Abstract

Recent studies on urban policy responses to increasing tourism have moved beyond the physical impact of tourism to also include the way tourism is framed by social movements. This paper contributes to this line of research with a focus on frame resonance: the extent to which frames strike a responsive chord with the public in general and policymakers in particular. We introduce a specific form of frame amplification through cultural resonance; the appeal to pre-existing societal beliefs. Using an analysis of policy documents, print, online and social media, we demonstrate that frames around tourist shops in Amsterdam appealed to pre-existing beliefs that portray the inner city as: a delicate mix of functions, an infrastructure for criminal activities, and a business card reflecting the city’s quality of place. These beliefs amplified frame resonance to such an extent that they convinced an initially reluctant local government to ban tourist shops from the inner city, a policy that undermines the accessibility and inclusivity of urban spaces that the local government aims to promote (SDG 11). This suggests that the contingencies in the local context that enable or foreclose the cultural resonance of frames are essential in understanding policy responses to touristification.

Introduction

About a decade ago it would have been hard to imagine a product with a more lovable image than Nutella. Yet when in recent years a growing number of pastry shops in Amsterdam started to display large jars of Nutella in their shop windows, local print and social media responses were rather hostile. The cocoa spread was often associated with war rhetoric about fights and battles. This happened against the backdrop of urban social movements raising awareness of the negative effects of tourism on the accessibility and inclusivity of urban spaces (Sustainable Development Goal 11) in cities around the world (Capocchi et al., Citation2019; Clancy, Citation2020; Dodds & Butler, Citation2020; Novy, Citation2019; Paredes-Rodriguez & Spierings, Citation2020; Romero-Padilla et al., Citation2019). In Amsterdam, tourist shops became controversial and particularly Nutella grew into a symbol of everything about tourism that local residents resent. The local government responded to this resistance with a legally challenging zoning plan that bans tourist shops from the inner city (City of Amsterdam, Citation2018), an unexpected policy turn considering that the same coalition had started its term with the intention to deregulate the retail sector (Paternotte et al., Citation2014). It illustrates the importance and urgency with which tourist shops emerged on the local political agenda, which this paper explains by the successful framing of touristification by social movements.

While increasing resistance to tourism has become a worldwide phenomenon, there are large differences in the specific effects of tourism that are problematized in different contexts, as well as in approaches urban governments take to mitigate these effects. Explanations for these differences have tended to focus on the physical impacts of tourism and the destination’s carrying capacity (Adie et al., Citation2020; Innerhofer et al., Citation2019). The popularization of the term overtourism illustrates this (Koens et al., Citation2018). It explains resistance to tourism as a response to a growing visitor flow, which overcharges local facilities, causes crowing, congestion and waiting times to access local businesses, damages heritage sites and results in increasing nuisance. This focus on visitor numbers presents a very limited perception of issues around tourism as emerging in response to objective circumstances and disappearing when these circumstances change. This is hardly ever true for social problems (Blumer, Citation1971), and seems unlikely to be the case in Amsterdam, where observable effects of tourism on consumption spaces are variegated (Hagemans et al., Citation2023). Instead, the key to why tourist shops became such a prominent issue in Amsterdam lies in the way they were framed.

Framing forms the interpretative layer between an occurrence or event and a social problem. It describes the way in which a topic is interpreted and discussed, which can have important implications for the extent to and the way in which it will be addressed (Schweinsberg et al., Citation2017). The interpretation will depend on the local context. In an average shopping mall, the replacement of a shoe shop by a pastry shop will probably be interpreted as a result of the increase in online shopping or of a shift in consumer demand. In a popular tourism destination, the same event can easily be framed as a token of touristification and used to problematize the change-over. Framing is therefore essential to explain how issues end up on the local policy agenda. Moreover, frames are introduced, promoted and adopted by different actors and social movements, both unconsciously and strategically (Cornelissen & Werner, Citation2014). This draws attention to the role of power in defining an issue and mobilizing support for a proposed solution, an awareness that is critical to the ambition to foster accessible and inclusive urban spaces (SDG 11). After all, social movements that resist tourism can both protect the accessibility and inclusivity of urban spaces or undermine it by othering and excluding other users of space, including tourists and the tourism sector.

Framing has gained increasing attention in studies on resistance to tourism (Aguilera et al., Citation2021; Milano et al., Citation2019; Paredes-Rodriguez & Spierings, Citation2020; Russo & Scarnato, Citation2018). However, these studies explain the success of frames foremostly by the clarity and coherence of the frame content, as well as the popularity and visibility of the organizations and spokespeople that support it. Especially Barcelona stands out as a case in which social movements have been successful in finding a collective message and popular spokesperson (Milano et al., Citation2019; Paredes-Rodriguez & Spierings, Citation2020). However, social movements that demonstrate such a high level of organization around a very specific issue seem to be the exception rather than the rule (Novy & Colomb, Citation2019; Russo & Scarnato, Citation2018). In Amsterdam, the social movements that specifically target tourist shops have either been temporary or played a very marginal role in the public debate, largely lacking a coherent message or recognizable spokesperson.

We therefore contribute a focus on the context in which the frame is produced and received, specifically on cultural resonance; the extent to which frames resonate with pre-existing beliefs (Buijs et al., Citation2011). Such resonance increases the credibility of frames and makes them seem more natural (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). Our analysis demonstrates how frames around tourist shops in Amsterdam became successful by making clever use of representations of the inner city that were already widely accepted among local residents and policymakers.

Resistance to touristification as a framing strategy

Touristification refers to the positive and negative ways in which tourism affects destinations by introducing new ways of using space, changing economic flows and power relations between local stakeholders and transforming the landscape (Ojeda & Kieffer, Citation2020). Over the past decade, negative perceptions of tourism have gained dominance, especially in heritage cities. Here, increasing numbers of visitors are argued to challenge sustainability of cities and communities (SDG 11), for instance by causing resident displacement on the housing market (Cocola-Gant & Gago, Citation2021; Postma & Schmuecker, Citation2017) as well as congestion and nuisance due to intrusive or inappropriate behavior (Smith et al., Citation2019). This perceived loss of place has caused increasing resistance from social movements (Milano et al., Citation2019; Paredes-Rodriguez & Spierings, Citation2020); networks of individuals, informal groups and organizations that unite over particular values, beliefs and interests, which drive them to undertake collective actions (Tilly, Citation1978). These actions respond to transformations or situations that somehow disrupt their daily life, values or rights (Castells, Citation1983).

