Abstract

Despite a great deal of recent scholarly attention devoted to prosocial behaviors in tourism, its central antecedents from a socio-psychological and cultural perspective remain unknown. Using key socio-cultural constructs (cultural worldviews, perceived social relations, and self-esteem), this research examines a baseline model and compares it with a competing model to highlight alternative theoretical possibilities. We employ the face negotiation theory, the theory of reciprocal altruism, the sociometer theory, and the terror management theory to disentangle these relationships highlighting self-esteem’s significant role. The results are based on a survey of 403 tourists in a popular tourist destination in Asia, Macau. In the better-fitted model, findings demonstrate that while cultural worldviews and perceived social relations significantly predict prosocial behaviors, self-esteem moderates the extent to which both cultural worldviews and perceived social relations would trigger prosocial behaviors. These findings contribute valuable theoretical, methodological, and practical insights into the relationships among prosocial behavior and its socio-cultural antecedents.

Introduction

Given the increasing need for tourism to foster socially sustainable behaviors and meaningful travel relationships (Fan, Citation2023; Tung, Citation2019), it is important to understand behavioral pathways for promoting tourism as a socially sustainable tool. Tourists’ prosocial behaviors have been argued as desirable action that contributes to both human and environmental well-being (Han et al., Citation2020; Kim & Michael Hall, Citation2022). Along with this argument, a growing number of studies focuses on how to promote altruistic behaviors in the tourism context since such behaviors matter for the sustainability of destinations and communities (Agyeiwaah & Bangwayo-Skeete, Citation2022; Chi et al., Citation2022; Zhu et al., Citation2022). Other prior studies have explored prosocial behaviors integrating the Norm Activation Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior (e.g. Esfandiar et al., Citation2020; Meng et al., Citation2020) and it is known from these studies that social factors such as subjective well-being plays a significant moderating role between prosocial behavioral intentions and some of its antecedents. However, how cultural worldviews and social relations jointly influence tourists’ prosocial behaviors is still largely unknown. Specifically, do cultural worldviews impact perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors? If so, how? Given that prosocial behaviors essentially reflect altruism (Pfattheicher et al., Citation2022; Tung, Citation2019), and cultural values could affect how individuals interpret the meaning of relationships with others (Hofstede, Citation2001), investigating the relationship between cultural worldview and prosocial behaviors would make an important contribution toward understanding the sustainability of tourism.

Cultural worldviews and values can largely affect personal behaviors in the tourism context (Megeirhi et al., Citation2020; Reisinger & Crotts, Citation2010). Both studies on residents’ intention to support cultural heritage tourism, and tourist decision-making process for visiting cultural heritage sites all indicate that cultural worldviews impact attitudes without explaining social behaviors (Lee et al., Citation2020; Megeirhi et al., Citation2020). Although some studies attempted to explain tourists’ prosocial behaviors with cultural factors (e.g. Wu et al., Citation2023), the specific mechanism of how social relations influence such behaviors is still unclear. In particular, previous studies usually asserts that tourists independently conduct prosocial behaviors and neglect social relations formed during the journey. Fennell (Citation2006) argues that altruistic behaviors in tourism based on the interaction quality and some ethical and educational strategies could help stabilize reciprocal relationships. Considering that developing social relations and interacting with locals are becoming the main motivations for some travelers (Kuo et al., Citation2019), especially in (cross-)cultural tourism, it is beneficial to examine the combined role of cultural worldviews and social relations in promoting tourists’ prosocial behaviors.

Furthermore, while self-esteem can influence how people react in social circumstances, its effect on prosocial behaviors is largely overlooked in the tourism literature. Many studies have investigated the importance of self-esteem on prosocial behaviors in various contexts and backgrounds (e.g. Jami et al., Citation2021), and some longitudinal studies provide evidence of its impact (see Fu et al., Citation2017). According to the sociometer theory (Leary, Citation2005), self-esteem monitors the quality of an individual’s interpersonal relationships and motivates behavior that helps maintain a minimum level of acceptance by others (Leary & Baumeister, Citation2000). With the intervention of self-esteem, individuals differently interpret social interactions (Wang et al., Citation2021). Thus, given this theoretical understanding, an overlook of the role of self-esteem may lead to an incomplete understanding of prosocial behaviors. For example, Wu et al. (Citation2023) suggested that tourists would adopt distinct action strategies in response to others’ uncivil behavior depending on the type of social relations. However, their study ignored individual psychological features and fail to explain why there are differences in prosocial behavior strategies even in the same social relations. By considering the moderated role of self-esteem, this study incorporates the effects of cultural values, social interactions, and individual differences on prosocial behavior, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding. We extend previous studies by unraveling the question - Would the relationship among cultural worldviews, social relations, and prosocial behaviors be dependent on self-esteem evaluations? In addressing this research gap, the current study presents three research objectives as follows:

Examine the relationships between cultural worldviews, perceived social relations, and prosocial behaviors;

Investigate the moderating role of self-esteem on the indirect relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors; and

Examine a competing model of direct relationships among cultural worldviews, perceived social relations, self-esteem, and prosocial behaviors.

As part of achieving these objectives and providing alternative explanations for the observed data (Hair et al., Citation2010), this study compares two competing models to propose a fitting model that can better explain the relationship between prosocial behaviors and other socio-cultural variables. In doing so, this study contributes to theoretical development, in addition to practical and methodological advancements associated with the application of a competing model approach to understudied prosocial behavioral antecedents.

Literature review

Cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors

Cultural worldviews are defined as a socially constructed orientation reflecting general beliefs and attitudes to human-cultural relationships and it is a determinant of how a person interprets and interacts with society (Birkelund et al., Citation2022). According to terror management theory (TMT), which explains humans’ innate drive for self-preservation, cultural worldviews represent ‘humanly created symbolic perceptual constructions shared by groups of people to minimize the anxiety associated with the awareness of death’ (Solomon et al., Citation1991, p. 96). They denote pro-cultural attitudes (Choi & Fielding, Citation2016). Previous studies confirm that the need to preserve one’s cultural worldview and the awareness of contributing to such worldviews trigger prosocial behaviors (Goldenberg et al., Citation2001; Solomon et al., Citation1991). In this study, we conceptualize cultural worldview as “people’s underlying general attitudes such as basic beliefs and perceptions of a culture (Wei et al., Citation2020, p. 241).” Hence, we take an individual perspective, a widely applied approach (see Lee et al., Citation2020), to examine tourists’ perceptions of their cultures allowing us to examine its relationship with other constructs of interest.

At the individual level, cultural worldviews are crucial for analyzing conflict and cooperative behavior because they encompass and shape one’s beliefs about shared values and social norms (Cherry et al., Citation2019). Hofstede (Citation2001) argues that cultural values can affect individual behavior profoundly. For example, individuals in collectivist societies focus more on group relations and loyalty and are more willing to sacrifice personal interests for the group. Cherry et al. (Citation2019) argued that cultural worldviews are derived from cultural commitments which are more fundamental than any economic or political commitments (e.g. social identity or political ideology). Thus, cultural worldviews can essentially influence the individual’s cognitive and interpretative processes toward society and the action strategies adopted.

