ABSTRACT

Playful learning has garnered supporters and research evidence, and also can be seen as nebulous and, therefore, reliant on practitioners’ intuitions in early education settings. In this paper, we offer an explicit theoretical account, grounded in developmental psychology of how play might support the acquisition of broad skills and dispositions for lifelong learning. We argue that play develops self-regulation and motivation, both of which support the child’s agency in their learning. We discuss a culturally inclusive view of agency that is distinct from autonomy, and which is visible in many existing early childhood pedagogies. We conclude by suggesting practical strategies that educators can adopt to enhance learning through play and children’s agency in their learning.

1. Introduction

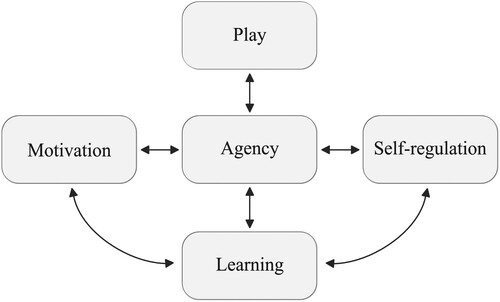

Playful approaches can be an effective way for educators to support young children’s learning and skill development (Sylva, Bruner, and Genova Citation1976; White and Carlson Citation2016). In the present theoretical review paper, we contend that playful learning works because it harnesses the way the brain learns naturally. We illustrate how playful learning makes space for children’s agency in their learning by giving children control and engaging them as willing participants. Developing agency in learning, in turn, exercises two psychological mechanisms that bestow positive, general skills and attitudes towards learning: self-regulation and motivation (McLelland and Cameron Citation2011; Benware and Deci Citation1984). This creates a positive feedback loop such that the more these mechanisms are strengthened, the more children can employ their agency for learning, as shown with the bidirectional arrows in . This reflects a multifactorial space rather than a simple linear causal chain.

Figure 1. Multifactorial space between play, agency and learning, via two psychological mechanisms: self-regulation and motivation.

The contribution of the present paper lies primarily in bringing together discussions from education and psychology to offer a theoretical account of how playful approaches can support children’s agency in learning and the developmental benefits that ensue. We identify the psychological mechanisms in the existing empirical literature which are associated with agency in learning, and then we identify educational practices used to support the development of these mechanisms. We adopt a culturally inclusive view of agency, which connects with learning approaches like guided play, where control is shared, and approaches that emphasise participation and willingness on the child’s part, regardless of control.

2. Learning, play and agency

2.1. Learning as an active process

Learning is most likely to occur when the participant is engaged in the process rather than through a passive ‘banking model’ (hooks Citation1994; Hassinger-Das, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff Citation2017). This active, willing involvement in learning, connecting cognition to action, and back again, helps children to build strategies to make the most of future learning opportunities (Bonawitz et al. Citation2011). At a cognitive level, even very young infants are endowed with a ‘preparedness to learn’ (Pauen and Hoehl, Citation2015). This active stance towards learning stems from regularities that infants glean and the expectations they generate about the world around them. Experimental psychology studies show that surprise generates arousal (Brod, Haselhorn, and Bunge Citation2018), meaning when something unexpected happens, attention is heightened. The arousal is specific to the learning target rather than just general arousal across the board. In other words, learning begins already with the generation of the expectations themselves, setting the stage for what comes next and building a reinforcing loop. The internal world of the young learner, including these expectations, is a driving force in future actions. These expectations allow learners, even in the first year of life, to selectively act and to explore strategically rather than take stabs in the dark (Stahl and Feigenson Citation2015; Brod, Hasselhorn, and Bunge Citation2018). Critically, then, learning depends on the child’s engagement in planning their own course of action, based on their understanding, and being able to follow through and make comparisons between their expectations and their observations of real-world manifestations thereof. Developmental psychology describes learning as an active process. In what ways can play support learning?

2.2. Playful learning

Play has seen a recent resurgence of interest with developmental psychology publications demonstrating its potential effectiveness for learning [e.g. as opposed to other ways that play can support child development, like play for well-being, civic action, etc. (Adair et al. Citation2017)]. Various terms are used to describe learning that has a playful element: self-directed, child-centred, child-led, guided play, discovery learning (Alfieri et al. Citation2011 ; Weisberg et al. Citation2015; Zosh et al. Citation2018; Honomichl and Chen Citation2012). Like spokes on a wheel, these approaches are distinct, yet related to the core concept of playful learning insofar as they share an emphasis on the child’s experience as active, willing, pleasurable, flexible and meaningful. Several studies demonstrate that playful learning can lead to effective learning of specific conceptual content (e.g. Fisher et al. Citation2013; Ferrara et al. Citation2011; Eason and Ramani Citation2020). Some argue the link between play and learning may not be causal (Lillard et al. Citation2013). There are also some studies showing more directive, teacher-led approaches lead to better learning than playful, learner-led approaches [e.g. of reasoning strategies (Klahr and Nigam Citation2004)]. Nevertheless, the nuanced and documented association between play and learning is convincing enough to merit further theoretical examination. Why, from a developmental psychology perspective, might play be associated with learning?