A central objective of social movements is to put their issue on the political agenda (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). To achieve this, they mobilize support for a particular understanding of an issue (Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Goffman, Citation1974). This takes place in a collective and iterative process where different actors support complementary or conflicting frames (Cornelissen & Werner, Citation2014). Frames generally serve three purposes; to promote a specific interpretation of a phenomenon; to mobilize other actors to adopt their specific understanding; and to propose a particular course of action (Cornelissen & Werner, Citation2014). Put simply, these frames answer the respective questions: What is going on? Why should we do something about it? And what can be done about it? These elements are referred to as diagnostic, motivational and prognostic frames (Benford & Snow, Citation2000).

Diagnostic frames identify and interpret a problem, often using stylistic figures of speech, such as metaphors (Budd et al., Citation2019). This typically includes a narrative that identifies causes, effects, victims and culprits. In the beforementioned example of the pastry shop replacing a shoe shop, the interpretation that this is caused by increasing tourism and affects livability for local residents is a diagnostic frame. However, a problem definition in itself is not enough to put a problem on the political agenda. This also requires importance and urgency. These aspects are emphasized in motivational frames, the ‘call to arms’ (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). Motivational frames tend to emphasize how and why a problem will only get worse unless immediate action is undertaken. Furthermore, they often attempt to convince actors of their ability and responsibility to address the problem. In our example, motivational frames could portray the shop changeover as causing a domino effect on other businesses. Finally, prognostic frames propose the particular action that can be taken. Prognostic frames typically propose a solution, as well as a responsible party that should carry out this proposed course of action. The ban on tourist shops introduced in Amsterdam started as one of such proposed solutions. Together, diagnostic, motivational and prognostic frames can put a problem on the political agenda. Whether frames are successfully adopted on the political agenda, however, depends on resonance (Benford & Snow, Citation2000).

The role of social representations in increasing frame resonance

Resonance is a measure of frame success, describing the ease with which a frame is remembered, the extent to which it is shared and the effectiveness with which it mobilizes other actors to follow the proposed course of action (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). Frame resonance depends on several factors, including the physical setting in which a frame is presented (Hajer & Uitermark, Citation2008), the credibility of the frame articulators and the occurrence of notable events or developments that make a particular frame more tangible at a certain point in time. This variety of explanatory factors makes it notoriously difficult to explain why some frames are more successful than others (Buijs et al., Citation2011; Poletta & Ho, Citation2006). This is why the bulk of framing studies focuses on the content of frames, rather than on the context that enabled these frames to become influential (Phi, Citation2020).

From literature on environmental framing, we know that context and especially pre-existing beliefs about the affected context can play an important role in amplifying frame resonance (Buijs et al., Citation2011). Relating to these pre-existing beliefs creates cultural resonance, which makes frames seem more natural, familiar and credible (Gamson & Modigliani, Citation1989). These beliefs can be common sense understandings or folk knowledge that people use to interpret the world around them. Buijs et. al. (Citation2011) conceptualize these beliefs as social representations. Contrary to frames, social representations are not related to any specific issue; they do not define a problem or propose a solution (Buijs et al., Citation2011). Rather, they are ways in which people perceive and make sense of an ‘object’ such as nature (Buijs et al., Citation2011), or a place. In the case of tourist shops in Amsterdam, diagnostic and motivational frames claim, for instance, that increasing tourism causes a monotonous consumption landscape, which erodes the attractiveness of the inner city. These frames resonate with the belief that a mix of functions is one of the key elements that make the inner city of Amsterdam attractive. This belief predates frames about touristification of consumption spaces and in itself does not immediately call for action.

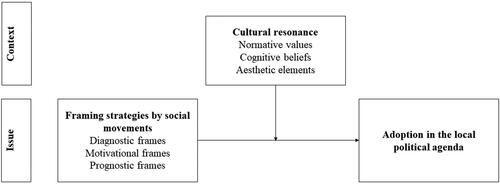

Beliefs consist of normative values, cognitive beliefs and aesthetic elements (Keulartz et al., Citation2004). Normative values relate to the moral status attributes to different stakeholders or even objects that underpin judgements of what is considered right or wrong for this specific context (Keulartz et al., Citation2004). This could entail judgments about what and who belongs or who should have the right to shape a place. Cognitive beliefs refer to the mechanisms that are assumed to affect a place or an object (Keulartz et al., Citation2004). This often includes a narrative about what elements are considered vulnerable and in need of protection. Finally, aesthetic elements refer to what we find beautiful or ugly, as well as the emotions and feelings of attachment that come with this judgment. displays the conceptual links between frames and cultural resonance. In the next section, we will present Amsterdam’s ban on tourist shops in more detail. After that, we will outline our methods and findings on frames and social representations in discussions around tourist shops in Amsterdam.

Amsterdam’s ban on tourist shops in a legal context

Amsterdam’s ban on tourist shops is legally challenging, because national spatial planning laws and European directives generally do not allow local governments to restrict the type of businesses that can locate in particular areas. However, particular circumstances allow exceptions to this rule. These are circumstances in which either sound spatial planning or a good living environment is at stake (Rijksoverheid, Citation2008). Zoning plans in Amsterdam have previously referred to this exception to exclude particular retail and hospitality sectors with the aim to “prevent anticipated or stagnate existing dilapidation of the residential and work circumstances and of the appearance of the designated area” (Rijksoverheid, Citation2008 art. 3.1.2). Souvenir shops, for instance, were already banned from the inner city since 2013. The most important difference between these existing restrictions and the ban on tourist shops is that tourist shops are not a generally accepted retail subsector, and they cannot easily be defined by their activities or even offer of products.

