Abstract

This article, and the special issue, seek to unpack the gendered nature of entrepreneurial pathways, specifically in relation to the role of social policies. We achieve this aim by first conceptualising gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy, to highlight the need to generate a stronger research agenda on the role of social policy within gender and tourism entrepreneurship research. We next outline an overarching framework for delineating the intersection of gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy, based on a critical review of existing studies, as well as by situating the papers in this special issue. We present this discussion through three thematic framings: (1) gender and entrepreneurship, (2) gender and social policy and (3) entrepreneurship and social policy. In conclusion, we discuss the implications for social policy and practice, and in doing so call for a research agenda that situates social policy more centrally within considerations of gender and tourism entrepreneurship.

Introduction

This special issue offers a novel contribution to the current conversations related to gender and tourism entrepreneurship by interrogating the role of social policies in facilitating inclusive tourism entrepreneurship. The UNWTO (Citation2017) has identified tourism entrepreneurship as fundamental to meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals of gender equality (SDG 5), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8) and sustainable consumption and production (SDG 12). At the same time, it is recognised that the tourism sector provides employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for those in subordinate positions within society, with both employment and entrepreneurial opportunities being vital for economic and social independence. For women (and other disadvantaged entrepreneurs), their tourism businesses often act as platforms for the promotion of local development and social transformation, enabling the creation of “new” subjectivities (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016; de Jong, Citation2017; Carr et al., Citation2016). And yet, as Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020, p. 1) note, “neither entrepreneurship nor sustainability are gender neutral in the tourism industry”, whilst engagement with policy is notably absent within research on gender and tourism entrepreneurship (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020) in spite of the recognised critical role of gendered social policies in influencing labour market opportunities (Thébaud, Citation2015).

Covid 19, and the effects of the war in Ukraine, have exacerbated the multiple challenges faced by all entrepreneur owner/managers of tourism firms, bringing attention to the important role governance and policy undertakes in supporting tourism entrepreneurs. The effects, during the pandemic, and the subsequent cost of living crisis and ongoing recovery, are even worse for tourism destinations of the Global South (where the majority of tourism micro, small and medium sized enterprises (MSMEs) are owned by women and members of disadvantaged groups and communities) who unlike tourism and hospitality businesses of the Global North, have had little-to-no support from their national governments in response to Covid 19. This has led to the closure of many tourism and hospitality businesses, placing many millions of jobs at risk and threatening to roll back the progress made in sustainable development (Rogerson & Baum, Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2020). Consequently, according to the UNWTO’s Tourism Recovery Tracker (2023) tourism destinations (especially in the Global South), who are for the most part dependent on international visitors, were the worst hit and have been the slowest to respond to Covid 19. The crisis has laid bare the precarity of entrepreneurial tourism operations, especially MSMEs; whereby entrepreneurs operating MSMEs were largely unprepared for such crises and lack the resilience to respond and overcome it (Kimbu et al., Citation2023). All of which highlights the crucial role social policy plays in ensuring the sustainability of entrepreneurs and their businesses broadly but also specifically within Global South contexts.

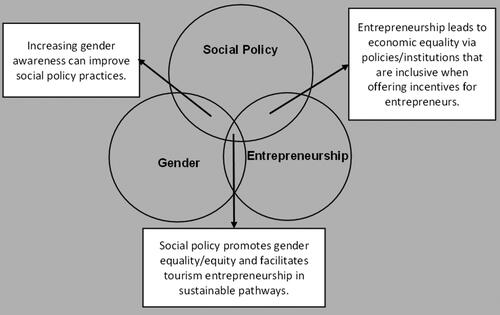

Our vision is a future where a large body of relevant and interdisciplinary research that addresses these intersections is available to all stakeholders, where there is fluid transfer of knowledge and tools between academic, industry and policy networks to create a more inclusive environment for entrepreneurs, and where entrepreneurial opportunity is not reduced to one’s subjectivities and/or geographical location. In examining the interplay between gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy this special issue calls for stronger engagement with social policy, within research examining gender and tourism entrepreneurship, to better understand the crucial role social policy plays in facilitating tourism entrepreneurship in sustainable ways (see ). For example, whilst the field of entrepreneurship certainly includes the study of how social policy may influence women to opt for business ownership (Thébaud, Citation2015) and the extent to which entrepreneurship promotes or reinforces inequality (Bruton et al., Citation2021) – there remain critical distinctions between entrepreneurship and social policy. Moreover, though entrepreneurship has been found to contribute to equality/equity and increasing gender awareness has been shown to improve social policy (Guzman & Kacperczyk, Citation2019; Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Sajjad et al., Citation2020, Avnimelech & Rechter, Citation2023), these three fields have not been studied together. Taking these gaps as our starting point, this special issue begins to define and establish a distinctive field integrating gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy.

Figure 1. Mapping the conceptual domain of gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy linkages. Source: Authors’ conceptualization.

A recent special issue (SI) on Gender and Tourism Sustainability in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 30(7) (Eger et al., Citation2022), provides a useful starting point for discussing the relevance of our focus on the intersection of gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy. The SI contributors apply different feminist epistemologies to challenge understandings, interpretations and (non)application of sustainability knowledges within different tourism contexts (social, economic, and political). In doing so, they broadly (re)conceptualise and unpack the different spectrums of gender, while calling for researchers to adopt a pluralistic view when generating knowledges, taking cognisance of the multiple and diverse ecologies within which, they operate beyond established and institutionalized models, ideologies, and platforms. Entrepreneurship and policy feature among the themes discussed in the SI but are not taken as the focus. As such, this special issue extends that of Eger, Munar and Hsu’s (2022) special issue, by taking focus with specific themes related to gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy.

Drawing on in-depth, situated case studies from across the Global South and Global North, our multi-disciplinary special issue identifies how context-driven factors influence the experiences and potentialities of tourism entrepreneurship as a promised avenue for inclusive growth. Problematizing universalised constructions of entrepreneurs as necessarily masculine, western, and driven only by economic imperatives that seek to fix and dislocate entrepreneurial support, we take focus with place-based approaches to identify the nuances and tensions between subjectivity, tourism entrepreneurship and social policy. This allows us to account for the complexity of entrepreneurial experience, and the role of social policy within different geographical settings.

The article is structured as followed: Section “Conceptualising gender, entrepreneurship and social policy in Sustainable Tourism” provides a review of the key literature for conceptualising gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy. In particular, the section presents our organising framework, to initiate consideration of the interrelationships between gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy. Section “Summaries of contributions in the special issue” provides insight into the papers in this special issue, contrasting findings from existing studies that engage with the themes of gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy. In Section “Tying the knot and setting a research agenda”, we seek to tie the knot by outlining the key contributions of the special issue, putting forth our agenda for additional research on this topic, while Section “Conclusion” concludes the article with a reflection on social policy and its practical implications to the gendered dimensions of tourism entrepreneurship.

