Abstract

Indigenous peoples have unique ontologies and worldviews that stem from their continuing connection with nature and the spiritual world that altogether shape their cultural practices including their approach to collaborating with stakeholders in Indigenous tourism initiatives. By applying an Indigenous methodology, this study ethnographically explores how Indigenous Newars’ traditional collaborative practices inherent in their Guthi system contribute to Indigenous tourism development. The study reveals that Indigenous Newars’ ontology of relationality seeps into their community’s cultural and economic practices to create a community synergy based on unilateral acts of reciprocity. This constructive collaboration cultivates a collective consciousness within Guthi, bolstering Newars’ social capital and facilitating grassroots sustainable tourism development. Moreover, the Guthi-based collaborative practices empower Newars to synthesise their rich historical legacy with emerging tourism dynamics to foster sustainable development and cultural revitalisation. Finally, this study calls for a change in basic assumptions in the existing approach to Indigenous tourism development, one that rejects the lingering colonial power dynamics to embrace and respect Indigenous Newars’ ontologies and traditional knowledges.

Introduction

Some Indigenous peoples believe they are the guests, not masters of the earth (Narvaez et al. (Citation2019), valuing a profound connection with nature through historical and future legacies (Waddock, Citation2019). For instance, the Kānakas, an Indigenous community of Hawaii, identify the ‘land as an ancestor’ (Williams & Gonzalez, Citation2017, p. 675), while Micronesians believe that ‘ties to land’ are established by bloodline (Stumpf & Cheshire, Citation2019, p. 965). It is through a deep sense of guardianship and connection with the natural and spiritual realms that Indigenous peoples’ worldviews influence their values, incorporating Indigenous principles of care, respect, reciprocity and mutual well-being. In other words, Indigenous ontologies influence their behaviour and knowledge systems (Foucault, Citation1970). To Gudynas (Citation2011), these worldviews align with ‘buen vivir,’ a Colombian philosophy of living in harmony with nature that emphasises communal well-being and sustainable practices, which is an epistemic position shared by numerous Indigenous communities across the globe (Selibas, Citation2021). These Indigenous worldviews stand in sharp contrast to the underpinning assumptions of the prevalent neo-liberal, market-driven development models, as they promote a more holistic understanding of the relationships among social, cultural and ecological factors (Velasco-Herrejón et al., Citation2022) and the consideration of Indigenous values and practices (Murga, Citation2020). However, operationalising the concept of ‘buen vivir’ remains challenging, as it demands shedding deep-rooted non-Indigenous ideals and adopting a communal approach (Villalba, Citation2013) to initiatives like tourism.

Tourism development arguably serves to empower Indigenous peoples and communities by drawing upon their inherent values and practices (Scheyvens et al., Citation2021), potentially safeguarding tangible and/or intangible Indigenous cultural heritage (Chang et al., Citation2011). While Indigenous peoples and communities in countries like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Iceland (among others) are actively exploring these benefits (McDonagh, Citation2021), communities in developing countries like Nepal struggle to reconcile contemporary approaches to tourism that have been imposed upon and the threat these practices pose to their social identities and traditional knowledge (Khadka, Citation2020). In fact, neo-liberal approaches to Indigenous tourism development, which emphasise profit as a metric of tourism growth and social progress (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2008), serve to exacerbate an already disproportionate distribution of wealth and unequal access to resources in developing countries like Nepal, (Bennike & Nielsen, Citation2023), as well as perpetuate misrepresentation (Phillips et al., Citation2021), rather than solving it (Ruhanen & Whitford, Citation2019). Any departure from traditional Indigenous values can thus undermine both community welfare (Christen, Citation2006) and the sustainability of community initiatives (Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2022). In addition, even though the literature recognises the significance of integrating Indigenous values and practices (Ransfield & Reichenberger, Citation2021) into tourism initiatives, extant research understates the interplay between Indigenous knowledge and values and sustainable tourism development, along with the methodological implications of such interactions.

The above issues raise the following germane question:

How can traditional Indigenous knowledge, value systems, and methodologies facilitate sustainable Indigenous tourism development?

Theoretical approach

Indigenous values and ontologies for sustainable Indigenous tourism

The diversity of Indigenous peoples in the world is reflected in the wide range of their social locations and worldviews. As such, drawing from limited empirical evidence from the works of Ransfield and Reichenberger (Citation2021) and Scheyvens et al. (Citation2021), this study argues for the interrelatedness of Indigenous values with the concept of sustainable tourism development. Providing a general but encompassing view of sustainable Indigenous tourism development nonetheless remains challenging. Scheyvens et al. (Citation2021) argue that Indigenous tourism initiatives in Australia, Fiji and New Zealand are increasingly informed by certain Indigenous values that correspond with sustainable development aspirations. In their comprehensive study of these values, Ransfield and Reichenberger (Citation2021) identify various Māori social values that inform sustainable Indigenous tourism development in New Zealand and posit that Māori social values and approaches to tourism are intricately interwoven. However, the literature on Indigenous values in tourism development initiatives remains scant, which suggests the need for additional studies on the interplay between Indigenous knowledges and values and sustainable tourism development.

Fu et al. (Citation2021) have demonstrated that social values pertaining to Guanxi are an integral component of the decision-making process of several Chinese businesses. Their study also concludes that fostering the integration of local values into economic endeavours can have a transformative impact on the psycho-social empowerment of (Indigenous) peoples (See also Borquist & Bruin, Citation2019). Therefore, consistent with the findings of Lertzman and Vredenburg (Citation2005), this study asserts that sustainable development involving Indigenous peoples should be viewed as a cross-cultural proposition to integrate the values and meanings of disparate cultures, established knowledge of ecosystems, and contemporary practices that emanate from historical knowledge systems or epistemes (Foucault, Citation1970).

Indigenous peoples’ social values shaped by their ontologies or worldviews are integral to Indigenous stories that contain a wealth of place-specific beliefs, rituals and practices. In Foucault’s scholarship of epistemes, the governance of nature is intricately woven into the governance of people (see Hinchliffe & Bingham, Citation2008). Indeed, existing socio-cultural knowledge systems that emerge from these ontologies can provide novel insights into sustainable development within Indigenous communities and beyond (Scheyvens et al., Citation2021). Hunt (Citation2014) vigorously argues that the situatedness and place-specificity of Indigenous knowledges call for the validation of innovative methods of theorising and epistemologies that can account for situated, relational Indigenous knowledge in tourism while remaining engaged with broader theoretical debates. Efforts to promote Indigenous values may stem from awareness of the lack of spirituality in non-Indigenous behaviours (see Stumpf & Cheshire, Citation2019).