The ban on tourist shops solves this challenge by defining tourist shops with a combination of particular retail sectors, specific products and types of advertisement and presentation that are associated with tourist target audience (City of Amsterdam, Citation2018). Firstly, the sectors that are banned from the inner city are businesses that sell small quantities of soft drugs or paraphernalia for smoking or growing marihuana (grow shops, headshops, seed shops, and smart shops), souvenir shops, mini supermarkets, phone call shops, gambling halls, money exchange offices, massage parlors and take-out food shops (City of Amsterdam, Citation2018). Secondly, for shops that do not fall in these restricted categories, limitations are introduced around the offer of souvenirs and take-out food. To define souvenirs, the zoning plan argues that:

“One should not think only of dolls in (…) traditional dress, wooden windmills, key chains with cheeses, windmills, tulips, clogs and the like, but also of textiles (…), ceramics (…) and spoons with prints of national-, regional- or Amsterdam-related symbols. (…) [including] items that appeal to the city’s image of easy access to drugs and sex.” (City of Amsterdam, Citation2018 art 1.2.3)

Methods

Our analysis of frames around tourist shops and beliefs about Amsterdam’s inner city is based on a written texts from policy documents as well as print, online and social media content published before March 2020, when the Covid-19 lockdowns significantly altered discussions about both tourism and consumption spaces. As a reflection of the time in which they were produced, written texts are especially useful to research how frames have developed—something that would be difficult to reconstruct in hindsight with the use of interview data. Due to social media, these written texts are no longer always paraphrased and edited, but also include a growing share of unmediated content to triangulate the frames identified in policies and print media. This content can still be biased. Residents who feel very strongly about either positive or negative effects of tourism may be more likely to share their opinion on social media than those who take a more neutral position, for instance. This makes online, print and social media content about tourist shops in Amsterdam a poor representation of the population of residents. However, our sampling approach is not intended to generalize to a population, rather it is designed to represent as accurately as possible the content that compelled policymakers to intervene in touristification of consumption spaces. To achieve this, we sampled documents based on intertextuality.

Intertextuality acknowledges how texts have an inherent historicity, never emerging in isolation, but always combining and elements from other texts (Fairclough, Citation1992). This paper specifically focuses on intertextual chains of texts that build on each other as they transform from speeches to media articles, reports, books and casual conversations, each time being paraphrased, interpreted, critiqued or elaborated on (Fairclough, Citation1992). In this way, concepts and lines of reasoning can travel between different settings and gradually gain new meanings (Jessop, Citation2010). Our analysis unravels such intertextual chains by starting at the end point; policy documents related to the ban on tourist shops are gathered and systematically traced back the resources used to legitimize this policy. The first sample of policy documents included the Balanced City policy, communications about the Balanced City policy on the local government’s website and research reports used to motivate the ban on tourist shops or monitor its effects. From these documents, references to other documents and texts were identified and added to the sample.

The resources that are referred to range from specific documents to the activities of a stakeholder group or a key topic that has been discussed in print or social media. In case of references to an organization or initiative, relevant content for the sample is gathered from the initiative’s website, newsletter, and its Facebook and Twitter accounts. In some cases, references were made to a keyword that was discussed in print and social media. One of the policy documents that introduced the need to address touristification, claims that “ice cream and Nutella shops were frequently mentioned in media over the past year and a half as shops that annoy Amsterdammers” (City of Amsterdam, Citation2017, p. 11). In those cases, a keyword search was conducted with social media tools Coosto and Fanpage Karma. Coosto was also used to retrieve online news articles. Print media articles were gathered using the LexisNexis database. The references to keywords that we encountered were Nutellawinkel (Nutella shop) and toeristenwinkel (tourist shop). As a validity check, we also searched for synonyms to tourist shops that we found in the texts, such as toeristenmeuk (tourist trash). However, we found that those searches generated next to no new documents.

The referenced documents and texts were again searched for references. All gathered content relevant to tourist shops or beliefs about the inner city of Amsterdam was added to the sample. Our sample gathering stopped when content was no longer related to tourism or consumption spaces. Policy communications around the ban on tourist shops referred, for instance, to a very broadly formulated future vision for the metropolitan area of Amsterdam. Since this document does not refer to consumption spaces or tourism, it was not used to gather references to other texts. provides an overview of the number of posts or articles gathered from different sources.

Table 1. Overview of selected content.

Table 2. Summary of frames and social representations.

The sampled data was coded in different rounds using MaxQDA. The first round of coding distinguished the different diagnostic, motivational and prognostic frames. In subsequent rounds, the frames were combined into larger categories where appropriate. Several lines of argumentation were combined, for instance, into a motivational frame describing tourist shops as a slippery slope of touristification, which will only increase unless it is stopped by policy interventions. The next step looked for links between diagnostic, motivational and prognostic frames. A diagnostic frame that portrays tourist shops as criminogenic, for instance, links to a prognostic frame that proposes stricter monitoring and law-enforcement to reduce the number of tourist shops. This resulted in a reduced number of frames, including the main storylines where diagnostic, motivational and prognostic frames combine and create an urgent appeal to intervene.

The social representations that the frames resonate with largely emerged from the data sampling method. Tracing back references quickly revealed a number of key documents. These were all strategic research or policy documents, explicitly intended to promote a new understanding of the inner city. As such, they anticipate a wider discussion about the concepts as well as implementation in future policies (see Fairclough, Citation1992 for the role of anticipation in intextual chains). These documents were analyzed to identify normative values, cognitive beliefs and aesthetic elements they attribute to Amsterdam’s inner city, which, considering the strategic nature of the texts, were rather explicit. Due to the sampling approach based on intertextuality, we did not start with pre-conceived notions of what social representations have influenced frames around tourist shops. This revealed social representations about the inner city of Amsterdam that were coined in a completely different context than the context of touristification. This search identified a larger number of storylines than this paper could cover. The paper therefore does not give an exhaustive list of beliefs of Amsterdam’s inner city. Nor can it make any claims about the prevalence of these different beliefs. Rather, it identifies those beliefs that most clearly amplify the resonance of frames around tourist shops.

The results will first present the diagnostic, motivational and prognostic frames around tourist shops in Amsterdam. After that, the three most important beliefs about Amsterdam’s inner city that created cultural resonance are identified. In this way, we move beyond the way a problem is framed to include the extent to which the context in which the frames are received enable them to strike a responsive chord.

Diagnostic frames: defining the problem

Amsterdam has a long history with tourism that has always caused a certain level of resistance (Gerritsma, Citation2019; Nijman, Citation1999), but the most recent surge in resistance to tourism has emerged around 2014 (City of Amsterdam, Citation2015). In that year, local newspapers started publishing about congestion, nuisance and littering as a consequence of increasing numbers of visitors. Tourists are often depicted as culprits, in many accounts they are even de-personified by the use of metaphors. The most prominent metaphor compares increasing numbers of visitors to a natural disaster. It would be quite common, for instance, to find descriptions of tourists pouring into and flooding the city, or analogies of volcanic eruptions, explosions and tsunamis (“Amsterdam krijgt voorlopig geen “varende badkuip.”, Citation2015; Schoonenberg, Citation2016). Shops and consumption spaces were not immediately introduced into these debates around tourism, but entered the discussion in two ways.