Conceptualising gender, entrepreneurship and social policy in sustainable tourism

In developing this special issue, we have taken particular interest in research that engages with critical feminist and post-colonial perspectives. Incorporating critical social theory enables insight into how gender is a fluid performance, rather than essentialist and fixed (Butler, Citation1990; Young, Citation1990), whereby historic, social, and cultural meanings produce a multiplicity of complex subjectivities that cannot be reduced to simplistic, singular categorisations – such as “women entrepreneur” (Butler, Citation1990). It is now commonplace within critical tourism research to conceptualise gender as multiple, fluid and constructed. However, as identified by Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020) in their systematic literature review, prescriptive and binary categorisation continues to prevail in research examining gender and tourism entrepreneurship. This is, in part, because there is an inherent tension between the fluidity of identity sought by poststructuralism and the desire to prompt social change by fostering the visibility of “women” within tourism entrepreneurship contexts; whereby, it becomes necessary to engage with discourses that represent gender as a stable category (Butler, Citation2003).

More specifically, within tourism entrepreneurship policy, characteristics pertaining to a “successful” entrepreneur have tended to align with masculine performance, whereby the category “women entrepreneurs” has come to be viewed as lacking in comparison to an assumed and unquestioned masculine norm (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2012; Citation2019; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). “Success” being narrowly defined as an ability to accrue wealth and enact innovation. Such definitions prevail despite the recognition that success for many entrepreneurs is more broadly defined, often through non-economic terms, and includes considerations of flexibility, lifestyle, and empowerment (cf. Bakas, Citation2017; Kimbu et al., Citation2019). This gender bias is largely a result of the construction and prioritisation of “men’s” experiences within entrepreneurship discourse, with this broader entrepreneurship discourse being used to inform early entrepreneurial discourse within the tourism field (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). In consequence, much of the entrepreneurship discourse within tourism fails to recognise that “men’s” experiences are in fact gendered rather than a universalised norm; an outcome that serves to reemphasise the need to apply a gendered lens to the entrepreneurial performance of all entrepreneurs.

There are important implications of this gender bias within the context of social policy. Hierarchical gendered structures have led to the construction of policy agendas that seek to rectify the perceived failure of “women” to enact “successful” entrepreneurship. “Women entrepreneurs” are thus often constructed within policy as requiring support to increase the growth of their businesses, and through this act, the diversity of support that could be provided to assist entrepreneurs to enact meaningful entrepreneurial performances becomes overlooked and uncontextualized. Social policy thus plays an important, yet largely unexplored, role within the context of tourism entrepreneurship because it produces the political structural opportunities and barriers that construct entrepreneurial subjects as necessarily either “men” or “women”, in ways that shape what becomes possible within specific contexts.

As such, in seeking to advance social change through critical engagement with social policy discourse, the articles in the special issue do engage with the gendered categorisations of “men” and “women”. An approach that does, at times, run counter to the poststructuralist approach. This is particularly pertinent in relation to the subject of “women”, a category that several of the articles in the special issue take focus with because it is a social category that continues to be misrepresented as “less than”, within policy discourse relating to tourism and entrepreneurship. Recognising this limitation, the special issue has selected a broad array of papers that present a multiplicity of intersectional identities and experiences from a range of international geographical contexts, so as to emphasise the historic, social, and cultural ways through which subjectivities are produced and the conditions through which they become fixed.

The difficulties in conducting research that draws on a multiplicity of cases from across the world are well documented and has contributed to the dearth of up-to-date findings. Bakas (Citation2018), by way of example, brought attention to the challenges in undertaking in-depth ethnographic research with Greek women entrepreneurs because femininity in this context is connected to “being constantly busy”. Henry et al. (Citation2015) further note that the very cultural, legislative, and economic frameworks that present gendered challenges for some entrepreneurs also present barriers for those seeking to research underrepresented groups because such entrepreneurs from these groups are more likely to be invisible and inaccessible. Such challenges perhaps influence Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020) finding derived from a systematic review of gender, tourism and entrepreneurship literature published in English, French and Spanish, that there are low levels of gender and tourism entrepreneurship research coming from Africa and Asia, and even less from Central and South America. To ensure a representative sample of countries and geographic coverage, the articles have been selected to reflect geographical regions currently underrepresented. The contributors to this volume are interdisciplinary, consisting of scholars from the Global North and South, across five continents.

Finally, there is a tension within this area of research between the need for in-depth qualitative research that seeks to capture the complexity of gendered experience, arguably more likely to be implemented by scholars engaging with critical feminist and post-colonial approaches, and the requirement for larger scale quantitative research that produces transferable findings that are perceived as more useful to policy makers. In editing this special issue, we have taken the position that gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy research would further benefit from deconstructing this methodological dichotomy through the incorporation of a wide range of qualitative and quantitative methods. We thus hope to highlight the value in uniting various methods through this topic.

Summaries of contributions in the special issue

In this section, we will set out what is known within existing literature regarding the interlinkages between gender, entrepreneurship and social policy, and the ways through which this special issue extends and unites this area of research. We divide Section “Summaries of contributions in the special issue” into three sub-sections, in turn examining the nuanced relationships between gender and entrepreneurship (Section “Gender and entrepreneurship”), gender and social policy (Section “Gender and social policy”) and social policy and entrepreneurship (Section “Social policy and entrepreneurship”); before turning to consider the broader interlinkages and reflecting on a future research agenda in Section “Tying the knot and setting a research agenda”. We recognise that dividing the articles in this way is somewhat cosmetic, given that all articles cover the themes of gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy. We take this approach, however, as a way to highlight and unite the central contributions within and across the articles.

Gender and entrepreneurship

Recent research that has focussed on examining the nexus between gender and entrepreneurship in tourism within the last decade has examined themes related but not limited to women and tourism social entrepreneurship (Kalisch & Cole, Citation2022; Kimbu & Ngoasong, 2016), gender and intra/entrepreneurial leadership (Zhang et al., Citation2020; Kimbu et al., Citation2021), gender and entrepreneurial finance (c.f. Deen et al., Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2022), gender, sustainability and entrepreneurial orientation in tourism (c.f. Kearins & Schaefer, Citation2017; Ribeiro et al., Citation2021; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020; Kimbu et al., Citation2019), and gender biases in entrepreneurial discourse in tourism knowledge generation (Elam, Citation2008; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2015; Citation2020). These studies adopt different feminist methodological approaches to examine gendered entrepreneurial pathways across both Global North and Global South contexts. A major limitation of this research has been their focus on European, North American, and African case studies. Moreover, even though they do underscore the importance of concrete social (and economic) policy formulation and implementation in the different contexts to address extant challenges and barriers faced by tourism entrepreneurs in relation to gender, critical examination of the ways policy unfolds within unique geographical contexts is lacking. In consideration, in collating this special issue we sought to extend insight regarding the geographical areas in which tourism entrepreneurship unfolds and how this produces a multiplicity of entrepreneurial performances. In doing so, we seek to broaden understanding regarding the heterogenous ways social policy might be constructed to support tourism entrepreneurs.