The influence of cultural worldview on behavioral strategy choice is multifaceted. In some studies, cultural worldview forms socialized norms that promote or constrain individual behavior. For example, Long et al. (Citation2022) found that cultural values and information campaigns jointly influence young Chinese consumers’ intention to waste food. Likewise, based on the value-belief-norm theory, Han (Citation2015) found that worldview can influence travelers’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions through perceptions of consequences and responsibilities. On the other hand, cultural worldviews can also influence the personal evaluation of potential risk, which in turn might affect action strategies. For instance, Xue et al. (Citation2016) demonstrate that cultural worldview can influence perceptions of risk and further influence policy support and behavioral intentions in the face of climate risk.

Furthermore, many studies provide evidence of the role of cultural worldview in prosocial behaviors (e.g. helping others, charity, or resource conservation). Martí-Vilar et al. (Citation2019) confirmed that high levels of collectivism, long-term orientation, and low levels of power distance are the best predictors of prosocial behavior among adolescents. Taking an identity perspective, Davis et al. (Citation2021) argued that many Latino family identities are rooted in an interdependent culture and revealed a general positive association between familism and various prosocial behaviors. Further evidence from terror management theory suggests that cultural worldviews and the sense of value in society can minimize death-related anxiety and affect individuals’ reactions to others, such as donation, defense, or even aggression against dissimilar others (Kheibari & Cerel, Citation2021). Hence, this study posits that:

H1: Cultural worldviews have a positive impact on prosocial behaviors.

In addition, individuals’ cultural worldview also influences the level of perceived social relations. Perceived social relations include evaluating social support, social connectedness, and trust (Xu, Citation2019). Wang and Zhang (Citation2021) found a direct effect of personal sociocultural awareness on perceived social support when entering a new environment. This effect is considered more evident in cross-cultural communication. For example, Forgas (Citation1988) argued that people from different cultures have different cognitive representations of social episodes, such as perceptions of closeness, involvement, and friendliness. In this vein, Ting-Toomey (Citation1988) proposed the Face-Negotiation Theory to explain relationship performance in cross-culture communications. According to this theory, members of collectivist high-context cultures care more about others and are more willing to develop good relationships with each other within the group by having a mutual face (Ting-Toomey, Citation1988). Grounded in this theory, the current study proposes that:

H2: Cultural worldviews have a positive impact on perceived social relations.

Perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors

Social relations refer to a series of social interactions and connections (Cohen, Citation2004). Many studies in social psychology focus on the relationship between social relations and prosocial behaviors. The theory of reciprocal altruism demonstrates this relationship from the perspective of social evolution. According to this theory, Trivers (Citation1971) pointed out that altruistic social behavior can occur between non-kin individuals if the beneficiary is expected to reciprocate in the future. Therefore, this system of altruism is accompanied by the expectation of reward, and stable and positive social relations are the basis for meeting the expectation (Fennell, Citation2006).

In tourism literature, some studies applied the theory of reciprocal altruism to explain issues involving social interaction and prosocial behaviors, such as host-tourist interactions (Fennell, Citation2006), host volunteering (Paraskevaidis & Andriotis, Citation2017), and community participation (Ghaderi et al., Citation2023). For example, Fennell (Citation2006) argued that the biggest challenge for prosocial behaviors in tourism is the limited time for interaction. He further suggested that forming friendships between hosts and tourists can promote altruistic behaviors.

Some studies provide evidence to support the positive effect of perceived social relations on prosocial behaviors. Nathan et al. (Citation2013) revealed that young people participating in sports groups and forming peer relationships showed a significantly higher level of prosocial behavior intention than the comparison group. Likewise, Wentzel and McNamara (Citation1999) found that peer acceptance was related directly to prosocial behavior. In the tourism context, some studies explored the relationship between tourist interaction and responsible behaviors (e.g. Lin et al., Citation2022). Coghlan (Citation2015) emphasizes that impersonal statement, which implies the positive effect of interpersonal relationships, co-occurs with prosocial behaviors for volunteer tourists. While these studies offer insights into the relationship between perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors, they fail to highlight the explanatory role of social relations in the relationship between cultural worldview and prosocial behaviors.

Meanwhile, perceived social relations can play a crucial role in the relationship between cultural worldview and prosocial behaviors. According to Hofstede (Citation2001), individualistic societies typically emphasize individual rights and liberties and place a strong emphasis on individual reward, which results in loosely connected social networks. In contrast, collectivist cultures promote harmony among group members, subordinate individual feelings to the overall interests of the team, and value the preservation of face. Among a collectivist group, Wang and Zhang (Citation2021) tested the mediating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between social face consciousness and help-seeking behaviors. Wu et al. (Citation2023) found that cultural values can affect the reaction to irresponsible tourism behavior of other tourists and social relations are the dominant factor for reaction strategies, such as persuading families, saving faces for friends, and ignoring strangers. Consequently, it is hypothesized that:

H3: Perceived social relations have a positive relationship with prosocial behaviors.

H4: Perceived social relations mediate the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors.

The role of self-esteem

Self-esteem refers to one’s overall evaluation of oneself and it is the core component of one’s identity (Cast & Burke, Citation2002). Many studies have investigated the effect of self-esteem on various psychological states and behaviors. For example, Pyszczynski et al. (Citation2004) suggest that pursuing self-esteem encourages many desirable outcomes, such as prosocial behaviors and creative achievement. However, it should be taken into account that the role of different types of self-esteem varies. Rosenberg et al. (Citation1995) argue that changing positive self-esteem or negative self-esteem, rather than global self-esteem, could help improve academic performance. Specifically, positive self-esteem can generate self-confidence while negative self-esteem linked with learned helplessness or self-deprecation causes poor performance. Many studies have found that self-esteem is positively related to prosocial behaviors (e.g. Jami et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2017). Some longitudinal studies give further evidence to this relationship. For instance, Fu et al. (Citation2017) found self-esteem was associated longitudinally with subsequent prosocial behavior toward strangers through a four-year tracking study. However, the knowledge about the combined effect of perceived social relation and self-esteem on prosocial behaviors is largely limited.

The sociometer theory contends that self-esteem is a subjective monitoring indicator of one’s social relations and that self-esteem motivates behaviors that help one maintain a minimum level of acceptance from others (Leary & Baumeister, Citation2000). This study argues that self-esteem could moderate the relationship between perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors. There are two reasons for hypothesizing the moderator role of self-esteem. First, the strength of the relationship between perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors may be influenced by self-esteem. Bednar and Peterson (Citation1995) argue that self-esteem level affects the probability and ability of social interactions. High self-esteem increases coping ability, while low self-esteem increases avoidance. Hence, tourists with higher perceived positive self-esteem are more likely to actively take altruistic actions during travel because of positive social relations. Tourists with negative self-esteem, on the other hand, may avoid taking the initiative as helping others as they may think their action is useless, even though they have a good relationship with others.

