, F., Assaf, A. G., & Berbekova, A. (2023). The role of affinity and animosity on solidarity with Ukraine and hospitality outcomes. Tourism Management, 96, 104712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104712

- Levy, B. S., & Patz, J. A. (2015). Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Annals of Global Health, 81(3), 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.008

- Lo, K. (2021). Authoritarian environmentalism, just transition, and the tension between environmental protection and social justice in China’s forestry reform. Forest Policy and Economics, 131, 102574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102574

- Low, N., & Gleeson, B. (1998). Justice, society, and nature: An exploration of political ecology. Routledge.

- Lyubchenko, O. (2022). On the frontier of whiteness? Expropriation, war, and social reproduction in Ukraine. LeftEast. Retrieved 6 June 2022, from https://lefteast.org/frontiers-of-whiteness-expropriation-war-social-reproduction-in-ukraine/.

- Marín, A., & Goya, D. (2021). Mining—The dark side of the energy transition. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 41, 86–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.09.011

- Martiskainen, M., & Sovacool, B. K. (2021). Mixed feelings: A review and research agenda for emotions in sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 40, 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.023

- McCauley, D., & Heffron, R. (2018). Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

- McGregor, D., Whitaker, S., & Sritharan, M. (2020). Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.007

- Mert, U. (2016). Risk management for sustainable tourism. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 7(1), 63–71.

- Mika, J. P., & Scheyvens, R. A. (2022). Te Awa Tupua: Peace, justice and sustainability through Indigenous tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(2-3), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1912056

- Okereke, C., & Coventry, P. (2016). Climate justice and the international regime: Before, during, and after Paris. WIREs Climate Change, 7(6), 834–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.419

- Oquist, B. (2022). The era of the great carbon fraud is upon us. Australia Institute. Retrieved 14 January 2023, from https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/the-era-of-the-great-carbon-fraud-is-upon-us/.

- Perkins, E. E. (2019). Climate justice, commons, and degrowth. Ecological Economics, 160, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.02.005

- Plumwood, V. (2002). Environmental culture: The ecological crisis of reason. Routledge.

- Porter, L., Rickards, L., Verlie, B., Bosomworth, K., Moloney, S., Lay, B., Latham, B., Anguelovski, I., & Pellow, D. (2020). Climate justice in a climate changed world. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), 293–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1748959

- Power, C. (2016). Multispecies ecofeminism: Ecofeminist flourishing of the twenty-first century [Thesis University of Victoria]. https://base.socioeco.org/docs/power_chelsea_ma_2020.pdf.

- Prayag, G. (2018). Symbiotic relationship or not? Understanding resilience and crisis management in tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 133–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.012

- Rastegar, R. (2022). Towards a just sustainability transition in tourism: A multispecies justice perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.06.008

- Rastegar, R., & Ruhanen, L. (2022). The injustices of rapid tourism growth: From recognition to restoration. Annals of Tourism Research, 97, 103504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103504

- Rastegar, R., & Ruhanen, L. (2023). Climate change and tourism transition: From cosmopolitan to local justice. Annals of Tourism Research, 100, 103565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103565

- Rastegar, R., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Ruhanen, L. (2021). COVID-19 and a justice framework to guide tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103161

- Ritchie, B. W., & Jiang, Y. (2019). A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102812

- Robinson, M., & Shine, T. (2018). Achieving a climate justice pathway to 1.5 °C. Nature Climate Change, 8(7), 564–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0189-7

- Rorty, R. (1989). Contingency, irony, and solidarity. Cambridge University Press.

- Rose, D. B. (2004). Reports from a wild country: Ethics for decolonisation. UNSW Press.

- Schroeder, K. (2018). The politics of gross national happiness: Governance and development in Bhutan. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schwartz, J. M. (2007). From domestic to global solidarity: The dialectic of the particular and universal in the building of social solidarity. Journal of Social Philosophy, 38(1), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2007.00370.x

- Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2022). A review of research into tourism and climate change - Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 95, 103409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.10340

- Sovacool, B. K. (2021). When subterranean slavery supports sustainability transitions? power, patriarchy, and child labor in artisanal Congolese cobalt mining. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(1), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.11.018

- Standish, D. (2023). Mass tourism in Venice: Are city officials overreacting? The Good Tourism Blog. Retrieved 22 May 2023, from https://www.goodtourismblog.com/2023/04/mass-tourism-in-venice/.

- Ter Meulen, R. (2017). Solidarity and justice in health and social care (pp. 71–108). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107707023.004

- Tooze, A. (2022). Welcome to the world of the polycrisis. The Financial Times (Online). Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33.

- Treves, A., Santiago-Ávila, F. J., & Lynn, W. S. (2019). Just preservation. Biological Conservation, 229, 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.018

- UN. (2020). The climate crisis – A race we can win. Retrieved 29 June 2022, from https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2020/01/un75_climate_crisis.pdf

- UN. (2021). Low-income countries have received just 0.2 per cent of all COVID-19 shots given. Retrieved 3 October 2022, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/04/1089392.

- UNWTO. (2021). Launching of the Glasgow Declaration: A commitment to a decade of climate action in tourism. https://www.unwto.org/event/cop-26-launch-of-the-glasgow-declaration-a-commitment-to-a-decade-of-climate-action-in-tourism.

- UNWTO. (2022). World Tourism Day 2022 – rethinking tourism. Retrieved 17 October 2022, from https://www.unwto.org/world-tourism-day-2022.

- Venn, A. (2019). 24 - Social justice and climate change. In T. M. Letcher (Ed.), Managing global warming (pp. 711–728): Academic Press.

- Wang, X., & Lo, K. (2021). Just transition: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102291

- Watene, K. (2016). Indigenous peoples and justice. In K. Watene & J. Drydyk (Eds.), Theorizing justice: Critical insights and future directions (pp. 133–151). Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Whyte, K. P. (2018). Indigenous science (fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral dystopias and fantasies of climate change crises. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 1(1–2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618777621

- WWF. (2022). Living planet report 2022 New Zealand. Retrieved 17 October 2022, from https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-NZ/.

- Zarezadeh, Z., & Rastegar, R. (2023). Gender-leisure nexus through a social justice lens: The voice of women from Iran. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.02.003