First, before the rise of tourist shops was even reported as affecting livability for local residents, it was described as an indicator of money laundering activities. This concern first appeared in a newspaper article raising awareness for increasing drug trade in Amsterdam. The author linked fast-food and ice cream shops in the inner city to the drug trade, claiming ‘concerns are not about ice cream, but about laundering of drug money’ (Heijdelberg, Citation2015). This started persistent speculations on the legality of ice cream and waffle stores that gained recurring attention in local media for years after this first publication.

The second way in which consumption spaces were introduced in public debates around tourism, was through a petition named Save the Shops (Red de Winkels), started by a shop owner in Amsterdam’s inner city. The petition gained attention in local as well as national media. It drew attention to developments that actually largely predate the recent surge in tourism, such as the increasing number of chain stores, disappearance of small shops with an offer of daily products and the increasing prominence of hospitality over retail. So-called tourist shops were scapegoated for these transformations. This culprit frame frequently holds business owners personally responsible, portraying them as self-centered: “not asking themselves whether their shops or hospitality businesses benefit their environment, but only looking at how it affects their own wallets” (Crommert, Citation2017). A local politician even spoke of predatory entrepreneurs (roofondernemers in Dutch) (Boutkan, Citation2017).

The problematization of tourist shops seems to revolve around an interesting mix of national identity and socioeconomic status. Tourist shops are framed as lower quality in terms of their appearance, offer and appeal to people with unsophisticated taste. Touristy hospitality businesses, for instance, are often referred to as vreetwinkels (Chorus, Citation2017), referring to an unattractive way of overeating, and criticized for selling, unhealthy and high-calorie foods. Waffle stores started to play a prominent role in these debates. These also received criticism for their smell, described in Dutch as weeïg, which means sweet, but in a negative, nauseating way. Shops and hospitality businesses are also criticized for their lower status presentation, described as uncared for, shabby and flashy or obtrusive. These arguments are often used side-by-side with comments about representation of the Dutch identity or fit with local customs. English advertising and English shop names are problematized. Moreover, products such as waffles and churros are critiqued for not being Dutch. Consuming foreign snacks on a touristic visit to Amsterdam is seen as an indicator of bad taste and ignorance. Even cheese shops that specialize in Dutch cheeses are challenged for not fitting in with the local context, with the argument that Dutch people would visit a specialty cheese shop for foreign cheeses, but buy their Dutch cheese in the supermarket where it is more affordable.

All of these frames, problematizing the lower status, unhealthy foods, non-Dutch appearance and the suspicions of money laundering practices, seem to coincide in the Nutella shop. These waffle shops with large Nutella jars in the shopwindows gained popularity in the years prior to the Covid pandemic and became the stereotypical example of touristification. Nutella itself grew into a metaphor for lack of authenticity, blandness and alienation of local residents. This metaphor was successful in media as well. When Amsterdam introduced measures to curtail tourist shops, several newspapers quoted this as Amsterdam’s revolt against Nutella in headlines such as: ‘Legal help protects business owners from Nutella shops’, ‘This is my city, no Nutella dealer can take it away from me’, or ‘We are grateful for any business that does not transform into a Nutella shop’.

Motivational frames: the call to arms

The most frequently mentioned motivational frame, emphasizing the importance, urgency and need for intervention, is that increasing tourism threatens livability for inner city residents. A local newspaper illustrated this with vignettes of inner city residents planning to leave as a consequence of increasing tourism. They were described as oer- (ancient or native) and seasoned inner city residents that have stayed in the area through rough times, but were unable to cope with the effects of tourism:

“After having lived through the misery of the drug epidemic, it seemed that, due to resident protests, the neighborhood was doing better. However, recent years show an apparently irreversible deterioration.” (Appels, Citation2018).

Besides stressing the importance, there are also several frames that stress the urgency of interventions, for instance by referring to the situation in the inner city as ‘five minutes to twelve’ (Couzy, Citation2016). It is argued that touristy functions have found a business model that is hard to compete with as a non-touristy business. Tourist shops supposedly sell low value products with very high profit margins, a business model that drives up rent prices of property in touristy areas. As a result, businesses that offer value for money can no longer compete and will be displaced. Moreover, some argue that successful formulas of tourist shops are likely to be copied by other business owners. In line with the natural disaster metaphors used to describe increasing numbers of tourists, the increase in tourist shops is described as an uncontrollable overgrowth, or as businesses mushrooming or sprouting up (Bolderen, Citation2016; De Nutella-Explosie: Hoe Het Centrum Vol Wafelwinkels Kwam, Citation2018; Smithuijsen, Citation2016).

Prognostic frames: proposing a course of action

A final step in collective action frames is to propose a solution, as well as a responsible party to implement this solution. Up to some extent, it is argued that residents, business owners and property owners can all play a role in addressing tourist shops. Some point out, for instance, that residents increasingly shop at larger supermarkets and chain stores or online. This appeals to residents’ responsibility to buy local. This idea led to the emergence of Stichting de Goede Zaak (which could be translated to both ‘the just cause’ and ‘the right business’). The organization’s mission is to raise awareness for what it sees as desirable businesses among Amsterdam’s residents. It even hands out trademarks for businesses that provide a “contribution to the diversity of the shopping landscape in their street, neighborhood and city” (Stichting, Citationn.d.).

More often, however, the local government is seen as the responsible party to address touristification. A recurring question indignantly posed by resident organizations and echoed in media is how it is possible that the local government simply allowed increasing numbers of tourist shops to emerge. This illustrates the extent to which the local government’s power to intervene is taken for granted and even captured in the concept brancheren (branching). Another government-led solution that is frequently quoted is more monitoring and law-enforcement to counter the emergence of tourist shops, under the presumption that tourist shops are often fronts for money laundering. Prognostic frames thus seem to overestimate the local government’s power to intervene both with zoning instruments and monitoring procedures.

Beliefs about Amsterdam’s inner city

Three pre-existing beliefs about Amsterdam’s inner city amplify resonance of frames that problematize tourist shops. These portray the inner city as a delicate mix of functions; an infrastructure for criminal activities and a business card that reflects Amsterdam’s quality of place. In all three of these beliefs a specific text, policy or research project came to the fore as the most referenced and prominent articulation.