Second, people with positive or negative self-esteem may interpret their social relations as having a different meaning. According to the sociometric theory, one’s current level of self-esteem can moderate the personal perception of interpersonal feedback (Leary & Baumeister, Citation2000). Specifically, people with positive self-esteem tend to believe that others are more accepting of them than those with negative self-esteem. Some empirical studies revealed that people with negative self-esteem are anxious about being accepted by others and are more prone to interpret positive signals and episodes negatively, validating their negative perceptions of themselves (see Marigold et al., Citation2007). In contrast, Ma et al. (Citation2022) found that, with high positive self-esteem, high grit can buffer the negative effects of low autonomy support on prosocial behavior. Therefore, tourists with positive self-esteem will not only desire to act prosocial but also acquire self-confidence in their social interaction. This, thus, enhances the relationship between perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors. On the contrary, tourists with negative self-esteem may be less likely to offer unsolicited help for fear of being rejected and undermining the relationship (). According to this rationale, this study posits that:

H5: The indirect relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors via perceived social relations is moderated by different levels of positive self-esteem.

H6: The indirect relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors via perceived social relations is moderated by different levels of negative self-esteem.

While TMT provides a theoretical explanation of the connection between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors, the moderating role of self-esteem has been least examined even though, it serves as a key buffering system to anxiety by providing a sense of meaning and worth to the individual (Solomon et al., Citation1991; Zaleskiewicz et al., Citation2015). In this case, the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial is likely to vary across different levels of self-esteem whether positive or negative (). Hence, it is hypothesized that:

H7: There is a moderated mediating effect of positive self-esteem on the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors.

H8: There is a moderated mediating effect of negative self-esteem on the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors.

The relationship between perceived social relations and self-esteem (a sense of self-worth), has been given mixed theoretical explanations (Leary, Citation1999; Orth & Robins, Citation2022). From an ethological perspective, self-esteem serves as an adaptation mechanism evolving from the act of maintaining dominance in social relations (Barkow, Citation1980). This is because favorable responses from others are dependent on being dominant such that self-esteem is connected to social approval. Nonetheless, the sociometer theory is among the few theories that explain why self-esteem is strongly influenced by how people perceive they are evaluated by others. Thus, this theory argues that self-esteem is a gauge for monitoring the relationship quality with others. The fear of ostracism leads people to develop a psychological tool of “sociometer” to assess how they are being accepted in a social environment (Leary, Citation1999). Decrop et al. (Citation2018) found that friendship and trust forming during travel can benefit couchsurfing travelers’ psychological structures and help them overcome difficulties. Verkuyten (Citation2003) divided global self-esteem into positive and negative self-esteem and reveal that ethnic identification and family integrity were positively related to positive self-esteem while peer discrimination could hinder positive self-esteem and increase negative self-esteem. Hence, this study proposes two main hypotheses:

H9: Perceived social relations have a negative impact on negative self-esteem.

H10: Perceived social relations have a positive impact on positive self-esteem.

Besides self-esteem’s association with perceived social relations, cultural worldview as a broader and macro concept could impact individual self-evaluations (Goldenberg et al., Citation2001; Solomon et al., Citation1991). From a terror management theoretical perspective, cultural worldviews serve as a framework that allows humans to lead an enduring existence as a valued individual through self-esteem which creates an anxiety-buffering system (Zaleskiewicz et al., Citation2015). In this way, cultural worldview provides a shared symbol that infuses the universe with meaning and permanence (Solomon et al., Citation1991). Consequently, a stronger cultural worldview is likely to propel positive self-esteem and reduce negative self-esteem. Based on TMT, this study thus posits that:

H11: Cultural worldview has a negative impact on negative self-esteem.

H12: Cultural worldview has a positive impact on positive self-esteem.

Additionally, both positive and negative self-esteem are key explanatory variables for prosocial behaviors (Zuffianò et al. (Citation2014). If according to TMT, a sense of meaning is derived from self-esteem, then those with positive esteem may want to enhance such attributes by engaging in those behaviors that reaffirm such attributes (Zaleskiewicz et al., Citation2015). Zuffianò et al. (Citation2014) highlight the positive correlation between prosociality and self-esteem and argue that self-esteem provides motivational resources that lead individuals to help others. Meanwhile, those with negative self-esteem may refute such evaluations by engaging in positive behaviors to enhance their image (Tung, Citation2019). Prosocial studies among residents support this argument that acting prosocial is used to refute negative meta-stereotypes and to obtain positive evaluations from tourists (Tung, Citation2019). Hence, self-esteem will impact prosocial behaviors (). We, thus, hypothesize that:

H13: Positive self-esteem has a positive impact on prosocial behaviors.

H14: Negative self-esteem has a positive impact on prosocial behavior.

Materials and methods

Setting and target population

This study was set in Macau, a gaming giant in Asia and a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China. As a popular destination in Asia, Macau is known not only for its attractive gaming industry but also for its rich cultural and heritage attractions drawing many tourists from mainland China and beyond (Statistics and Census Service, Citation2021a).

Tourists visit Macau for a myriad of purposes including cultural heritage, leisure, shopping, gaming, backpacking, and volunteering (Chen et al., Citation2020; Luo & Ye, Citation2020; Ong & Du Cros, Citation2012). Among all these types of visits, the benefit of acting prosocial is important regardless of the type of tourists since tourist-community conflict could be reduced through prosocial behaviors. Given the basic understanding that the sustainable development agenda is a global goal that requires global action (Lockstone-Binney & Ong, Citation2022), all tourists regardless of their visit purpose/type have a significant role to play in the social sustainability of tourism destinations. Hence, understanding ways to promote prosocial behaviors among all tourists is critical for destination managers to promote harmonious tourist-to-tourists encounters that may extend to the wider community (Agyeiwaah & Bangwayo-Skeete, Citation2022). Against this background, this paper targeted all visitors to Macau to understand the complex relationships between cultural worldviews, social relations, prosocial behaviors, and self-esteem. This was achieved through employing a quantitative approach that allows a survey of the target respondents using data collection tools such as a questionnaire.

Measures and data collection

To reach visitors in Macau and to address our study objectives, a multi-measurement questionnaire was employed to assess the four main constructs of this study. The design of the questionnaire comprised six sections including the five main constructs with self-esteem divided into two aspects, positive and negative, and a final sixth section of demographics. The prosocial questions were made up of six questions from literature and studies on prosocial behaviors. Questions include “I help immediately those who are in need during my local trip” (Luengo Kanacri et al., Citation2021). The second section was devoted to cultural worldviews where respondents were asked questions such as “Culture helps me to identify myself”. A total of four questions for existing cultural worldview studies were employed (Choi & Fielding, Citation2016). The perceived social relations were also captured following existing literature with questions such as “Even when someone seems unapproachable”, “I know I can find a way to break the ice when I travel” (Ciarrochi & Bilich, Citation2006; Lopez et al., Citation2000). A total of seven questions measured this factor. This was followed by the self-esteem construct which was divided into both positive and negative aspects based on the literature (see Ciarrochi & Bilich, Citation2006; Franck et al., Citation2008). The final demographic questions included age, gender, and education. All five constructs were measured by a 7-Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Following a pre-testing and translation of the instruments with further content validity and face validity checks, data collection proceeded from November to December 2021 with bilingual instruments in both Chinese and English versions.

