ABSTRACT

Inclusive kindergarten provision remains relatively rare in Indonesia. This article indicates factors that contribute to this situation (stigmatisation, lack of resources and training) and reports on an approach to begin to address it. Sign Supported Big Books were evaluated in mainstream kindergartens (i.e. classes without children with special educational needs) as a way of enhancing their inclusive affordances. These books used Signalong Indonesia, a keyword signing approach, to support whole class stories with 76 children in five kindergarten classes. Four classes used books with signs and one used a book without signs as part of their everyday activities. Five teacher interviews suggested that the approach enhanced pupils’ engagement and was enjoyable and fun for pupils and teachers alike. There were also positive effects for children's story comprehension and sign learning. The findings of this study support the novel position that having a disabled child in a class is not necessary in order to justify using an inclusive keyword signing approach. The implications of these findings are discussed for developing a proactive approach to facilitate inclusive practices in Indonesian kindergartens.

Introduction

Inclusive education in Indonesia

The development of an inclusive education system across Indonesia is a particularly challenging social project. With a national motto of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (‘unity in diversity’), Indonesia is the world's largest archipelagic country with more than 17, 524 islands, and a population of over 270 million people who form the world's most diverse multi-ethnic state. The Indonesian government has made a commitment that all children across the nation will have at least nine years of education (Ramos-Mattoussi and Milligan Citation2013) and, as part of this commitment, has mandated the creation of inclusive primary schools within each school district (Sunardi et al. Citation2011). Indonesian schools have been described in terms of three categories mainstream, special and inclusive (Aprilia Citation2017). Mainstream (also called regular) schools typically do not admit children with special educational needs. Traditionally, these children could attend special schools (Sekolah Luar Biasa) that cater for specific disability categories such as physical impairment or deafness. In the last two decades, inclusive schools have developed that aim to accommodate all learners (Aprilia Citation2017; Sheehy and Budiyanto Citation2015). The development of these inclusive schools has opened up access to education for children who would previously been excluded from education, most notably those with severe intellectual or communication difficulties (Suwaryani Citation2008; Budiyanto, Kaye, and Rofiah Citation2020).

The importance of kindergartens, for children aged between 4 and 6 years of age, in facilitating, and underpinning, a national system of inclusive education has been identified by Indonesian policy makers and educationalists (Ediyanto et al. Citation2017). However whilst there has been a steady growth of inclusive primary and secondary schools (Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017), this growth has not been mirrored by kindergarten provision, which remains rare (Poernomo Citation2016). This apparent deficit in provision is significant given the positive impact that kindergarten and preschool settings can have on children's development (Jenkins et al. Citation2018). Kindergartens can also act as sites for initiating an inclusive cultural shift (Raičević Citation2020).

Inclusive Indonesian Classrooms project

The Inclusive Indonesian Classrooms project is an ongoing collaboration between Universitas Negeri Surabaya (UNESA, the State University of Surabaya, Indonesia) and the Open University, United Kingdom. It aims to develop teaching approaches and pedagogical strategies that facilitate inclusive teaching and enable positive social and educational outcomes for all learners (Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017). The project developed a keyword signing (KWS) approach, Signalong Indonesia (SI), to support this aim. It uses manual signs to highlight the keywords in a spoken sentence and, unlike the signed languages of Deaf communities, follows the word order of speech. In this way, it offers a free and accessible way to support full class communication through Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian Language) (see Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017, for details). It has become widely used (Budiyanto, Kaye, and Rofiah Citation2020) and grown through iterative developments in response to teacher feedback and research. These changes have included moving towards an emphasis on a lesson study training approach and embedding Signalong Indonesia within UNESA's teacher training and outreach programmes.

One emerging issue has been the importance of, and challenges in, supporting inclusive practice in kindergartens. Our project has identified three factors that impact upon access to inclusive kindergarten provision:

One factor is the extensive stigmatisation of children with disabilities or special educational needs in Indonesia (Handoyo et al. Citation2018; Sheehy and Budiyanto Citation2014), a stigma which can also be applied to those who teach these children (Budiyanto, Kaye, and Rofiah Citation2020). Part of this stigmatisation is a belief that disabled children in kindergartens, in particular those with learning disabilities, will ‘ hinder the development of other normal children’ (Anggia and Harun Citation2019, 181). This contributes to a situation in which kindergartens will not necessarily admit disabled children and where even designated inclusive kindergartens will severely limit their acceptance of children with special educational needs or disabilities (Sabila and Kurniawati Citation2019).