The active nature of play is a key reason why such approaches can exercise psychological mechanisms that support learning. For example, playful learning makes space for children to engage with their learning through question-asking, exploration, curiosity, persistence, engagement in discussion and sharing interests between the classroom and the real world (e.g. Dunlop et al. Citation2015; LoBue et al. Citation2013; Neitzel, Alexander, and Johnson Citation2008 though there is some cultural variation in these effects, see Areepattamannil Citation2012). We say that playful learning ‘makes space’ because it is not the provision of the activity itself that exercises the psychological mechanisms for learning. Rather, it is the way the child engages with their learning that matters. For example, teachers can approach learning playfully through sustained shared thinking with the children in their class (Sylva et al Citation2004), and planning in the moment (Ephgrave Citation2018), to support children to persevere with a math problem when things become difficult. Teachers might encourage children to find a different set of manipulatives to test things out with or ask groups of children to use their own bodies to add and subtract, helping children notice new angles or practice using new materials. In all of these situations, the teachers ‘make space’ for the child to continue making meaning through their learning, but this only happens if the child itself actively pursues the activity. The child is, in this sense, in the driving seat. In the next section, we elaborate on the inner experiences that playful learning may foster.

2.3. Agency through playful learning

In the present paper, we focus on agency as a causal force originating in the learner that supports emancipation from automatic thoughts and actions and from externally imposed constraints (Leslie Citation1994; Adai Citation2014; Rainio and Hilppo Citation2017). Playful learning allows children to experience agency in their learning because it gives children choice and control (Perry, Citation2013); it situates children as active participants in their learning (Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff, Citation2011); and it relies on their willingness and endorsement of the activity at hand. These three elements, control, participation and willingness, represent a constellation of features of agency in playful learning, which may be more or less present depending on the context.

Agency can occur in many contexts, not just in play. Conversely, it is hard to imagine genuine play without agency. Whereas we see play as an approach or a way of learning, we see agency as the child’s inner experience. As such, play is one type of context in which children may experience agency in their learning. Play provides a context for the child to experience agency in its learning, insofar as the child is an actor, and has a choice, commitment, and interest in what it is doing. In play, children can flexibly adapt the course of learning to allow for exploration and they can experience joy connected with effort. We argue that, beyond helping children learn specific conceptual content like geometric shapes and new words (Fisher et al. Citation2013; Ferrara et al. Citation2011; Eason and Ramani Citation2020), playful approaches can build agency which, in turn, supports positive attitudes and skills for lifelong learning.

Agency makes it possible for the child to own and guide their own train of thought – for example by imagining a plot twist to a familiar pretend play scenario. In this example, the agency is entirely internal to the child’s own thoughts and desires. In addition to this internal form of agency, the child can guide their own actions via an external form of agency by putting on a doctor’s coat and joining in with someone else’s pretend play. Whether solo or in collaboration with others, the internal and external forms of agency share the elements of being freely chosen, active and potentially bearing a causal force on subsequent events. Hence, some degree of open-endedness, characteristic of playful learning, allows these potent opportunities for young children.

While open-endedness makes space for the child to enter and steer the learning activity, structure is also seen as an important complement to agency (Jang, Reeve, and Deci Citation2010). Structure can provide organising principles, and orient a child’s attention to a meaningful choice for them to deliberate; structure can provide specific ‘in-roads’ for the child to be active in their learning; and structure can make the scope of the activity or playworld clear so that willing commitment from the child is an informed action. Too much structure can disrupt the natural pace of learning and lead to anxiety (Assor et al. Citation2005). Yet just enough structure can exist in a way that is sensitive to children’s need for agency and may even be actively endorsed by the child (Barker and Munakata Citation2015; Guay, Roy, and Valois Citation2017; Skinner and Belmont Citation1993; Perry and Winne Citation2012; Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2012).

2.4. Contextual variation in agency

As with so many notions in developmental psychology, there is a universal essence of agency expressed through contextual variation. In the same way that playful learning is not a formula but rather a result from ‘mise en place’ (Weisberg et al. Citation2014); agency is an internal experience, not merely a consequence of a set of external circumstances. The same action or question from an adult can be received differently by different children. In building a tower, for example, a young child in one family may expect guidance and support from their parent, while in another family, the same outward form of guidance and support could be experienced as infringing on the child’s own plans (Lee, Baker, and Whitebread Citation2018; Holochwost et al. Citation2016).