Specifically, before the data collection, student enumerators studying tourism and hospitality were recruited and trained on the questionnaire data collection. During the training, the purpose and targeted respondents were explained. For example, in this study, we targeted domestic and international tourists at the time. Being a tourist is used here, theoretically, to mean three aspects (1) a voluntary choice, (2) a temporary activity, and (3) mobility away from home (Coles et al., Citation2012; Mor et al., Citation2023, p. 2). While international tourists involve those tourists crossing national borders (Reisinger, Citation2009) and in this study, Chinese Mainlanders crossing national border gates to Macau, domestic tourists are conceptualized based on Jafari (Citation1986)’s definition as tourists traveling within their home region and supporting industry systems that cater to them.

The data collection employed a convenience sampling method which involves selecting a sample that is available and convenient to the research team (Baxter et al., Citation2015; Galloway, Citation2005). Based on this approach, enumerators targeted tourists both domestic and international available in the 2021 period in Macau. During 2021, COVID-19 restrictions required Chinese Mainland tourists to enter Macau with a Negative Nucleic Acid test. Meanwhile, the Macau government rolled out local tours in 2021 such as “Stay, Dine and See Macao” initiated between April and December 2021 to allow residents to sign up with travel agencies and enjoy subsidies for local tours in Macau leading to the dominance of domestic tourists (Government Information Bureau of the Macao SAR, Citation2022). This study, thus, targeted visitors who self-identified as such at various tourist attractions including those rolled out in the community tours. Thus, enumerators identified visitors to various tourist attractions such as Macau Tower, Senado Square, the Ruins of Saint Paul’s, the Seac Pai Van Park, Macao Grand Prix Museum and Handover Gifts Museum of Macao, and Nossa Senhora Village of Ká Hó where the data collection took place. In the end, a total of 403 questionnaires were completed and they were useful for analysis.

Data analysis

This study adopted a four-step approach to analyzing the data. The first approach involves conducting an exploratory factor analysis to ensure that each of the examined constructs is represented under relevant constructs (Pallant, Citation2005). The lack of a priori (confirmed) measures of the proposed model made this a necessary step requiring rotation of the items generated through EFA. This stage also allowed examining common method bias using the factor loading approach suggested in the literature. Hence, this study followed suggestions by Harman’s single-factor (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) approach to demonstrate that the variance explained by the first (major) factor was 27.6%—less than the 50% cut-off point.

In addition, the study examined the internal consistency of measurement items (α range =0.700–0894) using Cronbach’s alpha (Ursachi et al., Citation2015) with further inspection of data normality (). Based on Brown (Citation2015)’s suggestions to examine data normality based on skewness (-3 to +3) and kurtosis (- 10 to +10) in structural modeling, we examine and present the normality values in to confirm that the data is symmetrically distributed.

Table 1. EFA and CFA on measurement indicators.

In the second stage, the measurement model (Confirmatory Factor Analysis [CFA]) was examined with various fit indices examined using the AMOS 22 software. This stage involved conducting various validity and reliability analyses (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The third stage involved testing the proposed baseline model and competing model using covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Following the competing model strategy (Hair et al., Citation2010), we employ both Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Browne-Cudeck criterion (BCC) in addition to other goodness of fit indices to analyze both models and to decide the better model (Huh et al., Citation2009; Vrieze, Citation2012). The fourth stage involved employing PROCESS Macro to examine the moderated-mediated relationship in the proposed model.

The demographic analysis shows over dominance of domestic tourists (43.9%) reflective of COVID-19 restrictions at that time that made travel a difficult task and convenient for locals to visit their local environments. Statistics from the Statistics and Census Service (Citation2021b) show that in the 3rd and 4th Quarters of 2021, domestic tour visitors increased to 7,025 and 5,584 visitors respectively due to the increased community tours during this period. The dominant age range recorded in 2021, 30 December was the 25–34 age (8,408) range which occupies the second-highest age in this study (Statistics and Census Service, Citation2021b). Empirical studies in China confirmed that during the pandemic, more youth traveled compared to older people who were more susceptible to the COVID-19 virus (Yang et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021). While the dominance of youthful age reflects the impact of a pandemic that stimulated young people to travel within the city, it is acknowledged that this pattern may be different in the post-pandemic period. This dominance was followed by tourists from both mainland China (33.3%) and Hong Kong (14.9%) (see ). There was an overwhelming number of females (56%) compared to males (44%). Most tourists have attained a bachelor’s degree (41.4%) (see ).

Table 2. Profile of the respondents.

Results

EFA and the measurement model results

The first stage analysis with EFA revealed a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001; df = 351) with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy greater than the minimum requirement (KMO = 0.876) (Pallant, Citation2005). This stage was followed by a confirmatory factor analysis to assess the measurement model (). This stage involved inspecting various fit measures. The study results confirmed that the model fits the data well based on the goodness of fit indices (χ2 = 618.723; df = 299; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 2.069; GFI = 0.896; CFI = 0.931; IFI = 0.932; RMSEA = 0.052; PCLOSE = 0.319). Following suggestions to concurrently ensure that the measurement items are reliable and valid, the study examined other discriminant validity and composite reliability indices in . Except for positive self-esteem whose composite reliability value was close to 0.7 (i.e. 0.685), the rest of the factors have reliability values greater than 0.7. Further inspection of both composite reliability and average variance following literature suggestions (e.g. Prayag et al., Citation2018) revealed that all AVE values met the minimum cut-off criteria of greater than or equal to 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2009b) except the two self-esteem variables and cultural worldviews. To ensure the robustness of these constructs, the study adhered to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981)’s decision rule to decide whether to keep an item or remove an item. According to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), when AVE values are lesser than 0.5 but composite reliability is higher than 0.6, this value makes it adequate for convergent validity to be established ().

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

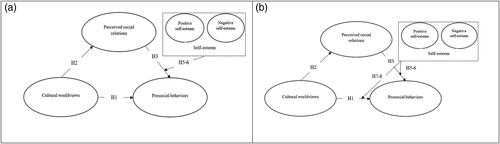

A structural model with direct and indirect effects for the baseline model

As part of testing two proposed conceptual models ( and ), a structural model was employed to evaluate the fit indices of the proposed hypotheses (). For the baseline conceptual model (a & b), the model fit indices show a good fit (χ2 = 244.943; df = 105; χ2/df = 2.33; GFI = 0.933; CFI = 0.958; IFI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.058; PCLOSE = 0.090). Based on recommendations by Hair et al. (Citation2009a), these indices were acceptable (Megeirhi et al., Citation2020). Three direct relationships were found to be significant (H1-H3). For example, cultural worldviews had a direct positive impact on prosocial behaviors (H1: β = 0.193; p = 0.003) and perceived social relations (H2: β = 0.335; p < 0.001). Moreover, perceived social relations have a positive relationship with prosocial behaviors (H3: β = 0.362; p < 0.001) ().

