Abstract

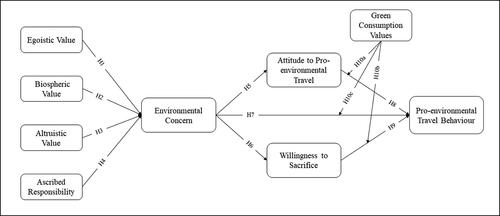

Generation Z (Gen Z) is widely considered the most eco-conscious generation. Nonetheless, there is a dearth of empirical research on this generation’s pro-environmental travel behaviour. To address this gap, the present research aims to investigate the interplay of values (egoistic, biospheric, altruistic) and ascribed responsibility in driving the pro-environmental travel behaviour of Gen Z through the moderating role of green consumption values. Data were collected from 362 British Gen Z tourists using a structured questionnaire and analysed using SmartPLS. Results revealed that values and ascribed responsibility significantly influence environmental concern, which, in turn, affects attitudes, willingness to sacrifice, and pro-environmental travel behaviour. Furthermore, positive attitudes and willingness to sacrifice significantly affect pro-environmental travel behaviour. In addition, green consumption values moderate the relationship between attitude and willingness to sacrifice concerning pro-environmental travel behaviour. Applying a generational approach, this study enriches the theoretical understanding of tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour and highlights effective ways to promote sustainable behaviour among younger travellers.

Introduction

Gen Z (following Millennials and preceding Generation Alpha) is typically regarded as comprising those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s (Corey & Grace, Citation2019). According to estimates, Gen Z comprises approximately 32% of the worldwide population (World Economic Forum, Citation2018), and is the youngest generational cohort of active consumers, making them one of the tourism industry’s fastest-growing segments and a crucial target market.

According to Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie (Citation2019), future tourism demand is projected to be driven by demographics and future travel patterns that are unique to different generations. Understanding the consumption tendencies of different generations and determining their level of awareness with respect to sustainable consumption behaviours is of paramount importance in a globalised world (Haddouche & Salomone, Citation2018). Prior research suggests that regarding the valuing of sustainability, Gen Z consumer behaviour and lifestyle choices diverge from those of preceding generations (e.g., Prayag et al., Citation2022; Seyfi et al., Citation2023; Sharma et al., Citation2023). According to a Global Web Index survey, 64% of Gen Z are willing to pay more for “eco-friendly” products (Bergamini, Citation2020). Wee (Citation2019) also showed that Gen Zers are frequently depicted as socially and ecologically conscientious, with strong engagement in sustainable tourism practices and consumption. Similarly, Seyfi et al. (Citation2023) argue that Gen Zers’ concern for the environment is reflected in their travel habits. More recent studies also demonstrated that Gen Zers are more concerned about environmental issues than previous generations (Prayag et al., Citation2022). A study conducted by Booking.com (Citation2019) on the Destination Gen Z project also showed that Gen Zers are interested in eco-friendly travel, sustainable hotel practices and contributions to local communities. This highlights the need to create a better and more precise understanding of the driving factors of the pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) of this cohort—the key focus of this study.

Nonetheless, most tourism studies concerning Gen Z are either conceptual or have not adequately investigated the determinants of this cohort’s PEBBy applying a generational approach (Strauss & Howe, Citation2009), the current study contributes to pro-environmental research in several ways. First, this study develops and empirically examines an integrated model of values (egoistic, biospheric, altruistic) and ascribed responsibility in driving pro-environmental travel behaviour of Gen Zers, thereby extending the study developed by Verma et al. (Citation2019). Secondly, given that this study is focused on the Gen Z cohort, we add empirical clarity to the factors that trigger this cohort’s PEB by including willingness to sacrifice as a driving mechanism between environmental concern and pro-environmental travel behaviour, complementing previous studies (Verma et al., Citation2019). Thirdly, we estimated the effect of attitudes concerning green travel, willingness to sacrifice and environmental concern on Gen Zers’ PEB through the moderating role of green consumption values, which may provide greater clarity in explaining how green consumption values shape this cohort’s pro-environmental travel behaviour. Additionally, this study offers destination managers and marketers useful information to better understand the determinants of Gen Zer’s PEB and help them develop better strategies for promoting sustainable tourism practices and consumption.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour

Pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) is broadly defined as behaviours that not only limit negative impacts of an individual’s actions on the natural environment, but also promote or result in sustainable natural resource use (e.g., recycling, litter pick-up, saving energy, and volunteering for conservation projects) (Wu et al., Citation2021). Similarly, tourists’ PEB is depicted as behaviours that encourage environmental conservation and prevent harming natural ecosystems at a destination (e.g., selecting environmentally friendly travel modes and products) (Rezapouraghdam et al., Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2021) thereby contributing to the sustainable development of tourist destinations (Xu et al., Citation2023). Tourists’ PEB is often used synonymously with environmentally responsible behaviour (Erul et al., Citation2022), environment-friendly behaviour, eco-friendly behaviour, environmental conservation behaviour (Wang & Zhang, Citation2020), and travellers’ green behaviour (Verma et al., Citation2019). Due to the difficulty of persuading tourists to engage in PEB, much work has been devoted to elucidating the drivers underpinning tourists’ PEB (Wang & Zhang, Citation2020).

According to Wang and Zhang (Citation2020), promoting tourists’ participation in PEBs is a significant challenge. Internal, external, and demographic variables have been identified as key determinants of PEB, with internal variables garnering the most attention (Wu et al., Citation2021). While a preponderance of the early research tended to concentrate primarily on cognitive factors (e.g., environmental knowledge, environmental awareness, and personal norms) within the context of the norm activation model (NAM), theory of planned behaviour (TPB), and value-belief-norm (VBN) theory, recent studies have criticised overly simplistic models for failing to fully predict PEBs due to the complexity of PEBs (Rezapouraghdam et al., Citation2021). Hence, recent research has focused on several affective factors (e.g., place attachment, subjective well-being, and anticipated emotion). These factors were found to be strong predictors of tourists’ PEB (Xu et al., Citation2023).

