Abstract

Tourism interventions, as tools for social change and preservation of natural and cultural assets are inherently complex. This study presents an improved method for the evaluation of complex tourism interventions. We argue that participatory methods can promote a culture of evaluation that supports partners throughout evidencing project impacts, eliminating negative attitudes to evaluation resulting from fear of being judged on performance. We demonstrate that Theory of Change (ToC) is an effective tool that allows organisations to actively co-create and own an evaluation strategy to ensure the delivery of project outcomes. We show how ToC can be applied as a useful process and impact evaluation tool. This paper represents a novel methodological application of ToC based on participatory approaches to evaluation to disseminate knowledge and to improve decision-making in the field of tourism interventions and tourism policy making.

Introduction

An intervention refers to a combination of activities or strategies designed to assess, improve, or promote benefits among individuals or a portion of the population (Clarke et al., Citation2019). Evaluating impacts of interventions is often a compulsory task, yet evaluation research focusing specifically on impacts of tourism interventions is underdeveloped (OECD, Citation2012; Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021). Demonstrating that public funds used for interventions have brought about positive change is crucial. However, evaluations of tourism interventions have often proven unsuccessful in accounting for impacts, partly due to the ineffective evaluation methods utilised (Dyson & Todd, Citation2010; Phi et al., Citation2018). Belonging to the category of social interventions, large tourism interventions with multi-level socio-economic and environmental outcomes cannot be evaluated holistically through simplistic cause and effect relationships (Vanclay, Citation2015).

Participatory evaluation is a term for evaluation approaches that involve project participants in decision-making and other activities related to the planning and implementation of the evaluation strategy (Mathison, Citation2005). Whilst in the field of development studies there is plenty of literature applying qualitative and participatory methods for impact evaluation, there is little in the field of tourism policy making on concepts such as lesson learning and policy transfer which can be drawn from evaluations (Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2011). Being part of a wider strategy to deliver social change or conservation, tourism interventions require effective methods of evaluation to account for the variety of impacts they produce. The formative evaluation experience of co-designing encourages real-time learning, instead of being assessed on final performance, creating the precedent for lasting project legacies. Theory of Change (ToC) is a participative evaluation tool which allows to map-out long-term desired outcomes of an intervention and identify the investments and activities which will lead to the achievement of those outcomes (Taplin et al., Citation2013; Weiss, Citation1998). It is particularly useful to make explicit causal relationships between activities and their outcomes.

Interventions that include multiple independent and interactive components are defined as complex (Rogers & Funnell, Citation2011). Quantitative impact evaluations traditionally used in tourism tend to report visitor numbers, length of stay and visitor expenditure, without the how and why of wider impacts achieved. Moreover, ex-post summative approaches to evaluation do not provide project partners with the tools nor the knowledge to deal with unintended outcomes and respond to the ever-changing external context in which interventions are implemented (Hachmann, Citation2011; Haarich et al., Citation2019; Warnholtz et al., Citation2022). We argue that traditional summative impact evaluation is often reduced to a tick-box accountability exercise and leaves no space for co-learning and creating a long-lasting project legacy (Højlund, Citation2015; Vanclay, Citation2015). A key factor in determining the success of a project lies in its flexibility in adapting and responding to unexpected challenges along the way (Vanclay, Citation2015). To improve the design of tourism interventions for better policy making, evaluation approaches need to allow for this flexibility.

The aim of this article is to address the dearth of knowledge on evaluation of complex tourism interventions alongside the methodological issues described above. With only a handful of qualitative evaluation studies published in tourism (Gregory-Smith et al., Citation2017; Phi et al., Citation2018; Eckardt et al., Citation2020; Warnholtz et al., Citation2022), this paper explores how participatory, formative evaluations are powerful co-learning tools that allow to evaluate an intervention more holistically, if implemented from the early stages of a project. We focus specifically on how participative methods of evaluation improve co-design and learning for project partners. We highlight how this approach to evaluation helped to establish a sense of trust with project partners who no longer perceived the team of researchers as an external body judging them on their performance, alleviating the fear of evaluation.

Literature review

Evaluation is generally considered a tedious and dreaded task that organisations must endure to secure public funding. Large-scale project evaluations are mostly conducted ex-post, focusing on quantitatively measuring results with little attention paid to the contextual conditions of project partners and the environment in which the project is implemented (Knippschild & Vock, Citation2017). Evaluations are rarely seen as useful learning exercises, placing little emphasis on why or how a project did (or did not) achieve change (Hachmann, Citation2011). Most summative evaluations are result-oriented, produced ex-post and often externally, to demonstrate that the funders’ money was well-spent (Morra and Rist, Citation2009; Hachmann, Citation2011, Højlund, Citation2015).

We embrace the idea that evaluation should be a meaningful learning experience, and challenge the notion that objectivity and credibility of evaluations only derive from evaluations conducted externally (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011) through a set of generic quantitative indicators. Participative evaluation methods are different and yet may be applied in both internal and external evaluations (Morra & Rist, Citation2009). To judge which approach to evaluation holds the most value, the definition provided by Cronbach et al. resonates significantly with our stance: “… excellence ought to be judged against how evaluation could serve a society… An evaluation pays off to the extent that it offers ideas pertinent to pending actions and people think more clearly as a result” (1981, p. 65). By being clear on why and for whom we are evaluating, we can identify different types of impact evaluations, based on differing evaluation paradigms and values.

Although criticisms may arise around a lack of objectivity and credibility of evaluations conducted internally against those conducted externally (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011; Morra & Rist, Citation2009), participatory evaluation methods conducted internally encourage evaluators to act as facilitators and trusted advisors, supporting partners in making the assessment and learning throughout this process (Northcote et al., Citation2008). Evaluation is beginning to be considered as a participatory tool to empower project partners and increase capacity within institutions and organisations (Vanclay, Citation2015). Increasing the application of robust, participatory, qualitative methods of evaluation provides the opportunity to better unpack causality and address unexpected outcomes throughout the project implementation process.

What is ToC?

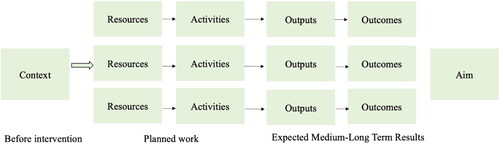

A ToC is an evaluative framework to address why and how a project works by identifying causal links between activities and outcomes (Taplin et al., Citation2013; Weiss, Citation1998). It is usually presented in a diagram or map (see example in below) depicting how the activities of an intervention lead to outputs, outcomes and impacts. Used as a participatory evaluation method, it encourages project partners to reflect on how and why change is to be achieved (Getz, Citation2019, Vogel, Citation2012). The iterative process of development of a ToC is as important as the product that results from it (Getz, Citation2019; Wigboldus & Brouwers, Citation2011).

An analysis of both the context where the change is taking place and the role of the intervening parties is crucial to understand why an intervention achieves a set of outcomes in a particular context (Vogel, Citation2012). Co-designing a ToC from the outset is a thinking process that can steer a project towards the desired goals and help get the most value out of an evaluation. Whilst it is easier to look at projects retrospectively and create a convenient discourse around what results it did or did not achieve, and more importantly why, ToC requires ex-ante theorising with project partners, creating a greater sense of accountability and responsibility (Eguren, Citation2011). Much more than designing a linear diagram, ToC must be intended as a continuously evolving tool articulated, tested and improved over time with those involved in its design (Dillon, Citation2019, Vogel, Citation2012).