From a culturally inclusive perspective, agency is not merely autonomy or doing something for and by oneself, which implies independence and self-sufficiency (Iyengar and Lepper Citation1999; Rothbaum and Trommsdorff Citation2007). While agency does entail self-reflection in thought and self-determination in action, the scope of these can extend to a wider community and is, therefore, consistent with collectivist values. For example, agency can come from willingly joining a group endeavour (e.g. valuing harmony and duty) without emphasising autonomy or independence (Hofmann and Rainio Citation2007). Indeed, in some cultural contexts, children are more willing to do a task when it is chosen by a trusted figure than when they chose it themselves (agency with less emphasis on control, more emphasis on willing participation; Iyengar and Lepper Citation1999; see also Areepattamannil Citation2012). In broader terms of playful learning, children can experience agency in a joint project that is somewhat open-ended because, even if they are not personally entirely in control, their ideas and actions have the potential to shape the outcome of a shared pursuit. Agency is an internal experience and a result of social and cultural factors surrounding the child, with varying degrees of active participation and willing endorsement. In this respect, agency is contextual.

Thinking about agency with a broad cultural lens, in turn, helps us broaden our conception of playful learning. The research on guided play for learning (Zosh et al. Citation2018) stems from work in North America. Guided play as a conceptual frame centres on who is choosing, steering, or in control (an adult or a child). This notion of control – how much or how little the child has – is distinct from the other dimensions of agency we have outlined (active participation and willingness). Indeed, agency in playful learning does not have to be through guided play (Yu et al. Citation2018). Playful learning could be done alone or with a peer who is not a guide or could be completely initiated by the child (like when young children point to ask during playful interactions (Begus, Gliga, and Southgate Citation2014)). Thus, in a culturally inclusive view of agency, there are a variety of playful approaches that can support agency in learning, including approaches that focus on the child’s active participation and willingness, even when control is shared. In this sense, agency is relational.

We argue that, despite the variation, playful approaches to learning can exercise forms of child agency that engage general psychological mechanisms propitious for learning: specifically, self-regulation and motivation. In the next section, we explore why this could be the case.

3. Agency supports broad attitudes towards and skills for learning

In this section, we elaborate on the mechanistic connection between play, agency and learning. Agentic learning is like a car on the road: it needs an engine to get going, and it needs to steer correctly to its destination. The impetus stems from motivation and the navigation stems from self-regulation. In what follows, we illustrate how agency through playful learning can support the development of positive approaches to lifelong learning that are mutually reinforcing ().

3.1. Agency in playful learning supports self-regulation

Self-regulation is the ability to guide thoughts, emotions, behaviour and attention deliberately and it can be used to adapt behaviour to different contexts (McLelland and Cameron Citation2011). Rather than acting automatically or according to habit, self-regulation makes it possible to adjust thoughts and actions volitionally in the moment and to plan and choose courses of action for the future (Blair and Diamond 2008). Self-regulation cuts across multiple domains of daily life, including social interactions, scientific reasoning and goal-directed activities such as building towers or drawing a picture, and, therefore, has broad implications for multiple aspects of child development. In particular, children, who have more effective self-regulation skills and strategies, tend to do better in school (e.g. Duckworth and Seligman Citation2005; McClelland et al. 2007). Therefore, when self-regulation is developed, learning is supported (Blair and Diamond 2008).

Conceptually, there is a clear connection between young children’s agency in learning and their self-regulation (Perry et al. Citation2002; Robson Citation2010). Agency comes with responsibility on the part of the learner because stake in the future course of action is shared by the child when they have agency. This puts the onus on the child’s self-regulation to orient and select thoughts and behaviours that are desirable for themselves and being adaptive to their context. When children have agency in playful learning, they can explore and consolidate their experiences and the consequences of these (Perry et al. Citation2002). They practice recognising when they should adopt a different approach, connecting inner impetus with action. In our view, the possibility of being a causal force, with an intention or willingness originating internally, and being brought to fruition, is both agentic and enabling for learning. In what follows, we outline some of how agency through playful learning relates to the development of self-regulation.

When learning is agentic, children have an opportunity to develop new ways of doing things. When they face a challenge, they have to shift from doing one thing to another, rather than persevering with an approach that is not working. This requires self-regulation insofar as challenge elicits self-evaluation, taking stock and planning next steps (Robson Citation2010). This is more likely to happen when the task is somewhat open-ended and all of the steps have not been pre-ordained [like on a worksheet or following a scripted regime to solve problems (Perry Citation2013)]. For example, when children are given the opportunity to practise making decisions about which workstation to join during freeflow time, they use self-regulatory strategies based on knowledge of themselves, past successes and challenges, and current information about their environment (e.g. how much space there is at a station) to select an activity appropriate for themselves, when to start, and when to stop. They can experience pride in sharing this with classmates who are also working on their respective areas of focus (similar to the self-regulation experience in Perry et al.’s (Citation2002) shared story reading example). In these examples of challenge and problem-solving, there is agency because the child’s inner observations have the potential to causally impact future courses of action. Modifying their decisions and actions as a function of the context, they find themselves in building self-regulation. It is worth noting that, as reflected in the bidirectional arrows in our model, agency can build self-regulation, and self-regulation can support agency (). In other words, children, who struggle with self-regulation, may find it more difficult to make the most of agentic learning when more of the onus is on the child (e.g. Perry et al. Citation2002). These children may need an additional structure from the teacher or their environment.