A second factor concerns a lack of research evidence that evaluates the efficacy of ‘practical’ inclusive educational approaches within Indonesian kindergartens, and which might inform the practice of Indonesia educators and teacher trainers (Kristiana and Hendriani Citation2018).

Thirdly, teachers can feel ill-prepared, and unwilling, to teach children with special educational needs because they have not been specifically trained to teach this group of children (Rix et al. Citation2013; Sheehy et al. Citation2017), or feel that they lack the necessary classroom resources to do so (Diana, Gunarhadi, and Yusuf Citation2020).

These factors combine to create a situation that we have termed the ‘Kindergarten Catch 22’. In the novel Catch 22 (Heller Citation1961) Heller describes paradoxical situations in which the apparent solution to a problem actually prevents the solution from occurring. Kindergartens might not have any children with special educational needs. Therefore, they do not need to train in inclusive teaching approaches or buy associated resources. When a child with special educational needs applies to the kindergarten, they can be refused because the kindergarten indicates that they do not have the skills or resources to teach them. The paradox is that kindergartens do not train or buy resources because they have no pupils with special educational needs. They have no pupils with special educational needs because they do not have the resources or training. Furthermore, this act of refusal is negatively reinforced. This happens when a particular response removes an unpleasant event or situation. This makes it more likely this response will be repeated in future (Mitchell Citation2020). In the kindergarten context, the feared ‘damage’ to other children's education has been prevented, making refusal of entry more likely to occur subsequently. If a child with special educational needs is admitted, the existing classroom practices might not support them, making the child's ‘inclusion’ more likely to be unsuccessful. Whilst each of these beliefs might be robustly critiqued (Rix Citation2015), there remains a need for a pragmatic, practical response that can support both children and their teachers. The focus of this paper is the evaluation of a pilot of such an approach. It aimed to pilot a potential proactive approach as the first step in addressing Indonesia's ‘Kindergarten Catch 22’ situation.

Following discussions with teachers and teacher educators attending the 3rd International Conference on Special Education the notion of getting inclusive teaching approaches established as everyday kindergarten activities was debated i.e. having the resources and practices in place before children with special educational needs applied to enrol. One proposed ‘everyday activity’ was that of storytelling and so we sought to find ways of making this an activity with more inclusive potential.

The project's working definition of inclusive teaching is something that extends

… . what is ordinarily available in the community of the classroom as a way of reducing the need to mark some learners as different. [an approach ] providing rich learning opportunities that are sufficiently made available for everyone, so that all learners are able to participate in classroom life.

(Florian and Black-Hawkins Citation2011, 826)

The use of ‘Big Books’ appeared to have merit for supporting an inclusive pedagogy. A Big Book is large story book, with large attractive illustrations. Commonly used in early years settings, they are typically around 34×42 cm. These books can be used to support an interactive dialogic form of storytelling (Yaacob and Pinter Citation2008; Lever and Sénéchal Citation2011), and can be an effective way of gaining the engagement of young learners and developing their language and comprehension skills (Colville-Hall and O’Connor Citation2006; Jayendra, Nitiasih, and Mahayanti Citation2018). The benefits of Signalong Indonesia in supporting inclusive teaching have been identified in previous research (Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017; Jauhari Citation2017), primarily through allowing all members of the class to engage with a pedagogy that is social in nature (Sheehy et al. Citation2009). There seemed to be a complementarity between the Big Book and Keyword Signing approaches which we sought to exploit.

There is little research on the use of keyword signing in mainstream classes. One rare evaluation examined the attitudes of 6-year-old pupils (without special educational needs) to using Lámh, an Irish keyword signing approach. This study by Bowles and Frizelle (Citation2016) found that all children had a positive attitude towards using this type of signing (Bowles and Frizelle Citation2016). Mistry and Barnes (Citation2012) evaluated the use of Makaton, a UK keyword sign approach, to support reception class children (approximately 5 years of age), many of whom had English as an Additional Language (EAL). They found a positive correlation between the use of keyword signing and use of spoken English (Mistry and Barnes Citation2012). To date, only one study has explored keyword signing together with storytelling, albeit outside a mainstream setting. This was a small-scale study with three carers, using Makaton to support multi-sensory stories at an after-school club. It recorded how the carers used signs with stories over a six-week period. Although this study involved the teaching of children with learning disabilities (age 5–10 years) exclusively, it concluded that storytelling and keyword signing were ‘mutually supportive’ (Bednarski Citation2016, 23). Therefore, there seemed to be some indirect evidence to suggest that Signalong Indonesia could be beneficial to learners in a mainstream class, that it might work well with Big Book storytelling, and that young children would enjoy using it.