Hunt (Citation2014) cautions against the risk of isolating Indigenous knowledges as ‘other,’ rather than engaging these knowledges in broader efforts to actively decolonise epistemologies. It could therefore be argued that an appreciation of the importance of Indigenous values requires acknowledging the ongoing impacts of the historical marginalisation of Indigenous communities and Indigenous knowledge systems. Thus, any attempt to theorise Indigenous value systems requires unravelling the structure of relationships and deconstructing systems of oppression that continue to marginalise Indigenous peoples and their values (Bunten, Citation2010) in tourism development initiatives. This study does just that by embracing and engaging the crucible of knowledge, culture and values of the Indigenous Newar’s Guthi as a theoretical lens through which to examine Indigenous tourism initiatives.

Collaborative Indigenous tourism

Natural, spiritual and cultural resources form the foundation of individual and shared belief systems for many Indigenous peoples (Movono et al., Citation2018; Stoffle et al., Citation2020). These resources do not simply serve economic goals but are also intrinsically linked to the ancestral knowledge that connects Indigenous peoples with their place and country (Stumpf & Cheshire, Citation2019). Ransfield and Reichenberger (Citation2021) presuppose that tourism enables Indigenous peoples to translate their socio-cultural values into an economic paradigm that balances their social values with their economic aspirations. However, this requires Indigenous-centric stakeholder collaboration (Izurieta et al., Citation2021) led and managed by Indigenous peoples (Pubill Ambros & Buzinde, Citation2021) and which encourages Indigenous peoples to engage in cultural re-learning and sharing with other stakeholders (Lonardi et al., Citation2020).

Movono et al. (Citation2018) argue that a community-controlled collective effort at the Indigenous grassroots level in tourism initiatives can foster transformative relationships and empower Indigenous peoples to shape broader societal changes. However, implicit in such a community-based approach is recognition of the Indigenous communities’ strength, expertise, right to self-determination and collective leadership. Undoubtedly, self-determination and collective leadership influence Indigenous peoples’ collective power (Lor et al., Citation2019), which in turn enables them to optimally utilise socio-cultural capital to co-create tourism products and services in cooperation with mainstream society stakeholders (see Yeh et al., Citation2021). Innovation driven by co-creative engagement is rooted in Indigenous cultures and knowledges and has the potential to prevent the adverse effects of cultural commodification (Richards, Citation2011) in Indigenous tourism. Blapp and Mitas (Citation2018) contend that the co-creative and collaborative process empowers Indigenous communities to collectively leverage tourism to uncover, identify and address pertinent underlying concerns. Most signifcantly, co-creation provides the impetus for Indigenous peoples to resolve complex problems requiring complex interventions by creating ‘opportunities to co-create innovative solutions that will in turn benefit’ Indigenous communities (Huneault & Otomo, Citation2022, p. 11).

Although recent studies (Blapp & Mitas, Citation2018; Shrestha & L’Espoir Decosta, Citation2023) acknowledge the significance of co-creative and collaborative community engagement, Taylor (Citation1995) argues that collaboration itself is an idealised and romantic concept, overlooking the complexities resulting from persistent power dynamics (Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2022). Additionally, existing studies (Stumpf & Cheshire, Citation2019) generally adopt resource-based (Zhang et al., Citation2021), capability-based (Cuong, Citation2020; Kim & Kang, Citation2020) or structural (Manaf et al., Citation2018) approaches to community-based tourism initiatives. To Ngo and Pham (Citation2023), a decolonised approach is seldom workable due to the systemic dynamics inherent in the tourism sector. However, community knowledge systems such as the Newars’ Guthi can and should be viewed as a means of acquiring novel insights (Ransfield & Reichenberger, Citation2021; Stumpf & Cheshire, Citation2019) and approaches to sustainable Indigenous tourism development. This study problematises the existing approach to collaborative tourism in the lack of recognition and integration of Indigenous knowledge systems as perpetuating neo-liberal ideals, and subsequently calls for the decolonisation of collaborative Indigenous tourism initiatives.

This study further theorises Indigenous Newars’ collective determination for sustainable tourism development by prioritising and empowering Newari values and beliefs that are based in and perpetuated by their Guthi (i.e., traditional social construct). This provides perhaps the sole means of observing how these communities can foster a form of tourism development that aligns with their cultural and spiritual principles and contributes to their communities’ well-being and the preservation of their cultural heritage for generations to come.

Guthi: crucible of historical and social values and knowledge of Indigenous Newars

The Newars are Indigenous to the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal and possess a rich cultural heritage characterised by distinct traditions, beliefs, language, art and architecture. Their history in the Kathmandu Valley dates back thousands of years and has witnessed the rise and fall of various dynasties and kingdoms in the region. Within the Indigenous Newar communities of Nepal, ‘Guthi’ refers to their traditional socio-economic institution (Tandon, Citation2018). Guthis are community trusts or organisations that manage and govern religious, cultural and social activities. They often own land, temples and other properties and are responsible for conducting religious rituals, organising festivals, supporting various community welfare programs, and maintaining sacred sites.

Decisions within a Guthi are reached in consultation with elders to ensure the historical accuracy of events and activities it organises (Löwdin, Citation1998). A number of Guthi cultural events, such as Machhindranath Jatra (a 1700-year-old cultural procession) and Kartik Nach (a 700-year-old cultural dance), attract both domestic and international tourists. A Guthi’s collaborative approach and social value system not only frame Newars’ behaviour and decisions but also provide historical and contemporary evidence of sustained collaboration and involvement at the grassroots level of Indigenous Newars. Guthi is a social entity that brings together community members to achieve specific cultural and social goals (Tandon, Citation2018) that are tied to Newar socio-cultural values. Guthis are firmly embedded in the daily life of Newar communities and proliferate across the traditional Newari country of Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur (Gellner, Citation1986; Löwdin, Citation1998). As such, any aspirations for a decolonised approach to Indigenous tourism development requires ceding community control to the Newars by acknowledging and integrating their ontologies sustained in their Guthis.

Methods

This study celebrates the Indigenous Newar people of Kathmandu, Nepal by employing Indigenous methodologies to understand their cultural histories and social norms. As part of that approach, participants directly accrued research benefits through participation in and engagement with the study (Drawson et al., Citation2017). Understanding Indigenous lived experiences requires knowing, acknowledging and respecting Indigenous cultural practices and social values, which explains why this ethnographic study not only achieves deep involvement with the Newari culture but also helps understand Indigenous Newars’ knowledges, language, lifeworld existentials, social values, symbolism, stories, and folklore (Chilisa, Citation2012). Importantly, the Indigenous participants in this study were research partners and co-designers who became active participants and co-creators of knowledge (Goodyear-Smith et al., Citation2015). The field study took place at two sites part of the Newar Country.