A key theme in considering the intersection of gender and entrepreneurship is with how women entrepreneurs employ entrepreneurial strategies in responding to crisis in ways that are unique to their geographical setting. Maliva et al.’s (Citation2023) contribution to this special issue, for example, examines the gendered impacts of Covid 19 on the welfare of women entrepreneurs in Tanzania. Through a conceptualisation of entrepreneurship as a contextual and socially embedded response to crisis, they analysed interview data on 51 women working in Tanzania. The women in this study are not only impacted by the pandemic, but they are also simultaneously positioned within a patriarchal society that does not value “women’s work” or women’s contributions to work. This is understood to be a precarious positioning that led many of the participants to be vulnerable to exploitation. Responding to this precarity, three entrepreneurial strategies were drawn on by the participants (i) (re)commit to the tourism industry, working on developing their own skills and business ideas; (ii) diversify business interests to have a “Plan B” in addition to tourism to safeguard against future crises; (iii) move away from tourism altogether, focusing instead on other less volatile sectors. These strategies highlight the multiplicity of entrepreneurial performance in the ways they both embody and transform the entrepreneurial norm – providing important policy insights regarding why women may choose to refocus their ambitions outside of tourism in response to crisis.

Similarly taking focus with the lived experience of crisis within a specific geographical setting, Filimonau et al. (Citation2022) article in the special issue examines how women entrepreneurs sustain their motivations to become entrepreneurs in destinations affected by the legacy of an anthropogenic environmental disaster. They draw on Bourdieu’s model of practice to analyse the experiences of 28 women entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Their study reveals insights into the necessity-based and extrinsic motivations of women entrepreneurs to start a business in a time of crisis. To respond to the crisis, women entrepreneurs use social capital, constructed through interactions with family, friends, policymakers, and employees, alongside local cultural traditions, to respond to risks posed by the crisis. Filimonau et al.’s findings highlight the importance of policymakers in facilitating opportunities for women entrepreneurs to build social capital, through organising workshops and inviting agents that might be otherwise difficult for women entrepreneurs to engage.

Turning to explore the entanglements between culture, entrepreneurial finance and policy, Lin et al.’s (2023) inclusion in the special issue likewise provides insights into the factors that are essential for inclusive entrepreneurship. In assessing the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor dataset, alongside other secondary datasets, and engaging with pecking order, information costs and lack-of-fit theories, their research brings attention to the ways that women entrepreneurs located in countries with high gender inequality are more likely to face higher information costs in preparing their entrepreneurial ventures. This is mainly due to the challenges of networking in male-dominated fields. As a result, it is identified that women entrepreneurs tend to network informally, and may find informal finance to be more accessible than formal finance. These findings extend and compliment the work of Deen et al. , who similarly identify the challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in regard to finance, and associated bureaucracy. Recognising that finance is integral to business viability, we echo Deen et al. call for governments and funding organisations to reconsider the ways through which financial assistance is granted.

More broadly, much of the data reported by the authors of the articles in this special issue were collected either before or during the Covid 19 pandemic. As such, the Covid 19 pandemic is a reoccurring point of focus, often discussed through the lens of entrepreneurial resilience. The findings thus provide a timely response to the call proposed by the UNWTO (Citation2021) for tourism recovery policy to be gender-sensitive and geographically inclusive in the post-Covid era.

As a concept, entrepreneurial resilience is traditionally viewed as “bouncing back” to pre-existing conditions. Critical tourism scholars have cautioned that “bouncing back” narratives reinforce the prevailing growth model of tourism, which places immense social and environmental pressures on vulnerable landscapes. Alternatively, it has been suggested that “build forward better” considerations might enable opportunity to deconstruct the structural inequalities that prevail within pre-existing capitalist growth models (Cole & Gympaki, Citation2021). The traditional “bouncing back” narrative has also been shown as less relevant under conditions of liminality – that is, conditions where existing systems (e.g., rules, norms, regulations, policies, and procedures) become ineffective, whilst new systems are not yet institutionalized; such is arguably the case “post” Covid 19 (John et al., Citation2022).

The articles in this special issue further engage with these ideas, in pointing to inefficiencies in existing institutional policies relating to tourism entrepreneurship experiences post-pandemic. In recognising both the gendered inefficiencies of existing policies, alongside the considerable contextual changes that occurred through the pandemic, it becomes imperative for future tourism research and social policy to engage an alternative view of resilience as a capacity for women entrepreneurs to achieve sustainability for their business in more heterogenous ways, rather than as something defined as returning to what was pre-pandemic. Such an alternative view of resilience will address the false dichotomy that women-owned businesses coped with Covid 19 by either “bouncing back” or “bouncing forward”. Rather, as this special issue has identified, instead of returning to the old ways of working (bouncing back), women entrepreneurs often opted for transformation (bouncing forward), or something else entirely (Maliva et al., Citation2023). In this regard, social policy needs to remain attuned to (1) how entrepreneurial resilience of women entrepreneurs is conceptualised and differs between geographical contexts; (2) the complexity of sustainable business model archetypes that women can adopt to survive and thrive during and after a crisis; and (3) how policy support for women entrepreneurs can further enhance entrepreneurial resilience in times of crisis.

Kutlu and Ngoasong (Citation2023) addition to the special issue likewise engages with the Covid 19 crisis to bring attention to the ways policy places expectations on women entrepreneurs to fulfil political objectives, without sufficient governmental support. Taking focus with the context of Turkey, they note that the Turkish government has developed environmental legislation to encourage the sustainability practices of tourism entrepreneurs. They identify, however, that there is limited support and knowledge exchange in place to assist entrepreneurs to facilitate the policy. As is often the case, the tourism industry in Turkey is characterised as a women-intensive sector, with the dominance of entrepreneurship occurring in MSMEs. Thus, the Turkish government has effectively produced a context whereby women entrepreneurs managing MSMEs are required to implement sustainability measures without support or knowledge of sustainability. The challenge in enacting this policy was further exacerbated by the Covid 19 pandemic – whereby women entrepreneurs were found to be more effected than men entrepreneurs. Kutlu and Ngoasong (Citation2023) thus identify that the women entrepreneurs that they studied faced immense challenges in securing buy-in from environmentally focused suppliers and customers because they lacked the ability to comply with environmental legislation. The authors argue that if tourism is to be intersected with sustainability and environmental policy, stronger integration is required; whilst social policy needs to be designed in ways that is complimentary to both, such as through greater access to finance and the reduction of bottlenecks. More broadly, Kutlu and Ngoasong (Citation2023) argue, gender aware, rather than gender equal or gender-neutral policy framings are required, to counter the structural and social inequalities experienced by women entrepreneurs in Turkey. “Gender equal” or “gender-neutral” policy framings, following Kutlu and Ngoasong (Citation2023), tend to recognise the challenges women encounter in seeking to enact sustainability but are not effective in destabilising and/or transforming the subordinate positioning of women entrepreneurs. Gender aware policy framings, by contrast, seek to rectify the challenges facing women through positive action. An example of a “gender aware” policy would be investment in public infrastructure that holds relevance to women (e.g., funded nursery schools). However, policies need to move beyond being gender equal or gender aware to being gender transformative to engender wider and deeper impacts among women entrepreneurs.