Generational approach to pro-environmental behaviour

Generational theory defines a generation as a group of people born within a specific time period who share common experiences and values that shape lifestyles and attitudes (Strauss & Howe, Citation2009), ultimately affecting consumer behaviour. Researchers have applied this lens to study tourist behaviour, exploring value perceptions (Gardiner et al., 2015), travel demand (Cleaver & Muller, Citation2002) and place attachment across generational cohorts (Chen et al.,Citation2022). Recent studies have focused on generational differences in pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) and found that younger generations like Gen Z are more environmentally conscious and engaged (Song et al., Citation2020). Research in tourism has shown that Gen Z travellers prioritise sustainable practices and environmental concerns (e.g., Prayag et al., Citation2022; Seyfi et al., Citation2023; Sharma et al., Citation2023), with internal factors like awareness, responsibility, and external factors like social media influencing their pro-sustainable behaviours (Salinero et al., Citation2022). Prayag et al. (Citation2022) identified inter- and intra-generational differences in environmental attitudes and travel behaviours among visitors to the Canterbury region of New Zealand, with Gen Z tourists demonstrating a higher inclination towards sustainable practices such as resource-saving and buying local food. Similarly, Sharma et al. (Citation2023) revealed that Gen Z travellers exhibit higher levels of generative concerns, prosocial attitudes, green consumption values, and engagement in food waste reduction behaviours compared to older travellers.

Values and pro-environmental travel behaviour

According to Schwartz (Citation1992), a value is defined as “a desirable trans-situational [relatively stable, manifesting itself in different situations] goal varying in importance, which serves as a guiding principle in the life of a person or other social entity (p. 21).” Values consist of beliefs about the desirability of certain end-states, transcend contexts, and serve as guiding principles for judgment and behaviour (Steg et al., Citation2013). Values are important life objectives or standards that guide individuals’ attitudes and behaviours (Rokeach, Citation1973).

Research confirms that values play a substantial role in PEB engagement (De Groot & Steg, Citation2008). People are responsive to messages aligning with their values, as they are sensitive to consequences affecting their beliefs (Dietz & Stern, Citation1995). Values influence behaviour through beliefs, environmental concerns, and selective attention to information, shaping intentions and behaviours. Previous studies emphasise the role of values in prioritising environmental concerns (Han et al., Citation2015). Based on Schwartz’s universal values, Stern et al. (Citation1993) identified egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations underlying environmental concern. Egoistic values prioritise individual outcomes, altruistic values focus on others’ welfare, and biospheric values emphasise the environment (De Groot & Steg, Citation2009). These values are connected to PEB through behaviour-specific beliefs, norms, and intentions (e.g., Stern, Citation2000). Empirical evidence supports the distinction between these values (De Groot & Steg, Citation2008).

Studies have examined how these values relate to PEB (De Groot & Steg, Citation2008; Van Doorn et al., Citation2015). Values directly enhance environmental concern, norms, and attitudes, leading to positive environmental behaviour (Choi et al., Citation2015; Van Riper & Kyle, Citation2014). This aligns with Schwartz and Bilsky (Citation1990) observation that values serve as standards for evaluating actions, people, and events.

Individuals hold varying degrees of egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric values, all of which can serve as foundations for PEB (De Groot & Steg, Citation2009). Acting on egoistic values may conflict with PEB due to costs outweighing benefits. Altruistic and biospheric values promote PEB due to societal and environmental benefits. Stronger altruistic and/or biospheric values are generally associated with more PEB. While connected, altruistic and biospheric values have distinct implications in different environmental contexts. The value-belief-norm (VBN) theory treats these value orientations as separate variables in analysing environmental behaviour (Steg & de Groot, Citation2012).

Hypotheses development

Egoistic values and environmental concern

An egoistic value orientation prioritises personal gain in decision-making. Previous research indicates that egoistic values positively influence environmental behaviour (Stern et al., Citation1993; Verma et al., Citation2019) because people prefer a specific environmental level given anticipated benefits (i.e., utility increase). This is in line with Stern et al. (Citation1999) VBN theory. Egoistic values play a key role when individual behavioural costs of pro-environmental actions are high (Lindenberg & Steg, Citation2007). Concerns with gain override norms as expenses increase (Diekmann & Preisendorfer, Citation2003). Individuals with a strong egoistic orientation consciously evaluate costs and benefits of their behaviour (Verma et al., Citation2019). The study of Verma et al. (Citation2019) found a positive relationship between egoistic values and environmental concern and attitudes toward green hotels. Hence, in line with the VNB theory, egoistic values may influence Gen Zers’ environmental concern. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 1: Egoistic values positively influence Gen Zers’ environmental concern.

Biospheric values and Gen Zers’ environmental concern

Stern and Dietz (Citation1994) defined biospheric values as judging phenomena based on their impact on ecosystems and the biosphere. Biospheric values are categorized under the universalism value orientation, which includes concern for the well-being of people, nature, and the wider society (Schwartz, Citation2012). The value-belief-norm (VBN) theory (Stern et al., Citation1999) states that biospheric values play a crucial role in predicting environmental concern and sustainable behaviour. These values influence beliefs about environmental protection’s importance, which, in turn, shape behavioural norms. Biospheric values predict norms and intentions for sustainable behaviour, as they encompass diverse motivations for such actions (Steg et al., Citation2011). High biospheric values are associated with environmental concern and decision-making based on ecosystem costs/benefits (Steg et al., Citation2011). Empirical evidence links biospheric values and environmental self-identity to moral obligations for pro-environmental behaviour (Verma et al., Citation2019). Various studies have shown positive correlations between biospheric values and environmentally responsible behaviour, such as environmental activism, energy conservation, local product consumption, and responsible tourism (Han et al., Citation2015; Verma et al., Citation2019). For example, Verma et al. (Citation2019) found that biospheric values strongly predicted consumers’ attitudes toward environmentally friendly hotels, consistent with Han et al.’s (Citation2015) findings. Based on the discussion above and the VBN theory, we propose that cultivating biospheric values in Generation Zers can positively impact their environmental concern and propose that:

Hypothesis 2: Biospheric values positively influence Gen Zers’ environmental concern.

Altruistic values and Gen Zers’ environmental concern

According to Schwartz and Bilsky (Citation1987), altruism is a personal value system with a significant impact on behaviour. Altruistic values are characterised by a concern for others’ well-being (Stern et al., Citation1993). It is believed that promoting altruistic principles in individuals is in the best interest of society for addressing environmental concerns (Heberlein, Citation1972). Research indicates that altruistic values play a crucial role in shaping environmental beliefs (De Groot & Steg, Citation2008; Verma et al., Citation2019). For example, Verma et al. (Citation2019) found that altruism positively influences tourists’ intention to choose green hotels, aligning with the VBN framework. Studies also demonstrate that tourists with strong altruistic values tend to have positive attitudes toward the natural environment and engage in pro-environmental behaviour (Kim & Stepchenkova, Citation2020). Altruistic values influence decision-making based on the costs/benefits to the environment, consistent with the VBN theory. Based on this evidence, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: Altruistic values positively influence Gen Zers’ environmental concern.

