Abstract

The polar regions are increasingly at the center of attention as the hot spots of climate crisis as well as tourism development. The recent IPCC reports highlight several climate change risks for the rather carbon-intensive and weather-based/dependent polar tourism industry in the Arctic and the Antarctic. This study presents the scholarly state-of-knowledge on tourism and climate change in the polar regions with a literature survey extending beyond the Anglophone publications. As a supporting tool, we provide a live web GIS application based on the geographical coverages of the publications and filterable by various spatial, thematic and bibliographical attributes. The final list of 137 publications indicates that, regionally, the Arctic has been covered more than the Antarctic, whilst an uneven distribution within the Arctic also exists. In terms of the climate change risks themes, climate risk research, i.e. impact and adaptation studies, strongly outnumbers the carbon risk studies especially in the Arctic context, and, despite a balance between the two main risk themes, climate risk research in the Antarctic proves itself outdated. Accordingly, the review ends with a research agenda based on these spatial and thematic gaps and their detailed breakdowns.

Introduction

The tourism system and the climate crisis are on a constant interplay to shape each other’s futures. On the one hand, climatic changes have direct and indirect impacts on the tourism products, whereas on the other hand, touristic consumption tends to have a high carbon footprint, hence driving climate change. These mutual effects become more prominent when relatively remote, thus carbon-intensive, and weather-based/dependent tourism destinations are in question. As such, the polar regions are increasingly at the center of academic, political, and practical attention as the hot spots of climate crisis as well as tourism development (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020; Meredith et al., Citation2019).

The Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on the physical science basis of climate change (IPCC, Citation2021, also see the IPCC’s WGI Interactive Atlas at https://interactive-atlas.ipcc.ch) highlights that, in the Arctic, sea ice decrease and Greenlandic ice sheet melt in the last decades have resulted from human influence with a 90–100% likelihood. September Arctic sea ice is projected to disappear already by 2050 according to the mid and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios (IPCC, Citation2021). Ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica are projected to disappear throughout the twenty first century with 99–100% and 66–100% likelihoods, respectively (IPCC, Citation2021). Across the entire Arctic, there is an observed trend for increases in extreme heats since 1979 (IPCC, Citation2021), along with losses of snow cover and glaciers, and a medium confidence for increasing fire risks by 2050s, according to the mid and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios (IPCC, Citation2021). Indeed, Arctic warming rate is observed to be quadruple the rate of global warming within the last four decades since 1979 (Rantanen et al., Citation2022).

In relation to these physical changes, the latest reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (IPCC, Citation2022a) and mitigation (IPCC, Citation2022b) highlight the most relevant phenomena for polar tourism as those climate risks such as shortening seasons and safety issues for snow and/or ice based activities such as dogsledding, skiing, snowmobiling and floe edge tours due to diminishing snow cover and sea ice extents and durations. These most often negative physical impacts are, however, also pointed as bringing “opportunities” in the forms of longer warm weather seasons and increased demand and supply of cruise and “last chance tourism (LCT)” (IPCC, Citation2022a). As such, negative impacts on biodiversity (e.g. polar bears) and landscapes (e.g. glaciers) become the attraction, or the motive, of this trending tourism type. According to the IPCC. (Citation2022a; Citation2022b), popularity of the LCT as well as the improvement of maritime accessibility with diminishing sea ice also gives rise to polar cruise tourism, yet with increased carbon risks arising from ships’ emissions. As Scott et al. (Citation2023) note, tourism in general is often portrayed as part of the solution to climate change within the latest IPCC reports (Citation2022a; Citationb), but not as part of the problem itself, as well as the victim to the problem, thus not comprehensively covered. Such limited coverage is also true for the earlier, yet regionally more specific, Special Report on the Ocean and the Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) by the IPCC (Meredith et al., Citation2019), reviewing about 39 publications on polar tourism and climate change, with focus on climate risks associated with cruise tourism and LCT (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020).

Besides the IPCC discourse, climate change and tourism scholarship itself has been developing since 1986 (Becken, Citation2013) and polar tourism research can be dated back to even as early as 1980 (Stewart et al., Citation2017). The intersecting literature on climate change and polar tourism, however, is assessed to be young, with the earliest studies starting only from 2004 (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020). Accordingly, the most prominent theme appears to be climate change adaptation of Arctic tourism. This is then followed by the topic of the so-called “combined impacts” of climate change and tourism in Antarctica—e.g. the region’s exposure to warming together with the effects of increased touristic mobilities as vectors to sensitive environments and biodiversity. Other themes based on the keyword clusters are then mostly about issues related to cruise tourism and last chance tourism. Another noteworthy finding here is that, in line with the introduction of the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the IPCC in 2013–2014, the keyword “climate change” becomes more frequently used than “global warming.” Moreover, over the course of the assessed literature from 2004 to 2019, pioneering research stems from Canada-based North American papers while European Arctic tourism also becomes a hot topic in the later years. All in all, the review concludes that most of this article-based, Anglophone literature, extending from 2004 to 2019, has the “climate risk” (impacts and adaptation), rather than “carbon risk” (emissions and mitigation), in its focus, and that the coverage of climate risk fails to be spatially inclusive, especially regarding the Russian Arctic and the Antarctic with its gateways in the Southern Hemisphere.

In this study, we offer an extended review of climate change and tourism in the polar regions through a survey of up-to-date publications in all relevant languages of the region and formats including but not limited to journal articles. A Web GIS (geographical information system) is also developed to help interactively and geo-visually present the literature as filterable by year, country, language, publication type and, not least, the themes. In the following parts of this paper, we introduce the study area and our methodology, followed by syntheses of key impacts, adaptation levels, emissions and mitigation efforts, and concluded by a research agenda based on the spatially and thematically identified knowledge gaps.

Study area

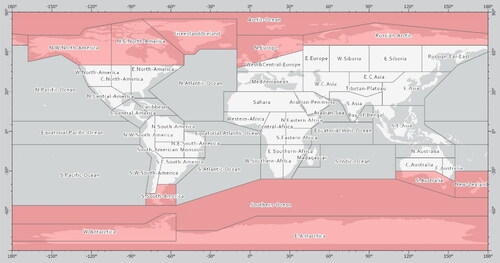

The polar regions of the Earth, namely the Arctic and the Antarctic, are defined by a variety of delineations according to different political and physical sources (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020). Even within the IPCC terms, a standard regionalization is not always consistent. As pointed out in the Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC (Citation2014) has conventionally defined the Arctic as north of the Arctic Circle (66°N) and the Antarctic as south of the Polar Front, extending to 58°S, while the need for a flexible regionalization approach for different contexts has also been acknowledged. Indeed, the SROCC (Meredith et al., 2019, p. 211) has adopted “a purposefully flexible approach” whereby the Antarctic extends to as north as the Subantarctic Front beyond 50°S and the Arctic covers as south as beyond the 50°N—wherever the cryospheric elements such as permafrost and snow cover are most prominent. In this paper, we also remain as flexible to treat the region from a tourism system perspective, where the “polar products” of tourism may agglomerate only around certain areas of the eight states of the Arctic Council, while the footprints and gains could extend far beyond even the IPCC’s recent flexible borders when, for instance, the touristic gateways of the Antarctic in South America, Oceania, and even South Africa, are taken into account. Therefore, the spatial coverage () of our literature survey matches with the reference regions East Antarctica, West Antarctica, Southern Ocean, Southern South America, Southern Australia, New Zealand, North-Western North America, North-Eastern North America, Arctic Ocean, Greenland/Iceland, Northern Europe, and the Russian Arctic, as defined in the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the IPCC (Iturbide et al., Citation2020).