The current study was the first to examine the use of keyword signing to support Big Book storytelling with mainstream kindergarten children. It sought to gather teachers’ experience of using Sign Supported Big Books (SSBB) in their kindergartens and examine the effects of this approach on children's learning.

Method

Participants

Ten schools within the Greater Surabaya area, East Java, were sent details of the project, which resulted in five female kindergarten teachers (from five schools) volunteering to take part in the study. The average class size was 15 children, with 76 children in total taking part.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from all teachers and parents of children in each class, and all data was securely stored. Children are not legally able to give informed consent until they are 18 years of age and international guidelines concur that children should therefore give their assent, in addition to the consent of their parents or guardians (Baines Citation2011). Assent allows young children to take part in research activities from which they might otherwise be excluded (Brady and Shaw Citation2012). Consequently, although the research was an everyday activity and the type of questions would be familiar to the children, the researchers took care to monitor the children's ongoing assent. If a child indicated an unwillingness or discomfort the research would stop.

The research was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the Educational Research Ethics Committee, Fakultas Pendidikan, Universities Negeri Surabaya.

Materials

A Big Book storybook was created by the research team. This featured the tale of a boy called Roni, who visits a market to buy eggs and chickens (See ).

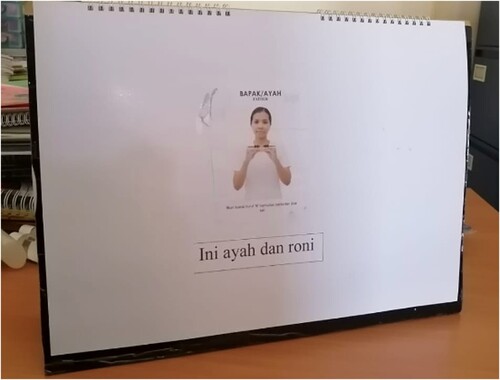

The Big Book format is used in some Indonesian kindergartens where teachers typically adapt books from overseas that are in a non-Indonesian language. In this study, the Big Book's story and language were created to explicitly reflect situations with which the children would be familiar, namely visiting a local market. Each page of the book consisted of a large illustrative picture on one side, with the story text across the bottom in a large font. The other side of the page contained the story text plus a keyword illustration. In keeping with Signalong Indonesia's keyword signing method, a single sign was selected for each page of the story. The sentences are very short and each keyword related to the focus of each sentence. This was illustrated on the back of the picture page, so that the teacher could be reminded of it when reading the story (see ).

Figure 2. A keyword sign on the back of a Big Book story page. The text ‘ini ayah dan roni’ (this is Father and Roni) is supported with the Signalong Indonesia sign ‘Ayah’ (Father).

Design

Four teachers used the Sign Supported book (SSBB) and one teacher used the book alone without sign support (BA), to allow a comparison to be made between the two experiences.

Researchers interviewed the teachers and the children in each class. After the data were collected the teachers attended a ‘debriefing’ workshop to share their experiences and observations with the team.

Teacher interviews

The interview approach was semi-structured in nature (Adams and Cox Citation2008) and conducted in Bahasa Indonesia. The interviews began with four general questions:

What was your experience of teaching young children using Signalong Indonesia?

Do you feel this approach changed or influenced the way you teach?

Do you like using Signalong Indonesia in your teaching?

Did you find any difficulties in using Signalong Indonesia?

The discussions that arose from these questions were informal and issues raised by the teachers were explored in keeping with a non-directive interview technique. However, a series of prompts were also used (derived from Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017), if these topics were not raised by teachers. These prompts were:

What are your suggestions for developing Signalong Indonesia in the future?

Does Signalong Indonesia make learning [more] fun?

Does Signalong Indonesia make it easier for students to understand stories?

Does Signalong Indonesia make students remember the contents of the story faster?

Anything else you would like to say about this experience?

Children's interviews

When asking young children questions it is important to have the question structure prepared in advance and to be friendly and attentive to their responses (Cameron Citation2005). This was the case for this study. A class reading activity and being asked questions about this activity is an established part of the children's typical classroom experience. This meant that being asked questions about the book activity was a familiar experience for them. One week after their last story session, individual children were asked a series of simple questions related to story comprehension, signing knowledge and enjoyment of the story. The questions were:

Story comprehension

Who buys a chicken?

