Abstract

Business travel is a major contributor to the greenhouse gas emissions of knowledge organizations. Through four case studies, the present research uses qualitative-structuring content analysis to identify seven dominant themes concerning reasons, strategies, and measures for decarbonizing business travel. The paper provides an in-depth examination of the structural and behavioral barriers to business travel decarbonization, highlights the need for a holistic approach to business travel decarbonization, and provides insight into the challenges organizations face in aligning their business interests and sustainability commitments. The main findings are that limited progress with business travel decarbonization raises questions about the effectiveness of voluntarism, that the question of who bears responsibility for decarbonization remains unresolved, and that a transition from non-behavioral approaches to changes in business-travel behavior is needed. By conceptualizing current states and mechanisms and considering relevant systemic interdependencies between travelers, organizations, and the environment, the paper presents a holistic conceptual model that extends the theoretical understanding of business travel decarbonization. In practical terms, the paper outlines how successful decarbonization in knowledge organizations can be achieved in terms of the interplay among reasons, strategies, and measures and provides concrete recommendations for action for organizations.

Introduction

Business travel is not only a significant contributor to commercial and non-commercial organizations’ carbon emissions but also adds significantly to the emissions of the tourism sector (Aguiléra, Citation2014; Davies & Armsworth, Citation2010). Research has highlighted the dilemma that business travelers increasingly want to avoid high-carbon business travel, but structural barriers impede behavioral change (Cohen & Gössling, Citation2015; Cohen et al., Citation2018; Lassen, Citation2010a). While business travelers are forced to balance the advantages of short-term personal benefits and professional obligations against a desire to avoid contributing to long-term environmental damage (Cohen & Kantenbacher, Citation2020; Poom et al., Citation2017), organizations must align their business interests and sustainability commitments (Roby, Citation2014; Walsh et al., Citation2021). In this research, I seek to understand how knowledge organizations can not only commit to decarbonizing business travel but effectively achieve this.

The number of organizations that are recognizing the contribution of their business activities to global warming and committing to reducing emissions is increasing (Black et al., Citation2021; Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023; UNFCCC, Citation2022). Reducing emissions is a priority, especially for knowledge-intensive service organizations such as management consultancies, insurance companies, and universities. For such organizations associated with minimal emissions from energy-intensive manufacturing processes, addressing Scope 3 emissions is essential. These emissions encompass all other indirect emissions in the value chain, including upstream and downstream activities not covered under Scope 2 (Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Citation2013). Accordingly, business travel emerges as a critical lever for achieving emissions reduction objectives (El Geneidy et al., Citation2021). However, organizational decarbonization commitments made through initiatives such as the UN’s Race to Zero and the Science-Based Target Initiative (SBTi) differ not only in their motivation but also in implementation (Black et al., Citation2021; Dahlmann et al., Citation2019). In relation to business travel, recent findings by Transport & Environment (Citation2023) indicate that a significant 85% of global companies lack ambitious goals for reducing emissions from corporate travel.

Business travel demand is always determined by individual preferences and structural preconditions such as strategy, geographic dispersion, and infrastructure availability (Derudder et al., Citation2011; Wickham & Vecchi, Citation2010). Its decarbonization—according to Hopkins et al. (Citation2019)—thus depends on structural reconfiguration. Structurally, theory suggests that market- (Poom et al., Citation2017; Porter, Citation1985; Porter & Van Der Linde, Citation1995b), resource- (Gouthier & Schmid, Citation2003; Hart, Citation1995), and institution-based (Gustafson, Citation2013; Peng et al., Citation2009; Roby, Citation2014) approaches may explain the state of business travel decarbonization. Research further highlights the fundamental conflict between the goals of the international expansion of organizations and decarbonization (Glover et al., Citation2017; O’Neill & Sinden, Citation2021; Tseng et al., Citation2022). However, a well-grounded, holistic examination of business travel decarbonization is still lacking in the literature. In relation to this theoretical background, the paper addresses three research questions:

What are the reasons for knowledge organizations’ business travel decarbonization efforts?

How do knowledge organizations strategically align their structural requirements for business travel and their decarbonization commitments?

What measures are knowledge organizations taking to foster the transition to low-carbon business travel?

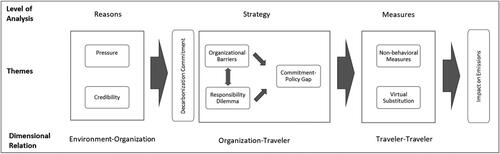

Based on four case studies (of two universities, an insurance company, and a management consultancy), seven dominant themes concerning reasons, strategies, and measures were identified using qualitative-structuring content analysis (Kuckartz, Citation2010, Citation2018). The study findings indicate that organizations are driven to commit to decarbonizing business travel due to external pressure and the need to maintain credibility. However, there is misalignment between these commitments and organizational strategy that may be attributed to barriers such as organizational autonomy, the challenge of determining responsibility for reducing emissions, and the gap between commitments and enforceable policies. The implementation of decarbonization measures primarily focuses on non-behavioral approaches. Therefore, there is a crucial need for stronger strategic alignment to effectively and efficiently decarbonize business travel.

Scott and Gössling (Citation2022) conclude “that the last three decades of research have failed to prepare the sector for the net-zero transition and climate disruption that will transform tourism over the next three decades” (p. 1). Given the substantial influence of demand on decarbonizing the tourism sector and the resulting emphasis on organizations’ responsibility for meeting broader decarbonization goals, business travel emerges as a critical area where organizational contributions are highly significant. This study fills a critical knowledge gap by analyzing the various forms of systemic dependency in business travel, providing a comprehensive understanding of the sector’s current state of decarbonization, and proposing a holistic model for effectively reducing carbon emissions in business travel. The model uses insights from interdisciplinary literature to enhance its comprehensiveness. The conceptual models presented here not only contribute theoretically to understanding business travel decarbonization but offer practical help with making recommendations for successfully decarbonizing knowledge organizations.

Literature review

Business travel in knowledge industries

Physical travel that enables face-to-face contact is still largely preferred for doing business, communicating formally and informally, and building personal and professional networks (Beaverstock et al., Citation2010; Beaverstock et al., Citation2009; Becken & Hughey, Citation2022; Lian & Denstadli, Citation2004; Müller & Wittmer, Citation2023). Business-travel demand is determined by individual preferences and several structural preconditions. While demographic, personality, and job characteristics, alongside organizational factors as well as home and family, influence preferences (Defrank et al., Citation2000), the location of the business and the associated cultural practices, company structures, business models, customer expectations and availability and suitability of modes of transport are among the external determinants of travel behavior (Roby, Citation2014). As mobility is deeply embedded into working arrangements, even if many business travelers largely make their own travel decisions, the latter always act within pre-existing structures and must comply with company policies and regulations (Derudder et al., Citation2011; Wickham & Vecchi, Citation2010).

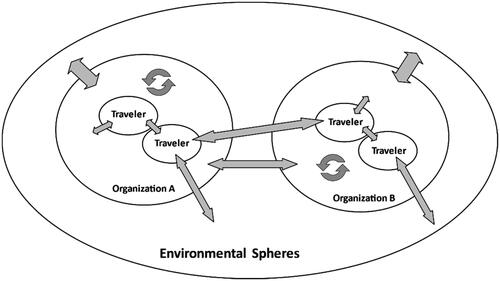

Conceptually, there are three relevant dimensions of business travel (). The micro-level comprises the traveler as a member of an organization. The meso-level consists of the organizations whose activities lead to business travel. These organizations, in turn, are embedded in environmental spheres at the macro level. Environmental spheres are understood as the context of the organization, including the economy, technology, nature, and society (Rüegg-Stürm & Grand, Citation2019, p. 44). describes the relationships and dependencies that arise between the respective actors and dimensions.