The surveyed regions cover different countries and territories that portray various polar selling propositions, travel trends, and tourism-climate policy nexuses. In North America, the Alaska Travel Industry Association (ATIA) promotes its Far North region as the “Arctic,” characterized by the northern lights, the snowy landscapes and the long summer days, the wildlife, and not least the indigeneous cultures. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Alaska’s out-of-state visitor volume had increased by 43% during the 2010–2019 period, peaking with 2,536,000 visitors in 2018–19, where 53% entered or exited by cruise and 43% by air (ATIA, Citation2020). In Canada, tourism is regarded as a strong contributor to economic sustainability and a safeguard for the indigeneous cultural heritage in the country’s remote areas such as the Arctic (Government of Canada, Citation2023), which can be defined by destinations such as Yukon, Nunavut, Northwest Territories, Nunavik, Labrador and Churchill, altogether attracting more than half million visitors per year already in the early 2010s (Maher et al., Citation2014).

Tourism in the Arctic extends from North America to the Nordic countries and Russia. It is a highly strategic sector for Denmark’s two overseas territories, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, for the much-needed economic diversification and strengthening of the autonomies. During 2014–2019, overnight stays grew by 44% and 25% in the Faroe Islands and Greenland, respectively, where cruise tourism plays a major role (Visit Faroe Islands, Citation2019; Visit Greenland, Citation2021). Another Arctic insular destination, Iceland, known for its unique blend of cryospheric and volcanic attractions, experienced a boom in its tourism industry with the mostly airborne international arrivals quintupling from 460,000 to 2.3 million during 2010–2018 and the overnight stays tripling from 3.3 million to 10 million during 2011–2019 (Icelandic Tourism Board, Citation2021). Such significant tourism development is also highly visible in the Fennoscandian Arctic, where Arctic Norway’s islands of Svalbard, Bjørnøya and Jan Mayen and the mainland counties of Nordland, Troms and Finnmark registered 4.2 million overnight stays, of which 1.6 million were foreign nationals, in the pre-pandemic 2019 season (Statistics Norway, Citation2024). During the same season, in Arctic Finland, i.e. the Lapland Region where thematic products such as Santa Claus/Christmas tourism have been historically very strong, 3.1 million overnight stays (of the national total of 23 million), of which 1.6 million were internationals (compared to the 7.1 million total), have taken place (Statistics Finland, Citation2024). In Sweden, the so-called “Arctification” trend has been on the stage with the number of firms with Arctic-related names in the two northernmost counties, Norbotten and Västerbotten, having reached 218 by 2019 (Marjavaara et al., Citation2022). The Russian Arctic, on the other hand, covering a vast geography from the Kola Peninsula and the Arctic National Park (Severny Island and Franz Josef Land) to Siberia, attracted around 1 million tourists in both 2019 and 2023, maintaining the pre-pandemic visitor volume despite the war outbreak (Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East & Arctic, Citation2020; TASS, Citation2024).

Popularity of tourism in the Arctic for consumers, businesses and policymakers is also well reflected in the quest for the Antarctic’s unique nature and wildlife. Despite the continent’s uninhabited landscapes, except for the presence of scientific missions, a record-breaking 106,000 touristic arrivals, with seaborne (95%) and airborne (5%) trips from gateway cities such as Ushuaia (Argentina), Punta Arenas (Chile), Hobart (Australia), Christchurch (New Zealand) and Cape Town (South Africa), were registered for the 2022–2023 season—compared to the 6700 visitors in the 1992–1993 season and the 74,000 visitors in the previous record-high season of 2019–2020 before the pandemic (International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators, Citation2022; Varnajot et al., Citation2024). In addition to the revenues and jobs gained by logistic support, the gateway cities themselves have also been offering in-place, Antarctic-related thematic attractions and activities (Jensen et al., Citation2016; Dodds & Salazar, Citation2021), making them a subtle component of a wider “Antarctification” process (Varnajot et al., Citation2024).

Along with the tourism growth trends towards the polar regions, governing policies and practices have also been materializing, yet with not much of a consistent tourism-climate nexus across the regions and the at the different governance levels. In Russia, the “Strategy for the development of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation and ensuring national security for the period until 2035” (Russian Government, Citation2020) has no explicit coverage of the tourism-climate nexus. In the USA, the “National Strategy for the Arctic Region” (White House, Citation2022) names tourism as one of the main sectors to be supported for the sake of Alaksa’s sustainable growth and job creation but no national tourism policy addresses climate change risks, from an industrial and regional perspective. Such risks are covered as part of the voluntary “Adventure Green Alaska (Citation2018)” certification scheme’s climate change audit. In the study area, Canada’s “Federal Tourism Growth Strategy” (Innovation & Science & Economic Development Canada, Citation2023) and Norway’s “National Tourism Strategy 2030” (Innovation Norway, Citation2021) are the only two policy documents that acknowledge both the climate and the carbon risks of tourism at the national government level. Besides its focus on the development of tourism in the rural and remote regions such as the Arctic, Canada’s strategy promotes climate action in line with the national net-zero emission target by 2050, and partly fulfilling the gap for a national regulatory framework for creating a responsible destination with regards to climate change mitigation (Dodds & Graci, Citation2009). However, while concrete plans towards shifting from car-based transportation to more active modes such as walking and biking at the destinations and funding sustainable aviation technologies exist, the country is still challenged by touristic carbon risks due to its global remoteness and the vast terrain and the consequent air/car travel dependency, the popular and carbon-intensive cruise tourism product, and the high demand from car-based crossborder travel from the USA. In Norway, too, the strategy embraces the developmental contribution of tourism, especially with job creation, in the most remote regions, with major growth already taking place in North, and the mitigation challenge is clearly underscored by encouraging “high yield—low impact” target markets, i.e. visitors that spend the most with longer stays and emit the least with shorter distances, as well as a more localized supply chain.

Explicit reference to the carbon, if not the climate, risks is evident in the national tourism policies of other Nordic countries as well. In Finland, the “Sustainable Travel Finland” programme supports the travel industry in the pursuit of low-carbon operations by providing them with carbon calculators (Visit Finland, Citation2019). In Sweden, mitigation challenges requiring fossil-free transport systems and circular business models along the entire tourism value chain is highlighted under the “Strategy for Sustainable Tourism and Growing Hospitality Industry” (Regeringskansliet, Citation2021). In Iceland, the former national tourism policies, i.e. the “Tourism Strategy for 2011–2020” (Althingi, Citation2011), “Promote Iceland: Long-term Strategy for the Icelandic Tourism Industry” (PKF., Citation2013) and the “Road Map for Tourism in Iceland” (Ministry of Industries & Innovation & Icelandic Travel Industry Association, Citation2015), were mostly focused on increasing profitability and professionalism of the tourism sector and extending the sector’s operation season and destinations outreach, with no mention of climate action (Gren & Huijbens, Citation2014). However, the new tourism strategy for 2021–2030 (Ministry of Industries & Innovation, Citation2019) gives the tourism-climate policy nexus a more prominent place by stating that the Icelandic tourism sector needs to take up a pioneering role in energy transition and use of eco-friendly energy sources and reduce its carbon footprint—yet the mitigation of international travel emissions from air and cruise arrivals is not clearly addressed. Likewise, in the Faroe Islands, the former policy (Visit Faroe Islands, Citation2021) has addressed the need to limit and to tax cruise tourism mainly due to carrying capacity issues, not necessarily carbon footprint concerns. The new “Heim: Tourism strategy towards 2030,” however, states a “wish” to “support the climate policy set by the Faroe Islands and the international community” (Visit Faroe Islands, Citation2023, p. 86). In Greenland, where tourism is a key growth sector with a need for long-distance markets, no climate change risks were covered under the “Towards More Tourism” strategy (Visit Greenland, Citation2021).