What did Ron buy?

What does Ron do every day?

What happens at the end of the story?

How many chicken eggs did Ron buy?

What is the sign for chicken?

What is this? (pointing to Dad)?

What is the sign for egg?

What is he doing? (while pointing to ‘eat’)?

Story experience.

Are you happy when your teacher tells this story?

Does the teacher use a special/funny (story) voice?

Does the teacher use gestures when telling stories?

Is the teacher happy when telling stories?

Procedure

Five kindergarten teachers from different schools volunteered to take part in the project. Four teachers attended a half day training session about the use of Big Book stories and Signalong Indonesia. Subsequently, one teacher received a training session in using Big Book stories without the Signalong Indonesia information. Each teacher used the book in their class for five consecutive days as part of their classes’ typical morning activities. During this week each teacher was observed once to check the fidelity of their implementation of the approach. In the following week, each teacher was interviewed about their experience of using the sign-supported big book. Individual children in each class were asked a series of questions about the story. Five questions related to story comprehension, four questions asked about the signs for specific parts of the story (related to the terms: egg, father, chicken and eat) and other questions asked about their experience of the story and if the teacher made the story fun or used gestures.

Findings

Teacher interviews

An enjoyable experience for both teacher and children

Without exception teachers found using a Signalong Indonesia supported storybook a very positive experience. They found it easy to use, enjoyed using it and reported that children enjoyed it also.

In my experience as a teacher and school principal movements [in] Signalong Indonesia is simple so the children can catch easily what I have taught to them

pleased with the introduction of Signalong [Indonesia] at [my] school

A new experience for us and our children and very pleasant

Very interesting, because this is the first time I am familiar with this method

The teachers felt there were no difficulties implementing the approach.

It improves children's engagement

Teachers reported that the main effects of using SI in this way were that children became more interested in the story, and that their interest was maintained for longer.

The difference is that children become more enthusiastic and happier with the story because there is movement, cue the story [and it] becomes more interesting

..children become more interested and [it is] easier to understand the story

Children become more interested when we tell stories using the Signalong [Indonesia] method

It makes the story fun, active and improves learning

All the teachers felt that Signalong Indonesia made the story activity more fun.

For the book itself, it felt like dancing, as well as the pictures

yes with the gesture, learning more fun and children become more active in learning

Of course, with learning to use child body movements so it seems more active

For the kindergarten children I teach, they feel happier with the story

They also emphasised how the activity of SI made learning easier for children, through improved understanding.

yes it easier to understand the story, even if only to see the image, they can read maybe they know the meaning, but for children who cannot read and understand through motion pictures [the signs]

Yes, the presence of Signalong [Indonesia] will facilitate students’ understanding of the vocabulary received

There was a belief that this method helped the children to remember the story and new concepts.

Yes, children can [mimes clicking fingers] remember the story, such as it says “Chicken” then direct the child to remember how to cue “chicken”

It takes time but still makes it [remembering ] easy

Children can capture the contents of the story. Although only partial, they catch it well, [because] children are happy and very excited by the story.

Developing the approach

Teachers made several suggestions about how the approach could be improved and developed. These suggestions included creating additional and more varied stories, and a story vocabulary guidebook for teachers so they could create their own stories and enhance existing storybook activities. They were also keen that the approach was introduced to other classes and schools and the ‘wider community’.

Children's Data

The four Sign Supported book classes (SSBB) and also the book alone (BA) class group of children reported that their teacher used gestures and funny voices and appeared ‘happy’ [senang/gembira] when telling the story. This was taken as an indication that the Big Books training has been implemented by both groups of teachers, where each of these aspects had been focused upon. This supported the researchers’ observations of teachers using the books as intended.

In terms of the children's reported happiness, in four SSBB and the one BA classes the majority of children reported they felt happy in the story book activity (100%, 94%, 90%, 100% and 81% respectively). These small differences suggest that significantly more of the SSBB group were likely to report being happy in relation to the story (Chi Square, p = 0.32).

In terms of learning Signalong Indonesia signs, as expected, these were only learned by the SSBB group and were correctly demonstrated in responses to the four ‘sign questions’ [answers: Chicken, egg, eat and father] by 62%, 62%, 62% and 83% of the children respectively. In relation to the five comprehension questions, these were answered correctly in four SSBB schools by 82%, 92%,75%,77% and 79% of the children respectively. In the BA school, these questions were answered correctly by only 5% of children.