Ascribed responsibility and Gen Zers’ environmental concern

According to the VBN theory (Stern et al., Citation1999), ascribed responsibility is a crucial precursor to norm activation and PEB. Ascribed responsibility refers to a personal sense of obligation and a feeling of responsibility for the negative consequences of not acting pro-socially (De Groot & Steg, Citation2009). Verma et al. (Citation2019) found that individuals who perceive their negative impact on the environment and share a sense of responsibility are more likely to engage in environmentally friendly behaviour. However, the strength of this relationship tends to weaken when people perceive a low level of ascribed responsibility (De Groot & Steg, Citation2009). Moreover, individuals with prior knowledge of environmental consequences are more inclined to participate in green consumption activities, such as purchasing green products, staying at green hotels, or supporting sustainable cultural heritage tourism (Han et al., Citation2015; Megeirhi et al., Citation2020; Verma et al., Citation2019). The VBN theory suggests that individuals with a high level of ascribed responsibility for the environment are more likely to activate norms and engage in pro-environmental behaviours. Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 4: Ascribed responsibility values positively influence Gen Zers’ environmental concern.

Environmental concern, attitudes, willingness to sacrifice and pro-environmental travel behaviour

Environmental concern refers to “the degree to which people are aware of problems regarding the environment and support efforts to solve them and or indicate the willingness to contribute personally to their solution” (Dunlap & Jones, Citation2002, p. 485). Most researchers have considered environmental concern as a general attitude that focuses on the affective and cognitive evaluations of environmental problems (Lou & Li, Citation2023). Consistently, this study operationalises environmental concern as a general attitude towards environmental problems and humans’ role in abusing/protecting nature. The literature positions environmental concern as a major determinant of sustainable consumer behaviour (see Elhoushy & Lanzini, Citation2021). Thus, it is argued that Gen Zers who possess a high level of environmental concern will demonstrate a stronger positive attitude towards pro-environmental travel, a greater willingness to sacrifice, and engagement in pro-environmental travel behaviours.

Environmental concern and attitudes towards pro-environmental travel

Prior studies have consistently found a positive relationship between individuals’ level of environmental concern and their attitudes and intentions towards PEB (Verma et al., Citation2019). This is also consistent with the VBN theory (Stern et al., Citation1999), which posits that individuals’ PEB is determined by their values, beliefs, and social norms. The cognitive hierarchy model (Homer & Kahle, Citation1988) further supports this idea by suggesting that abstract cognitions, such as values and beliefs, influence more specific cognitions, such as attitudes, which, in turn, lead to behaviour (Han et al., Citation2019). Thus, it is expected that higher environmental concern among Gen Zers will be associated with more positive attitudes towards pro-environmental travel. Based on this reasoning, we propose that:

Hypothesis 5: Environmental concern positively influences Gen Zers’ attitudes towards pro-environmental travel.

Environmental concern and willingness to sacrifice

Environmental concern is theorised to predict willingness to sacrifice for the environment, which refers to “the extent to which individuals’ decisions will take into account the well-being of the environment, even at the expense of immediate self-interest, effort, or costs” (Davis et al., Citation2011, p. 259). The “willingness” to sacrifice is distinguishable from environmental concern and attitude as it maintains a conative element (Verma et al., Citation2019). Empirically, previous studies showed that environmental concern significantly increases willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment. Willingness to sacrifice is positively correlated with education, income, and environmental involvement, while it is negatively correlated with age (Gelissen, Citation2007). In line with the VBN theory, it is expected that Gen Zers who hold strong environmental values and beliefs will be more likely to develop normative expectations of acting in a pro-environmental manner, which in turn will increase their willingness to sacrifice for the environment. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 6: Environmental concern positively influences Gen Zers’ willingness to sacrifice.

Environmental concern and pro-environmental travel behaviour

Lou and Li (Citation2023) discovered that environmental concern, as a general attitude, is a significant predictor of pro-environmental behaviours. However, previous meta-analyses examining the link between environmental concern and PEB have revealed a weak correlation, creating what is known as the "environmental concern-behaviour gap" (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). The VBN theory posits that behaviour can be directly influenced by values, beliefs, and norms, without necessarily being mediated by attitudes or intentions. When environmental concern was integrated into the VBN theory, it exhibited a notable significant direct effect on behaviour (Poortinga et al., Citation2016). Other studies also demonstrated that environmental concern influenced green purchasing behaviour (Mostafa, Citation2007), and environmental commitment was positively related to past green behaviours and future intentions (Davis et al., Citation2011). Therefore, it is expected that environmental concern will be directly associated with Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: Environmental concern positively influences Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour.

Attitude towards pro-environmental travel and Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour

Attitude refers to “the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation or appraisal of the behaviour in question” (Ajzen, Citation1991, p. 188). Many studies examined consumer attitudes towards sustainable consumer behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2021). For example, Ru et al. (Citation2018) differentiated attitudes into experiential attitudes (emotional aspects) and instrumental attitudes (functional aspects) and found that both types are associated with green travel intentions. Similarly, Han et al. (Citation2010) found that attitudes positively influenced individuals’ intention to stay at a green hotel. Han et al. (Citation2019) also revealed that attitudes had a significant impact on buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises. Consistently, in non-travel contexts, attitudes were positively related to intentions to buy green products and organic clothing (Varshneya et al., Citation2017). However, the attitude-behaviour gap is prevalent across contexts. For example, Juvan and Dolnicar (Citation2014) found that customers who actively engage in environmental protection do not necessarily maintain sustainable behaviours during holidays. The current study attempts to address the attitude-behaviour gap in the context of pro-environmental travel by examining the role of green consumption values on travel behaviours among Gen Zers (see H10). Taken together, this study argues that positive evaluations of pro-environmental travel (e.g., being good, ethical, and beneficial) will inform Gen Zers’ travel behaviour. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 8: Attitudes towards pro-environmental travel positively influence Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour.