Table 4. Goodness-of-fit measures.

Table 5. Structural model results of direct effect and indirect effects.

An indirect analysis was conducted using the AMOS bootstrap method for the baseline model (). This was to investigate the indirect role of perceived social relations (H4). The results show a significant indirect relationship for H4. Further inspections following Nitzl et al. (Citation2016) to conclude whether the indirect relationship is partial or full examining both the direct and indirect bootstrap results revealed a partial mediation. It was found that both the indirect relationship and direct relationship were significant indicating a partial mediation (). Thus, the perceived social relationship is a partial mediator of the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors (H4). The next step was to examine the moderating role of self-esteem in this significant indirect relationship.

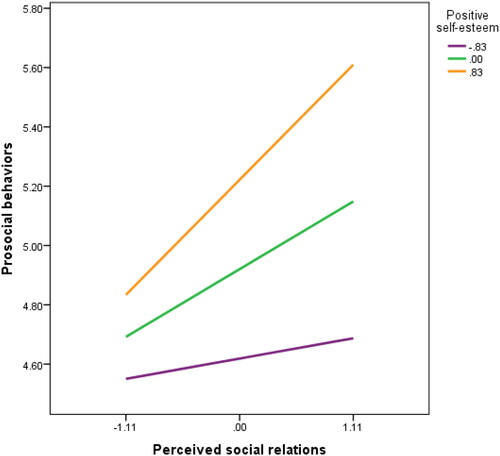

Moderated-mediated relationships with self-esteem for the baseline model

Two moderated mediated models were examined (). The first model involved the examination of hypotheses 5 and 6 conditional indirect effects of positive and negative self-esteem on the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behavior using the PROCESS Model 14 (). The results of this investigation revealed that H5 was significant but hypothesis 6 was not significant. Specifically, positive self-esteem (β = 0.173; p = 0.001; 95% CI = [0.068, 0.277]) had a significant moderated mediation effect as zero was not included in the 95% confidence intervals (CI). This means that the higher the positive self-esteem, the stronger the indirect relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors (). However, there was no significant moderated mediation effect of negative self-esteem as zero was included in the 95% confidence interval (β = 0.007; p = 0.844; 95% CI = [-0.059, 0.072]). A further examination of the graphed results in shows that the line graphs of the relationship between perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors become increasingly positive as positive self-esteem increases. Hence, the relationship between perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors is conditioned by different levels of positive self-esteem.

Table 6. Results of the moderated-mediating effect of self-esteem.

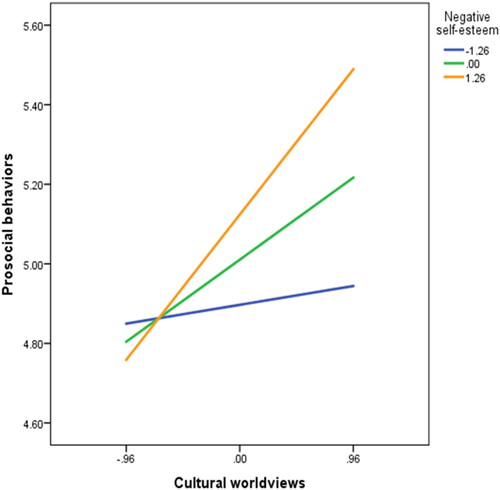

The second model () examined hypotheses 7 and 8 to reveal the conditional relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behavior using the PROCESS Model 15 (). Contrary to the first baseline model, positive self-esteem had no significant impact whereas negative self-esteem was found to possess a significant impact on the conditional relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors confirming H8 (β = 0.131; p = 0.002; 95% CI = [0.050, 0.213]). shows that the line graphs of the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors become increasingly positive as negative self-esteem increases.

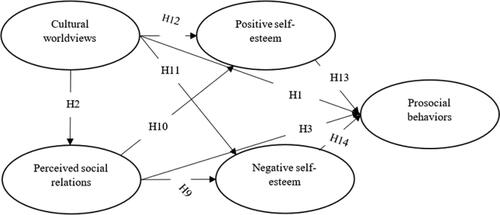

A structural model for the competing model

, which represents the competing model examined the direct effects among all the variables in the study. Specifically, it tested hypotheses 9–14 in addition to other direct relationships in the baseline model (). The structural model using AMOS 22 software confirmed that five out of the six proposed relationships were significant except for H9 which was contradictory. For example, perceived social relations had a positive impact on both negative self-esteem (H9: β = 0.105; p = 0.008) and positive self-esteem (H10: β = 0.460; p < 0.001). Cultural worldviews had a negative relationship with negative self-esteem (H11: β = −0.193; p = 0.008) but a positive relationship with positive self-esteem (H12: β = 0.341; p < 0.001). Both positive (H13: β = 0.313; p < 0.001) and negative self-esteem (H14: β = 0.219; p < 0.001) positively impacted prosocial behaviors implying that both people with positive and negative self-esteem engage in prosocial behaviors. Despite the confirmation of all proposed extra six hypotheses, a critical look at the goodness of fit indices in shows that the baseline model has a lower Akaike Information Criterion (AIC =340.943baseline model; 797.517competing model) and Browne-Cudeck criterion (BCC = 345.443basline model; 809.646competing model) compared to the competing model suggesting the baseline model has a better fit.

Discussion and conclusion

While recent studies continue to position prosocial behaviors as desirable actions that contribute to well-being (Han et al., Citation2020; Kim & Michael Hall, Citation2022), many of these studies overlook the cultural, social, and individual psychological factors that contribute to varying prosocial actions (Chi et al., Citation2022; Han et al., Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2023). Building on previous prosocial behavioral research in tourism (Chi et al., Citation2022; Tung, Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2022), this study examined the relationships between cultural worldviews, perceived social relations, and prosocial behaviors with further investigation of the moderating role of self-esteem on the indirect relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial behaviors. An alternative theoretical explanation is also analyzed through a competing structural modeling approach. Based on this approach, this research identified significant relationships between cultural (cultural worldviews), social (perceived social relations), psychological (self-esteem), and behavioral factors (prosocial behaviors). This study, thus, contributes to explaining the overlooked relationships between cultural worldviews, perceived social relations, self-esteem, and prosocial behaviors in the tourism context. Eleven (11) out of the fourteen (14) proposed relationships were found to be significant expanding many of the theoretical explanations of the relationships between prosocial and other cultural and socio-psychological factors. The findings of the proposed relationships present theoretical, methodological, and practical contributions to the sustainable management and marketing of tourist behaviors.