Taking focus with 33 women entrepreneurs in Mexico and Ecuador, Khoo et al. (Citation2023) inclusion in the special issue takes a different direction then the above articles in focusing on the digital competencies of women entrepreneurs. Their findings align with those of Kutlu and Ngoasong (Citation2023), however, in highlighting the need for gender aware social policy that rectifies the structural and social inequalities encountered by women entrepreneurs within specific geographical contexts. The study reveals that women entrepreneurs are not given the conditions or resources in which to thrive, due to structural inequalities (e.g., lack of access to devices, lack of post-training support) and social inequalities (e.g., caring responsibilities, economic access to training and gender stereotypes). Practical ways that targeted social policy interventions might respond to such inequalities are proposed, such as providing hardware and internet access, with specific attention given to those in rural areas and low incomes. Such practical solutions highlight that the use of social policy initiatives and interventions to support women entrepreneurs are very much in their infancy. Transformative policies containing clear targets, policy commitments and consultation mechanisms currently lacking will need to be developed and implemented.

Gender and social policy

Gendered inquiry of entrepreneurial policy is a surprising omission from tourism research (Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2020). This omission is troubling for two reasons. First, promotion of tourism entrepreneurship is key to many contemporary neoliberal policy frameworks, with such promotion often unquestionably reemphasising prevailing and narrowly defined assumptions relating to the potentials of entrepreneurship to empower women. And second, it is troubling that inclusive policies are rarely actually evaluated for their effectiveness in terms of equality given that they are consistently called for within the conclusion sections of tourism entrepreneurship papers. There is thus a need for greater critical engagement with the creation, implementation, and effectiveness of policy and governance in relation to the gendered dimensions of tourism entrepreneurship.

Recent studies that have taken focus with gender and social policy in the context of tourism include Tucker’s (Citation2022) critical examination of the gendered nature of sustainability in the Cappadocia region in Turkey, where focus is with the significant but oft contradictory effects of national level political, economic, and social policy reforms on social change and quest for sustainability at the local level. Relatedly, Baum et al. (Citation2016) thematic review noted the limited effects and/or failure of policies to bring about change in the sector, especially in relation to workforce considerations and gender related issues. This is broadly due to continuous underlying societal and cultural expectations on the role of women. Tucker’s (Citation2022) and Baum et al. (Citation2016) research in this area highlight the limitations in well-established top-down approaches in understanding the gendered nature of sustainability in relation to women’s empowerment and equality/equity, workforce considerations and underlying societal and cultural expectations on the role of women. There work thus unites in highlighting the need for greater recognition of the ways policies are encountered through the entrepreneurial journey at the grassroots level.

A set of articles in this special issue have, in response, sought to turn focus to the voices of women entrepreneurs and the ways that governance and policy play out through the local scale. For example, both Ditta-Apichai et al.’s (Citation2023) and Johnson and Mehta (Citation2022) contributions to the special issue examine the ways through which digital spaces offer women entrepreneurs opportunity to create bottom-up networks, despite gendered structural inequalities embedded within policy and governance. Johnson and Mehta (Citation2022) contribution to the special issue uses Ostrom’s (Citation1990) institutional analysis and development framework to analyse 27 interviews with women entrepreneur members of a partnership between Airbnb and Self-Employed Women’s Association in India. The authors outline the core components of a physical-digital collaboration model for women’s tourism entrepreneurship that aims to facilitate spaces of collaboration. In doing so, their study seeks to deconstruct policy and governance conceptualisations of digital platforms as being solely geared towards market-based dynamics, such as individual goals of productivity and competition.

Whilst Ditta-Apichai et al. (Citation2023) examine the use of Facebook by Thai women entrepreneurs through a netnographic approach, illustrating how the women entrepreneurs appropriated Facebook in innovative ways to create supportive communities that fostered entrepreneurial activities. Through this discussion, it is suggested that women entrepreneurs are not the helpless and passive subjects’ policy makers tend to portray them as, with women entrepreneurs requiring more than one-way training and mentoring schemes that are often the central focus of policy support. These articles seek to rectify the invisibility, or at best peripheral positioning, of women entrepreneurs within policy and governance spaces, and build on existing literature that complicates constructed divisions between domestic, economic, and political domains (Hillenkamp & Lucas dos Santos, Citation2019).

Both articles also explore how digital space is in some ways distinct from specific place-based contexts. This creates a perception for some that there is a difference in their gendered positioning, specifically in relation to women’s status as entrepreneurs and claims to entrepreneurship (Marlow & McAdam, Citation2015). At the same time, however, both papers remain alert to the ways offline inequalities continue to be (re)produced in the online environment (Dy et al., Citation2016; Marlow & McAdam, Citation2015), as well as recognition that digital spaces produce their own gendered inequalities. For example, women are less likely to own a smartphone and have access to the internet, when compared to men – reducing the ability of women entrepreneurs to engage with digital space to the same extent as men entrepreneurs (Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development, 2018).

Moving beyond the digital space, yet remaining focused with exploring policy encounters at the grassroots level, Santafe-Troncoso and Tanguila-Andy (Citation2023) article in the special issue uncovers how indigenous women in the Amazonia region of Ecuador have long remained invisible in the regional governance of tourism. This invisibility is attributed to the lack of consideration of gender, age and ethnicity within tourism policy and governance. Nevertheless, the women participants have mobilised themselves towards more visible and influential roles through the development of associative and community led platforms; ultimately leading to positive changes in relation to sustainability and justice outside of formal policy discourse and practice. Similarly bringing attention to the voices of women entrepreneurs at the grassroots level, Lindvert et al.’s (Citation2022) contribution to this special issue examines how women-owned businesses in Nazareth, Israel have served as central to the informal, bottom-up effort to revitalise the city’s historic district. They detail how women entrepreneurs were in a unique position to develop local businesses, given their association with traditional handicraft and venues that offer “authentic” and in demand touristic services. Such successes are contrasted with the failures of previous top-down policies within Nazareth, which tended to primarily focus on the cosmetic aspects of the historic district. Lindvert et al.’s (Citation2022) argue that policy needs to remain rooted in community-based approaches, and caution against research contributions that promote universalised policy implications, rather than locally grounded, context specific approaches.