Willingness to sacrifice and Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour

As expected, willingness to sacrifice reflects individuals’ cognitive focus on the environment, even if it means sacrificing personal gains. In the context of travel, this can be seen when individuals choose to pay premium prices for green hotels, stay in less convenient locations, or engage in behaviours such as towel reuse (Rahman & Reynolds, Citation2016). Willingness to sacrifice is commonly measured from an economic/financial perspective, such as individuals’ readiness to pay more for environmentally friendly services or products (Gelissen, Citation2007; Stern, Citation2000). Within the VBN theory, willingness to sacrifice is influenced by travellers’ values, beliefs, and norms related to environmental protection. This suggests that behaviour can be directly influenced by these factors without the need for attitude or intention mediation. For example, Rahman and Reynolds (Citation2016) found that paying more for environmentally friendly options may be driven by individuals’ connection with or love of nature. Similarly, willingness to sacrifice has been shown to significantly impact visitors’ pro-environmental intentions in museums (Verma et al., Citation2019) and intentions to purchase ecological tourism alternatives. However, in the specific context of waste reduction and recycling intentions among young vacationers, willingness to sacrifice primarily influenced personal norms rather than directly impacting intentions (Han et al., Citation2018). Therefore, willingness to sacrifice for the environment may stem from individuals’ personal values, beliefs, and norms, ultimately driving their pro-environmental travel behaviour. Based on these insights, this study hypothesizes that Gen Zers’ willingness to sacrifice will positively correlate with their pro-environmental travel behaviour. By incorporating the VBN theory into the analysis, a deeper understanding of the underlying factors driving willingness to sacrifice, and pro-environmental travel behaviour can be achieved. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 9: Willingness to sacrifice positively influences Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour.

The moderating role of green consumption values

Green consumption values refer to individuals’ inclination to express their commitment to environmental protection through their purchasing and consumption habits (Haws et al., Citation2014). Those with stronger green consumption values prioritize resource conservation at both personal and environmental levels (Haws et al., Citation2014; Yan et al., Citation2021). Previous research has highlighted the importance of green consumption values in shaping pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs), although often indirectly through constructs like attitude. For example, Varshneya et al. (Citation2017) found that attitudes toward organic clothing partially mediate the relationship between green consumption values and purchase intentions among young consumers. Similarly, green consumption values impact green attitudes and intentions through their influence on green trust (Bailey et al., Citation2016). Additionally, green consumption values are believed to play a moderating role. Yan et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that individuals with high green values are more susceptible to the effect of power on green consumption. Based on this rationale, it is anticipated that green consumption values have a moderating function in the context of pro-environmental travel. When green consumption values are high, they strengthen the relationships between pro-environmental travel behaviour and consumers’ attitudes, willingness to sacrifice, and environmental concern, compared to when green consumption values are low. This proposition is based on two lines of reasoning. Firstly, individuals with strong green consumption values are inclined to protect resources by avoiding waste and using only what is necessary (Haws et al., Citation2014). However, in consumption settings, individuals may assign different values or weights to their motives, leading to varying levels of engagement in sustainable behaviours (Elhoushy, Citation2020). Secondly, Gen Zers are expected to engage in behaviours that align with their values and express their environmental concern (Elhoushy, Citation2020). Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis10a: Green consumption values moderate the relationship between attitudes towards pro-environmental travel and pro-environmental travel behaviour, such that the relationship is stronger when green consumption values are high.

Hypothesis 10b: Green consumption values moderate the relationship between willingness to sacrifice and green travel behaviour, such that the relationship is stronger when green consumption values are high.

Hypothesis 10c: Green consumption values moderate the relationship between environmental concern and pro-environmental travel behaviour, such that the relationship is stronger when green consumption values are high.

Methods

Measures, data collection and sampling

To ensure the content validity of this study, previously validated scales were used to measure each construct (). The survey questionnaire consisted of 39 items and nine constructs, as shown in . The items for the three values dimensions were adapted from Riper and Kyle (2014) and Megeirhi et al. (Citation2020) and measured on a 5-point Likert scale of importance. Ascribed responsibility was measured with three items using the scale from De Groot and Steg (Citation2009) and Landon et al. (Citation2018) on a 5-point Likert scale of agreement. Environmental concerns were measured with four items adapted from Cordano et al. (Citation2011) and Han et al. (Citation2015). Attitude about pro-environmental travel was measured with four items adapted from Azjen (1991), Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1980), and Han et al. (Citation2015). Willingness to sacrifice was captured with four items adapted from Davis et al. (Citation2011). Gen Zers’ PEB was measured with five items adapted from Han et al. (Citation2015). Attitudes, willingness to sacrifice, and PEB were measured on a 5-point Likert scale of agreement.

Table 1. Construct reliability and convergent validity

The questionnaire was designed and hosted online using Qualtrics. Data were collected in June 2022 through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), which has demonstrated acceptable data reliability for assessing PEB or intentions to use environmentally friendly products (Stadlthanner et al., Citation2022). Rigorous procedures and best practices for data collection on MTurk were followed, in accordance with recommendations from recent studies (Ribeiro et al., Citation2022). Respondents were provided with an introduction and a brief explanation of green travel behaviour, followed by questions related to the model constructs and demographic information (e.g., age, gender, education level, marital status). The pre-testing of the questionnaire was conducted on a sample of 75 respondents, and Cronbach’s alphas for all constructs exceeded the threshold of 0.70, indicating good reliability.

The final dataset comprised 362 valid responses, which is considered sufficient for conducting a Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis (Hair et al., Citation2022). The study focused on Gen Zers residing in the UK, born between 1997 and 2002. To ensure the accuracy of the responses, control questions were employed to manage the sample of respondents. According to data from the Office for National Statistics in the UK (cited in Statista, Citation2023), the estimated number of Generation Z individuals in the UK in 2020 was approximately 12.7 million, accounting for about 18.9% of the population. In our sample, there was a slight overrepresentation of females (51.2%), with the majority being single (84%) and only 16% being married or cohabitating with a partner. A significant proportion of respondents fell within the age range of 23-26 (67.6%), with the remainder between 18 and 22. The majority of respondents held professional roles (58%), followed by students (35%) who were pursuing undergraduate degrees.

Analytical approach

The data analysis in this study consisted of four stages. The first stage involved establishing the measurement model to assess the reliability and validity of all constructs in the model. This step ensured that the measurement model met the recommended criteria. The second stage focused on examining the structural model. This was done by evaluating the coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), predictive relevance (Q2), and goodness-of-fit model. The hypotheses were tested using a bootstrapping approach with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The third stage utilised Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) to test the proposed model () and the corresponding hypotheses. PLS-SEM was deemed appropriate for this research as it is well-suited for exploratory studies and does not assume any specific distribution of data. It allows for a focus on understanding relationships between variables and does not require confirmation of pre-existing hypotheses. The PLS method is similar to multiple regression analysis as it aims to explain variance in outcome variables and assesses the model’s quality based on psychometric properties of the measurement and structural models. The fourth stage involved the use of SmartPLS 4 software to perform the PLS algorithm and the bootstrapping procedure. SmartPLS 4 is a commonly used software tool for conducting PLS-SEM analysis (Ringle et al., Citation2022).