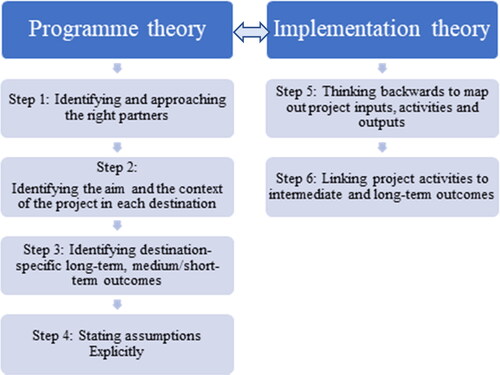

Originally, Weiss (Citation1998) described ToC as being comprised of two equally important components: programme theory and implementation theory. Programme theory is concerned with uncovering causal links between the mechanisms triggered by the activities of a project and their possible outcomes. Implementation theory refers to the operational side of a project. It underpins the physical resources and activities that are required to translate objectives into practice, the so called “nuts and bolts” of project operations (Weiss, Citation1998).

Why implement ToC to evaluate tourism interventions

Despite tourism interventions being a prime example of social interventions in complex settings, there is a lack of appropriate evaluation methods implemented to evidence wider tourism impacts (Maini et al., Citation2018) and still, this remains at a primarily theoretical/methodological level (e.g. Bertella et al., Citation2021). The aim of social interventions is to improve the welfare of a particular area or target group through specifically designed strategies (Warnholtz et al., Citation2022). Social interventions may trigger multiple visible and invisible, mechanisms leading to various expected and unexpected outcomes. Yet, little research has been conducted to these mechanisms and processes when implementing tourism interventions and deal with the uncertainty and non-linearity of outcomes (Park & Yoon, Citation2011; Phi et al., Citation2018; Warnholtz et al., Citation2022).

Tourism academics and consultants tend to evaluate interventions without considering the socio-cultural context of the destination, nor the wider social and environmental impacts the intervention generates (Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021). Reducing success to quantifiable outcomes, figures such as visitor numbers, length of stay and visitor expenditure (e.g. Baral & Rijal, Citation2022; Gasparini & Mariotti, Citation2021; Kitamura et al., Citation2020) does not allow the understanding of the process that led to those outcomes, understanding necessary to transfer interventions elsewhere (Gregory et al., 2017). For an evaluation to be (1) context-sensitive, (2) explain how and why certain impacts were achieved (Peeters et al., Citation2018; Stoffellen, Citation2018), and (3) offer learning opportunities to initiate social change (Bertella et al., Citation2021), complementary quantitative and qualitative evaluation is needed (Vanclay, Citation2015; Waas et al., Citation2014).

To evaluate tourism interventions holistically, it is necessary to revise our approach to evaluation and our understanding of “impact.” As discussed in Northcote et al. (Citation2008), involving stakeholders in the design of an evaluation strategy is pivotal as this allows to and co-learn with those implementing tourism interventions. Whilst ToC is widely implemented in development studies (e.g. Maini et al., Citation2018; Mayne & Johnson, Citation2015; Vogel, Citation2012), it is surprisingly absent from the tourism literature (Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the study conducted by Phi et al. (Citation2018) evaluating a tourism intervention to alleviate poverty in Vietnam, along with the study conducted by Warnholtz et al. (Citation2022) investigating how tourism projects can act as catalysts for social change, represent the only practical examples of the application of ToC to evaluate complex tourism interventions. Both were applied outside the context of EU-funded regional development programmes, where many studies have highlighted the difficulties faced by stakeholders to appraise a true value of the programme (e.g. Ioannides et al., Citation2006; Liberato et al., Citation2018; Shepherd & Ioannides, Citation2020; Stoffellen & Vanneste, Citation2017).

Despite the call for widening impact evaluation towards more qualitative aspects of tourism impacts, this has yet to be achieved in practice. Phi et al. (Citation2018) argue that ToC contributes to opening the “black-box” of why and how tourism interventions succeed or fail. This is because ToC workshops offer a space to question the rationale of project activities towards achieving desired outcomes (Bertella et al., Citation2021). This paper responds to this gap by adopting more holistic approaches to evaluate tourism interventions, and more specifically around the implementation of ToC to evaluate complex tourism interventions. As a participative approach to evaluation which empowers project implementers, ToC can contribute towards the achievement of positive, lasting social change (Bertella et al., Citation2021; Getz, Citation2019; Sullivan & Stewart, Citation2006; Warnoltz et al., 2022).

Challenges when adopting ToC as an evaluation tool

The term ToC and its graphs have often been misused and reduced to a simple, linear logic map that does not account for the level of complexity and causal relationships present in an intervention (Allen et al., Citation2019). When researchers and stakeholders co-construct a relevant theory for the proposed intervention this entails making a series of assumptions explicit, around how and why they expect certain activities to bring around desired change (Mayne, Citation2015). This process can get extremely messy and poses a set of challenges. First, getting partners to buy-in on this approach is not always straightforward. It is crucial to dedicate sufficient time and effort to develop a good level of trust between the researcher and the stakeholders prior the co-design of a ToC. This allows participants to reflect and share their thoughts with honesty (Vogel, Citation2012). Where this does not happen, it can be tempting for the researcher to take a more active role, significantly undermining the stakeholders’ ownership of the ToC, and loosing much of the initial purpose and the opportunity to create a meaningful co-learning experience (Maini et al., Citation2018; Sullivan & Stewart, Citation2006).

Second, we may face the risk of assuming linearity when attributing causality between certain activities and outcomes. However, it is important to ensure that the end product is not an overly simplified diagram misrepresenting the true complexity of interventions (Davies, Citation2018). Nested ToCs can partly tackle such over-linearity, by allowing the researcher to gain more insight into how programme theory unfolds at more granular levels, helping avoid overly complicated, confusing diagrams that fail to communicate programme logic (Douthwaite & Hoffecker, Citation2017; Mayne, Citation2015). We have addressed both these challenges within our methodology.

A complexity-aware ToC

Debates around the application of complexity social science to evaluation have been increasing (e.g. Byrne, Citation2013; Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021) due to the belief that complex policy interventions seeking to achieve change across multiple levels (individuals, communities, and societies) cannot be evaluated appropriately by using exclusively experimental methods (Maini et al., Citation2018; Walton, Citation2014). The integration of theory-driven, complexity-sensitive approaches produce a better management of the change trajectory and challenge the current policy cycle status quo (Allen et al., Citation2019). We respond to this call by harnessing ToC as a tool to better understand the unpredictable dynamics throughout the implementation of a project leading to increased uncertainty about outcomes. Complexity-aware approaches offer positive responses to uncertainty and support the evaluation through a more effective tracking of change (Vogel, Citation2012). A complexity-aware ToC is not simply a logic model showing the steps of change, but a tool to identify points with uncertain outcomes to subsequently monitor change in an agile and adaptive way.