The articles in this special issue are not the first to identify the lack of gender aware or gender transformative social policies and actions in national tourism policies. Most tourism policies and strategies have been found to be gender unequal, blind, or neutral and at best gender aware and responsive instead of being gender transformative (UNWTO, Citation2023). As Ferguson and Alarcón (Citation2015) note, this situation is mainly due to consideration of gender as an add-on and isolated component rather than integral to tourism policy development. Moreover, Je et al. (Citation2022) systematic literature review notes the challenges faced by organisations in engaging with gender research within organisations and effectively translating research findings into implementable organisational policies and strategies with leadership buy-in. For example, Je et al. (Citation2022) identified that whilst several organisations had successfully integrated gender equality best practice into organisational policy, associated actions and measurable progress was lacking given the absence of regulation by either governments or leading inter-governmental organisations. Quintana-García et al. (Citation2018) observed that social change can only be effectively realised if tourism organisations introduce gender aware and transformative positive discrimination, inclusion and diversity policies and programmes, which actively place women in top management teams enabling their voices and opinions to be heard and considered in formulating and translating policies into actionable programmes. In practice this is a challenging task; manager hiring beliefs regarding women are highly influential – with beliefs that position women as less hard working, for example, inhibiting gender equality/equity progress despite the introduction of gender aware organisational policies (Elhoushy et al., Citation2023). Attending to the voices of entrepreneurs at the grassroots level, as the articles in this special issue have sought to do, thus remains imperative to identifying the ways through which considerations of gender might be more effectively embedded within policy and governance practices.

Social policy and entrepreneurship

The final set of articles in our special issue take specific focus with policy, and the ways through which entrepreneurs are enabled or disenabled through policy and governance structures. There is limited research in this area, although there are some notable exceptions. Walmsley (Citation2018), for example, analyses the intricacies and dangers inherent in developing tourism entrepreneurship policies. Using the case of South Africa, Walmsley (Citation2018) shares insight into how social and economic motivations are the main drivers for the formulation of policies and initiatives to foster job creation through stimulating tourism entrepreneurship and supporting small businesses. In taking focus with tourism social entrepreneurship, Dredge (Citation2017) highlights the important role of governments in creating enabling institutional environments, and importantly designing supportive policies, to promote tourism that is inclusive and sustainable. Briar-Lawson et al.’s (Citation2020) edited collection on “Social Entrepreneurship and Enterprises in Economic and Social Development”, further offers a theoretical perspective around social entrepreneurship that illustrates how enterprises can embed social and economic development missions in their strategy and operational activities. They argue that the pursuit of a dual-mission that strives to achieve both financial sustainability and social good are especially path-breaking approaches to delivering the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Crucially, however, the chapters in Briar-Lawson et al. (Citation2020) edited collection bring caution to the extent to which fostering social enterprises is the panacea to addressing human needs when government investments are required in social welfare, social protections, and ecosystem supports.

Wilson and Chambers (Citation2023) introduce further caution to the potential of entrepreneurship to address sustainable development, in arguing that research has not fully exposed and dismantled historic and structural inequalities, human right abuses, and injustices encountered within the tourism industry. Kalisch and Cole (Citation2022) have similar concerns in their reminder that tourism is part of the capitalist system, and whilst patriarchy, colonialism and capitalism have all be explored in tourism – attention is needed in the ways these areas intersect to produce structures of oppression and injustice within tourism encounters. For this reason, whilst research in this area aspires to a different, empowered, loving, and more equitable and inclusive tourism sector, “how” social policy leads to gender equality in tourism entrepreneurship is not really known, despite consistent calls that social policy, as well as socially inclusive approaches more broadly, is key. Overall, this literature is valuable in noting the importance of an enabling institutional environment and favourable tourism policies in promoting diverse performances of tourism entrepreneurship, however, there remains a need for critical analysis concerning the ways gendered structural inequalities are embedded within, and reproduced through, specific policies.

Seeking to rectify this gap, Williams et al.’s (Citation2023) contribution to the special issue engages with a critical embodied perspective to interrogate the ways gendered assumptions within Welsh policy reproduce and sustain particular entrepreneurial bodies. In particular, the paper identifies how the masculine entrepreneurial body is reproduced and unchallenged within policy through the construction of entrepreneurs as agentic, active, and able, and capable of being trained, controlled, and regulated. This is despite the ever-growing literature that seeks to challenge western-framed assumptions and bring attention to modes of bodily difference. Freund et al.’s (Citation2023) contribution to this special issue reveals the consequences in rendering gender invisible within tourism policy and governance. Examining the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona through semi-structured interviews with women entrepreneurs and key figures, the data reveals how implicit biases support the performance and success of masculine entrepreneurial performance – and as a result, higher expectations were found to be placed on women entrepreneurs. This was particularly evident in areas where women were perceived as weaker; for example, in securing formal finance.

Figueroa-Domecq et al.’s (Citation2022) article within the special issue similarly seeks to deconstruct the ways that gendered inequalities are embedded within, and reproduced through, policy. The authors analysed 996 applications retrieved from Spain’s Emprendetur funding scheme (2012–2016), through a feminist political economy approach. The analysis identified that women were not only less likely to apply to the funding scheme but were also less successful when they did apply. The reason for this being the prioritisation of innovation within the funding call – an area of tourism entrepreneurship more likely to attract men, whilst at the same time, men led businesses are more likely to be perceived as innovative. It is argued that the persistent prioritisation of innovation ensures gendered inequalities become reproduced, rather than reduced, through policy. The authors conclude by arguing that gendered entrepreneurial outcomes will prevail within the tourism industry until greater attention is given to the broader structural barriers embedded and reproduced through policy.

Tying the knot and setting a research agenda

In this section, we outline the key contributions of the special issue, whilst setting an agenda for further research. In reviewing the papers, two important currents emerged that facilitate a link to all the papers, and we suggest requiring more attention in future research – ”physical and digital (phygital) structural inequalities” and “gendered entrepreneurial resilience”. Before moving to discuss each in turn, it is useful to first explain how we are engaging with the term “phygital”. The term “phygital” is gaining traction within entrepreneurship literature, to capture the continuum of physical/offline and digital/online spaces arising from the increasing prominence of digital technologies in everyday life (Parth et al., Citation2023). As discussed above, various online spaces may be viewed by entrepreneurs as somewhat separate from the inequalities produced offline, whilst, at the same time, the gendered inequalities experienced by entrepreneurs in physical spaces continue to be reproduced in the online environment (Dy et al., Citation2016). Thus, we use phygital to recognise both the consistent and different ways that physical spaces and virtual spaces (the internet) can be gender biased contexts that (re)produce institutionalised prejudices regarding assessments of the legitimacy of (women) entrepreneurs and their businesses.