Common methods bias (CMB)

In this study, several steps were taken to address common method bias (CMB) and ensure the reliability of the data collected. Firstly, respondents were assured of the anonymity of their responses and were informed that the study was for academic purposes, emphasizing that there were no right or wrong answers. This approach helps reduce social desirability bias and encourages respondents to provide honest responses. To further minimize CMB, the predictor and outcome variables were presented separately in the questionnaire, following the recommendation by Jordan and Troth (Citation2020). This separation helps to reduce the likelihood of respondents providing consistent responses across variables due to the method of measurement rather than the actual constructs being measured. After data collection, post-hoc analyses were conducted to assess the presence of CMB. Two methods, Harman’s single-factor test and the marker variable approach, were employed for this purpose. The results of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the highest variance explained by a single unrotated factor was 37.96%. However, it is important to note the limitations of this test, as noted by Chin et al. (Citation2012). To further address CMB, the marker variable approach was also applied. Two PLS structural models were estimated, one with the marker variable as an exogenous variable predicting each construct, and one without the marker variable. The correlations between the marker variable and other constructs were found to be low, and the effects of the marker variable on the endogenous constructs were minimal and statistically insignificant, except for a slight impact on pro-environmental travel behaviour. Importantly, there were no significant differences observed when comparing the outcomes between the two PLS models. Based on these post-hoc analysis results, it was concluded that CMB did not pose a threat to the data collected from the Gen Z cohorts in the UK. These steps were taken to mitigate CMB and enhance the validity and reliability of the study findings.

Results

Evaluation of the measurement model

The analysis of data in this study followed a two-step approach that included evaluating both the measurement and structural models (Hair et al., Citation2022). Reflective constructs were used, and their convergence validity and internal consistency were assessed through factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha (CA), rho_A, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) calculations (Hair et al., Citation2022). The findings in indicate that all factor loadings were above the recommended threshold of 0.50 and all the t-values significant at 0.001 level. The Cronbach alpha, rho_A, and Composite Reliability (CR) values were above 0.70, and the average variance explained (AVE) values were higher than the suggested cut-off of 0.50 (Hair et al., Citation2022). In summary, the results indicate that the measurement model achieved good internal consistency and convergent validity.

To test the discriminant validity of the measurement model, two methods were used—the Fornell and Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio, as recommended by previous studies (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Henseler et al., Citation2015). The Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion evaluates the extent to which the square roots of AVE values of each construct are greater than the correlation between the construct and any other constructs. In this study, all AVE values were higher than their respective highest correlation values with other constructs, indicating that the criterion was met. Furthermore, the HTMT values were found to be below the cut-off value of 0.85, which confirms the discriminant validity of each construct. These results are presented in .

Table 2. Discriminant validity.

Robustness check

To maintain the accuracy of parameters and improve the quality of the measurement model, a confirmatory tetrad analysis (CTA-PLS) was executed within the partial least squares (PLS) framework, following the recommendations of Gudergan et al. (Citation2008). The objective of this analysis was to detect any potential misspecifications in the measurement model concerning the reflective constructs. Results revealed that every construct’s tetrad holds a value of zero, thereby establishing a reliable reflective measurement. These outcomes are in line with the original design of our measurement model, and they substantiate that these constructs are effectively measured reflectively.

Structural model evaluation and hypotheses testing

After confirming the reliability and validity of all model constructs in the initial step (as shown in ), the following step involved assessing the structural model and testing the hypotheses. Prior to this however, metrics were employed such as the R-square (R2), adjusted R2, and Q-square (Q2) values, which were calculated to indicate the percentage of variance explained and effect size (f2). Additionally, the inner variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to evaluate the strength of the association between the dependent and independent variables, and to ensure multicollinearity was not a problem.

R2 values that vary from 0 to 1, and values nearer to 1 suggest more substantial predictive power of the model. The R2 values varied from 0.186 to 0.726, which correspond to the “small” and “large” category according to recommendations by Cohen et al. (Citation2014). Within social sciences research, an R2 value higher than 0.25 is deemed good. Except for willingness to sacrifice with an R2 value of 0.186, the rest of the variables achieved an R2 value ranging from 0.521 to 0.755, indicating that the model had outstanding adequacy. Additionally, f2 values produced in the relationship of the model between the two constructs varied from 0.022 to 0.467. An f2 value greater than 0.02 suggests that the model showed a robust association (i.e., a true effect), though an f2 value near to zero was irrelevant and biased. Consequently, f2 values higher than 0.02 were achieved, demonstrating the intensity of the relationship between each independent and dependent variable (Hair et al., Citation2022). Also, the predictive relevance of the model using Stone-Geisser’s Q2 (Hair et al., Citation2022) was assessed, and the results obtained were all greater than zero, ranging from 0.177 to 0.781 (>0). Lastly, inner VIF values <2.9 were achieved, showing no multicollinearity problems. To finalise the evaluation of the model, the overall fit of the PLS path modelling was gauged using the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) method (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The overall model achieved an SRMR value of 0.072, indicating a suitable fit, considering the widely accepted cut-off point of 0.080 as recommended by Henseler et al. (Citation2015). As a result, we concluded that the goodness-of-fit of the proposed model met the requirements of the model assessment ().

Table 3. Structural model assessment.

After this, the direct effect hypotheses were tested before examining the moderating effects. The 95% confidence interval (CI) at the 5% significance level (two-tailed) was tested using a bootstrapping method with 10,000 resamples. presents the main results of the model, showing that each of the proposed hypotheses was supported empirically. Specifically, the relationships between egoistic value (β = 0.092, p < 0.01), altruistic value (β = 0.414, p < 0.001), biospheric value (β = 0.258, p < 0.001), and ascribed responsibility (β = 0.0, p < 0.001) and environmental concern were positive and significant. Therefore, H1, H2, H3 and H4 were supported. Hypotheses 5–7, which proposed that environmental concern has a positive effect on attitude towards pro-environmental travel (β = 0.723, p < 0.001), willingness to sacrifice (β = 0.431, p < 0.001), and pro-environmental travel behaviour (β = 0.556, p < 0.001), were all statistically significant, supporting these hypotheses. Finally, the positive effects of attitude towards pro-environmental travel (β = 0.245 p < 0.001) and willingness to sacrifice (β = 0.070, p < 0.001) on pro-environmental travel behaviour were both statistically significant. Hence, H8 and H9 were also supported.