Functional mix: the inner city as a delicate mix of functions

The document that was most often referred to in discussions around tourist shops is a policy published in 1993, Beleidsplan Binnenstad, which reflects on the function of the inner city (City of Amsterdam, Citation1993). Such a reflection was necessary because of two developments. First, the inner city’s central function was increasingly undermined by suburbanization of both offices and retail (Duren & van Aart, Citation1995). Moreover, a consultancy agency found that local government employees experienced ambiguity in policies directed at different functions of the inner city (City of Amsterdam, Citation1993). There was a need for clearer guidelines on when and where to prioritize economic interests over residential concerns and vice versa. Beleidsplan Binnenstad aims to create these guidelines by distinguishing residential, economic and recreational functions as the three pillars that make the inner city a vibrant center. It depicts the inner city as a patchwork of small residential, economic and recreational concentrations, and emphasizes that all three functions need protection as they are all essential to the functional mix (City of Amsterdam, Citation1993).

The functional mix continues to be a powerful symbol, even though the challenges faced by the inner city changed. This representation originated in a context where economic and recreational functions were perceived as under threat, risking the inner city to become a residential, dormitory town. Instead, it is now the residential function that is perceived as under pressure, especially from increasing recreational functions that transform the inner city into a ‘theme park’. The normative belief that the inner city should be a mix of residential, economic and recreational functions thus remained the same, while the cognitive belief changed from a perception that the economic and recreational functions needed protection, to a situation in which the residential function needs protection from economic and recreational functions.

The functional mix initially referred to a mix of residential, economic and recreational functions and considered retail and hospitality businesses as part of the recreational function. Over the years, however, it started to be used to refer to diversity within the retail and hospitality landscape. The representation of a functional mix was used in 2013 to ban a number of retail businesses from zoning plans in the inner city. This concerned brothels, coffeeshops, grow-, head- and smartshops. The zoning plan argued:

“Although retail contributes to the functional mix (…) an excess of similar retail establishments is not desirable. An excess leads to monoculture and attracts a too uniform group of visitors” (City of Amsterdam, Citation2013).

The belief that represents Amsterdam’s inner city as a delicate mix of functions is directly reflected in diagnostic, motivational, and prognostic frames used in debates about tourist shops. This becomes evident not only from the use of the terms functional mix and diversity itself, but also from the extensive use of its antonyms, such as monoculture, uniformity, overgrowth and overconcentration. Similarly, the opposite of attachment to the city for inner city residents, alienation, frequently finds its way into debates around tourist shops. Frames that problematize tourist shops are therefore perceived as more natural and credible due to pre-existing beliefs of the inner city as a place of functional mix. The fact that the importance of functional mixing is articulated in policy documents and led to previous interventions where certain businesses were banned from zoning plans is also significant, as it implies that safeguarding the balance between these functions is a government responsibility and suggests that the local government has the ability and instruments to intervene.

The nefarious city: the inner city as an infrastructure for criminal activities

An alternative image that frames about tourist shops frequently refer to, presents the inner city as an infrastructure for criminal activities. These claims date back to a national enquiry conducted in the 1990s to evaluate the legitimacy and effectiveness of policing methods (Traa & Coenen, Citation1996). Amsterdam’s inner city, the Red Light district in particular, was included as a case study. The report introduced a new approach to studying criminal activities. Instead of only focusing on criminal activities as such, it argued that one should also consider the semi-legal or legal infrastructure that supports criminal activities. This infrastructure includes businesses that are used as a front for money laundering, but also businesses that are more loosely connected to criminal organizations. Hospitality businesses, for instance, were singled out for their role as the setting for meetings, recruitment of new members, liquidations or other criminal settlements, as well as the places where criminals spend their earnings. The report argues that to effectively reduce criminal activities, interventions should address the entire infrastructure of supporting semi-legal or legal businesses, where criminal activities are most disruptive to the wider society.

The appeal to address the criminogenic infrastructure in the inner city resulted in an ambitious project to reduce the size of criminogenic industries in the Red Light district. The project, named Plan 1012 after the Red Light District’s zip code was introduced in 2007. It was presented foremostly as a break with progressive policies towards prostitution, which received increasing criticism as turning a blind eye towards violence against women and “slave trade”(“Asscher: weg met Wallen hoofdstad,” Citation2005). Aalbers and Deinema (Citation2012) describe the project’s impact on perceptions of prostitution:

“Whereas up until recently regulated prostitution was sometimes, although not without controversy, associated with labor emancipation as well as with a progressive liberal value set, it is now branded as crude, amoral commercialism (…), or as ‘criminogenic’” (p.138).

With regard to cognitive aspects, businesses in the inner city of Amsterdam are considered vulnerable to competition with the large sums of money made in criminal activities and in need of laundering. This threatens the normative idea of a city that should be as free as possible from criminal interference, an idea that is hard to argue against. These arguments reverberate in the discussion around tourist shops and their alleged criminal activities. They lend credibility to the idea that tourist shops are actually money-laundering fronts that have been able to locate in the inner city despite due diligence checks that are in place. It also strengthens the idea that more monitoring and law-enforcement would result in a reduction of tourist shops in the inner city.

The aesthetic elements of this belief are less upfront, but are implied in descriptions of criminogenic businesses as negatively affecting the streetscape by their perceived uniformity and unkempt looks: “Besides the criminogenic aspect, many of these functions have a shabby appearance” (City of Amsterdam & Central city district, Citation2008, p. 6). This creates an association between small independent shops, especially more makeshift businesses (Hall, Citation2021), and criminal activities. The aesthetic aspects of shabby looking, lower status businesses, comes to the fore more clearly in the belief that depicts Amsterdam’s inner city as a business card.

The Red Carpet: the inner city as a business card

Besides reducing alleged criminogenic functions such as brothels, coffee shops and souvenir shops, Plan 1012 also aimed to introduce higher class economic functions (see Aalbers & Deinema, Citation2012 for a critique). The project’s starting document calls it “a revival of the entrance to Amsterdam. We aim to transform the uniform economic structure, with relatively many poor quality and nuisance causing functions, to a more diverse and high-end offer” (City of Amsterdam & Central city district, Citation2008, p. 4). It describes the inner city, especially the streets directly veering off the central train station where most visitors enter the city, as trashy and a poor representation of Amsterdam’s quality of place. It speaks of replacing the lower-value economic activities with higher status (hoogwaardige) functions and transforming the area into a Red Carpet into the city. This Red Carpet is described as a combination of “an A1-shop location with an international profile” and “small scale retail, craft, hospitality and offices, hotels and culture” (City of Amsterdam & Central city district, Citation2008, p. 12).