To further illustrate the connection between agency, self-regulation and learning through play, consider a non-agentic situation where the learner’s thoughts and actions have no causal bearing on what happens next, e.g. practising writing letters without any context or wider objective than forming the letters themselves. In these non-agentic, non-playful learning situations, the child does not need to engage their own expectations and anticipate future events nor to turn over various possibilities and combinations in their mind to select the best next steps. In the absence of agency, the chain between intention and action is severed. We argue that this misses out on the opportunity to build effective self-regulation skills for a broader impact on learning and life.

In this section, we discussed just a few ways in which agency in playful learning can connect to children’s developing self-regulation. Next, we review another mechanism that can support learning through agency and play: motivation.

3.2. Agency in playful learning supports motivation

Motivation is broadly defined as being moved to act (Ryan and Deci Citation2000) and as an ‘internal process that energises, directs, and sustains behaviour’ (Reeve Citation2016, 31; Harter Citation1975). Motivation in learning can be driven by the inner desire or external pressure (e.g. Guthrie et al. Citation2006; Ryan and Deci Citation2000; Senko et al. Citation2011; Wigfield and Eccles Citation2000). The link between inner motivation and learning is well supported by studies with school-aged children (e.g. Benware and Deci Citation1984; Ryan, Connell, and Plant Citation1990; Grolnick and Ryan Citation1987; Hidi and Renninger Citation2006). In particular, interest and curiosity are inner motivators that are related to improved learning (Anmarkrud and Braten Citation2009; O’Keefe and Linnenbrink Garcia Citation2014; Arnone, Grabowski, and Rynd Citation1994; Schiefele and Krapp Citation1996). Learning is then not something that is ‘experienced as alienating’ (Ryan and Lynch Citation2003, 261), but something individuals are engaging in out of their own volition. By contrast, motivation that comes from external pressures tends to be related to poorer learning outcomes (e.g. Benware and Deci Citation1984; Becker et al. Citation2010). Although a focus on grades can be beneficial to performance on tests (e.g. Elliot and Church Citation1997; Harackiewicz et al. Citation1997), improved test scores do not always equate with better learning (Benware and Deci Citation1984). Agency and playful learning are at the heart of inner motivation by harnessing the internal drive to learn and do (as opposed to external pressures like sticker rewards). Here we describe the theorised connection between agency and inner motivation for learning in the context of playful learning.

When agency is present, in particular, through the absence of coercive constraints and through active engagement of children’s faculties, it engages the feelings of internal control and volition that mean inner motivation is supported (Reeve and Jang Citation2006; Reeve et al. Citation2004; Ryan and Deci Citation2000). As indicated in , we argue this connection is bidirectional: internally motivating activities will also foster agency in return (see also Lee and Reeve 2013). If willingness is an essential element of agency, then it is children’s inner motivation that will give them the impetus to act on opportunities to be agentic (Rowe, and Neitzel Citation2010). Playful learning, therefore, supports agency by providing learning opportunities that are pleasurable and interesting, and thus motivating, and space for children to follow through on these interests and on their internal drive to learn.

Conversely, when the capacity to act is curtailed motivation for engaging in a learning activity will be challenged. For example, not feeling competent (e.g. due to the lack of knowledge) leads to feelings of powerlessness and reduces motivation and agency (Boggiano and Katz Citation1988; Tulis and Fulmer Citation2013; Wigfield and Eccles Citation2000). Thus, in a playful learning environment, children need a structure to build knowledge and confidence that work alongside agency and feed into motivation for learning (Jang, Reeve, and Deci Citation2010; Hospel and Galand Citation2016). Contextual factors can influence children’s agency in playful learning even in the presence of motivation. For example, gender stereotypes can constrain children’s participation in certain kinds of play, despite an obvious desire on the child’s part to be included in the play (Rainio and Hilppo Citation2017; Wood Citation2014).

Finally, when playful learning involves group activities and joint projects, and where cultures of learning foster care and respect, children may still feel internally motivated and agentic in their learning despite little individual decision-making because the project space is open and children’s ideas are valued (Hofmann and Rainio Citation2007). Open-endedness invites active, willing contributions, which can influence the direction of the work (Hofmann and Rainio Citation2007). Shared goals are endorsed and internalised by the child, while the feeling of belonging and the experience of being heard and valued supports children’s motivation and feeling of agency even when decisions are made communally.