Table 4. Result of the structural model hypotheses testing.

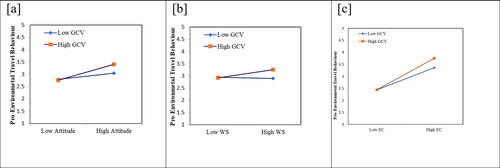

The last three rows within present the results of the moderating effect of green consumption values. This research hypothesised that green consumption values would moderate the relationship between attitudes towards pro-environmental travel and pro-environmental travel behaviour (H10a), willingness to sacrifice and pro-environmental travel behaviour (H10b), and environmental concern and pro-environmental travel behaviour (H10c). To evaluate the moderation effect, we adopted the approach recommended by Henseler et al. (Citation2015), using a PLS product indicator with 10,000 bootstrap resamples. An interaction construct was used in SmartPLS 4 to measure the moderating effect. The results demonstrate that green consumption values increased the effect of environmental concern (β = 0.100, CI = 0.006, 0.182), the effect of attitude towards pro-environmental travel (β = 0.097, CI = 0.014, 0.176), and the effect of willingness to sacrifice (β = 0.057, CI = 0.001, 0.100) on Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. These results revealed that green consumption values strengthen those relationships, and the effects are higher when the green consumption values are also high (vs low). Therefore, H10a, H10b and H10c were all supported. The interaction effects are depicted in .

Conclusion and implications

Building upon previous PEB models and drawing on the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory and theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Han et al., Citation2015; Verma et al., Citation2019), this study focused specifically on the perspective of the underrepresented Gen Z tourists’ and investigated how their values, ascribed responsibility, environmental concern, attitude to pro-environmental travel, willingness to sacrifice and pro-environmental travel behaviour are related. The study also examined the moderating effects of green consumption values on relationships between environmental concern, attitudes concerning pro-environmental travel, willingness to sacrifice and Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour, finding that these effects were stronger when green consumption values were high (vs. low). All thirteen hypotheses were supported, and based on these findings, the study offers both theoretical and managerial implications.

Theoretical implications

This research provides three important contributions to the tourism literature. Firstly, it enhances our understanding of Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour, and more broadly offers novel generational insights to the stream of literature on PEB. Like many behavioural studies, PEB is influenced by several intricate sets of psychological and pro-social factors, as established by past studies (Han, 2021; Steg et al., Citation2011). Moreover, the study draws on different strands of research in behavioural theories and consumer psychology to examine the factors that activate Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. As far as we are aware, we offer and test the first integrative model including the dimensions of values, ascribed responsibility, attitudes concerning the behaviour, and willingness to sacrifice as determinants of Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. Additionally, this study differs from earlier works in the realm of PEB since it targeted the Gen Z cohort, which is a significant and growing segment in the global tourism market. Most studies centred on other cohorts, excluding this new generation with different environmental concerns (Han et al., Citation2015; Landon et al., Citation2018).

Secondly, the study addresses a gap in the tourism literature by examining the influence of willingness to sacrifice on Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. Previous research based on socio-psychology theories, such as the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory and the norm-activation model, has focused on moral norms and neglected the role of willingness to sacrifice in determining environmental concern and pro-environmental behaviour. The findings of this study reveal that Gen Zers’ positive attitudes towards pro-environmental travel practices and their willingness to make sacrifices for the environment significantly contribute to their engagement in pro-environmental travel behaviour. This finding extends the existing literature, which has not included willingness to sacrifice as a determinant of environmental concern and pro-environmental behaviour. The study supports the assumption that Gen Zers are environmentally conscious and more likely to participate in pro-environmental behaviour when they have a stronger concern for the environment. Moreover, the study highlights the significant role of environmental commitment in predicting Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. This is particularly important because Gen Z is a less studied generational cohort within tourism research. While the inclusion of a generational perspective in pro-environmental behaviour literature in tourism has been limited, recent research is increasingly recognising generational differences in sustainable behaviour. By considering willingness to sacrifice and environmental commitment, this study provides valuable insights into the motivations and drivers of Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing effective strategies and interventions to encourage sustainable behaviour among this cohort.

Lastly, the study’s findings highlight the significant moderating effect of green consumption values on Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. When Gen Zers have high green consumption values, these values strengthen the relationship between environmental concern, attitudes towards pro-environmental travel, willingness to sacrifice, and their actual pro-environmental travel behaviour. This implies that Gen Zers who highly value green consumption are more likely to exhibit positive attitudes, express environmental concerns, and engage in pro-environmental travel behaviours. The implications of this finding extend beyond the context of travel and tourism, providing insights into other environmental behaviour topics that aim to promote Gen Zers’ pro-environmental behaviour in general. By recognizing the facilitating role of green consumption values, researchers and practitioners can leverage these values to promote consistent and value-based behaviours among Gen Zers. Activating green-related concepts in the decision-making process of Gen Zers becomes crucial for encouraging behaviours that align with their values. These results contribute to the existing research on value-consistent behaviours by shedding light on the moderating effect of green consumption values on Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. They emphasise the importance of considering individuals’ values and incorporating them into interventions and campaigns aimed at promoting sustainable behaviour among Gen Zers. By leveraging the role of green consumption values, efforts can be made to bridge the attitude-behaviour gap and encourage Gen Zers to act in line with their environmental concerns and values.

Managerial implications

The findings of this study have important practical implications for DMOs, policymakers, marketers, and companies. First, as PEB in travel and tourism is becoming progressively crucial (Li & Wu, Citation2020), companies and policymakers are developing new strategies and campaigns to create environmental awareness (Sharma & Gupta, Citation2020) to boost travellers’ PEB. Gen Zers constitute approximately 18.9% of the UK population (Office for National Statistics cited in Statista, Citation2023) and consequently, campaigns focusing on Gen Z (rather than individual consumers) are becoming more fashionable in travel and tourism. Nevertheless, our study did not find any existing Gen Z-focused policy or strategy that aims to boost Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. Such a policy or strategy could be an efficient instrument in boosting Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour and sustainable consumption.