In terms of Antarctic tourism, no climate change risks are covered under the polar tourism related policies of the major gateway cities’ parent countries—Argentina, Chile, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia. When looking into the other way around, i.e. how the climate policies cover the tourism issues, the situation is not very different. The gateway cities are part of a supranational body of agreements, i.e. Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), and there the “Helsinki Declaration on Climate Change and the Antarctic” has prioritized the decarbonization of the tourism sector but not mentioned any tourism-specific impacts and adaptation needs, except for the historic sites and monuments (Antarctic Treaty, Citation2023). Likewise, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that define the climate action efforts of the countries as parties of the international climate treaty, the Paris Agreement, are also limited, if not lacking, with respect to the tourism sector (UNFCCC., Citation2024). Here, Chile and Argentina have the widest coverage of tourism in their latest NDC updates, but not necessarily with linkages to their Antarctic tourism development. All other Antarctic gateway countries, apart from New Zealand, where no tourism content is covered under the latest NDC, as well as the Arctic nations, mention tourism only as an economic sector to help mitigation co-benefits through diversification-based adaptation. Greenland, on the other hand, has not become a part of the EU NDC, where Denmark is a party, and decided to develop its own climate policy and NDC with the right to exclude certain sectors’ emissions for the sake of economic development (UNRIC, Citation2023).

Methods

Given the heterogeneity of the physical climate risks in the polar regions, the growing popularity and the vulnerability of the most often climate-based/dependent tourism products, the dominance of long-haul trips with generally carbon-intensive travel modes, and the complexity of all these triggers and the different levels of business and policy responses, this study aims for an understanding of the state of the scholarly knowledge on tourism and climate change in the polar regions. For this purpose, the survey builds upon the most recent review on this topic (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020), which covered 93 peer-reviewed articles in 51 different scientific journals published during 2004–2019. In this study, we initially replicated the Boolean string “((Antarctic* OR Arctic OR polar) AND ‘climate change’ AND touris*)” for the identification of publications through their titles, abstracts and keywords on the Web of Science and the Scopus databases. In addition, each polar country/region name was added to the string and a search was also repeated with different relevant languages (Spanish, French, Russian, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Icelandic, Finnish) and including more local databases relevant to the study area, such as Leitir (Iceland), Oria (Norway), DiVA (Sweden), Finna (Finland), Arto (Finland), eLibrary.Ru (Russia), Google Scholar (Russian and Icelandic versions), Latindex (Ibero-America), REDIB (Ibero-America), Redalyc (Ibero-America) and SciELO (Ibero-America and South Africa). All these steps helped maximize the coverage, yet still with limitations due to the linguistical diversity of the authors of this study and the conventional dominance of Anglophone contents in the main databases such as Scopus (Albarillo, Citation2014). We also identified other sources through backward and forward snowballing techniques to check and select the thematically relevant papers cited by and citing our initial list. These additionally selected papers were extended further by adding others familiar to the authors. No publication type filter was applied to be as inclusive as possible, covering books, chapters, dissertations, proceedings and reports besides the articles. The ultimate listed yielded 137 publications (from 2004 to early 2022), well exceeding the 93 articles (2004–2020) assessed as eligible by Demiroglu and Hall (Citation2020). In this instance, only eight publications belonged to the “other” type—one book, three chapters, one dissertation, one proceeding, and two reports—while the remaining 129 were all peer-reviewed journal articles.

During meta-analysis, the geographical scopes and the tourism types in question were detected for each publication, followed by a coding of the climate related themes, where at least one author as the initial coder was to have a mutual agreement with the overseeing author. During coding, a consistency with the similar macro-regional climate change and tourism reviews in the journal (Dube et al., Citation2023; Fang et al., Citation2022; Higham et al., Citation2022; Navarro-Drazich et al., Citation2023; Rutty et al., Citation2022; Steiger et al., Citation2023; Wolf et al., Citation2022) were sought after. Accordingly, the two major themes were the “climate risks” and the “carbon risks,” further broken down into the sub-themes of “impacts” and “adaptation” for the climate risks and “emissions” and “mitigation” for the latter. An additional main theme “climate and carbon risks” was also placed, following Demiroglu and Hall (Citation2020), to reflect on the duality of special cases—e.g. (mal)adaptation leading to more impacts/emissions. Lastly, further elaboration on the sub-themes was realized by identification of the impact types as (1) average and extreme temperatures, (2) altered precipitation patterns (including cryosphere changes), (3) extreme weather (flood, fire, drought, storms/hurricanes), (4) sea level rise and coastal change, (5) ecosystem/biodiversity change, (6) ocean temperatures and acidification, (7) human health risks, (8) social disruption/security (including population displacement), and (9) economic development/growth—with an additional binary code for integrated assessments that study multiple risks. Adaptation research, on the other hand, was classified according to the four generations, suggested by Klein et al. (Citation2017), in terms of descriptive, normative, policy-wise and practical priorities and foci. Lastly, carbon risk papers were categorized according to the four global, national, sub-national (destination) and business- level scales of emissions and mitigation action, as suggested by Gössling et al. (Citation2023).

Owing to the multi-thematic and/or the multi-geographical natures of some publications, more “cases” than the publications themselves were identified. For instance, a publication studying both the impacts of climate change on polar bear tourism and indigeneous tourism at a destination and the emissions of cruise tourism to the destination would be made of three cases under the “study area—tourism type—climate theme” scheme, i.e.; (1) “destination—polar bear tourism—impacts,” (2) “destination—indigeneous tourism—impacts,” (3) “route—cruise tourism—emissions.” Such an approach translated the 137 articles into 272 cases that can be used in different syntheses, both textually and visually.

As Lim et al. (Citation2022) suggest, innovative ways are needed to push the qualities of literature reviews which are standing out more as independent studies such as this one. One way to differentiate the reviews for spatially oriented domains is through a “geobibliography,” which, in the most basic sense, is a methodology developed by Demiroglu et al. (Citation2013), and later applied to polar tourism (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020), to cartographically locate studies according to their geographical scopes and to symbolize them according to their thematic attributes using (Web) GIS (geographical information systems). Web GIS enables not only an interactive display for the users, but also provides opportunities for future data collection and analytics in an efficient way (Fu, Citation2022).