Study site 1: traditional Newari Khokana village from Lalitpur district

Khokana is one of the historical Newari settlements within the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. This traditional medieval Newari village sits eight kilometres south of Kathmandu (on the outskirts of Patan) (Ghimire, Citation2022). This village is also considered one of the earliest human civilisations in the Kathmandu Valley. The region is widely known for its production of mustard oils using archaic methods within a long-established cooperative manufacturing facility. This cooperative is widely recognised as one of the oldest operational cooperatives in the world (Gautam, Citation2018). The cultural and religious practices of Indigenous Newars from Khokana distinctly set them apart, even among the Newars (Kayastha, Citation2021). Ill-informed government programs and policies, however, are threatening Khokana’s archaeological sites and its tangible and intangible cultural heritages (Apostolopoulou & Pant, Citation2022).

Study site 2: traditional Newari Patan city from Lalitpur district

The second site for this study is Patan, also known as the ‘city of artisans,’ which lies five kilometres Southeast of Kathmandu. This city was founded in the third century by the Kirat Dynasty, and its urban history dates as far back as 2300 years (Lalitpur Metropolitan City, n.d.). This traditional Newar country is home to several Indigenous artisans who still use ancient techniques of artisanship (Nepal Tourism Board, Citationn.d.). Patan also houses iconic buildings of historical and cultural significance (Gellner, Citation1986) and is lively with popular festivals such as Machhindranath Jatra and Kartik Nach (Löwdin, Citation1998). The city also hosts several traditional temples that symbolise the harmonious co-existence of Hinduism and Buddhism, their uniquely interwoven principles and rituals in this region for ages, influencing each other and shaping local practices and beliefs (Gellner, Citation2007). This unique blend of cultures, history and modernism has attracted both domestic and international tourists to Patan.

Data collection method - Infusing Indigenous knowledge and methods

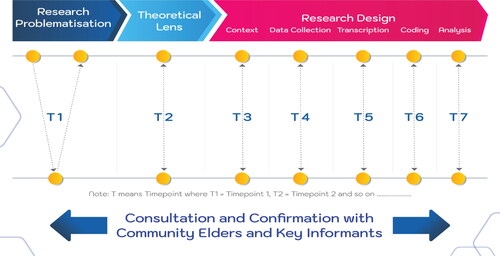

Smith (Citation1999) argues that an Indigenous method should be cognisant of the Indigenous standpoint and reflective of Indigenous values. This study acknowledges that Indigenous peoples’ daily experiences shape their epistemes as expressed in their normative objective of socio-economic development and emanating from the belief that knowledge is relational (S. Wilson, Citation2008). Hence, the methodological approach of this study, as shown in , underscores constant consultation with key community stakeholders since the establishment of initial contact in 2021.

On location from May 2022 to November 2022, the first researcher, who is an Indigenous Newar, consulted with community elders and community leaders at different stages, including the first phase of research problematisation (T1). After consultation with the elder, at T1, the researcher modified the initial question to ensure that the research problem was theoretically and pragmatically relevant to the community. Thereafter, the researcher discussed the theoretical approach that Guthi provides to the study at T2 with the community leader and elders. Approval from the elder and community leader was thus sine qua non to go into the field where the two sites were located next to each other. Once the researcher secured approval and upon reaching the study sites at T3, they finalised the research context in consultation with the community elder. At T4, there were more consultations carried out with elders to ensure that community norms and social values were respected and in line with their Guthi, during data collection. Since the interviews were conducted in Newari or Nepali languages at T5, the transcripts were sent to selected respondents to ensure they agreed with the transcriptions.

At T6, the first researcher revisited the sites to conduct two ‘Khā Lā Bā Lā’ (i.e., Indigenous focus groups) with twelve participants to verify codes and the emergent themes from the analysis of data that was done simultaneously with data collection. Khā Lā Bā Lā holds cultural and social significance as it is a way for Indigenous Newars to come together and build relationships. This process involved ensuring Indigenous community control, self-determination, active involvement and Indigenous voice were present in the research process. Finally, before the finalisation of data visualisation and framework, the major findings were sent to the community elders requesting their permission to share the results with the academic community.

Data were collected from multiple stakeholders who were directly or indirectly engaged in tourism and hospitality activities. This study adopted a purposive sampling technique to identify and approach relevant respondents. Several analytic tools of the grounded theoretical method were pertinent to data collection and analysis, including constant comparison, memo writing, theoretical sampling and theoretical saturation (Charmaz, Citation2014). Data were collected from four sources and included fifty semi-structured interviews, three go-along conversations with community leaders, 175 h of participant observation and a daylong workshop with 30 participants. Data from the semi-structured interviews, participant observation and go-along conversations were coded in situ. The research employed theoretical sampling, a process that involves selecting participants based on emerging theoretical insights or specific ideas that require further clarification. Theoretical sampling helped triangulate the data from interviews and observations with the data from go-along conversations, an approach that is popularly adopted with the ethnographic method (Kusenbach, Citation2003). More data were collected until theoretical saturation was achieved when no new insights emerged from these data (Robinson, Citation2014). Finally, to wrap up the study, a participatory workshop was conducted that embraced design thinking principles (Tunstall, Citation2020) to engage with elders and empower Indigenous voices. shows the number of respondents who participated in the approaches to data collection.

Table 1. Sample size for various approaches to data collection.

Data coding and analysis method

The coding process involved utilising the Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) software NVIVO 12 to analyse and categorise verbatim excerpts from diverse sources of evidence. Charmaz’s Charmaz (Citation2008, Charmaz, Citation2014) principles of constructivist grounded theory (CGT) informed qualitative data coding and analysis. CGT adopts the inductive, comparative, emergent and open-ended approach to data analysis (Charmaz, Citation2014), which makes coding flexible and adaptable and requires rich engagement with the study context to generate theoretical insights (Charmaz, Citation2006).

The research adopted a three staged coding process accompanied by extensive memo-writing. First, open codes, including ‘in-vivo’ codes that were taken verbatim from the data, were generated. Constant comparison helped reduce the initial 1200 open codes to 649. The open codes were compared for similarities and differences in the second step of coding. At that level, 89 focused codes emerged. The focused codes’ properties and dimensions were determined, and comprehensive memos were written. Later, cases were selected regarding their properties, dimensions, or interrelations (Vollstedt & Rezat, Citation2019) around higher level selective codes. The last step was to connect all existing selective codes around one core category or theme (Charmaz, Citation2008). It returns the key selective codes to the data for continuous bottom-up comparisons and interactive comparisons, combined with existing literature, including Guthi’s socio-cultural values and collaborative practices for cultural, economic and social undertakings. In consultation with the community elder, the research team agreed that the following three themes that emerged from the coding process provided insights into and answered the research question that seeks to understand how Indigenous Newars from Nepal draw upon their traditional knowledge systems and community values to facilitate sustainable Indigenous tourism development. These resulting analytic themes are:

Theme 1: Uncovering inherent social values and beliefs of Indigenous Newars

Theme 2: Strengthening social ties to develop collective consciousness through Guthi

Theme 3: Negotiating resource ownership and control through community association

illustrates the example of different levels of codes for the theme ‘Strengthening social ties to develop collective consciousness through Guthi’.