Second, this study identifies significant factors that influence Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. These factors can be highly significant for DMOs, policymakers and marketers seeking to promote PEB among Gen Zers’ during their travels. The findings suggest that these stakeholders can create campaigns and strategies that increase individuals’ sense of value and responsibility towards the environment. Policymakers and DMOs can develop campaigns that encourage Gen Zers to take responsibility for their travel behaviour and habits, as studies have shown that visitors may refuse responsibility for environmental protection (Seyfi et al., Citation2022). Therefore, it is essential to educate the visitors about their responsibility to protect the environment and engage in more sustainable behaviour while at the destination.

Lastly, the findings of this study also showed that environmental concern, positive attitudes, and willingness to sacrifice contribute to Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. This confirms that Gen Zers’ concern for the environment, attitudes, and willingness to make sacrifices are important factors in promoting sustainable travel behaviour. Considering this, DMOs, policymakers, and marketers should develop strategies to utilise Gen Zers’ green consumption values, which will help increase their concern for the environment, positive attitudes towards PEB, and willingness to sacrifice for the environment, ultimately leading to more sustainable travel behaviour.

Limitations and future research

The study acknowledges several limitations that present opportunities for future research. Firstly, the data collection focused exclusively on the Gen Z cohort. To gain a broader understanding of PEB, future studies should consider collecting data from other generational cohorts, such as Millennials and Generation X, to explore potential differences in their pro-environmental behaviour. Comparing and contrasting the findings across different cohorts would provide valuable insights into the generational variations in PEB. Additionally, this study concentrated only on British Gen Zers, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other cultural contexts. Considering the influence of culture on tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour, future research should replicate the model in different contexts and cultural backgrounds to examine the cross-cultural variations in Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour. Moreover, the sample used in the study was skewed towards respondents with undergraduate degrees, which may not be representative of the broader Gen Z population in the UK. Future studies should aim to improve the representativeness of the sample by employing diverse sampling methods and collecting additional demographic information. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the target population and enhance the external validity of the findings. Furthermore, future research could consider cross-cultural validation to determine if Gen Zers’ pro-environmental travel behaviour differs across different cultural settings. Considering cultural dimensions and variations, as highlighted by Hofstede Insights, would provide valuable insights into the cultural influences on PEB. To expand the scope of research, future studies could include additional variables that were not examined in the current study. For example, incorporating environmental knowledge and Gen Zers’ personality traits, particularly the big-five personality traits, would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing PEB among Gen Z. This would enable the development of targeted strategies to promote sustainable tourism practices and consumption within this cohort.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen. I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

- Bailey, A. A., Mishra, A., & Tiamiyu, M.F. (2016). GREEN consumption values and Indian consumers’ response to marketing communications. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(7), 562–573. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-12-2015-1632

- Bergamini, P. (2020). Millennial and Gen Z: how their shopping habits are changing in the COVID-19 era. https://blog.mailup.com/2020/12/gen-z-millennials-covid/.

- Booking.com. (2019). From ambitious bucket lists to going it alone, Gen Z travellers can’t wait to experience the world. https://news.booking.com/from-ambitious-bucket-lists-to-going-it-alone-gen-z-travellers-cant-wait-to-experience-the-world/.

- Chen, Z., Ryan, C., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Cross-generational analysis of residential place attachment to a Chinese rural destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 787–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1890095

- Chin, W. W., Thatcher, J. B., & Wright, R. T. (2012). Assessing common method bias: Problems with the ULMC Technique. MIS quarterly, 36(3), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.2307/41703491

- Choi, H., Jang, J., & Kandampully, J. (2015). Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 51, 87–95.

- Cleaver, M., & Muller, T. E. (2002). The socially aware baby boomer: Gaining a lifestyle-based understanding of the new wave of ecotourists. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(3), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667161

- Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2014). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd edition). Psychology Press.

- Cordano, M., Welcomer, S., Scherer, R., & Parada, V. (2011). Understanding cultural differences in the antecedents of pro-environmental behavior: A comparative analysis of business student in the United States and Chile. Journal of Environmental Education, 41, 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960903439997

- Corey, S., & Grace, M. (2019). Generation Z. A century in the making. Routledge.

- Davis, J. L., Le, B., & Coy, A. E. (2011). Building a model of commitment to the natural environment to predict ecological behavior and willingness to sacrifice. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.01.004

- De Groot, J. I., & Steg, L. (2008). Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 330–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506297831

- De Groot, J. I., & Steg, L. (2009). Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149(4), 425–449. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449

- Diekmann, A., & Preisendörfer, P. (2003). Green and greenback: The behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Rationality and Society, 15(4), 441–472.

- Dunlap, R. E., & Jones, R. E. (2002). Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. In R.E. Dunlap and W. Michelson (Eds.), Handbook of environmental sociology (pp. 482–524). Greenwood Press.

- Elhoushy, S. (2020). Consumers’ sustainable food choices: Antecedents and motivational imbalance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102554

- Elhoushy, S., & Lanzini, P. (2021). Factors affecting sustainable consumer behavior in the MENA Region: A systematic review. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 33(3), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2020.1781735

- Erul, E., Uslu, A., Cinar, K., & Woosnam, K. M. (2022). Using a value-attitude-behaviour model to test residents’ pro-tourism behaviour and involvement in tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2153013

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gelissen, J. (2007). Explaining popular support for environmental protection. Environment and Behavior, 39(3), 392–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506292014

- Gudergan, S. P., Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2008). Confirmatory tetrad analysis in PLS path modeling. Journal of Business Research, 61(12), 1238–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.012

- Haddouche, H., & Salomone, C. (2018). Generation Z and the tourist experience: tourist stories and use of social networks. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0059

- HairJr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM ) (3rd edition). Sage publications.

- Han, H., Hsu, L.-T., & Sheu, C. (2010). Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tourism Management, 31(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Kim, J., & Jung, H. (2015). Guests’ pro-environmental decision-making process: Broadening the norm activation framework in a lodging context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.03.013

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Lee, M. J., & Kim, J. (2019). Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tourism Management, 70, 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.006

- Han, H., Yu, J., Kim, H.-C., & Kim, W. (2018). Impact of social/personal norms and willingness to sacrifice on young vacationers’ pro-environmental intentions for waste reduction and recycling. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(12), 2117–2133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1538229

- Han, H. (2021). Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 1021–1042.