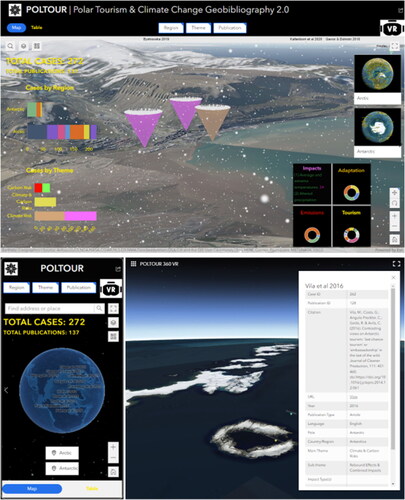

The geobibliography methodology has received a good adoption so far, with SkiKlima (Demiroglu et al., Citation2013) having more than 35,000 views since 2011. For this review, we developed POLTOUR 2.0 (see https://poltour.geo.umu.se), by employing the Experience Builder, within the ArcGIS Online (AGOL) ecosystem, which allows for creating desktop and mobile apps in a dashboard fashion with a customized design and a variety of widgets (Gaigg, Citation2023), such as the world-renowned COVID-19 Dashboard by Johns Hopkins University (Dong et al., Citation2020), and, thus is able to provide a more sophisticated experience compared to the Google My Maps based first version of POLTOUR (Demiroglu & Hall, Citation2020, see https://tiny.cc/poltour1 for a backup). Moreover, a widget was integrated through the ArcGIS Survey123 platform, to keep the app collaborative with the users, by enabling the submission of any missing publications. Finally, the ArcGIS 360 VR platform was utilized to develop a proof-of-concept virtual-reality for a more tangible experience of the geobibliography.

The POLTOUR Geobibliography 2.0 () is based on a 3D web map (a “web scene”) with a main layer of “cases,” complemented by the climate reference regions layer delineated by the IPCC (Iturbide et al., Citation2020). A “case” is defined as a point feature whose coordinates are determined by the actual geographical locations covered by its parent publication. It should, however, be noted that, the “spatialization” process, i.e. the efforts towards determining the representative case locations, has been a major challenge, as some studies cover wider regions and some are either ambiguous or confidential about their spatial limits.

Figure 2. POLTOUR 2.0 (poltour.geo.umu.se) Web Experience map view zoomed in to Svalbard (top), mobile version (bottom left), and VR view for the South Shetland Islands (bottom right).

Users can interact with POLTOUR’s interface for searching for places/attractions, toggling on/off layers, changing basemaps, and filtering for regions, themes and publication years, types, languages. Filtered results are reflected on the charts, map features, and the Table View, which allows for an export of all or selected records within a CSV, JSON or GeoJSON file. Clicking on map features opens popups that give information about the cases and links the users to the original publications. Likewise, the “VR” button opens up the web scene slides where the user can interact with the features in virtual reality, using desktop or mobile devices, but best within a VR headset with a web browser app. Below, we utilize POLTOUR to understand the breakdown of and the research gaps related to the climate and the carbon risks of tourism in the polar regions.

Results

According to our survey and the POLTOUR indicators; there are 137 publications on the topic of tourism and climate change in the polar regions, representing 272 cases, 171 of which are on climate risks, 42 on carbon risks, and the remaining 59 on both. Regionally, the Antarctic is covered by 47 cases, whereas the Arctic is subject to 225 cases, mostly in Canada (n: 64), Norway (n: 45), Finland (n: 35) and Greenland (n: 24), followed by USA (n: 19), Russia (n: 18), Iceland (n: 15) and Sweden (n: 4). This rather uneven regional distribution manifests itself despite our efforts for being as inclusive as possible by surveying all publication types in all relevant languages, where eventually 126 publications were in English with few others in Finnish (n: 4), Russian (n: 3), Spanish (n: 3) and French (n: 1). When publications are filtered from the year 2014 onwards, a similar trend is also valid for the post-AR5 era, with the most case coverage on the four Arctic countries Norway (36), Canada (33), Greenland (22) and Finland (21) and the climate risk sub-themes (impacts: 58, adaptation: 55) versus the carbon risk sub-themes (emissions: 7, mitigation: 18). Below we elaborate the recurring themes on both risk categories, and finally discuss the regional and the thematic gaps and an agenda for future research.

Climate risk

Climate risk is the most studied main theme within the polar tourism and climate change domain, and it is almost evenly broken down between its two sub-themes “impacts” (45 publications and 88 cases in total, and 28 publications and 58 cases in the post-AR5 era) and adaptation (49 publications and 83 cases, and 32 publications and 55 cases in the post-AR5 era). Regarding the distribution of impact studies (), whilst most studies are integrated assessments, some impact types are underrepresented and almost no study exists for the Antarctic, especially in the latter period, except for some studies on rebound effects and combined impacts, where, for instance, seabird populations, including the iconic penguins, are found to be affected both negatively and positively by increasing temperatures and touristic visits (Dunn et al., Citation2019; Petry et al., Citation2016; Raya Rey et al., Citation2014), while in the Arctic, the combined impacts of climate change and tourism development tend to cause detrimental effects for biodiversity (Tolvanen & Kangas, Citation2016), especially the polar bears (Rode et al., Citation2018). Consequently, a debate also rises on the potential environmental stewardship/ambassadorship of the “last chance tourists” to the Antarctic (Vila et al., Citation2016) and the Arctic (Abrahams et al., Citation2022; Groulx et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2020), since such transformation at times turns out to be much of a wishful thinking, leaving behind no real changes but combined local climate and tourism impacts and the high footprints of air- and/or cruise-based long-haul travels to the polar regions (see Carbon Risk).

Table 1. Regional and temporal distribution of climate risk publications by impact types.

In the Arctic, post-AR5 research on impacts has doubled itself with 28 publications (58 cases) on and after 2014, compared to the 14 publications (26 cases) before. Some authors have studied single impacts on multiple sites and tourism types, e.g.; precipitation effects on ski tourism in Greenland (Schrot et al., Citation2019) and (Arctic) Norway (Scott et al., Citation2020). There is even a couple of pan-Arctic cases of temperature impacts on summer tourism (Huang et al., Citation2021) and increased summer Arctic cyclone activity risks on cruise tourism (Day & Hodges, Citation2018), which, along with yacht tourism (Johnston et al., Citation2017a), is expected to become more popular not only because of last chance tourists but also thanks to increased navigational opportunities with less sea ice, yet at a cost of decreased attractiveness (Bystrowska, Citation2019). Another study (Denstadli & Jacobsen, Citation2014) on summer sightseeing tourism in Svalbard (Norway), has looked into how the combined effects of changing temperature, precipitation and extreme weather patterns impact visitor perceptions and responses, finding out that reduced visibility in the future, as a consequence of projected increases in precipitation and overcast skies, could become a problem for the destination. Among the other post-AR5 integrated impact assessments; Lépy et al. (Citation2016) found evident increases in changing weather and slippery conditions and tourist safety issues against accidents at a nature-based tourism destination in Arctic Finland, whereas Teryutina (Citation2021) highlighted the demographic and the economic challenges posed by a changing climate to the indigeneous peoples of the Russian Arctic.

As with impact assessments, adaptation research has also almost doubled itself with 32 publications (55 cases) after the release of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report, compared to the 17 publications (28 cases) before. This era has witnessed more presence of the “fourth generation” studies that deal with the actual performances of the adaptation efforts on the field, seeking after performance measurement and knowledge gaps (Klein et al., Citation2017). Here the studies focused on ski tourism in Finland (Kaján, Citation2014, Tervo-Kankare et al., Citation2018), Norway (Dannevig et al., Citation2021) and Greenland (Schrot et al., Citation2019), cruise tourism in Canada (Dawson et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Lasserre & Tetu, 2015) and Norway (Lamers et al., Citation2018), Christmas tourism in USA and Finland (Hall, Citation2014), and glacier tourism in Iceland (Welling & Abegg, Citation2021).