Table 2. Example of coding process of the theme ‘Strengthening social ties to develop collective consciousness through Guthi’.

Findings

Theme 1: uncovering inherent social values and beliefs of Indigenous Newars

Within Newar communities, Guthi is a symbolic representation of socio-cultural values that are further promulgated and expressed through myths, folklore, rituals and cultural practices. To ITS-08, a Maharjan actively engaged in Guthi affairs, any socio-economic actions (i.e., cultural festivals and tourism) taken in pursuing these values have psychological, practical and social consequences for Indigenous Newars. ITS-08 said:

‘[…]it (Guthi) means a lot to me. This is our heritage and pride […] There may come a time when jatras, that we organise through Guthis, come to an end. At that time, people will reminisce about how their forefathers were involved in the processions and festivals […] We celebrate Machhindranath Jatra (an historic festival which gathers a large number of domestic and international tourists) not because it attracts many tourists but because we believe that celebrating this festival will bring rainfall, a bountiful harvest, and a prosperous year. There are several myths surrounding this festival, and continuing this grand festival gives us a sense of pride and motivates us.’

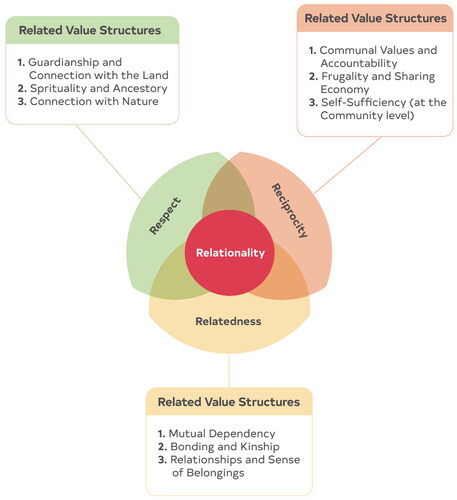

Relationality is reinforced as the central idea that Indigenous peoples are rooted in their relationships to land, spirituality, beliefs and values. Data collected through three-staged interactions with elders of Khokana revealed that the ontology of relationality is central to the three core principles of respect, reciprocity and relatedness inherent in Guthi because Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies are fundamentally about the relationships of beings. Relationality does not simply connect community members but creates a connection with the past and future, and the spiritual and human dimensions of the living entity. Relationality also combines material cultural objects and ancestors’ legacies. Community elders who participated in Khā Lā Bā Lā explain this connection:

‘During jatras and religious festivals, we practice tantric rituals. We chant mantras and sing hymns. As a part of our tantric rituals, these enchanting mantras and hymns symbolise that our physical body is linked to cosmic energy. This integration represents the alignment and harmonisation of all aspects of an individual in the pursuit of moksha…’ (KL-IS-01).

‘Before we plant rice seedlings, we worship the frogs in our farm. Many people do not even know why we follow this ritual. My grandfather once said that when frogs came to our farms, it usually meant the rainy season was about to start. He told me that the frogs would come to our farms, see us planting the rice seedlings and then request the gods to bless us with rain. To show our appreciation, we worship the frogs. (KL-IS-04)’

‘You see, the houses here do not have LALPURJA (i.e., a land ownership document). The way our houses are structured, it is impossible to get one. But the idea here is that we do not own the land. Our ancestors gave this land to us as a “CHINARI” (i.e., keepsake), and that’s what I intend to do as well…’

‘Meadow (i.e., open space), temple and Dabu (i.e., stage) are directly connected with our daily life. Open space is essential for Jatra, yoga, and to dry up cash crops, grains, etc. Temple is our faith, our religion. Dabu is the stage which is the same as the theatre and shows different programmes (including cultural performances for tourists and locals). If we lose our land, our identity is threatened.’

‘Our Guthi used to cultivate bananas and Marihuana. We used to preserve these things because they had many benefits. The seed of Marihuana used to be called “Lufu” and had medicinal functions. We used to mix it with Chaku (i.e., traditional Newari sweetener). The mixture was called Agnikumar and was used as a medicine when children had stomach aches.’

‘Many Jyapu Newars were traditionally farmers. You can see that many of them lost their land and did not have a decent job or a source of income. Jyapu Samaj was established to support them. We developed several plans and programs to empower them and to reinvigorate the sense of brotherhood among the Jyapu Newars.’

‘…At an early age, we see it (i.e., festivals organised by Guthi) as an audience. After several years of closely observing the festivals, the value of the culture is unconsciously learnt by adults. If we start to feel the value, I will be motivated to transfer it to younger generations.’

‘…house chores. We do not wait for someone to manage things at home. It is the same for Guthi and Manka Khala. People do whatever they can. Some help financially, while others volunteer their time. They participate in the cultural procession, cook during Guthi events, learn musical instruments, and maintain Hiti (i.e., water sprouts), Falcha (i.e., resting places) and temples… You may think it is because tourists come to visit us but we have been doing this for several centuries.’

Likewise, Indigenous Newars’ value of frugality and sharing economy underpins the principle of reciprocity. With frugality in their value structure, Indigenous Newars can in fact aim at the optimal use of their resource base for the community’s good. During Khā Lā Bā Lā, the community elder KL-IS-09 remarked:

‘We have always been frugal. After harvesting mustard, mustard seeds are separated from mustard greens. Mustard greens are a popular vegetable in Newari cuisine. Once the mustard seed is pressed using the wooden press that we have in our cooperative, the oil is extracted, and the remains of the seeds that we call pina (also known as mustard cake) are collected. Pina has many uses. In our community, it is popularly used as a fertiliser on the farm or as a substitute for shampoo.’

‘…supporting others by volunteering their time to help them in farms or the construction of their houses. An interesting example is how we traditionally produced mustard oil in our oil cooperative. The cooperative is co-owned by the community members, who take turns to press mustard seeds produced from their farms or procured from the market….’

Theme 2: strengthening social ties to develop collective consciousness through Guthi

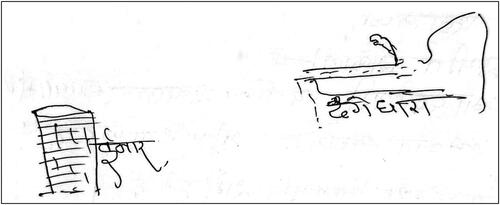

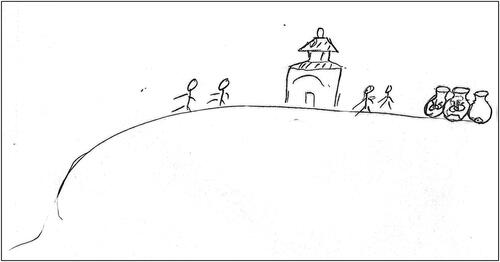

The data suggest that when the ontology of relationality underpins social institutions like Guthi, the latter fosters community synergy and cohesion within Indigenous Newar communities. Consequently, Guthis are unique because they are the repository of the community’s social capital. During the workshop, the researcher asked the elders to identify various elements of social capital within their Guthi that they could leverage for community tourism development (see ). Interestingly, the elders adopted an inward reflection that turned to connections with their own stories and history thus demonstrating stronger trust in community members and community resources rather than their external networks and relationships. They argued that tourism development within their community should first look inwards and focus on community issues, which, according to GB-IS-12, another lifelong member of Guthi and a community elder, can only be achieved by:

Table 3. Social capital identified by Indigenous Newars for tourism development.