Table 1. Description of relationships in the context of business travel.

To a great extent, the nature of the work, including the business sector, type of profession, and company strategies, determines the importance of travel for an organization (Aguiléra & Proulhac, Citation2015). Corporate travel is deemed particularly important in knowledge organizations (Faulconbridge et al., Citation2009), which are organized in geographically dispersed ways (Gustafson, Citation2012). The finding that it is especially knowledge workers at all levels who are among the most frequent travelers (Jones, Citation2010, Citation2013; Lassen, Citation2010b; Wickham & Vecchi, Citation2010) is unsurprising, as the global economy is increasingly dependent on so-called knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) (Aslesen & Isaksen, Citation2007; Poom et al., Citation2017; Ström & Mattsson, Citation2005). According to El Geneidy et al. (Citation2021), knowledge organizations can be divided into two main groups: organizations that invest in knowledge (e.g. universities) and those that apply knowledge to produce goods and services, so-called knowledge-based companies (Karlsson et al., Citation2009). Examples of such service firms are those in finance, IT, legal services, insurance, accounting, and business consultancy (Wood, Citation2017). KIBS organizations rely on a business network wherein “knowledge can be created, accumulated and disseminated” and are therefore—arguably—dependent on face-to-face contact, which results in a propensity for travel (Poom et al., Citation2017, p. 292).

While the substantial amount of corporate travel associated with international companies can be readily linked to their global strategies, the underlying factors that drive travel in universities may not be as apparent. Participation in academic activities entails a significant amount of international networking and collaboration, thus, a correspondingly large amount of business travel (Achten et al., Citation2013). Even though Wynes et al. (Citation2019) found no relationship between air travel (emissions) and metrics of academic productivity, the frequent use of high-carbon travel is firmly established and normalized in academic mobility and (re-)enforced by institutional mechanisms (Higham & Font, Citation2020; Hopkins et al., Citation2016, Citation2019; Storme et al., Citation2017). International student recruitment is crucial for universities, and while the travel of students is not accounted for in the business travel emissions of organizations, it represents another avenue for reducing emissions (Davies & Dunk, Citation2015).

The COVID-19 pandemic massively curtailed global business travel, forcing knowledge organizations to rethink business norms. To some extent, this external shock, combined with economic challenges and the climate emergency, may have permanently transformed business (travel) practices (Becken & Hughey, Citation2022; Gössling & Schweiggart, Citation2022; Kamb et al., Citation2021). It thus seems an opportune moment to take a closer look at the state of business-travel decarbonization in knowledge-intensive industries.

Organizational decarbonizing commitments and business travel

Business travel has an “emissions problem” that cannot be ignored by public and private organizations as the urgency of stopping global warming is ever greater, and the economic and social consequences of the pandemic have changed established behavior patterns. It is estimated that global carbon emissions caused by business travel amount to around 154 MtCO2, representing about 17% of emissions from commercial aviation (Borko et al., Citation2020; Graver et al., Citation2020). It is moreover likely that a substantial share of the 10% of the most frequent flyers that are the cause of more than half of global CO2 emissions associated with commercial aviation (Gössling & Humpe, Citation2020) are traveling for work. Travel-related emissions constitute a significant proportion of the total emissions generated by knowledge organizations. A decade ago, the former was the second-largest emission source across all sectors (Davies & Armsworth, Citation2010). However, recent findings by El Geneidy et al. (Citation2021) reveal that travel-related emissions now account for a substantial 79% of the total emissions of knowledge organizations. Aguiléra (Citation2014) attributes this to the prevalent use of carbon-intensive modes of transport by business travelers.

Business travel is being addressed by the decarbonization efforts of an increasing number of organizations, but the former are very heterogeneous in terms of design, motivation, and success. Since before the pandemic, companies have been increasing their efforts to harmonize their practices in line with the objectives of the Paris Agreement (Black et al., Citation2021; Dahlmann et al., Citation2019). Non-governmental action can complement and amplify climate-change mitigation efforts at the national level and help governments forge ahead in curbing greenhouse gas emissions (Foerster & Spencer, Citation2023; Giesekam et al., Citation2021). As a result, an increasing number of commercial and non-commercial organizations are voluntarily committing to climate action. More than 11,309 non-state actors (as of September 2022) have already made climate commitments and have joined the United Nations Race to Zero Campaign (UNFCCC, Citation2022). It is estimated that more than 20% of the world’s 2000 largest companies have made some sort of net-zero commitment (Black et al., Citation2021; Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023). Just the companies that have joined the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) account for more than one-third of global market capitalization in 2021 (Science Based Targets, Citation2022).

However, these climate commitments are very heterogeneous in terms of motivations and the implementation of targets (Comello et al., Citation2021; Dahlmann et al., Citation2019; Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023), although the trend is increasingly for establishing science-based targets (Andersen et al., Citation2021; Dahlmann et al., Citation2019). This is due not only to different ambitions and scopes but also to the lack of consistent and binding measurement and reporting standards in corporate carbon management (Comello et al., Citation2021; Lister, Citation2018). Not surprisingly, this area is frequently a target of accusations of greenwashing and a lack of transparency (Dahlmann et al., Citation2019; Giesekam et al., Citation2021). Assessments of the importance and success of self-regulatory measures such as the SBTi are therefore very mixed (Arnold & Toledano, Citation2021; Black et al., Citation2021; Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023; Foerster & Spencer, Citation2023; United Nations Climate Action, Citation2022).

Similarly, there is inconsistency in terms of dealing with emissions from business travel through organizational-level carbon management. Typically, the emissions associated with corporate travel are categorized as Scope 3 emissions (Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Citation2013). Although Scope 3 emissions make up the largest part of the organizational footprint, they are rarely prioritized in carbon management policies (Caritte et a., 2015; Robinson et al., Citation2018). Arnold and Toledano (Citation2021) found that only 37% of companies have set specific targets for Scope 3 emissions. Research suggests that implementing effective measures in this area is more challenging than for internal operations. In addition, it has been found that opting for low-carbon alternatives in specific emission-generating areas (such as business travel) does not often occur (Giesekam et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, a growing number of organizations are trying to include business travel in their decarbonization efforts. This paper seeks to shed light on reasons, strategies, and measures taken in this context.

Theoretical explanations for business travel decarbonization

External influences on business travel behavior hinder sustainability efforts. Studies show that some travelers desire to reduce their traveling but feel they have limited control over this (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Lassen, Citation2010a). Pro-environmental attitudes can be undermined by individual-level rationalizations and structural factors (Poggioli & Hoffman, Citation2022). Consequentially, decarbonizing professional mobility relies on lasting structural changes (Hopkins et al., Citation2019; Schmidt, Citation2022). However, there is a lack of comprehensive understanding of the latter in the literature. To explore the reasons, strategies, and measures for the decarbonization of business travel, this paper relies on interdisciplinary research from the field of corporate sustainability. It embraces the conceptualization of business travel decarbonization as a strategic process, drawing inspiration from the strategy formation proposed by the design school in strategy research. This approach underscores the significance of considering internal and external factors that shape the conception of strategy and its subsequent implementation (Mintzberg et al., Citation2020).