The series of papers on Icelandic glacier tourism and climate change provide a good example on the generational evolution of adaptation research, where, as a second generation study, Welling et al. (Citation2019) made use of a case study of Þröng and organized workshops to find out about the best practices against potential impacts. Then Welling et al. (Citation2020) went on to administer a consumer survey to inform the practitioners and the decisionmakers about future needs for a sustainable glacier tourism, reflecting a third generation study, as the focus on governance with the involvement of businesses and policymakers is typical of this generation. Finally, Welling and Abegg (Citation2021) interviewed Icelandic glacier tour operators to reveal their ongoing adaptation efforts and future needs, in line with the purposes of the fourth generation studies mentioned above.

During the post-AR5 era, the few first generation studies that explored potential risks included those on nature-based tourism in USA (Sisneros-Kidd et al., Citation2019), Finland (Lépy et al., Citation2014), Norway and Russia (Koenigstein et al., 2016), and Antarctic cruise tourism (Liggett et al., Citation2017). Second generation research encompassed marine tourism in Canada (Johnston et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Olsen et al., Citation2019; Stewart et al., Citation2015), Russia and Norway (Olsen et al., Citation2019), and the lodging sector in Greenland (Qu et al., Citation2015) and Russia (Sarvut, Citation2018). As for the third generation; the prominent studies were about ski tourism in Norway (Scott et al., Citation2020), cruise tourism in Canada (Palma et al., Citation2019) and Norway (Kaltenborn et al., Citation2020), and nature-based tourism in Sweden (Nikodinoska et al., Citation2015) and Canada (Erickson, Citation2021). Such state of coverage indicates that adaptation research has not equally evolved around the regions and for different tourism types, and, that, while some areas and sectors can still require an initial assessment of potential risks, other may already be at a level of improving their current adaptation efforts.

Carbon risk

Estimations of and responses to the carbon risks of tourism in the polar regions has scholarly been less covered, despite the widespread general decarbonization ambition of the polar nations (UNFCCC., Citation2024). Regarding the most up-to-date estimations since the release of the AR5, there are only a few national scale studies on Iceland (Saviolidis et al., Citation2021; Sharp et al., Citation2016), as well as its outbound tourism (Czepkiewicz et al., Citation2019), a black carbon analysis for Antarctic tourism (Cordero et al., Citation2022), and a carbon footprint study for Finnish second home tourism (Adamiak et al., Citation2016) - and another one from a non-Arctic region of Finland (Koivula & Tuominen, Citation2019). The Icelandic analyses have assessed an average inbound tourist’s carbon footprint as 1.35 tCO2e in 2013, with the total tourism emissions jumping from 600,000 tCO2e in 2010 to 1,800,000 tCO2e in 2015 (Sharp et al., Citation2016), and a young Reykjavik resident’s outbound footprint in 2017 as 2.96 tCO2e against much lower emissions resulting from local (1.08 tCO2e per capita) and domestic (0.45 tCO2e per capita) trips (Czepkiewicz et al., Citation2019). In the Finnish case, an average household’s leisure footprint was estimated as 1.09 tCO2e for outbound tourism, 0.27 tCO2e for domestic second home tourism and 0.18 tCO2e for other domestic tourism for the year 2012 (Adamiak et al., Citation2016). In the case of the Antarctic (Cordero et al., Citation2022), black carbon concentration has been found to be relatively higher at the popular cruise spots and the Union Glacier, which also hosts a runway, causing negative effects on the snow cover and its albedo.

On the mitigation side, most recent studies have focused on the “myth” of polar tourism to promote pro-environmental behavior. Font and Hindley (Citation2017) and Hindley and Font (Citation2017, Citation2018) highlight the psychological complexities behind achieving pro-environmental transformations among last chance tourists to Svalbard, Johnston et al. (Citation2014) show that a student trip to the Antarctic has had almost no influence on their environmental behavior, and Árnadóttir et al. (Citation2021) survey with Icelanders illustrates how physical geography can be a major determinant of air travel dependency, and a high footprint, even if people have high awareness. Groulx et al. (Citation2019) and Miller et al. (Citation2020), on the other hand, show positive pro-environmental outcomes of last chance tourism among polar bear tourists to Churchill and Alaska, especially at the presence of place bonding or onsite education. These studies also link back to the last chance tourism paradox debates covered in the Climate Risk section, as, besides failures in transformations towards visitors’ climate-friendliness, additional emissions are also contributed through the rather long-haul trips needed for polar tourism.

Discussion and conclusions

Whilst the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) has improved its spatial coverage of tourism issues, compared to that of the AR5 (Scott et al., Citation2015), still some regions have been less included and destination-specific vulnerabilities as well as tourism’s contribution the global carbon footprint have received limited discussions (Scott et al., Citation2023). As emphasized by Scott et al. (Citation2023); “(w)ith only 21% of published climate change and tourism literature in the AR6 review period cited, tourism academics should elevate tourism content and engagement in future assessments.” Accordingly, this study presented an update of Demiroglu and Hall (Citation2020) review on tourism and climate change in the polar regions, focusing on the latest research since the release of the AR5 and inclusive of the studies besides the Anglophone articles. The review concluded that the climate risk, rather than the carbon risk, of polar tourism is much widely covered by the literature, and more studies emerge at the intersections of these two risk categories, indicating the complexities and the significance of the adaptation-mitigation interplays. The amount of integrated impact assessments was also quite high, yet some impact types relevant to the region, such as extreme weather (e.g. at a time when Arctic cyclones and cruise tourism are expected to rise), sea-level rise and coastal change, biodiversity change (e.g. at the presence of iconic animals such as the polar bear and the penguin), oceanic changes, human health risks, and even social disruptions (at a time where tourism will need to co-exist with an ever-growing climate mobility in general), and their adaptations were barely covered.

On the carbon risk side, there was very little emission estimation studies across all scales and scopes (Gössling et al., Citation2023), and the need for a consensus on tourism’s carbon accounting methodologies largely remains for a better understanding of its footprint and mitigation urgencies (UNWTO, Citation2023). Our review also pointed out a certain lack of research on decarbonization in terms of technological advancements and policies, the latter of which is also reflected in the NDCs of the polar nations. These highest-level, yet limited or non-existing, commitments in the tourism context are also a major gap from a climate risk perspective for the polar nations, except partially for Chile and Argentina, despite tourism being one of the key economic sectors for adaptation priority according to a global assessment of the 164 NDCs by the UNFCCC (Citation2021). The supranational governance and the extra-continental system of Antarctic tourism makes such policy needs even more challenging, with almost no coverage of tourism vulnerabilities under the Helsinki Declaration (Antarctic Treaty, Citation2023).

Regarding regional coverage, besides the need for destination and tourism sub-sector specific studies, some polar nations are almost completely missing from the post-AR5 climate change and tourism literature. While this may be due to the relatively less polar relevance in terms of the tourism offer, some may be lacking the capacity to yield research. For instance, the reason for a minimal coverage on Sweden could be due to its relatively less polar attractivity, despite the country’s recent Arctification efforts and trends including the tourism industry (Marjavaara et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, the almost non-existing research for the Faroe Islands could be due to its own limited scholarship capacity, but its physically and socioeconomically climate-vulnerable position and fossil-intensive air/sea-based touristic accessibility call for research and outreach. Likewise, although recently emerging and relatively small-scale (Boekstein, Citation2014), South African gateways to the Antarctic also need further academic attention, especially given the carbon risks.