‘…working together with my brothers and sisters. We grew up together, we know what this place meant to our ancestors and what story it tells. Only we know the story that we want to tell our children. I do not believe anyone else will understand this. If we should develop tourism in this community, we should write our own story.’

The above verbatim perhaps demonstrates the formation of collective consciousness as a learned process through informal stories and history of the community. Within Newar communities, Guthi can create a sense of ‘wholeness’ as it leaves no one behind and brings together community members owing to its inclusivity, shared objective, well-defined processes and protocols, respect for the community’s way of life, sustainable finances, effective learning mechanisms, and capacity to self-organise. This holistic sense of wholeness is crucial for the formation of collective consciousness, which is the primary mover for collective behaviour and development as ITS-15, a Jyoko Newar revealed:

‘…several Guthis are involved while organising Machhindranath Jatra. Each Guthi has distinct functions that are carried out once the chariot reaches specific locations […] People know what they are supposed to do and who takes over after them. There is an understanding and a sense of duty. Everyone performs their duties without fail ….’

Figure 3. Elders’ conceptualisation (Group C) of the ideal future that can be attained through tourism during workshop.

‘…land is the main cause for the great social structure. Our water resources are depleting because we do not have access to land. The traditional rainwater and groundwater harvesting system that our ancestors developed is destroyed with unplanned urbanisation. Additionally, there is a lack of funds that is important to conserve Guthi, musical instruments and community practices.’

Indigenous Newars’ inherent value structures and ontologies are fundamental to the formation of the community’s social capital, which in turn, shapes tourism innovation and development. This is partly possible because of the fundamental principles of trust and norms of reciprocity of Indigenous Newars, which facilitate active community and exchange relationships. In fact, the data show that the social capital observed in Indigenous Newars’ Guthi is an outcome of their collective consciousness as expressed in their stories and practices. In fact, the community’s inter-generational learning, cultural identity, and awareness of its historical identity create and foster its social capital.

‘Since I was in grade eight, I started learning about metal works that our family pursued for several generations. I always saw my father drawing various designs and bringing them back to life. I started working on this when I was 18 (ITS-39).’

‘…I grew up with this culture. I have seen this since childhood, from listening to stories of my grandparents and participating in different programs. So, Guthi and Patan have a special place in my life. However, people from other cultures or communities may not know the importance of my culture (ITS-01).’

Data also suggest that internal social capital allows community members to identify and leverage relevant knowledge for tourism development. This is particularly evident in Patan, where tourism operates on a hub-and-spoke model. Patan is a tourist hub and relates to several nearby areas such as Khokana. Through continuous interactions with cultural activities, several youngsters across the Newar country not only initiated actions in response to changes in their community but were also given the opportunity by Guthi members to take initiatives to support a cultural revival. The architect ITS-18, who is involved in heritage restoration remarked that:

‘[…] youngsters felt like their culture was dying, so they started a Facebook group and organised programs…’

‘[…] currently many people are away in foreign countries, and many houses are vacant. We are trying to make it a homestay to show our culture to others…’

‘We are trying to save our culture and tradition, but somehow we are not able to do it.…’

Theme 3: negotiating resource ownership and control through community association

Sequential to the role of social capital in developing the collective consciousness of the community is the emergence of the third theme displaying the process by which the Newars ensure control over their resources. Elders and community leaders agreed about the importance of community associations and emphasised the importance of collective sensemaking through Guthis. Indeed, the collective experiences of the community are given interpretive and explanatory meanings through an interactive loop of retrospective and prospective sensemaking. It means that collective sensemaking involves a reflection of Indigenous Newars’ past, present and future along with natural, social and spiritual realms in a knowledge-creating process. Thus, the Indigenous Shakya ITS-10 explained that:

‘First thing is before telling others, we must learn well about our own culture. We need to understand the history and only then disseminate it to others. We have different food that we consume at different events or at different time-period. What I have also seen during Mahotsav (i.e., carnivals), people highlight different cultural identities, such as our rituals, gastronomy and musical instruments. Such events can be exciting in promoting our culture to tourists. But, we need to reflect inwards and understand the meanings behind our practices….’

‘…our ancestors orally conveyed a diversity of tales and historical information to our elders from whom we learn our stories. The origin stories for Khokana, Lakhey (i.e., Newari Mythic Creature), jatras, festivals, and the justifications for these celebrations. These descriptions are our identities, and we seek to conform to them.’

‘…I have noticed that people have their own understanding of the festivals and beliefs. They hear many stories and try to seek connection and justify our cultural beliefs to construct an explanation that best suits their personal values, which I think is problematic.’

‘…during festivals, what is happening now is that not many people are inclined to learn traditional music, and therefore, the easiest music is being played. However, specific music has been developed for each season and passed down to generations, but people are now practising mainstream music […] We are contemplating what we can do to preserve our unique heritages…’ (ITS-08, active Maharjan in cultural events)

The need to negotiate between today’s reality and the historical past offers the exploration of various future possibilities for collective sensemaking through both retrospective and prospective sensemaking, a continuous process of conformity and disconformity sensitive to environmental dynamism.

During participant observations, the researcher noted that during the planning of festivals in which participation was declining, members relied more on emotions and spiritual dimensions than the cognitive dimensions of shared beliefs, knowledge and perceptions. However, interview and workshop data revealed that exogenous shocks (i.e., natural disasters or government policies) might explain these affective responses because they often emerge as a threat to their longstanding culture and traditions. GB-IS-16, a Maharjan handicraft owner believes that economic activities such as tourism may prompt positive emotional responses when it:

‘improve[s] our identity and create[s] jobs as well. When community members see the benefit of tourism, they will think about how they can contribute. Already, we are discussing what we can do to conserve Jatra and the role tourism can play in it.’

‘Elders in our Guthi are like libraries. They learnt from their ancestors by engaging in Guthi. Hence, Guthi is like a jewel of our society […] We are collectively working towards building a better future for our future generations.’

‘Our handicrafts became popular, they started producing in large quantities and are selling domestically and internationally….’

To ITS-05, an active youth Guthi member, tourism can engage ‘our musical events and dance performances and attract higher-end tourists, we will undoubtedly benefit from it…’ In fact, the speciality of ‘… every tole […] Every community will benefit if we organise these events commercially…’ But then, according to GA-IS-1, it is up to the community associations, through Guthis, to leverage tourism in a future that will continue Newars’ historical traditions (see ).