Discussion

The findings of this project support previous research which found that children enjoy using keyword signs (Bowles and Frizelle Citation2016) and that Big Books (without signs) are a successful way of engaging young children with stories (Jayendra, Nitiasih, and Mahayanti Citation2018). The study goes beyond this existing research to show that Sign Supported Big Books are highly valued and enjoyed by teachers. Teachers’ accounts indicated that the Sign Supported approach made the stories more enjoyable and fun, both for themselves and the children they taught. The enjoyment that teachers and children had with the approach was evident from the interviews and workshop. They expressed a belief that happiness and fun were important and valued the SSBB approach because it was fun. Previous research has identified the significance given to fun and happiness by Indonesian teachers as an intrinsic part of teaching and learning (Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017; Sheehy and Budiyanto Citation2015). In contrast, Western educators tend to position happiness as ‘a tool for facilitating effective education’ (Fox Eades, Proctor, & Ashley, Citation2013, p.1). Fun is not an intrinsic part of good pedagogy but is located at best alongside and separate to achieving educational outcomes (Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017), and ‘at worst’ it can be positioned as having a detrimental effect. For example, the Centre for Education Economics (CEE) is reported as stating ‘Making lessons fun does not help children to learn … The widely held belief that pupils must be happy in order to do well at school is nothing more than a myth’ (Turner Citation2018). This view is not universally supported by Western researchers and there is some evidence that “Learning which is enjoyable (fun)..” (Elton-Chalcraft and Mills Citation2015, 482) is effective. These differences are likely to reflect epistemological beliefs about learning, which vary between countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCED) Citation2013), cultures and areas of study (Sheehy Citation2017). In line with this diversity, the current study adds to evidence that Indonesian teachers may hold views of the relationship between fun, happiness and learning that are different in nature to that typically found Western classrooms. It complements research indicating that many Indonesian teachers see fun and happiness as an integral part of effective pedagogy both for themselves and their learners (Budiyanto, Sheehy, and Rofiah Citation2017; Sheehy et al. Citation2017).

Evaluation of keyword signing within kindergartens remains absent, and this study is a first step in exploring this issue. It offers evidence that an approach that increases children's fun and happiness can enhance children's learning, at least within the mainstream kindergarten context. The potential of manual signing to have benefits for those who have no additional needs has been acknowledged within popular ‘Baby Signing’ programmes. This approach teaches babies to communicate with keyword signing before they can talk. The benefits claimed for this include improved language and social development, although these claims have been contested (Seal and De Paolis Citation2014; Doherty-Sneddon Citation2008). There is some evidence from the children's data that the SSBB approach significantly enhanced their learning. However, future research designs should allow for stronger conclusions to be drawn. The kindergarten classes were matched for age, and teachers were trained and monitored to support implementation fidelity. However, the individual developmental and social profiles of the children were not matched or able to be reviewed. It could be that the BA children's relative (and surprising) lack of learning was influenced by confounding developmental, social or teacher variables, rather than the lack of Sign Support. Therefore, in developing and evaluating the approach further the project will seek to address this issue, for example through a counterbalanced design to control for any individual differences.

With this caveat acknowledged, the study remains significant. It is the first to create and implement Sign Supported Big Books in kindergartens in Indonesia. Teachers positive responses to, and appraisals of, the approach were supported in the children's data. Teachers were keen to take up this new approach and their suggestion of providing Signalong Indonesia materials to allow them to support storybooks of their own choice will be followed up. This request is important in the context of the project as this suggests that mainstream teachers see pedagogic value in using Signalong Indonesia within their ‘non-special’ mainstream classes. This confirms an assumption of the project was that teachers might welcome the project-created books as useful teaching resources, and this would be the means of getting an inclusive KWS approach into kindergartens. However, whilst teachers did welcome the books, their feedback foregrounded increased access to Signalong Indonesia vocabulary and training, so that they could use it to support their personal choice of books and stories. They saw Signalong Indonesia as a welcome way of enhancing books and stories as opposed being to a ‘special education technique’. This is an important finding given the widespread stigmatisation of children with learning disabilities and signing (Budiyanto, Kaye, and Rofiah Citation2020). It suggests that a SSBB approach in which teachers select KWS to enhance their own stories is worth pursuing further as a proactive strategy.