Reasons

Bansal and Roth (Citation2000) identify three general sources of motivation for organizational sustainability efforts: competitiveness, legitimation, and ecological responsibility, influenced by the ecological, organizational, and individual context. More theoretically, first, Porter’s (Citation1985) market-based logic suggests value creation through differentiation based on corporate sustainability, with sustainability efforts driven by cost considerations (Porter & Van Der Linde, Citation1995b). Namely, reducing corporate travel may also result in substantial cost savings. Second, adopting a resource-based view, internal and external stakeholder pressure and resource acquisition play a role, with customers seen as important stakeholders and key resources in knowledge organizations (Flammer, Citation2013; Gouthier & Schmid, Citation2003; Lloret, Citation2016; Robèrt, Citation2009; Roby, Citation2014). The preference for face-to-face interaction links business travel to securing key resources (Beaverstock et al., Citation2009, Citation2010; Lian & Denstadli, Citation2004). Decarbonization is advocated in relation to addressing the organizational relationship with the natural environment (Hart, Citation1995). Third, from an institution-based perspective, institutional limits, formal rules, and regulations shape behavior, with regulatory pressure and pre-empting government regulation being important drivers (Delmas & Montes-Sancho, Citation2009; Delmas & Toffel, Citation2008; Peng et al., Citation2009). While institutional vision and adaptability are necessary for successful sustainable transformation (Lloret, Citation2016; Porter & Van Der Linde, Citation1995a), regulatory compliance remains a significant driver of corporate sustainability (Engert et al., Citation2016).

Strategy

Organizations must strategically align business goals and sustainability commitments (Roby, Citation2014; Walsh et al., Citation2021). Although Poom et al. (Citation2017) are convinced that the potential for firms to decarbonize corporate travel without harming their financial sustainability has not been fully exploited, reducing business air travel while maintaining productivity and international cooperation remains challenging (Caset et al., Citation2019). For internationally oriented organizations, a fundamental strategic contradiction arguably exists between internationalization and sustainability efforts (Glover et al., Citation2017; O’Neill & Sinden, Citation2021; Tseng et al., Citation2022). Business travel decarbonization is a strategic process that involves baseline analysis, emissions measurement, and reporting (Caritte et al., Citation2015; Davies & Armsworth, Citation2010; Robinson et al., Citation2015). Control-oriented and commitment-oriented measures are necessary for supporting effective low-carbon business travel (Gustafson, Citation2013), with formal policies enabling the transition (Higham & Font, Citation2020; Higham et al., Citation2019). Robust corporate governance, including target-setting, internal carbon accounting, pricing, and independent reporting supports long-term sustainability efforts (Lloret, Citation2016), while obstacles such as a lack of leadership commitment can impede decarbonization progress (Caritte et al., Citation2015; Lister, Citation2018; Robinson et al., Citation2015). Hahn et al. (Citation2015) highlight three sources of tension in corporate sustainability: the influence of the broader context on individual and corporate decisions, the need for fundamental organizational change, and the contradiction between long-term impact and short-term focus. Moreover, customer attitudes, technological constraints, fear of the unknown, and especially resource limitations, can hinder decarbonization efforts (Poggioli & Hoffman, Citation2022; Roby, Citation2011, Citation2014). Ensuring access to strategic resources is crucial for successfully decarbonizing business travel (Poggioli & Hoffman, Citation2022).

Measures

Solutions to the emissions problem of business travel have also been discussed. While some organizational decarbonization approaches focus on minimizing the impact of travel through a modal shift toward low-carbon transport modes (Aguiléra, Citation2014; Davies & Armsworth, Citation2010; Whitmarsh et al., Citation2020), or the reduction of travel distance or travel class (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Roby, Citation2011, Citation2014), others look at substituting physical travel altogether by using virtual alternatives such as video conferencing (Denstadli, Citation2004; Denstadli & Gripsrud, Citation2010; Denstadli et al., Citation2012, Citation2013; Lu & Peeta, Citation2009; Millar & Salt, Citation2007; Müller & Wittmer, Citation2023). Besides directly addressing business travel activities, organizations have the option to offset emissions, which is often seen as easier, faster, and more cost-effective than making internal reductions. This can be achieved through mandatory or voluntary offsetting, earning carbon credits through nature-based or technological measures such as reforestation projects or climate tech solutions like synthetic fuels and carbon sequestration (Bumpus & Liverman, Citation2008; Cox & Johnson, Citation2021).

While these explanatory approaches give a general, theoretical idea of the interplay between reasons and strategies in the field of decarbonization of business travel and related measures, the literature lacks holistic treatment of the same in practice. This paper makes a valuable theoretical contribution to the identification of relevant themes and helps explain the mechanisms involved in the decarbonization of business travel.

Method

This study examines the decarbonization of business travel using a qualitative and explorative approach using multiple case studies (Swanborn, Citation2010; Yin, Citation2018). The aim of the case studies, partly due to the lack of previous research on the decarbonization of business travel, is not to test specific theories or check their plausibility but to contribute to theory development through implementing a heuristic case study and deepening understanding of the relevant structural preconditions that influence low-carbon business travel in companies. Thus, this study largely follows a strongly application-oriented research approach (Ulrich, Citation1982). By comparing the different cases, a conceptual model for fostering the decarbonization of business travel is developed. In this regard, Flyvbjerg (Citation2006, p. 7) points out the value of “concrete, context-dependent knowledge.” The instrumental case studies in this paper are thus valuable as they examine four knowledge organizations from different travel-intensive sectors and develop new knowledge about the emergence, facilitation, and obstruction of climate-friendly business-travel practices. The choice of more than one case increases external validity (Yin, Citation2018).

Case selection

A comprehensive approach was adopted based on substantive and practical considerations to select informative cases that represent the phenomenon of business-travel decarbonization (Swanborn, Citation2010). First, the substantive criteria involved identifying organizations operating in the knowledge-intensive industry, characterized by a comparatively high volume of business travel and a commitment to reducing their carbon footprint. Furthermore, preference was given to organizations based in or with a presence in Switzerland—where a strong economy, a high degree of international connectivity, plus one of the highest foreign-trade-to-GDP ratios (Federal Statistical Office, Citation2021) result in a proportionally very high volume of work-related travel (Beaverstock & Faulconbridge, Citation2010) and a comparably large aviation-related carbon footprint (CO2-Emissionen des Luftverkehrs. Grundsätzliches und Zahlen, Citation2020)—making the country ideal for the study of business travel. The practical considerations associated with the case selection involved ensuring the feasibility of the data collection strategy. This entailed identifying organizations with sufficient available documentation and obtaining their agreement for interviews. For companies, the shortlist was derived from the Travel Smart ranking 2022 (Transport & Environment, Citation2022). Three companies met the criteria and were contacted, with two agreeing to participate in interviews. Similarly, for universities, the shortlist was based on the signatory list of the Race to Zero (UNFCCC, Citation2022). Two universities were contacted, both of which expressed a willingness to participate in interviews, meeting the established criteria. The selected cases are presented in .

Table 2. Description of examined cases.

Data collection and analysis

The case studies are based on data obtained from various written sources as well as transcripts of audiovisual documentation such as policy documents, internal statistics about travel and CO2 inventories, but also sustainability reports, websites, and public reporting on the topic. A rigorous search strategy was employed to thoroughly investigate the organizations’ rationales, strategies, and initiatives for decarbonizing business travel. The primary sources of information included the organizations’ official websites and accessible archival materials. Relevant sections focusing on sustainability, environmental stewardship, and corporate social responsibility were carefully examined. Keyword combinations such as “business travel decarbonization”, “sustainable corporate travel”, and “corporate travel emissions reduction initiatives” were utilized to identify pertinent documents and reports. Additionally, a comprehensive internet search was conducted, incorporating the organizations’ names with phrases such as “business travel carbon footprint reduction” and “implementation of environmentally friendly travel policies and practices.” This resulted in a database of 1338 pages of relevant documents.