- Haws, K. L., Winterich, K. P., & Naylor, R. W. (2014). Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(3), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.11.002

- Heberlein, T. A. (1972). The land ethic realized: Some social psychological explanations for changing environmental attitudes 1. Journal of Social Issues, 28(4), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1972.tb00047.x

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Homer, P. M., & Kahle, L. R. (1988). A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 638–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.638

- Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

- Kim, E. J., Tanford, S., & Book, L. A. (2021). The effect of priming and customer reviews on sustainable travel behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 60(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519894069

- Kim, M. S., & Stepchenkova, S. (2020). Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(13), 1575–1580. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1628188

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Landon, A. C., Woosnam, K. M., & Boley, B. B. (2018). Modeling the psychological antecedents to tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors: An application of the value-belief-norm model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(6), 957–972. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1423320

- Li, Q., & Wu, M. (2020). Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour in travel destinations: Benchmarking the power of social interaction and individual attitude. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1371–1389. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1737091

- Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2007). Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 63(1), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00499.x

- Lou, X., & Li, L. M. W. (2023). The relationship of environmental concern with public and private pro‐environmen pro‐environmental behaviours: A pre‐registered meta‐analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(1), 1–14.

- Megeirhi, H. A., Woosnam, K. M., Ribeiro, M. A., Ramkissoon, H., & Denley, T. J. (2020). Employing a value-belief-norm framework to gauge Carthage residents’ intentions to support sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1351–1370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1738444

- Mostafa, M. M. (2007). Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: The effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(3), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2006.00523.x

- Poortinga, W., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2016). Values, environmental concern, and environmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 36(1), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916503251466

- Prayag, G., Aquino, R. S., Hall, C. M., Chen, N., & Fieger, P. (2022). Is Gen Z really that different? Environmental attitudes, travel behaviours and sustainability practices of international tourists to Canterbury, New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2131795

- Rahman, I., & Reynolds, D. (2016). Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 52, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.09.007

- Rezapouraghdam, H., Akhshik, A., & Ramkissoon, H. (2021). Application of machine learning to predict visitors’ green behavior in marine protected areas: Evidence from Cyprus. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1887878

- Ribeiro, M.A., Gursoy, D., & Chi, O.H. (2022). Customer acceptance of autonomous vehicles in travel and tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 61(3), 620–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287521993578

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., Becker, J.-M. (2022). SmartPLS 4. SmartPLS GmbH.

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free press.

- Ru, X., Wang, S., Chen, Q., & Yan, S. (2018). Exploring the interaction effects of norms and attitudes on green travel intention: An empirical study in eastern China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 197, 1317–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.293

- Salinero, Y., Prayag, G., Gómez-Rico, M., & Molina-Collado, A. (2022). Generation Z and pro-sustainable tourism behaviors: Internal and external drivers. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2134400

- Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 550–562.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–65). Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

- Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 550. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., Vo-Thanh, T., & Zaman, M. (2022). How does digital media engagement influence sustainability-driven political consumerism among Gen Z tourists? Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2112588

- Seyfi, S., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Hall, C. M., & Vo-Thanh, T. (2023). Exploring the drivers of Gen Z tourists’ buycott behaviour: A lifestyle politics perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2166517

- Sharma, N., Goel, P., Nunkoo, R., Sharma, A., & Rana, N. P. (2023). Food waste avoidance behavior: How different are generation Z travelers? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2187741

- Sharma, R., & Gupta, A. (2020). Pro-environmental behaviour among tourists visiting national parks: Application of value-belief-norm theory in an emerging economy context. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(8), 829–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1774784

- Song, Y., Qin, Z., & Qin, Z. (2020). Green marketing to gen Z consumers in China: examining the mediating factors of an eco-label–informed purchase. Sage Open, 10(4), 2158244020963573.

- Stadlthanner, K. A., Andreu, L., Ribeiro, M. A., Font, X., & Mattila, A. S. (2022). The effects of message framing in CSR advertising on consumers’ emotions, attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(7), 777–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2022.2065399

- Statista. (2023). Population of the United Kingdom from 1990 to 2020, by generation. https://www.statista.com/statistics/528577/uk-population-by-generation/

- Steg, L., & De Groot, J. I. M. (2012). Environmental values. In S. Clayton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology (pp. 81–92) New York: Oxford University Press.

- Steg, L. E., Van Den Berg, A. E., & De Groot, J. I. (2013). Environmental psychology: An introduction. BPS Blackwell.

- Steg, L., De Groot, J. I., Dreijerink, L., Abrahamse, W., & Siero, F. (2011). General antecedents of personal norms, policy acceptability, and intentions: The role of values, worldviews, and environmental concern. Society and Natural Resources, 24(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903214116

- Stern, P. dC. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175

- Stern, P. C., & Dietz, T. (1994). The value basis of environmental concern. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb02420.x

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., & Kalof, L. (1993). Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environment and Behavior, 25(5), 322–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916593255002

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T. D., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human ecology review, 6(2), 81–97.

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (1995). The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context. Environment and behavior, 27(6), 723–743.

- Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (2009). The fourth turning: What the cycles of history tell us about America’s next rendezvous with destiny. Broadway Books

- Van Doorn, J., & Verhoef, P. C. (2015). Drivers of and barriers to organic purchase behavior. Journal of Retailing, 91(3), 436–450

- Van Riper, C. J., & Kyle, G. T. (2014). Understanding the internal processes of behavioral engagement in a national park: A latent variable path analysis of the value-belief-norm theory. Journal of environmental psychology, 38, 288–297

- Varshneya, G., Pandey, S. K., & Das, G. (2017). Impact of social influence and green consumption values on purchase intention of organic clothing: A study on collectivist developing economy. Global Business Review, 18(2), 478–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150916668620

- Verma, V. K., Chandra, B., & Kumar, S. (2019). Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers’ attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. Journal of Business Research, 96, 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.021

- Wang, X., & Zhang, C. (2020). Contingent effects of social norms on tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours: The role of Chinese traditionality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1646–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1746795

- Wee, D. (2019). Generation Z talking: Transformative experience in educational travel. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(2), 157–167.

- World Economic Forum. (2018). Generation Z will outnumber millennials this year. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/08/generation-z-will-outnumber-millennials-by-2019/.

- Wu, J., Font, X., & Liu, J. ( 2021). Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors: Moral obligation or disengagement? Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 735–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520910787

- Xu, Z., Yang, G., Wang, L., Guo, L., & Shi, Z. (2023). How does destination psychological ownership affect tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors? A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(6), 1394–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2049282

- Yan, L., Keh, H. T., & Wang, X. (2021). Powering sustainable consumption: The roles of green consumption values and power distance belief. Journal of Business Ethics, 169(3), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04295-5

- Yeoman, I., & McMahon-Beattie, U. (Eds.). (2019). The future past of tourism: Historical perspectives and future evolutions. Channel View Publications.