Methodology

Our stance of participative approaches being an epistemological necessity to conduct useful evaluations directly informed our choice of qualitative methods of data collection. We applied ToC to develop a joint understanding of how change is expected to occur and what needs to happen to achieve it. Although elsewhere interviews have been conducted to gradually piece together the ToC graph (e.g. Phi et al., Citation2018), we adapted the stepwise approach that appears in various ToC guidelines to co-design these graphs via workshops (Maini et al., Citation2018; Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021; Vogel, Citation2012). Building the ToCs collaboratively allowed partners to discuss and reconcile their perspectives simultaneously. This study was carried out following ethics approval from the lead author’s institution (reference number: 640816-640807-73226368). All project partners were aware of the lead authors’ researcher role and informed consent was obtained prior to the workshops.

The setting for the evaluation is a cross-border EU Interreg programme called “Experience” that ran across six regions from September 2019 until March 2023 within the French-English Channel and involved fourteen partners (six regional councils, four Destination Management Organisations (DMOs), one charity, one university and two private organisations). Local business networks, local accessibility groups and residents were also engaged. “Experience” was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund for €24.5 million. “Experience” trained businesses to develop sustainable experiential tourism activities in the winter season, with the aim of decreasing seasonality. By adapting infrastructure, delivering training and promoting new experiential and accessible itineraries, the project aimed to become a leading international example of year-round innovative experiential tourism. It represents one of the largest tourism projects funded by the EU so far.

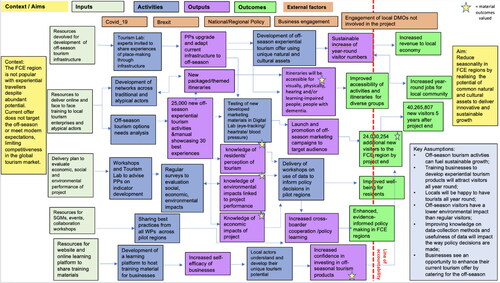

ToC was initially introduced during a project-wide steering group meeting where the research team presented partners with the overarching project ToC (see ). This was previously teased out by the research team when analysing the project proposal document and served as a building block in the co-design of nested, regional ToCs. The researchers were aware of the sensitive, governmental roles of the partners involved, who were assured of their anonymity. Hence, whilst we can share the overarching ToC extrapolated from the proposal document, we are unable to publish the individual partners’ nested ToCs. Instead, we will utilise the overarching ToC as a sample of what the final graphs looked like and explain the process adopted to design it.

We facilitated individual workshops for each project partner who requested them. We developed six ToCs involving members of each project partner with different hierarchies who worked on different work-packages, to increase the likelihood of correctly mapping progress and challenges. We co-designed the nested ToCs at different points in time, and with different Covid restrictions in place. Consequently, some workshops took place online, and some occurred face-to-face. We co-designed the initial six regional ToCs between August 2021 and December 2021. A second round of ToC workshops to re-visit and discuss progress made against the previous ToCs was run between August and November 2022, at an interim stage of the project. A final ToC workshop was facilitated by the lead author in February 2023, at a face-to-face final project-wide steering group meeting held during the project closure period. The workshops were facilitated by the lead author and lasted between 90-120 min. During the online workshops, the researcher shared a link to an empty ToC template on the online platform MURAL, that all participants could populate simultaneously whilst discussing and agreeing upon the various elements of the ToC. During the face-to-face workshops, participants wrote outcomes, outputs activities and assumptions on post-it notes, and these were then attached to the ToC template printed on a poster. Minutes of the discussion were also taken by a minute-taker appointed by the lead partner, as requested by our funder, and these were also shared with the researcher.

At the end of each workshop both face-to-face and online the first author went through her notes, tidied up the graph (or created a digitised version when the workshop took place in person) and sent it for review. Once partners had added their own inputs, the ToC was shared, and updated and adapted on a 6-9 monthly basis. The research team maintained regular contact with project partners throughout the project implementation, and the nested ToCs were used to guide and reflect upon the progress taking place and to structure each partners’ final evaluation report. The following sections illustrate the steps we followed to build the nested ToCs. Steps 1-4 contributed towards building a programme theory, whilst steps 5-6 constitute the implementation theory (Weiss, Citation1998). The final ToC workshop held during project closure was particularly useful to discuss the extent the programme theory and implementation theory held true against initial assumptions and expectations.

Workshops: co-designing the ToCs with project partners

Step 1: Identifying and approaching the right partners. We offered all partners the opportunity to reach out to us to co-develop their nested ToC, approaching first those partners with whom we had developed closer ties, hoping that this would inspire others to follow suit. Once the first nested ToC was uploaded to the projects’ shared project management platform, other partners came forward and requested to co-design a ToC for their own. This process enhanced the theoretical relevance of our sample since the partners who took part in the co-design of the nested ToCs did so because they actively chose to engage.

Step 2: Identifying the aim and the context of the project in each destination. We started the workshops by defining key terms, ensuring that partners were clear and comfortable with the vocabulary being used. Next, partners were shown an empty template of a ToC, the starting point of which was to fill in the boxes regarding the aim and the context/need for project activities (see below). The researcher gradually guided the partners towards articulating how they expected change to happen, bringing it to the surface through a visual representation. Identifying an overall aim was crucial to move onto discussing the context in which the project was being implemented, reflecting on what contextual need the project was responding to.

Step 3: Identifying destination-specific long-term, medium-term outcomes. Partners were prompted to discuss and reflect upon what short-medium term and long-term outcomes were the aim of the project. This may be the most important element of a ToC Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021).When designing the nested ToCs partners were encouraged to identify outcomes that were possible and attributable to the project at least in part. This ensured partners agreed on being held accountable for working towards those outcomes.

Step 4: Stating assumptions explicitly. The outcome mapping process helped partners to visualise the change they wished to achieve and prioritise their goals, as well as identify what outcomes they agreed to be held accountable for. Explicitly discussing assumptions encouraged partners to be realistic and to identify the conditions required for their ToC to develop according to plan (Mayne & Johnson, Citation2015). Hence, for each long-term goal, the researcher ensured assumptions were also identified and incorporated within the diagram. This gave the opportunity to question the rationale behind the outcomes identified in the previous step, and forced participants to be more explicit on why they believed the project could work.

Step 5: Thinking backwards to map out project inputs, activities, and outputs. The researcher guided participants through the backward-mapping process of identifying the project’s outputs and activities leading to the intermediate and long-term outcomes. For inputs, we identified the physical resources invested through the project to fund activities such as training, marketing, and promotion, implemented to help achieve the intermediate and long-term outcomes. This also included the identification of key outputs and activities that had already taken place, encouraging partners to compare the initial overarching ToC (see ) with their own timeline, and to identify what change had occurred according to plan, as well as to acknowledge those activities that had proven successful in bringing about some change as medium-term outcomes. Mapping the ToC also helped participants identify areas in which more activities were required to stay on track and achieve desired outcomes.