This representation of the inner city emphasizes the aesthetic aspects of allure and status. Feelings of attachment among residents of the wider metropolitan area also play an important role. It promotes the inner city as a place that these residents identify with and feel proud of. This comes with a normative element that considers the inner city of Amsterdam as a place that should be of high quality and high socioeconomic status. This amplifies frames problematizing lower status businesses in the inner city of Amsterdam as something that reflects on residents of the entire metropolitan area.

When it comes to cognitive beliefs, there seems to be a strong belief in symbolic value. The aim to upgrade is based on ‘key interventions’, a number of strategic, highly visible locations where an upgrade can take place. The belief is that when these symbolic functions are introduced the rest of the area will follow. The other way around, low quality functions located in highly visible places can cause deterioration of the area. This belief is echoed in motivational frames around tourist shops, which often stress how touristification occurs on a slippery slope: Once a number of businesses in the street start to change character, more will follow.

Discussion

This study was inspired by an unexpected policy shift with regard to tourist shops in Amsterdam. A local government coalition that started its term with the intention to deregulate the retail and hospitality sector, ended up introducing a legally challenging ban on tourist shops, stretching the limits of the level of regulation that national planning laws allow. The policy turn was claimed to be a response to increasing local resistance. However, the local resistance did not stem from an organized social movement that framed problems around tourist shops in a consistent and coherent way. Rather, it consisted of a loose collection of social media pages, small resident organizations, temporary protests and newspaper articles, all of which actually address a wide range of issues surrounding tourism. This seems at odds with earlier findings around framing and resistance to tourism, especially in Barcelona, which emphasize frame content and articulators as the main determinants of resonance (Milano et al., Citation2019; Russo & Scarnato, Citation2018).

Rather than by content and articulators, the success of frames that problematize tourist shops can at least partly be explained by their cultural resonance with pre-existing beliefs about Amsterdam’s inner city. By systematically unravelling the public debate, starting with policy documents around the ban on tourist shops and gradually retracing sources quoted in these policy documents to account for intertextuality, we arrived at three dominant frames about tourist shops, as well as three pre-existing beliefs about Amsterdam’s inner city that have increased frame resonance. Tourist shops in Amsterdam are problematized in diagnostic frames that portray them as creating a monoculture that threatens livability for local residents, as shabby and lower quality businesses and as criminogenic. Each of these frames are amplified by pre-existing beliefs. The touristy monoculture and threat to livability resonates with the belief that the inner city should contain a carefully balanced functional mix. The portrayal of tourist shops as lower social status resonates with the representation of the inner city as a business card, a Red Carpet that symbolizes Amsterdam’s quality of place. Lastly, the frame that depicts tourist shops as criminogenic resonates with pre-existing representations of the inner city as an infrastructure for criminal activities. Appealing to these pre-existing beliefs seems to have been a remarkably successful strategy in framing the emergence of tourist shops as an urgent, public problem that the local government needs to address.

A particularly influential belief portrays the inner city of Amsterdam as a criminal infrastructure, a representation that was integrated in local policies long before tourism started to surge in 2014. Initially coined to investigate criminal activities as part of a wider infrastructure, the concept has an ambiguous effect on discussions around tourist shops. The association with criminal activities makes problems around tourist shops more urgent and important and therefore legitimizes interventions. At the same time, the fact that it concerns criminogenic branches rather than actual criminal activities avoids the scrutiny that would be required to actually provide evidence of illegal actions. Perhaps most importantly, the believed vulnerability of consumption landscapes to criminal activities adds credibility to frames that scapegoat business owners as culprits.

Another notable finding is that apart from an appeal for residents to shop local, prognostic frames tend to see the local government as the responsible party to intervene. A possible explanation for this lies in the fact that the key documents that coined the most important social representations are all policy documents. This reinforces the idea that the local government is responsible for and able to protect a balanced consumption landscape. After all, policy interventions in consumption spaces in the past have been legitimized with exactly the same arguments. The fact that frames resonate with pre-existing beliefs that the local government has openly supported and claimed responsibility for, made it extremely difficult for the local government to ignore the problematization of tourist shops.

Conclusion

Our most important contribution is that frames will be amplified if they resonate with pre-existing beliefs that add to the credibility of the problem and the feasibility of the intervention. Some of these beliefs may occur in different contexts or even be linked to larger paradigms. However, the case of tourist shops in Amsterdam demonstrates how crucial circumstances that pressure local governments to intervene can be highly localized. The way forward to a better understanding of policy responses to resistance to urban tourism therefore requires close scrutiny of the local context that enables or forecloses the cultural resonance of frames on touristification.

These conclusions illustrate how the variety in policy responses to tourism can be a response to framing by social movements as much as to the observable physical impacts of urban tourism. This fits in with the growing literature on local resistance to tourism that moves beyond the objective impacts that are central in literature on overtourism (Capocchi et al., Citation2019) and includes framing as a central concept (Aguilera et al., Citation2021; Milano et al., Citation2019; Paredes-Rodriguez & Spierings, Citation2020; Russo & Scarnato, Citation2018). However, these studies on the role of framing in resistance to tourism have predominantly focused on frame content and articulators to explain the success of social movements that resist touristification (Milano et al., Citation2019; Russo & Scarnato, Citation2018). This explanation falls short, especially in cases such as Amsterdam where the level of organizational strength of social movements resisting touristification is limited and consensus on the nature, the urgency and the solution of the problem is far from self-evident. Such conditions are not typical for Amsterdam. Social movements resisting touristification are more often loosely organized coalitions consisting of smaller resident or other interest groups with conflicting interests (see Vianello, Citation2016 for an example from Venice). Our findings therefore contribute a focus on cultural resonance.

For future research, we recommend more attention to the context in which the frames are received. Besides cultural resonance, this could include aspects such as the extent to which the problems addressed in frames are tangible and play a central role in the everyday lives of the audience (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). Another interesting direction for future research would be to investigate the role of cultural resonance in explaining a lack of frame resonance. It would be worthwhile to consider pre-existing beliefs in tourism destinations where resistance to tourism has been relatively absent or unsuccessful, as it is argued to be in Paris (Gravari-Barbas & Jacquot, Citation2016).