Eight semi-structured interviews were conducted with leadership representatives from all the organizations in the second half of 2022 to enhance the documentation. While the study primarily focused on official organizational standpoints as reflected in official documents, the interviews provided valuable insight into the individual perspectives of executives, complementing the published organizational perspective. Challenges obtaining interview permission and the logistical complexities of centralized communication with company headquarters reinforced the rationale of prioritizing document analysis. The availability of documentation allowed for selecting specific, knowledgeable individuals with insights into business travel decarbonization in each organization. The interview guide was based on the literature review and, where necessary, specifically adapted for each organization following the first round of document analysis. Saturation was achieved through document analysis and eight interviews, in line with the recommendations of Guest et al. (Citation2006) for identifying meta-themes and achieving saturation.

The findings within each case converged and were included in a case-study database to create a holistic, in-depth account of each case and enable triangulation (Yin, Citation2018). The interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded, and analyzed according to content-structuring analysis (Kuckartz, Citation2010, Citation2018) using ATLAS.ti 22 software. The cases are presented in anonymous form to avoid issues with internal compliance at the studied organizations.

Results

To answer the overarching research questions, three main levels of explanation were identified a priori and explored. These are the reasons for decarbonizing business travel, the strategic alignment of business-travel requirements and decarbonization commitments, and measures for transitioning to low-carbon business travel. The themes that emerged at the different levels are presented below. in the appendix shows examples of the occurrence of the themes in all cases.

Reasons

The first level of analysis concerns the rationale of organizations for addressing the issue of travel emissions and for publically committing to decarbonizing business travel. It becomes apparent here that the identified commitments are strongly externally driven as the focus is on the environment–organization relationship. Two dominant themes were identified: pressure and credibility.

Pressure

Decarbonization decisions and commitments are influenced by various stakeholders, including customers, employees, NGOs, regulators, shareholders, and other funding providers. In particular, customers, notably students in the case of universities, exert significant pressure on organizations to address decarbonization. This reflects a broader shift in public opinion toward sustainability and environmental concern, which organizations are keenly aware of. Furthermore, both types of organizations, but especially universities, are experiencing greater emphasis on rankings and ratings, which amplifies the importance of transparency and accountability. As organizations strive to improve their rankings and ratings, they are driven to enhance their sustainability practices and commit to decarbonization initiatives. The integration of sustainability metrics into rankings and ratings highlights the shifting landscape within which organizations are compelled to meet higher standards of sustainability performance to maintain their competitive edge and public reputation.

Credibility

Related to pressure, specifically, the credibility of organizations is intrinsically linked to their ability to align their behavior, convey knowledge, and commitment to decarbonization. This need for credibility stems from several factors. First, organizations recognize the importance of showing leadership in decarbonization matters. By actively communicating their decarbonization initiatives, they aim to signal their expertise, knowledge, and commitment to addressing climate change. This proactive stance allows them to position themselves as industry leaders and attract positive publicity, enhancing their reputation and credibility among stakeholders. In doing so, knowledge organizations recognize that credibility associated with decarbonization efforts can significantly affect their core business. Customers, clients, and partners increasingly expect organizations to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability, including decarbonization. By aligning their behavior with decarbonization goals, organizations expect to attract and retain environmentally conscious customers, enhance their competitiveness, and seize business opportunities in the growing sustainability market. Furthermore, credibility plays a crucial role in establishing trust with stakeholders. Through decarbonization efforts, organizations aim to build trust with investors, regulators, and the general public, fostering long-term relationships and mitigating reputational risks. Interestingly, credibility seems to serve as a powerful source of internal justification for pursuing decarbonization initiatives, as organizations assume a correlation between business success and credibility in the context of sustainability and climate action.

Strategies

The second level of investigation focuses on the strategic alignment between organizational business-travel needs and decarbonization commitments. The research reveals a prevalent disconnect in the cases under study, as commitments are made but not effectively integrated into organizational strategy, particularly regarding the organization–traveler relationship. The paper highlights three central themes: organizational barriers, the responsibility dilemma, and the commitment-policy gap, shedding light on the challenges of achieving strategic alignment when decarbonizing business travel.

Organizational barriers

It becomes apparent how strongly business travel is institutionalized within the knowledge organizations under study. This mainly concerns “soft” factors, which represent genuine organizational hurdles to decarbonization. Autonomy is a salient characteristic of all the knowledge-intensive service organizations included in the analysis. It is important for business travel in the case-study organizations on several levels. On the one hand, it concerns individuals – i.e. the fact that many employees in these organizations have a great deal of decision-making autonomy related to business travel. At the same time, this also applies to individual departments or divisions. On the other hand, this autonomy is institutionalized both informally in the form of employees’ self-perceptions and formally through strategies, structures, and processes. In all organizations, one finds the institutionalization of business travel is a habit or norm, ensuring that business travel is informally embedded as an integral part of the organization—not only among current or future employees but among the executives responsible for implementing decarbonization commitments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected established practices in all the cases I studied, especially in terms of the virtual substitution of business travel, which the former are looking to leverage to increase business-travel decarbonization. However, in the case-study organizations, concerns are being expressed about how this "new normal" can be permanently institutionalized if a return to old habits becomes possible. Overall, the exploration shows that the transition to low-carbon business-travel practices requires a fundamental cultural change and thus must be treated as a change management issue and that various hurdles to this strong institutionalization are generated, as will be explained subsequently.

Responsibility dilemma

The autonomy described earlier is also weighted very highly in organizations when implementing business-travel decarbonization. This results in what I refer to as the responsibility dilemma. At the core of the issue is the question of who is ultimately responsible for business-travel emissions and, consequently, for reducing them: the organization or its employees? The same issue can be identified in all the case studies. When the organizations explain their decarbonization commitments, they refer to their corporate responsibility. The analysis suggests this is a direct reaction to the pressure on organizations to take climate-related action. However, in all our cases, ultimately, employees are perceived as being responsible for implementation, indicating a mismatch in the strategic decarbonization process.

Commitment-policy gap

The pronounced culture of autonomy in the organizations described above, as well as the unresolved question of responsibility, result in the fact that in all case-study organizations, decarbonization commitments are hardly reflected in concrete and, above all, enforceable organizational policies. Occasionally, organization-wide travel guidelines exist, but these are more in the form of recommendations and can be ignored without sanction by largely autonomous employees. The desire of managers to avoid negative reactions or harm to performance appears to be an important factor here, yet there is no evidence of this occurring at any of the case-study organizations. Regarding the autonomy of individual departments, however, at all organizations, some of the latter have issued their own directives that go beyond organization-wide guidelines. This points to growing internal inequality regarding decarbonization.

The prerequisite for implementing measurable business-travel emission reduction policies is the availability of data, which is currently still an obstacle in the smallest organization that was investigated, while the rest already have appropriate measurement and reporting systems in place. In this sense, business-travel decarbonization relies on sufficient organizational resources. This commitment-policy gap shows that, overall, decarbonization commitments are still insufficiently aligned with overall corporate strategy and that unrestricted service delivery capability remains the priority. Although all the organizations that were studied fundamentally acknowledge their responsibility for decarbonization and publicly confirm it through various commitments (some even having the ambition to take a leadership role in this regard), there is always a basic expectation (or hope?) that the government will issue binding regulations.