As for the geobibliography methodology used in this study, more standards, especially in terms of the “spatialization” challenges, need to be introduced to ease a universal adoption. The POLTOUR app, on the other hand, will be collaboratively updated as new research arrives and upgraded in line with the rapidly evolving technologies in GIS and AI, the latter of which can also help serve with a more enhanced and seamless survey on the research domain. Moreover the experience design is to be improved for a broader user typology beyond the research community. In this respect, the VR component will be one main focus to better serve for edutainment to the wider public. Ultimately, the tool is intended for the use of academic research as well as to benefit the policymakers and businesses in exploring comparative cases of climate change risks and taking on sustainable development actions that can help all components of the tourism system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, Z., Hoogendoorn, G., & Fitchett, J. M. (2022). Glacier tourism and tourist reviews: An experiential engagement with the concept of “Last Chance Tourism”. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1974545

- Adamiak, C., Hall, C. M., Hiltunen, M. J., & Pitkänen, K. (2016). Substitute or addition to hypermobile lifestyles? Second home mobility and Finnish CO2 emissions. Tourism Geographies, 18(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1145250

- Adventure Green Alaska. (2018). Climate change audit example. https://www.adventuregreenalaska.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/climate-change-audit-example.pdf

- Albarillo, F. (2014). Language in social science databases: English versus non-English articles in JSTOR and Scopus. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 33(2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2014.904693

- Althingi. (2011). Tourism strategy for 2011-2020. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/en/about-us/icelandic-tourist-board/tourism-strategy-2011-2020#tourism-strategy-for-20112020

- Antarctic Treaty. (2023). Helsinki declaration on climate change and the Antarctic. https://um.fi/current-affairs/-/asset_publisher/gc654PySnjTX/content/helsinki-declaration-on-climate-change-and-the-antarctic

- Árnadóttir, Á., Czepkiewicz, M., & Heinonen, J. (2021). Climate change concern and the desire to travel: How do I justify my flights? Travel Behaviour and Society, 24, 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2021.05.002

- ATIA. (2020). Alaska visitor volume report. https://www.alaskatia.org/wp-content/uploads/Alaska-Visitor-Volume-2018-19-FINAL-7_1_20.pdf

- Becken, S. (2013). A review of tourism and climate change as an evolving knowledge domain. Tourism Management Perspectives, 6, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.11.006

- Boekstein, M. (2014). Cape Town as Africa’s gateway for tourism to Antarctica – Development potential and need for regulation. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3(2), 1-9. http://www.ajhtl.com/uploads/7/1/6/3/7163688/article_14_vol.3_2_july_2014.pdf

- Bystrowska, M. (2019). The impact of sea ice on cruise tourism on Svalbard. ARCTIC, 72(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic68320

- Cordero, R. R., Sepúlveda, E., Feron, S., Damiani, A., Fernandoy, F., Neshyba, S., Rowe, P. M., Asencio, V., Carrasco, J., Alfonso, J. A., Llanillo, P., Wachter, P., Seckmeyer, G., Stepanova, M., Carrera, J. M., Jorquera, J., Wang, C., Malhotra, A., Dana, J., Khan, A. L., & Casassa, G. (2022). Black carbon footprint of human presence in Antarctica. Nature Communications, 13(1), 984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28560-w

- Czepkiewicz, M., Árnadóttir, Á., & Heinonen, J. (2019). Flights dominate travel emissions of young urbanites. Sustainability, 11(22), 6340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226340

- Dannevig, H., Gildestad, I. M., Steiger, R., & Scott, D. (2021). Adaptive capacity of ski resorts in western norway to projected changes in snow conditions. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(22), 3206–3221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1865286

- Dawson, J., Johnston, M. E., & Stewart, E. J. (2014). Governance of Arctic expedition cruise ships in a time of rapid environmental and economic change. Ocean & Coastal Management, 89, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.12.005

- Dawson, J., Stewart, E. J., Johnston, M. E., & Lemieux, C. J. (2016). Identifying and evaluating adaptation strategies for cruise tourism in Arctic Canada. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(10), 1425–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1125358

- Day, J. J., & Hodges, K. I. (2018). Growing land-sea temperature contrast and the intensification of Arctic cyclones. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(8), 3673–3681. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL077587

- Demiroglu, O. C., Dannevig, H., & Aall, C. (2013). The multidisciplinary literature of ski tourism and climate change. In M. Kozak & N. Kozak (Eds.), Tourism research: An interdisciplinary perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Demiroglu, O. C., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Geobibliography and bibliometric networks of polar tourism and climate change research. Atmosphere, 11(5), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11050498

- Denstadli, J. M., & Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2014). More clouds on the horizon? Polar tourists’ weather tolerances in the context of climate change. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(1), 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.886096

- Dodds, R., & Graci, S. (2009). Canada’s tourism industry- Mitigating the effects of climate change: A lot of concern but little action. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 6(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530902847046

- Dodds, K., & Salazar, J. F. (2021). Gateway geopolitics: Assembling infrastructure, policies, and tourism in Hobart and Australian Antarctic Territory/East Antarctica. In M. Mostafanezhad, M. C. Azcárate & R. Norum (Eds.), Tourism geopolitics: Assemblages of infrastructure, affect, and imagination (pp. 351–375). University of Arizona Press.

- Dong, E., Du, H., & Gardner, L. (2020). An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The LANCET: Infectious Diseases, 20(5), 533–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1

- Dube, K., Nhamo, G., Kilungu, H., Hambira, W. L., El-Masry, E. A., Chikodzi, D., Chapungu, L., & Molua, E. L. (2023). Tourism and climate change in Africa: Informing sector responses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2193357

- Dunn, M. J., Forcada, J., Jackson, J. A., Waluda, C. M., Nichol, C., & Trathan, P. N. (2019). A long-term study of gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua) population trends at a major Antarctic tourist site, Goudier Island, Port Lockroy. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1635-6

- Erickson, B. (2021). The neoliberal tourist: Affect, policy and economy in the Canadian north. ACME, 20(1), 58–80.

- Fang, Y., Trupp, A., Hess, J. S., & Ma, S. (2022). Tourism under climate crisis in Asia: Impacts and implications. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2112204

- Font, X., & Hindley, A. (2017). Understanding tourists’ reactance to the threat of a loss of freedom to travel due to climate change: A new alternative approach to encouraging nuanced behavioural change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1165235

- Fu, P. (2022). Getting to know Web GIS. Esri Press.

- Gaigg, M. (2023). Designing map interfaces: Patterns for building effective map apps. Esri Press.