Taking framing seriously has important managerial implications for the ambition to foster accessible and inclusive urban environments (SDG 11), since it inevitably introduces questions of power: Inclusive and accessible for whom? The case of tourist shops in Amsterdam demonstrates how this can leave local governments in a difficult position. On one hand, tourism can affect the inclusivity and accessibility of inner city consumption spaces for local residents. They may feel alienated from a consumption landscape that mainly caters to tourists or even lack access to daily goods and services (Guimarães, Citation2021; Novy & Colomb, Citation2019). With the sustainability of the inner city community in mind, local governments should therefore take concerns about the effects of tourism at heart. On the other hand, inclusivity and accessibility should also extend to tourists and the tourism sector. In our case in Amsterdam, framing strategies depicted tourists as a natural disaster and entrepreneurs in the tourism sector as criminals. The local government responded too readily to these highly resonating frames, introducing policies that stereotype tourists and exclude entrepreneurs. This does not only affect inclusivity, but also undermines the positive contributions tourists and the tourism sector could make to the city’s resilience and cultural diversity.

These findings call for an approach that pacifies rather then escalates frames around touristification. To achieve this, we would propose to address the most important nuisance-causing malpractices on a small scale in cooperation with local stakeholders, but aim to disentangle them from a wider debate about touristification. Such a small scale, urban acupunctural approach (Lerner, Citation2014) allows more focus on tangible issues and contextualized solutions, while minimizing effects to the wider entrepreneurial climate. The public debate on the future of tourism at the urban scale should strive to use more inclusive language. Several authors have warned for risks of scapegoating, where tourism is blamed for effects that are also a product of other societal changes such as globalization, gentrification and digitalization. In fact, these changes led to an increase in protests and contestations that predated the most recent surge in tourism (Clancy, Citation2020; Novy, Citation2019). Tourists and tourism sector can then become subject to ‘othering’ narratives that are exclusionary and ultimately unproductive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalbers, M. B., & Deinema, M. (2012). Placing prostitution: The spatial-sexual order of Amsterdam and its growth coalition. City, 16(1-2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.662370

- Adie, B. A., Falk, M., & Savioli, M. (2020). Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Europe. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(14), 1737–1741. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1687661

- Aguilera, T., Artioli, F., & Colomb, C. (2021). Explaining the diversity of policy responses to platform-mediated short-term rentals in European cities: A comparison of Barcelona, Paris and Milan. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(7), 1689–1712. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19862286

- Amsterdam krijgt voorlopig geen “varende badkuip.” (2015). Trouw. https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/amsterdam-krijgt-voorlopig-geen-varende-badkuip∼b0279dc1/?referrer=https%3A//www.google.com/

- Appels, E. (2018). “De toeristentroep wint, ik vertrek.” Het Parool. https://www.parool.nl/columns-opinie/de-toeristentroep-wint-ik-vertrek∼b5ac5ccd/

- Asscher: weg met Wallen hoofdstad. (2005). NRC Handelsblad. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2005/12/01/asscher-weg-met-wallen-hoofdstad-11050583-a539627

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Blumer, H. (1971). Social problems as collective behavior. Social Problems, 18(3), 298–306. https://doi.org/10.2307/799797

- Bolderen, E. V. (2016). Actie verpaupering: ‘binnenstad plat en commercieel.’ Metro. https://www.metronieuws.nl/in-het-nieuws/binnenland/2016/02/actie-verpaupering-binnenstad-plat-en-commercieel/

- Boutkan, D. (2017). “Bescherm de stad tegen roofondernemers.” Het Parool. https://www.parool.nl/columns-opinie/bescherm-de-stad-tegen-roofondernemers∼bcaf1f0b/

- Budd, K., Kelsey, D., Mueller, F., & Whittle, A. (2019). Metaphor, morality and legitimacy: A critical discourse analysis of the media framing of the payday loan industry. Organization, 26(6), 802–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418812569

- Buijs, A. E., Arts, B. J. M., Elands, B. H. M., & Lengkeek, J. (2011). Beyond environmental frames: The social representation and cultural resonance of nature in conflicts over a Dutch woodland. Geoforum, 42(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.12.008

- Capocchi, A., Vallone, C., Pierotti, M., & Amaduzzi, A. (2019). Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability, 11(12), 3303–3321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123303

- Castells, M. (1983). The city and the grassroots: A cross-cultural theory of urban social movements. University of California Press.

- Chorus, J. (2017). Kaasjagers op het Damrak. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2017/12/13/kaasjagers-op-het-damrak-a1584723

- City of Amsterdam & Central city district. (2008). Hart van Amsterdam: Strategienota Coalitieproject 1012. https://hetccv.nl/fileadmin/Bestanden/Onderwerpen/Prostitutiebeleid/Documenten/Nieuwe_ambities_voor_de_Wallen/amsterdam_strategienota.pdf

- City of Amsterdam. (1993). Beleidsplan Binnenstad. https://openresearch.amsterdam/image/2018/5/7/beleidsplan_1993.pdf

- City of Amsterdam. (2013). Bestemmingsplan Postcodegebied 1012. https://www.planviewer.nl/imro/files/NL.IMRO.0363.A1403BPSTD-VG01/r_NL.IMRO.0363.A1403BPSTD-VG01.html

- City of Amsterdam. (2015). Stad in Balans. https://www.amsterdam.nl/gemeente/volg-beleid/stad-balans/

- City of Amsterdam. (2017). Sturen op een divers winkelgebied. https://www.amsterdam.nl/publish/pages/823066/rapport_sturen_op_een_divers_winkelgebied_def_versie_28_feb_10_mb.pdf

- City of Amsterdam. (2018). Winkeldiversiteit Centrum. https://www.ruimtelijkeplannen.nl/web-roo/transform/NL.IMRO.0363.A1801PBPSTD-VG01/pt_NL.IMRO.0363.A1801PBPSTD-VG01.xml 1/111

- Clancy, M. (2020). Overtourism and resistance: Today’s anti-tourist movement in context. H. Pechlaner, E. Innerhofer & G. Erschbamer (Eds.), Overtourism: Tourism management and solutions. Routledge, London. 14–24.

- Cocola-Gant, A., & Gago, A. (2021). Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(7), 1671–1688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19869012

- Cornelissen, J. P., & Werner, M. D. (2014). Putting framing in perspective: A review of framing and frame analysis across the management and organizational literature. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 181–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.875669

- Couzy, M. (2016). Van der Laan : ‘ Echte oplossing voor drukte in de stad nog niet gevonden ‘. Het Parool. https://www.parool.nl/nieuws/van-der-laan-echte-oplossing-voor-drukte-in-de-stad-nog-niet-gevonden∼ba21215d/

- Crommert, R. v d. (2017). Geef De Stad Terug”: Actie tegen monocultuur. Telegraaf.