4. Implications and conclusion

Our theoretical review suggests playful learning works because it supports children’s agency in their learning by using, and by extending, their natural abilities to learn, predict, adapt to and engage with their environment. Specifically, agency supports children’s self-regulation and motivation to learn. Thinking broadly about the role of agency in playful learning expands our conception of playful learning, including control , active participation and willing endorsement.

reflects the bidirectional nature of these relations, such that playful learning can provide opportunities to develop agency, and agency supports children’s ability to engage in playful learning. In addition to considering how agency is embodied in different cultural contexts and age groups, differently abled learners may engage in various ways with playful approaches to learning. For example, a child’s capacity for self-regulation may be an important factor in how well they engage with playful learning opportunities. This bidirectional flow between outward opportunities and the child’s inner characteristics is a common feature in early childhood across many areas of development.

Due to the prevalence and acceptability of learning through playful approaches in early childhood education, young children may experience agency in learning regularly. Based on the present theoretical review of the underlying psychological mechanisms - self-regulation and motivation – some quality practices that are commonly used to support agency in learning are to

Create a learning environment with structured organisers that are meaningful and age-appropriate

Stimulate interest and curiosity, and take turns following and leading

Scaffold children’s learning, self-regulation and motivation with predictable routines and in-depth conversations to extend their thinking

Observe children with agency in mind, reflect on experiences of agency in one’s own teaching practice.

These practices are not new. We highlight these practices here to distil the practical implications of the present theoretical review and emphasise their connection with supporting agency through playful learning. These can be integrated into teaching practice to varying degrees and will give rise to various challenges and benefits depending on the linked practices they connect with (Perry Citation2013).

Our theoretical review, drawing together developmental psychology and educational practice, shows that making space for children’s agency through playful learning can support serious skills like self-regulation and inner motivation, which are, in turn, associated with positive learning outcomes. The notion of agency through playful learning can be used by educators to tailor workplace-based learning opportunities and to defend these forms of pedagogy for all learners.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tim Taylor, Barbara Isaacs, Marianne Valentine, Dee Rutgers, Audrey Kittredge, Natalie Day, Hayley Gains, Allison Haack, the 2020 summer reading group on agency and Al Mistrano for many inspiring discussions feeding into this work. They are also indebted to the teachers who worked with them as co-researchers in their Stepping Stones and TRAIL projects over several years.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adair, J. K. 2014. “Agency and Expanding Capabilities in Early Grade Classrooms: What It Could Mean For Young Children.” Harvard Educational Review 84 (2): 217–241. doi:10.17763/haer.84.2.y46vh546h41l2144

- Adair, J. K., L. Phillips, J. Ritchie, and S. Sachdeva. 2017. “Civic Action and Play: Examples from Maori, Aboriginal Australian and Latino Communities.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (5–6): 798–811. doi:10.1080/03004430.2016.1237049

- Alfieri, Louis, Patricia J. Brooks, Naomi J. Aldrich, and Harriet R. Tenenbaum. 2011. “Does Discovery-Based Instruction Enhance Learning?” Journal of Educational Psychology 103 (1): 1. doi:10.1037/a0021017

- Anmarkrud, Øistein, and Ivar Bråten. 2009. “Motivation For Reading Comprehension.” Learning and Individual Differences 19 (2): 252–256. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.09.002

- Areepattamannil, Shaljan. 2012. “Effects of Inquiry-Based Science Instruction on Science Achievement and Interest in Science: Evidence from Qatar.” The Journal of Educational Research 105 (2): 134–146. doi:10.1080/00220671.2010.533717

- Arnone, Marilyn P., Barbara L. Grabowski, and Christopher P. Rynd. 1994. “Curiosity as a Personality Variable Influencing Learning in a Learner Controlled Lesson With and Without Advisement.” Educational Technology Research and Development 42 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1007/BF02298167

- Assor, Avi, Haya Kaplan, Yaniv Kanat-Maymon, and Guy Roth. 2005. “Directly Controlling Teacher Behaviors as Predictors of Poor Motivation and Engagement in Girls and Boys: The Role of Anger and Anxiety.” Learning and Instruction 15 (5): 397–413. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.008

- Barker, Jane E., and Yuko Munakata. 2015. “Developing Self-Directed Executive Functioning: Recent Findings and Future Directions.” Mind, Brain, and Education 9 (2): 92–99. doi:10.1111/mbe.12071

- Becker, Michael, Nele McElvany, and Marthe Kortenbruck. 2010. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Reading Motivation as Predictors of Reading Literacy: A Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (4): 773–785. doi:10.1037/a0020084

- Begus, Katarina, Teodora Gliga, and Victoria Southgate. 2014. “Infants Learn What They Want to Learn: Responding to Infant Pointing Leads to Superior Learning.” PloS one 9 (10): e108817. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108817

- Benware, Carl A., and Edward L. Deci. 1984. “Quality of Learning With an Active Versus Passive Motivational Set.” American Educational Research Journal 21 (4): 755–765. doi:10.3102/00028312021004755