Inequalities across the phygital spectrum

The collection of articles in this special issue contribute to the literature on the causes and consequences of inequalities for entrepreneurs that manifests across the phygital spectrum. In constructing meaningful social policy, it is crucial to understand such inequalities and how they unfold in specific spatial contexts both online and offline. More specifically, the special issue article by Williams et al. (Citation2023) underscores the need for further research to understand how gendered bodies are constructed through entrepreneurship policy in place specific contexts. A view reflected in the special issue article by Freund et al. (Citation2023), which likewise points to the need for research that explores how the gendered body is (re)produced within entrepreneurial ecosystems – in recognition that the prevailing association of entrepreneurship as masculine affects the legitimacy of women entrepreneurs (Dy et al., Citation2016; Marlow & McAdam, Citation2015). Moreover, recognition of how pandemics and other crises exacerbate economic and gender inequalities and widens gender gaps in unemployment (cf. Brzezinski, Citation2021; Furceri et al., Citation2020) across different sectors including tourism (c.f. Novelli et al., Citation2018; Seyfi et al., Citation2022) is a crucial consideration when formulating social policy. Given the likelihood of future pandemics and taking into consideration the global nature, severity, and duration of the Covid 19 pandemic, future research should investigate the extent to which long-running pandemics impact tourism entrepreneurship, and the ways through which such impacts unevenly disrupt gendered entrepreneurial performances within place-based contexts.

Furthermore, the special issue article by Khoo et al. (Citation2023) begins to signal what new research may be needed to better understand the digital disparities among entrepreneurs, taking gender into consideration, alongside age, social class, culture, and urban-rural gaps. They highlight how gender is a key variable in terms of accessibility to both online and physical spaces – a particular concern for tourism entrepreneurs, given the industry’s reliance on reaching markets in various geographical settings. As online access and competency becomes increasingly imperative to entrepreneurial performance, innovation, and sustainability (George et al., Citation2021), such spatial divides need to be accounted for in social policy.

Further insights are also required regarding how gendered inequalities are reproduced through a lack of quality data. Three articles in this special issue contribute to our understanding of the consequences of a lack of high-quality data in sustaining gender inequality in tourism entrepreneurship. The special issue article by Lin et al. (Citation2022), for example, suggests that financing decision variables are binary when considering well respected datasets, such as Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. To enhance the potential of social policy, they call on tourism researchers to produce open access, digitised datasets to enhance accessibility, as well as prioritise more recent datasets, and complement binary variables with qualitative business analyses of cultural influences. Along similar lines, Figueroa-Domecq et al. (Citation2022) assessment of “successful” business plans submitted to funding schemes shed light on the need for more longitudinal studies. This is a crucial concern given the ways data is used to make decisions about what women entrepreneurs need and how those needs should be provided. As such, Lindvert et al. (Citation2022) in this special issue, call for a more systematic approach to research and dissemination, to more effectively articulate the initiatives that have successfully supported women entrepreneurs in tourism destinations and available cost-effective opportunities where their skills can be constantly developed. This could be through creating open access repositories, short off and online training courses, seminars, webinars, and other learning resources as is currently done by the UNWTO and its partners (UNWTO, n.d.). Shifting to high quality, open access, digital datasets, that facilitate both longitudinal insights and place specific nuances, is thus needed to enhance not only the capacity and performance of the women entrepreneurs but also the rigour and applicability of research findings for social policy.

Beyond bouncing back: entrepreneurial resilience and sustainable business models

As discussed above, much of the data reported by the authors of the articles in this special issue were collected either before or during the Covid 19 pandemic. Thus, the findings provide valuable insights into the concepts of entrepreneurial resilience and the sustainability of entrepreneurial business models. For instance, three special issue articles taken together, uncover strategies used by women entrepreneurs to respond to Covid 19 (Maliva et al., Citation2023), including using their experiences of responding to previous environmental disasters (Filimonau et al., Citation2022). Through this research, this special issue contributes to the entrepreneurship literature discussing how tourism entrepreneurs build their entrepreneurial resilience (Welter et al., Citation2018). Following Welter et al. (Citation2018) and Kimbu and Ngoasong (Citation2016), entrepreneurial resilience is used here to refer to the capacity (mindset, attitude, behaviours, skills, and resourcefulness) of entrepreneurs to respond to the vulnerabilities associated with being exposed to a crisis.

All the articles in this special issue point to inefficiencies in existing institutional policies relating to the gendered dimensions of tourism entrepreneurship within the context of a “post” pandemic tourism industry. As the special issue article by Maliva et al. (Citation2023) identified, women entrepreneurs did not simply “bounce back” or “bounce forward”. Rather, instead of aiming to return to the old ways of working (bouncing back), women entrepreneurs opted for transformation (bouncing forward), and a range of other variations that were not captured by existing policy. The suggestions for change that emerged from the papers in this special issue suggest that the heterogenous ways women entrepreneurs respond to pandemics and perform resilience can facilitate more productive insights and enhance support structures that will likely be required when dealing with similar crises in future. In terms of productive insights, this special issue has unpacked diverse strategies that women entrepreneurs deploy to bounce forward, such as actively seeking support and finding ways to respond to crises (Maliva et al., Citation2023) and developing sustainable business models that enable them to overcome day-to-day business challenges (Kutlu & Ngoasong, Citation2023).

Conclusion

This special issue was motivated by the crucial role social policy undertakes in (de)constructing gendered barriers to tourism entrepreneurship, alongside the identified marginalised positioning of social policy within the tourism entrepreneurship literature. As co-editors, we were also motivated by the need to create networks and pathways for knowledge exchange between stakeholders that consolidate existing, and drive new, interdisciplinary research in gender, entrepreneurship, and social policy. Though policy discourse identifies the potential of entrepreneurship to lead to equality/equity and suggests that increasing gender awareness can improve social policy, research that intersects these three areas has, to date, been fragmented and scattered.

The collection of articles in this special issue offers insights into the ways that entrepreneurs are directly contributing to economic growth and social prosperity, where their businesses create jobs and even bring life back to historic sites. The majority of businesses studied in the articles in this special issue are mainly micro, small and medium sized businesses (MSMEs) that tend not to employ many people – in consequence such businesses are less favoured in policy contexts, where there is rather a preference to support forms of entrepreneurship perceived to generate high economic returns and high levels of employment. However, the overall impact in bringing attention to these MSMEs is the creation of previously unrealized opportunities for meaningful work in the visitor economy, even in the face of crises. Whilst in centring here with social policy, we can begin to understand their critical role and contribution to social and economic growth within communities, and the need for governments to make them (and their owners) more resilient through the adoption and targeted implementation of gender transformative (instead of gender neutral and gender aware) policies and governance structures. Such interventions will contribute to speed up the (de)construction of extant gendered inequalities embedded within tourism entrepreneurship, by removing structural barriers, creating more opportunities for inclusive and sustainable business growth and empowerment of these marginalised populations.