The study developed following discussion with teachers about how the Inclusive Indonesian Classrooms project might address three factors that contributed to the ‘Kindergarten Catch 22’. The findings offer some original and useful insights for future work in relation to these factors. The stigmatisation of children with special educational needs has led to the widespread stigmatisation of signing in Indonesia (Budiyanto, Kaye, and Rofiah Citation2020). The enthusiasm of these mainstream teachers (albeit in a very small sample) to use, and develop, Sign Supported Big Books was a very positive outcome in that it suggests that this way of introducing Signalong Indonesia into kindergartens might be welcomed. However, the current study is based on a small sample of volunteers and their attitudes may not be representative of the wider population. Therefore, a next step for the project will be to offer the approach to a much larger sample of schools and see if this welcome holds more widely. Our findings suggest that Sign Supported Big Books are a practical easily implemented teaching approach, and we found no evidence that this approach was detrimental for children who used it. A next step regarding this issue will be to evaluate the approach in classrooms that also include children with special educational needs and to design the evaluation in a way that more tightly controls for individual differences. This will allow us to assess the degree to which the approach might support all learners within diverse inclusive classes. Lastly, teachers enjoyed and valued using the approach with their mainstream kindergarten classes. The Inclusive Indonesian classrooms project will need to consider the extent to which this positive experience might influence the willingness of teachers to accept children with special educational needs into their classes.

The project was original in its intention. It attempted to evaluate an inclusive teaching approach as part of the everyday classroom practice and in classes without any children with special educational needs. This was proposed as a proactive way of beginning to address the Indonesian Kindergarten Catch 22 situation. The underpinning stance was that one doesn't need a disabled child in a class to justify using inclusive classroom practices. The findings of this study support this novel stance.

Conclusion

Sign Supported Big Books were evaluated in mainstream kindergarten classes as a possible way of enhancing the inclusive affordances of Indonesian kindergartens. This was the first time this approach had been used in Indonesian kindergartens. The findings suggested that teachers valued the approach and felt that, because it was fun, it enhanced children's learning. This study suggests that SSBB has the potential for getting around the stigmatisation of signing, offers research evidence about pedagogy where none currently exists and indicates that SSBB has merit as a new teaching resource for kindergartens. The project identifies the potential of creating teaching approaches and resources that are likely to work well for a diverse group of children as a proactive means of addressing the ‘Kindergarten Catch 22’ which currently exists in Indonesia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, Anne, and Anna Cox. 2008. “Questionnaires, in-Depth Interviews and Focus Groups Book Chapter and Focus Groups.” In Research Methods for Human Computer Interaction, edited by Paul Cairns and Anna Cox, 17–34. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

- Anggia, Dini, and Harun Harun. 2019. “Description of Implementation Inclusive Education for Children with Special Needs in Inclusive Kindergarten.” Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (Icsie 2018): 181–187. doi:10.2991/icsie-18.2019.34.

- Aprilia, Imas Diana. 2017. “Flexible Model on Special Education Services in Inclusive Setting Elementary School.” Journal of ICSAR 1 (1): 50–54. http://journal2.um.ac.id/index.php/icsar/article/view/369.

- Baines, Paul. 2011. “Assent for Children’s Participation in Research Is Incoherent and Wrong.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 96 (10): 960–962. doi:10.1136/adc.2011.211342.

- Bednarski, Mateusz. 2016. “The Exploring of Implementing Makaton in Multi – Sensory Storytelling for Children with Physical and Intellectual Disabilities Aged Between 5 and 10.” World Scientfica News 47 (1): 1–61. www.worldscientificnews.com.

- Bowles, Caoimhe, and Pauline Frizelle. 2016. “Investigating Peer Attitudes Towards the Use of Key Word Signing by Children with Down Syndrome in Mainstream Schools.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 1–8. doi:10.1111/bld.12162.

- Brady, L. M., and C. Shaw. 2012. “Involving Children and Young People in Research .” Social Care, Service … , no. November. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=I4_kNuKh0jUC&oi=fnd&pg=PA226&dq=involving+children+and+young+people+in+research+&ots=SwwWk0PcWk&sig=lszQeNnUl2fveeYz-rYvjGxD8_Q.

- Budiyanto, Kieron Sheehy, Helen Kaye, and Khofidotur Rofiah. 2020. “Indonesian Educators’ Knowledge and Beliefs About Teaching Children with Autism.” Athens Journal of Education 10: 1–23. 1-4.