Measures

The third and final level of inquiry described in this paper is the tangible implementation of decarbonization commitments. Concerning emphasis on the traveler–traveler relation, I find examples here from both overarching categories of measures: behavior-based ones, which rely on travelers changing their behavior to reduce emissions (e.g. adjustments in travel arrangements, choice of mode of travel, and virtual substitution), and non-behavioral measures (e.g. compensation solutions or climate tech). Below, I review the dominant themes identified from the case studies, namely, non-behavioral measures and virtual substitution.

Non-behavioral measures

In all the case studies, non-behavioral measures are central to actions taken or planned. Overall, both classic nature-based solutions (offsetting) and climate tech (sustainable aviation fuel, direct carbon capture) are more widespread than pursuing changes in travelers’ behavior. First, achieving behavior change among business travelers in an organization is perceived to be challenging. It is evident that not all parts of the organizations want to change, and, in some cases, they openly oppose this. Immediate action is being taken almost solely by introducing non-behavioral measures or voluntary climate-related travel policies. Second, the targets (in particular, their time horizon) of all our cases are ambitious, and management perceives that using offsets is the only way to achieve them, given the short time needed for institutional change. Third, three of the organizations have a direct connection to emerging climate technologies through research, consulting, or investment activity. As a result, there is considerable knowledge of and great confidence in the technologies.

Ultimately, in the long term, classical offsets are seen as necessary by all organizations for eliminating residual emissions that have been declared unavoidable. From the organizational explanations for offsetting, it remains unclear which offsets are only used to eradicate effectively non-avoidable emissions. What counts as unavoidable and who defines this is not clear either. Thus, it is also not transparent in all cases whether classic offsets are a quick fix or the missing piece of the puzzle for achieving net zero. In the case of new sustainable aviation fuels, the role of quick fixes seems clearer. If their use were fully incorporated into GHG accounting, the interviews strongly suggested that changing organizational business-travel behavior for environmental reasons could be seen as even less necessary from a managerial point of view.

Virtual substitution

The last salient topic in the area of measures is the virtual substitution of business travel—for example, by video conferencing. In all case-study organizations, implementing this behavioral measure has been strongly driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. When travel was not possible, virtual exchange was the best alternative to physical exchange, and the perceived scope of opportunities for organizations’ service delivery expanded significantly. The CO2 inventories of the knowledge organizations significantly declined due to substitution in the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. By now, the virtual provision of business services (previously unthinkable) and simply maintaining some of these new applications represent a seemingly simple and relatively "painless" behavioral change that can reduce emissions in line with decarbonization commitments. The case studies show that virtual substitution does indeed have a place in any package of measures. However, the primacy awarded to flawless service delivery at the case-study organizations leads to reservations about the former’s far-reaching, permanent substitution. Consequentially, it is challenging for organizations not to return to the status quo concerning travel behavior. While substitution results in various claimed additional co-benefits (cost reduction, increases in efficiency) for organizations, in addition to emission savings, the virtual alternative is associated with clear limits in the case of organizations. The institutionalized preferences and habits of employees and customers appear to stand in the way of permanent change.

Relationships of themes on reasons, strategies, and measures

To conclude the analysis of the status quo, the qualitatively developed themes are now considered in the context of the different relationship levels of business travel and graphically presented in . Looking first at the causes of the decarbonization of business travel, the focus is on the organization-environment relationship concerning the two topics of pressure and credibility. Decarbonization commitments mainly originate from an external outside-in perspective. Further, the case studies reveal a lack of strategic integration of decarbonization. Problems in the organization–traveler relationship become apparent as a cause. These include the combination of the accentuation of the desire for autonomy, the normalization of business travel as an organizational hurdle, and unclarified responsibilities concerning the implementation of commitments. This leads to a mismatch between high-level commitment and the necessary implementation in terms of enforceable policies. This pronounced emphasis on personal responsibility is indicative of the strong focus on the traveler–traveler relationship. That is, business travelers should be enabled to make good decisions insofar as they are associated with impeccable service delivery and to protect employee satisfaction. This leads to the significant role of external, non-behavioral measures. Virtual substitution is also a major post-pandemic subject, but due to the importance of the traveler dimension and the latter’s preferences, its institutionalization is fragile. Taken as a whole, this raises substantiated doubts concerning whether and how relevant business-travel decarbonization can be achieved without major changes to the status quo.

Discussion

Business travel decarbonization in knowledge organizations

While the literature on academic business travel has focused on emissions analysis (Achten et al., Citation2013; Ciers et al., Citation2018; Klöwer et al., Citation2020), mitigation strategies (Hopkins et al., Citation2016; Klöwer et al., Citation2020), the importance of business travel (Chalvatzis & Ormosi, Citation2021; Kreil, Citation2021; Seuront et al., Citation2021) and factors underlying travel emissions (Higham & Font, Citation2020; Higham et al., Citation2019; Le Quéré et al., Citation2015) in recent years, there has been limited engagement with business travel in private sector entities (El Geneidy et al., Citation2021; Poom et al., Citation2017; Robèrt, Citation2009). However, the grey literature provides several valuable insights using various perspectives on business travel decarbonization (American Express Global Business Travel, Citation2022; GBTA Foundation, Citation2023; McCain et al., Citation2021; Skift Research, & McKinsey & Company, Citation2022). In addition, various organizations publish their own goals, strategies, and, in some cases, experiences with business travel decarbonization. Although sharing best practices is certainly to be supported, given the mixed results, caution is advised when interpreting these publications.

The case studies described in this paper confirm prior knowledge that business travel emissions significantly contribute to carbon emissions in knowledge organizations. El Geneidy et al. (Citation2021) rightly emphasize the challenges of comparing detailed studies on carbon emissions but estimate that travel accounts for 79% of emissions in knowledge organizations. Studies specifically focused on universities estimate that general mobility represents a substantial portion of academic emissions, ranging from 63% to 75% (Achten et al., Citation2013; Wynes & Donner, Citation2018). Estimations are that air travel emissions account for around 13% of total emissions associated with the universities in our sample. However, differences in measurement and context must be acknowledged, as highlighted by El Geneidy’s critique of comparability. In our sample, the insurance company’s Scope 3 emissions contribute approximately 70% of the total carbon emissions, with air travel alone accounting for 15%. The management consultancy reported that a staggering 83% of its carbon footprint is derived from business travel. Despite minor differences in ownership, funding mechanisms, and core business models among the cases, I found that the identified themes were present across all organizations. To some extent, the unexpected coherence reinforces the notion of considering universities and other knowledge organizations a collective entity when addressing business travel decarbonization.

External drivers of business travel decarbonization

The results clearly reveal the dominance of externally driven commitments, and the focus is on the environment–organization relationship. The urgency of responding to climate change is increasingly recognized by society, leading to growing demand for action from governments and organizations (UNDP, Citation2021). This demand is not limited to external entities but extends to customers, employees, and even funders of organizations (Amini & Bienstock, Citation2014; Baumgartner & Ebner, Citation2010; Wolf, Citation2014). It highlights the significance of external pressure as a driving force for change in organizations (Comello et al., Citation2021). However, the extent to which this pressure will result in shifts in decision-makers’ attitudes remains uncertain. Delmas and Burbano (Citation2011) even emphasize that external pressure from market and non-market actors often serves as a key driver of greenwashing. There is an emerging academic debate about whether science-based targets can be considered effective with regard to private climate regulation (Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023; Foerster & Spencer, Citation2023). Nonetheless, the long-term effectiveness and seriousness of these commitments cannot definitely be judged at present since the target dates are yet to be reached for all organizations under study. It therefore seems appropriate to observe how this pressure and these commitments materialize, especially as there are growing concerns that many net-zero pledges may fall short (Arnold & Toledano, Citation2021; Comello et al., Citation2021; Giesekam et al., Citation2021; United Nations Climate Action, Citation2022).