Step 6: Linking project activities to intermediate and long-term outcomes. Participants were prompted to discuss the links connecting the outputs, activities, and short/medium-term outcomes to the long-term outcomes, to build the pathways to change. The researcher challenged participants to discuss why those activities were expected to lead to desired goals. This stage is often thought of as the “messiest” one (Twining-Ward et al., Citation2021) because of the many moving parts within the project, hence designing a final diagram that all participants were happy with required a lot of revising. Once a final version was drafted, the researcher tidied-up the diagram and sent it to participants for to review.

ToC data analysis

Data collection and data analysis occurred simultaneously through collaborative workshops (e.g. Mayne, Citation2015, Breuer et al., Citation2016).Positioning herself as an expert facilitator who, by no means attempted to speak for project partners, the researcher encouraged the latter towards activating their own narrative. With multiple participants’ perspectives being collected and reconciled, the final ToC graph was the product of multiple iterations and discussions and did not require further analysis. That being said, ToC is said to be more articulate when integrated with an in-depth narrative evaluation report (Phi et al., Citation2018), providing a more detailed account of the different assumptions, rationale, and mechanisms at play. Hence, it was agreed with partners that the nested ToCs would also be used to articulate the change narrative in their final evaluation reports for the project funders to review. At the time of writing this article, project partners have finalised their regional project evaluation reports, supported by the updated versions of the nested ToCs reviewed in November 2022.

Findings

As the paper aims to showcase the method, we provide the official, project-wide ToC (), used to develop the nested ToCs without compromising confidentiality. For reasons of anonymity, we are unable to disclose partners’ graphs that emerged from the regional ToC workshops.

Uncovering partners’ change narratives through nested ToCs (programme theory)

Providing a legend at the top of each diagram was instrumental as during the workshops, a clear colour code for each element in the ToC helped keep participants focused on the different components we were discussing. The yellow boxes represent the context and the aim of the project identified in Step 2 (see ). Whilst in the graph above, the yellow boxes refer to the context and need of the project overall across all six destinations, in the nested ToCs these were destination-specific. For example, one partner identified the context for the project in their destination as “an unsustainable tourism offer, overly reliant on peak season and damaging for the social fabric of our community”. Their aim was: “To take the ‘peak’ out of the peak season and develop an integrated and coherent marketing strategy with our local destination management organisation to attract the right type of visitors, distributed more equally throughout the year, reducing the pressure on our locals.” Both context and aim of this project partner reveal an issue of over-tourism in peak season, causing their main concern to be the damaging effect over-tourism was having on their locals. Through the project they identified an opportunity to reconnect with their locals:

…you know, we just aren’t so comfortable with data…but I think we have made progress in the sense that, knowing how our residents feel and collecting regular data has become really important to us since working on this project with you guys… we are getting a chance to reconnect with our residents and show them we care. There is no easy fix really and a lot is out of our control, but we are moving in the right direction…these issues are really important to us in PLACENAME, some of the issues have hit colleagues working alongside us as well which brings the issue even closer to home.

Looking back at , and moving onto the green boxes, we now compare long-term outcomes. These were identified during the workshops in Step 3 (see ). Whilst in the ToC graph in these are long-term outcomes all partners signed-up to achieve through the project overall, in the nested ToCs long-term outcomes were translated into aspirations each partner had for their destination respectively. A long-term outcome in the ToC shown in indicates “improving accessibility of activities and itineraries.” This long-term outcome that appears in the overarching ToC revealed some interesting findings and allows us to show how ToC was a useful tool during the interim stage of project implementation.

The nested ToCs revealed a variety of interpretations and different degrees of importance were given to this outcome in each pilot region. One partner identified “local residents and visitors with disabilities feel more empowered,” as a key long-term outcome they wished to contribute towards through the project. However, others completely ignored the “improving accessibility” long-term outcome, focusing more on increasing economic revenue for locals and creating year-round job prospects through experiential tourism products.

Moving backwards towards activities and outputs, a main challenge was to identify the links between physical resources, activities and outputs to explain why these would lead to desired long-term outcomes. Those wishing to empower locals and visitors with disabilities amongst their long-term outcomes identified activities such as “accessibility testing,” “widening paths,” “increasing rest points,” “introducing wheelchair picnic benches,” “inclusion and diversity photography brief,” “one-to-one meetings with local access groups and disability groups.” These activities were aimed at making itineraries more accessible, as an output. When it came to stating assumptions explicitly (Step 4), this outcome was underpinned by the assumption that “connecting with local access groups, residents and visitors with disabilities to understand what we can do to enhance their experience will help them feel empowered and included in our tourism offer.”

Identifying causal relationships and addressing emergent outcomes (implementation theory)

The findings show that bringing together the project team within a partner organisation to discuss and identify causal links between project resources, activities and outcomes allowed for a deeper understanding of how the project was unfolding in each pilot region according to the different agendas. What emerged clearly from the first round of workshops was that none of the partners highlighted how change was maximised through cross-border collaboration, a requirement of the funder. When asked about a key project output that should have occurred early in the project through cross-border collaboration, as evidenced in “developing a learning platform,” partners responded with silence and a degree of embarrassment, acknowledging that so far that had been a project failure, possibly due to a lack of cooperation amongst the entire partnership.

The way different partners prioritised outcomes and the subsequent actions from the lead partner provide examples of the usefulness of a ToC approach as an interim evaluation tool, responsive to emergent outcomes. Based on what emerged in terms of lack of collaboration on the learning platform, the lead partner swiftly took responsibility for its development to avoid failure. Moreover, by comparing the over-arching ToC with the nested ones at an interim stage of project implementation, we noticed that whilst increasing accessibility by 33% was a project-wide output to be achieved, some partners had planned very little budget for activities related to accessibility, or completely ignored this in their planned activities at a regional level. Based on this evidence, the lead partner took action to remind partners that although the increase in accessibility of the tourism offer was to be intended as a project-wide increase, all partners were required to contribute individually towards this output by allocating specific funds, planned activities or infrastructure adjustments in place. In response to this, all project partners adjusted budgets and activities accordingly, to evidence how they would be contributing to that outcome in their own pilot region.

Developing positive attitudes to evaluation and building trust with project partners

Partner buy-in for the development of a ToC did not occur automatically, but once the most proactive partners designed theirs, the rest naturally followed suit. Only during the ToC workshops participants truly understood its value. During the backwards mapping process, participants were asked to use their knowledge of the context and project implementation to explain why they expected the project resources and activities to leverage the desired change. They all responded positively to such enquiries. The tones were amicable, the environment cooperative and friendly. This was made clear with comments such as:

‘this is such a useful exercise, I will hang both [ToCs] up by my desk’, ‘having this is so helpful to keep on track of what we’re doing and what still needs to be done’, ‘it’s a good reminder of where we are all supposed to be going with the project’, ‘it has really helped us reflect on how our activities are creating impact and what we need to do more of’, ‘this graph has been so helpful for me joining the project at a much later stage, it has given me a full overview of what each work package is trying to achieve and how it all comes together towards one goal.

it’s really useful to look at this and see how far we have come with the project, considering…well, we didn’t have very high expectations other than refurbish a ***! Seeing where we are halfway through project… this is really useful, thank you…we can show this in our next meeting with *county council senior staff member* and we look forward to reviewing it.