Figure 4. Elder’s conceptualisation (Group A) of the ideal future that can be attained through tourism during workshop.

During the workshop, participants drew land (a place called Shikali) where they have continued to practice festivals and processions for several generations. On the land there is a historical temple where Indigenous Newars from Khokana worship and pay respect to the goddess Rudrayani, an embodiment of a divinity tied to their historical cultural narrative. Three pots are tied to the annual procession organised in honour of Rudrayani and show that three Guthis collectively organise this festival. In addition, the marks drawn on the posts symbolise the tantric rituals integral to this festival. ITS-18, an advocate for women’s involvement in Guthi echoes the concern raised by the elder GA-IS-1 about the community’s declining traditional knowledge and insists on the integration of Newars’ traditional resources through the associations:

‘[…] we must work towards preserving and promoting our knowledge and traditions. We need to envision a tourism model that allows us to share our stories and create an economic value through a more proximal interaction.’

Discussion

Indigenous Newars’ ontology of relationality emphasises interconnectedness, integrating principles of respect, reciprocity and relatedness, which evokes a deep connection among humans, their ancestry and their environment. This perspective is both aligned with, and distinct from, Schwartz’s Schwartz (Citation2006) universal cultural values, as the ontological assumptions unique to Indigenous Newars shape their communal values. According to Browne (Citation1995) and Wilson and Inkster (Citation2018), respect is characterised by the fundamental human value that recognises caring interactions between humans and related entities within their socio-cultural ecosystems. Traditional Newari practices extend the concept of relatedness beyond human relationships (Leersnyder et al., Citation2015) to include environmental and material connections (Nisbet et al., Citation2011). Their sense of belonging also embraces spiritual entities, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse ways in which they perceive and engage with the world. Unlike Gouldner’s Gouldner (Citation1960) argument that reciprocal exchange manifests in a mutually beneficial relationship, this study shows that unilateral reciprocity occurs in the Newar community through Guthi, a cultural crucible that serves as a vehicle for translating Indigenous Newars’ socio-cultural values into economic and social practices. Hence, economic activities like tourism are in essence a resource on which Guthi relies to sustain the communities’ values, stories and beliefs.

Ransfield and Reichenberger (Citation2021) argue that integrating core Indigenous values into tourism practices can ensure progress towards sustainable tourism by nurturing cultural, ecological and social well-being. Becken and Kaur (Citation2022) and Scheyvens et al. (Citation2021) concur and recognise values-based tourism as a decolonising force that enriches tourism practices and bolsters the well-being of Indigenous peoples. This study contributes to this discourse by highlighting the role of community synergy, collective consciousness and collective sensemaking in weaving Indigenous knowledge and practices into tourism, particularly within the Newar community, offering novel theoretical insights into collaborative Indigenous tourism. We depict sustainable tourism as a symbiosis of Newar socio-cultural values and modern tourism practices. Their Guthi system illustrates this integration through a core cultural value of ‘leaving no one behind’ and can be attributed to their custom of unilateral acts of reciprocity, which contradicts Offer’s Offer (Citation2012) hypothesis on the burden of reciprocity by promoting (for more than 1700 years) inclusivity and communal reinforcement.

Tourism development initiatives that are imbued with Indigenous norms and practices inevitably take on an ‘Indigenous’ quality that reinforces the relationships of members with their value structures and belief systems. It is therefore not surprising that this particular mode of tourism advocates Indigenous cultural revitalisation and restoration of heritage sites. Thus, the image of tourism has the potential to be rehabilitated in the eyes of Indigenous communities. In this study, Guthi represents an intrinsically Indigenous force that influences the community’s cultural and economic activities, including tourism, despite external challenges to their very existence. Guthis ensure that reciprocity in tourism initiatives strengthens, rather than strains, community bonds. Similarly, the myths and narratives that Guthis carry and pass along transcend mere storytelling to serve as a medium for controlling and reinforcing the individual’s identity and connection within the community to guard against potential threats to social cohesion posed by modern tourism. These community stories, practices and history derived from a community’s collective consciousness are at the basis of social capital that Guthi provides and it is deemed a powerful safeguard against commodification and cultural dilution, which are particularly significant challenges facing tourism development in Indigenous communities.

The findings also demonstrate that Indigenous Newars’ collective sensemaking is characterised by temporality (Dawson & Sykes, Citation2019) and negotiation of alternative explanations (Awati & Nikolova, Citation2022). For Indigenous Newars, this implies that when confronted with decisions pertaining to tourism, they engage in a collective sensemaking process within Guthi that balances traditional knowledge with current realities, ensuring that their core values and traditional knowledge are sustained. This involves the interplay of retrospective and prospective sensemaking and explains how historical and contemporary temporalities (i.e., Indigenous Newars’ experiences with modernity, tourism development and evolving needs of tourism) shape the futuristic collective sensemaking process for sustainable tourism development. The responses to environmental dynamism, however, are not always immediate (Strike & Rerup, Citation2016). This study shows that community stakeholders often defer their response or engage in deliberate efforts to accommodate the shifting nature of the environment. Therefore, the salient theoretical contribution of this research lies in how Indigenous Newari communities synthesise their rich historical legacy with emerging tourism dynamics to foster sustainable development and cultural revitalisation.

In addition, although the literature acknowledges the significance of self-determination for Indigenous communities, there are few examples of its role in tourism development in developing countries. This study demonstrates that the support of Indigenous communities for tourism initiatives can be secured by the government’s and other stakeholders’ explicit recognition from the inception of any tourism blueprint of Indigenous rights to use and manage Indigenous ancestral lands on which tourism occurs. This additional step serves to further articulate Indigenous communities’ right of self-determination through tourism development.

Conclusion

Expressing Indigenous values through economic development activities such as tourism is not novel. Nor is situating Indigenous peoples’ historical knowledge within an existing frame of reference to elucidate how we can envision and work towards bringing alternative realities that align with our aspirations for better approaches (Rowse, Citation2009) to Indigenous tourism development. Contrary to a neoliberal approach to development, by incorporating core Indigenous values into business models, tourism enterprises contribute to the overall well-being of their community (Bunten, Citation2010). Therefore, the resulting approach to business should not only be viewed as an economic emancipation but also as a way to sustain culturally sensitive Indigenous values that can create economic benefits. This study does not simply identify the core values of Indigenous Newars that their Guthis promulgate, but it also brings new insights into the formation of collective social capital and collective sensemaking through the community association that is Guthi. The study shows how those values, along with their ontology of relationality, are important for community synergy and collective consciousness to set the foundations for the development of sustainable Indigenous tourism. In a practical sense, the findings of this study provide support for deriving strategies to develop tourism initiatives that embrace Indigenous Newar’s social and cultural values Simply put, a change in basic assumptions in the existing approach to Indigenous tourism development is essential; one that rejects the lingering colonial power dynamics to embrace and respect Indigenous Newars’ ontologies and traditional knowledge.