For knowledge organizations, credibility plays a pivotal role in service delivery. The intangibility of their services necessitates the cultivation of credibility, with the behavior and knowledge conveyed by organizations needing to align seamlessly in the context of service provision (Bieger, Citation2007; Poom et al., Citation2017). In the case of universities, for instance, conducting research and teaching about climate solutions is expected to be congruent with organizational behavior (Higham & Font, Citation2020). Similarly, management consultancies that claim expertise in climate change advisory services are required to act accordingly. From a risk management perspective, insurance companies also stress climate protection to minimize potential losses from insured events, thus making climate action crucial for meeting customer expectations. Beyond external pressures, the pursuit of credibility serves as a source of justification within the investigated organizations. The close linkage between business success and credibility allows management to advocate for decarbonization by emphasizing the business case for action (Dyllick & Hockerts, Citation2002). This line of reasoning was observed across all the studied cases, enabling organizations to frame the issue strategically and potentially overcome internal resistance. By recognizing decarbonization efforts as a strategic opportunity, organizations can bridge the gap between costs and benefits, fostering more sustainable practices (Porter & Van Der Linde, Citation1995a, Citation1995b). The importance of credibility is also underscored by the UN’s convening a group of experts to review the commitments of state and non-state actors (United Nations’ High‑Level Expert Group, Citation2022).

Strategic misalignment of business travel decarbonization

Addressing the alignment of business-travel requirements with decarbonization commitments at a strategic level is a complex endeavor for organizations. Whelan and Fink (Citation2016) argue that integrating sustainability into business strategy can drive innovation and engender enthusiasm and loyalty from employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and investors. However, the examined cases reveal a notable gap between the commitments made by organizations and how they are embedded into organizational strategy, particularly concerning the organization–traveler relationship. This mirrors the findings of Perino et al. (Citation2022) and Arnold and Toledano (Citation2021), which also identify the significant disconnect between commitments and action. Only about 20% of net-zero targets meet basic robustness criteria (Black et al., Citation2021). Even organizations that are under significant public pressure rarely integrate their climate and business strategies (Foerster & Spencer, Citation2023). Baumgartner and Rauter (Citation2017) attribute this gap to the lack of a strategic orientation in corporate sustainability management, which hampers progress in this field. The lack of strategic integration also raises questions about efficiency and resource utilization (such as when multiple departments independently determine travel policies and goals). The heterogeneity of decarbonization approaches within organizations may lead to imbalances and fairness concerns.

Two of the identified themes serve as possible explanations for this gap. One significant challenge to business travel decarbonization efforts is the organizational barriers deeply ingrained within service organizations. Business travel is institutionally embedded, granting decision-making autonomy to individuals and departments through cultural norms and formal strategies (Hoolohan et al., Citation2021; Hopkins et al., Citation2016). This institutionalization poses hurdles to decarbonization, despite the accelerated adoption of virtual alternatives due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Müller & Wittmer, Citation2023). Overcoming these barriers requires a fundamental cultural shift and effective change management strategies (Benn, Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2013; Poggioli & Hoffman, Citation2022). Another significant challenge pertains to the issue of unresolved responsibility among the various actors involved, a prominent concern of Bénabou and Tirole (Citation2010). While organizations emphasize corporate responsibility, implementation often falls to employees, who are influenced by their decision-making autonomy and the organization’s influence over them (Douglas & Lubbe, Citation2009, Citation2010; Müller, Citation2022). Addressing this dilemma requires persuasion, awareness-raising, and potentially external regulations that ensure collective action (Bénabou & Tirole, Citation2010).

In sum, the unresolved responsibilities and the lack of enforceable organizational policies in the dominant organization–traveler relationship are highly problematic. Travel guidelines often remain mere recommendations, and managers may hesitate to enforce stricter policies due to concerns about negative reactions or performance issues (Kreil & Stauffacher, Citation2021). Effective policies and government regulations are needed to address the personal responsibility of travelers and ensure fairness and progress in decarbonization efforts, even if they call business travel into question (Davies & Dunk, Citation2015; Glover et al., Citation2017; O’Neill & Sinden, Citation2021)

Implementation of business travel decarbonization measures

Non-behavioral measures, such as offsetting and climate tech, play a central role in the case studies, surpassing the pursuit of behavior change among travelers. The results confirm previous work that in particular has identified and criticized the important role of offsets (Comello et al., Citation2021; Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023; Walls, Citation2022). This preference for non-behavioral measures can be attributed to the challenges associated with changing traveler behavior within organizations where frequent business travel is deeply institutionalized. Focusing on the traveler–traveler relationship and delegating responsibility for implementing measures to employees leads to an over-emphasis on offsets. Additionally, ambitious targets and the immediate need for institutional change lead to the use of offsets as a quick and simple means of achieving decarbonization goals. Last, knowledge organizations’ connections with climate technology enhance their knowledge and confidence in these technologies and fuel their (self-)interest in their application, thereby strengthening the perceived relevance of their activities. However, the strong reliance on non-behavioral strategies raises concerns about the legitimacy of offsets as the primary measure and the transparency involved in achieving net-zero targets (Walls, Citation2022). Nevertheless, classical offsets are considered indispensable in the long term for addressing residual emissions that are deemed unavoidable.

Virtual substitution, particularly through video conferencing, gained traction as a behavioral measure during the COVID-19 pandemic (Becken & Hughey, Citation2022; Jack & Glover, Citation2021; Klöwer et al., Citation2020; Müller & Wittmer, Citation2023; Wassler & Fan, Citation2021). It has offered organizations a viable alternative to physical travel and expanded the scope of service delivery opportunities while significantly reducing CO2 inventories. Engaging in the virtual provision of business services represents a relatively simple and effective behavioral change aligned with decarbonization commitments. However, organizations face challenges maintaining the shift to virtual substitution as employees’ and customers’ entrenched preferences and habits may hinder permanent change (Poggioli & Hoffman, Citation2022). While virtual substitution is associated with additional benefits such as cost reduction and increased efficiency, organizational barriers and the priority placed on flawless service delivery can impede its long-term implementation (Müller & Wittmer, Citation2023).

Striking a balance between non-behavioral measures and sustainable behavioral changes remains crucial for achieving decarbonization goals and addressing the limitations and consequences of different approaches (Lindeblad et al., Citation2016). This also requires overcoming “technology myths” (Peeters et al., Citation2016), which are slowing down the changes that are necessary for authentic, sustainable transformation.

Business travel decarbonization framework

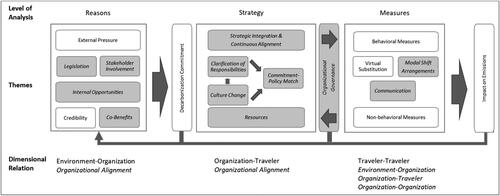

How can knowledge organizations effectively decarbonize business travel based on the status quo? conceptualizes what changes (shaded) are necessary to achieve this.

Figure 3. Desirable state of business-travel decarbonization in knowledge organizations (Author’s construction).