- Gössling, S., Balas, M., Mayer, M., & Sun, Y.-Y. (2023). A review of tourism and climate change mitigation: The scales, scopes, stakeholders and strategies of carbon management. Tourism Management, 95, 104681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104681

- Government of Canada. (2023). Federal tourism growth strategy. https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/canadian-tourism-sector/en/canada-365-welcoming-world-every-day-federal-tourism-growth-strategy

- Gren, M., & Huijbens, E. H. (2014). Tourism and the anthropocene. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.886100

- Groulx, M., Boluk, K., Lemieux, C. J., & Dawson, J. (2019). Place stewardship among last chance tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.01.008

- Hall, C. M. (2014). Will climate change kill Santa Claus? Climate change and high-latitude Christmas place branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.886101

- Higham, J., Loehr, J., Hopkins, D., Becken, S., & Stovall, W. (2022). Climate science and tourism policy in Australasia: Deficiencies in science-policy translation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2134882

- Hindley, A., & Font, X. (2017). Ethics and influences in tourist perceptions of climate change. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(16), 1684–1700. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.946477

- Hindley, A., & Font, X. (2018). Values and motivations in tourist perceptions of last-chance tourism. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415619674

- Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, D., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., Ren, C., Pan, T., Chu, Z., & Chen, Y. (2021). Spatial-temporal characteristics of Arctic summer climate comfort level in the context of regional tourism resources from 1979 to 2019. Sustainability, 13(23), 13056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313056

- Icelandic Tourism Board. (2021). Tourism in Iceland in Figures. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/en/recearch-and-statistics/tourism-in-iceland-in-figures

- Innovation Norway. (2021). Nasjonal Reiselivsstrategi 2030: Fra reiselivet. Til regjeringen. https://assets.simpleviewcms.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/norway/Nasjonal_Reiselivsstrategi_2021_1__2a784ce5-7b8f-438d-a40b-65a68707dff5.pdf

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (2023). The federal tourism growth strategy. https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/canadian-tourism-sector/en/canada-365-welcoming-world-every-day-federal-tourism-growth-strategy

- International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. (2022). IAATO overview of antarctic tourism: A historical review of growth, the 2021-22 season, and preliminary estimates for 2022-23. https://iaato.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ATCM44-IAATO-Overview.pdf

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2022a). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2022b). Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Iturbide, M., et al. (2020). An update of IPCC climate reference regions for subcontinental analysis of climate model data: Definition and aggregated datasets. ESSD, 12, 2959–2970.

- Jensen, M., Vereda, M., Vereda, M., Sánchez, R. A., & Roura, R. (2016). The origins and development of Antarctic tourism through Ushuaia as a gateway port. In: M. Schillat; M. Jensen (Eds.), Tourism in Antarctica (pp. 75–99). Springer.

- Johnston, M. E., Dawson, J., Childs, J., & Maher, P. T. (2014). Exploring post-course outcomes of an undergraduate tourism field trip to the Antarctic Peninsula. Polar Record, 50(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224741300003X

- Johnston, M. E., Dawson, J., De Souza, E., & Stewart, E. J. (2017a). Management challenges for the fastest growing marine shipping sector in Arctic Canada: Pleasure crafts. Polar Record, 53(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247416000565

- Johnston, M. E., Dawson, J., & Maher, P. T. (2017b). Strategic development challenges in marine tourism in Nunavut. Resources, 6(3), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6030025

- Kaján, E. (2014). Community perceptions to place attachment and tourism development in Finnish Lapland. Tourism Geographies, 16(3), 490–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.941916

- Kaltenborn, B. P., Østreng, W., & Hovelsrud, G. K. (2020). Change will be the constant–future environmental policy and governance challenges in Svalbard. Polar Geography, 20(1), 25–45.

- Klein, R., Adams, K. M., Dzebo, A., Davis, M., & Siebert, C. K. (2017). Advancing climate adaptation practices and solutions: Emerging research priorities. Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Koivula, E., & Tuominen, R. (2019). Etelä-Savon matkailun hiilijalanjälki - kohti vastuullista matkailua. XAMK KEHITTÄÄ 76 KAAKKOIS-SUOMEN AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU MIKKELI.

- Lamers, M., Duske, P., & van Bets, L. (2018). Understanding user needs: A practice-based approach to exploring the role of weather and sea ice services in European Arctic expedition cruising. Polar Geography, 41(4), 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2018.1513959

- Lépy, É., Heikkinen, H. I., Karjalainen, T. P., Tervo-Kankare, K., Kauppila, P., Suopajärvi, T., Ponnikas, J., Siikamäki, P., & Rautio, A. (2014). Multidisciplinary and participatory approach for assessing local vulnerability of tourism industry to climate change. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.886373

- Lépy, É., Rantala, S., Huusko, A., Nieminen, P., Hippi, M., & Rautio, A. (2016). Role of winter weather conditions and slipperiness on tourists’ accidents in Finland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(8), 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13080822

- Liggett, D., Frame, B., Gilbert, N., & Morgan, F. (2017). Is it all going south? Four future scenarios for Antarctica. Polar Record, 53(5), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247417000390

- Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Ali, F. (2022). Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how to contribute’. The Service Industries Journal, Taylor & Francis Journals, 42(7-8), 481–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2047941

- Maher, P. T., Gelter, H., Hillmer-Pegram, K., Hovgaard, G., Hull, J., Jóhannesson, G. Þ., Karlsdóttir, A., Rantala, O., & Pashkevich, A. (2014). Arctic tourism: Realities and possibilities. In Arctic yearbook (pp. 290–306). Arctic Portal.

- Marjavaara, R., Nilsson, R. O., & Müller, D. K. (2022). The Arctification of northern tourism: A longitudinal geographical analysis of firm names in Sweden. Polar Geography, 45(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2022.2032449

- Meredith, M., Sommerkorn, M., Cassotta, S., Derksen, C., Ekaykin, A., Hollowed, A., Kofinas, G., Mackintosh, A., Melbourne-Thomas, J., Muelbert, M. M. C., et al. (2019). Polar regions. In IPCC special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, L. B., Hallo, J. C., Dvorak, R. G., Fefer, J. P., Peterson, B. A., & Brownlee, M. T. J. (2020). On the edge of the world: Examining pro-environmental outcomes of last chance tourism in Kaktovik, Alaska. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1703–1722. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1720696

- Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East and Arctic. (2020). The Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East and the Arctic sets a goal to increase tourist flow in the Arctic to 3 million people a year in 15 years. https://minvr.gov.ru/press-center/news/25374/

- Ministry of Industries and Innovation & the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. (2015). Road map for tourism in Iceland. https://www.stjornarradid.is/media/atvinnuvegaraduneyti-media/media/Acrobat/Road-Map-for-Tourism-in-Iceland.pdf

- Ministry of Industries and Innovation. (2019). Framtíðarsýn ferðaþjónustunnar Leiðandi í sjálfbærri þróun. https://www.stjornarradid.is/library/01–Frettatengt–-myndir-og-skrar/ANR/FerdaThjonusta/Kynning_R%c3%a1%c3%b0herra_Efla.pdf

- Navarro-Drazich, D., Christel, L. G., Gerique, A., Grimm, I., Rendón, M.-L., Schlemer Alcântara, L., Abraham, Y., del Rosario Conde, M., & De Simón, C. (2023). Climate change and tourism in South and Central America. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2210783

- Nikodinoska, N., Paletto, A., Franzese, P. P., & Jonasson, C. (2015). Valuation of ecosystem services in protected areas: The case of the Abisko National Park (Sweden). Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management, 3(4), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.5890/JEAM.2015.11.005

- Olsen, J., Carter, N. A., & Dawson, J. (2019). Community perspectives on the environmental impacts of Arctic shipping: Case studies from Russia, Norway and Canada. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1609189

- Palma, D., Varnajot, A., Dalen, K., Basaran, I. K., Brunette, C., Bystrowska, M., Korablina, A. D., Nowicki, R. C., & Ronge, T. A. (2019). Cruising the marginal ice zone: Climate change and Arctic tourism. Polar Geography, 42(4), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1648585

- Petry, M. V., Valls, F. C. L., Petersen, E. S., Krüger, L., Piuco, R. C., & dos Santos, C. R. (2016). Breeding sites and population of seabirds on Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. Polar Biology, 39(7), 1343–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-015-1846-1

- PKF. (2013). Promote Iceland: Long-term strategy for the Icelandic tourism industry. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/research/files/final-long-term-strategy-for-icelandic-tourism-industry.pdf