Participants approached the workshops and generally any communication with the research team with an honest attitude. The level of honesty was surprising and directly proportionate to the level of trust placed with the research team leading the evaluation. A clear example of this is that of a partner who admitted: “Well… the truth is… we entered this project because we needed funding for X infrastructure.” The sentence itself is not surprising, but the very fact that a partner opened-up to the evaluator, certainly is. This trust provides further evidence that the research team were not perceived as evaluators to be judged by, but rather as trusted advisors. This exemplifies the kind of co-learning through evaluation this study advocates for.

We used quotes from participants to show how ToC as a participative evaluation tool allowed us to establish a trusted, collaborative relationship to co-design this evaluation. There were no formal interviews with project partners to collect feedback around how they felt about using ToC. Nevertheless, we feel that because these comments occurred naturally either during the workshop or during follow-up one-to-one meetings and steering group meetings across the partnership, the feedback we received was even more genuine as participants were not influenced nor forced to provide feedback but did so because they wanted to express their gratitude.

ToC as a progressive evaluation tool: insights from project planning, interim evaluation and project closure

During the planning phase ToC helped identify partners’ capacities and establish the need for data collection to ensure appropriate evidencing of project impacts. When discussing the ToC, it became evident that partners were familiar with collecting economic data, and confident in reporting on tangible outputs such as infrastructure improvements, new itineraries, new experiential products, etcetera. They were largely inexperienced however in measuring less-tangible outcomes such as increasing well-being of locals. We held several discussions to clarify what was intended for impact as opposed to outputs, and how to demonstrate impact associated with project activities. Following four indicator-development workshops and many one-to-one meetings with project partners, we agreed on a common residents’ survey which we collected across the lifespan of the project, twice a year for three years. The aim of this survey was twofold: 1) to understand residents’ perceptions of the tourism offer in their local area; 2) to identify how project activities were contributing to residents’ well-being. Having identified a clear need for the data collection during the ToC planning phase, the timely results from this survey were instrumental during the interim stages of the project.

Results from the interim evaluation helped project partners discover the value of an underdeveloped and under-researched segment of the market: the so called “hyper local.” What emerged from comparing the first wave in 2020 to the fourth wave in 2022 was that due to the Covid-19 pandemic, residents replaced tourists at attractions, but most importantly, even with Covid-19 travel restrictions lifted, intentions to take more day trips to discover the local area had increased significantly to 54%. In response to this data, project partners began to provide tailored content, promotion and campaigns dedicated to this new type of visitor that had previously been overlooked. ToC supported us in planning ahead how to report on this outcome, measure this outcome at an interim stage, and plan further actions based on these results. Revisiting the ToC at an interim stage and using the data collected helped maximise the achievement of this outcome.

During the last face-to-face Steering Group Meeting (February 2023), the lead author revisited the ToC shown in to discuss lessons learned as a partnership. It was a convivial yet insightful moment to collect reflections in a period in which partners were working on the final project closure reports. Some of the major assumptions the ToC () was based upon were explored, i.e. that businesses would engage and be willing to tailor their activities to the low season, and that training businesses to design new experiential tourism products would encourage year-round visitors and sustainable growth. Partners shared how business collaboration received during the project’s lifespan had been greater than anticipated. Without the businesses’ engagement, it would have been impossible to develop a diverse and exciting experiential tourism offer for the low-season. Moreover, partners shared that many businesses had registered an increase in revenue streams as opposed to the same low-season period before “Experience,” and some businesses had opted to remain open instead of closing during low-season.

When reflecting on “what went wrong,” some important mechanisms emerged. Partners agreed that appointing an external tourism data consultant throughout the entire implementation period within each region would have saved a lot of time and mitigated the impact of knowledge lost due to frequent staff turnover. We found that those regions with at least one member of internal staff with data expertise and who was employed throughout the entire implementation period, experienced less difficulties in retrieving data sets for evaluation purposes and produced more in-depth and relevant analysis for the final evaluation reports. In contrast, the partners that experienced frequent staff turnover and where none of the internal staff were skilled with data collection and analysis methods were the weaker links. This was evident in the regional evaluation reports, where the sections on “lessons learned” and “what decision did we take differently because of data” received scant attention by the latter.

Reflecting still on what went wrong, the “learning platform” was identified as a “project fiasco”. In this is described in the last line of the ToC. It should have hosted additional training materials produced by all project partners and was identified as a resource to further support businesses in the “Experience” network in developing their low-season experiential tourism products and increase their confidence to invest in a low-season offer. Everything from its timing, usefulness and structure turned out to be a disaster. Halfway through the project the platform did not yet exist and at the final project steering group meeting, when training activities had ended and products were already on the market, this platform was still being populated. Looking at the causal chain linked to the learning platform in the ToC and discussing this element with project partners helped us gain an understanding from an internal perspective as to why the platform failed.

The lead partner highlighted that the learning platform had always been a vague concept in the application form, which explains why it was often the elephant in the room during previous steering group meetings. The vagueness of the concept, paired with the slowness of the lead partner to get the platform set-up contributed to its failure. However, what emerged from the discussion is that ultimately, the lack of cross-border coordination on populating it resulted in no partner taking responsibility for its delivery on time. Had it been better defined beforehand, with clear responsibilities agreed for each partner, its impact and outreach could have been much greater. The reluctancy to work collaboratively on this task was one of the biggest shortcomings within the project and the lack of collective ownership over the learning platform demonstrates that partners put much greater effort in achieving their own regional outputs as opposed to tasks requiring cross-border collaboration. Partners agreed that the Covid-19 pandemic which prevented most of the face-to-face meetings and chances to bond across the first two years of the project exacerbated the existing cross-cultural and cross-language challenges to cross-border collaboration.

Discussion

Participatory approaches to evaluation lie at the core of this study to explore how we can encourage a more formative culture of evaluation in tourism. The EU-Interreg programme in which “Experience” operates is an interregional cooperation programme which strives to reduce disparities in levels of development, growth, and quality of life across regions in Europe, by promoting policy learning and transfer. We argue that the very nature of the programme calls for more formative approaches to evaluation to facilitate such learning in a regional development context. Instead of the evaluation being solely an ex-post audit on performance, implementing a qualitative, participatory approach from the beginning supported partners in learning from mistakes and tackling issues as they arose along the way (Vanclay, Citation2015). Our study aligns with those supporting the integration of formative evaluations conducted qualitatively for greater learning opportunities (Bertella et al., Citation2021; Phi et al., Citation2018; Vanclay, Citation2015). We demonstrate how ToC can support evaluators in creating knowledge about the mechanisms and the process, to intervene before it is too late, and improve the design of future interventions. “Experience” ended in March 2023. Although the impacts of some of the large-scale outcomes may not be visible immediately, we can draw-up some conclusions from how project partners have benefitted from this evaluation approach and how it has served as a useful learning opportunity overall.