- Boggiano, Ann K., Deborah S. Main, and Phyllis A. Katz. 1988. “Children's Preference for Challenge: The Role of Perceived Competence And Control.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (1): 134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.134

- Bonawitz, Elizabeth, Patrick Shafto, Hyowon Gweon, Noah D. Goodman, Elizabeth Spelke, and Laura Schulz. 2011. “The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction Limits Spontaneous Exploration and Discovery.” Cognition 120 (3): 322–330. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.10.001

- Brod, Garvin, Marcus Hasselhorn, and Silvia A. Bunge. 2018. “When Generating a Prediction Boosts Learning: The Element of Surprise.” Learning and Instruction 55: 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.01.013

- Duckworth, Angela L., and Martin EP Seligman. 2005. “Self-Discipline Outdoes IQ in Predicting Academic Performance of Adolescents.” Psychological Science 16 (12): 939–944. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x.

- Dunlop, Lynda, Kirsty Compton, Linda Clarke, and Valerie McKelvey-Martin. 2015. “Child-Led Enquiry in Primary Science.” Education 3-13 43 (5): 462–481. doi:10.1080/03004279.2013.822013

- Eason, Sarah H., and Geetha B. Ramani. 2020. “Parent-Child Math Talk About Fractions During Formal Learning and Guided Play Activities.” Child Development 91 (2): 546–562. doi:10.1111/cdev.13199

- Elliot, Andrew J., and Marcy A. Church. 1997. “A Hierarchical Model of Approach and Avoidance Achievement Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (1): 218. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.218

- Ephgrave, Anna. 2018. Planning in the Moment with Young Children: A Practical Guide for Early Years Practitioners and Parents. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Ferrara, Katrina, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Nora S. Newcombe, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, and Wendy Shallcross Lam. 2011. “Block Talk: Spatial Language During Block Play.” Mind, Brain, and Education 5 (3): 143–151. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2011.01122.x

- Fisher, Kelly R., Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Nora Newcombe, and Roberta M. Golinkoff. 2013. “Taking Shape: Supporting Preschoolers’ Acquisition of Geometric Knowledge Through Guided Play.” Child Development 84 (6): 1872–1878. doi:10.1111/cdev.12091

- Grolnick, Wendy S., and Richard M. Ryan. 1987. “Autonomy in Children's Learning: An Experimental and Individual Difference Investigation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52 (5): 890–898. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.5.890

- Guay, Frédéric, Amélie Roy, and Pierre Valois. 2017. “Teacher Structure as a Predictor of Students’ Perceived Competence and Autonomous Motivation: The Moderating Role of Differentiated Instruction.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 87 (2): 224–240. doi:10.1111/bjep.12146

- Guthrie, John T., Allan Wigfield, Nicole M. Humenick, Kathleen C. Perencevich, Ana Taboada, and Pedro Barbosa. 2006. “Influences of Stimulating Tasks on Reading Motivation and Comprehension.” The Journal of Educational Research 99 (4): 232–246. doi:10.3200/JOER.99.4.232-246

- Harackiewicz, Judith M., Kenneth E. Barron, Suzanne M. Carter, Alan T. Lehto, and Andrew J. Elliot. 1997. “Predictors and Consequences of Achievement Goals in the College Classroom: Maintaining Interest and Making the Grade.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73 (6): 1284–1295. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1284

- Harter, Susan. 1975. “Developmental Differences in the Manifestation of Mastery Motivation on Problem-Solving Tasks.” Child Development 46 (2): 370–378. doi: 10.2307/1128130

- Hassinger-Das, Brenna, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff. 2017. “The C ase of Brain Science and Guided Play.” YC Young Children 72 (2): 45–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90004121

- Hidi, Suzanne, and K. Ann Renninger. 2006. “The Four-Phase Model of Interest Development.” Educational Psychologist 41 (2): 111–127. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

- Hirsh-Pasek, Kathy, and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff. 2011. “The Great Balancing Act: Optimizing Core Curricula Through Playful Pedagogy.” In The Pre-K Debates: Current Controversies & Issues, edited by Edward Zigler, Walter S. Gilliam, and W. Steven Barnett, 110–116. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co.

- Hofmann, Riikka, and Anna Pauliina Rainio. 2007. “It Doesn't Matter What Part You Play, it Just Matters That You're There: Towards Shared Agency in Narrative Play Activity in School.” In Language in Action: Vygotsky and Leontievian Legacy Today, edited by Riikka Alanen and Sari Pöyhönen, 308–328. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Holochwost, Steven J., Jean-Louis Gariépy, Cathi B. Propper, Nicole Gardner-Neblett, Vanessa Volpe, Enrique Neblett, and W. Roger Mills-Koonce. 2016. “Sociodemographic Risk, Parenting, and Executive Functions in Early Childhood: The Role of Ethnicity.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 36: 537–549. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.02.001

- Honomichl, Ryan D., and Zhe Chen. 2012. “The Role of Guidance in Children's Discovery Learning.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 3 (6): 615–622. doi:10.1002/wcs.1199.