At a micro and meso level, the collection of articles in this special issue all point to the importance of developing and effectively implementing social policies that provide entrepreneurs with optimum conditions and resources to thrive in the face of structural inequalities. An example is to enable digital competencies for business visibility, self-empowerment, and financial independence. To address the digital divide, the design and delivery of gender-inclusive digital competency training for women entrepreneurs in tourism is crucial – yet as the special issues articles have hoped to highlight, what is perhaps more imperative at the present time is the ongoing evaluation and monitoring of such programmes to ensure their effectiveness for entrepreneurs of all genders within specific place-based contexts (e.g., Johnson & Mehta, Citation2022; Kimbu et al., Citation2019).

At a macro level, there are implications from this special issue regarding the focus taken within the economic and social policies of governments. Rather than focus on increasing the number of women entrepreneurs in the tourism sector, policy makers must rather listen to the voices of entrepreneurs of all genders. The collection of articles in this special issue suggests the need for a gender lens approach within social policy, that recognises place-based specificities to avoid a repeat of well-established top-down approaches. A gender lens approach constitutes a concrete solution for change because it emphasises active policies that address gendered challenges that women face in three areas: (i) direct investments in women-owned businesses; (ii) incentivised access to products and services for women; and (iii) implementing measures to enhance representation and progression of women at different career levels (Ngoasong, Citation2023). Examples of specific solutions offered in this special issue include increasing the transparency of financing processes for women entrepreneurs (Lin et al., Citation2022) and developing women’s agency to respond, rather than give up on tourism entrepreneurship (Maliva et al., Citation2023). Across the papers in this special issue, it is also clear that policies should actively address the public infrastructure needs that are relevant to women, such as funded nursery schools, sanitary facilities, safe public transportation and internet and reproductive health support.

In summary, in this special issue, we collected and organized conceptually rich and empirically robust investigations into the multiple points of interaction among gender, entrepreneurship and social policy. This collection is an important step in integrating such research and further exploring their dynamic interaction in different tourism contexts and destinations. Our collection of studies seeks to inspire colleagues to join the community of researchers to improve our understanding of sustainable tourism at this intersection. Furthermore, the articles in this special issue examine gender as a binary construct (man/woman), with limited consideration of gender as socially constructed with different categories and the consequent implications of this for tourism entrepreneurship and social policy. As such there remains significant research that is yet to be undertaken in this area. We hope that the future directions we have proposed will serve as useful starters for interested researchers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2012). Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism, and entrepreneurship: Advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization, 19(5), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508412448695

- Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2019). Exploring the false promise of entrepreneurship through a postfeminist critique of the enterprise policy discourse in Sweden and the UK. Human Relations, 74(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719848480

- Avnimelech, G., & Rechter, E. (2023). How and why accelerators enhance female entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 52(2), 104669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104669

- Bakas, F. (2017). Community resilience through entrepreneurship: The role of gender. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 11(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-01-2015-0008

- Bakas, F. (2018). ‘Crafting an entrance’: gender’s role in gaining and maintaining access in tourism ethnography and knowledge creation. In H. Andrews, J. Takamitsu, & Dixon, L. (Eds.), Tourism ethnographies: Ethics, methods, application and reflexivity. Routledge.

- Baum, T., Cheung, C., Kong, H., Kralj, A., Mooney, S., Nguyễn Thị Thanh, H., Ramachandran, S., Dropulić Ružić, M., & Siow, M. (2016). Sustainability and the tourism and hospitality workforce: A thematic analysis. Sustainability, 8(8), 809–821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080809

- Briar-Lawson, K., Miesing, P., & Ramos, B. M. (2020). Social entrepreneurship and enterprises in economic and social development. University Press.

- Bruton, G., Sutter, C., & Lenz, A.-K. (2021). Economic inequality – is entrepreneurship the cause or the solution? A review and research agenda for emerging economies. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(3), 106095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106095

- Brzezinski, M. (2021). The impact of past pandemics on economic and gender inequalities. Economics & Human Biology, 43, 101039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101039

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2003). ‘Woman’ as the subject of feminism. In A. Cahill & J. Hansen (Eds.), Continental feminism reader (pp. 29–33). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Carr, A., Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2016). Indigenous peoples and tourism: The challenges and opportunities for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8–9), 1067–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1206112

- Cole, S., & Gympaki, M. (2021). Gender, tourism, and resilience: Building forward better on small islands. Geographical Sciences, 76(2), 87–105.

- de Jong, A. (2017). Unpacking Pride’s commodification through the encounter. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.01.010

- Ditta-Apichai, M., Gretzel, U., & Kattiyapornpong, U. (2023). Platform empowerment: Facebook’s role in facilitating female micro-entrepreneurship in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2215479

- Dredge, D. (2017). Institutional and policy support for tourism social entrepreneurship. In P. Sheldon, & R. Daniele (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship and tourism. Tourism on the verge. Springer.

- Dy, A. M., Marlow, S., & Martin, L. (2016). A web of opportunity or the same old story? Women digital entrepreneurs and intersectionality theory. Human Relations, 70(3), 286–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716650730

- Eger, C., Munar, A. M., & Hsu, C. (2022). Gender and tourism sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1459–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1963975

- Elam, A. B. (2008). Gender and entrepreneurship: A multilevel theory and analysis. Edward Elgar.

- Elhoushy, S., El-Said, O., Smith, M., & Dar, H. (2023). Gender equality: Caught between policy reforms and manager beliefs. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2218067

- Ferguson, L., & Alarcón, D. M. (2015). Gender and sustainable tourism: Reflections on theory and practice. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.957208

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., de Jong, A., Kimbu, A. N., & Williams, A. M. (2022). Financing tourism entrepreneurship: A gender perspective on the reproduction of inequalities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2130338

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Gender, tourism, and entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102980

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: A gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Pritchard, A., Segovia-Pérez, M., Morgan, N., & Villacé-Molinero, T. (2015). Tourism gender research: A critical accounting. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.001

- Filimonau, V., Matyakubov, U., Matniyozov, M., Shaken, A., & Mika, M. (2022). Women entrepreneurs in tourism in a time of a life event crisis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2091142

- Freund, D., García, I. R., Boluk, K. A., Canut-Cascalló, M., & López-Planas, M. (2023). Exploring the gendered tourism entrepreneurial ecosystem in Barcelona and responses required: A feminist ethic of care. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2207780

- Furceri, D., Loungani, P., Ostry, J. D., & Pizzuto, P. (2020). Will Covid-19 affect inequality? Evidence from past pandemics. Covid Economics, 12, 138–157.

- George, G., Merrill, R. K., & Schillebeeckx, S. J. D. (2021). Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 999–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719899425

- Guzman, J., & Kacperczyk, A. O. (2019). Gender gap in entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 48(7), 1666–1680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.03.012

- Henry, C., Foss, L., & Ahl, H. (2015). Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614549779

- Hillenkamp, I., & Lucas dos Santos, L. (2019). The domestic domain within a post-colonial, feminist reading of social enterprise: Towards a substantive gender-based concept of solidarity enterprise. In P. Eynaud, J. Laville, L. dos Santos, S. Banerjee, F. Avelino, & L. Hulgård, (Eds.), Theory of social enterprise and pluralism: Social movements, solidarity economy, and global south. Routledge.