First, organizations should not perceive decarbonization only as an external necessity. From an inside-out perspective, decarbonization can be viewed as an opportunity for new business models, processes, and value creation with customers through internal organizational alignment, as described by Porter and Van Der Linde (Citation1995a), as is already partly being done in pursuit of credibility. Other co-benefits (costs, efficiency, employee health, etc.) are conceivable drivers (Cohen & Kantenbacher, Citation2020). Second, the external influence remains a source of motivation. Instead of reacting to pressure, the many heterogeneous stakeholder groups in the broader environment should be (pro-)actively integrated and managed in a targeted stakeholder involvement process, as has been previously suggested (Delgado-Ceballos et al., Citation2012; Gustafson, Citation2012; Pucci et al., Citation2020). Despite organizational efforts, government regulation on the topic will likely follow, as private climate regulation alone is unlikely to be sufficient for achieving timely and ambitious climate action (Foerster & Spencer, Citation2023). Trexler and Schendler (Citation2015) therefore conclude that: “companies [cannot] substitute for public policy when it comes to addressing the fundamental economic externality that is leading to climate change” (p. 933). As such regulation is also considered desirable for promoting decarbonization by the organizations I studied, organizations should become actively involved in the legislative process. However, the type and scope of desired regulation and its effect on organizations’ operations must first be clarified. Therefore, in addition to the currently dominant themes that predominantly focus on the environment–organization relationship, organizational alignment must also be considered, as strong reasons for decarbonizing business travel emerge from this relationship dimension.

Third, in the area of business-travel decarbonization strategy, it is also paramount that organizational alignment takes place. Ongoing general and decarbonization strategy processes must be aligned so that their goals no longer conflict. Accepting and addressing the fact that this may require far-reaching changes to the current service-creation logic is imperative, as claimed by Hahn et al. (Citation2015). The provision of sufficient financial, organizational, and human resources for decarbonization is a prerequisite for success. Fourth, concrete and enforceable policies must ensure a fit between commitments and implementation in the organization–traveler relationship. For this, responsibilities must first be clarified and defined. Organizations are not likely to be able to avoid exerting greater influence on the behavior of their employees, creating potential issues with policy compliance, as outlined by Holma et al. (Citation2015) and Douglas and Lubbe (Citation2010). Whether and how this influence can be reconciled with the culture of autonomy associated with business travel must be clarified. A change in the prevailing organizational business-travel culture and the associated behavior change becomes plausible only through clearly communicated and enforced adjustments in travel policies.

Fifth, there is a need for appropriate corporate governance that links the strategic level with the implementation of measures. This involves deploying instruments to address long-term decarbonization issues, including target-setting, internal carbon accounting, pricing, and independent reporting (Lister, Citation2018; Lloret, Citation2016; Robinson et al., Citation2015). Sixth, when it comes to measures, this should not remain a matter of the traveler–traveler dimension alone, as is currently the case. Instead of delegating responsibility for implementing decarbonization commitments to employees, organizations must assume responsibility for taking action. This requires rethinking the organization–traveler relationship. When organizations assume responsibility for reducing business-travel emissions, two additional topics in the area of behavioral measures need to be addressed: further adjustments in travel behavior, such as modal shifts and changes to travel arrangements (insofar as trips are non-substitutable). In this respect, measures are not to be considered in isolation but always collectively, and their appropriateness in the specific situation should be taken into account. The measures need to be communicated transparently and frequently, mainly because of travelers’ high degree of autonomy, to maintain employee buy-in and facilitate cultural change. Finally, seventh, concerning the effectiveness of measures, the organization-organization relationship is also relevant. This covers the areas of systemic dependencies associated with reducing business-travel emissions and the organization-environment, which covers interaction with or feedback from decarbonization efforts on the broader environment. In short, decarbonization is a continuous process, not a linear one, in which organizational measures impact future strategy and rationale.

Conclusion

Future research on business travel decarbonization

While this paper conceptualizes both the current and desirable state of business-travel decarbonization, it leaves open some intriguing areas for further research. First, the chosen research approach and the resulting model do not allow for conclusions about causality. However, such causal relationships should be further investigated. Second, the responsibility dilemma should be explored in more depth (i.e. how can the responsibilities for business-travel emissions be determined and assigned, and how does this affect mitigation policies?). Third, and related to the previous point, how can organizations most effectively influence travel behavior, and does exerting influence through policies trigger employee resistance? Are there differences in this regard between different measures? Fourth, it would be desirable to examine what, if any, effects there are on public perceptions of credibility if pledges are not fulfilled or are fulfilled only through offsets. Non-behavioral measures also potentially impact employee behavior. Is there a potential rebound effect on travelers if an organization offsets its emissions? Data and analyses of business travel emissions in (knowledge) organizations are generally scarce, representing another important and urgent research opportunity.

Implications for academia and practice

Decarbonizing business travel is an important contribution that knowledge organizations have to make in the context of the shift to net zero and to help achieve tourism-related sectoral climate targets. The four case studies of knowledge organizations committed to sustainability goals reveal three key insights for scholars and practitioners interested in business-travel decarbonization.

First, the in-depth analysis of reasons, strategies, and measures reveals the limitations of voluntary decarbonization. Even in organizations that have pledged to reduce carbon emissions, implementation is generally slow, delayed, and unstructured. In light of the related progress in the examined cases, the question justifiably arises whether voluntary commitments should be replaced or complemented by regulatory compliance, as has been suggested previously (Esty & de Arriba-Sellier, Citation2023; Foerster & Spencer, Citation2023; Southworth, Citation2009; Trexler & Schendler, Citation2015). While it is clear that policy changes can alter travel behavior (McKercher et al., Citation2010) and meaningfully reduce associated emissions (Le Quéré et al., Citation2020), the nature and extent of the required regulation remain uncertain. However, as pointed out by Gössling et al. (Citation2023), “without worldwide policy efforts […] tourism will turn into one of the major drivers of climate change” (p. 1). Second, it has not yet been clarified which actor(s)—organizations or travelers—bear responsibility for reducing business-travel-related emissions. While the partial responsibility of autonomous business travelers cannot be denied, it is still up to organizations to implement tangible measures to reduce the travel emissions caused by their business activities. So far, this is hardly the case, so the fulfillment of the pledges is hindered. Discourse that addresses the question Bénabou and Tirole (Citation2010) raise (who—the individual, organization, or state—is responsible for what?) must be encouraged not only on an academic but also on a socio-political level. Third, a transition is needed from non-behavioral, outsourcing, and technology-driven approaches to changes in business-travel behavior—thus, in the logic of how knowledge organizations deliver services globally. Without such far-reaching changes, the decarbonization of business travel in service organizations is not plausible.

This paper makes several contributions. Academically, it fills a gap in the understanding of business-travel decarbonization. In addition to conceptualizing current states and mechanisms and taking into account relevant systemic interdependencies between travelers, organizations, and the environment, it presents a holistic conceptual model that increases the theoretical understanding of business-travel decarbonization. In practical terms, the paper suggests how successful decarbonization may be achieved in knowledge organizations concerning the interplay among reasons, strategies, and measures and provides concrete recommendations for action for organizations and policymakers, thereby contributing to the success of decarbonization efforts in the sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Achten, W. M. J., Almeida, J., & Muys, B. (2013). Carbon footprint of science: More than flying. Ecological Indicators, 34, 352–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.05.025

- Aguiléra, A. (2014). Business travel and sustainability. In Gärling, T., Ettema, D., Friman, M. (eds) Handbook of sustainable travel (pp. 215–227). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Aguiléra, A., & Proulhac, L. (2015). Socio-occupational and geographical determinants of the frequency of long-distance business travel in France. Journal of Transport Geography, 43, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.01.004

- American Express Global Business Travel. (2022). 5 steps to reduce emissions from business travel. Retrieved from https://www.amexglobalbusinesstravel.com/the-atlas/reduce-emissions-from-business-travel/

- Amini, M., & Bienstock, C. C. (2014). Corporate sustainability: An integrative definition and framework to evaluate corporate practice and guide academic research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 76, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.016

- Andersen, I., Ishii, N., Brooks, T., Cummis, C., Fonseca, G., Hillers, A., Macfarlane, N., Nakicenovic, N., Moss, K., Rockström, J., Steer, A., Waughray, D., & Zimm, C. (2021). Defining ‘science-based targets. National Science Review, 8(7), nwaa186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa186

- Arnold, J., & Toledano, P. (2021). Corporate net-zero pledges: The bad and the ugly. Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment Staff Publications.