- Budiyanto, K., H. Kaye Sheehy, and K. Rofiah. 2017. “Developing Signalong Indonesia: Issues of Happiness and Pedagogy, Training and Stigmatisation.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–17. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1390000.

- Cameron, Helen. 2005. “Asking the Tough Questions: A Guide to Ethical Practices in Interviewing Young Children.” Early Child Development and Care 175 (6): 597–610. doi:10.1080/03004430500131387.

- Colville-Hall, Susan, and Barbara O’Connor. 2006. “Using Big Books: A Standards-Based Instructional Approach for Foreign Language Teacher Candidates in a PreK-12 Program.” Foreign Language Annals 39 (3): 487–506. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2006.tb02901.x.

- Sunardi Diana, Gunarhadi, and Munawir Yusuf. 2020. “‘Preschool Teachers’ Attitude Toward Inclusive Education in Central Java, Indonesia.” Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 397 (Icliqe 2019): 1361–1368.

- Doherty-Sneddon, Gwyneth. 2008. “The Great Baby Signing Debate.” The Psychologist 21 (6): 300–304.

- Ediyanto, Ediyanto, Iva Nandya Atika, Norimune Kawai, and Edy Prabowo. 2017. “Inclusive Education in Indonesia from the Perspective of Widyaiswara in Centre for Development and Empowerment of Teachers and Education Personnel of Kindergartens and Special Education.” IJDS: Indonesian Journal of Disability Studies 4 (2): 04–116. doi:10.21776/ub.ijds.2017.004.02.3.

- Elton-Chalcraft, Sally, and Kären Mills. 2015. “Measuring Challenge, Fun and Sterility on a ‘Phunometre’ Scale: Evaluating Creative Teaching and Learning with Children and Their Student Teachers in the Primary School.” Education 3-13 43 (5): 482–497. doi:10.1080/03004279.2013.822904.

- Fereday, Jennifer, and Eimear Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (March): 80–92. doi:10.1063/1.2011295.

- Florian, Lani, and Kristine Black-Hawkins. 2011. “Exploring Inclusive Pedagogy.” British Educational Research Journal 37 (5): 813–828. doi:10.1080/01411926.2010.501096.

- Fox Eades, Jennifer, M. Carmel Proctor, and Martin Ashley. 2013. “Happiness in the Classroom.” In Oxford Handbook of Happiness, edited by Ilona Boniwell, Susan David, and Amanda Conley Ayres, 1–11 . Oxford: Oxford University Press,.

- Handoyo, R. T., A. Ali, K. Scior, and A. Hassiotis. 2018. “Attitudes of Key Professionals Towards People with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Inclusion in Society: A Qualitative Study in an Indonesian Context.” Transcultural Psychiatry 50 (3): 379–391. doi:10.1177/1363461520909601.

- Heller, Joseph. 1961. Catch-22. New York: Simon & Schuste.

- Jauhari, Muhammad Nurrohman. 2017. “Pengembangan Simbol Signalong Indoesia Sebagai Media (Developing Signalong Indonesia’s Communication Symbols).” In International Conference on Special Education in Southeast Asia Region, 411–16. Malang: ICSAR.

- Jayendra, I. M. S., P. K. Nitiasih, and N. W. S. Mahayanti. 2018. “The Effect of Big Books As Teaching Media on the Second Grade Students’ Reading Comprehension in South Bali.” International Journal of Language and Literature 2 (2): 82–89. doi:10.23887/ijll.v2i2.16097.

- Jenkins, Jade Marcus, Tyler W. Watts, Katherine Magnuson, Elizabeth T. Gershoff, Douglas H. Clements, Julie Sarama, and Greg J. Duncan. 2018. “Do High-Quality Kindergarten and First-Grade Classrooms Mitigate Preschool Fadeout?” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 11 (3): 339–374. doi:10.1080/19345747.2018.1441347.

- Kristiana, Ika Febrian, and Wiwin Hendriani. 2018. “Teaching Efficacy in Inclusive Education (IE) in Indonesia and Other Asia, Developing Countries: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn) 12 (2): 166. doi:10.11591/edulearn.v12i2.7150.

- Lever, Rosemary, and Monique Sénéchal. 2011. “Discussing Stories: On How a Dialogic Reading Intervention Improves Kindergartners’ Oral Narrative Construction.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 108 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2010.07.002.