- Hooks, Bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Freedom of Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Hospel, Virginie, and Benoît Galand. 2016. “Are Both Classroom Autonomy Support and Structure Equally Important for Students’ Engagement? A Multilevel Analysis.” Learning and Instruction 41: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.09.001

- Iyengar, Sheena S., and Mark R. Lepper. 1999. “Rethinking the Value of Choice: A Cultural Perspective on Intrinsic Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (3): 349. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.349

- Jang, Hyungshim, Johnmarshall Reeve, and Edward L. Deci. 2010. “Engaging Students in Learning Activities: It Is Not Autonomy Support or Structure But Autonomy Support and Structure.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (3): 588. doi:10.1037/a0019682

- Klahr, David, and Milena Nigam. 2004. “The Equivalence of Learning Paths in Early Science Instruction: Effects of Direct Instruction and Discovery Learning.” Psychological Science 15 (10): 661–667. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00737.x

- Lee, Min Kyung, Sara Baker, and David Whitebread. 2018. “Culture-Specific Links Between Maternal Executive Function, Parenting, and Preschool Children's Executive Function in South Korea.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 88 (2): 216–235. doi:10.1111/bjep.12221

- Leslie, Alan M. 1994. “ToMM, ToBy, and Agency: Core Architecture and Domain Specificity.” In Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture, edited by Lawrence A. Hirschfeld and Susan A. Gelman, 119–148. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lillard, Angeline S., Matthew D. Lerner, Emily J. Hopkins, Rebecca A. Dore, Eric D. Smith, and Carolyn M. Palmquist. 2013. “The Impact of Pretend Play on Children's Development: A Review of the Evidence.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (1): 1. doi:10.1037/a0029321

- LoBue, Vanessa, Megan Bloom Pickard, Kathleen Sherman, Chrystal Axford, and Judy S. DeLoache. 2013. “Young Children's Interest in Live Animals.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 31 (1): 57–69. doi:10.1111/j.2044-835X.2012.02078.x

- McClelland, Megan M., and Claire E. Cameron. 2011. “Self-Regulation and Academic Achievement in Elementary School Children.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2011 (133): 29–44. doi:10.1002/cd.302

- Neitzel, Carin, Joyce M. Alexander, and Kathy E. Johnson. 2008. “Children's Early Interest-Based Activities in the Home and Subsequent Information Contributions and Pursuits in Kindergarten.” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (4): 782. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.4.782

- O'Keefe, Paul A., and Lisa Linnenbrink-Garcia. 2014. “The Role of Interest in Optimizing Performance and Self-Regulation.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 53: 70–78. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2014.02.004

- Pauen, Sabina, and Stefanie Hoehl. 2015. “Preparedness to Learn About the World: Evidence from Infant Research.” In Epistemological Dimensions of Evolutionary Psychology, edited by Thiemo Breyer, 159–173. New York, NY: Springer.

- Perry, Nancy E. 2013. “Understanding Classroom Processes That Support Children's Self-Regulation of Learning.” In BJEP Monograph Series II: Part 10 Self-Regulation and Dialogue in Primary Classrooms, edited by David Whitebread, Neil Mercer, Christine Howe, and Andrew Tolmie, 45–67. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

- Perry, Nancy E., Karen O. VandeKamp, Louise K. Mercer, and Carla J. Nordby. 2002. “Investigating Teacher-Student Interactions That Foster Self-Regulated Learning.” Educational Psychologist 37 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3701_2

- Perry, Nancy E., and Philip H. Winne. 2012. “Tracing Students’ Regulation of Learning in Complex Collaborative Tasks.” In Interpersonal Regulation of Learning and Motivation, edited by Simone Volet and Marja Vauras, 59–80. London: Routledge.

- Rainio, Anna Pauliina, and Jaakko Hilppö. 2017. “The Dialectics of Agency in Educational Ethnography.” Ethnography and Education 12 (1): 78–94. doi:10.1080/17457823.2016.1159971

- Reeve, Johnmarshall. 2016. “A Grand Theory of Motivation: Why Not?” Motivation and Emotion 40: 31–35. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9538-2

- Reeve, Johnmarshall, and Hyungshim Jang. 2006. “What Teachers Say and Do to Support Students’ Autonomy During a Learning Activity.” Journal of Educational Psychology 98 (1): 209–218. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.209

- Reeve, Johnmarshall, Hyungshim Jang, Dan Carrell, Soohyun Jeon, and Jon Barch. 2004. “Enhancing Students’ Engagement by Increasing Teachers’ Autonomy Support.” Motivation and Emotion 28: 147–169. doi:10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