Ensuring flexibility and understanding the context

ToC is a useful tool to evaluate impacts of complex and multifaceted projects. Previous studies have discussed how evaluating impacts by reporting on numbers alone leads to assume a linearity and a degree of traceable causality which simply does not reflect the complex dynamics of a real-life project (Haarich et al., Citation2019; Vanclay, Citation2015; Warnholtz et al., Citation2022). Through ToC, we encouraged partners to critically reflect on the implicit rationale underpinning how they expected change to happen in their destination, creating causal links between project resources, activities, and outcomes. Our findings show that it is almost impossible to attribute change solely to a particular intervention, as these never run in isolation nor in a linear way. We identified multicausal pathways tracing how different activities, investments and unexpected outcomes that occurred throughout the project contributed towards the achievement of certain impact (Mayne, Citation2015; Phi et al., Citation2018). Mapping out these causal links and then reviewing the latter through ToC was instrumental to reflect on mistakes made throughout the project implementation, as well as events out of partners’ control, to evaluate what worked well, what did not and most importantly why.

ToC helps identify gaps in available data. Ex-post summative evaluations leave no space for project partners to intervene when things do not go according to plan, to ensure the project stays on track to deliver promised outcomes (Hachmann, Citation2011; Haarich et al., Citation2019; Warnholtz et al., Citation2022). By co-designing the nested ToCs, we became aware that partners were not collecting data to evaluate social impacts of the project, and that most partners were not comfortable with collecting and handling large amounts of data. Instead of using the evaluation to “catch partners out,” we had constructive conversations around why and how to fill those data gaps. We co-designed a residents’ survey to collect data around residents’ perceptions of tourism, and to understand how residents in pilot regions were impacted by the project activities. Conducting the evaluation ex-post would not have allowed us to witness nor acknowledge the change in partners attitudes towards the importance of collecting this type of data (Vanclay, Citation2015).

ToC helps capture evidence of how unexpected outcomes can affect an initial programme theory. Scarce attention has been given in the tourism literature to understand the multicausal process through which tourism interventions create impact (Dredge & Jamal, Citation2015) leaving the so called “black-box” of mechanisms, unopened (Phi et al., Citation2018). The Covid-19 pandemic affected the operationalisation of many of the project’s planned activities, for example the commissioning of infrastructure work, availability of industry partners, delivery of business trainings and the ability to collect data from visitors at the destination. When first co-creating and later revisiting the nested ToCs, we learned about how partners’ endeavours to offer training to businesses online instead of in person or collect data from locals attending “Experience” events allowed for new, unexpected outcomes to come about. For example, some partners decided to continue offering online training as businesses found it easier to attend. Moreover, many regions understood the pivotal role their residents could play in supporting tourism businesses when international travel stopped. ToC, being a process in continuous evolvement, rather than a finished product (Wigboldus & Brouwers, Citation2011), allowed us to identify what worked in particular circumstances and for our lead partner, it was useful to identify any corrective measures to tackle emerging outcomes (Mayne, Citation2015; Tindall, Citation2018).

Co-learning and creating project legacy

We framed the evaluation using a language and approach which was not discouraging for project partners, encouraging them to develop their capacity and reflect on how to improve existing assets and livelihood strategies in each pilot region. Previous studies have highlighted how tourism evaluations that do not involve locals have perpetuated a sense of marginalisation of local communities in receipt of the interventions (Burns, Citation2004; Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2011; Thomas, Citation2022.) Our findings illustrate how ToC was critical in triggering a sense of responsibility and ownership over the evaluation in project partners which helped them learn and reflect on certain shortcomings during the period of project closure when writing-up their evaluation reports. ToC helped us gather input and work alongside those implementing the project locally, to contextualise the evaluation to their needs, capacity and expectations.

Planning the evaluation through ToC fostered a sense of empowerment for project partners. Previous studies have argued that ensuring ownership and empowerment when conducting evaluations creates the precedents for change to last beyond the scope of a project (Pawson, Citation2013). On several occasions, partners expressed that the ToC process helped them feel more confident of how project outcomes were going to be achieved and raised awareness of the progress made along the way. Partners felt in charge of their evaluation which put us, as an evaluation team, in a role of trusted advisors, enhancing the lesson-learning process and further confirming how reciprocal learning benefits for both evaluators and project partners, strengthens the usefulness and learning outcomes of the evaluation itself (Bakırlıoğlu & McMahon, Citation2021). The benefit of adopting a participatory ToC approach is that co-learning developed naturally during the workshops, particularly during the final ToC workshop during project closure, when partners felt comfortable in reflecting freely on things they would do differently. This created a (more) horizontal and honest interaction amongst project partners and the research team of evaluators.

Developing nested ToCs with project partners was pivotal to improve our knowledge of programme theory and implementation theory (). Mayne (Citation2015) has discussed how nested ToCs are a means to dig deeper and uncover each partners’ narrative behind change (Rogers & Funnell, Citation2011). In doing so, we were able to examine project impacts from the perspective of those directly involved (OECD, Citation2012). Whilst reconciling and mapping out all partners’ views during one workshop was lengthy and somewhat messy, this iterative process of understanding pathways to change with partners (Taplin et al., Citation2013; Vogel, Citation2012) helped us unpack different interpretations of the project in each context. Our findings support the view that designing nested ToCs significantly strengthens the validity of the overall project aims and overarching ToC (Mayne & Johnson, Citation2015). Despite each partner following their own agenda, the nested ToCs offer support in evaluating the project as a whole and helped us conducted an evaluation which was context-sensitive and meaningful to all regions in the partnership.

ToC is a co-learning tool which creates lasting project legacies. Scholars have discussed how the lack of engagement with project partners and consequent lack of learning from evaluations is a root cause for the failure to achieve lasting project legacies (Bertella et al., Citation2021; Niavis et al., Citation2022), particularly in EU regional development projects (Stoffelen, Citation2018; Vanclay, Citation2015). Our findings suggest that evaluation can represent a valuable opportunity for learning if we transition from evaluating for to evaluating with project partners (Northcote et al., Citation2008; Sullivan & Stewart, Citation2006). Creating buy-in was often challenging, however, once partners were able to understand the benefits a ToC could bring to their evaluation, engagement occurred naturally. Whilst researchers have previously relied on interviews to build the ToC (e.g. Phi et al., Citation2018), or the Delphi method to gather wider stakeholder input (Northcote et al., Citation2008), workshops allowed partners to become active co-creators of their evaluation (Getz, Citation2019). In doing so, we experienced how evaluation methodologies that encourage co-learning and partner engagement have important consequences on the legacy of a project (Bakırlıoğlu & McMahon, Citation2021; Bertella et al., Citation2021; Park & Yoon, Citation2011). We found that as a participatory method of evaluation, ToC encouraged partners to take an active role in the development and implementation of the evaluation strategy but also in recognising the criticalities and things that could have been done better.

Barriers to working collaboratively in EU regional development interventions

Our findings suggest two main barriers experienced by partners when working on projects collaboratively. First, cultural differences play a part in how partners understand the concept of evaluation and their willingness to collaborate with one another. Whilst cultural variety and cross-border collaboration is considered crucial in EU regional development projects to maximise impact (Haarich et al., Citation2019), we found that working across cultures was not a real part of their agenda nor part of the reason for which they joined the partnership. This explains why partners successfully achieved individual outputs identified in their nested ToCs for which they had control over, but partially failed the achievement of collective outputs such as the learning platform, that required collective effort, without a clear regional benefit. Cross-border collaborations often exist to simply “follow the pot of money” (Dredge, Citation2001, p. 374), rather than as a real effort to work together to maximise impacts in the form of policy transfer and learning opportunities. Nevertheless, acknowledging this was an important step which led to more honest conversations with project partners.