- McGillicuddy, Sarah, and Grainne M. O’Donnell. 2014. “Teaching Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Post-Primary Schools in the Republic of Ireland.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (4): 323–344. doi:10.1080/13603116.2013.764934.

- Mistry, Malini, and Danielle Barnes. 2012. “The Use of Makaton for Supporting Talk, Through Play, for Pupils Who Have English as an Additional Language (EAL) in the Foundation Stage.” Education 3-13 41 (6): 603–616. doi:10.1080/03004279.2011.631560.

- Mitchell, David. 2020. What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education. Using evidence-based teaching strategies. 3rd. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCED). 2013. “Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2013 Conceptual Framework.” http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/talis-2013-results.htm.

- Poernomo, Baby. 2016. “The Implementation of Inclusive Education in Indonesia: Current Problems and Challenges.” American International Journal of Social Science 5 (3): 144–150.

- Raičević, Tina Dimić. 2020. Kindergarten Is Important for Every Child Regardless of Where They Grow Up. Montenegro: UNICEF.

- Ramos-Mattoussi, Flavia, and Jeffrey Ayala Milligan. 2013. Building Research and Teaching Capacity in Indonesia Through International Cooperation. New York: Institute of International Relations (IIE). www.iie.org/cip.

- Rix, Jonathan. 2015. Must Inclusion Be Special?: Rethinking Educational Support Within a Community of Provision. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Must_Inclusion_Be_Special.html?id=d92-oAEACAAJ&pgis=1.

- Rix, Jonathan, Kieron Sheehy, Felicity Fletcher-Campbell, Martin Crisp, and Amanda Harper. 2013. Continuum of Education Provision for Children with Special Educational Needs: Review of International Policies and Practices. Dublin: National Council for Special Education.

- Sabila, Hanifah, and Farida Kurniawati. 2019. “Parental Attitudes of Preschool Children Toward Students with Special Needs in Inclusive and Non-Inclusive Kindergartens: A Comparative Study.” Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 229 (Iciap 2018): 602–609. doi:10.2991/iciap-18.2019.51.

- Seal, Brenda C., and Rory A. De Paolis. 2014. “Manual Activity and Onset of First Words in Babies Exposed and Not Exposed to Baby Signing.” Sign Language Studies 14 (4): 444–465. doi:10.1353/sls.2014.0015.

- Sheehy, K. 2017. “Ethics, Epistemologies, and Inclusive Pedagogy.” International Perspectives on Inclusive Education 9. doi:10.1108/S1479-363620170000009003.

- Sheehy, K., and Budiyanto. 2014. “Teachers’ Attitudes to Signing for Children with Severe Learning Disabilities in Indonesia.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (11): 1143–1161. doi:10.1080/13603116.2013.879216.

- Sheehy, K., and Budiyanto. 2015. “The Pedagogic Beliefs of Indonesian Teachers in Inclusive Schools.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 62 (5): 469–485. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2015.1061109.

- Sheehy, K., Budiyanto, H. Kaye, and K. Rofiah. 2017. “Indonesian Teachers’ Epistemological Beliefs and Inclusive Education.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 174462951771761. doi:10.1177/1744629517717613.

- Sheehy, Kieron, Jonathan Rix, Janet Collins, Kathy Hall, Melanie Nind, and Janice Wearmouth. 2009. “A Systematic Review of Whole Class, Subject- Based Pedagogies with Reported Outcomes for the Academic and Social Inclusion of Pupils with Special Educational Needs.” Search. London. http://oro.open.ac.uk/10735/.

- Sunardi, Sunardi, Mucawir Yusuf, Gunarhadi Gunarhadi, Priyono Priyono, and John L. Yeager. 2011. “The Implementation of Inclusive Education for Students with Special Needs in Indonesia.” Excellence in Higher Education 2 (1): 1–10. doi:10.5195/ehe.2011.27.

- Suwaryani, N. 2008. “Policy Analysis of Education Provision for Disabled Children in Indonesia: A Case Study of Eight Primary Schools in Kecamatan Jatiwulung.” PQDT – UK & Ireland. http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.479388.

- Turner, Camilla. 2018. “Making Lessons Fun Does Not Help Children to Learn, New Report Finds.” The Daily Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/2018/11/14/making-lessons-fun-does-not-help-children-learn-new-report-finds/.

- Yaacob, Aizan, and Annamaria Pinter. 2008. “Exploring the Effectiveness of Using Big Books in Teaching Primary English in Malaysian Classrooms.” Malaysian Journal of Learning & Instruction 5: 1–20.