- Robson, Sue. 2010. “Self-regulation and Metacognition in Young Children's Self-Initiated Play and Reflective Dialogue.” International Journal of Early Years Education 18 (3): 227–241. doi:10.1080/09669760.2010.521298

- Rothbaum, Fred, and Gisela Trommsdorff. 2007. Do Roots and Wings Complement or Oppose One Another?: The Socialization of Relatedness and Autonomy in Cultural Context. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Rowe, Deborah Wells, and Carin Neitzel. 2010. “Interest and Agency in 2- and 3-Year-Olds’ Participation in Emergent Writing.” Reading Research Quarterly 45 (2): 169–195. doi:10.1598/RRQ.45.2.2

- Ryan, Richard M., James P. Connell, and Robert W. Plant. 1990. “Emotions in Nondirected Text Learning.” Learning and Individual Differences 2 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/1041-6080(90)90014-8

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Ryan, Richard, and Martin Lynch. 2003. “Motivation and Classroom Management.” In A Companion to the Philosophy of Education, edited by Randall Curren, 260–271. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470996454.ch19

- Schiefele, Ulrich, and Andreas Krapp. 1996. “Topic Interest and Free Recall of Expository Text.” Learning and Individual Differences 8 (2): 141–160. doi:10.1016/S1041-6080(96)90030-8

- Senko, Corwin, Chris S. Hulleman, and Judith M. Harackiewicz. 2011. “Achievement Goal Theory at the Crossroads: Old Controversies, Current Challenges, and New Directions.” Educational Psychologist 46 (1): 26–47. doi:10.1080/00461520.2011.538646

- Skinner, Ellen A., and Michael J. Belmont. 1993. “Motivation in the Classroom: Reciprocal Effects of Teacher Behavior and Student Engagement Across the School Year.” Journal of Educational Psychology 85 (4): 571. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

- Stahl, Aimee E., and Lisa Feigenson. 2015. “Observing the Unexpected Enhances Infants’ Learning and Exploration.” Science 348 (6230): 91–94. doi:10.1126/science.aaa3799

- Sylva, Kathy, Jerome S. Bruner, and Paul Genova. 1976. “The Role of Play in the Problem-Solving of Children 3-5 Years old.” In Play: Its Role in Development and Evolution, edited by J. S. Bruner, A. Jolly, and K. Sylva, 244–257. London: Penguin.

- Sylva, Kathy, Edward Melhuish, Pam Sammons, Iram Siraj-Blatchford, and Brenda Taggart. 2004. “The Effective Provision of Pre-school Education (EPPE) Project Technical Paper 12: The Final Report-Effective Pre-school Education.”

- Tulis, Maria, and Sara M. Fulmer. 2013. “Students’ Motivational and Emotional Experiences and Their Relationship to Persistence During Academic Challenge in Mathematics and Reading.” Learning and Individual Differences 27: 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2013.06.003

- Vansteenkiste, Maarten, Eline Sierens, Luc Goossens, Bart Soenens, Filip Dochy, Athanasios Mouratidis, Nathalie Aelterman, Leen Haerens, and Wim Beyers. 2012. “Identifying Configurations of Perceived Teacher Autonomy Support and Structure: Associations With Self-Regulated Learning, Motivation and Problem Behavior.” Learning and Instruction 22 (6): 431–439. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04.002

- Weisberg, Deena Skolnick, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, and Bruce D. McCandliss. 2014. “Mise en Place: Setting the Stage for Thought and Action.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 18 (6): 276–278. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.012

- Weisberg, Deena Skolnick, Audrey K. Kittredge, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, and David Klahr. 2015. “Making Play Work for Education.” Phi Delta Kappan 96 (8): 8–13. doi:10.1177/0031721715583955

- White, Rachel E., and Stephanie M. Carlson. 2016. “What Would Batman Do? Self-Distancing Improves Executive Function in Young Children.” Developmental Science 19 (3): 419–426. doi:10.1111/desc.12314

- Wigfield, Allan, and Jacquelynne S. Eccles. 2000. “Expectancy–Value Theory of Achievement Motivation.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1): 68–81. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

- Wood, Elizabeth Ann. 2014. “Free Choice and Free Play in Early Childhood Education: Troubling the Discourse.” International Journal of Early Years Education 22 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1080/09669760.2013.830562

- Yu, Yue, Patrick Shafto, Elizabeth Bonawitz, Scott C-H. Yang, Roberta M. Golinkoff, Kathleen H. Corriveau, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Fei Xu. 2018. “The Theoretical and Methodological Opportunities Afforded by Guided Play with Young Children.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1152. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01152

- Zosh, Jennifer M., Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Emily J. Hopkins, Hanne Jensen, Claire Liu, Dave Neale, S. Lynneth Solis, and David Whitebread. 2018. “Accessing the Inaccessible: Redefining Play as a Spectrum.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1124. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01124