- Dodds, R., & Butler, R. W. (Eds.). (2020). Overtourism: Issues, realities and solutions. De Gruyter.

- Duren, A. J., & van Aart, J. (1995). De dynamiek van het constante : over de flexibiliteit van de Amsterdamse binnenstad als economische plaats. Van Arkel. http://dare.uva.nl/search?arno.record.id=8064

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Intertextuality in critical discourse analysis. Linguistics and Education, 4(3–4), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0898-5898(92)90004-G

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213

- Gerritsma, R. (2019). Overcrowded Amsterdam: Striving for a balance between trade, tolerance and tourism. C. Milano, J.M. Cheer & M. Novelli (Eds.), Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism, CABI, Wallingford UK, 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786399823.0125

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

- Gravari-Barbas, M., & Jacquot, S. (2016). No conflict?: Discourses and management of tourism-related tensions in Paris. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City, 1, 31–51. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719306

- Guimarães, P. (2021). Retail change in a context of an overtourism city. The case of Lisbon. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(2), 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-11-2020-0258

- Hajer, M., & Uitermark, J. (2008). Performing authority: Discursive politics after the assassination of Theo van Gogh. Public Administration, 86(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00701.x

- Hall, S. M. (2021). The Migrant’s Paradox street livelihoods and marginal citizenship in Britain. University of Minnesota Press.

- Hagemans, I. W., Spierings, B., Weltevreden, J. W. J., & Hooimeijer, P. (2023). owd-pleasing, niche playing and gentrifying: Explaining the microgeographies of entrepreneur responses to increasing tourism in Amsterdam. Annals of Tourism Research, 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103627

- Heijdelberg, E. (2015). “Amsterdam is uitgegroeid tot de Europese pillenhoofdstad.” Het Parool. https://www.parool.nl/columns-opinie/amsterdam-is-uitgegroeid-tot-de-europese-pillenhoofdstad∼bf3f7ede/

- Innerhofer, E., Erschbamer, G., & Pechlaner, H. (2019). Overtourism. In H. Pechlaner, E. Innerhofer, & G. Erschbamer (Eds.), Overtourism: The challenge of managing the limits (pp. 3–13). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429197987

- Jessop, B. (2010). Cultural political economy and critical policy studies. Critical Policy Studies, 3(3–4), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171003619741

- Keulartz, J., Van Der Windt, H., & Swart, J. (2004). Concepts of nature as communicative devices: The case of Dutch nature policy. Environmental Values, 13(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327104772444785

- Koens, K., Postma, A., & Papp, B. (2018). Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 10(12), 4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124384

- Lerner, J. (2014). Urban acupuncture. Island Press. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-584-7

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1857–1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

- Nijman, J. (1999). Cultural globalization and the identity of place: The reconstruction of Amsterdam. Ecumene, 6(2), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/096746089900600202

- Novy, J. (2019). Urban tourism as a bone of contention: Four explanatory hypotheses and a caveat. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-01-2018-0011

- Novy, J., & Colomb, C. (2019). Urban tourism as a source of contention and social mobilisations: A critical review. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(4), 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1577293

- Nutella-Explosie, D. (2018). Hoe het centrum vol wafelwinkels kwam. https://www.at5.nl/artikelen/186142/de-nutella-explosie-hoe-het-centrum-vol-wafelwinkels-kwam

- Ojeda, A. B., & Kieffer, M. (2020). Touristification. Empty concept or element of analysis in tourism geography? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 115(June), 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.06.021

- Paredes-Rodriguez, A. A., & Spierings, B. (2020). Dynamics of protest and participation in the governance of tourism in Barcelona: A strategic action field perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2118–2135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1791891

- Paternotte, J., Burg, E. v d., & Ivens, L. (2014). Amsterdam is van iedereen: Coalitieakkoord 2014 - 2018. https://assets.amsterdam.nl/publish/pages/900484/collegeakkoord_2014-2018.pdf

- Phi, G. T. (2020). Framing overtourism: A critical news media analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(17), 2093–2097. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1618249

- Poletta, F., & Ho, M. K. (2006). Frames and their Consequences. In R. Gooden & C. Tilly (Eds.), The Oxford handbooks of contextual political studies. Oxford University Press. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.465.2583&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Postma, A., & Schmuecker, D. (2017). Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2017-0022

- Rijksoverheid. (2008). Wet Ruimtelijke ordening. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2008-145.pdf

- Romero-Padilla, Y., Cerezo-Medina, A., Navarro-Jurado, E., Romero-Martínez, J. M., & Guevara-Plaza, A. (2019). Conflicts in the tourist city from the perspective of local social movements. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 83(83), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.2837

- Russo, A. P., & Scarnato, A. (2018). “Barcelona in common”: A new urban regime for the 21st-century tourist city? Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(4), 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1373023

- Schoonenberg, W. (2016). Interview met Stephen Hodes ‘ Deltaplan toerisme nodig ‘. Binnenstad. https://www.amsterdamsebinnenstad.nl/binnenstad/277/interview-hodes.html

- Schweinsberg, S., Darcy, S., & Cheng, M. (2017). The agenda setting power of news media in framing the future role of tourism in protected areas. Tourism Management, 62, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.011

- Smith, M. K., Sziva, I. P., & Olt, G. (2019). Overtourism and resident resistance in Budapest. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(4), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1595705

- Smithuijsen, D. (2016). Monte Pelmo werd gered, maar toen kwam Nutella. 1–5. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2016/02/05/monte-pelmo-werd-gered-maar-toen-kwam-nutella-1585040-a1279074

- Stichting, d. G. Z. (n.d.). Keurmerk “De Goede Zaak Amsterdam.” Retrieved June 13, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221007195806/https://www.degoedezaak.amsterdam/keurmerk

- Tilly, C. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

- Traa, M. v., & Coenen, N. J. P. (1996). Enquete opsporingsmethoden. Sdu Uitgevers.

- van Eck, E., Hagemans, I., & Rath, J. (2020). The ambiguity of diversity: Management of ethnic and class transitions in a gentrifying local shopping street. Urban Studies, 57(16), 3299–3314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019897008

- Vianello, M. (2016). The No Grandi Navi campaign: Protests against cruise tourism in Venice. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City. Johnson, 2002, 171–190. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719306