The lack of collaboration was not linked to a lack of interest in working collaboratively. An additional burden was the heavy and arguably redundant bureaucracy linked to justifying the need to work together. Often it was easier to work independently than to acquire enough evidence to justify that activities or meetings were useful for the partnership. Our findings expand on the previous study conducted by Shepherd and Ioannides (Citation2020) on the use of EU-INTERREG funding in tourism interventions by suggesting that the lack of collaboration in large cross-border projects is linked to the excessive need to justify activities and time spent working collaboratively that is satisfactory to funders.

Responding to Shepherd and Ioannides (Citation2020) call for a better management and design of cross-border collaboration projects, we believe that our attempt to take a step back from the rhetoric of producing evaluations for the sake of proving any, even false impact, on paper, represents a step in the right direction. We suggest that implementing ToC from the beginning, as a tool to co-design, co-evaluate and ultimately co-learn, can promote a more meaningful, bottom-up evaluation approach anchored in local context (through the nested ToCs), whilst also feeding into a shared vision of change developed through the overarching ToC. By encouraging partners in being honest about their agendas and working together to evidence and achieve impact which is important to them, we can foster true learning opportunities and policy transfer. We believe this approach can contribute to addressing some of the profound incongruencies present in most large, heavily funded cross-border partnerships.

Conclusion

This study makes a methodological contribution to qualitative, formative evaluation approaches in the field of tourism interventions (Font et al., Citation2021) We applied ToC as a complexity-appropriate evaluation tool using a participatory approach. Building on the need to better evidence the impact of tourism interventions (Getz, Citation2019, Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2011), we propose ToC as a method to engage project partners in the co-design of the evaluation strategy with valuable learning opportunities for better policy transfer and lasting project legacies. We applied ToC to evaluate a large, cross-border tourism project implemented from the very early stages of project implementation, and in doing so, we have demonstrated its value and flexibility when dealing with complex emergent outcomes, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. Implementing a participative, formative approach to evaluation such as the one offered by ToC can strengthen the way we report on impacts of complex tourism interventions by fostering a co-learning evaluation environment which is able to capture impact more than indicators alone.

ToC is a tool that supports the evaluation in all phases of the project: planning, implementation and closure. As we showed in the results, devising an initial ToC helps identify a programme theory and question the assumptions around how and why we expect change to occur through planned activities. During an interim stage, we learned how corrective measures can be applied to prevent failure. Moreover, we showed how timely results collected through interim evaluation can help steer project activities and decisions to maximise outcomes. Lastly, when coming towards the end of the project, revisiting the original ToC and reflecting on deviations of it offered project partners a chance to reflect on what went well, what could have worked better and what were the lessons learned from the project to adopt in their destinations management daily practices.

We found ToC to be a highly accessible tool for non-evaluation experts. This had positive repercussions on partners’ understanding the benefits of collecting data to inform decisions, especially in those areas where this type of data had never been collected before locally. Approaching the evaluation with ToC was crucial to create an on-going iterative process of evaluation in which partners felt fully involved in from the outset, by putting them in charge of their evaluation and strengthening their capacity over time. Establishing an honest dialogue throughout project implementation, to create a realistic and shared vision of change and then to collect the evidence necessary to test whether initial assumptions hold true, increased the level of shared accountability and willingness to learn about data collection methods and make better use of data to inform decisions locally.

Current findings show that the method has good potential in creating engagement even when implemented remotely, as was often the case during Covid-19 restrictions. It is a useful tool to co-design an evaluation strategy and monitor progress along the way (as shown in this study), and also to co-design better projects from the outset. Finally, for large projects with multiple partners and complex interventions, we strongly recommend utilising an overarching ToC (as shown in ) and supporting this with the more detailed, nested ToCs. In our case, this proved extremely useful to evidence the diverse range of impacts happening simultaneously across the partnership but also to encourage partners to take full ownership of their ToC, resulting in a strong sense of empowerment.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by EU funds provided by FCE – French Channel England- Interreg ‘Experience’ project. This work is also partially financed by Portuguese Funds provided by FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, Portugal – through project UIDB/04020/2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Luigina Jessica Montano

Luigina Jessica Montano, PhD researcher at the University of Surrey, interested in evidence-informed policy-making, evaluation and sustainable tourism.

Xavier Font

Xavier Font, Professor of Sustainability Marketing at the University of Surrey. Interested in sustainable tourism marketing.

Corinna Elsenbroich

Corinna Elsenbroich, Reader of Computational Modelling in Social and Public Health Science at the University of Glasgow. Interested in evaluation methods.

Manuel Alector Ribeiro

Manuel Alector Ribeiro, Senior Lecturer of Tourism Management at the University of Surrey, interested in social impacts assessment and sustainable tourism.

References

- Allen, R., Bicket, M., & Junge, K. (2019). CECAN Evaluation and Policy Practice Note (EPPN) for policy analysts and evaluators – Using complexity and theory of change to transform regulation: A complex theory of change for the Food Standards Agency’s ‘Regulating Our Future’ programme. University of Surrey.

- Baral, R., & Rijal, D. P. (2022). Visitors’ impacts on remote destinations: An evaluation of a Nepalese mountainous village with intense tourism activity. Heliyon, 8(8), e10395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10395

- Bakırlıoğlu, Y., & McMahon, M. (2021). Co-learning for sustainable design: The case of a circular design collaborative project in Ireland. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123474

- Bertella, G., Lupini, S., Romanelli, C. R., & Font, X. (2021). Workshop methodology design: Innovation-oriented participatory processes for sustainability. Annals of Tourism Research, 89, 103251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103251

- Breuer, E., De Silva, M. J., Shidaye, R., Petersen, I., Nakku, J., Jordans, M. J. D., Fekadu, A., & Lund, C. (2016). Planning and evaluating mental health services in low-and middle-income countries using theory of change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(s56), s55–s62. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153841

- Burns, P. M. (2004). Tourism planning: A third way? Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.001

- Byrne, D. (2013). Evaluating complex social interventions in a complex world. Evaluation, 19(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013495617

- Clarke, G. M., Conti, S., Wolters, A. T., & Steventon, A. (2019). Evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions using routine data. bmj, 365.

- Davies, R. (2018). Representing theories of change: Technical challenges with evaluation consequences. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 10(4), 438–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2018.1526202

- Dillon, B. (2019). CECAN Webinar: Theory of Change – Getting the most out of it - Insights from a Practitioner | CECAN. https://www.cecan.ac.uk/videos/cecan-webinar-theory-change-getting-most-out-it-insights-practitioner

- Douthwaite, B., & Hoffecker, E. (2017). Towards a complexity-aware theory of change for participatory research programs working within agricultural innovation systems. Agricultural Systems, 155, 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.04.002

- Dredge, D. (2001). Local government tourism planning and policy-making in New South Wales: Institutional development and historical legacies. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(2-4), 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500108667893

- Dredge, D., & Jamal, T. (2015). Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tourism Management, 51, 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.002

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2011). Stories of practice: Tourism policy and planning. Ashgate.