Although this study has several significant contributions towards the knowledge of collaborative Indigenous tourism, some limitations should be acknowledged. This study, focused on the ethnographic study of Newars’ Guthi system therefore there is opportunity to examine additional social institutions, such as Khokana’s oil cooperative, for a more comprehensive view of collaborative economic development. Moreover, the sole focus on Newar communities limits the generalisability of the findings. Nonetheless, the intent of this qualitative study is to generate in-depth theoretical insights rather than to generalise across contexts. Future research should investigate the role of Indigenous peoples’ social networks and collective decision-making processes in the development of collective consciousness towards the development of sustainable Indigenous tourism. Similar ethnographic studies in other Indigenous communities would provide external confirmation and trustworthiness of the findings in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roshis Krishna Shrestha

Roshis Krishna Shrestha is a PhD Candidate at the Research School of Management at the Australian National University. His research interests include Indigenous tourism, sustainable tourism, culture and heritage tourism, and rural tourism as applied to his native Nepal. Roshis has special interests in ethnographic methods and grounded theory.

J. N. Patrick L’Espoir Decosta

J. N. Patrick L’Espoir Decosta is an Associate Professor at the Research School of Management at the Australian National University. His research interests include tourism marketing, postcolonialism in tourism development, destination promotion and marketing, critical tourism studies, and Indigenous tourism. Patrick has expertise in grounded theory and historical research methods and has for some years looked at the integration of evidence-based methods in curriculum development and teaching in general management and tourism courses.

Michelle Whitford

Michelle Whitford is an Associate Professor at Griffith University. Her work has focused on the development of First Nations tourism since 1999. Her research and consultancy expertise in the field of Indigenous tourism and events includes policy, planning, sustainable development, management and evaluation. Her expertise also includes leading and co-coordinating government and private projects with a focus on Indigenous tourism supply and demand, capacity development, entrepreneurship, authenticity and commodification and management.

References

- Apostolopoulou, E., & Pant, H. (2022). “Silk Road here we come”: Infrastructural myths, post-disaster politics, and the shifting urban geographies of Nepal. Political Geography, 98, 102704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102704

- Awati, K., & Nikolova, N. (2022). From ambiguity to action: Integrating collective sensemaking and rational decision making in management pedagogy and practice. Management Decision, 60(11), 3127–3146. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2021-0804

- Becken, S., & Kaur, J. (2022). Anchoring “tourism value” within a regenerative tourism paradigm – a government perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1990305

- Bennike, R. B., & Nielsen, M. R. (2023). Frontier tourism development and inequality in the Nepal Himalaya. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2174129

- Blapp, M., & Mitas, O. (2018). Creative tourism in Balinese rural communities. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(11), 1285–1311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1358701

- Borquist, B. R., & Bruin, A. D (2019). Values and women-led social entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(2), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-08-2018-0093

- Browne, A. J. (1995). The meaning of respect: A First Nations perspective. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 27(4) 95–110.

- Bunten, A. C. (2010). More like ourselves: Indigenous capitalism through tourism. American Indian Quarterly, 34(3), 285–311.

- Chang, J., Su, W.-Y., & Chang, C.-C. (2011). The creative destruction of Ainu community in Hokkaido, Japan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 16(5), 505–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2011.597576

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Charmaz, K. (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & P. Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp. 155–172). The Guilford Press.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Sage.

- Christen, K. (2006). Tracking properness: Repackaging culture in a remote Australian town. Cultural Anthropology, 21(3), 416–446. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2006.21.3.416

- Cuong, V. M. (2020). Alienation of ethnic minorities in community-based tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(21), 2649–2665. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1733942

- Dawson, P., & Sykes, C. (2019). Concepts of time and temporality in the storytelling and sensemaking literatures: A review and critique. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(1), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12178

- Dolezal, C., & Novelli, M. (2022). Power in community-based tourism: Empowerment and partnership in Bali. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(10), 2352–2370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1838527

- Drawson, A. S., Toombs, E., & Mushquash, C. J. (2017). Indigenous research methods: A systematic review. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2017.8.2.5

- Foucault, M. (1970). The order of things: An archaelogy of the human sciences. Tavistock.

- Fu, X., Luan, R., Wu, H.-H., Zhu, W., & Pang, J. (2021). Ambidextrous balance and channel innovation ability in Chinese business circles: The mediating effect of knowledge inertia and guanxi inertia. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.11.005

- Gautam, P. (2018). Khokana’s Kols. The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/miscellaneous/2018/04/21/khokanas-kols

- Gellner, D. N. (1986). Language, caste, religion and territory: Newar identity ancient and modern. European Journal of Sociology, 27(1), 102–148. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600004549

- Gellner, D. N. (2007). For syncretism. The position of Buddhism in Nepal and Japan compared. Social Anthropology, 5(3), 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.1997.tb00375.x

- Ghimire, P. (2022). Fast track: Destroying Khokana. The Annapurna Express. https://theannapurnaexpress.com/news/destroying-khokana-5317

- Goodyear-Smith, F., Jackson, C., & Greenhalgh, T. (2015). Co-design and implementation research: Challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Medical Ethics, 16(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0072-2

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Gudynas, E. (2011). Buen Vivir: Today’s tomorrow. Development, 54(4), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.86

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2008). Justice tourism and alternative globalisation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(3), 345–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802154132

- Hinchliffe, S., & Bingham, N. (2008). Securing life: The emerging practices of biosecurity. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(7), 1534–1551. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4054

- Huneault, G., & Otomo, M. (2022). From unlikely to likely partnerships for change-child welfare and Indigenous tourism in Canada. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(10), 2476–2493. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1817047

- Hunt, S. (2014). Ontologies of Indigeneity: The politics of embodying a concept. Cultural Geographies, 21(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474013500226

- Izurieta, G., Torres, A., Patiño, J., Vasco, C., Vasseur, L., Reyes, H., & Torres, B. (2021). Exploring community and key stakeholders’ perception of scientific tourism as a strategy to achieve SDGs in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 100830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100830

- Kayastha, V. P. (2021). Khokana: Living museum of Nepal. My Republica. https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/khokana-living-museum-of-nepal/

- Khadka, R. K. (2020). Guthi system in Nepal and perpetual debate: Win-win deal is possible and inevitable. Onlinekhabar. https://english.onlinekhabar.com/guthi-system-in-nepal-and-perpetual-debate-win-win-deal-is-possible-and-inevitable.html

- Kim, S., & Kang, Y. (2020). Why do residents in an overtourism destination develop anti-tourist attitudes? An exploration of residents’ experience through the lens of the community-based tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(8), 858–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1768129

- Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, 4(3), 455–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/146613810343007

- Lalitpur Metropolitan City. (n.d.). Brief introduction. Retrieved from Lalitpurmun https://lalitpurmun.gov.np/en/node/4

- Leersnyder, J. D., Kim, H. S., & Mesquita, B. (2015). Feeling right is feeling good: Psychological well-being and emotional fit with culture in autonomy- versus relatedness-promoting situations. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 630. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00630

- Lertzman, D. A., & Vredenburg, H. (2005). Indigenous peoples, resource extraction and sustainable development: An ethical approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(3), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-3528-8

- Lonardi, S., Martini, U., & Hull, J. S. (2020). Minority languages as sustainable tourism resources: From Indigenous groups in British Columbia (Canada) to Cimbrian people in Giazza (Italy). Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102859

- Lor, J. J., Kwa, S., & Donaldson, J. A. (2019). Making ethnic tourism good for the poor. Annals of Tourism Research, 76, 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.03.008

- Löwdin, P. (1998). Food, ritual and society - A study of social structure and food symbolism among the Newars. Mandala Book Point.