- Je, J. S., Khoo, C., & Yang, E. C. L. (2022). Gender issues in tourism organisations: Insights from a two-phased pragmatic systematic literature review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1658–1681. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831000

- John, A., Coetsee, J., & Flood, P. C. (2022). Understanding the mechanisms of sustainable capitalism: The 4S model. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(S1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12495

- Johnson, A.-G., & Mehta, B. (2022). Fostering the inclusion of women as entrepreneurs in the sharing economy through collaboration: A commons approach using the institutional analysis and development framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2091582

- Kalisch, A., & Cole, S. (2022). Gender justice in global tourism: Exploring tourism transformation through the lens of feminist alternative economics. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(12), 2698–2715. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2108819

- Kearins, K., & Schaefer, K. (2017). Women, entrepreneurs, and sustainability. In C. Henry, T. Nelson, & K. Lewis, (Eds.), The Routledge companion to global female entrepreneurship. Routledge.

- Khoo, C., Yang, E. C. L., Tan, R. Y. Y., Alonso-Vazquez, M., Ricaurte-Quijano, C., Pécot, M., & Barahona-Canales, D. (2023). Opportunities and challenges of digital competencies for women tourism entrepreneurs in Latin America: A gendered perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2189622

- Kimbu, A. N., De Jong, A., Adam, I., Ribeiro, M. A., Afenyo-Agbe, E., Adeola, O., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (2021). Recontextualising gender in entrepreneurial leadership. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103176 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103176

- Kimbu, A. N., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2016). Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

- Kimbu, N. A., Adam, I., Dayour, F., & de Jong, A. (2023). COVID-19-induced redundancy and socio-psychological well-being of tourism employees: Implications for organizational recovery in a resource-scarce context. Journal of Travel Research, 62(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211054571

- Kimbu, A. N., Ngoasong, M. Z., Adeola, O., & Afenyo-Agbe, E. (2019). Collaborative Networks for sustainable human capital management in women’s tourism entrepreneurship: The role of tourism policy. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1556329

- Kutlu, G., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2023). A framework for gender influences on sustainable business models in women’s tourism entrepreneurship: Doing and re-doing gender. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2201878

- Lin, M. S., Jung, I. N., & Sharma, A. (2022). The impact of culture on small tourism businesses’ access to finance: The moderating role of gender inequality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2130337

- Lindvert, M., Laven, D., & Gelbman, A. (2022). Exploring the role of women entrepreneurs in revitalizing historic Nazareth. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2145291

- Maliva, N., Anderson, W., Buchmann, A., & Dashper, K. (2023). Risky business? Women’s entrepreneurial responses to crisis in the tourism industry in Tanzania. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2186827

- Marlow, S., & McAdam, M. (2015). Incubation or induction? Gendered identity work in the context of technology business incubation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 791–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12062

- Ngoasong, M. Z. (2023). Women’s entrepreneurial journeys in sub-Saharan Africa. Edward Edgar.

- Ngoasong, M. Z., & Kimbu, A. N. (2019). Why hurry? The slow process of high growth in women-owned businesses in a resource-scarce context. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12493

- Novelli, M., Gussing Burgess, L., Jones, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). No Ebola…still doomed’ – The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). Bridging the digital gender divide: Include, upskill, innovate. Accessed: 02/11/2023 from https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Parth, S., Bathini, D. R., & Kandathil, G. (2023). Actions in phygital space: Work solidarity and collective action among app-based cab drivers in India. New Technology, Work and Employment, 38(2), 206–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12223

- Quintana-García, C., Marchante-Lara, M., & Benavides-Chicón, G. C. (2018). Social responsibility and total quality in the hospitality industry: Does gender matter? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(5), 722–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1401631

- Ribeiro, A. M., Adam, I., Kimbu, A. N., Afenyo-Agbe, E., Adeola, O., Figueroa-Domecq, C., & de Jong, A. (2021). Women entrepreneurship orientation, networks, and firm performance in the tourism industry in resource-scarce contexts. Tourism Management, 86, 104343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104343

- Rogerson, C. M., & Baum, T. (2020). COVID-19 and African tourism research agendas. Development Southern Africa, 37(5), 727–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1818551

- Sajjad, M., Kaleem, N., Chani, M. I., & Ahmed, M. (2020). Worldwide role of women entrepreneurs in economic development. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-06-2019-0041

- Santafe-Troncoso, V., & Tanguila-Andy, A. (2023). Indigenous women’s approaches to tourism planning: Lessons from Ecuador. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2247580

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., & Vo-Thanh, T. (2022). The gendered effects of statecraft on women in tourism: Economic sanctions, women’s disempowerment, and sustainability? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1736–1753. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1850749

- Thébaud, S. (2015). Business as plan B: Institutional foundations of gender inequality in entrepreneurship across 24 industrialized countries. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(4), 671–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839215591627

- Tucker, H. (2022). Gendering sustainability’s contradictions: Between change and continuity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1500–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1839902

- UNWTO. (2017). Discussion paper on the occasion of the international year of sustainable tourism for development 2017. http://www.tourism4development2017.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/070417_iy2017-discussion-paper.pdf.

- UNWTO. (2020). AlUla framework for inclusive community development through tourism. United Nations World Tourism Organisation.

- UNWTO. (2021). UNWTO inclusive recovery guide – sociocultural impacts of Covid-19, issue 3: women in tourism, UNWTO, Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284422616

- UNWTO. (2023). Tourism recovery tracker. United Nations World Tourism Organisation. https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/unwto-tourism-recovery-tracker (accessed October 10, 2023).

- UNWTO. (n.d). UNWTO academy: Tourism human capital development. https://www.unwto.org/UNWTO-academy.

- Walmsley, A. (2018). Entrepreneurship in tourism. Routledge.

- Welter, F., Xheneti, M., & Smallbone, D. (2018). Entrepreneurial resourcefulness in unstable institutional contexts: The example of European Union borderlands. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 23–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1274

- Williams, H. C., Pritchard, K., Miller, M. C., & Doran, A. (2023). Mapping embodiment across the nexus of gender, tourism, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2216400

- Wilson, E., & Chambers, C. (2023). A research agenda for gender and tourism. Edward Elgar.

- World Tourism Organization. (2023). Snapshot of gender equality and women’s empowerment in national tourism strategies. UNWTO.

- Young, I. M. (1990). Throwing like a girl: And other essays in feminist philosophy and social theory. Indiana University Press.

- Zhang, C. X., Kimbu, N. A., Lin, P., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2020). Guanxi influences on women intrapreneurship. Tourism Management, 81, 104137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104137