Theoretical implications

This study highlights three theoretical contributions to prosocial research and social sustainability research in general. First, it explains how cultural worldviews impact perceived social relations and prosocial behavior. As humanly designed symbolic perceptual constructions that are shared by groups of people (Solomon et al., Citation1991), cultural worldviews’ influential power becomes evident in individual social behaviors. Tourists with high cultural worldviews were more likely to act prosocial (H1) and perceive highly of their social relations during the trip (H2). These findings, theoretically, suggest that whether tourists would seek meaningful travel relationships and engage in socially meaningful behaviors, is dependent on the broader cultural worldviews. Hence, cultural worldviews act as the driving macro explanation of socially desirable behaviors (Cherry et al., Citation2019). When relationship building and social harmony are core aspects of cultural worldviews (in this case collectivist culture), then any action or travel activity that contributes to such worldviews is valorized. Thus, people act prosocial and build meaningful relationships in tourism because it aligns with their cultural worldviews. This affirms the TMT argument that cultural worldviews are a key driver of prosocial behaviors (Zaleskiewicz et al., Citation2015) and further extends the explanation for the question—why do people act prosocial in a tourism context?

Second, this study explains how prosocial behavior, an outcome, relates to both perceived social relations and cultural worldviews. Most of the research in heritage tourism and sustainable tourism practices examine how residents’ intentions to support cultural heritage tourism (Megeirhi et al., Citation2020), the tourist decision making process of visiting heritage sites (Lee et al., Citation2020), and food waste practices (Long et al., Citation2022) could be understood through cultural worldviews. While these studies found that cultural worldviews positively impact residents’ and tourists’ attitudes in the cultural heritage tourism context, they do not examine cultural worldviews in relation to prosocial behaviors - a gap we seek to fill. Our novel findings indicate a significant relationship between cultural worldviews, prosocial behaviors, and perceived social relations which is unknown from previous research. It, theoretically, suggests that tourists’ prosocial behaviors are rooted in their culture and the quest for meaningful relationships. Such insights extend the discourse on the connection between cultural and social sustainability in the tourism context.

Despite the increased scholarly works on tourist prosocial behaviors, one research question that remains unanswered is how perceived social relations impact prosocial behaviors among tourists (H3). Within the research on the resident-prosocial nexus, attention has been devoted to meta-stereotypes and prosocial behaviors (Tung, Citation2019) other than the underlying reasons for the search for social relations during travel. Employing both the Face-Negotiation Theory and the theory of reciprocal altruism in the context of prosocial behaviors, we found a positive relationship between perceived social relationships and prosocial behaviors. We, further, contribute two plausible social reasons for being prosocial. First, prosocial is an outcome of not just cultural worldviews, but the quest to build a meaningful social relationship. Given the high-context Chinese cultural context where this study took place, emphasis is placed on others with a high willingness to establish a good social relationship in a group to possess a mutual face. Second, friendships are also created with reciprocity in mind (Brosnan & de Waal, Citation2002). This study also contributes, theoretically, to the understanding that perceived social relations, in part, explain how cultural worldviews impact prosocial behaviors (H4). Thus, the process of worldviews impacting prosocial behaviors may not always be a direct one but indirect since visitor behavior may reflect the importance of their perceived social relations.

Third, the results of this study contribute to psychological reasons that underpin prosocial behaviors. Two moderated mediation models (H5-8) provide empirical support in this direction. In the first moderated mediation model, whether the quest for meaningful friendship during travel would lead to prosocial depends on how such a relationship creates a sense of worth to the visitor. Consequently, in a travel context where individuals have high self-esteem, relationship building through friendship creates a sense of worth and people become more inclined to act more prosocial (H5). However, in the context of negative self-esteem, the impact of building friendly relationships on prosocial behaviors becomes insignificant because people with negative self-esteem think people will not accept them (H6). These results extend the sociometer theory (Leary & Baumeister, Citation2000) by highlighting how self-esteem is used to evaluate the importance of relationship-building in tourism. This implies that tourists with positive self-esteem find other tourists more accepting and will evaluate relationships built through voluntary choice as more important making them more prosocial.

In the second moderated mediation model, the strength of the relationship between cultural worldviews and prosocial depends on negative self-esteem (H8) and not positive self-esteem (H7) contrary to the first model. TMT offers a deeper explanation of why this result is so. TMT argues that the reason why cultural worldviews are created is to enhance self-preservation and counteract negative thoughts such as those from death and demeaning self-evaluations (Zaleskiewicz et al., Citation2015). Consequently, cultural worldviews’ ability to influence prosocial depends on whether such thoughts are in existence making prosocial worth engaging in Solomon et al. (Citation1991). Given this understanding, when one possesses positive thoughts and self-worth (H7) which do not undermine self-preservation, the significance of cultural worldviews tends to reduce since individuals do not feel threatened to possess the urgency to refute such threats (Tung, Citation2019). This implies that, in a travel context where self-esteem is threatened, tourists’ cultural worldviews have a greater propensity to engender prosocial actions.

Methodological implications

First, this study provides methodological contributions by offering alternative theoretical explanations (H9-14). With the inclusion of mediators and moderators with further tests of the various direct relationships that may exist among all the variables, we offer comprehensive insights into the complex proposed relationships. This study, thus, contributes to a fuller real-world picture for understanding the relationship among cultural worldviews, perceived social relations, self-esteem, and prosocial behaviors using moderated mediation analysis and direct relationship analyses.

Second, through such a methodological approach, the theoretical understanding is further extended. For example, the competing model () contributes to the understanding that cultural worldviews help combat negative self-esteem by reducing its destructive impacts (H11). Alternatively, cultural worldviews enhance positive self-esteem during travel (H12). Contrary to our hypothesis, perceived social relations increased both negative (H9) and positive esteem (H10) perceptions concurrently. This contradictory insight could mean that the nature of social relations during the tour may have both positive and negative impacts on self-worth particularly if tourists seeking friendship are rejected. Both positive (H13) and negative self-esteem (H14) evaluations could also influence prosocial actions. One seeks to reaffirm positive self-worth through prosocial, whereas the other seeks to refute negative self-worth through prosocial (Tung, Citation2019).

Methodologically, the relationship of the above variables is complex such that questions such as—Why do tourists act prosocial? Do cultural worldviews impact perceived social relations and prosocial behaviors; and What is the role of self-esteem? require multiple analytical approaches.

Practical implications

From a practical perspective, the comprehensive model of prosocial behavioral antecedents implies tourism managers seeking to encourage prosocial behaviors among tourists must recognize the cultural background, social perceptions, and self-esteem evaluations. Hence, educational campaigns targeting prosocial behaviors should be aimed at highlighting the connection between culture and prosocial behaviors. For example, management terms such as “your own culture”, and “your relationship with others” could be centered on various educational platforms. Managers should also create a link between travel and self-esteem by demonstrating how each visit contributes to the positive self-esteem of the traveler. For example, managers can state in their promotional campaigns that “by visiting our attraction, it means you possess good qualities such as “altruism”, “kindness”, and “empathy”. By embedding these positive attributes in the visits, positive self-esteem could be increased thereby increasing prosocial behaviors with locals and other tourists during the trip—a significant ingredient to sociocultural sustainability.