- Aslesen, H. W., & Isaksen, A. (2007). New perspectives on knowledge-intensive services and innovation. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 89(Suppl. 1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2007.00259.x

- Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556363

- Baumgartner, R. J., & Ebner, D. (2010). Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustainable Development, 18(2), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.447

- Baumgartner, R. J., & Rauter, R. (2017). Strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop a sustainable organization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.146

- Beaverstock, J. V., Derudder, B., Faulconbridge, J., & Witlox, F. (2010). International business travel and the global economy: Setting the context. In J. V. Beaverstock, B. Derudder, J. Faulconbridge, & F. Witlox (Eds.), International business travel in the global economy (pp. 1–7). Ashgate.

- Beaverstock, J. V., Derudder, B., Faulconbridge, J. R., & Witlox, F. (2009). International business travel: Some explorations. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 91(3), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2009.00314.x

- Beaverstock, J. V., & Faulconbridge, J. (2010). Official” and “unofficial” measurements of international business travel to and from the United Kingdom: Trends, patterns and limitations. In J. V. Beaverstock, B. Derudder, J. Faulconbridge, & F. Witlox (Eds.), International business travel in the global economy. Farnham: Ashgate (pp. 57–84). Ashgate.

- Becken, S., & Hughey, K. F. (2022). Impacts of changes to business travel practices in response to the COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1894160

- Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. E. A. N. (2010). Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica, 77(305), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x

- Benn, S. (2014). Organizational change for corporate sustainability. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315819181

- Bieger, T. (2007). Dienstleistungs-Management: Einführung in Strategien und Prozesse bei persönlichen Dienstleistungen (4th ed.). Haupt.

- Black, R., Cullen, K., Fay, B., Hale, T., Lang, J., Mahmood, S., & Smith, S. M. (2021). Taking Stock: A global assessment of net zero targets, https://ca1-eci.edcdn.com/reports/ECIU-Oxford_Taking_Stock.pdf.

- Borko, S., Geerts, W., & Wang, H. (2020). The travel industry turned upside down: Insights, analysis, and actions for travel executives. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/the-travel-industry-turned-upside-down-insights-analysis-and-actions-for-travel-executives

- Bumpus, A. G., & Liverman, D. M. (2008). Accumulation by decarbonization and the governance of carbon offsets. Economic Geography, 84(2), 127–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.tb00401.x

- Caritte, V., Acha, S., & Shah, N. (2015). Enhancing corporate environmental performance through reporting and roadmaps. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(5), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1818

- Caset, F., Boussauw, K., & Storme, T. (2019). Meet & fly: Sustainable transport academics and the Chock for elephant in the room’ (vol 70, pg 64, 2018). Journal of Transport Geography, 74, 413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.12.006

- Chalvatzis, K., & Ormosi, P. L. (2021). The carbon impact of flying to economics conferences: Is flying more associated with more citations? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 40–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1806858

- Ciers, J., Mandic, A., Toth, L., & Op ‘t Veld, G. (2018). Carbon footprint of academic air travel: A case study in Switzerland. Sustainability, 11(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010080

- CO2-Emissionen des Luftverkehrs. Grundsätzliches und Zahlen. (2020). Federal Office of Civil Aviation (FOCA). https://www.bazl.admin.ch/dam/bazl/de/dokumente/Politik/Umwelt/co2_emissionen_grundsaetzliches_zahlen.pdf.download.pdf/CO2-Emissionen_des_Luftverkehrs.pdf

- Cohen, S. A., & Gössling, S. (2015). A darker side of hypermobility. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(8), 166–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15597124

- Cohen, S. A., Hanna, P., & Gössling, S. (2018). The dark side of business travel: A media comments analysis. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 61, 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.01.004

- Cohen, S. A., & Kantenbacher, J. (2020). Flying less: Personal health and environmental co-benefits. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(2), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1585442

- Comello, S., Reichelstein, J., & Reichelstein, S. (2021). Corporate carbon reduction pledges: An effective tool to mitigate climate change? SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3875343

- Cox, E., & Johnson, L. (2021). State of Climate Tech 2021. Scaling breakthroughs for net zero. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/publications/state-of-climate-tech.html

- Dahlmann, F., Branicki, L., & Brammer, S. (2019). Managing carbon aspirations: The Influence of corporate climate change targets on environmental performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3731-z

- Davies, J. C., & Dunk, R. M. (2015). Flying along the supply chain: Accounting for emissions from student air travel in the higher education sector. Carbon Management, 6(5-6), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2016.1151503

- Davies, Z. G., & Armsworth, P. R. (2010). Making an impact: The influence of policies to reduce emissions from aviation on the business travel patterns of individual corporations. Energy Policy, 38(12), 7634–7638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.09.007

- Defrank, R. S., Konopaske, R., & Ivancevich, J. M. (2000). Executive travel stress: Perils of the road warrior. The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005), 14(2), 58–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4165635

- Delgado-Ceballos, J., Aragón-Correa, J. A., Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N., & Rueda-Manzanares, A. (2012). The effect of internal barriers on the connection between stakeholder integration and proactive environmental strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1039-y

- Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

- Delmas, M. A., & Montes-Sancho, M. J. (2009). Voluntary agreements to improve environmental quality: Symbolic and substantive cooperation. Strategic Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.826

- Delmas, M. A., & Toffel, M. W. (2008). Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29(10), 1027–1055. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.701

- Denstadli, J. M. (2004). Impacts of videoconferencing on business travel: The Norwegian experience. Journal of Air Transport Management, 10(6), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2004.06.003

- Denstadli, J. M., & Gripsrud, M. (2010). Face-to-face by travel or picture: The relationship between travelling and video communication in business settings. In: Beaverstock, J., Derudder, B., Faulconbridge, J. & Witlox, F. (eds.) International Business Travel in the Global Economy. Farnham, UK : Ashgate

- Denstadli, J. M., Gripsrud, M., Hjorthol, R., & Julsrud, T. E. (2013). Videoconferencing and business air travel: Do new technologies produce new interaction patterns? Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 29, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2012.12.009

- Denstadli, J. M., Julsrud, T. E., & Hjorthol, R. J. (2012). Videoconferencing as a mode of communication:A comparative study of the use of videoconferencing and face-to-face meetings. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651911421125

- Derudder, B., Beaverstock, J. V., Faulconbridge, J. R., Storme, T., & Witlox, F. (2011). You are the way you fly: On the association between business travel and business class travel. Journal of Transport Geography, 19(4), 997–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.01.001

- Douglas, A., & Lubbe, B. A. (2009). Violation of the corporate travel policy: An exploration of underlying value-related factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9676-5

- Douglas, A., & Lubbe, B. A. (2010). An empirical investigation into the role of personal-related factors on corporate travel policy compliance. Journal of Business Ethics, 92(3), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0167-0

- Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.323

- El Geneidy, S., Baumeister, S., Govigli, V. M., Orfanidou, T., & Wallius, V. (2021). The carbon footprint of a knowledge organization and emission scenarios for a post-COVID-19 world. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 91, 106645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106645