- Qu, J., Villumsen, A., & Villumsen, O. (2015). Challenges to sustainable Arctic tourist lodging: A proposed solution for Greenland. Polar Record, 51(5), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247414000734

- Rantanen, M., Karpechko, A. Y., Lipponen, A., Nordling, K., Hyvärinen, O., Ruosteenoja, K., Vihma, T., & Laaksonen, A. (2022). The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Communications Earth & Environment, 3(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3

- Raya Rey, A., Rosciano, N., Liljesthröm, M., Sáenz Samaniego, R., & Schiavini, A. (2014). Species-specific population trends detected for penguins, gulls and cormorants over 20 years in sub-Antarctic Fuegian Archipelago. Polar Biology, 37(9), 1343–1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-014-1526-6

- Regeringskansliet. (2021). Strategi för hållbar turism och växande besöksnäring. https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2021/10/strategi-for-hallbar-turism-och-vaxande-besoksnaring/

- Rode, K. D., Fortin-Noreus, J. K., Garshelis, D., Dyck, M., Sahanatien, V., Atwood, T., Belikov, S., Laidre, K. L., Miller, S., Obbard, M. E., Vongraven, D., Ware, J., & Wilder, J. (2018). Survey-based assessment of the frequency and potential impacts of recreation on polar bears. Biological Conservation, 227, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.09.008

- Russian Government. (2020). Decree of the President of the Russian Federation "On the Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and Ensuring National Security for the Period until 2035. http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/45972

- Rutty, M., Hewer, M., Knowles, N., & Ma, S. (2022). Tourism & climate change in North America: Regional state of knowledge. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2127742

- Sarvut, T. (2018). Constructive basis for the development of the extreme zones of Siberia and the Russian arctic. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(2.13), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i2.13.11602

- Saviolidis, N. M., Cook, D., Davíðsdóttir, B., Jóhannsdóttir, L., & Ólafsson, S. (2021). Challenges of national measurement of environmental sustainability in tourism. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 3, 100079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100079

- Schrot, O. G., Christensen, J. H., & Formayer, H. (2019). Greenland winter tourism in a changing climate. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 27, 100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2019.100224

- Scott, D., Hall, C. M., & Gössling, S. (2015). A review of the IPCC Fifth Assessment and implications for tourism sector climate resilience and decarbonization. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1062021

- Scott, D., Hall, C. M., Rushton, B., & Gössling, S. (2023). A review of the IPCC Sixth Assessment and implications for tourism development and sectoral climate action. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2195597

- Scott, D., Steiger, R., Dannevig, H., & Aall, C. (2020). Climate change and the future of the Norwegian alpine ski industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(19), 2396–2409. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1608919

- Sharp, H., Grundius, J., & Heinonen, J. (2016). Carbon footprint of inbound tourism to Iceland: A consumption-based life-cycle assessment including direct and indirect emissions. Sustainability, 8(11), 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8111147

- Sisneros-Kidd, A. M., Monz, C., Hausner, V., Schmidt, J., & Clark, D. (2019). Nature-based tourism, resource dependence, and resilience of Arctic communities: Framing complex issues in a changing environment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(8), 1259–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1612905

- Statistics Finland. (2024). Transport and tourism. https://www.stat.fi/til/lii_en.html

- Statistics Norway. (2024). 14172: Guest nights, by contents, region, type of accommodation, month and country of residence. https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/14172/tableViewLayout1/

- Steiger, R., Demiroglu, O. C., Pons, M., & Salim, E. (2023). Climate and carbon risk of tourism in Europe. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2163653

- Stewart, E. J., Dawson, J., & Johnston, M. E. (2015). Risks and opportunities associated with change in the cruise tourism sector: Community perspectives from Arctic Canada. The Polar Journal, 5(2), 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2015.1082283

- Stewart, E. J., Liggett, D., & Dawson, J. (2017). The evolution of polar tourism scholarship: Research themes, networks and agendas. Polar Geography, 40(1), 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1274789

- TASS. (2024). Турпоток в Арктику превысил 1 млн человек в 2023 году. https://tass.ru/ekonomika/19806467

- Tervo-Kankare, K., Kaján, E., & Saarinen, J. (2018). Costs and benefits of environmental change: Tourism industry’s responses in Arctic Finland. Tourism Geographies, 20(2), 202–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1375973

- Teryutina, M. M. (2021). Development of tourism in the Arctic against the background of climate change: What are the prospects for the “arctic hectare”. Agrarian Science, 346(3), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.32634/0869-8155-2021-346-3-107-112

- Tolvanen, A., & Kangas, K. (2016). Tourism, biodiversity and protected areas - Review from northern Fennoscandia. J. Environ. Manage, 169, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.12.011

- UNFCCC. (2021). NDC synthesis report. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/ndc-synthesis-report

- UNFCCC. (2024). NDC registry. https://unfccc.int/NDCREG

- UNRIC. (2023). Greenland signs up for Paris Agreement. https://unric.org/en/greenland-signs-up-for-paris-agreement/

- UNWTO. (2023). Climate Action in the Tourism Sector – An overview of methodologies and tools to measure greenhouse gas emissions. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284423927

- Varnajot, A., Makanse, Y., Huijbens, E. H., & Lamers, M. (2024). Toward Antarctification? Tourism and place-making in Antarctica. Polar Geography, 47(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2024.2309673

- Vila, M., Costa, G., Angulo-Preckler, C., Sarda, R., & Avila, C. (2016). Contrasting views on Antarctic tourism: ‘last chance tourism’ or ‘ambassadorship’ in the last of the wild. Journal of Cleaner Production, 111, 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.061

- Visit Faroe Islands. (2019). Join the Preservolution! A sustainable tourism development strategy for the Faroe Islands towards 2025. https://www.visitfaroeislands.com/content/uploads/2019/03/vfi_strategifaldariuk100dpispread.pdf

- Visit Faroe Islands. (2023). HEIM: Tourism strategy towards 2030. https://issuu.com/visitfaroeislands/docs/vfi-magasin-a4-en-spread

- Visit Finland. (2019). Sustainable travel Finland. https://www.visitfinland.fi/en/liiketoiminnan-kehittaminen/vastuullinen-matkailu/sustainable-travel-finland

- Visit Greenland. (2021). Towards more tourism. Visit Greenland’s marketing and market development strategy 2021-2024. https://traveltrade.visitgreenland.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Strategi-EN-feb2021.pdf

- Welling, J., & Abegg, B. (2021). Following the ice: Adaptation processes of glacier tour operators in Southeast Iceland. International Journal of Biometeorology, 65(5), 703–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-019-01779-x

- Welling, J., Árnason, Þ., & Ólafsdóttir, R. (2020). Implications of climate change on nature-based tourism demand: A segmentation analysis of glacier site visitors in southeast Iceland. Sustainability, 12(13), 5338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135338

- Welling, J., Ólafsdóttir, R., Árnason, Þ., & Guðmundsson, S. (2019). Participatory planning under scenarios of glacier retreat and tourism growth in southeast Iceland. Mountain Research and Development, 39(2), D1–D13. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-18-00090.1

- White House. (2022). National strategy for the arctic region. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Strategy-for-the-Arctic-Region.pdf

- Wolf, F., Moncada, S., Surroop, D., Shah, K. U., Raghoo, P., Scherle, N., Reiser, D., Telesford, J. N., Roberts, S., Hausia Havea, P., Naidu, R., & Nguyen, L. (2022). Small island developing states, tourism and climate change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2112203