Limitations, and future research

Some caveats of this research provide several opportunities for future research. First, this study involved visitors both domestic and cross-border tourists, and hence the sample size is limited to only a few tourists within mainland China who could travel to this Special Administrative Region. While this sample may be slightly different from the pre-and post-COVID-19 period, it reflects the changes in the city at the time of data collection and confirms the positive impacts of government local tour initiatives on domestic tourism in the city. Second, to make survey administration easier onsite, our prosocial items were limited, and future studies could include more items covering empathy, volunteering, and helping behaviors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agyeiwaah, E., & Bangwayo-Skeete, P. (2022). Backpacker-community conflict: The nexus between perceived skills development and sustainable behavior. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(8), 1992–2012. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1995396

- Barkow, J. (1980). Prestige and self-esteem: A biosocial interpretation. In D.R. Omark, F.F. Strayer, & D.G. Freedman (Eds.), Dominance relations: An ethological view of human conflict and social interaction (pp. 319–332). Garland STPM Press.

- Baxter, K., Courage, C., & Caine, K. (2015). Chapter 5 - choosing a user experience research activity. In K. Baxter, C. Courage, & K. Caine (Eds.), Understanding your Users (pp. 96–112, 2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann.

- Bednar, R. L., & Peterson, S. R. (1995). Self-esteem: Paradoxes and innovations in clinical theory and practice (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10174-000

- Birkelund, J., Cherry, T. L., & McEvoy, D. M. (2022). A culture of cheating: The role of worldviews in preferences for honesty. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 96, 101812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2021.101812

- Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2002). A proximate perspective on reciprocal altruism. Human Nature (Hawthorne, N.Y.), 13(1), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-002-1017-2

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications.

- Cast, A. D., & Burke, P. J. (2002). A Theory of Self-Esteem. Social Forces, 80(3), 1041–1068. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2002.0003

- Chen, Z., Suntikul, W., & King, B. (2020). Constructing an intangible cultural heritage experiencescape: The case of the Feast of the Drunken Dragon (Macau). Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100659

- Cherry, T. L., McEvoy, D. M., & Westskog, H. (2019). Cultural worldviews, institutional rules and the willingness to participate in green energy programs. Resource and Energy Economics, 56, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2017.10.001

- Chi, X., Han, H., & Kim, S. (2022). Protecting yourself and others: Festival tourists’ pro-social intentions for wearing a mask, maintaining social distancing, and practicing sanitary/hygiene actions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(8), 1915–1936. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1966017

- Choi, A. S., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Cultural attitudes as WTP determinants: A revised cultural worldview scale. Sustainability, 8(6), 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8060570

- Ciarrochi, J., & Bilich, L. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package. University of Wollongong. Unpublished manuscript.

- Coghlan, A. (2015). Prosocial behaviour in volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 55, 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.08.002

- Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. The American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

- Coles, T., Duval, D. T., & Hall, C. M. (2012). Tourism, mobility, and global communities: New approaches to theorising tourism and tourist spaces. In Global tourism. (pp. 476–494): Routledge.

- Davis, A. N., McGinley, M., Carlo, G., Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Rosiers, S. E. D., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., & Soto, D. (2021). Examining discrimination and familism values as longitudinal predictors of prosocial behaviors among recent immigrant adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 45(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/01650254211005561

- Decrop, A., Del Chiappa, G., Mallargé, J., & Zidda, P. (2018). “Couchsurfing has made me a better person and the world a better place”: The transformative power of collaborative tourism experiences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1307159

- Esfandiar, K., Dowling, R., Pearce, J., & Goh, E. (2020). Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(1), 10–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1663203

- Fan, D. X. F. (2023). Understanding the tourist-resident relationship through social contact: Progressing the development of social contact in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 406–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1852409

- Fennell, D. A. (2006). Evolution in tourism: The theory of reciprocal altruism and tourist–host interactions. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(2), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500608668241

- Forgas, J. P. (1988). Episode representations in intercultural communication. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 186–212). Sage.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Franck, E., De Raedt, R., Barbez, C., & Rosseel, Y. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Dutch Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Psychologica Belgica, 48(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-48-1-25

- Fu, X., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Brown, M. N. (2017). Longitudinal relations between adolescents’ self-esteem and prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends and family. Journal of Adolescence, 57(1), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.04.002

- Galloway, A. (2005). Non-probability sampling. In K. Kempf-Leonard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Social Measurement (pp. 859–864). Elsevier.

- Ghaderi, Z., Esfehani, M. H., Fennell, D., & Shahabi, E. (2023). Community participation towards conservation of Touran National Park (TNP): An application of reciprocal altruism theory. Journal of Ecotourism, 22(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2021.1991934

- Goldenberg, J. L., Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Kluck, B., & Cornwell, R. (2001). I am not an animal: Mortality salience, disgust, and the denial of human creatureliness. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 130(3), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.427

- Government Information Bureau of the Macao SAR. (2022). “Stay, Dine and See Macao” project opens for application tomorrow Macao residents enjoy subsidy for local tour and hotel staycation. https://www.gcs.gov.mo/detail/en/N21DNVCVVx;jsessionid=AE7B8FFE97B3EFD29051686EDD6E2677.app01

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2009a). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009b). Análise multivariada de dados. Bookman Editora.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Han, H. (2015). Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management, 47, 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.014

- Han, H., Meng, B., Chua, B.-L., & Ryu, H. B. (2020). Hedonic and utilitarian performances as determinants of mental health and pro-social behaviors among volunteer tourists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186594

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Huh, H. J., Kim, T. T., & Law, R. (2009). A comparison of competing theoretical models for understanding acceptance behavior of information systems in upscale hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 121–134.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.004

- Jafari, J. (1986). On domestic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(3), 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(86)90033-2

- Jami, A., Kouchaki, M., Gino, F., Johar, G. V., Campbell, M. C., & Lamberton, C. (2021). I Own, So I Help Out: How Psychological Ownership Increases Prosocial Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 47(5), 698–715. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa040

- Jiang, H., Chen, G., & Wang, T. (2017). Relationship between belief in a just world and Internet altruistic behavior in a sample of Chinese undergraduates: Multiple mediating roles of gratitude and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.005

- Kheibari, A., & Cerel, J. (2021). Does self-esteem inflation mitigate mortality salience effects on suicide attitudes? Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(4), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12759

- Kim, M. J., & Michael Hall, C. (2022). Does active transport create a win-win situation for environmental and human health? The moderating effect of leisure and tourism activity. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.08.007

- Kuo, C.-M., Chen, L.-H., & Liu, C.-H. (2019). Is it all about religious faith? Exploring the value of contemporary pilgrimage among senior travelers. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(5), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1572632

- Leary, M. R. (1999). Making sense of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00008

- Leary, M. R. (1999). The social and psychological importance of self-esteem. In R.M. Kowalski & M.R. Leary (Eds.), The social psychology of emotional and behavioral problems: Interfaces of social and clinical psychology (pp. 197–221). American Psychological Association.

- Leary, M. R. (2005). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 75–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280540000007

- Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (vol. 32, pp. 1–62). Academic Press.