- Dyson, A., & Todd, L. (2010). Dealing with complexity: Theory of change evaluation and the full-service extended schools initiative. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 33(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2010.484606

- Eckardt, C., Font, X., & Kimbu, A. (2020). Realistic evaluation as a volunteer tourism supply chain methodology. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(5), 647–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1696350

- Eguren, R. (2011). Theory of change: A thinking and action approach to navigate in the complexity of social change processes. Democratic Dialogue Regional Project, the Regional Centre for Latin America and the Caribbean UNDP and Humanistic Institute for Development Cooperation (HIVOS).

- Fitzpatrick, J. L., Sanders, J. R., & Worthen, B. R. (2011). Program evaluation: Alternative approaches and practical guidelines (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Font, X., Torres-Delgado, A., Crabolu, G., Palomo Martinez, J., Kantenbacher, J., & Miller, G. (2021). The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European Tourism Indicator System. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1910281

- Gasparini, M. L., & Mariotti, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism indicators as policy making tools: Lessons from ETIS implementation at destination level. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1968880

- Getz, D. (2019). Shifting the paradigm: A theory of change model. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 11(sup1), s19–s26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1556859

- Gregory-Smith, D., Wells, V. K., Manika, D., & McElroy, D. J. (2017). An environmental social marketing intervention in cultural heritage tourism: A realist evaluation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 1042–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1288732

- Haarich, N. S., Salvatori, G., & Toptsidou, M. (2019). Evaluating Interreg programmes. The challenge of demonstrating results and value of European Territorial Cooperation, Spatial Foresight Brief 2019:10. Luxembourg.

- Hachmann, V. (2011). From mutual learning to joint working: Europeanization processes in the INTERREG B programmes. European Planning Studies, 19(8), 1537–1555. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.594667

- Højlund, S. (2015). Evaluation in the European Commission: For accountability or learning? European Journal of Risk Regulation, 6(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1867299X00004268

- Ioannides, D., Nielsen, P. Å., & Billing, P. (2006). Transboundary collaboration in tourism: The case of the Bothnian Arc. Tourism Geographies, 8(2), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680600585380

- Kitamura, Y., Karkour, S., Ichisugi, Y., & Itsubo, N. (2020). Evaluation of the economic, environmental, and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Japanese tourism industry. Sustainability, 212(24), 10302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410302

- Knippschild, R., & Vock, A. (2017). The conformance and performance principles in territorial cooperation: A critical reflection on the evaluation of INTERREG projects. Regional Studies, 51(11), 1735–1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1255323

- Liberato, D., Alén, E., Liberato, P., & Domínguez, T. (2018). Governance and cooperation in Euroregions: Border tourism between Spain and Portugal. European Planning Studies, 26(7), 1347–1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1464129

- Maini, R., Mounier-Jack, S., & Borghi, J. (2018). How to and how not to develop a theory of change to evaluate a complex intervention: Reflections on an experience in the Democratic Republic of Congo. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000617. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000617

- Mathison, S. (Ed.). (2005). Encyclopedia of evaluation. Sage.

- Mayne, J. (2015). Useful theory of change models. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 30(2), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.230

- Mayne, J., & Johnson, N. (2015). Using theories of change in the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health. Evaluation, 21(4), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389015605198

- Morra Imas, L. G., & Rist, R. C. (2009). The road to results: Designing and conducting effective development evaluations. The World Bank.

- Niavis, S., Papatheochari, T., Koutsopoulou, T., Coccossis, H., & Psycharis, Y. (2022). Considering regional challenges when prioritizing tourism policy interventions: evidence from a Mediterranean community of projects. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 663–684.

- Northcote, J., Lee, D., Chok, S., & Wegner, A. (2008). An email-based Delphi approach to tourism program evaluation: Involving stakeholders in research design. Current Issues in Tourism, 11(3), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802140315

- OECD. (2012). Evaluating tourism policies and programmes. In OECD tourism trends and policies 2012.

- Park, D. B., & Yoon, Y. S. (2011). Developing sustainable rural tourism evaluation indicators. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(5), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.804

- Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. SAGE.

- Peeters, P., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C., Eijgelaar, E., Hartman, S., Heslinga, J., Isaac, R., Mitas, O., Moretti, S., Nawijn, J., Papp, B. and Postma, A. (2018). Research for TRAN Committee - Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels.

- Phi, G. T., Whitford, M., & Reid, S. (2018). What’s in the black box? Evaluating anti-poverty tourism interventions utilizing theory of change. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(17), 1930–1945. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1232703

- Rogers, P., & Funnell, S. (2011). Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models. Jossey-Bass.

- Shepherd, J., & Ioannides, D. (2020). Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Useful funds, disappointing framework: Tourism stakeholder experiences of INTERREG. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1792339

- Stoffelen, A. (2018). Tourism trails as tools for cross-border integration: A best practice case study of the Vennbahn cycling route. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.09.008

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Tourism and cross-border regional development: Insights in European contexts. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 1013–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1291585

- Sullivan, H., & Stewart, M. (2006). Who owns the theory of change? Evaluation, 12(2), 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389006066971

- Taplin, D. H., Clark, H., Collins, E., & Colby, D. C. (2013). Theory of change. Technical papers: A series of papers to support development of theories of change based on practice in the field. ActKnowledge, New York NY, USA.

- Thomas, R. (2022). Affective subjectivation or moral ambivalence? Constraints on the promotion of sustainable tourism by academic researchers. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(9), 2107–2120. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1770262

- Tindall, D. (2018). The importance of context and why i now do data parties. In K. Hutchinson (Ed.), Evaluation failures: 22 tales of mistakes made and lessons learned (pp. 133–138). SAGE.

- Twining-Ward, L. R., Messerli, H., Miguel Villascusa, J., & Sharma, A. (2021). Chapter 2: Tourism Theory of Change: A tool for planners and developers. In A. Spencely (Ed.) Handbook for sustainable tourism practitioners (pp. 13–31). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Vanclay, F. (2015). The potential application of qualitative evaluation methods in European regional development: Reflections on the use of Performance Story Reporting in Australian natural resource management. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1326–1339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.837998

- Vogel, I. (2012). Review of the use of ‘Theory of Change’ in international development. DFID Review Report. London: Department for International Development.

- Waas, T., Hugé, J., Block, T., Wright, T., Benitez-Capistros, F., & Verbruggen, A. (2014). Sustainability assessment and indicators: Tools in a Decision-making strategy for sustainable development. Sustainability, 6(9), 5512–5534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6095512

- Walton, M. (2014). Applying complexity theory: A review to inform evaluation design. Evaluation and Program Planning, 45, 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.04.002

- Warnholtz, G., Ormerod, N., & Cooper, C. (2022). The use of tourism as a social intervention in indigenous communities to support the conservation of natural protected areas in Mexico. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(11) , 2649–2664. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1860069

- Weiss, C. H. (1998). Evaluation methods for studying programs and policies. Pearson College Division.

- Wigboldus, S., & Brouwers, J. (2011). Rigid plan or vague vision: How precise does a ToC need to be? Hivos E-dialogues. http://www.hivos.nl/eng/HivosKnowledgeProgramme/Themes/Theory-ofChange/E-dialogues/E-dialogue-2.