- Manaf, A., Purbasari, N., Damayanti, M., Aprilia, N., & Astuti, W. (2018). Community-based rural tourism in inter-organizational collaboration: How does it work sustainably? Lessons learned from Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Gunungkidul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability, 10(7), 2142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072142

- McDonagh, S. (2021). Four essential Indigenous tourism projects that are sustainable for both the land and its people. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/travel/2021/08/09/four-essential-indigenous-tourism-projects-that-are-sustainable-for-both-the-land-and-its-

- Molm, L. A. (2007). The structure of reciprocity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 73(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272510369079

- Movono, A., Dahles, H., & Becken, S. (2018). Fijian culture and the environment: A focus on the ecological and social interconnectedness of tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(3), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1359280

- Murga, A. (2020). Why indigenous folklore can save animals’ lives. BBC Future Planet. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200728-the-mythical-creatures-that-protect-the-philippines

- Narvaez, D., Arrows, F., Halton, E., Collier, B., & Enderle, G. (2019). People and planet in need of sustainable wisdom. In D. Narvaez, F. Arrows, E. Halton, B. Collier, & G. Enderle (Eds.), Indigenous sustainable wisdom: First-nation know-how for global flourishing (pp. 1–24). Peter Lang Publishing.

- Nepal Tourism Board. (n.d.). Patan. Retrieved from NTB.

- Ngo, T., & Pham, T. (2023). Indigenous residents, tourism knowledge exchange and situated perceptions of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1920967

- Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Murphy, S. A. (2011). Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9197-7

- Offer, S. (2012). The burden of reciprocity: Processes of exclusion and withdrawal from personal networks among low-income families. Current Sociology, 60(6), 788–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392112454754

- Phillips, T., Taylor, J., Narain, E., & Chandler, P. (2021). Selling Authentic Happiness: Indigenous wellbeing and romanticised inequality in tourism advertising. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103115

- Pubill Ambros, A., & Buzinde, C. N. (2021). Indigenous communities engaging in tourism development in Arizona, USA. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(3), 296–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2021.1999458

- Ransfield, A. K., & Reichenberger, I. (2021). Māori indigenous values and tourism business sustainability. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180121994680

- Richards, G. (2011). Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1225–1253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.008

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Rowse, T. (2009). The ontological politics of ‘closing the gaps’. Journal of Cultural Economy, 2(1–2), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350903063917

- Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2019). Cultural heritage and Indigenous tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1581788

- Scheyvens, R., Carr, A., Movono, A., Hughes, E., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Mika, J. P. (2021). Indigenous tourism and the sustainable development goals. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103260

- Schwartz, S. (2006). A theory of cultural value orientations: Explication and applications. Comparative Sociology, 5(2–3), 137–182. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913306778667357

- Selibas, D. (2021). Buen Vivir: Colombia’s philosophy for good living. BBC Travel. http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20210207-buen-vivir-colombias-philosophy-for-good-living

- Shrestha, R. K., & L’Espoir Decosta, P. (2023). Developing dynamic capabilities for community collaboration and tourism product innovation in response to crisis: Nepal and COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(1), 168–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.2023164

- Smith, L. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

- Stoffle, R., Seowtewa, O., Kays, C., & Vlack, K. V. (2020). Sustainable heritage tourism: Native American preservation recommendations at arches, canyonlands, and hovenweep national parks. Sustainability, 12(23), 9846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239846

- Strike, V. M., & Rerup, C. (2016). Mediated sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 59(3), 880–905. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0665

- Stumpf, T. S., & Cheshire, C. L. (2019). The land has voice: Understanding the land tenure – sustainable tourism development nexus in Micronesia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 957–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1538228

- Tandon, G. (2018). Nepalma Guthivyavastha. Sangri-La Books.

- Taylor, G. (1995). The community approach: Does it really work? Tourism Management, 16(7), 487–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00078-3

- Tunstall, E. (2020). Decolonizing design innovation: Design anthropology, critical anthropology, and Indigenous knowledge. In W. Gunn, T. Otto, & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Design anthropology: Theory and practice (pp. 232–250). Routledge.

- Velasco-Herrejón, P., Bauwens, T., & Friant, M. C. (2022). Challenging dominant sustainability worldviews on the energy transition: Lessons from Indigenous communities in Mexico and a plea for pluriversal technologies. World Development, 150, 105725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105725

- Villalba, U. (2013). Buen Vivir vs Development: A paradigm shift in the Andes? Third World Quarterly, 34(8), 1427–1442. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.831594

- Vollstedt, M., & Rezat, S. (2019). An introduction to grounded theory with a special focus on axial coding and the coding paradigm. In G. Kaiser & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Compendium for early career researchers in mathematics education (pp. 81–100). Springer.

- Waddock, S. (2019). Wisdom, sustainability, dignity, and the intellectual shaman. In D. Narvaez, F. Arrows, E. Halton, B. Collier, & G. Enderle (Eds.), Indigenous sustainable wisdom: First-nation know-how for global flourishing (pp. 244–264). Peter Lang Publishing.

- Williams, L. K., & Gonzalez, V. V. (2017). Indigeneity, sovereignty, sustainability and cultural tourism: Hosts and hostages at ʻIolani Palace, Hawai’i. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1226850

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

- Wilson, N. J., & Inkster, J. (2018). Respecting water: Indigenous water governance, ontologies, and the politics of kinship on the ground. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 1(4), 516–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618789378

- Yeh, J. H-y., Lin, S-C., Lai, S-C., Huang, Y-h., Yi-Fong, C., Lee, Y-T., & Berkes, F. (2021). Taiwanese indigenous cultural heritage and revitalization: Community practices and local development. Sustainability, 13(4), 1799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041799

- Zhang, Y., Xiong, Y., Lee, T. J., Ye, M., & Nunkoo, R. (2021). Sociocultural sustainability and the formation of social capital from community-based tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 60(3), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520933673