- Lee, C.-K., Ahmad, M. S., Petrick, J. F., Park, Y.-N., Park, E., & Kang, C.-W. (2020). The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100500

- Lin, H., Gao, J., & Tian, J. (2022). Impact of tourist-to-tourist interaction on responsible tourist behaviour: Evidence from China. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 24, 100709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2022.100709

- Lockstone-Binney, L., & Ong, F. (2022). The sustainable development goals: The contribution of tourism volunteering. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(12), 2895–2911. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1919686

- Long, F., Ooi, C. S., Gui, T., & Ngah, A. H. (2022). Examining young Chinese consumers’ engagement in restaurant food waste mitigation from the perspective of cultural values and information publicity. Appetite, 175, 106021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106021

- Lopez, S. J., Ciarlelli, R., Coffman, L., Stone, M., & Wyatt, L. (2000). Chapter 4 - diagnosing for strengths: On measuring hope building blocks. In C. R. Snyder (Ed.), Handbook of hope (pp. 57–85). Academic Press.

- Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Eisenberg, N., Tramontano, C., Zuffiano, A., Caprara, M. G., Regner, E., Zhu, L., Pastorelli, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2021). Measuring prosocial behaviors: Psychometric properties and cross-national validation of the prosociality scale in five countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 693174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.693174

- Luo, J. M., & Ye, B. H. (2020). Role of generativity on tourists’ experience expectation, motivation and visit intention in museums. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.03.002

- Ma, C., Mastrotheodoros, S., & Lan, X. (2022). Linking classmate autonomy support with prosocial behavior in Chinese left-behind adolescents: The moderating role of self-esteem and grit. Personality and Individual Differences, 195, 111679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111679

- Marigold, D. C., Holmes, J. G., & Ross, M. (2007). More than words: Reframing compliments from romantic partners fosters security in low self-esteem individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.232

- Martí-Vilar, M., Serrano-Pastor, L., & Sala, F. G. (2019). Emotional, cultural and cognitive variables of prosocial behaviour. Current Psychology, 38(4), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0168-9

- Megeirhi, H. A., Woosnam, K. M., Ribeiro, M. A., Ramkissoon, H., & Denley, T. J. (2020). Employing a value-belief-norm framework to gauge Carthage residents’ intentions to support sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1351–1370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1738444

- Meng, B., Chua, B.-L., Ryu, H. B., & Han, H. (2020). Volunteer tourism (VT) traveler behavior: Merging norm activation model and theory of planned behavior. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 1947–1969. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1778010

- Mor, M., Dalyot, S., & Ram, Y. (2023). Who is a tourist? Classifying international urban tourists using machine learning. Tourism Management, 95, 104689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104689

- Nathan, S., Kemp, L., Bunde-Birouste, A., MacKenzie, J., Evers, C., & Shwe, T. A. (2013). We wouldn’t of made friends if we didn’t come to Football United": The impacts of a football program on young people’s peer, prosocial and cross-cultural relationships. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 399. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-399

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- Ong, C.-E., & Du Cros, H. (2012). The post-mao gazes: Chinese backpackers in Macau. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.08.004

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. The American Psychologist, 77(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000922

- Pallant, J. (2005). SPSS survıval manual: A step by step guıde to data analysis using spss for wındows. Australia:Allen & Unwin.

- Paraskevaidis, P., & Andriotis, K. (2017). Altruism in tourism: Social exchange theory vs altruistic surplus phenomenon in host volunteering. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.11.002

- Pfattheicher, S., Nielsen, Y. A., & Thielmann, I. (2022). Prosocial behavior and altruism: A review of concepts and definitions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Prayag, G., Suntikul, W., & Agyeiwaah, E. (2018). Domestic tourists to Elmina Castle, Ghana: Motivation, tourism impacts, place attachment, and satisfaction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(12), 2053–2070. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1529769

- Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435

- Reisinger, Y. (2009). International tourism: Cultures and behavior. Elsevier.

- Reisinger, Y., & Crotts, J. C. (2010). Applying Hofstede’s national culture measures in tourism research: Illuminating issues of divergence and convergence. Journal of Travel Research, 49(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509336473

- Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., & Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global Self-Esteem and Specific Self-Esteem: Different Concepts, Different Outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096350

- Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (1991). A terror management theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of self-esteem and cultural worldviews. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 93–159.

- Statistics and Census Service. (2021a). Tourism statistics: 1st quarter 2021. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Statistic?id=401

- Statistics and Census Service. (2021b). Visitor statistics database. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/TourismDBWeb/#!/information/0?lang=mo#/main%3Flang=en

- Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Intercultural conflict styles: A face-negotiation theory. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 213–238). Sage.

- Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/406755

- Tung, V. W. S. (2019). Helping a lost tourist: The effects of metastereotypes on resident prosocial behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518778150

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00123-9

- Verkuyten, M. (2003). Positive and negative self-esteem among ethnic minority early adolescents: Social and cultural sources and threats. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023032910627

- Vrieze, S. I. (2012). Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychological Methods, 17(2), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027127

- Wang, C., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Social face consciousness and help-seeking behavior in new employees: Perceived social support and social anxiety as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality, 49(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10769

- Wang, X., Zhao, F., & Lei, L. (2021). Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction: Self-esteem and marital status as moderators. Current Psychology, 40(7), 3365–3375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00275-0

- Wei, C., Dai, S., Xu, H., & Wang, H. (2020). Cultural worldview and cultural experience in natural tourism sites. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.04.011

- Wentzel, K. R., & McNamara, C. C. (1999). Interpersonal relationships, emotional distress, and prosocial behavior in middle school. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431699019001006

- Wu, J., Guo, Y., Wu, M.-Y., Morrison, A. M., & Ye, S. (2023). Green or red faces? Tourist strategies when encountering irresponsible environmental behavior. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 21(4), 406–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2022.2106789

- Xu, Y. (2019). Role of social relationship in predicting health in China. Social Indicators Research, 141(2), 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1822-y

- Xue, W., Hine, D. W., Marks, A. D. G., Phillips, W. J., & Zhao, S. (2016). Cultural worldviews and climate change: A view from China. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 19(2), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12116

- Yang, Y., Cao, M., Cheng, L., Zhai, K., Zhao, X., & De Vos, J. (2021). Exploring the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in travel behaviour: A qualitative study. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, 100450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100450

- Zaleskiewicz, T., Gasiorowska, A., & Kesebir, P. (2015). The Scrooge effect revisited: Mortality salience increases the satisfaction derived from prosocial behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 59, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.03.005

- Zhang, L., Yang, H., Wang, K., Bian, L., & Zhang, X. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on airline passenger travel behavior: An exploratory analysis on the Chinese aviation market. Journal of Air Transport Management, 95, 102084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102084

- Zhu, P., Chi, X., Ryu, H. B., Ariza-Montes, A., & Han, H. (2022). Traveler pro-social behaviors at heritage tourism sites. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 901530. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.901530

- Zuffianò, A., Alessandri, G., Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Pastorelli, C., Milioni, M., Ceravolo, R., Caprara, M. G., & Caprara, G. V. (2014). The relation between prosociality and self-esteem from middle-adolescence to young adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 63, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.041